Abstract

Cell-free protein synthesis assays have become a valuable tool to understand transcriptional and translational processes. Here, we established a fluorescence-based coupled in vitro transcription-translation assay as a read-out system to simultaneously quantify mRNA and protein levels. We utilized the well-established quantification of the expression of shifted green fluorescent protein (sGFP) as a read-out of protein levels. In addition, we determined mRNA quantities using a fluorogenic Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer that becomes fluorescent upon binding to the fluorophore thiazole orange (TO). We utilized a Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer system comprising four subsequent Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer elements with improved sensitivity by building Mango arrays. The design of this reporter assay resulted in a sensitive read-out with a high signal-to-noise ratio, allowing us to monitor transcription and translation time courses in cell-free assays with continuous monitoring of fluorescence changes as well as snapshots of the reaction. Furthermore, we applied this dual read-out assay to investigate the function of thiamine-sensing riboswitches thiM and thiC from Escherichia coli and the adenine-sensing riboswitch ASW from Vibrio vulnificus and pbuE from Bacillus subtilis, which represent transcriptional and translational on- and off-riboswitches, respectively. This approach enabled a microplate-based application, a valuable addition to the toolbox for high-throughput screening of riboswitch function.

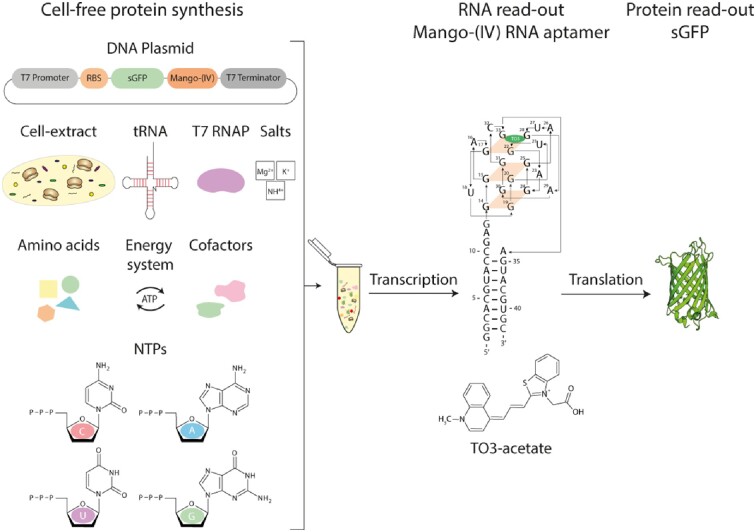

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

Cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) systems are an important research tool in synthetic biology. Their initial development was pioneered by Nirenberg and Matthaei which was essential for deciphering the genetic code (1,2). They cover a broad range of applications, including high-throughput expression and screening of membrane proteins that are difficult to synthesize, synthesis of toxic products, and the discovery of antibiotic drugs (3,4). Cell-free protein systems have been established and optimized over the years. CFPS requires cell-extracts, and the most popular cell-extracts are prepared from Escherichia coli, wheat germ, and rabbit reticulocytes (3). The cell-free system consists of a crude extract depleted of endogenous DNA and mRNA, containing the translational machinery, tRNA, enzymes, protein translation factors, and an energy regeneration system (5). In vitro cell-free protein synthesis reactions are performed using a DNA template as a circular vector or linear PCR product consisting of a strong T7 promoter sequence in the 5′-UTR, ribosome-binding site (RBS) including the Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence, and T7 terminator in the 3′-UTR (6). Cell-free reactions can be conducted in a coupled mode, where simultaneous synthesis of mRNA and protein occurs by the addition of a DNA template, or in an uncoupled mode, where mRNA is exogenously added and then translated in a cell-free manner (7).

CFPS can monitor protein expression levels using different reporter systems, including β-galactosidase (8–10), luciferase (11,12), or green fluorescent protein variants (GFP) (12,13). The approach to detect synthesized proteins using a specific fluorescent reporter protein, such as GFP, is well established (14,15). In addition, monitoring mRNA levels is crucial for quantifying the important effects on the transcription level in cell-free systems. mRNA levels can be quantified by northern blotting, yet a more elegant approach is the application of fluorogenic aptamers, which results in increased fluorescence emission after fluorogen binding to the aptamer and can potentially be applied at the same time as the quantification of translation levels of (fluorescent) reporter proteins (16).

The development of fluorogenic light-up aptamers such as Spinach, Broccoli and Mango RNA aptamers has greatly improved the field of in vitro and in vivo RNA imaging (17,18). The major advantage of these aptamers is an improved background-free approach because of the improved signal-to-noise ratio resulting from their fluorogenic properties upon ligand binding (19). The Spinach aptamer was first developed using SELEX. It binds to fluorogen 3,5-difluoro-4-hydroxybenzylidene imidazolinone (DFHBI) (17,20). Several RNA aptamer approaches have been established to monitor and quantify in vitro transcribed RNA in real time using the Spinach RNA aptamer fused to the self-cleaving hammerhead ribozyme and the RNA of interest (21) as well as the Broccoli RNA aptamer approach (22). Subsequently, Mango aptamers with improved folding, spectral, and binding properties were developed. Mango aptamers bind to the fluorogens thiazole orange and red (TO1-biotin and TO3-biotin, respectively) with sub-nanomolar affinities (23). Additionally, multiple Mango aptamer sequences in a row called Mango arrays improve the fluorescence intensity, which was demonstrated for in vivo RNA visualization setups (18).

In recent studies, Wick et al. presented an approach to quantify transcription and translation levels using the commercially available PURExpress system with Spinach RNA aptamer and non-fluorescent tetracysteine peptide tag (24,25). We have developed a cell-free system assay that simultaneously monitors mRNA and protein levels using Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer and sGFP, which has been implemented to characterize riboswitch function. Riboswitches are structured and highly conserved RNA elements that are primarily located in the 5′-UTR of many bacterial mRNAs. As genetic regulation elements, riboswitches control the expression of their downstream-located genes upon metabolite binding. Thus, regulation can occur at the level of transcription termination, translation initiation, or modulation of mRNA decay (26). Importantly, many of the involved regulatory steps occur co-transcriptionally.

Here, we investigated the adenine-sensing add riboswitch (ASW) from Vibrio vulnificus, which controls adenosine deaminase translation. The riboswitch up-regulates translation upon binding the ligand adenine in a temperature- and Mg2+-dependent manner via a three-state mechanism (27,28). Previous studies have demonstrated that the synergy of adenine, ribosomal protein rS1, and the 30S ribosome facilitates the translation initiation process for ASW. To date, cell-free studies on ASW have focused only on protein expression read-out (29,30).

