Abstract

Objective

We aimed to investigate the safety of drug-coated balloon (DCB)-only angioplasty compared to drug-eluting stent (DES), as part of routine clinical practice.

Background

The recent BASKETSMALL2 trial demonstrated the safety and efficacy of DCB angioplasty for de novo small vessel disease. Registry data have also demonstrated that DCB angioplasty is safe; however, most of these studies are limited due to long recruitment time and a small number of patients with DCB compared to DES. Therefore, it is unclear if DCB-only strategy is safe to incorporate in routine elective clinical practice.

Methods

We compared all-cause mortality and major cardiovascular endpoints (MACE), including unplanned target lesion revascularisation (TLR) of all patients treated with DCB or DES for first presentation of stable angina due to de novo coronary artery disease between 1st January 2015 and 15th November 2019. Data were analysed with Cox regression models and cumulative hazard plots.

Results

We present 1237 patients; 544 treated with DCB and 693 treated with DES for de novo, mainly large-vessel coronary artery disease. On multivariable Cox regression analysis, only age and frailty remained significant adverse predictors of all-cause mortality. Univariable, cumulative hazard plots showed no difference between DCB and DES for either all-cause mortality or any of the major cardiovascular endpoints, including unplanned TLR. The results remained unchanged following propensity score-matched analysis.

Conclusion

DCB-only angioplasty, for stable angina and predominantly large vessels, is safe compared to DES as part of routine clinical practice, in terms of all-cause mortality and MACE, including unplanned TLR.

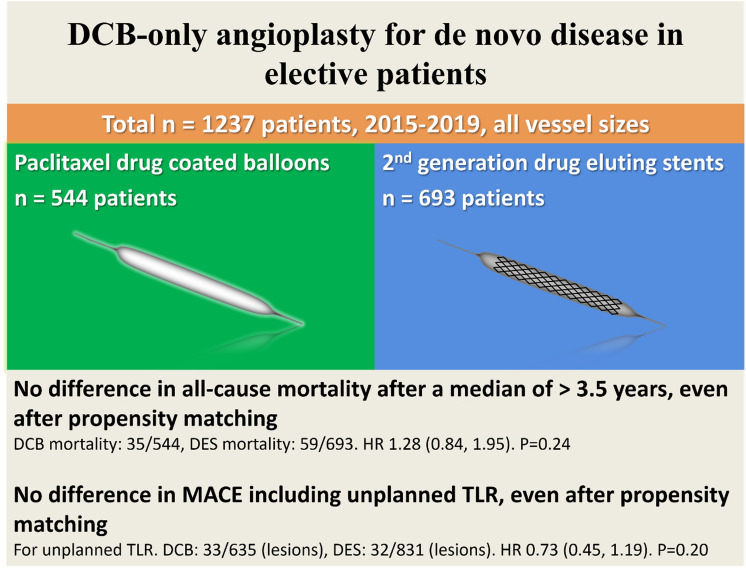

Graphic abstract

Keywords: Drug-coated balloon, De novo disease, Stable angina

Introduction

Implantation of second-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) is the current guideline-recommended treatment strategy for de novo coronary artery disease [1]. Stents were initially developed to treat the limitations of plain old balloon angioplasty related to flow-limiting dissections and acute vessel recoil [2]. However, the persistence of stent-related complications, such as stent thrombosis and in-stent restenosis, stimulated the concept of ‘leaving nothing behind’ [2]. Drug-coated balloons (DCB) were developed to combine the benefits of local drug treatment without the complications of stent implantation in cases where stenting was not mandated after initial angioplasty [3]. Currently, DCBs represent an alternative, emerging treatment strategy with supportive evidence in specific groups, such as patients with in-stent restenosis, high-bleeding risk or small vessel disease [4, 5]. Randomised data have demonstrated maintained safety and efficacy of DCB vs DES for de novo small vessel coronary artery disease [6–8]. However, there are no data about the safety of DCB-only angioplasty as part of routine clinical practice and there are limited data about the safety of DCB in de novo large vessels [9]. There are no data evaluating if it is possible and safe for DCB-only angioplasty to become part of a routine PCI treatment strategy.

