Abstract

Aims

We investigated the implementation of new guidelines in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients in a large real-world patient population in the metropolitan area of Berlin (Germany) over a 20-year period.

Methods

From January 2000 to December 2019, a total of 25 792 patients were admitted with STEMI to one of the 34 member hospitals of the Berlin-Brandenburg Myocardial Infarction Registry (B2HIR) and were stratified for sex and age < 75 and ≥ 75 years.

Results

The median age of women was 72 years (IQR 61–81) compared to 61 years in men (IQR 51–71). PCI treatment as a standard of care was implemented in men earlier than in women across all age groups. It took two years from the 2017 class IA ESC STEMI guideline recommendation to prefer the radial access route rather than femoral until > 60% of patients were treated accordingly. In 2019, less than 60% of elderly women were treated via a radial access. While the majority of patients < 75 years already received ticagrelor or prasugrel as antiplatelet agent in the year of the class IA ESC STEMI guideline recommendation in 2012, men ≥ 75 years lagged two years and women ≥ 75 three years behind. Amongst the elderly, in-hospital mortality was 22.6% (737) for women and 17.3% (523) for men (p < 0.001). In patients < 75 years fatal outcome was less likely with 7.2% (305) in women and 5.8% (833) in men (p < 0.001). After adjustment for confounding variables, female sex was an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients ≥ 75 years (OR 1.37, 95% CI 1.12–1.68, p = 0.002), but not in patients < 75 years (p = 0.076).

Conclusion

In-hospital mortality differs considerably by age and sex and remains highest in elderly patients and in particular in elderly females. In these patient groups, guideline recommended therapies were implemented with a significant delay.

Graphical abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00392-023-02165-9.

Keywords: ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), Women, Myocardial infarction, Coronary artery disease, Percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI)

Introduction

ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is associated with increased morbidity and mortality [1]. Nonetheless, several innovations and consecutive European Society of Cardiology (ESC) guideline updates were accompanied by a substantial reduction of in-hospital mortality that remains in the range from 4 to 12% in different ESC member countries in recent years [2]. Undoubtly, the main drivers for this improvement were the wide-spread use of revascularization therapy, primary percutaneous coronary intervention as a standard of care and modern antithrombotic agents [1, 3, 4].

Interestingly, the incidence of STEMI declined over the past three decades [5–7]. The main reasons for this phenomenon may be the substantial decrease in smoking prevalence, the wide spread use of statins and an improved awareness to monitor and treat hypertension as major cardiovascular risk factor [8, 9]. Despite these advances, STEMI remains a leading cause of death in western countries. [10, 11]

While the current ESC recommendations guide treatment in the majority of cases, several patient subsets need special consideration [12]. In particular, in elderly and female patients, guideline implementation might be delayed [13, 14].

Previous studies demonstrated higher in-hospital mortality and an increased risk of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) in females presenting with STEMI [15]. Elderly patients are more likely to receive palliation or conservative treatment for STEMI [16, 17]. Whether these disparities are largely due to the older age and higher burden of comorbidities of female STEMI patients remains unclear [18]. The most recent 2021 guidelines on Coronary Artery Revascularization, by the American College of Cardiology highlight the importance of continued vigilance against gender biases in the treatment of cardiovascular disease [19].

The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of ESC guidelines implementation on outcomes in different patient subgroups in a large prospective registry over the past two decades.

Methods

Data collection and patient population

The Berlin-Brandenburg myocardial infarction registry (B2HIR) was founded in 1999 to assess and improve the quality of care in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome (ACS) at the participating member hospitals in Berlin and Brandenburg, Germany [20]. Details of the organization of the registry are described elsewhere [21]. The B2HIR prospectively collects data of patients with a type I myocardial infarction who are admitted within 24 h after the onset of symptoms [22]. In the present study, only patients presenting with STEMI according to the definition of the ESC guidelines were included [12].

The collected parameters were updated on a regular basis to reflect the continuous changes in the ESC guidelines and daily clinical practice. In the present study, 25,792 patients admitted to one of the member hospitals of the B2HIR between January 2000 and December 2019 were included in the analysis. Patients were stratified for sex and age < 75 and ≥ 75 years. Patients ≥ 75 years were defined as elderly as a majority of trials use 75 years as a cut-off value and mortality and prevalence of comorbidities sharply rise thereafter [12]. The member hospitals were responsible for data entry. Independent monitoring is performed and source-data are verified for an average of 7.5% of the registered patients. A data-plausibility check is performed annually for all member hospitals.

Changes in the guidelines of the ESC in the time period of year 2000–2019

Over the study period, the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) issued four consecutive guideline updates for the diagnosis and therapy of STEMI in the years 2003, 2008, 2012 and 2017 [12, 23–25]. Figure 1 summarizes the major changes over the past 20 years.

Fig. 1.

