ABSTRACT

Background:

Ivabradine is a specific heart rate (HR)-lowering agent which blocks the cardiac pacemaker If channels. It reduces the HR without causing a negative inotropic or lusitropic effect, thus preserving ventricular contractility. The authors hypothesized that its usefulness in lowering HR can be utilized in patients undergoing off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery.

Objective:

To study the effects of preoperative ivabradine on hemodynamics (during surgery) in patients undergoing elective OPCAB surgery.

Methods:

Fifty patients, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class I and II, were randomized into group I (control, n = 25) and group II (ivabradine group, n = 25). In group I, patients received the usual anti-anginal medications in the preoperative period, as per the institutional protocol. In group II, patients received ivabradine 5 mg twice daily for 3 days before surgery, in addition to the usual anti-anginal medications. Anesthesia was induced with fentanyl, thiopentone sodium, and pancuronium bromide as a muscle relaxant and maintained with fentanyl, midazolam, pancuronium bromide, and isoflurane. The hemodynamic parameters [HR and mean arterial pressure (MAP)] and pulmonary artery (PA) catheter-derived data were recorded at the baseline (before induction), 3 min after the induction of anesthesia at 1 min and 3 min after intubation and at 5 min and 30 min after protamine administration. Intraoperatively, hemodynamic data (HR and MAP) were recorded every 10 min, except during distal anastomosis of the coronary arteries when it was recorded every 5 min. Post-operatively, at 24 hours, the levels of troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) were measured. This trial’s CTRI registration number is CTRI/005858.

Results:

The HR in group II was lower when compared to group I (range 59.6–72.4 beats/min and 65.8–80.2 beats/min, respectively) throughout the study period. MAP was comparable [range (78.5–87.8 mm Hg) vs. (78.9-88.5 mm Hg) in group II vs. group I, respectively] throughout the study period. Intraoperatively, 5 patients received metoprolol in group I to control the HR, whereas none of the patients in group II required metoprolol. The incidence of preoperative bradycardia (HR <60 beats/min) was higher in group II (20%) vs. group I (8%). There was no difference in both the groups in terms of troponin T and BNP level after 24 hours, time to extubation, requirement of inotropes, incidence of arrhythmias, in-hospital morbidity, and 30-day mortality.

Conclusion:

Ivabradine can be safely used along with other anti-anginal agents during the preoperative period in patients undergoing OPCAB surgery. It helps to maintain a lower HR during surgery and reduces the need for beta-blockers in the intraoperative period, a desirable and beneficial effect in situations where the use of beta-blockers may be potentially harmful. Further studies are needed to evaluate the beneficial effects of perioperative Ivabradine in patients with moderate-to-severe left ventricular dysfunction.

Keywords: Heart rate, ivabradine, off-pump coronary artery bypass grafting

INTRODUCTION

Heart rate (HR) is an important determinant of coronary perfusion and myocardial oxygen demand. During off-pump coronary artery bypass (OPCAB) surgery, mild myocardial depression [lower HR and mean arterial pressure (MAP)] is desirable as it aids in a meticulous distal anastomosis of the coronary arteries. The optimal HR for patients undergoing OPCAB surgery is 70–80 beats/min.[1] Patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) are on anti-anginal medications such as nitrates (work primarily by coronary vasodilatation increasing the oxygen supply), beta-blockers (decrease HR, cardiac contractility, and secondarily reduce blood pressure, all of which contribute to a reduction in oxygen demand), and calcium channel blockers [(CCBs) (improve oxygen delivery, reduce oxygen demand, and slow the HR)].[2] Beta-blockers and CCBs have a negative inotropic effect on the heart which can be harmful to patients undergoing OPCAB surgery, especially those having moderate-to-severe left ventricular (LV) dysfunction and congestive heart failure (CHF). Thus, it is desirable to use a drug, which can reduce the HR without affecting the inotropy or lusitropy of the heart. Currently, the approved list (except in the USA) of anti-anginal agents also includes ivabradine which is a specific HR-lowering agent.[2]