Furthermore, we monitored the protein and mRNA levels of two thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitches from E. coli: thiM and thiC. Both riboswitches adopt alternative secondary structures upon binding of thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP). These TPP-stabilized secondary structures sequester the SD-sequence and AUG start-codon, resulting in translational inhibition, thus classifying the TPP riboswitches as translational off-switches (31). Interestingly, further studies revealed increased Rho-dependent transcription termination in presence of TPP (32,33).

Thus, we established a coupled in vitro transcription-translation assay using simultaneous protein- and mRNA-level monitoring with shifted GFP (sGFP) and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer. This new system opens the possibility of studying a wide variety of RNA elements involved in transcription and translation regulation, irrespective of whether the underlying effect is induced by changes in temperature, ligand concentration, or endogenous cis- or trans-acting RNA elements, both in pro- and eukaryotes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

S30 extract preparation

S30 cell-extracts were prepared using BL21 Star™ (DE3). The preparation was adapted from the protocol described by Schwarz et al. The cells were grown in yeast-tryptone-phosphate-glucose (YTPG) medium to an OD of 3 and harvested by cooling with ice (34). The cell pellets were washed with buffer S30 A (10 mM Tris/acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM Mg(OAc)2, 60 mM KCl, 6 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) and pelleted again. Cell lysis was conducted with a microfluidizer at 15 000 PSI using eight cycles in S30 buffer B (10 mM Tris/acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM Mg(OAc)2, 60 mM KCl and 1 mM DTT), followed by centrifugation of the lysate at 30 000 × g at 4°C for 30 min, which was repeated twice. To remove the endogenous mRNA, the extract was incubated with 400 mM NaCl at 42°C for 45 min. The lysate was dialyzed for 1 h at 4°C against 2.5 L S30 buffer C (10 mM Tris/acetate (pH 8.2), 14 mM Mg(OAc)2, 60 mM K(OAc), 0.5 mM DTT) using a dialysis membrane (MWCO 12–14 kDa, ZelluTrans, Carl Roth, Germany) the buffer was exchanged and dialysis was repeated three times. The S30 extract was centrifuged at 30 000 × g and 4°C for 30 min. The extracts were concentrated to half their volume using a centrifugal concentrator device (MWCO 10 kDa, VivaSpin20, Sartorius, Germany). The extracts were aliquoted, shock-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at –80°C.

Design and preparation of DNA templates

The DNA templates used in the coupled in vitro transcription-translation assays were purchased from GenScript as plasmids (pUC19) using BamHI/EcoRI restriction sites. The ASW sequence was obtained from V. vulnificus (27). The apoA and apoB mutant ASW sequences were designed according to Reining et al. and Warhaut et al. (27,28). The thiM and thiC sequences were obtained from E. coli (33,35) (Supplementary Table S1). The constructs were designed to contain T7 regulatory elements, a strong RBS for the sGFP control plasmids or the riboswitch sequences with their SD-sequences, and the sequence of sGFP followed by the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer sequence. Plasmids were prepared and purified using the QIAquick® Midi Prep Kit (Qiagen, the Netherlands) following the manufacturer's instructions and analyzed by sequencing.

Coupled in vitro transcription-translation assay

Coupled in vitro transcription-translation assays were performed as previously described by Kai et al. using in-house made cell-extracts (36). Here, mRNA levels were monitored by Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer with one or four repeats as an array, and protein expression levels were monitored using sGFP. The assays were performed in triplicate as 30 μl reactions in a 384well black microplate (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) at 30°C for various time scales. The reaction mixture contained: 15% (v/v) S30 cell-extract, 0.03 mg/ml DNA plasmid, 27.7 mM NH4OAc, 15 mM Mg(OAc)2, 202 mM potassium glutamate, 58 mM HEPES/KOH buffer (pH 8), 2% (v/v) PEG8000, 1.8 mM DTT, 14.4 mM NTP (mixture of ATP, CTP, GTP, UTP), 0.35 mg/ml folinic acid, 1× cOmplete™ EDTA-free protease inhibitor, 1 mM amino acid mixture, 20 mM acetyl phosphate, 30 mM phosphor(enol)pyruvic acid, 0.04 mg/ml pyruvate kinase, 0.65 mM cyclic AMP, 0.3 U/ml RNasin® ribonuclease inhibitor, 1 mg/ml tRNA, 0.04 mg/ml T7 RNA polymerase (in-house made). DNA plasmid was not added to the reaction mixture of the negative control samples (37).

Fluorescence measurements were performed with a Tecan Spark® microplate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) using an excitation wavelength of 470 nm and an emission wavelength of 515 nm for sGFP and an excitation wavelength of 580 nm and an emission wavelength of 650 nm for Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer.

Expression and purification of sGFP

The sGFP protein was expressed from a pIVEX 2.3d plasmid carrying a C-terminal His6-tag. This protein was overexpressed in BL21(DE3). The cells were grown in LB medium at 37°C and 120 rpm. Expression was induced at OD600 = 0.7 with 200 μM isopropyl β-d-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and cells were further incubated for 4 h at 37°C and 120 rpm. The protein was purified via HisTrap™ HP (GE Healthcare) columns using 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 10 mM imidazole and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol as lysis buffer and 50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8), 300 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole and 10 mM 2-mercaptoethanol as elution buffer. The buffer was exchanged via overnight dialysis (MWCO 3500 Da ZelluTrans/ROTH, Carl Roth, Karlsruhe, Germany) with storage buffer (25 mM potassium phosphate (pH 7.2), 150 mM KCl, and 5 mM DTT).

mRNA preparation

The reference mRNA was synthesized by in vitro transcription using PCR product as template DNA and T7 RNA polymerase (P266L mutant, in house-made) (37). The mRNA was produced in a 10 ml preparative scale and incubated at 37°C for 4 h. Transcription reactions contained 200 mM Tris/glutamate (pH 8.1), 20 mM DTT, 2 mM spermidine, 35 mM Mg(OAc)2, 10 mM NTP (mixture of ATP, CTP, GTP and UTP), 10% (v/v) PCR product, 20% (v/v) DMSO and 32 ng/μl T7 RNA polymerase. After 1 h of incubation, 8 μl/ml yeast inorganic pyrophosphate (in house-made) was added to hydrolyze insoluble magnesium pyrophosphate (38,39). The transcription mixture was centrifuged for 5 min at 8500 rpm and 4°C. The mRNA was precipitated for 1 h at –80°C in the presence of 0.3 M Na(OAc) (pH 5.5) and 2-propanol. mRNA purity was verified by 6% denaturing PAA gel electrophoresis. The extinction coefficients of the mRNAs are listed in Supplementary Table S2.