Major changes in recommendations for the treatment of STEMI in the ESC guidelines since 2003 ESC STEMI guideline [12, 24, 25, 47]. PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, DES drug-eluting stent, BMS bare-metal stent, FMC first medical contact

Outcome measures and endpoint definitions

The primary outcome measure of the present analysis was in-hospital mortality. Further outcome measures included a conservative versus an invasive approach, PCI and CABG rates, door-to-balloon time (DTB), the use of DES, radial access route for PCI, use of clopidogrel, ticagrelor and prasugrel as antiplatelet agents and MACE rates. MACE was defined as stroke, re-infarction, re-intervention, intervention-related bleeding (hemodynamically compromising or requiring transfusion), cardiopulmonary resuscitation, new onset of shock or need for mechanical ventilation and all-cause mortality. Major bleeding was defined as a hemodynamically compromising or requiring transfusion. Prehospital delay was defined as the time from symptom onset until hospital admission. Left ventricular ejection fraction as measured at time of admission using transthoracic echocardiogram. Successful guideline implementation as a standard of care of a new therapy (new antithrombotic drugs ticagrelor/prasugrel, drug eluting stents) or technique (radial access route) was arbitrarily assumed, if the innovation was applied in > 60% of patients per year.

Statistics

Nominal data are presented as percentages and absolute numbers (parentheses), while continuous values are shown as median and interquartile range (1st and 3rd quartile). The Chi-square test was used to assess significant relationship between categorical variables, the Mann–Whitney U test was used to assess significant difference of continuous variables. Patients with missing values were excluded from the respective analysis.

In-hospital mortality of patients stratified by age (< 75 and ≥ 75 years) was analysed using a logistic regression model adjusted for the following variables: age, female sex, KILLIP IV or shock at admission, known heart failure, chronic kidney injury, smoking, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, prior myocardial infarction, prior PCI and atrial fibrillation at admission. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated.

The significance level was set to p < 0.05. Due to the exploratory nature of the analyses, no correction for multiple comparisons was performed. All analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, USA).

Ethics

The registry is approved by the Berlin Board for Data Privacy Monitoring. A positive ethics votum was granted by the Ärztekammer Berlin und Brandenburg. The study protocol confirms to the ethical guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki [26].

Results

Baseline characteristics

A total of 25,659 patients were included into the study after exlusion of 260 patients with missing data on age and sex. Patients < 75 years were predominantly male (77.3%) while 51.8% of patients ≥ 75 years were female. The median age of men was 61 years (IQR 53–71) and 72 for women (IQR 61–81). The median age did not change significantly over the study period. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics of male and female patients stratified by age. The median length of hospital stay declined from 11 days (IQR 16–8) for men and 14 days (IQR 19–10) for women to 5 days (IQR 7–3) for men and 6 days (IQR 8–4) for women from 2000 to 2019 (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics for men and women stratified for age

| < 75 years | ≥ 75 years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | p | Men | Women | p | |||||

| N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | N | (%) | |||

| Median age (IQR) | 14,845 | 58 (66–51) | 4363 | 62 (69–54) | < 0.001 | 3108 | 79 (83–77) | 3343 | 82 (68–78) | < 0.001 |

| BMI < 18.5 | 130 | 1.0 | 95 | 2.6 | < 0.001 | 43 | 1.7 | 109 | 4.2 | < 0.001 |

| 18.5 to < 25 | 3616 | 29.1 | 1222 | 33.9 | < 0.001 | 956 | 38.0 | 1065 | 41.2 | < 0.001 |

| 25 to < 30 | 5799 | 46.7 | 1298 | 36.0 | < 0.001 | 1156 | 46.0 | 973 | 37.6 | < 0.001 |

| ≥ 30 | 2823 | 22.7 | 974 | 27.0 | < 0.001 | 342 | 13.6 | 424 | 16.4 | < 0.001 |

| LVEF > 50% | 3544 | 41.1 | 1059 | 42.5 | < 0.018 | 478 | 27.3 | 531 | 31.4 | < 0.013 |

| 41–50% | 2034 | 23.6 | 532 | 21.3 | 383 | 21.8 | 341 | 20.2 | ||

| 31–40% | 906 | 10.5 | 297 | 11.9 | 253 | 14.4 | 251 | 14.8 | ||

| < 30% | 609 | 7.1 | 148 | 5.9 | 252 | 14.4 | 189 | 11.2 | ||

| Initial HR > 100 bpm | 1924 | 14.6 | 555 | 14.5 | 0.821 | 460 | 16.9 | 597 | 20.8 | < 0.001 |

| Smoker | 8201 | 60.1 | 2167 | 53.2 | < 0.001 | 478 | 17.9 | 321 | 11.1 | 0.014 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2933 | 20.6 | 1060 | 25.2 | < 0.001 | 964 | 32.7 | 1135 | 35.7 | 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 8911 | 63.4 | 2910 | 69.5 | < 0.001 | 2394 | 81.0 | 2706 | 84.4 | 0.005 |

| Hypercholesterinaemia | 6459 | 48.2 | 1963 | 49.6 | 0.122 | 1284 | 47.1 | 1233 | 43.3 | < 0.001 |

| History of MI | 2046 | 14.4 | 436 | 10.5 | < 0.001 | 699 | 23.8 | 553 | 17.7 | < 0.001 |

| Pior PCI | 2066 | 15.2 | 412 | 10.4 | < 0.001 | 674 | 23.8 | 417 | 14.3 | < 0.001 |