Ivabradine has been used in patients with stable angina and left ventricular (LV) dysfunction to achieve an optimal HR,[3] but, unlike other HR-lowering agents such as β-blockers and CCBs, it has no direct effect on myocardial contractility, ventricular repolarization, or intra-cardiac conduction and does not reduce the LV ejection fraction in patients with impaired LV function.[4,5,6,7,8] It is devoid of some of the major adverse effects associated with beta-blockers (e.g., fatigue, erectile dysfunction, glycemic perturbations, etc.); hence, it is likely to be better tolerated by patients with CHF. Furthermore, many patients with bronchospastic lung disease, peripheral vascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and atrioventricular (AV) blocks who have contraindications to the use of beta-blockers can now receive ivabradine for additional therapeutic benefits.[9,10] Ivabradine is also protective when given before reperfusion, thus indicating that it attenuates reperfusion injury, which is a HR-independent effect and is probably mediated by post-conditioning.[11,12] Despite all these advantages there are very few published data from clinical trials which have evaluated the efficacy and benefits of ivabradine when used preoperatively in patients with CAD undergoing OPCAB surgery. Most of the published data is on its use in out-of-hospital patients,[13] post-operatively after undergoing cardiac surgery,[14,15,16] and in cardiac intensive-care units (ICUs).[9,13,17] The authors hypothesized that patients receiving anti-anginal agents may benefit from the use of ivabradine which would counter the increases in the HR that may occur due to sympathetic response during OPCAB surgery. The safety of ivabradine, when used in combination with angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor antagonists, diuretics, aspirin, digoxin, amiodarone, cholesterol-lowering agents, and beta-blockers has already been documented.[13,18]

MATERIALS AND METHODS

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval, Clinical Trials Registry—India, and informed consent, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status I and II patients, aged ≤70 years, undergoing elective primary OPCAB surgery with LV ejection fraction (EF) ≥40%, and HR >70 beats/min were included. Patients undergoing emergency or redo surgery, NYHA class III and IV, HR <60 beats/min, history of stroke or transient ischemic attack, rhythm abnormalities such as sick sinus syndrome/sino-atrial block/congenital long QT interval/complete atrioventricular (AV) block, implanted cardioverter defibrillator, or pacemaker and severe or uncontrolled hypertension were excluded from the study.

The patients with HR >70 beats/min were randomly allocated into two groups: Group I (control, n = 25) and group II (ivabradine, n = 25) by computer-generated randomization tables. It is a normal practice in our institution to administer beta-blockers, nitrates, calcium channel blockers, atorvastatin, and the angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor in patients awaiting OPCAB surgery (isosorbide mononitrate 20 mg twice daily, ramipril 2.5 mg twice daily, metoprolol 50 mg twice daily, and amiodarone 100 mg thrice daily). Patients in group I received the usual anti-anginal medications including beta-blockers in the preoperative period, whereas patients in group II received ivabradine 5 mg twice daily for 3 days before surgery in addition to the usual anti-anginal medications and beta-blockers. Both groups received premedication as per the institutional protocol with intramuscular promethazine 0.5 mg/kg and morphine 0.2 mg/kg 30 minutes before surgery. In the operating room, routine monitoring consisted of ECG, invasive blood pressure, end-tidal CO2, and peripheral oxygen saturation in both groups. Taking aseptic precautions, a 23 G Y-cannula, intra-arterial cannula, and pulmonary artery (PA) catheter were placed under local anesthesia. Thereafter, in both groups, anesthesia was induced with fentanyl (8–10 μg/kg), thiopentone sodium 1 mg/kg body weight, and muscle relaxant (pancuronium bromide 0.1 mg/kg) was used for intubation of the trachea. A transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) probe was inserted and utilized to monitor the cardiac function, volume status, and onset of new regional wall motion abnormalities.

Anesthesia was maintained with oxygen, nitrous oxide, Isoflurane, and intermittent boluses of fentanyl and pancuronium at appropriate intervals to maintain the bispectral index (BIS) value between 40 and 60. Heparin was administered at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg after harvesting the left internal mammary artery. The activated clotting time was maintained at >300 seconds throughout the operation. Protamine was administered once all proximal anastomoses were completed.

The PA catheter-derived data were recorded at the baseline (soon after insertion of the PA catheter under local anesthesia) at 3 minutes after induction, at 1 and 3 minutes after intubation, and again at 5 and 30 min after protamine administration. The hemodynamic data (HR and MAP) were recorded every 10 minutes during surgery except during distal anastomosis of the coronary arteries when it was recorded every 5 minutes after application of the Octopus tissue stabilizing system (OTSS) (Octopus Evolution Tissue Stabilizer, TS 2000, India Medtronic Pvt. Ltd.). The target HR was 70–80 beats/min, and 1 mg boluses of metoprolol were administered to maintain the HR in the desired range (provided that there was no contraindication to metoprolol).

After surgery, patients were transferred to the ICU for elective ventilation for further management and monitoring as per the institutional protocol. Post-operatively at 24 hours, the levels of troponin T and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) were measured. Preoperative bradycardia, intraoperative use of beta-blockers, time to extubation (hours), troponin T/BNP level after 24 hours (ng/ml), ICU stay (days), arrhythmia during ICU stay, use of inotropes, in-hospital morbidity, and mortality at 30 days were also recorded.