Previous work from our group (SPARTAN DCB) demonstrated that there is no evidence of increased late mortality associated with paclitaxel DCB, and indeed better survival with DCB in the propensity score-matched cohort [10]. However, that analysis excluded patients with previous percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) and patients with different PCI strategy in subsequent procedures compared to index (i.e. patients treated with DES initially and then later treated with DCB or vice versa were excluded). Even though that study design was necessary in order to achieve group homogeneity and investigate a true potential effect of paclitaxel, it poses a limitation in terms of generalisability. In the current study we have addressed this limitation by including patients with previous PCI and subsequent PCI irrespective of initial PCI strategy.

In this study, we aimed to explore the safety of DCB-only angioplasty judged by overall mortality, as well as major cardiovascular endpoints, in routine clinical practice for stable, de novo coronary artery disease in all vessel sizes.

Methods

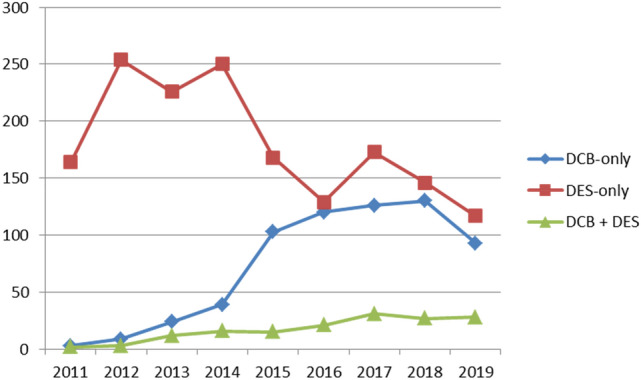

The paclitaxel drug-coated balloon-only angioplasty for stable de novo coronary artery disease in routine clinical practice study was an investigator-initiated, single-centre, cohort study. In our institution, patients undergoing PCI are prospectively entered in a dedicated clinical database. Following approval from the Northwest Haydock (17/NW/0278), UK research ethics committee and Institutional Board approval by the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, we retrospectively surveyed our clinical database to identify all patients whose first entry was for stable, de novo coronary artery disease, up to November 2019. The confidentiality advisory group waived the need for patient consent due to the retrospective nature of our study (17/CAG/0145). In our institution, the use of DCB has steadily increased with a complementary decrease in second-generation DES use over the last ten years. From 2015 onwards more than 100 patients per year (more than about 40% of patients), with first presentation of stable angina and de novo disease, were treated with DCB-only angioplasty (Fig. 1). We included patients from January 2015 to November 2019 to allow a similar number of patients to be included from each group, without affecting the follow-up period in each group. Clinical and angiographic data were obtained from our prospectively collated database supplemented with data from electronic hospital records as required. All angiograms were reviewed by an expert operator to confirm accuracy of treatment strategy, classify bifurcation disease, coronary dissection post-DCB implantation, and determine target lesion revascularisation. A lesion was defined as a bifurcation if there was a side branch more than 2 mm in diameter within 5 mm of the lesion. MEDINA subtypes 1.1.1, 1.0.1 and 0.1.1 were considered as true bifurcations [11]. The vessel diameter was considered as the largest pre-/post-dilatation balloon, DCB or DES used and lesion length was based on the DCB or DES length.

Fig. 1.

Yearly usage of DCB and DES in patients with first presentation with stable angina and de novo disease

The primary endpoint was all-cause mortality. The secondary endpoints were cardiovascular mortality, acute coronary syndrome (ACS), stroke or transient ischaemic attack, major bleeding and target lesion revascularisation. Patient outcomes were obtained from the Hospital Episode Statistics from NHS digital. Hospital Episode Statistics is a data warehouse containing details of all admission, outpatient appointments and accident and emergency attendances at NHS hospitals in England. Supplementary Table 1 demonstrates the ICD-10 diagnostic codes used to identify patients’ outcomes. All deaths were classified as cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular by an adjudication committee according to academic research consortium two consensus [12]. We used the validated Hospital Frailty Risk Score based on ICD-10 diagnostic codes to calculate the patients’ frailty index [13].

