Abstract

Rationale:

Recent studies on reinforcer valuation in social situations have informed research on mental illness. Social temporal discounting may be a way to examine effects of social context on the devaluation of delayed reinforcers. In prior research with non-drug-using groups we demonstrated that individuals discount delayed rewards less rapidly (i.e., value the future more) for a group of which they are a member than they do for themselves alone.

Objectives:

The current study examined how cigarette smoking and level of alcohol use relate to rates of delay and social temporal discounting.

Methods:

In this study, we used crowd-sourcing technology to contact a large number of individuals (N =796). Some of these individuals were hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (n= 269) whereas others were non-problem drinkers (n=523); some were smokers (n= 182) whereas others were non-smokers (n=614). Delay discounting questionnaires for individual rewards (me now, me later) and for group rewards (we now, we later; me now, we later) were used to measure individuals’ discounting rates across various social contexts.

Results:

Our analyses found that smokers discounted delayed rewards more rapidly than controls under all conditions. However, hazardous-to-harmful drinkers discounted delayed rewards significantly more rapidly than the non-problem drinkers under the individual condition, but not under the social conditions.

Conclusions:

These finding suggests that the use of different abused drugs may be associated with excessive discounting in the individual condition and have selective effects when discounting for a group in the social conditions.

Recent neuroeconomic research has shed new light on the role of social and group processes in various patterns of pathological behavior (i.e., mental illness; see Kishida et al. 2010, for a review). One aspect of these social processes involves reinforcer valuation in social contexts (see Kishida and Montague 2012). If addiction is seen as a pattern of pathological reinforcer valuation undergirded by neurological differences (see Bickel et al. 2012a; Bickel et al. 2011a, for a discussion), social aspects of reinforcer valuation may be particularly relevant to addiction.

The discounting of delayed reinforcers refers to the observation that the value of a reinforcer decreases as the delay to its receipt increases. Delay discounting studies have robustly contributed to our understanding of reinforcer valuation (Bickel et al. 2012b; Bickel and Marsch 2001; Reynolds 2006). Although these experiments often use psychophysical titration procedures (Du et al. 2002), comparable data can be obtained from brief questionnaire-based methods that quantify individuals’ rates of hyperbolic discounting (Kirby and Marakovic 1996; Kirby et al. 1999).

Given that delay discounting assessments (e.g., the delay discounting questionnaire) measure participants’ ability to exhibit self-control or to delay gratification (i.e., choose the larger but more delayed of two reinforcers), it is not surprising that almost every form of substance dependence is associated with greater rates of discounting future rewards than non-dependent controls. Moreover, studies have demonstrated excessive discounting rates among problem gamblers, the obese, individuals who engage in HIV risk behavior, individuals who engage in other poor health behaviors, children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, and schizophrenics (see Bickel et al. 2012b, for a review).

One advantage of the discounting concept is its adaptability. For example, discounting assessment procedures can be used to measure individuals’ valuations among losses as well as gains (Baker et al. 2003), among past outcomes as well as future ones (Bickel et al. 2008; Yi et al. 2006), among a wide variety of single commodities including drugs (see Bickel and Marsch 2001 for a review), food (Odum et al. 2006) , sex (Johnson and Bruner 2011; Lawyer et al. 2010) , and health (Baker et al. 2003; Odum et al. 2002), and among different commodities (i.e., cross-commodity temporal preference assessment, Bickel et al. 2011b). Importantly, value-discounting assessment has been extended to social phenomena. For example, Jones and Rachlin (2006) demonstrated that the amount of money a subject (benefactor) was willing to forgo so as to give 75 dollars to another person (beneficiary) decreased as a hyperbolic function of the social distance that the benefactor believed was between her/him and the beneficiary. Jones and Rachlin’s procedure examines the effect of social distance on value discounting, but not the effect of structural aspects of social context, such as whether the person making choices among rewards is doing so on behalf of a group. More recently, social temporal discounting procedures have been devised to study the latter kinds of effects. In these procedures, individuals make choices between a reward to be evenly divided amongst their group of unspecified individuals now vs. a larger reward to be shared amongst that same group later (i.e., “we now” vs. “we later”; Charlton et al. in press). For example, Charlton et al. (in press) compared individuals’ rates of standard delay discounting (i.e.., “me now” vs. “me later”) to their rates of social temporal discounting and found that subjects discount future monetary gains less when choosing for the group, even though the amount the individual earned was identical under the two conditions. These findings suggest that when making choices on behalf of their group, participants prefer alternatives geared towards the group’s long-term benefit. Whether similar results would be obtained with methods that combine standard discounting with social temporal discounting is unknown. In this study, we extend this research by examining the combination of social situations such that individuals make selections in choices between an immediate reward to be received only by the chooser vs. a delayed reward to be received by the chooser’s group (i.e., “me now” vs. “we later”).

Individuals’ rates of social temporal discounting may relate to their general pattern of trusting or distrusting others. Specifically, we may value providing reinforcers for others because we trust that they will reciprocate when given the opportunity (Kishida et al.). This type of interpersonal trust is often quantified via Rotter’s (1967) interpersonal trust scale (ITS). Because the ITS relates to other social phenomena such as interpersonal affect (e.g., gratitude, anger, etc.; Dunn and Schweitzer 2005) and interpersonal difficulties (e.g., cynicism/Machiavellianism; Gurtman 1992) it may help explain some social aspects of social temporal discounting. Moreover, the ITS, in combination with social temporal discounting measures, may provide unique insight into substance abuse.

To date, social temporal discounting has not been examined among individuals engaged in substance use. In this study, we examine the effects of smoking and alcohol drinking status on social temporal discounting. Given that individuals who smoke discount at higher rates than non-smokers (Bickel et al. 1999) and that both moderate and heavy drinkers discount more than light drinkers (Vuchinich and Simpson 1998), we might see this effect merely replicated across the delay discounting and social temporal discounting conditions. An alternative possibility is suggested by the increasing restrictions on smoking in social contexts (Gallus et al. 2011; Wackowski et al. 2011) and the sociality of drinking activity (Lin et al. 2011; Wood et al. 2011). We might find that hazardous and/or harmful drinkers’ higher-than-normal discounting rates may be selectively observed in a standard delay discounting condition (me now vs. me later) rather than in social temporal discounting condition. Specifically, smokers may discount more than non-smokers in all conditions, but although hazardous and/or harmful drinkers may discount more than non-problem drinkers in the standard delay discounting condition, similar higher than normal discounting rates may not be observed in the social temporal discounting condition.

To obtain the sample for this study we used crowd-sourcing technology, known as Amazon Mechanical Turk (AMT). AMT is an online marketplace where small tasks can be posted for human workers to complete. As noted by Sprouse (2011, p 155), “AMT provides instantaneous access to thousands of potential participants and provides the tools necessary to distribute surveys, collect responses, and disburse payments.” Thus, in this exploratory study we used AMT to distribute delay discounting assessments, a demographics questionnaire, and questions about participants’ smoking status, and alcohol consumption. The discounting assessments were of three types – standard delay discounting (me now vs. me later), social temporal discounting (we now vs. we later), and a combination of these two types of discounting (me now vs. we later).

