Abstract

The aim of this study is to formulate a stable water-in-oil-in-water (W1/O/W2) double emulsion using different types of oils and electrolytes. W1/O was formulated with different electrolyte solutions (W1) dispersed in various oils (O) using polyglycerol polyricinoleate as a stabilizer. External aqueous phase was Tween-80 (W2), and W1/O dispersed in W2 was used. The emulsion containing NaCl or MgCl2 exhibited high encapsulation efficiency (EE) and maintained particle size. Regarding the oil type, the emulsion with MCT oil showed a small droplet size and a high viscosity and EE, presenting a stable droplet distribution in optical observation. The stability of emulsion containing NaCl was maintained during the in vitro digestion experiments. MCT oil, NaCl and MgCl2 have the potential to produce stable double emulsions for storage stability and in vitro digestion studies. The findings would be useful for preparing stable double emulsions used in the food and cosmetic industries.

Keywords: Double emulsion, Electrolyte, Emulsion stability, In vitro digestion model

Introduction

Double water-in-oil-in-water (W1/O/W2) emulsions are colloidal dispersions of compartmentalized liquid dispersions, often known as emulsions or emulsions inside emulsions (Choi and McClements, 2020). Emulsions can solubilize hydrophobic and hydrophilic sources, covering unpleasant odors and tastes, with high bioavailability, excellent absorption capacity, and utility in controlled release systems (Harwansh et al., 2019). W1/O/W2 double emulsions are widely used in various industries, including pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and food. However, their poor stability hinders their widespread use (Mun et al., 2015). Moreover, encapsulation using emulsions protects the core materials from environmental factors, such as temperature, oil oxidation, and pH (Jo et al., 2015). Emulsions are thermodynamically unstable because of unfavorable change in free energy after emulsification, in addition to their short shelf life and difficult handling (Lee et al., 2013). The issue of emulsion instability is governed by several factors, including emulsion viscosity, droplet size, and water droplet distribution in oil (Jeong et al., 2021). Instability can lead to creaming, coalescence, flocculation, sedimentation, phase separation, and Ostwald ripening (Kale and Deore, 2017; Lee et al., 2023; McClements, 2004). Coalescence is caused by combining droplets, flocculation is caused by droplets sticking together (but not combining), Ostwald ripening is caused by larger droplets growing at the expense of smaller droplets, and creaming is where droplets rise due to buoyancy, leading to phase separation, while droplets settle in sedimentation (Gupta et al., 2016). Thus, the applicability of emulsions is limited by their poor physicochemical stability.

Extensive efforts have been made to optimize W1/O/W2 double emulsion manufacturing to increase stability. The addition of stabilizers (Park and Kim, 2021; Wang et al., 2017), reduction of droplet size (Hebishy et al., 2017), inner and external phase fractions (Matos et al., 2018), and osmotic balance between water phases (García et al., 2019) have important effects on emulsion stability. In addition, studies have been conducted on digestion stability and control-release patterns (using gastric juices) of probiotics (Marefati et al., 2021) and bioactive substances, such as betalain (Kaimainen et al., 2015), kafirin (Xiao et al., 2017), anthocyanin (Haung and Zhou, 2019), and resveratrol (Shi et al., 2021). However, there have been few studies related to lipid digestion.

In a previous study, we prepared W1/O/W2 double emulsions with different inner emulsion fractions and osmotic agents in an attempt to improve their physicochemical stability (Kwak et al., 2022). In the study, we reported on the optimal inner phase fraction and electrolyte based on the droplet size, ζ-potential, viscosity, microscopy image, and encapsulation efficiency (EE). In the present study, we investigate the influence of electrolyte and carrier oil types on emulsion stability. Various electrolytes, such as NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, and Na2CO3, were used, and investigations were done on the effects of cations such as KCl, NaCl, and MgCl2 and anions such as Na2CO3 as well as monovalent such as K+, Na+, and Cl− and multivalent ions such as Mg2+, and CO32−. A variety of carrier oils were chosen; corn oil, medium chain triglycerides (MCTs), fish oil, coconut oil, and orange oil. MCT, corn oil, coconut oil and fish oil are all triglyceride oils that are digestible by lipase. Coconut oil composed to lauric acid and palmitic acid, and MCT oil contain high levels of saturated fatty acids and form a solid and liquid state at 25 °C, respectively (Dayrit, 2014; Marten et al. 2006). Long chain triglycerides such as corn oil and fish oil are both examples, but corn oil contains a high percentage of monounsaturated fatty acids while fish oil has a high percentage of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Whereas orange oil is an example of indigestible oils (Ozturk et al., 2015). Therefore, the objective is the production of a stable W1/O/W2 double emulsion with effective electrolyte and oil type during storage and its incubation in the simulated gastrointestinal fluids.

Materials and methods

Materials

NaCl (sodium chloride, Duksan Pure Chemicals Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Korea), potassium chloride (Duksan, Korea), MgCl2 (magnesium chloride, Yakuri Chemicals Co., Ltd., Japan), and CaCl2 (anhydrous calcium chloride, Daejung Chemicals and Metals Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Korea) were used to compare stability according to the electrolyte type. As oil phases of double emulsion, corn oil (local market, Seoul, Korea), and fish oil (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA) were chosen as a representative unsaturated fatty acid and long chain triglyceride. MCT oil (Cosnet Industries, Coulans-sur-Gée, France), and coconut oil (Deajung) were chosen as a representative saturated fatty acid and MCT. Orange oil (Sigma-Aldrich) was selected as unsaturated fatty acid and contains terpene, which is effect on antioxidant. PGPR (polyglycerol polyricinoleate 9090) (Muslim Mas, Indonesia) and Tween-80 (polyoxyethylene sorbitan monooleate) (Samchun Pure Chemical Co., Ltd., Gyeonggi-do, Korea) were used as emulsifiers. Rhodamine B was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used to dye the inner water, while Nile red (Sigma-Aldrich) was used to dye the oil phase for observation by confocal laser scanning microscopy (CLSM). All other reagents were of analytical grade or higher.

Preparation of double emulsions (W1/O/W2 emulsions)

To produce inner emulsions (W1/O emulsions), 1% electrolytes, such as NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, and CaCl2, were dissolved in the inner water phase (W1-phase), respectively. The oil phase, such as corn, MCT, fish, coconut, and orange, contained 5% (w/w) PGPR as a hydrophobic emulsifier. The W1/O emulsions consisted of a 30% (w/w) dispersed inner phase and a 70% (w/w) continuous oil phase. The W1-phase was slowly poured into the continuous oil phase and stirred using a propeller stirrer (Propeller Stirrer, Chang Shin Scientific Co., Ltd., South Korea) at 700 rpm for 3 min. The W1/O emulsion was then homogenized using a high-speed homogenizer (T25 digital IKA®; Ultra-Turrax®, Germany) at 15,000 rpm for 5 min.

The outer water phase (W2) was prepared by dissolving 1% (w/w) Tween-80 as the hydrophilic emulsifier. The ratio of W1/O to W2 was 1:1 (w/w). W1/O was slowly added to W2 and stirred using a propeller stirrer at 700 rpm for 3 min. The premixed emulsion was further homogenized using a high-speed homogenizer (T25 digital IKA®; Ultra-Turrax®, NJ, USA) at 10,000 rpm for 2 min.

Interfacial tension

The interfacial tension between the internal water phases and corn oil (pure oil or 5% w/w PGPR oil) was measured using a tensiometer® (Sigma 703D; Sigma-Aldrich) and the Du Nouy ring method. The ring was wetted in the water phase, and the oil phase was added to the interface of the water phase. The maximum value was recorded when the layer between the two phases was broken by slowly raising the ring. All measurements were repeated in triplicate at 25 °C.

Emulsion characterization

Droplet size and distribution

The mean droplet size and distribution of the W1/O and W1/O/W2 emulsions were characterized using a laser diffraction analyzer (Mastersizer 3000E; Malvern, UK). The droplet size distribution was calculated using the Mie theory.

