Abstract

CRISPR-cas loci typically contain CRISPR arrays with unique spacers separating direct repeats. Spacers along with portions of adjacent repeats are transcribed and processed into CRISPR(cr) RNAs that target complementary sequences (protospacers) in mobile genetic elements, resulting in cleavage of the target DNA or RNA. Additional, standalone repeats in some CRISPR-cas loci produce distinct cr-like RNAs implicated in regulatory or other functions. We developed a computational pipeline to systematically predict crRNA-like elements by scanning for standalone repeat sequences that are conserved in closely related CRISPR-cas loci. Numerous crRNA-like elements were detected in diverse CRISPR-Cas systems, mostly, of type I, but also subtype V-A. Standalone repeats often form mini-arrays containing two repeat-like sequence separated by a spacer that is partially complementary to promoter regions of cas genes, in particular cas8, or cargo genes located within CRISPR-Cas loci, such as toxins-antitoxins. We show experimentally that a mini-array from a type I-F1 CRISPR-Cas system functions as a regulatory guide. We also identified mini-arrays in bacteriophages that could abrogate CRISPR immunity by inhibiting effector expression. Thus, recruitment of CRISPR effectors for regulatory functions via spacers with partial complementarity to the target is a common feature of diverse CRISPR-Cas systems.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

CRISPR-Cas are diverse defense systems of archaea and bacteria that provide adaptive immunity against foreign genetic elements (1–4). CRISPR-cas loci typically consist of CRISPR arrays and protein-coding cas genes. The cas genes can be classified into 4 modules that encode proteins involved in different stages of the CRISPR immune response: (i) adaptation –incorporation of segments of foreign DNA as spacers into CRISPR arrays, (ii) expression—processing of the long transcript of the CRISPR array into mature CRISPR (cr) RNAs that consist of a spacer and portions of the flanking repeats, (iii) interference—recognition and cleavage of the target DNA or RNA and (iv) accessory genes involved in different, particularly, regulatory functions. The Cas proteins involved in interference, together with mature crRNAs, comprise the CRISPR effector complexes that, in some CRISPR-Cas systems, also contribute to crRNA maturation (5–8). The CRISPR effector complexes differ in their organization among the CRISPR-Cas classes, types and subtypes, and comprise the principal basis for the classification of CRISPR-Cas systems (6). In most CRISPR-Cas systems, the effector complex recognizes a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) in the target DNA, promotes base-paring of the crRNA spacer with the corresponding protospacer and cleaves the target if the complementarity between the spacer and the target sequence is sufficiently extensive (9,10).

Most of the CRISPR spacers for which protospacer matches were detected target Mobile Genetic Elements (MGEs) including both viruses and plasmids, in accord with the notion that adaptive immunity against foreign nucleic acids is the primary function of CRISPR-Cas (11,12). In addition, however, CRISPR repeats and arrays are subject to neofunctionalization whereby target recognition serves functions other than immunity, in particular, gene expression regulation (13–16). By far the best characterized case of CRISPR repeat repurposing is the trans-activating crRNA (tracrRNA), an RNA molecule that is encoded adjacent to the effector modules of type II and some type V CRISPR-Cas systems (Figure 1). The tracrRNAs contain an anti-repeat sequence that forms a duplex with the crRNA repeat but lacks a counterpart to the spacer. Through the complementary interaction between the repeat and the antirepeat, the tracrRNA stabilizes the complex of the crRNA with the effector protein (Cas9 or Cas12, in types II and V, respectively) and is required both for the crRNA maturation and for interference (17–20). In some type V CRISPR systems, a function similar to that of tracrRNA is performed by a structurally distinct short-complementarity untranslated RNA (scoutRNA) (21).

Figure 1.

Diverse CRISPR repeat-containing RNA molecules in CRISPR-Cas systems. The figure shows previously characterized crlRNA molecules encoded in intergenic regions of CRISPR-cas loci (see text for details).

The functionality of crRNAs critically depends on the degree of complementarity between the spacer and the target such that partial complementarity can prevent target cleavage and turn an interfering crRNA into a regulatory RNA (Figure 1). In the recently discovered long tracrRNA (tracr-L) that is produced by the type II-A CRISPR-Cas system of Streptococcus pyogenes, addition of another repeat-like sequence with a short spacer-like sequence turns the tracrRNA into a transcription repressor (22). The tracr-L-Cas9 complex forms an 11 bp duplex with the cas9 promoter, resulting in highly efficient autorepression which prevents autoimmunity (22). Comparative analysis of the II-A loci showed that tracr-L is broadly although not universally conserved indicating that Cas9 autorepression is a widespread mechanism of CRISPR regulation (22).

A well characterized case of repeat repurposing is the small, CRISPR-associated RNA (scaRNA) of the bacterium Francisella novicida which guides Cas9 to bind but not to cleave the target due to limited spacer-protospacer complementarity (23). The complex of Cas9 with scaRNA binds the target sequence near the transcriptional start site of a bacterial gene coding for a lipoprotein which triggers host innate immune response so that repression of the transcription of this gene promotes the virulence of F. novicida (24). These findings are supported by comparative genomic analysis that revealed the presence of putative scaRNAs in 16 diverse type II CRISPR-Cas systems (25). Similarly, a CRISPR-like RNA encoded between the CRISPR array and the cas genes in the I-B locus of the archaeon Haloferax volcanii has been shown to repress transcription of several non-cas genes, in particular, three genes encoding zinc transporters (26).

A distinct mechanism based on transcription repression by a cr-like RNA has been discovered in haloarchaeal type I-B CRISPR-Cas loci which encode a toxin-antitoxin RNA pair known as CreTA (after Cascade-REpressed Toxin-Antitoxin) and located in between cas genes (27). The CreA antitoxin RNA consists of two repeat sequences, which are divergent variants of the CRISPR repeats of this system, and a spacer that is partially complementary to the promoter of the adjacent toxin RNA gene creT (28). The CreA RNA bound to the Cascade effector complex represses the expression of the toxin CreT whereas deletion of the cas genes coding for any of the Cascade subunits results in CreT expression and subsequent cell death. In this case, the regulatory function of the crRNA-like CreA RNA provides for the persistence of the CRISPR locus in the bacterial genome.

Taken together, these diverse findings suggest that exaptation (repurposing) of cr-like (crl) RNAs for non-defense, primarily, regulatory functions, typically, based on partial complementarity between the spacer and the target, may be a more common phenomenon than appreciated in CRISPR-encoding bacteria and archaea. Therefore, we sought to identify putative regulatory crlRNAs comprehensively and to this end, searched intergenic regions in CRISPR-cas loci for sequences similar to CRISPR repeats. This search revealed the presence of evolutionarily conserved crlRNAs with predicted regulatory functions in a broad variety of CRISPR-Cas loci. This model was supported through expression of a crlRNA from a type I-F1 CRISPR-Cas system in a heterologous species which we found to facilitate repression of its target promoter without restriction of DNA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The prokaryotic genome database

A database containing 24 757 complete prokaryotic genomes with annotated Open Reading Frames (ORFs) was downloaded from the NCBI GenBank (29) in November 2021. The database contains 36 947 270 protein sequences annotated in 52 733 genome partitions. 25 999 CRISPR arrays were predicted in 11 777 genome partitions using the minCED tool (https://github.com/ctSkennerton/minced), with default parameters. Protein sequences were annotated using PSI-BLAST (30) with a 1e-4 e-value cut-off and 1e + 7 effective database size against NCBI CDD profile database (31) and previously described CRISPR-Cas protein profiles (5,6,32) used as queries.

An additional database for Cas12a using the following procedure: Cas12a profiles from the NCBI CDD profile database and previously described CRISPR-Cas protein profiles were used as queries for PSI-BLAST, with a 1e-6 e-value cut-off. The resulting set of Cas12a sequences was filtered by size to remove sequences shorter than 700 aa. The Cas12a set contained 962 sequences, and 481 genomic partitions with 10 kbp up and downstream of the cas12a gene were used for further analyses. Protein annotations and CRISPR array predictions were obtained as described above.

The prokaryotic viral database

A database containing 283 683 nucleotide sequences (both complete and partial genomes), representing 25 452 distinct species of DNA viruses, was downloaded from the NCBI GenBank (29) in July 2022. The prokaryotic viruses were selected by the taxonomy information available for the viral genomes.

Construction of genomic phylogenetic tree

Alignments of 29 universal phylogenetic markers (33) were converted to HMM profiles using HMMer (34) and used to identify the corresponding proteins in the collection of 24 757 completely sequenced genomes, available at NCBI as of November 2021. The best-scoring match in a genome was used for each profile.

