Abstract

The aims of the this study are to select the best cultivation type for plant growth regulator (PGR) production, to optimize PGR production with statistical experimental design, and to calculate bioprocess parameters and yield factors during PGR production by P. eryngii in flask and reactor scales. Submerged fermentation was the best cultivation type with 4438.67 ± 37.14, 436.95 ± 27.31, and 54.32 ± 3.21 mg/L of GA3, ABA, and IAA production values, respectively. The Plackett–Burman and Box–Behnken designs were used to determine effective culture parameters and interactive effects of the selected culture parameters on PGR production by Pleurotus eryngii under submerged fermentation. The statistical model is valid for predicting PGR production by P. eryngii. After these studies, maximum PGR production (7926.17 ± 334.09, 634.92 ± 12.15, and 55.41 ± 4.38 mg/L for GA3, ABA, and IAA, respectively) was reached on the 18th day of fermentation under optimized conditions. The optimum formula was 50 g/L fructose, 3 g/L NaNO3, and 1.5 g/L KH2PO4, 1 mg/L thiamine, incubation temperature 25 °C, initial medium pH 7.0, and an agitation speed of 150 rpm. The kinetics of PGR production was investigated in batch cultivation under 3-L stirred tank reactor conditions. Concentrations of GA3, ABA, and IAA of 10,545.00 ± 527.25, 872.32 ± 21.81, and 60.48 ± 3.48 mg/L were obtained at the reactor scale which were 4.1, 3.4, and 2.3 times higher than the initial screening values. The specific growth rate (µ), the volumetric (rp) and specific (Qp) PGR production rates, 486.11 mg/L/day and 107.43 mg/g biomass/day for GA3, confirmed the successful transfer of optimized conditions to the reactor scale. In the presented study, PGR production of P. eryngii is reported for the first time.

Keywords: Abscisic acid, Gibberellic acid, Indole acetic acid

Introduction

Plant growth regulators (PGR) are produced not only by higher plants, but also by bacteria and fungi in relatively high quantities as secondary metabolites. Fungi are crucial for sustainable agriculture by controlling plant growth and development through PGR production. The PGRs, such as gibberellic acid (GA), indole acetic acid (IAA), abscisic acid (ABA), and zeatin, production by a lot of fungal species have been known for a long time (Curtis and Cross 1954; Gruen 1959; Epstein and Miles 1967).

Among a total of 136 structurally similar gibberellins, GA3 is the most important commercial product whose industrial production performed by submerged fermentation of Gibberella fujikuroi, renamed as Fusarium fujikuroi (Cen et al. 2023). However, the cost of the production is still the main issue, ranging around $150–1200/kg in the international market (according to Alibaba.com, accessed in 02.27.2023), and high GA yielding strains are strongly demanded.

Although many studies have been conducted to isolate or to improve high PGR yielding strains by screening/mutagenesis, the GA and other PGRs titer is still very low level after such a long period of effort (Cen et al. 2023). Most of these studies were performed with microfungus species such as Aspergillus fumigatus (Hamayun et al. 2009), A. niger (Başıaçık Karakoç and Aksöz 2005; Seyis Bilkay et al. 2010; Monrro and Garcia 2022), F. fujikuroi (Shukla et al. 2005; Werle et al. 2020; Cen et al. 2023), F. moniliforme (Rangaswamy 2012), Gliomastix murorum (Khan et al. 2009), and Paecilomyces sp. (El-Sheikh et al. 2020). However, the production of PGRs by macrofungi species has also been reported including Agrocybe praecox (Fushimi et al. 2012), Armillaria sp. (Kobori et al. 2015), Hericium erinaceus (Wu et al. 2019), Inonotus hispidus (Doğan et al. 2023), and Stropharia rugosoannulata (Wu et al. 2013).

Different Pleurotus species were also reported for their PGR production such as P. ostreatus (Bose et al. 2013) and P. pulmonarius (Pham et al. 2019). In addition, the gibberellic acid and auxin-like activity of P. sajor-caju was reported by Valentino and Galvez (2015). On the other hand, according to the relevant literature, only IAA has been reported for PGR production by P. eryngii (Tiryaki and Gülmez 2021). However, no studies have been conducted in which P. eryngii was used for the production of GA3 and ABA.

Pleurotus eryngii (Pleurotaceae, Agaricomycetes), known as the king oyster mushroom in the USA and UK, “seta de cardo” in Spain, “pleurote du panicaut” in France, “fungo cardoncello” in Italy, “Braune Kräuter-Seitling” in Germany, and “çakşır mantarı” in Türkiye, is a typical fungus of the subtropics and steppes, as well as being a famous edible mushroom worldwide (Carlavilla and Manjón 2023). Other than having high biotechnological importance, it has anti-angiogenetic (Shenbhgaraman et al. 2012), cholesterol lowering (Alam et al. 2011), immunomodulating, antitumor, antimicrobial, antiviral, and antiosteoporotic (Stajić et al. 2009) activities, because of its bioactive components such as polysaccharides (Liu et al. 2010), sterols (Yaoita et al. 2002), fatty acids, and vitamins (Akyüz et al. 2011), lovastatin, pleureryn, eryngin, 17β-estradiol, eryngeolysin, and ergothioneine (Stajić et al. 2009).

P. eryngii grows in association with living plants (family Apiaceae, genera Eryngium, Ferula, Ferulago, Cachrys, Laserpitium, Diplotaenia and Elaeoselinum) from autumn until late spring when environmental conditions are favorable (Zervakis et al. 2001). Recently, Carlavilla and Manjón (2023) carried out a study to resolve the controversial relationship between P. eryngii and Eryngium campestre and other umbellifers and showed that P. eryngii is a facultative necrotrophic parasite of E. campestre under natural conditions. Although related to living plants, PGR production of this fungus has not been reported yet. The aims of the presented study are as follows: (a) to select the best cultivation type for PGR production; (b) to optimize PGR production condition by statistical experimental design; (c) to produce PGR in stirred tank reactor conditions; and (d) to calculate bioprocess parameters and yield factors during PGR production by P. eryngii.

Materials and methods

Microorganism

The used plant growth regulator producing Pleurotus eryngii isolate was chosen with a screening program among 104 Basidiomycetes isolates comparing with positive controls, Fusarium fujikuroi isolates (unpublished data). The Pleurotus eryngii isolate was kindly donated by Abdunnasır Yıldız (Dicle University, Türkiye), maintained on a potato dextrose agar slants at 4 °C, and refreshed periodically.

To confirm GA3, ABA, and IAA presence in the P. eryngii culture fluid extract, thin layer chromatography (TLC) was conducted according to the methods of Machado et al. (2002), Takayama et al. (1983), and Swain and Ray (2008), respectively. Plant growth regulators were detected on TLC plates on aluminium sheets coated with silica gel 60F 254 (Merck) after development by spraying their reagents resulting in corresponding coloring under UV (254 nm) or daylight. The Rf values for GA3, ABA, and IAA in the fungal extract were determined as 0.63, 0.60, and 0.49 which were the same as the corresponding standard.