For the measurements, the W1/O and W1/O/W2 emulsions were dispersed in the oil phase solved with 5% PGPR (i.e. the same continuous oil phase used for emulsion production) and demineralized water, respectively. The refractive indices of the continuous and dispersant phase were set to 1.52 and 1.33 (W1/O emulsion) and 1.52 and 1.47 (W1/O/W2 emulsion). The volume-weighted mean (D4,3) was used as the average droplet size of the emulsion. The span value was represented as the distribution width and has a value of 1 for a symmetrical distribution, as described in Eq. (1):

| 1 |

DV10: droplet diameter below 10% of sample (cm), DV50: droplet diameter below 50% of sample (cm), DV90: droplet diameter below 90% of sample (cm), where DV10, DV50, and DV90 are the equivalent volume diameters at 10%, 50%, and 90% of the cumulative diameter, respectively.

ζ-Potential measurement

The W1/O/W2 emulsions were diluted (1:500, w/w) and measured using a Zetasizer (Zetasizer® Nano ZS 90; Malvern) in triplicate. The refractive indices of the continuous and dispersant phases were set as 1.472 and 1.333, respectively. All analyses were conducted in triplicate at 25 °C.

Viscosity

The viscosities of the W1/O and W1/O/W2 emulsions were characterized using a rotational rheometer (MCR 302; Anton Paar, Graz, Austria) with cup and bob geometry (bob diameter 26.659 mm; cup diameter 28.940 mm). A logarithmic shear experiment was conducted by increasing the shear rate from 0.1 to 1000 s−1. All measurements were repeated in triplicate at 25 °C. For the analysis, only viscosity at a shear rate of 10 s−1 was compared.

Microscopic observation

Images of the W1/O/W2 emulsions were observed using an optical microscope (CX 31; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) equipped with a CCD camera (3.0M; Olympus) connected to the relevant software. The W1/O/W2 emulsions were placed on a microscope slide and covered with cover glass. After a drop of immersion oil was placed on the cover glass, the samples were observed at magnification of × 400 and × 1000.

Encapsulation efficiency (EE)

To measure the EE (%) of the W1/O/W2 emulsion, the inner aqueous phase was stained with 200 ppm rhodamine B dye before W1/O/W2 emulsion preparation. The stained emulsions (6 g) and demineralized water (6 g) were mixed with a vortex mixer and centrifuged at 15,000 rpm and 4 °C for 90 min using a centrifuge (Labogene 1736R; Gyrozen Co. Ltd., Gimpo, Korea) to separate the creamed layer (upper) and the serum layer (bottom). The separated serum layer was filtrated through a 0.45-μm syringe filter to remove oil droplets, and the absorbance of the free dye solution was measured using a UV/Vis spectrophotometer (Multiskan Go, Thermo Scientific, MA, USA) at 553 nm. The fraction of rhodamine B present in the serum layer was determined from the standard curve. The EE was then calculated as a percentage using Eq. (2):

| 2 |

where A0 is the amount of encapsulated dye solution present in the internal aqueous phase and A1 is the amount of free dye solution present in the external aqueous phase.

In vitro digestion

In this study, the in vitro digestion model consisted of three steps: the mouth, stomach, and small intestine. The simulated saliva and gastric, duodenal, and bile fluids were prepared as described in Carolien et al. (2005). During in vitro digestion, the samples were swirled at 60 rpm and 37 °C using a shaking water bath (BF-305B; Biofree, Gyeonggi-do, Korea) to simulate the motility of the GI tract. In the mouth, the sample and saliva solution were mixed in a ratio of 5:6 and digested for 3 min. In the stomach, the sample was passed through the mouth, and gastric fluid was mixed at a ratio of 1:1 and digested for 2 h. In the small intestine, the samples passed through the stomach, duodenal fluid, and bile fluid were mixed at a ratio of 4:2:1 and digested for 2 h. After digestion for 1 h, the pH of the sample was regulated using 1 N HCl solution and 1 N-NaOH solution in the stomach and small intestinal phases.

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

CLSM (LSM 800; Carl Zeiss Microscope System, Jena, Germany) was used to capture images of the double emulsion according to the digestion phases. The emulsions were dyed with 0.5 wt% Nile red (1 mg/mL in ethanol). CLSM was performed using laser excitation sources (488 nm), and fluorescent images were acquired using an oil immersion objective at a magnification of × 400.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data was performed using SPSS software (version 15.0, SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The results are expressed as the mean ± standard deviation of at least three experiments. One-way ANOVA with post hoc Tukey’s multiple range test was used for the analysis of parametric data. A significance level of p ≤ 0.05 was used for all evaluations.

Results and discussion

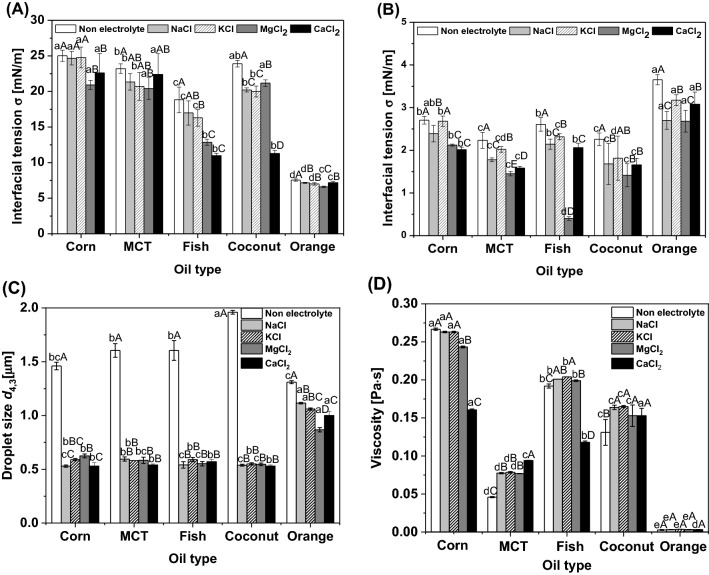

Interfacial tension

The interfacial tensions between the inner water and oil phases with the electrolyte and oil types are shown in Fig. 1(A) and (B). The addition of 5% PGPR to the oil phase resulted in a marked decrease in the interfacial tension. PGPR, which is a hydrophobic emulsifier, decreases the difference in facial energy between the water and oil phases, and therefore prevents coalescence and aggregation by decreasing the interfacial tension (Kralova and Sjoblom, 2009; Walstra, 1993). The interfacial tension between water without electrolyte and oil phases was significantly higher than that with electrolyte (p < 0.05). This is because the addition of an electrolyte to the inner water phase decreases the interfacial tension by enhancing the adsorption of the emulsifier between the water and oil phases (Lamba et al., 2015). In addition, there are also differences between monovalent and divalent ions, and divalent ions with higher electronegativity (Ca2+ and Mg2+) showed lower interfacial tension than monovalent ions (Na+ and K+). Because the higher electronegativity pulls electrons more strongly and better polarizes hydrated water ligands due to its higher charge density, the stronger interaction between surfactant heads and water ligands results (hydrogen bonding) (Mahmoudvand et al., 2021). Moreover, interfacial tension of Na+ ion was lower than K+ ion due to electronegativity of Na+ ions relatively higher than that of K+ ions. Among the types of oil, the corn, MCT, and coconut oils showed relatively high interfacial tension, while orange oil showed a significantly low value. Orange oil, which has high solubility, is vulnerable to Ostwald ripening; hence, it has a low viscosity and interfacial tension (Lim et al., 2011). According to Jasper et al. (1970), the difference in interfacial tension with oil type is caused by different carbohydrate chain structures of the oils. A comparison of the interfacial tensions between the water and oil phases with PGPR, NaCl, and MgCl2, which have anions corresponding to three periods, indicated a significantly lower interfacial tension, while KCl, which has anions corresponding to the fourth period, showed high values (p < 0.05). These results are similar to those of a previous study in which NaCl and MgCl2 had lower values than KCl and CaCl2 when comparing the interfacial tension according to NaCl, KCl, MgCl2, and CaCl2 (Márquez et al., 2010). Among the oil types, MCT and coconut oils, which are medium-chain saturated fatty acids, and fish oils, which are long-chain unsaturated fatty acids, showed lower interfacial tension than corn oil, which is a long-chain unsaturated fatty acid, and orange oil, which is an aromatic oil. The interfacial tension increases as the length of the fatty acid chain increases (Yoon et al., 2015). Therefore, the interfacial tension of corn oil was high regardless of the addition of surfactants. Fish oil showed low interfacial tension despite its long fatty acid chain, which was caused by visible impurities. The impurities in oil can be adsorbed at the interface between the water and oil phases, which also decreases the interfacial tension (Souilem et al., 2014).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of inner emulsions (W/O type). Interfacial tension (A–B), mean droplet size (C) and viscosity (D) with different oil types and water phases with different electrolyte types in the water phase. Oil phase without PGPR (A) and with 5% PGPR (B). a–eResults labeled with different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in electrolyte type (p < 0.05). A–DResults labeled with different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in oil type (p < 0.05)