Statistical analysis was undertaken in R (version 4.2). Nominal variables are reported as counts (percentages) and compared by the Chi-square test. Variables that were not normally distributed, as assessed by the Kolmogorov and Shapiro tests, are reported as median (interquartile range (IQR)) and compared with non-parametric tests (Wilcoxon rank sum test). Univariable Cox regression analyses were performed to identify predictors of mortality and cardiovascular mortality. Predictors with p value < 0.05 were introduced into the multivariable Cox regression model. Data are reported as hazard rations (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals. A p value < 0.05 was considered significant. Cumulative hazard plots were used to compare patient outcomes. Comparisons were performed by the log-rank test.

Results

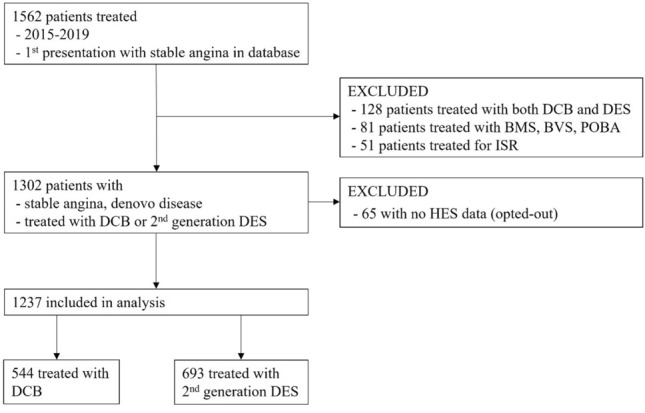

A total of 544 consecutive patients (640 de novo lesions) treated with paclitaxel DCB and 693 consecutive patients (831 de novo lesions) treated with 2nd-generation DES were identified (Fig. 2). The median age was 69 (IQR 61–75) for both groups. Male patients accounted for 79% of the DCB and 78% of the DES group. The groups were well balanced in baseline patient characteristics as shown in Table 1. The only difference was that the DES group had significantly more patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Fig. 2.

Consort diagram indicating how the final population included in this study was identified

Table 1.

Baseline patient characteristics of patients treated with DCB or DES

| Characteristic | DCB, N = 544 | DES, N = 693 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, median (IQR) | 69 (61–75) | 69 (61–75) | 0.611 |

| Male, n (%) | 429 (79) | 541 (78) | 0.742 |

| Current/ex-smoker, n (%) | 336 (62) | 455 (66) | 0.112 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia, n (%) | 186 (34) | 224 (32) | 0.492 |

| Hypertension, n (%) | 307 (56) | 397 (57) | 0.762 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 24 (4.4) | 33 (4.8) | 0.772 |

| Cerebrovascular disease, n (%) | 42 (7.7) | 37 (5.3) | 0.0892 |

| Myocardial infarction, n (%) | 93 (17) | 123 (18) | 0.762 |

| Percutaneous coronary intervention, n (%) | 79 (15) | 86 (12) | 0.282 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft, n (%) | 47 (8.6) | 56 (8.1) | 0.722 |

| Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 56 (10) | 52 (7.5) | 0.0842 |

| Heart failure, n (%) | 18 (3.3) | 20 (2.9) | 0.672 |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, n (%) | 18 (3.3) | 44 (6.3) | 0.0152 |

| Diabetes, n (%) | 125 (23) | 153 (22) | 0.712 |

| Family history, n (%) | 148 (27) | 174 (25) | 0.402 |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) median (IQR) | 79 (66–91) | 78 (67–91) | 0.851 |

| Frailty, n (%) | > 0.993 | ||

| Low | 541 (99) | 688 (99) | |

| Intermediate | 3 (0.6) | 5 (0.7) | |

| High | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

Data are n (%) or median (IQR)