Statistical analysis

Sample size: On the basis of a pilot study, the mean value of HR 3 minutes post-intubation was 78.8 ± 5.36 and 71.2 ± 5.54 in groups I and II, respectively. Taking these values as a reference, the minimum required sample size with 99% power of study and 1% level of significance was 25 patients in each group. Therefore, the total sample size was taken as 50 patients (25 patients in each group). The statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL. Version 16.0 for windows). All quantitative/continuous variables were estimated using measures of central location (mean and median) and measures of dispersion (standard deviation and standard error). The normality of data was checked by skewness and Kolmogorov Smirnov tests of normality. For normally distributed data, the mean was compared by using analysis of variance (ANOVA). For skewed data, the Kruskall Wallis test was applied. For significant groups, the Mann–Whitney test was applied for the two groups. For time-related variables, repeated-measure ANOVA was applied, followed by paired t-test or Wilcoxon signed rank sum test. Qualitative or categorical variables were described as percentages and proportions. Proportions were compared by using the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test whichever was applicable. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at a significance level of α = 0.05.

RESULTS

The two groups were comparable with respect to the baseline demographic variables, Euroscore and preoperative comorbidities [Table 1]. The baseline hemodynamic and PA catheter-derived data were comparable in both groups, except for the HR which was significantly less in group II (group I 65.84 ± 4.72 vs. group II 59.60 ± 3.2 beats/min, P < 0.05). As the baseline HR was significantly less in group II, the difference in mean with respect to the baseline was calculated at each time point for HR and was compared between the two groups using the independent t-test. Comparison of the hemodynamic data is shown in Table 2. The HR increased significantly from the baseline at 1 min post-intubation in both groups and remained so throughout the study period. Between the groups comparison of the HR revealed that it was significantly more in group I at 30 min after protamine administration. Three minutes after anesthetic induction, the MAP decreased significantly in both groups and remained so throughout the study period. Between the groups, analysis revealed that there was no significant difference between the two groups. The stroke index (SI) decreased significantly after induction of anesthesia in group I and remained so during the study period. In group II, the SI decreased significantly 1 minute after intubation and remained so during the study period. There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to the SI. The cardiac index (CI) decreased significantly in group II after induction of anesthesia and remained so until 1 minute post-intubation (2.3 ± 0.4 and 2.1 ± 0.4, baseline vs. 1 minute post-intubation, respectively, P < 0.05), recovering to 2.2 ± 0.4 at 3 minutes post-intubation. The CI was comparable between the two groups throughout the study period. The two groups were comparable with respect to other PA catheter-derived parameters. The BIS values were maintained between 40 and 60 at all times throughout the study period.

Table 1.

Showing the demographic variables in the two groups

| Variable | Group I (control) n=25 | Group II (ivabradine) n=25 |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) (Mean±SD) | 54±5 | 55±7 |

| Sex (M/F) (n) | 24/1 | 23/2 |

| Weight (kg) (Mean±SD) | 67.9±9 | 68.8±7 |

| Height (cm) (Mean±SD) | 165±7.5 | 163±7.3 |

| BSA (m2) (Mean±SD) | 1.73±0.11 | 1.75±0.09 |

| EF (%) Mean±SD) | 54±5.7 | 52±6.3 |

| Euroscore (Mean±SD) | 2.3±0.7 | 2.4±0.7 |

| Diabetes (No) | 12 (48%) | 14 (56%) |

| Hypertension (No) | 13 (52%) | 14 (56%) |

| P=NS | ||

| TVD (No) | 11 (44%) | 10 (40%) |

Table 2.

Showing PAC-derived parameters in the two groups

| Parameter | Groups | Baseline | Post-induction 3 min | Post-intubation 1 min | Post-intubation 3 min | Post-protamine 5 min | Post-protamine 30 min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | Group I | 65.8±4.7 | 68.0±6.2 | 74±6.9# | 74.3±7.0# | 76.1±7# | 80.2±6.1# |

| Group II | 59.6±3.2* | 63.0±3.5 | 66.5±4.8# | 68.8±5.1# | 71.7±5.2# | 72.4±4.8*# | |

| MAP | Group I | 88.5±7.2 | 83.5±7.9# | 78.9±6.5# | 81.6±7.9# | 79.8±6.8# | 85.8±5.5 |

| Group II | 87.8±6.4 | 84.6±7.9# | 78.5±6.9# | 82.2±7.7# | 78.7±5.3# | 84.2±5.6 | |