Droplet size and viscosity of W/O emulsions

The droplet sizes and viscosities of the W/O emulsions produced using different electrolytes and oils are shown in Fig. 1(C) and (D). The droplet sizes of the W/O emulsion without the electrolyte were significantly larger than those with the electrolyte regardless of the oil type (p < 0.05). In the result of W/O emulsion with electrolytes, the dispersity of water droplets is higher due to the presence of a charge, which affects the particle size distribution reduction. In addition, emulsions with electrolyte showed significantly stable compared to emulsions without electrolytes. This result was similar to that of another study that reported a decrease in droplet size with the addition of an electrolyte (Keowmaneechai and McClements, 2022; Márquez et al, 2010). For the oil types, the droplet size of the W/O emulsion containing orange oil was significantly larger (p < 0.05), and the tendency among corn, MCT, fish, and coconut oil was not significant (p > 0.05). Similarly, Zhang et al. (2016) described that orange oil is relatively high polarity and interfacial tension compared to triglyceride oils (MCT oil). In addition, the large droplet size of emulsions containing orange oil corresponding to flavor oils, such as lemon oil, can be explained by the characteristics of low viscosity and high water solubility, which can induce Ostwald ripening (Lim et al., 2011; Rao and McClements, 2012).

The addition of various electrolytes to the water phases at equivalent concentrations did not result in significant changes in viscosity. The viscosity of emulsion contained KCl was slightly higher than others. Similarly, Calvo et al. (1998) reported that monovalent and divalent cations induce viscosity increases in solutions of extracellular polymers. In particular, the viscosity was the highest in the case of monovalent cations in the potassium solution. Because the effect of the characteristics of the oil, and density and stability of emulsions was greater than electrolyte types. For the oil types, the viscosity was in the following: of corn (0.066 Pa∙s) > fish (0.058 Pa∙s) > coconut (0.057 Pa∙s) > MCT (0.039 Pa∙s) > orange oil (0.002 Pa∙s) (data not shown). In other words, the W/O emulsions with long-chain fatty acids had the highest viscosity, whereas the W/O emulsions with aroma oil had the lowest viscosity. The viscosity of the oil with 5% PGPR showed a similar tendency to that of the W/O emulsion according to the oil type. This result indicates that the viscosity of the W/O emulsion was directly affected by the viscosity of the oil. In addition, oil with long-chain fatty acids had a high viscosity owing to the affinity between the fatty acid molecules, and the high viscosity of the oil is influenced by a high degree of unsaturation when the length of the fatty acid is the same (Yoon et al., 2015).

Characteristic of W1/O/W2 emulsions

The droplet size, span value, ζ-potential, and viscosity of the double emulsions with different types of electrolytes and oils are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the W1/O/W2 emulsions with different oil and electrolyte types at the time of fabrication (day 0, A) and after 60 days (B) of storage

| (A) | Oil type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte type | Corn | MCT | Fish | Coconut | Orange |

| Droplet size D4,3 (µm)1 | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | 31.5 ± 0.38aC | 21.5 ± 0.06cD | 28.3 ± 0.12bC | 31.0 ± 0.20aC | 10.9 ± 0.10dC |

| NaCl | 42.9 ± 4.31abAB | 34.9 ± 0.12cBC | 46.0 ± 0.17aB | 40.0 ± 2.31bcB | 15.3 ± 0.78dB |

| KCl | 42.8 ± 1.57bAB | 35.1 ± 0.10cB | 50.2 ± 0.06aA | 50.2 ± 0.35aA | 16.3 ± 0.75dB |

| MgCl2 | 40.3 ± 0.21cB | 34.3 ± 0.06dC | 46.1 ± 0.46aB | 42.1 ± 0.29bB | 19.0 ± 1.22eA |

| CaCl2 | 46.0 ± 0.23bA | 37.2 ± 0.61cA | 51.0 ± 2.82aA | 43.0 ± 0.67bB | 17.1 ± 0.93dAB |

| Span value | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | 0.89 ± 0.01dC | 1.25 ± 0.01aA | 1.16 ± 0.02bD | 1.02 ± 0.01cD | 1.14 ± 0.02bAB |

| NaCl | 1.19 ± 0.01bB | 1.21 ± 0.01bB | 1.34 ± 0.02abB | 1.25 ± 0.02bAB | 1.52 ± 0.16aA |

| KCl | 1.30 ± 0.04aA | 1.22 ± 0.01bB | 1.26 ± 0.04abC | 1.20 ± 0.02bBC | 0.88 ± 0.22cB |

| MgCl2 | 1.25 ± 0.02abAB | 1.21 ± 0.01abB | 1.34 ± 0.02aB | 1.17 ± 0.01bC | 1.03 ± 0.11cB |

| CaCl2 | 1.23 ± 0.02bAB | 1.28 ± 0.02bA | 3.34 ± 0.03aA | 1.31 ± 0.03bA | 1.08 ± 0.28bB |

| ζ-Potential (mV) | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | − 34.3 ± 2.05cA | − 39.2 ± 0.70bA | − 37.3 ± 0.81bcA | − 40.8 ± 1.75bA | − 50.7 ± 1.72aA |

| NaCl | − 30.6 ± 0.95cB | − 30.6 ± 0.23cC | − 33.7 ± 0.21bB | − 33.4 ± 1.48bB | − 47.0 ± 1.20aB |

| KCl | − 29.1 ± 0.35dB | − 37.9 ± 0.17bA | − 33.5 ± 0.92cB | − 33.2 ± 1.56cB | − 41.5 ± 0.50aC |

| MgCl2 | − 25.7 ± 0.51cC | − 25.6 ± 0.78cD | − 32.4 ± 0.70bB | − 30.5 ± 0.72bB | − 34.6 ± 0.61aD |

| CaCl2 | − 31.0 ± 0.53dB | − 34.7 ± 0.67dB | − 32.9 ± 0.66bcB | − 31.4 ± 0.91cdB | − 43.8 ± 0.50aC |

| Viscosity (Pa·s)2 | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | 0.007 ± 0.00abD | 0.005 ± 0.00bE | 0.007 ± 0.00bE | 0.010 ± 0.00aB | 0.005 ± 0.00bE |

| NaCl | 3.995 ± 0.13abC | 5.495 ± 0.09abD | 3.295 ± 0.02bcC | 7.440 ± 1.95aA | 0.034 ± 0.00cD |

| KCl | 3.900 ± 0.08cC | 5.965 ± 0.11bC | 2.045 ± 0.01dD | 6.965 ± 0.43aA | 0.322 ± 0.01eB |

| MgCl2 | 6.220 ± 0.18bB | 6.765 ± 0.11bB | 4.095 ± 0.12cA | 8.485 ± 0.62aA | 0.248 ± 0.00dC |

| CaCl2 | 7.210 ± 0.08bA | 8.075 ± 0.13aA | 3.590 ± 0.03cB | 7.505 ± 0.15bA | 0.516 ± 0.01dA |