Method

Participants

Participation in the present survey study occurred via completion of a Human Intelligence Task (HIT) using the AMT crowd-sourcing service. Only AMT users for whom previous requesters had accepted 90 percent of their previous HITs could access the survey. The Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board deemed the project exempt from review (not requiring obtainment of written, signed consent); nevertheless, although participants did not explicitly provide informed consent, they were provided an overview of the study and indicated that they understood the description. The current study only analyzed data from participants from the United States. 1190 individuals from the United States completed the survey. To ensure that data were from participants who carefully completed the survey, a HIT was not accepted if the participant (a) failed to indicate that they understood the instructions, (b) did not complete more than 80% of the survey items, or (c) completed the survey in less than 800 seconds. Additionally, a participant’s data were excluded from analysis if they reflected non-varying responses (i.e., complete insensitivity to the measure) on any of the three discounting measures. Analyses presented are from the 796 participants with data that passed all of these screening criteria (see Table 2 for demographic information).

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics and Spearman correlations among demographic and discounting measures.

| Gender (%Fcmalc) | Age (jtfHCS) | Education | Income (USD/year) | % Smokers | AUDIT | ITS | MM(ln[k]) | MW(ln[k]) | WW(ln[k]) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 55% | 31.31 | -------------- | S32130.23 | 23% | 4.58 | 87.46 | −4.10 | −4.64 | −4.62 |

| SD | -------------- | 11.44 | -------------- | S35037.95 | -------------- | 4.84 | 10.27 | 1.06 | 1.21 | 1.09 |

| Median | -------------- | 28 | -------------- | S21249.50 | -------------- | 3 | 88 | −4.167 | −4.620 | −4.620 |

| IQR | -------------- | 28,37 | -------------- | S6999.50, | -------------- | 1,6 | 81,94 | −4.794, | −5.473, | −5.473, |

| S46249.50 | −3.305 | −3.839 | −3.915 | |||||||

| Education (distribution) | <HS: 1.7% HS: 10.2% SC: 35.8% AAr |

|||||||||

| % Smokers | 0.026 | 0.056 | −0.177*** | −0.016 | ||||||

| AUDIT | −0.150*** | −0.168*** | 0.020 | −0.041 | 0.195*** | |||||

| ITS | −0.023 | −0.039 | −0.154*** | −0.052 | 0.085* | −0.001 | ||||

| MM | 0.013 | −0.089* | −0.186*** | −0.111* | 0.170*** | 0.080* | 0.101 | |||

| MW | −0.001 | −0.047 | −0.106* | −0.054 | 0.119** | 0.038 | 0.088 | 0.627*** | ||

| WW | −0.046 | −0.063 | −0.132** | −0.076* | 0.108** | 0.064 | 0.058 | 0.751*** | 0.665*** |

Age, income, alcohol use disorder identification test (AUDIT) score, interpersonal trust scale (ITS) score, and discounting rates (i.e., ln[k] from the me now, me later [MM], the me now, we later [MW], and we now we later [WW] questionnaires) are shown as means and standard deviations (SD). Education is shown as the proportion of participants that: had less than a high school diploma (<HS), with a high school diploma (HS), that had attended some college but did not earn a degree (SC), with an associates degree (AA), with a bachelors degree (BA), and with more than a bachelors degree (>BA). Gender is shown as the percent of the sample that was female and smoking status was shown as the percent of the sample that smoked cigarettes. Spearman correlations are shown in the bottom half of the table.

<.05,

<.001,

<.0001.

Materials

The data represent a subset of answers to questions in an approximately 200-question survey about health, social behaviors and decision-making. Participant responses included demographic information (e.g., gender, age, level of education, smoking status, etc.), the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT; Saunders et al. 1993) and the interpersonal trust scale (ITS; Rotter 1967). The survey items occurred in the same order for all participants, with one exception: the order of the three delay discounting assessments was changed for a subset of participants in order to test for order effects.

The Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT):

The AUDIT is a10-item structured questionnaire that asks questions about individuals’ consumption of, dependence on, and problems related to their consumption of alcoholic beverages. Each question is scored on a 0–4 scale. Individuals scoring under 8 are categorized as non-problem drinkers; those scoring 8 and higher are categorized as hazardous–to-harmful drinkers. Fourteen of these individuals scored over 20 (i.e., possibly met the criteria for diagnosis of alcohol dependence). Additionally, in accordance with the AUDIT scoring guide (Babor et al. 2001), anyone with a non-zero score on items 7–10 was classified as having some potential alcohol-related harm. Analyses that included these individuals with some potential alcohol-related harm in the hazardous-to-harmful drinker group provided near identical results to analyses that excluded those individuals. All analyses presented included individuals with some potential alcohol-related harm in the hazardous-to-harmful drinker group.

The Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence:

The FTND is a 6-item questionnaire that collects responses that indicate nicotine dependence on a 0–10 scale. Scores of 4 or below indicate low to moderate dependence, while scores of 5 or above suggest significant dependence.

Interpersonal Trust Scale (ITS):

The ITS is a 25-item scale that asks questions about individuals’ trust of other individuals, the government, and the media. Questions are asked in a Likert-type format, and the scores (i.e., high versus low scores) that indicated trust versus distrust varied from question to question.

Additionally, three 21-question subsets constituted three discounting assessments. Each subset was analogous to the 21-question delay-discounting assessment instrument presented in Kirby and Marakovic (1996). Each question presented a choice between hypothetically receiving monetary gains, in amounts also adapted from the Kirby and Marakovic (1996). Some outcomes involved rewards to be received by the participant alone; other outcomes were to be shared by a group of ten persons including the respondent (see Table 1 for a complete list of the discounting questions, and the order in which they appeared). The three types of discounting measures were as follows:

Table 1.

