Abstract

Obtaining sufficient genetic material from a limited biological source is currently the primary operational bottleneck in studies investigating biodiversity and genome evolution. In this study, we employed multiple displacement amplification (MDA) and Smartseq2 to amplify nanograms of genomic DNA and mRNA, respectively, from individual Caenorhabditis elegans. Although reduced genome coverage was observed in repetitive regions, we produced assemblies covering 98% of the reference genome using long-read sequences generated with Oxford Nanopore Technologies (ONT). Annotation with the sequenced transcriptome coupled with the available assembly revealed that gene predictions were more accurate, complete and contained far fewer false positives than de novo transcriptome assembly approaches. We sampled and sequenced the genomes and transcriptomes of 13 nematodes from early-branching species in Chromadoria, Dorylaimia and Enoplia. The basal Chromadoria and Enoplia species had larger genome sizes, ranging from 136.6 to 738.8 Mb, compared with those in the other clades. Nine mitogenomes were fully assembled, and displayed a complete lack of synteny to other species. Phylogenomic analyses based on the new annotations revealed strong support for Enoplia as sister to the rest of Nematoda. Our result demonstrates the robustness of MDA in combination with ONT, paving the way for the study of genome diversity in the phylum Nematoda and beyond.

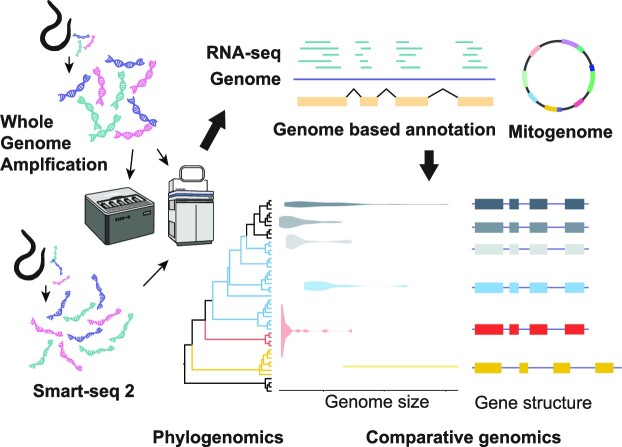

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

INTRODUCTION

A genome reference is a prerequisite for a complete understanding of the biology and evolution of a species. Advances in long-read sequencing, together with increasing affordable costs (1), have paved the way for the ambition to study and generate genomes for the entire group of species, including every bird, vertebrate, insect or eukaryote on Earth (2–5). However, the major challenge remains obtaining high-quality DNA and RNA from the majority of organisms across the tree of life (6). Such requirements are challenging to meet in microscopic organisms that cannot be cultured, leading to sampling bias and loss of their biological information on genetic and evolutionary studies (7–9). Recent advances in whole-genome amplification (WGA) have enabled single cells or limited samples to generate sufficient DNA for sequencing (10,11), and have been applied to eukaryotic microorganisms, including fungi (9,12), marine phytoplankton (13) and parasitic nematodes (14,15), for genomic and population genetic studies (9,16).

This study investigated the feasibility of WGA combined with long-read sequencing for nematodes, which are the most abundant metazoans on Earth. More than 40 million to 81.6 million nematode species are estimated to exist, but only ∼25,000 species have been described so far (17,18). The Nematoda phylum has been classified on the basis of 18S rRNA into three lineages and five major clades: Dorylaimia (clade I), Enoplia (clade II) and Chromadoria (clade III–V). Chromadoria further include Spirurina (clade III), Tylenchina (clade IV) and Rhabditina (clade V) as well as early derived lineages including Araeolaimida, Chromadorida, Desmodorida, Monhysterida and Plectida (19–21). The roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans was the first animal to have its genome sequenced, with a size of 100.3 Mb. Since then, >200 nematode genomes and mitogenomes have been published (22,23). Of these, ∼72% are mainly terrestrial parasites belonging in Dorylaimia, Spirurina and Tylenchina because of their importance in plant crops and animal health. The remaining species are terrestrial free-living nematodes in Rhabditina (17,24,25). In contrast, only one genome of a marine nematode, Litoditis marina (26), is available, despite the fact that marine nematodes comprise half of all recorded nematodes and play a crucial role in benthic communities as decomposers, predators, food sources and bioindicators (27). Only a few marine nematode species belonging to Monhysterida and Rhabditida (26,28) can be cultured. Thus, obtaining enough genomic DNA for sequencing is challenging for most of these species, making them potential candidates for the WGA techniques.

The Enoplia clade and the early derived Chromadoria lineage (19), found primarily in marine habitats, currently lack genomic data and have several important implications. Of particular interest is the phylogenetic relationship of basal nematodes, which remains unresolved due to insufficient sampling and limited resolution of 18S rRNA (20). Resolving the phylogenetic relationship of nematodes can help to understand the genomic basis of nematode diversity and the processes of evolution from free-living to a parasitic lifestyle (21,29). Increased sampling of marine nematodes and phylogenomic analyses based on mitogenomes or de novo transcriptomes have shown improved resolution of Enoplia sister to the rest of the Nematoda (19,22,30–32). Gene models predicted from genome assemblies will further confirm these findings.

Here, we have developed an assembly and annotation workflow capable of generating transcriptome and long genome sequences from single nematodes. We quantified the coverage biases in the amplified sequences, produced assemblies and assessed the accuracy of the annotations using this workflow on C. elegans compared with those generated de novo without a genome available. The finalized workflow was applied to 13 free-living marine nematodes isolated from the Taiwanese coasts. Despite obtaining lower genome coverage in these nematodes, phylogenomic analyses were performed using a total of 331,551 newly annotated genes to resolve the positions of basal clades in the Nematoda phylum. Comparisons of the genomes and complete mitogenomes of these nematodes revealed remarkable variation in genome features not observed in more studied clades and shed light on the early evolution of nematodes.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Single-worm DNA extraction

Caenorhabditis elegans strain N2 was grown at 22°C on nematode growth medium (NGM) plates with Escherichia coli strain OP50, and Aphelenchoides besseyi APVT strain was grown at 22°C on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates with Alternaria citri. Worms were either washed with M9 buffer from NGM plates and pelleted in a 15 ml centrifuge tube, or washed with the same M9 buffer three times and starved in M9 buffer that included 1% antibiotic–antimycotic (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA, 15240062) in a 15 ml centrifuge tube for 24 hr. A total of 13 nematode species (Epsilonema sp., Enoplolaimus lenunculus, Linhomoeus sp., Microlaimidae sp., Mesodorylaimus sp., Paralinhomoeus sp., Ptycholaimellus sp., Trileptium ribeirensis, Sabatieria punctata, Rhynchonemsa sp., Theristus sp., Trissonchulus latispiculum and Trissonchulus sp.) were collected in Taiwan between November 2020 and May 2022 (Supplementary Table S1). The sampling locations include seashores around Taiwan and 15–18 m depth sea bottom around Guishan island. Single individuals were isolated and washed with 10% bleach for 10 s and transferred into 200 μl polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tubes containing lysis buffer [8 μl of direct PCR lysis reagent (Viagen, #102-T), 1 μl of 5 mg/ml proteinase K and 1 μl of 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT)] and incubated in 65°C for 20 min and 95°C for 5 min. The DNA concentrations were quantified with the Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 2339927) following the manufacturer's instructions.

Whole-genome amplification

Various sources of extracted genomic DNA (gDNA) were used for amplification (Supplementary Figure S1). (i) Whole worm: one worm or 10 adult worms were cut into pieces with a 22-gauge needle in a 200 μl PCR tube. In one amplification instance, a single whole worm was prepared with 5% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) added in polymerase mix. Genomic DNA extraction and amplification were performed with the Qiagen REPLI-g Kit (150023,150043,150343, Qiagen, German). (ii) Purified DNA: single-worm DNA extraction with lysis buffer [8 μl of direct PCR lysis reagent (Viagen, #102-T), 1 μl of 5 mg/ml proteinase K, 1 μl of 200 mM DTT) and incubated in 65°C for 20 min and 95°C for 5 min. The samples were further purified using a 1:1 v/v ratio of sample to Ampure XP beads (A63882, Beckman Coulter, USA) and eluted in 10 μl of elution buffer. The MDA step was performed with the REPLI-g Kit (150023, Qiagen) following the manufacturer's instructions. A detailed protocol is available at protocols.io.

