Abstract

This reviews the transition of remote monitoring of patients with cardiac electronic implantable devices from curiosity to standard of care. This has been delivered by technology evolution from patient-activated remote interrogations at appointed intervals to continuous monitoring that automatically flags clinically actionable information to the clinic for review. This model has facilitated follow-up and received professional society recommendations. Additionally, continuous monitoring has provided a new level of granularity of diagnostic data enabling extension of patient management from device to disease management. This ushers in an era of digital medicine with wider applications in cardiovascular medicine.

Keywords: Defibrillators, Patient monitoring, Follow-up, Remote monitoring, Guidelines

Introduction

The year 2023 marks the 25th year of Europace Journal and also the 10th anniversary of a prescient Europace special issue recognizing the technological revolution of automatic remote monitoring (RM) of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices (CIEDs).1 The pioneering unit was a mobile cellular phone that relayed CIED diagnostic data gathered daily to a service centre that then forwarded clinically actionable information to the clinic for review. The system provided a new level of granularity of details regarding device function and arrhythmia burden and flagged critical issues for immediate attention. The issue anticipated how this model would facilitate CIED follow-up, set the standard of care, and usher in an era of digital medicine with wider applications in cardiovascular medicine.2,3 Here, we review the progress in the last decade.4–6

Technical advances

The last two decades have witnessed evolution of remote technologies from intermittent patient activated to automatic systems that test every day, changing the paradigm of remote patient management from remote follow-up to continuous RM.

The concept of remote management of CIEDs was born in the early 1970s.7 Remote pacemaker follow-up was initially done through trans-telephonic transmissions (TTMs).4,8 It enabled a restricted interrogation providing rate, rhythm, and device integrity (mainly battery status). Its main efficiency was for CIEDs approaching battery elective replacement interval. It could not detect intermittent problems nor retrieve diagnostic data or rule out device and lead malfunction and therefore could not replace in-office visits.

In the 1990s, a more advanced form of TTM was tested in implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs) and was effectively the precursor to modern remote follow-up.9 The TTM transmitters contained metal bracelets and interrogation heads placed over the ICDs and, when connected to the telephone headset, allowed automatic transmission to the device clinic with a wealth of information including pacing parameters, tachycardia detection criteria and treatment, battery status, last charge time, episode counter, and therapy logs for ventricular tachycardia (VT)/(VF) ventricular fibrillation.

An advance in CIED-based inductive technology allowed for remote interrogation (RI) through wand-based radiofrequency data transfer, in a similar fashion to in-office visits.8,10 When used, data were transferred from the patient’s CIED via a home transceiver through phone lines or cellular/wireless connections to a remote storage server that could be accessed remotely by the caregivers. Further technological advance allowed for the introduction of an automated RM system that transmits daily data via a transceiver located next to the patient.11,12 More recently, low-energy Bluetooth technology allows coupling the CIED with the patient’s smartphone, further enhancing connectivity.

Contemporary remote management of patients with CIED involves remote follow-up in which a scheduled device interrogation is performed and RM that automatically transmits alert events and patient-initiated interrogation, which are usually initiated due to concern of device malfunction or suspected arrhythmia or another clinical event.5,13

Several factors must be taken into account when integrating wireless technology to CIEDs. The first is limiting the power consumption of the system so as not to affect battery longevity significantly (one proprietary technology is associated with minimal drain14). Communication range of the device is a compromise as longer ranges require more power. Most CIED wireless systems work well within a 3 m range. Similarly, the rate of data transfer must be considered as faster rates require more power and more sophisticated and costly designs. Size is important when dealing with compact implantable devices such as CIEDs, and the antenna can have an important effect on the overall device dimensions. Finally, another important consideration when dealing with wireless technology is the surrounding environment and potential interference by other radiofrequency sources. Most CIEDs utilize the medical implant communication service (MICS) band at approximately 400 MHz frequency. The MICS is an unlicensed, ultralow-power (ULP) mobile radio service for transmitting data in implanted medical devices, thus avoiding interference with other users of the radio spectrum. Each manufacturer has its own implementation of this standard in their proprietary hardware and software, and it is therefore not compatible between vendors. Low-energy Bluetooth is a paradigm shift as connectivity is no longer solely controlled by the device manufacturer but also by the patient's mobile phone and operating system manufacturer (see section below).

Remote device follow-up

Traditionally, post-implant follow-up was conducted in person according to calendar-based intervals. The frequency of 3 monthly ICD interrogations was based on the need to manually reform the capacitor and check battery and lead integrity from first-generation devices. This has been unnecessary for decades since CIEDs are reliable and component failure is infrequent.15 At the same time, the workload associated with routine follow-up has become challenging in view of increasing volume of implants and data transfer.

Remote patient management is an appealing solution. Remote interrogations promised patients easier access (e.g. from remote locations) and hospitals reduced in-clinic load. However, coordination of 3 monthly checks with patient consumed time.16 Moreover, this model continued calendar-based appointments that do not detect potentially serious problems occurring between interrogations. Automatic RM changed the paradigm, providing a mechanism for continuous surveillance of an ambulatory population with CIEDs and virtually immediate alert-based notification of changes in device (or patient) condition, even if asymptomatic, e.g. failure of an ICD to properly charge its capacitors and deliver appropriate therapy,17 inappropriate VT detection caused by supraventricular tachycardia, or development of atrial fibrillation (AF).18

The large randomized TRUST trial demonstrated that continuous RM reduced the load of in-clinic evaluations by almost 50% (principally by reducing non-actionable routine device evaluations) while maintaining patient safety.19 This resulted in more efficient deployment of clinic resources to those patients who needed to be seen.20 Counterintuitively, patient retention to follow-up was improved.6 Additionally, TRUST confirmed superiority of automatic RM to conventional care for maintaining adherence to 3 monthly checks and for detecting abnormalities as and when they occurred, mostly the same day.12,19,21,22 This might be critical, e.g. for battery or lead failure (Figures 1 and 2).23 In comparison, conventional care under-reported occurrence of ICD dysfunction and discovered these events late (47% of all detected events were asymptomatic) (Figures 3). This led to the recommendation of RM for management of advisories that centre around disintegration of high-voltage circuitry, battery depletion, and lead failure and are captured by event triggers.24 In comparison, intensifying surveillance with conventional detection methods, such as increasing the frequency of office visits, e.g. monthly,25 is impractical, onerous, and inefficient since problem incidence is low and denominators high.

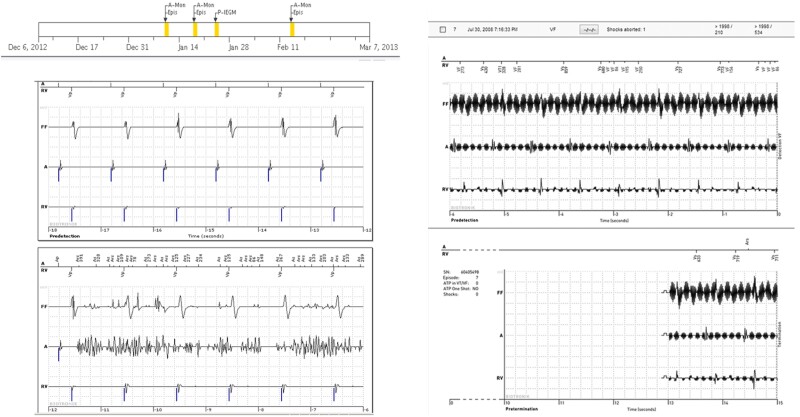

Figure 1.

(Left) Event notifications suggestive of AF (top) but accompanying wirelessly transmitted intra-cardiac electrograms indicate that the abnormality was caused by lead noise (likely fracture-related) permitting the diagnosis of a false positive mode switch. (Right) Event notification received for an aborted shock (7:16 p.m.) with an automatic wirelessly transmitted electrogram showing non-physiological signals due to electromagnetic interference. The subject was asymptomatic but, in response to the notification, was seen in office within 24 h (compiled with permission from Varma et al.23).

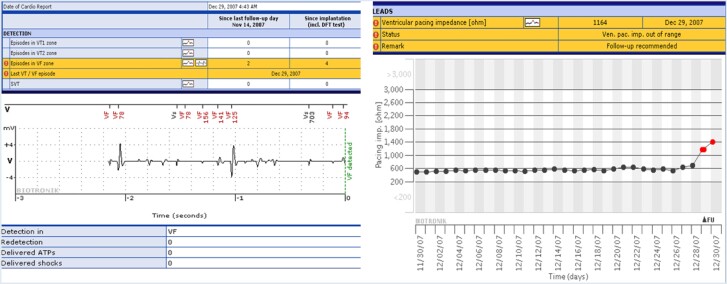

Figure 2.

Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator generator with automatic wireless remote monitoring coupled to a Fidelis (MDT 6949) lead. Two event notifications that were transmitted immediately on occurrence of lead fracture, occurring silently during sleep at 4:43 a.m., 6 weeks after last clinic follow-up on 14 November. (Left panel) Wirelessly transmitted electrograms demonstrated irregular sensed events (coupling intervals as short as 78 ms) with VF detection (marked). No therapy was delivered. (Right panel) A separate notification for the same event indicating a lead impedance alert. Electrogram definition was modest in first-generation device (compiled with permission from Varma24).

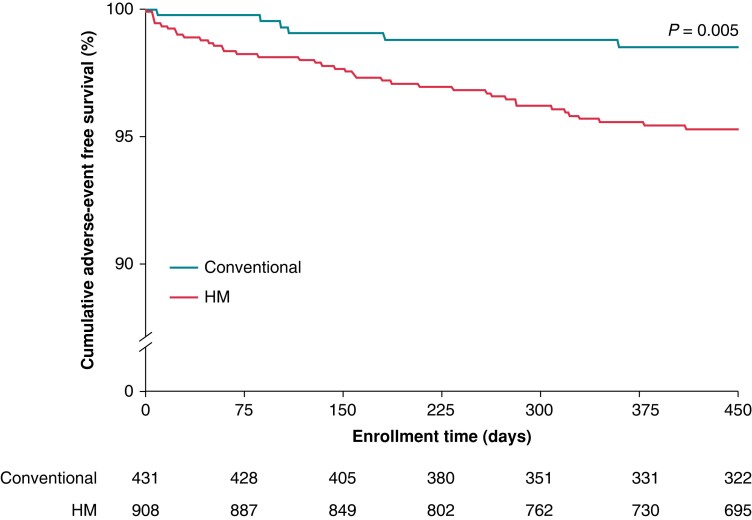

Figure 3.

Event free survival rates in HM compared with conventional care in the TRUST cohort. Protocol required event notifications were system related (end of service, elective replacement indicator, atrial impedance <250 or >1500 Ohm, ventricular impedance <250 or >1500 Ohm, daily shock impedance <30 or >100 Ohm, and shock impedance <25 or >110 Ohm); arrhythmia-related events (atrial burden > 10%, supraventricular tachycardia detected, VT1 detected, VT2 detected, and VF detected), and ineffective ventricular maximum energy shock (notified on first shock of any sequence in a given episode) (compiled with permission from Varma et al.23).

The roles of RM extend beyond managing clinic workload and device integrity. Effective follow-up should aim to identify ‘actionable’ interrogations and trigger adequate reactions. Reprogramming changes accounted for the majority of ‘actionable’ interrogations in the TRUST trial.19 Arrhythmia management may be facilitated. In the multi-centre ECOST trial, clinical reactions enabled by early detection resulted in a large reduction in the number of actually delivered shocks (−72%), the number of charged shocks (−76%), the rate of inappropriate shocks (−52%), and at the same time exerting a favourable impact on battery longevity (also noted in TRUST).14,26 This was confirmed in meta-analysis27 although more recent studies suggested lesser effects.28–30 This finding may be related to contemporary better ICD programming, although adoption of recommended settings is surprisingly deficient.31 Repeated adenosine triphosphate (ATP) delivery may herald a preventable shock32,33 and, if notified early, presents an opportunity for intervention (but not all RM platforms alert for this34). Inappropriate shocks related to ICD lead fractures may be reduced by RM.35

The ability to collect detailed device-specific data, with component function assessed daily, sets a precedent for longitudinal evaluation of lead and generator performance. Artificial intelligence (AI) may improve prediction of significant events, e.g. future VT storm and ICD shocks,36,37 and detection of lead failure38 by a combination of two or more parameter deviations. Although TRUST showed that a core set of alerts generated a minimal load,39 AI may be especially important for managing the large load of false positives associated with implantable loop recorder (ILR) management.40

The results have led to professional societies strongly recommending RM in preference to conventional in-person evaluation for CIED follow-up over the last decade.5,6,26,41–43 Automatic continuous RM represents an early warning system that can provide assurance to both patients and their physicians.

Disease management: atrial fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation detection

Remote monitoring of patients with CIEDs facilitates the early AF detection and quantification and calculates arrhythmia burden.19,44–46 That is particularly meaningful for asymptomatic (‘silent’) AF and for patients without any prior AF history, 30% of whom develop newly detected AF.47–49 In cryptogenic stroke patients, AF detection rate by implantable cardiac monitors ranges from 15% to 30% and is a function of monitoring duration.50 Detection of AF occurs 1–5 months earlier with RM vs. conventional follow-up. Remote monitoring has a sensitivity of nearly 95% for true AF detection,46 and approximately 90% of AF episodes that trigger alerts are asymptomatic. Early AF detection promises earlier treatment, potentially preventing adverse events such as stroke, shock therapy, and heart failure (HF).51 Remote monitoring can enable tailored and dynamic patient treatment pathways52–54 and assess success rates of AF therapies.

Atrial fibrillation burden and atrial fibrillation progression

Remote monitoring provides a chronologic plot of all AF events and their individual durations, accompanying intra-cardiac electrograms, AF burden trends, and associated ventricular rates. Insights into temporal patterns may be instructive; e.g. paroxysmal AF comprises heterogeneous entities.55 Thus, in self-terminating AF, the AF burden is low and determined by number of co-morbidities. Atrial fibrillation progression occurred in approximately 25% of patients.56 Patients with either predominant nocturnal or daytime onset of AF episodes had less associated co-morbidities and less AF progression compared with that of patients with mixed onset of AF.57

Atrial fibrillation alert setting should be modified during follow-up for individual patients according to their individual clinical profile in order to identify clinically meaningful events (otherwise daily alerts for single short episodes may increase clinic work burden).58 In patients with permanent AF, all alerts should be switched off and only ventricular rate should be monitored.

Risk stratification

Continuous atrial rhythm monitoring may predict AF onset and, in combination with clinical data and risk scores, may improve patient risk stratification for major clinical events. The daily number of premature atrial complexes significantly increased in the 5 days preceding the AF onset.59 In a CIED population without previous clinical AF, atrial high rate episode (AHRE) incidence increased with a higher CHA2DS2-VASc score. The association was stronger with longer episodes, even if the accuracy of CHA2DS2-VASc as a predictor was moderate.60 In ICD patients, AHREs were an independent predictor of sustained ventricular arrhythmias at 30 days and that patients with ventricular arrhythmias preceded by AHRE had a worse long-term survival.61 Remote monitoring enabled reduction in AF-related inappropriate ICD shocks in the ECOST randomized trial.26 Mean ventricular heart rate monitoring62 may further improve inappropriate shock prevention.

Stroke prevention

Early detection of AF creates a unique opportunity for pre-emptive intervention aimed at preventing stroke, particularly in asymptomatic patients. However, evidence is scarce. Monte Carlo simulations based on a real population63 suggested that daily monitoring could reduce the 2-year stroke risk by 18%. A sub-analysis of the randomized COMPAS trial42 showed a significant reduction of hospitalizations for atrial arrhythmias and related stroke in the RM group. In the HomeGuide Registry64 (1650 patients), stroke incidence at 4 years was extremely low, lower than that expected for the estimated thromboembolic risk profile of the enrolled population. However, the randomized IMPACT trial65 testing oral anticoagulation therapy for AF guided by RM reported no difference in stroke or all-cause mortality in the RM-guided intervention group. In fact, since the study protocol called for discontinuation of oral anticoagulation if there was no AF for 30 or 90 days, according to individual risk profile, the majority of patients were not anticoagulated at the index event. Furthermore, a proximate temporal relationship of device-detected atrial arrhythmias to the occurrence of strokes was lacking; i.e. the mechanism of stroke is not solely related to the AF episodes. The safety of discontinuation of anticoagulation in any sub-groups of AF patients has to be considered carefully.

Recently, a meta-analysis of 16 randomized trials, including studies enrolling CIED patients and studies on wearable devices, demonstrated that, compared with patients receiving standard follow-up, patients undergoing RM had a significantly higher detection rate of atrial arrhythmia and a lower risk of stroke. The lower risk of stroke was only noted in patients with CIEDs [risk ratio (RR) 0.513; 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.265–0.996].66 Future results from the randomized controlled NOAH-AFNET67 and ARTESiA68 trials may provide guidance of anticoagulation strategy in high-risk CIED patients with AHRE for stroke prevention.