Order of the specific questions asked on each of the three discounting surveys and associated discounting rates

| Order | Choice on MM Survey | Choice on WW Survey | Choice on MW Survey | K | Rank |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | $34 tonight, for you alone, or $35 in 43 days, for you alone | $340 tonight, for the group, or $350 in 43 days, for the group | $34 tonight, for you alone, or $350 in 43 days, for the group | 0.0007 | 1 |

| 15 | $53 tonight, for you alone, or $55 in 55 days, for you alone | $530 tonight, for the group, or $550 in 55 days, for the group | $53 tonight, for you alone, or $550 in 55 days, for the group | 0.0007 | 1 |

| 7 | $83 tonight, for you alone, or $85 in 35 days, for you alone | $830 tonight, for the group, or $850 in 35 days, for the group | $83 tonight, for you alone, or $850 in 35 days, for the group | 0.0007 | 1 |

| 20 | $27 tonight, for you alone, or $30 in 35 days, for you alone | $270 tonight, for the group, or $300 in 35 days, for the group | $27 tonight, for you alone, or $300 in 35 days, for the group | 0.0032 | 2 |

| 9 | $48 tonight, for you alone, or $55 in 45 days, for you alone | $480 tonight, for the group, or $550 in 45 days, for the group | $48 tonight, for you alone, or $550 in 45 days, for the group | 0.0032 | 2 |

| 12 | $65 tonight, for you alone, or $75 in 50 days, for you alone | $650 tonight, for the group, or $750 in 50 days, for the group | $65 tonight, for you alone, or $750 in 50 days, for the group | 0.0031 | 2 |

| 8 | $21 tonight, for you alone, or $30 in 75 days, for you alone | $210 tonight, for the group, or $300 in 75 days, for the group | $21 tonight, for you alone, or $300 in 75 days, for the group | 0.0057 | 3 |

| 16 | $47 tonight, for you alone, or $50 in 60 days, for you alone | $470 tonight, for the group, or $500 in 60 days, for the group | $47 tonight, for you alone, or $500 in 60 days, for the group | 0.0055 | 3 |

| 14 | $30 tonight, for you alone, or $35 in 20 days, for you alone | $300 tonight, for the group, or $350 in 20 days, for the group | $30 tonight, for you alone, or $350 in 20 days, for the group | 0.0083 | 4 |

| 10 | $40 tonight, for you alone, or $65 in 70 days, for you alone | $400 tonight, for the group, or $650 in 70 days, for the group | $40 tonight, for you alone, or $650 in 70 days, for the group | 0.0089 | 4 |

| 3 | $67 tonight, for you alone, or $85 in 35 days, for you alone | $670 tonight, for the group, or $850 in 35 days, for the group | $67 tonight, for you alone, or $850 in 35 days, for the group | 0.0077 | 4 |

| 18 | $50 tonight, for you alone, or $80 in 70 days, for you alone | $500 tonight, for the group, or $800 in 70 days, for the group | $50 tonight, for you alone, or $800 in 70 days, for the group | 0.0086 | 4 |

| 11 | $25 tonight, for you alone, or $35 in 25 days, for you alone | $250 tonight, for the group, or $350 in 25 days, for the group | $25 tonight, for you alone, or $350 in 25 days, for the group | 0.0160 | 5 |

| 2 | $40 tonight, for you alone, or $55 in 25 days, for you alone | $400 tonight, for the group, or $550 in 25 days, for the group | $40 tonight, for you alone, or $550 in 25 days, for the group | 0.0150 | 5 |

| 19 | $45 tonight, for you alone, or $70 in 35 days, for you alone | $450 tonight, for the group, or $700 in 35 days, for the group | $45 tonight, for you alone, or $700 in 35 days, for the group | 0.0159 | 5 |

| 21 | $16 tonight, for you alone, or $30 in 35 days, for you alone | $160 tonight, for the group, or $300 in 35 days, for the group | $16 tonight, for you alone, or $300 in 35 days, for the group | 0.0250 | 6 |

| 6 | $32 tonight, for you alone, or $55 in 20 days, for you alone | $320 tonight, for the group, or $550 in 20 days, for the group | $32 tonight, for you alone, or $550 in 20 days, for the group | 0.0359 | 6 |

| 17 | $40 tonight, for you alone, or $70 in 20 days, for you alone | $400 tonight, for the group, or $700 in 20 days, for the group | $40 tonight, for you alone, or $700 in 20 days, for the group | 0.0375 | 6 |

| 5 | $15 tonight, for you alone, or $35 in 10 days, for you alone | $150 tonight, for the group, or $350 in 10 days, for the group | $15 tonight, for you alone, or $350 in 10 days, for the group | 0.1333 | 7 |

| 13 | $24 tonight, for you alone, or $55 in 10 days, for you alone | $240 tonight, for the group, or $550 in 10 days, for the group | $24 tonight, for you alone, or $550 in 10 days, for the group | 0.1292 | 7 |

| 1 | $30 tonight, for you alone, or $85 in 14 days, for you alone | $300 tonight, for the group, or $850 in 14 days, for the group | $30 tonight, for you alone, or $850 in 14 days, for the group | 0.1310 | 7 |

Delay discounting for me now, me later (MM).

Participants chose between receiving a hypothetical amount of money immediately, or at specified delays. For instance, the choice was between “$25 tonight, for you alone” or “$35 in 25 days, for you alone” (see Table 1 for details).

Delay discounting for we now, we later (WW).

Participants chose between hypothetical money to be divided equally amongst a group of ten anonymous individuals that included the participant. In this questionnaire, the phrase “for you alone” was replaced by “for the group” and the monetary outcomes were multiplied by ten. For example, one item gave participants the choice between “$250 tonight, for the group” or “$350 in 25 days, for the group” (see Table 1 for details).

Delay discounting for me now, we later (MW).

Participants chose between amounts of money immediately “for you alone,” or later “for the group” constituted of ten anonymous individuals including the participant. As with the WW questions, the size of the group rewards were also multiplied by 10. For example, “$25 tonight for you alone” or “$350 in 25 days for the group” (see Table 1 for details).

Procedures

Participants accessed the survey by logging onto the AMT service and clicking on the HIT entitled “Decision Making Study.” Participants first read an overview of the study and agreed to participate by checking an on-screen box. Monetary compensation was provided for timely and accurate completion of the survey. Participants received $2.50 for submission of the survey and could receive an additional $2.50 bonus. HITs were not accepted if participants completed the survey in less than 800 s (the average completion time was 1472 s), or if they did not indicate that they understood the instructions. Respondents did not receive a $2.50 bonus if two or more discounting questions were left unanswered, or if they provided an unvarying response pattern within a delay-discounting section of the survey. 1143 subjects completed a version of the survey that presented the three discounting conditions in the order listed above (i.e., MM, WW, MW), whereas 47 subjects completed the survey in the reverse order (i.e., MW, WW, MM). No significant differences were seen between data collected with these orderings. Because we did not see differences in the data from these two orderings, we did not test the third potential order (i.e., WW, MW, MM) and the data from the two orderings are combined and analyzed together.

Data analysis

For each of the three discounting measures, an estimated discounting rate (the free parameter “k” from Mazur’s (1987) hyperbolic discounting equation) was computed following a method modified from Kirby and Marakovic (1996). For each of the 21 questions, the respondent chose between a smaller, more immediate reward and a larger, delayed reward. For the purposes of data analysis, the 21 questions can be organized into seven ranked categories (see Table 1), which reflect degrees of participant impulsivity – a ranking of 1 being least impulsive and a ranking or 7 being most impulsive. The implications of such an organizing system is that the point in the ranked sequence of questions at which a participant switches from choosing the smaller-sooner alternative to the larger-later alternative may place that participant into one of the seven ranked categories of impulsiveness, and may be used to assign a particular k parameter value to that participant (see Table 1). Ties between equally plausible parameter values were resolved by taking the geometric mean of the plausible values. The natural log of Mazur’s (1987) free parameter “k,” ln(k), was used to quantify discounting for each individual. This logarithmic transformation was performed because delay-discounting rates are often not normally distributed. The natural logarithmic translation was used to remain consistent with previous reports (e.g., Bickel et al. 2011b; Bickel et al. 2011c; Washio et al. 2011). This analytical method was repeated for each of the three types of discounting. Spearman correlations based on these data, and relevant subject-related variables (e.g., age, income, education, smoking status, AUDIT score, ITS score) were calculated. Spearman correlation is a rank-based non-parametric measure of association that is appropriate for ordinal (including continuous) data. Although some of these correlations were significant, none were used as covariates in further analyses.