Genomic DNA library preparation, sequencing and assembly

The amplified genomic DNA was sent to Biotools Co., Ltd (New Taipei City, Taiwan) for library preparation and sequencing of Illumina 150 bp paired-end reads on a Novaseq 6000 sequencer. Genome sizes were estimated from Illumina reads using Jellyfish (ver. 2.3.0; -m 21) (33) and GenomeScope 2.0 (34). For Oxford Nanopore sequencing, two digestion times were initially tested on C. elegans using 1.5 μg of amplified gDNA from one or 10 adult worms. Templates were digested with T7 endonuclease I (M0302L, NEB, USA) for either 15 min, as recommended for sequencing whole-genome-amplified E. coli gDNA on the ONT community website (SQK-LSK109; ver. WAL_9070_v109_revN_14Aug2019) or 30 min. For the other nematodes, 3 μg of amplified templates were digested with T7 endonuclease I for 30 min and subjected to library preparation according to the manufacturer's instructions. Oxford Nanopore libraries were prepared according to SQK-LSK109 and SQK-LSK110 protocols, and a flowcell was sequenced in each species on a GridION instrument. Basecalling of Nanopore raw signals was performed using Guppy [ver. 6.1.2; with a super-accuracy (sup) model] into a total 224.5 Gb of raw reads at least 1 kb or longer. A summary of the sequencing data is shown in Supplementary Table S2.

We identified artificial palindromic sequences, described as reads that map to the reverse complement version of themselves either from the end or at least 30% within the middle of the reads, through Minimap2 alignments (version 2.1; -x ava-ont) (35). These palindromic sequences were extracted from raw reads and corrected by dividing the read from the midpoint of the alignment. This process was performed in two iterations using custom Perl scripts (available at https://zenodo.org/record/8144614), as a sequence may encompass multiple copies of the original fragment (36). Supplementary Table S3 provides a summary of the corrected sequencing data.

The Flye (ver. 2.9.1; option: –nano-hq) assembler (37) was used to assemble the raw ONT reads, which were then polished by four iterations of Racon (38) (ver. 1.4.11), followed by Medaka (ver. 1.2.0; option: -m r941_min_sup_g507 or r103_sup_g507; https://github.com/nanoporetech/medaka). The consensus sequences were further corrected with Illumina reads using NextPolish (39) (ver. 1.4.0), and haplotigs were removed using HaploMerger2 (40) (ver. 20180603). Contigs with non-nematode origins were excluded (see below for details). Genome completeness was assessed using the nematode dataset of BUSCO (41) (ver. 5.1.2). Assemblies were mapped to the reference genome with minimap2 (option: -ax asm5) (35), and genome coverage was calculated using BEDtools (ver. 2.26.0) (42). Raw Illumina reads were assembled using the Spades assembler (ver. v3.14.1; option: spades_sc) (43). The mitochondrial genome was assembled separately by aligning Oxford Nanopore reads to a mitochondrial protein-coding gene of 52 nematode species listed in Supplementary Table S4 using DIAMOND (44), following the approach described in (45). Circularized assemblies were further annotated and manually curated using two versions of Mitos (ver. 1.0.5) and Mitos2 (ver. 2.1.0) (46). The quality and completeness of the various C. elegans genome assemblies were compared using WebQUAST (utilizing the C. elegans WBcel235 genome with default option) (47) and BUSCO scores (ver. v5.1.2; option: eukaryota_odb10) (41).

Single-worm RNA transcriptome sequencing and assembly

The Smart-seq 2 protocol (48) was used to extract and amplify RNA from single adult worms. The resulting cDNA was sent to Biotools Co., Ltd (New Taipei City, Taiwan) for library preparation using the NEBNext® DNA Library Prep Kit (NEB, USA, 20015828, 20015829), and sequenced for 150 bp paired-ends on an Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer. Individual sample statistics are provided in Supplementary Table S2. We utilized FastQC (ver. v0.11.9; https://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/) to identify over-represented sequences, which we then matched against the NCBI nt database. If the matched sequences were predominantly associated with rRNA sequences, they were incorporated into the adaptor library. Sequencing reads were quality and adaptor trimmed using Trimmomatic (ver. 0.39) (49). On average, 30% of the reads in each sample were identified as rRNA sequences and, after removal, 21–86% of the reads remained. De novo transcriptome assemblies were generated using the Spades assembler (ver. v3.14.1; option: -k = 55,77) (43). The best protein-coding predictions from de novo assembled transcripts were produced using Transdecoder (ver. 5.5.0; https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder) integrating homology information from the UniProt database (Release version 2021_03).

Genome annotation

Repetitive elements were identified using RepeatModeler (ver. 2.1) (50), TransposonPSI (ver. 1.0.0; https://github.com/NBISweden/TransposonPSI) and USEARCH (ver. 11.0) (51) based on the protocol by Berriman et al. (https://protocolexchange.researchsquare.com/article/nprot-6761/v1). Repetitive DNA sequences were identified and masked using Repeatmasker (ver. 4.1.2; http://www.repeatmasker.org). Proportions of repeat content along the non-overlapped 100 kb window were calculated using BEDTools (ver. 2.26.0) (42).

The proteomes of 11 representative nematodes were obtained from WormBase WBPS18 (52) and are listed in Supplementary Table S5. Single-worm transcriptome reads were mapped to the corresponding genome assemblies using STAR (ver. 2.7.7a) (53). The gene models were predicted using BRAKER2 (ver. 2.1.6; option: –etpmode) (54) with proteomes and RNA-seq mappings as evidence hints. Transcript predictions were mapped to the reference genome using Minimap2 (-ax splice) (35), converted to gff format and compared against the reference proteome using Gffcompare (ver. v0.11.2) (55).

Decontamination

To identify contigs of non-nematode origin, we used a combination of three methods. First, we employed Kraken2 (ver. 2.1.2) (56) to determine the kingdom and phylum of scaffolds based on k-mers. We rebuilt a custom Kraken2 database to include: Archaea, Bacteria, Nematoda, Eukaryota (Annelida, Arthropoda, Cnidaria, Chordata, Porifera, Placozoa and Platyhelminthes), outgroup (human), viruses and undefined. A list of species in the reconstructed database is provided in Supplementary Table S6. The BRAKER2 models were searched against the NCBI nr database using BLAST to assign phylum categories, such as Nematoda, Bacteria, Eukaryota, Eukaryotea-undef, Candidatus, Fungi, Planta, Viruses, Algae, Archaea and Unclassified. Third, we aligned RNA-seq reads for each species to the corresponding genome assemblies using STAR and calculated the RNA-seq mapping rate of each scaffold using BEDTools (ver. 2.26.0) (42). We excluded scaffolds assigned to bacteria by Kraken2 and those with genes that contained ≥90% bacterial proteins. For scaffolds that could not be identified by Kraken2 or the NCBI nr database, we removed those with <1,000 RNA-seq mapped reads.