| (B) | Oil type | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Electrolyte type | Corn | MCT | Fish | Coconut | Orange |

| Droplet size D4,3 (µm) | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | 25.5 ± 0.06bD | 19.6 ± 0.23dC | 22.0 ± 0.31cE | 29.1 ± 0.35aE | 8.73 ± 0.06eD |

| NaCl | 49.5 ± 0.78aB | 34.9 ± 0.12dB | 44.9 ± 0.53bC | 40.1 ± 1.51cD | 14.5 ± 0.10eB |

| KCl | 46.2 ± 1.25bC | 35.2 ± 0.21dB | 39.0 ± 0.32cD | 58.2 ± 1.01aB | 10.8 ± 0.65eC |

| MgCl2 | 47.6 ± 0.40bBC | 35.9 ± 0.70cB | 48.5 ± 0.25abB | 48.7 ± 0.38aC | 19.4 ± 0.44dA |

| CaCl2 | 51.4 ± 0.21cA | 37.7 ± 0.15dA | 54.3 ± 0.96bA | 61.4 ± 1.55aA | 10.0 ± 0.11eC |

| Span value | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | 1.44 ± 0.01bA | 1.40 ± 0.05bA | 1.60 ± 0.04aB | 1.07 ± 0.05cD | 1.43 ± 0.05bC |

| NaCl | 1.27 ± 0.02dCD | 1.18 ± 0.01eB | 1.38 ± 0.01bB | 1.30 ± 0.00cC | 2.72 ± 0.01aA |

| KCl | 1.29 ± 0.01cC | 1.15 ± 0.01dB | 1.47 ± 0.02bB | 1.21 ± 0.01cC | 1.61 ± 0.09aC |

| MgCl2 | 1.33 ± 0.01cB | 1.17 ± 0.04dB | 1.37 ± 0.01bcB | 1.52 ± 0.03bB | 2.22 ± 0.12aB |

| CaCl2 | 1.24 ± 0.01dD | 1.19 ± 0.02dB | 2.73 ± 0.26aA | 2.23 ± 0.07bA | 1.58 ± 0.03cC |

| ζ-Potential (mV) | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | − 38.8 ± 1.21dA | − 41.9 ± 0.78bcA | − 42.5 ± 0.95bA | − 39.2 ± 0.81cdA | − 50.6 ± 1.25aA |

| NaCl | − 34.1 ± 0.76dBC | − 36.8 ± 0.32cB | − 39.6 ± 0.93bB | − 39.6 ± 0.93bA | − 43.0 ± 1.17aB |

| KCl | − 35.9 ± 0.10dB | − 37.8 ± 0.50cB | − 40.0 ± 0.38bB | − 38.7 ± 0.36cA | − 43.9 ± 0.36aB |

| MgCl2 | − 24.9 ± 0.90cD | − 25.3 ± 1.82cC | − 33.1 ± 0.68bC | − 30.7 ± 1.19bB | − 40.2 ± 0.75aC |

| CaCl2 | − 32.9 ± 0.85cC | − 39.2 ± 1.06bAB | − 38.0 ± 0.68bB | − 31.9 ± 0.32cB | − 42.1 ± 1.27aBC |

| Viscosity (Pa·s) | |||||

| Non-electrolyte | 0.004 ± 0.00aC | 0.004 ± 0.00bcC | 0.004 ± 0.00cD | 0.005 ± 0.00aE | 0.003 ± 0.00dD |

| NaCl | 1.835 ± 0.00aB | 0.575 ± 0.00cB | 0.043 ± 0.00dC | 1.180 ± 0.11bD | 0.005 ± 0.00dB |

| KCl | 1.930 ± 0.07aB | 0.546 ± 0.09bB | 0.006 ± 0.00cD | 1.660 ± 0.13aC | 0.004 ± 0.00cC |

| MgCl2 | 3.580 ± 0.00aA | 0.933 ± 0.00cA | 0.268 ± 0.00dA | 3.360 ± 0.07bA | 0.010 ± 0.00eA |

| CaCl2 | 3.360 ± 0.25aA | 0.774 ± 0.12bAB | 0.072 ± 0.00cB | 3.000 ± 0.06aB | 0.005 ± 0.00cB |

The percentage was expressed on a weight basis

1D4,3: volume weighted mean; 2Viscosity was measured at 10 s−1 of shear rate 10 s−1

a–eResults labeled with different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in electrolyte type (p < 0.05)

A–EResults labeled with different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in oil type (p < 0.05)

The double emulsion without the electrolyte had a smaller droplet size than the double emulsion with the electrolyte, which can be explained by the fact that water migrates from the inner to the external phase by osmotic pressure, inducing a reduction in droplet size (Sapei et al., 2012; Zhu et al., 2018). Orange oil showed the smallest droplet size in the double emulsion, followed by MCT oil, and fish oil had the largest droplet size (p < 0.05). Small oil droplets are produced when the viscosity of oil is low because of low interfacial tension (Reed et al., 2009). Therefore, orange and MCT oils, which have low viscosity, showed a small droplet size, whereas fish oil showed a large droplet size owing to visible impurities despite low viscosity.

Over the 60 days storage period, the droplet size of the double emulsion without electrolyte decreased regardless of the oil type, and the cause of the shrinkage of oil droplets is an osmotic imbalance between the inner and external water phases, which induces the migration of water (Muschiolik and Dickinson, 2017). The droplet size with the electrolyte was increased after storage except for orange oil. The osmotic gradient can be induced by the shrinkage or swelling of W/O emulsion droplet commercially. For preventing the osmotic gradient, we formulated the W1/O/W2 emulsion composed to free electrolyte outer water phase and electrolyte dissolved inner water phase. The electrolyte of inner water phase decreases the Gibbs free energy more than outer water phase (Kulmyrzaev and Schubert, 2004). Thus, the diffusion of inner water occurs due to the osmotic gradient. The droplet size of W/O emulsion increases by osmotic swelling (Schmidts et al., 2010). Upon comparison according to oil types, orange oil showed a decreasing tendency over time, whereas corn or coconut oil showed an increasing tendency, except for the non-electrolyte after 60 days. The double emulsion without the electrolyte had a smaller droplet size than that with the electrolyte. KCl showed the smallest droplet size, and CaCl2 showed the largest droplet size in comparison with the electrolyte types with respect to the time of fabrication (p < 0.05). In the case of MCT oil, there were no changes in the oil droplet size of the double emulsion after 60 days in comparison with the time of fabrication. The droplet size of the double emulsion containing orange oil was the smallest, followed by that containing MCT oil, and that containing coconut oil was significantly larger (p < 0.05).

The span value did not show a significant tendency for the electrolyte and oil types regardless of the time of fabrication and after 60 days. After 60 days, the span value of the double emulsion without electrolyte increased, and the span values of the double emulsions containing corn, coconut, and orange oil all increased, whereas those containing MCT and fish oil decreased, except for the non-electrolyte.

The ζ-potential, which shows repulsion between droplets, was the highest in the double emulsion without electrolyte, and the ζ-potential magnitude of the double emulsion containing MgCl2 showed the lowest value according to the electrolyte type. Orange oil has the highest ζ-potential magnitude of double emulsion, and corn oil has the lowest magnitude according to the oil type. After 60 days, the ζ-potential magnitude of the double ion tended to increase, and the addition of the electrolyte increased the attraction between the ions of the droplet surface, which induced a decrease in the ζ-potential magnitude (Morais et al., 2006; Rios et al., 1993). In addition, Keowmaneechai and McClements (2022) reported that the ζ-potential magnitude was affected by divalent ions more than by monovalent ions in double emulsions. Therefore, double emulsions containing divalent ions, such as MgCl2 and CaCl2, showed a lower ζ-potential magnitude than those containing monovalent ions, such as NaCl2 and KCl. The ζ-potential according to oil type is influenced by the free fatty acids and phospholipids of the oil phase (Yuan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b), wherein the magnitude was in the following order: corn < MCT < coconut < fish < orange oil. Similarly, Qian et al. (2012) reported a high ζ-potential magnitude of orange oil in comparison with corn, MCT, and orange oil. In addition, a previous study that compared the ζ-potential of the O/W emulsions showed the following order: fish > MCT > corn oil (Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b).

