Abstract

Ensuring that mental health professionals are appropriately trained to provide affirming and sensitive care to transgender and gender diverse (TGD) adults is one mechanism that may reduce the marginalization sometimes experienced by TGD adults in mental health contexts. In this study, mental health professionals (n=142) completed an online survey documenting the sources and types of training received to provide TGD-sensitive care; and, shared a self-assessment of their comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care. Findings revealed that the majority of the mental health professionals in the study (approximately 81%) received specific training to work with TGD clients from a variety of sources. These mental health professionals also self-reported high levels of comfort, competence, and ability to offer TGD-sensitive care which were statistically significantly associated with the number of hours of TGD-specific training they had received.

Keywords: transgender and gender diverse (TGD), mental healthcare, education, training

Introduction

The necessity of improving access to quality mental health services for transgender and gender diverse (TGD) persons continues to be documented (Benson, 2013; Bockting et al., 2013; Dawson et al., 2017; Meyer et al., 2020). TGD adults, like cisgender adults, seek services from mental health professionals (e.g., psychologists, psychiatrists, clinical social workers, licensed mental health counselors) for a variety of concerns including anxiety, depression, stress, eating disorders, relationship problems and substance abuse (Bockting et al., 2013; Bouman et al., 2017; Dawson, 2017; James et al., 2016; Millet et al., 2016). TGD persons may also seek mental health services for gender-identity related reasons such as choices about gender affirmation procedures (e.g., hormones, surgery). According to the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey, TGD adults report levels of psychological distress eight times higher than that of the general U.S. population; and 40% of transgender adults have attempted suicide, a rate almost 10 times that of the general U.S. population (James et al., 2016). The suicide rate is more acute when TGD persons desire but are unable to access gender affirming medical care (Bauer et al., 2015). These observations reinforce the critical need for TGD persons to be able to access quality care from mental health professionals.

Unfortunately, empirical research and anecdotal evidence continue to reveal that some TGD adults may be marginalized when seeking general health care, as well as mental health care, leading to a reduction in engagement in care, avoidance of healthcare systems and poor health outcomes (Holt et al., 2019; Meyer et al., 2020; Puckett, et al., 2018; Strousma, 2014). The marginalization of TGD adults in general health care settings include being asked probing questions irrelevant to the issue for which they are seeking care, experiencing misgendering and misnaming, as well as outright refusal of care (Meyer et al., 2020; Puckett, et al., 2018). There are also reports of microaggressions by mental health professionals working with TGD clients including lacking basic knowledge about TGD experiences and clinical needs, excessively focusing on gender while ignoring other issues important to the client, stigma, refusal of care, and educational burdening whereby therapists rely on TGD clients to teach them about TGD-related issues (Mizock & Lundquist, 2016; Puckett et al, 2018; Shipherd, et al., 2010). Notably, these marginalizing experiences may be exacerbated by the intersection of other factors such as racial and ethnic identity, culture, language, age, ability, socioeconomic status, and place of residence (de Vries, 2012; White et al., 2020).

Experiences of marginalization in healthcare contexts in general, and mental health contexts specifically, may be due to the inadequacy of the training of professionals to provide TGD-sensitive care (Stryker et al., 2021). The term TGD-sensitive is used in this project as a broad term to capture all of the factors associated with the entire experience of accessing care including finding providers, setting up appointments, the ability to use chosen names and pronouns in healthcare contexts, as well as undergoing specific gender affirming procedures including hormones, hair removal and surgery. Notably, there has been limited research in the educational preparedness of health professionals to provide TGD-sensitive care, especially from the perspective of healthcare trainees and practicing healthcare providers (Greene, 2018; Stryker, 2021). Such work is warranted given that health professionals especially mental health professionals are sometimes the first persons TGD adults interact with in the general healthcare system (Riggs & Bartholomaeus, 2016). Studies that have examined educational preparedness to provide TGD-sensitive care across various health disciplines have identified knowledge gaps and barriers to care. For example, in a survey of 255 students at the University of British Columbia medical school 24% of students indicated that they felt the topic of transgender health was proficiently taught at their institution and only 6% of students felt knowledgeable to provide care for transgender persons (Chan et al., 2016). This study also identified curricular differences in teaching about transgender health at six Canadian medical schools both in the structure of the presentation of the information (e.g., standalone units vs. infused throughout courses) and time of introducing the topic (e.g., 1st year, 2nd year, 3rd, or 4th year of medical school) (Chan et al., 2016). A survey of internal medicine residents (n=67) in the U.S revealed that while the majority (97%) acknowledged the value of understanding transgender health, less than half of them (45%) had received specific training on transgender health (Johnston & Shearer, 2017). Likewise, a survey of 80 endocrinologists or endocrinology fellows indicated that 36% of them received training in transgender care but only 11% felt competent to provide transgender care (Irwig, 2016). A dearth in training to provide TGD-sensitive care has been reported in other specialties including obstetrics and gynecology (Unger 2015) plastic surgery and urology (Dy et al., 2016; Morrison et al., 2016; Morrison et al., 2017) as well as nursing (Abeln & Love, 2019; Carabez et al., 2015; Paradiso et al., 2018). Notably, however, there are several guidelines offered by professional organizations delineating the importance of training to provide TGD-sensitive care (ACA, 2010; APA, 2015; Coleman, 2012; TGNC guide, 2021).

