Abstract

Objectives

We examined the association between diabetes mellitus (DM) and longitudinal MRI biomarkers for thigh muscle degeneration in patients with knee osteoarthritis (KOA) and their mediatory role in worsening KOA-related symptoms.

Methods

The Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) participants with radiographic KOA (Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 2) were included. Thighs and corresponding knees of KOA patients with versus without self-reported DM were matched for potential confounders using propensity score (PS) matching. We developed and used a validated deep learning method for longitudinal thigh segmentation. We assessed the association of DM with 4-year longitudinal muscle degeneration in biomarkers of muscle cross-sectional area (CSA) and contractile percentage (non-fat CSA/total CSA). We further investigated whether DM is associated with 9-year risk of KOA radiographic progression, knee replacement (KR), and symptoms worsening. Finally, we evaluated whether the DM–KOA worsening association is mediated through preceding muscle degeneration.

Results

After PS matching, 698 thighs/knees were included (185:513 with:without DM; average ± SD age:64 ± 8-years; female/male:1.4). Baseline DM was associated with a decreased contractile percent of total thigh muscles and quadriceps (mean difference, 95%CI −0.16%/year, −0.25 to −0.07, and −0.21%/year, −0.33 to −0.08). DM was also associated with an increased risk of worsening KOA-related symptoms (hazard ratio, 95%CI 1.70, 1.18–2.46) but not radiographic progression or KR. The decrease in quadriceps contractile percent partially mediated the increased risk of symptoms worsening in patients with DM.

Conclusions

Baseline DM is associated with thigh muscle degeneration and KOA-related symptoms worsening. As a potentially modifiable risk factor, DM-associated longitudinal thigh muscle degeneration may partially mediate the symptoms worsening in patients with DM and coexisting KOA.

Keywords: Diabetes mellitus, Intra-muscular adipose tissue, Skeletal muscle degeneration, Knee osteoarthritis, Symptom worsening

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is one of the most significant public health challenges due to high associated mortality and morbidity [1]. DM affects almost all body tissues, including skeletal muscles. Studies have shown that DM can affect skeletal muscle mass and strength and is associated with greater age-related muscle loss compared to those without DM [2]. Patients with DM have increased adipose deposition between (inter-muscular adipose tissue or inter-MAT) and within (intra-MAT) the abdominal skeletal muscles, irrespective of BMI, waist circumference [3, 4], or the amount of visceral adipose tissue [5]. Similar findings of muscle degeneration are observed in the lower limbs and may affect patients’ physical activity, especially when coexisting with other predisposing factors such as aging and osteoarthritis [6]. For example, DM-associated muscle degeneration can be clinically significant in the setting of coexisting knee osteoarthritis (KOA), where thigh muscle degeneration is an independent risk factor for KOA worsening [7].

Studies have shown KOA and DM frequently coexist [8]. While the most recent and extensive study of patients without KOA at baseline has shown that DM was not associated with the incidence of KOA at 5-year follow-up [9], several studies, including a meta-analysis, reported that DM is associated with progression of symptomatic KOA in patients who already have established KOA [10–12]. The exact mechanisms by which DM may contribute to KOA worsening remain poorly understood.

We hypothesized that DM-associated thigh muscle degeneration could potentially mediate the risk of worsening KOA-related outcomes. Numerous MRI-based studies have validated skeletal muscle size and composition as biomarkers for evaluating muscle degeneration in both DM [13, 14] and KOA [15, 16] settings. In this study, we used a previously validated deep learning segmentation model to automatically measure MRI biomarkers of thigh muscle degeneration and subsequently evaluated them for the following associations [17]. Using a longitudinal, multi-center, propensity score (PS)–matched sample of patients with KOA, we first aimed to assess the association of longitudinal thigh muscle degeneration with DM and further wished to investigate whether DM is associated with worsening in KOA structural and clinical outcomes. We finally aimed to explore the mediatory role of these muscle biomarkers in the potential association between DM and KOA outcomes.

Methods

Data source

We used data from the longitudinal multi-center OAI cohort study of 4796 participants with or at risk of KOA (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT00080171). The study has been approved by the ethics committee of OAI collaborating centers (approval code: 10–00532) [18]. All participants provided written informed consent. Supplementary Table S1 (online) describes the naming and version of OAI dataset files used in this study.

