Abstract

Bacillus subtilis SPB1 derived biosurfactants (BioS) proved its bio-control activity against Agrobacterium tumefaciens using tomato plant. Almost 83% of disease symptoms triggered by Agrobacterium tumefaciens were reduced. Aiming potential application, we studied lipopeptide cost-effective production in both fermentations systems, namely the submerged fermentation (SmF) and the solid-state fermentation (SSF) as well as the use of Aleppo pine waste and confectionery effluent as cheap substrates. Optimization studies using Box–Behnken (BB) design followed by the analysis with response surface methodology were applied. When using an effluent/sea water ratio of 1, Aleppo pine waste of 14.08 g/L and an inoculum size of 0.2, a best production yield of 17.16 ± 0.91 mg/g was obtained for the SmF. While for the SSF, the best production yield of 27.59 ± 1.63 mg/g was achieved when the value of Aleppo pine waste, moisture, and inoculum size were, respectively, equal to 25 g, 75%, and 0.2. Hence, this work demonstrated the superiority of SSF over SmF.

Keywords: Biocontrol, Biosurfactants , Aleppo pine waste, Fermentation, Response surface methodology

Introduction

Agrobacterium tumefaciens is among the pathogenic microorganisms present in the environment. It is the causal agent of plants diseases such as crown gall causing great damage to crop and leading to considerable losses in productivity and low harvest property (Escobar and Dandekar, 2003; Hammami et al., 2009). Thus, in order to inhibit the plant pathogenic bacteria growth, protect against soil-borne diseases, hamper plant mortality, reduce plant losses, improve plant emergence and therefore improve overall crop production, chemical control methods have been widely used in conventional agriculture (Hammami et al., 2011). They require the use of synthetic pesticides that persist into soil and take a long time to be completely eliminated (Damalas and Eleftherohorinos, 2011). Additionally, they present higher toxicity to young plants and pose severe environmental and professional damages to environment and the workers (Yangui et al., 2013). Also, the application of pesticides and fungicides can cause irreparable damage to the metallic structure of greenhouses (Hammami et al., 2011). Moreover, numerous plant pathogenic bacteria acquired resistance to commercial pesticides (Franco et al., 2007). Therefore, an urgent need on effective alternative methods for disease control was developed. As described by Hammami et al. (2011), three main criteria influence the effectiveness of a control agent namely its specificity against potential pathogens, its degradation after use, and its low cost for wide-scale application.

Recently, numerous natural compounds have been extensively investigated as alternative classes for the control of plant pathogens such as the use of essential oils (Bajpai et al., 2011; Gakuubi et al., 2016; Raveau et al., 2020) and microbial derived compounds (Al-Reza et al., 2010; Hammami et al., 2009, 2011). In fact, it is well documented that surface-active compounds produced by B. subtilis, are amongst the most popular and potent metabolites in the fight and treatment of microbial disease infection (Cao et al., 2012; Li et al., 2012; Mnif et al., 2015; Mnif et al., 2016).

Most of the currently used surfactants are derived from petroleum feedstock (Almeida et al., 2017; Rodríguez et al., 2020). They are recognized as an interesting class of chemical compounds suitable for the use in numerous fields including the food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic and petroleum industries (Almeida et al., 2017; Pereira et al., 2013; Rodríguez et al., 2020). However, they pose significant environmental risks because they form dangerous compounds from incomplete biodegradation in water or soil (Almeida et al., 2017; Rodríguez et al., 2020). Comparing to their chemical counterpart, biosurfactants (BioS) are more environment friendly as they possess a low toxicity level and a higher biodegradability (Singh et al., 2007; Van Hamme et al., 2006). Therefore, considering the restrictive laws and the increase of public concern about the environmental issues, more interest and attention during the recent years have been paid to produce natural surfactants or BioS (Pereira et al., 2013). These biomolecules are derived from diverse microbial strains specifically bacteria, filamentous fungi and yeasts (Almeida et al., 2017; Carolin et al., 2021). Owing their chemical composition, they are classified onto glycolipids, lipopolysaccharides, oligosaccharides and lipopeptides (Carolin et al., 2021). The swift progress of biotechnology has allowed the development and the use of these bio-compounds thanks to their incredibly functional qualities when compared with the traditional chemical surfactants. In fact, these bio-products are more compatible to the environment as they possess low toxicity level, high biodegradability along with high tolerance to extreme conditions of pH, temperature and salinity (Banat et al., 2021; Chen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2012). Also, they are well characterized with a low Critical Micelle Concentrations (CMCs) correlated to higher decrease of the surface tension (Almeida et al., 2017). However, the expansion of BioS has been hampered in industrial applications due to some drawbacks; first the low yields and second, the high cost in the production process (Carolin et al., 2021; Pereira et al., 2013; Zouari et al., 2015a). Therefore, several processes have been employed in order to improve the yield and the cost of production. A root cause analysis has been erected and opportunities for enhancement, such as media optimization (Chen et al., 2020), strain improvement by mutagenesis or recombinant strains (Bouassida et al., 2018; Chen et al., 2020) and bioreactor operation and design were established (Chen et al., 2020; Mukherjee et al., 2006). Moreover, as the cheap raw materials represent 50% of the final product charge, their employment makes the production process more cost-effective (Chen et al., 2020). Additionally, this strategy permits to reduce the cost of wastes discharge and treatment (Almeida et al., 2017). In this regard, various studies reporting the use of complex agro-industrial wastes for lipopeptides production as substitutes of synthetic medium ingredients have been published in Submerged Fermentation (SmF) (Barros et al., 2008; Cho et al., 2009; Joshi et al., 2008; Zouari et al., 2015a) as well as in Solid State Fermentation (SSF) (Das and Mukherjee, 2007; Kim et al., 2009; Kuo, 2006; Mnif et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2008; Zouari et al., 2015b). They permit a high cost reduction along with valorization of agro-wastes.

According to our previous studies, we demonstrated the ability of B. subtilis SPB1 to produce lipopeptide compounds consisting of Surfactin; Iturin and Fengycin isoforms (Mnif et al., 2016). Their presence in the culture filtrate of SPB1 was confirmed by mass spectroscopic analysis. The lipopeptide mixture was characterized by a broad spectrum of biological activities. It showed antibacterial activity towards several microorganisms (Ghribi et al., 2012) and antifungal activity towards phytopathogenic fungi (Mnif et al., 2015; Mnif et al., 2016). Moreover, Zouari et al. (2015c) proved the anti-diabetic and anti-lipidemic properties of SPB1 BioS in alloxan-induced diabetic rats.

Owing to these great interest and wide spectrum of applications, we aim firstly to study the effect of the SPB1 B. subtilis strain and its lipopeptides in controlling the phytopathogenic bacteria Agrobacterium tumefaciens. Secondly, our purpose is to do a comparison study of B. subtilis SPB1 BioS production efficiency in both SmF and SSF systems using barks of dried seeds of Aleppo pine (a pastry shop waste product) and confectionery effluent as cheap substrates.

Materials and methods

Microorganisms

Bacillus subtilis SPB1 (HQ392822) strain, previously isolated from a Tunisian soil contaminated with hydrocarbons was used in the present work (Ghribi et al., 2012). It was very effective in producing lipopeptide BioS with high emulsifying and hemolytic properties (Ghribi et al., 2012). As presented by Mnif et al. (2016), different Surfactin, Iturin and Fengycin isoforms with molecular weights of 1007, 1021 and 1035 Da; 1028, 1042 and 1056 Da and 1432 and 1446 Da were identified respectively. Two new clusters of lipopeptide isoforms having molecular weights of 1410 and 1424 Da and 973 and 987 Da were also identified. Acid precipitation and purification followed by mass spectroscopic analysis were applied in this study (Mnif et al., 2016).

The strain A. tumefaciens C58 was used in this study as a plant pathogenic bacterium (Hammami et al., 2009). K84 and K1026 were used as commercial antagonist strains of pathogenic bacteria. All these strains were graciously afforded by the Olive Institute of Sfax-Tunisia.

Evaluation of antibacterial activity of the BioS produced by B. subtilis SPB1 towards A. tumefaciens

In vitro antibacterial activity

The antibacterial potency against A. tumefaciens was studied by the agar well diffusion method following the protocol described by Trigui et al. (2013) with little modification. To prepare a cell suspension, we adjusted the turbidity of the bacterial culture to 107 colony forming units/mL (CFU/mL). 1 mL of the prepared suspension served to inoculate the surface of agar plates (Trigui et al., 2013). Thereafter, wells were punctured onto the surface of the inoculated agar medium. They were filled with 100 µL of cell suspensions (107 CFU/mL) of SPB1, K84 and K1026. The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h and the antibacterial activity was evaluated by measuring the clear zone of growth inhibition around the well for each bacterial strain.