HMM-induced alignments were used to calculate pairwise distances between the marker sequences as

|

where  and

and  are the sequences from two distinct genomes in the i-th COG and

are the sequences from two distinct genomes in the i-th COG and  is the BLAST score of the alignment of the two sequences. The exponent 0.57 was chosen to minimize the taxonomy incongruence of the tree relative to the NCBI taxonomy (https://github.com/ncbi/tree-tool).

is the BLAST score of the alignment of the two sequences. The exponent 0.57 was chosen to minimize the taxonomy incongruence of the tree relative to the NCBI taxonomy (https://github.com/ncbi/tree-tool).

The distances  for each COG were divided by their median across all pairs of genomes in this COG, giving the normalized distances

for each COG were divided by their median across all pairs of genomes in this COG, giving the normalized distances  . Then the combined distance

. Then the combined distance  between two genomes was calculated as the weighted mean of the normalized COG-specific values, i.e.

between two genomes was calculated as the weighted mean of the normalized COG-specific values, i.e.  . The weights

. The weights  for the i-th COG were defined as

for the i-th COG were defined as

|

with the variance calculated across all pairs of genomes (i.e. the COGs where the measures for each genome pairs are in better agreement with the global measure have lower variance and therefore contribute more to the global measure). The equations for all pairs of genomes were solved numerically by iterating from the initial point of  until convergence.

until convergence.

The genome distance tree was inferred using the tree-tool software (https://github.com/ncbi/tree-tool) and rooted between Archaea and Bacteria.

Phylogenetic analysis of cas genes

Phylogenetic analysis of cas genes was performed as previously described (6). Briefly, initial sequence clusters were constructed using MMseqs2 (35) using a 0.5 sequence similarity threshold. Sequences representing each cluster were aligned using MUSCLE5 (36), and cluster-to-cluster similarity was calculated using HHSEARCH (37). A UPGMA dendrogram was constructed using obtained scores. For sequences in cluster alignments, sequence-based trees were constructed using FastTree with the WAG evolutionary model and gamma-distributed site rates, and rooted by mid-point (38).

CRISPR-cas genomic islands

CRISPR-Cas islands were assembled by selecting all ORFs annotated with Cas protein profiles (5,6,32), all ORFs located between the cas genes (but no more than 10 consecutive non-Cas ORFs, and 10 consecutive ORFs up and downstream of the first and last cas gene. Predicted CRISPR arrays were mapped in the respective islands using the coordinates predicted by the minCED tool described above. CRISPR-Cas types and subtypes for each island were assigned according to previously described procedures (6).

CRISPR-Cas islands for type V from the NT genomic database were constructed in a similar manner. Coordinates of cas12 genes in NT genomic sequences were identified using PSI-BLAST with a 1e-6 e-value cut-off and previously described Cas12 profiles (6) used as queries. All ORF coordinates in 10kbp up/downstream regions of Cas12 were retrieved and annotated as described above.

Search for repeat-like sequences

Repeat-like sequences were detected using BLASTN (30) with the following parameters: reward 3, penalty -2, gapextend 5, gapopen 5, word_size 6, dust set to ‘no’, and e-value 10. For each locus containing at least one CRISPR array, repeat sequences from that array(s) were used as queries against the DNA sequence of the entire locus. All BLASTN hits containing <16 matching nucleotides were discarded. This threshold was chosen in order for the method to be sensitive enough to detect divergent repeats. Detected repeat-like sequences not overlapping with ORFs and CRISPR arrays were mapped to CRISPR-Cas loci with a POT_RNA (Potential RNA) label. Two repeat sequences separated by 15–60 bp were considered mini-arrays. All arrays containing more than two repeats were considered complete CRISPR arrays and were excluded from the analysis.

Mock repeat sequences were sampled from the intergenic regions outside of CRISPR-Cas loci from the same genomic partitions. A mock sequence of the same size as the CRISPR repeat was selected for each repeat sequence. Mock sequences were used as queries for BLASTN in the same way as the repeats, and the same filtering procedure was applied. Random loci were selected from the same genomic partition by randomly picking a portion of this partition of the same size as the CRISPR-Cas locus.

CRISPR-Cas type II tracrRNA contains anti-repeat sequences indistinguishable from other repeat-like sequences in this pipeline. Most of them are labelled as POT_RNA in provided type II genomic islands.

BLASTN search was used to find repeats in the viral database using 5148 unique CRISPR repeats from all arrays identified in the CRISPR-Cas loci. The same BLASTN as parameters described above were used, except that dbsize parameter was set to 50000 to correct e-value expectation. After this all the hits were filtered using 0.8 repeat identity and coverage. To take into account that mini-arrays in host genomes had one highly divergent repeat, repeats hits with 16bp matches were added to the set if they are located in vicinity of 0.8 identity hits, but not farther than 80bp and not closer than 15bp. To search for similar mini-arrays between prokaryotic hosts and viruses, the full sequences including both repeats and spacer were used as BLASTN query vs viral database. 0.8 identity and coverage filtering was applied to all hits.

Search for target sequences

30 bp flanking regions of the repeat-like sequences were collected as potential spacers and used as BLASTN queries with word_size 6, dust set to ‘no’, and e-value 10 parameters against the entire CRISPR-Cas locus. Given the relaxed complementarity requirements demonstrated for regulatory activities of cr-like RNAs CRISPR-Cas activity (22,27), each possible target (protospacer-like) sequence was reviewed manually for the selected cases.

We searched for spacer matches in CRISPR-Cas intergenic regions containing the spacers' ends (Supplementary file 1 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995), prioritizing the portion of the spacer located next to the repeat with higher similarity to the CRISPR array repeat because this portion of the spacer typically contains the seed sequence (9,10,39).

To search for viral mini-array spacer targets we used sequences between mini-array repeats as queries against all bacterial and archaeal genomes in which CRISPR repeats had BLASTN hits into viral mini-arrays. The same BLASTN parameters were used as described above to find all viral mini-arrays spacers in the selected genomes, then all hits were filtered by the CRISPR-cas islands coordinates: intergenic only, excluding CRISPR and mini-arrays (Supplementary Figure S1A), mini-arrays only (Supplementary Figure S1B) and CRISPR spacers or repeats coordinates (Supplementary Figure S1C and S1D). To analyze viral spacer hits in prokaryotic mini-arrays BLASTN hits were filtered by the mini-array coordinates, 0.6 spacer identity and coverage with at least 12 matches required between the spacer and protospacer, and all the hits into mini-array repeats were filtered-out as well. The finalized list of hits can be found in the Supplementary Table S1.

Weights calculation

To address the sampling bias of the genomic database, weights were derived from the phylogenetic genome tree and UPGMA tree of cas effectors according to the previously described procedure (40). A total weight of 1 was assigned to each tree, and then, distributed to all subtrees proportionally to the sum of branch lengths. The procedure was repeated recursively for all subtrees.

Anti-CRISPR protein search

All unknown genes neighboring viral mini-arrays were used as BLASTP queries against all sequences in Anti-CRISPRdb v 2.2 (41) using default parameters. Additionally, these sequences were searched with HHpred (37) using default parameters against the PDB_mmCIF30_10_jan database.

Bacterial culture conditions

Cultures were grown in 5 ml of LB in tubes incubated at 37°C on a roller for aeration. Appropriate antibiotics were provided for maintenance of plasmid expression constructs at the following concentrations: 100 μg/ml carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml spectinomycin, and 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol. For induction of CRISPR-Cas machinery, overnight cultures of strains were back diluted to OD600 = 0.05 and grown in LB supplemented with 100 μM IPTG, 1 mM arabinose and appropriate antibiotics.

Strain construction

A nano-luciferase reporter was constructed and engineered into the Escherichia coli chromosome by integration into the Tn7 attachments site (attTn7). For construction of the nano-luciferase reporter, the promoter region of the predicted regulatory region of the cas gene operon was synthesized as a gBlock by IDT and integrated upstream of the nLuc reporter gene using overlap PCR. The reporter construct was cloned between the Tn7 end sequences in the pMS26 Tn7 shuttle vector, confirmed by nanopore full plasmid sequencing, and used to deliver the reporter construct into the attTn7 site as described previously (42). Briefly, the shuttle construct was transformed into E. coli strain BL21-AI (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific), and colonies were selected for the plasmid backbone marker, carbenicillin resistance, on LB plates at 30°C. Colonies were then passaged on LB plates without antibiotic at 42°C for curing of pMS26 Retention of the reporter construct within the chromosomal attTn7 site was confirmed through luminescence measurements on a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader.

CRISPR-Cas expression constructs (Supplementary Table S2) were transformed into BL21-AI and the derivative (Strain ZB177) constructed above by electroporation. For generation of novel crRNA expression constructs (Supplementary Table S3), new guides were generated through ‘round-the-horn’ site directed mutagenesis (OpenWetWare (43)), using pOPO374 as a template. Briefly, pOPO374 was linearized with primer introduced ends through PCR by Q5 polymerase (NEB). The resulting PCR product was then circularized by treatment with PNK (NEB) and T4 ligase (NEB) in an overnight reaction at 16°C.