DCB drug-coated balloon, DES drug-eluting stent, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

1Wilcoxon rank sum test

2Pearson's Chi-squared test

3Fisher's exact test

4Wilcoxon rank sum exact test

Bold indicate significant result

The angiographic characteristics of the target vessels treated are shown in Table 2. The groups were well balanced in terms of prognostically significant vessels targeted (LMS or LAD and multivessel PCI). The DES group had more patients with large vessel treated, while the DCB group had more patients with true bifurcations. The DES group had significantly more patients on dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT), while the duration of DAPT was significantly longer in the DES group as well.

Table 2.

Angiographic characteristics of target vessels treated with DCB or DES

| Characteristic | DCB, N = 544 | DES, N = 693 | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vessels treated, n (%) | 0.0062 | ||

| LMS | 15 (2.8) | 27 (3.9) | |

| LAD | 309 (57) | 376 (54) | |

| LCx | 104 (19) | 98 (14) | |

| RCA | 111 (20) | 172 (25) | |

| Graft | 5 (0.9) | 20 (2.9) | |

| Multivessel PCI, n (%) | 51 (9.4) | 83 (12) | 0.142 |

| Patients with true bifurcation disease, n (%) | 63 (12) | 56 (8.1) | 0.0382 |

| Patients with vessel treated ≥ 3 mm | 398 (73) | 594 (86) | < 0.0012 |

| Dual antiplatelet therapy | 518 (95.2%) | 681 (98.3%) | < 0.0022 |

| Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy, Median (IQR) days | 30 (29, 31) | 365 (364, 365) | < 0.0011 |

| Lesions | |||

| De novo lesions treated | DCB (640) | DES (831) | |

| True bifurcation, n (%) | 64 (10) | 55 (6.6) | 0.022 |

| Vessel diameter (mm), Median (IQR) | 3.00 (2.75–3.50) | 3.50 (3.00–3.75) | < 0.0011 |

| Lesion length (mm), median (IQR) | 20 (20–30) | 24 (18–38) | 0.0431 |

| Dissection grade post-DCB [14] | |||

| A | 20 (3.1%) | n/a | |

| B | 278 (43.4%) | n/a | |

| C | 5 (0.8%) | n/a | |

| D | 3 (0.5%) | n/a | |

DCB drug-coated balloon, DES drug-eluting stent, LMS left main stem, LAD left anterior descending, LCx left circumflex, RCA right coronary artery, TIMI thrombolysis in myocardial infarction * indicates significant result