Atrial fibrillation and heart failure

A strong association has been observed between AF and hard clinical endpoints in patients with HF.69,70 Unrecognized AF may exacerbate HF, increase frequency of hospitalizations, lead to loss of cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and inappropriate ICD shocks, increase sympathetic tone, and induce haemodynamic compromise and thromboembolism. Remote monitoring has the potential of impacting patient outcome by early detection and continuous monitoring of AF. Evidence of these benefits has yet to be confirmed by randomized studies.

Disease management: heart failure

There are several means by which RM of CIEDs may improve HF management.71,72 First, continuous recording of device-derived variables can enable alerts on imminent fluid decompensation. Since volume overload decompensations are typically preceded by a gradual fluid accumulation over several weeks prior to the acute clinical event, RM during this period may provide early warning to enable timely pre-emptive interventions and avoid harmful clinical events. Second, regular evaluation of multiple diagnostic parameters may add valuable information to the clinical assessment of ambulatory HF patients73 and, thus, facilitate the triage into different risk categories for individualized follow-up.74,75 Third, by enabling patients to interpret and respond to their own physiological data, RM offers a tool to enhance patient empowerment and self-care.76,77

Several device-based sensors obtain information potentially relevant to HF management, including intra-thoracic impedance,78–80 heart rate and heart rate variability,81 physical activity,82 minute ventilation,83 heart sound amplitude84 in addition to arrhythmia detection, and statistics on the percentage of biventricular stimulation in CRT patients. Single use of these sensors, however, is associated with sub-optimal sensitivity and specificity to predict HF decompensation, as shown in the example of impedance-based fluid detection.85 However, Boehmer et al.86 demonstrated that a multi-sensor algorithm combining heart rate, heart sounds, thoracic impedance, respiration, and activity can markedly improve diagnostic accuracy with a sensitivity of 70% to predict HF events, which is balanced against an unexplained alert rate of 1.47 per patient and year.

More recently, D'Onofrio et al.87 developed and validated a longitudinal predictor for worsening HF events by combining information from seven different sensors obtained by RM. The Seattle HF model was used to risk-stratify patients at baseline. The algorithm showed promising sensitivity of predicting HF events by 65.5% (CI 45.7–82.1%) at a median alerting time of 42 days [interquartile range (IQR) 21–89], and a false (or unexplained) alert rate of 0.69 (CI 0.64–0.74) or 0.63 (CI 0.58–0.68). The clinical effectiveness of these algorithms remains to be confirmed in prospective outcome trials.

Remote monitoring and heart failure outcomes

Despite early promise from real-world data,29,88 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses evaluating the effect of RM on survival have been largely neutral27,89 (although associated with a marked reduction in planned hospital visits and lower costs90). In MORE-CARE, randomizing 865 CRT with defibrillator (CRT-D) patients, the composite of death, cardiovascular, and device-related hospitalization was similar between groups [hazard ratio (HR) 1.02, P = 0.89].91 Likewise, the OptiLink trial, including 1002 patients with ICD or CRT-D, failed to show an improvement of all-cause death and cardiovascular hospitalization (HR 0.87, P = 0.13).92 Remote management of heart failure, including 1650 patients,93 did not find a difference in the composite of death and unplanned cardiovascular hospitalization (HR 1.01, P = 0.87). By confirming the non-inferiority of RM to routine in-clinic visits in terms of clinical outcomes, a recent study provided evidence that routine in-person follow-up can be safely substituted by RM.28 Nevertheless, such a follow-up strategy does not necessarily improve patient-reported health status and ICD acceptance.94

Interestingly, the IN-TIME trial, using daily multi-parameter telemonitoring in ICD patients, marks an impressive exception.95 The primary endpoint, a composite clinical score combining all-cause death, overnight HF admissions, changes in New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and in-patient global self-assessment, was improved by telemonitoring (odds ratio 0.63, 95% CI 0.43–0.90). Furthermore, a reduction in the secondary endpoint of all-cause mortality (HR 0.36, 95% CI 0.17–0.74, P = 0.004) and cardiovascular mortality (HR 0.37, 95% CI 0.16–0.83, P = 0.012) was found. These results were largely driven by the prevention of worsening HF events96 suggesting that patients with more severe HF may gain a greater clinical benefit of RM.97 Similarly, HF management based on home transmission of haemodynamic data from a pulmonary artery pressure sensor significantly decreased hospital admission rates for HF (HR 0.64, 95% CI 0.55–0.75, P < 0.0001) and also in a sub-group of CRT non-responders with severe HF.98 Common to these positive studies was a RM strategy employing daily transfer of data. While a larger trial failed to reproduce effects on mortality and HF events,99 these results were likely compromised by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic.100 In the future, pressure monitoring may possibly be used to fine-tune the programming of other HF devices.101

Workflow, resource consumption, and patient satisfaction

Workflow

Incorporating CIED RM in standard clinical practice is challenging and requires dedicated and structured workflow models and infrastructures. This is necessary to capitalize on the early detection (‘same day') power of continuous monitoring (Figure 4). An integrated working group, comprising allied professionals (nurses and technicians), physicians, and ancillary staff with well-defined roles and responsibilities and dedicated time, space, and equipment, is necessary.102 Allied professionals are mainly responsible for continuity of care. More specifically, their duties include patient training and education, website data entry, remote data review, data screening, critical case submission to the physician, contacting patients, and checking patient compliance and therapy benefits.103 They need to be experts and continuously updated on CIED technology and ideally have the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) or International Board of Heart Rhythm Examiners (IBHRE) certification of competence (or equivalent). The physicians (usually an expert electrophysiologist) are responsible for informed consent, overview and monitoring of the full process, and patient clinical management. The ancillary staff may assist the clinical staff in scheduling appointments, checking patient connectivity, communicating results, billing, and update of patient electronic files. The RM working group should interact with other instances, in particular with HF and emergency care specialists, general practitioners, service providers, and referral hospitals. This model has been found to be highly effective, safe, and efficient in the Italian HomeGuide Registry46,104 and has been recommended in the 2015 HRS Consensus Document on RM8 and in the 2020 position paper of the Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiac Pacing (AIAC).105

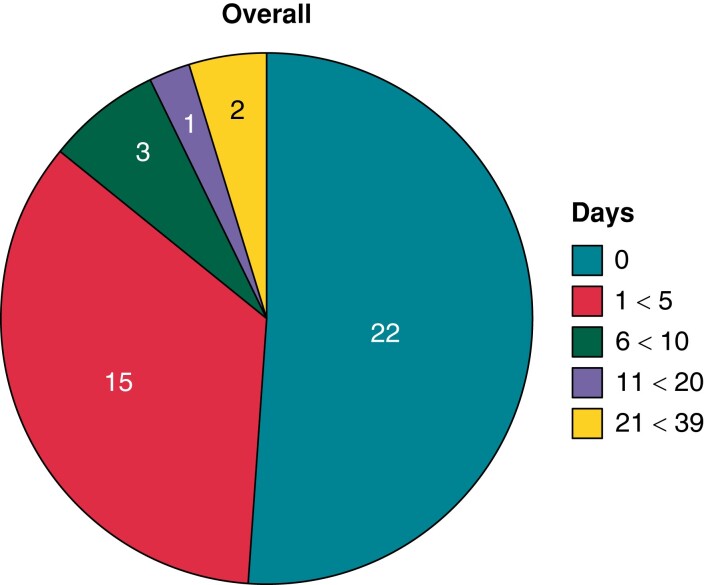

Figure 4.

Days to detection of ICD problems in patients assigned to remote home monitoring. Overall, 22/43 (51%) were detected within 24 h (compiled with permission from Varma et al.22).

For small centres without dedicated on-site personnel, a model based on a collaborative network between neighbouring structures (hub and spoke model) has been suggested, in which the hub centre first receives and processes all the transmissions. In case of meaningful alerts, the data are sent to the spoke centre for patient recall and clinical management.106

For hospitals without the necessary staff, third-party resources may help with RM tasks.107,108 This strategy may have clinical, financial and workflow benefits, but it may induce the patient’s perception of losing the human relationship with the clinical staff with decreased compliance and satisfaction.

In-person clinical evaluation is recommended generally at least once yearly but may be extended to once every 2 years or more for patients without or with mild structural heart disease.109–111 An alert-based only follow-up strategy could be considered in the future.20

Resource consumption

Pursuing the strategy to offer RM to all patients leads to an exponential increase of transmissions and clinic workload. Unscheduled transmissions may increase the work burden by 30–40%.40 Transmission review is usually fast, ranging from 2 to 5 min according to manufacturer website and data content, but complete patient remote management includes technology and connectivity troubleshooting, diagnosis, patient communication, clinical action, electronic charting, scheduling, and billing. Associated time consumption is usually low for pacemakers but increases exponentially for loop recorders.112,113 According to available data, an estimated 30–40 h a week are required to manage 1000 patients on RM.

