Abstract

Lipid droplets (LDs) are ubiquitous organelles that facilitate neutral lipid storage in cells, including energy-dense triglycerides. They are found in all investigated metazoan embryos where they are thought to provide energy for development. Intriguingly, early embryos of diverse metazoan species asymmetrically allocate LDs amongst cellular lineages, a process which can involve massive intracellular redistribution of LDs. However, the biological reason for asymmetric lineage allocation is unknown. To address this issue, we utilize the Drosophila embryo where the cytoskeletal mechanisms that drive allocation are well characterized. We disrupt allocation by two different means: Loss of the LD protein Jabba results in LDs adhering inappropriately to glycogen granules; loss of Klar alters the activities of the microtubule motors that move LDs. Both mutants cause the same dramatic change in LD tissue inheritance, shifting allocation of the majority of LDs to the yolk cell instead of the incipient epithelium. Embryos with such mislocalized LDs do not fully consume their LDs and are delayed in hatching. Through use of a dPLIN2 mutant, which appropriately localizes a smaller pool of LDs, we find that failed LD transport and a smaller LD pool affect embryogenesis in a similar manner. Embryos of all three mutants display overlapping changes in their transcriptome and proteome, suggesting that lipid deprivation results in a shared embryonic response and a widespread change in metabolism. Excitingly, we find abundant changes related to redox homeostasis, with many proteins related to glutathione metabolism upregulated. LD deprived embryos have an increase in peroxidized lipids and rely on increased utilization of glutathione-related proteins for survival. Thus, embryos are apparently able to mount a beneficial response upon lipid stress, rewiring their metabolism to survive. In summary, we demonstrate that early embryos allocate LDs into specific lineages for subsequent optimal utilization, thus protecting against oxidative stress and ensuring punctual development.

Author summary

Embryos of diverse animal species sort their lipid droplets into specific cell lineages early in development. Here we prevent Drosophila embryo’s ability to undergo this asymmetric inheritance through two separate genetic perturbations. We then investigate the effects on subsequent embryogenesis, finding developmental delays and an inability to consume the mislocalized lipid droplets. We find a similar delay for embryos which receive fewer lipid droplets from their mothers. To understand how embryos respond to limited access to lipid droplets, we investigate the global transcriptome and proteome in the mutants and find alterations to the expression of hundreds of metabolism genes, including for enzymes that transport sugar across cell membranes, break down fat, or protect against oxidative stress. We test if the upregulated genes have beneficial functions for lipid-deprived embryos. We find that zygotic knock down of the upregulated oxidative stress response genes GSS and GSTT4 as well as the lipase ATGL lowers hatching success in LD-deprived genetic backgrounds, but not wild type. In summary, we find that early lipid droplet lineage sorting sets the stage for metabolic success in subsequent embryogenesis.

Introduction

Lipid droplets (LDs) are ubiquitous organelles that store cells’ neutral lipid reserves [1,2]. They store crucial lipids, including triglycerides, sterol esters, and other fat-soluble molecules, and are integral to energy homeostasis, lipid signaling processes, and membrane synthesis. They are also abundant in the embryos of many metazoans, including Drosophila, mud snails, Xenopus, zebrafish, and mice, where they presumably fuel embryogenesis [3,4,5,6]. Intriguingly, in many species, embryos allocate their LD reserves asymmetrically across lineages. Whether this asymmetric inheritance could benefit embryonic development or be an epiphenomenon without consequence for the embryo is unknown. Previous studies have relied on aggregate biochemical assays that could not address the role of spatial specialization in embryonic metabolism. Thus, the role(s) of LD allocation in the embryonic body plan remain to be characterized.

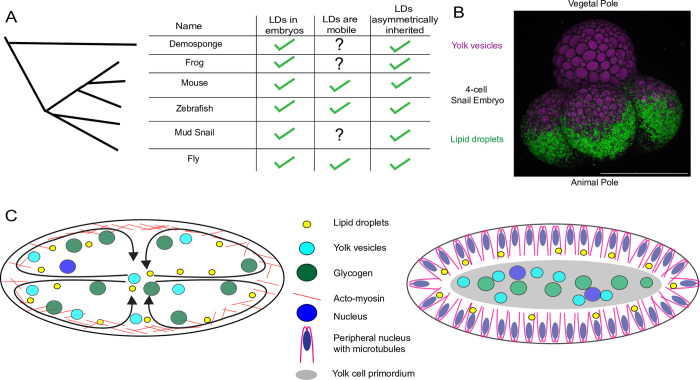

Asymmetric inheritance of LDs is observed across widely divergent species. For example, in mouse [4,7], LDs become motile after fertilization [7] and just prior to implantation are present at different densities in the embryo proper vs the trophoblast (zygote-derived support cells) [4]. In Xenopus [3] and zebrafish [8], LDs are deposited into the yolk sac. Over the course of embryogenesis, zebrafish embryos then transport these stored lipids to the periphery, first by using acto-myosin to transport entire LDs to neighboring cells that remain connected to the yolk via intracellular bridges [8], then in older embryos by packaging LD-derived lipids into lipoprotein particles. These particles are secreted into the bloodstream and reach distant tissues via the vasculature [9]. This pattern of unequal allocation is not unique to deuterostomes, but also occurs among species belonging to the other two major clades of Bilateria, Ecdysozoa and Spiralia. During cellularization in Drosophila embryos (an Ecdysozoan), LDs are allocated predominately to the incipient peripheral epithelium, while they are depleted from the interior yolk cell [10,11]. In mud snails (Tritia formerly Ilyanassa, a Spiralian), LDs are differentially allocated by the 4-Cell Stage (Fig 1B): the cells at the animal pole receive the LDs, while the cell at the vegetal pole receives most of the yolk protein vesicles (consistent with LD distribution in the zygote [12]). Uneven distribution of LDs during embryogenesis has even been reported in a demosponge (Poriferan) [13], where LDs are inherited by the ciliated lineage. Thus, major metazoan embryo model systems display lineage specific LD inheritance (Fig 1A).

Fig 1. Metazoan embryos asymmetrically allocate their LDs early in embryogenesis.

A) A cartooned phylogeny of the metazoan embryonic systems where LDs have been shown to be asymmetrically inherited early in embryogenesis. The left column indicates that LDs are present at laying/ovulation in the species. The right column indicates whether LDs are asymmetrically inherited in the system. The center column indicates whether the LDs are also known to be moving along the cytoskeleton. Citations are Demosponge (Mycale laevis) [13], Frog (Xenopus laevis) [3], Mouse (Mus musculus) [4,7], zebrafish (Danio rerio) [8], fly (Drosophila melanogaster) [10], and the mud snail data is from this paper and shown in panel B. B) Tritia obsolete (an ocean snail with the common name ‘mud snail’) embryo at the 4-cell Stage with the vegetal pole at the top and animal pole at the bottom. LDs are labeled with BODIPY493/503 in green and yolk-protein vesicles are imaged with intrinsic autofluorescence in magenta. Note that only the cells at the animal pole have inherited LDs. Scale bar 100 μm. C) Cartoons of the modes of lipid droplet motion in syncytial Drosophila embryos. On the left, a syncytial-cleavage stage embryo (Stage 1–3) undergoes bulk cytoplasmic streaming; actomyosin driven contractions at the embryonic cortex circulate the contents including LDs and other nutrient storage structures. On the right, a stage 5 embryos undergoes a bulk cytokinetic event; LDs interact with the peripheral microtubules and are transported along them into the forming cells. Note that this separates LDs (in the periphery) away from the centrally localized glycogen and yolk-protein vesicles in the embryonic center/yolk cell.

The mechanism of unequal allocation is best understood in Drosophila. Here, the embryo develops initially as a syncytium progressing through several synchronous rounds of nuclear division. The embryo then undergoes a bulk cytokinetic event (cellularization), which generates a peripheral epithelium and an interior yolk cell. During this period, LDs redistribute from a homogeneous distribution to a peripheral enrichment. This redistribution depends first on bulk flow [11] as actomyosin at the cortex circulates the embryo’s cytoplasm in synchrony with the nuclear divisions (Fig 1C, left). Second, before and during cellularization, LDs move bidirectionally along peripheral microtubules, via a motor complex that includes cytoplasmic dynein and kinesin-1(Fig 1C, right) [14,15,16,17,18]. This LD transport ensures that most LDs are deposited into the peripheral cell lineages [10]. While in other animal species the mechanisms of asymmetric LD inheritance remain unknown, it seems likely that cytoskeletal-mediated transport plays a crucial role, as LD motility has also been observed in mouse [7] and zebrafish [8] embryos.

To investigate why LDs in Drosophila embryos are predominately allocated to the peripheral epithelium, we disrupted LD transport by genetically abolishing two LD proteins, Jabba [11] and Klar [17]. In the absence of Jabba, LDs physically interact with glycogen granules and are inappropriately sorted with them to the yolk cell [11]. In the absence of the motor cofactor Klar, the relative activities of kinesin-1 and cytoplasmic dynein on LDs are altered, leading to LDs being transported to the yolk cell. Although protein null alleles of Jabba and Klar lead to misallocation of LDs from the peripheral epithelium to the yolk cell, they do so by different mechanisms, and thus we expect that shared organismal phenotypes of these mutants are attributable to their shared output of LD allocation to the wrong lineage (the yolk cell).

We find that compared to wild-type embryos both mutants have slower and incomplete LD consumption and show significantly delayed embryo hatching. We observe a similar hatching delay in embryos mutant for the LD protein dPlin2. Because dPlin2-/- embryos have normal LD distribution but reduced LD numbers, we conclude that the hatching delay results from reduced access to LDs in the peripheral tissues. Global gene expression analysis indeed identifies a shared set of genes altered in all three mutants, suggesting that embryos actively respond to LD deprivation. These genes span a wide range of categories, including sugar and lipid metabolism, developmental signaling pathways, and glutathione metabolism. Zygotic RNAi targeting the lipase ATGL/Bmm, Glutathione synthase, and Glutathione S-transferase T4 reduce viability in LD mutant backgrounds but not in wild type. Further, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, and dPLIN2-/- embryos all have significantly more peroxidated lipids than wild-type counterparts. We conclude that asymmetric lineage inheritance of LDs early in embryogenesis bolsters subsequent utilization by those lineages, protecting against oxidative stress and starvation.