| Prior CABG | 412 | 3.0 | 72 | 1.8 | < 0.001 | 229 | 8.0 | 99 | 3.3 | < 0.001 |

| History of stroke | 354 | 3.5 | 107 | 3.7 | 0.603 | 194 | 8.9 | 193 | 9.7 | 0.399 |

| Chronic HF | 1316 | 9.3 | 412 | 9.9 | 0.245 | 675 | 23.3 | 740 | 23.8 | 0.615 |

| Chronic KI | 981 | 6.9 | 317 | 7.6 | 0.138 | 805 | 27.4 | 815 | 25.8 | 0.154 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 571 | 4.0 | 169 | 4.0 | < 0.001 | 415 | 13.7 | 455 | 14.0 | 0.79 |

| Pacemaker | 78 | 0.6 | 35 | 0.9 | 0.037 | 61 | 2.2 | 48 | 1.7 | 0.165 |

| KILLIP IV/shock | 1342 | 10.1 | 385 | 10.0 | 0.073 | 389 | 13.8 | 359 | 12.3 | 0.86 |

BMI body mass index, HR heart rate, MI myocardial infarctiont, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, CABG coronary artery bypass graft, HF heart failure, KI kidney injury, LVEF left ventricular ejection fraction (at admission)

Prehospital delay and door-to-balloon time

Women, especially the elderly, presented with a significant delay to the emergency department after onset of ischaemic symptoms, if compared to male patients over the entire study period. In patients < 75 years, the median prehospital delay, defined as time from onset of pain to hospital admission, for men was 110 min. (IQR 66–242) compared to 122 min. for women (IQR 73–275, p < 0.001). This difference was even more pronounced in elderly patients ≥ 75 years with a median prehospital delay of 128 min. in men (IQR 75–291) compared to 158 min. (IQR 83–360) in women (p < 0.001). There was a marked improvement from year 2000 if compared to 2019 in the median prehospital delay times from 120 min. (IQR 76–240) to 102 min. (IQR 67–205) in men (p < 0.001) and from 150 min. (IQR 72–395) to 118 min. (IQR 76–250) in women (p < 0.001). However, time from symptom onset until hospital admission remains significantly higher in women in the year 2019 (p < 0.001).

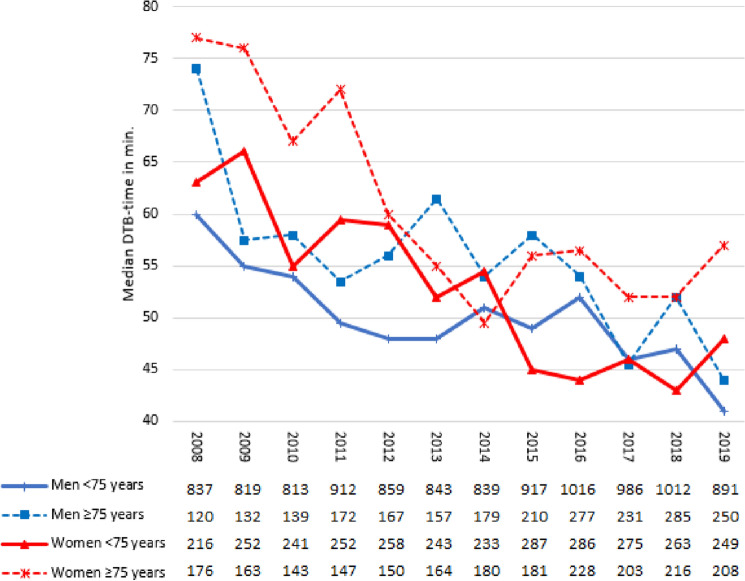

The DTB-times (Fig. 2) decreased significantly from 62.5 min (IQR 30–115) in men and 67.0 min (IQR 40–152) in women in 2008 to 41 min (IQR 21–71) in men and to 49.5 min (IQR 27–96) in women in 2019 (p < 0.001 for both). In patients ≥ 75 years, these times decreased from 74 min (IQR 31–169) to 44 min (IQR 25–75) in men and from 77 min (IQR 49–191) to 57 min (IQR 27–133) in women (p < 0.001 for both). Until the end of the study period in 2019, the median DTB-time remained significantly longer in women compared to men, in particular in the elderly population over ≥ 75 years (p < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Median DTB in STEMI patients from 2008–2019 stratified for sex and age

PCI rates and revascularization of non-culprit vessels during the index hospitalisation

Men < 75 years were more frequently treated with PCI compared to elderly women (89.9% (13,329) vs. 70.9% (2360), p < 0.001) over the entire study period (refer to Fig. 3). However, intervention rates increased continuously over the course of time. In the year 2000, 44.4% (362) of male and 29.4% (133) of female patients underwent PCI treatment (p < 0.001). In the year 2019, 97.9% (872) of male patients < 75 years were treated with PCI compared to 96.4% (240) of female patients < 75 years (p = 0.182). In the subset of patients ≥ 75 years, 92.0% (230) of male and 90.4% (188)of female patients received PCI treatment in the year 2019 (p = 0.542). PCI treatment was implemented as a standard of care (i.e., > 60% of patients) in men in 2001 compared to 2003 in women < 75 years. In the elderly, this threshold was only surpassed in the year 2004 for men and 2007 for women.