In vivo antibacterial activity

For in vivo assays, we used 10 one-month-old tomato plants (Solanum lycopersicum) for each treatment. Plants were grown in 15-cm-diameter pots containing a sterilized mix of soil, sand and peat (2:1:1 by volume). They were watered daily by drip-irrigation. The assays were conducted in a greenhouse. To maintain optimum nutritional conditions, we added weekly into the pots a mineral solution. During the experiment, an automatic cooling was applied to maintain the temperature and the relative humidity at 25 °C and between 70 and 80%, respectively (Trigui et al., 2013).

Preventive and curative treatments of Agrobacterium tumefaciens infested tomato stem

With a sterile scalpel, we made 1 cm long longitudinal wounds at the internodes of plants. For each plant, 10 mL of C58 cell suspension (108 CFU/mL) was poured in three treated wounds. SPB1 culture (108 CFU/mL) and SPB1 BioS (40 g/L) were used to suppress the crown gall caused by A. tumefaciens. In order to prevent drying, we covered wounds with parafilm (Trigui et al., 2013).

Preventive and curative treatments were applied as proposed by Mnif et al. (2015). For preventive treatment, plants were submerged in SPB1 culture or their derived BioS alone, in the day before the bacterial infection. When plants were irrigated by the SPB1culture or the BioS solution one day after the infection, it corresponds to the curative treatment. Safe and infected plants served as positive and negative controls respectively. In order to maintain their survival and stability, regular irrigation with water was applied for all plants.

In order to verify the pathogenicity of A. tumefaciens strain C58, we followed the tested induced galls on tomato 20 days after stem inoculation as described by Zoina and Raio (1999). Obtained results were determined by the measure of the tumor weights and the index of biocontrol potency according to the formula published by Penyalver and Lopez (1999):

Biosurfactant production under different fermentation systems

Preparation of substrate

Barks of dried seeds of Aleppo pine were collected from Tunisian pastry. They were dried at ambient temperature for nearly 72 h. After that, seeds were ground in a coffee grinder (Moulinex Type 53,402, Paris, France), charecterized and then re-dried overnight at 105 °C to be completely desiccated.

Substrates analysis

The chemical composition of Aleppo pine waste is 8% sugar, 4.7% lipid, 1.59% protein and 16% ash. The dry matter is about 95.25% corresponding to a water content of 4.75%. The TRIKI effluent, containing only sugar (4%), was purchased from a local factory (Moulin TRIKI Group, Sfax, Tunisia). The phenol–sulphuric assay served to estimate soluble carbohydrates after extraction (Smibert et al., 1994). Kjeldahl method was used for evaluating the protein content (Pearson, 1976). Soxhlet method using hexane as a solvent served to quantify lipid content determined after that by the gravimetric quantification (Sidney, 1984). For the dry matter and ash content, they were determined by oven drying at 105 °C until a constant weight and combustion of the dried sample in a muffled furnace at 550 °C for 6 h, respectively (Bryant and Mc Clements, 2000).

Preparation of inoculum

To prepare the inoculum, we dispensed a single colony of the wild-type strain B. subtilis SPB1 into LB medium (pH 7). The whole was incubated overnight at 150 rpm and 37 °C until an optical density (OD 600 nm) of 3.5 was reached.

SPB1 BioS production under submerged fermentation (SmF)

The SmF procedure was fulfilled as defined by Ghribi and Ellouze-Chaabouni (2011). 50 mL of cultures were transferred into 250 mL erlenmeyer flasks. The pH of the medium was adjusted to 7 and cultures were incubated for 48 h at 37 °C under continuous shaking at 150 rpm. Production medium was composed of barks of dried seeds of Aleppo pine, TRIKI effluent and sea water. The proportions of the different components are given in Table 1. As it is known to be an ideal source of mineral salts, sea water was utilized to complement salt need for production of these BioS (Ghribi et al., 2007).

Table 1.

Bacillus subtilis SPB1 derived BioS production in SmF: Box Behnken experimental design and obtained response

| Run order | X1 Ratio (TRIKI effluent/sea water) |

X2 Aleppo pine waste (g/L) |

X3 Inoculum size (OD 600) |

BioS production (mg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental value (Y p/s) | Predicted value (Y p/s) | ||||

| 1 | − 1 (0.5) | − 1 (15) | 0 (0.2) | 16.00 | 15.05 |

| 2 | 1 (1.5) | − 1 (15) | 0 (0.2) | 14.66 | 13.81 |

| 3 | 1 (0.5) | 1 (45) | 0 (0.2) | 4.000 | 4.845 |

| 4 | 1 (1.5) | 1 (45) | 0 (0.2) | 4.440 | 5.385 |

| 5 | 1 (0.5) | 0 (30) | − 1 (0.1) | 7.000 | 7.953 |

| 6 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (30) | − 1 (0.1) | 8.500 | 9.353 |

| 7 | − 1 (0.5) | 0 (30) | 1 (0.3) | 10.33 | 9.478 |

| 8 | 1 (1.5) | 0 (30) | 1 (0.3) | 8.330 | 7.378 |

| 9 | 0 (1) | − 1 (15) | − 1 (0.1) | 16.00 | 15.99 |

| 10 | 0 (1) | 45 | − 1 (0.1) | 11.83 | 10.03 |

| 11 | 0 (1) | − 1 (15) | 1 (0.3) | 17.33 | 19.13 |

| 12 | 0 (1) | 1 (45) | 1 (0.3) | 6.440 | 6.448 |

| 13 | 0 (1) | 0 (30) | 0 (0.2) | 10.33 | 9.724 |

| 14 | 0 (1) | 0 (30) | 0 (0.2) | 8.960 | 9.724 |

| 15 | 0 (1) | 0 (30) | 0 (0.2) | 9.660 | 9.724 |

| 16 | 0 (1) | 0 (30) | 0 (0.2) | 9.670 | 9.724 |

| 17 | 0 (1) | 0 (30) | 0 (0.2) | 10.00 | 9.724 |

SPB1 BioS production under solid state fermentation (SSF)

The inoculum was used in order to inoculate the production media composed only of waste of Aleppo pine seeds and TRIKI confectionery effluent at the proportions shown in Table 2. The third parameter described in Table 2 corresponds to the final optical density at which we start the fermentation (OD 600). It was quantified according to the volume of the liquid (TRIKI effluent) added in each experiment. The flasks, containing the appropriate media, were statically kept in an incubator at 37 °C for 48 h. The fermented material was used for lipopeptide extraction and quantification (Ghribi et al., 2012).

Table 2.

B. subtilis SPB1 derived BioS production in SSF: Box Behnken experimental design and obtained response

| Run order | X1 Aleppo pine waste (g) |

X2 Moisture (%) |

X3 Inoculum size (OD 600) |

BioS production (mg/g) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experimental Value | Predicted value | ||||

| 1 | − 1 (15) | − 1 (60) | 0 (0.2) | 18.94 | 19.23 |

| 2 | 1 (45) | − 1 (60) | 0 (0.2) | 23.99 | 20.58 |

| 3 | − 1 (15) | 1 (90) | 0 (0.2) | 16.78 | 20.18 |

| 4 | 1 (45) | 1 (90) | 0 (0.2) | 18.58 | 18.29 |

| 5 | − 1 (15) | 0 (75) | − 1 (0.1) | 21.88 | 20.15 |

| 6 | 1 (45) | 0 (75) | − 1 (0.1) | 19.75 | 21.71 |

| 7 | − 1 (15) | 0 (75) | 1 (0.3) | 24.85 | 22.89 |

| 8 | 1 (45) | 0 (75) | 1 (0.3) | 19.06 | 20.79 |

| 9 | 0 (30) | − 1 (60) | − 1 (0.1) | 18.76 | 20.20 |

| 10 | 0 (30) | 1 (90) | − 1 (0.1) | 20.84 | 19.16 |

| 11 | 0 (30) | − 1 (60) | 1 (0.3) | 19.06 | 20.74 |

| 12 | 0 (30) | 1 (90) | 1 (0.3) | 21.88 | 20.44 |

| 13 | 0 (30) | 0 (75) | 0 (0.2) | 29.90 | 27.95 |

| 14 | 0 (30) | 0 (75) | 0 (0.2) | 26.14 | 27.95 |

| 15 | 0 (30) | 0 (75) | 0 (0.2) | 27.98 | 27.95 |

| 16 | 0 (30) | 0 (75) | 0 (0.2) | 27.92 | 27.95 |

| 17 | 0 (30) | 0 (75) | 0 (0.2) | 27.82 | 27.95 |

Determination of the production yield

For the SmF, the cells-free supernatant obtained by centrifugation of the fermented medium at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C served for BioS quantification.

