Abstract

Background and Objectives

Globally, older adults are undergoing spine surgery for degenerative spine disease at exponential rates. However, little is known about their experiences of living with and having surgery for this debilitating condition. This study investigated older adults’ understanding and experiences of living with and having surgery for degenerative spine disease.

Research Design and Methods

Qualitative methods, grounded theory, guided the study. Fourteen older adults (≥65 years) were recruited for in-depth interviews at 2 time-points: T1 during hospitalization and T2, 1–3-months postdischarge. A total of 28 interviews were conducted. Consistent with grounded theory, purposive, and theoretical sampling were used. Data analysis included open, axial, and selective coding.

Results

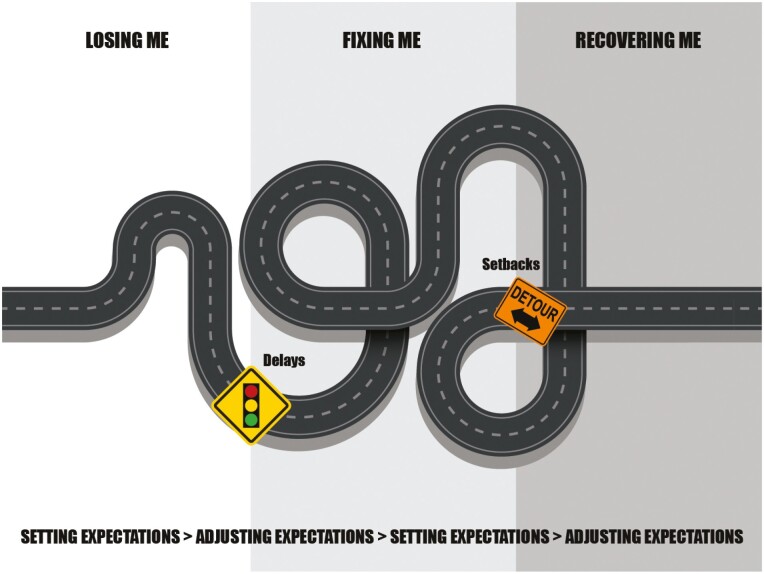

A conceptual model was developed illustrating the process older adults with degenerative spine disease experience, trying to get their life back. Three key categories were identified (1) Losing Me, (2) Fixing Me, and (3) Recovering Me. Losing Me was described as a prolonged process of losing functional independence and the ability to socialize. Fixing Me consisted of preparing for surgery and recovery. Recovering Me involved monitoring progression and reclaiming their personhood. Conditions, including setbacks and delays, slowed their trajectory. Throughout, participants continually adjusted expectations.

Discussion and Implications

The conceptual model, based on real patient experiences, details how older adults living with and having surgery for degenerative spine disease engage in recovering who they were prior to the onset of symptoms. Our findings provide a framework for understanding a complex, protracted trajectory that involves transitions from health to illness working toward health again.

Keywords: Care transitions, Health to illness, Patient experience, Postoperative recovery, Qualitative methodology

Degenerative spine disease (DSD) commonly occurs as individuals age. In the United States, the incidence of lumbar DSD in Medicare beneficiaries is 31.5% (Buser et al., 2018). Over time, a cascade of age-related degenerative changes results in the narrowing of the spinal canal and neural foramen. Symptoms include low back, buttock, and leg pain exacerbated by walking; a shortened walking distance; forward flexed posture; and numbness in the legs/feet. Older adults with DSD often experience debilitating pain, impaired function, falls, loss of independence, and exacerbation of aging syndromes (Buehring & Barczi, 2019; Ferreira & de Luca, 2017).

The incidence of elective spine surgery to provide symptom relief has dramatically increased worldwide. American Medicare beneficiaries experienced a 26% increase in the number of spinal fusion surgeries between 2012 and 2017 (Lopez et al., 2020). In Norway the rate of lumbar spine surgeries for persons aged 75 years and older increased 400% from 1999 to 2013 (Grotle et al., 2019). Furthermore, the rate of spinal fusion surgeries for Finnish women over the age of 75 increased by 422% from 1999 to 2018 (Ponkilainen et al., 2021). Older adults anticipate that after spine surgery, they will experience an improvement in functional status, pain relief, and sensation (Yachnin et al., 2021). Indeed, the clinical outcomes (pain and disability) of people 80 years and older who underwent lumbar spine surgery for DSD improved (Liang et al., 2020). Additionally, recent systematic reviews also found clinical improvement for people who had surgery for DSD. However, previous study populations have often been younger, or participant age was not reported (Koenders et al., 2019; Oster et al., 2020).

Unfortunately, medical complications frequently occur in older adults after undergoing spine surgery. A recent scoping review conducted by Strayer et al. (2022) identified older adults who undergo elective spine surgery for DSD as being at risk of developing one or more of 18 in-hospital postoperative medical complications. The most frequently investigated complications were delirium, urinary tract infection, gastrointestinal problems, pulmonary embolus, and deep vein thrombosis. However, the authors noted a significant void in the literature on how older adults think about and define what a complication is or how complications affect their trajectory of recovering a normal life.

Older adults also risk having a complication when transitioning from hospital to home (Fønss Rasmussen et al., 2021). Older adults admitted to medical units noted they receive information that is not a good “fit” for their use, do not feel prepared to engage in their own self-care, and must rely on others to help recover postdischarge (Liebzeit et al., 2020; Werner et al., 2019). Furthermore, studies of older adult transitions from hospital to home have primarily focused on care coordination, evaluating outcomes such as readmissions, medication management, self-management, and quality of life (Hladkowicz et al., 2022; Liebzeit et al., 2021). Few studies have been conducted on how older adults who undergo spine surgery think about transitioning from hospital to home, how they prepare for the surgical experience, or how they conceptualize a transition from disability to recovering their normal life (Accardi-Ravid et al., 2020; Damsgaard et al., 2017; van der Horst et al., 2019; Rushton et al., 2020). Therefore, this study was designed to address these gaps by investigating older adults’ understanding and experiences living with and having spine surgery for DSD.