Nanoluciferase assay

For induction of CRISPR-Cas machinery, overnight cultures of strains were back diluted to OD600 = 0.05 and grown in LB supplemented with 100 μM IPTG, 1 mM arabinose, and appropriate antibiotics. Following induction of reporter strains, cultures were grown for 2hr. Each culture was then sampled by mixing 80uL of culture with 80uL of DI water and 80uL of Nano-Glo Luciferase Assay System reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI). Luminescence signals were measured using a BioTek Synergy H1 microplate reader and then normalized using OD600 measurements as a proxy for cell density.

Transformation efficiency assay

The transformation efficiency assay was adapted from previous protocols (44,45). For induction of CRISPR-Cas machinery, each replicate overnight culture was back-diluted into two 20 ml cultures and grown to OD600 = 0.4 (approximately 2 h under our conditions). Cultures were transferred to 50 ml conical tubes and spun down at 10 000 × g at room temperature for 2 min. The supernatant was removed, and pellets were washed twice with 12 ml of 1 M sucrose solution kept at room temperature. Each pellet was then resuspended in 300 ul 1 M sucrose. For transformation, 100 ul of cells was mixed with 1 ng of plasmid in 1 ul of water. The entire mixture was transferred to a room temperature 2 mm electroporation cuvette (Thermo-Fischer), and electroporated using a MicroPulser Electroporation Apparatus (BioRad) under appropriate settings (2.5 kV). Cells were immediately suspended in 1 ml LB and allowed to recover for 1 h at 37°C rolling incubation. For enumeration, cultures were plated on 100 μg/ml carbenicillin, 100 μg/ml spectinomycin, 30 μg/ml chloramphenicol and 0.2% glucose LB agar plates and incubated overnight at 37°C for colony growth for transformation efficiency calculation.

Data availability

All the data used for this work is available in the Supplementary Material. and as Supplementary files uploaded to Zenodo: https://zenodo.org/record/7932995.

RESULTS

Widespread standalone repeat-like sequences in CRISPR-cas loci

We built a bioinformatic pipeline (Figure 2) to identify all sequences similar to CRISPR repeats in each genome encoding at least one CRISPR-Cas system (Supplementary file 2 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). In this procedure, we searched for repeat-like sequences in the intergenic regions of CRISPR-cas loci using permissive BLASTN parameters with an e-value set to 10 and word size set to 6, in order to identify even highly divergent repeat-like sequences. Intergenic regions of the same length as repeats but located outside CRISPR-cas loci were randomly sampled, and these mock repeats were used to estimate the background of false positives. Compared to the mock repeats, CRISPR repeat-like sequences were found to be substantially enriched in intergenic regions of CRISPR-cas loci, but conversely, depleted in intergenic regions from the rest of the genomes (Figure 3A). To assess the significance of this enrichment, we performed bootstrap resampling of the set of repeats which showed that, in each of the 1000 samples, the number of repeat hits into intergenic regions of CRISPR-cas loci exceeded that in each of the three controls, at both medium and high repeat coverage (P < 0.001, Supplementary Table S4). We also detected depletion of CRISPR repeat-like sequences in cas genes compared to randomly sampled non-cas genes (Figure 3B).

Figure 2.

Computational pipeline for analysis of CRISPR repeat-like sequences. The pipeline was designed to search for sequences similar to CRISPR repeats outside of CRISPR arrays and predict their possible functions. Cas genes are schematically shown with arrows, and repeat-like sequences are shown with gray boxes.

Figure 3.

CRISPR repeat-like sequences in the CRISPR-cas neighborhoods. The number of BLASTN hits for four sets of repeats and mock repeats is plotted against the repeat coverage fraction. Repeat coverage is the length of the sequence detected with BLASTN divided by the query repeat length. (A) Repeat-like sequences in intergenic regions. The plot shows the number of BLASTN hits in the CRISPR-cas intergenic regions and intergenic regions of 10 flanking upstream and downstream genes. (B) Repeat-like sequences in protein-coding genes. The number of BLASTN hits in the open reading frames of the CRISPR-Cas loci including 10 flanking upstream and downstream genes is shown.

We further compared the number of repeat-like sequences in intergenic regions between genomes from the same genus and family that either contain or lack CRISPR-cas loci (Supplementary Figure S2). In CRISPR-negative genomes, the number of repeat matches was not significantly different from the number of matches to mock repeats, regardless of the phylogenetic distance between the CRISPR-positive and CRISPR-negative genomes. Thus, the excess of repeat-like sequences (Figure 3A) appears to be tightly linked to the presence of an active CRISPR-Cas system encoded in the respective genome, suggestive of dynamic generation and loss of ectopic copies of repeats.

Case by case examination of the standalone repeat-like sequences showed that many of them are partially degraded, prompting us to select a 16 bp match threshold for considering a BLASTN match located within a CRISPR-Cas locus but outside the array a repeat-like sequence. The search for repeat-like sequences showed significant excess in intergenic regions of CRISPR-cas loci for types I, II, III and V, but not types IV and VI (Supplementary Figure S3). All type II and some type V subtypes encode a tracrRNA which (largely) accounts for the excess of repeat-like sequence in the respective loci (19). However, for types I and III and subtype V-A, only anecdotal observations of repeat-like sequences outside CRISPR arrays have been reported so far (see Introduction above). Thus, considering the substantial and significant excess of repeat-like sequences in those CRISPR-cas loci (Figure 3A and Supplementary Figure S3), we analyzed these in detail.

Location of repeat-like sequences in CRISPR-cas loci

We first examined the locations of the detected repeat-like sequences in the intergenic regions within CRISPR-Cas loci (Supplementary Table S5). As expected, a large excess of repeat-like sequences was observed adjacent to the cas9 gene in type II loci, with up to 89% of cas9 genes flanked by a repeat-like sequence in type II-A loci, which reflects the presence of the anti-repeat in tracrRNAs. In addition, there was a pronounced peak of the number of repeat-like sequences in the vicinity of the cas3 gene of the I-E, I-D, and I-F1 CRISPR-Cas loci. Repeat-like sequences were detected in 25–29% of the upstream or downstream untranslated regions of cas3 (Supplementary Table S5). Repeat-like sequences were enriched also in the vicinity of the cas6 gene (27%) in type I-B loci. Type III loci showed no significant enrichment of repeat-like sequences between cas genes. However, an excess of repeats was apparent in flanking regions of the type III cas operons (Supplementary Figure S3, Supplementary File 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995).

The detected repeat-like sequences in type I systems were located in long intergenic regions (Supplementary File 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). We therefore examined the distribution of intergenic distances between cas genes in type I and III CRISPR-Cas loci to identify regions that might harbor RNA genes. Among the type I loci, there was a notable excess of long intergenic distances (>200 bp) between cas3 and cas8 genes in I-E (20% of the loci) and I-F1 (28%), between cas3 and cas10d (18%) in I-D, and around cas6 in I-B (33% upstream, 15% downstream) (Supplementary Figure S4A, B). In contrast, type III systems typically encompass no long untranslated regions between cas genes (Supplementary Figure S4C, D). These observation correlates with the location of repeat-like sequences in these two CRISPR-Cas types as described above.

Potential regulatory mini-arrays in class 1 CRISPR-cas systems

We mapped the detected repeat-like sequences on the phylogenetic tree of Cas3, in order to identify clades where this feature was conserved and examined these in greater detail (Supplementary file 4 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). Some Cas3 sequences, in particular, those from the I-B and I-D systems, formed branches enriched with the repeat matches, whereas in I-E and I-F1 loci, the repeat-like sequences were spread uniformly, again, suggesting that the formation of stand-alone repeats is a common phenomenon occurring sporadically in many of these CRISPR-cas loci. A more detailed examination showed that intergenic regions in many of these loci contained mini-arrays consisting of two repeat-like sequences, the one upstream of the spacer-like sequence being similar (but not necessarily identical) to the query CRISPR repeat, whereas the downstream one was more degraded (Figure 4, Supplementary file 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). In many cases, the degraded distal repeat was not detected using BLASTN and could be identified only by manual search.

Figure 4.