Regarding the SSF, the protocol described by Zouari et al. (2015b) was followed, with slight modifications. The most of the lipopeptide BioS was extracted from the fermented medium with isopropanol (at a ratio of 1:3 (w:v). The whole mixture was vortexed at high speed, shaken for one hour at 200 rpm at ambient temperature and centrifuged for 10 min at 10,000 rpm to separate the undesired insoluble matter from the resultant supernatant. The production yield, either by SmF or SSF, was expressed as the amount of the crude BioS obtained per g of dry substrate. Biosurfactant was quantified by measuring the emulsifying activity (Ghribi and Ellouze-Chaabouni, 2011) of the obtained supernatant. A correlation factor was used to convert the measured DO into the amount of BioS (mg/L) (an optical density of 0,1 correspond to almost 3,33 × 102 mg/L). Un-inoculated medium was realized as negative control. Obtained results correspond to the means values of three different measurements.

Lipopeptide production and extraction for bio-control tests

The B. subtilis SPB1 biosurfactant production was performed as reported by Ghribi and Ellouze-Chaabouni (2011), with slight modifications. The lipopeptide was extracted according to the protocol described by Mnif et al. (2012, 2021a, 2021b, 2021c). The protocol consists of three cycles of acid precipitation-neutralization of the cell free supernatants. We begin by an acidification to pH 2.0 by adding 6 N HCl followed by an incubation overnight at 4 °C to precipitate the most BioS products. After that, centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and 4 °C during 10 min served to collect the obtained pellet that would be washed twice with acid distilled water (pH 2) to remove any impurities. To dissolve the most lipopeptide compounds, we adjusted the pH to 8.0 by 1 N NaOH after being dissolved in distilled water. The dissolved extract was, finally, lyophilized (Mnif et al., 2021a; Mnif et al., 2021b). This serves as crude lipopeptide preparation to perform the in-vivo antibacterial assays.

Application of statistical procedure to optimize SPB1 biosurfactant

Box–Behnken experimental design study

A three independent variables Box–Behnken (BB) design was adopted (Box and Behnken, 1960) in each fermentation (SmF and SSF) systems. The chosen variables for the SmF are as follows: the ratio of the liquid substrates (X1), where X1 = TRIKI effluent/sea water, Aleppo pine waste (X2, g/L) and the inoculum size (X3, OD600). Table 1 described the range and the levels of the factors that varies according to the experimental design. Three coded values were assigned for each variable corresponding to a minimal value (− 1), centered value (0) and maximal value (+ 1). Each coded value corresponds to a real value as presented in Tables 1 and 2. The real values are presented between parentheses. Concerning the SSF, the three test factors are Aleppo pine waste (X1, g), moisture (X2, %) and inoculum size (X3, OD600). Moisture was calculated as the quantity of water in mL per g of dry substrate. These variables had been used in order to prepare 17 experiments given in Table 2.

Analysis of data, model elaboration and response surface methodology

To optimize the critical factors and to highlight the potential interaction between them, a second-order polynomial function represented below was erected:

where, Y is the predicted response; b0 a constant; bi the linear coefficients; bi-i the squared coefficients; and bi-j the interaction coefficients. The terms Xi, XiXj and Xi2 represent the coded levels of independent variables, interaction and quadratic terms, respectively.

In order to check the errors and the significance of each parameter, we performed ANOVA (Analysis Of Variance) test. This was carried out by using Fisher’s statistical test (Francis et al., 2003). This analysis method quantifies the ability of the factors to describe the variation in the data about its mean (Sen and Swaminathan, 1997). In order to evaluate the statistical significance of the model, regression analysis based on the F test was deployed (Francis et al., 2003). The influence of each controlled factor on the tested model was indicated by the F-value. The coefficient of determination R2 served to evaluate the quality of the fit of the polynomial model equation (Ferreira et al., 2007).

In this study, in order to solve the regression equation and to analyze the response surface contour plots, we used the statistical software package (Nemrod-W-2007, by LPRAI Marseilles, France) (Mathieu and Phan-Tan-Lu, 2000). The system behavior was indicated by the two-dimensional graphical representation. They were used to reveal the individual and cumulative effects of the variables as well as the probable connection linking them (Ghribi et al., 2012).

Results and discussion

Evaluation of potential antibacterial activity of the BioS derived from B. subtilis SPB1 against Agrobacterium tumefaciens

In vitro antibacterial activity of B. subtilis SPB1

The antagonistic activity of SPB1, K84 and K1026 against A. tumefacins was established. The obtained results indicated that SPB1 strain showed the higher inhibition zone diameter of 20 mm compared to the other strains (11 mm). The antimicrobial action of B. subtilis has been well proven by many researches (Foldes et al., 2000; McKeen et al., 1986; Phae et al., 1990; Todorova, 2010). Generally, Bacillus species are considered good sources of molecules with antimicrobial activity. They are well-known to produce numerous bioactive substances such as bacitracin, bacteriocins, and antimicrobial lipopeptides (Xu et al., 2020). In this aim, Ghribi et al. (2012) showed the broad spectrum of antibacterial activity of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 BioS. Moreover, as proven by Mnif et al. (2015), SPB1 Bios demonstrated antifungal activity against the phyto-pathogenic fungi, Fusarium solani, with moderate to higher efficiency.

In vivo antibacterial activity of B. subtilis SPB1 and its biosurfactant

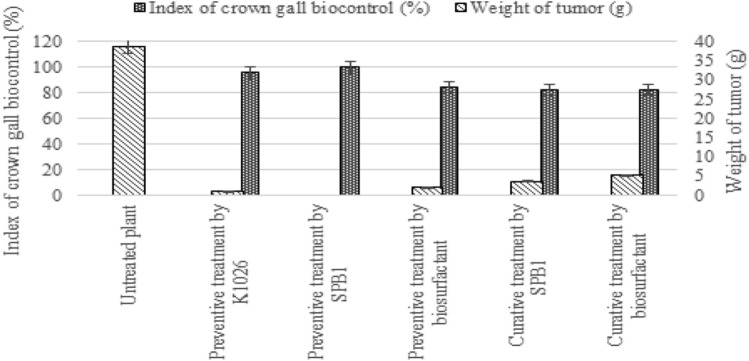

Presenting interesting in vitro antibacterial potency, we evaluated the potential in vivo biocontrol activity of SPB1 against tomato infection occasioned by A. tumefaciens C58. Obtained results proved that BioS molecules can be useful for effective biocontrol of tomato plants. In fact, the inoculated and treated plants with SPB1 strain and its lipopeptide were comparable to the healthy control and did not develop any symptoms of infection. However, burning symptoms appeared on the leaf of untreated tomato plants after 1 week of inoculation. Additionally, 20 days later; necrotic sign on the collar and roots of inoculated plants were developed. Both methods were significantly effective in controlling A. tumefaciens diseases. The protective effect using a BioS-producing strain to protect tomato disease (82–100%) was higher than the one obtained when the BioS treatment (82–84%) was used (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Effect of the type of the treatment on the index of crown gall biocontrol and the weight of tumor

Figure 1 indicated, also, that the preventive method was better than the curative method either when using the SPB1 strain or the BioS alone. Indeed, the weight of the tumors was between 0 and 2.16 g when applying the preventive treatment. However, a slight increase in tumor weights was observed when using curative treatment (3.6 and 5.2 g) (Fig. 1). Moreover, compared to the commercial biocontrol agent K1026 that is used as a positive control in this experiment (1.09 g of tumor weight), preventive treatment by B. subtilis (0 g of tumor weight) was more effective.

To conclude, obtained results proved the significant efficiency of the treatments with the lipopeptide and its producing strain in reducing the disease incidence and severity caused by A. tumefaciens. In addition, the preventive treatment was more powerful to inhibit symptom development than the curative one. Indeed, both methods were significantly efficient in controlling A. tumefaciens diseases.