1Wilcoxon rank sum test

2Pearson's Chi-squared test

3Fisher's exact test

4Wilcoxon rank sum exact test

Bold indicate significant result

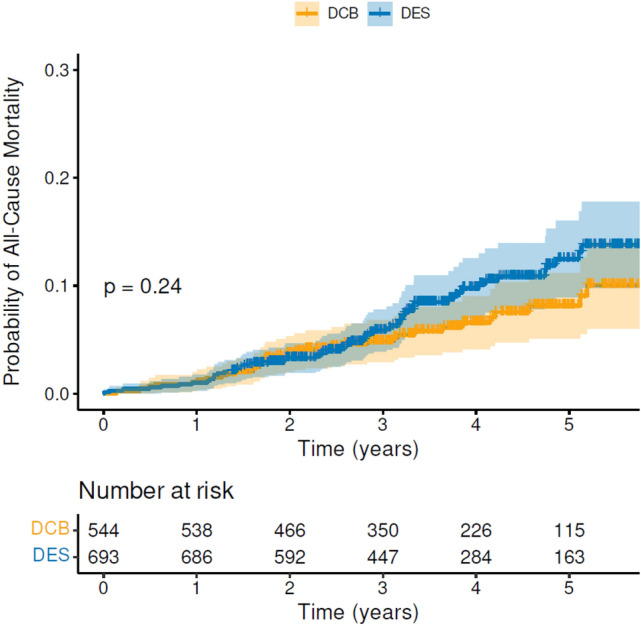

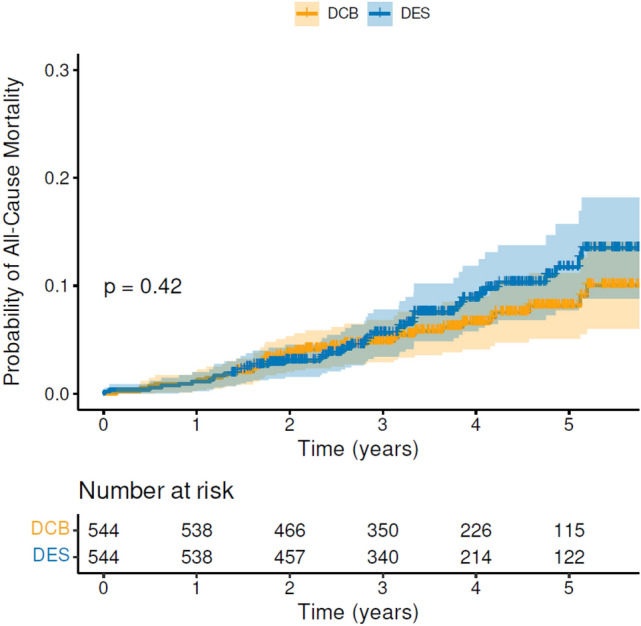

The median follow-up of patients in the DCB group was 3.7 years (IQR 2.5–4.8), while the median follow-up in the DES group was 3.6 years (IQR 2.6–4.9). There was no evidence of increased all-cause mortality (Fig. 3) associated with paclitaxel DCB for de novo coronary artery disease compared to 2nd-generation DES. The mortality rate was 35/544 in the DCB group versus 59/693 in the DES group (HR = 1.28; CI 0.84–1.95; p = 0.24). Furthermore, there was no difference in any of the secondary endpoints, cardiovascular mortality, ACS, stroke/TIA, major bleeding or unplanned TLR (Supplementary Fig. 1). Univariable Cox regression analysis identified the following adverse prognostic factors for all-cause mortality: increasing age, coronary artery bypass (CABG), heart failure, atrial fibrillation (AF), diabetes, decreasing estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and frailty. Hypercholesterolaemia was associated with better survival (Table 3). On multivariable Cox regression analysis only age and frailty remained significant predictors of mortality (Table 4). Finally, in terms of short-term safety, one patient in the DCB group had acute vessel closure a few hours later and needed to return urgently to the lab. Two patients in the DES group returned urgently to the lab within 72 h (one with subacute stent thrombosis and one with stent edge disruption requiring further stent). No other patient returned urgently to the lab within seven days in either group.

Fig. 3.

Cumulative hazard plot of all-cause mortality for DCB versus 2nd-generation DES with numbers at risk shown below the graph. DCB drug-coated balloon, DES drug-eluting stent

Table 3.

Results of univariable Cox regression analysis for all-cause mortality

| Mortality (Univariate) | N | Forest Plot | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DCB/DES [DES] | 1237 | 1.28 (0.84 to 1.95) | 0.24 | |

| Age | 1237 | 1.10 (1.07 to 1.12) | < 0.001 | |

| Gender [female] | 1237 | 1.56 (1.00 to 2.45) | 0.050 | |

| Smoking status [current/ex-smoker] | 1230 | 1.26 (0.81 to 1.95) | 0.31 | |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 1237 | 0.44 (0.26 to 0.74) | 0.002 | |

| Hypertension | 1237 | 1.42 (0.93 to 2.17) | 0.11 | |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 1237 | 1.51 (0.66 to 3.45) | 0.33 | |

| Cerebrovascular event | 1237 | 1.22 (0.56 to 2.63) | 0.62 | |

| Myocardial infarction | 1237 | 1.32 (0.81 to 2.15) | 0.26 | |

| PCI | 1237 | 1.29 (0.75 to 2.21) | 0.35 | |

| CABG | 1237 | 2.02 (1.15 to 3.57) | 0.015 | |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1237 | 2.29 (1.31 to 3.98) | 0.003 | |