Results

Jabba and Klar ensure LD transport through two disparate means

Drosophila mothers provide their embryos with neutral lipids stored in LDs, and carbohydrates stored in glycogen granules (GGs) [19]. Under normal conditions, these storage structures do not interact with each other and are sorted into two distinct tissues during cellularization [11], LDs into the peripheral cells and GGs into the interior yolk cell. Previous work revealed that mutations in the LD proteins Klar and Jabba lead to inappropriate deposition of most LDs into the yolk cell. In the absence of the motor cofactor Klar, the movement of individual LDs along microtubules is dramatically reduced and net transport is inward, towards the plus ends of microtubules [10,16,17]; a similar phenotype is observed with hypomorphic dynein alleles [10,16,17]. In the absence of Jabba, LDs stick inappropriately to the surface of GGs, generating enormous composite structures that drag the LDs into the embryonic interior [11].

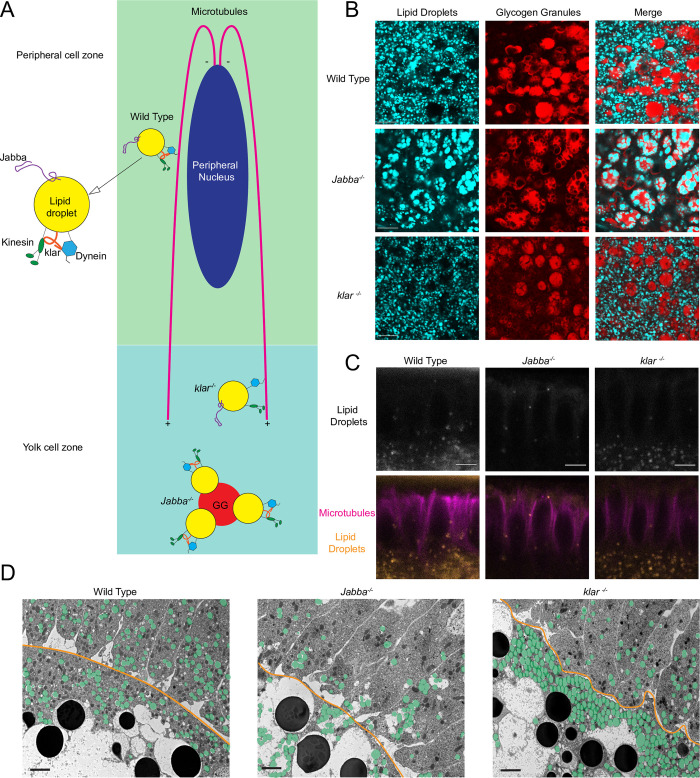

To determine if these two mutations indeed disrupt LD allocation in distinct ways, we tested for LD and GG association in klar mutants (allele referred to as klar-/-, see methods for details) and tested LD movement in Jabba mutants. We first co-labeled LDs and GGs in fixed embryos, using the neutral lipid dye BODIPY and fluorescent Periodic Acid Schiff (fPAS) staining, respectively. Jabba-/- embryos displayed a dramatic redistribution of LDs to the surface of GGs, forming LD rings on the surface of GGs (Fig 2B). No such association was present in the klar-/- and wild-type embryos (Fig 2B), confirming previous results [11]. Next, we co-microinjected dyes to label LDs and microtubules into living embryos [20] and monitored LD motion during Stage 5 (cellularization) through timelapse imaging (S1–S3 Videos). In wild-type embryos, LDs were highly mobile and switched between long stretches of anterograde kinesin-1-mediated motion (away from the centrosome) and retrograde, dynein-mediated motion (towards the centrosome) (S1 Video). In the klar-/- embryos, LDs were slower and covered much shorter distances, as previously observed (S3 Video) [17]. In Jabba-/-, we are imaging the small minority of the LDs (~8% of the total) not bound to GGs. This LD population was highly mobile, like in wild type (S2 Video). Further, the gross LD distribution in the embryo periphery was different (Fig 2C). Wild type has a large population of LDs located basal to the nuclei (i.e., towards the embryo center) and a smaller, mobile population at the level of the nuclei or apical to them (i.e., towards the plasma membrane). In klar-/-, we see mostly the former population and in Jabba-/- the latter.

Fig 2. Jabba and Klar are important for peripheral LD allocation through two separate means.

A) Model for how wild-type, klar-/-, and Jabba-/- LDs interact with peripheral microtubules during cellularization. The wild-type LD moves towards the minus end of the microtubule, taking it to the periphery. The klar-/- LD can bind microtubules, but cannot move properly once bound, leaving it stranded at the plus end in the presumptive yolk cell. The Jabba-/- LDs are entrapped in glycogen granules and dragged into the embryonic interior with the glycogen. B) Newly laid wild type, Jabba-/-, and klar-/- embryos stained with BODIPY493/503 (cyan) to label LDs and fPAS (red) to label glycogen granules. Note the strong association of LDs with glycogen granules in Jabba-/-, but not wild type or klar-/-. Scale bars are 10 μm. C) Frames of movies from live wild type, Jabba-/-, and klar-/- embryos at cellularization, with LDs labeled with BODIPY493/503 and microtubules labeled with SPY-tubulin. The field-of-view has ~5 blastoderm nuclei in the center of the image with the eggshell at the top and incipient yolk cell out of frame at the bottom of the image. Note that the Jabba-/- genotype’s LD distribution is different from both wild type and klar-/-. Further, the few Jabba-/- LDs that are free from glycogen have no issue migrating to the minus end of microtubules. Scale bars are 5 μm. D) TEMs of wild type, Jabba-/-, and klar-/- embryos after completion of cellularization. LDs are false colored in green. Scale bars are 2 μm. The area where the blastoderm cells meets the yolk cell is shown outlined in orange. Note that this view shows only the bottom ~1/6th of the peripheral cells but all the yolk cell cytoplasm that contains LDs (excluding Jabba-/- where LDs are present much deeper in the yolk cell). Note that LD distributions are different in all three genotypes, further supporting different means of arriving at the phenotypes, but that both Jabba-/- and klar-/- have an excess of LDs in the yolk cell.

We also examined LD distribution in newly cellularized embryos by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), focusing on the boundary between peripheral cells and the interior yolk cell (Fig 2D). In wild type, the density of LDs was comparable in the peripheral epithelium and the outskirts of the yolk cell. In Jabba mutants, the LD density in the yolk cell was much higher than in the periphery (~4x), with LDs not only in the peripheral yolk-cell cytoplasm, but also occupying the more central areas typically occupied only by glycogen and yolk vesicles (Fig 2D) [11]. In klar-/- mutants, there is roughly 3x the LD density in the yolk cell, with most of those LDs occupying the peripheral cytoplasm seemingly queued just beneath the completed cellularization boundary (Fig 2D, boundary in orange).

Thus, even though Jabba and klar mutants both display misallocation of LDs to the yolk cell, they differ in LD-GG association, LD motility, and the detailed spatial distribution of LDs in the yolk cell. We therefore conclude that they misallocate LDs through different mechanisms.

Jabba-/- and klar-/- mutants are delayed in consuming their LDs

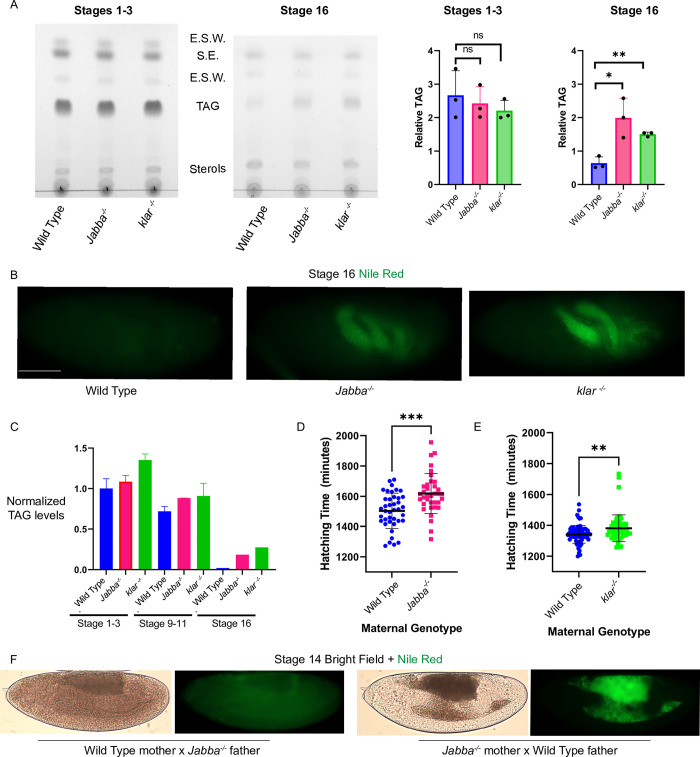

To address the fate of the mislocalized LDs in Jabba and klar-/- mutants, we performed neutral-lipid thin layer chromatography (TLC) on extracts from newly laid and Stage 16 embryos (Fig 3A). In the newly laid embryos, the levels of all lipid classes detected were comparable: sterol esters (LDs) and TAG (LDs) as well as those of membrane sterols and eggshell waxes (Fig 3A). At the later timepoint, TAG levels were reduced in all genotypes, consistent with its previously described developmental turnover [5,6]. However, TAG levels were significantly higher in Jabba-/- and klar-/- (using membrane sterols as a reference) compared to wild type while the other lipid species were more comparable (Fig 3A). This result indicates that turnover of the LD-stored TAG is specifically compromised in the mutants.

Fig 3. In Jabba-/- and klar-/-embryos, misallocated LDs are not consumed appropriately, and embryogenesis is protracted.

A) Neutral lipid TLCs of wild type, Jabba-/-, and klar-/- embryos at a young (prior to the syncytial blastoderm) and older stage (~2/3rds through embryogenesis). Quantification of the LD-stored TAG, controlled against membrane sterols and protein concentration, shows embryos start with similar levels. However, Jabba-/- and klar-/- have significant TAG persistence at Stage 16. E.S.W. is eggshell wax. S.E. is sterol esters. TAG is triglycerides. N is three replicates of 100 embryos each per genotype. B) Nile Red whole mount staining of Stage 16 embryos shows the persistent LD population in Jabba-/- and klar-/- in the yolk cell. Scale bar 100 μm. C) Enzymatic TAG measurements for wild type, Jabba-/-, and klar-/- embryos at an early, mid, and late embryogenesis timepoint. TAG persists in Jabba-/-, and klar-/- embryos. TAG measurements were first normalized to protein levels in the sample, and then to the average reading from the Stage 1–3 wild-type samples. N is three replicates of 100 embryos each per genotype. D) Hatching assay data for a reciprocal cross setup for wild type and Jabba-/- genotypes. Blue is wild-type mothers x Jabba-/- fathers and magenta is Jabba-/- mothers x wild-type fathers. E) Reciprocal cross setup for wild type and klar-/- genotypes. Blue is wild-type mothers x klar-/- fathers and green is klar-/- mothers x wild-type fathers. D,E) The hatching assays were performed at 22°C for Jabba-/- and 25°C for klar-/-; Jabba-/- was done at a lower temperature as embryonic viability in this genotype drops at 25° C [31]. There are at least 40 embryos per genotype. F) Stage 14 embryos stained with Nile Red and imaged from the crosses used in D, demonstrating that the Jabba-/- LD misallocation is a result of the maternal genotype. A,D) Significance was determined with unpaired Student’s t-tests in GraphPad Prism, ns is P > 0.05, * is P ≤ 0.05, ** is P ≤ 0.01, *** is P ≤ 0.001. Error bars represent standard deviation.

