Abstract

Down syndrome (DS), the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability, is associated with lifelong cognitive deficits. However, the mechanisms by which triplication of chromosome 21 genes drive neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction are poorly understood. Here, using the Ts65Dn mouse model of DS, we performed an integrated single-nucleus ATAC and RNA-sequencing (snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq) analysis of the adult cortex. We identified cell type-specific transcriptional and chromatin-associated changes in the Ts65Dn cortex, including regulators of neuroinflammation, transcription and translation, myelination, and mitochondrial function. We discovered enrichment of a senescence-associated transcriptional signature in Ts65Dn oligodendrocyte (OL) precursor cells (OPCs) and epigenetic changes consistent with a loss of heterochromatin. We found that senescence is restricted to a subset of OPCs concentrated in deep cortical layers. Treatment of Ts65Dn mice with a senescence-reducing flavonoid rescued cortical OPC proliferation, restored microglial homeostasis, and improved contextual fear memory. Together, these findings suggest that cortical OPC senescence may be an important driver of neuropathology in DS.

Keywords: Down syndrome, oligodendrocyte precursor cells, senescence, single-cell genomics, Trisomy 21

Significance Statement

Down syndrome (DS) is the most common genetic cause of intellectual disability worldwide, is characterized by chronic neuroinflammation, and results in a ubiquitous incidence of early-onset neurodegeneration. Here, we conduct single-nucleus multiomic profiling of the mature adult cortex of an established mouse model of DS, and systematically identify key perturbations in pathways critical for neurogenesis, myelination, and neuroinflammation. We discover the enrichment of a senescence- associated gene signature in trisomic cortical oligodendrocyte (OL) precursor cells (OPCs), validate our computational findings using orthogonal approaches, and show that a senescence-reducing flavonoid significantly improves memory deficits. Our findings suggest that OPC senescence may play a role in the pathogenesis of DS and that senescence-reducing treatment may provide a novel approach for improving cognitive dysfunction in DS.

Introduction

Down syndrome (DS) is the leading genetic cause of intellectual disability worldwide, occurring in one in ∼800 live births (Alexander et al., 2016; Kazemi et al., 2016) and is caused by the complete or partial triplication of Homo sapiens chromosome 21 (Hsa21; Antonarakis et al., 2020). DS results in learning, memory, and language impairment, leading to lifelong cognitive disability, as well as a universal risk of early-onset neurodegeneration (Zigman et al., 2008). Triplication of Hsa21 results in increased expression of ∼225 protein coding genes, as well as >300 genes of unknown coding or functional potential (Sturgeon and Gardiner, 2011). Overexpression of these genes results in complex perturbations of multiple processes involved in neurologic development and function (Becker et al., 1991; Barlow et al., 2002; Chakrabarti et al., 2007, 2010; Jose Luis Olmos-Serrano et al., 2016).

DS presents a unique opportunity for studying changes in brain aging across the lifespan, as DS individuals age prematurely and atypically (Antonarakis et al., 2020). Importantly, gene dosage imbalance of this relatively small set of genes has a profound cascading effect, including secondary changes in expression of hundreds of other genes, leading to the disruption of several pathways important for neurogenesis, cell differentiation, synapse formation and plasticity, axon guidance, immune regulation, and myelination (Becker et al., 1991). By 40 years of age, there is a ubiquitous occurrence of plaques and neurofibrillary tangles of hyperphosphorylated tau suggestive of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), as well as clinical signs of dementia, including changes in sociability, language, and depressive symptoms (Teller et al., 1996; Head et al., 2016; Godfrey and Lee, 2018).

Neuroinflammation, a key driver of neurodegeneration, is a neuropathologic hallmark of DS (Wilcock, 2012; Flores-Aguilar et al., 2020) and is in part driven by triplication of several immune-related genes, including four of the six interferon (IFN) receptors (Sullivan et al., 2016; Kong et al., 2020). There is also triplication of the amyloid precursor protein (APP) and S100β, with the resultant overexpression of the pluripotent neuroinflammatory cytokine interleukin-1 (IL-1; Lu et al., 2011; Wilcock and Griffin, 2013; Head et al., 2016). Importantly, there is evidence of microglial activation in DS humans and mice with trisomy, and reducing overactivated microglia restores cognitive performance in trisomic mice (Pinto et al., 2020). While neuroinflammation is recognized as a core feature of DS, the molecular mechanisms and age-related progression of inflammation-associated aging (“inflammaging”), as well as their relationship to cognitive decline, are poorly understood.

To address these gaps, we leveraged single-nucleus sequencing to identify candidate pathways perturbed in the cortex of a well-characterized DS mouse model. Ts65Dn mice contain a partial triplication of Mus musculus chromosome 16 (Mmu16) corresponding to trisomy of ∼55% of Hsa21 protein-coding orthologs (Reeves et al., 1995; Hyde et al., 2001; Gupta et al., 2016). These trisomic mice recapitulate many of the characteristics of human DS, including learning, memory, and cognitive deficits, as well as developmental delays and oligodendrocyte (OL) maturation deficits (Granholm et al., 2000; Hyde et al., 2001; Gupta et al., 2016). Through multiomic profiling of the mature Ts65Dn cortex, we identify broad disruptions in pathways associated with neuroinflammation, transcriptional and translational regulation, mitochondrial and ribosomal dysfunction, and the integrated stress response (ISR) at both the epigenomic and transcriptomic level across neuronal and non-neuronal cell populations. We further identify a senescence-associated gene signature in Ts65Dn oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPCs). Using orthogonal approaches, we validate our sequencing findings and discover that a subset of cortical OPCs are prematurely senescent in the trisomic mouse brain. We show that treatment of Ts65Dn mice with the anti-senescence flavonoid, fisetin, has restorative effects on cortical OPCs, including reducing senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) activity, increasing proliferation and progenitor abundance, restoring microglia homeostasis, and improving contextual fear memory. In sum, this work identifies novel cellular mechanisms that drive chronic neuroinflammation and cognitive dysfunction in the Ts65Dn mouse model of DS.

Materials and Methods

Mice

All animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Canadian Council of Animal Care policies. Ts65Dn (B6EiC3Sn.BLiA-Ts(1716)65Dn/DnJ, RRID:IMSR_JAX:005252) and euploid controls (B6EiC3Sn.BLiAF1/J, RRID:IMSR_JAX:003647) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Ts65Dn mice were bred with euploid controls as recommended by The Jackson Laboratory. The animals were kept in 12/12 h light/dark cycles with free access to food and chow, and bred at The Center for Phenogenomics in Toronto (ON, Canada). For all studies, the sex of the mice is listed in the respective figure legend. The specific ages of each animal for each experiment are documented in the respective results, method details, and/or figure legends of the study. A cohort of Ts65Dn mice, designated for the Ts65Dn+fisetin condition, received a custom diet produced by Envigo, containing 500 ppm fisetin (Indofine Chemical, catalog #528-48-3) in the chow, starting at three months of age, until euthanasia at six months. Quantitative PCR (qPCR) was performed on genomic DNA extracted from tail tips of all mice to confirm individual genotype. The primers used are as follows: 11,981 mutant A, GTGGCAAGA GACTCAAAT TCAAC; 11,982 mutant A, TGGCTTATT ATTATCAGG GCATTT; OIMR7338 IC forward, CTAGGCCAC AGAATTGAA AGATCT; OIMR7338 IC reverse, GTAGGTGGA AATTCTAGC ATCATCC.

Tissue preparation for immunostaining

For immunostaining, Ts65Dn, fisetin-treated (Ts65Dn+fisetin), and euploid control (CTL) mice were perfused intra-aortically with a solution of 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA; Electron Microscopy Sciences, catalog #15710) while under isoflurane anesthesia (for untreated Ts65Dn and CTL groups at three months: n = 4 per condition; for Ts65Dn, Ts65Dn+fisetin, and CTL groups at six months: n = 3 per condition). Brains were removed and postfixed in 4% PFA at 4°C overnight, then washed 3× for 20 min in 1× PBS before cryoprotection in a 30% sucrose solution at 4°C for 3–4 d. The tissue was embedded in optimal cutting temperature (O.C.T.) compound (Fisher Scientific, catalog #23-730-571) and allowed to solidify at −80°C. Brains were then sliced coronally at 20 μm on a cryostat, mounted onto 0.5% gelatin-coated superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific, catalog #22-037-246) and stored at −80°C long term; three sequential sections were collected per slide.

Senescence-associated-β-galactosidase (SA-β-gal) staining

SA-β-gal activity was determined on coronal brain sections using a SA-β-gal kit (Cell Signaling, catalog #9860) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, sections were incubated at 37°C for 20 min, washed 3× in 1× PBS for 10 min each, fixed for 10 min at room temperature using the kit’s fixative agent, and stained overnight for 16 h using the SA-β-gal staining solution (pH 5.9–6.1, prepared according to kit instructions) in a sealed container placed in a CO2-free incubator. The sections were then washed in 1× PBS for 10 min and double-distilled water (DDW) for 5 min before coverslip-mounting with mounting medium (ThermoFisher, catalog #TA030FM).

Immunohistochemistry (IHC)

When coupled with SA-β-gal staining, the above protocol was followed with several additional steps. After washing in 1× PBS and deionized water, slides were washed in TBS (0.1 m Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 0.15 m NaCl in DDW) for 10 min, permeabilized with TBS-Tx (0.4% Triton X-100 in TBS) 2× for 10 min each, and blocked in blocking buffer (5% BSA, 0.4% Triton X-100 in TBS) at room temperature for 1 h. The primary antibody was diluted in blocking buffer and applied to the slide, incubated in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. Staining was subsequently performed using HRP/DAB Detection kits (Abcam, catalog #Ab64261 or Ab64259) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with minor adaptations. Briefly, sections were washed 4× in PBS-T (0.2% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS), incubated with biotinylated goat anti-polyvalent for 10 min, washed 4× in PBS-T, incubated with streptavidin peroxidase for 10 min, washed 4× in PBS-T, incubated with DAB mixture (2% DAB chromogen in DAB substrate) for 8–10 min, washed 4× in 1× PBS, and mounted with mounting medium (ThermoFisher, catalog #TA030FM).

Immunofluorescence (IF)

Sections were incubated at 37°C for 20 min, washed 3× in 1× PBS for 10 min each, and blocked in blocking buffer (10% BSA, 6% NDS, 0.3% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS) at room temperature for 1 h. The primary antibody was diluted in blocking buffer and applied to the slide, incubated in a humidified chamber overnight at 4°C. Sections were subsequently washed 3× in PBS-T (0.1% Triton X-100 in 1× PBS) for 10 min, and incubated with secondary antibody diluted in PBS-T for 1 h at room temperature. After incubation, the sections were washed in 1× PBS and mounted with Fluoromount mounting medium (ThermoFisher, catalog #00-4959-52).

Antigen retrieval (AR)

When necessary, AR was coupled with the above IF protocol following the first round of 3 × 10 min 1× PBS washes. Sodium citrate buffer (10 mm sodium citrate, 0.05% Tween 20, pH 6.0) was created according to Abcam’s protocol for heat-induced epitope retrieval. Slides were completely submerged in the buffer and heated for 20 min at full power in a domestic microwave once the solution reached boiling point. When 20 min elapsed, the heating vessel was removed and cooled in a bath of cold water until it reached room temperature. Slides were then washed 3× in 1× PBS for 10 min each and the aforementioned IF protocol was resumed beginning with 1 h incubation in blocking buffer.

Antibody concentrations

The primary antibodies used for immunostaining were goat anti-PDGFRA (1:250, R&D Systems, catalog #AF1062), rabbit anti-PDGFRA (1:250, Abcam, catalog #Ab203491), rabbit anti-OLIG2 (1:500, Abcam, catalog #Ab136253), mouse anti-CC1 (1:100, CalBioChem, catalog #OP80), rabbit anti-IBA1 (1:500, Wako, catalog #019-19741), rabbit anti-LMNB1 (1:1000, Abcam; used with AR, catalog #Ab16048), mouse anti-NEUN (1:500, Millipore, catalog #Ab377), mouse anti-AQP4 (1:100, Abcam, catalog #Ab9512), rabbit anti-KI67 (1:200, Abcam, catalog #Ab16667), rat anti-CD68 (1:400, Abcam, catalog #Ab53444), rabbit anti-MBP (1:250, Abcam, catalog #Ab40390). The secondary antibodies used for immunostaining were Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit IgG (1:500, ThermoFisher, catalog #A-11034), Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-mouse IgG (1:500, ThermoFisher, catalog #A-21422), Alexa Fluor 555 goat anti-rat IgG (1:500, ThermoFisher, catalog #A-21434), Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-goat (1:500, ThermoFisher, catalog #A-11055), Alexa Fluor 555 donkey anti-mouse IgG (1:500, ThermoFisher, catalog #A-31570), and Alexa Fluor 647 donkey anti-rabbit (1:500, ThermoFisher, catalog #A-31573).

Quantitative PCR (qPCR) analysis

mRNA expression levels of Mbp were measured by qPCR analysis. qPCR was performed on six-month tissue for Ts65Dn, Ts65Dn+fisetin, and CTL groups (n = 4 per condition). In brief, cortical tissue was lysed in 1 ml of TRIzol (ThermoFisher, catalog #15596026) and total RNA was isolated according to the manufacturer’s guidelines. cDNA synthesis was performed using 2 μg of total RNA and the iScript cRNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad, catalog #1708890). qPCR was performed using the Brilliant III ultra-Fast SYBR green qPCR master mix (Agilent Technologies, catalog #600882) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were normalized to Gapdh. The primers used are as follows: Mbp forward, GGC ATC ACA GAA GAG ACC CTC; Mbp reverse, GCA CCC CTG TCA CCG CTA AAG; Gapdh forward, GGG TGT GAA CCA CGA GAA ATA; Gapdh reverse, CTG TGG TCA TGA GCC CTT C. All primers were ordered via Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT).