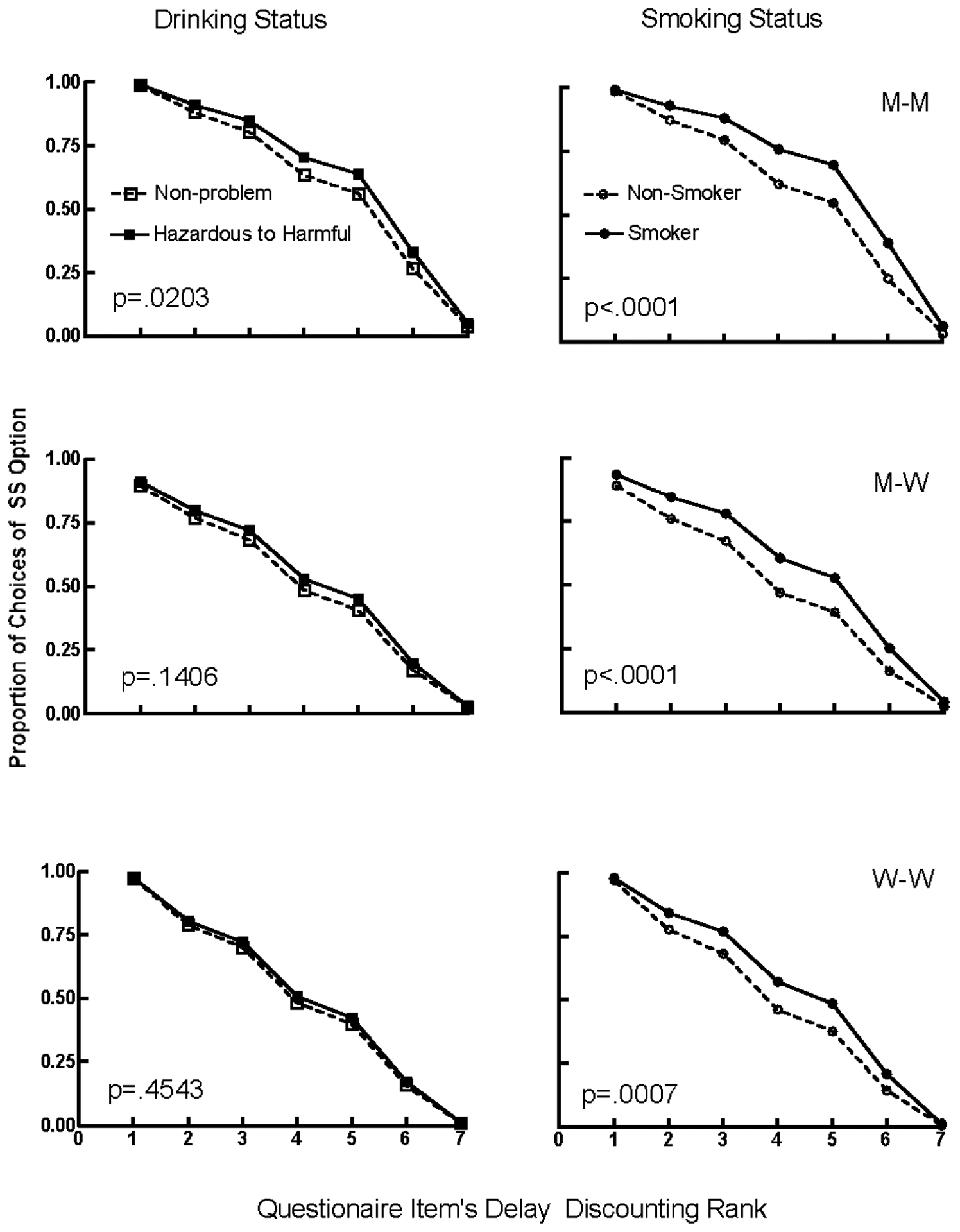

For participant groupings of interest, data from the discounting assessments were also analyzed for each of Kirby and Marakovic’s (1996) seven ranks as a proportion of “smaller-sooner” choices made by subjects in the group. Statistical tests for group differences in the percent of choices for the smaller-sooner option were based on logistic regression models that modeled multiple questions on the same subject using a repeated measures model with the GENMOD procedure in SAS (version 9.2, Cary, NC). For the purposes of the proportion smaller-sooner plots (i.e., Figures 1 and 2), individuals were grouped as smokers or non-smokers (based on the question “do you smoke cigarettes?”) and as non-problem drinkers (i.e., AUDIT score less than 8 for males and 7 for females) and hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (AUDIT score of 8 or more). For all analyses the type I error rate was set to five percent (i.e. α=0.05).

Fig 1.

The proportion of choices of the smaller-sooner option (y-axis) on questionnaire items that correspond with the seven discounting rate ranks (see Table 1 for details; x-axis) for non-problem drinkers (n=523; open squares) versus hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (n=269; closed squares; left column) and for non-smokers (n=614; open circles) versus smokers (n=182; closed circles; right column). The top row shows responding on the MM questions, the middle row shows responding on the MW questions, and the bottom row shows responding on the WW questions.