All double emulsions showed pseudoplastic characteristics, in which viscosity decreased as the shear rate increased, regardless of the electrolyte and oil type (data not shown). The viscosity according to oil type at the time of fabrication showed high values in the following order: CaCl2 > MgCl2 > NaCl > KCl > non-electrolyte, according to electrolyte type, and coconut > MCT > corn > fish > orange. Divalent ions, such as MgCl2 and CaCl2, have a lower ζ-potential magnitude than monovalent ions, such as NaCl and KCl. These low magnitudes would promote aggregation between droplets, inducing a change in viscosity (Keowmaneechai and McClements, 2022). The aggregation between droplets in the emulsion influences the increase in viscosity (Keowmaneechai and McClements, 2022; Lim et al., 2011). The viscosity of the double emulsion without electrolyte was the lowest, while that with MgCl2 was the highest after 60 days of storage (p < 0.05). According to Schmidts et al. (2009), when comparing the viscosity of double emulsions with added glucose, glycine, NaCl, and MgSO4 in the inner water phase, the double emulsion with divalent ions, such as MgCl2, showed the highest viscosity. These results were similar to those reported in the present study. After storage, the viscosity of all double emulsions decreased because the migration of water occurred between the inner and external water phases through the oil phase (Schmidts et al., 2009), which caused the thinning and destruction of the oil phase. These phenomena decrease the content of the inner water droplets, resulting in a reduction in viscosity (Matsumoto and Kohda, 1980).

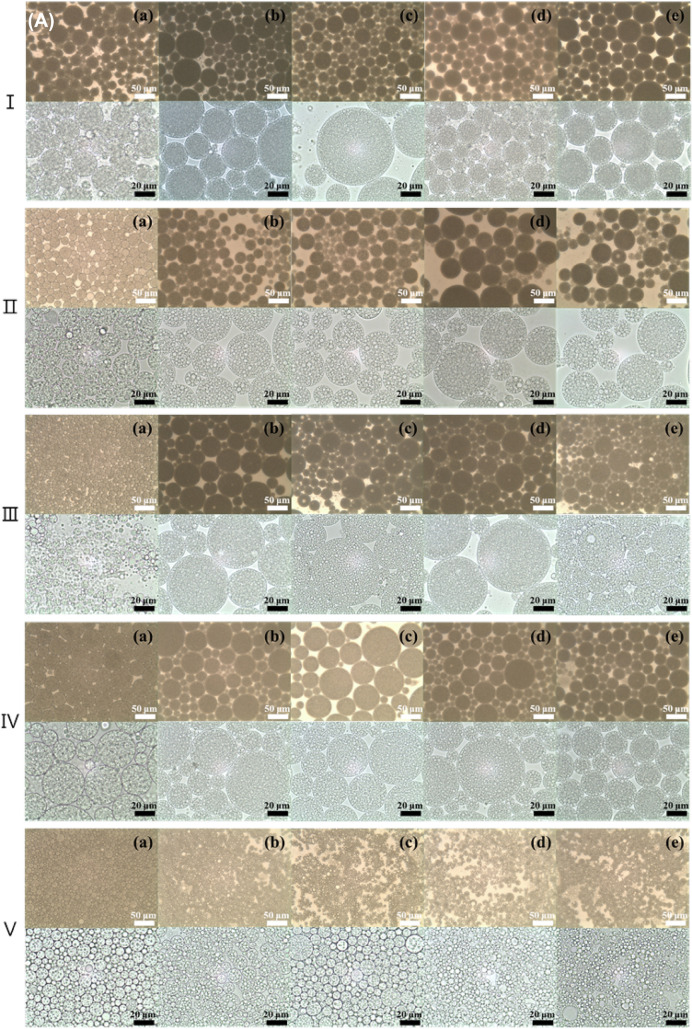

Optical microscopy

Figure 2 shows images of different morphologies of the double emulsion generated by different electrolytes in the inner water phase and oils during the storage period. A general double emulsion consisting of W/O emulsion droplets in the external water phase was observed, regardless of the electrolyte and oil type (Fig. 2). As shown in Table 1, the droplet size of the double emulsion without the electrolyte was the smallest regardless of the oil type, and the encapsulated inner water droplets were significantly smaller (p < 0.05). The droplet size of the double emulsion containing orange oil was smaller than that of the double emulsion containing fish oil, which showed a large droplet size. In the double emulsions without electrolyte, the oil droplets tended to be smaller after 60 days, and extrusion of the inner water droplets encapsulated in the oil phase was observed at a magnification of × 1000. The small water droplets in the oil phase were more densely encapsulated in double emulsions containing MgCl2 than in double emulsions containing other electrolytes. In addition, MgCl2 showed no obvious changes in the droplet size of the double emulsion with time, which is in accordance with the droplet size measurement results shown in Table 1. Herzi and Essafi (2018) reported that the emulsion containing MgCl2 almost did not change over 30 days, observed via microscopy. In addition, double emulsions containing corn or MCT oil were observed to have more densely encapsulated inner water droplets than the other oil types. After 60 days, all double emulsions showed an increasing tendency in the size of the inner water droplets, and extrusion of the inner water droplets was observed. In addition, the unstable double emulsions exhibited noticeable coalescence and aggregation between droplets.

Fig. 2.

Optical microscopy images of W1/O/W2 emulsions with different oil and electrolyte types at the time of fabrication (day 0, A) and after 60 days (B) of storage. (I) corn, (II) MCT, (III) fish, (IV) coconut, and (V) orange oil. (a) Non-electrolyte, (b) NaCl, (c) KCl, (d) MgCl2, and (e) CaCl2. All the electrolytes were dissolved at 1% in the W1-phase