Slide scanner imaging

Whole slide scans were acquired on a 3DHistech Pannoramic 250 Flash III Slide Scanner using a Zeiss 40 × 0.95 NA objective. The instrument was operated in extended focus mode (seven focal planes spanning a 5-μm axial distance) to capture the entire cell volume across each tissue section. Maximum intensity projections of all the z-planes are shown in the specified figures. One image was captured per slide. The microscope is housed in the Imaging Facility at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (ON, Canada). Digital images obtained from the Slide Scanner were imported to the HALO Image Analysis Platform (Indica Labs, v.3.5.3577.173) for subsequent analysis.

Epifluorescence imaging

Fluorescence images were captured with a 40× water-immersion or 63× oil-immersion objective on a Zeiss Axio Imager.M2 upright microscope. The microscope is housed in the laboratory at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (ON, Canada). Images were evenly captured across Layers II–VI (L2–L6) of the motor and somatosensory cortex on each tissue sample, for a total of 18 images per mouse. All imaging was captured using the Zen Blue software (Carl Zeiss Meditec, v3.3.89.0000). Digital images obtained from the Zeiss Axio Imager.M2 were then imported to the Volocity 3D Image Analysis Software (PerkinElmer, v6.3.1) for subsequent analysis.

Confocal imaging

High magnification brightfield images for OLIG2/SA-β-gal and PDGFRA/SA-β-gal analysis were acquired using a 40×/1.3 objective on Nikon Eclipse Ti2-E equipped with a Nikon DS10 color camera, running NIS Elements acquisition software. The microscope is housed in the Imaging Facility at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (ON, Canada).

Quantification of SA-β-gal activity

Two regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn across L2–L6 of the motor and somatosensory cortex on each tissue sample, for a total of six ROIs of equivalent area per mouse. The Multiplex IHC (v3.1.4) algorithm on HALO was used for all cell type specific SA-β-gal activity quantification and was optimized to detect cell type specific positivity based on the respective DAB staining. An ROI of ∼3-mm2 spanning the motor and somatosensory cortical regions was drawn for quantification of cell counts in the cortex across all biological replicates. A cytoplasmic radius was then measured and the percentage of cells that exhibited SA-β-gal positivity within the nuclear or associated cytoplasmic compartments was calculated.

Quantification of PDGFRA/CC1/OLIG2 and PDGFRA/KI67 co-localization

The HighPlex FL (v4.1.3) algorithm on HALO was used for quantification of PDGFRA/OLIG2/CC1 and KI67/PDGFRA colocalization positivity. The module was optimized to detect OLIG2 or PDGFRA-positive nuclear positivity for quantification of PDGFRA/CC1/OLIG2 and KI67/PDGFRA cell counts, respectively. A cytoplasmic radius was measured and the percentage of cells that exhibited concomitant nuclear or cytoplasmic compartment positivity for other markers was calculated accordingly. Thresholds for nuclear and cytoplasmic positivity were calibrated for each marker set and slide. An ROI of ∼3-mm2 spanning L2–L6 of the motor and somatosensory cortical regions was drawn for quantification of cell counts in the cortex; an ROI of ∼1 mm2 was drawn medially along the corpus callosum (CC) for quantification of cell counts in the CC for all biological replicates.

Quantification of nuclear LMNB1 fluorescence intensity

A total of 100 PDGFRA-positive cells were imaged from Ts65Dn, Ts65Dn+fisetin, or CTL mice (n = 3 per condition) across the motor and somatosensory cortex. Each image contained at least one PDGFRA-positive cell. PDGFRA-positive cells were manually selected and individually assessed for nuclear LMNB1 colocalization within the imaged plane. The threshold for positive LMNB1 staining was set to ∼1 SD from the mean across all sampled images. Normalized LMNB1 intensity was then calculated for each PDGFRA-positive cell by dividing the obtained LMNB1 intensity value by the total surface area of the associated cell.

Quantification of MBP fluorescence intensity

Myelin intensity thresholds were established based on parameters that allowed the maximum capture of MBP stain across all images for all sampled conditions. Normalized MBP intensity was then calculated for each image by dividing the obtained MBP intensity value by the total surface area of all myelin sheaths within the imaged frame. All images were captured across L2–L6 of the motor and somatosensory cortex.

Immunostaining statistical analyses

Statistical significance was evaluated using a two-tailed Student’s t test for all experiments evaluating comparisons between three-month Ts65Dn and CTL mice, or using a one-way ANOVA followed by a post hoc Tukey’s test for all experiments evaluating comparisons between Ts65Dn, Ts65Dn+fisetin, and CTL genotypes. The statistical analyses were performed on R (The R Project for Statistical Computing, RRID:SCR_001905). Error bars displayed on graphs denote the SD from the mean.

Tissue preparation for single-nucleus sequencing

For single-nucleus sequencing, primary somatosensory cortical tissue from six-month Ts65Dn and CTL (n = 3 per condition) mice were microdissected and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. Frozen tissue was thawed in 1 ml buffer HB (0.25 m sucrose, 25 mm KCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 20 mm Tricine-KOH pH 7.8, 0.15 mm spermine tetrahydrochloride, 0.5 mm spermidine trihydrochloride, 1 mm DTT). The tissue was transferred to a 7-ml dounce; 340 μl 5% IGEPAL CA-630 (Sigma-Aldrich) and 4 ml HB were added to the tissue and the tissue was homogenized with a tight pestle 10–15 times. The sample was transferred to a 15-ml tube and total solution brought to 10 ml with 50% iodixanol; 1 ml 30% iodixanol was layered on top of 1 ml 40% iodixanol in a separate Corex tube (ThermoFisher). The 9 ml sample was layered on top of the iodixanol cushion. The sample was spun at 10,000 × g for 18 min; 1 ml of sample at the 30–40% iodixanol interface was collected. After counting nuclei with a hemocytometer, the sample was diluted to 100,000 nuclei/ml with 30% iodixanol (with RNasin) and subjected to single nuclear droplet encapsulation with the 10× Chromium platform (10× Genomics). Libraries were sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 S4 platform at The Center for Applied Genomics (TCAG) at The Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto (ON, Canada).

Single-nucleus RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) bioinformatics workflow

Raw reads were converted to FASTQs, mapped to the mm10 mouse reference genome (Ensembl 93), and demultiplexed to generate a per-cell count matrix using the CellRanger pipeline (10× Genomics). Cells from all snRNA-seq experiments were combined into a single Seurat object dataset and filtered through the Seurat pipeline (v4.3.0; Hao et al., 2021) using default parameters. Low-quality cells with unique feature counts >2500 or <200 and >5% mitochondrial counts were excluded. The data was then log-normalized and scaled by the default scale factor of 10,000. The top variable features and principal components were then calculated using default values, returning 2000 features for the dataset. A second round of scaling shifted the expression of each gene so that mean expression across cells was 0 and variance across cells was 1. Linear dimensional reduction was performed and the dimensionality of the dataset was determined. Clustering was performed by constructing a KNN graph and applying the Louvain algorithm. Dimensional reduction was performed with default values for uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP) and individual clusters were annotated based on expression of lineage-specific markers.

Differential gene expression (DGE) analysis

Differential gene expression (DGE) between the two conditions (Ts65Dn vs CTL) for each cell type was assessed with the Seurat FindMarkers function using default MAST parameters and a log-fold change (logFC) threshold of 0.1. Benjamini–Hochberg corrected p-values were used for significance. Genes with false discovery rate (FDR) < 0.05 met statistical criteria for significant differential expression. Major cell type annotations were assigned to clusters by manual inspection of canonical marker gene signals and confirmed through scPred’s reference-based mapping approach (v1.9.2; Alquicira-Hernandez et al., 2019) using the Allen Brain Atlas whole cortex and hippocampus 10× dataset (Yao et al., 2021).

Ligand-receptor (LR) analysis

Cell-cell communication between all cortical cell types was identified based on ligand-receptor (LR) analysis conducted using CellChat (v1.6.0; S. Jin et al., 2021). Default parameters between the two conditions (Ts65Dn vs CTL) were employed. CellChat infers biologically significant LR pairs by assigning each interaction with a probability value and peforming a permutation test, in which p < 0.05 is considered significant.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA)

GSEA was conducted using clusterProfiler (v3.8; Yu et al., 2012) and the Reactome gene set (Gillespie et al., 2022) for each cell type on a ranked list of all the genes for which log2FC between conditions (Ts65Dn vs CTL) values were available. Gene sets with FDR < 0.05 were considered significantly enriched, and normalized enrichment scores (NES) were used to assess the directionality of enrichment. The previously published SenMayo gene set (Saul et al., 2022) was used to perform transcriptomic GSEA for the senescence-associated gene signature and clusterProfiler was used to compute an NES for each cell type. Statistically significant enrichment for the gene set was determined by cell types showing FDR < 0.05. All FDR values were calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

Single-nucleus ATAC-sequencing (snATAC-seq) bioinformatics workflow

Cells from all snATAC-seq experiments were combined into a single Seurat object dataset and filtered through the Signac pipeline (v1.10.0; Stuart et al., 2021) using default parameters. Low-quality cells were removed using filters for peak region fragments <100,000, percent reads in peaks >40, blacklist site ratio <0.025, nucleosome signal <4, and transcriptional start site (TSS) enrichment score >2. The data was then normalized via singular value decomposition (SVD) of the term frequency-inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) matrix and all identified variable features were used for linear dimensional reduction. Remaining preprocessing and dimensionality reduction was performed according to Signac recommendations using default parameters. A gene activity matrix was constructed by counting snATAC-seq peaks within the gene body and 2 kb upstream of the transcriptional start site (TSS) using protein-coding genes annotated in the Ensembl database. UMAP dimensionality reduction was performed with default values.

Differential accessibility analysis

Differentially accessible regions (DARs) between the two conditions (Ts65Dn vs CTL) for each cell type were calculated with the Signac FindMarkers function using default MAST parameters and a log-fold change (logFC) threshold of 0.1 and n_count_peaks as a latent variable. Benjamini–Hochberg corrected p-values were used for significance. Peaks with FDR < 0.05 met statistical criteria for significant differential accessibility. Major cell type annotations were assigned to clusters through manual inspection of canonical marker gene signals and confirmed through label transfer using Seurat’s multimodal snRNA-seq to snATAC-seq integration pipeline. Integration showed 100% cluster label concordance between the two modalities.

Gene ontology (GO) analysis

Gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed for all enriched genes (FDR < 0.05) in each cell type using g:Profiler (v0.7.0; Raudvere et al., 2019) to identify overrepresentation for biological process (BP) and molecular function (MF) categories. Statistically significant enrichment for GO pathways was determined by cell types showing FDR < 0.05. All FDR values were calculated using the Benjamini–Hochberg method.

Transcription factor (TF) motif analysis

Transcription factor (TF) motif activity was estimated using the RunChromVAR wrapper in Signac. The positional weight matrix (PWM) was obtained from the JASPAR2020 database (Fornes et al., 2020). Differential motif activity was assessed using log2fold change (log2FC) threshold of 0.1 with a 0 pseudocount. Motifs with FDR < 0.05 met statistical criteria for significant binding activity.

Fear conditioning

Behavioral testing was performed at The Centre for Phenogenomics (TCP) in Toronto (ON, Canada). Animals were left in their home cage inside the testing room, anteroom or on the day-rack at least 30 min before testing. Mice were then transferred into individual testing chambers with grid floors. After 120 s without any stimulus (which gives the mouse time to get used to the surrounding) a 30 s, 3600 kHz 95-dB audible tone (CS, conditioned stimulus) followed and was co-terminated with a 2-s foot shock of 0.75 mA (US, unconditioned stimulus). Following the shock, mice spent another 30 s in the chamber before removal. Concomitantly, the animals associated the background context cues with the CS (conditioning). Mice were then returned to their holding room where they spent 24 h before being returned to the testing room for additional screening. They were placed back into the same testing chambers for 300 s without changes to the context/interior and no stimuli applied. After conditioning, the CS or the spatial context elicited, in the absence of the US, a central state of fear that was expressed as reduced locomotor activity or total lack of movement (freezing). The time spent immobile was used as a measure of learning/memory performance. This phase was followed by a 2 h break, which mice spent in their home cage before being returned to the testing chamber with a changed context. The grid floor was covered with a plastic sheet, the ceiling was changed from a square to triangular shape, the olfactory cues were changed, and the noise levels were reduced. Mice spent 180 s in this novel environment before a 180 s 3600 kHz 95-dB audible tone (no foot shock) was played again. Following this phase animals, were placed back into their home cage and the test was completed. Clidox 1:5:1 and 70% EtOH solutions were used to disinfect surfaces between testing mice from different cages.

Replicates

All immunostaining analyses were performed on at least three different brains each. All single-nucleus sequencing analyses were performed on three different brains each. All behavioral analyses were performed on at least eight different mice each. Additional details of the statistical analyses can be found in the detailed descriptions of the immunostaining and computational methods above and, where relevant, in the results and the figures legends. For all analyses, n refers to number of animals analyzed.

Data availability

Sequencing data have been deposited in GEO under accession code GSE225554. All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in the manuscript and supporting files. The custom code used for this manuscript is available on GitHub at https://github.com/KalishLab/Ts65Dn_OPC_Senescence.