To determine the fate of the mis-allocated LDs, we performed whole-mount neutral lipid staining which revealed abundant signal in Stage 16 Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos, agreeing with our previously shown LD persistence in newly hatched Jabba-/- L1 larva [11]; in contrast, wild type embryos showed barely any signal throughout (Fig 3B). Thus, the embryos start with similar LD levels, but LDs mis-allocated to the yolk cell persist in Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos.

As an independent approach, we measured TAG levels biochemically. Embryos of three different ages were lysed, and TAG was detected enzymatically (Fig 3C). In the first 90 minutes of embryogenesis (Stages 1–3), wild type, Jabba-/- and klar-/- had similar levels of TAG, showing these genotypes were laid with comparable amounts of TAG. At 8 hours (Stages 8–10), TAG levels were still similar, though wild type started to pull ahead in TAG consumption (Fig 3C). Finally, at ~15 hours into development (Stage 16), wild-type TAG levels had dipped to the limit of detection, unlike for Jabba-/- and klar-/- mutants (Fig 3C). The pattern in the wild type is consistent with the previously described developmental turnover of triglycerides [5,6]. As lack of Jabba and Klar causes LD misallocation by different means, it seems likely that it is the misallocation itself that results in compromised LD turnover.

Embryogenesis is protracted in Jabba-/- and klar-/- mutants

Because embryos mutant for either Jabba or Klar can give rise to fertile adults [17,21], proper turnover of the embryo’s entire LD population is apparently not required for viability. However, disruption of embryogenesis (e.g., by manipulating environmental parameters such as temperature and oxygen levels) can dramatically affect the duration of embryogenesis without reducing hatching success [22,23]. We therefore assessed how long embryos of various genotypes take until they hatch into larvae, as a more sensitive measure of compromised embryogenesis. Control- and experimental-genotype embryos were collected in parallel for ~1hr and visually confirmed to be in the appropriate stage (e.g., prior to cellularization); then embryos from each genotype were transferred onto the same assay plate and arranged into rows so that they fit into the field of view of our camera setup. The plates with embryos were aged overnight and then videorecorded to observe hatching events.

Initial experiments suggested that embryos from strains mutant for Jabba or Klar display hatching delays. Mislocalization of LDs in embryos is due to the lack of Klar [17] or Jabba (Fig 3F) in the mother, yet Jabba and Klar are expressed both during oogenesis and embryogenesis [24] (FlyBase, see Materials and Methods for citation details). It is therefore possible that altered timing of embryogenesis results from new expression of these proteins in the zygote and would thus be unrelated to LD mislocalization. For example, it is known that proper development of the embryonic salivary gland requires zygotically expressed Klar [25]. To circumvent this issue, we compared hatching times between embryos from wild-type mothers and LD mutant fathers (Jabba-/- or klar-/-) to embryos from reciprocal crosses. In this comparison, the embryos have the same zygotic genotype with respect to Jabba and klar but differ in LD allocation. The reciprocal crosses were performed at different temperatures, as Jabba-/- viability drops at 25°C. Intriguingly, embryos from LD mutant mothers took significantly longer to hatch than their counterparts from wild-type mothers (Fig 3D for Jabba-/-, and 3E for klar-/-), with embryos from Jabba-/- mutant mothers taking 90mins longer to hatch (Fig 3C), and embryos from klar-/- mothers taking 40mins longer (Fig 3E) to hatch than their relevant controls. Thus, embryos which mislocalize their LDs and fail to fully consume them display prolonged embryogenesis.

Embryos with diminished LD numbers are also delayed in hatching

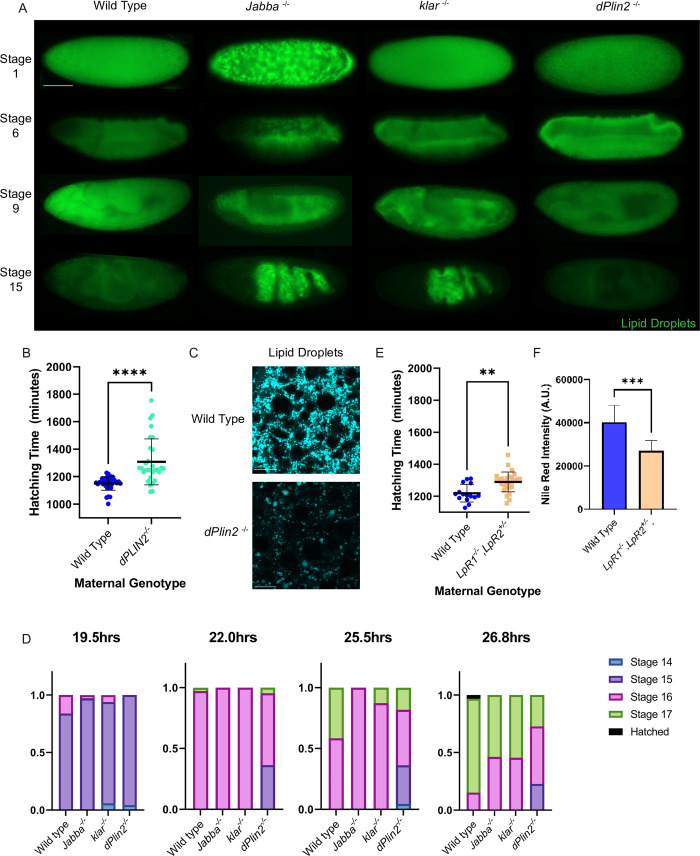

Our results from the two preceding sections suggest that the hatching delay is caused either by too few LDs in the periphery or too many LDs in the yolk cell. For example, too few LDs might create a ‘starvation’ state in peripheral cells or yolk-cell lipid overload might result in metabolic stress. To distinguish between these possibilities, we analyzed mutants with reduced maternal LD loading. Embryos lacking the LD-resident perilipin protein dPLIN2/LSD-2 receive less triglyceride from their mothers [26] but contain LDs of normal size [27], suggesting that they contain fewer LDs. Indeed, neutral lipid staining (BODIPY) in newly laid embryos reveals lower LD density in dPLIN2-/- embryos (Fig 4C). We then stained wild type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, and dPLIN2-/- embryos for neutral lipids and compared them at various developmental stages (Fig 4A). In newly laid embryos, LDs were homogeneously distributed in wild type, klar-/-, and dPLIN2-/-, while in Jabba-/- LDs displayed a patchy distribution, consistent with redistribution to the surface of GGs (Fig 4A). At Stage 6, wild type and dPLIN2-/- embryos’ LD localization remained indistinguishable, while in Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos LDs were mostly localized to the yolk cell (Fig 4A). In Stages 9 and 15, wild-type and dPLIN2-/- embryos displayed the same global LD distribution, with overall diminished staining intensity in dPLIN2-/- compared to similarly aged wild-type embryos (Fig 4A). At the same stages, Jabba-/- and klar-/- LDs were predominantly localized to the yolk cell, with minor signal in the periphery in Stage 9, but not Stage 15, suggesting that the appropriately localized LD population is quickly consumed while the yolk cell LDs are retained (Fig 4A). Thus, dPLIN2-/- mutants appropriately localize a smaller pool of LDs, i.e., they represent embryos with fewer LDs in the periphery, but without an excess of LDs in the yolk cell.

Fig 4. Mutants with defective maternal LD loading have hatching delays.

A) Whole mount, Nile Red stained embryos (LD-mutants and wild type) at different timepoints. dPLIN2-/- embryos appropriately localize a smaller pool of LDs. Scale bar 100 μm. B) Hatching assay for a reciprocal cross setup for wild type and dPLIN2-/- genotypes. Blue is wild-type mothers x dPLIN2-/- fathers and turquoise is dPLIN2-/- mothers x wild-type fathers. dPLIN2-/- is delayed like Jabba-/- and klar-/-. C) Newly laid,fixed-embryo, LD-staining with BODIPY. Scale bar 5 μm D) Shows the stage progression of embryos synchronized at Stage 14/dorsal closure. Note the slight onset of a delay, suggesting that the bulk of the hatching delay seen in mutants occurs during Stage 17/hatching/when the embryo is ramming its head into the eggshell. E) Hatching assay using a reciprocal cross setup for wild type and LPR1-/-,LPR2+/- genotypes. Blue is wild-type mothers x LPR1-/- LPR2+/- fathers and beige is LPR1-/- LPR2+/- mothers x wild-type fathers. Note that 1 copy of LPR2 is required for completion of oogenesis, making the zygotic genotypes heterogeneous in this cross. Embryos from LPR1-/- LPR2+/- mothers are delayed like Jabba-/- and klar-/- dPLIN2-/-. B,D,E) Each genotype starts with at least 25 embryos. F) Stage 1–4 embryos of the respective genotype stained with Nile red and quantified using FIJI. N is 14 embryos for wild type and nine for LPR1-/- LPR2+/-. B,E,F) Significance was determined with unpaired Student’s t-tests in GraphPad Prism, ns is P > 0.05, * is P ≤ 0.05, ** is P ≤ 0.01, *** is P ≤ 0.001, and **** is P ≤ 0.0001. Error bars represent standard deviation.