In 2016, Maines et al.114 started the routine implementation of the RM service for all patients by applying the workflow model suggested by the AIAC.105 After 2 years, 93% of patients were remotely monitored. The transmission rates were as follows: 5.3/patient-year for pacemakers, 6.0/patient-year for defibrillators, and 14.1/patient-year for loop recorders. Only 21% of transmissions were submitted by the nurse to the physician for further clinical evaluation, and 3% of transmissions necessitated an unplanned in-hospital visit for further assessment. Clinical events of any type were detected in 39% of transmissions. Overall, the nurse total workload was 1.95 full-time equivalent, which resulted in 1038 patients/nurse. The total workload for physicians was 0.29 full-time equivalent.

The impact on resource consumption of scheduled vs. alert transmissions was further evaluated.115 Scheduled transmissions generated 67% of remote data reviews for pacemakers and ICDs, but their ability to detect clinically relevant events was extremely low. On the contrary, 24% of the alert transmissions required clinical discussion, and 3% necessitated in-hospital visits. The proportion of alerts judged clinically meaningful was 7%.

Patient satisfaction

Patient acceptance of RM is variable. In some studies, no difference was observed in quality of life and patient satisfaction when comparing RM with a conventional follow-up strategy.42 Others have shown a high patient satisfaction rate, ease of use, and good compliance with the use of RM systems.116,117 Patients also reported a positive impact on perceived safety and general health and rarely complained of the lack of interaction with healthcare professionals.114 The organizational model may be critical to improve patient satisfaction. Remote monitoring has been demonstrated to be well accepted even for elderly people and for patient with a low level of scholarity.118,119 Automaticity and reliability of remote technology are important. In the TRUST trial,21 transmission failure occurred in less than 1%. No patient assigned to Home Monitoring (HM) crossed over during the study and 98% elected to retain this follow-up mode on trial conclusion, indicating patient acceptance and confidence in follow-up with this technology. In striking contrast, with conventional management, patient attrition was significantly higher. Introduction of smartphone-based RM using patient applications has been demonstrated to further improve patient compliance and connectivity compared with traditional bedside monitor RM.120

Hurdles to remote management adoption

In addition to the challenges with workflow and consumption of resources resulting from managing alerts121 (covered in the previous section), there may be concerns for data protection and for legal exposure. Finally, there may also be no financial incentive to adopt remote device management due to lack of reimbursement.

The need for guidance on legal aspects of remote device management has been recognized for years.5,122,123 In 2020, EHRA and the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Regulatory Affairs Committee published a joint task force report on legal requirements for RM, in light of the European Union General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), which has been implemented since 2018.124 The main objective of the GDPR is to ensure ‘the protection of natural persons with regard to the processing of personal data and on the free movement of such data’. The processing of personal data (which includes health data) should be undertaken only with specific consent, and individuals or organizations collecting and retaining data are accountable.

The ‘data controller’ is defined as the person or body, which determines the purposes and means of processing personal data. As manufacturers determine the ‘means’ for remote device management with the technology used to collect data, they are considered to be data controllers and are responsible for providing access to the personal data collected and should offer the possibility to delete them. The healthcare facility or hospital is considered along with the manufacturer as a joint data controller, since they determine the clinical indications for collecting data remotely, and which data are collected and analysed. Sometimes this may be done together with the physician if the healthcare professional is self-employed. Otherwise, a hospital takes legal responsibility as controller for staff whom it employs. The healthcare facility should make a contractual agreement with the manufacturer regarding the roles and responsibilities of each party, taking into account the specific rules that apply when transferring personal data outside the European Union (where the servers of some of the device manufacturers are located). Patients are granted the right to obtain information from the data controller about the nature and use of the data stored, and they have the right of access to their own data. With certain exceptions, they have the right to be forgotten and to have their data erased. The ‘data processor’ handles personal data on behalf of the controller and in accordance with any limitations established by the controller. Third-party providers (‘middleware’ companies) are data processors. A legal contract should be made also between the data controller and a third-party provider.

Cybersecurity is another concern and manufacturers should ensure adequate encryption of transmitted data.124,125

Physicians may be concerned about legal liability for failure for timely response to remote alerts to prevent adverse events.13,126 It is therefore important that signed patient informed consent forms outline the services provided by the healthcare facility (e.g. evaluation of alerts during working hours only), as well as the limitations of the service. An aspect that also needs to be considered is the liability incurred by not providing RM in patients in whom this is indicated according to guidelines (e.g. in patients with devices under recall111).

Reimbursement is a major factor that affects uptake of remote device management worldwide, which remains heterogeneous.127–133 Evidence regarding the economic benefit of RM is growing, which should hopefully convince more payers to cover this service.90,134–138 Interestingly, the COVID-19 pandemic sparked some payers to introduce reimbursement for remote device management.139

Transition to digital health

The growing availability of smartphones and application to health queries has resulted in several smartphone applications focused on CIED patient engagement and interpretation of the data.52 Some can already replace conventional RM and CIED interrogations. For this purpose, one study showed that 250 patients achieved a higher rate of completing transmissions vs. historical control subjects who used traditional or wireless bedside monitors.140 Younger patients may be more receptive.141 The systems are generally safe. Risk of electromagnetic interference between modern smartphones and contemporary CIEDs is low142–144; however, patients should be instructed to avoid direct contact between their mobile phone and their CIED.

Incoming data from RM databases may be processed by AI. For example, algorithms to optimize scanning of all transmissions to identify CIED patients with AF enhanced AF detection sensitivity by 10% and improved oral anticoagulation optimal treatment by 6%.145 An AI tool to filter AF alerts resulted in an 84% reduction in notification workload, while preserving patient safety.146 Interestingly, neural network modelling of remotely acquired device-based data helped to identify patients at risk of malignant ventricular arrhythmias and appropriate device therapies within 30 days.37

Hence, the application of patient smartphone applications to encourage patient compliance with RM by providing information on communicator setup, troubleshooting, and connection status of the communicator120,147 can be an efficient way to ensure continuity of patient monitoring while limiting workload at the centres. Barriers occur at the time of activating RM and keeping patients monitored, both of which are dependent on patient factors. Despite the general increase in digital literacy, there are still patient sub-groups with limited confidence in digital technology, requiring dedicated education in the use of smartphone apps and other digital devices.37 A structured patient pathway may facilitate engagement of patients with digital health technology.52 Personalized and fully automated RM device setup programmes are designed to educate people about technology, while simultaneously helping reduce the ‘digital divide’ and relieving the load on physician and clinic staff as well.

Conclusion

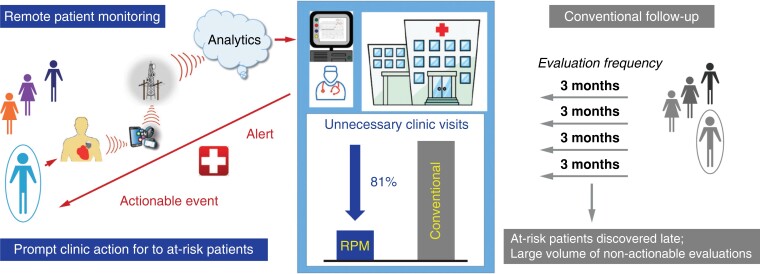

Remote monitoring of CIED function has become the standard of care and professional society recommendations have been updated frequently reflecting the vigorous development in technology and applications and the need for patient education.4–6,8 The most recent moves to surveillance with continuous RM and clinic evaluation only when indicated by personalized RM notifications, representing a sea change in the standard of care from a decade ago, i.e. structured follow-up based on regular intermittent appointments. Clinically stable patients may be seen in office only every 24 months and perhaps longer (Figure 5). This model of asynchronous care in turn has vast implications for workflow, reimbursement, and data management reflecting entry into the digital age.20,146,148

Figure 5.

Conventional follow-up based on intermittent calendar-based care is likely to be replaced by digitally driven alert based care (left) to identify subjects needing care promptly and reducing the non-actionable work performed by clinics, thus easing workflow (compiled with permission from Varma et al.20).

Contributor Information

Niraj Varma, Cardiac Pacing and Electrophysiology, Cleveland Clinic, 9500 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44118, USA.

Frieder Braunschweig, Karolinska University Hospital Stockholm, 17176 Stockholm, Sweden.

Haran Burri, University Hospital of Geneva, 1205 Geneva, Switzerland.

Gerhard Hindricks, Charite Hospital, 10117 Berlin, Germany.