Results

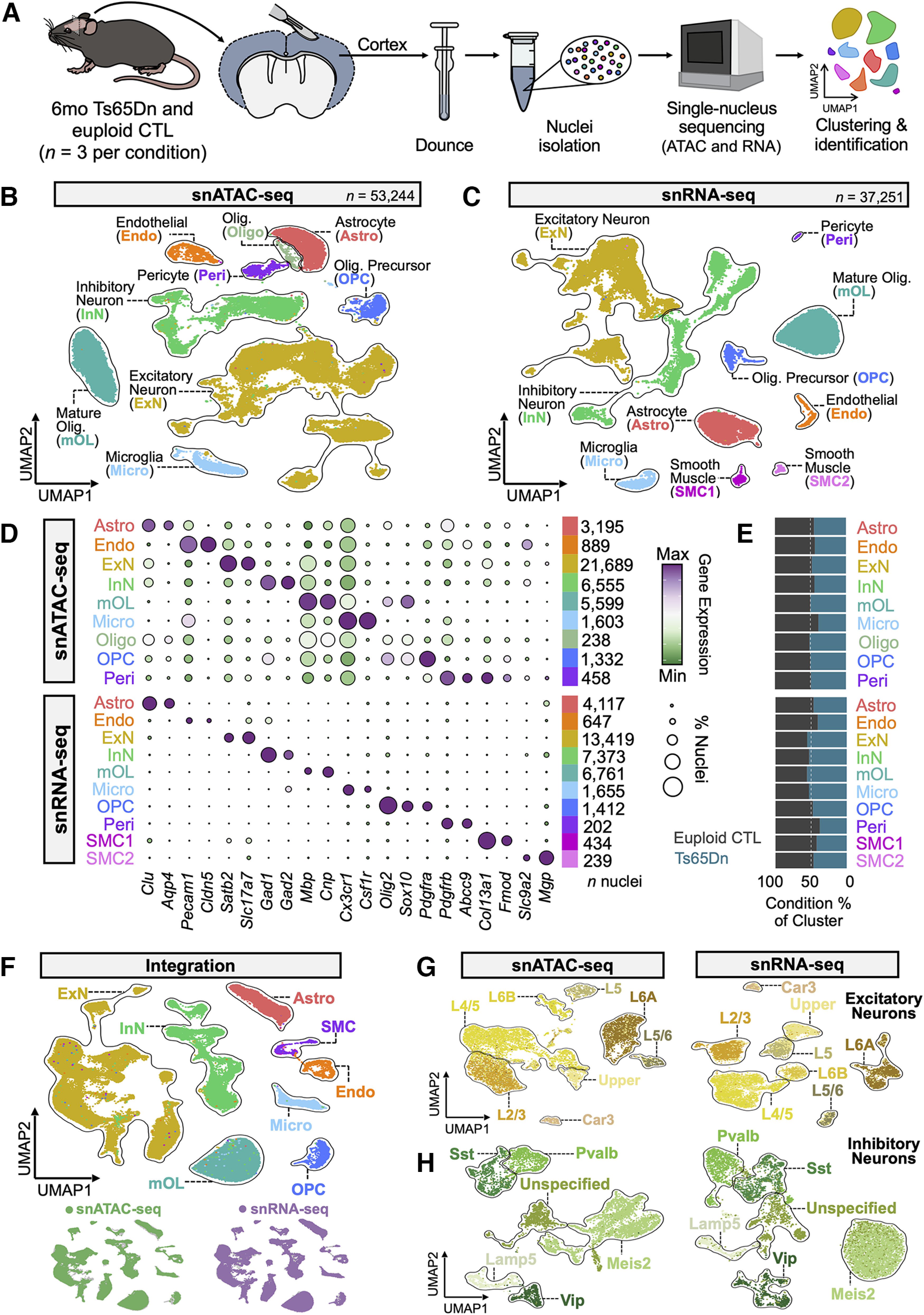

Characterization of cell types in the adult Ts65Dn cortex using multiomic single-nucleus sequencing

To identify cellular programs underlying age-related cognitive decline in trisomy, we performed droplet-based single-nucleus ATAC (snATAC-seq) and RNA-sequencing (snRNA-seq) on the six-month Ts65Dn and euploid control (CTL) littermate mouse cortex using the 10× Genomics platform (Fig. 1A; Materials and Methods; G.X.Y. Zheng et al., 2017; Satpathy et al., 2019). Nuclei from each biological sample were split into two fractions to capture and analyze both the mRNA and accessible chromatin: one part was used for snATAC-seq and the other was used for snRNA-seq. Ts65Dn mice and littermate controls were selected from three separate litters. This study was restricted to the cortex, the outermost portion of the brain, because of its involvement in cognition and higher-order processing (Shipp, 2007), and the associated structural and functional deficits known to occur in DS (N.R. Lee et al., 2016; Utagawa et al., 2022). We analyzed the transcriptomes and epigenomes from each dataset using the well-established Seurat (Hao et al., 2021) and Signac (Stuart et al., 2021) pipelines, respectively (Materials and Methods). Data was quality control (QC) filtered to remove clusters likely to be of low quality resulting from debris, doublets, or dead cells, and was subsequently normalized using default parameters. After QC processing, we profiled a total of 53,244 nuclei for snATAC-seq and 37,251 nuclei for snRNA-seq (Extended Data Fig. 1-1).

Figure 1.

Multimodal single-nucleus sequencing of the Ts65Dn mouse cortex identifies all major neuronal and non-neuronal cell types. A, Schematic representation of biological samples, cortical dissection, tissue processing and sequencing workflow for snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq from six months Ts65Dn and euploid control (CTL) mice (n = 3 male mice per condition). B, UMAP visualization of the snATAC-seq dataset, where each dot represents a single nucleus, for a total of 53,244 nuclei. UMAP plots are generated from combined replicates across Ts65Dn and CTL conditions. Each cluster is colored by cell type: Astro, astrocytes; Endo, endothelial cells; ExN, excitatory neurons; InN, inhibitory neurons; mOL, mature oligodendrocytes; Micro, microglia; Oligo, oligodendrocytes; OPC, oligodendrocyte precursor cells; Peri, pericytes; SMC1/2, smooth muscle cells. C, As in B, but a visualization of the snRNA-seq dataset, containing a total of 37,251 nuclei. D, Dotplot of snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq datasets showing gene expression or gene accessibility patterns, respectively, with several key canonical marker genes used for cluster identification. The diameter of the dot corresponds to the proportion of nuclei expressing or exhibiting accessibility of the indicated gene, and the color of the dot corresponds to the average expression or accessibility of the gene relative to all cell types. The number of nuclei assigned to each cell type are indicated. E, Barplot depicting the fraction of nuclei per cell type by condition. F, UMAP visualization of multi-omic integration of snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq datasets colored by cell type assignment. Beneath are UMAPs of the integration colored by originating dataset. G, UMAP visualization of excitatory neuron (ExN) subsets as extracted from snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq datasets. Each cluster is colored by cell type: Car3, Car3-expressing excitatory neurons; L2/3, cortical Layers II -III; L4/5, cortical Layers IV -V; L5, cortical Layer V; L5/6, cortical Layers V -VI; L6A/B, cortical Layer VI excitatory neuron subsets; Upper, mixed upper layer (II -IV) excitatory neurons. H, As in G, but a visualization of inhibitory neuron (InN) subsets. Each cluster is colored by cell type: Lamp5, Lamp5-expressing interneurons; Meis2, Meis2-expressing interneurons; Pvalb, parvalbumin-expressing interneurons; Sst, somatostatin-expressing interneurons; Vip, vasoactive intestinal peptide-expressing interneurons; Unspecified, interneurons of unspecified classification. See Extended Data Figure 1-1 for quality control (QC) metrics used in the initial processing of snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq data.

Quality control (QC) metrics for multiomic single-nucleus data and integration of snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq data for neuronal subsets, related to Figure 1. A, Quality control (QC) metrics for snATAC-seq data, including the percentage of reads in peaks, the number of peak region fragments, transcription start site (TSS) enrichment, blacklist ratio, and nucleosome signal per replicate from six-month Ts65Dn and euploid control (CTL) mice (n = 3 male mice per condition). B, As in A, but depicting QC metrics for snRNA-seq data, including the number of features, total transcript counts, and percent mitochondrial content per replicate. C, UMAP visualization of multiomic integration of snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq datasets colored by originating dataset for the excitatory neuron (ExN) subset. D, As in C, but depicting multiomic integration for the inhibitory neuron (InN) subset. Download Figure 1-1, TIF file (2.2MB, tif) .

Genes with high variance were used to compute principal components for projecting and clustering cell populations with similar molecular signatures. Unsupervised clustering through Leiden clustering and plotting via uniform manifold approximation and projection (UMAP; Materials and Methods) dimensionality reduction revealed 10 major cell classes across the snATAC-seq and snRNA-seq datasets: astrocytes (Astro), excitatory neurons (ExN), inhibitory neurons (InN), mature oligodendrocytes (mOL), microglia (Micro), oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC), oligodendrocyte lineage cells (Oligo), endothelial cells (Endo), pericytes (Peri), and smooth muscle cells (SMC; Fig. 1B). Cell types were assigned based on a combination of canonical marker gene expression (Fig. 1C) and confirmed through a machine learning reference-based mapping approach (scPred; Materials and Methods; Alquicira-Hernandez et al., 2019) using the Allen Brain Atlas whole cortex and hippocampus 10× Genomics dataset (Materials and Methods; Yao et al., 2021). Integration and label transfer (Materials and Methods) between snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq further confirmed cell population assignments and demonstrated strong concordance between the two modalities, with cell types identified in either platform grouping together in the integrated UMAP space (Fig. 1D). All major cell types were present in both conditions, with high transcriptomic and epigenetic overlap between genotypes.

The ExN and InN clusters were proportionally the largest by number out of all identified cell type clusters, consistent with previous reports that neurons are the most numerous cell type in the cortex (Keller et al., 2018). To further subcategorize heterogeneous neuronal populations, we performed a second level of hierarchical clustering on ExNs and InNs to identify distinct subpopulations of each neuron class (Fig. 1E). Again, using the scPred algorithm on the snRNA-seq dataset, we identified clusters spanning five cortical layers (L2–L6), a distinct Car3+ population of ExNs, as well as five subpopulations of InNs, all with distinct transcriptional signatures. Integration of snRNA-seq and snATAC-seq neuronal subclusters revealed corresponding ExN cortical layer and InN subpopulations within the snATAC-seq dataset (Extended Data Fig. 1-1). Overall, this analysis transcriptionally and epigenetically identified all major neuronal and non-neuronal cell types and subtypes across the murine cortex.

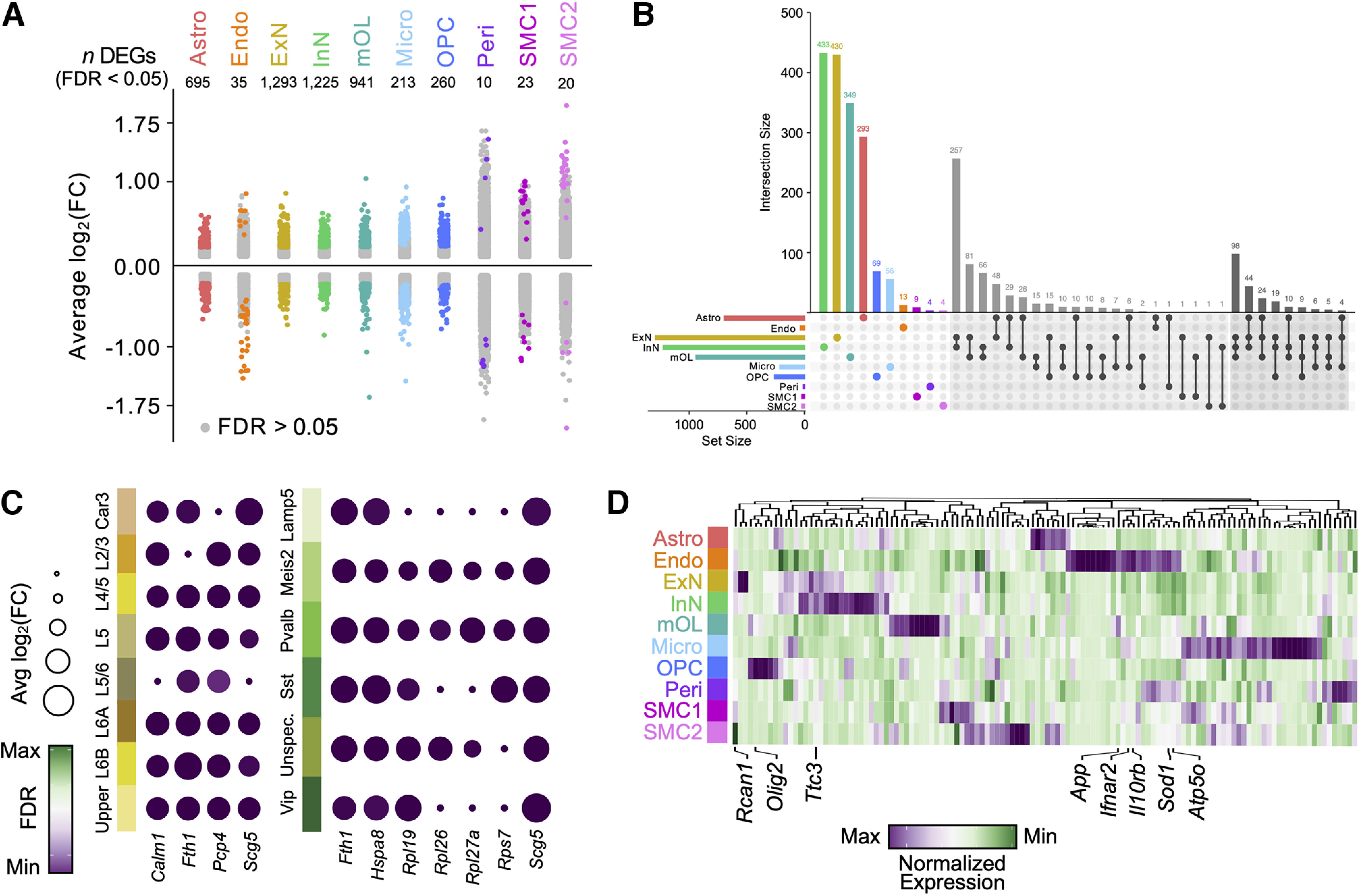

Identification of cell type-specific trisomy-associated transcriptomic changes in the Ts65Dn cortex

To identify transcriptional signatures of trisomy-associated cognitive decline, we performed cell type-specific differential gene expression (DGE) between Ts65Dn and euploid CTL mice (Materials and Methods). We used differentially expressed genes (DEGs) that met a false discovery rate (FDR) value < 0.05 to define statistically significant changes in transcript expression between Ts65Dn and CTL offspring. We identified a total of 4715 cell type-specific DEGs across all cell populations (Fig. 2A; Table 1), with 64.3% of DEGs upregulated (log2FC > 0) and 35.7% downregulated (log2FC < 0) in Ts65Dn. We found that 38% of the DEGs significantly altered by Ts65Dn trisomy were cell type specific, with the remaining 62% intersecting between two or more cell types (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

Transcriptionally distinct cellular subpopulations in Ts65Dn cortex. A, Strip plot displaying differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between Ts65Dn and CTL offspring at six months. Colored dots represent significant genes (FDR < 0.05) per cell type. The number of significant DEGs per cell type is indicated. The x-axis displays all major cortical cell types profiled through snRNA-seq. Data obtained from n = 3 biological replicates per condition. B, UpSet plot displaying the number of unique and shared DEGs across cell types, with unique genes colored based on cell type, and genes shared between two or three cell types indicated by black dots connected by lines according to shared origins. The histogram indicates the number of DEGs for each cell type, and the barplots show the number of significant DEGs (FDR < 0.05) per cell type. C, Dotplot of select differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within excitatory neuron (ExN) and inhibitory neuron (InN) subsets. Each row represents a neuronal subset population. Each column represents a gene. The color code represents the FDR, and the size of the dots represents the average log2fold change [avg log2(FC)] of gene expression between Ts65Dn and CTL mice. D, Hierarchically clustered heatmap of normalized gene expression for genes contained within the Ts65Dn chromosomal product. The plot displays gene activity across all cell types in snRNA-seq. Several genes of interest are indicated. Each column represents a cell type. The color code represents the row-normalized expression for each gene.