K D determination

Binding affinities were determined by titrating mRNA at constant TO3-acetate ligand concentration of 0.5 μM in 58 mM HEPES/KOH buffer (pH 8). Fluorescence measurements were performed in triplicate as 30 μl reactions using a Tecan Spark® plate reader (Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) using an excitation wavelength of 580 nm and emission wavelength of 650 nm. Binding curves were evaluated using Microsoft Excel and SigmaPlot 12.5 and fitted using the least squares of the Hill equation.

Synthesis of TO3-acetate

TO3-acetate was synthesized in-house as previously reported by Dolgosheina et al. (40).

Characterization of TO3-acetate

The extinction coefficient of TO3-acetate was determined by dilution series of TO3-acetate in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Absorption measurements were performed with a UV-vis spectrophotometer Cary 50 (Varian, California, USA) at wavelengths between 200 and 650 nm. The absorption spectra were evaluated using Microsoft Excel and SigmaPlot 12.5.

CD spectroscopy and melting curve analysis

Circular dichroism spectra were acquired on a Jasco J-810 spectropolarimeter. The measurements were recorded from 210 to 320 nm at 25°C using a 1 cm path length quartz cuvette. CD spectra were recorded on 6 μM samples of thiM and thiC mRNA in either HEPES buffer (containing 58 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 8), 200 mM potassium glutamate, 15 mM Mg(OAc)2 or in the buffer system by Autour et al. (containing 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2), 0.05% Tween 20) in the absence and presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. Spectra were acquired with eight accumulation scans, using scanning speed of 50 nm/min and the data were baseline-corrected and smoothed with Savitzky-Golay filters (20 fit) Observed ellipticities recorded in millidegree (mdeg) were converted to molar ellipticity [θ] = deg × cm2 × dmol−1. Melting curves were acquired at constant wavelength using a temperature rate of 1°C/min in a range from 5°C to 95°C. All data was evaluated using Microsoft Excel 2016 and SigmaPlot 12.5. All melting temperature data was converted to normalized ellipticity and evaluated by the Sigmoidal Fit with three parameters using SigmaPlot.

Western blot

10 μl of cell-free samples were mixed with 2x SDS sample buffer (0.25 M Tris/HCl (pH 6.8), 4% SDS, 20% glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol, 0.25% bromophenol blue) and denaturation was performed by incubation at 95°C for 5 min. Bands were separated on NuPAGE™ protein gels (4–12%, Bis-Tris Gels by Thermo Fischer Scientific) using constant voltages (200 V for 45 min). Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes and probed with a rabbit polyclonal anti-GFP antibody (Invitrogen, 1:2000 dilution). Anti-rabbit horseradish peroxidase-conjugated antibody was used as secondary antibody (Promega, 1:2200 dilution). The membranes were visualized by enhanced chemiluminescent kit (Thermo Fischer Scientific).

RESULTS

General strategy for dual read-out monitoring of protein and mRNA levels

To establish a dual read-out assay for simultaneous monitoring of mRNA and protein levels, we investigated shifted GFP (sGFP) and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer as reporters in the E. coli cell-free system. For this purpose, we designed DNA templates containing T7 regulatory elements, the RBS or riboswitch sequences, followed by the sequences of sGFP and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer (Figure 1A). To prevent interference between ribosomes during translation and folding of the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer, we added linker sequences up- and downstream (36 nt and 18 nt, respectively) of the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer sequence (Supplementary Table S1) (41).

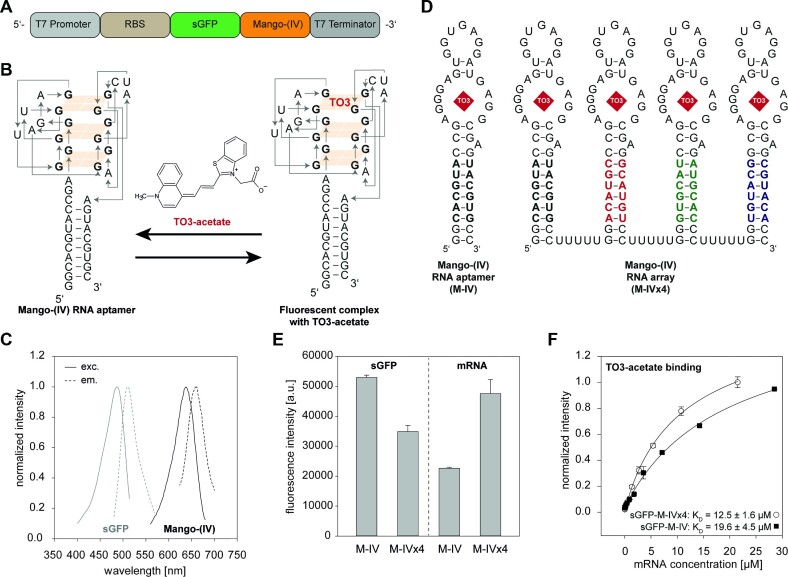

Figure 1.

Detection of mRNA and protein levels in cell-free transcription-translation systems using Mango-based fluorescence detection of mRNA and sGFP monitoring. (A) DNA template containing T7 regulatory elements, RBS, the sequence of sGFP with protein-coding start/stop sites and the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer sequence as an array of one or four repeats and T7 terminator sequence. (B) Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer construct with the binding of the ligand TO3-acetate. (C) Excitation and emission spectra of sGFP and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer fluorescent complex in the presence of TO3-acetate. (D) Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer sequence (M-IV) with TO3-acetate as ligand. For clarity, the G-quadruplex structure has been simplified. Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4) with mutated stem base pairs and a 5 nt linker sequence to prevent misfolding of individual aptamers. (E) Comparison of sGFP-M-IV and sGFP-M-IVx4 constructs at protein and mRNA levels. (F) Fluorescence binding curves for sGFP constructs with Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer monomer (M-IV) and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4) were determined at a constant TO3-acetate ligand concentration (0.5 μM). Samples were measured in triplicate.

For our mRNA read-out in the CFPS studies, we utilized the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer that forms a fluorescent complex with its ligand TO3-acetate (Figure 1B). After the synthesis of TO3-acetate ligand, we performed absorption measurements in DMSO by UV-vis spectroscopy to determine the extinction coefficient of the ligand (Supplementary Figure S1A, B). To verify our reporter pair of Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer and sGFP for monitoring mRNA and protein levels in the CFPS systems, we spectroscopically characterized the optimal excitation and emission wavelengths of sGFP and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer in presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate (Figure 1C) (42). Furthermore, the influence of TO3-acetate on sGFP and mRNA expression was tested using a coupled transcription-translation system. Importantly, sGFP expression was not influenced by TO3-acetate addition and for mRNA read-out increased fluorescence intensity was observed in the presence of TO3-acetate, reporting on binding to Mango-(IV)-tagged mRNA. All CFPS reactions were monitored in presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate (Supplementary Figure S1C).