We performed reciprocal crosses of dPLIN2-/- and wild-type adults, and assayed the time taken for the progeny to hatch (Fig 4B). The embryos of dPLIN2-/- mothers took on average 120min longer to hatch than embryos from wild-type mothers. Closer inspection of the hatching data revealed an expanded tail for lipid-deprived embryos (Jabba-/-, klar-/-, or dPLIN2-/-): the 4th quartile hatchers were very delayed, occasionally exceeding 30hrs (~40% longer than would be expected at 25°C [22]). To understand at which stage the hatching delay occurs, we collected embryos laid during a 50-minute window and allowed them to develop for 17hrs at 22°C and then embryos at Stage 14 were transferred to a new plate. This is several hours after the proposed onset of TAG metabolism [28]. Embryos were then examined at four timepoints for their progression through the remaining stages, as judged by morphological criteria, (Fig 4D). At 19.5hrs post laying, there were no obvious differences between wild-type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, and dPLIN2-/- embryos. The wild-type embryos pulled slightly ahead through the 22hr, 24.5hr, and 26.8hr timepoints (Fig 4D). The modest differences in progressing from Stage 15 to 16, and 16 to 17 do not fully explain the observed hatching delays, suggesting that most of the delay occurs at the Stage 17 to hatching transition. This is the stage when the embryo begins active skeletal muscle movements that generate coordinated, whole-body contractions that eventually break the eggshell. These contractions start at the posterior, move anteriorly, and end with the mouthparts engaging with the eggshell. All three LD-deprived embryos spend more time in this ‘hatching contraction’ period. S4 Video shows a reciprocal cross between wild type and klar-/ -wherein two out of four klar-/- embryos spend several hours (5+) more trying to hatch than counterparts from wild-type mothers. This observation is also true for embryos from Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/-, with dPLIN2-/- being particularly severe (~1/3 of embryos attempt but fail to hatch). Thus, loss of Jabba, Klar, or dPLIN2 seems to converge on the same developmental responses, likely in Stage 17 (Fig 4D).

Finally, we used mothers with reduced levels of the lipoprotein receptors LpR1 and LpR2. During oogenesis, these receptors facilitate the uptake of extracellular lipids which are used to generate the vast majority of the LDs present in oocytes [29]. Thus, LpR1 and LpR2 are not LD proteins themselves, but allow us to manipulate how many LDs embryos inherit. Complete loss of the LpRs derails oogenesis, so we combined an allele lacking both LpR1 and LpR2 [29] in trans with one lacking LpR1 [29] (i.e., 0x LpR1 and 1x LpR2). This 0x LpR1 and 1x LpR2 genotype has ~70% of LDs deposited into wild type embryos [29]. We then reciprocally crossed males and females of this genotype to wild type and performed a hatching assay. In these crosses not all embryos have the same zygotic genotype because one parent is not homozygous, but the reciprocal crosses generate embryos of the same genotypes with respect to LpR1 and LpR2. The embryos from the LD-deprived LpR1 and LpR2 deficient mothers were delayed relative to the controls, by 70 minutes (Fig 4E). Thus, embryos with reduced maternal LD loading take longer to hatch than embryos from wild-type mothers, like embryos with mislocalized LDs (Jabba-/- and klar-/-). These results show four independent LD mutations converge on a developmental delay.

A core set of genes responds to loss of access to LDs

We next sought to determine if the embryo’s lipid-deprived state results in changes to its transcriptome. It is conceivable that lack of maternal Klar, Jabba, or dPLIN2 affect embryonic gene expression by multiple mechanisms in addition to lipid deprivation; for example, Klar is known to be important for proper localization of the posterior determinant Oskar in the early embryo [30], and Jabba controls nuclear levels of the histone H2Av before cellularization [31]. However, we reason that transcriptional responses shared between embryos from mothers mutant for Klar, Jabba, or dPLIN2 are most likely due to lipid deprivation, especially since mutations in the three proteins lead to such deprivation by distinct mechanisms.

We therefore isolated total RNA and enriched for mRNA from Stage 15 embryos (phenotypes cartooned in Fig 5A), which is roughly 2/3s of the way through embryogenesis (shown in Fig 4A) and several hours post the reported onset of fat consumption [28]. The embryos were collected from four maternal genotypes (wild type, klar-/-, Jabba-/-, or dPLIN2-/-), crossed to the same paternal genotype (wild-type, OrR). Thus, all these embryos shared about half of their zygotic genome, with the varying lipid deprivation phenotypes resulting from the maternal genotypes.

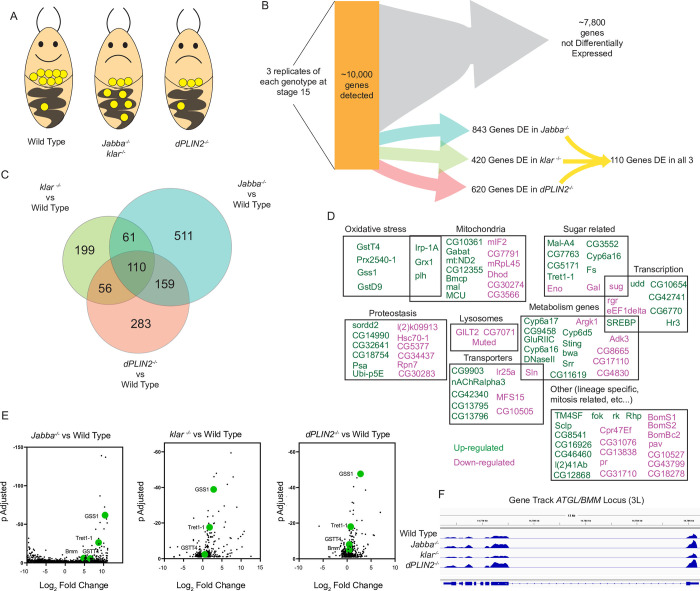

Fig 5. LD-deprived embryos have a shared transcriptional response.

A) Cartoon showing the wild-type LD distribution, the LD-transport mutant distribution, and the maternal loading mutants’ distribution. B) The number of genes detected in our mRNAseq analysis and the numbers of differentially expressed genes in the three mutants. N is three replicates of three embryos per genotype. C) A Venn diagram showing shared differentially expressed genes in each of the three mutants. D) Subjective binning of each of the 110 shared differentially expressed, protein-coding genes based on the FlyBase annotations. The color coding is done by whether it is upregulated (green) or downregulated (magenta) in all three mutants. E) Volcano plots for the differentially expressed genes in the three mutants’ comparisons. Genes which are investigated in later figures are shown with enlarged, green symbols and labeled. Note that the scale of the y-axis for the Jabba-/- comparison’s is different to fit the data. F) IGV tracks for 1 replicate of wild type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, and dPLIN2-/- showing expression levels of the ATGL/Bmm locus on the 3rd chromosome.

We then analyzed the global transcriptome by RNA-sequencing. Triplicate measures of each genotype were assembled into estimated read counts; then each mutant was independently compared to wild type to identify those genes that are differentially expressed (significantly higher or lower levels of RNA were found in the mutants relative to wild type). We found 810 such genes in Jabba-/-, 420 in klar-/-, and 620 in dPLIN2-/- (Fig 5E and S1, S2, S3, S4, S5, S6, S7, and S8 Tables). Remarkably, 110 genes changed in the same manner (either up or down) in all 3 mutants (Fig 5C); these genes thus likely represent a core set whose expression is altered in response to LD duress (Fig 5B). Our findings suggest that lipid-deprived embryos mount an active transcriptional response.

These genes fit into a diverse set of processes and to make them more accessible we subjectively categorized them based on their functional annotations (FlyBase, Fig 5D). The categories included oxidative stress, mitochondrial function, metabolism, sugar responsive, transcriptional regulators, membrane transporters, proteostasis, and a ‘other’ category that includes many genes involved in mitosis and lineage acquisition. Fig 5F shows individual IGV tracks for a gene of interest, ATGL/Bmm, which is significantly upregulated in Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/-. Intriguingly, we identified 68 genes consistently upregulated in all the mutant conditions (candidates of interest shown with green symbols Fig 5E), which might suggest that they are beneficial for managing the LD deprived state.

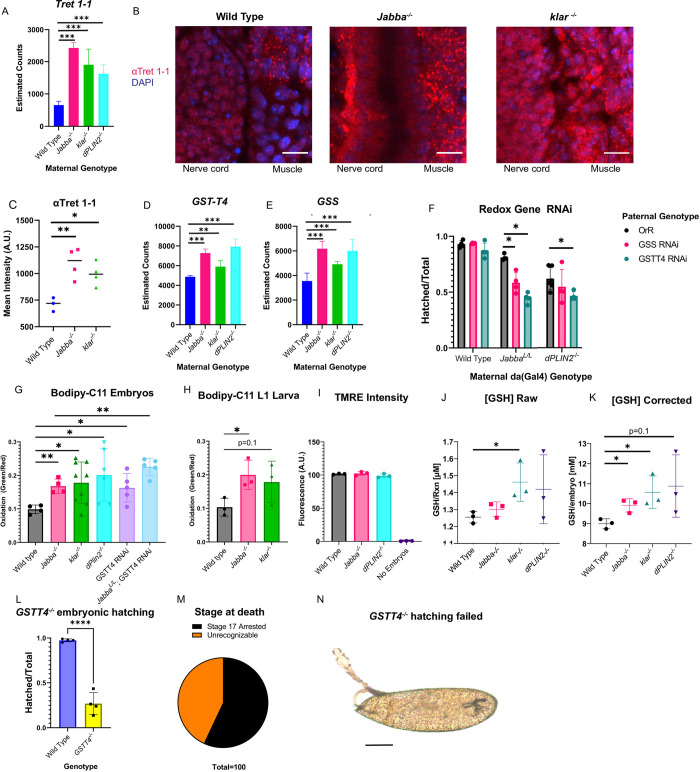

LD-deprived embryos have large alterations to their metabolic proteome

Uncovering the biological consequences of this transcriptional response is complicated by the fact that the mutant embryos also display dramatic changes in mRNAs for genes involved in proteostasis. Alterations to protein turnover pathways might lead to additional changes not captured in the RNA seq data or counteract the observed mRNA level changes. Prior to conducting a proteome-wide analysis (Fig 6), we took advantage of the fact that for one of our candidates, the trehalose transporter Tret 1–1, an antibody exists that has been verified for immunostaining [32]. Tret 1–1 is an essential sugar transporter in Drosophila [32,33], and our RNA-seq data show upregulation in our three mutants (Fig 7A). We therefore fixed embryos and stained them with an antibody against Tret 1–1 (targeting the PA isoform). To assess global Tret 1–1 levels, we acquired z-stacks encompassing the entirety of Stage 15 embryos and quantified the mean intensity value of the Tret 1–1 signal across the entire volume. Consistent with our RNA-seq data, there was a global increase in protein levels in both klar-/- and Jabba-/- relative to wild type (Fig 7C). Similar changes were observed for individual tissues: Tret 1-1-PA signal increased in Jabba-/- and klar-/- in the developing nerve cord and associated developing muscle in Stage 14 embryos (Fig 7B). Thus, for this candidate, upregulation of its mRNA is also reflected in a dramatic change in protein levels.