Dominik Linz, Maastricht University Medical Center, 6211 LK Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Yoav Michowitz, Department of Cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, Shaare Zedek Medical Center, Hebrew University, Jerusalem 9112001, Israel.

Renato Pietro Ricci, Cardio Arrhythmology Center, 00186 Roma, Italy.

Jens Cosedis Nielsen, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus University, 8200 Aarhus, Denmark.

Funding

None declared.

Data availability

No primary data were analyzed for this manuscript which reviewed existing literature.

References

- 1. Niraj V, Pedro B. Automatic home monitoring of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices—the setting of a new standard. Europace 2013;15:i1–i2. http://europace.oxfordjournals.org/content/15/suppl_1.toc.23737221 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Santini M. Remote monitoring and the twin epidemics of AF and CHF. Europace 2013;15:i47–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Varma N, Brugada P. Automatic remote monitoring: milestones reached, paths to pave. Europace 2013;15:i69–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Wilkoff BL, Auricchio A, Brugada J, Cowie M, Ellenbogen KA, Gillis AMet al. HRS/EHRA expert consensus on the monitoring of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs): description of techniques, indications, personnel, frequency and ethical considerations: developed in partnership with the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) and the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), the American Heart Association (AHA), the European Society of Cardiology (ESC), the Heart Failure Association of ESC (HFA), and the Heart Failure Society of America (HFSA). Endorsed by the Heart Rhythm Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association (a registered branch of the ESC), the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association. Europace 2008;10:707–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dubner S, Auricchio A, Steinberg JS, Vardas P, Stone P, Brugada Jet al. ISHNE/EHRA expert consensus on remote monitoring of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices (CIEDs). Europace 2012;14:278–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ferrick AM, Raj SR, Deneke T, Kojodjojo P, Lopez-Cabanillas N, Abe Het al. HRS/EHRA/APHRS/LAHRS expert consensus statement on practical management of the remote device clinic. Europace 2023;2023:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Furman S, Parker B, Escher DJ. Transtelephone pacemaker clinic. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1971;61:827–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Slotwiner D, Varma N, Akar JG, Annas G, Beardsall M, Fogel RIet al. HRS expert consensus statement on remote interrogation and monitoring for cardiovascular implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm 2015;12:e69–e100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson MH, Paul VE, Jones S, Ward DE, Camm AJ. Transtelephonic interrogation of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 1992;15:1144–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Schoenfeld MH, Compton SJ, Mead RH, Weiss DN, Sherfesee L, Englund Jet al. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: a prospective analysis. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2004;27:757–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sutton R. Remote monitoring as a key innovation in the management of cardiac patients including those with implantable electronic devices. Europace 2013;15:i3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varma N. Automatic remote home monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillator lead and generator function: a system that tests itself everyday. Europace 2013;15:i26–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Burri H. Remote follow-up and continuous remote monitoring, distinguished. Europace 2013;15:i14–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Varma N, Love CJ, Schweikert R, Moll P, Michalski J, Epstein AE. Automatic remote monitoring utilizing daily transmissions: transmission reliability and implantable cardioverter defibrillator battery longevity in the TRUST trial. Europace 2018;20:622–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Senges-Becker JC, Klostermann M, Becker R, Bauer A, Siegler KE, Katus HAet al. What is the “optimal” follow-up schedule for ICD patients? Europace 2005;7:319–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Cronin EM, Ching EA, Varma N, Martin DO, Wilkoff BL, Lindsay BD. Remote monitoring of cardiovascular devices: a time and activity analysis. Heart Rhythm 2012;9:1947–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Neuzil P, Taborsky M, Holy F, Wallbrueck K. Early automatic remote detection of combined lead insulation defect and ICD damage. Europace 2008;10:556–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Spencker S, Coban N, Koch L, Schirdewan A, Muller D. Potential role of home monitoring to reduce inappropriate shocks in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients due to lead failure. Europace 2009;11:483–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Varma N, Epstein AE, Irimpen A, Schweikert R, Love C. Efficacy and safety of automatic remote monitoring for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator follow-up: the Lumos-T Safely RedUceS RouTine Office Device Follow-Up (TRUST) trial. Circulation 2010;122:325–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Varma N, Love CJ, Michalski J, Epstein AE. Alert-based ICD follow-up: a model of digitally driven remote patient monitoring. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:976–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Varma N, Michalski J, Stambler B, Pavri BB. Superiority of automatic remote monitoring compared with in-person evaluation for scheduled ICD follow-up in the TRUST trial—testing execution of the recommendations. Eur Heart J 2014;35:1345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Varma N, Pavri BB, Stambler B, Michalski J. Same-day discovery of implantable cardioverter defibrillator dysfunction in the TRUST remote monitoring trial: influence of contrasting messaging systems. Europace 2013;15:697–703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Varma N, Michalski J, Epstein AE, Schweikert R. Automatic remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead and generator performance: the Lumos-T Safely RedUceS RouTine Office Device Follow-Up (TRUST) trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010;3:428–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Varma N. Remote monitoring for advisories: automatic early detection of silent lead failure. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2009;32:525–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Medtronic . Physician Advisory Letter: Urgent Medical Device Information. Sprint Fidelis® Lead Patient Management Recommendations.https://www.medtronic.com/us-en/healthcare-professionals/products/product-performance/sprint-fidelisphysician-10-15-2007.html. 2007.