Empirical research on the educational preparedness of mental health professionals to provide TGD-sensitive care appears limited as well (Stryker et al., 2021). Published research, however, reinforce the need for appropriate training. For example, in depth interviews with mental health professionals (n=8) revealed a paucity of resources and training to provide LGBT-sensitive care and recommended the inclusion of mandatory LGBT health content in training curricula (Rutherford et al., 2012). It should be noted that in this study transgender health was discussed under the broad term of LGBT health rather than as a separate topic. In a more recent survey, mental health professionals (n=250) reiterated the need for appropriate training to work with TGD clients recommending clinical experience (short-term or long-term), professional conferences and mentorship as possible avenues to access appropriate training (Stryker et al., 2021).

Therefore, our study was conducted in order to add the limited research available about training to provide TGD-sensitive care. This exploratory project investigated the TGD-specific training mental health professionals receive and documented the self-reported levels of comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care of mental health professionals caring for TGD clients. The specific research questions are:

Research Question 1: What type of TGD-sensitive training do mental health professionals receive in order to offer TGD- specific care?

Research Question 2: What are the self-reported levels of comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD- sensitive care of mental health professionals?

Materials and Methods

Data Collection Process

Mental health professionals who work with TGD clients were identified using systematic Google Chrome Incognito searches following the procedures developed by (Holt et al., 2019; Holt et al., 2021). The use of a search engine, like Google Chrome, is consistent with research methods used to collect online materials for content analysis and mimics the method TGDadults would use to find a health care provider (Deutsch, 2016; Goins & Pye, 2013). Recruitment of participants proceeded as follows. Google Incognito searches were conducted between May 2016 and September 2016 for 25 states in the U. S. These searches yielded approximately 1500 mental health professionals who advertise that they provide TGD-affirming care. Of the 1500 mental health professionals only 500 included a link to their professional websites; 249 of this subset of professionals participated in the study by Holt and colleagues (2019) which examined the TGD-affirming language on the professional websites and intake forms of these providers. The 249 providers who participated in the Holt and colleagues (2019) study were contacted via the emails provided on their professional websites to participate in the current study. Emails with a link to an online, Qualtrics survey were sent out to groups of 25 providers at a time (https://www.qualtrics.com). The survey was developed by the researchers in collaboration with the Trans Collaborations advisory board and did not include any existing scales. If a provider did not complete the survey, reminder emails were sent 8 and 16 days later if needed. Respondents provided informed consent electronically prior to beginning the online survey. Out of the 249 providers contacted via email, 145 completed the survey (response rate= 58%), and 89 participants (61%) filled out the link to receive a $5 Amazon gift card for participating in the study. Since this study focused exclusively on mental health professionals the surveys of three providers who indicated that they were general healthcare practitioners (n=l) and naturopathic providers (n=2) were removed prior to data analysis.

Data

The Qualtrics survey used in this study included demographic questions such as location of practice, number of years in practice and theoretical orientation as well as TGD-specific questions such as type of training, source of training, number of current TGD clients and the number of TGD clients the respondents had worked with within the past five years. Respondents were also asked to rate their comfort in providing services to TGD clients, their competence in providing care to TGD clients and their competence in providing TGD-sensitive care using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1= very uncomfortable or incompetent to 5 = very comfortable or competent. The survey took approximately 15 minutes to complete at the end of which participants were instructed to copy and paste a new link to enter their preferred email to obtain a $5 Amazon gift card. The separate link allowed the emails of the mental health professionals to remain separate from their survey responses, thereby ensuring anonymity of responses. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Nebraska at Kearney.

