Introduction

The US residency application process is high-stakes, high-stress, and one in which medical student applicants usually have little firsthand knowledge of the programs to which they are applying, particularly as most programs have transitioned entirely to virtual interviewing.1 To fill this gap, applicants often review online resources, including the Doximity Residency Navigator (DRN),2-4 a platform based on the social media company’s database, which it claims comprises more than 80% of all US physicians.5 Each residency program’s page on the DRN contains basic information, including program size, fellowships offered, and the institutions where residents can expect to spend their time, as well as anonymized ratings and reviews by current residents and alumni.

In a 2019 issue of the Journal of Graduate Medical Education, authors from the Harvard Medical School Department of Ophthalmology reported inaccuracies in their residency program’s DRN page.6 Although Doximity corrected these errors when notified, the company refused to provide its raw data on which the erroneous information was based, calling into question the “integrity of the quantitative information that is being publicly shared for all programs.”6 Conversely, when we notified Doximity of errors in our program’s DRN page, company representatives informed us they could not correct them because the information was derived from individual profiles that could only be corrected by the physicians themselves. In this Perspective, we report continued inaccuracies in our own program’s information published on the DRN, show that these inaccuracies are increasing over time, and describe how Doximity’s methodology perpetuates erroneous information being presented to residency applicants.

Errors in the DRN

In 2022 we noted 2 key errors in the Westchester Medical Center anesthesiology residency program DRN page. First, the proportion of graduates with subspecialty training was listed as 26%, while we knew the true figure to be roughly twice that. Second, the DRN list of Top Feeder Medical Schools contained 2 institutions from which we had few residents and omitted others that were more represented.7 We learned that both these statistics are gleaned from Doximity’s database of physician profiles and calculated based on the total number of program graduates over the last 10 years.8 Based on our own records, we confirmed 51% of our graduates had pursued fellowship training and that 2 medical schools had been erroneously omitted from the Top Feeder Medical Schools list.

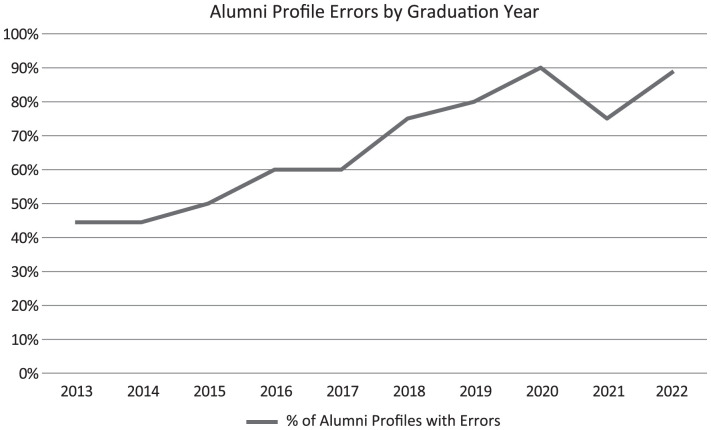

We then examined the Doximity profiles of each of our graduates from the last 10 years. Each profile in Doximity lists a physician’s medical school, residency, and fellowship training institutions in a section entitled Education and Training. We found that many of our graduates’ profiles did not correctly list their education and/or training institutions, in addition to other types of errors (see Table). In summary, over the 10 years reviewed, 65% of our graduates’ Doximity profiles contained errors, and the frequency of these errors increased over time (Figure). The most common error was not having our program listed as their residency training institution (42%), and the second was not having fellowship information listed (30%).

Table.

Doximity Errors in Alumni and Current Resident Profiles

| Error Type | Alumni Profiles (N=92), n (%) | Current Resident Profiles (N=40), n (%) |

| No residency listed | 39 (42.4) | 30 (75) |

| No fellowship listed | 28 (30.4) | Not applicable |

| Listed as incorrect type of health care professional | 10 (10.9) | 3 (7.5) |

| No profile | 6 (6.5) | 2 (5) |

| No medical school listed | 5 (5.4) | 9 (22.5) |

| Training incorrectly categorized as work experience | 3 (3.3) | 2 (5) |

| Two profiles | 3 (3.3) | 3 (7.5) |

| Incorrect residency listed | 2 (2.2) | 0 (0) |

| Other error | 2 (2.2) | 2 (5) |

Figure.

Percentage of Program Alumni With Doximity Profile Errors Relating to Education or Training Institution Identification

These findings accounted for the discrepancies in fellowship training rate and medical school affiliation published on our program’s DRN page, as these statistics are derived from individual physician profiles. Since many of our graduates are not correctly affiliated with our program in Doximity, it is likely that other DRN data points, such as alumni publication and clinical trial participation rates, are incorrect as well.

We also evaluated the Doximity profiles of our current residents and found that 83% of them contained similar errors to those seen among alumni (table). Most strikingly, most of our current residents did not have our program correctly listed on their profiles (75% of profiles), while another 5% had no profile at all.