Putative regulatory mini-arrays in CRISPR-cas loci. Cas genes are shown as block arrows, repeats are shown as grey boxes annotated with SRU, and targeting sequences (mini-array spacers) and their predicted targets are shown with orange boxes. The locus description includes information on the CRISPR-Cas type, accession for Cas3, nucleotide contig identifier, and start and stop positions of the CRISPR-Cas locus. (A) Examples of mini-arrays in I-E, I-F1, I-D and I-B locus. For comparison, a typical I-E locus that lacks room for an additional RNA gene is shown. (B) Detailed organization of a I-E locus containing a mini-array. Green, promoter region; blue box, CRP and H-NS repressor binding sites identifies for type I-E in E.coli (50,51); pink box, LeuO activator sites (52). Sequence regions are color coded as follows: grey, repeat-like sequences; blue, binding sites for H-NS and CRP repressors; orange, spacers and potential targets; green, promoter region. The actual sequence of the mini-array and the predicted duplex between the spacer in its crRNA-like transcript and the cas8 gene promoter is shown underneath the schematic. (C) Organization of a I-F1 locus containing a mini-array. Designations are the same as in B. The actual sequence of the mini-array and the predicted duplex between the spacer in its crRNA-like transcript and the cas8 gene promoter is shown underneath the schematic. D) A mini-array in an archaeal genomic locus containing both a I-B and a III-C system.

The majority of the repeats in CRISPR arrays are almost identical, however tending to degenerate toward the distal end. To determine whether the mini-arrays had a similar pattern of mismatches compared to the CRISPR array from the respective locus, we analyzed 38 sets of cognate mini-arrays: 23 sets of mini-arrays associated with type I-E (Figure 4) and 15 sets of mini-arrays associated with type I-D (Figure 6, Supplementary Figure S5, Supplementary file 5 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). This analysis shows that both repeats in mini-arrays are typically more variable than repeats in CRISPR arrays and preserve only the stem-loop region (Supplementary Figure S5). Compared to the distal repeat of the mini-array, the 3’ end of the proximal repeat tends to be more conserved, whereas the stem-loop is more conserved in the distal repeat (Supplementary Figure S5B). The distribution of mismatches vs the array consensus along the length of both copies of the mini-array repeats appears different from that for the distal repeat of the CRISPR array, suggesting different formation mechanisms (Supplementary Figure S5, Supplementary file 5 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995).

Figure 6.

Type I-D CRISPR-cas loci containing mini-arrays implicated in the regulation of cargo genes transcription. (A) Cas3 clade with cargo genes located between Cas3 and Cas10. (B) Cas3 clade with cargo genes located upstream of the CRISPR-Cas locus. The tree topologies for the two clades of Cas3 tree are shown on the left. Protein-coding genes are shown as block arrows, CRISPR arrays are shown as gray boxes for repeats and green diamonds for spacers, and mini-arrays are shown with gray boxes for repeats, and targeting sequences (mini-array spacers) and their predicted targets are shown as orange boxes. Cas3 protein accession numbers and the organism names are indicated. Purple circles indicate the presence of a mini-array in the respective locus. For each tree leaf, the locus containing cargo genes is shown.

Only 12 cases of short arrays consisting of three and more repeats were identified (Supplementary file 2 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). The rarity of such short arrays is likely due to the absence of the region of the CRISPR leader that is required for spacer acquisition that results in repeat proliferation (46–48). The repeats in intergenic regions are typically separated by a 20–60 bp spacer (Supplementary file 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995), within the characteristic range of spacer lengths in CRISPR arrays (Figure 4). Apart from the mini-arrays, many isolated single repeat units (SRU) were detected (Supplementary file 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995) resembling those detected previously in the genomes of some bacterial and archaeal viruses (49). SRUs contain a single repeat that is (nearly) identical to the repeats in the associated CRISPR array and appear to lack the downstream repeat, although some of these could represent mini-arrays in which the distal repeat deteriorated beyond recognition.

Previously discovered mini-arrays in the scaRNA and creTA loci are involved in the repression of FTN_1103 (uncharacterized lipoprotein) (25,53) and creT (28) genes, respectively. The regulatory activity of crlRNAs in these cases as well as in the case of tracr-L required a partial, imperfect match between the spacer and the protospacer (22,24,28). Therefore, we searched for partial (10 bp or longer) matches between the mini-array spacers and potential targets, taking into account the importance of the 5’-terminal seed region of the spacer (9,54) (see Materials and Methods). This search revealed putative targets located in the promoter region of the cas8 gene of I-E and F1 systems, cas10d gene for I-D, and the cas6 gene for type I-B, suggesting that the transcript of the mini-array is a regulatory crlRNA that represses the transcription of the respective cas genes (Figure 4). For all manually examined cases, we found that the predicted target sequence was flanked by the corresponding PAM (Figure 4B, C) (55,56). Furthermore, the seed region of the targeting sequence was adjacent to the repeat-like sequence with the higher similarity to the CRISPR repeat, indicating that the mini-array is transcribed in the opposite direction to the cas3 gene. It should be noted that the presence of mismatches in the sixth position of the spacer is consistent with previous findings with other I-F1 systems where every sixth position of the spacer was found not to contribute to base-pairing with the target (57,58). The predicted target sequence was located downstream of the mini-array, adjacent to a corresponding, canonical PAM, namely, AAG for I-E in E. coli (9) and CC for I-F1 in Pseudomonas aeruginosa (55). Notably, in the E. coli I-E locus, the predicted target sequence overlaps the binding site of the H-NS repressor (50,59,60) (Figure 4B), which is located immediately upstream of the Pcas promoter (50), and the likely transcription start region of the mini-array overlaps the binding sites for the transcription activator LeuO (52) and cAMP receptor protein (CRP) (51). By contrast, we did not detect integration host factor (IHF) binding site in the leader sequence of the mini-array, which is required for the spacer incorporation into the I-E CRISPR array in E. coli (51). Thus, the mini-array could serve as an additional regulator of the CRISPR-Cas system, in the absence of the H-NS repressor. We did not detect any additional potential targets with both a valid PAM and a conserved seed region for the cases we examined in detail (Figure 4B, C, Supplementary file 1 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). However, given that only a short matching region between the spacer and their targets is required for regulation, it is impossible to rule out that other targets elsewhere in the genome are regulated by the mini-arrays.

Mini-arrays were detected in ∼15% of the archaeal CRISPR-cas loci and ∼12% in bacteria (Supplementary Table S6). Subtype I-B in archaea includes ∼17% mini-array containing loci, which is similar to ∼19% in bacteria. By contrast, archaeal subtype I-E systems contain fewer mini-arrays than bacterial I-E (∼8% versus ∼19%). Further, among archaeal subtype I-A loci, ∼10% contain mini-arrays, whereas no mini-arrays were found in subtype I-A in bacteria. However, in many archaeal genomes, different types of CRISPR-Cas systems cluster together (Supplementary file 4 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). In the example shown in Figure 4D, adjacent I-B and III-C loci are separated by an intergenic region which contains, upstream of the cas7 (cmr1) gene, a potential target sequence for a mini-array located in the vicinity of the CRISPR-cas locus. This arrangement suggests regulation of the III-C system either by its own effector or by the I-B effector complexed with the cr-like RNA. CRISPR-cas loci with two or more co-located systems contain more mini-arrays, ∼16% in bacteria and 21% in archaea, compared to the loci with only one system, ∼11% and 13%, respectively. Most notably, ∼37% of the composite loci that include subtype I-B in archaea contain mini-arrays, in contrast to only ∼13% of the loci encompassing I-B systems only. These observations suggest that the composite loci, in which different types of CRISPR-Cas systems are likely to cooperate, are subject to complex regulation to which mini-arrays are likely to contribute.

Mini-arrays were found also outside of but close to the CRISPR-cas loci in 10–16% of type III systems (Table 1). In these cases, the mini-arrays were located close to the CRISPR array, similarly to the type I-B architecture (Supplementary file 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). However, no conservation of the mini-array positions in closely related genomes was observed, no clades of the Cas10 tree enriched with repeat-like sequences were identified, and no potential targets were detected (Supplementary file 6 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). Thus, it appears likely that in type III systems, the mini-arrays are degraded, non-functional CRISPR repeats.

Table 1.

Repeat-like sequences outside arrays and mini-arrays in CRISPR-Cas systemsa

| CRISPR-Cas type/subtype | Number of loci | Fraction of loci with at least one repeat outside the array | Fraction of loci with at least one mini-array |

|---|---|---|---|

| I-A | 139 | 0.43 | 0.06 |

| I-B | 1243 | 0.51 | 0.18 |

| I-C | 1206 | 0.34 | 0.07 |

| I-D | 128 | 0.49 | 0.15 |

| I-E | 3741 | 0.53 | 0.19 |

| I-F1 | 1145 | 0.40 | 0.15 |

| I-F2 | 33 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| II-A | 1013 | 0.94 | 0.05 |

| II-B | 80 | 0.95 | 0.11 |

| II-C | 1167 | 0.76 | 0.06 |

| III-A | 597 | 0.39 | 0.10 |

| III-B | 451 | 0.42 | 0.12 |

| III-C | 65 | 0.32 | 0.10 |

| III-D | 309 | 0.44 | 0.16 |

| I-G | 235 | 0.46 | 0.04 |

| IV-A | 166 | 0.06 | 0.00 |

| IV-C | 3 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| V-A | 43 | 0.49 | 0.15 |

| V-B | 18 | 0.36 | 0.00 |

| V-C | 10 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| VI-A | 9 | 0.63 | 0.10 |

| VI-B | 38 | 0.37 | 0.15 |

| VI-C | 7 | 0.33 | 0.00 |

| V-A NT | 335 | 0.56 | 0.04 |

aThe weighted fraction of the loci containing standalone repeat-like sequences and mini-arrays is shown for all CRISPR-Cas types identified in the genomic database. Data for subtype V-A included additional loci retrieved from the NT database.