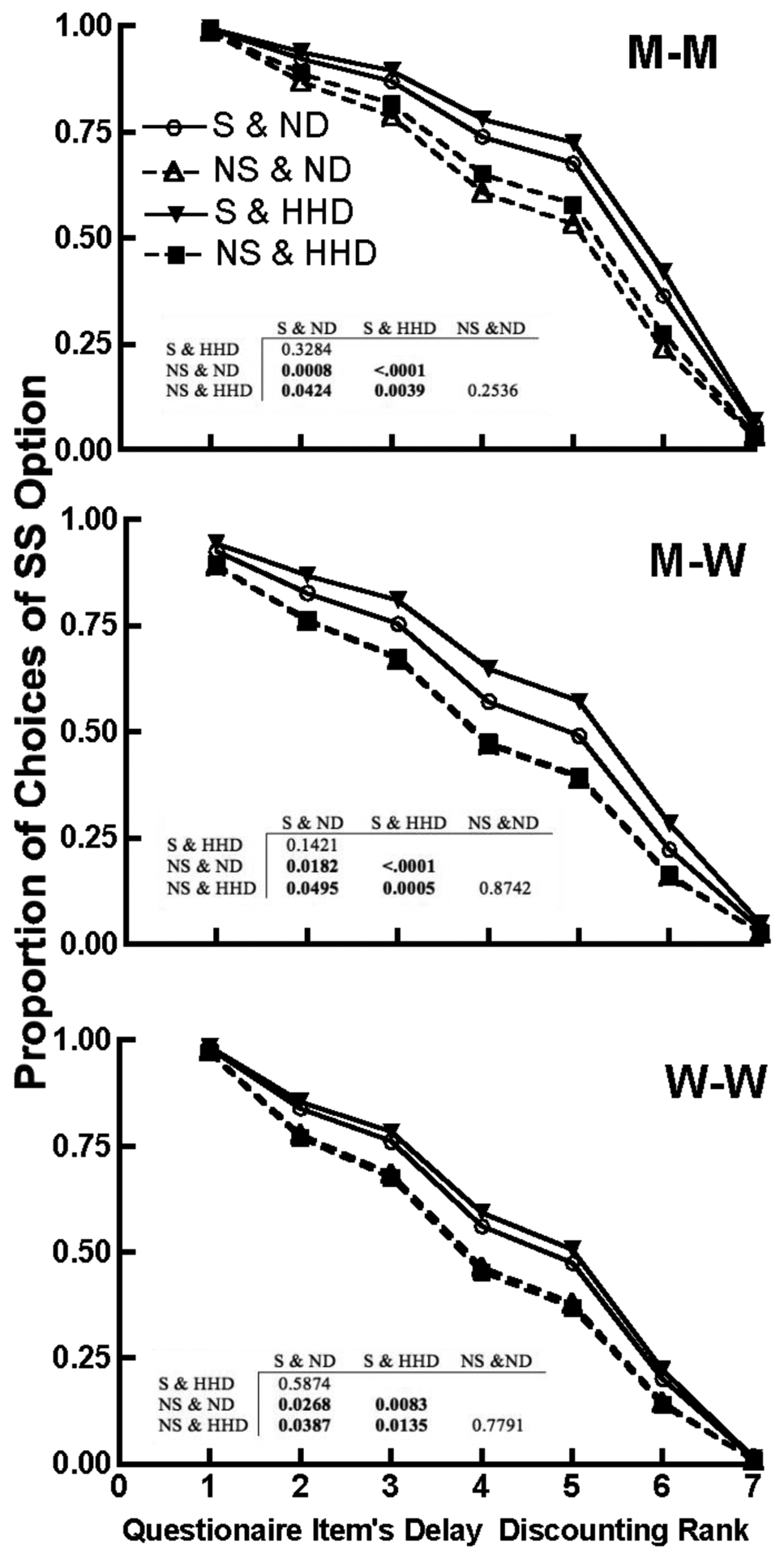

Fig 2.

The proportion of choices of the smaller-sooner option (y-axis) on questionnaire items that correspond with the seven discounting rate ranks (see Table 1 for details; x-axis) for non-smokers who are non-problem drinkers (NS & ND; n=427; open triangles), non-smokers who are hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (NS & HHD; n=96; closed squares), smokers who are non-problem drinkers (S & ND; n=185 ;open circles), and smokers who are hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (S & HHD; n=84; closed inverted triangles), on the MM (top panel), MW (middle panel), and WW (bottom panel) questionnaires. The p values for t-tests comparing each of these groups to the others are presented in the embedded tables.

Results

Discounting of others’ rewards, alone, and by smoking and/or drinking status

Mean delay-discounting rates (i.e., ln[k]) were higher in the MM condition (M = −4.10) than they were in the MW (M = −4.64; t=16.06, df=1590, p<.0001) or WW (M= −4.62; t=15.58, df=1590, p <.0001) conditions but there were no significant differences between discounting rates in the MW and WW conditions (t=0.477, df=1590, p = 0.6337). These two-tailed tests are based on a model that accounts for subject-to-subject variability as a random effect. Consistent with previous findings (Charlton et al. in press), these results suggest that our participants attributed value to the receipt of rewards by others.

Among the 182 smokers in the analysis, 171 completed the entire FTND questionnaire. The distribution of FTND scores for these data exhibited right skew, so Spearman’s correlation was used to assess the relationship between FTND score and the three discounting types among smokers. Significance testing based on the Spearman’s correlation did not reveal significant relationships between FTND score and any of the discounting measures (Spearman correlations of 0.05, 0.13, and 0.14; p-values 0.52, 0.08, and 0.06 comparing FTND with ln(k) for MM, MW, and WW respectively). This is surprising given that previous research has linked the FTND, particularly the question concerning how soon one smokes after waking, to discounting rate (Sweitzer et al. 2008). Because of this, smoking status is modeled as a binary variable (smoker/non-smoker) in subsequent analyses (see also, Bickel et al. 1999; Bickel et al. 2008; Mitchell 1999; Reynolds et al. 2003; Reynolds et al. 2004).

Based on previous findings, individuals who smoked cigarettes, and/or scored higher on the AUDIT were expected to discount at higher rates. These hypotheses were supported by one-sided two-sample t tests showing that discounting rates were significantly higher for smokers relative to non-smokers (MM: t794=5.02, p<.0001; MW: t794=2.89 ,p=0.002; WW: t794=3.29 ,p= 0.001) and discounting rates were higher for hazardous-to-harmful drinkers compared to non-problem drinkers in the non-social discounting condition. (MM: t790=2.19,p= 0.014; MW: t790=1.28, p=0.100; WW: t790=1.32,p= 0.0944). Moreover, although ITS score was significantly but not highly correlated with discounting rate (see Table 2), ITS score was not highly correlated with either smoking status or AUDIT score, suggesting that ITS score may account for unique variance in discounting rates, adding to the prediction based on smoking/drinking status, particularly in the MW and WW conditions.

A statistical model including smoking status, categories based on AUDIT score (i.e., non-problem versus hazardous/harmful), and ITS score was constructed to determine whether each variable had a significant association with ln(k) after accounting for the other predictors in the model. No higher-order interaction terms were significant in these data, so only main effects were modeled. Smoking status was significantly associated with ln(k) after accounting for AUDIT score category and ITS score (MM: F1,775=20.18, p=<.0001; MW: F1,775=7.56, p=0.006; WW: F1,775=9.47, p=0.002). ITS. ITS score was also significantly associated with ln(k) in the MM and MW conditions after accounting for AUDIT scores and smoking status (MM: F1,775=6.85, p=0.009; MW: F1,775=7.03, p=0.0082; WW: F1,775=2.64, p=0.104), whereas AUDIT category (MM: F1,775=2.45, p=0.118; MW: F1,775=0.88, p=0.3487; WW: F1,775=1.17, p=0.2789) did not provide a unique ability to predict ln(k) after accounting for the contributions of smoking status and ITS score. This suggests, that at least in the current case, 1) elevated rates of delay discounting in hazardous-to-harmful drinkers may result from the high correlation between smoking status and AUDIT score, and 2) the ITS score adds predictive utility when accounting for other discounting-related phenomena (i.e., smoking status).