| CVP | Group I | 4.2±1.4 | 3.5±1.3# | 3.2±1.1# | 3.3±1# | 4.1±1.3 | 5.8±1.4# |

| Group II | 4.4±1.2 | 3.7±1.7 | 3.4±1.0# | 3.2±1.1# | 4.6±1 | 6.4±0.9# | |

| MPAP | Group I | 14.9±3.1 | 12.9±2.4# | 14.1±2.1 | 12.9±2.1# | 13.4±2.3 | 16.8±2.6# |

| Group II | 15.4±2.1 | 13.2±2.3 | 14.8±2.2 | 13.9±2.1* | 14.8±2.2 | 17.4±2.2# | |

| PCWP | Group I | 6.4±1.8 | 5.6±1.9# | 5.4±1.6# | 5.5±1.8# | 6.8±1.3 | 9.7±1.5# |

| Group II | 7.1±3.2 | 5.5±1.7 | 5.5±1.6 | 5.3±2 | 7±1.1 | 10.2±1# | |

| SI | Group I | 37.3±7.1 | 31.4±5.7# | 29.8±4.8# | 30.5±5# | 31.4±5.2# | 33.5±5.6 |

| Group II | 38.1±7.2 | 33.3±7.4 | 30.4±6.2# | 31.1±6.5# | 32±7# | 34.7±6.1 | |

| CI | Group I | 2.5±0.4 | 2.2±0.4 | 2.2±0.3 | 2.2±0.4 | 2.5±0.4 | 2.7±0.5 |

| Group II | 2.3±0.4 | 2.1±0.5# | 2.1±0.4# | 2.2±0.4 | 2.3±0.5 | 2.5±0.5 | |

| SVRI | Group I | 2847±526.4 | 2744.6±739.7 | 2987.4±494.3 | 2839.5±616.9 | 2488.6±450.2# | 2405.6±512.8# |

| Group II | 2986.1±603.7 | 2995.6±636.0 | 3182.2±671.1 | 3018.2±561.6 | 2671.4±584.8# | 2521.8±532.2# | |

| PVRI | Group I | 226.1±99 | 235.8±85.9 | 279.8±108.6 | 234.7±89 | 204.9±72.3 | 214.5±71 |

| Group II | 313.4±75.6* | 296.8±72.6* | 363.9±74.1*# | 320.7±66.7* | 267.4±85.5* | 235.2±85.7# | |

| LVSWI | Group I | 41.6±10.4 | 29.7±8.8# | 31.5±6.6# | 31±6.53# | 30.8±5.8# | 33.9±6.6# |

| Group II | 40.1±9.8 | 32.3±8.4# | 32.2±8.1# | 32.1±8.4# | 31.1±7.3# | 33.8±6.9# | |

| RVSWI | Group I | 4.5±2 | 3.7±1.6# | 3.8±1.2# | 3.4±1# | 3.6±1.2 | 4.7±1.5 |

| Group II | 5.3±1.8 | 4.3±1.7*# | 4.8±1.7*# | 4.3±1.2*# | 4.5±1.7*# | 5.1±1.19 | |

| SVO2 | Group I | 75.8±6.7 | 75.7±7.1 | ||||

| Group II | 76±6.5 | 79.3±8.8 | |||||

| BIS | Group I | 92.3±4.1 | 61.7±6.4# | 58±4.6# | 56.7±4.2# | 51.6±4.4# | 50.6±3.5# |

| Group II | 91±3.0 | 62±2.6# | 59.5±2.8# | 58±3.40# | 52.1±3.4# | 52.4±2.8# |

(*P<0.05 between group I and group II). (#P<0.05 within the groups, compared to the baseline). MAP=mean arterial pressure, CVP=central venous pressure, MPAP=mean pulmonary artery pressure, PCWP=pulmonary artery wedge pressure, HR=heart rate, SI=stroke index, CI=cardiac index, SVRI=systemic vascular resistance index, PVRI=pulmonary vascular resistance index, LVSWI=left ventricular stroke work index, RVSWI=right ventricular stroke work index, SvO2=mixed venous saturation, BIS=bispectral index