Population

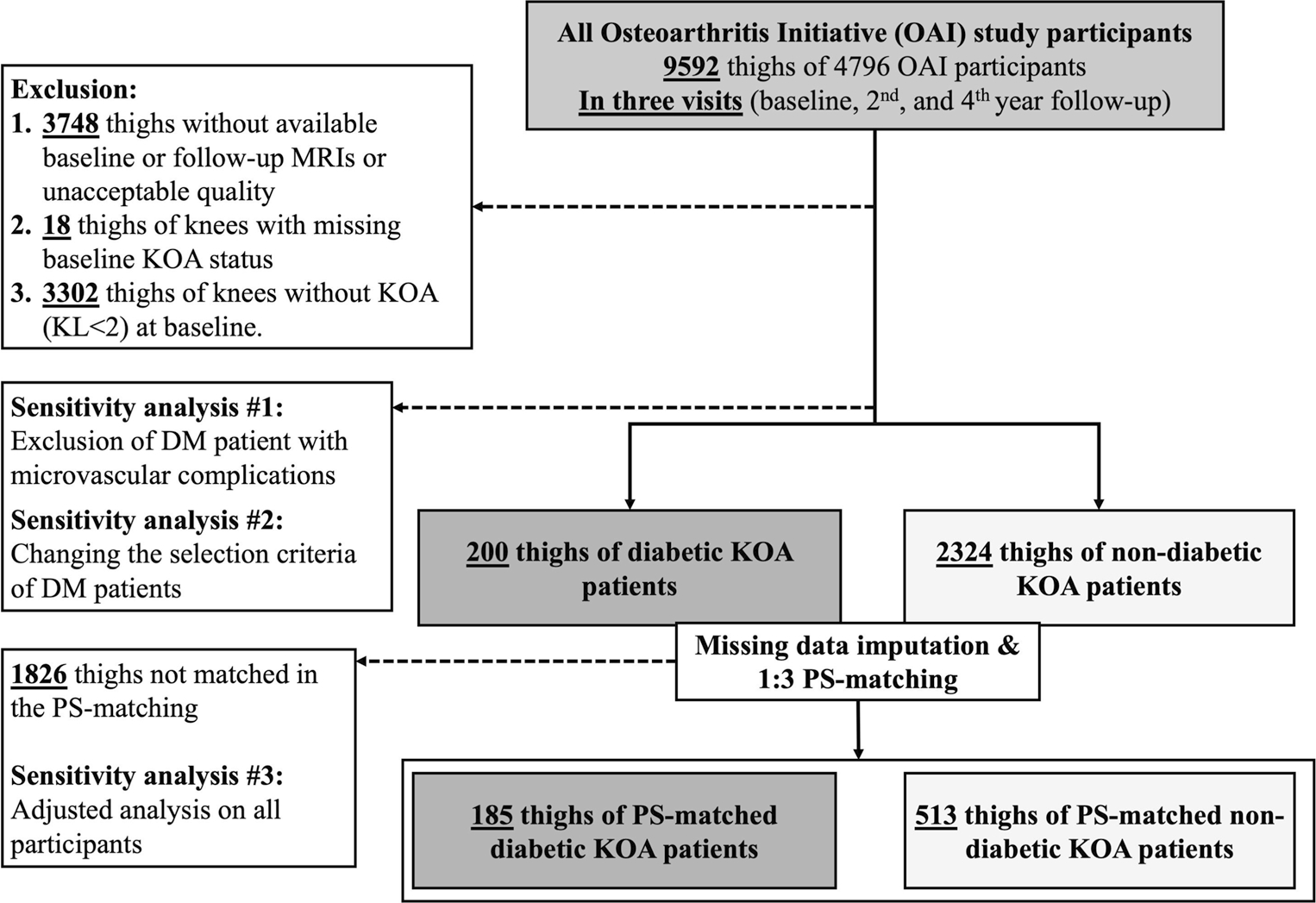

This study included participants with established KOA at the baseline visit. According to the OAI protocol, patients with bilateral KR surgery, inflammatory arthropathies, positive pregnancy tests, MRI contraindications, and comorbid conditions were excluded. To further tailor the study sample, after excluding thighs with missing MRI data, the available thigh MRIs were visually assessed by two readers and excluded in case of unacceptable quality (exclusion #1 in Fig. 1). During the baseline assessment of the OAI study, radiographic KOA was assessed using posteroanterior radiographs with a fixed-flexion (15°) protocol and was scored with semi-quantitative Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grades [19]. Participants with KL grade ≥ 2 were defined as having established KOA and were included. Knees with either missing KL grading or without KOA at baseline (KL grade < 2) were excluded from analysis (exclusions #2 and #3 in Fig. 1, respectively).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of eligible thighs included in the study. DM: diabetes mellitus, KL: Kellgren-Lawrence grade, KOA: knee osteoarthritis, PS: propensity score

Propensity score matching

To minimize the biased estimates caused by excluding the missing data [20], we evaluated the missing data pattern using Little’s test [21]. We then used the multiple imputation method to estimate missing values in the confounding variables (< 2.8% of data, Supplementary Table S2). Next, we matched the thighs/knees of KOA patients with DM to those without DM using a 1:2/3 PS-matching method on the imputed dataset, using logistic regression and the nearest-neighbor matching methods. The list of selected covariates included an extensive list of demographics, risk factors, comorbidities, and medications and are presented in Table 1 and Supplementary Appendix 1. The standardized mean difference (SMD) was used to evaluate matching precision between the groups, with a value of ≥ 0.1 indicating an imbalance (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants (OAI subjects with baseline knee osteoarthritis defined as radiographic Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 2) before and after propensity score matching according to the presence of DM

| Characteristic variables | All patients with KOA |

PS-matched patients with KOA |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of thighs\knees | DM (−) N: 2324 | DM (+) N: 200 | SMD | DM (−) N: 513 | DM (+) N: 185 | SMD |

|

| ||||||

| Subject characteristics | ||||||

| Age (year) (mean (SD)) | 62.18 (8.97) | 63.37 (8.28) | 0.137 | 64.01 (8.63) | 63.52 (8.16) | 0.059 |

| No. of women (N (%)) | 1346 (57.9) | 120 (60.0) | 0.042 | 300 (58.5) | 114 (61.6) | 0.064 |

| Race, non-White (N (%)) † | 512 (22.0) | 84 (42.0) | 0.438 | 193 (37.6) | 76 (41.1) | 0.071 |

| Comorbidities and risk factors | ||||||

| PASE score (mean (SD)) | 161.77 (79.89) | 130.27 (67.60) | 0.426 | 130.21 (73.23) | 134.36 (67.75) | 0.059 |

| BMI (kg/m2) (mean (SD)) | 29.23 (4.78) | 32.09 (4.79) | 0.598 | 31.76 (4.82) | 31.84 (4.73) | 0.017 |

| Abdominal (central) obesity (N (%))‡ | 1720 (74.0) | 182 (91.0) | 0.459 | 460 (89.7) | 167 (90.3) | 0.020 |

| Hypertension (N (%)) | 548 (23.6) | 60 (30.0) | 0.145 | 158 (30.8) | 56 (30.3) | 0.011 |

| CVA (N (%)) | 70 (3.0) | 17 (8.5) | 0.237 | 28 (5.5) | 13 (7.0) | 0.065 |

| Heart attack (N (%)) | 42 (1.8) | 8 (4.0) | 0.131 | 16 (3.1) | 4 (2.2) | 0.060 |

| Heart failure (N (%)) | 42 (1.8) | 12 (6.0) | 0.218 | 28 (5.5) | 8 (4.3) | 0.053 |

| Peripheral artery disease (N (%)) | 18 (0.8) | 2 (1.0) | 0.024 | 10 (1.9) | 2 (1.1) | 0.071 |

| Malignancy (N (%)) | 87 (3.7) | 22 (11.0) | 0.280 | 40 (7.8) | 18 (9.7) | 0.068 |

| Advanced liver disease (N (%)) | 1 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.029 | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0.062 |

| Kidney dysfunction (N (%)) | 16 (0.7) | 8 (4.0) | 0.220 | 12 (2.3) | 5 (2.7) | 0.023 |

| COPD (N (%)) | 40 (1.7) | 12 (6.0) | 0.223 | 15 (2.9) | 8 (4.3) | 0.075 |

| Peptic ulcer (N (%)) | 46 (2.0) | 18 (9.0) | 0.312 | 26 (5.1) | 14 (7.6) | 0.099 |

| KL grade (N (%)) | 0.089 | 0.051 | ||||

| Grade 2 | 1502 (64.6) | 122 (61.0) | 331 (64.5) | 115 (62.2) | ||

| Grade 3 | 672 (28.9) | 66 (33.0) | 149 (29.0) | 58 (31.4) | ||

| Grade 4 | 150 (6.5) | 12 (6.0) | 33 (6.4) | 12 (6.5) | ||

| Medial JSN grade (N (%)) | 0.195 | 0.061 | ||||

| Grade 0 | 862 (37.1) | 58 (29.0) | 159 (31.0) | 56 (30.3) | ||

| Grade 1 | 852 (36.7) | 76 (38.0) | 201 (39.2) | 69 (37.3) | ||

| Grade 2 | 518 (22.3) | 54 (27.0) | 120 (23.4) | 48 (25.9) | ||

| Grade 3 | 92 (4.0) | 12 (6.0) | 33 (6.4) | 12 (6.5) | ||

| Medications | ||||||

| Diuretic (N (%)) | 468 (20.1) | 66 (33.0) | 0.294 | 154 (30.0) | 58 (31.4) | 0.029 |