To improve mRNA read-out, we designed a Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array similar to the Mango-(II) RNA aptamer array by Cawte et al. (18). For our Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array construct, with four Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer sequences in a row, we optimized the stem sequences of the aptamers by altering the Watson-Crick base pairs, which prevents intramolecular interactions between the aptamers. Furthermore, the individual aptamers were linked by 5 nt U-spacers (Figure 1D). In line with the reported results that aptamer arrays significantly improve fluorescence intensity, our coupled transcription-translation data showed that the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4) resulted in a 2.1-fold increase in fluorescence intensity compared to the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer monomer (M-IV). At the same time, the sGFP expression level decreased by 1.5-fold for the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4). Reduced expression levels could be tolerated, as the sGFP read-out in our experiments remained very sensitive (Figure 1E).

We determined the binding affinity of the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer monomer (M-IV) and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4) using the sGFP control constructs which showed a tighter binding of TO3-acetate ligand to either Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4) or the individual Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer (M-IV) revealing a KD (sGFP-M-IVx4) = 12.5 ± 1.6 μM and a KD (sGFP-M-IV) = 19.6 ± 4.5 μM, respectively (Figure 1F).

Calibration of mRNA and protein levels in the cell-free system

To quantify protein and mRNA levels in the cell-free system, we prepared sGFP protein and mRNA reference samples. The expressed and purified sGFP protein was diluted in cell-free buffer (58 mM HEPES/KOH buffer (pH 8)) and with the fluorescence measurements we determined that 1 a.u. corresponds to 506.6 nM (gain 50) and 23.5 nM (gain 70) sGFP concentration (Supplementary Figure S2A, B). The mRNA reference constructs were prepared by in vitro transcription, diluted in cell-free buffer, and measured in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. The obtained calibration fit was used to determine mRNA concentrations in the cell-free transcription-translation system. We determined that 1 a.u. fluorescence intensity corresponded to 193 nM of mRNA (Supplementary Figure S2C). The conversion factors for the other mRNAs used in our study were determined using the same procedure.

Investigation of thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitches by CFPS

Transcriptional and translational thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitches thiC and thiM were investigated using fluorescence-based coupled in vitro transcription-translation systems by simultaneous monitoring of sGFP expression and mRNA levels with Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer arrays. Previous studies have reported that thiC controls gene expression at both, the transcriptional and translational levels. Thus, in the presence of TPP, it is expected that the mRNA and protein levels will decrease if thiC acts as a transcriptional and translational off-switch (31). In contrast, thiM has been previously described as a translational off-switch, where the addition of TPP was reported to attenuate protein levels (31,43); however, Bastet et al. demonstrated also a Rho-dependent transcription termination controlling mRNA levels (32).

We established a riboswitch-based cell-free protein assay using TPP-sensing riboswitches, thiM and thiC, from E. coli (Figure 2A, B). We designed the DNA templates for our riboswitch constructs using T7 regulatory elements, the riboswitch sequence consisting of the SD-sequence and start-codon, followed by the sGFP gene and a Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (Supplementary Table S1). Previous studies performed by Chauvier et al. and Bastet et al. focused on transcription termination studies using E. coli RNA polymerase (32,33). We used T7 regulatory elements and the P266L T7 RNA polymerase mutant to perform the coupled transcription-translation assay with high RNA yields, and to ensure RNA folding during transcription, the reactions were performed at 30°C. First, we tested the influence of TPP on the coupled transcription-translation reaction of our control plasmid sGFP-M(IVx4), which contains a strong RBS, sGFP, and M-IVx4 RNA aptamer array sequence. The mRNA and sGFP levels were not influenced in presence of TPP (Supplementary Figure S3A, B). For mRNA quantification in the coupled transcription-translation assay, we prepared thiM and thiC mRNA reference samples by in vitro transcription. Both mRNAs were diluted in cell-free buffer and measured in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. We determined that 1 a.u. fluorescence intensity corresponded to 101 nM of thiM mRNA and 182 nM of thiC mRNA (Supplementary Figure S4A). Furthermore, we determined the binding affinities of TO3-acetate to thiM and thiC Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array constructs. ThiM mRNA showed almost identical affinity to 0.5 μM TO3-acetate with a KD (thiM) = 1.46 ± 0.17 μM compared to thiC mRNA (KD (thiC) = 2.00 ± 0.17 μM) (Supplementary Figure S4B). We also determined similar binding affinities in the μM range of TO3-acetate for both riboswitch constructs in different buffer conditions, including HEPES buffer (containing 58 mM HEPES/KOH (pH 8), 200 mM potassium glutamate, 15 mM Mg(OAc)2, and in the buffer system used by Autour et al. (containing 140 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM NaH2PO4 (pH 7.2), 0.05% Tween 20) (44). In particular, we determined binding affinities of KD (thiM in HEPES buffer) = 6.40 ± 0.47 μM and KD (thiC in Autour buffer) = 7.31 ± 2.65 μM (Supplementary Figure S4C). Both riboswitch constructs showed tighter binding with identical affinities to TO3-acetate than the sGFP-M-IVx4 construct (Figure 1F). To verify the G-quadruplex formation of the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer, we obtained CD spectra and thermal melting properties very similar to those of Autour et al. (44). The thermal melting properties were largely unaffected by the addition of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. We obtained a melting temperature of TM (thiC in HEPES buffer) = 48.27 ± 0.89°C in the absence of TO3-acetate and TM (thiC in HEPES buffer) = 49.88 ± 0.68°C in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate in HEPES buffer. In the buffer system used by Autour et al. we obtained melting temperatures of TM (thiM in Autour buffer) = 51.88 ± 0.56°C in the absence of TO3-acetate and TM (thiM in Autour buffer) = 53.44 ± 0.53°C in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate (Supplementary Figure S5).

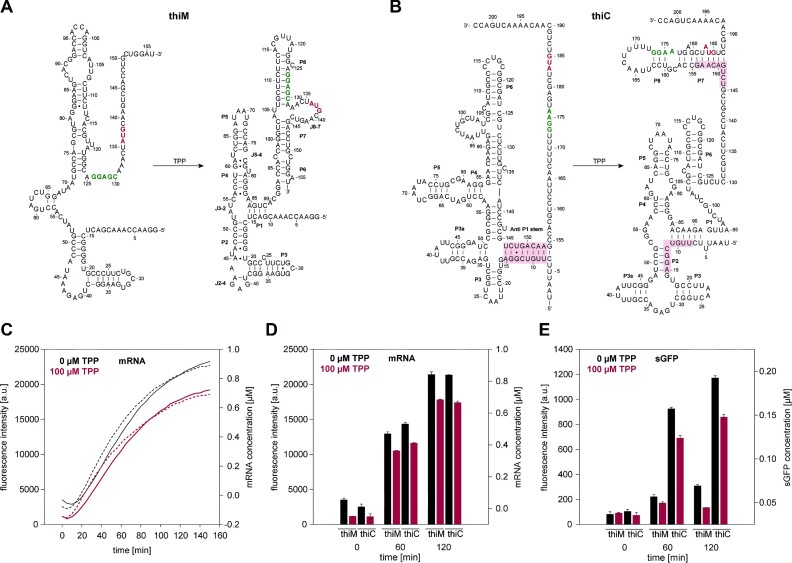

Figure 2.