Data Analysis

Demographic information and sources and types of TGD-specific training were analyzed using frequencies. Spearman rank-order correlations were conducted to assess the relationships between number of years of experiences as a mental health professional; whether or not participants TGD-specific training, hours of TGD- specific training, sources of training, number of TGD clients within the past five years and number of current TGD clients on self-reported levels of comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care. Ordinal regression analyses were conducted to model the dependence of the polytomous ordinal variables of self-reported levels of comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care, on the predictors of number of years of experience as a mental health professional; whether or not participants had TGD- specific training, hours of TGD-specific training, sources of training, number of TGD clients within the past five years and percentage of current TGD clients.

Results

Table 1 illustrates the demographics of the providers including location of practice, discipline, practice setting, type of care, role in setting, theoretical orientation, years of experience. In summary, the majority of participants worked in urban locations (n=78; 54.9%), in private practice (n=93; 65.5%), identified their field of practice as mental health counseling (n=51; 35.9%); reported a variety of specific roles within their fields of practice including licensed clinical social worker and psychologist had ten to twenty years experience as a mental health professional (n=53; 37.3%), and had a variety of therapeutic theoretical orientations (refer to Table 1). Table 2 illustrates factors specific to training to work with TGD clients. In summary, the majority of participants completed TGD-specific training (n=l15; 81%), of more than 25 hours (n=53; 37.3%), from a variety of sources. In addition, the majority of participants indicated having more than 20 TGD clients within the past five years (n=62; 43.7%) and currently had 1–20% of their current clients as TGD persons (n=65; 45.8%) (refer to Table 2).

Table 1.

Provider Demographics

| Characteristic | Number of Providers (%) |

|---|---|

| Geographic Location of Practice | |

| Rural | 10 (7%) |

| Suburban | 53 (37.3% |

| Urban | 78 (54.9%) |

| Field of Practice | |

| Clinical Psychology | 27 (19%) |

| Counseling Psychology | 20 (14.1%) |

| Mental Health Counseling | 51 (35.9%) |

| Social Work | 25 (17.6%) |

| Other: clinical sexology, marriage/couple & family therapy, MD/PhD (pediatrics & counseling), professional counseling, psychiatry, substance use disorder counseling | 19 (13.4%) |

| Practice Settings | |

| Hospital | 1(0.7%) |

| Private Agency | 90 (63.4% |

| Public Agency | 1(0.7%) |

| University or College | 2 (1.4%) |

| Other: private practices (solo or small group), holistic non-profit agencies, non-profit LGBT community centers, community health centers, non-profit private agencies, and a public clinic at a state university | 48 (33.8%) |

| Type of Care | |

| Private practice – individual | 93 (65.5%) |

| Private practice – group | 7 (4.9% |

| Both | 39 (27.5% |

| Neither | 3 (2.1%) |

| Role (Job Title) | |

| Licensed Clinical Social Worker (LCSW) | 32 (22.5%) |

| Other Licensed Masters-level Mental Health Practitioner (e.g., LMFT) | 61 (43%) |

| Masters-level Intern | 2 (1.4%) |

| Psychiatrist (M.D. or D.O.) | 1 (0.7%) |

| Psychologist – Ph.D. | 15 (10.6%) |

| Psychologist – Psy.D. | 15 (10.6%) |

| Other: licensed clinical mental health counselor (LCMHC), independent marriage and family therapist Ph.D., licensed independent mental health practitioner (LIMHP), licensed independent clinical social worker (LICSW), family counseling Ph.D., family therapy Ph.D., human sexuality Ph.D., registered psychotherapist, and licensed professional counselor | 16 (11.3%) |

| Theoretical Orientation | |

| Cognitive Behavioral Therapy | 38 (26.8%) |

| Dialectical Behavioral Therapy | 4 (2.8%) |

| Eclectic | 24 (16.9%) |

| Psychodynamic | 11 (7.7%) |

| Other: existential-humanistic, emotionally focused therapy (EFT), feminist multicultural, cognitive processing therapy, and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR). | 62 (43.7%) |

| Years of Experience as a Mental Health Provider | |

| Less than 1 year | 3 (2.1%) |

| 1 – 4 years | 15 (10.6%) |

| 5 – 10 years | 44 (31%) |

| 10 – 20 years | 53 (37.3%) |

| 20 – 30 years | 20 (14.1%) |

| More than 30 years | 7 (4.9%) |

There was one missing response for geographic location of practice and three missing responses for theoretical orientation.

