Abstract

An increasing body of work documents the roles of religion and spirituality in Black American marriages. We built on this research to examine religious coping as a potential cultural resource for Black marriages using a dyadic analytic approach with longitudinal data. Specifically, we investigated the effects of positive (i.e., sense of spiritual connectedness) and negative (i.e., spiritual tension or struggle) religious coping on trajectories of marital love reported by wives and husbands in 161 Black, married, mixed-gender couples, and we tested the potential moderating role of spouse gender. At baseline, spouses reported on their religious coping, and they rated their marital love at baseline and during two additional home interviews conducted annually. Data were analyzed using growth curve modeling within an Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling framework. Husbands who reported more positive religious coping at baseline exhibited relatively high and stable marital love over time, whereas those who reported less positive religious coping reported less love at baseline and exhibited declines in love over time. Wives who reported less negative religious coping at baseline were higher in marital love initially but showed declines over time, whereas those who reported more negative religious coping at baseline were lower in marital love initially but showed increases in love over time. Results highlight the importance of further research on the role of religion and religious coping in Black couples’ marital experiences and suggest differential roles of positive and negative religious coping for men’s and women’s marital love. Clinical and policy implications are discussed.

Keywords: African American marriage, religion, relationship quality, cultural resources

Religion is salient for many Black Americans—approximately 75% report that religion is very important in their lives (Masci, 2018)—and, both historically and currently, religion has been a central resource for Black families to cope with stress and oppression (Poole, 1990). Theoretical and qualitative work has focused on the use of religion as a coping strategy among strong Black couples during midlife to advance understanding of the marital experiences of Black couples and inform programs to mitigate high rates of relationship instability in this population (Chaney et al., 2016; Millett et al., 2018). The present study builds on this literature to investigate the role of religious coping among Black couples in one key domain of marital quality, marital love. Specifically, we used a dyadic longitudinal approach with a racially homogenous sample to examine positive and negative religious coping as predictors of changes in Black husbands’ and wives’ marital love over a two-year period and test the role of spouse gender in these patterns.

Religion and Marital Relationships

Religiosity is generally related to better marital outcomes (Lakatos & Martos, 2019). Religion can directly benefit intimate relationships by fostering relationship commitment and investment, encouraging affection and positive perceptions of the relationship, and discouraging harmful behaviors such as harboring resentment towards a spouse (Wolfinger & Wilcox, 2008). Religiosity can also indirectly enhance relationships through fostering psychological well-being and the exchange of social support between spouses (Wolfinger & Wilcox, 2008).

In addition to its role in promoting relationship stability (e.g., Brown et al., 2008), religiosity is positively associated with relationship quality, including among Black couples. A cross-sectional study of married and engaged Black couples found that self-reported spirituality was related to greater perceived marital satisfaction for both self and partner and that husbands’ religiosity was positively associated with marital satisfaction for both spouses (Fincham et al., 2011). A longitudinal study of married and unmarried parents from urban areas (Wolfinger & Wilcox, 2008) also found that fathers’, but not mothers’, religious attendance predicted higher levels of perceived relationship quality and partner supportiveness two and a half years later. Religiosity is especially likely to influence marital love (i.e., feelings of belongingness, interdependence, closeness, attachment; Braiker & Kelley, 1979), as many religions endorse love as a primary principle and encourage spouses to act in a loving manner. Love also is considered to be a defining element of romantic relationships and has been linked to relationship satisfaction and stability, and, among Black couples, co-parenting quality (Brown, 2019; Riina & McHale, 2015). In one study, Black couples reported that their faith enhanced their love for their spouse and children (Millett et al., 2018), and a nationally representative study found that ethnic minority individuals experienced more expressed love than did Whites at higher levels of perceived spousal religiosity (Perry, 2016).

In this study, we focused on religious coping—one dimension of religiosity that may impact relationship adjustment. Religious coping is a multidimensional construct that encompasses religiously-based cognitions, behaviors, and practices to manage the perceptions or consequences of undesirable or threatening situations (Chatters et al., 2008; Pargament et al., 1998). Religious coping includes both positive and negative strategies. Positive religious coping reflects a sense of spiritual connectedness and a secure attachment with a higher power, involving multiple strategies such as prayer or benevolent religious reappraisals (i.e., redefining stressful events as benevolently intended by a higher power; Pargament et al., 1998). Negative religious coping reflects a tenuous, insecure attachment with a higher power and struggle to find meaning in difficult situations, involving strategies such as punishing God reappraisals (i.e., viewing negative situations as a punishment from God) or feelings of abandonment by God (Pargament et al., 1998). Generally, positive religious coping is related to better individual adjustment (e.g., well-being and mental health), and negative religious coping is related to poorer adjustment (Park et al., 2018). Research also suggests that religious coping may be related to relational adjustment. Among married Canadian couples, positive religious coping was associated with higher levels of marital satisfaction among men, and negative religious coping was associated with lower levels of marital satisfaction among women who self-identified as very religious (Tremblay et al., 2002).