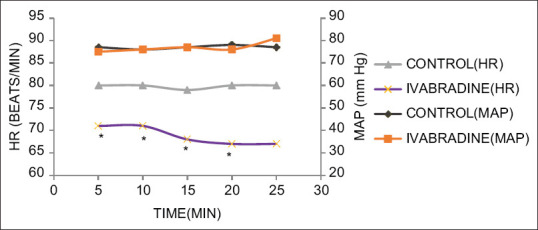

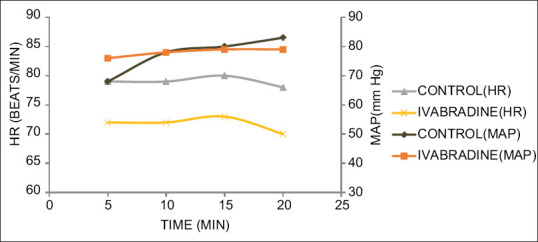

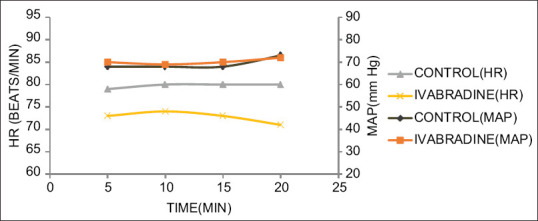

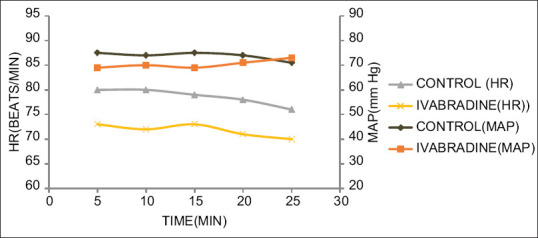

Figures 1-4 show the MAP and HR in the two groups during distal anastomosis of left anterior descending (LAD), obtuse marginal (OM), right coronary artery (RCA), and diagonal arteries respectively. There was no difference in the MAP; however, the HR was significantly less in group II during LAD anastomosis (group I vs. group II, 81.0 ± 6.2 vs 71.2 ± 5.0, P = 0.001, 80.0 ± 6.1 vs. 71.5 ± 5.0, P = 0.007, 79.5 ± 6.7, vs. 68.3 ± 14.2, P = 0.007, 80.7 ± 5.1 vs. 68.7 ± 7.8, P = 0.004, 80.03 ± 4.1 vs. 68.0 ± 12.7, P = 0.058 at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min after application of OTSS, respectively). The HR was not significantly different during OM anastomosis (group I vs. group II 79.6 ± 6.0, vs. 73.2 ± 4.3, P = 848, 80.1 ± 7.0 vs. 74.6 ± 4.8, P = 0.861, 80.04 ± 7.5 vs. 73.6 ± 4.5, P = 0.608, 80.3 ± 5.8 vs. 71.7 ± 0.6, P = 0.95, at 5, 10, 15, and 20 min after application of OTSS) during RCA anastomosis (group I vs. group II 80.9 ± 5.5 vs 73.7 ± 5.8, P = 0.261, 80.6 ± 5.5 vs. 72.3 ± 5, P = 0.223, 79.5 ± 5.7 vs. 73.1 ± 4.6, P = 0.214, 78.3 ± 6.8 vs. 71.9 ± 4.9, P = 0.632, 76.7 ± 7.6 vs. 70.8 ± 0, P = 0.913, at 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 min after OTSS application), and diagonal anastomosis (group I vs. group II 78.4 ± 6.0 vs. 72.9 ± 8.6, P = 0.279, 79.9 ± 6.7 vs. 72.6 ± 7.5, P = 0.295, 80.0 ± 6.1 vs. 73.5 ± 7.5, P = 0.167, 78.5 ± 7.4 vs. 70.3 ± 6.1, P = 0.188 at 5, 10, 15, and 20 min after OTSS application). Three (6%) patients required single inotropic support (low dose of dobutamine or low dose of adrenaline) during the intraoperative period. One patient in group I had severe hypotension which could not be managed with single inotrope; hence, two inotropes were used [Table 3]. Both groups were comparable in terms of time to extubation, stay in the ICU, requirement of inotropes, level of troponin T and BNP after 24 hours, incidence of arrhythmias, in-hospital morbidity, and mortality at 30 days [Table 3]. There was a significant difference in terms of intraoperative use of beta-blockers (20% in control, none in ivabradine) and preoperative bradycardia (baseline HR <60 beats/min was seen in 8% of patients in group I vs. 20% patients in group II, P < 0.05) [Table 3].

Figure 1.

MAP and HR changes during distal anastomosis of the LAD artery. *P < 0.05

Figure 4.

MAP and HR changes during distal anastomosis of the diagonal artery. *P < 0.05

Table 3.