| β blocker (N (%)) | 350 (15.1) | 50 (25.0) | 0.250 | 113 (22.0) | 48 (25.9) | 0.092 |

| Calcium channel blocker (N (%)) | 238 (10.2) | 46 (23.0) | 0.348 | 103 (20.1) | 38 (20.5) | 0.011 |

| Lipid-lowering drug (N (%)) | 592 (25.5) | 118 (59.0) | 0.721 | 285 (55.6) | 103 (55.7) | 0.002 |

| NSAID (N (%)) | 456 (19.6) | 30 (15.0) | 0.122 | 86 (16.8) | 30 (16.2) | 0.015 |

| Aspirin (N (%)) | 58 (2.5) | 18 (9.0) | 0.282 | 30 (5.8) | 12 (6.5) | 0.027 |

| SSRI(N (%)) | 174 (7.5) | 18 (9.0) | 0.055 | 47 (9.2) | 16 (8.6) | 0.018 |

| Tricyclic antidepressant (N (%)) | 34 (1.5) | 6 (3.0) | 0.104 | 7 (1.4) | 5 (2.7) | 0.095 |

| Sedative (N (%)) | 112 (4.8) | 12 (6.0) | 0.052 | 22 (4.3) | 12 (6.5) | 0.097 |

| Systemic corticosteroid (N (%)) | 188 (8.1) | 16 (8.0) | 0.003 | 32 (6.2) | 12 (6.5) | 0.010 |

| Thyroid hormones (N (%)) | 248 (10.7) | 28 (14.0) | 0.101 | 62 (12.1) | 24 (13.0) | 0.027 |

| Antineoplastic agents (N (%)) | 64 (2.8) | 6 (3.0) | 0.015 | 15 (2.9) | 6 (3.2) | 0.018 |

| Anticoagulants (N (%)) | 58 (2.5) | 6 (3.0) | 0.031 | 17 (3.3) | 6 (3.2) | 0.004 |

| Insulin* (N (%)) | 0 (0.0) | 26 (13.0) | 0.547 | 0 (0.0) | 21 (11.4) | 0.506 |

| Oral hypoglycemic* (N (%)) | 0 (0.0) | 142 (71.0) | 2.191 | 0 (0.0) | 131 (70.8) | 2.139 |

| KOA symptoms* | ||||||

| WOMAC pain score (mean (SD)) | 2.54 (3.35) | 3.74 (4.16) | 0.318 | 3.25 (3.86) | 3.49 (3.95) | 0.061 |

| WOMAC disability score (mean (SD)) | 8.60 (10.85) | 12.62 (13.18) | 0.334 | 10.96 (12.74) | 11.70 (12.30) | 0.059 |

| WOMAC stiffness score (mean (SD)) | 1.61 (1.64) | 2.14 (1.92) | 0.299 | 1.88 (1.81) | 2.02 (1.83) | 0.095 |

| WOMAC total score (mean (SD)) | 12.75 (15.11) | 18.51 (18.57) | 0.340 | 16.00 (17.68) | 17.20 (17.33) | 0.069 |

| Thigh muscle MRI biomarkers* | ||||||

| Quadriceps CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 5091.74 (1378.60) | 5229.28 (1292.57) | 0.103 | 5302.82 (1332.89) | 5199.58 (1248.95) | 0.080 |

| Quadriceps intra-MAT CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 190.12 (147.46) | 258.59 (178.21) | 0.419 | 233.91 (154.97) | 251.70 (179.28) | 0.106 |

| Quadriceps contractile muscle % (mean (SD)) | 96.11 (3.10) | 94.86 (3.54) | 0.374 | 95.40 (3.23) | 94.99 (3.54) | 0.122 |

| Flexor CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 3342.22 (867.66) | 3382.40 (780.03) | 0.049 | 3453.75 (864.56) | 3344.16 (749.55) | 0.135 |

| Flexor intra-MAT CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 182.55 (155.11) | 262.44 (225.85) | 0.412 | 220.85 (172.35) | 254.58 (222.42) | 0.170 |

| Flexor contractile % (mean (SD)) | 94.46 (4.39) | 92.28 (5.70) | 0.430 | 93.54 (4.61) | 92.42 (5.66) | 0.216 |

| Adductor CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 1208.43 (621.89) | 1318.76 (645.52) | 0.174 | 1318.00 (641.73) | 1304.16 (641.52) | 0.022 |

| Adductor intra-MAT CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 74.29 (69.80) | 93.83 (62.30) | 0.295 | 92.89 (71.32) | 90.15 (60.79) | 0.041 |

| Adductor contractile % (mean (SD)) | 93.25 (4.75) | 92.08 (4.75) | 0.247 | 92.24 (5.00) | 92.28 (4.67) | 0.009 |

| Sartorius CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 385.94 (141.67) | 431.69 (146.53) | 0.317 | 424.69 (152.33) | 424.11 (145.59) | 0.004 |

| Sartorius intra-MAT CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 34.41 (29.78) | 49.84 (34.98) | 0.475 | 45.92 (36.48) | 47.71 (34.31) | 0.050 |

| Sartorius contractile % (mean (SD)) | 91.13 (6.31) | 88.58 (6.27) | 0.405 | 89.21 (6.68) | 88.86 (6.23) | 0.054 |

| Total thigh muscle CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 10028.33 (2650.01) | 10362.13 (2476.21) | 0.130 | 10499.26 (2586.65) | 10272.01 (2383.85) | 0.091 |

| Intra-MAT CSA (mm2) (mean (SD)) | 481.38 (346.97) | 664.69 (420.80) | 0.475 | 593.57 (365.26) | 644.13 (417.29) | 0.129 |

| Total thigh muscle contractile muscle % | 95.09 (3.27) | 93.45 (3.94) | 0.453 | 94.22 (3.38) | 93.61 (3.93) | 0.167 |

Data are presented in numbers of thighs\knees. A significant difference for SMD was defined as ≥ 0.1 and is shown in bold. ACEI angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor, ARB angiotensin receptor blocker, BMI body mass index, CSA cross-sectional area, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, CVA cerebrovascular accident, DM diabetes mellitus, intra-MAT intra-muscular adipose tissue, KL Kellgren-Lawrence grade, N Newton, NSAIDs nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, PASE Physical Activity for Elderly Scale, PS propensity score, SMD standardized mean difference, SD standard deviation, SSRI selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor, WOMAC Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index

These variables were not included in the PS matching

Race of participants was categorized as White and non-White considering the small number of participants in each non-White race group