Inoculum preparation

To prepare inoculum, five mycelial discs of 6 mm diameter from the actively growing part of the fungal colony were inoculated to 100 mL potato malt peptone (PMP) broth (g/L: potato dextrose broth 24.0, malt extract 10.0, and peptone 1.0) and incubated at 28 °C, 100 rpm for 4 days. After incubation, the harvested cells were washed with sterile distilled water (SDW) three times and the total volume was adjusted to 100 mL with SDW. The inoculant was prepared by way of homogenization of the cell suspension for 20 s with 1−min intervals (Silent Crusher M, Heidolph, Germany). The mycelial suspension was used as inocula 4% for all sections of the study (Bayburt et al. 2020).

Culture type selection

Submerged (SmF), static (SF), and solid state fermentation (SSF) types were evaluated during 24 days of the incubation period to select the most suitable cultivation type for PGR production by Pleurotus eryngii. The cultures were incubated at 30 °C and samples were removed at 3-day intervals in all culture types.

In the SmF and SF culture types, 4% mycelial slurry was inoculated to 100 mL of modified Czapek Dox medium (CDM, g/L, 30.0 sucrose, 3.0 NaNO3, 1.0 KH2PO4, 0.5 MgSO4·7H2O, 0.5 KCl, and 5.0 tryptone). Agitated at 150 rpm and non-agitated culture conditions were applied for the SmF and SF, respectively. The SSF cultures were conducted in 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 5 g of dried and ground sugar beet which is the best choice for SSF conditions due to its high sucrose content. The humidity of the substrate was adjusted to 70% (w/v) by the addition of 13 mL modified CDM without sucrose. All of the inoculated cultures were maintained at 30 °C for 24 days.

For sampling the SSF cultures, 100 mL of sterile distilled water was added to the cultures and shaken for 2 h at 4 °C. Periodically taken samples in all the culture types were filtered (Whatman No: 1), centrifuged at 5000 rpm for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatants were used in analyses for PGR, total carbon and nitrogen amounts.

Selection and optimization of culture parameters

To select positively influenced culture parameters, and to determine the relative importance of each screened culture parameter for improved PGR production by P. eryngii, a two-level factorial design, Plackett–Burman design (PBD), was used (Plackett and Burman 1946). The low (coded − 1) and high (coded + 1) levels of each culture parameter are presented in Table 1. Here, n + 1 orthogonal design with 16 experimental runs were prepared with 15 culture parameters (Table 2).

Table 1.

Independent variables and their levels in the Plackett–Burman design

| Variables | Low levels (− 1) | High levels (+ 1) |

|---|---|---|

| (X1) Glucose (%) | 0 | 3 |

| (X2) Lactose (%) | 0 | 3 |

| (X3) Sucrose (%) | 0 | 3 |

| (X4) Fructose (%) | 0 | 3 |

| (X5) NaNO3 (%) | 0 | 0.3 |

| (X6) NH4NO3 (%) | 0 | 0.3 |

| (X7) Yeast ekstrakt (%) | 0 | 0.3 |

| (X8) Tryptone (%) | 0 | 0.3 |

| (X9) FeSO4 (%) | 0 | 0.1 |

| (X10) MgSO4 (%) | 0 | 0.1 |

| (X11) KH2PO4 (%) | 0 | 0.1 |

| (X12) Thiamine (µg/l) | 0 | 1000 |

| (X13) Incubation temperature (°C) | 25 | 35 |

| (X14) Medium pH | 4 | 7 |

| (X15) Agitation (rpm) | 100 | 200 |

Table 2.

Plackett–Burman design matrix and observed PGR production by Pleurotus eryngii

| Run | Independent variables (X)a | Responses (mg/L) | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | GA3 | ABA | IAA | |

| 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 4 | 100 | 594.50 | 104.62 | 17.49 |

| 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 25 | 4 | 200 | 4406.83 | 433.00 | 53.21 |

| 3 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 7 | 200 | 3191.17 | 389.27 | 33.28 |

| 4 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 7 | 200 | 15.83 | 16.36 | 2.54 |

| 5 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 35 | 7 | 200 | 3327.00 | 344.32 | 29.74 |

| 6 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 35 | 7 | 100 | 2609.50 | 259.62 | 32.37 |

| 7 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 35 | 4 | 200 | 1582.00 | 167.27 | 20.16 |

| 8 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 1 | 25 | 7 | 100 | 6904.33 | 741.67 | 51.29 |

| 9 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 35 | 4 | 200 | 2891.17 | 258.56 | 22.52 |

| 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 25 | 7 | 200 | 391.17 | 44.55 | 3.56 |

| 11 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 35 | 7 | 100 | 316.17 | 29.85 | 1.82 |

| 12 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 1 | 35 | 4 | 100 | 1562.00 | 145.23 | 10.62 |

| 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0 | 0.1 | 1 | 25 | 4 | 200 | 4349.50 | 469.39 | 28.57 |

| 14 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 25 | 7 | 100 | 4362.00 | 533.26 | 38.01 |

| 15 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.3 | 0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 | 35 | 4 | 100 | 2471.17 | 222.58 | 12.74 |

| 16 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 25 | 4 | 100 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

aCarbon source (%): X1 glucose, X2 lactose, X3 sucrose, X4 fructose; nitrogen source (%): X5 NaNO3, X6 NH4NO3, X7 yeast extract, X8 tryptone; mineral source (%): X9 FeSO4, X10 MgSO4, X11 KH2PO4, others; X12 thiamine (mg/L), X13 temperature (°C), X14 pH, X15 agitation (rpm)

Fructose, NaNO3, and KH2PO4 were found to be effective parameters on PGR production in the PB design. Here, three different levels (i.e., high [+ 1], medium [0], and low [− 1]) of fructose (10, 30, 50 g/L), NaNO3 (1, 3, 5 g/L), and KH2PO4 (0.5, 1, 1.5 g/L) were tested to determine the optimum levels and the interactive effects of these variables with the use of response surface methodology (RSM) using the Box–Behnken design (BBD) in 15 trials. The quadratic equation for analysis is presented below.

| 1 |

where yield (Y) is the predicted response, β0 is the model intercept term, βi is the linear effect, βii is the quadratic effect, βij is the interaction effect, and xi and xj are the coded values of independent variables. The graphical regression analysis of the experimental data was performed from Statistica 12.0 software (StatSoft, Tulsa, OK, USA). All the experiments were carried out in triplicate and the mean values of the PGR production were considered as the response (p < 0.05). The analysis of variance (ANOVA), coefficient determination as well as p and f values were used to validate against the predicted response of BBD.

PGR production and kinetic parameters in flask and stirred tank reactor

After optimization studies, to determine bioprocess parameters and yield factors, time-dependent PGR production by P. eryngii was monitored under non-optimized and optimized conditions in the flask scale and under optimized conditions in the 3-L stirred reactor scale (STR; Bioflo 110, New Brunswick). The reactor with two Rushton impellers equipped with pH and dissolved oxygen electrodes was used in a working volume of 1.7 L and an aeration rate of 1 vvm in optimized conditions. Biomass, carbon source, and PGR values were determined in the samples taken periodically during the 20 days of the incubation period. Temperature, pH, and dissolved oxygen values were also monitored by Bio Command Plus connected to the reactor during the incubation.