Phylogenomics of nematodes

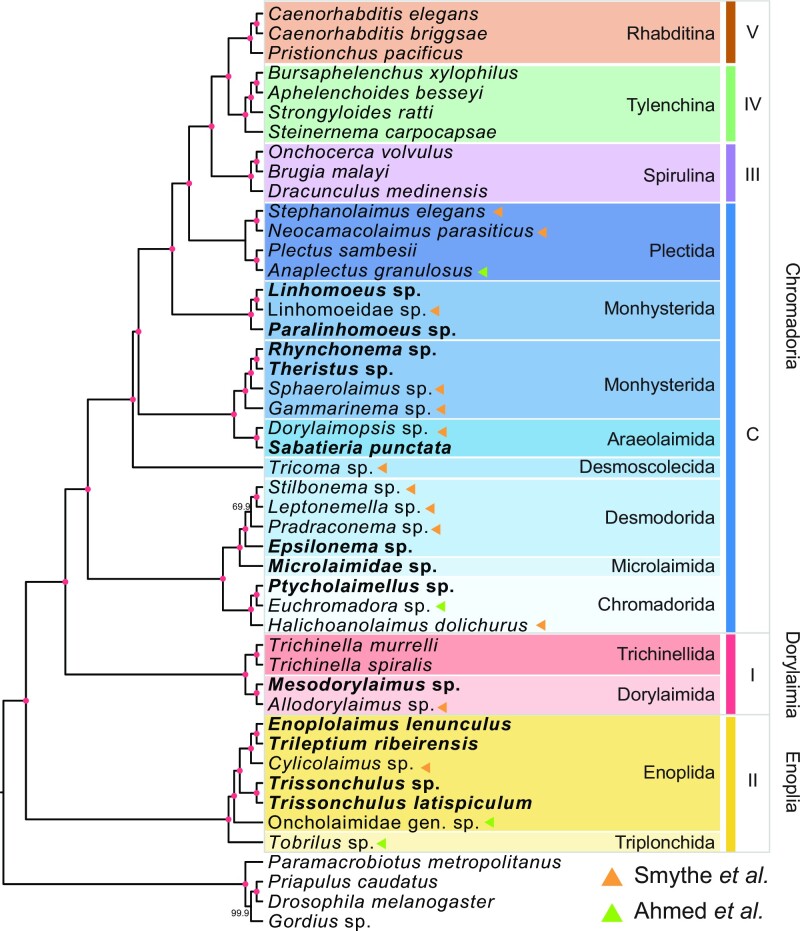

Protein datasets from 13 representative nematodes were download from WormBase WBPS18 (52) (Supplementary Table S7). We also downloaded the assembled transcripts of nine nematode species, an outgroup Nematodmorpha from Smythe et al. (19) and 19 nematode species from Ahmed et al. (32) (Supplementary Table S7). Species with BUSCO completeness > 20% were included in the phylogenomics analyses. Orthogroups (OGs) were identified using OrthoFinder (57). Sequences in OGs were aligned using MAFFT (ver. 7.515) (58). Gene trees were inferred from OGs containing >15% of the species and alignment length longer than 200 bp using VeryFastTree (ver. 4.0) (59), and a species tree was inferred from all OG gene trees using ASTRAL-Pro (60). Two sets of data were used to construct the nematode species phylogeny: (i) the 13 proteomes of nematode species downloaded from WormBase, 13 free-living nematodes sequenced in this study and outgroup Priapulus cauatus, comprising a total of 27 species with 46,158 OGs (Supplementary Table S7); and (ii) 27 species with genomes from the first dataset, de novo transcriptomes of five species (four nematodes and one Gordius sp.) from Smythe et al. (19) and 13 species from Ahmed et al. (32), Drosophilamelanogaster and Paramacrobiotus metropolitanus, comprising a total of 47 species with 58,381 OGs. Gene trees from 9,343 and 7,898 OGs were chosen and used to infer the species tree in the first and second dataset, respectively.

RESULTS

Whole-genome amplification facilitates sufficient DNA for long-read sequencing from single nematodes

To study the genome diversity of free-living nematodes, we isolated nematodes from a variety of marine environments in Taiwan and extracted the gDNA from individual adults across 11 taxa, including the Enoplia clade, for which genome sequences are currently unavailable (Supplementary Table S1). Highlighting the challenge of obtaining sufficient gDNA for long-read sequencing across the Nematoda phylum, we found that yields ranged from 1.5 to 3.8 ng for individual adults and were not associated with worm size (Kendall's τ = 0.2, P = 0.33; Supplementary Table S8). To mitigate this problem, we used MDA to amplify whole genomes from individual nematodes, yielding 6.2–51.5 μg, corresponding to ∼4,700× and 22,000× amplification using REPLI-g mini kits and REPLI-g midi or sc kits, respectively (Supplementary Table S2). To assess potential amplification bias, we first sequenced the genome of the model nematode C. elegans N2. A total of 35 μg of gDNA was obtained after MDA from an initial 1.56 ng, and sequencing using an ONT 9.4.1 flow cell yielded 7.36 Gb with an N50 of 7.74 kb, corresponding to 73.6× depth of coverage (61) (Supplementary Table S2).

Whole-genome amplification disparity in repetitive regions

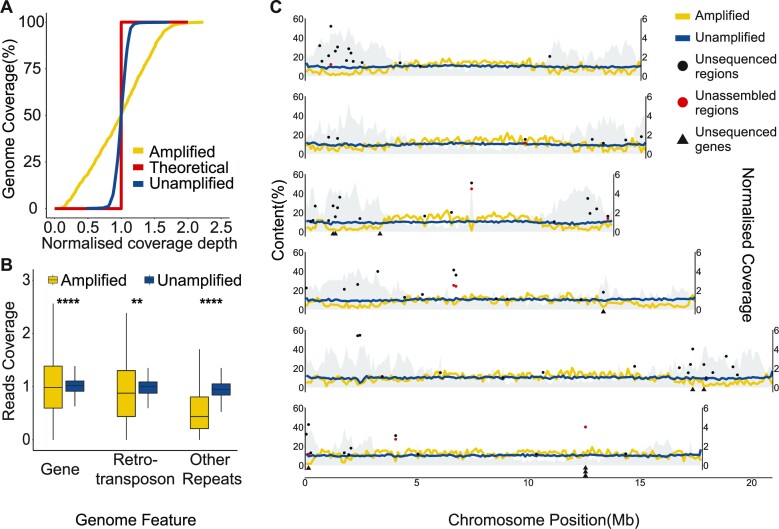

MDA suffers from several challenges, the most important of which is highly uneven amplification (62,63). This issue can lead to incomplete genome assembly and reduced coverage in certain genome regions, and affect analyses such as copy number variants (63,64). We aligned the amplified and published unamplified ONT reads (65) against the C. elegans genome, and the former clearly displayed an uneven depth of coverage, with 19.2% of the non-overlapping 100 kb window showing less than half of the genome-wide median (Figure 1A). Sequencing of the amplified DNA using Illumina short reads also exhibited similar patterns, suggesting that the MDA rather than the sequencing platforms was causing the bias (Supplementary Figure S2A). The intrachromosomal heterogeneity of the enriched repeats present in the nematode autosome ends was clearly associated with this unevenness. In the six C. elegans chromosomes, the end region contains a significantly higher number of repeat sequences (P 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test) and a lower read coverage (P

0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test) and a lower read coverage (P 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test; Supplementary Figure S2B, 2C) compared with the center region. However, in the X chromosome, the read coverage is more balanced due to the lower percentage of repeats in the end region (median of repeats 16–21% versus 15–39% in autosomes; Supplementary Figure S2D).

0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test; Supplementary Figure S2B, 2C) compared with the center region. However, in the X chromosome, the read coverage is more balanced due to the lower percentage of repeats in the end region (median of repeats 16–21% versus 15–39% in autosomes; Supplementary Figure S2D).

Figure 1.

Sequencing coverage of C. elegans genomic DNA. (A) Cumulative genome coverage versus the genome-wide median. The red line indicates the theoretical coverage of unbiased coverage. More deviation away from this line suggests less uniformity across the genome. (B) Normalized read coverage on genes and repeats. Repeats were categorized into two groups: retrotransposons and other repeats. Retrotransposons include long interspersed nuclear elements (LINEs), short interspersed nuclear elements (SINEs) and long terminal repeats (LTRs). DNA transposons, RC Helitron, rRNA, snRNA, tRNA, satellite, simple repeat and unknown repeats were together labeled as other repeats. **P 0.01, ****P

0.01, ****P 0.0001. (C) Lines represent normalized read coverage of amplified and unamplified data. The black and red dots represent the top 10% of regions (11.1–44.8 kbp and 10.1–54.5 kbp) that were not sequenced and not assembled. The triangles represent the position of genes that were not sequenced at all. The shaded area indicates the proportions of repeats along the chromosomes.

0.0001. (C) Lines represent normalized read coverage of amplified and unamplified data. The black and red dots represent the top 10% of regions (11.1–44.8 kbp and 10.1–54.5 kbp) that were not sequenced and not assembled. The triangles represent the position of genes that were not sequenced at all. The shaded area indicates the proportions of repeats along the chromosomes.

We calculated the proportions of 17 genomic features in 100 kb non-overlapping windows and found that the presence of rolling-circle transposable elements (RC/Helitron) contributed least to sequence coverage (R2 = 0.36, P < 22e-16, Pearson test), followed by unclassified repeats, DNA transposable elements and satellites (Supplementary Figure S3), suggesting that the reduced coverage displayed at autosome ends was mainly due to enriched repeats (61). Within repeat classes, other repeats were the primary repeat class affecting coverage (Figure 1B; Supplementary Figure S4). Of 6,332 rolling-circle transposable element regions totaling 1,409,947 bp, on average there is a 36.7% reduction of coverage compared with the genome median (68× versus 25×; Supplementary Figure S4). The coverage of amplified data on the gene, retrotransposon and other small repeats was significantly lower than of unamplified data (Figure 1B). Finally, we determined 0.49 Mb that were not sequenced at all, ranging from 2 to 40,137 bp. Of these, 17% were repeats and 80 (0.3%) genes were affected. Ten genes located at the ends of chromosomes III, IV, V and X were not completely sequenced (Figure 1C). At the exon level, 0.09% were also affected, including 96 unsequenced CDS.

Due to differences in repeat content between species, we sought to evaluate the impact of MDA by analyzing the amplified reads from the genome of the plant-parasitic nematode A. besseyi, which has a smaller genome (44.7 Mb) and lower repeat content (5.38%) compared with other nematodes (66). A similar but less pronounced pattern of uneven coverage was observed in this nematode compared with C. elegans (Supplementary Figure S5A). In the A. besseyi chromosomes, the chromosome end also contains a significantly higher percentage of repeat sequences and lower read coverage (P 0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test; Supplementary Figure S5B, C). While we observed reduced coverage in repeat regions, we were able to capture most of the genome, with only 0.06% (29,230 bp) of the genome not sequenced, with missing regions ranging from 1 to 2,540 bp and affecting only six repeats and four genes. Taken together, these observations suggest that the MDA approach is a robust approach for capturing most of the genome, although additional sequencing may be required to rescue repetitive regions in some species.