Abdominal obesity was defined as a waist circumference of ≥ 94 cm in men and ≥ 80 cm in women on physical examination according to international DM foundation criteria

Thigh MRI segmentation and quantitative biomarkers of thigh muscle degeneration

Thigh MRI was conducted at baseline, 2nd, and 4th year according to specific instructions. According to prior studies on the OAI dataset, 33% distal length of the femur is an anatomical landmark covered in images of all participants and is representative of total thigh muscle volume and adiposity [22, 23]. We, therefore, extracted the corresponding axial slice according to the method proposed by Cotofana et al [23]. The follow-up MRIs were registered to selected baseline axial slice and were used to develop and validate a fully automated supervised deep learning algorithm for segmentation and interpretation of all thigh MR images available in the OAI [17]. The details of the thigh MRI protocol, development and validation of an automated deep learning algorithm for image segmentation, and thresholding method for adipose tissue quantification are previously described [17]. The intra-MAT [24] was calculated as the area (mm2) of fat-containing pixels inside muscle segments. The CSA for each thigh muscle group (quadriceps, flexors, adductors, and sartorius) was directly calculated from segmentations. Finally, the contractile percentage for each muscle was measured by dividing the CSA of the fat-free area of the muscle by all muscle CSA. The outcome variables can be found in Table 1 and Supplementary Figure E1.

KOA radiographic progression, knee replacement, and KOA-related symptoms worsening

Radiographic progression of medial joint space narrowing (JSN) was defined as a full-grade increase in Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI) grade JSN score of ≥ 1 during the annual follow-up assessments of knees with baseline JSN grade of 0–2 [25]. Incidence of KR surgery during the 9-year follow-up was also regarded as an outcome of interest. KOA-related symptoms worsening was assessed using disability and pain domains of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) [26]. WOMAC pain and disability scores were standardized to a range of 0–100 and then were summed, giving a standardized combined WOMAC score. Non-acceptable symptomatic state (NASS) incidence was defined as a combined standardized WOMAC pain or disability score of 80 or higher (each on a scale of 100 for a maximum potential combined score of 200) for two consecutive years in knees with a baseline score of < 80 [26–29].

Statistical analysis

Multilevel linear mixed-effect regression models were used to compare baseline to 4th-year changes in thigh muscle MRI biomarkers between PS-matched KOA patients with and without DM. We considered random intercept and slope for each cluster of PS-matched thighs/knees with and without DM and a random intercept for within-subject similarities (due to the inclusion of thighs/knees of both sides in participants). Interaction between time and the presence of DM (versus its absence as the reference) was the independent predictor, while MRI-derived thigh muscle biomarkers were the dependent outcomes.

Also, the predictive role of DM, as the independent variable, on KOA radiographic progression (medial JSN), KR surgery, and KOA-related symptoms worsening (NASS), as dependent factors, was measured using the Cox proportional hazard regression model over 9 years of follow-up and was reported as hazard ratio (HR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

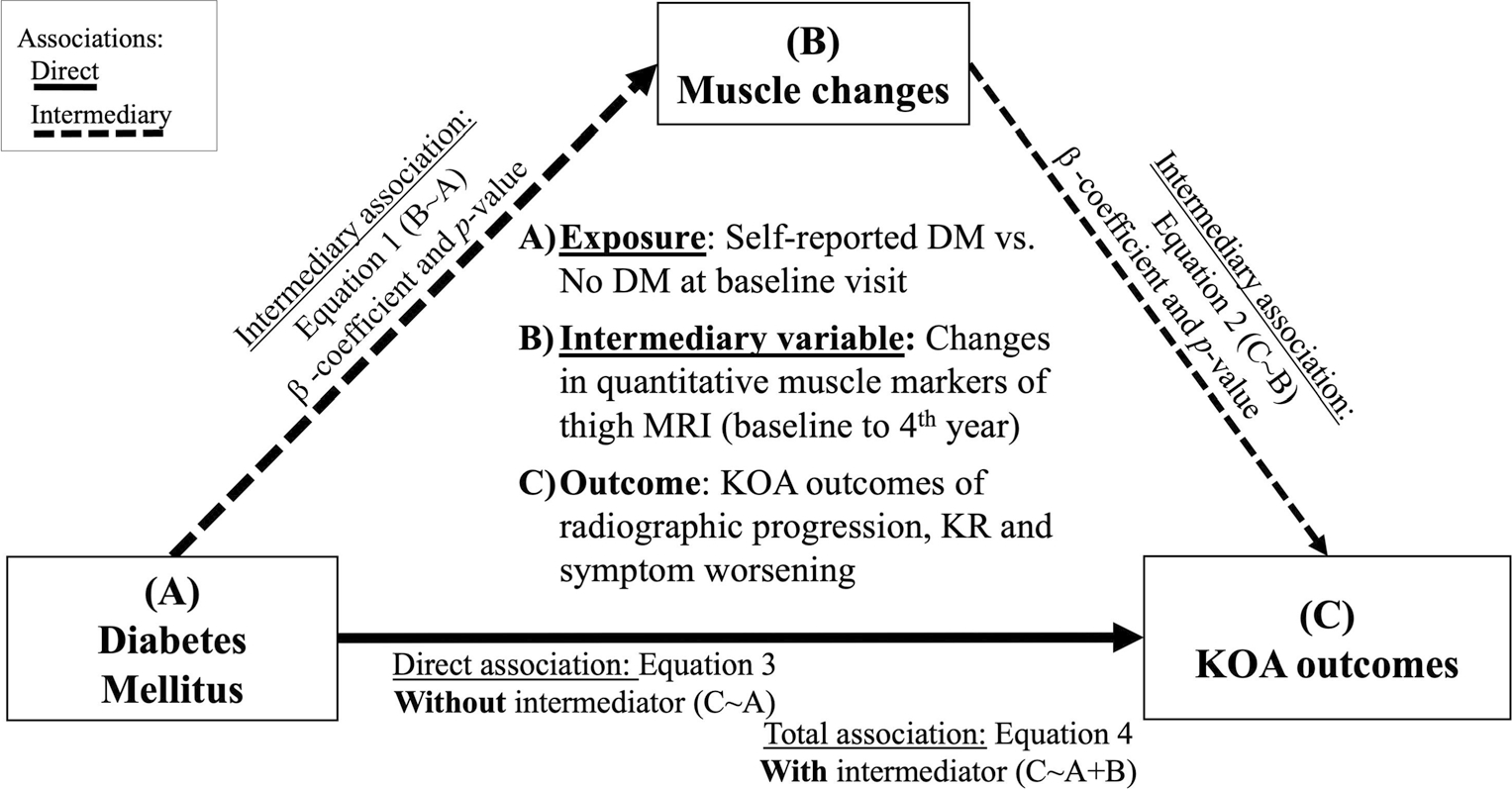

Causal mediation analysis with 1000 Monte Carlo draws for non-parametric bootstrap approximation was used to evaluate whether the association of DM with KOA worsening is mediated through muscle degeneration (Fig. 2). Relative changes () in the muscle biomarkers during baseline to 4th year were regarded as mediatory variables. Assumptions of both linear mixed-effect regression (homogeneity of variance, exogeneity, linearity, normal distribution of data and residuals) and Cox (proportional hazards, linearity, influential observations) models were assessed. While other assumptions were confirmed, the non-normality of relative changes in muscle biomarkers was addressed using scaling and normalizing data.