Kinetic parameters were studied under non-optimized or optimized conditions in Erlenmeyer and reactor scales. Biomass, carbon source, PGR amounts, and pH values were determined in periodically taken samples during the 15 days of the incubation period. Bioprocess parameters and yield factors were calculated according to the following formulas proposed by Hwang et al. (2004) and Shukla et al. (2005).

| 2 |

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

| 6 |

| 7 |

| 8 |

| 9 |

where X: biomass amount (g/L), P: PGR concentration (mg/L), t: time (day), S: carbon source amount (g/L).

Analytical methods

The samples were collected daily in triplicate for 20 days to determine biomass, carbon source, nitrogen source, and PGR values. To determine the produced biomass value, the harvested pellets were washed with sterile distilled water three times, and dried to a constant weight at 60 °C. The phenol sulphuric acid (Dubois et al. 1956) and Berthelot (Gordon et al. 1978) methods were used to determine the carbon and nitrogen sources, respectively.

To decide the assay method for PGR produced by P. eryngii, the results of spectrophotometric and HPLC methods for GA3 assay (10–200 mg/L) were compared. Standard curves and regression graph for the HPLC and spectrophotometer data were presented elsewhere (Doğan et al. 2023). The determination coefficient (R2) values of the model and the standard curves of the spectrophotometric and HPLC methods (0.9925, 0.9984, and 0.9941, respectively) show that the spectrophotometric method can be used instead of the time-consuming and expensive HPLC method. Therefore, the quantitative assay of GA3, ABA, and IAA was performed with the spectrophotometric methods proposed by Ünyayar et al. (1996) in the following steps of the study. For this purpose, first, the culture broth of P. eryngii was filtered (Whatman no 1) and centrifuged (2000×g for 10 min). The pH value of the supernatant was adjusted to 2.5 using 1N HCl and extracted three times with ethyl acetate. The absorbance for GA3, ABA, and IAA was measured at 254, 263, and 280 nm, respectively, and their amounts were calculated using the standard curves (Doğan et al. 2023). The uninoculated medium and ethyl acetate were used as a negative control and blank in the assay, respectively.

Results

Culture type selection

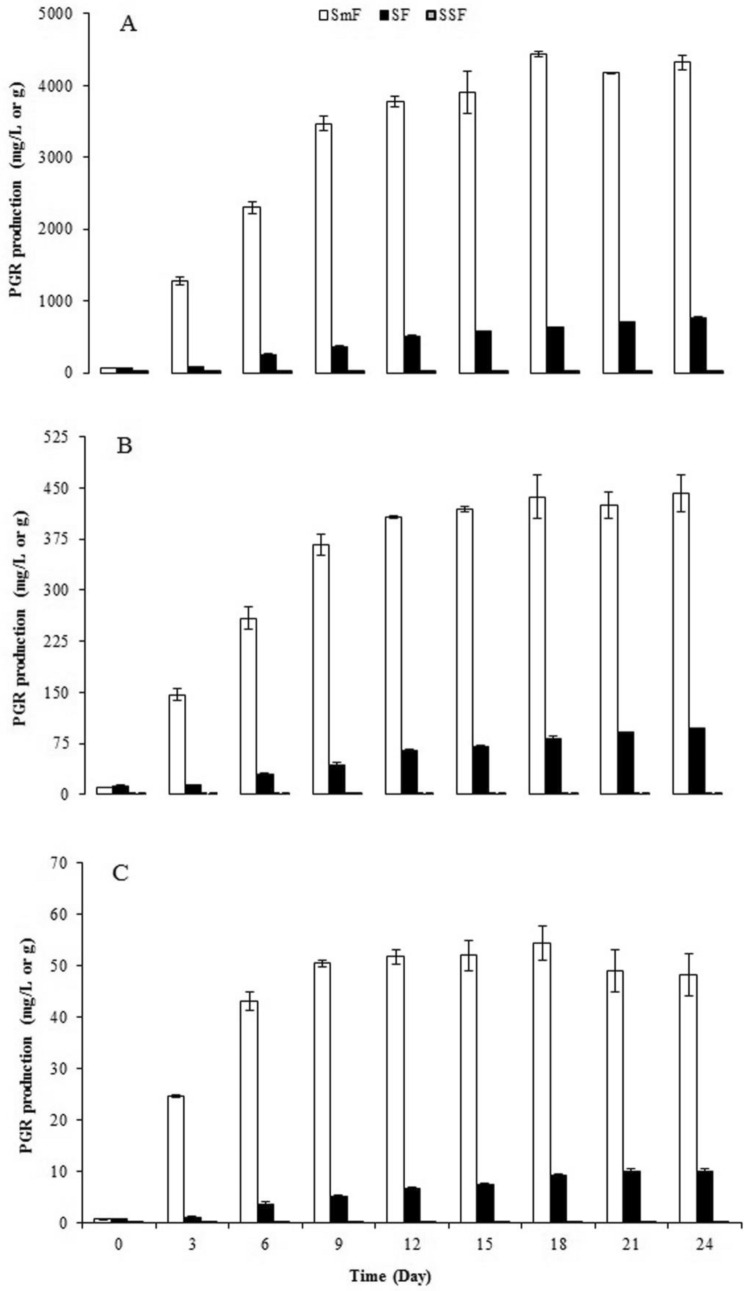

To select the best culture type, PGR production by P. eryngii was carried out using SmF, SF, SSF types during a 24-day incubation period. It was found that P. eryngii was able to produce PGR under the three culture types evaluated. Time-dependent production values of GA3, ABA, and IAA for all culture types are presented in Fig. 1. The best culture type for all three PGR production was SmF, which was used in further studies.

Fig. 1.

GA3 (A), ABA (B), and IAA (C) production by Pleurotus eryngii under different culture conditions