0.001, Wilcoxon rank sum test; Supplementary Figure S5B, C). While we observed reduced coverage in repeat regions, we were able to capture most of the genome, with only 0.06% (29,230 bp) of the genome not sequenced, with missing regions ranging from 1 to 2,540 bp and affecting only six repeats and four genes. Taken together, these observations suggest that the MDA approach is a robust approach for capturing most of the genome, although additional sequencing may be required to rescue repetitive regions in some species.

Presence of palindromic sequences after whole-genome amplification

An additional challenge arising from the MDA process is the unintended creation of chimeric fragments which hamper downstream analysis (67). These fragments include inverted repeat sequences, commonly referred to as palindromes, which are the result of continuous amplification of branched DNA produced during the displacement process (36,68). We identified 8.8–30.9% of C. elegans samples as palindromes (Supplementary Figure S6). By dividing these sequences from the center of the palindrome (see the Materials and Methods), their prevalence was down to 1.2–5.7% (Supplementary Figure S6). This procedure led to an averaged sequence N50 and number of long sequence (designated as ≥50 kb) reduction by 1.3 kb and 57.6% (Supplementary Table S2 and S3), respectively, indicating that numerous long sequences in the dataset were chimeras. The genome coverage of the palindrome reads paralleled that of non-palindrome reads (Supplementary Figure S7), presumably showing that the chimera generation process occurred randomly.

Longer T7 endonuclease digestion time increase ONT sequencing performance

To enhance the yield and minimize the bias of sequencing amplified samples, we attempted to optimise different stages of the workflow (Supplementary Figure S1). One of the challenges was that the branching templates generated by MDA were unsuitable for Oxford Nanopore sequencing as they can block sequencing pores and reduce sequencing yield (69). T7 endonuclease I was used in the existing protocol to generate linear templates by cutting the junction of the branching template. We found that the digestion time of T7 endonuclease I affected the drop-out rate of sequencing pores and sequencing output (Supplementary Figure 8A) (70). A longer digestion time (30 versus 15 min) improved the sequencing performance by reducing the dropping rate of sequencing pores and increasing the sequencing yield (Supplementary Figure S8B, C). In addition, we tried three other approaches to address the influence of repeats that reduce amplification efficiency (Supplementary Figure S1), but no improvement was observed (Supplementary Figure S2A), indicating that uneven coverage is related more to the polymerase efficiency in amplifying repeats.

Complete genome assemblies from amplified sequences

To evaluate the feasibility of generating assemblies from amplified sequences, we generated genome assemblies of C. elegans based on different data types and sources (Supplementary Table S9). On average, 112.5× Illumina and 32.6–88.6× ONT reads were used; the initial assemblies produced under the default options yielded 77.7–115.0 Mb and the recently updated size of 102 Mb (71), suggesting that the biased genome coverage in the amplified reads remains a challenge in the assembly process. Correcting the palindromes in the amplified samples led to more accurate assemblies (Supplementary Table S10), which will be used for all downstream analyses. The final assemblies were produced using the meta option of the Flye assembler, with haplotigs removed, screened for contamination and polished using Illumina reads (see the Materials and Methods), resulting in more similar genome sizes (97.3–98.4 Mb, Supplementary Table S9). Compared with the assembly from unamplified long sequences (65), the N50 of the genome-amplified assembly is 91% shorter than that of the unamplified data, presumably due to the shorter ONT sequence length achieved by MDA (Table 1).

Table 1.

Statistics of C. elegans genome assemblies

| Reference | Amplified | Unamplified | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reads N50 (kb) | – | 7.7 | 21.1 |

| Depth | – | 73.5 | 88.6 |

| Size (Mb) | 100.3 | 98.4 | 103.2 |

| Sequence number | 7 | 499 | 55 |

| Longest (Mb) | 20.9 | 2.7 | 15.1 |

| Minimum (bp) | 13,794 | 1,447 | 1,437 |

| N50 (kb) | 17,494 | 656.2 | 6,868.7 |

| L50 | 3 | 43 | 5 |

| N90 (kb) | 13,784 | 122.0 | 2,966.0 |

| L90 | 6 | 185 | 13 |

| BUSCO completeness (%) (nematode lineage) | 98.8 | 97.6 | 98.8 |

| Assembly covered (%) | – | 97.4 | 100.0 |

We assessed the completeness of the de novo assemblies of single and 10 pooled nematode(s) by first aligning their contigs back to the reference. The unamplified data covered 100.0% of the reference genome, compared with 97.4% for the single-worm amplified assembly (Table 1). A total of 2.5–4.4 Mb of the reference genome was not covered by the amplified genomes. We benchmarked the completeness of the assemblies using universal single-copy orthologs [BUSCO (41)], which were similar regardless of amplification (Table 1). The unassembled regions coincided with unsequenced or highly repetitive regions which were mostly located on the chromosome ends (Figure 1C). Taken together, the results show that the capability of sequencing the genome of the nematode with only a single worm using the WGA method is equivalent to using multiple worms. Interestingly, we observed a decrease in reference coverage (97.4% versus 95.8%) and BUSCO completeness (97.6% versus 95.2%) as the number of worms increased from a single worm to 10 worms prior to MDA. In addition, more contaminant sequences were present (14.4–16.9 Mb versus 0.1–0.2 Mb in a single worm) (Supplementary Table S9).

High quality annotations from a single nematode genome and transcriptome

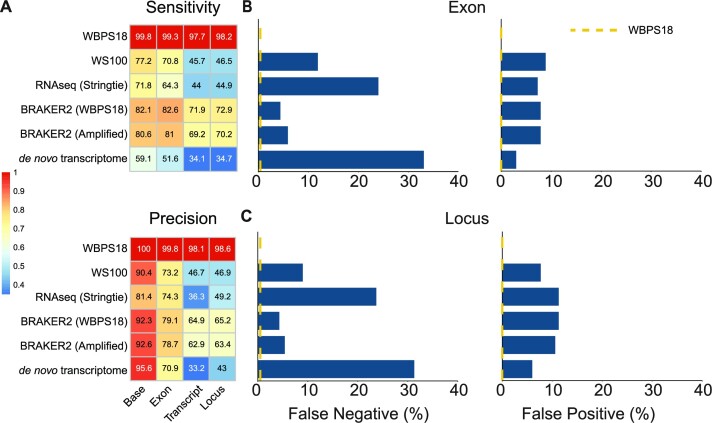

To quantify the difference between annotation based on a single worm genome and transcriptome, we profiled the transcriptome from a single C. elegans adult based on the Smartseq2 protocol and generated ∼10 Gb of Illumina reads [(48); Supplementary Table S2]. We generated annotations either by de novo assembly of these reads or by mapping these reads to the genome assembly and used these reads as evidence in the BRAKER2 pipeline. To evaluate the accuracy of the annotations from different approaches and datasets, all gene predictions were aligned back to the C. elegans reference and compared with the most recent annotation of 19,981 protein-encoding genes from WormBase [ver WBPS18; (52)] (Figure 2; Supplementary Table S11). Comparing two versions of the C.elegans reference (WBPS18 versus WS100), more loci (19,406 versus 17,153) were annotated in the current reference, demonstrating the improvement in gene annotation over time. Gene structures predicted using single-worm RNA-seq mapped to the reference genome by Stringtie (72) had lower sensitivity and precision compared with the reference proteome, and the BRAKER2 pipeline produced a more accurate prediction when using these mappings as hints. More importantly, the same pipeline produced predictions with only a slightly reduced accuracy of 1.5% on average when the genome-amplified assembly was used instead (Figure 2A). As expected, these annotations were more sensitive and accurate than those that were originally published (WS100) and de novo transcriptomes for all metrics (Supplementary Table S11). The de novo transcriptome had more missing exons (33.1% versus 4.4–24.0%), missing loci (31.3% versus 4.3–23.7%) and fewer matching transcripts (6,821 versus 8,797–14,366) (Figure 2B, C). Of particular note, the proportions of 50% and 95% assembled genes, which are imperative for phylogenomic analyses, were 68.0% and 51.4% lower in the de novo transcriptome compared with the annotation produced with the available genome-amplified assembly (Supplementary Table S11). These results indicate that the genome-amplified assemblies can be annotated with reasonable accuracy using the existing pipeline.

Figure 2.

Comparison of annotations using different approaches and datasets. (A) Sensitivity and precision on the base, exon, transcript and locus level. WBPS18 indicates the baseline performance when the reference proteome of C. elegans was aligned back to its reference genome using Minimap2. The color of the heatmap is the value of each sample divided by the values in the WBPS18 comparison. (B and C) Percentage of false negatives and false positives in the exon and locus. False negatives are the precentage of reference genes missing from the predictions, whereas false positives are new genes in the predictions that are not present in the reference proteome. A yellow dashed line represents the value of the WBPS18 comparison as baseline.