Correlational analysis.

Table 2 shows the Spearman correlations between the median delay discounting rates and smoking status, AUDIT score, ITS score, and a host of demographic variables. The rates of discounting across all three of our delay-discounting tasks were highly intercorrelated, but ln(k) was highest in the individual discounting condition (i.e., MM). These findings are consistent with the notion that discounting has a trait-like cross-situational stability (Odum 2011a; b), but can be systematically manipulated by contextual variables (see Koffarnus et al. under review, for a review).

Due to the social nature of activities such as drinking, some variables were expected to differentially correlate with discounting rates as measured in the three discounting assessments that differ with regard to involvement of social variables. Variables such as educational level and smoking status were related to discounting rate across all three discounting conditions (see Table 2), suggesting that these variables similarly predict discounting across both non-social (individual) and group contexts. By contrast, variables such as age, and AUDIT score were significantly correlated with discounting only in the MM condition. Thus, age and AUDIT score differentiate individuals in individual discounting contexts, but not group contexts. These findings suggest that although some robust predictor variables (e.g., educational level, smoking status) are related to discounting across contexts, social situations obscure the influence of other variables (e.g., age, AUDIT score). This may be because these variables interact with social context. In particular, hazardous-to-harmful drinkers are different from non-problem drinkers when making choices about their rewards, but not when making choices that involve rewards that others’ may receive.

Effects of smoking and/or drinking status on impulsive choice.

Both smoking and drinking status may impact the proportion of impulsive choices (i.e., choices for the smaller-sooner [SS] option) that individuals made, particularly at the intermediate discounting ranks (i.e., 2–6). Figure 1 shows the proportion of choices for the SS alternative (y-axis) at each discounting questionnaire rank (x-axis) for smokers (n=182; closed circles) relative to non-smokers (n= 614; open circles) and for non-problem drinkers (n= 523; open squares) relative to hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (n= 269; closed squares). These proportions were estimated using a logistic regression model that treated multiple measurements on the same subject as a repeated measure effect using generalized estimating equations. Data are presented for the MM, MW, and WW conditions in the top, middle, and bottom rows, respectively. The proportion of choices of the SS option was higher for smokers relative to non-smokers on all three delay-discounting questionnaires, and also was higher for hazardous-to-harmful relative to non-problem drinkers on the MM questionnaire. Thus, as was seen in the correlational analysis, although hazardous-to-harmful drinkers significantly differ from non-problem drinkers in their choices for their own rewards (i.e., MM), they do not significantly differ in their choices that involve rewards that others may receive (i.e., the WW condition). These differences, however, were not observed at the extreme discounting ranks (i.e., 1 & 7), suggesting that the effect is selective (i.e., restricted to intermediate values) rather than general.

AUDIT score and smoking status both predicted discounting rate; however, smoking status accounted for more variance when both variables were modeled together. Given these results, smokers would be expected to have the highest proportion of SS choices, and within the smoker and non-smoker groups, the hazardous-to-harmful drinkers would chose the SS option more than the non-problem drinkers. Figure 2 shows the percent of choices for the smaller-sooner alternative in the MM (top panel), MW (middle panel), and WW (bottom panel) discounting assessments for non-smokers who are non-problem drinkers (open triangles), for non-smokers who are hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (closed squares), for smokers who are non-problem drinkers (open circles), and for smokers who are hazardous-to-harmful drinkers (inverted closed triangles). Consistent with our predictions, the proportion of choices for the smaller-sooner reinforcer was consistently lowest for non-smokers who are non-problem drinkers, followed by non-smokers who were hazardous-to-harmful drinkers. These findings further support the notion that although drinking status differentiates individuals when choosing rewards to be received as individuals, drinking status does not differentiate them when making decisions about rewards to be shared among a group.

Discussion

In this study we used crowd-sourcing technology (i.e., AMT) to obtain discounting data from a large sample of smokers vs. nonsmokers and non-problem drinkers, vs. hazardous-to-harmful drinkers, in various conditions that assessed the effects of social variables on discounting rates. We found that reinforcer valuation in the social context was selectively associated with cigarette smoking, but not hazardous-to-harmful alcohol use. Specifically, consistent with previous observations, we found that greater discounting was observed in the standard discounting condition with hazardous-to-harmful alcohol use (e.g., Vuchinich and Simpson 1998). However, when examined in the social temporal discounting conditions, we found that greater rates of discounting were observed among smokers but not among hazardous-to-harmful drinkers. Moreover, when accounting for the relation between discounting rate and smoking, discounting rate was not significantly related to drinking status. Thus, although the current findings replicated previous findings regarding the relation between drinking status and discounting (Bjork et al. 2004; Courtney et al. 2011; Dom et al. 2006; Mitchell et al. 2005; Petry 2001; Stea et al. 2011; Vuchinich and Simpson 1998), this effect may not be as robust as previously thought, and possibly secondary to the effect of smoking status. Also, discounting rates across our variety of discounting procedures were significantly correlated with each other, consistent with prior findings for other types of discounting (see Odum 2011a, for a discussion). Additionally, age was correlated with standard temporal discounting rates, and education with rates from all our discounting procedures. Although ITS scores and income were both correlated with standard (me now vs. me later) discounting, income was also correlated with social temporal discounting rates (we now vs. we later) but ITS scores were additionally correlated discounting rates from the combined standard-social discounting procedures. There are five points we would like to make about this exploratory research.

First, we replicated previous findings regarding the effects of smoking on standard temporal discounting rates (Baker et al. 2003; Bickel et al. 1999; Bickel et al. 2008; Businelle et al. 2010; Johnson et al. 2007; Mitchell 1999; Odum et al. 2002; Reynolds et al. 2009; Reynolds and Schiffbauer 2004; Rezvanfard et al. 2010) . Also, our observation that hazardous-to-harmful alcohol drinking affects these discounting rates is consistent with previous reports (Bjork et al. 2004; Courtney et al. 2011; Dom et al. 2006; Mitchell et al. 2005; Petry 2001; Stea et al. 2011; Vuchinich and Simpson 1998). As noted above, however, the effects of drinking status were not significant when accounting for smoking status. Our support for the reliability of these observations comes from a new, crowd-sourcing, approach to obtaining data on discounting.

Second, the effects of smoking status and alcohol problems on social temporal discounting were selective. Smokers discounted more than non-smokers on the social temporal discounting and on the combined discounting task (me now vs. we later), whereas hazardous-to-harmful drinkers failed to show a difference from non-problem drinkers on social temporal discounting. This may be because smoking has become a more solitary activity than the consumption of alcohol, perhaps as places where smoking is allowed are becoming increasingly restricted. Examination of these social conditions among other groups known to exhibit greater discounting rates in the standard condition would be interesting, as it would indicate which of these effects (selective or non-selective) are more frequently observed.