Method

Study Design

This qualitative study utilized grounded theory (GT), to explore a phenomenon in which little knowledge is available. GT is based on symbolic interactionism and was developed to study social processes (Bowers, 1988; Glaser & Strauss, 1967). GT, derived from the data, enhances understandings and perceptions of the human experience and actions people take in response to their understandings (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Researchers investigate actions with GT, as well as social processes such as responding to and coping with life changes (Thornberg & Charmaz, 2014). Because results are grounded in the older person’s perspective, they provide empiric evidence needed to develop patient-centered interventions (Glaser & Strauss, 1967). This study was approved by the University of Wisconsin–Madison Health Sciences Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Participants and Setting

Inclusion criteria consisted of aged 65 years and older, diagnosed with DSD, admitted for elective spine surgery by a neurosurgeon, and able to speak and understand English. Exclusion criteria consisted of the inability to share experiences or having spine surgery for cancer, trauma, or infection. Participants were recruited from a large Midwestern hospital during their hospitalization, prior to discharge. Potential participants were approached by a hospital nurse to avoid any perceived coercion, given a study information sheet, and asked if they would like to speak to the researcher about the study. If so, the nurse contacted the first author, who then met with the patient, provided information, answered questions, obtained verbal consent, and arranged a time for the first interview (T1).

Sampling

Consistent with GT, purposive and theoretical (a hallmark of GT) sampling was utilized to understand events and occurrences experienced by participants. Purposive sampling was initially used to capture individuals experiences and perceptions (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The research team collaborated to create preliminary categories and then shifted to theoretical sampling to further understand if emerging concepts were significant based on repeatedly being either present or absent when comparing incidents to each other. Theoretical sampling can occur in several ways: sampling different participants or at different times within their trajectory, focusing interview questions to densify categories and identify dimensions within categories, or once theoretically sensitized, returning to the data to see if concepts were present that were not recognized earlier (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). For example, during analysis of data collected from participants who were one-month postdischarge, none described being where they wanted to be in their recovery. Therefore, the research team collaboratively decided to sample participants at two to three months postdischarge, to understand if time affected participants perceptions of their recovery process or if any reached their goal of where they want to be after surgery.

Data Collection and Analysis

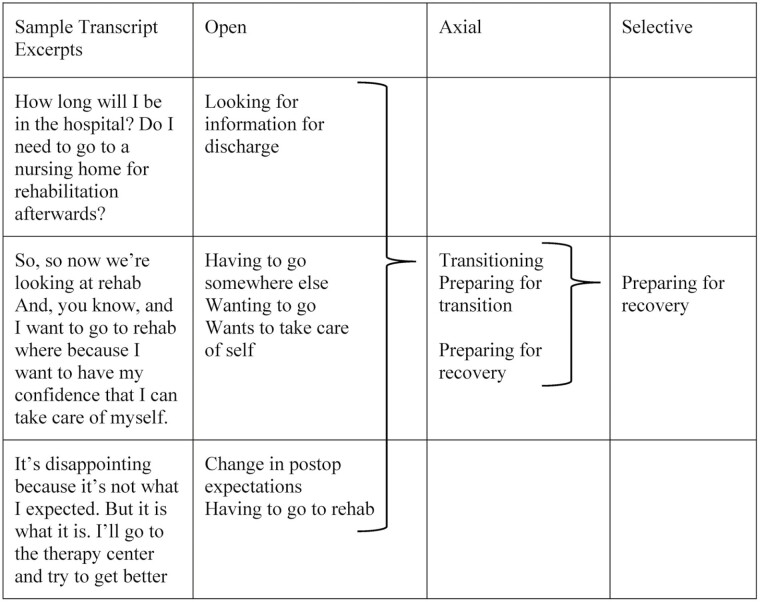

Sixteen eligible participants were approached during recruitment, two declined, leaving 14 participants enrolled (see Supplementary Table 1 in Online Supplementary Material). Consistent with GT, sampling and analysis were iterative consisting of sampling, data analysis, and further sampling based on findings emerging from the data. Data collection consisted of in-depth 1:1 interviews at two time-points (T1 and T2). T1 interviews were conducted postsurgery in the participant’s private hospital room. T2 interviews occurred either in the participant’s home or a mutually agreed upon private location (n = 10) or via a virtual platform (n = 4) due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) concerns, at 1–3 months postdischarge. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim; field notes were taken to note pauses in participant responses or change in vocal tone and expression. Initial interviews were nondirectional and open, allowing for participant experiences to guide the interview (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). An example of an initial open question was, “Tell me about what it has been like for you to have spine problems and spine surgery.” As preliminary categories were formed, follow-up questions became more focused to identify dimensions within each category and conditions which influenced interactions among categories. For example, “Please tell me about how you prepared for surgery” (Supplementary Material 2). All 14 participants completed two interviews (T1 and T2) between December 2020 and September 2021. At T2, 10 participants were interviewed at one month, two at two months, and two at three months. A total of 28 interviews were completed. T1 interviews ranged from 12 to 50 (mean = 30.6) minutes, and T2 interviews ranged from 19 to 65 (mean = 40.2) minutes. Participants consisted of eight females and six males with an age range from 65 to 84 years (mean 73.9 years). Sampling continued until data saturation was reached, a point when no new information or categories emerged from the data (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). A four-member interdisciplinary qualitative research team completed the data analysis. All team members participated in 16 virtual and face-to-face data analysis sessions. Consistent with GT, data were analyzed using open, axial, and selective coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Open coding consisted of a line-by-line approach to examine what participants understood about the phenomenon and to develop preliminary categories. Using axial coding generated key concepts and identified dimensions within each category and existing conditions. Selective coding integrated the categories and helped develop a conceptual model that illustrated how participants engaged in living with and having elective spine surgery for DSD. Constant comparative analysis compared new data with existing data to further develop codes and categories, identify gaps, and add densification (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The research team used white board diagramming to visually enhance the data analysis sessions. Figure 1 provides an example of the coding schema used in our study.

Figure 1.

A coding example from data analysis.

Trustworthiness

Strategies employed to assure trustworthiness included peer debriefing (credibility) via an interdisciplinary team to code and develop categories and the conceptual model (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). If disagreement occurred with codes, the team returned to the data and discussed their interpretation until a consensus was reached. Member checking (credibility) was used by sharing the developing conceptual model with participants at the end of the interview, asking them to share their understanding of the model and if it represented their experience (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Memo-writing (confirmability) recorded researcher ideas, identified further properties of the categories as well as conditions and consequences discovered (Lincoln & Guba, 1985; Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Table 1 details further steps taken to ensure quality by following the five tenets of trustworthiness as classically outlined by Lincoln and Guba (1985).

Table 1.