Fig. 2.

Causal mediation analysis. We evaluated the role of changes in MRI biomarkers of thigh muscle degeneration (baseline to 4th year) as the mediatory variables of the association between DM and KOA worsening. KOA-related symptoms worsening was assessed using NASS incidence. DM: diabetes mellitus, KOA: knee osteoarthritis, NASS: non-acceptable symptomatic state

All statistical analyses were performed using the R software version 4.0.3 (haven, MatchIt, mice, survival, lme4, lmerTest, mediation, and tableone packages). The false discovery rate (FDR) method was used to correct p values for family-wise error associated with multiple comparisons. A two-tailed FDR-corrected p value < 0.05 was regarded as the sign of a statistically significant difference.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted three sensitivity analyses to evaluate the robustness of our results. First, since DM microvascular complications can directly affect thigh muscle degeneration, we excluded patients with DM who reported diabetic nephropathy or retinopathy at baseline to 4th-year follow-up to assess the changes in the absence of these complications. Unfortunately, diabetic neuropathy data is not directly available in the OAI dataset; however, neuropathy is strongly associated with nephropathy and ophthalmopathy in DM patients [30] (sensitivity analysis #1 in Fig. 1). In the second analysis, due to inaccuracies associated with self-reported DM assessment, we assessed the sensitivity of results to different selection criteria of patients with DM in which we only included patients who received anti-hyperglycemic treatments or had reported DM complications (sensitivity analysis #2 in Fig. 1). Finally, we evaluated the sensitivity of our results to PS matching by conducting the analyses on entire eligible participants while adjusting all covariates of the PS matching (sensitivity analysis #3 in Fig. 1).

Results

Baseline characteristics

Of 9592 thighs (bilateral thighs/knees of 4796 participants) assessed for eligibility criteria, 3748 did not have quality MRIs at baseline, and at least one of the follow-up visits (2nd or 4th year), 18 were thighs of knees with missing data of baseline OA status, and 3302 thighs were for knees without KOA (KL grade < 2) and were therefore excluded (exclusions #1–3 in Fig. 1). After classifying the remaining 2524 thighs/knees for DM at baseline (200 thighs of KOA patients with DM versus 2324 without DM) and further PS matching, 185 knees and corresponding thighs of KOA patients with versus 513 without DM were included (Fig. 1). Matching results showed SMD < 0.1 for all covariates, indicating no statistical imbalance between variables included in the PS matching (Table 1).

There was no difference in baseline KOA radiographic grade (KL and JSN) and KOA-related symptoms (WOMAC scores) between PS-matched patients with and without DM at baseline (SMDs < 0.1). However, a comparison of baseline MRI thigh biomarkers showed significantly higher intra-MAT CSA (644.13 ± 417.29 versus 593.57 ± 365.26, SMD: 0.13) and lower total contractile muscle percentage (93.61 ± 3.93 versus 94.22 ± 3.38, SMD: 0.17) in participants with DM.

The association between DM and 4-year thigh muscle degeneration

As presented in Table 2, having DM was associated with longitudinal increases in total intra-MAT (mean difference/year, 95%CI 15.42 mm2/year, 6.41–24.44) and quadriceps intra-MAT (mean difference/year, 95%CI 9.71 mm2/year, 3.80–15.61) in patients with KOA. Furthermore, DM was associated with a longitudinal decrease in the total contractile thigh muscle percentage (mean difference/year, 95%CI −0.16 percent/year, −0.25 to −0.07) and quadriceps contractile percentage (mean difference/year, 95%CI −0.21 percent/year, −0.33 to −0.08) compared to those without DM, among patients with KOA. Having DM was also associated with a decrease in sartorius CSA (mean difference/year, 95%CI −5.35 mm2/year, −7.89 to −2.80). However, neither of the other muscles’ CSAs, intra-MAT or inter-MAT, were associated with the presence of DM (FDR-corrected p values > 0.05).

Table 2.

Differences in MRI biomarkers of thigh muscles in PS-matched KOA patients with versus without DM over 4-year follow-up

| Average difference/year (95% CI), p |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| CSA (mm2) | Intra-MAT CSA (mm2) | Contractile % | |

|

| |||

| Total thigh muscles | −24.10 (−59.20–10.99), p: 0.179 | 15.42 (6.41–24.44), p < 0.001 * | −0.16 (−0.25 to −0.07), p < 0.001 * |

| Quadriceps | −13.99 (−34.36–6.37),p: 0.178 | 9.71 (3.80–15.61), p: 0.001 * | −0.21 (−0.33 to −0.08), p: 0.001 * |

| Flexors | −4.17 (−16.42–8.08), p: 0.505 | 5.07 (0.13–10.01), p: 0.044 | −0.15 (−0.29 to −0.02), p: 0.028 |

| Adductors | −0.55 (−13.05–11.94), p: 0.931 | 1.70 (−0.37–3.76),p: 0.107 | −0.13 (−0.30–0.04), p: 0.126 |

| Sartorius | −5.35 (−7.89 to −2.80), p < 0.001 * | −0.53 (−1.55–0.48),p: 0.302 | 0.05 (−0.16–0.26), p: 0.641 |

| Inter-muscular tissue | −9.70 (−18.47 to −0.93), p: 0.030 | – | – |

Longitudinal mixed-effect regressions were used. CI confidence interval, CSA cross-sectional area, DM diabetes mellitus, intra-MAT intra-muscular adipose tissue

Significant FDR-corrected p values

The association between DM and 9-year longitudinal risk of worsening in KOA outcomes

Survival analysis indicated that DM is associated with an increased risk of symptoms worsening (NASS HR, 95%CI 1.70, 1.18–2.46) (Table 3). Nonetheless, the presence of DM was neither associated with the risk of KOA JSN progression nor KR surgery (HRs, 95%CI 0.87, 0.55–1.37, and 1.01, 0.56–1.8, respectively) among patients with KOA.

Table 3.