Table 2.

TGD-specific training

| Characteristic | Number of Providers (% |

|---|---|

| % of current clients that are TGD | |

| 0% | 8 (5.6%) |

| 1–20% | 65 (45.8%) |

| 21–40% | 24 (16.9%) |

| 41–60% | 16 (11.3%) |

| 61–80% | 16 (11.3%) |

| 81–100% | 13 (9.2%) |

| Number of TGD clients within the past five years | |

| 1–5 | 29 (20.4%) |

| 6–10 | 28 (19.7%) |

| 11–15 | 15 (10.6%) |

| 15–20 | 8 (5.6%) |

| More than 20 | 62 (43.7%) |

| Completed TGD-specific training | |

| Yes | 115 (81%) |

| No | 26 (18.3%) |

| Hours of training received | |

| 1–5 | 13 (9.2%) |

| 6–10 | 29 (20.4%) |

| 11–25 | 18 (12.7%) |

| More than 25 | 53 (37.3%) |

| Number of sources of training | |

| 1–3 sources | 81 (57%) |

| 4–6 sources | 26 (18.3%) |

| More than 7 sources | 4 (2.8%) |

| Sources of Training | |

| Graduate Program | 41 (28.9%) |

| Hospital | 18 (12.7%) |

| Local LGBTQ organizations | 59 (41.5% |

| PFLAG | 17 (12%) |

| Professional Organization | 62 (43.7%) |

| TGD Organizations | 43 (30.3%) |

| WPATH | 35 (24.6%) |

| University | 28 (19.7%) |

| Other*- including area health education centers, online continuing education providers, other LGBTQ clinicians, specific programs (e.g., Psychotherapy Center for Gender and Sexuality NYC, Gender Spectrum, APA, Fenway Health in Boston, Gender Odyssey Seattle), VA online training, and self-learning through books and websites | 20 (14.1%) |

| Willing to provide mental health documentation for clients seeking gender affirming services | |

| Yes – willing and able | 113 (79.6%) |

| Yes – able but unwilling | 3 (2.1%) |

| No – willing but unable | 16 (11.3%) |

| No – unwilling and unable | 5 (3.5%) |

Collective hours therefore some overlap

Note: APA = American Psychological Association; LGBTQ = Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer/questioning; NYC = New York City; PFLAG = Parents and Friends of Lesbians and Gays; VA = Veterans Administration; WPATH = World Professional Association of Transgender Health.

There were 5 cases missing from willing to provide a letter for gender affirmation services; 31 cases from the number of sources providing TGD specific training and one case missing from completed TGD specific training.

Spearman rank-order correlations revealed statistically significant moderate correlations between variables (refer to Table 3). There were statistically significant positive correlations between the current number of TGD clients, the number of TGD clients within the past five years and the number of hours of TGD-specific training on self-reports of comfort, competence, and ability to work with TGD clients.

Table 3.

Correlation Matrix

| Comfort | Competence | Ability to Provide TGD-sensitive care | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of Experience as a mental health provider | .034 | .121 | .035 |

| Percentage of current clients that identify as TGD | 0.455** | .541** | .396** |

| Number of TGD clients in the last five years | .521** | .515** | .279** |

| Number of hours of specific training to work with TGD clients | .375** | .483** | .283** |