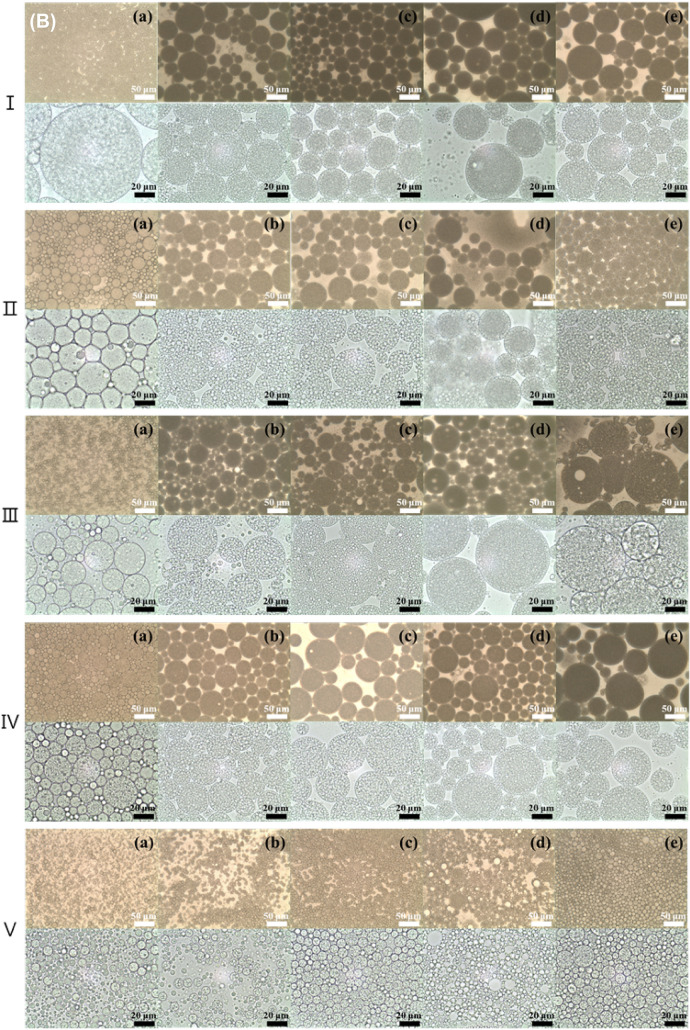

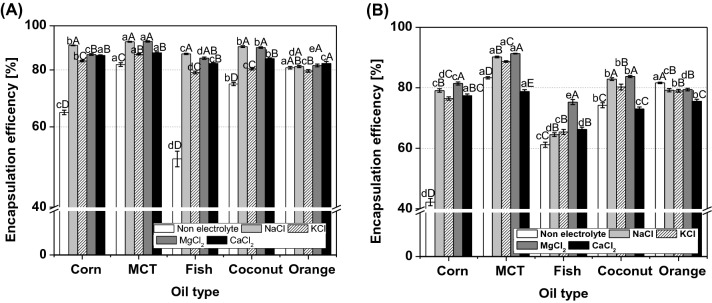

Encapsulation efficiency

The EE of double emulsions with different electrolytes and oils at 0 day and after 60 days is shown in Fig. 3. The EE of the double emulsions were in the following order, according to oil type: NaCl > MgCl2 > CaCl2 > KCl > non-electrolyte, according to electrolyte type, and MCT > corn > coconut > fish > orange oil. Bonnet et al. (2009) measured the EE of MgCl2 according to the oil type and found that the EE increased as the viscosity increased. Therefore, corn, MCT, and coconut oils, which have high viscosity, showed a higher EE than fish and orange oils, which have a low viscosity. Furthermore, orange oil with a high interfacial tension is thermodynamically unstable and has a lower density than water phase (Figs. 1 and 3), which induces a low EE with layer separation. After 60 days, the EE of all double emulsions decreased. Thermodynamically unstable double emulsions become more unstable with time, causing coalescence, flocculation, and Ostwald ripening (Saberi et al., 2013). The EE value of the double emulsion containing MgCl2 and NaCl was significantly higher. The double emulsions without electrolyte showed the lowest EE, as well as a small droplet size by extrusion of water from the inner to the external over time. This was clarified through microscopy images showing markedly fewer inner water droplets than the other double emulsions (Fig. 2). The double emulsions containing MgCl2 showed small and dense inner water droplets in the oil phase in the microscopy image and had a high viscosity, as shown in Table 1. This affects the high stability of the double emulsion, which also affects the EE. The EE was in the following order according to oil type: MCT > coconut > corn and orange > fish oil (p < 0.05). MCT and coconut oil, which have a high ζ-potential and viscosity, showed higher EE than corn oil. In addition, the small droplet size of the double emulsion containing MCT oil resulted in a lower speed of droplet movement than droplets of large size, which slowed gravitational separation (Yildirim et al., 2017). Therefore, these high storage stabilities were found to affect the high EE after 60 days.

Fig. 3.

Encapsulation efficiencies of W1/O/W2 emulsions with different oil and electrolyte types at the time of fabrication (day 0, A) and after 60 days (B) of storage. a–eResults labeled with different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in electrolyte type (p < 0.05). A–EResults labeled with different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in oil type (p < 0.05)

In vitro digestion

Droplet size and ζ-potential

In this study, NaCl was selected as a representative electrolyte, and the stability of the double emulsion by different oil types in in vitro digestion was investigated. The droplet size and ζ-potential of the double emulsions with NaCl addition and oil type are shown in Fig. 4(A) and (B). The droplet size of the double emulsions without NaCl increased as the stage of the in vitro digestion model proceeded, whereas that containing NaCl tended to decrease. Mucin induces bridging flocculation and depletion flocculation in double emulsions without NaCl at the oral stage, which affects aggregation and increases droplet size (Yuan et al., 2018). Bridging flocculation results from the attachment of more than two mucin molecules on the surface of oil droplets, whereas depletion flocculation results from an increase in osmotic pressure induced between mucin molecules that were not adsorbed (Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b). Flocculation increased at the simulated stage because of the decrease in repulsion between droplets and the increase in droplet size resulting from bridge flocculation induced by mucine (Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b). In addition, lipase degrades triglycerol into free fatty acids and monoacylglycerol, which induces flocculation, and therefore droplet size increases at the small intestine stage (Qian et al., 2012). Flocculation of in vitro digestion is induced by relatively weak molecular interactions; therefore, flocculated droplets become redispersed when diluted with simulated gastric juice and stirred to measure the droplet size (Ozturk et al., 2015). In addition, the degradation of oil by lipase induces instability in the double emulsions, such as flocculation and aggregation, whereas it decreases the droplet size of oil (Ozturk et al., 2015). Thus, the droplets of the double emulsion without NaCl with a low stability increase in size due to flocculation and coalescence. In contrast, the double emulsion with NaCl, which has a high stability, showed a decreasing tendency in droplet size because of dilution by gastric juice and stirring for measurement of droplet size despite flocculation by the constituents of gastric juice. Thus, the droplets that did not coalesce and flocculated were redispersed in water, and the droplet size was decreased by lipase at the stage of small intestine. Similarly, Hur et al. (2009) reported that emulsions with a large droplet size before digestion had a decreasing tendency because of degradation at the stomach stage. However, emulsions with small droplet sizes showed an increase in droplet size by coalescence.

Fig. 4.

Influence of simulated gastrointestinal conditions on mean droplet size (A), ζ-potential (B) and encapsulation efficiency (C) of W1/O/W2 emulsions with different oil types and electrolytes. a–eResults labeled with different lowercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in electrolyte type (p < 0.05). A–DResults labeled with different uppercase letters indicate statistically significant differences in oil type (p < 0.05)

The magnitude of the ζ-potential showed a decreasing tendency from the initial stage to the mouth and stomach, whereas it showed an increasing tendency at the stage of the small intestine. The reduction of the ζ-potential magnitude at the simulated mouth stage resulted from the electrostatic effect of the mineral ions of saliva and mucine adsorbed onto the surface of the oil droplets (Rios et al., 1993). It was also induced by a weakened repulsion between droplets due to free ions of gastric juice and the low pH environment in the stomach (Gasa-Falcon et al., 2019). The excessive increase in the ζ-potential magnitude in the small intestine was induced by the adsorption of negative ions, such as bile, digestion enzyme, calcium, phospholipid, and free fatty acids, on the surface of the droplets (Qian et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b). In addition, triacylglycerol is degraded into fatty acid and monoacylglycerol by lipase in the small intestine, and fatty acid increases the ζ-potential magnitude of the droplet surface (Waraho et al., 2011). The droplet size of the W/O emulsions and flocculation between droplets affect the surface area of the oil exposed on the digestion enzyme, and the electric charge directly affects the interfacial characteristics of the droplets. Therefore, droplet size, ζ-potential, and flocculation are important because they interact with each other and affect the physical and structural characteristics of emulsion droplets (Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b). The change in droplet size with the digestion stage resulted from the droplet size and the stability of the double emulsion before digestion, with no effect of the oil type.

Encapsulation efficiency

The EE of the double emulsions during in vitro digestion is shown in Fig. 4(C). The double emulsion without NaCl had a smaller droplet size and showed greater flocculation than the double emulsion containing NaCl during digestion. The EE of all double emulsions decreased as they passed through the initial, mouth, stomach, and small intestine stages. The double emulsion containing NaCl at the initial and mouth stages showed a high EE. However, this tendency was not observed in the stomach and small intestine stages with the addition of NaCl. The EE of double emulsions containing NaCl followed the order: MCT > corn > coconut. By contrast, the double emulsion without NaCl showed a high EE, in the following order: MCT > coconut > corn. According to previous studies, the EE of corn oil, which has long-chain fatty acids, was higher than that of MCT and coconut oil, which have medium-chain fatty acids (Ozturk et al., 2015; Qian et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b). This is because corn oil, which has long-chain fatty acids (C16 and C18), has a higher possibility of producing micelles than MCT and coconut oil, which have relatively short medium-chain fatty acids (C8 and C10) and micelles, and is easily emulsified (Yuan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b). In addition, long-chain fatty acids are large enough to contain core elements; however, medium-chain fatty acids are insufficient (Ozturk et al., 2015).