Genome characteristics of free-living nemtodes

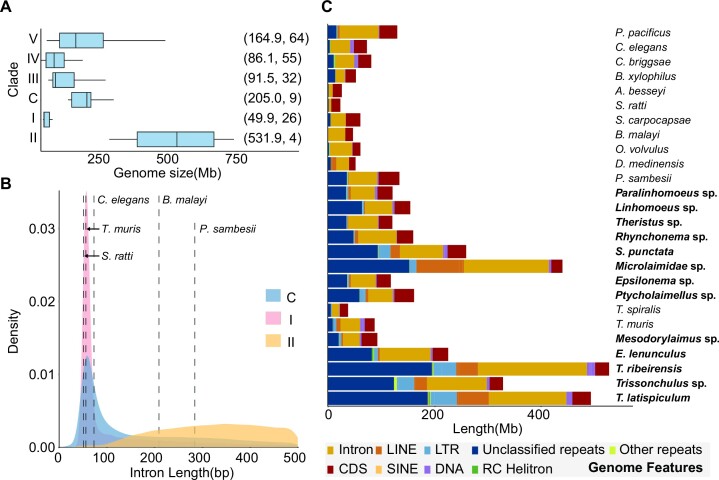

We applied our optimised sequencing and annotation protocol to 13 free-living nematode genomes from three clades collected from the north coast of Taiwan (Table 2). On average, 12 Gb of palindrome-corrected (Supplementary Figure S6B) ONT genomic reads and 5 Gb of transcriptome reads were sequenced from single adults with a total of two worms per species (Supplementary Table S2) and the genome assemblies ranged from 136.6 to 738.8 Mb. The Chromadoria and Enoplia nematodes have typically larger genome sizes than other clades (Figure 3A), with the T. latispiculum 738.8 Mb assembly being the second largest currently recorded in nematodes following the 2.5Gb of the horse parasite Parascaris univalens (73). Some of the assemblies may underestimate the true genome size, as the sequence coverage was as low as 11×, warranting additional sequencing. Using the BRAKER2 pipeline, 18,082–35,701 protein-coding genes were annotated in 13 free-living nematode genomes and were 32.6–99.2% complete based on BUSCO analysis (Supplementary Table S12). A positive correlation was observed between the BUSCO score and both genome N50 (Kendall's τ = 0.49, P = 0.01) and ONT coverage (Kendall's τ = 0.44, P = 0.02). The intron distribution of the Dorylaimia and Chromadoria lineages sequenced in this study had a similar pattern, peaking around 55 bp (Table 2; Supplementary Figure S9), and were similar to previously published nematodes in these clades (74). Interestingly, there are fewer but longer introns in the four Enoplia species, suggesting a different intron distribution in the last common ancestor of this clade compared with the rest of the nematodes (Figure 3B; Supplementary Figure S10). Orthology inference using Orthofinder (57) placed these gene models and those of 13 other nematode genomes into 46,158 orthologous groups. Within these orthologous groups, 50.8% (23,469 orthologous groups) were shared between two or more species, consistent with previous observations of extensive clade-specific families in nematode lineages (75). In addition, 23.6–49.8% of the genes in 13 free-living nematode species were species specific (Supplementary Table S13). The proportion of these species-specific genes was positively correlated with the number of gene models (Kendall's τ = 0.7, P < 0.001) but not genome size, assembly N50 or ONT coverage.

Table 2.

Genome statistics of 13 free-living nematode genome assemblies

| Species | Clade | Size (Mb) | Sequence (n) | Longest (kb) | N50 (kb) | Gene (n) | Intron length median (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mesodorylaimus sp. | I | 142.5 | 1,557 | 2,535.9 | 441 | 22,631 | 65 |

| Trissonchulus sp. | II | 421.5 | 17,985 | 425.7 | 51.9 | 35,701 | 559 |

| T. ribeirensis | II | 738.8 | 30,949 | 369.1 | 44.3 | 18,082 | 1,893 |

| E. lenunculus | II | 286.5 | 2,646 | 2,205.1 | 266.9 | 24,757 | 612 |

| T. latispiculum | II | 642.2 | 28,528 | 427.8 | 51 | 26,621 | 558 |

| Theristus sp. | C | 150 | 4,198 | 376.4 | 81.9 | 18,733 | 264 |

| S. punctata | C | 302.3 | 7,416 | 842.6 | 125.2 | 29,890 | 112 |

| Ptycholaimellus sp. | C | 219.7 | 12,974 | 357.8 | 37.1 | 29,037 | 58 |

| Linhomoeus sp. | C | 207.3 | 13,199 | 327.6 | 31.6 | 28,535 | 99 |

| Paralinhomoeus sp. | C | 147 | 3,410 | 697.5 | 104 | 24,020 | 79 |

| Microlaimidae sp. | C | 540.3 | 32,219 | 243.1 | 26.3 | 27,483 | 1,099 |

| Epsilonema sp. | C | 136.6 | 5,280 | 530.5 | 68.2 | 21,223 | 264 |

| Rhynchonema sp. | C | 205 | 7,081 | 692.2 | 77.6 | 24,838 | 231 |

Figure 3.

Nematode genome size, intron distribution and genome structure. (A) Genome size variation between different nematode clades. The text in parentheses denotes the median genome size in megabases and the number of nematode genomes downloaded from WormBase ParaSite (52) to be included in the analysis, respectively. (B) Intron distribution of nematodes. Dashed lines are the intron median of the representative species in clades I, III, IV and V and Chromadoria (C). (C) The proportion of different genome features in the nematode genomes. Bold letters represent the nematode genomes assembled in this study. The ‘Other repeats’ feature includes the sum of tRNA, snRNA, rRNA, simple repeats and satellites.

Of the 13 nematode species sequenced in this study, nine were able to assemble a circular mitochondrial genome (mitogenome) with a read coverage depth of 39–2,656×. Interestingly, the 12 proteins typically found in nematode mitogenomes were only completely predicted in five species. These mitogenomes are highly rearranged compared with other clades (Rhabditina, Spirurina and Tylenchina) (Supplementary Figure S11). The gene order in Mesodorylaimus sp. showed lack of synteny compared with other species in Dorylaimia, consistent with previous observations of a high rearrangement rate in the Dorylaimia species (76).

The basal Chromadoria and Enoplia assemblies contained significantly more repeats (23.4–50.6%) than the representative nematodes across the other four clades (0.8–31.4%; Figure 3C; Supplementary Figure S12). This is consistent with the previous finding of a marked decrease of transposable element load at ancestral nodes especially at the base of clade III + IV + V (77). In contrast to most published genomes in the Dorylaimia and Rhabditina clades, which were enriched in DNA transposons (75), (Supplementary Figure S13A), LTRs or LINE repeats were more abundant in six free-living nematode species and T. muris, especially in the two Trissonchulus species (LTRs 7.9% versus 0.1–7.6% in other species). A total of 16,046 unknown repeat families were identified in the 13 nematodes, which were clustered into 16,044 sequence groups based on 90% identity, suggesting that they were species specific. These unclassfied repeats were evenly distributed across the genome with the exception of three species in Enoplia (Trissonchulus sp., T. latispiculum and T. ribeirensis), which each had a dominant family comprising 2.2–5.6% and 0.7–1.5% of the unclassified repeats and genomes, respectively.

Enoplia is sister to the rest of the nematode classes

To support the basal branch order of the Nematoda phylogeny, in particular the relative placement of Enoplia and Dorylaimia, a species tree was inferred based on a coalescent-based analysis (60,78) of 9,343 paralogous gene trees from 26 representative nematode species, and the cactus worm Priapulus cauatus as an outgroup. The species phylogeny separated nematodes into six groups, comprising five clades and groups of the early derived Chromadoria lineage (20), and placed Enoplia as a sister group to Dorylaimia and the Chromadoria lineage, both with strong boostrap support (Supplementary Figure S14). The topology remained similar when we included an additional 17 de novo transcriptomes from Enoplia and Chromadoria and a further three outgroups (Figure 4) (19,32). The combined phylogeny shows that nematodes can be separated into the previously designated five clades (20) and support for the placement of Enoplia remained robust (Astro-pro, bs = 100). In the early derived Chromadoria lineages, most of the lineages were grouped by order, with the exception of the Monhysterida lineage which was paraphyletic (32).

Figure 4.