TPP-sensing riboswitches thiM and thiC regulate transcription and translation in the context of TPP. (A) Schematic overview of the thiM riboswitch from E. coli representing the TPP-unbound and TPP-bound states. In the presence of TPP, the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (green) and AUG start-codon (red) are sequestered and not accessible to the ribosome. (B) Schematic overview of the thiC construct from E. coli representing the TPP-unbound and TPP-bound states. In the presence of TPP, translation initiation is inhibited by sequestration of the SD-sequence (green) and the AUG start-codon (red). (C) Time-dependent changes in mRNA levels monitored in a coupled transcription-translation assay of thiM (solid line) and thiC (dashed line) riboswitches with 0 and 100 μM TPP concentrations. Data were corrected with a negative control (without DNA) in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. The samples were measured in triplicate, with a gain of 110 in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. (D) mRNA monitoring of thiM and thiC in a coupled transcription-translation assay in the presence of 0 and 100 μM TPP. Data were corrected with a negative control (without DNA) in presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. Results are shown for time points 0, 60 and 120 min and were measured in triplicate with a gain of 110 in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. (E) sGFP monitoring of thiM and thiC in a coupled transcription-translation assay in the presence of 0 and 50 μM TPP. Data were corrected with a negative control (without DNA) in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. Results are shown for time points 0, 60 and 120 min and were measured in triplicate with a gain of 70 in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate.

Our dual read-out data demonstrated the influence of TPP on the mRNA and protein levels of thiM and thiC. The mRNA levels of thiM and thiC were monitored in a time-dependent manner for 150 min in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate and TPP (0 and 100 μM, respectively). In the presence of 100 μM TPP, the mRNA transcription levels decreased by 1.2-fold for thiM and thiC. This result confirmed the previously described transcriptional off-switch characteristic of thiC in the presence of TPP. In literature, thiM has been described as a translational off-switch, but our data displayed the transcriptional off-switch ability of thiM (Figure 2C). Generally, mRNA transcription plateaued after 120 min of incubation. Therefore, we performed further in vitro transcription-translation CFPS experiments for a maximum of 120 min.

Although the data were continuously monitored, we compared the transcription and translation for both riboswitches at only three reaction time points, namely, after 0, 60 and 120 min of reaction time. Interestingly, the mRNA level of thiM decreased by 1.2-fold in the presence of TPP. Here, we determined a total mRNA concentration for thiM of 0.7 μM and thiC of 0.6 μM in the presence of 100 μM TPP and 0.8 μM thiM and thiC mRNA without TPP addition after 120 min incubation (Figure 2D). The mRNA concentrations were quantified with the obtained values from Supplementary Figure S4A.

Additionally, we monitored the influence of TPP on the sGFP expression of thiM and thiC. Although the mRNA levels of both riboswitches remained similar, we observed 4-fold increased sGFP levels for thiC compared to thiM in absence of TPP. In the presence of 100 μM TPP and after 120 min incubation, the sGFP levels for both riboswitches thiM and thiC decreased by 2.3-fold and 1.4-fold, respectively (Figure 2E and Supplementary Figure S6).

After the coupled transcription-translation reactions the sGFP expression of thiM and thiC samples were investigated by Western blot. However, the sGFP expression was not detectable for both TPP-sensing riboswitches thiM and thiC. (Supplementary Figure S7).

Investigation of adenine-sensing riboswitches by CFPS

Further, we investigated the transcriptional and translational levels of the transcription-regulating adenine-sensing riboswitch pbuE from Bacillus subtilis. Upon adenine binding the transcriptional anti-terminator sequence in the expression platform is modulated and regulation occurs as a transcriptional on-switch. For our study, we used a pbuE DNA template, similar to the TPP- and adenine-sensing riboswitches, containing a transcription start site upstream of the structured riboswitch region, the SD-sequence and the translation start-codon, as well as the sGFP and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array sequence (Supplementary Table S1). For the pbuE mRNA we determined similar binding affinities of TO3-acetate of KD (pbuE) = 2.43 ± 1.07 μM and 1 a.u. fluorescence intensity corresponds to 147 nM (Supplementary Figure S8).

In the presence of 0.25 mM adenine and 0.5 μM TO3-acetate, mRNA levels are increased by 1.2-fold and protein expression levels are slightly increased by 1.05-fold, confirming the transcriptional on-switch character of the adenine-sensing pbuE riboswitch (Supplementary Figure S9A, B). Interestingly, the mRNA is transcribed at low levels, resulting in high sGFP expression levels. We also tested 0.5 and 1 mM adenine concentrations, which resulted in 1.2-fold better switching factors in the presence of low adenine concentrations, while sGFP expression levels remained similar for all three adenine concentrations (Supplementary Figure S9C, D). Previous work has described the pbuE riboswitch as regulated under kinetic control, with adenine co-transcriptionally bound as the riboswitch mRNA is transcribed and folded, explaining the need for low adenine concentrations (45).

Furthermore, we investigated the translation-regulating add adenine-sensing riboswitch (ASW) from V. vulnificus. Previous studies have reported that ASW controls gene expression at a translational level. In the presence of adenine, protein expression is expected to increase, as it acts as a translational on-switch. Further, the translation-regulation of ASW is described as a three-state mechanism where ASW has bistable secondary structures in the ligand-free apo state (27,28). Here, the apoB conformation is unable to bind adenine and is a representative off-state. In the absence of adenine, the apoA conformation remains in the off-state, which is converted to a translational on-state in the presence of adenine with an accessible SD-sequence for successful ribosome binding to the mRNA. Further, it was shown that the incorporation of adenine, 30S ribosome, and ribosomal protein rS1 acting as a chaperone are essential for translation initiation of ASW (29,30).

For our study, we used ASW constructs containing a transcription start site (TSS) located 7 nt upstream of the structured region of the riboswitch, the SD-sequence, and start-codon. We added 18 nt of the ASW coding region prior to the sGFP gene sequence to ensure native ribosome binding (Figure 3A). The DNA templates for the adenine-sensing riboswitch constructs were designed similarly to our previously described TPP-sensing riboswitches, containing the T7 regulatory elements, riboswitch sequence consisting of SD-sequence and start-codon, as well as the sGFP and Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array sequence (Supplementary Table S1).