Tenets of Trustworthiness

| Tenet of trustworthiness | Qualitative methodology example | Strategies in this study |

|---|---|---|

| Credibility (internal validity) | Use of standard grounded theory procedure Scrutiny Confidence in the truth of the study |

Grounded theory methodology justified Prolonged engagement Reflexivity Use of analytic tools to help prevent bias from influencing study Member checking employed |

| Dependability (reliability) | Assessment of the quality of the: -data collection -data analysis -conceptual model/theory generation |

Weekly team data analysis meetings Strict grounded theory methodology in an apprentice model with grounded theorist Audit trail employed Certified outsourced transcriptionist |

| Confirmability (objectivity) | Findings supported by the data Analysis is representative |

Reflexivity Memo-writing employed Participant quotes support findings Member checking employed |

| Authenticity | Range of realities evident Realistically conveys participants’ reality |

Participants with a range of experiences Rich, detailed descriptions |

| Transferability (generalizability) | Applicable to other settings Readers can associate the results with their own experiences |

Dense descriptions of study context and assumptions Transparency |

Notes: Trustworthiness refers to the degree of confidence in the data interpretation and methods used to ensure the quality of the study. This is equivalent to rigor in quantitative methods. This table provides the five tenets of trustworthiness as classically developed by Lincoln and Guba (1985), with the analogous quantitative rigor assurance in parentheses following the tenet of trustworthiness.

Results

The qualitative interview data yielded a conceptual model (Figure 2) that illustrates older adults’ understanding and experiences living with and undergoing spine surgery for DSD. Participants described in detail the process of recovering. At an abstract level, recovery was about moving through phases that we labeled as Losing Me, Fixing Me, and Recovering Me. The process of recovery occurred over months to years (starting in Losing Me and moved to Recovering Me). Recovery was also described at a micro level and included common postoperative tasks, such as following physician or physical therapy orders or monitoring for improvements in the decline present prior to surgery. This type of recovery occurred in the Fixing Me and Recovering Me phases after they had their surgical procedure. In addition, two primary conditions, Being Delayed and Having Setbacks were identified. Conditions often prolonged participants time in a phase, not allowing them to progress, influenced when participants were able to get their surgery, and influenced their recovery process. Consequences, the results conditions have on the interactions among the categories, was the constant Setting and Adjusting of Expectations. Finally, hope seemed to function as an internal motivator for participants throughout the process, helping them push forward when limited progress was occurring. Table 2 contains additional quotes to support the results.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model.

Notes: The conceptual model is an integration of all that was being experienced by participants who had undergone surgery for degenerative spine disease. The three shaded backgrounds colors represent the three categories, Losing Me, Fixing Me, and Recovering Me. The road represents the journey participants engage in as they moved through the phases. The two primary conditions, Being Delayed and Having Setbacks influenced participants time in a category, usually prolonging the time in that phase, not allowing them to progress. The type of condition influenced the degree and number of challenges (curves) the participant incurred. The setbacks or delays in progress resulted in participants having to continually Set or Adjust Expectations for their recovery.

Table 2.

Additional Participant Quotes to Support Data Analysis

| Category | Dimension | Supporting quote |

|---|---|---|

| Losing Me | Putting life on hold | “I knew something was wrong. I knew that I was decompensating. I knew it back a year ago … I felt in me, I was decompensating … you need to get a scan … a spinal scan … that took time … and then seeing a surgeon took time. And then, and then scheduling the surgery took time.” (P3T1) |

| “I really have not been able to exercise and I am someone … I was at the gym three to four days a week … over this last year I have been unable to do diddlysquat … for me that was frustrating because I just could not do it.” (P1T2) | ||

| Proving I need help | “I started going to pain clinics. I went to one pain clinic until what they were doing wasn’t working, then I’d go to another pain clinic. I went from clinic to clinic … One appointment after another cancelled. And then sent me over to a doctor that said, I think I can help you.” (P10T1) | |

| “I did physical therapy for 2 years to try to avoid it. I had a fabulous physical therapist, but it just didn’t work.” (P4T1) | ||

| I won’t be that person | “I feel sorry for a lot of people. I see so many senior citizens. They’re walking with canes. They’re walking with the carriers. I don’t think you have to live that way.” (P5T1) | |

| Fixing Me | Preparing for surgery | “I have one friend that’s saying, ‘I’ll come over and cook for you’. What I really need is a chauffeur. My freezer is stocked with frozen meals and chicken and stuff that I can just pull out and thaw and fry in a frying pan.” (P6T1) |

| Preparing for recovery | “Well, everybody’s telling me rehab is hell on wheels, but [laughing], I don’t know, you’ve gotta approach it on the basis that you’ve got to do it if you want some mobility and dexterity.” (P12T1) | |

| Doing what they tell me | “I just follow the doctors’ and the nurses’ orders. Do exactly what they say.” (P2T1) | |

| “The only thing, you know, once my feet hit the floor, on that bed there’s an alarm system. Right when the nurses come in, they’d say (proper name)! You know that you’re supposed to have nurses to help you get out of bed.” (P5T2) | ||

| “At exactly, boom, day 14, I said, ‘I’m done with narcotics. I’m just going to do the muscle relaxant and acetaminophen’. And that was much better because I didn’t like the fogginess either.” (P6T2) | ||

| Recovering Me | Monitoring | “Well, I’ll say I’m in the process of recovering me … Yeah, by moving my leg, it’s more functional. And I can sit up and do minor things for myself instead of depending on everything.” (P13T2) |

| “I’m still able to do things that I was able to do before, but it’s still weak and I—I still can’t raise that foot as much as I want to …. over the next few months or a year, or whatever, it’ll gradually improve.” (P7T2) | ||

| “I talked to my doctor. I thought I was done with rehab, no one told me how long I was going to stay. I guess I should have stayed longer. I wasn’t doing real good, so he told me I was doing too much. I was overexerting myself. Now I am at a family members home.” (P8T2) | ||

| Progressing | “That rehab I went to was a waste. I mean, all I did, basically, was did my own walking. Rehab-wise it was not really nothing.” (P11T2) | |

| “I figure it will probably be next Spring anyway. The doctor said it would be a year. So, I’m not, not going to push it, because I’m old.” (P9T2) | ||

| Reclaiming | “I’m just hoping that this is going to work and that I will be able to live a normal life the few years that I’ve got left. So, I’m just hoping that this surgery works. I’m just hoping that everything is going to work out good, that’s all.” (P14T2) | |

| “I am getting ready for this art show. I am an artist, and I [want to be at this show].” (P10T2) | ||

| “What brings me joy is being with … I wanted to get back out playing golf. I knew it wouldn’t come in the Spring, but I’d hope the very late Spring … by playing golf means I’m back, [participant] is back. Literally back. That he’s back. So, so, and I’m not sure that’s going to happen … it’s not that I value that over being able to be with family and friends. But it is, it’s a marker, so to speak that I’m back.” (P3T1) | ||