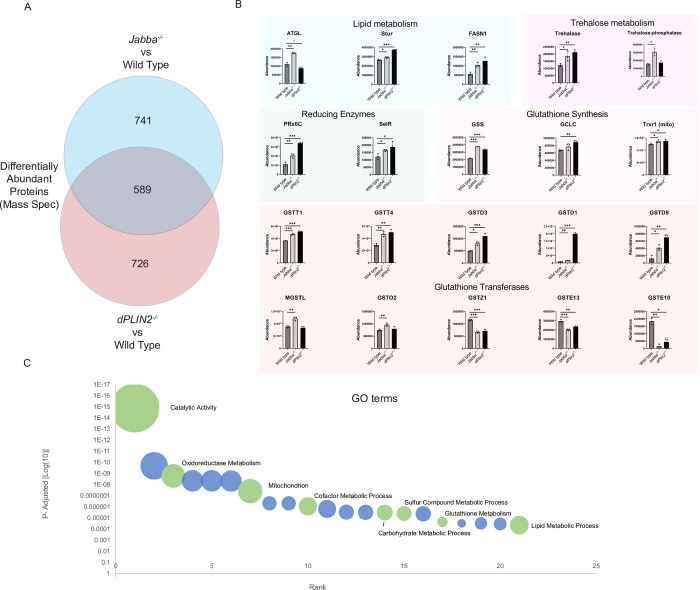

Fig 6. LD deprived embryos (Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- mutants) have changes in protein levels for many proteins, including those involved in lipid metabolism, trehalose metabolism, and redox metabolism.

A) Venn diagram showing overlapping and nonoverlapping differentially expressed genes in the Jabba-/- vs wild type comparison compared to the dPLIN2-/- vs wild type comparison, based on the mass spec analysis. B) Selected gene-products from mass spec (LC-MS-MS) analysis of Stage 15 wild type, Jabba-/-, and dPLIN2-/- embryos. The Y-axis shows normalized abundance reads. Background color indicates the category the genes are binned within. For ATGL, the black asterisks indicate a significant increase relative to wild type, while the grey indicates a significant decrease. C) The top 21 significant GO terms based on proteins which are differentially abundant in both Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- embryos. They are ranked in order of significance. The size is scaled to the number of genes matching the term. Blue bubbles are unlabeled while the green bubbles are labeled and referred to in the main text.

Fig 7. LD-deprived embryos have increased levels of the sugar transporter Tret1-1 and of lipid peroxidation as well as changes to glutathione metabolism.

A) Relative levels of Trehalose Transporter 1-1/Tret1-1 mRNA in the respective genotypes (Wild type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, dPLIN2-/-), based on RNA seq analysis. B) Immunofluorescence staining of Tret1-1 in Stage 14 embryos at the developing nerve cord: muscle junction. Scale bars 10 μm. C) Quantification of Tret1-1 staining intensity in z-stacks encompassing entire Stage 14 embryos. Images captured using spinning disc confocal microscopy. N is three embryos for wild type and four for Jabba-/- and klar-/-. D) Relative levels of Glutathione Transferase-Theta 4/GSTT4 mRNA in the respective genotypes (Wild type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, dPLIN2-/-) based on RNA seq analysis. E) Relative levels of Glutathione Synthase (GSS) mRNA in the respective genotypes (Wild type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, dPLIN2-/-) based on RNA seq analysis. Note we are pooling reads for the recently/tandemly duplicated GSS1 and GSS2 loci [36]. F) Zygotic RNAi (UAS) for GSTT4 and GSS (targets both GSS1 and GSS2) driven by da-Gal4. Note the phenotypes are mild, but a large supply of GSS protein is supplied by the mother which is unaffected by our RNAi and several other GSTT family members are expressed in the embryo (GSTT1 and GSTT2). N is roughly 100 embryos scored on four different days from at least two sets of crosses per genotype. G) Fluorescence readings from a BODIPY C11 lipid-peroxidation assay in pooled Stage 14–16 embryo homogenates. Data is shown as green (oxidized) fluorescence divided by the red (reduced) fluorescence. N is four replicates for wild type and Jabba-/-, nine for klar, six for dPLIN2, and five for GSTT4 RNA and JabbaL/L;GSTT4 RNAi of 10 embryos per genotype. H) Homogenates of L1 larvae which have hatched <2hrs prior assayed for BODIPY C11 peroxidation. LD-mutant L1 larva carry their oxidative burden post hatching. N is three replicates of 10 L1 larva per genotype I) TMRE was used to assess the mitochondrial inner membrane potential in Stage 14–16 embryo homogenates. N is three replicates of 10 embryos per genotype. J) GSH/glutathione was measured in Stage 14–16 embryos homogenates. The raw readings show the μM concentration within the reaction (rxn). K) Shows the measurement in panel J corrected for differences in embryonic volumes and displays the data as embryonic GSH concentrations. J&K) Y-axes do not start at 0. N is three replicates of six embryos per genotype. P values were calculated using unpaired, two tailed Student’s t-tests C,F,G,H,J,K,L) Significance was determined with unpaired Student’s t-tests in GraphPad Prism, ns is P > 0.05, * is P ≤ 0.05, ** is P ≤ 0.01, *** is P ≤ 0.001, and **** is P ≤ 0.0001. A,D,E) significance was determined by DEseq2’s p-adjusted value using the 3 replicated per genotype. Error bars represent standard deviation.

While powerful for verifying changes in abundance for individual proteins, this immunostaining approach is not conducive to a comprehensive analysis of expression changes, in part because verified antibodies are only available for a few of our candidate genes. Therefore, we opted for a proteomic approach to simultaneously probe changes for thousands of proteins. LC-MS-MS was performed on wild type, Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- embryos. We were able to detect peptides from ~5,000 proteins in all three genotypes (details in Materials and Methods), 3,039 were at similar levels of normalized abundance (S9 Table). In addition, 588 were differentially abundant in both Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- embryos. These 588 differentially abundant proteins were compared to the 269 genes which were differentially expressed in the RNAseq data (Fig 5C, the 3-fold overlap and the Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- overlap); we found that 94 genes were detected in both and of those 33 genes were significantly different at both the protein and mRNA level. Note that we permitted mRNA and protein levels to vary in different directions, for example, Dhod mRNA is down in both mutants while protein levels are up. Within the 33 differentially expressed genes in both experiments were Glutathione synthase (GSS), Adipose triglyceride lipase ATGL/Bmm, and Glutathione s-transferase T4 (Gstt4), which will be examined in more detail in subsequent sections. Thus, both approaches point to qualitatively similar responses of the embryos. This congruence is particularly remarkable since–for technical reasons–the two approaches differed in experimental details (e.g., the zygotic genotype of the embryos). We conclude that lipid-deprived embryos indeed mount a dramatic active response that results in global changes to both transcriptome and proteome.

For the ~588 genes with different peptide abundance in both mutants (Fig 6A), we then performed gene ontology (GO) analysis, using genes with similar levels in all three genotypes (3,039) as background (S10 Table). We found a robust response of GO terms relating to metabolism, with the strongest hits including ‘catalytic activity’, ‘small molecule metabolic process’, ‘oxidoreductase activity’, and ‘mitochondrion’ (Fig 6C and S11 Table). Similar GO matches were found when analyzing the differentially expressed mRNA in Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- embryos (S8 Table). We conclude that lipid-deprived embryos massively alter their metabolic proteome.

Enzymes for glutathione metabolism are altered in lipid-deprived embryos

To follow up on the omics data sets, we sought a response that was novel in its connection to LDs and that was following the same trajectory in all our LD-deprived genotypes. The following GO terms stood out: ‘Glutathione metabolic process’ enriched 3.3-fold (P = 2.2x10-5), ‘oxidoreductase activity’ enriched 1.98-fold (p = 1.63x10-9), and ‘sulfur compound metabolic process’ enriched 2.39-fold (p = 3.88x10-6) (Fig 6C and S11 Table). Our RNAseq had found significant upregulation of several redox genes including glutathione synthase and GSTT4. Thus, both the transcriptome and proteome analysis suggest that in our mutant embryos glutathione metabolism is altered.

Glutathione (GSH) is a tripeptide that serves as an intracellular reducing agent. For example, it is used to neutralize reactive oxygen radicals, in the process becoming oxidized to glutathione disulfide (GSSG), a dimer of two glutathione molecules joined via a disulfide bridge. Glutathione-S-transferase enzymes can utilize GSH as a reducing agent to reconcile unwanted oxidation on proteins, lipids, and other xenobiotics like pesticides [34]. GSH serves broad functions in metabolism and as an antioxidant. Because of its critical roles, its levels are controlled by multiple pathways: GSH is synthesized by the sequential action of two enzymes, glutamate-cysteine ligase (GCL) [35] and glutathione synthetase (GSS) [36]. In Drosophila, GSH is regenerated from GSSG by thioredoxin reductase (TRX) [37].

Our data suggest that lipid-deprived embryos display broad changes in multiple aspects of glutathione metabolism. In the glutathione synthesis pathway, the catalytic subunit of GCL (GCLC) is increased in dPLIN2-/-, while the modifying subunit (GCLM) is down in both Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- at the peptide and mRNA level (Fig 6B and S2, S4, and S9 Tables). The second enzyme in the pathway, GSS, is increased in all three mutants at the mRNA and peptide level in both Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- (Fig 6B) as is the enzyme thioredoxin reductase (Trxr1) responsible for regenerating glutathione from the oxidized dimer (GSSG, Fig 6B). Of 24 glutathione transferases detected in our proteome, ten displayed significantly different peptide levels. Several members of GST subfamilies D and T were upregulated in both mutants, with the three downregulated GSTs belonging to subfamilies Z and E (Fig 6B), perhaps indicating specific GST family needs to combat LD-deprivation.

Increases in GSS, Trx1, and GCLC are expected to increase GSH levels; GCLM reduction is known to reduce GSH levels [35]. It is therefore not obvious how total GSH levels might be affected. We homogenized Stage 15 wild-type, Jabba-/-, klar-/-, and dPLIN2-/- embryos and measured free GSH concentrations in the homogenates using a luciferase-based assay. As embryos of the four genotypes have slightly different average volumes (wild type (OrR) 9.3nL, Jabba-/- 8.8nL, klar-/- 9.2nL, and dPLIN2-/- 8.7nL), we corrected the raw reads by volume to determine the GSH concentration within the embryo (Fig 7K; raw reads are shown in Fig 7J). Indeed, GSH levels are elevated in the mutants compared to wild type.