- 26. Guedon-Moreau L, Lacroix D, Sadoul N, Clementy J, Kouakam C, Hermida JSet al. A randomized study of remote follow-up of implantable cardioverter defibrillators: safety and efficacy report of the ECOST trial. Eur Heart J 2013;34:605–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Parthiban N, Esterman A, Mahajan R, Twomey DJ, Pathak RK, Lau DHet al. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: a systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol 2015;65:2591–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Chiu CSL, Timmermans I, Versteeg H, Zitron E, Mabo P, Pedersen SSet al. Effect of remote monitoring on clinical outcomes in European heart failure patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: secondary results of the REMOTE-CIED randomized trial. Europace 2022;24:256–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kolk MZH, Narayan SM, Clopton P, Wilde AAM, Knops RE, Tjong FVY. Reduction in long-term mortality using remote device monitoring in a large real-world population of patients with implantable defibrillators. Europace 2023;25:969–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Perrin T, Boveda S, Defaye P, Rosier A, Sadoul N, Bordachar Pet al. Role of medical reaction in management of inappropriate ventricular arrhythmia diagnosis: the inappropriate Therapy and HOme monitoRiNg (THORN) registry. Europace 2019;21:607–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Varma N, Jones P, Wold N, Cronin E, Stein K. How well do results from randomized clinical trials and/or recommendations for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator programming diffuse into clinical practice? (Translation assessed in a national cohort of patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ALTITUDE)). J Am Heart Assoc 2019;8:e007392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Varma N, Johnson MA. Prevalence of cancelled shock therapy and relationship to shock delivery in recipients of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators assessed by remote monitoring. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2009;32:S42–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Boule S, Ninni S, Finat L, Botcherby EJ, Kouakam C, Klug Det al. Potential role of antitachycardia pacing alerts for the reduction of emergency presentations following shocks in patients with implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: implications for the implementation of remote monitoring. Europace 2016;18:1809–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ploux S, Varma N, Strik M, Lazarus A, Bordachar P. Optimizing implantable cardioverter-defibrillator remote monitoring: a practical guide. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2017;3:315–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Souissi Z, Guedon-Moreau L, Boule S, Kouakam C, Finat L, Marquie Cet al. Impact of remote monitoring on reducing the burden of inappropriate shocks related to implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead fractures: insights from a French single-centre registry. Europace 2016;18:820–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Shakibfar S, Krause O, Lund-Andersen C, Aranda A, Moll J, Andersen TOet al. Predicting electrical storms by remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillator patients using machine learning. Europace 2019;21:268–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ginder C, Li J, Halperin JL, Akar JG, Martin DT, Chattopadhyay Iet al. Predicting malignant ventricular arrhythmias using real-time remote monitoring. J Am Coll Cardiol 2023;81:949–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Swerdlow CD, Gunderson BD, Ousdigian KT, Abeyratne A, Sachanandani H, Ellenbogen KA. Downloadable software algorithm reduces inappropriate shocks caused by implantable cardioverter-defibrillator lead fractures: a prospective study. Circulation 2010;122:1449–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Varma N, Michalski J. Alert notifications during automatic wireless remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: load, characteristics, and clinical utility. Heart Rhythm 2023;20:473–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. O'Shea CJ, Middeldorp ME, Hendriks JM, Brooks AG, Lau DH, Emami Met al. Remote monitoring alert burden: an analysis of transmission in >26,000 patients. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:226–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hindricks G, Elsner C, Piorkowski C, Taborsky M, Geller JC, Schumacher Bet al. Quarterly vs. yearly clinical follow-up of remotely monitored recipients of prophylactic implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: results of the REFORM trial. Eur Heart J 2014;35:98–105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Mabo P, Victor F, Bazin P, Ahres S, Babuty D, Da Costa Aet al. A randomized trial of long-term remote monitoring of pacemaker recipients (the COMPAS trial). Eur Heart J 2012;33:1105–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Crossley GH, Boyle A, Vitense H, Chang Y, Mead RH. The CONNECT (Clinical Evaluation of Remote Notification to Reduce Time to Clinical Decision) trial: the value of wireless remote monitoring with automatic clinician alerts. J Am Coll Cardiol 2011;57:1181–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Santini M. Home monitoring remote control of pacemaker and implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients in clinical practice: impact on medical management and health-care resource utilization. Europace 2008;10:164–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Santini M. Remote control of implanted devices through home monitoring technology improves detection and clinical management of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2009;11:54–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Ricci RP, Morichelli L, D'Onofrio A, Calo L, Vaccari D, Zanotto Get al. Effectiveness of remote monitoring of CIEDs in detection and treatment of clinical and device-related cardiovascular events in daily practice: the HomeGuide registry. Europace 2013;15:970–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Schnabel RB, Marinelli EA, Arbelo E, Boriani G, Boveda S, Buckley CMet al. Early diagnosis and better rhythm management to improve outcomes in patients with atrial fibrillation: the 8th AFNET/EHRA consensus conference. Europace 2023;25:6–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Ziegler PD, Glotzer TV, Daoud EG, Wyse DG, Singer DE, Ezekowitz MDet al. Incidence of newly detected atrial arrhythmias via implantable devices in patients with a history of thromboembolic events. Stroke 2010;41:256–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Healey JS, Connolly SJ, Gold MR, Israel CW, Van Gelder IC, Capucci Aet al. Subclinical atrial fibrillation and the risk of stroke. N Engl J Med 2012;366:120–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Sanna T, Diener HC, Passman RS, Di Lazzaro V, Bernstein RA, Morillo CAet al. Cryptogenic stroke and underlying atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med 2014;370:2478–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Linz D, Hermans A, Tieleman RG. Early atrial fibrillation detection and the transition to comprehensive management. Europace 2021;23:ii46–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Svennberg E, Tjong F, Goette A, Akoum N, Di Biase L, Bordachar Pet al. How to use digital devices to detect and manage arrhythmias: an EHRA practical guide. Europace 2022;24:979–1005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Pluymaekers N, Hermans ANL, van der Velden RMJ, Gawalko M, den Uijl DW, Buskes Set al. Implementation of an on-demand app-based heart rate and rhythm monitoring infrastructure for the management of atrial fibrillation through teleconsultation: TeleCheck-AF. Europace 2021;23:345–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Verhaert DVM, Betz K, Gawałko M, Hermans ANL, Pluymaekers N, van der Velden RMJet al. A VIRTUAL sleep apnoea management pathway for the work-up of atrial fibrillation patients in a digital remote infrastructure: VIRTUAL-SAFARI. Europace 2022;24:565–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Censi F, Calcagnini G, Mattei E, Calò L, Curnis A, D'Onofrio Aet al. Seasonal trends in atrial fibrillation episodes and physical activity collected daily with a remote monitoring system for cardiac implantable electronic devices. Int J Cardiol 2017;234:48–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. De With RR, Erküner Ö, Rienstra M, Nguyen BO, Körver FWJ, Linz Det al. Temporal patterns and short-term progression of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: data from RACE V. Europace 2020;22:1162–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. van de Lande ME, Rama RS, Koldenhof T, Arita VA, Nguyen BO, van Deutekom Cet al. Time of onset of atrial fibrillation and atrial fibrillation progression data from the RACE V study. Europace 2023;25:euad058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Boriani G, Lip GYH, Ricci RP, Proclemer A, Landolina M, Lunati Met al. The increased risk of stroke/transient ischemic attack in women with a cardiac implantable electronic device is not associated with a higher atrial fibrillation burden. Europace 2017;19:1767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Boriani G, Botto GL, Pieragnoli P, Ricci R, Biffi M, Marini Met al. Temporal patterns of premature atrial complexes predict atrial fibrillation occurrence in bradycardia patients continuously monitored through pacemaker diagnostics. Intern Emerg Med 2020;15:599–606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rovaris G, Solimene F, D'Onofrio A, Zanotto G, Ricci RP, Mazzella Tet al. Does the CHA2DS2-VASc score reliably predict atrial arrhythmias? Analysis of a nationwide database of remote monitoring data transmitted daily from cardiac implantable electronic devices. Heart Rhythm 2018;15:971–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Vergara P, Solimene F, D'Onofrio A, Pisanò EC, Zanotto G, Pignalberi Cet al. Are atrial high-rate episodes associated with increased risk of ventricular arrhythmias and mortality? JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2019;5:1197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Ricci RP, Pignalberi C, Landolina M, Santini M, Lunati M, Boriani Get al. Ventricular rate monitoring as a tool to predict and prevent atrial fibrillation-related inappropriate shocks in heart failure patients treated with cardiac resynchronisation therapy defibrillators. Heart 2014;100:848–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Gargaro A, Laudadio MT, Santini M. Home monitoring in patients with implantable cardiac devices: is there a potential reduction of stroke risk? Results from a computer model tested through Monte Carlo simulations. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2009;20:1244–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Ricci RP, Vaccari D, Morichelli L, Zanotto G, Calò L, D'Onofrio Aet al. Stroke incidence in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices remotely controlled with automatic alerts of atrial fibrillation. A sub-analysis of the HomeGuide study. Int J Cardiol 2016;219:251–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Martin DT, Bersohn MM, Waldo AL, Wathen MS, Choucair WK, Lip GYet al. Randomized trial of atrial arrhythmia monitoring to guide anticoagulation in patients with implanted defibrillator and cardiac resynchronization devices. Eur Heart J 2015;36:1660–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Jang JP, Lin HT, Chen YJ, Hsieh MH, Huang YC. Role of remote monitoring in detection of atrial arrhythmia, stroke reduction, and use of anticoagulation therapy—a systematic review and meta-analysis. Circ J 2020;84:1922–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Kirchhof P, Blank BF, Calvert M, Camm AJ, Chlouverakis G, Diener HCet al. Probing oral anticoagulation in patients with atrial high rate episodes: rationale and design of the Non-vitamin K antagonist Oral anticoagulants in patients with Atrial High rate episodes (NOAH-AFNET 6) trial. Am Heart J 2017;190:12–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Lopes RD, Alings M, Connolly SJ, Beresh H, Granger CB, Mazuecos JBet al. Rationale and design of the Apixaban for the Reduction of Thrombo-Embolism in Patients with Device-Detected Sub-Clinical Atrial Fibrillation (ARTESiA) trial. Am Heart J 2017;189:137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Wang TJ, Larson MG, Levy D, Vasan RS, Leip EP, Wolf PAet al. Temporal relations of atrial fibrillation and congestive heart failure and their joint influence on mortality: the Framingham Heart Study. Circulation 2003;107:2920–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Brachmann J, Sohns C, Andresen D, Siebels J, Sehner S, Boersma Let al. Atrial fibrillation burden and clinical outcomes in heart failure: the CASTLE-AF trial. JACC Clin Electrophysiol 2021;7:594–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Theuns DA, Res JC, Jordaens LJ. Home monitoring in ICD therapy: future perspectives. Europace 2003;5:139–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Adamson PB, Magalski A, Braunschweig F, Bohm M, Reynolds D, Steinhaus Det al. Ongoing right ventricular hemodynamics in heart failure: clinical value of measurements derived from an implantable monitoring system. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;41:565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Arya A, Block M, Kautzner J, Lewalter T, Mortel H, Sack Set al. Influence of home monitoring on the clinical status of heart failure patients: design and rationale of the IN-TIME study. Eur J Heart Fail 2008;10:1143–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Cowie MR, Sarkar S, Koehler J, Whellan DJ, Crossley GH, Tang WHet al. Development and validation of an integrated diagnostic algorithm derived from parameters monitored in implantable devices for identifying patients at risk for heart failure hospitalization in an ambulatory setting. Eur Heart J 2013;34:2472–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Burri H, da Costa A, Quesada A, Ricci RP, Favale S, Clementy Net al. Risk stratification of cardiovascular and heart failure hospitalizations using integrated device diagnostics in patients with a cardiac resynchronization therapy defibrillator. Europace 2018;20:e69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Desai AS, Stevenson LW. Connecting the circle from home to heart-failure disease management. N Engl J Med 2010;363:2364–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Ritzema J, Melton IC, Richards AM, Crozier IG, Frampton C, Doughty RNet al. Direct left atrial pressure monitoring in ambulatory heart failure patients: initial experience with a new permanent implantable device. Circulation 2007;116:2952–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Becher J, Kaufmann SG, Paule S, Fahn B, Skerl O, Bauer WRet al. Device-based impedance measurement is a useful and accurate tool for direct assessment of intrathoracic fluid accumulation in heart failure. Europace 2010;12:731–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Yu CM, Wang L, Chau E, Chan RH, Kong SL, Tang MOet al. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring in patients with heart failure: correlation with fluid status and feasibility of early warning preceding hospitalization. Circulation 2005;112:841–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Vanderheyden M, Houben R, Verstreken S, Ståhlberg M, Reiters P, Kessels Ret al. Continuous monitoring of intrathoracic impedance and right ventricular pressures in patients with heart failure. Circ Heart Fail 2010;3:370–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Adamson PB, Smith AL, Abraham WT, Kleckner KJ, Stadler RW, Shih Aet al. Continuous autonomic assessment in patients with symptomatic heart failure: prognostic value of heart rate variability measured by an implanted cardiac resynchronization device. Circulation 2004;110:2389–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Kadhiresan VA, Pastore J, Auricchio A, Sack S, Doelger A, Girouard Set al. A novel method—the activity log index—for monitoring physical activity of patients with heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2002;89:1435–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Auricchio A, Gold MR, Brugada J, Nölker G, Arunasalam S, Leclercq Cet al. Long-term effectiveness of the combined minute ventilation and patient activity sensors as predictor of heart failure events in patients treated with cardiac resynchronization therapy: results of the Clinical Evaluation of the Physiological Diagnosis Function in the PARADYM CRT device trial (CLEPSYDRA) study. Eur J Heart Fail 2014;16:663–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Sacchi S, Pieragnoli P, Ricciardi G, Grifoni G, Padeletti L. Impact of haemodynamic SonR sensor on monitoring of left ventricular function in patients undergoing cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace 2017;19:1695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Ypenburg C, Bax JJ, van der Wall EE, Schalij MJ, van Erven L. Intrathoracic impedance monitoring to predict decompensated heart failure. Am J Cardiol 2007;99:554–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Boehmer JP, Hariharan R, Devecchi FG, Smith AL, Molon G, Capucci Aet al. A multisensor algorithm predicts heart failure events in patients with implanted devices: results from the MultiSENSE study. JACC Heart Fail 2017;5:216–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. D'Onofrio A, Solimene F, Calò L, Calvi V, Viscusi M, Melissano Det al. Combining home monitoring temporal trends from implanted defibrillators and baseline patient risk profile to predict heart failure hospitalizations: results from the SELENE HF study. Europace 2022;24:234–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. De Simone A, Leoni L, Luzi M, Amellone C, Stabile G, La Rocca Vet al. Remote monitoring improves outcome after ICD implantation: the clinical efficacy in the management of heart failure (EFFECT) study. Europace 2015;17:1267–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Klersy C, Boriani G, De Silvestri A, Mairesse GH, Braunschweig F, Scotti Vet al. Effect of telemonitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices on healthcare utilization: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials in patients with heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail 2016;18:195–204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Capucci A, De Simone A, Luzi M, Calvi V, Stabile G, D'Onofrio Aet al. Economic impact of remote monitoring after implantable defibrillators implantation in heart failure patients: an analysis from the EFFECT study. Europace 2017;19:1493–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Boriani G, Da Costa A, Quesada A, Ricci RP, Favale S, Boscolo Get al. Effects of remote monitoring on clinical outcomes and use of healthcare resources in heart failure patients with biventricular defibrillators: results of the MORE-CARE multicentre randomized controlled trial. Eur J Heart Fail 2017;19:416–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Böhm M, Drexler H, Oswald H, Rybak K, Bosch R, Butter Cet al. Fluid status telemedicine alerts for heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. Eur Heart J 2016;37:3154–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Morgan JM, Kitt S, Gill J, McComb JM, Ng GA, Raftery Jet al. Remote management of heart failure using implantable electronic devices. Eur Heart J 2017;38:2352–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Versteeg H, Timmermans I, Widdershoven J, Kimman GJ, Prevot S, Rauwolf Tet al. Effect of remote monitoring on patient-reported outcomes in European heart failure patients with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator: primary results of the REMOTE-CIED randomized trial. Europace 2019;21:1360–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Hindricks G, Taborsky M, Glikson M, Heinrich U, Schumacher B, Katz Aet al. Implant-based multiparameter telemonitoring of patients with heart failure (IN-TIME): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2014;384:583–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Hindricks G, Varma N, Kacet S, Lewalter T, Søgaard P, Guédon-Moreau Let al. Daily remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: insights from the pooled patient-level data from three randomized controlled trials (IN-TIME, ECOST, TRUST). Eur Heart J 2017;38:1749–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Braunschweig F, Anker SD, Proff J, Varma N. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators and resynchronization devices to improve patient outcomes: dead end or way ahead? Europace 2019;21:846–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Varma N, Bourge RC, Stevenson LW, Costanzo MR, Shavelle D, Adamson PBet al. Remote hemodynamic-guided therapy of patients with recurrent heart failure following cardiac resynchronization therapy. J Am Heart Assoc 2021;10:e017619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Lindenfeld J, Zile MR, Desai AS, Bhatt K, Ducharme A, Horstmanshof Det al. Haemodynamic-guided management of heart failure (GUIDE-HF): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2021;398:991–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zile MR, Desai AS, Costanzo MR, Ducharme A, Maisel A, Mehra MRet al. The GUIDE-HF trial of pulmonary artery pressure monitoring in heart failure: impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur Heart J 2022;43:2603–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Ståhlberg M, Kessels R, Linde C, Braunschweig F. Acute haemodynamic effects of increase in paced heart rate in heart failure patients recorded with an implantable haemodynamic monitor. Europace 2011;13:237–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Zanotto G, D'Onofrio A, Della Bella P, Solimene F, Pisanò EC, Iacopino Set al. Organizational model and reactions to alerts in remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices: a survey from the Home Monitoring Expert Alliance project. Clin Cardiol 2019;42:76–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Ricci RP, Morichelli L. Workflow, time and patient satisfaction from the perspectives of home monitoring. Europace 2013;15:i49–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ricci RP, Morichelli L, D'Onofrio A, Calò L, Vaccari D, Zanotto Get al. Manpower and outpatient clinic workload for remote monitoring of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: data from the HomeGuide registry. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2014;25:1216–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Zanotto G, Melissano D, Baccillieri S, Campana A, Caravati F, Maines Met al. Intrahospital organizational model of remote monitoring data sharing, for a global management of patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices: a document of the Italian Association of Arrhythmology and Cardiac Pacing. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2020;21:171–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Vogtmann T, Stiller S, Marek A, Kespohl S, Gomer M, Kuhlkamp Vet al. Workload and usefulness of daily, centralized home monitoring for patients treated with CIEDs: results of the MoniC (Model Project Monitor Centre) prospective multicentre study. Europace 2013;15:219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Giannola G, Torcivia R, Airò Farulla R, Cipolla T. Outsourcing the remote management of cardiac implantable electronic devices: medical care quality improvement project. JMIR Cardio 2019;3:e9815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Nicolle E, Lanctin D, Rosemas S, De Melis M. Clinic time required to manage remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices: impact of outsourcing initial data review and triage. Europace 2021;23:iii570. [Google Scholar]