Validation of cascade expression regulation by a I-F1 mini-array

Apart from the intergenic regions that frequently harbored mini-arrays, the latter were found sporadically in other regions of CRISPR-cas loci. One such sporadically occurring standalone mini-array was identified in I-F1 systems of P. aeruginosa. The extensively characterized I-F1 system from the UCBP-PA14 strain (hereafter PA14 I-F1) lacks a mini-array between cas3 and the Cascade operon, but mini-arrays were found in systems with nearly identical coding sequences (Figure 5A). The near identity of the cas genes in these systems to those of PA14 I-F1 allowed us to probe the function of the P. aeruginosa crlRNA transcribed from the mini-array. We generated a luminescence reporter construct by cloning the promoter region of P. aeruginosa strain YL84’s Cascade operon 5’ of a nanoluciferase (nLuc) gene (Figure 5B). Taking advantage of the existing heterologous expression constructs for the PA14 I-F1 CRISPR-Cas system components (61,62), we assayed the ability of the mini-array to repress nLuc expression, as measured by relative luminescence.

Figure 5.

The mini-array from a type I-F1 CRISPR-Cas system functions as a regulatory guide RNAs that is not used for interference. (A) Gene track alignment of the I-F1 CRISPR-Cas systems from P. aeruginosa strains UCBP-PA14 and YL84. CR is CRISPR mini-array. The predicted target for the mini-array spacer is labeled with a * and the YL84 Cascade operon promoter is denoted with an arrow. (B) Diagram of a synthetic nanoLuciferase (nLuc) reporter for the YL84 cascade operon. The target sequence is depicted in blue and denoted with a ‘*’, the –35 and –10 sequences are shown as black boxes. (C) Relative luminescence assay showing the activity of a nanoluciferase gene placed under the YL84 cascade operon promoter in the presence of variable PA14 I-F1 CRISPR-Cas system components; RLU, Relative Luminescence Unit. (D) Predicted pairing interactions of the YL84 mini-array target with the YL84 mini-array spacer, and a canonical spacer against the same sequence. The PAM complementary sequence is bolded. Every sixth position is expected not to form a base pair, and is depicted in red. Differences in the region 3’ of the spacer sequence are underlined. (E) Relative luminescence assay showing the activity of a nanoluciferase gene placed under the YL84 cascade operon promoter in the presence of the PA14 cascade complex and variable crRNA guides. In addition to a no RNA control and the YL84 crlRNA RNA, targeting and non-targeting canonical crRNAs were also tested. (F) Transformation assay showing plasmid transformation efficiency relative to a non-targeted permissive plasmid. The transformation efficiency of plasmids bearing the YL84 regulatory target or a control target was assayed in strains expressing regulatory, control, or inhibitory crRNA guides as well as PA14 cascade and Cas3. LQ, Limit of Quantification, indicating no colonies were recovered, or the number of colonies was fewer than would allow for quantification below this level of efficiency.

The Cascade complex and mini-array transcript (crlRNA) were required to repress the nLuc expression, whereas Cas3 and Cas1 were dispensable (Figure 5C). This finding is consistent with the previous reports that the Cascade complex and crRNA guide are sufficient for target binding whereas Cas3 is recruited after target binding to cleave the target DNA (63). Furthermore, the crRNA-guided Cascade complex of the PA14 I-F1 system can transcriptionally silence targets in the absence of Cas3 (64).

The spacer of the predicted crlRNA transcribed from the mini-array is shorter than the spacer in a regular crRNA, and differs from the latter in the region between the spacer and the hairpin (Figure 5D). The mini-array RNA also contains mismatches in positions 6 and 12 of the spacer, but in I-F1 systems, every sixth nucleotide is known not to contribute to base pairing (57,58), suggesting that the mini-array spacer has the same level of complementarity as a canonical spacer but covering a shorter sequence. In this case, the shorter spacer likely precludes cleavage as demonstrated for a minimal type I-F CRISPR system (65). We compared transcription repression by the crlRNA and canonical targeting and non-targeting crRNAs in the absence of Cas3 (Figure 5D,E). As expected, a control guide lacking complementarity to the target region was unable to repress nLuc expression. The YL84 crlRNA and a canonical crRNA guide matching the target region caused similar levels of transcription repression (Figure 5F), suggesting that the unusual features of the repeat and spacer of the crlRNA (Figure 5D) prevented cleavage of the target but neither enhance nor diminished transcriptional repression.

Using a transformation interference assay, we tested the difference in plasmid transformation interference between the YL84 crlRNA and the canonical inhibitory guide (Figure 5F). Neither of these guides restricted transformation of a plasmid carrying a control target, whereas only the canonical guide restricted the YL84 Cascade promoter target. This result indicates the crlRNA combined with Cascade is unable to trigger target cleavage, suggesting that the unusual features of the mini-array-encoded crlRNAs are adaptations that prevent self-cleavage of the CRISPR-Cas locus.

Cargo gene regulation by mini-arrays

In addition to the potential regulation of cas genes, we detected multiple cases of potential regulation of additional genes located within or in the close proximity of CRISPR-cas loci (hereafter cargo, to emphasize the lack of obvious connections to the CRISPR-Cas functions). We identified two clades in the Cas3 tree corresponding to I-D systems with mini-arrays present in multiple loci. In both groups of loci, toxin-antitoxin (TA) modules, transcriptional regulators, and some other genes were located downstream of the mini-arrays and upstream of the cas10d gene (Figure 6). Potential target sequences were identified upstream of these cargo genes, within the likely promoter regions (Figure 6, Supplementary file 7 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). Notably, these portions of the CRISPR-cas loci varied in their gene content, apparently representing hotspots of gene shuffling (Figure 6). In particular, loci lacking the cargo genes but retaining a mini-array as well as ‘empty’ loci lacking both the cargo and the mini-array were often found in relatives of species carrying the cargo (Supplementary files 3 and 4 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). Notwithstanding the variability, these two distinct Cas3 clades showed generally similar cargo content enriched in TA and other potential defense and regulatory genes (Figure 6A, B). The sequences of spacers and potential targets and the location of the latter within the intergenic region varied but the position of the mini-array itself was conserved (Supplementary file 7 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). We then checked if there was an excess of any particular type of defense systems in the CRISPR-cas loci and found that TA genes were significantly enriched in the regions between the mini-arrays and the cas genes (Supplementary Table S7, Supplementary Figure S6). Among the CRISPR-Cas systems, the most pronounced enrichment of TA was observed in I-B, I-E, I-F1 and I-D (Supplementary Table S7). These findings are in accord with the previous qualitative observations on association of TA with CRISPR loci (66) and suggest that regulatory circuits coordinating the activities of TA and CRISPR-Cas systems and preventing the loss of the latter, similar to the CreTA mechanism (27), are widespread and involve diverse TA.