Third, the use of crowd-sourcing provides a relatively novel method to collect large samples from participants, permitting exploration of novel questions related to drug abuse and behavioral economic measures (e.g., delay discounting). As we noted above, we used AMT to replicate the higher discounting rates typically seen in smokers and hazardous-to-harmful drinkers, demonstrating that these new crowd-sourcing methods can be used effectively for discounting research. Moreover, we also replicated the relations between standard temporal discounting and education (Jaroni et al. 2004), age (Green et al. 1994; Green et al. 1996) and income (Green et al. 1996) further demonstrating both the reliability of these effects and the viability of collecting delay discounting data via AMT. This consistency between present and previous findings is particularly encouraging given that the AMT platform allows for the rapid collection of data from a diverse non-clinical non-university sample, increasing the generalizability of the findings.

Fourth, the current study was the first to link trust, as measured by the ITS (Rotter 1967), to either rates of delay discounting or to substance abuse status. Interpersonal trust was of particular interest because of our social context manipulations, yet ITS score was modestly correlated with discounting measures that did (me now vs. we later) and did not (me now vs. me later) have a social context component, and accounted for unique variance in discounting rates. These findings suggest that interpersonal trust, and related constructs such as emotion (Dunn and Schweitzer 2005) or loneliness (Rotenberg 1994), may contribute to the impaired decision making of addicted individuals. These are possibilities that await future study.

Fifth, the major challenges that limit the conclusions made in the current study have been addressed in previous reports. These assessments determined discounting rates for hypothetical monetary amounts, and as such may differ from conditions in which real monetary reinforcers were employed. Although this is always a concern when hypothetical rewards are employed, the empirical results are that use of hypothetical rewards in discounting assessments has produced results comparable to procedures using real rewards in behavioral studies (Baker et al. 2003; Bickel et al. 2009; Johnson and Bickel 2002; Johnson et al. 2007; Madden et al. 2003; Madden et al. 2004) and neuroimaging research (Bickel et al. 2009), and has been shown to be predictive of actual monetary behavior (Bickel et al. 2010). Despite those results supporting the validity of using hypothetical rewards in standard temporal discounting procedures, their use in assessment procedures that involve social variables has not been compared to real outcomes. Thus, the validity of the extension of the supporting argument to our social results remains an open question.

Additionally, the monetary totals presented in MW and WW conditions were ten times as large than those presented in the MM condition (e.g., $350 versus $35). Although the participants were told they would only receive 1/10 of the reward in the social temporal discounting conditions (i.e., MW and WW), the low discounting rates seen in those conditions may be due to a magnitude effect. Charlton et al. (in press), however, conducted a series of experiments wherein, after demonstrating lower discounting rates in the WW relative to the MM condition (Experiment 1), they made the size of the reinforcer in each condition equal by increasing the size of the MM reinforcers (Experiment 2) and made the amount each individual would receive explicit (Experiment 3). Discounting rates in the WW condition were lower than those in the MM condition in each experiment, suggesting that the changes in discounting rate were not due to a magnitude effect. Based on the procedural similarities between the current study and the Charlton et al. study, it is unlikely that the present results are due to a magnitude effect.

Lastly, the proportion of subjects who provided valid data in the present experiment (i.e., 796 out of 1190 respondents; i.e., 67%) was slightly lower than other experiments using similar questionnaires (528 of 672; i.e., 79%; Kirby and Marakovic 1996). The current experiment, however, required that participant’s data from all three of the questionnaires be orderly. Although this stringent criterion decreased our sample size, such safeguards are necessary to avoid analyzing data from participants who are randomly answering the questionnaire items in order to quickly complete the HIT. Moreover, the rates of usable data in the current study are comparable to those found by other researchers using the AMT platform (Buhrmester et al. 2011; Sprouse 2011). Thus, although AMT facilitates quick data collection, researchers must take steps to assure that the data used are from participants that carefully considered each item (e.g., minimum completion times; orderliness criterion based on the researcher’s previous experience).

Acknowledgments:

This work was funded by NIDA Grants R01 DA 024080, R01 DA 024080–02S1 (NIAAA), R01 DA 030241 and the Virginia Tech Carilion Research Institute. The authors have no conflict of interest. The authors would like to thank Patsy Marshall for assistance with manuscript preparation.

References

- Babor TF, Higgins-Biddle JC, Saunders JB, Monteiro MG (2001) The Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test: Guidelines for Use in Primary Care. World Health Organization, Geneva [Google Scholar]

- Baker F, Johnson MW, Bickel WK (2003) Delay discounting in current and never-before cigarette smokers: Similarities and differences across commodity, sign, and magnitude. J Abnorm Psychol 112: 382–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, MacKillop J, Epstein LH, Carr K, Mueller ET, Waltz TJ (2012a) The behavioral economics of reinforcement pathologies: Novel approaches to addictive disorders. In: Shaffer HJ (ed) APA Addiction Syndrome Handbook (APA Handbooks in Psychology and APA Reference Books). APA, pp 1968 [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Gatchalian KM (2011a) The behavioral economics and neuroeconomics of reinforcer pathologies: Implications for etiology and treatment of addiction. Curr Psychiatry Rep 13: 406–415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Koffarnus MN, Gatchalian KM (2012b) Excessive discounting of delayed reinforcers as a trans-disease process contributing to addiction and other disease-related vulnerabilities: Emerging evidence. Pharmacol Ther 134: 287–297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Jones BA, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Mancino M (2010) Hypothetical intertemporal choice and real economic behavior: Delay discounting predicts voucher redemptions during contingency-management procedures. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 18: 546–552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Landes RD, Christensen DR, Jackson L, Jones BA, Kurth-Nelson Z, Redish AD (2011b) Single- and cross-commodity discounting among cocaine addicts: The commodity and its temporal location determine discounting rate. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 217: 177–187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Marsch LA (2001) Toward a behavioral economic understanding of drug dependence: Delay discounting processes. Addiction 96: 73–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Odum AL, Madden GJ (1999) Impulsivity and cigarette smoking: Delay discounting in current, never, and ex-smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 146: 447–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJC (2009) Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: Fictive and real money gains and losses. J Neurosci 29: 8839–8846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Kowal BP, Gatchalian KM (2008) Cigarette smokers discount past and future rewards symmetrically and more than controls: Is discounting a measure of impulsivity? Drug Alcohol Depend 96: 256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C (2011c) Remember the Future: Working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biol Psychiatry 69: 260–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjork JM, Hommer DW, Grant SJ, Danube C (2004) Impulsivity in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients: Relation to control subjects and type 1-/type 2 like traits. Alcohol 34: 133–150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester M, Kwang T, Gosling SD (2011) Amazon’s mechanical turk: A new source of inexpensive, yet high-quality, data? Perspectives on Psychological Science 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Businelle MS, McVay MA, Kendzor D, Copeland A (2010) A comparison of delay discounting among smokers, substance abusers, and non-dependent controls. Drug Alcohol Depend 112: 247–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton SR, Yi R, Porter C, Carter AE, Bickel WK, Rachlin H (in press) Now for me, later for us? Effects of group context on temporal discounting. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtney KE, Arellano R, Barkley-Levenson E, Galvan A, Poldrack RA, Mackillop J, David Jentsch J, Ray LA (2011) The Relationship Between Measures of Impulsivity and Alcohol Misuse: An Integrative Structural Equation Modeling Approach. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dom G, D’haene P, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B (2006) Impulsivity in abstinent early- and late-onset alcoholics: Differences in self-report measures and a discounting task. Addiction 101: 50–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du W, Green L, Myerson J (2002) Cross-cultural comparisons of discounting delayed and probabilistic rewards. The Psychological Record 52: 479–492. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn JR, Schweitzer ME (2005) Feeling and believing: the influence of emotion on trust. J Pers Soc Psychol 88: 736–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallus S, Rosato V, Zuccaro P, Pacifici R, Colombo P, Manzari M, La Vecchia C (2011) Attitudes towards the extension of smoking restrictions to selected outdoor areas in Italy. Tob Control. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Fry AF, Myerson J (1994) Discounting of delayed rewards: a life-span comparison. Psychol Sci 5: 33–36. [Google Scholar]