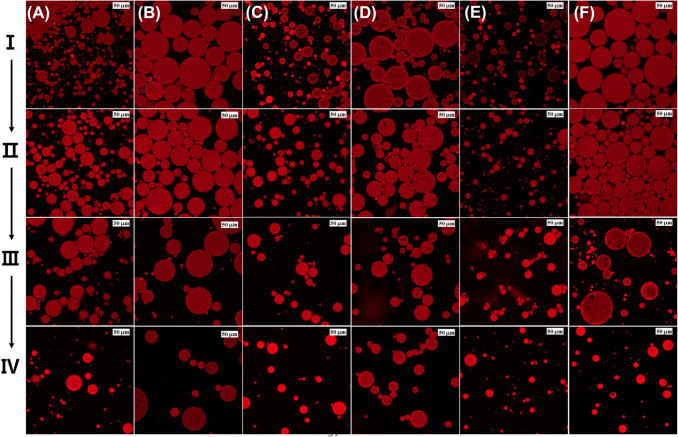

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

The morphology of droplets during in vitro digestion is important for understanding the stability of double emulsions with different oil types (Yuan et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2015a; 2015b), the results of which are shown in Fig. 5. No significant differences were observed between oil types. The droplet size of the double emulsions containing NaCl was larger than that of the double emulsion without NaCl, while the double emulsion without NaCl showed over double the flocculation of the emulsion with NaCl during digestion. The density of droplets decreased through the simulated stomach stage, which was similar to a previous study in which the density of the surface area of oil was calculated after observation through CLSM (Hur et al., 2009). The reduction in the density of the oil droplets through the simulated digestion stage was induced by the dilution of the simulated digestion fluid. In addition, lipase in the small intestine promotes oil degradation and induces a reduction in oil density (Hur et al., 2009). Therefore, the density of droplets decreased as the simulated digestion passed, and the difference in oil types was not shown through CLSM.

Fig. 5.

Influence of simulated gastrointestinal conditions on confocal images of W1/O/W2 emulsions with different oil types and electrolytes. (A) Non-electrolyte and corn oil, (B) NaCl and corn oil, (C) non-electrolyte and MCT oil, (D) NaCl and MCT oil, (E) non-electrolyte and coconut oil, and (F) NaCl and coconut oil: (I) before digestion, (II) saliva juice after 5 min, (III) gastric juice after 2 h, and (IV) duodenal and bile juice after 2 h. NaCl was dissolved at 1% in the W1-phase

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education (2022R1A6A1A03055869).

Abbreviations

- W1/O/W2

Water-in-oil-in-water

- EE

Encapsulation efficiency

- PGPR

Polyglycerol polyricinoleate

- CLSM

Confocal laser scanning microscopy

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Bonnet M, Cansell M, Berkaoui A, Ropers MH, Anton M, Leal-Calderon F. Release rate profiles of magnesium from multiple W/O/W emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2009;23:92–101. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2007.11.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Calvo C, Martinez-Checa F, Mota A, Bejar V, Quesada E. Effect of cations, pH and sulfate content on the viscosity and emulsifying activity of the Halomonas eurihalina exopolysaccharide. Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology. 1998;20:205–209. doi: 10.1038/sj.jim.2900513. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carolien HM, Versantvoort H, Oomen AG, Van de Kamp E, Rompelberg CJM, Adrienne JAM. Sips applicability of an in vitro digestion model in assessing the bioaccessibility of mycotoxins from food. Food and Chemical Toxicology. 43: 31-40 (2005) [DOI] [PubMed]

- Choi SJ, McClements DJ. Nanoemulsions as delivery systems for lipophilic nutraceuticals: strategies for improving their formulation, stability, functionality and bioavailability. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2020;29:149–168. doi: 10.1007/s10068-019-00731-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dayrit FM. Lauric acid is a medium-chain fatty acid, coconut oil is a medium-chain triglyceride. Philippine Journal of Science. 2014;143:157–166. [Google Scholar]