Extant research highlights the salience of religious coping for Black Americans. Findings from the National Survey of American Life showed that Black Americans (both African Americans and Caribbeans) were more likely than Whites to endorse the importance of religious coping (Chatters et al., 2008). Additionally, almost 90% of African Americans and 86% of Black Caribbeans reported that prayer was an important source of coping when dealing with stress and that they looked to God for strength, support, and guidance (Chatters et al., 2008). Further, the use of religious coping is associated with psychological well-being for Black Americans. A national longitudinal study (Park et al., 2018) found that positive religious coping was related to improvements in psychological well-being over time and that negative coping was related to declines in well-being over time. McCleary-Gaddy and Miller (2018) further demonstrated that negative religious coping fully mediated the relation between perceived prejudice and psychological distress among Black Americans.

We expand this research to examine the prospective effects of religious coping on Black couples’ marital quality. Black couples experience relatively high rates of marital dissolution, and consistent with patterns in other groups, exhibit decreases in relationship quality over time (Barton & Bryant, 2016). Prior literature suggests that religious coping may be protective for Black couples’ relationship quality and contribute to relationship stability. On a conceptual level, the sociocultural family stress model (McNeil Smith & Landor, 2018) posits that religion is an important coping resource for Black families, providing the means to manage living in a continuously oppressive environment by instilling a sense of hope and strength. Findings from several qualitative studies of strong, enduring Black intimate relationships are consistent with this model’s tenets in documenting that spouses often report their reliance on faith and belief in God as integral to the continued stability and quality of their marriages and a support in overcoming the challenges they encountered throughout their relationships (Chaney et al., 2016; Millett et al., 2018). These descriptions of reliance on religion over the course of marriage suggest that religion may be an effective coping resource for Black couples to maintain positive relationships over time.

In this study, we extended prior research to examine the implications of religious coping for longitudinal trajectories of couples’ marital love. In doing so, we also aimed to contribute to the literature, which has often relied on cross-sectional designs and analyses conducted separately for men and women, by using a longitudinal dyadic data analytic approach. Interdependencies between spouses direct attention to the connections that exist between spouses’ religious coping and marital experiences.

Gender Differences in the Effects of Religiosity

Finally, we tested the role of gender in the effects of religious coping on marital love over time. Black women report stronger religious beliefs and more religious participation than Black men (Cox & Diamant, 2018). Additionally, among Blacks, there is a gender divide in the use of religious coping, with women more likely than men to endorse the importance of religious coping (Chatters et al., 2008). Nevertheless, the abovementioned study by Fincham and colleagues (2011) documents the impact of Black husbands’ religiosity on both partners’ marital experiences. Given some families endorse the tradition of men being the “spiritual leader” of the household (Carolan & Allen, 1999), husbands’ religious coping may have implications for the course of their partners’ as well as their own trajectories of marital love. The gender differences in the use of religious coping coupled with gender differences in the effects of religiosity on marital outcomes led us to test whether gender moderated the effects of religious coping in predicting changes in one’s own and one’s spouse’s marital love over time.

Current Study

In sum, the current study aimed to investigate the effects of positive and negative religious coping on the trajectories of marital love among Black couples using a dyadic, longitudinal approach and test whether these effects differed by gender. We hypothesized that: (1) positive religious coping would be related to higher and/or increasing levels of love over time for both partners and this effect would be stronger for husbands, and (2) negative coping would be related to lower and/or decreasing levels of marital love over time for both partners, and this effect would be stronger for husbands.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Data for this investigation came from a longitudinal study of Black families beginning in 2002 and involved three annual waves of data collection (see McHale et al., 2006 for additional details). Families that self-identified as African American or Black, included cohabitating mother and father figures, and had at least two adolescent-age children (either biological or non-biological) in the home were recruited from communities proximal to two cities in the mid-Atlantic region of the United States. Half of the participating families were contacted by local Black recruiters via churches, businesses, and community organizations and events. The remaining families were contacted via a mailing list purchased from a marketing firm that identified families with children in grades four to seven.

Of the original 202 families who participated in the study, parents not in a romantic relationship (e.g., mother-grandfather pairs), couples in cohabitating relationships, and couples who divorced before the start of the study were omitted to increase the sample’s homogeneity. Thus, the sample for the current project included 161 married Black couples (322 individuals). At Time 1, the mean ages of husbands and wives were 43.39 years (SD = 6.49) and 40.76 years (SD = 5.21), respectively. The median annual family income for these primarily dual-earner families was $90,000. On average, couples had been married for 13.80 years (SD = 5.96). Throughout the study, seven couples withdrew but did not differ significantly from other families on any of the study variables measured at the start of the study (ps > .09). Thus, their data were retained in the current analyses.