Selection and optimization of culture parameters

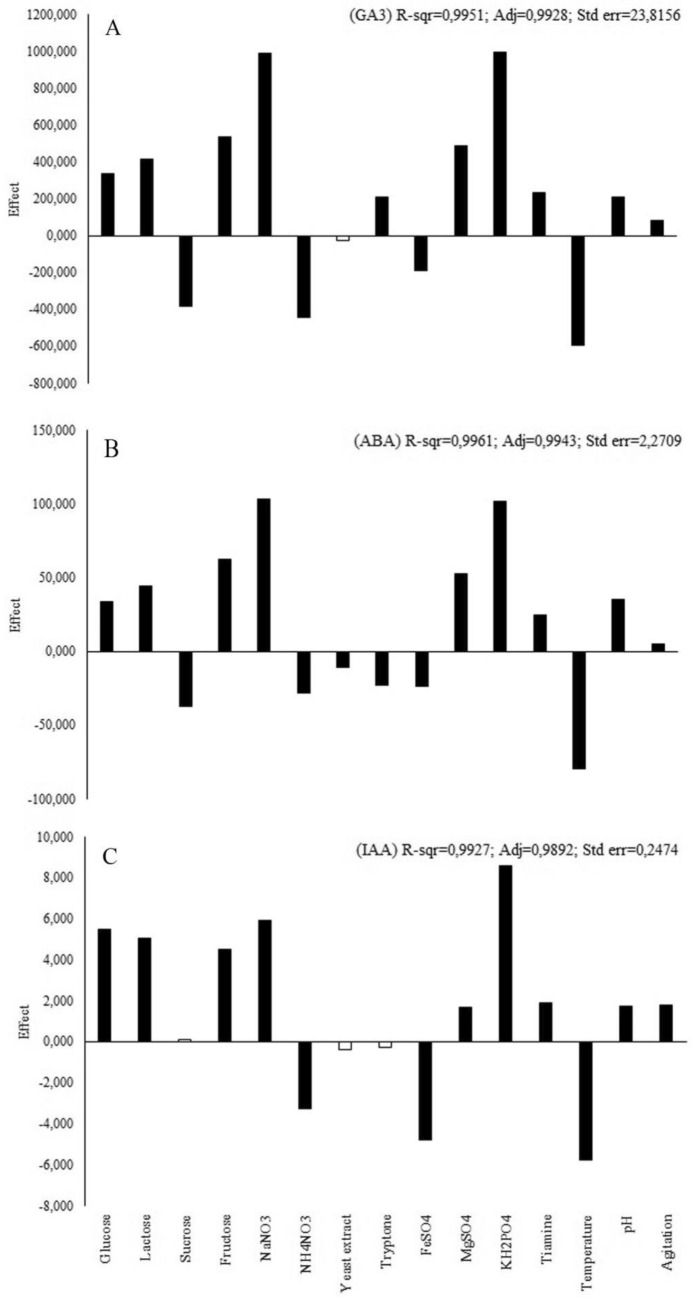

In all optimization studies, the amounts of PGR produced by P. eryngii were determined at 18 days of incubation, depending on the results of the culture type selection studies. The highest responses for GA3, ABA, and IAA production were obtained as 6904.33 ± 30.44, 741.67 ± 6.58, and 51.29 ± 2.73 mg/L, respectively, after the PB studies (Table 2). To present the order of significance of all the studied variables for PGR production by P. eryngii with SmF culture type, a Pareto chart was prepared for each PGR (Fig. 2). Among all the independent variables tested, fructose as a carbon source, NaNO3 as a nitrogen source, and KH2PO4 as a mineral source were the most significant variables (p < 0.05). To determine their exact concentrations and interactive effects on the PGR production of P. eryngii, they were selected for further optimization studies with RSM.

Fig. 2.

The effect of the culture parameters on GA3 (A), ABA (B), and IAA (C) production by Pleurotus eryngii. Black color: significant at p ≤ 0.05

The experimental design, predicted and observed responses are shown in Table 3. The obtained highest concentrations for GA3, ABA, and IAA production were obtained as 7926.17 ± 334.09, 634.92 ± 12.15, and 55.41 ± 4.38 mg/L, respectively, after the BBD studies (Table 3). The ANOVA results of the quadratic regression model are summarized in Table 4. A relatively good degree of agreement between the predicted and observed data was obtained with determination coefficients (R2) of 0.7192, 0.6686, and 0.8797 for GA3, ABA, and IAA production. Among the tested independent variables, fructose and KH2PO4 were the most significant for all PGR (p < 0.001) which indicates that these variables had the maximum effect on PGR production by P. eryngii. On the other hand, the effect of NaNO3 was non-significant for GA3 and ABA production (p = 0.0683 and 0.4308, respectively), but significant for IAA production (p = 0.038).

Table 3.

The predicted and experimentally observed responses for PGR production by P. eryngii

| Run | Independent variables (%) | Responses (mg/L) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fructose | NaNO3 | KH2PO4 | GA3 | ABA | IAA | ||||

| Predicted | Observed | Predicted | Observed | Predicted | Observed | ||||

| 1 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 5702.56 | 6692.83 | 431.77 | 518.64 | 34.87 | 39.41 |

| 2 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.05 | 4204.63 | 4630.33 | 314.94 | 361.44 | 23.04 | 23.07 |

| 3 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 7074.42 | 7926.17 | 560.55 | 634.92 | 51.76 | 55.41 |

| 4 | 3 | 0.5 | 0.15 | 6769.21 | 6538.67 | 525.07 | 494.02 | 40.14 | 37.12 |

| 5 | 5 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 5587.54 | 4966.33 | 446.82 | 403.50 | 39.97 | 40.24 |

| 6 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 5702.56 | 5742.83 | 431.77 | 444.77 | 34.87 | 35.32 |

| 7 | 3 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 5703.56 | 4672.00 | 431.77 | 331.89 | 34.87 | 29.87 |

| 8 | 1 | 0.5 | 0.1 | 4275.13 | 4701.17 | 331.22 | 359.09 | 23.43 | 27.03 |

| 9 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.15 | 5841.04 | 5405.33 | 467.03 | 420.53 | 43.61 | 43.57 |

| 10 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 6067.50 | 5872.00 | 429.85 | 433.03 | 31.78 | 31.20 |

| 11 | 1 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 3727.92 | 2876.17 | 280.89 | 206.52 | 17.09 | 13.45 |

| 12 | 5 | 0.3 | 0.05 | 5064.00 | 5259.50 | 365.00 | 361.82 | 31.99 | 32.57 |

| 13 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 3867.46 | 4488.67 | 319.25 | 362.58 | 25.87 | 26.49 |

| 14 | 3 | 0.1 | 0.05 | 4045.63 | 4276.17 | 332.66 | 363.71 | 26.26 | 29.28 |

| 15 | 5 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 4898.04 | 4472.00 | 418.48 | 390.61 | 44.22 | 40.62 |

Table 4.

The ANOVA table for PGR production by P. eryngii

| PGR | Source | Sum of squares (SS) | Degree of freedom (DF) | Mean squares (MS) | F value | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GA3 | Model | 45,742,732 | 9 | 5,082,525.778 | 9.959 | < 0.01 |

| Residual | 17,862,006 | 35 | 510,343.028 | |||

| Total sum of squares | 63,604,738 | 44 | ||||

| Determination coefficient (R2) = 0.7192, correlation coefficient (R) = 0.8481 | ||||||

| ABA | Model | 270,875.5 | 9 | 30,097.277 | 7.844 | < 0.01 |

| Residual | 134,292.3 | 35 | 3836.922 | |||

| Total sum of squares | 405,167.8 | 44 | ||||

| Determination coefficient (R2) = 0.6686, correlation coefficient (R) = 0.8176 | ||||||

| IAA | Model | 3714.723 | 9 | 412.747 | 28.445 | < 0.01 |

| Residual | 507.859 | 35 | 14.51 | |||

| Total sum of squares | 4222.582 | 44 | ||||

| Determination coefficient (R2) = 0.8797, correlation coefficient (R) = 0.9375 | ||||||

Statistical analysis of the quadratic regression model indicates that the model term has a low probability value (p < 0.01, Table 4). The following second-order polynomial equations can be expressed to predicted responses for PGR production by P. eryngii (Y).

where X1, X2, and X3 are fructose, NaNO3, and KH2PO4, respectively.

From the equations, the positive interaction of NaNO3 with fructose and KH2PO4 was clear. These interactions can be seen in the 3D surface plots which can help describe the effect of the two independent variables on response while keeping the third variable constant (Fig. 3). The optimum concentrations of the fructose, NaNO3, and KH2PO4 were also determined using a total of 15 runs with the BBD. As a result of statistical optimization studies, it can be argued that the optimal conditions were as follows: 50 g/L fructose; 3 g/L NaNO3; 1.5 g/L KH2PO4; 1 mg/L thiamine; an incubation temperature of 25 °C; an initial medium pH 7.0; and an agitation speed of 150 rpm to obtain maximum PGR yield by P. eryngii.