Fig. 3.

STEMI patients receiving PCI-therapy from 2000–2019 stratified for sex and age

In 2018, 13.8% (37) of men (missing = 3) and 14.4% (28) of women above the age of 75 years and 11.8% (116) of men (missing = 3) vs. 8.4% (21) of women (missing = 1) below 75 years underwent a second PCI to a non-culprit vessel during the index hospitalization (p < 0.001).

In 2019 21.8% (40) of men (missing = 3) and 17.6% (33) of women above the age of 75 years and 10.4% (91) of men vs. 13.7% (33) of women below 75 years had a second intervention to a non-culprit vessel during the hospitalization (p < 0.001).

Use of DES

DES were implemented as a standard of care in the majority of patients (> 60%) even before the class I recommendation of the 2017 STEMI guideline was published. In the first year of documentation of DES-use, less than < 60% of elderly men and women received DES while in patient group < 75 years, DES were already implemented as the standard of care. In the following year, > 60% of all patients received DES during PCI. In the year 2014, 92.6% (891) of male and 89.5% (342) of female patients (p = 0.284) received DES during PCI. In the following year 2015, no significant difference in DES-use in the different patient subsets was noted. From 2017 onwards, as DES were considered the new gold standard, the use of bare-metal or drug-eluting stents was no longer documented in the database.

Antiplatelet therapy

Ticagrelor was increasingly used as an antiplatelet agent from 2010 onwards. Before the 2012 STEMI guideline, only 3.2% (27) of male and 2.4% (10) of female patients received ticagrelor in the year 2010. In 2019, there was no significant difference in ticagrelor use with 36.8% (468) of male vs. 39.8% (202) of female patients (p = 0.261). There was no significant difference in elderly patients. Prasugrel use is generally not recommended in patients ≥ 75 years or in patients with low body weight (< 60 kg). Consequently, prasugrel was less often used in female patients. In patients < 75 years, there was a significant difference in the use of prasugrel between men and women (57.3% (4416) vs. 53.3% (1154), p < 0.001). Across the entire study period, 50.9% (2296) of female patients received either ticagrelor or prasugrel compared to 55.3% (6372) of male patients (p < 0.001). In patients ≥ 75 years, clopidogrel remained the preferred antiplatelet agent for both men and women. 44.1% (774) of female patients received either ticagrelor or prasurel compared to 49.3% (934) of the male patients (p = 0.002) in this age group. However, after the class I recommendation in the 2012 STEMI guideline, > 60% of patients received either prasugrel or tricagrelor as an antiplatelet agent from the following year onwards.

Radial access route for PCI

In 2011, radial access was used in 41.2% (336) of male and 35% (99) of female patients during PCI (p < 0.001) compared to 72.1% (796) male and 60.1% (266) female patients in 2019 (p < 0.001, Fig. 4). Notably, the radial access route was less common in elderly patients. In this subgroup, there was a significant difference in radial vs. femoral access between men and women (73.4% (168) vs. 57.4% (109) in 2019, p < 0.001). It took two years from the IA ESC STEMI guideline recommendation for preferred radial access until > 60% of patients were treated accordingly. In the year 2019, radial access was used in > 60% of all PCI-patients (Fig. 4). Only in the subset of patients < 75 years > 60% of men were treated radially in the year 2018 (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The radial access route for PCI from 2011 to 2019 stratified for sex and age

MACE rates were significantly lower, if the transradial approach was used, if compared to the transfemoral route. In men < 75 years, MACE rates were significantly higher for the transfemoral access route with 15.3% (510) vs 5.6% (224), p < 0.001) compared to the transradial approach with similar results in women (16.9% (180) vs. 5.5% (55), p < 0.001). In elderly patients, 26% (204) of men treated via a transfemoral approach had an event, if compared to 12.8% (107) in the transradial approach (p < 0.001). In elderly women, this finding was even more pronounced the the transfemoral group with 29.6% (225) compared to 15.9% (92) in the transradial approach (p < 0.001).

Major adverse cardiovascular events

Irrespective of age, in men with a BMI < 30 kg/m2, significantly more major bleeding events—defined as need for blood transfusion or leading to haemodynamic compromise—were observed [0.8% (78)], compared to obese men with a BMI > 30 kg/m2 (0.4% (10), p = 0.019). In women, there was a comparable difference between non-obese and obese patients that did, however, not reach statistical significance [1.6% (62) vs. 1.3% (16), p = 0.494]. However, bleeding events that did not trigger blood transfusions or significant haemodynamic compromise were not recorded in the present database.

MACE rates were significantly lower, if the transradial approach was used, if compared to the transfemoral route. In men < 75 years, MACE rates were significantly higher for the transfemoral access route with [15.3% (510) vs. 5.6% (224), p < 0.001] compared to the transradial approach with similar results in women [16.9% (180) vs. 5.5% (55), p < 0.001]. In elderly patients, 26% (204) of men treated via a transfemoral approach had an event, if compared to 12.8% (107) in the transradial approach (p < 0.001). In elderly women, this finding was even more pronounced the transfemoral group with 29.6% (225) compard to 15.9% (92) in the transradial approach (p < 0.001).