| Heart failure | 1237 | 3.98 (1.92 to 8.24) | < 0.001 | |

| COPD | 1237 | 2.01 (0.97 to 4.14) | 0.060 | |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1237 | 1.58 (1.02 to 2.45) | 0.040 | |

| Family history of CAD | 1237 | 0.60 (0.36 to 1.01) | 0.055 | |

| eGFR | 1237 | 0.98 (0.97 to 0.99) | < 0.001 | |

| Frailty score | 1237 | 1.50 (1.36 to 1.65) | < 0.001 | |

| PCI to multiple vessels | 1237 | 0.84 (0.42 to 1.66) | 0.61 | |

| Bifurcation disease | 1237 | 1.27 (0.68 to 2.39) | 0.45 | |

| Average Vessel Diameter | 1231 | 0.91 (0.64 to 1.27) | 0.57 | |

| Vessel Diameter ≥ 3 mm | 1237 | 1.10 (0.65 to 1.83) | 0.73 |

HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG coronary artery bypass grafting, COPD chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate, DES drug-eluting stent

Bold indicate significant result

Table 4.

Results of multivariable Cox regression analysis for all-cause mortality

| All-cause mortality (multivariate) | N | HR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 1237 | 1.07 (1.05 to 1.10) | < 0.001 |

| Hypercholesterolaemia | 1237 | 0.59 (0.35 to 1.02) | 0.057 |

| Coronary artery bypass graft | 1237 | 1.46 (0.82 to 2.58) | 0.20 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 1237 | 1.24 (0.69 to 2.24) | 0.47 |

| Heart failure | 1237 | 1.71 (0.77 to 3.80) | 0.19 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1237 | 1.35 (0.86 to 2.12) | 0.19 |

| eGFR | 1237 | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.01) | 0.38 |

| Frailty score | 1237 | 1.34 (1.21 to 1.49) | < 0.001 |

eGFR estimated glomerular filtration rate

Bold indicate significant result

Following propensity score matching 544 patients treated with DCB were matched to 544 patients treated with 2nd-generation DES. Supplementary Table 2 shows the baseline characteristics of the propensity score-matched cohort. There was no difference in all-cause mortality (Fig. 4) or any of the secondary endpoints (cardiovascular mortality, ACS, stroke/TIA, major bleeding or unplanned TLR) (Supplementary Fig. 2). Analysis of patients with treated vessel ≥ 3 mm showed that the results were unchanged (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). In patients with large vessel treated, on multivariable Cox regression analysis, only increasing age and frailty score were significant predictors of all-cause mortality.

Fig. 4.

Cumulative hazard plot of all-cause mortality in propensity score-matched cohort, for DCB vs 2nd-generation DES with numbers at risk shown at the bottom of the graph. DCB drug-coated balloon, DES drug-eluting stent

DISCUSSION

Drug-coated balloon-only angioplasty is recommended in evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of in-stent restenosis and new indications are proposed in the recent International DCB Consensus Group recommendations [4, 15]. The recent BASKET-SMALL2 trial has demonstrated safety and efficacy of DCB in small vessels up to 3 years follow-up and opened up indications for DCB-only angioplasty in de novo coronary artery disease [6]. Over the last few years, registry data have demonstrated the safety of DCB-only angioplasty in de novo coronary disease [9, 10, 16]. However, the majority of these studies are limited by either long recruitment time or small numbers of patients treated with DCB-only compared to DES. In addition, very few studies directly compare DCB with DES for stable angina in de novo large-vessel disease. Therefore, it is still uncertain if DCB-only angioplasty could be part of routine clinical practice and compete safely with DES in the real world.