| Conditions | Being Delayed | “That was the bad part, I had to wait almost 5 weeks before I could get in here. I don’t think that helped any either. Because the longer you wait for something, the worse it gets. The doctor was backed up, I wanted surgery the next day.” (P7T1) |

| Having Setbacks | “The spaciness was a strange feeling … disconcerting … what’s happening … am I getting out of touch … that I don’t know what’s going on … I can’t manage here.” (P1T1) | |

| “I got the infection at home [after surgery]. They took care of it right away. I need somebody assigned to me for more physical therapy. If you need to bring a piece of equipment in here, bring it in. These hospital rooms are small, but I need my legs back.” (P12T2) | ||

| Consequences | “I think if I’d been told during my preop visit of what to anticipate … or someone to discuss with me about how my condition had changed and what that would mean for me and how to prepare … I felt like I didn’t have a choice but to stay in rehab, that if I went home—and I really seriously thought about, ‘I just can’t do this anymore. I can’t do another day in the hospital’. … If you discharge yourself, you’ll not be able to go to the rehab hospital later. So, it was the only choice to stick it out another day and wait to see what insurance says … insurance will allow for home health assistance … so if rehab doesn’t work out, I will develop my own program at home, and I can do that.” (P3T2) |

Notes: P = participant; T1 = time one; T2 = time two.

Losing Me

Losing Me was described as a slow steady loss in participants ability to do physical tasks (walking, lawn care), participate in social activities (going out to eat, shopping), and for some, losing their role in the family (needing help). For many participants, their DSD resulted in progressive weakness and significant pain, forcing them to give up many activities, and for some caused anxiety about being able to walk to and from locations. For most participants, Losing Me started months to years prior to seeking a surgical intervention. Losing Me consists of three dimensions: Putting life on hold, Proving I need help, and I won’t be that person.

Putting life on hold was described as a state of limbo—participants were not the person they used to be (active, reliable) and were waiting to either prove they needed surgery or waiting to get a surgery date. Some participants used the word “stuck” when describing what their life was like. For some, stuck meant they were limited to a space such as within their home. Often, they were dependent on others for transportation or meeting basic needs such as getting groceries or meals. All described longing for when they would be independent again, resume social activities, be more engaged, and for many, finally being freed from unrelenting pain.

You’re stuck in bed. It’s a horrible feeling … it’s like you’re housebound or just stuck in nowhere-land … you get left out of a lot of stuff. (P8T1)

Proving I need help was described as demonstrating to themselves, family, insurance companies, and medical providers that they had exhausted all alternatives for managing their symptoms. Some participants described a sense of desperation, a point where they had reached the end of a rope. This was often due to unrelenting pain and progressive loss in their ability to care for themselves or experiencing falls. Many described feeling frustrated that they had to “jump through hoops” and prove that they were failing more conservative treatments.

And the doctor said to me, ‘before I could get insurance to pay for any of this, you’re going to have to go through rehab’. And I went to rehab for four weeks. Finally, the physical therapist said, ‘It’s not doing any good’. (P5T1)

Complex treatment plans that included multiple visits with different health care providers, medications and injections, and repeated diagnostics were often required by insurance companies and sometimes by surgeons. Participants were confused about what to do next and anxious that they would continue to lose function, thus lessening their chance to regain the life they had. One participant described how they were repeatedly turned away by various clinics. A few participants who waited to seek out care or have surgery regretted their decision as delaying surgery resulted in slower recovery.

I won’t be that person was described as not wanting to be “that person.” That person was someone who was disabled (needing a walker or wheelchair) or dependent on others. They based this on their own reactions to seeing others who required help. Pursuing spine surgery was a means to prevent being or looking disabled to others.

I was walking with a cane and a walker. I don’t know how people can do that the rest of their life. I definitely did not want that to happen. (P11T1)

Fixing Me

Fixing Me consists of three dimensions: preparing for surgery, preparing for recovery, and doing what they tell me. In the Fixing Me phase participants were both active and passive in preparing for surgery and recovery. Participants described being active as they prepared for surgery feeling in control and making decisions but shifted to being passive when preparing for recovery while in the hospital. During hospitalization, participants had little control of what, when, and how decisions were made about whether they could go home or to another care facility. Many participants were surprised about experiences and delays that slowed their recovery. These experiences and delays were different from what they had encountered in the past with prior surgeries (e.g., hysterectomy, transplant, and prior spine surgery).

Preparing for surgery was described in a variety of ways. For some, preparing involved arranging for help, such as someone to help them complete basic activities of daily living. For others, preparing involved arranging home maintenance (cleaning, yard work), transportation, pet care, or having someone “on call” in case they needed immediate help. For others, planning was done by engaging in the meal preparation and freezing dinners.

Some participants prepared for surgery by maintaining their strength, feeling this was essential for a quick recovery. For those that had already worked with a physical therapist (PT), they continued to follow prescribed exercises. Others who had not seen a PT set up their own program by getting outside to walk daily, repeatedly climbing stairs, or completing a range of motion exercises on weight-bearing joints. Several participants expressed concern about getting sick (COVID-19), as this would further delay their surgery.

I kept doing exercises and stretches … to keep my muscles in my legs and ankle as strong as possible. (P7T1)

Although some participants knew what to prepare for based on their own or others prior experience, there were others who had no prior experience with surgeries to guide preparation. These participants felt unprepared. This was particularly the case for those who had to wear a lumbar back brace after surgery. These individuals stated they were not informed as to what to expect. Many described the brace as bulky, painful to wear, restricting, and unable to fit with current clothing. In addition, they did not know how to care for the brace and had to learn while in the hospital, thus adding additional stress onto participants.

And there’s a lot of things they didn’t tell me that were going to happen … I didn’t know I was going to have this brace. This is the big problem, right now, is getting this brace off and on. (P14T1)

Preparing for recovery was described by most as an elusive, moving target that they had no control over nor completely understood. Nearly all participants were evaluated by PT while in the hospital. Participants described their PT as the most influential person for helping them navigate when they would go home, or the person who decided if they needed to transition to a rehabilitation facility. All participants were aware of the importance and power of PT in guiding their recovery both during the hospital stay and after discharge.

And then there was physical therapists, … Well, it was made clear to me that I wasn’t ready to go home … I went to subacute rehabilitation … to get my exercises there. (P5T2)

Many participants had to transition to either acute or subacute rehabilitation after surgery. This was often disappointing, confusing, and distressing because they wanted to go home and did not know when, where, or what care facility they would be transferred to. Others described transitioning to rehabilitation as a relief because they did not feel strong enough to go home or were concerned that their helpers (spouse and family members) would not be able to assist them once they got home.