Regarding previous studies, several bacteria were demonstrated for the effective biocontrol of the crown gall disease brought on by pathogenic Agrobacterium. A. rhizogenes K84, its recombinant strain K1026, and A. vitis E26, for instance, were described as biocontrol agents reducing crown gall disease in some plants. Biocontrol against pathogenic Agrobacterium was described the first time with K84 strain. However, the biocontrol of crown gall disease can be hampered because the K84 strain can spread the pAgK84 plasmid, which regulates agrocin 84 syntheses and resistance, to crown gall pathogens (Chen et al., 2021). According to Malviya et al. (2020), numerous Bacillus strains have been employed as biocontrol agents to promote plant development and to resist against stress. In fact, Nihorimbere et al. (2010) proved the beneficial effects of B. subtilis on field-grown tomato towards local Fusarium infestation. The strain promotes plant growth and reduces the disease severity to about 65–70%. Moreover, the capacity of B. velezensis MBY2 to limit C58-induced gall growth in vivo on tomato and almond plant stems was proven by Ben Gharsa et al. (2021). As a matter of fact, regarding the negative control, the generated tumor mass was 0.68 g and 0.531 g for almond and tomato respectively. Whereas, we note a drastic decrease after being treated with A. radiobacter K84 of about 0.153 g and 0.095 g as well as B. velezensis MBY2 of about 0.089 g and 0.05 g, for almond and tomato, respectively. Although the Bacillus strain greatly decreased gall weight, the difference between it and the commercial biocontrol agent K84 used as a positive control was not statistically significant (Ben Gharsa et al., 2021).

Most Bacillus strains are able to produce the pathogen-suppressing compounds polyketides, cyclic lipopeptides, and dipeptide bacilysin (Malviya et al. 2020). Having the ability to produce lipopeptides especially bacillomycin, surfactin and fengycin isoforms, several Bacillus isolates demonstrated great inhibitory ability of the growth of eight phytopathogenic bacterial strains namely Erwinia amylovora, Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae, Xanthomonas arboricola pv. fragariae, X. axonopodis pv. vesicatoria, Rhizobium radiobacter (syn. Agrobacterium tumefaciens), Ralstonia solanacearum, Clavibactermichi ganensis sbsp. michiganensis and Pectobacterium carotovorumsbsp. carotovorum (Mora et al. 2015). Agrobacterium strains, the causal agent of the crown gall disease in tomato and carrot plants, have been shown to be inhibited by the lipopeptides generated by B. methylotrophicus and B. amyloliquefaciens, respectively (Ben Abdallah et al., 2015; Frikha-Gargouri et al., 2017).

As known, for the in vivo biocontrol agent against microbial infestation, B. subtilis species and their metabolites were largely applied (des Grades et al., 2012; Leelasuphakul et al., 2008; Nihorimbere et al., 2010). Correspondingly, to suppress plant tomato disease development, lipopeptides derived from Bacillus species are the most popular antimicrobial compounds used (Ongena and Jacques, 2008). In fact, Leclère et al. (2005) described the efficiency of a B. subtilis derived mycosubtilin to reduce Pythium infection of tomato seedlings. A significant increase in the germination rate of seeds with a greater fresh weight of emerging seedlings marked the disappearance of the disease symptoms. The Iturin A from B. subtilis RB14-C was efficient to combat R. solani and Phomopsis root rot causing the damping off of tomato seedlings (Kita et al., 2005). In addition, Cao et al. (2012), Hu et al. (2007) and Rebib et al. (2012) reported the inhibitory in vivo effect of Fengycin against, respectively, F. moniliforme spread causing maize infection and Fusarium wilt and foot rot of cucumber and wheat respectively.

Regarding literature studies, diverse biological control systems were applied to treat tomato infestation by phytopathogenic fungus such as Trichoderma viride (Ebtsam et al., 2009), T. harzianum and Paenibacillus lentimorbus (Montealegre et al., 2005). Therefore, the possibility of controlling tomato bacterial diseases with SPB1 strain and its produced BioS as biocontrol agent against A. tumefaciens tomato infection appears of particular interest.

In this study, we proved effectiveness of the preventive SPB1 lipopeptide treatment compared to the curative one in avoiding and suppressing the symptoms. Results are in contrast to those obtained by Des Grades et al. (2012) demonstrating the similarity of the disease severity reduction occasioned by Phytophthora infestans. However, results are similar to those presented by Mnif et al. (2015). The degree of disease reduction varied according to the treatment method. In fact, when using SPB1 BioS as antifungal agent to treat tomato plants infection against F. solani, we noted an inhibition of disease development to about 100% and 75% when applying the curative and preventive method respectively (Mnif et al., 2015). Similarly, the same facts were hypothesized by Soylu et al. (2010).

In addition, we demonstrate the effective use of lipopeptide BioS alone in reducing the disease incidence and severity caused by A. tumefaciens and the preventive treatment was more powerful to inhibit symptom development than the curative treatment. A similar study published by Triki et al. (2012) reported the decrease of rot extension of about 62% when applying preventive treatment by B. subtilis filtrate. In the same work, a decrease of about 37% of disease severity by curative treatment was noticed.

Lipopeptide BioS production on Aleppo pine waste flour

Given its effectiveness against A. tumefaciens diseases, we tried, on one hand, to minimize the cost production of the SPB1 BioS by using an economic substrat called Aleppo pine waste flour and, on the other hand, to examine SmF and SSF different production yields. The use of statistical models has enhanced the current biotechnology research (Ghribi et al., 2011). This procedure was considered as an important tool that could be used, on the one hand, to improve the production yield by optimizing the culture media compounds and conditions. On the other hand, a few experimental tests can be used to identify the ideal environmental conditions (Mnif et al., 2013). This technique worked well to improve BioS production by B. subtilis (Ghribi et al., 2012).

Analysis of data and model generation

To achieve the economic production of SPB1 BioS, a BB design was applied to figure out the optimum amount of Aleppo pine waste, inoculum size, ratio (TRIKI effluent/ sea water) and humidity in each fermentation system allowing a higher BioS production by B. subtilis SPB1. Tables 1 and 2 summarized the BB design as well as the experimental and predicted values of the BioS yields obtained for both SmF and SSF, respectively. As it is shown, the BioS production yield varied significantly from 4.84 mg/g (run 3) to 19.13 mg/g (run 11) in SmF and from 18.29 mg/g (run 4) to 27.95 mg/g (run 13) in SSF. The values of the three independent variables in the medium of each fermentation system had a significant impact on this variation (Ghribi et al., 2012).

The second-order polynomial equations Y1 and Y2, given below, were derived from the statistical analysis to represent BioS production, respectively, in SmF and SSF function as the tested different independent variables.

where Y1 and Y2 are the predicted BioS production yields. The coded values of “TRIKI effluent/sea water” ratio, aleppo pine waste and inoculum size in SmF as well as Aleppo pine waste, moisture and inoculum size in SSF are designated as X1, X2 and X3, accordingly.

For the purpose of detecting the meaningful differences, ANOVA test served to analyze the obtained finding. The F values were estimated to be 99.3878 in SmF and 13.7073 in SSF (Table 3). Thus, SmF turned out to be more adequate for the F values model as there was only a 0.6% chance of ‘‘F-value Model” taking place due to noise. In both fermentations, a significant interaction between variables was detected. The coefficient R2 was calculated to be 0.943 and 0.802 for BioS production in SmF and SSF, respectively. Thus, just 5.7% and 19.8%, respectively, of the total variances for SmF and SSF could not be explained by the model. Because the R2 value was close to 1 in both fermentation systems, we note a good correlation between experimental and predicted values (Ghribi et al., 2012). This indicated that the model adequately described the process.

Table 3.