LD-deprived embryos display reliance on the glutathione pathway

The altered regulation of the glutathione pathway in the lipid-deprived embryos suggests that it is important to combat stress from nutrient deprivation. We therefore examined the functional relevance of this pathway in our mutants by employing the Gal4-UAS system to drive dsRNAs targeted against GSS (combines the recently duplicated GSS1 and GSS2 [36]) and GSTT4. To avoid disrupting oogenesis, we opted for zygotic knockdown, crossing mothers carrying the da-Gal4 driver to fathers with the UAS dsRNA constructs. Even though da may have sexually dimorphic expression levels, we picked this driver because it is expressed in the yolk cell, unlike actin and tubulin-based drivers (as judged from BDGP (see Materials and Methods for citation details) in situs: probe FI13819 for da, probe RE44641 for alphaTub67c, probe RE02927 for actin5C). For most experiments, we used a da-Gal4 insertion on the third chromosome; for klar experiments, we used an insertion of the same construct on the second chromosome. Introducing da-Gal4 into a wild-type, klar-/-, or dPLIN2-/- background proved unproblematic. However, in a background fully null for Jabba, the da-Gal4 driver dramatically reduced embryo viability, for unknown reasons. We therefore generated an alternative line with reduced Jabba expression, in which the driver is paired with the hypomorphic allele JabbaLow (referred to as JabbaL in the following). Embryos from JabbaL/L mothers have an intermediate LD allocation defect (JabbaL/L Fig 6C, wild type and Jabba-/- in Fig 4A). In a JabbaL/L background, Jabba protein levels are ~1/8 of what is observed in the wild type [24], and we noticed no ill effects from Gal4 expression on embryo viability.

Using a hairpin targeting GSTT4, we observed significant reduction in hatching success in the JabbaL and dPLIN2 mutant backgrounds (down 35% in JabbaL and 15% in dPLIN2-/- relative to the no-hairpin controls), but not in wild type (Fig 7F). The strength of the effect is remarkable given that GSTT4 is only one of 24 glutathione transferases whose expression we detect in the embryo (S9 Table) and one of seven upregulated in both mutants (Fig 6 and S9 Table). Despite this redundancy, Jabba and dPLIN2 mutants apparently rely on GSTT4 for survival.

It is conceivable that the strong effect of the hairpin is due to off-target effects, resulting in knockdown of not just GSTT4, but also other GSTs. We believe this is unlikely because a hairpin against a GSTD family member showed no reduction in hatching. However, even in such a scenario, our results still strongly argue that Jabba and dPLIN2 mutants are uniquely reliant on the glutathione pathway. In addition, we found that a mutation of GSTT4 already severely compromises embryonic development in a wild-type background: although a GSTT4 allele due to an insertion of a MiMIC element ([38]; FlyBase, MI07169-TG4.1) is viable and fertile, over 70% of embryos from the homozygous stock failed to hatch (Fig 7L). The majority of the embryos reached Stage 17 (Fig 7M), began hatching contractions, then gradually ceased moving while turning a rusty hue (Fig 7N). Finally, attempts to make a stock double mutant for Jabba and GSTT4 failed, with intermediate crosses being notably sick. These results are consistent with the notion that depletion of GSTT4 alone results in similar phenotypes as observed in our LD-deprived mutants and when combined with Jabba mutations causes inviability.

According to published in situ data, GSS2 mRNAs are maternally provided (BDGP GSS2 probe/CG32495: AT02852). If there is indeed a large pool of these proteins from a maternal source, zygotic knockdown may not be effective. Nevertheless, a zygotically introduced hairpin which targets both genes significantly reduced hatching success in the Jabba mutant background (down 23% in JabbaL relative to the no-hairpin control) but had no noticeable effect in the wild type (Fig 7F). In the dPLIN2-/- backgrounds, there was no statistically significant difference, though mean hatching success rates were lower than wild-type/OrR outcross controls.

Combined, our data indicate that lipid-deprived embryos rely on the glutathione system for efficient hatching success.

Lipid peroxidation of exogenous lipids is elevated in LD-deprived embryos

One of the functions of the glutathione system is to protect against oxidative damage. Our proteomic and mRNA data indicate an even broader oxidative stress response in our lipid-deprived embryos, with the upregulation of the reducing enzymes Prx6b, Grx1, Prx6C, and SelR (Prx6b and Grx1 Fig 5D, Grx1, Prx6c, and SelR S9 Table) and high significance of GO terms for ‘Oxidoreductase activity’ (P = 1.63 X 10−9). Finally, human orthologs of GSTT4 (hGSTT1 and hGSTT2) are implicated in cancer and epilepsy [39], which may be a result of increased oxidative stress in humans null, or otherwise mutant, for hGSTT1 [39].

The substrate(s) for GSTT4 is unknown and, based on GSTT-family orthologs (GSTT4 annotation on FlyBase), could be hydrogen peroxide, oxidized proteins, or peroxidized lipids. We therefore tested for lipid-peroxidation activity in our LD-deprived mutants. We prepared homogenates from Stage 14–16 embryos, added the lipid-peroxidation sensor BODIPY-C11, and measured the fluorescent properties of the preparation. BODIPY-C11 is a fatty acid analog that exhibits bright red fluorescence in its reduced state. When oxidized, fluorescence emission shifts to green, and thus the ratio of green to red signal provides a measure for the extent to which it has been oxidized. Compared to the wild type, there was a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in Jabba-/-, klar-/- and dPLIN2-/- (Fig 7G). We also performed this assay on newly hatched wild type, klar-/-, and Jabba-/- L1 larva, and found a significant increase in lipid peroxidation in Jabba-/- (Fig 7H), and a trend in klar-/- consistent with additional peroxidation (Fig 7G, p = 0.13). These results indicate that LD-deprived embryos display an oxidative burden that persists even post embryogenesis. Because our mRNAseq and proteomics data indicate that mitochondrial gene products are altered, we looked for evidence of hampered mitochondrial function using the inner membrane potential dye TMRE. We exposed Stage 15 embryo homogenates to the dye TMRE, which fluoresces proportionately to the inner mitochondrial membrane’s potential. We found no difference between wild type, Jabba-/-, and dPLIN2-/- (Fig 7I).

We then tested whether GSTT4 was capable of reconciling the BODIPY-C11 lipid peroxidation. We drove the GSTT4 RNAi in our wild type and JabbaL/L da-gal4 lines and tested for lipid peroxidation using BODIPY-C11. There was significantly more oxidation of BODIPY-C11 with GSTT4 RNAi in both the wild type relative to wild type with RNAi and Jabba-/- relative to JabbaL/L with RNAi (Fig 7G). Thus LD-deprived embryos generate increased levels of BODIPY-C11 lipid peroxidation and zygotic expression of GSTT4 reduces oxidative damage in wild type and Jabba mutants.

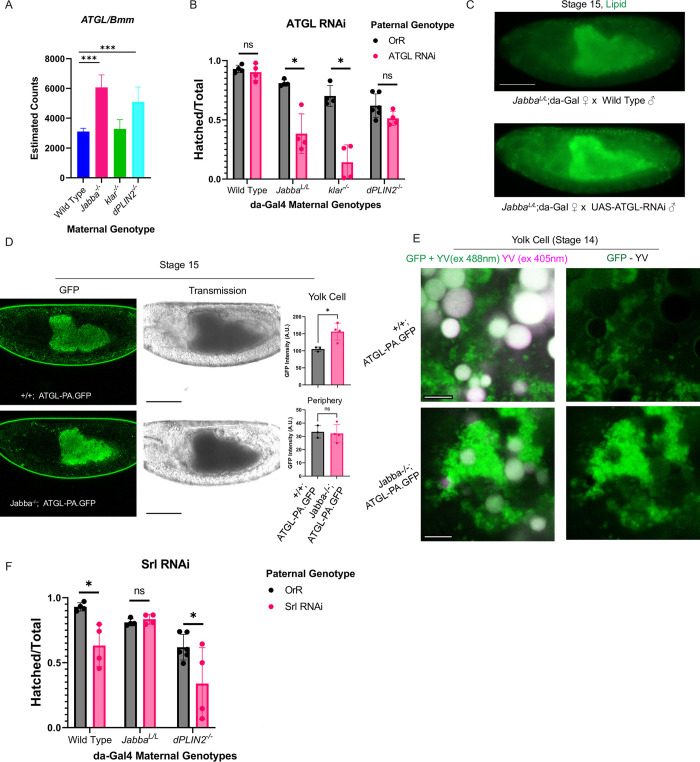

LD-deprived mutants have an increased reliance on zygotic ATGL/Bmm

Both the transcriptomic and proteomic datasets are enriched for genes involved in fatty acid and lipid metabolism. For example, in both Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- mutants, we found an increase in protein levels for the LD protein Stur (a highly conserved LD hydrolase [40]) and FASN1 (fatty acid synthase) (Fig 6B). However, there were also sharp differences, such as for the prominent LD lipase ATGL (also called Brummer in Drosophila), the principal cytosolic triglyceride lipase in higher animals. Even though ATGL mRNAs were up for Jabba-/- and dPLIN2-/- mutants compared to wild type (Fig 8A), protein levels were only increased in Jabba-/- embryos, by about ~70% relative to wild type. In dPLIN2-/- embryos, they were even decreased by ~30% relative to wild type. This discrepancy is surprising, as ATGL is a key enzyme in lipid metabolism and known to be essential for Drosophila embryogenesis [6,10]. Yet it does not appear to be part of a shared response to lipid deprivation.

Fig 8. LD-transport mutant embryos have an increased reliance on zygotic ATGL.

A) Relative mRNA levels for the lipase ATGL/Bmm in wild type and the three LD-deprived embryos. B) Embryonic hatching success for embryos with zygotic RNAi for UAS-ATGL-RNAi driven by da-Gal4. N is roughly 100 embryos scored on four different days from at least two sets of crosses per genotype. C) Neutral lipid staining (Nile Red) of Stage 15 embryos from JabbaL/L;da-gal4 mothers crossed to either wild type or UAS-ATGL-RNAi fathers. Note the additional lipid signal in embryos with zygotic ATGL RNAi. Scale bar 100 μm. D) Endogenously tagged ATGL-PA-GFP shows condensed signal in the periphery of Jabba-/- embryos relative to wild type, and more intense signal in the yolk cell. Transmission images show the embryos are of the same stage. GFP intensity in the yolk vs the periphery is quantified in the graphs on the right. N is three embryos for wild type and four for Jabba-/-. Scale bars 100 μm. E) Endogenously tagged ATGL-PA-GFP shows increased signal in the yolk cell of Jabba-/- embryos relative to wild type. As the yolk cell contains autofluorescent, broadly excited yolk vesicles, we first show the unedited GFP channel with a 405nm channel (peak yolk vesicle excitation) super imposed to show the signal attributable to yolk vesicles in white. The next images have that 405nm channel subtracted from the GFP channel to only show signal from GFP. Scale bars 5 μm. F) Embryonic hatching success for embryos experiencing RNAi for Srl. Wild-type embryos respond but LD-transport mutants do not, showing that our RNAi system’s phenotypes are attributable to interactions between the maternal background and RNAi target, and not a general sensitization of our mutants to RNAi. N is roughly 100 embryos scored on four different days from at least two sets of crosses per genotype. B,D,F) Significance was determined with unpaired Student’s t-tests in GraphPad Prism, ns is P > 0.05, * is P ≤ 0.05, ** is P ≤ 0.01, *** is P ≤ 0.001. A) significance was determined by DEseq2’s p-adjusted value using the 3 replicated per genotype. Error bars represent standard deviation.