| Number of sources of training | .208* | .265** | .133 |

p <.01

p < .05

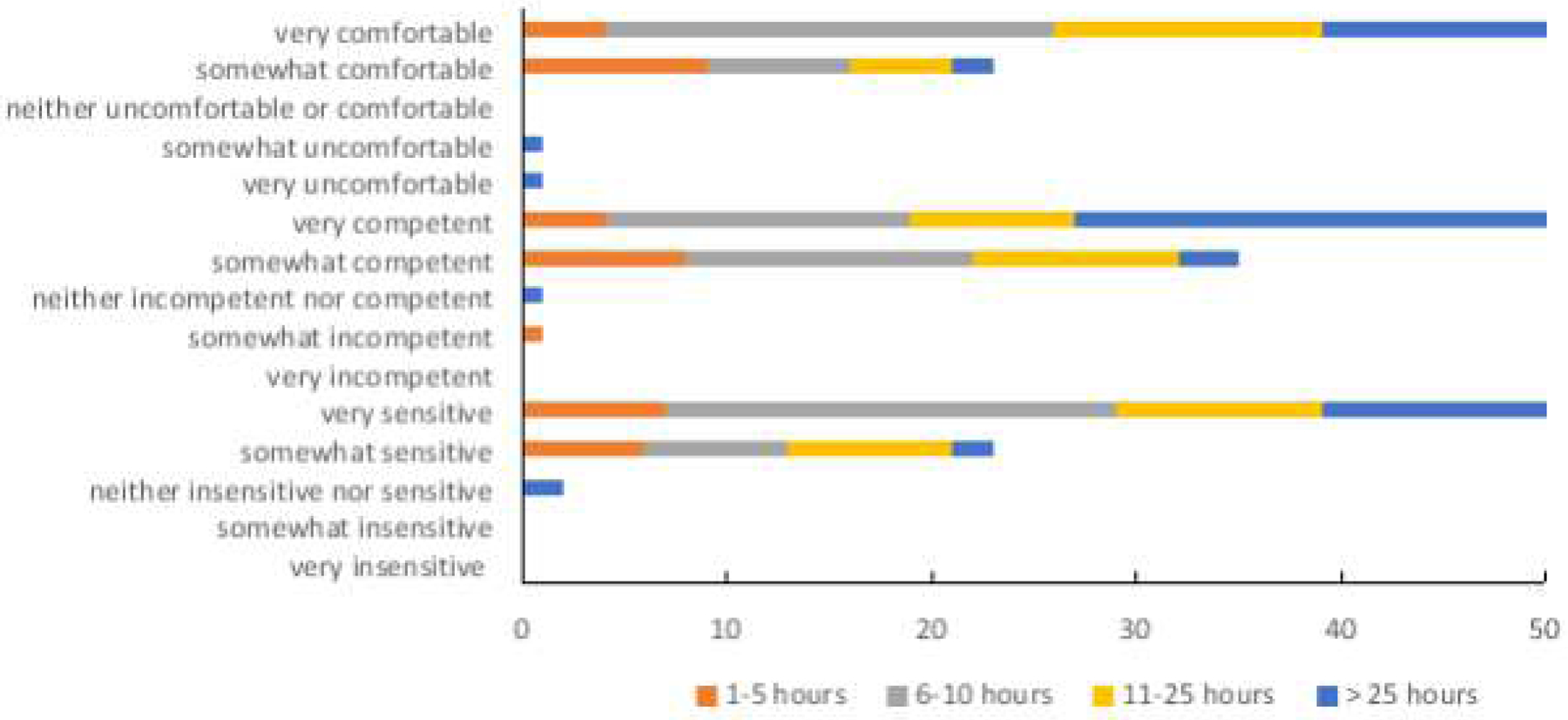

Based on ordinal regression, statistically significant chi square analyses indicate that the final model better predicted the dependent variables over and above the intercept-only model (refer to Table 4). Further analyses revealed that the number of hours of TGD-specific training received had a statistically significant effect on the prediction of self-reported level of competence to work with TGD clients, Wald x2 (3) = 8.901, p = .03 and self-reported level of ability to provide TGD-sensitive care x2 (3) = 7.842,p =.049 (refer to Figure 1).

Table 4.

Ordinal Regression_Model fitting information

| Dependent Variable | Model | −2 Log Likelihood | Chi Square | d.f. | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comfort | Intercept Only | 129.354 | |||

| Final | 69.207 | 60.147 | 19 | 0.000 | |

| Competence | Intercept Only | 149.125 | |||

| Final | 86.668 | 62.457 | 19 | 0.000 | |

| TGD-Sensitive | Intercept Only | 120.226 | |||

| Final | 78.308 | 41.918 | 19 | .002 |

Figure1.

Self-report of mental health professionals' comfort, competence and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care and number of hours of TGD-specific training received.

Discussion

This study documented the types of training mental health professionals received to provide TGD-sensitive care, the sources from which they received the training, as well as the self-reported levels of comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care. Collectively, findings revealed that the majority of the mental health professionals in the study (approximately 81%) received specific training to work with TGD clients from a variety of sources. The mental health professionals in this study also self-reported high levels of comfort, competence, and ability to offer TGD-sensitive care which were associated with the number of hours of TGD-specific training they had received based on ordinal regression analyses.

Four out of five of the mental health professionals reported that they had received training to work with TGD clients, but the source, type and length of that training differed among providers. Training sources included local continuing education opportunities, classes at universities /colleges, conferences, workshops, books, certifications, and self-guided research/learning. Although no information is available on the content or quality of the training, the differences in training sources suggest that variability may be likely. Some sources, such as community organizations including PFLAG or other LGBTQ groups, may be well prepared to provide general information about TGD adults. These sources, however, may be less likely to provide education or supervision for professional clinical skills including appropriate assessment or intervention techniques, ethics, or other aspects of TGD-sensitive professional practice.