Our study has demonstrated that DCB-only angioplasty is safe in patients with stable angina and de novo coronary artery disease as part of a routine, clinical practice. In our institution, over the last 5 years a comparable number of patients with first presentation of stable angina due to de novo coronary disease were treated with DCB-only strategy and DES-only strategy, while at the same time, the number of patients treated with both DCB and DES remained low. There was no evidence of increased all-cause mortality with DCB-only strategy compared with DES-only approach, after > 3.5 years follow-up (median). Furthermore, there was no evidence of a difference in any of the secondary endpoints (cardiovascular mortality, ACS, stroke/TIA, major bleeding or unplanned TLR). Our results are consistent with previous registry data that have demonstrated the safety of DCB-only angioplasty and our previous study, SPARTAN DCB, which specifically showed no evidence of increased long-term mortality with DCB [10, 16]. In addition, we have demonstrated that the DCB-only strategy can compete with the DES-only strategy safely in routine clinical practice for overall mortality and all major cardiovascular endpoints, including unplanned TLR.

We included large numbers of patients with stable angina due to de novo disease and no restriction in vessel size. Approximately 73% of patients in the DCB group and 86% in the DES group had at least one vessel ≥ 3 mm treated, indicating that the great majority of patients had large vessels treated. When considering only patients with large-vessel disease, the results were similar to those observed in the whole population, showing no difference in all-cause mortality between DCB and DES (Supplementary Tables 3 and 4). These results are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated the safety of DCB-only angioplasty for de novo disease in large vessels [17]. A large proportion (49%) of the lesions treated with DCB had residual coronary dissections, mainly grade B. Consistent with previous work from our group, the rate of acute vessel closure was very low, as only one patient had acute vessel closure within 24 h [18].

Limitations

It is possible that the retrospective, non-randomised nature of our work from a single-centre could introduce referral bias. However, our institution is a large tertiary referral centre that provides cardiac intervention to a population over one million and has the highest implantation of DCBs for coronary artery disease in the UK [19]. Furthermore, we tried to ameliorate referral bias by including all consecutive patients fulfilling our criteria. Given that DCB-only angioplasty has a learning curve, as with most interventional techniques, our results might not be generalisable to smaller institutions with less experience in DCB-only angioplasty. In addition, it is vital to mention that even though our study is retrospective and non-randomised, our clinical database was completed prospectively, and the two groups were well balanced regarding patient characteristics. There were few differences only in terms of angiographic characteristics and recommended DAPT. Unfortunately, we do not have inflation pressures for the DCB or DES.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this is the first study to demonstrate that DCB-only angioplasty for stable angina due to de novo disease and predominantly large vessels, is safe compared to 2nd-generation DES as part of routine clinical practice. We have demonstrated that routine DCB-only strategy in patients with stable angina due to de novo disease of all vessel sizes has no increased all-cause mortality or any other major cardiovascular endpoints, including unplanned TLR, compared to DES.

Author contributions

IM, TG, VSV, MOM, MAM and SCE designed the study. IM drafted the manuscript. All co-authors made critical revisions and approved the manuscript. IM, TG and PR collected the data. IM, TG, VSV and SCE interpreted the data. SCE is the guarantor of the manuscript.

Funding

This is an investigator-initiated study partially supported by the National Institute for Health Research Capability Fund from Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital and B Braun Ltd. Dr Corballis was an NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow.

Availability of data and material

Data can be available following appropriate request to the authors.

Code availability

Not applicable.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

VSV received honoraria for speaking at conferences by Daiichi Sankyo and Novartis and a research grant from B Braun for investigator-initiated research. SCE received research grants for investigator-initiated research and lecture honoraria from B Braun. He also acts as a consultant for B Braun, Medtronic and MedAlliance. The other authors have nothing to declare.

Ethical approval

This study received approval from Northwest Haydock research ethics committee and institutional approval from the Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was not deemed necessary according to Confidentiality Advisory Group (17/CAG/0145).

Footnotes

Vassilios S. Vassiliou and Simon C. Eccleshall contributed equally to this work.