Phylogenetic analysis combining the nematode transcriptome and genome. Bold font represents the genomes sequenced in this study. Roman numerals on the right represent the five clades of Nematoda, and C represents the basal Chromadoria lineage. The colors of triangles denote the data source. The red dots in branches denote a bootstrap support value of 100.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we demonstrated the feasibility of generating genome assemblies from single adult nematodes using MDA. By testing the protocols on C. elegans, we were able to fully quantify the extent of bias and address it with existing analysis pipelines. We demonstrate that a genome assembly and accurate gene annotations can be achieved with this workflow and further sequenced the genomes of 13 free-living nematodes. With a genome size of 136.6–738.8 Mb in 13 nematodes, sequencing on a single MinION flowcell can be expected to provide ∼37.8× depth of coverage. Of these genomes, four are the first reported in the Enoplia clade, revealing their unusually large genome sizes and structures (Figure 3). Through phylogenomics, we established Enoplia as sister to the phylum Nematoda, supporting a marine origin in the last common ancestor of nematodes (19,32). Analysis of repetitive content in these new genomes revealed that transposable element and genome reduction might have taken place in the last common ancestor of clade III + IV + V (77). We bypassed the challenging stage of obtaining axenic cultures (8), whilst assembly and annotation can be achieved within a week of nematode isolation. Assuming that 1 μg is required for long-read sequencing, combining MDA with ONT sequencing thus provides a cost- and labor-effective solution (1) to generate complete assemblies in organisms with as little as 50 pg of starting material. We note that the amplified products no longer contain the native information present on the original templates, such as methylation, which was accessible by single-molecule sequencing. Nevertheless, there is tremendous interest in using the integrated approach to sequence parasitic nematodes (79), different species and sequencing platforms, and at a single-cell resolution (36,80). For example, assembly from PacBio HiFi sequencing of an amplified single human CD8+ T cell resulted in an assembly with 12.8% complete gene models (81).

The advantage of using a single individual for whole-genome sequencing is also seen in the sequencing of organisms such as obligate symbionts and helminth eggs, where it is possible to overcome obstacles such as inability to culture and inaccessibility in the live host (9,82). The use of a single nematode had several benefits over pooling multiple worms, for instance closely related nematode species have imperceptible morphological differences that increased the risk of mixing different species (83,84). For example, a host can be infected with multiple Anisakis species with no morphological differences (85). In addition, natural populations are likely to have high levels of heterozygosity, which also affects the quality of assembly and annotation, as observed in this study.

The MDA method used in this study is known to result in uneven read coverage (86). This unevenness is thought to be caused by the formation of secondary structures that reduce the efficiency of the phi29 polymerase used in the amplification process, particularly in repetitive sequences that are prone to forming such structures (63,86). Despite these challenges, only 0.4% of the C. elegans genome remained unsequenced including 10 genes. This approach allowed us to effectively assemble the genome, with only 2.5% missing due to the combined challenges posed by repetitive sequences and reduced coverage. A notable limitation is that the N50 of the amplified data appears to be capped at ∼8 kb, with longer reads probably originating from chimeric sequences. This has led to a more fragmented assembly compared with an assembly from an unamplified sample. Nevertheless, the longest non-palindromic sequences ranged from 49.2 to 734.4 kb, demonstrating MDA’s capability to amplify long templates. The BUSCO completeness values suggest that the amplified assembly is complete and capable of generating high-quality annotation compared with the reference genome (96.1% versus 98%).

Our study shows that gene predictions from genomes with RNA-seq data as hints outperform de novo transcriptome assemblies, especially in the number of 95% assembled loci (84.7% versus 43.1%). This is expected, and a balance needs to be struck between the accuracy of gene prediction per species and the breadth of species sampling. Hence, we advocate for the inclusion of complete assemblies in selected samples to facilitate future phylogenomic analyses initially intended to use only de novo transcriptome samples. While the assemblies may not necessarily need to meet reference standards, a caveat is the dependency of predicted gene model accuracy on the quality of assembly consensus and contiguity (87). The latter had a greater impact in our dataset, as indicated by the stronger positive correlation between the BUSCO completeness and assembly N50 over ONT coverage. In addition, the combination of a high proportion of species-specific genes coupled with lower BUSCO completeness in some assemblies suggests the presence of mispredictions. A well-known example was the first published Heterorhabditis bacteriophora assembly, in which 52.7% of 21,250 gene models had no C. elegans homolog and a BUSCO completeness of 47.8% (88). A later improved set of gene models exhibited a 94.0% BUSCO completeness with relatively fewer species-specific genes (89). Despite the presence of potential mispredictions in our dataset, they should not hinder phylogenomic analyses as species-wide orthologs were employed. Supplementing lower coverage assemblies with additional sequencing is likely to improve the overall data quality and result accuracy.

To conclude, we demonstrate the feasibility of incorporatng WGA into investigation of microbial biodiversity from sampling to comparative genomic analysis. By thoroughly characterising and accounting for the inherent limitations of this approach, complete assemblies and accurate gene predictions can be generated. The availability of the new free-living genomes has allowed us to address outstanding questions and offer new biological insights. As long-read sequencing advances in accuracy and affordability, we envisage that a complete assembly will be available for any species that were once considered inaccessible.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank Wei-An Liu for testing out the initial MDA protocols in yeast. We thank the NGS Genomics core lab of Academia Sinica of Taiwan for sequencing the initial single-worm RNA-seq data. We would like to thank the National Center for High-performance Computing (NCHC) of the National Applied Research Laboratories (NARLabs) of Taiwan for providing computational resources and storage resources. We thank Dionysis Grigoriadis for his assistance in uploading the genome assemblies and annotations to the WormBase ParaSite database.

Authors’ contributions: I.J.T. conceived the study; Yi.C.L., Yu.C.L., M.C.W. and Y.C.T. carried out the sampling; Yi.C.L. isolated the nematodes; Yi.C.L. and H.M.K. conducted the experiments and ONT sequencing; Yi.C.L. performed the assemblies and annotations with help from H.H.L. and Yu.C.L.; Yi.C.L. carried out analyses. Yi.C.L. and I.J.T. wrote the manuscript with input from T.K. and others. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Yi-Chien Lee, Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan; Biodiversity Program, Taiwan International Graduate Program, Academia Sinica and National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan; Department of Life Science, National Taiwan Normal University, 116 Wenshan, Taipei, Taiwan.

Huei-Mien Ke, Department of Microbiology, Soochow University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Yu-Ching Liu, Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan.

Hsin-Han Lee, Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan.

Min-Chen Wang, Marine Research Station (MRS), Institute of Cellular and Organismic Biology, Academia Sinica, 262 I-Lan County, Taiwan.

Yung-Che Tseng, Marine Research Station (MRS), Institute of Cellular and Organismic Biology, Academia Sinica, 262 I-Lan County, Taiwan.

Taisei Kikuchi, Department of Integrated Biosciences, Graduate School of Frontier Sciences, The University of Tokyo, Chiba 277-8562, Japan.

Isheng Jason Tsai, Biodiversity Research Center, Academia Sinica, Taipei 115, Taiwan; Biodiversity Program, Taiwan International Graduate Program, Academia Sinica and National Taiwan Normal University, Taipei, Taiwan.

Data Availability

All sequences generated from this study were deposited on the NCBI under BioProject PRJNA953805, and the Biosample accession number of the free-living nematodes can be found in Supplementary Table S3. The assemblies and annotations of the 13 free-living species are also available in the WormBase ParaSite ftp (https://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/wormbase/parasite/datasets/PRJNA953805/). The scripts and proteome data are available in Github page: https://yichienlee1010.github.io/Single-nematode-genome/ (permanent doi: https://zenodo.org/record/8144614).

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary Data are available at NAR Online.

FUNDING

Academia Sinica [AS-CDA-107-L01 to I.J.T.]; the National Science and Technology Council [111-2628-B-001-021 to I.J.T.]; and Taiwan International Graduate Program, Academia Sinica of Taiwan, [doctorate fellowship to Yi.C.L.].