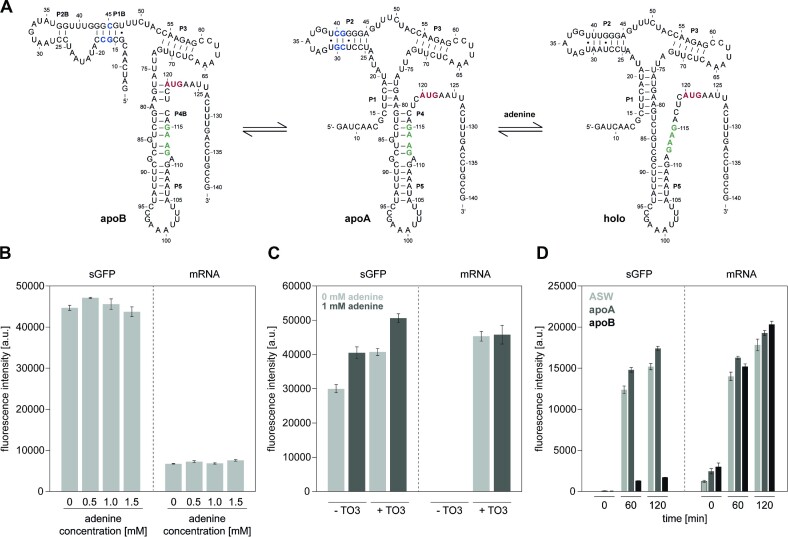

Figure 3.

Characterization of adenine-sensing riboswitch ASW in a coupled transcription-translation assay in the context of adenine. (A) Schematic overview of the three-state conformational equilibrium of the add ASW constructs from V. vulnificus. The mutated nucleotides of apoA and apoB are highlighted in blue, the SD-sequence in green, and the AUG start-codon in red. (B) Influence of adenine on the mRNA and protein levels of the control plasmid sGFP, containing a strong RBS. The coupled transcription-translation reactions were performed at 30°C and measured in triplicate with a gain of 50 for sGFP and 80 for mRNA. (C) sGFP and mRNA monitoring of ASW in a coupled transcription-translation assay in the presence and absence of adenine (1 mM) and TO3-acetate (0.5 μM). Reactions were performed at 30°C and measured in triplicate with a gain of 80 for sGFP and 110 for mRNA. (D) sGFP and mRNA monitoring of ASW, apoA and apoB in a coupled transcription-translation assay in the presence of 1 mM adenine and 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. Data were corrected with a negative control (without DNA) in the presence of 0.5 μM TO3-acetate. Reactions were performed at 30°C and measured in triplicate with a gain of 70 for sGFP and 110 for mRNA.

First, we tested the effect of adenine on the control plasmid sGFP-M-IVx4. CFPS results demonstrated that the mRNA and protein levels were not influenced by adenine (Figure 3B).

Further, we studied the adenine-sensing riboswitch constructs of ASW, apoA and apoB in the CFPS system in adenine-dependent experiments. Here, we investigated adenine-dependent regulation of ASW expression. In the presence of 1 mM adenine, an increase in sGFP protein expression of 1.4-fold (0 μM TO3-acetate) and 1.2-fold (0.5 μM TO3-acetate) was observed. However, mRNA transcription levels were not affected by the addition of adenine, confirming that ASW acts at the translational level (Figure 3C).

In addition to the wildtype ASW, we also studied the stabilized on- and off-mutants: apoA and apoB. We simultaneously monitored the time-dependent protein and mRNA expression of ASW, apoA and apoB in the presence of 1 mM adenine and 0.5 μM TO3-acetate at 30°C. ASW and apoA expressed high levels of sGFP protein. After 60 min of incubation at 30°C, a 1.2-fold increase in protein expression was observed for apoA with an sGFP concentration of 2.5 μM after 120 min of incubation compared to ASW, confirming the translational on-state of the apoA mutant in the presence of adenine. The off-mutant apoB remained in its translational off-state and produced sGFP only in low quantities (Supplementary Figure S10A). Interestingly, apoB transcribed high levels of mRNA in the cell-free system, which were not transcribed into the sGFP protein (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S10B). We quantified the mRNA levels with in vitro transcribed mRNAs as references and reported 0.7 μM ASW, 0.9 μM apoA and 1.2 μM apoB mRNA produced in the cell-free reactions after 120 min of incubation at 30°C (Supplementary Figure S11B, C). Using coupled in vitro transcription-translation assays, we were able to demonstrate and confirm the characteristic features of ASW, apoA, and apoB at the translational level, as the mRNA levels remained unaffected in the presence of adenine.

DISCUSSION

We established a dual read-out in vitro transcription-translation system to monitor mRNA and protein levels to investigate transcriptional and translational riboswitches in a cell-free environment simultaneously. Notably, using the orthogonal reporter systems of the RNA Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer and sGFP chromophore enabled us to dissect the time-dependent levels of mRNA and protein production instead of snapshots of the reaction. Further, we improved the mRNA read-out by designing a Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer array (M-IVx4) constructs, with four Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer sequences in a row. In the coupled transcription-translation experiments, the M-IVx4 array construct showed increased in fluorescence intensity for mRNA read-out by 2.1-fold compared to the Mango-(IV) RNA aptamer monomer (M-IV) construct. Mango-(II) RNA aptamer arrays were previously reported by Cawte et al. to improve in vivo RNA imaging (18).

We investigated the effects of ligands on the thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitches thiM and thiC from E. coli, as well as the adenine-sensing riboswitch ASW from V. vulnificus and monitored the mRNA and protein levels. Here, we dissected the influence of TPP on thiM and thiC riboswitches, and our cell-free results confirmed the transcriptional and translational off-switch characteristic of thiM and thiC. The thiM riboswitch was previously shown to regulate only at the translational level by inhibiting translation initiation (31,43). Chauvier et al. demonstrated a pausing region close to the ribosome-binding site and start-codon in the expression platform for thiC, suggesting a transcriptional regulation. Furthermore, the regulation mechanism of thiC was described as a Rho-dependent transcription termination and inhibited translation initiation in presence of TPP (33). The TPP-dependent transcriptional off-switch regulation mechanism of thiM was revealed by Bastet et al. using in vivo and in vitro assays (32). Our results demonstrated both transcriptional and translational off-switch characteristics of thiM, as the mRNA and protein levels were decreased in the presence of 100 μM TPP. The previously described regulation characteristics of thiM and thiC were thus confirmed and quantified using coupled transcription-translation assay (Figure 2C–E, Table 1).

Table 1.