- García MC, Muñoz J, Alfaro-Rodriguez MC, Franco JM. Formulation variables influencing the properties and physical stability of green multiple emulsions stabilized with a copolymer. Colloid and Polymer Science. 2019;297:1095–1104. doi: 10.1007/s00396-019-04529-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gasa-Falcon A, Odriozola-Serrano I, Oms-Oliu G, Martin-Belloso O. Impact of emulsifier nature and concentration on the stability of β-carotene enriched nanoemulsions during in vitro digestion. Food and Function Journal. 2019;10:713–722. doi: 10.1039/C8FO02069H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta A, Eral HB, Hatton TA, Doyle PS. Nanoemulsions: formation, properties and applications. Soft Matter. 2016;12:2826–2841. doi: 10.1039/C5SM02958A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harwansh RK, Deshmukh R, Rahman MA. Nanoemulsion: promising nanocarrier system for delivery of herbal bioactives. Journal of Drug Delivery Science and Technology. 2019;51:224–233. doi: 10.1016/j.jddst.2019.03.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Haung Y, Zhou W. Microencapsulation of anthocyanins through two-step emulsification and release characteristics during in vitro digestion. Food Chemistry. 2019;278:357–363. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebishy E, Buffa M, Juan B, Blasco-Moreno A, Trujillo AJ. Ultra high-pressure homogenized emulsions stabilized by sodium caseinate: effects of protein concentration and pressure on emulsions structure and stability. LWT: Food Science and Technology. 2017;76:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2016.10.045. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Herzi S, Essafi W. Different magnesium release profiles from W/O/W emulsions based on crystallized oils. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2018;509:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2017.08.089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hur SJ, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Influence of initial emulsifier type on microstructural changes occurring in emulsified lipids during in vitro digestion. Food Chemistry. 2009;114:253–262. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2008.09.069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jasper JJ, Nakonecznyj M, SwingIey S, Livingston HK. Interfacial tensions against water of some C10–C15 hydrocarbons with aromatic or cycloaliphatic rings. Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1970;74:1535. doi: 10.1021/j100702a023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SJ, Kim S, Echeverria-Jaramillo E, Shin WS. Effect of the emulsifier type on the physicochemical stability and in vitro digestibility of a lutein/zeaxanthin-enriched emulsion. Food Science and Biotechnology. 30: 1509-1518 (2021) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Jo YJ, Kwon YJ, Min SG, Choi MJ. Effect of NaCl concentration on the emulsifying properties of myofibrillar protein in the soybean oil and fish oil emulsion. Food Science of Animal Resources. 2015;35:315–321. doi: 10.5851/kosfa.2015.35.3.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaimainen M, Marze S, Järvenpää E, Anton M, Huopalahtia R. Encapsulation of betalain into w/o/w double emulsion and release during in vitro intestinal lipid digestion. LWT: Food Science and Technology. 2015;60:899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2014.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kale SN, Deore SL. Emulsion micro emulsion and nano emulsion: a review. Systematic Reviews in Pharmacy. 2017;8:39–47. doi: 10.5530/srp.2017.1.8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Keowmaneechai E, McClements DJ. Effect of CaCl2 and KCl on physiochemical properties of model nutritional beverages based on whey protein stabilized oil-in-water emulsions. Journal of Food Science. 2022;67:665–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2002.tb10657.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kralova I, Sjoblom J. Surfactants used in food industry: a review. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2009;30:1363–1383. doi: 10.1080/01932690902735561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kulmyrzaev AA, Schubert H. Influence of KCl on the physicochemical properties of whey protein stabilized emulsions. Food Hydrocolloids. 2004;18:13–19. doi: 10.1016/S0268-005X(03)00037-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak E, Lee J, Jo YJ, Choi MJ. Effect of electrolytes in the water phase on the stability of W1/O/W2 double emulsions. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 2022;650:129471. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2022.129471. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lamba H, Sathish K, Sabikhi L. Double emulsion: emerging delivery system for plant bioactives. Food and Bioprocess Technology. 2015;8:709–728. doi: 10.1007/s11947-014-1468-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee MY, Min SG, You SK, Choi MJ, Hong GP, Chun JY. Effect of β-cyclodextrin on physical properties of nanocapsules manufactured by emulsion-diffusion method. Journal of Food Engineering. 2013;119:588–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.06.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Wi G, Choi MJ. The rheological properties and stability of gelled emulsions applying to κ-carrageenan and methyl cellulose as an animal fat replacement. Food Hydrocolloids. 2023;136:108243. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2022.108243. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lim SS, Baik MY, Decker EY, Henson L, Popplewell M, McClements DJ, Choi SJ. Stabilization of orange oil-in-water emulsions: a new role for ester gum as an Ostwald ripening inhibitor. Food Chemistry. 2011;128:1023–1028. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mahmoudvand M, Javadi A, Pourafshary P, Vatanparast H, Bahramian A. Effects of cation salinity on the dynamic interfacial tension and viscoelasticity of a water–oil system. Journal of Petroleum Science and Engineering. 2021;206:108970. doi: 10.1016/j.petrol.2021.108970. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marefati A, Pitsiladis P, Oscarsson E, Ilestam N, Bergenståhl B. Encapsulation of Lactobacillus reuteri in W1/O/W2 double emulsions: formulation, storage and in vitro gastro-intestinal digestion stability. LWT: Food Science and Technology. 2021;146:111423. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2021.111423. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Márquez AL, Medrano A, Panizzolo LA, Wagner JR. Effect of calcium salts and surfactant concentration on the stability of water-in-oil (w/o) emulsions prepared with polyglycerol polyricinoleate. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2010;341:101–108. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marten B, Pfeuffer M, Schrezenmeir J. Medium-chain triglycerides. International Dairy Journal. 2006;16(11):1374–1382. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2006.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matos M, Gutiérrez G, Martínez-Rey L, Iglesias O, Pazos C. Encapsulation of resveratrol using food-grade concentrated double emulsions: emulsion characterization and rheological behaviour. Journal of Food Engineering. 2018;226:73–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.01.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto S, Kohda M. The viscosity of W/O/W emulsions: an attempt to estimate the water permeation coefficient of the oil layer from the viscosity changes in diluted systems on aging under osmotic pressure gradients. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 1980;73:13–20. doi: 10.1016/0021-9797(80)90115-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McClements DJ. Food Emulsions: Principle, Practices, and Techniques. 2. New York: Taylor & Francis; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Morais JM, Santos ODH, Delicato T, Rocha-Filho PA. Characterization and evaluation of electrolyte influence on canola oil/water nano-emulsion. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2006;27:1009–1014. doi: 10.1080/01932690600767056. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mun S, Choi Y, Kim YR. Lipase digestibility of the oil phase in a water-in-oil-in-water emulsion. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2015;24:513–520. doi: 10.1007/s10068-015-0067-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muschiolik G, Dickinson E. Double emulsions relevant to food systems: preparation, stability, and applications. Comprehensive Reviews in Food Science and Food Safety. 2017;16:532–555. doi: 10.1111/1541-4337.12261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozturk B, Argin S, Ozilgen M, McClements DJ. Nanoemulsion delivery systems for oil-soluble vitamins: influence of carrier oil type on lipid digestion and vitamin D3 bioaccessibility. Food Chemistry. 2015;187:499–506. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2015.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park YH, Kim HJ. Formulation and stability of horse oil-in-water emulsion by HLB system. Food Science and Biotechnology. 2021;30:931–938. doi: 10.1007/s10068-021-00934-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian C, Decker EA, Xiao H, McClements DJ. Nanoemulsion delivery systems: influence of carrier oil on β-carotene bioaccessibility. Food Chemistry. 2012;135:1440–1447. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao J, McClements DJ. Food-grade microemulsions and nanoemulsions: role of oil phase composition on formation and stability. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;29:326–334. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.04.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SG, Bertholet S, Coler RN, Friede M. New horizons in adjuvants for vaccine development. Trends in Immunology. 2009;30:23–32. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rios G, Pazos C, Coca J. Destabilization of cutting oil emulsions using inorganic salts as coagulants. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects. 1993;138:383–389. doi: 10.1016/S0927-7757(97)00083-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Saberi AH, Fang Y, McClements DJ. Fabrication of E-enriched nanoemulsions: factors affecting particle size using spontaneous emulsification. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2013;391:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapei L, Naqvi MA, Rousseau D. Stability and release properties of double emulsions for food applications. Food Hydrocolloids. 2012;27:316–323. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2011.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidts T, Dobler D, Nissing C, Runkel F. Influence of hydrophilic surfactants on the properties of multiple W/O/W emulsions. Journal of Colloid and Interface Science. 2009;338:184–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2009.06.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidts T, Dobler D, Schlupp P, Nissing C, Garn H, Runkel F. Development of multiple W/O/W emulsions as dermal carrier system for oligonucleotides: effect of additives on emulsion stability. International Journal of Pharmaceutics. 2010;398:107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi A, Wang J, Guo R, Feng X, Ge Y, Liu H, Agyei D, Wang Q. Improving resveratrol bioavailability using water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsion: physicochemical stability, in vitro digestion resistivity and transport properties. Journal of Functional Foods. 2021;87:104717. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2021.104717. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Souilem S, Kobayashi I, Neves MA, Jlaiel L, Isoda H, Sayadi S, Nakajima M. Interfacial characteristics and microchannel emulsification of oleuropein-containing triglyceride oil-water systems. Food Research International. 2014;62:467–475. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2014.03.049. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walstra P. Principles of emulsion formation. Chemical Engineering Science. 1993;48:333–349. doi: 10.1016/0009-2509(93)80021-H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Shi A, Agyei D, Wang Q. Formulation of water-in-oil-in-water (W/O/W) emulsions containing trans-resveratrol. RSC Advances. 2017;7:35917–35927. doi: 10.1039/C7RA05945K. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Waraho T, McClements DJ, Decker EA. Impact of free fatty acid concentration and structure on lipid oxidation in oil-in-water emulsions. Food Chemistry. 2011;129:854–859. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2011.05.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao J, Lu X, Haung Q. Double emulsion derived from kafirin nanoparticles stabilized: pickering emulsion: fabrication, microstructure, stability and in vitro digestion profile. Food Hydrocolloids. 2017;62:230–238. doi: 10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.08.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yildirim M, Sunmu G, Sahin S. The effects of emulsifier type, phase ratio, and homogenization methods on stability of the double emulsion. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2017 doi: 10.1080/01932691.2016.1201768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon SH, Choi EE, Oh CH, Song YY, Jeong MY, Hong ST, Jang PS, Lee JH, Kim HJ. In: Food Lipids, pp. 247–297. Hong ST (ed). Soohaksa, Seoul, Korea (2015)

- Yuan X, Liu X, McClements DJ, Cao Y, Xiao H. Enhancement of phytochemical bioaccessibility from plant-based foods using excipient emulsions: impact of lipid type on carotenoid solubilization from spinach. Food and Function. 2018;9:4352–4365. doi: 10.1039/C8FO01118D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zhang Z, Zhang H, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Influence of lipid type on gastrointestinal fate of oil-in-water emulsions: in vitro digestion study. International Food Research. 2015;75:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zhang Z, Zou L, Xiao H, Zhang G, Decker EA, McClements DJ. Enhancing nutraceutical bioavailability from raw and cooked vegetables using excipient emulsions: influence of lipid type on carotenoid bioaccessibility from carrots. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2015;63:10508–10517. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.5b04691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang R, Zhang Z, Kumosani T, Khoja S, Abualnaja KO, McClements DJ. Encapsulation of β-carotene in nanoemulsion-based delivery systems formed by spontaneous emulsification: influence of lipid composition on stability and bioaccessibility. Food Biophysics. 2016;11:154–164. doi: 10.1007/s11483-016-9426-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Q, Feng L, Saito M, Yin L. Preparation and characterization of W/O/W double emulsions containing MgCl2. Journal of Dispersion Science and Technology. 2018;39:349–355. doi: 10.1080/01932691.2017.1318076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]