Data were collected annually via in-home interviews that lasted 2-3 hours and were conducted by teams of two interviewers; almost all interviewers were Black. All interviews began with informed consent procedures and, relevant to the current study, couples completed measures on religiosity and marital love. Families received a $200 honorarium for participation at each wave. The Institutional Review Board at the Pennsylvania State University approved all study protocols and procedures, and all participants provided written informed consent.

Measures

Marital Love

Marital love was assessed at each time point using the love subscale from the Relationships Questionnaire (Braiker & Kelley, 1979). Spouses rated their marital love during the past year (e.g., “How close do you feel to your partner right now?”) via nine items using a 9-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 9 (Very much). Items were summed, with total possible scores ranging from 9 to 81. Higher scores reflected greater marital love. The between-person reliability (Hox et al., 2010) for this repeated measure was .84 for husbands and .81 for wives.

Religious Coping

Religious coping was assessed at Time 1 using four items from the Brief Multidimensional Inventory of Religiousness/Spirituality (Fetzer Institute, 1999). Three items indexed positive religious coping (e.g., “I look to God for strength, support, and guidance”), and one item indexed negative religious coping (“I wonder whether God has abandoned me.”).1 Participants rated items using a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (Not at all) to 4 (A great deal). Items for positive religious coping were summed, resulting in total possible scores ranging from 3 to 12. For negative coping, possible scores ranged from 1 to 4. For both positive and negative coping, higher scores reflect greater religious coping. For positive religious coping, Cronbach’s alpha was .75 for husbands and .73 for wives.

Covariates

Given that socioeconomic status has been linked with marital outcomes, covariates tested in preliminary models included family income as well as spouses’ ages and relationship duration.

Data Analysis

Bivariate correlations were calculated, and effect sizes were interpreted consistent with Cohen’s (1998) recommendations for small (.10), medium (.30), and large (.50) effects. To investigate the effect of religious coping on changes in husbands’ and wives’ marital love over time, we applied growth curve modeling in an Actor-Partner Interdependence Modeling framework (Kenny et al., 2006). This model accounts for the interdependence between husbands’ and wives’ outcomes and permits the simultaneous estimation of actor effects (i.e., the effect of one’s religious coping on the trajectory of one’s marital love) as well as partner effects (i.e., the effect of the partner’s religious coping on the trajectory of one’s marital love) within the same model.

Given the clustered nature of the data, models were estimated via multilevel modeling (MLM) wherein time (i.e., assessment wave) was nested within dyad. Analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) using PROC MIXED. Positive and negative religious coping strategies were tested as simultaneous predictors of changes in each partner’s marital love. Random effects were included for the effects of time. To obtain separate estimates for the two actor effects (husbands, wives) and two partner effects (wives, husbands), we employed a two-intercept approach (Kenny et al., 2006), wherein effects for husbands and wives were estimated simultaneously and respectively in the same model. In this model, husbands’ and wives’ intercepts and slopes were allowed to vary randomly across dyads and covary within dyads. We also specified a heterogeneous compound symmetry covariance structure to allow for the correlation of husbands’ and wives’ residuals at each time point (Campbell & Kashy, 2002). To examine the trajectories of marital love and test whether religious coping predicted longitudinal changes in marital love, we first estimated an unconditional growth curve model, in which only a linear term for time was included at Level 1 (Model 1). Thus, for Model 1, husbands’ (H) and wives’ (W) scores on marital love are a function of their dyad membership, i and time, t:

where represents the time variable (centered at Time 1), and are the intercepts for husband and wife, respectively, and and are the slope for husband and wife, respectively, in couple i. Participants’ ages, marital duration (in years), and family income (log-transformed)—all assessed at Time 1—were initially entered as covariates in the model. However, because none predicted the outcome variables (ps > .28) and the pattern of results was the same with or without them, covariates were removed from the final models to increase model parsimony.

In Model 2, we included cross-level interactions between religious coping and time

to test whether the trajectory of marital love differed as a function of actors’ (A) and partners’ (P) positive religious coping (pos coping) and negative religious coping (neg coping). Significant interactions were probed at 1.5 SD above and below the mean. We also conducted a regions of significance analysis (RoS) to determine the levels of religious coping at which the effects of time were significant using an online computational tool for interaction effects in MLM (http://www.quantpsy.org; Preacher et al., 2006). When the two-intercept model suggested that an actor or partner effect was significant for one gender but not the other, gender differences were formally compared by using the interaction approach. Specifically, we estimated an average effect for husbands and wives and the gender difference in that effect by including an interaction with gender (effect-coded).

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations, and correlations between study variables. For this community sample, marital love was high for both husbands and wives, and reports, both within and across spouses, were correlated across time. Husbands and wives did not significantly differ in levels of marital love at any of the time points (ps > .05). Overall, positive coping was high and negative coping was low. Correlations within and between spouses’ religious coping were generally small and non-significant, except for a significant positive association between husbands’ and wives’ positive coping. Wives reported engaging in significantly more positive coping, t(153) = 2.06, p = .04. Husbands’ reports of positive and negative religious coping were significantly correlated with their feelings of love across time points, and wives’ reports of positive and negative religious coping were significantly correlated with their feelings of love at Time 1. For marital love, the intraclass correlation was .64 for husbands and .59 for wives, indicating 36% and 41% of the variability in marital love was due to change over time, respectively.