Comparison of the regulation mechanisms of thiM, thiC, and ASW riboswitches between the reported regulation mechanism and our cell-free results from the coupled transcription-translation assays

| Cell-free results | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Riboswitch | Mode of regulation | mRNA level | sGFP level |

| thiM from E. coli | transcriptional & translational off-switch (27,28,39) | decreased in presence of TPP | decreased in presence of TPP |

| thiC from E. coli | transcriptional & translational off-switch (27,29) | decreased in presence of TPP | decreased in presence of TPP |

| ASW from V. vulnificus | translational on-switch (23–26) | not affected in presence of adenine | increased in presence of adenine |

We verified the transcriptional on-switch and translational on-switch activity of the adenine-sensing riboswitches pbuE from B. subtilis and ASW from V. vulnificus, respectively. Protein levels were unaffected for the transcription-regulating pbuE riboswitch and ASW mRNA levels were not affected by the presence of adenine. Mandal et al. showed a 4-fold decrease in the in vivo β-galactosidase assay in the presence of adenine in the culture medium (46). Lemay et al. performed an in vitro assay using the B. subtilis RNA polymerase with the T7 RNAP they did not observe ligand-induced transcriptional modulation (45) Previous ASW studies using cell-free systems focused only on protein expression whereas mRNA levels were not considered (27,29,30). Here, we first verified the switching character of ASW by 1.2-fold in the presence of 1 mM adenine and demonstrated significant differences between ASW and its apo conformations at the protein level. Additionally, apoA showed increased protein expression of 2.6 μM sGFP compared to ASW of 2.3 μM sGFP. The apoB state was confirmed to be in its off-state by decreasing sGFP expression levels (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S5A). Importantly, the mRNA levels of ASW, apoA, and apoB were not affected by the addition of adenine. Interestingly, the mRNA transcription level of apoB was comparable to that of ASW and apoA, but because of the sequestered SD-sequence and start-codon of apoB, its mRNA was not translated into sGFP (Figure 3D, Supplementary Figure S5B, Table 1).

The time-dependent dual read-out in vitro transcription-translation assay is manifested in its ability to simultaneously monitor mRNA and protein production dynamics in a cell-free environment. This approach is beneficial for riboswitch and other regulatory RNA investigations as well as for mRNA stability studies of eukaryotic mRNAs. As the assay conditions such as temperature, reaction ingredients and their relative concentrations can be easily adjusted, regulatory RNAs from a wide range of bacteria including extremophilic bacteria can be investigated. Addition of a plasmid encoding, e.g. Rho can be used to clarify the mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Furthermore, the influence of promising ligands and their derivatives may be investigated for regular or orphan riboswitches and riboswitch candidates. Time resolution enables direct monitoring of sGFP expression kinetics influenced by mRNA structure, riboswitch ligand availability and/or mRNA codon usage. Within this controlled system, the potential influence by mRNA stability and transcript lifetime can easily be controlled via the Mango fluorescence signal, allowing for clean and straightforward interpretation of the assay results. Finally, the translation machinery itself can be manipulated to observe its impact on riboswitch function (30).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the research group of Volker Dötsch for kindly providing the pIVEX-sGFP plasmid. We also thank Andreas Schmidt and Boris Fürtig for insightful discussions.

Notes

Present address: Nusrat S. Qureshi, EMBL Heidelberg, Heidelberg, Baden-Württemberg 69117, Germany.

Contributor Information

Jasleen Kaur Bains, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse 60438, Germany.

Nusrat Shahin Qureshi, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse 60438, Germany.

Betül Ceylan, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse 60438, Germany.

Anna Wacker, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse 60438, Germany.

Harald Schwalbe, Institute for Organic Chemistry and Chemical Biology, Center for Biomolecular Magnetic Resonance (BMRZ), Johann Wolfgang Goethe-University, Frankfurt am Main, Hesse 60438, Germany.

Data Availability

Plasmids are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary to confirm the conclusions of the article are included in the article, figures and tables.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