Across the entire patient population, the incidence of MACE declined from 16.8% (150) in 2008 to 12.7% (200) in 2019 (p < 0.001). In the subset of female patients ≥ 75 years, MACE rates were the highest with 26.4% (517) compared to 20.7% (441) in men ≥ 75 years. In patients < 75 years, MACE rates were lower with no statistically significant difference between men [10.3% (1030))] and women [11.6% (332), p = 0.053, refer to Table 2].

Table 2.

MACE stratified for age and sex

| < 75 years | > = 75 years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | p | Men | Women | p | |||||

| N = 9962 | (%) | N = 2861 | (%) | N = 2134 | (%) | N = 1957 | (%) | |||

| Shock | 154 | 1.5 | 28 | 0.9 | 0.025 | 52 | 2.3 | 76 | 3.7 | 0.008 |

| Intubation | 150 | 1.4 | 50 | 1.7 | 0.345 | 51 | 2.3 | 66 | 3.2 | 0.061 |

| Reanimation | 345 | 3.3 | 108 | 3.6 | 0.407 | 116 | 5.2 | 123 | 6.0 | 0.253 |

| Reinfarction | 192 | 1.3 | 69 | 1.6 | 0.007 | 58 | 1.9 | 90 | 2.8 | < 0.001 |

| Stroke | 91 | 0.6 | 37 | 0.9 | 0.004 | 35 | 1.2 | 40 | 1.2 | 0.735 |

| Reintervention due to ischaemia | 237 | 1.9 | 69 | 1.9 | 0.964 | 52 | 2.0 | 41 | 1.6 | 0.275 |

| Major bleeding | 77 | 0.6 | 43 | 1.2 | < 0.001 | 30 | 1.1 | 54 | 2.1 | 0.007 |

| In-hospital mortality | 833 | 5.8 | 305 | 7.2 | < 0.001 | 523 | 17.3 | 737 | 22.6 | < 0.001 |

In-hospital mortality

In-hospital mortality decreased significantly over the study period from 12.8% (157) in 2000 to 9.2% (147) in 2019 (p < 0.001). Women had higher rates of in-hospital mortality in all age groups. Mortality declined from 24% (31) in the year 2000 to 15.2% (38) in the year 2019 (p = 0.035) in men over ≥ 75 years. In female patients ≥ 75 years, mortality rates remain at the highest levels of all patient subgroups [25.1% (59) in 2000 vs. 23.6% (49) in 2019, p = 0.705]. In patients < 75 years, the in-hospital mortality decreased over the study period and remained on a substantially lower level than in elderly patients. After adjustment for confounding variables, female sex was associated with an increased in-hospital mortality with an OR of 1.37 (95% CI 1.12–1.68, p = 0.002) in patients ≥ 75 years (Table 3). In patients < 75 years, female sex was not a significant predictor of in-hospital mortality (p = 0.076).

Table 3.

Logistic regression for in-hospital mortality stratified for age

| < 75 years (n = 13,256) | ≥ 75 years (n = 3994) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p | OR | 95% CI | p | |||

| Female sex | 1.229 | 0.98 | 1.54 | 0.076 | 1.370 | 1.12 | 1.68 | 0.002 |

| Age, y | 1.051 | 1.04 | 1.06 | < 0.001 | 1.054 | 1.04 | 1.07 | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1.721 | 1.37 | 2.16 | < 0.001 | 1.446 | 1.18 | 1.78 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 0.683 | 0.55 | 0.86 | 0.001 | 0.736 | 0.57 | 0.95 | 0.021 |

| History of HF | 1.254 | 0.96 | 1.65 | 0.102 | 1.480 | 1.18 | 1.86 | < 0.001 |

| Chronic KI | 2.084 | 1.57 | 2.77 | < 0.001 | 1.554 | 1.25 | 1.93 | < 0.001 |

| Current smoker | 1.221 | 0.99 | 1.51 | 0.066 | 0.810 | 0.60 | 1.10 | 0.178 |

| KILLIPIV or shock | 17.434 | 14.17 | 21.45 | < 0.001 | 10.272 | 8.09 | 13.04 | < 0.001 |

| Prior MI | 1.184 | 0.81 | 1.74 | 0.387 | 1.167 | 0.86 | 1.58 | 0.316 |

| Prior PCI | 1.064 | 0.74 | 1.54 | 0.741 | 0.847 | 0.62 | 1.15 | 0.292 |

| Afib at admission | 1.245 | 0.87 | 1.79 | 0.237 | 1.198 | 0.92 | 1.56 | 0.184 |

MI myocardial infarctiont, PCI percutaneous coronary intervention, HF heart failure, KI kidney injury, Afib atrial fibrillation

Discussion

Our study illustrates a continuous improvement in the treatment of STEMI patients over the past 20 years. Overall, in-hospital mortality rates declined from 12.8% in 2000 to 9.2% in 2019. It can be hypothesized that the the main drivers for this development were related to the increasing use of drug eluting stents, radial access, new antiplatelet therapies and the continuous reduction of the door-to-balloon-time [27–29]. Moreover, MACE rates decreased, possibly through the growing experience with the use of radial access route [30].