Association between DM and longitudinal risk of KOA worsening, PS-matched KOA patients with versus without DM

| Outcomes | Hazard ratio (95%CI), p |

|---|---|

|

| |

| KOA JSN progression | 0.87 (0.55–1.37), p: 0.536 |

| Knee replacement surgery | 1.01 (0.56–1.8), p: 0.983 |

| NASS incidence | 1.70 (1.18–2.46), p: 0.005 * |

Cox proportional hazards analysis was used. Independent variable: DM versus no DM (reference); DM was associated with an increased risk of NASS incidence over the follow-up of up to 9 years. CI confidence interval, DM diabetes mellitus, JSN joint space narrowing, KOA knee osteoarthritis, NASS non-acceptable symptomatic state, PS propensity score

Significant FDR-corrected p values

Mediatory role of thigh muscle loss in the association between DM and KOA-related symptoms worsening

We assessed the mediatory role of thigh muscle CSA in the association of DM and NASS incidence (as the KOA outcome associated with baseline DM in our results) (Table 4). We only assessed muscle biomarkers that showed an association with DM. Our results showed that longitudinal changes of quadriceps muscle contractile percentage significantly but partially mediated DM risk for KOA-related symptoms worsening (NASS, β estimate, 95% CI 1.82, 0.22–4.70). The other assessed thigh MRI biomarkers had no significant mediatory role in the association between DM and longitudinal risk of KOA-related symptom worsening (p values > 0.05).

Table 4.

Mediatory role of thigh muscle MRI biomarkers in the association between DM and KOA non-acceptable symptoms state incidence

| Estimate (95% CI), p |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediatory variables* | Total association of DM with NASS incidence (through Equation 1 in Figure 2) | Direct association of DM with NASS incidence† (through Equation 2 in Figure 2) | Mediatory role of thigh muscle biomarkers in the association of DM and NASS incidencef (through Equations 3a and 3b in Figure 2) |

|

| |||

| 4-year changes in: | |||

| Quadriceps intra-MAT CSA (mm2) | 17.630 (7.293–30.817), p < 0.001 | 17.650 (7.444–30.606), p < 0.001 | −0.020 (−0.704–0.579), p: 1.000 |

| Quadriceps contractile %# | 17.020 (6.844–31.193), p < 0.001 | 15.198 (5.188–28.540), p < 0.001 | 1.823 (0.216–4.679), p: 0.020 |

| Sartorius CSA (mm2) | 17.334 (5.025–28.564), p < 0.001 | 17.848 (5.317–29.130), p < 0.001 | −0.513 (−1.814–0.474), p: 0.420 |

| Intra-MAT CSA (mm2) | 16.431 (5.450–26.642), p <0.001 | 16.884 (5.752–26.732), p < 0.001 | −0.453 (−1.884–0.362), p: 0.400 |

| Total thigh muscle contractile % | 17.766 (6.828–28.493), p < 0.001 | 17.434 (6.448–28.548), p < 0.001 | 0.332 (−1.610–2.155), p: 0.920 |

CI confidence interval, CSA cross-sectional area, DM diabetes mellitus, intra-MAT intra-muscular adipose tissue, NASS non-acceptable symptomatic state

Thigh muscle biomarkers that were found associated with DM were selected for causal mediation analysis

Quadriceps contractile percent was the only assessed thigh muscle marker that mediated the association of DM with longitudinal risk of NASS incidence

Sincemixedmodels could not be used in mediation analysis of R mediate package, here longitudinal changes in themuscle biomarkers were assessed as relative change index between baseline and 4th -year visits, i.e., (baseline–4th year)/baseline

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses showed that our results were not sensitive to either exclusion of patients with microvascular complications of DM (Supplementary Table S3), changing selection criteria of patients with DM (Supplementary Table S4), or the inclusion of all eligible participants instead of PS-matched participants while adjusting for potential covariates (Supplementary Table S5).

Discussion

This study found that the presence of DM in patients with coexisting KOA is associated with worsening thigh muscle degeneration, evident as a lower muscle contractile percentage and higher intra-muscular adiposity. Moreover, while DM was not associated with KOA structural progression, we showed that KOA patients with DM had a higher risk of worsening OA-related symptoms. For the first time, we demonstrated that the association of DM with KOA-related symptoms worsening is partially mediated by the preceding changes in the quadriceps muscle contractile percentage, which could be considered a potentially modifiable risk factor and, therefore, a potential target for future interventions in patients with DM and coexisting KOA [7, 31, 32].

The loss of muscle mass and strength has been reported in patients with DM and may be partly related to the presence of neuropathy. However, previous studies have demonstrated controversial results [33, 34]. Prior works have investigated the effects of hyperglycemia and insulin resistance on lipid and protein metabolism, mitochondrial function, and autophagy pathways in skeletal muscle [35, 36]. A combination of advanced glycosylation end products’ (AGEs) accumulation, oxidative stress, and resistance to insulin in the skeletal muscles of patients with DM could induce changes in the muscle structure and metabolism and lead to muscle degeneration [35, 36]. Independent of DM status, there is overwhelming evidence that quadriceps degeneration is a risk factor for worsening symptoms and joint damage in patients with KOA [37]. This study emphasizes the role of the “DM-thigh muscle degeneration-KOA-related symptoms worsening” pathophysiological pathway with confirmation and linking the previously described associations of DM with quadriceps degeneration and KOA symptoms worsening. Since increased intra-MAT and reduced contractile percent of the thigh muscles can be targeted through effective clinical interventions [7, 31, 32], our results provide evidence for a potentially modifiable risk factor for the clinical management of the DM-associated muscle degeneration and consecutive KOA symptoms worsening. However, our results suggest a partial, rather than a complete, mediation, and further research is required to investigate the other “unaccounted-for” mechanisms participating dependent or independent of this pathway, including direct effects of the DM on the knee joint cartilage and/or subchondral bone [38].

Results of previous studies on the association of DM and KOA incidence and progression have been inconclusive overall [11, 12]. The recent and largest observational study showed no association between DM and KOA incidence [9]. While our results were focused on the progression of KOA (rather than its incidence), we similarly observed no significant association between DM and radiographic progression and KR in patients with KOA. However, confirming our findings on KOA-related symptoms worsening, a limited but growing body of evidence suggests DM as an independent predictor for symptomatic progression in patients with pre-existing KOA [10–12]. For example, in a cross-sectional study of OAI data by Alenazi et al [10], patients with concurrent DM and KOA had more than two times higher likelihood of having knee pain than those with KOA alone. Similar results were obtained from a recent study by Eitner et al [39]. They showed that patients with DM had worse symptoms in a variety of KOA pain scoring tools, including Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) and pain numeric rating scale (NRS), independent of BMI, KOA severity, age, and gender [39].