And so, two nights at most turned out to be eight days. Confusion about would I be accepted into rehab. That was quite distressing. My insurance denying it … I can’t say I prepared. It felt more like I was in a state of uncertainty. (P3T2)

Doing what they tell me was described in terms of being passive in the fixing me phase often waiting to be told by health care providers (physicians, nurses, and PT) what to do. All viewed their health care providers with high regard and felt dependent on them for recovering and getting back to normal. However, many described they were often not provided with information as to what to expect after surgery, leaving them dependent on others for information and guidance, how to advance their recovery, or how to advocate for themselves. They were often confused about what they could do once they returned home.

I wish that they had been a little more instructive about, you know, they say you can’t bend, you can’t do this, you can’t do that. Well, but tell me what can I do? (P6T2)

Recovering Me

The Recovering Me phase was described as an ongoing period of looking for any signs of improvement. The sense of hope seemed predominant and was related to getting back to where they were (strength, mobility, and socially engaged) before the onset of symptoms, no matter how long it took. Because of this, participants accepted that Recovering Me could take a year or more. In this study, no participants stated they had fully recovered their normal functional/health state prior to the presentation of their symptoms. Only one participant indicated they were “close enough,” even though they were not back to the life they hoped for. How participants progressed during Recovering Me was dependent on guidance from surgeons and PTs as to what they could or could not do physically. Family and friends were influential in providing encouragement that kept participants on track with their recovery. Recovering Me consists of three dimensions, monitoring, progressing, and reclaiming.

Monitoring was described as looking for signs that their surgery was successful or for the occurrence of any new problem. For many, this was related to the resolution of the pain they experienced prior to surgery. Others monitored how strong they felt and looked for small indicators of improvement.

At the same time, participants monitored for the return of symptoms that were present prior to surgery. A return of symptoms was an indication that they were “pushing” their bodies and that they needed to slow down. For some, surgeons or family members noticed a decrease in the improvement and insisted participants decrease their activity level or get additional help. For many, monitoring was a constant state of worry and concern as they did not want to undo their progress.

I couldn’t sleep … I was in pain all night long. This leg was aching … Yeah, I’ve probably been doing more than I should be. (P10T2)

Others who helped participants monitor after discharge were PTs. PTs played a key role in informing participants what to monitor for and had the authority to advance the participants activity level. However, not all participants were followed by PT after discharge. Those individuals had to guide themselves. Not knowing what their limit was for the physical activity made them cautious to resume activities.

The PT comes twice a week … I’m learning how to walk all over again. My big success today, which I didn’t even expect, was I went up the stairs. That was huge. I’m anticipating soon being able to go up to my bed and to my shower. (P4T2)

Progressing was described as utilizing benchmarks as a mechanism to determine how well they were progressing both during their hospital stay and after discharge. Important benchmarks during hospitalization were described as small incremental accomplishments such as moving to a chair or walking with a gait belt and walker, etc. Uniformly, the participants’ goal was to get out of the hospital and go home as soon as possible.

Physical therapy came in today. We got on the walker and walked down the hall. I think I made it to the first line (at the nurses’ station). (P9T1)

All participants described an expectation for ongoing, long-term progression. Participants justified this protracted recovery in a variety of ways, including being an older person, having had prior spine surgery, having experienced setbacks after surgery, or simply that recovery takes a long time. Participants continued to benchmark progress with measures of distance walked, what activities they could now do, or returning to work.

Reclaiming was described as engaging in fulfilling activities such as resuming life roles, becoming independent, or becoming social again. Being able to return to work, helping around the house, or not needing help from others were important indicators that life was starting to get back to normal. Although all participants had been able to take on some of their “usual” activities, none indicated they fully reclaimed who they once were.

I am back to working part-time … I go to the office and handover paperwork … I go to the grocery store now … I cook for myself now. (P6T2)

While progressing was measured in smaller benchmarks, reclaiming was measured in larger life events. However, reclaiming was dependent on progressing. The degree participants were able to reclaim varied depending on the degree of their progression.

Conditions

Conditions are events that alter interactions among categories and answer the why and how people respond in the way they do (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). The conceptual model illustrates that the interaction among the three categories is circuitous, not linear. The range in the number of curves in the model represents how conditions affect the movement from one category to another. Furthermore, conditions are temporal, causing the interaction among categories to widen or shrink, representing the degree of time participants spent in categories before moving onto the next phase. In extreme situations, a setback, such as bacteremia, caused a complete reversal in progress, pushing participants back to the beginning of Recovering Me. In this study, participants described two conditions, Being Delayed and Having Setbacks.

Being Delayed

Being Delayed occurred at both the Losing Me and Fixing Me phase and was caused by external forces (insurance requirements and authorization, surgeon and hospital scheduling backlog and errors, or the impact of COVID-19 on hospital settings). Being Delayed often resulted in significant anguish and worry that they would continue to rapidly decline and not be able to return to normal life. Participants described experiencing a sense of helplessness because they were unable to impact decisions being made at the health care level.

I saw therapy, a chiropractor, medications—I didn’t know which way to go. Then I saw the surgeon, then an MRI, then more meds, then had to wait more. (P9T1)

During Fixing Me, being delayed seemed to occur due to a lack of insurance authorization for transition to a rehabilitation setting. The delay caused emotional distress as participants identified recovery as not beginning until they were out of the hospital. Participants, waiting in the hospital, did not know when they would be able to begin their recovery and move forward.

Well, the insurance company wouldn’t pay for the one I wanted. It took them a few days to get another rehab. So, the insurance company plays a lot … Which is not good either, I don’t think. (P11T2)

Having Setbacks

Having Setbacks were described as acute medical problems that occurred after hospital discharge and within the first month after surgery during the Recovering Me phase. Setbacks stopped participants progress in Recovering Me and caused minor to a severe loss of progress. Setbacks (bacteremia, surgical site infection, kidney stones, and medication side effects) caused physical regression (weakness and functional loss), and emotional distress (worry and frustration). When the acute problem resolved, participants often described how much “they had lost” or having to work harder to get back to where they were. For some, setbacks required rehospitalization.

I was in rehab and I got a UTI, which turned into sepsis … I was extremely ill. But eventually, I went back to the rehab hospital. I had lost everything I’d gained. (P4T2)

Consequences

Actions persons take based on their understanding of events and occurrences often produce consequences (Strauss & Corbin, 1998). Due to limited provision of information, inability to prepare, setbacks and delays, participants had to continually set and adjust their expectations.