References

- 1.Neumann FJ, Sechtem U, Banning AP, et al. 2019 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of chronic coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2020;41(3):407–477. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yerasi C, Case BC, Forrestal BJ, et al. Drug-coated balloon for De Novo coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(9):1061–1073. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2019.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Merinopoulos I, Gunawardena T, Wickramarachchi U, Ryding A, Eccleshall S, Vassiliou V. Percutaneous coronary intervention in the elderly: are drug-coated balloons the future? Curr Cardiol Rev. 2018;14(1):45–52. doi: 10.2174/1573403X14666171226144120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jeger RV, Eccleshall S, Wan Ahmad WA, et al. Drug-coated balloons for coronary artery disease: third report of the International DCB Consensus Group. JACC Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;13(12):1391–1402. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.02.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fahrni G, Scheller B, Coslovsky M, et al. Drug-coated balloon versus drug-eluting stent in small coronary artery lesions: angiographic analysis from the BASKET-SMALL 2 trial. Clin Res Cardiol. 2020;109:1114–1124. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01603-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow M-A, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of drug-coated balloons versus drug-eluting stents for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): 3-year follow-up of a randomised, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2020;6736(20):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)32173-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeger RV, Farah A, Ohlow M, et al. Drug-coated balloons for small coronary artery disease (BASKET-SMALL 2): an open-label randomised non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2018;6736(18):1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31719-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jeger RV, Kaiser C, Mangner N, Kleber FX, Scheller B. Causes of death after treatment of small coronary artery disease with paclitaxel-coated balloons. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110(2):307–311. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01674-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yu X, Xu F, Zhang W, et al. Treatment of large de novo coronary lesions with paclitaxel-coated balloon only: results from a Chinese institute. Clin Res Cardiol. 2019;108(3):234–243. doi: 10.1007/s00392-018-1346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Merinopoulos I, Gunawardena T, Wickramarachchi U, et al. Long-term safety of paclitaxel drug-coated balloon-only angioplasty for de novo coronary artery disease: the SPARTAN DCB study. Clin Res Cardiol. 2021;110(2):220–227. doi: 10.1007/s00392-020-01734-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Park TK, Park YH, Song YB, et al. Long-term clinical outcomes of true and non-true bifurcation lesions according to medina classification—results from the COBIS (COronary BIfurcation stent) II registry. Circ J. 2015;79(9):1954–1962. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-15-0264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia-Garcia HM, McFadden EP, Farb A, et al. Standardized end point definitions for coronary intervention trials: the academic research consortium-2 consensus document. Circulation. 2018;137(24):2635–2650. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.029289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gilbert T, Neuburger J, Kraindler J, et al. Development and validation of a Hospital Frailty Risk Score focusing on older people in acute care settings using electronic hospital records: an observational study. Lancet. 2018;391(10132):1775–1782. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30668-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rahman Z, Ullah M, Choudhury A. Coronary artery dissection and perforation complicating percutaneous coronary intervention—a review. Cardiovasc J. 2011;3(2):239–247. doi: 10.3329/cardio.v3i2.9198. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neumann FJ, Sousa-Uva M, Ahlsson A, et al. 2018 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(2):87–165. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Venetsanos D, Lawesson SS, Panayi G, et al. Long-term efficacy of drug coated balloons compared with new generation drug-eluting stents for the treatment of de novo coronary artery lesions. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2018;92(5):E317–E326. doi: 10.1002/ccd.27548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenberg M, Waliszewski M, Krackhardt F, et al. Drug coated balloon-only strategy in de Novo Lesions of Large Coronary Vessels. J Interv Cardiol. 2019 doi: 10.1155/2019/6548696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merinopoulos I, Wickramarachchi U, Wardley J, et al. Day case discharge of patients treated with drug coated balloon only angioplasty for de novo coronary artery disease : a single center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020;95(1):105–108. doi: 10.1002/ccd.28217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludman PF. BCIS Audit returns adult interventional procedures. Published 2019. Accessed October 28, 2019. http://www.bcis.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/02/BCIS-Audit-2017-18-data-for-web-ALL-excl-TAVI-as-27-02-2019.pdf

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data can be available following appropriate request to the authors.

Not applicable.