Standalone repeat-like sequences in class 2 CRISPR-cas loci

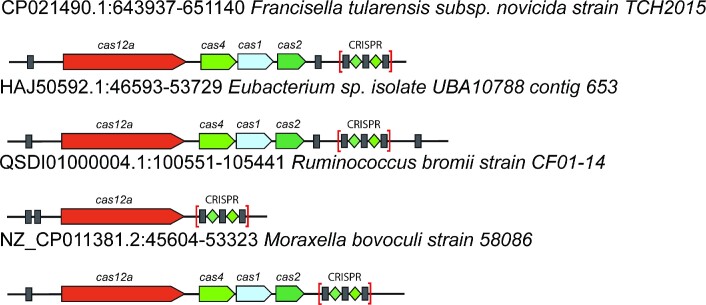

A hallmark of type II CRISPR-Cas systems is the tracrRNA that is encoded within the CRISPR-cas loci and contains an anti-repeat (17,19). In our dataset, we identified repeat-like sequences in intergenic regions of 82% of the Type II loci (Table 1, Supplementary Table S6), and 76% of these were located adjacent to cas9 (Supplementary file 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). Apart from CRISPR and tracrRNA, several type II loci also contain scaRNA, a standalone regulatory mini-array (24,53),(25). We focused on mini-arrays distinct from tracrRNA that were detected in ∼6% of Type II loci, which is significantly lower than the mini-array prevalence in types I and III (∼15% and ∼12%, respectively) (Supplementary Table S6). In some type V systems, such as subtype V-B, tracrRNA has been identified and shown to be essential for crRNA maturation and interference (18,20,67). However, the most thoroughly characterized and abundant subtype V-A loci do not encode tracrRNA or scoutRNA (68),(21). Surprisingly, we identified repeat-like sequences in ∼49% of V-A loci, mostly, located upstream of the cas12a gene (Table 1, Supplementary file 3 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). To expand on this observation, we supplemented the analyzed data set with additional type V-A loci from the NT NCBI database and found that ∼56% of the V-A loci contained standalone repeat-like sequences, and in ∼34%, these sequences were adjacent to cas12a (Figure 7; Table 1, Supplementary Table S6; Supplementary file 8 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). Phylogenetic analysis of Cas12a identified several clades in the tree, such as Francisella, Moraxella, Ruminococcus and Eubacteriales, where repeat-like sequences were conserved (Figure 7, Supplementary file 9 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). In most of these loci, we identified SRUs but no mini-arrays. The search for possible spacer-like sequences upstream or downstream of the SRU did not reveal any conserved targeting pattern either. Furthermore, the level of identity between the CRISPR repeats and the SRU was relatively low, close to the detection threshold (Supplementary file 2 at https://zenodo.org/record/7932995). In Francisella hispaniensis genomes, we identified a locus with the same upstream and downstream genes as in the V-A loci in other Francisella species, but without cas genes or a CRISPR array (Supplementary Figure S7A). The nucleotide sequence alignment of the intergenic regions between V-A positive and negative Francisella genomes showed that the latter contained the SRU adjacent to the last divergent repeat of the missing CRISPR array (Supplementary Figure S7B). Apparently, the degenerate repeat and the SRU represented the remnant of the lost CRISPR-cas locus that could be a target for recombination leading to recapture of the CRISPR system. The high prevalence and evolutionary conservation of the SRUs strongly suggest that they perform specific functions in V-A systems. As suggested previously for SRU identified in virus genomes (49), the short RNAs containing these sequences might bind and inhibit the cognate CRISPR effectors, mimicking the regulatory role of tracr-L and mini-arrays through a distinct mechanism.

Figure 7.

Repeat-like sequences in subtype V-A CRISPR-cas loci. Examples of loci containing SRUs from the Francisella, Moraxella, Ruminococcus and Eubacteriales cas12a branches. Cas genes are shown as arrows, SRUs are shown as grey boxes, CRISPR arrays are shown as gray boxes for repeats and green diamonds for spacers; mini-arrays are shown with gray boxes for repeats, and targeting sequences (mini-array spacers) and their predicted targets are shown as orange boxes. The locus description includes locus contig, start and stop positions, and the organism name.

Mini-arrays in viral genomes

As shown previously, CRISPR mini-arrays are present in the genomes of some bacterial and archaeal viruses (49). The spacers of these viral mini-arrays mostly target other virus genomes and appear to be involved in superinfection exclusion (49,69). However, considering the apparent regulatory roles of the bacterial and archaeal mini-arrays, we sought to determine whether viruses also employ mini-arrays to suppress the expression of cas genes in infected host cells. To this end, we searched for (nearly) identical copies of mini-arrays from bacterial and archaeal CRISPR-cas loci in viral genomes and identified 11 mini-arrays in 10 phage genomes (Supplementary Table S8). These sequences were reexamined case by case, and four mini-arrays containing spacers similar between the host and the virus were identified. Two of these were copies of mini-arrays from 11 Clostridium perfringens isolates found in Clostridium phage phiCp-D (Figure 8A). One Fusobacterium pseudoperiodonticum KCOM_2653 found in Myoviridae sp. isolate ctLpD1 metagenomic assembly. All these cases are found in subtype I-B CRISPR-cas systems and have similar architectures. The mini-array in the host genome is located upstream of the cas6 gene and appears to target a sequence between the mini-arrays and cas6, with a typical type I-B PAM. The 5’-terminal 15 nucleotides of the spacer including the seed are identical between the host and the phage mini-arrays, but the phage spacer is three nucleotides shorter. The fourth mini-array is represented in 18 Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains and Pseudomonas phage vB_PaS_IME307 (Figure 8B, Supplementary Table S8). In the host genomes, these mini-arrays are found in the typical location for I-F1 systems, between cas3 and cas8 genes, and the target is located upstream of cas8, in the predicted promoter region (Figure 4C). Similar to the mini-arrays in Pseudomonas and Clostridium phages described above, the spacer in the phage mini-array is truncated by two nucleotides. Notably, the P. aeruginosa phage encoded mini-array is located within a previously identified anti-CRISPR locus where the mini-array co-occurs with the acrIF24 and acrIF23 genes (70) (Figure 8B). One of the proteins encoded near the mini-array in Clostridium phages also showed significant sequence similarity to AcrIF23 as shown by HHpred search (37) (Figure 8A). Considering that anti-CRISPR (Acr) genes are typically clustered in virus genomes (71–73), the co-localization of the phage mini-arrays with Acrs is consistent with the crlRNAs down-regulating the host CRISPR immunity.

Figure 8.

Putative regulatory mini-arrays in phage genomes. Loci containing closely similar mini-arrays in phages and their hosts are shown. (A) Clostridium perfringens and Clostridium phage phiCp-D, (B) Pseudomonas aeruginosa YL84 and Pseudomonas phage vB_PaS_IME307. Cas genes are shown as arrows, CRISPR arrays are shown as gray boxes for repeats and green diamonds for spacers, mini-arrays are shown with gray boxes for repeats, and targeting sequences (mini-array spacers) and their predicted targets are shown as orange boxes. The locus description includes locus contig, start and stop positions, and the organism name.

Two additional examples of phage encoded mini-arrays or short arrays with high similarity to host mini-arrays were detected in prophages of M. osloensis strain FDAARGOS_1130 (CP068109.1) and Acinetobacter baumanii strains A1429 (CP046898.1) and AF-401(CP018254). In both these cases, the host genome encoded a I-F1 CRISPR-Cas system that lacked its own mini-array, but contained cas genes with a high level of sequence identity to those of systems that did encode mini-arrays (Figure 9A and B, E and F). Consistent with the mobility of anti-defense islands between phages (70) and clustering of genes encoding Acrs and mini-arrays in P. aeruginosa, the A. baumanii mini-array was found in two unrelated prophages (Supplementary Figure S8). The M. osloensis prophage short array consisted of three repeats and two largely identical spacers and occurred in a gene cluster flanked by direct repeats (Figure 9F, Supplementary Figure S9). The presence of repeats suggests mobility, but so far we identified only one copy of this array.

Figure 9.

Prophage encoded regulatory mini-arrays co-occur with cognate CRISPR-Cas systems that lack their own mini-arrays. Comparison of CRISPR-Cas system-encoded and prophage-encoded mini-arrays found in Acinetobacter baumanii (A–D), and Moraxella osloensis (E–H). (A and E) Gene track alignments of CRISPR-Cas systems with and without mini-arrays, with genes labeled and regions of high nucleotide identity indicated. CRISPR array sequence is depicted black, while the mini-array target sequence and matching spacers are depicted blue. Mini-arrays are labeled ‘CR,’ and the target sequence is denoted with ‘*’. (B and F) Prophage loci bearing mini-arrays. Mini-arrays are labeled ‘CR’ with repeats depicted black and spacers depicted blue. ‘DR’ is direct repeats. (C and G) Alignment of mini-array repeats from host CRISPR-Cas systems and prophages. Matching bases are denoted with a ‘|’. Bases predicted to form stem structures based on RNA base pairing are bolded and italicized. (D and H) Base pairing between the mini-array crRNA spacer sequences and the putative regulatory target. A putative GG PAM sequence is depicted in yellow. Base pairing is depicted with a ‘:’. Every 6th base is depicted in red.