The OAI study is uniquely designed to address fundamental questions about various perspectives of KOA progression (e.g., risk factors, treatments, outcomes) and has the advantages of a large sample size, long-term follow-up, detailed list of potential confounders, different demographic, clinical, and ancillary data related to KOA, and optimized thigh MRI protocol for skeletal muscle and adipose tissue segmentation [18]. This OAI-derived study has several strengths like careful selection criteria, PS-matched design to minimize potential confounding bias, and sensitivity analyses to assess the robustness of the results. However, this study is also subjected to several limitations. First, our assessments of thigh muscles only included a particular anatomical location (33% distal level of the femoral bone: distal–proximal) and not the other thigh levels or a volumetric analysis of the whole thigh, given that OAI thigh MRI does not cover total thigh length [18]. Second, the automated deep learning segmentation method showed less accuracy in the inter-muscular tissue segmentation compared with other thigh segments. As presented in our previous publication [17], segmentation errors did not significantly affect inter-MAT or intra-MAT assessments between automated and manual segmentation methods. However, the effect of these errors on clinical inference from these biomarkers needs to be further determined. Third, we used self-reported history and the use of glucose-lowering therapy for the definition of DM; given that we did not have availability of laboratory testing, it is possible that persons with undiagnosed DM were misclassified in the control group. However, this method has been implemented in previous OAI studies [9, 10] and has shown high reliability in identifying patients with DM in population-based studies [40]. Fourth, diabetic neuropathy, as a microvascular complication of DM, can contribute to thigh muscle degeneration and pain in the lower limb. However, the OAI study did not assess for the presence of diabetic neuropathy. Given the inherent limitations, we attempted relevant sensitivity analyses with the available data (sensitivity analysis #1: excluding other microvascular complications; and sensitivity analysis #2: only including patients who received anti-hyperglycemic treatments), which confirmed our primary findings. Fifth, DM-specific characteristics such as glycemic control (i.e., HbA1c, fasting blood glucose levels), type of DM, and disease duration were not assessed in the OAI cohort and, therefore, were not included. These disease characteristics may affect and/or mediate the association between DM with muscle degeneration or KOA worsening. Finally, our analysis was focused on patients with existing KOA, and associations of DM with thigh muscle degeneration and KOA incidence in patients without coexisting KOA are remained to be explored in future studies.

In conclusion, our results show that DM is associated with muscle degeneration and symptoms worsening in KOA patients. The DM-associated muscle degeneration, evident as reduced quadriceps contractile percentage, partially mediates KOA symptoms worsening. Association of DM with symptoms worsening raises the need for further attention on DM as a potential independent risk factor for potentially modifiable thigh muscle degeneration leading to KOA-related symptoms worsening. Definition of the involved mechanisms paves the way to discover the optimum strategy for minimizing the aggravating effects of DM on KOA-related symptoms worsening, which can be critical given the current absence of any disease-modifying OA drug (DMOAD). Moreover, future trials are warranted to elucidate the application of improved DM glycemic control and quadriceps-modifying interventions such as periodized training to attenuate KOA-related symptoms worsening.

Supplementary Material

Key Points.

Diabetes mellitus (DM) is associated with worsening knee osteoarthritis (KOA)-related symptoms.

As a potentially modifiable factor, DM-associated thigh muscle (quadriceps) degeneration partially mediates the worsening of KOA-related symptoms.

Acknowledgements

The osteoarthritis initiative, a collaborative project between public and private sectors, includes five contracts N01-AR-2-2258, N01-AR-2-2259, N01-AR-2-2260, N01-AR-2-2261, and N01-AR-2-2262. This project is conducted by the osteoarthritis initiative project investigators and is financially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Private funding partners are Merck Research Laboratories, Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation, GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer, Inc. In preparing this manuscript, osteoarthritis initiative project publicly available datasets were used. The results of this work do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the osteoarthritis initiative project investigators, the NIH, or the private funding partners.

Funding

This research was supported by the NIH National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS) under Award Number R01AR079620-01.

Abbreviations

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidence interval

- CSA

Cross-sectional area

- DM

Diabetes mellitus

- DMOAD

Disease-modifying osteoarthritis drug

- HR

Hazard ratio

- Inter-MAT

Inter-muscular adipose tissue

- Intra-MAT

Intra-muscular adipose tissue

- JSN

Joint space narrowing

- KL

Kellgren-Lawrence

- KOA

Knee osteoarthritis

- KR

Knee replacement

- NASS

Non-acceptable symptomatic state

- OAI

Osteoarthritis Initiative

- PASE

Physical activity for elderly scale

- PS

Propensity score

- SMD

Standardized mean difference

- WOMAC

Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index

Footnotes

Conflict of interest FWR is chief marketing officer and shareholder of Boston Imaging Core Lab (BICL), LLC, and consultant to Calibr – California Institute of Biomedical Research and Grünenthal GmbH. AG is a shareholder of BICL and consultant to Pfizer, TissueGene, MerckSerono, Novartis, Regeneron, and AstraZeneca. FB reports personal fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer, Bone Therapeutics, CellProthera, Expanscience, Galapagos, Gilead, Grunenthal, GSK, Eli Lilly, Merck Sereno, MSD, Nordic, Nordic Bioscience, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, Sandoz, Sanofi, Servier, UCB, Peptinov, 4P Pharma, grants from TRB Chemedica, non-financial support from 4Moving Biotech, outside the submitted work. The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies, whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Guarantor Dr. Shadpour Demehri takes full responsibility for the work as a whole, including the study design, access to data, and the decision to submit and publish the manuscript.

Statistics and biometry No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed consent Subjects have given informed consent before participating in the Osteoarthritis Initiative (OAI) project.

Ethical approval The medical ethics review boards of the University of California, San Francisco (Approval Number: 10–00532) and the four clinical centers of osteoarthritis initiative project recognized the project as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA)–compliant.

Methodology

• Retrospective

• Observational

• Multi-center study

Supplementary Information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-022-09035-4.