Setting and Adjusting Expectations

The constant Setting and Adjusting Expectations seemed dynamic, both influencing and being influenced by movement within the categories. When a condition influenced the interaction among the categories, for example, being delayed for surgery, participants had to adjust their recovery expectations. This often led to anguish and disappointment for participants. Adjustments often included a component of time. For example, how long participants stayed in one of the phases or duration before resuming social or family roles or returning to work. Not meeting a benchmark or being stalled in a phase caused disruption in participants’ personal timeline for recovering their normal life. For some, adjusting expectations occurred daily, making it challenging to set goals. This was particularly the case for those that had an acute medical illness that caused a setback in their progress.

You always got to adjust your expectations … most everything I do right now is almost like a little chore …. Now it’s taken a little time to get back to normal with this kidney problem. (P11T2)

Discussion

We investigated older adults’ understanding and experiences of living with and having surgery for DSD. Degenerative spinal disease is underdiagnosed in primary care for several reasons, including variability of symptoms, provider lack of confidence, unclear definitions, and the older adult themselves attributing functional decline as an expected part of aging (Chagnas et al., 2019; Jensen et al., 2020; Warmoth et al., 2016). Unfortunately, a delay in diagnosis leads to delays in both nonoperative treatment strategies (Wu et al., 2021) and in referrals to see a spine specialist. Furthermore, a delay in specialist referral can negatively affect outcomes, such as improvement in physical function (Cushnie et al., 2019). Our study identified that for patients, delays in the Losing Me phase had a psychological impact, causing excessive worry for participants that their strength would not return, they would have continued pain and further loss of socialization activities. The psychological impact of delays and the amount of work that persons with DSD must do to get a surgical intervention to treat their disease has been understudied.

Participants also experienced being delayed while waiting for insurance authorization to transition to a rehabilitation setting after surgery in the Fixing Me phase. The literature identifies that delays in transitioning out of the hospital after elective spine surgery due to waiting on insurance authorization resulted in a prolonged length of stay of 0.3 days in the Medicare population (mean age 69.9 years) and 1.4 days for participants with private insurance (mean age 67 years; Dosselman et al., 2021). Multiplied by the number of older people undergoing elective spine surgery, the costs to the institution in terms of decreased throughput as well as overall health care costs are extraordinary (Landeiro et al., 2019). A recent scoping review provided an in-depth depiction of older adults who experience delays in waiting to transition to assisted living, long-term care, or a nursing home. The review found that patients felt uninformed and uncertain of what or who to ask for information; spent much of the day waiting while being socially isolated due to the hospital physical environment and lack of planned activity; experienced physical and emotional deterioration; loss of control over how long the delay would take or where they would transition to; and a reluctant acceptance of the situation they were in (Everall et al., 2019). The experiences described by Everall et al. mirror our findings. Furthermore, critical to our participants, delays and waiting kept them from starting their recovery. Additional research on the effects of delays in the health care environment, both physically and emotionally, on older adults is needed.

Participants’ recovery trajectory seemed affected by being unprepared for surgery and for their recovery once discharged. A recent systematic review conducted to evaluate the effect of preoperative education on patients’ psychological, clinical, and economic outcomes after elective spine surgery only yielded seven studies. Unfortunately, these studies were limited due to weak methodology and only fair-quality evidence that supports the benefits of preoperative education (Burgess et al., 2019). Furthermore, a consensus statement regarding lumbar fusion surgery from the Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society strongly recommends preoperative patient education, but this is only supported with low quality of evidence (Debono et al., 2021). A systematic review evaluating ERAS® current trends in spine surgery in younger populations found only 16 of the 22 included studies provided any preoperative education in their protocol (Tong et al., 2020). Thus, while patient education seems obvious and key prior to surgery, the quality of evidence is low and only studied in younger populations. Our findings identified that older patients wanted and needed the education to be able to prepare for their spine surgery and recovery. Further research on when preoperative education should occur and what information older adults need to effectively manage their recovery and transitions is needed.

When participants experienced setbacks, the Recovering Me phase was prolonged. Interestingly, participants did not identify in-hospital medical complications, such as urinary retention or delirium, commonly reported in the literature (Strayer et al., 2022). Rather, participants identified complications as ongoing symptoms that were present prior to having surgery or symptoms arising during a protracted recovery. Ongoing symptoms were particularly stressful and problematic for participants and often not discussed with their health care provider. Thus, our findings highlight a gap in how medical complications are identified in the literature, in that the patient perspective is often missing. Additional research to understand how older adult patients conceptualize complications after surgery is needed.

Our findings about how older adults experience a transition from health to illness is similar to that described by Liebzeit et al. (2020). Participants in our study describe Losing Me due to DSD and the actions they took to address their symptoms and recovery to reclaim themselves. For our participants, Losing Me was protracted, often occurring over months to years, forcing them into a state of limbo until they could convince others or otherwise prove they needed help. In our study, participants experienced a loss in ability to participate in social life activities resulting in feelings of anxiety and fear. Liebzeit et al. (2020) describe this as losing normal. Their participants similarly described a loss in the ability to engage in social life activities and a process of working to get back to normal. Our findings and those of others (Arieli et al., 2022; Liebzeit et al., 2020) highlight the significance of engagement in social role and activity for older adults. The concept of participation has been defined as a person’s involvement in life situations and the extent to which individuals can engage in society (World Health Organization, 2001). Participation decline has been associated with depression and functional and cognitive loss in older adults (Rotenberg et al., 2019; Tomioka et al., 2018). Measures of participation provide a broader concept of functional recovery because they take into consideration how individuals are involved in life situations (World Health Organization, 2001) and the extent that persons engage in meaningful activities, such as leisure, recreation, sociocultural, and religion (Arieli et al., 2022). Thus, social participation is a functional marker for older people (Liebzeit et al., 2018), affecting healthy aging (Amagasa et al., 2017) and potentially how older adults recover from illness. Additional research is needed to understand the concept of participation and the impact of illness on participation and recovery in older adults.

Limitations

There are limitations to this study. Although our inclusion criteria included persons who underwent elective spinal surgery, none of our enrolled participants required cervical spinal procedures. Older people with different spinal conditions, such as cervical degenerative disease, or those who undergo spine surgeries for other causes (infection, cancer, and trauma) may experience recovery differently. Participants were recruited from a single large Midwestern hospital. Thus, older adults undergoing spine surgery in other types of hospitals might have different experiences. Also, data were collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. The patient experience may be influenced by health care organizations restrictions, such as limited nursing time in patient rooms, and limited visitation by family and friends. Finally, this study did not systematically gather the demographic characteristics of older adults who participated.