Secondary outcome in the two groups

| Variable | Group I (control) n=25 | Group II (ivabradine) n=25 |

|---|---|---|

| Time to extubation | 17.96±2.58 | 17.72±2.4 |

| Troponin T level after 24 hours (ng/mL) | 0.778±0.52 | 0.845±0.47 |

| BNP Level after 24 hours (pg/mL) | 905.9±437 | 1042.1±672 |

| Stay in ICU | 2.88±0.52 | 2.84±0.68 |

| Arrhythmias during stay in ICU (SR/ST/SVT/VT/AF) | 20/3/1/0/1 | 21/1/1/1/1 |

| Preoperative bradycardia (n)* | 2 (8%) | 5 (20%) |

| Outcome Discharged/Expired | 25/0 | 25/0 |

| Inotropes None/Adrenaline/Dobutamine/Adrenaline and Dobutamine) | 22/1/0/1 | 23/1/1/0 |

| IABP | Nil | Nil |

| Intraoperative Metoprolol (n)* | 5 (20%) | Nil |

| In-hospital morbidity (GI disturbance/sleep disturbance/visual disturbance) | 2 (8%) | 3 (12%) |

| 30-day Mortality | Nil | Nil |

*P<0.05. BNP=Brain natriuretic peptide, SR=sinus rhythm, ST=sinus tachycardia, SVT=supraventricular tachycardia, VT=ventricular tachycardia, AF=atrial fibrillation

Figure 2.

MAP and HR changes during distal anastomosis of the OM artery. *P < 0.05

Figure 3.

MAP and HR changes during distal anastomosis of the right coronary artery. *P < 0.05

Post-operatively in the ICU, three patients had sinus tachycardia (ST), whereas one patient had supraventricular tachycardia (SVT) and atrial fibrillation (AF) in group I, whereas in group II, ST, SVT, AF, and ventricular tachycardia (VT) were observed in one patient [Table 3].

DISCUSSION

Thus summarizing, the present study shows that patients receiving preoperative ivabradine maintained a significantly lower HR during the intraoperative period in comparison to the control group. The increase in the HR following endotracheal intubation was milder in group II. This was accompanied by similar decreases in MAP in both groups. During rest of the intraoperative course, a similar trend in the HR and MAP was seen in group II patients maintaining a lower HR and comparable MAP. Metoprolol in 1 mg boluses was administered with very careful monitoring in 5 (20%) patients in group I when the HR exceeded 85 beats/min despite the patient being adequately anesthetized (BIS <60) and preloaded. When comparing secondary outcomes, the requirement of beta-blockers was significantly less in group II, whereas both the groups were comparable in terms of time to extubation, stay in the ICU, requirement of inotropes, levels of troponin T and BNP after 24 hours, incidence of arrhythmias, and in-hospital morbidity.

OPCAB surgery is widely practiced in India for coronary revascularization. This procedure is associated with considerable hemodynamic perturbations, of HR and MAP, especially during intubation and distal graft anastomosis of the coronary arteries. The HR is an important determinant of myocardial oxygen demand as well as coronary filling time (supply); hence, tachycardia in patients with ischemic heart disease is a risk factor for the development of perioperative myocardial ischemia and infarction. Also, an increase in HR and force of contraction can interfere with a meticulous distal anastomosis of the coronaries despite the availability of improved stabilizers and surgeon’s expertise. The anesthesiologist strives to keep the HR between 70 and 80 beats/min while trying to maintain a MAP of >60 mm of Hg. When there is tachycardia with hypertension despite patients being adequately anesthetized, and sufficiently preloaded, beta-blockers are used in the intraoperative period to optimize the HR. However, beta-blockers cannot be used when tachycardia is associated with hypotension, especially during distal anastomosis of the coronaries. In this situation, a drug with negative chronotropic effect but without any effect on inotropy is most useful. Ivabradine has negative chronotropic effects without negative inotropic or lusitropic effects on the heart, which could be very valuable in this situation.

Ivabradine has been extensively studied in non-surgical scenarios, and we believe that the present study is the first study that has evaluated its efficacy and safety during anesthetic induction and distal coronary anastomosis in patients undergoing elective OPCAB surgery. The only other study evaluating the safety and efficacy of ivabradine in patients undergoing cardiac surgery (elective CABG or valvular surgery) is by Iliuta et al.[14] They included patients who had conduction abnormalities but were in sinus rhythm at the time of enrolment, LV systolic dysfunction or both. Their patients were divided into three groups (those receiving metoprolol, ivabradine, or metoprolol plus ivabradine) for 2 days preoperatively and at least 10 days post-operatively. They looked into post-operative primary endpoints such as composites of 30-day mortality, in-hospital AF, in-hospital three-degree AV block and need for pacing, worsening HF, and duration of hospital stay in addition to side effects such as bradycardia, gastrointestinal symptoms, sleep disturbances, and cold extremities. They reported HR reduction and prevention of post-operative AF or tachyarrhythmias with combined therapy to be more effective than metoprolol or ivabradine alone and the frequency of pacing and worsening HF less in the ivabradine group. They also reported that the patients treated with ivabradine had shorter hospitalization periods.