Conflict of interest statement. None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1. Faulk C. De novo sequencing, diploid assembly, and annotation of the black carpenter ant, Camponotus pennsylvanicus, and its symbionts by one person for $1000, using nanopore sequencing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023; 51:17–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. He K., Minias P., Dunn P.O.. Long-read genome assemblies reveal extraordinary variation in the number and structure of MHC loci in birds. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021; 13:evaa270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Rhie A., McCarthy S.A., Fedrigo O., Damas J., Formenti G., Koren S., Uliano-Silva M., Chow W., Fungtammasan A., Kim J.et al.. Towards complete and error-free genome assemblies of all vertebrate species. Nature. 2021; 592:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hotaling S., Sproul J.S., Heckenhauer J., Powell A., Larracuente A.M., Pauls S.U., Kelley J.L., Frandsen P.B.. Long reads are revolutionizing 20 years of insect genome sequencing. Genome Biol. Evol. 2021; 13:evab138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Runnel K., Abarenkov K., Copot O., Mikryukov V., Koljalg U., Saar I., Tedersoo L.. DNA barcoding of fungal specimens using PacBio long-read high-throughput sequencing. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2022; 22:2871–2879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lewin H.A., Richards S., Lieberman Aiden E., Allende M.L., Archibald J.M., Balint M., Barker K.B., Baumgartner B., Belov K., Bertorelle G.et al.. The Earth BioGenome Project 2020: starting the clock. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2022; 119:e2115635118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ekblom R., Galindo J.. Applications of next generation sequencing in molecular ecology of non-model organisms. Heredity (Edinb.). 2011; 107:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hongoh Y., Toyoda A.. Whole-genome sequencing of unculturable bacterium using whole-genome amplification. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011; 733:25–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Montoliu-Nerin M., Sanchez-Garcia M., Bergin C., Grabherr M., Ellis B., Kutschera V.E., Kierczak M., Johannesson H., Rosling A.. Building de novo reference genome assemblies of complex eukaryotic microorganisms from single nuclei. Sci. Rep. 2020; 10:1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Deleye L., Tilleman L., Vander Plaetsen A.S., Cornelis S., Deforce D., Van Nieuwerburgh F.. Performance of four modern whole genome amplification methods for copy number variant detection in single cells. Sci. Rep. 2017; 7:3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Santoro A.E., Kellom M., Laperriere S.M.. Contributions of single-cell genomics to our understanding of planktonic marine archaea. Philos. Trans. R Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019; 374:20190096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sahraei S.E., Sanchez-Garcia M., Montoliu-Nerin M., Manyara D., Bergin C., Rosendahl S., Rosling A.. Whole genome analyses based on single, field collected spores of the arbuscular mycorrhizal fungus Funneliformis geosporum. Mycorrhiza. 2022; 32:361–371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lepere C., Demura M., Kawachi M., Romac S., Probert I., Vaulot D. Whole-genome amplification (WGA) of marine photosynthetic eukaryote populations. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2011; 76:513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Nyaku S.T., Sripathi V.R., Lawrence K., Sharma G.. Characterizing repeats in two whole-genome amplification methods in the reniform nematode genome. Int. J. Genomics. 2021; 2021:5532885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eccles D., Chandler J., Camberis M., Henrissat B., Koren S., Le Gros G., Ewbank J.J.. De novo assembly of the complex genome of Nippostrongylus brasiliensis using MinION long reads. BMC Biol. 2018; 16:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Dillman A.R., Mortazavi A., Sternberg P.W.. Incorporating genomics into the toolkit of nematology. J. Nematol. 2012; 44:191–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dieterich C., Sommer R.J.. How to become a parasite—lessons from the genomes of nematodes. Trends Genet. 2009; 25:203–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Larsen B.B., Miller E.C., Rhodes M.K., Wiens J.J.. Inordinate fondness multiplied and redistributed: the number of species on Earth and the new pie of life. Q. Rev. Biol. 2017; 92:229–265. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Smythe A.B., Holovachov O., Kocot K.M.. Improved phylogenomic sampling of free-living nematodes enhances resolution of higher-level nematode phylogeny. BMC Evol. Biol. 2019; 19:121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Blaxter M.L., De Ley P., Garey J.R., Liu L.X., Scheldeman P., Vierstraete A., Vanfleteren J.R., Mackey L.Y., Dorris M., Frisse L.M.et al.. A molecular evolutionary framework for the phylum Nematoda. Nature. 1998; 392:71–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De Ley P. A quick tour of nematode diversity and the backbone of nematode phylogeny. WormBook. 2006; 1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kern E.M.A., Kim T., Park J.K.. The mitochondrial genome in nematode phylogenetics. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2020; 8: 10.3389/fevo.2020.00250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. The C. elegans Sequencing Consortium Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998; 282:2012–2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kikuchi T., Eves-van den Akker S., Jones J.T.. Genome evolution of plant-parasitic nematodes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 2017; 55:333–354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Mahfouz M.M., Abd-Elgawad T.H.A.. Impact of Phytonematodes on Agriculture Economy. 2015; Wallingford, UK: CAB International. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Xie Y., Zhang P., Xue B., Cao X., Ren X., Wang L., Sun Y., Yang H., Zhang L.. Establishment of a marine nematode model for animal functional genomics, environmental adaptation and developmental evolution. 2020; bioRxiv doi:07 March 2020, preprint: not peer reviewed 10.1101/2020.03.06.980219. [DOI]