Implications

Another feature of the DRN is its reputation-based ranking of all residency programs within a particular specialty. This is based on the Doximity Nomination Survey in which any board-certified physician can nominate up to 5 programs within their field of specialty. Other authors have shown that most residency applicants are aware of this ranking system and that it influences their decisions regarding where to apply, where to interview, and how to construct their rank lists.2-4 Still others have called into question the legitimacy of this reputation-based system, as rank is positively correlated with program size and age.9,10 To address these concerns, Doximity grants additional weight to the responses of non-alumni and program directors; however, the company does not publicly disclose exactly how much additional consideration is granted to these respondents.5

While any physician with Board certification can participate in the Doximity Nomination Survey, only physicians registered with Doximity are invited by email to complete it. The DRN also contains results from its Satisfaction Survey, which is limited to registered users. As most of our recent graduates and current residents are not correctly affiliated with our program in Doximity, they have not been invited to participate in the Nomination Survey, nor are they eligible to participate in the Satisfaction Survey. While the number of responses to the Satisfaction Survey is provided in the DRN (11 for our program), the number of participants in the Nomination Survey is not. If our program’s low level of Doximity registration is typical, it suggests that the results of the Doximity Nomination Survey are generated from a relatively small number of survey participants.

Conclusion and Advice for Programs

We conclude that errors in the Doximity profiles of our residents and recent graduates have resulted in misrepresentations on our residency program’s DRN page, suggesting serious flaws in Doximity’s proprietary data collection methods. Doximity representatives have stated to us that they are unable to correct these errors, as the data are derived from individual physician profiles, and the platform primarily relies on users to ensure their profiles are accurate. While the DRN’s goal to provide an independent view of residency training programs is admirable, the quality of the data it presents and the legitimacy of its reputation-based rankings is tenuous due to the frequency of errors in profiles, particularly physicians not being correctly affiliated with their training institutions.

To address inaccuracies in their DRN pages and improve their standing in the Doximity rankings, residency programs may be tempted to work within the existing system by encouraging their current residents and alumni to register with the platform, ensure accuracy of their profiles, and participate in the Nomination and Satisfaction Surveys. In our correspondence with Doximity, the company offered to collect the email addresses of our graduates so the company could reach out to them directly. However, our program determined that either coercing our residents and graduates to register with a for-profit entity or providing their personal information directly was ethically impermissible. Instead, our recommendation is that medical schools and residency programs educate medical student applicants regarding the limitations of the DRN and refer them to other not-for-profit resources, including the Association of American Medical Colleges Residency Navigator Tool or the Texas STAR database. Both resources provide independent and verified residency program information derived directly from reliable sources in a transparent manner.11,12 They also allow students to compare their applications to those of successfully matched residents, consistent with recommendations issued by the Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education to Graduate Medical Education Review Committee.13

References

- 1.Badiee RK, Hernandez S, Valdez JJ, NnamaniSilva ON, Campbell AR, Alseidi AA. Advocating for a new residency application process: a student perspective. J Surg Educ . 2022;79(1):20–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2021.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith BB, Long TR, Tooley AA, Doherty JA, Billings HA, Dozois EJ. Impact of Doximity Residency Navigator on graduate medical education recruitment. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes . 2018;2(2):113–118. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterson WJ, Hopson LR, Khandelwal S, et al. Impact of Doximity residency rankings on emergency medicine applicant rank lists. West J Emerg Med . 2016;17(3):350–354. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2016.4.29750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rolston AM, Hartley SE, Khandelwal S, et al. Effect of Doximity residency rankings on residency applicants’ program choices. West J Emerg Med . 2015;16(6):889–893. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2015.8.27343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doximity. Residency Navigator 2022-2023. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-22-00905.1. Accessed October 15, 2022. doximity.com/residency/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lorch AC, Miller JW, Kloek CE. Accuracy in residency program rankings on social media. J Grad Med Educ . 2019;11(2):127–128. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00534.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doximity. Westchester Medical Center. Accessed October 15, 2022. https://www.doximity.com/residency/programs/222082bf-b3b7-4533-84db-22095387afe2-westchester-medical-center-anesthesiology.

- 8.Doximity. Doximity Residency Navigator. Accessed October 15, 2022. assets.doxcdn.com/image/upload/pdfs/residency-navigator-survey-methodology.pdf.

- 9.Feinstein MM, Niforatos JD, Mosteller L, Chelnick D, Raza S, Otteson T. Association of Doximity ranking and residency program characteristics across 16 specialty training programs. J Grad Med Educ . 2019;11(5):580–584. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-19-00336.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Esmaeeli S, Seu M, Akin J, Nejatmahmoodalilioo P, Knezevic NN. Program directors research productivity and other factors of anesthesiology residency programs that relate to program Doximity ranking. J Educ Perioper Med . 2021;23(2):e662. doi: 10.46374/volxxiii_issue2_knezevic. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Association of American Medical Colleges. Residency Explorer Tool. Accessed March 12, 2023. https://students-residents.aamc.org/apply-smart-residency/residency-explorer-tool.

- 12.UT Southwestern Medical Center. Texas STAR. Accessed March 12, 2023. https://www.utsouthwestern.edu/education/medical-school/about-the-school/student-affairs/texas-star.html. Accessed 3/12/23.

- 13.Coalition for Physician Accountability. The Coalition for Physician Accountability’s Undergraduate Medical Education-Graduate Medical Education Review Committee (UGRC): Recommendations for Comprehensive Improvement of the UME-GME Transition. Accessed March 12, 2023. https://physicianaccountability.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/UGRC-Coalition-Report-FINAL.pdf.