ANOVA analysis for Box Behnken design experiments regarding SmF (A) and SSF (B)

| (A) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F-value | Significance |

| Regression | 231.2527 | 9 | 25.6947 | 99.3878 | Significant |

| Residual | 13.97840 | 7 | 1.99690 | ||

| Lack of fit | 12.94430 | 3 | 4.31480 | 16.6896 | Significant |

| Pure error | 1.034100 | 4 | 0.25850 | ||

| Total | 245.2310 | 16 | |||

| (B) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Sum of squares | df | Mean square | F-value | Significance |

| Regression | 218.8908 | 9 | 24.3212 | 13.7073 | Significant |

| Residual | 53.91450 | 7 | 7.70210 | ||

| Lack of fit | 46.81720 | 3 | 15.6057 | Significant | |

| Pure error | 7.097300 | 4 | 1.77430 | 8.7953 | |

| Total | 272.8052 | 16 | |||

Analysis of the 3D response surface plots

Aiming to comprehend and describe the impact of the investigated variables within the experimental space, we generate the response surface and contour plots. Each plot depicted the interaction between the two variables whereas maintaining the third variable at a constant level (Ghribi et al., 2011). Therefore, for SmF, we initially established the inoculum size at its central level OD600 = 0.2 (Fig. 2A). The response was shown to be a function of the level of Aleppo pine wastes in combination with the liquid substrate ratio. The best values for the two last variables were estimated to 0.99 and 14.08 g/L, respectively. It was clear that increasing the Aleppo pine waste value, caused a considerable drop in the yield of BioS from 16 to 8.8 mg/g. Likewise, when fixing the liquid substrates ratio at its optimal value (1), we obtain the best lipopeptide production of about 17.18 (± 0.91) mg/g when using an inoculum size of 0.2 and an Aleppo pine waste of 14.08 g/L (Fig. 2B). This figure showed that, at X2 lower than its middle level, iso-responses were near parallel to the inoculum size axis. This implied that neither an increase nor a decrease in the inoculum size can have a substantial impact on production yield. In SmF system, more strongly developed from the 1940s onwards (Kriaa and Kammoun, 2016), the dissolved nutrients were present in a liquid media in which microorganisms were suspended. It was demonstrated that SmF has several benefits in terms of controlling the process (Colla et al., 2010; Das and Mukherjee, 2007), high uniformity of the culture medium (Colla et al., 2010; Matsumoto et al., 2004) and fulfilling a simple recovery of the extracellular enzyme, mycelia or spore (Matsumoto et al., 2004). Although SmF has certain advantages, SSF has gained an enormous momentum thanks to its numerous advantages over the SmF (Das and Mukherjee, 2007; Ghribi et al., 2012; Kriaa and Kammoun, 2016). Actually, SSF has allowed a simple product downstream processing. It has the advantages of using simple equipment (Colla et al., 2010). Moreover, as a result of less medium dilution, we obtain fewer waste effluent issues along with stability of the product. These facts permit to save water and energy (Banat et al., 2021; Kreling et al., 2020), a lower production cost (Das and Mukherjee, 2007), a less bacterial contamination risk (Thomas et al., 2013) as well as the acquirement of higher concentration of products in comparison to SmF (Colla et al., 2010). Moreover, SSF is an eco-friendly strategy that involves the development of microorganisms on moist solid substrate in the absence (Das and Mukherjee, 2007) or near-absence of free-flowing water (Banat et al., 2021; Rodríguez et al., 2020; Thomas et al., 2013). As remarked in Fig. 3, the contour plots for the SSF system were found to be concentric and parallels to each other. These plots showed that the maximum of BioS production was mainly located at the center of the experimental space. Xu et al. (2008) reported in previous studies that a perfect interaction between the independent variables allowed the obtaining of elliptical contours. In addition, the contour diagram's surface contained within the smallest ellipse showed the largest expected value. (Tanyildizi et al., 2007). The Response Surface contour plots and the regression equation's solution revealed that the use of 25 g of Aleppo pine waste humidified at 75% by TRIKI effluent and inoculated with B. subtilis SPB1 with an inoculum size of 0.2 lead to a production yield of 27.59 ± 1.63 mg/g in SSF. Any overflow or overload in one of these values could influence the final yield (Ghribi et al., 2012). This production rate was similar to that obtained with the same strain (28 mg/g) by using 5.66 g of potato waste flour and 4.34 g of tuna fish flour by means of a moisture tenor of 76% (Mnif et al., 2013). Moreover, it was close to the highest yield ever recorded for B. subtilis SPB1 in SSF using, a combination of 6 g of olive leaf residue flour and 4 g of olive cake flour inoculated by an initial OD600 of 0.08 with a total weight of the solid substrate of 10 g and 90% moisture content (Zouari et al., 2015b).

Fig. 2.

Visualization BioS production under SmF as function of the different physicochemical factors: response surface plot (left) and its contour plot (right) of interaction between (A) Aleppo pine waste and ratio; (B) Aleppo pine waste and inoculum size

Fig. 3.

Visualization BioS production under SSF as function of the different physicochemical factors: response surface plot (left) and its contour plot (right) of interaction between (A) moisture and Aleppo pine waste; (B) moisture and inoculum size; (C) Aleppo pine waste and inoculum size

The corresponding experiment under the optimized values obtained by the response surface methodology was performed three times and the average yield value was determined. The BioS production for SSF and SmF were respectively 30.59 mg/g and 17.44 mg/g while the predicted values were respectively 27.59 mg/g and 17.16 mg/g. These differences in BioS production yields (by SSF and SmF) were definitely linked to the fermentation design, particularly aeration and humidification that ensures an appropriate water activity for development (Matsumoto et al., 2004). It was reported that when compared to genetically changed microorganisms, wild-type strains of bacteria and fungus performed better in SSF systems (Das and Mukherjee, 2007). It was clear that SPB1 BioS production yield increased after SSF application and was 1.6 times higher than SmF, hence, and as stated in many earlier reports, confirming the effectiveness of SSF for metabolites production namely enzymes and secondary active compounds (Kriaa and Kammoun, 2016; Matsumoto et al., 2004; Mnif et al., 2013). For instance, compared to SmF, SSF permit to produce two times more hydrophobins (in mg/g of biomass) by Pleurotus ostraeus (Kulkarni et al., 2020). El-Housseiny et al. (2019), also, noted an increase in rhamnolipid formation in SSF that was three times more than in SmF. For instance, by using soybean curd residue (Okara), Ohno et al. proved that biosurfactant production by either B. subtilis NB22 (Ohno et al., 1993) or B. subtilis MI113 (Ohno et al., 1995) was higher with SSF comparing to SmF.

In addition, as described by Mizumoto et al. (2006), Iturin A production in SSF was approximately ten-fold higher than that in SmF after 4 days incubation of B. subtilis RB14-CS on soybean curd residue. Moreover, Camilios-Neto et al. (2008) reported that SSF might be a good substitute for SmF in the formation of rhamnolipids. In fact, on the basis of the volume of percolating solution amended to the solid support, P. aeruginosa UFPEDA 614 produced the best yield of rhamnolipid of the order of 46 g/L (Camilios-Neto et al., 2008). This value was considered as good as the ones obtained in SmF.

Notably, the microorganism’s physiology and genetic behavior developed on solid surfaces may explain the benefits of the SSF method over SmF (Kriaa and Kammoun, 2016). As the microorganisms in SSF were raised in similar conditions to the natural ones, they become able to produce microbial compounds that were more effective than those produced in the SmF (Goes and Sheppard, 1999), even if the liquid fermentation was carried out with optimal conditions for growth and development (Thomas et al., 2013). Therefore, it was suggested that the main biological mechanism involved in the benefits of SSF was cell adhesion on solid surface (Kriaa and Kammoun, 2016). Therefore, the metabolic efficiency of microorganisms grown in water suspension could be reduced. In this regards, the natural habitats of microorganisms might be deemed to be violated by submerged fermentation technology (Hölker et al., 2004). Moreover, submerged liquid culture in bioreactors involved forced aeration and agitation. Hence microorganisms’ production could create many issues such as severe foaming (Neto et al., 2008; Thomas et al., 2013). The process might become less productive as a result of the foaming, which also raises the possibility of contamination. The mechanical methods and/or anti-foaming agents could reduce the foam. However, these techniques were not very successful and raised the expenses of operating bioreactors or performing subsequent process (Neto et al., 2008). Besides, the medium viscosity could sometimes increase due to the exo-polysaccharides formation (Thomas et al., 2013). For that, SSF appeared as an interesting and promoting alternative in several prospective applications for the industrial production of value added products (Das and Mukherjee, 2007).

Generally, fermentation technique was explored to produce several secondary metabolites by microorganisms, which present high benefits to individuals and industries. Regarding previous studies, both SSF and SmF have been applied at the research level. However, some techniques showed a better yield and results than the others. A lot of work still needs to be done in order to determine the best fermentation techniques for each bioactive compound. Regarding the current work, effectiveness of B. subtilis SPB1 to produce BioS in these two fermentation systems was compared. In fact, it was clear that the SPB1 BioS production yield was significantly much higher in SSF than in SmF. Moreover, the use of Aleppo pine waste as a substrate in SSF for B. subtilis to produce BioS turned out to be an optimum option. This bioconversion approach of wastes to useful products can greatly reduce the costs associated with producing BioS and result in a moderate usage of residues, whichmay help to preserve the ecological balance (Zouari et al., 2015b). Although a huge work remains to be fulfilled to grant its industrial application, the observations obtained here indicate that the biotransformation of solid waste to secondary bioactive metabolites could be the optimum approach to lower the production cost.