Table 1.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations between Wives’ and Husbands’ Marital Love and Religious Coping

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | M | SD | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. W Love T1 | – | 69.69 | 11.76 | ||||||||

| 2. W Love T2 | .64 * | – | 69.69 | 12.83 | |||||||

| 3.W Love T3 | .64 * | .74 * | – | 68.74 | 12.86 | ||||||

| 4. H Love T1 | .55 * | .39 * | .36 * | – | 71.29 | 10.30 | |||||

| 5. H Love T2 | .43 * | .52 * | .49 * | .68 * | – | 70.58 | 11.06 | ||||

| 6. H Love T3 | .44 * | .44 * | .63 * | .65 * | .69 * | – | 70.11 | 11.28 | |||

| 7.W PRC | .22 * | .06 | .10 | .12 | .09 | .15 | – | 9.93 | 2.00 | ||

| 8. H PRC | .17 * | .05 | .07 | .19 * | .25 * | .30 * | .19 * | – | 9.53 | 2.18 | |

| 9. W NRC | −.31 * | −.07 | −.07 | −.14 | −.22 * | −.09 | −.13 | .03 | – | 1.18 | 0.55 |

| 10. H NRC | −.10 | −.09 | −.09 | −.18 * | −.14 | −.09 | .01 | .08 | .00 | 1.16 | 0.54 |

Note. W = Wives; T1 = Time 1; T2 = Time 2; T3 = Time 3; H = Husbands; PRC = Positive religious coping; NRC = Negative religious coping.

p < .05

Actors’ and Partners’ Religious Coping Strategies as Predictors of Changes in Marital Love

Table 2 presents the results from the growth curve models with positive and negative religious coping predicting subsequent changes in marital love over time. Results from Model 1 (i.e., the trajectories of marital love) indicated that husbands’, but not wives’, marital love significantly decreased over the study period. However, follow-up analyses using the interaction approach indicated that husbands’ and wives’ trajectories did not significantly differ from each other (B = −0.14, SE = 0.22, p = .525).

Table 2.

Longitudinal Actor-Partner Interdependence Models Predicting Marital Love from Actors’ (A) and Partners’ (P) Positive and Negative Religious Coping

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercepts | B | SE | B | SE | |

| Wifea | 69.64* | 0.95 | 69.64* | 0.94 | |

| Husbandb | 71.28* | 0.83 | 71.26* | 0.80 | |

| Time x wife | −0.71† | 0.42 | −0.66† | 0.40 | |

| Time x husband | −0.98* | 0.39 | −0.78† | 0.39 | |

| A positive religious coping x wife | 0.49 | 0.48 | |||

| A positive religious coping x husband | 0.97 | 0.37 | |||

| P positive religious coping x wife | 0.66 | 0.43 | |||

| P positive religious coping x husband | 0.25 | 0.41 | |||

| A negative religious coping x wife | −5.17* | 1.75 | |||

| A negative religious coping x husband | −3.76* | 1.45 | |||

| P negative religious coping x wife | −2.33 | 1.71 | |||

| P negative religious coping x husband | −3.18* | 1.49 | |||

| A positive religious coping x time x wife | −0.20 | 0.20 | |||

| A positive religious coping x time x husband | 0.38* | 0.18 | |||

| P positive religious coping x time x wife | −0.02 | 0.18 | |||

| P positive religious coping x time x husband | 0.01 | 0.20 | |||

| A negative religious coping x time x wife | 3.16* | 0.75 | |||

| A negative religious coping x time x husband | 1.04 | 0.74 | |||

| P negative religious coping x time x wife | 0.98 | 0.76 | |||

| P negative religious coping x time x husband | 0.50 | 0.73 | |||

| Random Effects | |||||

| Intercept | Wives | 106.26* | 16.12 | 100.20* | 15.35 |

| Husbands | 77.65* | 12.38 | 65.70* | 10.92 | |

| Cross-partner correlation | .64* | .59* | |||

| Slope | Wives | 9.08† | 4.85 | 14.47* | 4.63 |

| Husbands | 5.56 | 4.24 | 8.11* | 3.82 | |

| Cross-partner correlation | .39 | .31† | |||

| Residual | Wives | 44.64* | 4.56 | 36.26* | 3.88 |

| Husbands | 35.57* | 3.96 | 33.89* | 3.56 | |

| Cross-partner correlation | .34* | .29* | |||

Note. a Wife: 0 = husband, 1 = wife. b Husband: 1 = husband, 0 = wife. † p < .10. * p < .05.