- 109. Garcia-Fernandez FJ, Osca Asensi J, Romero R, Fernandez Lozano I, Larrazabal JM, Martinez Ferrer Jet al. Safety and efficiency of a common and simplified protocol for pacemaker and defibrillator surveillance based on remote monitoring only: a long-term randomized trial (RM-ALONE). Eur Heart J 2019;40:1837–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Watanabe E, Yamazaki F, Goto T, Asai T, Yamamoto T, Hirooka Ket al. Remote management of pacemaker patients with biennial in-clinic evaluation: continuous home monitoring in the Japanese at-home study: a randomized clinical trial. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2020;13:e007734. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Glikson M, Nielsen JC, Kronborg MB, Michowitz Y, Auricchio A, Barbash IMet al. 2021 ESC guidelines on cardiac pacing and cardiac resynchronization therapy. Europace 2022;24:71–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Seiler A, Biundo E, Di Bacco M, Rosemas S, Nicolle E, Lanctin Det al. Clinic time required for remote and in-person management of patients with cardiac devices: time and motion workflow evaluation. JMIR Cardio 2021;5:e27720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Heidbuchel H, Hindricks G, Broadhurst P, Van Erven L, Fernandez-Lozano I, Rivero-Ayerza Met al. EuroEco (European Health Economic Trial on home monitoring in ICD patients): a provider perspective in five European countries on costs and net financial impact of follow-up with or without remote monitoring. Eur Heart J 2015;36:158–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Maines M, Tomasi G, Moggio P, Peruzza F, Catanzariti D, Angheben Cet al. Implementation of remote follow-up of cardiac implantable electronic devices in clinical practice: organizational implications and resource consumption. J Cardiovasc Med (Hagerstown) 2020;21:648–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Maines M, Tomasi G, Moggio P, Poian L, Peruzza F, Catanzariti Det al. Scheduled versus alert transmissions for remote follow-up of cardiac implantable electronic devices: clinical relevance and resource consumption. Int J Cardiol 2021;334:49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Ricci RP, Morichelli L, Quarta L, Sassi A, Porfili A, Laudadio MTet al. Long-term patient acceptance of and satisfaction with implanted device remote monitoring. Europace 2010;12:674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Petersen HH, Larsen MC, Nielsen OW, Kensing F, Svendsen JH. Patient satisfaction and suggestions for improvement of remote ICD monitoring. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2012;34:317–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Morichelli L, Porfili A, Quarta L, Sassi A, Ricci RP. Implantable cardioverter defibrillator remote monitoring is well accepted and easy to use during long-term follow-up. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2014;41:203–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Morichelli L, Ricci R, Sassi A, Quarta L, Porfili A, Cadeddu N. ICD Remote monitoring is well accepted and easy to use even for elderly. Eur Heart J 2011;32:32.20709722 [Google Scholar]