Implications

Understanding older adults experiences with disease management, as well as their personal goals for care and recovery (immediate and future) are foundational for delivering patient-centered care. Delays in diagnosis, as well as operative and nonoperative treatments can result in psychological distress, such as excessive worry, fear, and loss in social roles. Therefore, in addition to addressing physical symptoms of DSD, health care providers (medical and surgical) also need to assess the psychosocial impact of the disease to improve older adult recovery and functional outcomes. Participants often described feeling unprepared for spine surgery and postdischarge management. Tailoring presurgical and discharge education that aligns with older adults’ preferences is critical to improving transitions in care from home to hospital and hospital to home or rehabilitation. Finally, participants described complications after surgery as presence of ongoing symptoms or delays in recovery. Complications that are distressing to older adults in this study contrast with what is reported in the spine literature. Therefore, future research on how older adults define and experience complications is needed to develop more appropriate patient-centered outcomes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants for giving of themselves and sharing their experiences with us, in hopes of making it better for others. We would also like to thank Rachel Rutkowski, PhD and Youhung Her-Xiong, PhD, CAPSW for their participation in data analysis and Corey Nampel for graphic design of the conceptual model.

Contributor Information

Andrea L Strayer, School of Nursing, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA; College of Nursing, University of Iowa, Iowa City, Iowa, USA.

Barbara J King, School of Nursing, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, USA.

Funding

This work was supported by the Agnes Marshall Walker Foundation (AMWF.org); and the Jean E. Johnson Research Fund, University of Wisconsin–Madison School of Nursing. Scientific editing was supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program, through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), grant UL1TR002373. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Conflict of Interest

A. L. Strayer: Wolters-Kluwer: Royalties; Thieme Publishers: Royalties; Taylor Francis Publishers: Royalties.

B. J. King: None declared.

Data Availability

The analytic methods are explained in the manuscript and an example of the coding method utilized to analyze the data is included (Table 1). The data collected consists of 1:1 interviews that are not available for public use or viewing. This study was not preregistered.

References

- Accardi-Ravid, M., Eaton, L., Meins, A., Godfrey, D., Gordon, D., Lesnik, I., & Doorenbos, A. (2020). A qualitative descriptive study of patient experiences of pain before and after spine surgery. Pain Medicine, 21(3), 604–612. doi: 10.1093/pm/pnz090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amagasa, S., Fukushima, N., Kikuchi, H., Oka, K., Takamiya, T., Odagiri, Y., & Inoue, S. (2017). Types of social participation and psychological distress in Japanese older adults: A five-year cohort study. PLoS One, 12(4), e0175392. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0175392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arieli, M., Kizony, R., Gil, E., & Agmon, M. (2022). Many paths to recovery: Comparing basic function and participation in high-functioning older adults after acute hospitalization. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 41(8), 1896–1904. doi: 10.1177/07334648221089481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers, B. J. (1988). Grounded theory (p. 33). NLN publications(15-2233). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buehring, B., & Barczi, S. (2019). Assessing the aging patient. In Brooks N. P. & Strayer A. L. (Eds.), Spine surgery in an aging population (p. 208). Thieme Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, L. C., Arundel, J., & Wainwright, T. W. (2019). The effect of preoperative education on psychological, clinical and economic outcomes in elective spinal surgery: A systematic review. Healthcare (Basel), 7(1), 48. doi: 10.3390/healthcare7010048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buser, Z., Ortega, B., D’Oro, A., Pannell, W., Cohen, J. R., Wang, J., Golish, R., Reed, M., & Wang, J. C. (2018). Spine degenerative conditions and their treatments: National trends in the United States of America. Global Spine Journal, 8(1), 57–67. doi: 10.1177/2192568217696688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chagnas, M. O., Poiraudeau, S., Lefèvre-Colau, M. M., Rannou, F., & Nguyen, C. (2019). Diagnosis and management of lumbar spinal stenosis in primary care in France: A survey of general practitioners. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders, 20(1), 431. doi: 10.1186/s12891-019-2782-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cushnie, D., Thomas, K., Jacobs, W. B., Cho, R. K. H., Soroceanu, A., Ahn, H., Attabib, N., Bailey, C. S., Fisher, C. G., Glennie, R. A., Hall, H., Jarzem, P., Johnson, M. G., Manson, N. A., Nataraj, A., Paquet, J., Rampersaud, Y. R., Phan, P., & Casha, S. (2019). Effect of preoperative symptom duration on outcome in lumbar spinal stenosis: A Canadian Spine Outcomes and Research Network registry study. Spine Journal, 19(9), 1470–1477. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2019.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damsgaard, J. B., Jørgensen, L. B., Norlyk, A., & Birkelund, R. (2017). Spinal fusion surgery: From relief to insecurity. International Journal of Orthopaedic and Trauma Nursing, 24, 31–39. doi: 10.1016/j.ijotn.2016.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debono, B., Wainwright, T. W., Wang, M. Y., Sigmundsson, F. G., Yang, M. M. H., Smid-Nanninga, H., Bonnal, A., Le Huec, J. C., Fawcett, W. J., Ljungqvist, O., Lonjon, G., & de Boer, H. D. (2021). Consensus statement for perioperative care in lumbar spinal fusion: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Spine Journal, 21(5), 729–752. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2021.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosselman, L. J., Pernik, M. N., El Tecle, N., Johnson, Z., Barrie, U., El Ahmadieh, T. Y., Lopez, B., Hall, K., Aoun, S. G., & Bagley, C. A. (2021). Impact of insurance provider on postoperative hospital length of stay after spine surgery. World Neurosurgery, 156, e351–e358. doi: 10.1016/j.wneu.2021.09.065 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everall, A. C., Guilcher, S. J. T., Cadel, L., Asif, M., Li, J., & Kuluski, K. (2019). Patient and caregiver experience with delayed discharge from a hospital setting: A scoping review. Health Expectations, 22(5), 863–873. doi: 10.1111/hex.12916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira, M. L., & de Luca, K. (2017). Spinal pain and its impact on older people. Best Practices in Research and Clinical Rheumatolology, 31(2), 192–202. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fønss Rasmussen, L., Grode, L. B., Lange, J., Barat, I., & Gregersen, M. (2021). Impact of transitional care interventions on hospital readmissions in older medical patients: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 11(1), e040057. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-040057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory-strategies for qualitative research. Weiderfeld and Nicolson. Přejít k původnímu zdroji. [Google Scholar]