In the non-surgical scenario, the hemodynamic effects of ivabradine infusion (0.1 mg/Kg infused over 90 minutes followed by 0.05–0.075 mg/Kg in the subsequent 90 minutes) in 10 patients with advanced heart failure (NYHA class III) were evaluated by Ferrari et al.[19] for 24 hours. They reported a significant reduction in the HR up to a maximum of 27% (to 68 ± 9/min) at 4 hours, without decreasing CI. Ivabradine increased the SV and LV systolic work by a maximum of 51% (to 66 ± 17 ml) and 53% (to 58 ± 20 g) at 4 hours. Furthermore, no serious adverse events were reported in these 10 patients.

The benefits of using ivabradine along with beta-blockers and CCB in patients with CAD have also been described in non-surgical scenarios by Fox et al. and Swedberg et al.[13,17] The results of these studies underscored the importance of HR reduction with ivabradine for improvement in clinical outcomes. Both these trials were international, multicentered, randomized, double-blind, and placebo-controlled trials in patients with CAD and LV dysfunction and CAD with moderate-to-severe CHF. The participating patients were being treated with best preventive therapy including beta-blockers. The HR was more than 70/min. Fox et al. reported a significant 36% (sample size of 10,917 patients) reduction in fatal and nonfatal MI, a 30% reduction in coronary revascularization, but no improvement in the HF outcome. Swedberg et al.[17] reported an 18% decrease in cardiovascular death or hospital admission for worsening HF (over a median follow-up period of 22.9 months) in patients treated with ivabradine. The average reduction in HR was 15/min from a baseline value of 80/min. They suggested an added magnitude of benefit in those with a HR higher than the median; that is, the magnitude of benefit varied directly with pre-treatment HR. However, no significant difference in the primary end points of cardiovascular death or nonfatal myocardial infarction was found in the study by Fox et al.[20] (SIGNIFY trial) comparing ivabradine with placebo in 19,102 patients with stable CAD and without clinical HF over a period of 28 months. However, the QUALIFY survey, which included 6669 out-patients with heart failure, observed that after hospitalization, good adherence for treatment with combination therapy of angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin receptor antagonists (ACE-I), mineralocorticoid antagonists (MRA), and ivabradine had reduced mortality during a 6-month follow-up period.[21]

In the present study, while assessing the patients for the side effects of the drug, the authors found that 20% of the patients in group II had bradycardia (defined as HR <60 beats/min) preoperatively, whereas the incidence of the same in group I was 8%. However, bradycardia was not associated with hemodynamic derangement. The authors also observed the patients for post-operative arrhythmias and found no difference in the two groups with respect to development of AF, SVT, or VT during their stay in the hospital. In the SHIFT study,[17] the authors reported a continuously stable lower HR with ivabradine compared to placebo with a mean change of 10.9, 9.1, and 8.1 beats/min at 28 days, 1 year, and end of study, respectively. They reported symptomatic bradycardia in 5% of the ivabradine group, which was significantly higher (P < 0.0001) than in the 1% in the placebo group. They reported that AF was more frequent (P = 0.012) with ivabradine (9%) than with placebo (8%), but there was no significant difference in the treatment withdrawal rate (4% vs. 3% respectively, P = 0.0137).

In the present study, both groups were comparable as far as overall in-hospital morbidity and 30-day mortality were concerned; ivabradine was not found to be associated with improved outcomes. This was an observation as the present study was not undertaken with this objective. Therefore, larger trials with ivabradine are necessary to prove mortality benefits in patients undergoing OPCAB surgery.

The present study had the following limitations. The sample size was small, patients with EF <40% were not included, patients with HR >70 beats/min were included, patients were not observed for arrhythmias during the entire period of hospitalization due to limited resources, and the choice and initiation of inotropic support was decided by the attending anesthesiologist as per his/her preferences. Further studies with larger sample sizes and inclusion of patients with poor LV function (EF <40%) for CABG may provide greater insights into the beneficial role of ivabradine in such patients.