Nearly 30% of participants in this study indicated they had received TGD-specific training in their graduate-program; an encouraging sign that such training may be becoming more widely incorporated into mental health educational curricula. At least five participants indicated that working directly with TGD clients was the basis of their training to work with such clients. This approach is more likely if these mental health professionals started practicing before TGD-specific training or Standards of Care were available (e.g., Coleman, 2012). Given that other sources of training are now available, however, "educational burdening" or exclusively relying on TGD clients to educate their therapist is no longer warranted.

Including TGD voices in the training of mental health professionals can help assure that clinicians are prepared to meet the needs of TGD-clients. This recommendation is supported by the observation in this study of associations between percentage of current TGD clients and number of TGD clients in the past five years and self-reported levels of comfort, competence and ability to provide TGD-care although these associations did not reach statistical significance in the regression analyses. There is a role for didactic and experiential learning when training mental health professionals to work with TGD clients. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) can serve as a model for elevating and amplifying community voices (Mocarski et al., 2020). Training to provide care, built with community engagement with TGD persons outside of a clinical setting, better position mental health professionals to be affirming and understanding of TGD issues from the community's perspective. Combining the community voices with the growing empirical literature on mental health and well-being for TGD people will yield culturally sensitive evidence-informed care models.

Although informative, there are limitations with this study which should be considered when developing future investigations of the educational preparedness of mental health professionals to care for TGD clients. First, this study had a comparatively small number of participants (n=142) who all advertised that they work with TGD clients. Of the 249 potential participants contacted only 142 completed the surveys analyzed in the current study; a response rate of 58%.

The fact that these participants already work with TGD clients suggests a predisposed interest in providing this type of care and by extension motivation to be trained to work with TGD clients. Thus, this research sample may be unique in that the respondents who completed the survey may be more experienced and better trained than other mental health professionals. Second, the majority of respondents in this study worked in private practice. It would be beneficial in future studies to assess the educational preparedness of mental health professionals working in public settings who may be more likely to work with un- or under-insured TGD clients who may need more mental health support with fewer access to resources (Puckett et al., 2018; ). Third, the survey did not capture the race ethnicity of ages of the mental health professionals. Any follow-up study should begin with a power analysis to determine a priori the appropriate number of participants, especially from different racial and ethnic communities and age groups (Cohen, 1992). Fourth, the descriptive nature of the results prohibits causation statements and generalizability of the findings. Fifth, the self-report measurements used in this study may have been impacted by social desirability whereby participants do not share their true feelings and respond in socially acceptable ways (Vella-Broderick & White, 1997). The confidentiality and anonymity measures employed in this study, however, should help to reduce the likelihood of completing the survey in a socially desirable way. Finally, no data were available from the perspective of TGD clients on the nature or quality of services received from the mental health professionals in this study although there is documentation from other sources that TGD clients have mixed experiences with providers (e.g., Benson, 2013; Meyer et al., 2020; Mizock & Lundquist, 2016). This study presents positive results, demonstrating that over 4 in 5 providers located via an internet search are both comfortable working with TGD clients and have training to buttress this comfort. These data, however, when juxtaposed with the findings of a previous study which found that only about half of providers had websites that portrayed basic cultural competence for working with TGD clients suggests that there is still more work to be done in educating mental health professionals (Holt et al., 2019; Holt et al., 2020). Due to methodical limitations, the providers in this study cannot be directly matched with those in the website analysis study (Holt et al., 2019; Holt et al., 2020). However, given the well-documented challenges faced by TGD clients in obtaining affirming and sensitive care as noted above, future research is needed to determine whether mental health-providers who self- identify and advertise as a TGD specialist, have the tools necessary to provide the affirming and sensitive care that they wish to provide from the perspective of their clients and, eventually, objectively measured therapeutic outcomes.

Overall, this exploratory project documents the self-reported levels of comfort, competence, and ability to provide TGD-sensitive care of mental health professionals who work with TGD clients and offers insight into the sources and types of training of these mental health professionals. This project may serve as the basis for a more expansive investigation which may be conducted via a mixed-methods approach consisting of a comprehensive survey and semi-structured interviews with mental health professionals who care for TGD clients. The disparities in types of training, sources of training and the length of training to provide TGD-specific care, identified in the current study, reinforce the importance of such an investigation. Examining the educational preparedness of mental health professionals and ensuring that mental health professionals are appropriately educated to provide TGD-sensitive care are mechanisms that may be utilized to support health equity for TGD adults.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ruby Bell for her assistance with data collection.