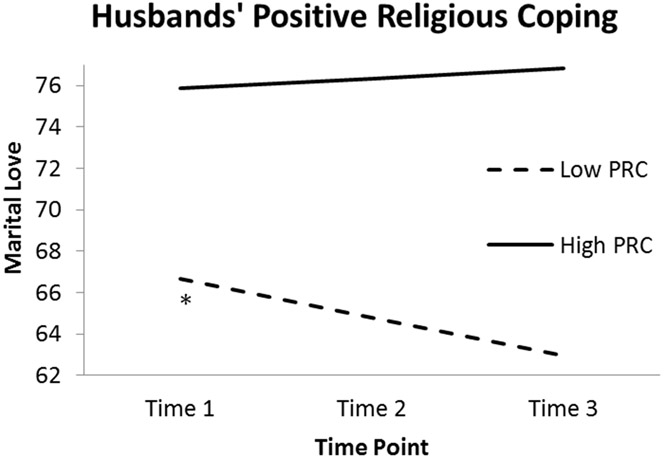

Results from Model 2, which tested whether religious coping moderated trajectories of marital love over time, revealed two significant interactions involving actor effects. First, a significant interaction emerged between husbands’ positive religious coping and time. As displayed in Figure 1, post hoc probing indicated that husbands who reported more positive religious coping (1.5 SD above the mean) at Time 1 showed stable levels of marital love over time (B = 0.40, SE = 0.71, p = .577), whereas husbands who endorsed lower levels of positive religious coping (1.5 SD below the mean) exhibited a significant decrease in love over time (B = −2.11, SE = 0.70, p = .003). RoS analysis showed that love declined for husbands who reported positive religious coping scores below 9.74. There was no evidence that wives’ trajectories of love differed as a function of positive religious coping (p = .313); follow-up analyses confirmed a significant gender difference in the moderating effect of actors’ positive religious coping on trajectories of love (B = 0.29, SE = 0.14, p = .037). Thus, Hypothesis 1 was partially supported, as husbands reported decreasing marital love over time when they engaged in lower levels of positive religious coping, but positive religious coping did not significantly predict changes in wives’ marital love.

Figure 1.

Interaction among time, actors’ positive religious coping, and gender predicting actors’ marital love for husbands.

Note. PRC = Positive religious coping. * p < .05

Second, a significant interaction emerged between wives’ negative religious coping and time. As displayed in Figure 2, post hoc probing indicated that wives who endorsed lower levels of negative religious coping initially exhibited higher levels of love but experienced significant decreases over time (B = −3.26, SE = 0.73, p < .001). In contrast, wives who reported higher levels of negative religious coping initially reported lower levels of love but exhibited increases over time (B = 1.93, SE = 0.73, p =.009). RoS analysis indicated that love significantly declined over time for wives with negative religious coping scores below 1.14 and significantly increased for wives with scores above 1.75. There was not a significant difference in husbands’ reports of love over time as a function of negative religious coping; follow-up analyses indicated a significant gender difference in the effect of actors’ negative religious coping on the trajectory of love (B = −1.06, SE = 0.52, p = .043). Thus, Hypothesis 2 was not supported. Wives reported decreasing marital love over time when they engaged in less negative religious coping, and negative religious coping was not linked to changes in marital love for husbands.

Figure 2.

Interaction among time, actors’ negative religious coping, and gender predicting actors’ marital love for wives.

Note. NRC = Negative religious coping. * p < .05

Sensitivity Analysis

We re-ran the analyses using the 2-item measure of negative religious coping, and the pattern of results was identical. Specifically, when using the 2-item measure, there was a significant interaction between wives’ negative religious coping and time (B = 1.40, SE = 0.41, p = .001). Probing of the interaction indicated that wives who endorsed lower levels of negative coping experienced decreasing marital love (B = −2.86, SE = 0.74, p < .001), whereas wives with higher levels of negative religious coping experienced increasing love (B = 1.57, SE = 0.77, p = .042).

Discussion

This study investigated the effect of religious coping on the longitudinal course of marital love among Black couples in a dyadic context and tested the role of gender in these associations. Results indicated that husbands who endorsed higher levels of positive religious coping reported higher and more stable levels of marital love over time. Contrary to our hypothesis, wives who engaged in lower levels of negative religious coping reported declines in marital love over time, whereas those who engaged in higher levels reported increases in marital love over time.

This is the first study to document a link between religious coping and trajectories of marital love, while simultaneously accounting for and comparing the experiences of both husbands and wives. These results add both substantively and methodologically to the literature on the role of religiosity in Black couples’ marital quality. As such, this investigation addresses the need for more research on Black couples and families in a way that attends to culturally relevant resources via its focus on religious coping mechanisms (McNeil Smith & Landor, 2018). Given the sociohistorical context of Blacks in the U.S., religion has been an important institution for Black families. Throughout times of slavery, emancipation, the civil rights movement, and into the present, religion has been intertwined with Black Americans’ efforts to combat injustices, threats, and challenging circumstances that jeopardize family life (Poole, 1990). In this way, Black Americans have utilized religion as both a social institution (e.g., the Black Church) to fight against societal-level threats and as an individual coping mechanism to help preserve and protect the quality of their intimate relationships. The current findings regarding the effects of religious coping on marital love among Black couples in midlife are especially notable, given that love is related to relationship stability and that decreases in relationship quality typically occur over time (Brown, 2019; Barton & Bryant, 2016).