- Grotle, M., Småstuen, M. C., Fjeld, O., Grøvle, L., Helgeland, J., Storheim, K., Solberg, T. K., & Zwart, J. A. (2019). Lumbar spine surgery across 15 years: Trends, complications and reoperations in a longitudinal observational study from Norway. BMJ Open, 9(8), e028743. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hladkowicz, E., Dumitrascu, F., Auais, M., Beck, A., Davis, S., McIsaac, D. I., & Miller, J. (2022). Evaluations of postoperative transitions in care for older adults: A scoping review. BMC Geriatrics, 22(1), 329. doi: 10.1186/s12877-022-02989-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Horst, A. Y., Trompetter, H. R., Pakvis, D. F. M., Kelders, S. M., Schreurs, K. M. G., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2019). Between hope and fear: A qualitative study on perioperative experiences and coping of patients after lumbar fusion surgery. International Journal of Orthopaedic Trauma and Nursing, 35, 100707. doi: 10.1016/j.ijotn.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R. K., Jensen, T. S., Koes, B., & Hartvigsen, J. (2020). Prevalence of lumbar spinal stenosis in general and clinical populations: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Spine Journal, 29(9), 2143–2163. doi: 10.1007/s00586-020-06339-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenders, N., Rushton, A., Verra, M. L., Willems, P. C., Hoogeboom, T. J., & Staal, J. B. (2019). Pain and disability after first-time spinal fusion for lumbar degenerative disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Spine Journal, 28(4), 696–709. doi: 10.1007/s00586-018-5680-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landeiro, F., Roberts, K., Gray, A. M., & Leal, J. (2019). Delayed hospital discharges of older patients: A systematic review on prevalence and costs. Gerontologist, 59(2), e86–e97. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang, H., Lu, S., Jiang, D., & Fei, Q. (2020). Clinical outcomes of lumbar spinal surgery in patients 80 years or older with lumbar stenosis or spondylolisthesis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Spine Journal, 29(9), 2129–2142. doi: 10.1007/s00586-019-06261-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebzeit, D., Bratzke, L., Boltz, M., Purvis, S., & King, B. (2020). Getting back to normal: A grounded theory study of function in post-hospitalized older adults. Gerontologist, 60(4), 704–714. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnz057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebzeit, D., King, B., Bratzke, L., & Boltz, M. (2018). Improving functional assessment in older adults transitioning from hospital to home. Professional Case Manage, EMT, 23(6), 318–326. doi: 10.1097/ncm.0000000000000293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebzeit, D., Rutkowski, R., Arbaje, A. I., Fields, B., & Werner, N. E. (2021). A scoping review of interventions for older adults transitioning from hospital to home. Journal of the American Geriatric Society, 69(10), 2950–2962. doi: 10.1111/jgs.17323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, C. D., Boddapati, V., Lombardi, J. M., Lee, N. J., Saifi, C., Dyrszka, M. D., Sardar, Z. M., Lenke, L. G., & Lehman, R. A. (2020). Recent trends in medicare utilization and reimbursement for lumbar spine fusion and discectomy procedures. Spine Journal, 20(10), 1586–1594. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2020.05.558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oster, B. A., Kikanloo, S. R., Levine, N. L., Lian, J., & Cho, W. (2020). Systematic review of outcomes following 10-year mark of Spine Patient Outcomes Research Trial (SPORT) for spinal stenosis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 45(12), 832–836. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponkilainen, V. T., Huttunen, T. T., Neva, M. H., Pekkanen, L., Repo, J. P., & Mattila, V. M. (2021). National trends in lumbar spine decompression and fusion surgery in Finland, 1997–2018. Acta Orthopedia, 92(2), 199–203. doi: 10.1080/17453674.2020.1839244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg, S., Maeir, A., & Dawson, D. R. (2019). Changes in activity participation among older adults with subjective cognitive decline or objective cognitive deficits. Frontiers in Neurology, 10, 1393. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2019.01393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton, A., Jadhakhan, F., Masson, A., Athey, V., Staal, J. B., Verra, M. L., Emms, A., Reddington, M., Cole, A., Willems, P. C., Benneker, L., Heneghan, N. R., & Soundy, A. (2020). Patient journey following lumbar spinal fusion surgery (FuJourn): A multicentre exploration of the immediate post-operative period using qualitative patient diaries. PLoS One, 15(12), e0241931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0241931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research: techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (2nd ed.). Sage Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Strayer, A. L., Kuo, W. C., & King, B. J. (2022). In-hospital medical complication in older people after spine surgery: A scoping review. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 17(4), e12456. doi: 10.1111/opn.12456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberg, R., & Charmaz, K. (2014). Grounded theory and theoretical coding. In Flick U. (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 153–169). Sage Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tomioka, K., Kurumatani, N., & Hosoi, H. (2018). Social participation and cognitive decline among community-dwelling older adults: A community-based longitudinal study. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychology Sciences and Social Sciences, 73(5), 799–806. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbw059 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, Y., Fernandez, L., Bendo, J. A., & Spivak, J. M. (2020). Enhanced recovery after surgery trends in adult spine surgery: A systematic review. International Journal of Spine Surgery, 14(4), 623–640. doi: 10.14444/7083 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warmoth, K., Tarrant, M., Abraham, C., & Lang, I. A. (2016). Older adults’ perceptions of ageing and their health and functioning: A systematic review of observational studies. Psycholology, Health, and Medicine, 21(5), 531–550. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2015.1096946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner, N. E., Tong, M., Borkenhagen, A., & Holden, R. J. (2019). Performance-shaping factors affecting older adults’ hospital-to-home transition success: A systems approach. Gerontologist, 59(2), 303–314. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnx199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. (2001). International classification of functioning, disability and health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health [Google Scholar]

- Wu, A., Liu, L., & Fourney, D. R. (2021). Does a multidisciplinary triage pathway facilitate better outcomes after spine surgery? Spine, 46(5), 322–328. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000003785 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yachnin, D., Hladkowicz, E., & McIsaac, D. I. (2021). A qualitative analysis of patient-reported anticipated benefits of having elective surgery. Canadian Journal of Anaesthesia, 68(4), 589–590. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01893-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The analytic methods are explained in the manuscript and an example of the coding method utilized to analyze the data is included (Table 1). The data collected consists of 1:1 interviews that are not available for public use or viewing. This study was not preregistered.