Acknowledgements

The Ministry of Higher Education, Scientific Research, and Technology of Tunisia provided grants in support of this work. The authors want to sincerely thank Moulin TRIKI Group for their support.

Abbreviations

- BB

Box Behnken

- BioS

Biosurfactants

- SmF

Submerged fermentation

- SSF

Solid state fermentation

Authors contributions

The first author of the present manuscript Dr MB realized and writes this paper. The second author Dr IM helped in the redaction of the paper. Dr IH helped in the realization of the experiences. Professor MAT and Professor DG helped in the elaboration of the plan of this work and corrected this paper.

Funding

The work is funded by the Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research and the Higher Education-Tunisia-Protection of Plants Researcher.

Data availability

All data and materials are available.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest to be declared.

Ethical approval

The studies were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institution or practice at which. They don’t involve the use of animals.

Consent to participate

All individuals taking part in the study gave their informed consent.

Consent to publish

All the authors give the Publisher the permission to publish the Work in Food Science and Biotechnology.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Mouna Bouassida, Email: mouna.bouassida.enis@gmail.com.

Inès Mnif, Email: inesmnif2011@gmail.com.

Ines Hammami, Email: inesmellouli@yahoo.fr.

Mohamed-Ali Triki, Email: trikimali@yahoo.fr.

Dhouha Ghribi, Email: dhouha.ghribi@isbs.usf.tn.

References

- Almeida DG, Soares da Silva RdCF, Luna JM, Rufino RD, Santos VA, Sarubbo LA. Response surface methodology for optimizing the production of biosurfactant by Candida tropicalis on industrial waste substrates. Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 157 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Al-Reza SM, Rahman A, Ahmed Y, Kang SC. Inhibition of plant pathogens in vitro and in vivo with essential oil and organic extracts of Cestrum nocturnum L. Pesticide Biochemistry and Physiology. 2010;96:86–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pestbp.2009.09.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Banat IM, Carboué Q, Saucedo-Castañeda G, de Jesús Cázares-Marinero J. Biosurfactants: The green generation of speciality chemicals and potential production using Solid-State fermentation (SSF) technology. Bioresource TechnolOgy. 2021;320:124222. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bajpai VK, Kang S, Xu H, Lee S-G, Baek K-H, Kang SC. Potential roles of essential oils on controlling plant pathogenic bacteria Xanthomonas species: a review. Plant Pathology Journal. 2011;27(3):207–224. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.2011.27.3.207. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barros FFC, Ponezi AN, Pastore GM. Production of biosurfactant by Bacillus subtilis LB5a on a pilot scale using cassava wastewater as substrate. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;35:1071–1078. doi: 10.1007/s10295-008-0385-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Abdallah D, Frikha-Gargouri O, Tounsi S. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain 32a as a source of lipopeptides for biocontrol of Agrobacterium tumefaciens strains. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2015;119:196–207. doi: 10.1111/jam.12797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben Gharsa H, Bouri M, Mougou Hamdane A. Schuster C, Leclerque A, Rhouma A. Bacillus velezensis strain MBY2, a potential agent for the management of crown gall disease. Plos one. 16: e0252823 (2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bouassida M, Ghazala I, Ellouze-Chaabouni S, Ghribi D. Improved biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis SPB1 mutant obtained by random mutagenesis and its application in enhanced oil recovery in a sand system. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. l28: 95–104 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Box GE, Behnken DW. Some new three level designs for the study of quantitative variables. Technometrics. 1960;2:455–475. doi: 10.1080/00401706.1960.10489912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant CM, McClements DJ. Influence of sucrose on NaCl-induced gelation of heat denatured whey protein solutions. Food Research International. 2000;33:649–653. doi: 10.1016/S0963-9969(00)00109-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Camilios-Neto D, Meira JA, de Araújo JM, Mitchell DA, Krieger N. Optimization of the production of rhamnolipids by Pseudomonas aeruginosa UFPEDA 614 in solid-state culture. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2008;81:441–448. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1663-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y, Xu Z, Ling N, Yuan Y, Yang X, Chen L, Shen B, Shen Q. Isolation and identification of lipopeptides produced by B. subtilis SQR 9 for suppressing Fusarium wilt of cucumber. Scientia Horticulturae. 135: 32–39 (2012)

- Carolin CF, Kumar PS, Ngueagni PT. A review on new aspects of lipopeptide biosurfactant: Types, production, properties and its application in the bioremediation process. Journal of Hazardous Materials. 2021;407:124827. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2020.124827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Li D, Li R, Shen F, Xiao G, Zhou JJCE. Enhanced biosurfactant production in a continuous fermentation coupled with in situ foam separation. Chemical Engineering Processing-Process Intensification. 2020;159:108206. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2020.108206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Wang X, Liu Y. Contribution of macrolactin in Bacillus velezensis CLA178 to the antagonistic activities against Agrobacterium tumefaciens C58. Archives of Microbiology. 2021;203(4):1743–1752. doi: 10.1007/s00203-020-02141-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho KM, Math RK, Hong SY, Islam SMA, Mandanna DK, Cho JJ, Yun MG, Kim JM, Yun HD. Iturin produced by Bacillus pumilusHY1 from Korean soybean sauce (kanjang) inhibits growth of aflatoxin producing fungi. Food Control. 2009;20:402–406. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2008.07.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Colla LM, Rizzardi J, Pinto MH, Reinehr CO, Bertolin TE, Costa JAV. Simultaneous production of lipases and biosurfactants by submerged and solid-state bioprocesses. Bioresource TechnolOgy. 2010;101:8308–8314. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2010.05.086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damalas CA, Eleftherohorinos IG. Pesticide exposure, safety issues, and risk assessment indicators. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2011;8:1402–1419. doi: 10.3390/ijerph8051402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das K, Mukherjee AK. Comparison of lipopeptide biosurfactants production by Bacillus subtilis strains in submerged and solid state fermentation systems using a cheap carbon source: some industrial applications of biosurfactants. Process BiochemIstry. 2007;42:1191–1199. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2007.05.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Des Grades ZE, der Agrarwissenschaften D, Fakultät HL, Wilhelms RF. Biological control of leaf pathogens of tomato plants by Bacillus subtilis (strain FZB24): antagonistic effects and induced plant resistance. Inaugural-Dissertation, Institute of Crop Science and Resource Conservation—Phytomedicine, vorgelegt am 06.06.2012 (2012)

- Ebtsam MM, Abdel-Kawi KA, Khalil MNA. Efficiency of Trichoderma viride and Bacillus subtilis as biocontrol agents against Fusarium solani on tomato plants. Egyptian Journal of Phytopathology. 2009;37:47–57. [Google Scholar]

- El-Housseiny GS, Aboshanab KM, Aboulwafa MM, Hassouna NA. Rhamnolipid production by a gamma ray-induced Pseudomonas aeruginosa mutant under solid state fermentation. AMB Express. 2019;9:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s13568-018-0732-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar MA, Dandekar AM. Agrobacterium tumefaciensas an agent of disease. Trends in Plant Science. 2003;8:380–386. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(03)00162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferreira GB, Evangelista AF, Severo Junior JB, Souza RR, Santana JCC, Tambourgi EB, Jordão E. Partitioning optimization of proteins from Zea mays malt in ATPS PEG 6000/CaCl2. Food Science and Technology. 2007;50:557–564. [Google Scholar]

- Foldes T, Banhegyi I, Herpai Z, Varga L, Szigeti J. Isolation of Bacillus strains from the rhizosphere of cereals and in vitro screening for antagonism against phytopathogenic, food-borne pathogenic and spoilage micro-organisms. Journal of Applied Microbiology. 2000;89(5):840–846. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2000.01184.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frikha-Gargouri O, Ben Abdallah D, Ghorbel I, Charfeddine I, Jlaiel L, Triki MA, Tounsi S. Lipopeptides from a novel Bacillus methylotrophicus 39b strain suppress Agrobacteriumcrown gall tumours on tomato plants. Pest Management Science. 2017;73:568–574. doi: 10.1002/ps.4331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis F, Sabu A, Nampoothiri KM, Ramachandran S, Ghosh S, Szakacs G, Pandey AJ. Use of response surface methodology for optimizing process parameters for the production of α-amylase by Aspergillus oryzae. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 2003;15(2):107–115. doi: 10.1016/S1369-703X(02)00192-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Franco CM, Michelsen PP, Percy NJ, Conn V, Listiana BE, Moll S, Loria R, Coombs JT. Actinobacterial endophytes for improved crop performance Australas. Plant Pathology. 2007;36:524–531. [Google Scholar]