Interestingly, we found no partner effects of religious coping on marital love over time. As such, religious coping seems to operate more as an individual-level characteristic that has implications for husbands’ and wives’ own experiences of love rather than as a couple-level resource that affects both partners’ outcomes over time. This may be because measures of religious coping include reassessing cognitive appraisals and reframing perceptions in one’s own mind. Indeed, current conceptualizations and measurements of religious coping have focused on the religious practices enacted by individuals and have not tended to include communal activities performed by spouses within a dyadic context, such as engaging in prayer together or co-creating a narrative for the role of religion and/or a higher power in their lives. Future qualitative and quantitative research should investigate the extent to which Black couples may also perceive religious coping as a dyadic phenomenon, perhaps by incorporating the construct of joint dyadic coping as conceptualized within the systemic transactional theory of couples coping with stress (e.g., Bodenmann, 2005).

Husbands’ Positive Religious Coping

As hypothesized, husbands who engaged in more positive religious coping at baseline reported higher and more stable levels of marital love over time. Conversely, husbands who engaged in lower levels of positive religious coping exhibited significant decreases in marital love over time. Positive religious coping may provide a means to deal with stress that allows husbands greater availability to invest effort and energy in their relationships, resulting in positive cascading effects over time. The gender difference in the effect of positive coping on marital quality observed in this study is consistent with previous research documenting the importance of husbands' religiosity for relationship quality (Wolfinger & Wilcox, 2008). That their positive religious coping had a significant effect on changes in marital love for themselves but not their wives may be due to gender socialization that deters men from pursuing relational intimacy (Wolfinger & Wilcox, 2008). Religion, however, is an institution that encourages men to attend to their close relationships and families in addition to focusing on their relationship with God. Thus, engaging in more positive religious coping may raise the salience of marriage for husbands, resulting in husbands having “more realistic expectations of their partners, view[ing] their relationship in a spiritual light that makes them look more favorably on their partners, or feel[ing] more secure in their relationships” (Wolfinger & Wilcox, 2008, p. 20).

Wives’ Negative Religious Coping

Contrary to our hypothesis, wives who reported engaging in lower levels of negative religious coping exhibited significant declines from their relatively higher levels of marital love at baseline. This finding should be interpreted in light of the generally low levels of negative religious coping in this sample. In this context, this suggests that lower levels of negative religious coping may not protect against declines in women’s marital love over time. In contrast, wives who endorsed more negative religious coping initially reported lower levels of love at baseline but exhibited increases in love over time. It may be that among women who endorse relatively higher levels of negative religious coping, the use of negative coping may have limited beneficial relational effects—a finding inconsistent with prior literature demonstrating the harmful effects of negative religious coping for individual adjustment (Park et al., 2018). One explanation for this counterintuitive finding is that women’s lower levels of negative religious coping may reflect a self-silencing phenomenon (e.g., the sense that women cannot openly express their frustrations and spiritual discontent), negatively impacting their perceptions of marital love over time. Given the patriarchal nature of many religious faiths, freedom to express their discontent and possibly even share their feelings with their spouse could provide women with a sense of security and safety in their relationships, promoting feelings of love. Greater use of negative religious coping could also reflect a relatively differentiated and deeper self-awareness. Given the current findings’ divergence from the literature demonstrating the harmful effects of negative religious coping for individual adjustment and our use of a single-item measure, additional research is necessary to replicate and reconcile the linkages among negative religious coping, relationship quality, and individual well-being in this population. For instance, negative coping had a relatively small effect on the trajectories of women’s marital love, which may be attributable to measuring religious coping only at baseline. Religious coping represents a wide range of behaviors and practices that can vary over time, and this variability may be coupled with marital love over time. Longitudinal assessment of both religious coping and love could help to clarify the consistency of the association between negative religious coping and love or whether the effects we documented reflect regression to the mean.

Clinical and Policy Implications

In light of the unique marital trends among Black Americans — specifically, lower rates of marriage (33% of Black adults) and marital quality and higher rates of divorce (Bulanda & Brown, 2007; Horowitz, 2019)—examination of factors such as religious coping may yield important public health implications for this population and ultimately contribute to the stability of Black marriages. Practitioners and clergy working with Black couples should consider couples’ use of religious coping. Further, relationship education and prevention/intervention programs that include religious components to promote Black romantic relationship quality may be enhanced by considering aspects of religious coping in addition to general religious practices (e.g., the Program for Strong African American Marriages; Hurt et al., 2012). Current church- and faith-based intervention programs for Black couples may be able to further enhance their effectiveness by attending to spouses’ use of both positive and negative religious coping and how this may differ between men and women. Additionally, policy initiatives encouraging the transition to marriage or promoting Black couples’ relationship outcomes may benefit from collaborating with religious institutions and disseminating their resources via local religious centers (Vaterlaus et al., 2015).