In-hospital mortality remained at a relatively high level in the analyzed real-world population. This finding may be explained by the high median age of female patients (72 years) and the high proportion of patients presenting with Killip class IV or cardiogenic shock (10.8%). Registries with comparable patient characteristics reported similar outcomes [31, 32].

Innovative medical and invasive therapies were continuously incorporated into ESC guideline updates. Nonetheless, the time delay to implement innovations into daily clinical practice varied widely. One year after the publication of the first landmark trial, radial access was rewarded a class IIA recommendation. Another five years later it received a class IA ESC STEMI guideline recommendation [12, 24, 33]. Finally, it took another two years until > 60% of patients were treated accordingly. We hypothesize that the switch from femoral to radial access as the default strategy was more challenging for the individual operator with a significant learning curve as compared to the use of DES or the change in antiplatelet drugs [34, 35]. This may be the main reason for the significant delay in using radial access in the majority of patients. In light of convincing evidence and the significant downsides of bare metal stents, DES were rapidly implemented into daily clinical practice a long time before the guidelines strongly supported their use (Table 4).

Table 4.

Time from landmark-trial to Class IIA and Class IA recommendation in the ESC STEMI guidelines

| DES | Radial access | Modern antiplateled therapy | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st landmark trial | TYPHOON (2006) | RIVAL (2011) | PLATO (2009) |

| Class IIA recommendation | 2012 ESC | 2012 ESC | n.a |

| Class IA recommendation | 2017 ESC | 2017 ESC | 2012 |

| > 60% of patients receiving guideline-based therapya | 2012 | 2019 | 2012 |

aeither Ticagrelor or Prasugrel considered as guideline based antiplatetelet agents in patients without oral anticoagulation

In contrast, newer antiplatelet drugs, like ticagrelor or prasugrel, were rapidly embraced by the interventional community as the preferred treatment option. Only three years after publication of the first landmark trial the new platelet inhibitors received a class IA recommendation [12, 24, 36]. In the same year, these drugs were already the preferred treatment option in the majority of patients in the present analysis (Table 4).

Notably, all of these guideline changes were first implemented in younger —in particular male—patients. In elderly and female patients, all of the above mentioned innovations were introduced into daily clinical practice with a significant delay.

Compared to men, women presented with STEMI at an older age. In line with previously published data, we demonstrated that female STEMI patients are less likely to undergo revascularization in the presence of co-morbidities [37, 38]. The time delay from symptom onset to hospital admission as well as the door-to-balloon time (DTB) were significantly longer in women—and in particular in elderly females. Notably, the DTB time remained significantly longer in women than in men over the study period.

This observation may be associated to the poor in-hospital mortality in these patient groups (17.3% in men vs. 23.6% in women ≥ 75 years, p < 0.001). Similar results were published previously, demonstrating a two-fold in-hospital mortality in women as compared to men [39, 40]. Another possible explanation for the mortality difference might be an atypical presentation of females and older individuals that may postpone diagnosis and consequently revascularization. [31, 40, 41].

Similarly, radial access was used less frequently in women although the MATRIX trial showed greater benefit for PCI via the radial access route in women relative to men in terms of bleeding complications and even mortality [42].

Female sex appeared as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality in patients ≥ 75 years. However, this finding may mainly be driven by an unfavorable risk profile along with age and baseline comorbidities [18, 43, 44]. Previous studies reported conflicting findings on the role of female sex as an independent predictor of in-hospital mortality which warrants further investigation of female-specific cardiovascular risk factors [40, 45, 46].

The present study is inherent to several limitations. Though data were collected prospectively, the data analysis was not pre-specified and therefore this analysis is retrospective in nature. While precise data on the course of disease were recorded during the index hospitalization, no follow-up data after hospital discharge were available. Due to data privacy concerns it was not possible to collect follow-up data on outcomes nor data on further coronary interventions over time. Moreover, parameters to describe the detailed coronary anatomy were not gathered in the present database. Data were collected exclusively in hospitals based in the metropolitan area of Berlin, Germany. The conclusions drawn by the presented data might, therefore, be only partly applicable to rural areas.