Table 1.

Top five genes enriched in each cortical cell type in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL

| Gene | FDR | log2(FC) | Cell type | Gene | FDR | log2(FC) | Cell type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scg5 | 1.66E-19 | 0.55 | Astro | Scg5 | 3.20E-09 | 0.86 | Micro |

| mt-Co3 | 3.08E-19 | 0.51 | Astro | Pcp4 | 1.87E-17 | 0.74 | Micro |

| Pcp4 | 3.56E-23 | 0.48 | Astro | Fmn1 | 5.78E-04 | 0.70 | Micro |

| Fth1 | 1.98E-28 | 0.47 | Astro | Hbb-bs | 1.36E-04 | 0.64 | Micro |

| mt-Co1 | 9.46E-10 | 0.46 | Astro | Rpl26 | 7.83E-06 | 0.60 | Micro |

| Nxpe2 | 1.55E-08 | 1.13 | Endo | Fth1 | 8.83E-13 | 0.73 | OPC |

| H2-K1 | 1.32E-04 | 0.78 | Endo | mt-Co1 | 3.23E-08 | 0.66 | OPC |

| Ly6a | 4.38E-02 | 0.60 | Endo | Ano3 | 4.03E-07 | 0.65 | OPC |

| Ccni | 1.03E-02 | 0.60 | Endo | mt-Nd4 | 1.21E-05 | 0.57 | OPC |

| Nxpe4 | 4.07E-02 | 0.60 | Endo | mt-Cytb | 1.01E-05 | 0.55 | OPC |

| mt-Co3 | 1.40E-234 | 0.79 | ExN | Adora2a | 2.35E-01 | 1.47 | Peri |

| Fth1 | 3.68E-196 | 0.64 | ExN | Tnfrsf21 | 2.58E-01 | 1.47 | Peri |

| mt-Co1 | 2.18E-136 | 0.64 | ExN | Nefl | 4.06E-02 | 1.38 | Peri |

| Pcp4 | 1.29E-125 | 0.57 | ExN | Arpc2 | 9.73E-02 | 1.36 | Peri |

| Calm1 | 2.77E-212 | 0.55 | ExN | Anp32b | 2.58E-01 | 1.31 | Peri |

| Scg5 | 5.85E-70 | 0.57 | InN | Sdc2 | 1.03E-02 | 0.92 | SMC1 |

| Gpr88 | 1.53E-24 | 0.51 | InN | Tuba4a | 1.03E-02 | 0.91 | SMC1 |

| Hsp90aa1 | 1.45E-63 | 0.49 | InN | Arpp19 | 1.03E-02 | 0.87 | SMC1 |

| Fth1 | 8.98E-71 | 0.49 | InN | Uqcrh | 4.07E-04 | 0.87 | SMC1 |

| Ckb | 5.74E-65 | 0.48 | InN | Tpt1 | 5.12E-03 | 0.82 | SMC1 |

| Spock1 | 1.01E-61 | 0.94 | mOL | mt-Co2 | 1.97E-06 | 1.74 | SMC2 |

| Fmn1 | 1.41E-22 | 0.66 | mOL | Pcp4 | 5.18E-09 | 1.34 | SMC2 |

| Hbb-bs | 6.47E-18 | 0.60 | mOL | mt-Co3 | 2.13E-04 | 1.24 | SMC2 |

| Pcp4 | 8.02E-49 | 0.58 | mOL | Rps20 | 3.17E-02 | 1.20 | SMC2 |

| Camk2n1 | 6.42E-19 | 0.53 | mOL | Scand1 | 6.83E-03 | 1.19 | SMC2 |

Listed are the top five genes [ranked by highest average log2(FC)] that are significantly differentially enriched in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL as detected via snRNA-seq. Shown are fold-change (FC) values of the average expression for each gene and the false discovery rate (FDR) between Ts65Dn and CTL cells. Each cell type is listed in the final column: Astro, astrocytes; Endo, endothelial cells; ExN, excitatory neurons; InN, inhibitory neurons; mOL, mature oligodendrocytes; Micro, microglia; OPC, oligodendrocyte precursor cells; Peri, pericytes; SMC1/2, smooth muscle cells.

ExN and InN populations were the most numerous of all identified cell types, and accordingly had the highest number of total and shared DEGs (Fig. 2B). Several genes were found to be overexpressed in a majority of ExN subclusters (at least five out of eight; Fig. 2C; Table 2), including Calm1, an essential regulator of early neuronal migration (Kobayashi et al., 2015), Fth1, a ferroxidase enzyme that supports iron detoxification as part of the neuronal antioxidant defense system (Mukherjee et al., 2020), Scg5, a secretory chaperone that co-localizes with aggregated proteins in neurodegenerative diseases (Chaplot et al., 2020), and Pcp4, a modulator of calcium signaling that is triplicated in DS (Mouton-Liger et al., 2011). A similar trend was observed in InNs, with several genes showing overexpression across multiple subtype clusters (at least four out of six; Fig. 2C), including the aforementioned Fth1 and Scg5, as well as Hspa8, a molecular chaperone whose expression increases during injury and activates proinflammatory responses through NF-κB signaling (Mi et al., 2021). Several large (Rpl) and small (Rps) ribosomal subunit genes, including Rpl19/26/27a and Rps7 were also overexpressed in several InN subtypes, suggesting a disruption in translation-associated ribosomal machinery. These data support existing findings of metabolic (Izzo et al., 2018; Dierssen et al., 2020; Sarver et al., 2023), inflammatory (Wilcock, 2012; Flores-Aguilar et al., 2020), transcriptional (Gardiner, 2006), and translational (Sullivan et al., 2016; Aivazidis et al., 2017) dysregulation in the trisomic brain.

Table 2.

Top five genes enriched in each excitatory (ExN) and inhibitory (InN) neuronal subtype in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL

| Gene | FDR | log2(FC) | Cell type | Gene | FDR | log2(FC) | Cell type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Scg5 | 1.49E-03 | 0.92 | Car3 | Fth1 | 1.54E-47 | 0.64 | Upper |

| Bex2 | 1.52E-03 | 0.86 | Car3 | Pcp4 | 1.27E-33 | 0.58 | Upper |

| Rtn1 | 1.13E-08 | 0.84 | Car3 | Calm1 | 6.98E-47 | 0.55 | Upper |

| Cck | 7.34E-03 | 0.79 | Car3 | Scg5 | 2.40E-31 | 0.55 | Upper |

| Tomm20 | 3.67E-03 | 0.73 | Car3 | Cmss1 | 6.98E-47 | 0.48 | Upper |

| Pcp4 | 5.10E-26 | 0.68 | L2/3 | Cck | 4.04E-02 | 0.71 | Lamp2 |

| Calm1 | 8.56E-42 | 0.61 | L2/3 | Pcp4 | 7.90E-04 | 0.69 | Lamp2 |

| Fth1 | 2.51E-25 | 0.59 | L2/3 | Scg5 | 8.38E-03 | 0.67 | Lamp2 |

| Cd81 | 4.06E-18 | 0.58 | L2/3 | Tac1 | 1.61E-02 | 0.67 | Lamp2 |

| Lama2 | 2.33E-04 | 0.56 | L2/3 | Vdac2 | 1.73E-02 | 0.63 | Lamp2 |

| Fth1 | 1.65E-46 | 0.61 | L4/5 | Scg5 | 3.52E-31 | 0.59 | Meis2 |

| Pcp4 | 1.16E-32 | 0.58 | L4/5 | Junb | 2.23E-14 | 0.57 | Meis2 |

| Camk2n1 | 9.50E-29 | 0.54 | L4/5 | Gpr88 | 2.90E-15 | 0.48 | Meis2 |

| Scg5 | 7.07E-30 | 0.52 | L4/5 | Ckb | 1.89E-34 | 0.46 | Meis2 |

| Pld5 | 3.36E-18 | 0.52 | L4/5 | Actb | 2.12E-19 | 0.46 | Meis2 |

| Fth1 | 1.47E-13 | 0.71 | L5 | Pcp4 | 3.43E-11 | 0.67 | Pvalb |

| Camk2n1 | 1.09E-08 | 0.69 | L5 | Chchd2 | 2.53E-09 | 0.58 | Pvalb |

| Itm2c | 1.19E-09 | 0.65 | L5 | Fth1 | 1.00E-08 | 0.57 | Pvalb |

| Calm1 | 5.88E-15 | 0.63 | L5 | Scg5 | 2.60E-07 | 0.56 | Pvalb |

| Ubb | 1.75E-11 | 0.62 | L5 | Actg1 | 9.05E-09 | 0.56 | Pvalb |

| Eid1 | 3.14E-03 | 0.79 | L5/6 | Hspa8 | 5.86E-08 | 0.67 | Sst |

| Tuba1a | 2.50E-03 | 0.78 | L5/6 | Itm2c | 4.58E-06 | 0.63 | Sst |

| Lars2 | 3.83E-02 | 0.63 | L5/6 | Pcp4 | 3.38E-09 | 0.61 | Sst |

| Eef1g | 2.59E-02 | 0.62 | L5/6 | Fth1 | 1.31E-07 | 0.60 | Sst |

| Ndufa13 | 3.83E-02 | 0.61 | L5/6 | Scg5 | 1.16E-06 | 0.59 | Sst |

| Fth1 | 4.00E-37 | 0.71 | L6A | Gpr88 | 2.66E-08 | 0.56 | Unspec |

| Calm1 | 5.38E-40 | 0.62 | L6A | Cck | 2.94E-04 | 0.56 | Unspec |

| Atp6v0c | 1.97E-22 | 0.61 | L6A | Fth1 | 5.39E-17 | 0.54 | Unspec |

| Tubb5 | 3.17E-19 | 0.57 | L6A | Scg5 | 1.15E-10 | 0.52 | Unspec |

| Serinc1 | 4.53E-17 | 0.54 | L6A | Ckb | 1.12E-14 | 0.48 | Unspec |

| Fth1 | 1.32E-14 | 0.93 | L6B | Scg5 | 5.01E-08 | 0.72 | Vip |

| Rpl23 | 4.66E-05 | 0.68 | L6B | Vip | 7.19E-06 | 0.71 | Vip |

| Pgrmc1 | 6.01E-05 | 0.66 | L6B | H3f3b | 1.29E-07 | 0.63 | Vip |

| Rpl13 | 4.36E-07 | 0.62 | L6B | Lars2 | 3.34E-04 | 0.57 | Vip |

| Rpl26 | 9.65E-06 | 0.61 | L6B | Rpl19 | 5.11E-05 | 0.55 | Vip |

Listed are the top five genes [ranked by highest average log2(FC)] that are significantly differentially enriched in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL as detected via snRNA-seq. Shown are fold-change (FC) values of the average expression for each gene and the false discovery rate (FDR) between Ts65Dn and CTL cells. Each neuronal subtype is listed in the final column: Car3, Car3-expressing excitatory neurons; L2/3, cortical Layers II–III; L4/5, cortical Layers IV–V; L5, cortical Layer V; L5/6, cortical Layers V–VI; L6A/B, cortical Layer VI excitatory neuron subsets; Upper, mixed upper layer (II-IV) excitatory neurons; Lamp5, Lamp5-expressing interneurons; Meis2, Meis2-expressing interneurons; Pvalb, parvalbumin-expressing interneurons; Sst, somatostatin-expressing interneurons; Vip, vasoactive intestinal peptide-expressing interneurons; Unspecified, interneurons of unspecified classification.