- Gakuubi MM, Wagacha JM, Dossaji SF, Wanzala W. Chemical Composition and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils ofTagetes minuta (Asteraceae) against Selected Plant Pathogenic Bacteria. International Journal of Microbiology. 2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/7352509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghribi D, Abdelkefi-Mesrati L, Mnif I, Kammoun R, Ayadi I, Saadaoui I, Maktouf S, Chaabouni-Ellouze S. Investigation of antimicrobial activity and statistical optimization of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 biosurfactant production in solid-state fermentation. Journal of Biomedicine and Biotechnology. 2012;2012:373682. doi: 10.1155/2012/373682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghribi D, Ellouze-Chaabouni S. Enhancement of Bacillus subtilis lipopeptide biosurfactants production through optimization of medium composition and adequate control of aeration. Biotechnology Research International. 653654 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ghribi D, Mnif I, Boukedi H, Kammoun R, Ellouze-Chaabouni S. Statistical optimization of low-cost medium for economical production of Bacillus subtilis biosurfactant, a biocontrol agent for the olive moth Prays oleae. African Journal of Microbiological ResEarch. 2011;5(27):4927–4936. [Google Scholar]

- Ghribi D, Zouari N, Trigui W, Jaoua S. Use of sea water as salts source in starch-and soya bean-based media, for the production of Bacillus thuringiensis bioinsecticides. Process Biochemistry. 2007;42(3):374–378. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2006.09.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Goes AP, Sheppard JD. Effect of surfactants on α-amylase production in a solid substrate fermentation process. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 1999;74(7):709–712. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4660(199907)74:7<709::AID-JCTB94>3.0.CO;2-C. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hammami I, Rhouma A, Jaouadi B, Rebai A, Xavier N. Optimization and biochemical characterization of a bacteriocin from a newly isolated Bacillus subtilis strain 14B for biocontrol of Agrobacterium spp. Strains. Letters in Applied Microbiology. 2009;48:253–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02524.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammami I, Triki MA, Rebai A. Purification and characterization of the novel bacteriocin Back IH7 with antifungal and antibacterial properties. Journal of Plant Pathology. 2011;93:443–445. [Google Scholar]

- Hölker U, Höfer M, Lenz JJ. Biotechnological advantages of laboratory-scale solid-state fermentation with fungi. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2004;64:175–186. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1504-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu LB, Shi ZQ, Zhang T, Yang ZM. Fengycin antibiotics isolated from B-FS01 culture inhibit the growth of Fusarium moniliforme Sheldon ATCC38932. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2007;272:91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joshi S, Bharucha C, Jha S, Yadav S, Nerurkar A, Desai AJ. Biosurfactant production using molasses and whey under thermophilic conditions. Bioresource Technology. 2008;99:195–199. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KM, Lee JY, Kim CK, Kang JS. Isolation and Characterization of Surfactin Produced by Bacillus polyfermenticusKJS-2. Archives of Pharmaceutical Research. 2009;32:711–715. doi: 10.1007/s12272-009-1509-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kita N, Ohya T, Uekusa H, Nomura K, Manago M, Shoda M. Biological control of damping-off of tomato seedlings and cucumber Phomopsis root rot by Bacillus subtilis RB14-C. Japanese Agriculture Research Quarterly. 2005;39:109–114. doi: 10.6090/jarq.39.109. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kreling NE, Simon V, Fagundes VD, Thomé A, Colla LM. Simultaneous Production of Lipases and Biosurfactants in Solid-State Fermentation and Use in Bioremediation. Journal of Environmental Engineering. 146 (2020)

- Kriaa M, Kammoun R. Producing Aspergillus tubingensis CTM507 glucose oxidase by solid state fermentation versus submerged fermentation: process optimization and enzyme stability by an intermediary metabolite in relation with diauxic growth. Journal of Chemical Technology and Biotechnology. 2016;91:1540–1550. doi: 10.1002/jctb.4753. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni SS, Nene SN, Joshi KS. A comparative study of production of hydrophobin like proteins (HYD-LPs) in submerged liquid and solid state fermentation from white rot fungus Pleurotus ostreatus. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology. 2020;23:101440. doi: 10.1016/j.bcab.2019.101440. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kuo CY. Optimization of cultivation conditions for iturin A production by Bacillus subtilis using solid state fermentation. M.S. thesis, Da-Yeh University, Taiwan (2006)

- Leclère V, Béchet M, Adam A, Guez J-S, Wathelet B, Ongena M, Thonart P, Gancel F, Chollet-Imbert M, Jacques P. Mycosubtilin overproduction by Bacillus subtilis BBG100 enhances the organism’s antagonistic and biocontrol activities. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 2005;71:4577–4584. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4577-4584.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leelasuphakul W, Hemmanee P, Chuenchitt S. Growth inhibitory properties of Bacillus subtilis strains and their metabolites against the green mold pathogen (Penicillium digitatum Sacc.) of citrus fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 48: 113–121 (2008)

- Li L, Ma MC, Huang R, Qu Q, Li GH, Zhou JW, Zhang KQ, Lu KP, Niu XM, Luo J. Induction of chlamydospore formation in Fusarium by cyclic lipopeptide antibiotics from Bacillus subtilis C2. Journal of Chemical Ecology. 2012;38:966–974. doi: 10.1007/s10886-012-0171-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu K, Sun Y, Cao M, Wang J, Lu JR, Xu H. Rational design properties and applications of biosurfactants: a short review of recent advances. Current Opinion in Colloid and Interfacial SciEnce. 2012;45:57–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cocis.2019.12.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malviya D, Sahu PK, Singh UB, Paul S, Gupta A, Gupta AR, Singh S, Kumar M, Paul D, Rai JP, Singh HV, Brahmaprakash GP. Lesson from Ecotoxicity: Revisiting the Microbial Lipopeptides for the Management of Emerging Diseases for Crop Protection. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17(4):1434. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17041434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathieu D. Phan-Tan-Lu R. Logiciel Nemrod: LPRAI, Marseille (2000)

- Matsumoto Y, Saucedo-Castañeda G, Revah S, Shirai K. Production of β-N-acetyl hexosaminidase of Verticillium lecanii by solid state and submerged fermentations utilizing shrimp waste silage as substrate and inducer. Process Biochemistry. 2004;39(6):665–671. doi: 10.1016/S0032-9592(03)00140-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McKeen C, Reily C, Pusey P. Production and partial characterization of antifungal substances antagonistic to Monilia fructicola from Bacillus subtilis. Phytopathology. 1986;76:136–139. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-76-136. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mizumoto S, Hirai M, Shoda M. Production of lipopeptide antibiotic iturin A using soybean curd residue cultivated with Bacillus subtilis in solid-state fermentation. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2006;72:869–875. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnif I, Bouallegue A, Bouassida M, Ghribi D. Surface properties and heavy metals chelation of lipopeptides biosurfactants produced from date lour by Bacillus subtilis ZNI5: optimized production for application in bioremediation. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00449-021-02635-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnif I, Rajhi H, Bouallegue A, Trabelsi N, Ghribi D. Characterization of Lipopeptides Biosurfactants Produced by a Newly Isolated Strain Bacillus subtilis ZNI5: Potential Environmental Application. Journal of Polymers and the Environment. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s10924-021-02361-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mnif I, Bouallegue A, Mekki S, Ghribi D. Valorization of date juice by the production of lipopeptide biosurfactants by a Bacillus mojavensis BI2 strain: bioprocess optimization by response surface methodology and study of surface activities. Bioprocess and Biosystems Engineering. 2021 doi: 10.1007/s00449-021-02606-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnif I, Elleuch M, Chaabouni ES, Ghribi D. Bacillus subtilis SPB1 biosurfactant: Production optimization and insecticidal activity against the carob moth Ectomyelois ceratoniae. Crop Protection. 2013;50:66–72. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2013.03.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mnif I, Ellouze-Chaabouni S, Ghribi D. Optimization of the Nutritional Parameters for Enhanced Production of B. subtilis SPB1 Biosurfactant in Submerged Culture Using Response Surface Methodology. Biotechnology Research International. Article ID 795430, 8 10.1155/2012/795430 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Mnif I, Grau-Campistany A, Coronel-León J, Hammami I, Triki MA, Manresa A, Ghribi D. Purification and identification of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 lipopeptide biosurfactant exhibiting antifungal activity against Rhizoctonia bataticola and Rhizoctonia solani. Environmental Science and Pollution Research International. 2016;23:6690–6699. doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5826-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mnif I, Hammami I, Triki M-A, Cheffi Azabou M, Ellouze-Chaabouni S, Ghribi D. Antifungal efficiency of a lipopeptide biosurfactant derived from Bacillus subtilis SPB1 versus the phytopathogenic fungus, Fusarium solani. Environmental Science and Pollution Research. 2015 doi: 10.1007/s11356-015-5005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montealegre JR, Errera R, Velásquez JC, Silva P, Besoaín X, Pérez LM. Biocontrol of root and crown rot in tomatoes under greenhouse conditions using Trichoderma harzianum and Paenibacillus lentimorbus, Additional effect of solarization. Electronic Journal of Biotechnology. 2005;8:250–257. doi: 10.2225/vol8-issue3-fulltext-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mora I, Cabrefiga J, Montesinos E. Cyclic Lipopeptide Biosynthetic Genes and Products, and Inhibitory Activity of Plant-Associated Bacillus against Phytopathogenic Bacteria. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(5):e0127738. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukherjee S, Das P, Sen R. Towards commercial production of microbial surfactants. Trends in Biotechnology. 2006;24:509–515. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nihorimbere V, Ongena M, Cawoy H, Brostaux Y, Kakana P, Jourdan E, Thonart P. Beneficial effects of Bacillus subtilis on field grown tomato in Burundi: reduction of local Fusarium disease and growth promotion. African Journal of Microbiological Research. 2010;4:1135–1142. [Google Scholar]