- 27. Gingold R., Moens T., Rocha-Olivares A.. Assessing the response of nematode communities to climate change-driven warming: a microcosm experiment. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e66653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Moens T., Vincx M.. Temperature, salinity and food thresholds in two brackish-water bacterivorous nematode species: assessing niches from food absorption and respiration experiments. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2000; 243:137–154. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Viney M. How can we understand the genomic basis of nematode parasitism?. Trends Parasitol. 2017; 33:444–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Meldal B.H., Debenham N.J., De Ley P., De Ley I.T., Vanfleteren J.R., Vierstraete A.R., Bert W., Borgonie G., Moens T., Tyler P.A.et al.. An improved molecular phylogeny of the Nematoda with special emphasis on marine taxa. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007; 42:622–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Bik H.M., Lambshead P.J., Thomas W.K., Lunt D.H.. Moving towards a complete molecular framework of the Nematoda: a focus on the Enoplida and early-branching clades. BMC Evol. Biol. 2010; 10:353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ahmed M., Roberts N.G., Adediran F., Smythe A.B., Kocot K.M., Holovachov O.. Phylogenomic analysis of the phylum nematoda: conflicts and congruences with morphology, 18S rRNA, and mitogenomes. Front Ecol. Evol. 2022; 9: 10.3389/fevo.2021.769565. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Marcais G., Kingsford C.. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics. 2011; 27:764–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ranallo-Benavidez T.R., Jaron K.S., Schatz M.C.. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nat. Commun. 2020; 11:1432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Li H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics. 2018; 34:3094–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Warris S., Schijlen E., van de Geest H., Vegesna R., Hesselink T., Te Lintel Hekkert B., Sanchez Perez G., Medvedev P., Makova K.D., de Ridder D. Correcting palindromes in long reads after whole-genome amplification. BMC Genomics. 2018; 19:798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kolmogorov M., Yuan J., Lin Y., Pevzner P.A.. Assembly of long, error-prone reads using repeat graphs. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019; 37:540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vaser R., Sovic I., Nagarajan N., Sikic M.. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res. 2017; 27:737–746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hu J., Fan J., Sun Z., Liu S.. NextPolish: a fast and efficient genome polishing tool for long-read assembly. Bioinformatics. 2020; 36:2253–2255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Huang S., Kang M., Xu A.. HaploMerger2: rebuilding both haploid sub-assemblies from high-heterozygosity diploid genome assembly. Bioinformatics. 2017; 33:2577–2579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Simao F.A., Waterhouse R.M., Ioannidis P., Kriventseva E.V., Zdobnov E.M.. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015; 31:3210–3212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Quinlan A.R., Hall I.M.. BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26:841–842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Bankevich A., Nurk S., Antipov D., Gurevich A.A., Dvorkin M., Kulikov A.S., Lesin V.M., Nikolenko S.I., Pham S., Prjibelski A.D.et al.. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 2012; 19:455–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Buchfink B., Reuter K., Drost H.-G.. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods. 2021; 18:366–368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. De Vivo M., Lee H.-H., Huang Y.-S., Dreyer N., Fong C.-L., de Mattos F.M.G., Jain D., Wen Y.-H.V., Mwihaki J.K., Wang T.-Y.et al.. Utilisation of Oxford Nanopore sequencing to generate six complete gastropod mitochondrial genomes as part of a biodiversity curriculum. Sci. Rep. 2022; 12:9973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Bernt M., Donath A., Juhling F., Externbrink F., Florentz C., Fritzsch G., Putz J., Middendorf M., Stadler P.F.. MITOS: improved de novo metazoan mitochondrial genome annotation. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2013; 69:313–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Mikheenko A., Prjibelski A., Saveliev V., Antipov D., Gurevich A.. Versatile genome assembly evaluation with QUAST-LG. Bioinformatics. 2018; 34:i142–i150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Serra L., Chang D.Z., Macchietto M., Williams K., Murad R., Lu D., Dillman A.R., Mortazavi A.. Adapting the Smart-seq2 protocol for robust single worm RNA-seq. Bio. Protoc. 2018; 8:e2729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bolger A.M., Lohse M., Usadel B.. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014; 30:2114–2120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Flynn J.M., Hubley R., Goubert C., Rosen J., Clark A.G., Feschotte C., Smit A.F.. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020; 117:9451–9457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Edgar R.C. Search and clustering orders of magnitude faster than BLAST. Bioinformatics. 2010; 26:2460–2461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Howe K.L., Bolt B.J., Shafie M., Kersey P., Berriman M.. WormBase ParaSite—a comprehensive resource for helminth genomics. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2017; 215:2–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Dobin A., Gingeras T.R.. Mapping RNA-seq reads with STAR. Curr. Protoc. Bioinformatics. 2015; 51:11.14.1–11.14.19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Bruna T., Hoff K.J., Lomsadze A., Stanke M., Borodovsky M.. BRAKER2: automatic eukaryotic genome annotation with GeneMark-EP+ and AUGUSTUS supported by a protein database. NAR Genom. Bioinform. 2021; 3:lqaa108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Pertea G., Pertea M.. GFF utilities: gffRead and GffCompare. F1000Res. 2020; 9:ISCB Comm J-304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Wood D.E., Lu J., Langmead B.. Improved metagenomic analysis with Kraken 2. Genome Biol. 2019; 20:257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Emms D.M., Kelly S.. OrthoFinder: solving fundamental biases in whole genome comparisons dramatically improves orthogroup inference accuracy. Genome Biol. 2015; 16:157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Katoh K., Standley D.M.. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013; 30:772–780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Piñeiro C., Abuín J.M., Pichel J.C.. Very Fast Tree: speeding up the estimation of phylogenies for large alignments through parallelization and vectorization strategies. Bioinformatics. 2020; 36:4658–4659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang C., Scornavacca C., Molloy E.K., Mirarab S.. ASTRAL-Pro: quartet-based species-tree inference despite paralogy. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2020; 37:3292–3307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Carlton P.M., Davis R.E., Ahmed S.. Nematode chromosomes. Genetics. 2022; 221:iyac014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Blainey P.C., Quake S.R.. Digital MDA for enumeration of total nucleic acid contamination. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011; 39:e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sidore A.M., Lan F., Lim S.W., Abate A.R.. Enhanced sequencing coverage with digital droplet multiple displacement amplification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016; 44:e66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kim S.C., Premasekharan G., Clark I.C., Gemeda H.B., Paris P.L., Abate A.R.. Measurement of copy number variation in single cancer cells using rapid-emulsification digital droplet MDA. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 2017; 3:17018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Tyson J.R., O’Neil N.J., Jain M., Olsen H.E., Hieter P., Snutch T.P.. MinION-based long-read sequencing and assembly extends the Caenorhabditis elegans reference genome. Genome Res. 2018; 28:266–274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Lai C.K., Lee Y.C., Ke H.M., Lu M.R., Liu W.A., Lee H.H., Liu Y.C., Yoshiga T., Kikuchi T., Chen P.J.et al.. The Aphelenchoides genomes reveal substantial horizontal gene transfers in the last common ancestor of free-living and major plant-parasitic nematodes. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 2023; 23:905–919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Arroyo Muhr L.S., Lagheden C., Hassan S.S., Kleppe S.N., Hultin E., Dillner J.. De novo sequence assembly requires bioinformatic checking of chimeric sequences. PLoS One. 2020; 15:e0237455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lasken R.S., Stockwell T.B.. Mechanism of chimera formation during the Multiple Displacement Amplification reaction. BMC Biotechnol. 2007; 7:19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Calus S.T., Ijaz U.Z., Pinto A.J.. NanoAmpli-Seq: a workflow for amplicon sequencing for mixed microbial communities on the nanopore sequencing platform. Gigascience. 2018; 7:giy140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Muller B., Jones C., West S.C.. T7 endonuclease I resolves Holliday junctions formed in vitro by RecA protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990; 18:5633–5636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Yoshimura J., Ichikawa K., Shoura M.J., Artiles K.L., Gabdank I., Wahba L., Smith C.L., Edgley M.L., Rougvie A.E., Fire A.Z.et al.. Recompleting the Caenorhabditis elegans genome. Genome Res. 2019; 29:1009–1022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Pertea M., Pertea G.M., Antonescu C.M., Chang T.C., Mendell J.T., Salzberg S.L.. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015; 33:290–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Wang J., Gao S., Mostovoy Y., Kang Y., Zagoskin M., Sun Y., Zhang B., White L.K., Easton A., Nutman T.B.et al.. Comparative genome analysis of programmed DNA elimination in nematodes. Genome Res. 2017; 27:2001–2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Ma M.Y., Xia J., Shu K.X., Niu D.K.. Intron losses and gains in the nematodes. Biol. Direct. 2022; 17:13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Coghlan A., Tyagi R., Cotton J.A., Holroyd N., Rosa B.A., Tsai I.J., Laetsch D.R., Beech R.N., Day T.A., Hallsworth-Pepin K.et al.. Comparative genomics of the major parasitic worms. Nat. Genet. 2019; 51:163–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Hyman B.C., Lewis S.C., Tang S., Wu Z.. Rampant gene rearrangement and haplotype hypervariation among nematode mitochondrial genomes. Genetica. 2011; 139:611–615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Szitenberg A., Cha S., Opperman C.H., Bird D.M., Blaxter M.L., Lunt D.H.. Genetic drift, not life history or RNAi, determine long-term evolution of transposable elements. Genome Biol. Evol. 2016; 8:2964–2978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Smith M.L., Vanderpool D., Hahn M.W.. Using all gene families vastly expands data available for phylogenomic inference. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2022; 39:msac112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Stevens L., Martinez-Ugalde I., King E., Wagah M., Absolon D., Bancroft R., de laRosa P.G., Hall J.L., Kieninger M., Kloch A.et al.. Ancient diversity in host–parasite interaction genes in a model parasitic nematode. 2023; bioRxiv doi:17 April 2023, preprint: not peer reviewed 10.1101/2023.04.17.535870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80. Kiguchi Y., Nishijima S., Kumar N., Hattori M., Suda W.. Long-read metagenomics of multiple displacement amplified DNA of low-biomass human gut phageomes by SACRA pre-processing chimeric reads. DNA Res. 2021; 28:dsab019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Hård J., Mold J.E., Eisfeldt J., Tellgren-Roth C., Häggqvist S., Bunikis I., Contreras-Lopez O., Chin C.-S., Nordlund J., Rubin C.-J.et al.. Long-read whole genome analysis of human single cells. 2023; bioRxiv doi:23 January 2023, preprint: not peer reviewed 10.1101/2021.04.13.439527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 82. Doyle S.R., Sankaranarayanan G., Allan F., Berger D., Jimenez Castro P.D., Collins J.B., Crellen T., Duque-Correa M.A., Ellis P., Jaleta T.G.et al.. Evaluation of DNA extraction methods on individual helminth egg and larval stages for whole-genome sequencing. Front. Genet. 2019; 10:826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Bogale M., Baniya A., DiGennaro P.. Nematode identification techniques and recent advances. Plants (Basel). 2020; 9:1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Subbotin S.A., Oliveira C.J., Alvarez-Ortega S., Desaeger J.A., Crow W., Overstreet C., Leahy R., Vau S., Inserra R.N.. The taxonomic status of Aphelenchoides besseyi Christie, 1942 (Nematoda: aphelenchoididae) populations from the southeastern USA, and description of Aphelenchoides pseudobesseyi sp. n. Nematology. 2021; 23:381–413. [Google Scholar]

- 85. Van Hien H., Thi Dung B., Ngo H.D., Doanh P.N.. First morphological and molecular identification of third-stage larvae of Anisakis typica (Nematoda: anisakidae) from marine fishes in Vietnamese water. J. Nematol. 2021; 53:e2021-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Tsai I.J., Hunt M., Holroyd N., Huckvale T., Berriman M., Kikuchi T.. Summarizing specific profiles in Illumina sequencing from whole-genome amplified DNA. DNA Res. 2014; 21:243–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Denton J.F., Lugo-Martinez J., Tucker A.E., Schrider D.R., Warren W.C., Hahn M.W.. Extensive error in the number of genes inferred from draft genome assemblies. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2014; 10:e1003998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Bai X., Adams B.J., Ciche T.A., Clifton S., Gaugler R., Kim K.S., Spieth J., Sternberg P.W., Wilson R.K., Grewal P.S.. A lover and a fighter: the genome sequence of an entomopathogenic nematode Heterorhabditis bacteriophora. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e69618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. McLean F., Berger D., Laetsch D.R., Schwartz H.T., Blaxter M.. Improving the annotation of the Heterorhabditis bacteriophora genome. Gigascience. 2018; 7:giy034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All sequences generated from this study were deposited on the NCBI under BioProject PRJNA953805, and the Biosample accession number of the free-living nematodes can be found in Supplementary Table S3. The assemblies and annotations of the 13 free-living species are also available in the WormBase ParaSite ftp (https://ftp.ebi.ac.uk/pub/databases/wormbase/parasite/datasets/PRJNA953805/). The scripts and proteome data are available in Github page: https://yichienlee1010.github.io/Single-nematode-genome/ (permanent doi: https://zenodo.org/record/8144614).