All cell types exhibited upregulation of ∼10–20% of the genes expressed on the Ts65Dn trans-chromosome at the transcript level. However, not all Ts65Dn triplicated genes were equally altered in each cell type (Fig. 2D), consistent with previous analyses conducted on human iPSC-derived DS lines (Jose Luis Olmos-Serrano et al., 2016; Ponroy Bally et al., 2020) and single-cell analyses of DS mouse models (Lyle et al., 2004; Palmer et al., 2021; Sierra et al., 2021) that demonstrate limited overexpression of triplicated genes in trisomic cells. Only a few genes such as Atp5o or Sod1 were consistently found at higher levels in trisomic mice across various cell types, while others were overexpressed only in particular cell populations. For instance, Olig2, a key transcription factor (TF) that is triplicated in DS and activates the expression of myelin-associated genes in OL-lineage cells (Zhou et al., 2000; Zhou and Anderson, 2002), was selectively upregulated in trisomic OPCs by 15%; its overexpression is known to contribute to impaired OPC proliferation and differentiation in DS (Chakrabarti et al., 2010; Jose Luis Olmos-Serrano et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2019). Ttc3, an interactor of nerve growth factor (Ngf) that strongly inhibits neurite extension on overexpression (Berto et al., 2007), was upregulated in Ts65Dn ExNs by 13%. App, an integral membrane protein that is triplicated in DS and associated with increased amyloid-β (Aβ) aggregation and plaque deposition (O’Brien and Wong, 2011) showed enrichment of 8.6% and 11% in trisomic ExNs and microglia, respectively, and Rcan1, whose overexpression leads to neurofibrillary tangles (Ermak and Davies, 2013), was enriched in Ts65Dn endothelial cells by 16%. Lastly, pericytes and astrocytes exhibited an increase in Ifnar2 expression by 37% and 8.6%, respectively, while microglia showed an increased expression of Ifnar2 by 10% and Il10rb by 13%; the upregulated expression of these IFN receptors may contribute to the hyper-inflammatory milieu of the trisomic brain. The cell type-specific DEGs resulting from trisomy are consistent with many of the molecular disruptions in DS, including impaired myelinogenesis (Ábrahám et al., 2012; Flores-Aguilar et al., 2020), neuroinflammation (Wilcock, 2012; Flores-Aguilar et al., 2020), and neurogenesis (Stagni et al., 2018).

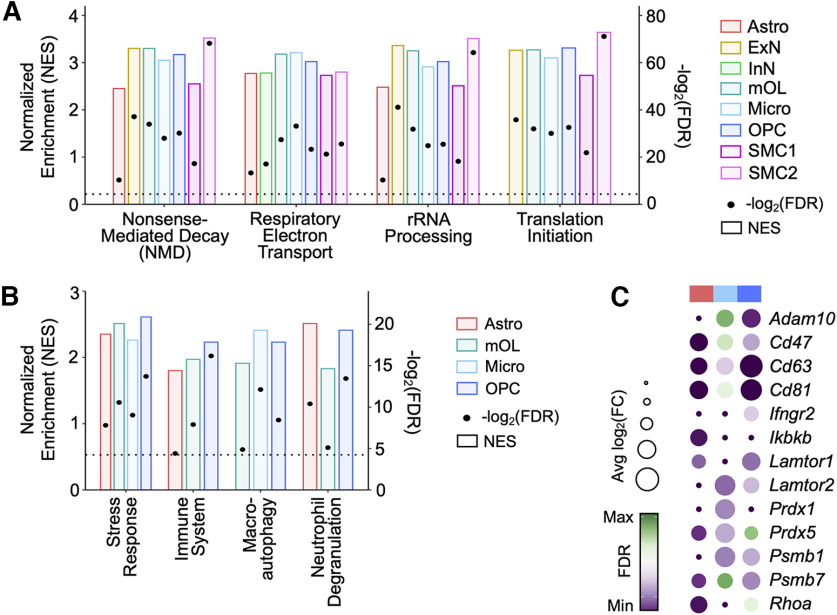

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) reveals dysregulation of several biological pathways in the mature Ts65Dn cortex

To identify functional pathways perturbed in Ts65Dn mice, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) using the Reactome repertoire of biological pathways (Gillespie et al., 2022) on ranked genes across all cell types (Materials and Methods). Of the top 10 enriched GSEA categories, four emerged as common processes altered in almost all cell types: ribosomal RNA (rRNA) processing, respiratory electron transport, nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), and translation initiation (Fig. 3A; Table 3). DS is characterized by an impairment in mitochondrial and ribosomal biogenesis, as well as integrated stress response (ISR)-mediated disruption in proteostasis (Aivazidis et al., 2017; Izzo et al., 2018; P.J. Zhu et al., 2019). Increased ribosomal and rRNA processing have been described in DS (Ravaioli et al., 2022) and premature aging (Buchwalter and Hetzer, 2017), and ribosome biogenesis has been shown to be regulated, and thus disrupted, in an ISR-dependent manner (Szaflarski et al., 2022). Consistent with this finding, we observed overexpression and dysregulation of over 30 large (Rpl) and small (Rps) ribosomal subunit genes and 15 mitochondrial (mt and cox) transcripts in the Ts65Dn brain. Genes involved in translation initiation, such as eIF4e, eIF3e, and eIF3a (Gingras et al., 1999; Aitken et al., 2016), were also found to have increased expression in all cortical Ts65Dn cells. Disrupted mitochondrial biogenesis in DS has previously been shown to impair oxidative phosphorylation (Bayona-Bafaluy et al., 2021), reduce mitochondrial energy production, and lower mitochondrial function (Helguera et al., 2013; Bayona-Bafaluy et al., 2021), together resulting in a hypoxia-like neuropathology (Pecze et al., 2020), further suggestive of a widespread metabolic dysregulation in the DS brain.

Figure 3.

Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) reveals disruption of several biological pathways in trisomic cells from the Ts65Dn cortex. A, Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of several Reactome biological pathways enriched across a majority of cortical cell types. The bars correspond to the left y-axis, displaying normalized enrichment score for each cell type by pathway and are colored by cell type identity. The dots correspond to the right y-axis, displaying -log2(FDR) for each cell type by pathway; the dashed horizontal line intercepts the right y-axis at 4.3, corresponding to an FDR = 0.05. All dots above this horizontal line are statistically significant. B, As in A, but depicting GSEA of several Reactome biological pathways enriched across astrocytes (Astro), mature oligodendrocytes (mOL), microglia (Micro), and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC). C, Dotplot of select differentially expressed genes (DEGs) within astrocytes (red), microglia (light blue), and OPCs (dark blue). Each column represents a cell population. Each row represents a gene. The color code represents the FDR, and the size of the dots represents the average log2fold change [avg log2(FC)] of gene expression between Ts65Dn and CTL.

Table 3.

Top three Ts65Dn enriched pathways in each cortical cell type identified via gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL

| GSEA pathway | FDR | NES | Cell type |

|---|---|---|---|

| The citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport | 3.51E-05 | 2.81 | Astro |

| Respiratory electron transport | 9.86E-05 | 2.77 | Astro |

| Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) | 1.54E-04 | 2.65 | Astro |

| Interferon signaling | 1.68E-02 | 2.25 | Endo |

| Interferon-α/β signaling | 2.89E-02 | 2.23 | Endo |

| Negative regulation of the PI3K/AKT network | 4.20E-02 | 2.10 | Endo |

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 4.60E-14 | 3.48 | ExN |

| Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) | 3.06E-13 | 3.43 | ExN |

| rRNA processing in the nucleolus and cytosol | 4.20E-13 | 3.36 | ExN |

| Metabolism | 8.47E-12 | 3.13 | InN |

| The citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport | 2.20E-08 | 3.04 | InN |

| Innate immune system | 3.87E-08 | 2.94 | InN |

| The citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport | 1.57E-11 | 3.43 | mOL |

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 1.39E-11 | 3.42 | mOL |

| Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) | 1.68E-11 | 3.39 | mOL |

| The citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport | 7.15E-12 | 3.24 | Micro |

| Respiratory electron transport | 1.06E-10 | 3.21 | Micro |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation | 9.00E-10 | 3.10 | Micro |

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 1.56E-10 | 3.34 | OPC |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation | 1.56E-10 | 3.31 | OPC |

| Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) | 3.06E-10 | 3.28 | OPC |

| Cellular response to heat stress | 5.14E-03 | 1.84 | Peri |

| Translation | 2.05E-03 | 1.72 | Peri |

| Cellular response to stimuli | 1.53E-03 | 1.71 | Peri |

| Formation of a pool of free 40S subunits | 1.63E-07 | 2.86 | SMC1 |

| Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) | 1.63E-07 | 2.84 | SMC1 |

| Eukaryotic translation initiation | 2.62E-07 | 2.73 | SMC1 |

| SRP-dependent cotranslational protein targeting to membrane | 7.11E-24 | 3.78 | SMC2 |

| Nonsense mediated decay (NMD) | 1.86E-23 | 3.74 | SMC2 |

| Formation of a pool of free 40S subunits | 9.16E-24 | 3.70 | SMC2 |

Listed are the top three pathways identified via GSEA analysis (ranked by lowest FDR value) that are significantly enriched in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL. All normalized enrichment scores (NES) are listed in the third column. Each cell type is listed in the final column and is abbreviated as described in Table 1.

DEGs in trisomic astrocytes, microglia, and OPCs also exhibited enrichment of GSEA categories including immune activation, neutrophil degranulation, macroautophagy, and stress response (Fig. 3B). In Ts65Dn astrocytes, we observed upregulation of Ikbkb, an activator of the NF-κB pathway (Israel, 2010), RhoA, a regulator of reactive astrocyte dynamics (Renault-Mihara and Okano, 2017), and inflammatory mediators Cd47, Cd63, and Cd81 (Hazrati et al., 2022; Fig. 3C). Ts65Dn OPCs likewise exhibited increased expression of several genes whose functions have been associated with immune activation, such as Adam10, an extracellular matrix (ECM) protein involved in inflammatory signaling (Pabois et al., 2014) and Ifngr2, an IFN receptor, whose upregulation induces increased immunomodulatory signaling (Schroder et al., 2004). Trisomic astrocytes, microglia, and OPCs also showed increased expression of several proteasome subunits including Psmb1/7 (Tanaka, 2009), as well as antioxidant enzymes Prdx1/5, whose functions are important during periods of oxidative stress (Park et al., 2016), and Lamtor1/2, which mediate cellular autophagy and survival responses to inflammation (Scheffler et al., 2014). Taken together, these transcriptional changes are consistent with previous reports of glial reactivity in the DS brain (Jørgensen et al., 1990; C. Chen et al., 2014; Pinto et al., 2020; Ponroy Bally and Murai, 2021).