Conclusion

Over the past 20 years, marked improvements in the treatment of STEMI were achieved. Importantly, in elderly patients and in particular in elderly females, new ESC guidelines were implemented into daily clinical practice with a significant time delay. Innovations that require a specific technical skillset with a consecutive learning curve need more time to gain popularity amongst operators. Future guidelines should, therefore, highlight the benefit of new recommendations in these traditionally undertreated patient subsets.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all member hospitals participating in the B2HIR registry.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL. The B2HIR is funded by unrestricted grants of the participating hospitals.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to German data protection regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Townsend N, Wilson L, Bhatnagar P, Wickramasinghe K, Rayner M, Nichols M. Cardiovascular disease in Europe: epidemiological update 2016. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(42):3232–3245. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehw334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kristensen SD, Laut KG, Fajadet J, Kaifoszova Z, Kala P, Di Mario C, et al. Reperfusion therapy for ST elevation acute myocardial infarction 2010/2011: current status in 37 ESC countries. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(29):1957–1970. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gale CP, Allan V, Cattle BA, Hall AS, West RM, Timmis A, et al. Trends in hospital treatments, including revascularisation, following acute myocardial infarction, 2003–2010: a multilevel and relative survival analysis for the national institute for cardiovascular outcomes research (NICOR) Heart. 2014;100(7):582–589. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2013-304517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson ED, Shah BR, Parsons L, Pollack CV, French WJ, Canto JG, et al. Trends in quality of care for patients with acute myocardial infarction in the National Registry of Myocardial Infarction from 1990 to 2006. Am Heart J [Internet] 2008;156(6):1045–1055. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yeh RW, Sidney S, Chandra M, Sorel M, Selby JV, Go AS. Population trends in the incidence and outcomes of acute myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(23):2155–2165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0908610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McManus DD, Gore J, Yarzebski J, Spencer F, Lessard D, Goldberg RJ. Recent trends in the incidence, treatment, and outcomes of patients with STEMI and NSTEMI. Am J Med. 2011;124(1):40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2010.07.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sugiyama T, Hasegawa K, Kobayashi Y, Takahashi O, Fukui T, Tsugawa Y. Differential time trends of outcomes and costs of care for acute myocardial infarction hospitalizations by ST elevation and type of intervention in the United States, 2001–2011. J Am Heart Assoc. 2015;4(3):e001445. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.114.001445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nabel EG, Braunwald E. A tale of coronary artery disease and myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(1):54–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1112570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jousilahti P, Laatikainen T, Peltonen M, Borodulin K, Männistö S, Jula A, et al. Primary prevention and risk factor reduction in coronary heart disease mortality among working aged men and women in eastern Finland over 40 years: population based observational study. BMJ. 2016;352:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Menon V, Aggarwal B (2014) Acute myocardial infarction. Cardiol Intensive Board Rev Third Ed. 54–69

- 11.Puymirat E, Simon T, Cayla G, Cottin Y, Elbaz M, Coste P, et al. Acute myocardial infarction: changes in patient characteristics, management, and 6-month outcomes over a period of 20 years in the FAST-MI program (French registry of acute ST-elevation or non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction) 1995 to 2015. Circulation. 2017;136(20):1908–1919. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, Antunes MJ, Bucciarelli-Ducci C, Bueno H, et al. 2017 ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2018;39(2):119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chichareon P, Modolo R, Kerkmeijer L, Tomaniak M, Kogame N, Takahashi K, et al. Association of sex with outcomes in patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention: a subgroup analysis of the GLOBAL LEADERS randomized clinical trial. JAMA Cardiol. 2020;5(1):21–29. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2019.4296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Phan DQ, Rostomian AH, Schweis F, Chung J, Lin B, Zadegan R, et al. Revascularization versus medical therapy in patients aged 80 years and older with acute myocardial infarction. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2020;68(11):2525–2533. doi: 10.1111/jgs.16747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Porter A, Paradkar A, Goldenberg I, Shlomo N, Cohen T, Kornowski R et al (2020) Temporal trends analysis of the characteristics, management, and outcomes of women with acute coronary syndrome (ACS): ACS Israeli survey registry 2000–2016. J Am Heart Assoc 9(1):e014721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Helft G, Georges JL, Mouranche X, Loyeau A, Spaulding C, Caussin C, et al. Outcomes of primary percutaneous coronary interventions in nonagenarians with acute myocardial infarction. Int J Cardiol [Internet] 2015;192:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.04.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alexander KP, Newby LK, Armstrong PW, Cannon CP, Gibler WB, Rich MW, et al. Acute coronary care in the elderly, part II: ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association council on clinical cardiology. Circulation. 2007;115(19):2570–2589. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.182616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stehli J, Martin C, Brennan A, Dinh DT, Lefkovits J, Zaman S. Sex differences persist in time to presentation, revascularization, and mortality in myocardial infarction treated with percutaneous coronary intervention. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(10):1–9. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lawton JS, Tamis-Holland JE, Bangalore S, Bates ER, Beckie TM, Bischoff JM, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA/SCAI guideline for coronary artery revascularization: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation [Internet] 2021;0(0):CIR.0000000000001038. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000001038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berlin-Brandenburg Myocardial Infarction Registry [Internet]. https://herzinfarktregister.de/ueber-den-verein/. Accessed 10 April 2022