- 120. Manyam H, Burri H, Casado-Arroyo R, Varma N, Lennerz C, Klug Det al. Smartphone-based cardiac implantable electronic device remote monitoring: improved compliance and connectivity. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2023;4:43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Boriani G, Auricchio A, Klersy C, Kirchhof P, Brugada J, Morgan Jet al. Healthcare personnel resource burden related to in-clinic follow-up of cardiovascular implantable electronic devices: a European Heart Rhythm Association and Eucomed joint survey. Europace 2011;13:1166–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Vinck I, De Laet C, Stroobandt S, Van Brabandt H. Legal and organizational aspects of remote cardiac monitoring: the example of implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Europace 2012;14:1230–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Burri H, Senouf D. Remote monitoring and follow-up of pacemakers and implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Europace 2009;11:701–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Nielsen JC, Kautzner J, Casado-Arroyo R, Burri H, Callens S, Cowie MRet al. Remote monitoring of cardiac implanted electronic devices: legal requirements and ethical principles—ESC regulatory affairs committee/EHRA joint task force report. Europace 2020;22:1742–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Slotwiner DJ, Deering TF, Fu K, Russo AM, Walsh MN, Van Hare GF. Cybersecurity vulnerabilities of cardiac implantable electronic devices: communication strategies for clinicians-proceedings of the Heart Rhythm Society's leadership summit. Heart Rhythm 2018;15:e61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Hernández-Madrid A, Lewalter T, Proclemer A, Pison L, Lip GY, Blomstrom-Lundqvist C. Remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electronic devices in Europe: results of the European Heart Rhythm Association survey. Europace 2014;16:129–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Boriani G, Burri H, Mantovani LG, Maniadakis N, Leyva F, Kautzner Jet al. Device therapy and hospital reimbursement practices across European countries: a heterogeneous scenario. Europace 2011;13:ii59–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Slotwiner D, Wilkoff B. Cost efficiency and reimbursement of remote monitoring: a US perspective. Europace 2013;15:i54–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Boriani G, Burri H, Svennberg E, Imberti JF, Merino JL, Leclercq C. Current status of reimbursement practices for remote monitoring of cardiac implantable electrical devices across Europe. Europace 2022;24:1875–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Mairesse GH, Braunschweig F, Klersy K, Cowie MR, Leyva F. Implementation and reimbursement of remote monitoring for cardiac implantable electronic devices in Europe: a survey from the health economics committee of the European Heart Rhythm Association. Europace 2015;17:814–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Lau CP, Zhang S. Remote monitoring of cardiac implantable devices in the Asia-pacific. Europace 2013;15:i65–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Chronaki CE, Vardas P. Remote monitoring costs, benefits, and reimbursement: a European perspective. Europace 2013;15:i59–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Varma N, Kondo Y, Park SJ, Auricchio A, Gold MR, Boehmer Jet al. Utilization of remote monitoring among patients receiving cardiac resynchronization therapy and comparison between Asia and the Americas. Heart Rhythm O2 2022;3:868–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Burri H, Heidbuchel H, Jung W, Brugada P. Remote monitoring: a cost or an investment? Europace 2011;13:ii44–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Burri H, Sticherling C, Wright D, Makino K, Smala A, Tilden D. Cost-consequence analysis of daily continuous remote monitoring of implantable cardiac defibrillator and resynchronization devices in the UK. Europace 2013;15:1601–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Guédon-Moreau L, Lacroix D, Sadoul N, Clémenty J, Kouakam C, Hermida JSet al. Costs of remote monitoring vs. ambulatory follow-ups of implanted cardioverter defibrillators in the randomized ECOST study. Europace 2014;16:1181–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Sequeira S, Jarvis CI, Benchouche A, Seymour J, Tadmouri A. Cost-effectiveness of remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter-defibrillators in France: a meta-analysis and an integrated economic model derived from randomized controlled trials. Europace 2020;22:1071–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Raatikainen MJ, Uusimaa P, van Ginneken MM, Janssen JP, Linnaluoto M. Remote monitoring of implantable cardioverter defibrillator patients: a safe, time-saving, and cost-effective means for follow-up. Europace 2008;10:1145–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Simovic S, Providencia R, Barra S, Kircanski B, Guerra JM, Conte Get al. The use of remote monitoring of cardiac implantable devices during the COVID-19 pandemic: an EHRA physician survey. Europace 2022;24:473–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Tarakji KG, Zaidi AM, Zweibel SL, Varma N, Sears SF, Allred Jet al. Performance of first pacemaker to use smart device app for remote monitoring. Heart Rhythm O2 2021;2:463–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Hillmann HAK, Hansen C, Przibille O, Duncker D. The patient perspective on remote monitoring of implantable cardiac devices. Front Cardiovasc Med 2023;10:1123848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 142. Boriani G, Maisano A, Bonini N, Albini A, Imberti JF, Venturelli Aet al. Digital literacy as a potential barrier to implementation of cardiology tele-visits after COVID-19 pandemic: the INFO-COVID survey. J Geriatr Cardiol 2021;18:739–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 143. Burri H, Mondouagne Engkolo LP, Dayal N, Etemadi A, Makhlouf AM, Stettler Cet al. Low risk of electromagnetic interference between smartphones and contemporary implantable cardioverter defibrillators. Europace 2016;18:726–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 144. Stühlinger M, Burri H, Vernooy K, Garcia R, Lenarczyk R, Sultan Aet al. EHRA Consensus on prevention and management of interference due to medical procedures in patients with cardiac implantable electronic devices. Europace 2022;24:1512–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 145. Zoppo F, Facchin D, Molon G, Zanotto G, Catanzariti D, Rossillo Aet al. Improving atrial fibrillation detection in patients with implantable cardiac devices by means of a remote monitoring and management application. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2014;37:1610–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 146. Rosier A, Mabo P, Temal L, Van Hille P, Dameron O, Deleger Let al. Personalized and automated remote monitoring of atrial fibrillation. Europace 2016;18:347–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 147. Sgreccia D, Mauro E, Vitolo M, Manicardi M, Valenti AC, Imberti JFet al. Implantable cardioverter defibrillators and devices for cardiac resynchronization therapy: what perspective for patients’ apps combined with remote monitoring? Expert Rev Med Devices 2022;19:155–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 148. Varma N, Cygankiewicz I, Turakhia M, Heidbuchel H, Hu Y, Chen LYet al. 2021 ISHNE/HRS/EHRA/APHRS collaborative statement on mHealth in arrhythmia management: digital medical tools for heart rhythm professionals: from the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology/Heart Rhythm Society/European Heart Rhythm Association/Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society. Eur Heart J Digit Health 2021;2:7–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No primary data were analyzed for this manuscript which reviewed existing literature.