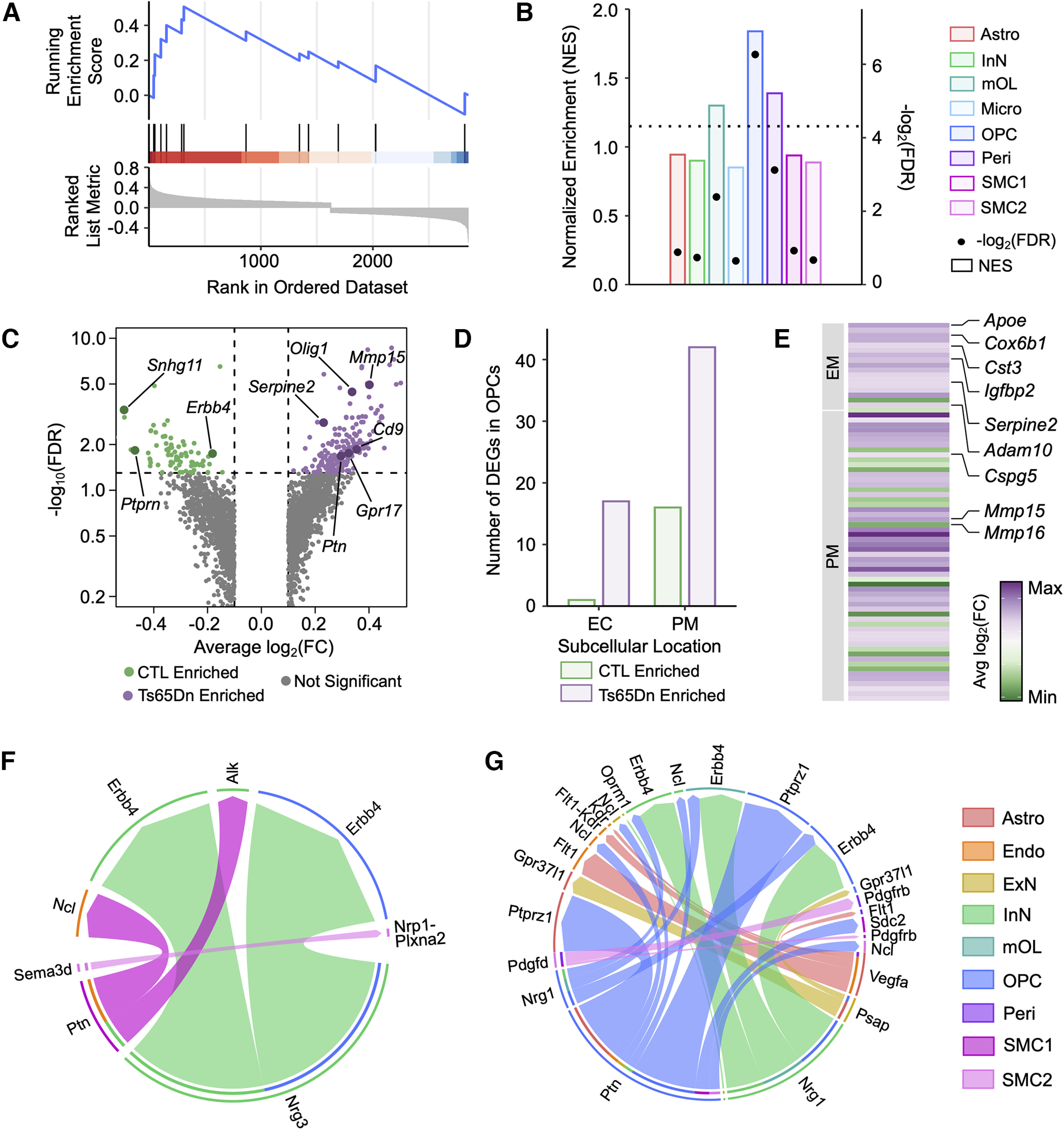

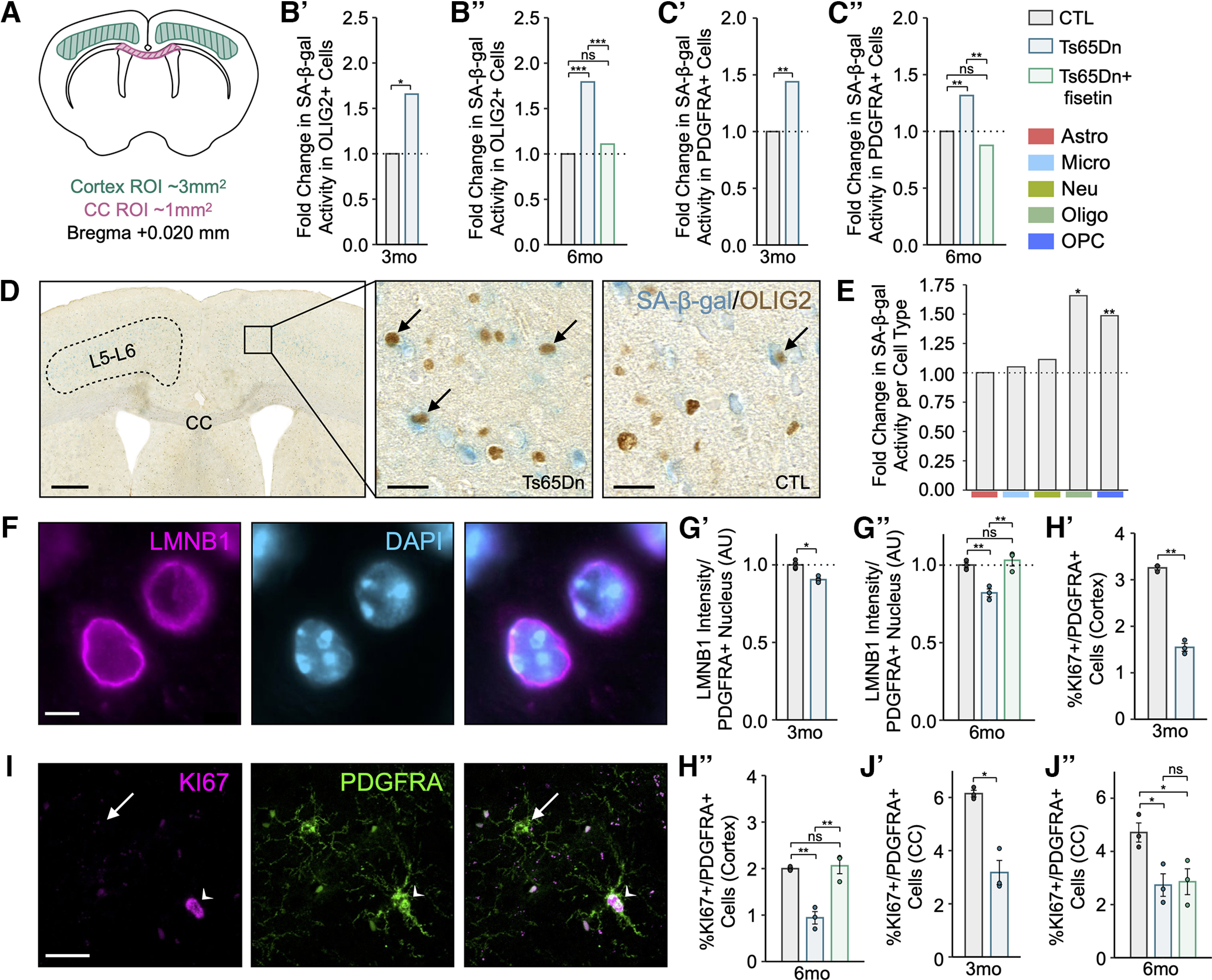

Cortical Ts65Dn OPCs exhibit enrichment for a senescence-associated gene signature and an altered cell surfaceosome landscape

Given reports of increased DNA damage and chronic neuroinflammation in DS and the Ts65Dn brain (Guedj et al., 2016; Ahmed et al., 2021; Puente-Bedia et al., 2022), we hypothesized that subpopulations of Ts65Dn cells would exhibit accelerated senescence. Senescent cells accumulate in aged tissues because of exhaustion of proliferation-competent cells (Di Micco et al., 2021; Kumari and Jat, 2021). However, the identification and characterization of senescent cells, particularly in bulk or single-nucleus sequencing data, is challenging because of the low average expression of many senescence-associated transcripts and the imprecise genetic definition of cellular senescence. We thus performed GSEA using a recently-published senescence-associated gene signature: SenMayo (Saul et al., 2022; Materials and Methods). This gene set is composed of 125 senescence-associated genes, including key SASP factors, transmembrane, and intracellular protein-encoding transcripts that have been validated across murine and human age-related transcriptomic datasets. Through this analysis, we observed selective enrichment (normalized enrichment score, NES > 0, FDR < 0.05) of the SenMayo gene set only in Ts65Dn OPCs (Fig. 4A,B), suggesting a cell type-specific senescence phenotype in this population.

Figure 4.

Cortical Ts65Dn OPCs exhibit a selective senescence-associated phenotype. A, GSEA-based enrichment plot of the SenMayo senescence gene set for OPCs. The upper y-axis represents the enrichment score (ES), and the blue line represents the running enrichment score. The x-axis displays gene ranked according to their expression in Ts65Dn, with the most upregulated genes on the left-hand side and the most downregulated genes toward the right-hand side. Black vertical lines depict the positions of individual genes and their enrichment within the transcriptional signature. B, Barplot displaying the enrichment of the SenMayo senescence gene set across cortical cell types. The bars correspond to the left y-axis, displaying normalized enrichment score for each cell type by pathway and are colored by cell type identity. The dots correspond to the right y-axis, displaying -log2(FDR) for each cell type by pathway; the dashed horizontal line intercepts the right y-axis at 4.3, corresponding to an FDR = 0.05. All dots above this horizontal line are statistically significant. C, Volcano plot of OPC DEGs in Ts65Dn versus CTL conditions. Only genes with an average log2fold change [avg log2(FC)] >0.1 or <−0.1. are included in the plot. Each dot represents a gene. Dots are colored according to enrichment: green dots are enriched in CTL, purple dots are enriched in Ts65Dn, and gray dots are not significantly enriched in either condition. The horizontal line depicts an FDR = 0.05, such that all genes above this line are statistically significant. D, Barplot depicting the number of DEGs (FDR < 0.05) in OPCs with functionality localized to the extracellular compartment (EC) or plasma membrane (PM). Purple bars depict DEGs enriched in Ts65Dn, and green bars depict DEGs enriched in CTL. E, Heatmap of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) localized to the extracellular compartment (EC) or plasma membrane (PM) in OPCs. Each row represents a gene. The color code represents the avg log2(FC) of gene expression between Ts65Dn and CTL. F, Chord diagram of cell-cell signaling pathways that are downregulated in Ts65Dn versus CTL. Cell type identity of the ligand is indicated in the outermost edge of the diagram, while the cell identity of the receptor is indicated by the internal ring. Colored arrows indicate the specific ligand-receptor (LR) pairs and are colored according to the outgoing ligand signal. G, As in F, but depicting cell-cell signaling pathways that are upregulated in Ts65Dn versus CTL.

Trisomic OPCs also demonstrated altered expression of several genes pertaining to maturation, proliferation, and inflammation (Fig. 4C). Among Ts65Dn-enriched OPC DEGs, we observed increased expression of Gpr17, which causes myelinogenesis defects when overexpressed in OL-lineage cells (Y. Chen et al., 2009; Ou et al., 2016), Mif, a proinflammatory cytokine that regulates NF-κB and p53 expression (Salminen and Kaarniranta, 2011; Kim et al., 2017), as well as Mmp15 and Adamts17, which are endoproteases that mediate the activity and bioavailability of inflammatory factors, such as TNFα and IL-1 (Rosenberg, 2002; Cabral-Pacheco et al., 2020). GSEA analysis of Ts65Dn OPCs also revealed an enrichment for metabolic regulation by p53, a key TF whose upregulation induces growth arrest, apoptosis, and cellular senescence (Mijit et al., 2020).

Cellular senescence is also marked by the widescale disruption of protein secretion and expression, which leads to the acquisition of a senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP). The SASP includes chemokines, cytokines, matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), interleukins, and proteases, which damage and modify the surrounding microenvironment (Coppé et al., 2010). Further examination of OPC DEGs revealed that Ts65Dn-upregulated DEGs include several SASP family members, including Apoe, Igfbp2, Cst3, Serpine2, and Cox6b1 (Fig. 4D,E). Aberrant apolipoprotein E (APOE) accumulation has been shown to drive senescence through degradation of nuclear envelope proteins that lead to heterochromatin destabilization and disorganization (Zhao et al., 2022). IGFBP2 similarly induces and sustains cellular senescence by inhibiting apoptosis via the interaction with and protection of p21 (Mercurio et al., 2020). Alongside the induction of tissue sensing programs and secreted mediators, senescent cells demonstrate remodeling of the cell-surfaceome landscape through the upregulation of transcripts encoding plasma membrane (PM) proteins (H.A. Chen et al., 2023). Indeed, many of the upregulated DEGs in Ts65Dn OPCs encoded PM proteins, such as ECM molecules (Adam10, Cspg5, Mmp15/16), and VEGF signaling molecules (Cadm4, Cd63; Fig. 4D,E). Taken together, the increase in extracellular (EC) and PM-encoding transcripts suggests an enhanced capability to sense and secrete environmental cues permitting senescent Ts65Dn OPCs an increased interaction with and influence of their surrounding microenvironment.

Ligand-receptor (LR) analysis of the Ts65Dn cortex identifies changes in intercellular communication

Given the importance of cell-cell signaling in shaping neural circuits, we performed ligand-receptor (LR) mapping in the six-month Ts65Dn and euploid CTL cortex using CellChat (S. Jin et al., 2021; Materials and Methods). We sought to build a comprehensive intercellular signaling network and better understand how trisomy-driven changes in gene expression affect cell-cell signaling by leveraging the transcriptional profiles of each cell population. Network analysis showed that 24 signaling pathways in the cortex were perturbed in Ts65Dn mice. Pleiotrophin (Ptn) and neuregulin (Nrg) were among the top mediators of disrupted crosstalk between various major cell types in the Ts65Dn cortex (Fig. 4F,G).

PTN is a ligand for several receptors in the brain, including protein tyrosine phosphatase receptor type Z1 (PTPRZ1), anaplastic lymphoma kinase (ALK), and nucleolin (Ncl; X. Wang, 2020; Papadimitriou et al., 2022). We found increased Ptn to Ptprz1 signaling in OPCs, decreased Ptn to Alk signaling between SMC1 and InNs, and decreased Ptn to Ncl signaling between SMC1 and endothelial cells in the trisomic mouse brain (Fig. 4F,G). Upregulated PTN-PTPRZ1 signaling indirectly increases the bioavailability of β-catenin, whose activity can hinder both developmental myelination and adult remyelination (Harroch et al., 2002; McClain et al., 2012). The increased PTPRZ1 signaling in OPCs may thus contribute to the defective myelinogenesis observed in trisomy. Homeostatic PTN-ALK signaling promotes differentiation, growth, and survival (Bowden et al., 2002). This LR pair may therefore represent a key signaling node whose downregulation contributes to abnormalities and disruptions in Ts65Dn InN network activity (Huo et al., 2018; Giffin-Rao et al., 2022; Zorrilla de San Martin et al., 2020). NCL is expressed in endothelial cells and plays a role in angiogenesis and vascularization (Koutsioumpa et al., 2012). The downregulated signaling of a proangiogenic LR interaction in endothelial cells is thus consistent with prior observations of impaired endothelial vascular recruitment and mobilization in DS (Reynolds et al., 2010; Koutsioumpa et al., 2012).

Another set of perturbed pathways detected in Ts65Dn mice involved inferred interactions between Erbb2 receptor tyrosine kinase 4 (Erbb4) with neuregulin1 (Nrg1) and neuregulin3 (Nrg3). We uncovered increased Nrg1 to Erbb4 signaling in OPCs and InNs, and decreased Nrg3 to Erbb4 signaling between InNs and OPCs in the Ts65Dn cortex (Fig. 4F,G). NRG1 regulates neuronal plasticity and migration, OL-lineage maturation, myelination, and dendritic arborization (Mei and Xiong, 2008). In InNs, NRG1 signaling through ERBB4 plays a critical role in circuit development, neuronal differentiation and GABAergic transmission (Ting et al., 2011; Cahill et al., 2012). Similarly, this signaling is vital in regulating OPC growth, proliferation, and differentiation into mOLs (Brinkmann et al., 2008). The dysregulation of this LR interaction between InNs and OPCs may thus contribute to DS cognitive disability attributable to excitatory/inhibitory (E/I) imbalance (Souchet et al., 2014), modified neural-network excitability (Contestabile et al., 2017), and reduced axon myelination (Jose Luis Olmos-Serrano et al., 2016; Reiche et al., 2019). Like Nrg1, Nrg3 is part of the neuregulin (Nrg) family and plays an important role in neural circuitry development through Erbb4 signaling (D. Zhang et al., 1997; Mei and Nave, 2014). Its downregulation has been implicated in several neurologic and psychiatric conditions such as schizophrenia (Avramopoulos, 2018). Importantly, the imbalance of NRG signaling in the brain can drive neuropathology by compromising overall neural connectivity and circuit homeostasis. Thus, the disrupted reciprocal interaction we observe in the Ts65Dn Nrg1/3 LR networks may promote broad disruptions in brain architecture.