- Ohno A, Ano T, Shoda M. Production of a lipopeptide antibiotic surfactin by recombinant Bacillus subtilis in solid state fermentation. Biotechnology and Bioengineering. 1995;47(2):209–214. doi: 10.1002/bit.260470212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohno A, Ano T, Shoda MJ. Production of the antifungal peptide antibiotic iturin by Bacillus subtilis NB22 in solid state fermentation. Biochemical Engineering. 1993;75:23–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ongena M, Jacques P. Bacillus lipopeptides: versatile weapons for plant disease biocontrol. Trends in Microbiology. 2008;16:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson D The chemical analysis of foods. Longman Group Ltd (1976)

- Penyalver R, Lopez MM. Cocolonization of the rhizosphere by pathogenic agrobacterium strains and nonpathogenic strains K84 and K1026, used for crown gall biocontrol. Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 1999;65:1936–1940. doi: 10.1128/AEM.65.5.1936-1940.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira JF, Gudiña EJ, Costa R, Vitorino R, Teixeira JA, Coutinho JA, Rodrigues LR. Optimization and characterization of biosurfactant production by Bacillus subtilis isolates towards microbial enhanced oil recovery applications. Fuel. 2013;111:259–268. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2013.04.040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Phae C, Shoda M, Kubota N. Suppressive effect of Bacillus subtilis and it’s products on phytopathogenic microorganisms. Journal of Fermentation and Bioengineering. 69: 1–7 (1990)

- Raveau R, Fontaine J, Lounès-Hadj AS. Essential Oils as Potential Alternative Biocontrol Products against Plant Pathogens and Weeds: A Review. Foods. 2020;9:365. doi: 10.3390/foods9030365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebib H, Hedi A, Rousset M, Boudabous A, Limam F, Sadfi-Zouaoui N. Biological control of Fusarium foot rot of wheat using fengycin-producing Bacillus subtilis isolated from salty soil. African Journal of Biotechnology. 2012;11:8464–8475. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez A, Gea T, Sánchez A, Font X. Agro-wastes and Inert Materials as Supports for the Production of Biosurfactants by Solid-state Fermentation Waste and Biomass Valorization. 1963–1976 (2020)

- Sen R, Swaminathan T. Application of response-surface methodology to evaluate the optimum environmental conditions for the enhanced production of surfactin. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1997;47:358–363. doi: 10.1007/s002530050940. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sidney W. Official methods of analysis of the association of official analytical chemists. Register for the 2021 AOAC Annual Meeting, August 27 - September 2, 2021 in Boston, MA; 1984 (1984)

- Singh A, Van Hamme JD, Ward OP. Surfactants in microbiology and biotechnology: Part 2. Application Aspects. Biotechnology Advancements. 2007;25:99–121. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2006.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smibert R, Krieg N, Gerhardt P, Murray R, Wood WJW. DC: American Society for Microbiology. Methods for General and Molecular Bacteriology. pp. 607–654 (1994)

- Soylu EM, Kurt S, Soylu S. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of the essential oils of various plants against tomato grey mould disease agent Botrytis cinerea. International Journal of Food Microbiology. 2010;143:183–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2010.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanyildizi MS, Özer D, Elibol M. Production of bacterial α-amylase by B. amyloliquefaciens under solid substrate fermentation. Biochemical Engineering Journal. 37: 294–297 (2007)

- Thomas L, Larroche C, Pandey A. Current developments in solid-state fermentation. Biochemical Engineering JOurnal. 2013;8:146–161. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2013.10.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Todorova S, Kozhuharova L. Characteristics and antimicrobial activity of Bacillus subtilis strains isolated from soil. World Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology. 2010;26(7):1207–1216. doi: 10.1007/s11274-009-0290-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trigui M, Ben Hsouna A, Hammami I, Culioli G, Ksantini M, Tounsi S, Jaoua S. Efficacy of Lawsonia inermis leaves extract and its phenolic compounds against olive knot and crown gall diseases. Crop ProtectIon. 2013;45:83–88. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2012.11.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Triki MA, Hammami I, Krid Hadj-Taieb S, Daami-Remadi M, Mseddi A, El Mahjoub M, Gdoura R, Khammasy N. Biological control of atypical pink rot disease of potato in Tunisia. Global Science Books Pesticide Technology. 2012;6:60–64. [Google Scholar]

- Van Hamme JD, Singh A, Ward OP. Physiological aspects. Part 1 in a series of papers devoted to surfactants in microbiology and biotechnology. Biotechnology Advances. 24: 604–620 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Wang J, Sun M, Liu Z, Yu Z. Co-producing lipopeptides and poly-γ-glutamic acid by solid-state fermentation of Bacillus subtilis using soybean and sweet potato residues and its biocontrol and fertilizer synergistic effects. Bioresource Technology. 2008;99:3318–3323. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H, Sun L-P, Shi Y-Z, Wu Y-H, Zhang B, Zhao D-Q. Optimization of cultivation conditions for extracellular polysaccharide and mycelium biomass by Morchella esculenta. Biochemical Engineering JOurnal. 2008;39(1):66–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bej.2007.08.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu JX, Li ZY, Lv X, Yan H, Zhou GY, Cao LX, Yang Q, He YH. Isolation and characterization of Bacillus subtilis strain 1-L-29, an endophytic bacteria from Camellia oleifera with antimicrobial activity and efficient plant-root colonization. PLoS One. 2020;15(4):e0232096. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0232096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yangui T, Sayadi S, Dhouib A. Sensitivity of Pectobacterium carotovorum to hydroxytyrosol-rich extracts and their effect on the development of soft rot in potato tubers during storage. Crop Protection. 2013;53:52–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cropro.2013.06.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zoina A, Raio A. Susceptibility of some peach rootstocks to crown gall. Journal of Plant Pathology. 1999;81:181–187. [Google Scholar]

- Zouari R, Ben Abdallah-Kolsi R, Hamden K, Feki AE, Chaabouni K, Makni-Ayadi F, Sallemi F, Ellouze-Chaabouni S, Ghribi Aydi D. Assessment of the antidiabetic and antilipidemic properties of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 biosurfactant in alloxan induced diabetic rats. Biopolymers. 2015;104(6):764–774. doi: 10.1002/bip.22705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zouari R, Chaabouni ES, Ghribi D. Optimization of Bacillus subtilis SPB1 Biosurfactant Production Under Solid-state Fermentation Using By-products of a Traditional Olive Mill Factory. Achievements in Life Science. 2015;8:162–169. doi: 10.1016/j.als.2015.04.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zouari R, Chaabouni ES, Ghribi D. Use of butter milk and poultry-transforming wastes for enhanced production of bacillus subtilis SPB1 biosurfactant in submerged fermentation. Journal of Microbiology and Biotechnology and Food Science. 2015 doi: 10.15414/jmbfs.2015.4.5.462-46. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data and materials are available.