Fig. 3.

Response surface plots of the experimental variables for GA3 (A), ABA (B), and IAA (C) production by Pleurotus eryngii

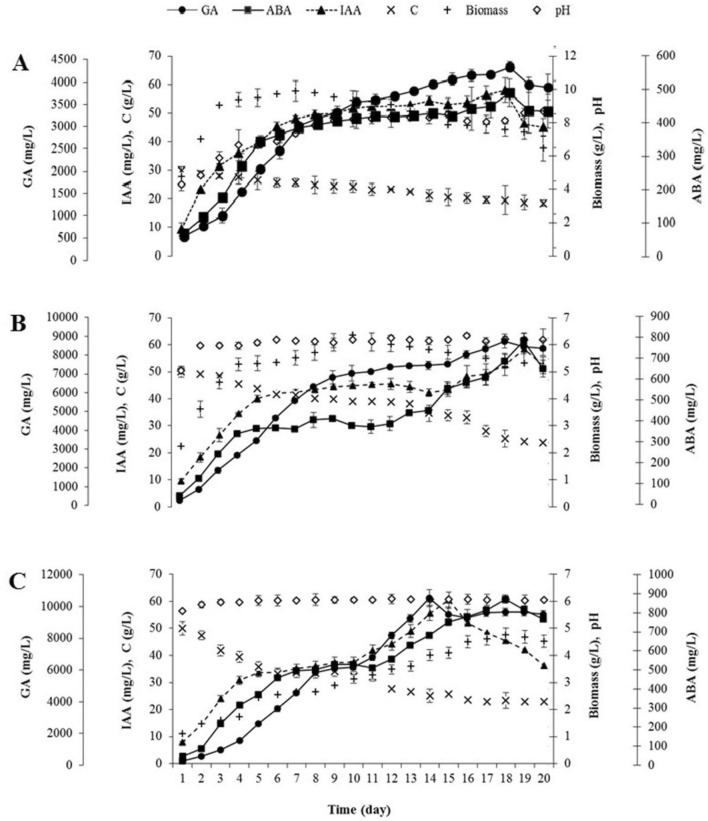

PGR production and kinetic parameters in flask and stirred tank reactor

A calculation of bioprocess parameters and yield factors was performed with time-dependent studies under non-optimized and optimized conditions in the flask scale and under optimized conditions in the reactor scale. As shown in Fig. 4, PGR concentrations increased while the carbon source decreased during the entire fermentation process under (A) non-optimized and (B) optimized conditions in the flask scale, and (C) optimized conditions in the 3-L reactor scale.

Fig. 4.

Growth curve of the P. eryngii under A the non-optimized and B the optimized conditions in the flask scale and C under the optimized conditions in the reactor scale

The highest production of GA3, ABA, and IAA under non-optimized conditions in the flask scale was 4060.38 ± 108.36, 463.50 ± 41.04, and 58.07 ± 4.21 mg/L, respectively, 18 days later. The mycelial biomass reached a maximum value of 9.90 ± 0.60 g/L on the 7th day of incubation, followed by a plateau for 6 days, with a slight decrease in the last period being observed. The carbon source, sucrose, remained in the medium at the rate of 62% at the end of the incubation period. On the other hand, GA3, ABA, and IAA values were determined as 8743.08 ± 365.41, 787.23 ± 35.05, and 58.35 ± 4.48 mg/L under optimized conditions in the flask scale. GA3 and ABA concentrations in the optimized conditions were 2.15 and 1.70 times higher than non-optimized conditions in the flask scale, respectively, while the IAA concentrations were the same. A maximum mycelial biomass value was 6.36 ± 0.21 g/L by the 10th day of incubation. Fructose, which was chosen as the carbon source in optimization studies, in the medium was consumed at the rate of 52%. (Fig. 4A, B). This means that fructose is a preferred carbon source by P. eryngii in PGR production.

Regarding the reactor scale, a GA3 concentration of 10.545.00 ± 527.25 mg/L was achieved after 14 days as the peak value in this study. This concentration was 2.60-fold and 1.21-fold higher than the values obtained under the flask scale non-optimized and optimized conditions, respectively. In addition, ABA and IAA concentrations of 872.32 ± 21.81 and 60.48 ± 3.48 mg/L were reached after 18 and 15 days of incubation, respectively. The reactor-scale ABA production was 1.88 and 1.11 times higher than the flask-scale non-optimized and optimized conditions, respectively, while IAA concentration in the reactor scale was almost the same with both flask scales. The pattern of the mycelial biomass and carbon source in the reactor scale was almost identical to the optimized conditions in the flask scale (Fig. 4C). We can argue that the optimal conditions of the flask scale were successfully transferred to the reactor scale.

Discussion

Culture type selection

It is well known that secondary metabolite production is highly dependent on the cultivation method of fungi. Compared with the other culture types, SmF promoted the maximum PGR production by P. eryngii. As reported by Silva et al. (2000) and Lale and Gadre (2016), the high dissolved oxygen concentration in the medium is an important factor for PGR production which may explain the superiority of SmF over other culture types. The fermentation of P. eryngii cells in SmF conditions presented a well-known behavior. All the PGRs reached their maximum levels during the secondary growth stage in fermentation depending on carbon limitations. Concerning GA3 production, its highest amount corresponding to 4438.67 ± 37.14 mg/L was observed on day 18 during the exponential growth phase in the SmF culture type. This value is fairly high when compared with the results reported for the best-known producer F. fujikuroi which was in the range of 273 mg/L (de Oliveria et al. 2017)–3900 mg/L (Silva et al. 2000) under the same culture conditions even if they were performed in different reactor types. To produce GA3 in STR, de Oliveria et al. (2017) preferred to use citric pulp as the substrate, a waste remaining from the extraction of orange juice. On the other hand, Silva et al. (2000) used a chemically defined medium in the fluidized bed reactor. As can be seen from these reports, differences in nutritional and environmental conditions may result in different PGR production by the same species.

In a comparative study, F. moniliforme presented an impressive GA3 titer, 15,000 mg/L, under optimized SmF conditions compared to SF conditions, 105 mg/g (Rangaswamy 2012). In this study, Czapek Dox medium was used as a medium. The optimum conditions for F. moniliforme were pH: 7.0, 30 °C incubation temperature, and sucrose and glucose as carbon source. On the other hand, the optimum conditions for P. eryngii were pH: 7.0, 25 °C incubation temperature, fructose as a carbon source. We argue that incubation temperature and carbon source are effective factors on GA3 production other than genetic diversity.

There are relatively few studies on macrofungi isolates in the literature. Production of 380.00, 475.40, and 2478.85 mg/L GA3 has been reported for Phanerochaete chrysosporium, Funalia trogii, and Inonotus hispidus, respectively (Ünyayar et al. 1996; Yürekli et al. 1999; Doğan et al. 2023). On the other hand, the GA3 production value of P. eryngii was determined as 4438.67 mg/L on the 18th day under SmF conditions which is 5.75 times higher than the GA3 yield with SF, 771.83 mg/L on day 24, which depends on the higher dissolved oxygen concentration and cellular respiration. Regarding the SSF, the maximum GA3 amount, 17.29 mg/g, was obtained on day 9, which is relatively higher than reported for Fusarium moniliforme (7.6 mg/g, de Oliveria et al. 2017). According to Machado et al. (2002), G. fujikuroi offers a 6.1 times higher GA3 yield with SSF than SmF, in contrast to our results.