This discrepancy extends to the functional level. When we used da-Gal4 lines to drive ATGL RNAi, viability in the JabbaL/L background dropped from ~80% viability to ~38% (Fig 8B). In contrast, there was no significant change in hatching success for wild type and dPLIN2-/- embryos, despite the fact that their ATGL proteins are lower. Thus, not only is ATGL protein expression upregulated in Jabba-/-, but embryos are particularly sensitive when its levels are reduced. In klar-/- embryos, viability upon ATGL knockdown drops from 66% to 14% (Fig 8B), suggesting that zygotic expression of ATGL is uniquely important when LDs are mislocalized to the yolk cell.

Other observations also suggest that aspects of lipid metabolism are different when LDs are mislocalized versus depleted everywhere. PGC1α/Spargel (Srl) is a nuclear transcription factor implicated in a number of lipid signaling pathways. Zygotic SRL RNAi led to a drop in viability in the wild type and in dPLIN2-/- embryos; however, no such reduction was observed for embryos from JabbaL/L mothers (Fig 8F).

While all three mutants have reduced LD availability in the periphery, there is one dramatic difference between dPLIN2 embryos and the LD-allocation mutants: the latter have a normal supply of LDs to support development, just in the wrong tissue. If they were able to access this LD population, it might alleviate their lipid-deprived state.

To gain further insight into the ATGL discrepancy, we examined the distribution of ATGL across the embryo. We utilized a new ATGL allele in which the endogenous PA isoform is C-terminally tagged with GFP [41] and introduced it into wild-type and Jabba-/- backgrounds. In Stage 15, wild-type embryos displayed dispersed green signal in the periphery (Fig 8D), while Jabba-/- mutants had more signal in the yolk cell (Fig 8D, quantification), and the peripheral signal was more condensed (Fig 8C). Because the yolk cell contains broadly autofluorescent yolk protein vesicles, we sought to separate the GFP and yolk autofluorescence to unambiguously detect ATGL-GFP. High magnification images of the GFP channel were taken in the yolk cell at Stage 14, when the yolk cell is pressed up against the amnioserosa just beneath the eggshell (Fig 8D). Individual LDs could be made out at this stage (Fig 8E), confirming that we could resolve GFP positive LDs versus yolk vesicles. Then images were taken with excitation at 405nm to capture only yolk vesicle fluorescence, which were then subtracted from the GFP channel (Fig 8E). This analysis showed that Jabba-/- embryos indeed contain much more ATGL-PA-GFP in the yolk cell than their wild-type counterparts.

To test whether zygotic ATGL expression in the JabbaL/L background is consuming LDs, we performed neutral lipid staining on embryos with and without ATGL RNAi. Embryos with ATGL RNAi had more LD staining (Fig 8C), supporting the idea that Jabba embryos upregulate ATGL expression from the zygotic genome to consume their misallocated LDs and survive-LD deprivation.

Discussion

Here we provide the first evidence that LD allocation amongst embryonic lineages impacts subsequent development. At fertilization, LDs are found homogenously throughout the early Drosophila embryo, but by cellularization they are asymmetrically distributed between cell types: we estimate that 80% of all LDs are present in the peripheral tissue, with the rest allocated to the yolk cell. This uneven inheritance requires an elaborate machinery: actin-driven cytoplasmic streaming, the anti-clustering activity of Jabba to prevent LDs from sticking to glycogen granules, kinesin-1 and cytoplasmic dynein-driven motion of LDs along microtubules, and regulators like Klar, Halo, and Wech that ultimately control the balance of kinesin and dynein activity on LDs [1,10,11,15,16,17,42]. Yet until now the physiological relevance of these complex motions was unknown. We disrupted two distinct mechanisms of allocation using mutants in Jabba and klar, which results in embryos with normal numbers of LDs sorted into the wrong lineage. These embryos show numerous signs of metabolic distress as well as delays in embryogenesis. Using dPLIN2 null embryos as an LD-deprived, but appropriately localized, reference, we show that mis-allocation mimics decreased maternal loading of LDs. Our data is the first to demonstrate that early embryonic LD lineage allocation ensures their accessibility and supports later metabolic success, punctual development, and protects redox homeostasis. In particular, we show that where LDs are in the nascent body plan is an important player in their utilization (S1 Graphical Abstract), comparable in importance to receiving a full LD supply from their mother. As animal embryos of diverse species sort LDs very early in embryogenesis (Fig 1), we propose that early embryonic asymmetric LD allocation is a conserved means of sorting LDs into those embryonic lineages that require them for timely development.

Embryos can survive despite a substandard nutrient supply

Embryos from oviparous animals, including Drosophila, are a closed system unable to take up nutrients from the environment. All the nutrients required for embryogenesis must therefore be provided by the mother to the oocyte. Our measurements suggest that during normal Drosophila development most of the TAG reserves inherited from the mother are consumed by the end of embryogenesis (Fig 3A–3C), implying that the mother endows the embryo with just enough lipid reserves to support development until the larva can feed. It is therefore surprising that the majority of Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos hatch successfully, even though they cannot access all their neutral lipid stores and retain them into larval stages. Similarly, even though dPLIN2-/- embryos have only ~66% of the wild-type triglyceride supply, ~60% still successfully complete embryogenesis (and most of the rest reach Stage 17).

Intriguingly, a parallel situation is observed with the maternal supply of glycogen. Glycogen reserves are largely consumed during Drosophila embryogenesis [5,28], yet embryos laid without any glycogen (in mothers mutant for GlyS, glycogen synthase) hatch at near wild-type levels [43]. Similarly, embryos that have glycogen reserves but cannot access them (because of the absence of GlyP, glycogen phosphorylase) hatch successfully [43]. Somehow, Drosophila embryos are able to hatch even if they lack a substantial portion of their maternally provided energy stores. We hypothesize that they achieve metabolic flexibility by switching between energy substrates if needed. Indeed, embryos lacking glycogen show reduced levels of acyl carnitines [43], suggesting increased lipid breakdown to compensate for the lack of carbohydrates. In turn, our lipid-deprived embryos upregulate carbohydrate-related genes, including the trehalose transporter Tret1-1, and Trehalase (Figs 7A–7C and 6B).

Metabolic flexibility, including flexibility in substrate utilization, is a trait previously described in mature organisms in mammals and flies [44,45,46,47,48]. Here, the animal can utilize multiple biological molecules to accomplish the same goal. For example, both glucose and lipid-derived products (like ketone bodies or fatty acids) can be used in energy production. Substrate switching is integral to surviving some of the most common human diseases, including diabetes [48], neurodegenerative diseases [49], and heart disease [50]; individuals with a metabolic disease have dramatic alterations, for example, utilizing lipid-derivatives in place of glucose in individuals with diabetes [48].

We propose that LD- or glycogen deprived embryos may similarly be able to rewire their metabolism to more heavily rely on other substrates. A detailed test of this hypothesis will require interrogating carbohydrate levels in a lipid deprived background, investigating the contribution of amino acid consumption (glutamate, aspartate, and glycine are thought to be consumed [6,51]), and measuring oxygen consumption during embryogenesis to determine if hatching can be achieved with less overall respiration or if deprived embryos need to ‘burn the furniture’ to hatch. While null mutants in Jabba, klar, dPLIN2, GlyP, and GlyS can hatch successfully, our attempts to generate several of the double mutant combinations failed, consistent with the idea of compensation between energy sources.

Even though LD-deprived embryos are able to hatch, they are compromised. Starvation is often associated with changes in oxidative damage [52,53,54], and multiple lines of evidence suggest that LD-deprived embryos are challenged in maintaining their redox balance. First, using BODIPY-C11, we find all three LD-deprivation mutants have a significant increase in lipid peroxidation. Second, genome-wide analysis indicates that the mutants upregulate many transcripts and proteins involved in redox homeostasis, as if they need to combat redox stress. Finally, Jabba-/- mutants, but not wild type, have a significant drop in viability when glutathione synthase or glutathione transferase T4 are zygotically knocked down.

An active, beneficial response to lipid starvation

We find that embryos respond to lipid deprivation at the transcriptional and proteome level. We detect robust signals in oxidative stress, sugar metabolism, nucleotide metabolism, amino acid metabolism, iron metabolism, sulfur containing proteins, ubiquitin conjugation systems, ER and mitochondrial genes at the mRNA level and peptide level. In principle, the observed changes might be a consequence of a breakdown in gene regulation for embryos struggling to survive. However, we favor the idea that this response is largely adaptive, benefitting the embryo by allowing it to overcome the metabolic challenge. The upregulation of several key players in trehalose metabolism is certainly consistent with the idea of compensating for the lack of lipids by upregulating carbohydrate utilization. And for two upregulated enzymes, ATGL and GSTT4, we show that they benefit the lipid-deprived embryo, as RNAi for both genes diminishes hatching. Importantly, this sensitivity of lipid-deprived embryos to the loss of certain factors is specific and does not indicate that they are simply impaired across the board; while knockdown of the lipid responsive transcription factor Srl/PGC1alpha reduced the viability of wild type and dPLIN2-/- embryos, it was not detrimental to Jabba-/- embryos. We conclude that embryos can mount an adaptive response to lipid deprivation that ensures efficient hatching. To fully characterize the breadth of this adaptation in the future, it will be important to develop additional measures for the physiological state of these embryos and test which parameters are compromised when candidate response genes are knocked down.