Limitations, Future Directions, and Conclusions

In addition to providing substantive insights regarding the role of religious coping in Black marriages, this study adds to the literature through its racially homogenous design, which facilitates the detection of factors that account for variability among Black families. It also applies a dyadic, longitudinal approach to account for potential interdependence between partners’ feelings of marital love and simultaneously investigates both actor and partner effects of religious coping on changes in each partner’s love over time. However, study limitations also suggest directions for future research. First, this study relied exclusively on self-report data, which could have inflated the associations between some of the study variables due to shared method variance. Second, we focused on mixed-gender couples from a relatively economically and educationally advantaged community sample drawn from one geographic region of the United States. Future studies should include more diverse samples to determine the generalizability of our results. Third, we relied on one item to assess negative religious coping. Single-item measures have been shown to be a valid and useful measurement tool that eases participant burden and enhances interpretation of results (Bowling, 2005), and findings in the current study were consistent when a two-item measure was employed. Nonetheless, future studies using an array of items to assess this construct may limit measurement error and thereby increase the likelihood of detecting effects. Lastly, religious coping was measured as a time-invariant predictor. Given the multidimensional nature of religious coping and previous research demonstrating that levels of religious coping change over time (Holt et al., 2017), additional research should examine the contemporaneous associations between religious coping and marital adjustment across multiple time points.

This study built on previous research to examine the longitudinal effects of positive and negative religious coping on the marital love of Black married couples. Our results highlight the complex connections linking religious coping and relationship quality among Black husbands and wives and how religious coping may serve as a resource for Black couples and families. Future research that further clarifies how religious coping is related to marital quality will expand the literature on Black cultural resources, providing additional insights into processes that contribute to the well-being and stability of Black families.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by grant R01 HD32336 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development to Susan M. McHale, grant F31 MD015215 from the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities to August I. C. Jenkins, the Karl R. Fink and Diane Wendle Fink Early Career Professorship for the Study of Families to Steffany J. Fredman, and grants KL2 TR002015 and UL1 TR002014 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Science to support Steffany J. Fredman’s time. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Results of this study were presented at the 2019 conference for the National Council on Family Relations, Fort Worth, TX.

Footnotes

In the larger study, three items indexed negative religious coping (“I feel God is punishing me for my sins or lack of spirituality; I wonder whether God has abandoned me; I try to make sense of the situation and decide what to do without relying on God.”). However, the subscale’s internal consistency was poor (husbands: α = .50; wives: α = .59). After dropping the item pertaining to not relying on God, alphas improved but were still poor (husbands: α = .57; wives: α = .66). Consequently, we used a single item related to abandonment by God to represent negative religious coping, as this item has been identified as an exemplar of spiritual discontentment (Pargament et al., 1998).

References

- Barton AW, & Bryant CM (2016). Financial strain, trajectories of marital processes, and African American newlyweds’ marital instability. Journal of Family Psychology, 30(6), 657–664. 10.1037/fam0000190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bodenmann G (2005). Dyadic coping and its significance for marital functioning. In Revenson TA, Kayser K, & Bodenmann G (Eds.), Couples coping with stress: Emerging perspectives on dyadic coping (pp. 33–50). American Psychological Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A (2005). Just one question: If one question works, why ask several? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(5), 342–345. 10.1136/jech.2004.021204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braiker HB, & Kelley HH (1979). Conflict in the development of close relationships. In Burgess RL & Huston TL (Eds.), Social exchange in developing relationships (pp. 135–168). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown E, Orbuch TL, & Bauermeister JA (2008). Religiosity and marital stability among Black American and White American couples. Family Relations, 57(2), 186–197. 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2008.00493.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown J (2019). The potent cocktail of love, intimacy, sex, and power: An assessment pyramid for couples therapy. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. Advance online publication. 10.1080/14681994.2019.1682540 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bulanda JR, & Brown SL (2007). Race-ethnic differences in marital quality and divorce. Social Science Research, 36(3), 945–967. 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2006.04.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell L, & Kashy DA (2002). Estimating actor, partner, and interaction effects for dyadic data using PROC MIXED and HLM: A user-friendly guide. Personal Relationships, 9(3), 327–342. 10.1111/1475-6811.00023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carolan MT, & Allen KR (1999). Commitments and constraints to intimacy for African American couples at midlife. Journal of Family Issues, 20(1), 3–24. 10.1177/019251399020001001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chaney C, Shirisia L, & Skogrand L (2016). "Whatever God has yoked together, let no man put apart:” The effect of religion on Black marriages. Western Journal of Black Studies, 40(1), 24–41. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-471850015/whatever-god-has-yoked-together-let-no-man-put-apart [Google Scholar]

- Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, Jackson JS, & Lincoln KD (2008). Religious coping among African Americans, Caribbean Blacks, and Non-Hispanic Whites. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(3), 371–386. https://doi.org/10.1 10.1002/jcop.20202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1998). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum Associates. [Google Scholar]

- Cox K, & Diamant J (2018, September 26). Black men less religious than black women, but more religious than white women, men. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/26/black-men-are-less-religious-than-black-women-but-more-religious-than-white-women-and-men/ [Google Scholar]

- Fetzer Institute. (1999). Multidimensional measurement of religiousness/spirituality for use in health research: A report of the Fetzer Institute/National Institute on Aging. https://fetzer.org/resources/multidimensional-measurement-religiousnessspirituality-use-health-research [Google Scholar]

- Fincham FD, Ajayi C, & Beach SRH (2011). Spirituality and marital satisfaction in African American couples. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 3(4), 259–268. 10.1037/a0023909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holt CL, Roth DL, Huang J, Park CL, & Clark EM (2017). Longitudinal effects of religious involvement on religious coping and health behaviors in a national sample of African Americans. Social Science and Medicine, 187, 11–19. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.06.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hox JJ, Moerbeek M, & van de Schoot R (2010). Multilevel analysis: Techniques and applications. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Horowitz J, Graf N, & Livingston G (2019, November 6) Marriage and cohabitation in the U.S. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/wp-content/uploads/sites/3/2019/11/PSDT_11.06.19_marriage_cohabitation_FULL.final_.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Hurt TR, Beach SRH, Stokes LA, Bush PL, Sheats KJ, & Robinson SG (2012). Engaging African American men in empirically based marriage enrichment programs: Lessons from two focus groups on the ProSAAM project. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18(3), 312–315. 10.1037/a0028697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny DA, Kashy DA, & Cook WL (2006). Dyadic data analysis. Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lakatos C, & Martos T (2019). The role of religiosity in intimate relationships. European Journal of Mental Health, 14(2), 260–279. 10.5708/EJMH.14.2019.2.3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Masci D (2018, February 7). 5 facts about the religious lives of African Americans. Pew Research. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/02/07/5-facts-about-the-religious-lives-of-african-americans/ [Google Scholar]

- McCleary-Gaddy AT, & Miller CT (2018). Negative religious coping as a mediator between perceived prejudice and psychological distress among African Americans: A structural equation modeling approach. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 11(3), 257–265. 10.1037/rel0000228 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McHale SM, Crouter AC, Kim JY, Burton LM, Davis KD, Dotterer AM, & Swanson DP (2006). Mothers’ and fathers’ racial socialization in African American families: Implications for youth. Child Development, 77(5), 1387–1402. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00942.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNeil Smith S, & Landor AM (2018). Toward a better understanding of African American families: Development of the sociocultural family stress model. Journal of Family Theory and Review, 10(2), 434–450. 10.1111/jftr.12260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Millett MA, Cook LE, Skipper AD, Chaney CD, Marks LD, & Dollahite DC (2018). Weathering the storm: The shelter of faith for Black American Christian families. Marriage & Family Review, 54(7), 662–676. 10.1080/01494929.2018.1469572 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith BW, Koenig HG, & Perez L (1998). Patterns of positive and negative religious coping with major life stressors. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 37(4), 710–724. https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/1388152.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Park CL, Holt CL, Le D, Christie J, & Williams BR (2018). Positive and negative religious coping styles as prospective predictors of well-being in African Americans. Psychology of Religion and Spirituality, 10(4), 318–326. 10.1037/rel0000124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry SL (2016). Perceived spousal religiosity and marital quality across racial and ethnic groups. Family Relations, 65(2), 327–341. 10.1111/fare.12192 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Poole TG (1990). Black families and the Black church: A sociohistorical perspective. In Cheatham HE & Stewart JB (Eds.), Black Families (pp. 33–48). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, Curran PJ, & Bauer DJ (2006). Computational tools for probing interactions in multiple linear regression, multilevel modeling, and latent curve analysis. Journal of Educational and Behavioral Statistics, 31(4), 437–448. 10.3102/10769986031004437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Riina EM, & McHale SM (2015). African American couples’ coparenting satisfaction and marital characteristics in the first two decades of marriage. Journal of Family Issues, 36(7), 902–923. 10.1177/0192513X13495855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay J, Sabourin S, Lessard J-M, & Normandin L (2002). Predictive value of self-differentiation and religious coping strategies in a study of marital satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Behavioural Science, 34(1), 19–27. 10.1037/h0087151 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vaterlaus JM, Skogrand L, & Chaney C (2015). Help-seeking for marital problems: Perceptions of individuals in strong African American marriages. Contemporary Family Therapy, 37(1), 22–32. 10.1007/s10591-014-9324-4 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfinger NH, & Wilcox WB (2008). Happily ever after? Religion, marital status, gender and relationship quality in urban families. Social Forces, 86(3), 1311–1337. 10.1353/sof.0.0023 [DOI] [Google Scholar]