In the case of ABA and IAA production, higher values were also achieved for the SmF culture type. A plateau for ABA and IAA production was observed after 15 and 9 days of incubation, respectively. It was reached maximum ABA and IAA amounts, 436.95 ± 27.31 mg/L and 54.32 ± 3.21 mg/L, respectively, on day 24 and day 18 of incubation, respectively. These values were 4.56 and 5.33 times higher than achieved for the SF cultivations under the same conditions. Overall, depending on the results obtained at this step, the next stages of the study were carried out with the SmF culture type.

Selection and optimization of culture parameters

Statistical experimental design studies can maximize the obtained results from a limited number of individual experiments. According to the data obtained, the GA3, ABA, and IAA amount produced in the optimized fermentation media with the Plackett–Burman experimental design were 2.68, 2.90, and 1.98 times higher than that produced under unoptimized media by P. eryngii, respectively. On the other hand, it can be seen that the PGR production values after the response surface method are 3.07, 2.49, and 2.13 times higher than the initial values, respectively (Table 5) confirming that the production has been successfully optimized. A limited number of studies have been published in the literature, in particular on the statistical optimization of PGR production with the microfungus species (Silva et al. 2000; Isa and Don 2014; Werle et al. 2020; Wang et al. 2022). However, due to a lack of studies with the statistical optimization of PGR production by macrofungi isolates, no comparison could be performed. In the only study, under optimized conditions in the flask scale by I. hispidus, the concentration of GA3, ABA, and IAA reached their maximum levels of 5473.37 ± 201.24, 573.77 ± 18.16, and 76.13 ± 3.10 mg/L, respectively (Doğan et al. 2023). The GA3 and IAA values presented by P. eryngii after BBD studies were higher than produced by I. hispidus.

Table 5.

PGR production values under non-optimized and optimized conditions (mg/L) under the flask scale

| Production conditions | GA3 | ABA | IAA |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-optimized (screening step, 10th day) | 2580.50 | 255.49 | 25.96 |

| Non-optimized (SmF conditions, 18th day) | 4438.67 | 436.95 | 54.32 |

| After PB (18th day) | 6904.33 | 741.67 | 51.29 |

| After RSM (18th day) | 7926.17 | 634.92 | 55.41 |

PGR production and kinetic parameters in flask and stirred tank reactor

Gibberellic acid has received the greatest attention in the literature according to other PGR substances. Its production ranged from 180.37 (Yürekli et al. 1999) to 5441.54 mg/L (Doğan et al. 2023) by Trametes versicolor and Inonotus hispidus, respectively, in the submerged fermentation system in the flask/reactor scale by macrofungi species. On the other hand, the maximum ABA and IAA values of macrofungi species were obtained from Inonotus hispidus (Doğan et al. 2023) and Phanerochaete chrysosporium (Bose et al. 2013), 390 and 840 mg/L respectively. As a result, our maximum GA3 and ABA data of 10,545.00 and 872.32 mg/L, respectively, were extremely superior to all other data reported for macrofungi species (Ünyayar et al. 1996, 2000; Yürekli et al. 1999, 2003; Bose et al. 2013; Pham et al. 2019; Doğan et al. 2023), and the best-known producer F. fujikuroi in flask (Silva et al. 1999; Durán-Páramo et al. 2004; Shukla et al. 2005; de Oliveria et al. 2017; Zhang et al. 2020) and reactor scales (Silva et al. 1999, 2000; Durán-Páramo et al. 2004; Shukla et al. 2005; de Oliveria et al. 2017; Wei et al. 2019), so far. The increase in production and productivity of PGR in STR can be associated with the influence of the higher aeration rate of 1 vvm and mechanical agitation providing good homogeneity.

A mathematical model for PGR production under SmF conditions was first proposed by Shukla et al (2005) and is rare in literature. In this study, to calculate the kinetic parameters, the amounts of produced biomass (X), consumed carbon source (S), and produced PGR (P) by P. eryngii were monitored during the 20 days of incubation period in flask and reactor scales. The kinetic parameters of non-optimized and optimized conditions during cultivation of P. eryngii in both scales are shown in Table 6. According to the data obtained, the specific growth rate (µ) of the organism seems to decrease gradually. Similar to this study, Shukla et al (2005) reported a decrease in specific growth rate values, when the substrate concentration is increased which may cause a change in the C/N ratio. On the other hand, it can be seen that the daily volumetric (rs) and specific (Qs) carbon source consumption rate increases. P. eryngii consumes only 0.61 g of the carbon source per liter of medium per day on a flask scale under non-optimized conditions during incubation. However, this value increases to 1.42 g at the reactor scale under optimized conditions. We believe that increased reactor-scale carbon source consumption by P. eryngii is associated with PGR production. In fact, although the specific growth rate (µ) relatively decreases from non-optimized flask conditions to optimized reactor conditions, it can be seen that the amount of PGR produced per liter medium (rp) and per gram biomass (Qp) increases significantly for both GA3 and ABA. Although there is a slight decrease in IAA, we believe that this situation can easily be neglected due to the low production value.

Table 6.

Growth kinetics and yield coefficient data of P. eryngii at flask and reactor scales

| Kinetic parameters | Trials | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-optimized (flask scale) | Optimized (flask scale) | Optimized (bioreactor scale) | |

| µ (1/day) | 0.32 | 0.28 | 0.08 |

| rs (g/L/day) | − 0.61 | − 1.38 | − 1.42 |

| Qs (g/g/day) | − 0.09 | − 0.27 | − 0.31 |

| GA | |||

| rp (mg/L/day) | 177.00 | 425.71 | 486.11 |

| Qp (mg/g/day) | 27.40 | 82.82 | 107.43 |

| ABA | |||

| rp (mg/L/day) | 19.23 | 31.98 | 38.04 |

| Qp (mg/g/day) | 2.98 | 6.22 | 8.41 |

| IAA | |||

| rp (mg/L/day) | 1.89 | 2.25 | 1.49 |

| Qp (mg/g/day) | 0.29 | 0.44 | 0.33 |

| Yx/s (g/g) | 0.56 | 0.20 | 0.17 |

| GA | |||

| Yp/s (mg/g) | 291.14 | 308.82 | 341.47 |

| Yp/x (mg/g) | 520.59 | 1573.65 | 2041.14 |

| ABA | |||

| Yp/s (mg/g) | 31.64 | 23.20 | 26.72 |

| Yp/x (mg/g) | 56.57 | 118.20 | 159.72 |

| IAA | |||

| Yp/s (mg/g) | 3.10 | 1.63 | 1.05 |

| Yp/x (mg/g) | 5.54 | 8.33 | 6.27 |

When the yield parameters are examined, the situation is similar. The amount of biomass produced per gram of substrate consumed by the organism (Yx/s) decreases from non-optimized flask conditions to optimized reactor conditions. This situation is associated with a gradual decrease in the specific growth rate (µ) of P. eryngii. Moreover, there is a significant increase in both the PGR value produced per gram of substrate (Yp/s) and the PGR value produced per gram of biomass (Yp/x). Considering that the daily amount of GA3 produced per liter of medium (rp) is 486.11 mg and the total amount of GA3 produced by each gram of biomass (Yp/x) is 2041.14 mg, an economic production potential will appear. F. fujikuroi (Durán-Páramo et al. 2004) and Inonotus hispidus (Doğan et al. 2023) have presented yields of 78.00 and 805.34 mg of GA3 per gram biomass (Yp/x), respectively, in a stirred tank reactor in previous studies. However, 2041.14 mg GA3 was produced by each gram biomass of P. eryngii, which is the highest value in the literature. On the other hand, while the productivity of the GA3 by F. moniliforme was reported as 68.16 mg/L/day by de Oliveira et al. (2017), this value was 486.11 mg/L/day for P. eryngii in this study. These data show that the organism not only achieves reactor-scale PGR production, but also significantly increases it. For this reason, we can argue that P. eryngii has an extremely important potential for industrial-scale production of PGR, and GA3 in particular.