CONCLUSION

Ivabradine is a safe drug to be administered along with a beta-blocker (metoprolol) and amiodarone preoperatively in patients undergoing OPCAB grafting surgery. It reduces the need for beta-blockers in the intraoperative period. Further studies are needed to evaluate the beneficial effects of perioperative ivabradine in patients with moderate-to-severe LV dysfunction.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form, the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the help and guidance provided by Prof. Deepak Tempe in preparation of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Virmani S, Tempe DK. Anaesthesia for off-pump coronary artery surgery. Annals Card Anaesth. 2007;10:65–71. doi: 10.4103/0971-9784.37931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kloner RA, Chaitman B. Angina and its management. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2017;22:199–209. doi: 10.1177/1074248416679733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Riccioni G. Focus on Ivabradine: A heart rate-controlling drug. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009;7:107–13. doi: 10.1586/14779072.7.2.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rao HK, Gupta RS, Singh SR. Ranolazine and Ivabradine –Their current use. Medicine Update. 2010;20:351–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sulfi S, Timmis AD. Ivabradine -the first selective sinus node If channel inhibitor in the treatment of stable angina. Int J Clin Pract. 2006;60:222–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2006.00817.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Camm AJ, Lau CP. Electrophysiological effects of a single intravenous administration of Ivabradine (S16257) in adult patients with normal baseline electrophysiology. Drugs. 2003;4:83–9. doi: 10.2165/00126839-200304020-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joannides R, Moore N, Iacob M, Compagnon P, Lerebours G, Menard JF, et al. Comparative effects of Ivabradine, a selective heart-rate lowering agent, and propranolol on systemic and cardiac haemodynamics at rest and during exercise. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;61:127–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2005.02544.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Manz M, Reuter M, Lauck G, Omran H, Jung W. A single dose of Ivabradine, a novel If inhibitor, lowers heart rate but does not depress left ventricular function in patients with left ventricular dysfunction. Cardiology. 2003;100:149–55. doi: 10.1159/000073933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulder P, Barbier S, Chagraoui A, Richard V, Henry JP, Lallemend F, et al. Longterm heart rate reduction induced by the selective If current inhibitor ivabradine improves left ventricular function and intrinsic myocardial structure in congestive heart failure. Circulation. 2004;109:1674–9. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000118464.48959.1C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McMurray JJV, Adampoulous S, Anker SD, Auricchio A, Bohm M, Dickstein K, et al. ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2012: The Task Force for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute and Chronic Heart Failure 2012 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1787–847. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heush G, Skyschally A, Gres P, Caster P, Schilawa D, Schulz R. Improvement of regional myocardial blood flow and function and reduction of infarct size with ivabradine: Protection beyond heart rate reduction. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:2265–75. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehn337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skychally A, Schulz R, Heush G. Pathophysiology of myocardial infarction: Protection by ischemic pre and postconditioning. Herz. 2008;33:88–100. doi: 10.1007/s00059-008-3101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fox K, Ferrari R, Tandera M, Steg PG, Ford I. Rationale and design of randomized, double blind, placebo controlled trial of Ivabradine in patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction: The morbidity-mortality evaluation of the If inhibitor Ivabradine in patients with stable coronary artery disease and left ventricular dysfunction (BEAUTIFUL) Study. Am Heart J. 2006;152:860–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2006.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iliuta L, Rac-Albu M. Ivabradine versus beta-blockers in patients with conduction abnormalities or left ventricular dysfunction undergoing cardiac surgery. Cardiol Ther. 2014;3:13–26. doi: 10.1007/s40119-013-0024-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nguyen LS, Squara P, Amour J, Carbognani D, Bouabdallah K, Thierry S, et al. Intravenous Ivabradine versus placebo in patients with low cardiac output syndrome treated by dobutamine after elective coronary artery bypass surgery: A phase 2 exploratory randomized controlled trial. Critical Care. 2018;22:193. doi: 10.1186/s13054-018-2124-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abdel-Salam Z, Nammas W. Atrial fibrillation after coronary artery bypass surgery: Can Ivabradine reduce its occurrence? J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2016;27:670–6. doi: 10.1111/jce.12974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Swedberg K, Komajda M, Bohm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Tavazzi L. Rationale and design of a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled outcome trial of ivabradine in chronic heart failure: The Systolic heart failure treatment with If inhibitor ivabradine trial (SHIFT) Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:75–81. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bocchi EA, Bohm M, Borer JS, Ford I, Komajda M, Swedberg K, et al. Effect of combining ivabradine and ?-blockers: Focus on the use of carvedilol in the SHIFT population. Cardiology. 2015;131:218–24. doi: 10.1159/000380812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ferrari GM, Mazzuero A, Agnesina L, Bertoletti A, Lettino M, Campana C, et al. Favourable effects of heart rate reduction with intravenous administration of ivabradine in patients with advanced heart failure. Eur J Heart Failure. 2008;10:550–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejheart.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fox K, Ford I, Steg PG, Tardif JC, Tendera M, Ferrari R. Ivabradine in stable coronary artery disease without clinical heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1091–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1406430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komajda M, Cowie MR, Tavazzi L, Ponikowski P, Anker SD, Filippatos GS QUALIFY Investigators. Physicians'guideline adherence is associated with better prognosis in out-patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: The QUALIFY International registry. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:1414–23. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]