- 21.Riehle L, Maier B, Behrens S, Bruch L, Schoeller R, Schühlen H, et al. Changes in treatment for NSTEMI in women and the elderly over the past 16 years in a large real-world population. Int J Cardiol. 2020;316:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2020.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thygesen K, Alpert JS, Jaffe AS, Chaitman BR, Bax JJ, Morrow DA, et al. Fourth universal definition of myocardial infarction (2018) Eur Heart J. 2019;40(3):237–269. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehy462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van De Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Steg PG, James SK, Atar D, Badano LP, Lundqvist CB, Borger MA, et al. ESC guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2012;33(20):2569–2619. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vande Werf F, Ardissino D, Betriu A, Cokkinos DV, Falk E, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:28–66. doi: 10.1016/S0195-668X(02)00618-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kong H, West S. WMA Declaration of Helsinki—ethical principles. World Med Assoc. 1964;2013:29–32. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shishehbor MH, Goel SS, Kapadia SR, Bhatt DL, Kelly P, Raymond RE, et al. Long-term impact of drug-eluting stents versus bare-metal stents on all-cause mortality. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet] 2008;52(13):1041–1048. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.06.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andò G, Capodanno D. Radial access reduces mortality in patients with acute coronary syndromes results from an updated trial sequential analysis of randomized trials. JACC Cardiovasc Interv [Internet] 2016;9(7):660–670. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McNamara RL, Wang Y, Herrin J, Curtis JP, Bradley EH, Magid DJ, et al. Effect of door-to-balloon time on mortality in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol [Internet] 2006;47(11):2180–2186. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.12.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campelo-Parada F, Carrie D, Bartorelli AL, Namiki A, Hovasse T, Kimura T, et al. Radial versus femoral approach for percutaneous coronary intervention: MACE outcomes at long-term follow-up. J Invasive Cardiol. 2018;30(7):262–268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Piackova E, Jäger B, Farhan S, Christ G, Schreiber W, Weidinger F, et al. Gender differences in short- and long-term mortality in the Vienna STEMI registry. Int J Cardiol [Internet] 2017;244:303–308. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2017.05.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martins E, Magne J, Pradel V, Faugeras G, Bosle S, Cailloce D, et al. The mortality rates in registries of patients with STEMI are highly affected by inclusion criteria and population characteristics. Acta Cardiol [Internet] 2021;76(5):504–512. doi: 10.1080/00015385.2020.1848970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jolly SS, Yusuf S, Cairns J, Niemelä K, Xavier D, Widimsky P, et al. Radial versus femoral access for coronary angiography and intervention in patients with acute coronary syndromes (RIVAL): a randomised, parallel group, multicentre trial. Lancet [Internet] 2011;377(9775):1409–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60404-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Spaulding C, Lefèvre T, Funck F, Thébault B, Chauveau M, Ben Hamda K, et al. Left radial approach for coronary angiography: results of a prospective study. Cathet Cardiovasc Diagn. 1996;39(4):365–370. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0304(199612)39:4<365::AID-CCD8>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roh JW, Kim Y, Lee OH, Im E, Cho DK, Choi D, et al. The learning curve of the distal radial access for coronary intervention. Sci Rep [Internet] 2021;11(1):1–7. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-92742-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Husted S, James S, Becker RC, Horrow J, Katus H, Storey RF, et al. Ticagrelor versus clopidogrel in elderly patients with acute coronary syndromes: a substudy from the prospective randomized PLATelet inhibition and patient outcomes (PLATO) trial. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5(5):680–688. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.111.964395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rajani R, Lindblom M, Dixon G, Khawaja MZ, Hildick-Smith D, Holmberg S, et al. Evolving trends in percutaneous coronary intervention. Br J Cardiol. 2011;18(2):73–76. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang TY, Gutierrez A, Peterson ED. Percutaneous coronary intervention in the elderly. Nat Rev Cardiol [Internet] 2011;8(2):79–90. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2010.184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Qaderdan K, Vos GJA, McAndrew T, Steg PG, Hamm CW, van’t Hof A, et al. Outcomes in elderly and young patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention with bivalirudin versus heparin: pooled analysis from the EUROMAX and HORIZONS-AMI trials. Am Heart J. 2017;194(Mi):73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2017.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang Z, Fang J, Gillespie C, Wang G, Hong Y, Yoon PW. Age-specific gender differences in in-hospital mortality by type of acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol [Internet] 2012;109(8):1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meraj PM, Doshi R, Patel K, Shah J, Shah M. Gender differences in in-hospital outcomes following percutaneous coronary intervention for ST segment elevated myocardial infarction in elderly patients. JACC Cardiovasc Interv [Internet] 2017;10(3):S10. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2016.12.059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Valgimigli M, Frigoli E, Leonardi S, Vranckx P, Rothenbühler M, Tebaldi M, et al. Radial versus femoral access and bivalirudin versus unfractionated heparin in invasively managed patients with acute coronary syndrome (MATRIX): final 1-year results of a multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet [Internet]. 2018;392(10150):835–848. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.van der Meer MG, Nathoe HM, van der Graaf Y, Doevendans PA, Appelman Y. Worse outcome in women with STEMI: a systematic review of prognostic studies. Eur J Clin Investig. 2015;45(2):226–235. doi: 10.1111/eci.12399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Benamer H, Bataille S, Tafflet M, Jabre P, Dupas F, Laborne FX, et al. Longer pre-hospital delays and higher mortality in women with STEMI: the e-MUST Registry. EuroIntervention [Internet] 2016;12(5):e542–e549. doi: 10.4244/EIJV12I5A93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vandecasteele EH, De BM, Gevaert S, De MA, Convens C, Dubois P, et al. Reperfusion therapy and mortality in octogenarian STEMI patients: results from the Belgian STEMI registry. Clin Res Cardiol. 2013;102:837–845. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0600-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahmed B, Dauerman HL. Women, bleeding, and coronary intervention. Circulation. 2013;127(5):641–649. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.108290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Van De Werf F, Bax J, Betriu A, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C, Crea F, Falk V, et al. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with persistent ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2008;29(23):2909–2945. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to German data protection regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.