Conclusion

In this presented first report for PGR production by P. eryngii, the produced GA3, ABA, and IAA concentrations were 10,545.00, 872.32, and 60.48 mg/L, respectively, under the optimized conditions of 50 g/L fructose, 3 g/L NaNO3, 1.5 g/L KH2PO4, 1 mg/L thiamine, an incubation temperature of 25 °C, an initial medium pH 7.0, and an agitation speed of 150 rpm. As a result of reactor-scale studies, GA3, ABA, and IAA production values were increased 4.1, 3.4, and 2.3 times, respectively, compared to the initial screening values. The fact that PGR production was carried out for the first time with Pleurotus eryngii at a stirred tank reactor scale with this study adds an exciting dimension to the available data. In the light of these data, scale-up studies with larger scale reactors and the in vivo activity of PGRs produced by P. eryngii will be the aim of our future studies.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Dr. Abdunnasır Yıldız who donated the studied isolate and to the Eskişehir Osmangazi University Research Fund (201219A106) for financing this study.

Author contributions

MY designed the experiment with the help of NA. BD, ABE, and BGKK performed the study and ZY analyzed the data. MY, NA, and ZY finalized the manuscript before final submission.

Data availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

On behalf of all the authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Research involving human participants and/or animals

The authors declare that human participants or animals were not included in this study.

Informed consent

The authors declared that this research does not require informed consent since it is not a clinical trial.

References

- Akyüz M, Kırbağ S, Karatepe M, Güvenç M, Zengin F. Vitamin and fatty acid composition of P. eryngii var. eryngii. Bitlis Eren Univ J Sci Technol. 2011;1:16–20. doi: 10.17678/beuscitech.47155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alam N, Yoon KN, Lee JS, Cho HJ, Shim MJ, Lee TS. Dietary effect of Pleurotus eryngii on biochemical function and histology in hypercholesterolemic rats. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2011;18:403–409. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2011.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Başıaçık Karakoç Ş, Aksöz N. Bazı matrikslere tutuklanmiş Aspergillus niger'den gibberellik asit üretimi. Orlab on Line Mikrobiyol Derg. 2005;3:16. [Google Scholar]

- Bayburt C, Karaduman AB, Yenice Gürsu B, Tuncel M, Yamaç M. Decolourization and detoxification of textile dyes by Lentinus arcularius in immersion bioreactor scale. Int J Environ Sci Technol. 2020;17:945–958. doi: 10.1007/s13762-019-02519-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bose A, Shah D, Keharia H. Production of indole-3-acetic-acid (IAA) by the white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus under submerged condition of Jatropha seedcake. Mycology. 2013;4:103–111. doi: 10.1080/21501203.2013.823891. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlavilla JR, Manjón JL. The king oyster mushroom Pleurotus eryngii behaves as a necrotrophic pathogen of Eryngium campestre. Ital J Mycol. 2023;52:22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Cen YK, Li MH, Wang Q, Zhang JM, Yuan JC, Wang YS, Liu ZQ, Zheng Y. Evolutionary engineering of Fusarium fujikuroi for enhanced production of gibberellic acid. Process Biochem. 2023;125:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2022.12.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Curtis PJ, Cross BE. Gibberellic acid. A new metabolite from the culture filtrates of Gibberella fujikuroi. Chem Ind. 1954;35:1066. [Google Scholar]

- de Oliveira J, Rodrigues C, Vandenberghe LPS, Câmara MC, Libardi N, Soccol CR. Gibberellic acid production by different fermentation systems using citric pulp as substrate/support. BioMed Res Int. 2017;2017:5191046. doi: 10.1155/2017/5191046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doğan B, Yıldız Z, Aksöz N, Eninanç AB, Dağ İ, Yıldız A, Doğan HH, Yamaç M. Flask and reactor scale production of plant growth regulators by Inonotus hispidus: optimization, immobilization and kinetic parameters. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2023 doi: 10.1080/10826068.2023.2185636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois M, Gilles KA, Hamilton JK, Rebers PA, Smith F. Colorimetric method for determination of sugars and related substances. Anal Chem. 1956;28:350–356. doi: 10.1021/ac60111a017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Durán-Páramo E, Molina-Jiménez H, Brito-Arias MA, Martínez FR. Gibberellic acid production by free and immobilized cells in different culture systems. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2004;114:381–388. doi: 10.1385/ABAB:114:1-3:381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Sheikh MA, Rajaselvam J, Abdel-Salam EM, Vijayaraghavan P, Alatar AA, Biji GD. Paecilomyces sp. ZB is a cell factory for the production of gibberellic acid using a cheap substrate in solid state fermentation. Saudi J Biol Sci. 2020;27:2431–2438. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2020.06.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein E, Miles PG. Identification of indole-3-acetic acid in the basidiomycete Schizophyllum commune. Plant Physiol. 1967;42:911–914. doi: 10.1104/pp.42.7.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fushimi K, Anzai K, Tokuyama S, Kiriiwa Y, Matsumoto N, Sekiya A, Hashizume D, Nagasawa K, Hirai H, Kawagishi H. Agrocybynes A–E from the culture broth of Agrocybe praecox. Tetrahedron. 2012;68:1262–1265. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.11.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon SA, Fleck A, Bell J. Optimal conditions for the estimation of ammonium by the Berthelot reaction. Ann Clin Biochem. 1978;15:270–275. doi: 10.1177/000456327801500164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruen HE. Auxins and Fungi. Ann Rev Plant Physiol. 1959;10:405–440. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.10.060159.002201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamayun M, Khan S, Khan MA, Khan AL, Kang SM, Kim SK, Joo GJ, Lee IJ. Gibberellin production by pure cultures of a new strain of Aspergillus fumigatus. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:1785–1792. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-0078-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang HJ, Kim SW, Xu CP, Choi JW, Yun JW. Morphological and rheological properties of the three different species of basidiomycetes Phellinus in submerged cultures. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:1296–1305. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2004.02271.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isa NKM, Don MM. Investigation of the Gibberellic acid optimization with a statistical tool from Penicillium variable in batch reactor. Prep Biochem Biotechnol. 2014;44(6):572–585. doi: 10.1080/10826068.2013.844707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SA, Hamayun M, Kim HY, Yoon HJ, Lee IJ, Kim JG. Gibberellin production and plant growth promotion by a newly isolated strain of Gliomastix murorum. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2009;25:829–833. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-9981-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kobori H, Sekiya A, Suzuki T, Choi JH, Hirai H, Kawagishi H. Bioactive sesquiterpene aryl esters from the culture broth of Armillaria sp. J Nat Prod. 2015;78:163–167. doi: 10.1021/np500322t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lale GJ, Gadre RV. Production of Bikaverin by a Fusarium fujikuroi mutant in submerged cultures. AMB Express. 2016;6(1):34. doi: 10.1186/s13568-016-0205-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhou B, Kin RS, Jia L, Deng P, Fan YKM. Extraction and antioxidant activities of intracellular polysaccharide from Pleurotus sp. mycelium. Int J Biol Macromol. 2010;47:116–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2010.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machado CMM, Soccol CR, De Oliveira BH, Pandey A. Gibberellic acid production by solid-state fermentation in coffee husk. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2002;102–103:179–191. doi: 10.1385/ABAB:102-103:1-6:179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monrro M, Garcia JR. Gibberellic acid production from corn cob residues via fermentation with Aspergillus niger. J Chem. 2022;2022:1112941. [Google Scholar]