The oxidative stress we detected in our LD-deprived embryos suggests an intermediate source of oxidative damage that is activated when LDs are absent. Likely, this is the mitochondria which are the site of breakdown of fatty acids released from LDs [1], a source of cellular ROS [55], and implicated in both our mRNAseq and proteomics data as being affected in our mutants. Specifically changes in mitochondrial proteins handling metals such iron (ferritin light and heavy chain, IRP 1A, MagR, etc.) and copper (GRX1) suggest LD-deprivation causes insults in key mitochondrial enzyme complexes. We suspect that in our LD deprived mutants fatty acid import into the mitochondria is reduced, leading to the downstream effects on the mitochondrial proteome. However, our attempts to perturb the mitochondrial fatty acid importer CPT1/Whd through zygotic knock down lead to no detectable effects, possibly because CPT1 is abundantly supplied maternally [56]. Double mutants for the whd1 and klarYG3 alleles were inviable, supporting a link between LD allocation and mitochondrial fatty acid consumption.

The existence of this elaborate response suggests that in nature newly laid embryos are not always laid with a full complement of nutrients and thus need to be able to adapt to survive. The nutritional state of the mother certainly can have a strong effect on her overall fecundity and the number of eggs laid [57,58]. Although there are homeostatic mechanisms that result in similar endowment of oocytes with triglycerides despite varying maternal nutrition [59], it is not known how well they can keep nutrient levels stable across conditions, especially in natural environments where nutrient availability likely fluctuates widely.

Hatching delay may be a general response to nutrient deprivation

Lipid-deprived embryos also exhibit delayed hatching. Most of the delay occurs after Stage 15, when lipid deprivation has already resulted in a dramatic response at the transcriptomic and proteomic levels. Thus, the delay is not what triggers the adaptive response of the embryo; rather, embryos are able to sense their nutrient-deprived state by an as-yet uncharacterized mechanism. Intriguingly, a hatching delay of similar magnitude is observed in embryos lacking the majority of their glycogen supply [43]. As embryos contain roughly 10x the calorie supply in LD-stored TAG as found in glycogen [5], these glycogen mutants (GlyP and GlyS) are in similar state of gross calorie deprivation to our Jabba-/- mutants which hatch with ~15% of their TAG unconsumed and another ~60% consumed in the wrong tissue, and dPLIN2-/- mutants which receive ~30% less TAG from their mother [26]. A developmental delay may therefore be a general response embryos employ when their calorie supply is diminished. It will be interesting to determine whether glycogen-deprived embryos also respond with drastic changes to their transcriptome and proteome and to what extent this response differs from that observed upon lipid deprivation. Such a comparison may shed light both on how suboptimal nutrition is sensed and how it leads to a developmental delay.

Curiously, dPLIN2 mutants are more severely delayed than Jabba-/- and klar-/- mutants, even though LD starvation of the periphery appears worse in the latter genotypes. We estimate based on quantification of LD abundance in TEMs immediately post cellularization, that for the latter genotypes ~70% of LDs that would normally be in the periphery are shifted to the yolk cell. In contrast, dPLIN2-/- embryos have a global ~30% reduction in LDs, in both the periphery and yolk cell [26]. Why, then, are Jabba and klar mutants not more severely affected if their peripheral cells are more LD deprived? Our analysis suggests that these mutants partially overcome this peripheral deficit by consuming a portion of the inappropriately localized LDs via upregulation of the lipase ATGL. Consistent with this idea, TAG measurements in Jabba-/- and klar-/- show that only ~1/4th of excess LDs deposited are not consumed. And ATGL knockdown in Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos interferes with yolk LD consumption.

ATGL is essential for Drosophila embryogenesis [6] and is the major cytoplasmic enzyme which liberates TAG for consumption. We find that Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos, but not dPLIN2-/-, require additional transcription of ATGL for survival, relative to wild type (Fig 8B). Notably, wild type does not require zygotic expression of ATGL at all, if provided maternally [6]. Jabba-/- and klar-/- embryos may, then, employ boosted zygotic levels of ATGL to increase the lipolytic capabilities of the yolk cell. Thus, flexible utilization of ATGL in Jabba-/- and klar-/- mutants appears to be able to compensate for a more severe LD-deprivation in the periphery.

In summary, our analysis provides the first evidence that the nutrient layout of the embryo plays a role in the metabolic success of embryogenesis (see S1 Graphical Abstract). Having LDs in the wrong tissue is akin to receiving a reduced maternal supply. Further, we provide evidence that LD deprivation causes oxidative stress and delays embryogenesis. Finally, we show that embryos are capable of overcoming LD deprivation through flexible utilization of ATGL and glutathione metabolism. In the absence of asymmetric allocation, mothers could presumably achieve an adequate LD supply for the developing epithelium by increasing the overall number of LDs loaded into the egg. However, this strategy would result in a yolk cell with superfluous, unused LDs and thus wasted resources. Asymmetric inheritance of LDs allows mothers to optimize their LD investment per embryo without compromising successful embryogenesis.

Methods

Origin of fly strains

Oregon R was used as the wild-type strain. JabbaDL, referred to as Jabba-/-, was generated previously in the laboratory and is a strong loss-of-function allele with no Jabba protein detected in early embryos [21]. JabbaLow is a hypomorphic allele with a strong reduction in protein production [24]. klar-/- refers to the klarYG3 allele generated previously in our lab; although this loss-of-function allele does not eliminate all Klar isoforms, it abolished the klar β isoform that regulates LD transport in early embryos [60]. The strain referred to as ATGL-RNAi was obtained from the Vienna Drosophila Resource center (VDRC ID 37880). The strains referred to as GSTT4 RNAi (BL# 36717), GSS RNAi (BL# 55150), SRL RNAi (BL# 33915), GSTT4-/- (BL#77777), and whd1 (BL#441) were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (BDSC). LpR1-/- and Lpr1-,LpR2-/Tm3 were generated by Joaquim Culi’s group [29]. The dPLIN2-/- allele is the protein null allele LSD-2KG previously described [27] The da-Gal4 lines were generated from Bloomington stock BL#55850 which has a 3rd chromosome insertion, except for klar which used a 2nd chromosome insertion of the same construct generously provided by Elizabeth Knust (FlyBase ID FBti0162419). ATGL-PA-GFP flies [41] were generously provided by Xun Huang.

Publicly available resources

FlyBase [61] was utilized for numerous genetic and curation resources. Drosophila embryo mRNA expression data used are from the Berkley Drosophila Genome Project (BDGP) [62,63,64]. GOrilla [65,66] was utilized for GO analysis of the proteomics data set. FlyEnrichr [67,68] was utilized for GO analysis of the mRNA data set.

Microscopy

Laser scanning confocal microscopy was performed on a Leica SP5 equipped with HyD detectors, using either a 40x objective to show most of the embryo, or a 63x objective for subregions. Spinning disc confocal microscopy was performed on an Andor Dragonfly in the University of Rochester High Content Imaging Core and was used to capture the mud snail embryo images with a 40x objective. Epifluorescence imaging was performed on a Nikon Eclipse E600 using a 20x objective, Spot Insight imaging software, and a Diagnostics Instruments’ 14.2 Color Mosaic camera. All images were assembled in Adobe Illustrator.

S1–S3 Videos were captured at 1 frame per 2 seconds, 512x512 pixels. Video processing was done using FIJI (NIH).

Sample sizes were as follows. For live imaging, at least three embryos were imaged per genotype per experiment. For fixed samples, the stainings were performed at least twice, with multiple embryos imaged per staining. For TEM analysis, the core facility was given ten appropriately staged embryos per genotype per experiment, and then chose which were imaged based on staining success.

Exclusion criteria for imaging embryos were predetermined. Embryos not of the stage of interest, determined to have expired during preparation or image acquisition, or which were imaged in the incorrect orientation/focal depth were excluded.

Periodic acid Schiff (PAS) and LD staining

Embryos were collected on apple juice plates for the desired time range and dechorionated with 50% bleach and fixed for 20 minutes using a 1:1 mixture of heptane and 4% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). To detect GGs, embryos were devitellinized using heptane/methanol and subsequently washed three times in 1xPBS/0.1% Triton X-100. Embryos were incubated first in 0.1M phosphatidic acid (pH 6) for 1hr and then in 0.15% periodic acid in dH2O for 15min. After one wash with dH2O, embryos were incubated in Schiff’s reagent (Sigma-Aldrich) until the embryos went from uncolored, to pink, to red (~2 minutes). To stop the reaction, it was quenched with 5.6% sodium borate/0.25 normal HCl stop solution for at least 2 minutes with agitation.

After replacing half the volume of the stop solution with an equal volume of 1×PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 to reintroduce detergent, the sample was shaken vigorously to free embryos stuck to the container or each other. For subsequent imaging, embryos were mounted in either Aqua-Poly/Mount from Polysciences or a glycerol solution (90% glycerol, 10% PBS) since mounts with ‘antifade’ or O2 scavenging additives should be avoided for this approach. Fluorescent PAS signal was then detected using an Alexa633 channel on a Leica Sp5.

To detect LDs by staining, the methanol step for devitellinization needs to be omitted as it extracts neutral lipids. Instead, after fixing with heptane/formaldehyde, the embryos were washed extensively in a wire mesh basket with 1×PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 to remove residual heptane, then transferred to a 1.7mL microcentrifuge tube. They were then washed 2x with 1×PBS/0.1% Triton X-100. For costaining with PAS, embryos were incubated in 0.1M phosphatidic acid (pH 6) plus 1μL of 1mg/mL BODIPY 493/503 (Invitrogen) for 1 hr; then the same steps as for PAS above were followed (starting with periodic acid incubation). As red lipid dyes overlap Schiff’s reagent’s spectra, we avoided them for costaining with PAS.

For LD staining without PAS costaining, the 1×PBS/0.1% Triton X-100 wash was removed and replaced with 1×PBS/0.5% Triton X-100/10% BSA/0.02% sodium azide; embryos were incubated for 1 hr. The solution was replaced with 1 ml of fresh 1×PBS/0.5% Triton X-100/10% BSA/0.02% sodium azide and then either 1μL of 1mg/mL BODIPY 493/503 in DMSO, 1 μL LipidSpot 610 (1000x) (Biotium) in DMSO, or 10μL of 200mg/mL Nile Red (Sigma Aldrich) in acetone was added. After 20 min of staining, embryos were washed and mounted as in the previous paragraph.

Live imaging

For live imaging involving dye injections, a previously published procedure was followed [20]. In short, embryos were collected on apple juice plates for the desired time, hand-dechorionated, transferred to a coverslip with heptane glue, desiccated, and placed in Halocarbon oil 700. Embryos were then injected with DMSO containing BODIPY 493/503 (1mg/mL), SIR Tubulin or SPY Tubulin and imaged on a Leica Sp5 confocal microscope.

Immunofluorescence