- Green L, Myerson J, Lichtman D, Rosen S, Fry AF (1996) Temporal discounting in choice between delayed rewards: The role of age and income. Psychol Aging 11: 79–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gurtman MB (1992) Trust, distrust, and interpersonal problems: a circumplex analysis. J Pers Soc Psychol 62: 989–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaroni JL, Wright SM, Lerman C, Epstein LH (2004) Relationship between education and delay discounting in smokers. Addict Behav 29: 1171–1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK (2002) Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. J Exp Anal Behav 77: 129–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bickel WK, Baker F (2007) Moderate drug use and delay discounting: A comparison of heavy, light, and never smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 15: 187–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Bruner NR (2011) The Sexual Discounting Task: HIV risk behavior and the discounting of delayed sexual rewards in cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones B, Rachlin H (2006) Social discounting. Psychol Sci 17: 283–286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Marakovic NN (1996) Delay-discounting probabilistic rewards: rates decrease as amounts increase. Psychon Bull Rev 33: 100–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK (1999) Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug using controls. J Exp Psychol Gen 128: 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida KT, King-Casas B, Montague PR (2010) Neuroeconomic approaches to mental disorders. Neuron 67: 543–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kishida KT, Montague PR (2012) Imaging Models of Valuation During Social Interaction in Humans. Biol Psychiatry. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koffarnus MN, Jarmolowicz DP, Mueller ET, Bickel WK (under review) Changing discounting in light of the competing neurobehavioral decision systems theory J Exp Anal Behav. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lawyer SR, Williams SA, Prihodova T, Rollins JD, Lester AC (2010) Probability and delay discounting of hypothetical sexual outcomes. Behav Processes 84: 687–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin EY, Witten K, Casswell S, You RQ (2011) Neighbourhood matters: Perceptions of neighbourhood cohesiveness and associations with alcohol, cannabis and tobacco use. Drug Alcohol Rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL (2003) Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 11: 139–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden GJ, Raiff BR, Laforio CH, Begotka AM, Mueller AM, Hehli DJ, Wegener AA (2004) Delay disocounting of potentially real and hypothetical rewards: Il. Between-and within-subject comparison. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 12: 251–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur JE (1987) An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazur JE, Nevin JA, Rachlin H (eds) Quantitative analysis of behavior. Erlbaum, Hillsdale, NJ, pp 55–73 [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D’Esposito M, Boettiger CA (2005) Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 29: 2158–2169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell SH (1999) Measures of impulsivity in cigarette smokers and nonsmokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 146: 455–464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL (2011a) Delay discounting: Trait variable? Behavioral Processes 87: 1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL (2011b) Delay discounting: I’m a k, You’re a k. J Exp Anal Behav 96: 427–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Baumann AA, Rimington DD (2006) Discounting of delayed hypothetical money and food: effects of amount. Behav Processes 73: 278–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odum AL, Madden GJ, Bickel WK (2002) Discounting of delayed health gains and losses by current, never- and ex-smokers of cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res 4: 295–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petry NM (2001) Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 154: 243–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B (2006) A review of delay-discounting research with humans: Relations to drug use and gambling. Behav Pharmacol 17: 651–667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Karraker K, Horn K, Richards JB (2003) Delay and probability discounting as related to different stages of adolescent smoking and non-smoking. Behavioral Processes 64: 333–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Leraas K, Collins C, Melanko S (2009) Delay discounting by the children of smokers and nonsmokers. Drug Alcohol Depend 99: 350–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Richards JB, Horn K, Karraker K (2004) Delay discounting and probability discounting as related to cigarette smoking status in adults. Behavioral Processes 30: 35–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds B, Schiffbauer R (2004) Measuring state changes in human delay discounting: An experiential discounting task. Behav Processes 67: 343–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvanfard M, Ekhtiari H, Mokri A, Djavid GE, Kaviani H (2010) Psychological and behavioral traits in smokers and their relationship with nicotine dependence level. Arch Iran Med 13: 395–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotenberg KJ (1994) Loneliness and interpersonal trust. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 13: 152–173. [Google Scholar]

- Rotter JB (1967) A new scale for the measurement of interpersonal trust. J Pers 35: 651–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M (1993) Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO Collaborative Project on Early Detection of Persons with Harmful Alcohol Consumption--II. Addiction 88: 791–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sprouse J (2011) A validation of Amazon Mechanical Turk for the collection of acceptability judgments in linguistic theory. Behav Res Methods 43: 155–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stea JN, Hodgins DC, Lambert MJ (2011) Relations between delay discounting and low to moderate gambling, cannabis, and alcohol problems among university students. Behavioral Processes 88: 202–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweitzer MM, Donny EC, Dierker LC, Flory JD, Manuck SB (2008) Delay discounting and smoking: Association with the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence but not cigarettes smoked per day. Nicotine Tob Res 10: 1571–1575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vuchinich RE, Simpson CA (1998) Hyperbolic temporal discounting in social drinkers and problem drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 6: 292–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wackowski OA, Lewis MJ, Hrywna M (2011) Banning smoking in New Jersey casinos--a content analysis of the debate in print media. Subst Use Misuse 46: 882–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio Y, Higgins ST, Heil SH, McKerchar TL, Badger GJ, Skelly JM, Dantona RL (2011) Delay discounting is associated with treatment response among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 19: 243–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AM, Brown GD, Maltby J (2011) Social Norm Influences on Evaluations of the Risks Associated with Alcohol Consumption: Applying the Rank-Based Decision by Sampling Model to Health Judgments. Alcohol Alcohol. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi R, Gatchalian KM, Bickel WK (2006) Discounting of past outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol 14: 311–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]