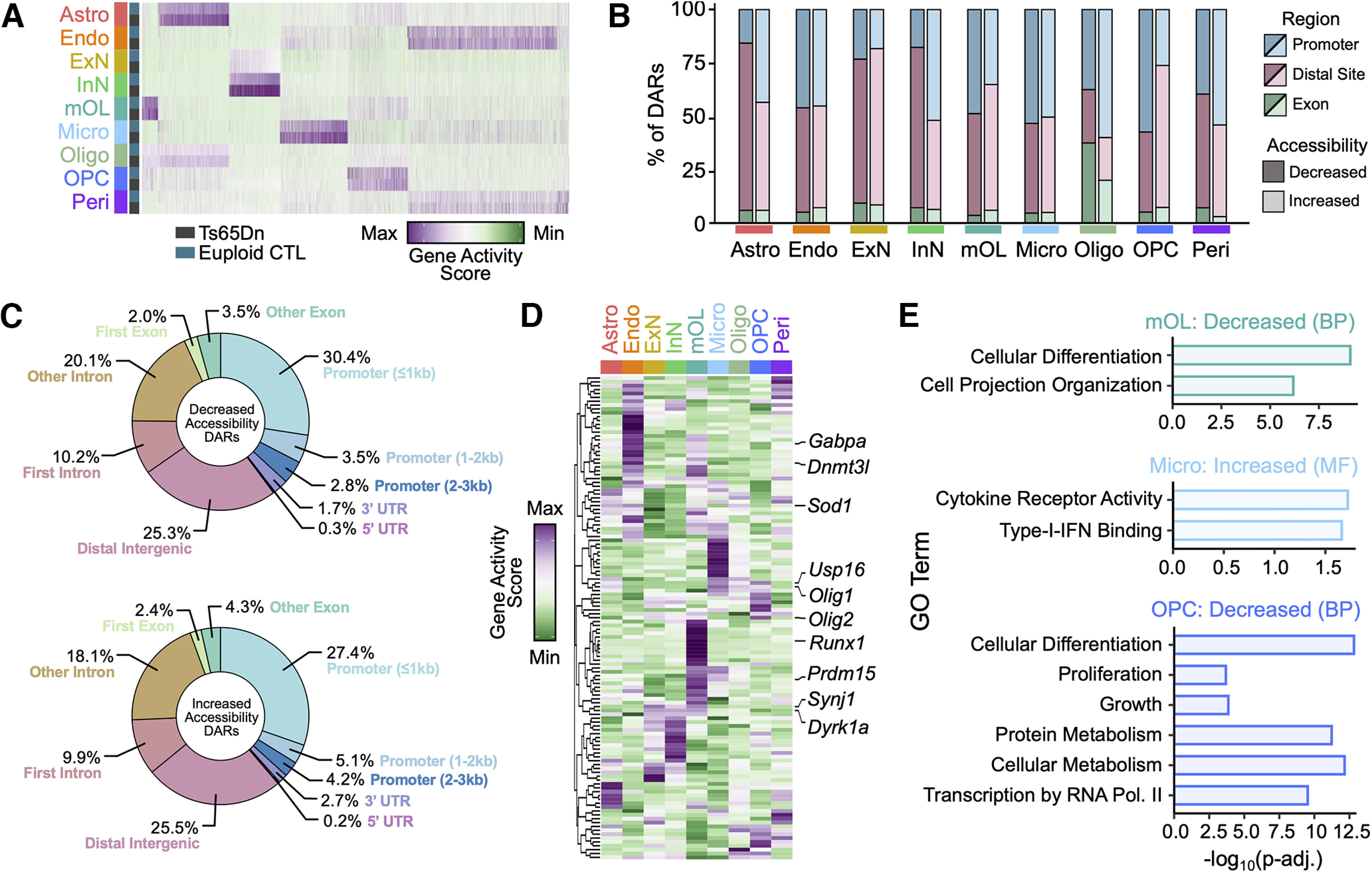

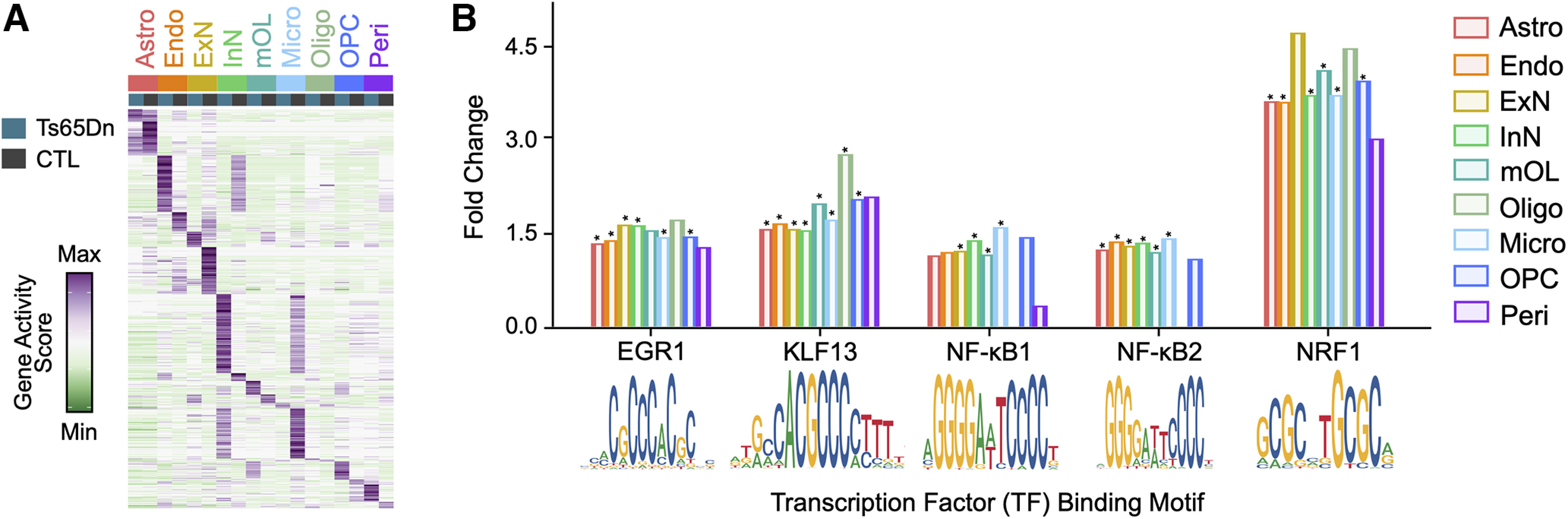

Ts65Dn trisomy induces unique chromatin accessibility patterns in the mature cortex

To identify cell type-specific changes in the chromatin landscape of the Ts65Dn cortex, we analyzed differentially accessible regions (DARs) in snATAC-seq (Materials and Methods). We used DARs that met an FDR value of 0.05 to define statistically significant changes in chromatin-level expression between Ts65Dn and CTL offspring. We found that DARs were highly heterogeneous across cortical cell types (Fig. 5A; Table 4) and a majority (75.1%) were downregulated (Fig. 5B). To assess the genomic distribution of DARs, we used ChIPseeker (Q. Wang et al., 2022; Materials and Methods). We found that the distribution of DARs was relatively consistent across cell types, with a majority occurring in distal regulatory sites (Fig. 5B). Across DARs, ∼6% were found in exons, ∼36% were found in promoters (<0–3 kb), and ∼56% were found in distal regulatory sites (5′/3′ UTR, introns, >300kb downstream, or intergenic; Fig. 5C).

Figure 5.

Chromatin accessibility landscape in the mature Ts65Dn cortex. A, Heatmap of the average number of cut sites within a DAR for each cell type by condition. Each column represents a cell type from Ts65Dn or CTL. The color code represents the gene activity score. B, Stacked barplot displaying the genomic distribution of differentially accessible regions (DARs). DARs located within promoters (<0–3 kb of the gene) are colored in blue, within distal regulatory sites (5′/3′ UTRs, introns, >300 kb downstream of the gene or intergenic) are colored in pink, or within exons are colored in green. Bars shaded in darker colors correspond to DARs showing decreased accessibility in Ts65Dn, and bars shaded in lighted colors correspond to DARs showing increased accessibility in Ts65Dn. Bars are grouped according to cell type identity. C, Pie chart of the genomic distribution of DARs that exhibit decreased or increased accessibility in Ts65Dn mice. Each fraction of the pie corresponds to a different genomic region, and is labeled according to the percentage of DARs associated with the specific genomic region. D, Hierarchically clustered heatmap of normalized gene accessibility for genes contained within the Ts65Dn chromosomal product. The plot displays gene activity across all cell types in snATAC-seq. Several genes of interest are indicated. Each column represents a cell type. The color code represents the row-normalized accessibility for each gene. E, Barplot of the -log10(p-adj) value of enrichment for select gene ontology (GO) biological process (BP) or molecular function (MF) terms for mature oligodendrocytes (mOL), microglia (Micro), and oligodendrocyte precursor cells (OPC). Bars are colored according to cell type.

Table 4.

Top five loci with increased accessibility in each cortical cell type in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL

| Gene | FDR | log2(FC) | Cell type | Gene | FDR | log2(FC) | Cell type |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acsl3 | 1.24E-31 | 0.38 | Astro | Dscaml1 | 7.58E-13 | 0.21 | mOL |

| Enthd1 | 1.96E-14 | 0.31 | Astro | Prr18 | 3.44E-11 | 0.21 | mOL |

| Tiam2 | 1.63E-16 | 0.31 | Astro | Dleu2 | 1.07E-10 | 0.50 | Micro |

| Gas7 | 1.62E-12 | 0.30 | Astro | Magi1 | 7.32E-08 | 0.42 | Micro |

| Ripk4 | 7.13E-11 | 0.29 | Astro | Ccr6 | 9.00E-07 | 0.33 | Micro |

| Mlph | 2.68E-10 | 0.56 | Endo | Ccr6 | 9.37E-05 | 0.30 | Micro |

| Rnf150 | 8.14E-10 | 0.54 | Endo | Chsy1 | 2.92E-06 | 0.28 | Micro |

| Slc5a6 | 8.37E-11 | 0.53 | Endo | Snx33 | 2.22E-02 | 0.46 | Oligo |

| Calr3 | 7.76E-15 | 0.51 | Endo | Cnbd2 | 2.22E-02 | 0.43 | Oligo |

| Coro2b | 2.15E-12 | 0.47 | Endo | Dtna | 4.13E-02 | 0.30 | Oligo |

| Car10 | 2.29E-144 | 0.25 | ExN | Dyrk1a | 1.84E-02 | 0.22 | Oligo |

| Dennd1b | 1.16E-121 | 0.24 | ExN | Rps6ka2 | 2.22E-02 | 0.22 | Oligo |

| Ifi202b | 1.51E-66 | 0.17 | ExN | Itga9 | 3.93E-06 | 0.34 | OPC |

| Dleu2 | 5.09E-64 | 0.16 | ExN | Olig2 | 3.58E-09 | 0.32 | OPC |

| Pde10a | 5.43E-51 | 0.15 | ExN | Ptpn14 | 2.11E-05 | 0.31 | OPC |

| Cldn17 | 1.44E-14 | 0.16 | InN | Cspg4 | 4.11E-05 | 0.29 | OPC |

| Acoxl | 1.84E-13 | 0.16 | InN | Olig2 | 7.81E-05 | 0.29 | OPC |

| Atp5j | 1.21E-41 | 0.16 | InN | Trp53i11 | 1.18E-02 | 0.46 | Peri |

| Arhgap15 | 1.09E-10 | 0.16 | InN | Msx1 | 5.06E-03 | 0.44 | Peri |

| Mis18a | 1.25E-11 | 0.15 | InN | Rps2-ps6 | 1.04E-02 | 0.43 | Peri |

| Fcho1 | 1.52E-81 | 0.50 | mOL | Gltp | 6.28E-04 | 0.42 | Peri |

| Mylk | 1.78E-17 | 0.27 | mOL | Rps6ka2 | 2.09E-03 | 0.41 | Peri |

| App | 8.82E-22 | 0.23 | mOL |

Listed are the top five genes [ranked by highest average log2(FC)] that show significant differential accessibility in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL as detected via snATAC-seq. Shown are fold-change values of the average expression for each gene and the false discovery rate (FDR) between Ts65Dn and CTL cells. Each cell type is listed in the final column and is abbreviated as described in Table 1.

Ts65Dn cells exhibited increased accessibility of ∼25% of Ts65Dn-encoded genes at the chromatin level. Similar to snRNA-seq, we observed heterogeneous accessibility levels of Ts65Dn triplicated genes across cell types, with only a few gene loci including the antioxidant Sod1, the kinase Dyrk1a, and the spliceosome component Son at significantly higher levels in at least seven out of nine identified cortical cell types (Fig. 5D). Increased chromatin accessibility of Olig1 and Olig2 loci was observed selectively in astrocytes, mOLs, and OPCs. Overexpression of Olig2 has been shown to preferentially drive progenitors toward a GFAP+ reactive astrocyte fate rather than an OL-lineage fate (Lu et al., 2012) and can trigger transcriptional repression during myelinogenesis (K. Zhang et al., 2022). The Runx1 locus exhibited increased accessibility in Ts65Dn microglia; RUNX1 is a TF that modulates microglial gene expression during early postnatal life, but can increase in adults following brain injury or infection to promote microglial activation (Zusso et al., 2012; Yeh and Ikezu, 2019). Synj1 was another locus that showed selective increased accessibility in trisomic InNs and is known for its involvement with endocytosis and synaptic vesicle cycling (Choudhry et al., 2021). Specifically, elevated levels of SYNJ1 have been shown to trigger deficits in age-dependent long-term memory retention in individuals with DS-related AD (Miranda et al., 2018), thus implicating SYNJ1 as a key mediator of cognitive disability.