Funding Information:

This work was supported by National Institutes of Mental Health Grant No. R21 MH108897–01A1 and a University of Nebraska Systems Science Team Building Award to the 5th author.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

IRB Approval

This study was reviewed and approved by the University of Nebraska at Kearney IRB (Protocol Number: 030718)

Contributor Information

Sharon N. Obasi, Department of Counseling, School Psychology and Family Science, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, Nebraska, USA.

Robyn King Myers, Department of Counseling, School Psychology and Family Science, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, Nebraska, USA.

Natalie Holt, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

Richard Mocarski, Office of Sponsored Programs, University of Nebraska at Kearney, Kearney, Nebraska, USA

Debra A. Hope, Department of Psychology, University of Nebraska – Lincoln, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA

Nathan Woodruff, Trans Collaborations Local Community Board, Lincoln, Nebraska, USA.

References

- Abeln B & Love R (2019). Bridging the gap of mental health inequalities in the transgender population: The role of nursing education. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(6), 482–485. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2019.1565876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Counseling Association (2010). Competencies for Counseling with Transgender Clients. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 4 (3), 135–159. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2010.524839. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2015). Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender diverse people. American Psychologist, 70(9), 832–864. doi: 10.1037/a0039906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer G, Scheim A, Pyne J, Travers R, & Hammond R (2015). Intervenable factors associated with suicide risk in transgender persons: A respondent driven sampling study in Ontario, Canada. BMC Public Health, 15, 525–540. doi: 10.1186/s12889-015-1867-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benson KE (2013). Seeking support: Transgender client experiences with mental health services. Journal of Feminist Family Therapy, 25, 17–40. doi: 10.1080/08952833.2013.755081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bockting WO, Miner MH, Swinburne Romine RE, Hamilton A, & Coleman E (2013). Stigma, mental health, and resilience in an online sample of the US transgender population. American Journal of Public Health, 103(5), 943–951. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouman WP, Claes L, Brewin N, Crawford JR, Millet N, Fernandez-Aranda F, & Arcelus J (2016). Transgender and anxiety: A comparative study between transgender people and the general population. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 16–26. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1258352 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carabez R, Pellegrini M, Mankovitz A, Eliason M, Ciano M, & Scott M (2015). “Never in all my years.”: Nurses’ education about LGBT health. Journal of Professional Nursing, 31(4), 323–329. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2015.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan B, Skocylas R, Safer JD (2016) Gaps in transgender medicine content identified among Canadian medical school curricula. Transgender Health, 1(1), 142–50. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2016.0010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1992). A power primer. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 155–159. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J & Zucker K (2012). Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-nonconforming people, version 7. International Journal of Transgenderism, 13(4), 165–232. doi 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson AE, Wymbs BT, Gidycz CA, Pride M & Figueroa W (2017). Exploring rates of transgender individuals and mental health concerns in an online sample. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(3), 295–304. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2017.1314797 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deutsch MB (2016). Evaluation of patient-oriented, internet-based information on gender-affirming hormone treatments. LGBT Health, 3, 200–207. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries KM (2012). Intersectional identities and conceptions of the self: The experience of transgender people. Symbolic Interaction, 35(1), 49–67. doi: 10.1002/SYMB.2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dy GW, Osbun NC, Morrison SD, Grant DW, Merguerian PA (2016). Transgender education study group. Exposure to and attitudes regarding transgender education among urology residents. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 13(10),1466–72. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.07.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goins ES, & Pye D (2013). Check the box that best describes you: Reflexively managing theory and praxis in LGBTQ health communication research. Health Communication, 28, 397–407. doi: 10.1080/10410236.2012.690505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt NR, Hope DA, Mocarski R & Woodruff N (2019). First impressions online: The inclusion of transgender and gender nonconforming identities and services in mental healthcare providers’ online materials in the USA. International Journal of Transgenderism, 20(1), 49–62. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2018.1428842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt NR, King RE, Mocarski R, Woodruff N & Hope DA (2021). Specialists in name or practice? The inclusion of transgender and gender diverse identities in online materials of gender specialists. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(1), 1–15, doi: 10.1080/10538720.2020.1763225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irwig MS (2016). Transgender care by endocrinologists in the United States. Endocrine Practice 22(7), 832–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- James SE, Herman JL, Rankin S, Keisling M, Mottet L & Anafi M (2016). The Report of the 2015 U.S. Transgender Survey Washington, DC, National Center for Transgender Equality. [Google Scholar]