German funding agency (DFG) in Collaborative Research Center 902: Molecular Principles of RNA-based Regulation. Work at BMRZ was supported by the state of Hesse. Funding for open access charge: Institutional funding.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Nirenberg M.W., Matthaei J.H. The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon naturally occurring or synthetic polyribonucleotides. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1961; 47:1588–1602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Matthaei H., Nirenberg M.W. The dependence of cell-free protein synthesis in E. coli upon RNA prepared from ribosomes. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1961; 4:404–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Katzen F., Chang G., Kudlicki W. The past, present and future of cell-free protein synthesis. Trends Biotechnol. 2005; 23:150–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. He M. Cell-free protein synthesis: applications in proteomics and biotechnology. N. Biotechnol. 2008; 25:126–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Spirin A.S. High-throughput cell-free systems for synthesis of functionally active proteins. Trends Biotechnol. 2004; 22:538–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ohashi H., Kanamori T., Shimizu Y., Ueda T. A highly controllable reconstituted cell-free system - a breakthrough in protein synthesis research. Curr. Pharm. Biotechnol. 2010; 11:267–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hansen M.M.K., Ventosa Rosquelles M., Yelleswarapu M., Maas R.J.M., van Vugt-Jonker A.J., Heus H.A., Huck W.T.S. Protein synthesis in coupled and uncoupled cell-free prokaryotic gene expression systems. ACS Synth. Biol. 2016; 5:1433–1440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. DeVries J.K., Zubay G. DNA-directed peptide synthesis. II. The synthesis of the alpha-fragment of the enzyme beta-galactosidase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1967; 57:1010–1012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zubay G., Lederman M., DeVries J.K. DNA-directed peptide synthesis. 3. Repression of beta-galactosidase synthesis and inhibition of repressor by inducer in a cell-free system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1967; 58:1669–1675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Zhou Y., Gottesman S. Regulation of proteolysis of the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. J. Bacteriol. 1998; 180:1154–1158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sato W., Rasmussen M., Deich C., Engelhart A.E., Adamala K.P. Expanding luciferase reporter systems for cell-free protein expression. Sci. Rep. 2022; 12:11489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Voyvodic P.L., Pandi A., Koch M., Conejero I., Valjent E., Courtet P., Renard E., Faulon J.-L., Bonnet J. Plug-and-play metabolic transducers expand the chemical detection space of cell-free biosensors. Nat. Commun. 2019; 10:1697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li J., Gu L., Aach J., Church G.M. Improved cell-free RNA and protein synthesis system. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e106232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Enterina J.R., Wu L., Campbell R.E. Emerging fluorescent protein technologies. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015; 27:10–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Mishin A.S., Belousov V.V., Solntsev K.M., Lukyanov K.A. Novel uses of fluorescent proteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2015; 27:1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chizzolini F., Forlin M., Cecchi D., Mansy S.S. Gene position more strongly influences cell-free protein expression from operons than T7 transcriptional promoter strength. ACS Synth. Biol. 2014; 3:363–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Paige J.S., Wu K.Y., Jaffrey S.R. RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein. Science. 2011; 333:642–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cawte A.D., Unrau P.J., Rueda D.S. Live cell imaging of single RNA molecules with fluorogenic Mango II arrays. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:1283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kertsburg A., Soukup G.A. A versatile communication module for controlling RNA folding and catalysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002; 30:4599–4606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Warner K.D., Chen M.C., Song W., Strack R.L., Thorn A., Jaffrey S.R., Ferré-D’Amaré A.R. Structural basis for activity of highly efficient RNA mimics of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2014; 21:658–663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Höfer K., Langejürgen L.V., Jäschke A. Universal aptamer-based real-time monitoring of enzymatic RNA synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013; 135:13692–13694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kartje Z.J., Janis H.I., Mukhopadhyay S., Gagnon K.T. Revisiting T7 RNA polymerase transcription in vitro with the Broccoli RNA aptamer as a simplified real-time fluorescent reporter. J. Biol. Chem. 2021; 296:100175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Autour A., Jeng S.C.Y., Cawte A.D., Abdolahzadeh A., Galli A., Panchapakesan S.S.S., Rueda D., Ryckelynck M., Unrau P.J. Fluorogenic RNA Mango aptamers for imaging small non-coding RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9:656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wick S., Walsh D.I., Bobrow J., Hamad-Schifferli K., Kong D.S., Thorsen T., Mroszczyk K., Carr P.A. PERSIA for direct fluorescence measurements of transcription, translation, and enzyme activity in cell-free systems. ACS Synth. Biol. 2019; 8:1010–1025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Shimizu Y., Kanamori T., Ueda T. Protein synthesis by pure translation systems. Methods. 2005; 36:299–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Breaker R.R. Riboswitches and the RNA world. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2012; 4:a003566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Reining A., Nozinovic S., Schlepckow K., Buhr F., Fürtig B., Schwalbe H. Three-state mechanism couples ligand and temperature sensing in riboswitches. Nature. 2013; 499:355–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Warhaut S., Mertinkus K.R., Höllthaler P., Fürtig B., Heilemann M., Hengesbach M., Schwalbe H. Ligand-modulated folding of the full-length adenine riboswitch probed by NMR and single-molecule FRET spectroscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:5512–5522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Qureshi N.S., Bains J.K., Sreeramulu S., Schwalbe H., Fürtig B. Conformational switch in the ribosomal protein S1 guides unfolding of structured RNAs for translation initiation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:10917–10929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. de Jesus V., Qureshi N.S., Warhaut S., Bains J.K., Dietz M.S., Heilemann M., Schwalbe H., Fürtig B. Switching at the ribosome: riboswitches need rProteins as modulators to regulate translation. Nat. Commun. 2021; 12:4723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Winkler W., Nahvi A., Breaker R.R. Thiamine derivatives bind messenger RNAs directly to regulate bacterial gene expression. Nature. 2002; 419:952–956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Bastet L., Chauvier A., Singh N., Lussier A., Lamontagne A.-M., Prévost K., Massé E., Wade J.T., Lafontaine D.A. Translational control and Rho-dependent transcription termination are intimately linked in riboswitch regulation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017; 45:7474–7486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chauvier A., Picard-Jean F., Berger-Dancause J.-C., Bastet L., Naghdi M.R., Dubé A., Turcotte P., Perreault J., Lafontaine D.A. Transcriptional pausing at the translation start site operates as a critical checkpoint for riboswitch regulation. Nat. Commun. 2017; 8:13892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Schwarz D., Junge F., Durst F., Frölich N., Schneider B., Reckel S., Sobhanifar S., Dötsch V., Bernhard F. Preparative scale expression of membrane proteins in Escherichia coli-based continuous exchange cell-free systems. Nat. Protoc. 2007; 2:2945–2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Serganov A., Polonskaia A., Phan A.T., Breaker R.R., Patel D.J. Structural basis for gene regulation by a thiamine pyrophosphate-sensing riboswitch. Nature. 2006; 441:1167–1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kai L., Dötsch V., Kaldenhoff R., Bernhard F. Artificial environments for the co-translational stabilization of cell-free expressed proteins. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e56637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Milligan J.F., Uhlenbeck O.C. Synthesis of small RNAs using T7 RNA polymerase. Methods Enzymol. 1989; 180:51–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kunitz M. Crystalline inorganic pyrophosphatase isolated from baker's yeast. J. Gen. Physiol. 1952; 35:423–450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Schnieders R., Knezic B., Zetzsche H., Sudakov A., Matzel T., Richter C., Hengesbach M., Schwalbe H., Fürtig B. NMR Spectroscopy of Large Functional RNAs: from Sample Preparation to Low-Gamma Detection. Curr. Protoc. Nucleic Acid Chem. 2020; 82:e116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dolgosheina E.V., Jeng S.C.Y., Panchapakesan S.S.S., Cojocaru R., Chen P.S.K., Wilson P.D., Hawkins N., Wiggins P.A., Unrau P.J. RNA mango aptamer-fluorophore: a bright, high-affinity complex for RNA labeling and tracking. ACS Chem. Biol. 2014; 9:2412–2420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. van Nies P., Canton A.S., Nourian Z., Danelon C. Monitoring mRNA and protein levels in bulk and in model vesicle-based artificial cells. Methods Enzymol. 2015; 550:187–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. van Nies P., Nourian Z., Kok M., van Wijk R., Moeskops J., Westerlaken I., Poolman J.M., Eelkema R., van Esch J.H., Kuruma Y. et al. Unbiased Tracking of the Progression of mRNA and Protein Synthesis in Bulk and in Liposome-Confined Reactions. Chem. Bio. Chem. 2013; 14:1963–1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Ontiveros-Palacios N., Smith A.M., Grundy F.J., Soberon M., Henkin T.M., Miranda-Ríos J. Molecular basis of gene regulation by the THI-box riboswitch. Mol. Microbiol. 2008; 67:793–803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Autour A., C Y Jeng S., D Cawte A., Abdolahzadeh A., Galli A., Panchapakesan S.S.S., Rueda D., Ryckelynck M., Unrau P.J Fluorogenic RNA Mango aptamers for imaging small non-coding RNAs in mammalian cells. Nat. Commun. 2018; 9:656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lemay J.-F., Desnoyers G., Blouin S., Heppell B., Bastet L., St-Pierre P., Massé E., Lafontaine D.A. Comparative study between transcriptionally- and translationally-acting adenine riboswitches reveals key differences in riboswitch regulatory mechanisms. PLoS Genet. 2011; 7:e1001278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Mandal M., Breaker R.R. Adenine riboswitches and gene activation by disruption of a transcription terminator. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2004; 11:29–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Plasmids are available upon request. The authors affirm that all data necessary to confirm the conclusions of the article are included in the article, figures and tables.