We then ran a broader search for viral regulatory mini-arrays by identifying any CRISPR repeat-like sequences in viral genomes, which allowed identification of viral mini-arrays distinct from those present in the host. Following the previously described procedure (49), we identified 835 mini-arrays with two repeat-like sequences and 297 CRISPR arrays with three or more repeats in 1005 viral genomes (Supplementary Table S10). We then searched for matches to spacers and mock spacers, selected randomly from the same viral genomes, in the CRISPR-cas loci containing CRISPR repeats similar to those in the viral mini-arrays (Supplementary Table S10). Compared to mock spacers, sequences similar to the spacers from viral mini-arrays were found to be significantly (P < 0.002, Supplementary Table S9) enriched in intergenic regions of CRISPR-cas loci (after removing detected mini-arrays) (Supplementary Figure S1A), suggesting the presence of viral mini-array targets. Additionally, we searched for viral mini-array targets in host CRISPR arrays and mini-arrays, and found that host mini-arrays gave twice as many matches with viral spacers than with mock spacers (Supplementary Figure S1B), whereas the number of hits into CRISPR array repeats and spacers was similar for the real and mock spacers (Supplementary Figure S1C, D). Further examination identified 59 viral spacers that matched 104 host mini-array spacers above the 60% identity threshold (Supplementary Table S1). In 45 of these 104 cases, there was high identity in the seed regions, followed by divergence in the downstream portion of the spacer. In particular, 23 Clostridium perfringens mini-arrays matched similar viral spacers in three Clostridium phages (Figure 8A) and 18 Pseudomonas aeruginosa strains matched similar spacer to Pseudomonas phage vB PaS IME307 (Figure 8B), suggesting that the respective viral mini-arrays target the same cas gene promoters as the host mini-arrays.

In these cases, the CRISPR repeat sequence was conserved in positions proximal to the spacer, and the predicted upstream and downstream stem-loops were conserved as well but the nucleotide identity within the stem-loops varied (Figure 9C and G). The spacer sequences were most highly conserved within the seed region, and the sixth position within the mini-array was often a mismatch (Figure 9D and H) which is typical of I-F1 systems (57,58). The low sequence conservation within upstream and downstream stem-loops and within the spacer's non-seed positions imply that the number of regulatory crlRNAs predicted in this work is an underestimate.

Similar to the observations in A. baumanii and M. osloensis, mini-array encoding prophages in P. aeruginosa co-occurred with PA-14-like I-F1 systems that lacked their own autoregulatory spacers (Supplementary Table S11). Among both Acinetobacter sp. and P. aeruginosa I-F1 CRISPR-Cas systems, there is notable heterogeneity with respect to the presence of regulatory mini-arrays. Within a cluster of 41 related I-F1 CRISPR-Cas systems in Acinetobacter sp. genomes (the cluster defined as sequences spanning Cas3 to Cas1 having >90% nt identity and >90% coverage), ∼71% contained mini-arrays, whereas the rest encoded long arrays in their place (Supplementary Table S11). In a cluster of 244 P. aeruginosa I-F1 CRISPR Cas systems, about 15% possess a mini-array (Supplementary Table S11). The exclusive cooccurrence of prophage-encoded regulatory mini-arrays with cognate systems lacking their own mini-arrays suggests that the capture of regulatory spacers by phages selects for CRISPR systems that lack autoregulatory mini-arrays. Conceivably, mini-arrays within CRISPR-cas loci are purged by selection because they would cause excessive down-regulation of the expression of the cas genes, hampering immunity against incoming phages.

DISCUSSION

The findings presented here, along with many previous, more anecdotal observations (22,27,49,69), indicate that exaptation of CRISPR repeats for functions distinct from interference, in particular, regulation of transcription of cas and other genes, is a common feature in the evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. Arguably, the formation of standalone repeat-like sequences is facilitated by the inherent recombinogenic propensity of repeats. Random generation of standalone mini-arrays is likely to provide ample material for further exaptation. In many standalone mini-arrays, both repeats contain mismatches to the consensus of the corresponding regular CRISPR repeats, the degeneration of the distal repeat being more pronounced. This arrangement seems to suggest that the mini-arrays evolved via duplication of the terminal unit of a CRISPR array; alternatively, some mini-arrays might derive from truncation of a CRISPR array followed by re-acquisition. It should be noted, however, that detailed manual examination demonstrated a different pattern of degeneration in mini-arrays compared to the last repeats of regular CRISPR arrays. Whereas in the regular arrays, mismatches accumulated primarily in the distal portion of the last repeat, in mini-arrays, the mismatches were more evenly distributed such that it was largely the characteristic hairpin structure that remained conserved. Because of the deterioration of the distal repeat, the counts of mini-arrays presented here are likely to be underestimates. Indeed, manual examination of long intergenic regions in various type I CRISPR-cas loci resulted in the detection of mini-arrays missed by the automatic pipeline. Thus, the occurrence of long intergenic regions gives the upper bound for the number of mini-arrays.

The mini-arrays are particularly common and evolutionarily conserved in I-B, I-E and I-F1 CRISPR-Cas systems. For the spacers of many mini-arrays, likely targets were identified within the CRISPR-cas loci themselves, typically, in the promoter regions of effector genes, such as cas8. Thus, the crlRNAs produced by the expression of these mini-arrays can be predicted to form a complex with the effector and down-regulate the expression of the cas genes encoding the effector subunits, similarly to tracr-L in type II (22). Such autoregulation of the effector expression likely prevents autoimmunity and mitigates the cost of CRISPR-Cas maintenance. Additionally, such regulation could help maintain the concentration of the effector complex in the cell at a level that is optimal for immunity (74).

Along with prior work demonstrating the regulatory roles of mini-array encoded RNAs, our experimental validation of target transcription repression by a P. aeruginosa I-F1 system encoded mini-array supports the predicted regulatory roles. Currently, various types of mini-arrays that repress transcription without causing DNA cleavage (including tracr-L and scaRNA) have been experimentally characterized in I-B (26,27), I-F1 (this work), II-A (22) and II-B systems (24,53). Together with the comprehensive comparative genomic analysis described here, these results show that recruitment of the CRISPR machinery for (auto)regulation is a common phenomenon in the evolution of CRISPR-Cas systems. It is worth noting that, given the typically short distance between the mini-array and the target and the bulkiness of the Cascade complex, the crlRNA might indirectly down-regulate the expression of the mini-array itself, through steric interference with the RNA polymerase. Such autoregulation would provide for further fine-tuning of the CRISPR regulatory circuit.

In addition to the regulation of CRISPR effector expression, we found likely cases of the involvement of mini-arrays in the regulation of the expression of cargo genes, in particular, TAs, primarily, in subtype I-D systems. The analogy with the regulatory function of CreTA (27,28,75) implies that various TAs are likely involved in ‘addictive’ regulatory circuits whereby the maintenance of the CRISPR-cs locus prevents cell death caused by the toxin expression. A regulatory circuit containing a TA module regulated by the CRISPR effector also could provide an abortive infection mechanism preventing viruses from employing anti-CRISPR mechanisms that deplete effectors or impair their ability to bind crRNA which is the case of many Acrs (71,76). Any anti-CRISPR strategy that substantially depletes the pool of functional effector units could trigger toxin expression resulting in cell death or dormancy.

The case of scaRNA shows that mini-arrays can be employed also for regulation of genes located outside of the CRISPR-Cas loci and functionally unrelated to CRISPR (23–25,53) so that the respective CRISPR systems effectively perform dual functions, immune and regulatory. However, the low complementarity between the mini-array spacer and the target protospacer makes computational detection of such regulatory connections highly problematic.

In addition to the (predicted) regulatory mini-arrays in bacterial and archaeal CRISPR-cas loci, we identified similar mini-arrays in some viral genomes that appear to target promoter regions of cas genes. Thus, in accord with the general concept of the evolutionary entanglement between defense and counter-defense systems in prokaryotes (‘guns for hire’) (77), some viruses seem to employ regulatory mini-arrays as a counter-defense mechanism. In genomes of P. aeruginosa phages, regulatory mini-arrays were found within a known anti-CRISPR locus that encodes AcrIF23 and AcrIF24 (70). AcrIF24 binds the Cascade complex, preventing the recruitment of Cas3 (78–80), whereas AcrIF23 inhibits the nuclease activity of Cas3 (81). Combining these Acrs with distinct CRISPR inhibition mechanisms with a regulatory guide that down-regulates Cascade expression is consistent with a multipronged anti-CRISPR strategy that involves both inhibition of the activity of Cas proteins and prevention of further cas gene expression as recently demonstrated for phages evading type V systems (82). We observed a conspicuous anti-correlation between the presence of mini-arrays in prophages and in the CRISPR-cas loci in the respective host genomes. This is likely to be the case because the presence of identical or closely similar mini-arrays in a (pro)phage and a host CRISPR locus would result in cleavage of the latter at the homologous spacer, potentially killing the cell. Subverting mini-array regulation as an anti-CRISPR strategy by viruses would undermine the intrinsic benefits of mini-arrays, such as reduced autoimmunity. The resulting evolutionary tradeoff associated with possessing autoregulatory mini-arrays presents a plausible explanation for the observed heterogeneity of regulatory mini-array occurrence among related CRISPR-Cas systems.