- Johnston CD & Shearer LS (2017). Internal medicine resident attitudes, prior education, comfort, and knowledge regarding delivering comprehensive primary care to transgender patients. Transgender Health, 2(1), 91–95. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.0007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korpaisarn S & Safer JD (2018). Gaps in transgender medical education among healthcare providers: A major barrier to care for transgender persons. Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, 19, 271–275. doi: 10.1007/s11154-018-9452-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laerd Statistics (2018). Statistical tutorials and software guides Retrieved from https://statistics.laerd.com

- Meyer HM, Mocarski R, Holt NR, Hope DA, King RE & Woodruff N (2020). Unmet expectations in health care settings: experiences of transgender and gender diverse adults in the Central Great Plains. Qualitative Health Research, 30(3), 409–422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millet N, Longworth J, & Arcelus J (2016). Prevalence of anxiety symptoms and disorders in the transgender population: A systematic review of the literature. International Journal of Transgenderism, 18(1), 27–38. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2016.1258353 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizock L & Lundquist C (2016). Missteps in psychotherapy with transgender clients: Promoting gender sensitivity in counseling and psychological practice. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 3(2), 148–155. doi 10.1037/sgd0000177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mocarski RA, Eyer JC, Hope DA, Meyer HM, Holt NR, Butler S & Woodruff N (2020). Keeping the promise of community-based participatory research: Integrating applied critical rhetorical methods to amplify the community’s voice for trial development. Journal of Community Engagement and Scholarship, 13(1), 26–35. [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SD, Chong HJ, Dy GW, Grant DW, Wilson SC, Brower JP, et al. (2016) Educational exposure to transgender patient care in plastic surgery training. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, 138(4), 944–53. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000002559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrison SD, Dy GW, Chong HJ, Holt SK, Vedder NB, Sorensen MD, et al. (2017). Transgender-related education in plastic surgery and urology residency programs. Journal of Graduate Medical Education 9(2),178–83. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-16-00417.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paradiso C & Lally RM (2018). Nurse Practitioner Knowledge, Attitudes, and Beliefs When Caring for Transgender People. Transgender Health, 3(1), 47–56. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2017.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Psychiatry.org. 2021. TGNC Guide [online] Available at: https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/cultural-competency/education/transgender-and-gender-nonconforming-patients/best-practices [Accessed 14 November 2021].

- Puckett JA., Cleary P., Rossman K., Newcomb ME, & Mustanski B. (2018). Barriers to gender-affirming care for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 15(1), 48 59. doi: 10.1007/s13178-017-0295-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DW & Bartholomaeus C (2016) Australian mental health professionals’ competencies for working with trans clients: a comparative study, Psychology & Sexuality, 7:3, 225–238, DOI: 10.1080/19419899.2016.1189452 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford K, McIntyre J, Daley A, Ross LE (2012) Development of expertise in mental health service provision for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender communities. Medical Education, 46(9), 903–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04272.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shipherd JC, Green KE, & Abramovitz S (2010). Transgender clients: Identifying and minimizing barriers to mental health treatment. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 14(2), 94–108. doi: 10.1080/19359701003622875 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Strousma D (2014). The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. American Journal of Public Health, 104(3), e31–e38. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker SD, Pallerla H, Yockey RA, Bedard-Thomas J, Pickle S (2021). Training mental health professionals in gender-affirming care: a survey of experienced clinicians. Transgender Health X:X, 1–10. doi: 10.1089/trgh.2020.0123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Unger CA (2015). Care of the transgender patient: a survey of gynaecologists’ current knowledge and practice. Journal of Women's Health, 24(2),114–8. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2014.4918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vella-Brodrick DA, & White V (1997). Response set of social desirability in relation to the Mental, Physical and Spiritual Well-Being Scale. Psychological Reports, 81, 127–130. doi: 10.2466/PR0.81.5.127-130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White ME, Cartwright AD, Reyes AG, Morris H, Lindo NA, Singh AA & McKinzie Bennett C (2020) “A Whole Other Layer of Complexity”: Black Transgender Men’s Experiences, Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 14(3), 248–267. doi: 10.1080/15538605.2020.1790468 [DOI] [Google Scholar]