- Pham MT, Huang CM, Kirschner R. The plant growth-promoting potential of the mesophilic wood-rot mushroom Pleurotus pulmonarius. J Appl Microbiol. 2019;127:1157–1171. doi: 10.1111/jam.14375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plackett RL, Burman JP. The design of optimum multifactorial experiments. Biometrika. 1946;33:305–325. doi: 10.1093/biomet/33.4.305. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rangaswamy V. Improved production of gibberellic acid by Fusarium moniliforme. J Microbiol Res. 2012;2(3):51–55. doi: 10.5923/j.microbiology.20120203.02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seyis Bilkay I, Karakoç Ş, Aksöz N. Indole-3-acetic acid and gibberellic acid production in Aspergillus niger. Turk J Biol. 2010;34:313–318. [Google Scholar]

- Shenbhgaraman R, Jagadish LK, Premalatha K, Kaviyarasan V. Optimization of extracellular glucan production from Pleurotus eryngii and its impaction angiogenesis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2012;50:957–964. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2012.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla R, Chand S, Srivastava AK. Batch kinetics and modeling of gibberellic acid production by Gibberella fujikuro. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2005;36:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2004.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva EME, Dendooven L, Reynell JAU, Ramirez AIM, Gonzalez Alatorre G, Martinez MT. Morphological development and gibberellin production by different strains of Gibberella fujikuroi in shake flasks and bioreacto. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;15:753–755. doi: 10.1023/A:1008976000179. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva EME, Dendooven L, Magana IP, Parra RP, de la Torre M. Optimization of gibberellic acid production by immobilized Gibberella fujikuroi mycelium in fluidized bioreactors. J Biotechnol. 2000;76:147–155. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(99)00182-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stajić M, Vukojević J, Duletić-Laušević S. Biology of Pleurotus eryngii and role in biotechnological processes: a review. Crit Rev Biotechnol. 2009;29(1):55–66. doi: 10.1080/07388550802688821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swain MR, Ray RC. Optimization of cultural conditions and their statistical interperation for production of indole-3-acetic acid by Bacillus subtilis CM5 using cassava fibrous residue. J Sci Ind Res. 2008;67:622–628. [Google Scholar]

- Takayama T, Yoshida H, Araki K, Nakayama K. Microbial production of abscisic acid with Cercospora rosicola. Biotechnol Lett. 1983;5:55–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tiryaki D, Gülmez Ö. Determination of the effect of indole acetic acid (IAA) produced from edible mushrooms on plant growth and development. Anatol J Biol. 2021;2:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ünyayar S, Topcuoglu SF, Ünyayar A. A modified method for extraction and identification of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), gibberellic acid (GA3), abscisic acid (ABA) and zeatin produced by Phanerochaete chrysosporium ME 446 Bulgar. J Plant Physiol. 1996;22:105–110. [Google Scholar]

- Ünyayar S, Ünyayar A, Ünal E. Production of auxin and abscisic acid by Phanerochaete chrysosporium ME446 immobilized on polyurethane foam. Turk J Biol. 2000;24:769–774. [Google Scholar]

- Valentino MJG, Galvez CT. Auxin-like and gibberellic acid-like activity of Pleurotus sajor-caju (Fr.) Singer and Volvariella volvacea Fr. on Tomato (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) seedlings. Adv Environ Biol. 2015;9(23):361–367. [Google Scholar]

- Wang B, Yin K, Wu C, Wang L, Yin L, Lin H. Medium optimization for GA4 production by Gibberella fujikuroi using response surface methodology. Fermentation. 2022;8:230. doi: 10.3390/fermentation8050230. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wei W, Hui WY, Lie LJ, Fei YY. Enhancement of gibberellin acid production through pH regulation in batch fermentation of Gibberella fujikuroi. Mycosystema. 2019;38(7):1185–1190. [Google Scholar]

- Werle LB, Abaide ER, Felin TH, Kuhn KR, Tres MV, Zabot GL, Kuhn RC, Jahn SL, Mazutti MA. Gibberellic acid production from Gibberella fujikuroi using agro-industrial residues. Biocat Agric Biotechnol. 2020;25:101608. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2020.101608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Kobori H, Kawaide M, Suzuki T, Choi JH, Yasuda N, Noguchi K, Matsumoto T, Hirai H, Kawagishi H. Isolation of bioactive steroids from the Stropharia rugosoannulata mushroom and absolute configuration of Strophasterol B. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2013;77:1779–1781. doi: 10.1271/bbb.130216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Uchida K, Ridwan AY, Kondo M, Choi JH, Hirai H, Kawagishi H. Erinachromanes A and B and Erinaphenol A from the culture broth of Hericium erinaceus. J Agric Food Chem. 2019;67:3134–3139. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b06050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaoita Y, Yoshihara Y, Kakuda R, Machida K, Kikuchi M. New sterols from two edible mushrooms Pleurotus eryngii and Panellus serotinus. Chem Pharmac Bull. 2002;50:551–553. doi: 10.1248/cpb.50.551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yürekli F, Yesilada Ö, Yürekli M, Topcuoglu SF. Plant growth hormone production from olive oil mill and alcohol factory wastewaters by white rot fungi. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 1999;15:503–505. doi: 10.1023/A:1008952732015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yürekli F, Gecgil H, Topcuoglu SF. The synthesis of indole-3-acetic acid by the industrially important white-rot fungus Lentinus sajor-caju under different culture conditions. Mycol Res. 2003;107:305–309. doi: 10.1017/S0953756203007391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zervakis GI, Venturella G, Papadopoulou K. Genetic polymorphism and taxonomic infrastructure of the Pleurotus eryngii species-complex as determined by RAPD analysis, isozyme profiles and ecomorphological characters. Microbiology. 2001;147(11):3183–3194. doi: 10.1099/00221287-147-11-3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Lei Z, Liu Z-Q, Zheng Y-G. Improvement of gibberellin production by a newly isolated Fusarium fujikuroi mutant. J Appl Microbiol. 2020;129(6):1620–1632. doi: 10.1111/jam.14746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article.