The regulatory function of the mini-arrays is based on partial complementarity between the spacer and the target which appears to be an important feature in the functionality of CRISPR-Cas and perhaps other RNA-guided systems that provides for functional plasticity, safeguarding the target from cleavage. Indeed, this feature is employed for the CRISPR-mediated adaptive immunity itself, in particular, for primed adaptation where the outcome of spacer interaction with the target is toggled between cleavage and new spacer capture depending on the degree of complementarity (83,84). Furthermore, some CRISPR-systems, such as subtypes V-C and V-M, and type IV, employ partial complementarity for interference without target cleavage, via the repression of expression or replication (85–87). Furthermore, partial complementarity is sufficient for targeting RNA-guided transposition by CASTs (CRISPR-associated transposases) to specific integration sites in the host genomes (62,88,89). Thus, partial complementarity appears to be an adaptive feature supported by selection rather than, simply a result of deterioration of the complementarity between a crRNA and its target caused by evolutionary drift. Notably, target cleavage by type I CRISPR systems is highly sensitive to mismatches (83,90) whereas the cleavage by type III systems Is far more tolerant, requiring mostly the match in the seed sequence (65,91). This differences in the target specificities between type I and type III might partially explain why regulatory mini-arrays are prevalent in the former but not in the latter. Additionally, it appears that crlRNAs can be repurposed for regulatory functions by shortening the spacer. Furthermore, changes to the repeat sequences themselves, outside of the spacer region, might be important for the function of the regulatory mini-arrays similarly to the case of I-F3 CAST (88).

It seems pertinent to note that the dichotomy between small RNAs that perfectly match the target and are engaged in immunity and those with partial matches that are involved in regulation extends beyond CRISPR. Indeed, in the context of the RNA interference (RNAi) machinery that is nearly ubiquitous in eukaryotes, small interfering RNAs perfectly match the target and direct nucleases for specific cleavage of foreign nucleic acids, whereas microRNAs with limited complementarity to the target regulate gene expression at both the transcription and the translation levels (92,93). Furthermore, as in the case of CRISPR, immunity via perfect base-pairing seems to be the ancestral function RNAi whereas the regulatory functions are derived (94,95). Given the obvious ubiquity of complementary interactions between nucleic acids across biology, functional modulation by adjusting the degree of complementarity appears to be a major biological principle.

Apart from mini-arrays, numerous CRISPR-cas loci contain SRUs. In many if not most cases, in particular, in type II, the SRUs appear to result from spurious repeat duplication and are unlikely to perform any function. However, evolutionary conservation of SRUs was detected as well, notably, in subtype V-A. These SRUs could contribute to the recombination between CRISPR-cas loci but might also perform other functions, such as down-regulation of CRISPR effectors by the expressed small RNAs as proposed previously for phage-encoded SRU (49).

To conclude, the wide prevalence of mini-arrays and SRUs in CRISPR-cas loci is a remarkable case of functional flexibility and exaptation that seem to be particularly prominent in the evolution of defense and counter-defense systems (16). Further identification and experimental characterization of such elements can be expected to reveal additional regulatory and other roles, illuminating the broad spectrum of CRISPR functionality.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

S.A.S., K.S.M., Y.I.W., V.B. and E.V.K. are supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health of the USA (National Library of Medicine). Work in the Peters lab was supported by NIH R01 GM129118 (to J.E.P.).

Author contributions: S.A.S. collected the data; S.A.S., K.S.M., Z.K.B., J.E.P., Y.I.W. and E.V.K. analyzed the data; V.B. contributed to the development of computational methods; Z.K.B. and J.E.P. performed the experiments; S.A.S., Z.K.B. and E.V.K. wrote the manuscript that was edited and approved by all authors.

Contributor Information

Sergey A Shmakov, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Zachary K Barth, Department of Microbiology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Kira S Makarova, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Yuri I Wolf, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Vyacheslav Brover, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Joseph E Peters, Department of Microbiology, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853, USA.

Eugene V Koonin, National Center for Biotechnology Information, National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD 20894, USA.

Data Availability

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health of the USA (National Library of Medicine); NIH [R01 GM129118]. The open access publication charge for this paper has been waived by Oxford University Press – NAR Editorial Board members are entitled to one free paper per year in recognition of their work on behalf of the journal.

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Mohanraju P., Makarova K.S., Zetsche B., Zhang F., Koonin E.V., van der Oost J.. Diverse evolutionary roots and mechanistic variations of the CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2016; 353:aad5147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Barrangou R., Marraffini L.A.. CRISPR-Cas systems: prokaryotes upgrade to adaptive immunity. Mol. Cell. 2014; 54:234–244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barrangou R., Horvath P.. A decade of discovery: CRISPR functions and applications. Nat Microbiol. 2017; 2:17092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Nussenzweig P.M., Marraffini L.A.. Molecular Mechanisms of CRISPR-Cas Immunity in Bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 2020; 54:93–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Alkhnbashi O.S., Costa F., Shah S.A., Saunders S.J., Barrangou R., Brouns S.J., Charpentier E., Haft D.H.et al.. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015; 13:722–736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Iranzo J., Shmakov S.A., Alkhnbashi O.S., Brouns S.J.J., Charpentier E., Cheng D., Haft D.H., Horvath P.et al.. Evolutionary classification of CRISPR-Cas systems: a burst of class 2 and derived variants. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020; 18:67–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Brouns S.J., Jore M.M., Lundgren M., Westra E.R., Slijkhuis R.J., Snijders A.P., Dickman M.J., Makarova K.S., Koonin E.V., van der Oost J.. Small CRISPR RNAs guide antiviral defense in prokaryotes. Science. 2008; 321:960–964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Koonin E.V.. The basic building blocks and evolution of CRISPR-cas systems. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2013; 41:1392–1400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Semenova E., Jore M.M., Datsenko K.A., Semenova A., Westra E.R., Wanner B., van der Oost J., Brouns S.J., Severinov K.. Interference by clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR) RNA is governed by a seed sequence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108:10098–10103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wiedenheft B., van Duijn E., Bultema J.B., Waghmare S.P., Zhou K., Barendregt A., Westphal W., Heck A.J., Boekema E.J., Dickman M.J.et al.. RNA-guided complex from a bacterial immune system enhances target recognition through seed sequence interactions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2011; 108:10092–10097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Shmakov S.A., Sitnik V., Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Severinov K.V., Koonin E.V.. The CRISPR Spacer Space Is Dominated by Sequences from Species-Specific Mobilomes. MBio. 2017; 8:e01397-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shmakov S.A., Wolf Y.I., Savitskaya E., Severinov K.V., Koonin E.V.. Mapping CRISPR spaceromes reveals vast host-specific viromes of prokaryotes. Commun. Biol. 2020; 3:321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sampson T.R., Weiss D.S.. CRISPR-Cas systems: new players in gene regulation and bacterial physiology. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2014; 4:37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Westra E.R., Buckling A., Fineran P.C.. CRISPR-Cas systems: beyond adaptive immunity. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2014; 12:317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Faure G., Makarova K.S., Koonin E.V.. CRISPR-Cas: complex functional networks and multiple roles beyond adaptive immunity. J. Mol. Biol. 2019; 431:3–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Koonin E.V., Makarova K.S.. Evolutionary plasticity and functional versatility of CRISPR systems. PLoS Biol. 2022; 20:e3001481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Chylinski K., Le Rhun A., Charpentier E.. The tracrRNA and Cas9 families of type II CRISPR-Cas immunity systems. RNA Biol. 2013; 10:726–737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Liu L., Chen P., Wang M., Li X., Wang J., Yin M., Wang Y.. C2c1-sgRNA complex structure reveals RNA-guided DNA cleavage mechanism. Mol. Cell. 2017; 65:310–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Faure G., Shmakov S.A., Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Crawley A.B., Barrangou R., Koonin E.V.. Comparative genomics and evolution of trans-activating RNAs in Class 2 CRISPR-Cas systems. RNA Biol. 2018; 16:435–448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Yan W.X., Hunnewell P., Alfonse L.E., Carte J.M., Keston-Smith E., Sothiselvam S., Garrity A.J., Chong S., Makarova K.S., Koonin E.V.et al.. Functionally diverse type V CRISPR-Cas systems. Science. 2018; 363:88–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Harrington L.B., Ma E., Chen J.S., Witte I.P., Gertz D., Paez-Espino D., Al-Shayeb B., Kyrpides N.C., Burstein D., Banfield J.F.et al.. A scoutRNA is required for some type V CRISPR-Cas systems. Mol. Cell. 2020; 79:416–424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Workman R.E., Pammi T., Nguyen B.T.K., Graeff L.W., Smith E., Sebald S.M., Stoltzfus M.J., Euler C.W., Modell J.W.. A natural single-guide RNA repurposes Cas9 to autoregulate CRISPR-Cas expression. Cell. 2021; 184:675–688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]