References

- 1.Liu J, Ren Z-H, Qiang H et al. (2020) Trends in the incidence of diabetes mellitus: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017 and implications for diabetes mellitus prevention. BMC Public Health 20:1415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kalyani RR, Metter EJ, Egan J, Golden SH, Ferrucci L (2015) Hyperglycemia predicts persistently lower muscle strength with aging. Diabetes Care 38:82–90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiefer LS, Fabian J, Rospleszcz S et al. (2021) Distribution patterns of intramyocellular and extramyocellular fat by magnetic resonance imaging in subjects with diabetes, prediabetes and normoglycaemic controls. Diabetes Obes Metab 23:1868–1878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kiefer LS, Fabian J, Rospleszcz S et al. (2018) Assessment of the degree of abdominal myosteatosis by magnetic resonance imaging in subjects with diabetes, prediabetes and healthy controls from the general population. Eur J Radiol 105:261–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Granados A, Gebremariam A, Gidding SS et al. (2019) Association of abdominal muscle composition with prediabetes and diabetes: the CARDIA study. Diabetes Obes Metab 21:267–275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Park SW, Goodpaster BH, Strotmeyer ES et al. (2007) Accelerated loss of skeletal muscle strength in older adults with type 2 diabetes: the health, aging, and body composition study. Diabetes Care 30:1507–1512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teichtahl AJ, Wluka AE, Wang Y et al. (2015) Vastus medialis fat infiltration - a modifiable determinant of knee cartilage loss. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23:2150–2157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Louati K, Vidal C, Berenbaum F, Sellam J (2015) Association between diabetes mellitus and osteoarthritis: systematic literature review and meta-analysis. RMD Open 1:e000077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuusalo L, Felson DT, Wang N et al. (2021) Metabolic osteoarthritis - relation of diabetes and cardiovascular disease with knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 29:230–234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Alenazi AM, Alshehri MM, Alothman S et al. (2020) The association of diabetes with knee pain severity and distribution in people with knee osteoarthritis using data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Sci Rep 10:3985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schett G, Kleyer A, Perricone C et al. (2013) Diabetes is an independent predictor for severe osteoarthritis: results from a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care 36:403–409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eymard F, Parsons C, Edwards MH et al. (2015) Diabetes is a risk factor for knee osteoarthritis progression. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 23:851–859 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therkelsen KE, Pedley A, Speliotes EK et al. (2013) Intramuscular fat and associations with metabolic risk factors in the Framingham Heart Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 33:863–870 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modesto AE, Ko J, Stuart CE, Bharmal SH, Cho J, Petrov MS (2020) Reduced skeletal muscle volume and increased skeletal muscle fat deposition characterize diabetes in individuals after pancreatitis: a magnetic resonance imaging study. Diseases 8:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beattie KA, MacIntyre NJ, Ramadan K, Inglis D, Maly MR (2012) Longitudinal changes in intermuscular fat volume and quadriceps muscle volume in the thighs of women with knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Care Res 64:22–29 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kumar D, Link TM, Jafarzadeh SR, LaValley MP, Majumdar S, Souza RB (2021) Association of quadriceps adiposity with an increase in knee cartilage, meniscus, or bone marrow lesions over three years. Arthritis Care Res 73:1134–1139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mohajer B, Dolatshahi M, Moradi K et al. (2022) Role of thigh muscle changes in knee osteoarthritis outcomes: osteoarthritis initiative data. Radiology:212771. 10.1148/radiol.212771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevitt M, Felson D, Lester G (2006) The osteoarthritis initiative protocol for the cohort study. Available via 10.1016/j.joca.2016.09.013/attachment/17129285-04bf-4f1c-a2f4-6c3f498da638/mmc2.pdf [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morville T, Dohlmann TL, Kuhlman AB et al. (2019) Aerobic exercise performance and muscle strength in statin users-the LIFESTAT study. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51:1429–1437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Donders AR, van der Heijden GJ, Stijnen T, Moons KG (2006) Review: a gentle introduction to imputation of missing values. J Clin Epidemiol 59:1087–1091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li C (2013) Little’s test of missing completely at random. Stata J 13:795–809 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kemnitz J, Wirth W, Eckstein F, Culvenor AG (2018) The role of thigh muscle and adipose tissue in knee osteoarthritis progression in women: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 26:1190–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cotofana S, Hudelmaier M, Wirth W et al. (2010) Correlation between single-slice muscle anatomical cross-sectional area and muscle volume in thigh extensors, flexors and adductors of perimenopausal women. Eur J Appl Physiol 110:91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahmad E, McPhee JS, Degens H, Yap MH (2018) Automatic segmentation of mri human thigh muscles: Combination of reliable and fast framework methods for quadriceps, femur and marrow segmentation. In: Proceedings of the 2018 8th International Conference on Biomedical Engineering and Technology, pp 31–38 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dougados M, Hawker G, Lohmander S et al. (2009) OARSI/OMERACT criteria of being considered a candidate for total joint replacement in knee/hip osteoarthritis as an endpoint in clinical trials evaluating potential disease modifying osteoarthritic drugs. J Rheumatol 36:2097–2099 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Angst F, Ewert T, Lehmann S, Aeschlimann A, Stucki G (2005) The factor subdimensions of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) help to specify hip and knee osteoarthritis. a prospective evaluation and validation study. J Rheumatol 32:1324–1330 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Manno RL, Bingham CO 3rd, Paternotte S et al. (2012) OARSI-OMERACT initiative: defining thresholds for symptomatic severity and structural changes in disease modifying osteoarthritis drug (DMOAD) clinical trials. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 20:93–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Haj-Mirzaian A, Mohajer B, Guermazi A et al. (2019) Statin use and knee osteoarthritis outcome measures according to the presence of Heberden nodes: results from the osteoarthritis initiative. Radiology 293:396–404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cotofana S, Wirth W, Guenther O, Rossi CP, Eckstein F (2014) Contralateral knee effect on functional assessments–data from the osteoarthritis initiative (OAI). Osteoarthritis Cartilage 22:S401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Girach A, Vignati L (2006) Diabetic microvascular complications—can the presence of one predict the development of another? J Diabetes Complications 20:228–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.de Almeida AC, Aily JB, Pedroso MG et al. (2020) A periodized training attenuates thigh intermuscular fat and improves muscle quality in patients with knee osteoarthritis: results from a randomized controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol 39:1265–1275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raynauld J-P, Pelletier J-P, Roubille C et al. (2015) Magnetic resonance imaging–assessed vastus medialis muscle fat content and risk for knee osteoarthritis progression: relevance from a clinical trial. Arthritis Care Res 67:1406–1415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watari R, Sartor CD, Picon AP et al. (2014) Effect of diabetic neuropathy severity classified by a fuzzy model in muscle dynamics during gait. J Neuroeng Rehabil 11:11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ferreira JP, Sartor CD, Leal ÂMO et al. (2017) The effect of peripheral neuropathy on lower limb muscle strength in diabetic individuals. Clin Biomech 43:67–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kaushik S, Rodriguez-Navarro JA, Arias E et al. (2011) Autophagy in hypothalamic AgRP neurons regulates food intake and energy balance. Cell Metab 14:173–183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DeFronzo RA, Tripathy D (2009) Skeletal muscle insulin resistance is the primary defect in type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care 32:S157–S163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Segal NA, Glass NA, Torner J et al. (2010) Quadriceps weakness predicts risk for knee joint space narrowing in women in the MOST cohort. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 18:769–775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Berenbaum F (2011) Diabetes-induced osteoarthritis: from a new paradigm to a new phenotype. Ann Rheum Dis 70:1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eitner A, Culvenor AG, Wirth W, Schaible HG, Eckstein F (2021) Impact of diabetes mellitus on knee osteoarthritis pain and physical and mental status: data from the osteoarthritis initiative. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 73:540–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okura Y, Urban LH, Mahoney DW, Jacobsen SJ, Rodeheffer RJ (2004) Agreement between self-report questionnaires and medical record data was substantial for diabetes, hypertension, myocardial infarction and stroke but not for heart failure. J Clin Epidemiol 57:1096–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.