We next employed gene ontology (GO) analysis to assess biological pathways associated with chromatin accessibility changes in Ts65Dn mice (Materials and Methods; Table 5; Raudvere et al., 2019). Among downregulated DARs from trisomic OPCs and mOLs, we observed an enrichment of GO categories associated with cell differentiation, projection organization, and regulation of metabolic processes (Fig. 5E). We also found enrichment of biological process (BP) ontologies associated with growth and proliferation in trisomic OPC DARs with decreased accessibility, further suggesting a disruption in OPC development and a growth arrest typical of a senescence phenotype (Fig. 5E). Consistent with the hyperactive inflammatory milieu known to occur in the trisomic brain (Wilcock, 2012; Flores-Aguilar et al., 2020), we observed an enrichment of cytokine receptor activity and type-I-IFN binding among the top five enriched molecular function (MF) categories for increased accessibility DARs in Ts65Dn microglia (Fig. 5E). Taken together, these findings demonstrate that trisomy has a profound genome-wide impact on gene expression, with a notable effect on genes related to inflammation and differentiation in glial cell populations.

Table 5.

Top three Ts65Dn enriched biological processes (BP) in each cortical cell type identified via gene ontology (GO) analysis in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL

| GO biological process (BP) pathway | FDR | Gene ratio | Cell type |

|---|---|---|---|

| System development | 1.05E-05 | 0.35 | Astro |

| Positive regulation of biological process | 1.76E-05 | 0.45 | Astro |

| Regulation of metabolic process | 7.97E-05 | 0.47 | Astro |

| Anatomical structure development | 1.66E-20 | 0.42 | Endo |

| Negative regulation of cellular process | 1.57E-19 | 0.36 | Endo |

| Developmental process | 3.78E-19 | 0.44 | Endo |

| Phosphate-containing compound metabolic process | 6.34E-04 | 0.40 | ExN |

| Phosphorus metabolic process | 7.09E-04 | 0.40 | ExN |

| Organophosphate metabolic process | 4.31E-03 | 0.24 | ExN |

| Synapse assembly | 6.34E-03 | 0.10 | InN |

| Animal organ development | 1.27E-02 | 0.37 | InN |

| Positive regulation of gene expression | 1.92E-02 | 0.20 | InN |

| Cell development | 1.08E-07 | 0.32 | mOL |

| Neurogenesis | 3.24E-07 | 0.27 | mOL |

| Nervous system development | 9.38E-07 | 0.31 | mOL |

| Regulation of cellular process | 2.93E-05 | 0.67 | Micro |

| Biosynthetic process | 3.88E-05 | 0.41 | Micro |

| Cellular biosynthetic process | 7.17E-05 | 0.40 | Micro |

| Multicellular organism development | 5.54E-22 | 0.44 | OPC |

| Anatomical structure development | 3.08E-21 | 0.49 | OPC |

| System development | 1.13E-19 | 0.40 | OPC |

| Cellular localization | 2.48E-05 | 0.35 | Peri |

| Phosphate-containing compound metabolic process | 7.90E-04 | 0.29 | Peri |

| Phosphorus metabolic process | 9.26E-04 | 0.29 | Peri |

Listed are the top three biological processes (BP) identified via GO analysis (ranked by lowest FDR value) that are significantly enriched in Ts65Dn mice compared with CTL. The gene ratio is defined as the ratio between the intersection size and query size. Oligo cells were not included in this list, as no pathways were significantly enriched (FDR < 0.05) between conditions. Each cell type is listed in the final column and is abbreviated as described in Table 1.

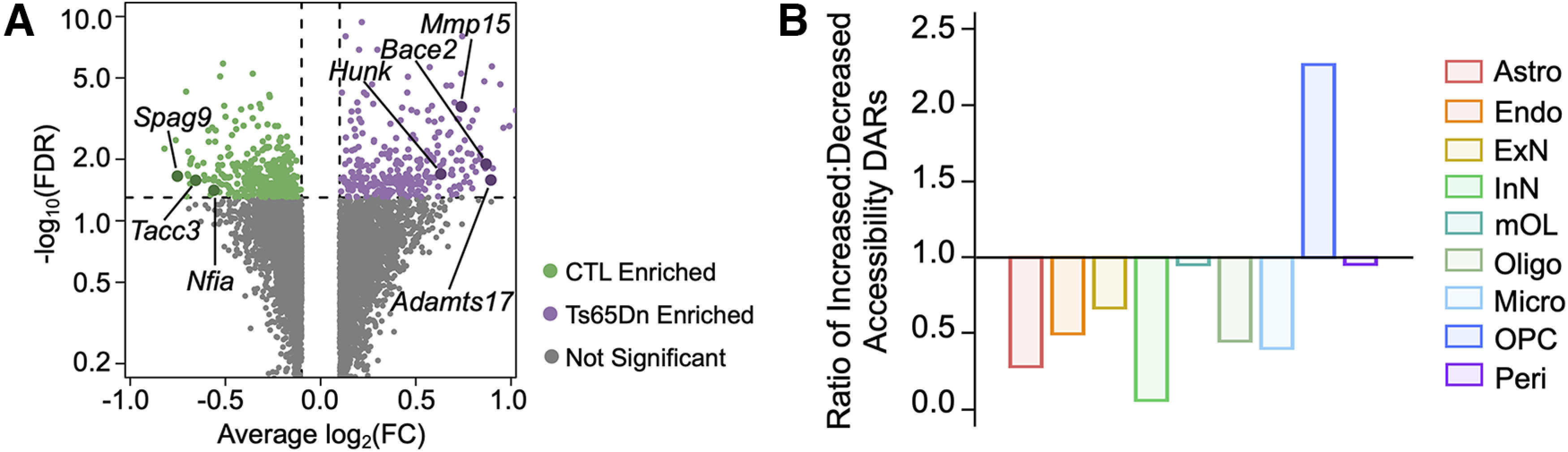

Ts65Dn OPCs exhibit an altered chromatin state consistent with cellular senescence

To assess locus-specific changes in Ts65Dn OPC chromatin accessibility, we more closely examined population-level DARs. Herein, we observed reduced accessibility at several cell growth and mitosis regulatory loci (Fig. 6A), including Tacc3, Knstrn, Ptprg, and Spag9, whose suppression can induce cell-cycle arrest and tend cells toward a senescent state (C.S. Lee et al., 2014; Cheung et al., 2015; Suhail et al., 2015; Jagadish et al., 2016). Further, we observed increased accessibility at several chondroitin sulfate proteoglycans (CSPG) loci, including Tnr, Bcan, Vcan, Acan, and Ncan (Jang et al., 2020; Fig. 6A). CSPGs have been found to negatively regulate OPC proliferation, differentiation and remyelination, as well as induce production of proinflammatory cytokines (Ghorbani and Yong, 2021; Tewari et al., 2022). Similar to our findings in snRNA-seq data, we found that Ts65Dn OPCs exhibited an increase in accessibility at several endoprotease loci, including Mmp15/19, Adam12, and Adamts5/17 loci (Fig. 6A), all of which play a role in modulating neuroimmune activity through the regulation of proinflammatory cytokine availability and signaling (Rosenberg, 2002; Cabral-Pacheco et al., 2020).

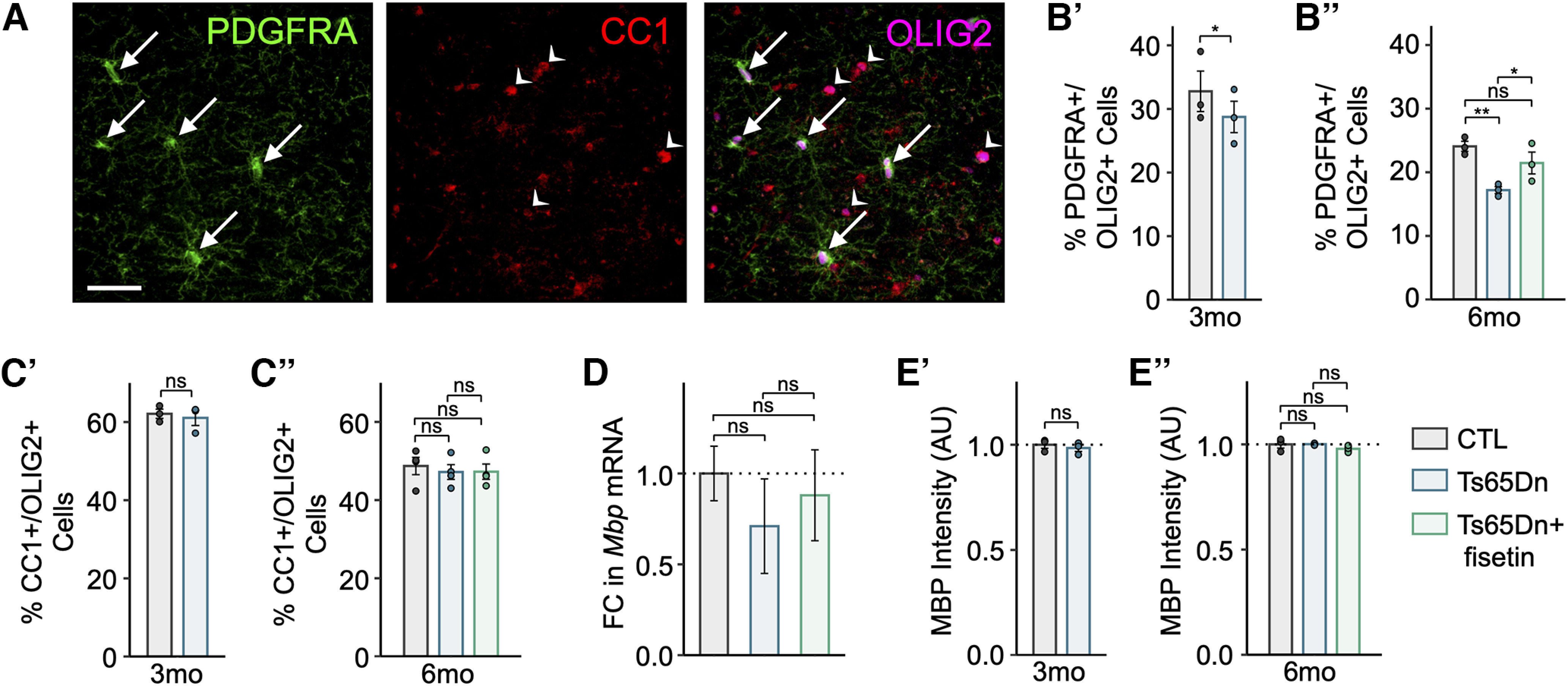

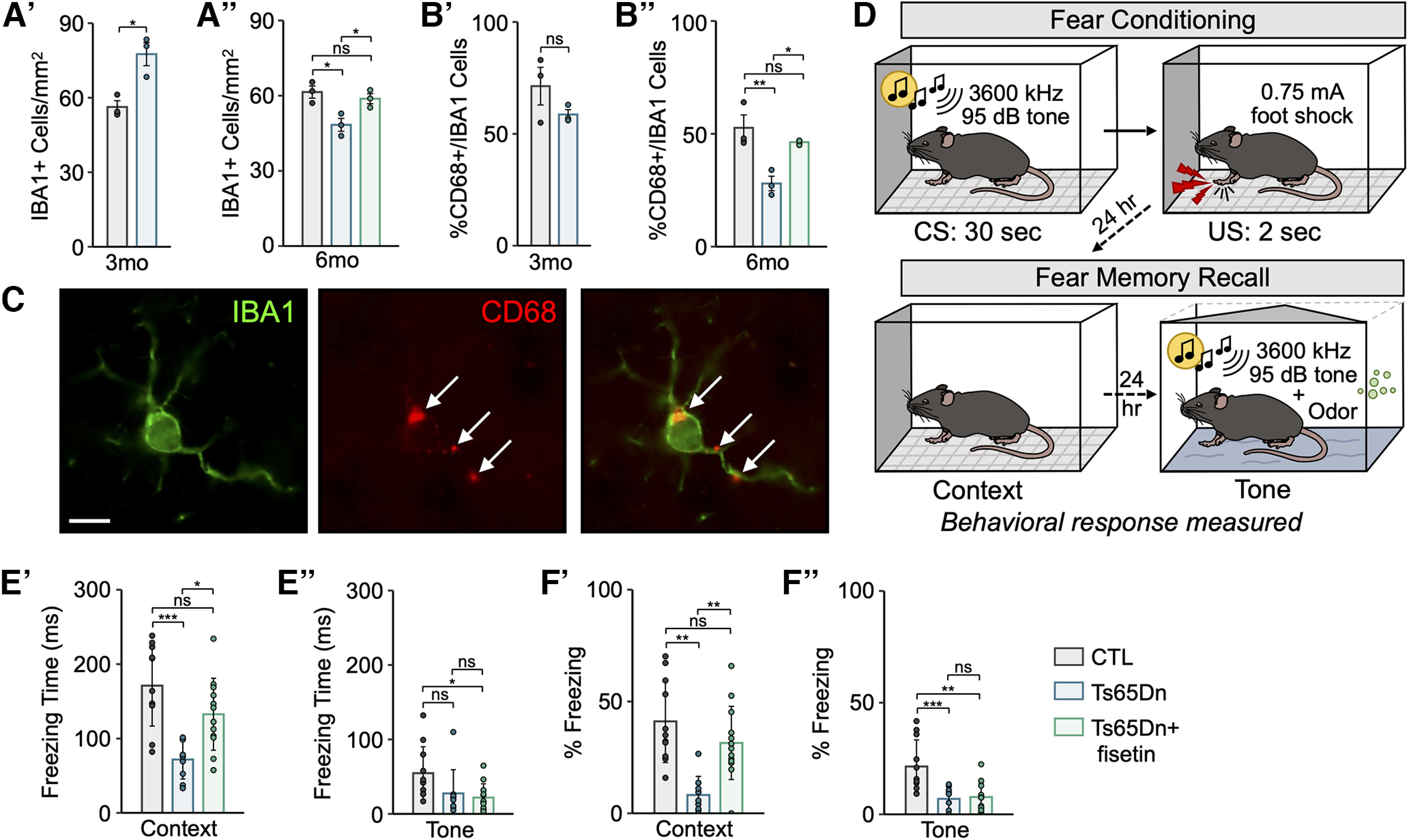

Figure 6.