Abstract

We examined the effect of immune stimulation by a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) immunogen (Remune) compared to a non-HIV vaccine (influenza) on HIV-1-specific immune responses in HIV-1-seropositive subjects. HIV-1 p24 antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation was not augmented after immunization with the influenza vaccine. In contrast, subjects increased their lymphocyte proliferative responses to p24 antigen after one immunization with HIV-1 immunogen (Remune) (gp120-depleted inactivated HIV-1 in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant). Furthermore, p24 antigen-stimulated β-chemokine production (RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β) was also augmented after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen but not influenza vaccine. Taken together, these results suggest that in this cohort, HIV-specific immune responses to p24 antigen can be augmented after immunization with an HIV-1 immunogen. The ability to upregulate immune responses to the more conserved core proteins may have important implications in the development of immunotherapeutic interventions for HIV-1 infection.

The impairment of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)-specific immune function occurs quite early in HIV-1 disease (9). With the advent of potent antiviral combinations, the concept of immune reconstitution has become an area of increasing interest and a potential goal for the treatment of HIV-1 infection (8).

The correlates of protection in HIV-1 infection remain an area of intense study and debate. Most studies of lymphocyte proliferative function in HIV-1 infection have examined responses to the most heterogenous component of the HIV-1 virus, the envelope proteins (i.e., gp120, gp160) (6). Proliferative immune responses to envelope proteins appear to poorly correlate with clinical surrogate markers such as viral load (7). In contrast, previous studies of lymphocyte proliferation in response to core proteins such as p24 antigens have revealed positive associations with CD4 counts (11, 13). Furthermore, a recent study has revealed that vigorous lymphocyte proliferative responses to p24 antigen correlated with control of plasma viremia (16). In addition, peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) production of β-chemokines such as RANTES in response to Gag peptides has also been shown to inversely correlates with viral burden (4a).

We hypothesized that immune responses to p24 induced by an HIV-1 immunogen may have important implications in the development of an immune-based therapy approach to treat HIV-1 infection. We examined the effect of immune stimulation by an HIV-1 immunogen (Remune) (gp120-depleted inactivated HIV-1 antigen in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant) compared to a non-HIV vaccine (influenza) on HIV-1-specific immune responses in HIV-1-seropositive subjects. HIV-1 p24 antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation was not augmented after immunization with an influenza vaccine. In contrast, subjects increased their lymphocyte proliferative responses to p24 antigen after being immunized with HIV-1 immunogen (Remune). Furthermore, p24 antigen-stimulated β-chemokine production (RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β) was also augmented after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen but not influenza vaccine.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Six HIV-1-seropositive subjects were randomly selected and enrolled after informed consent was obtained in an open-label treatment study which had been approved by the institutional review board. Subjects received the influenza virus trivalent vaccine, types A and B (Wyeth-Ayerst), 1996–97 formula. Eight weeks post-influenza immunization, these subjects were immunized with one dose (10 U) of a gp120-depleted inactivated HIV-1 antigen in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (HIV-1 immunogen). HIV-1-specific immune responses were measured in these subjects before and 4 and 8 weeks post-influenza vaccination (pre-HIV-1 immunogen) and at 4 and 8 weeks post-HIV-1 immunogen. Influenza antibody titers to H1N1 subunits were measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay in blinded samples at the California Department of Public Health, Berkeley. The mean CD4 count of this cohort at baseline was 419 cells/mm3. Three of the six subjects had undetectable viral load (<400 copies/ml), and all were on antiviral drug suppressive therapy.

Native p24 was preferentially lysed from purified inactivated HIV-1 with 2% Triton X-100 and then purified with Pharmacia Sepharose Fast Flow S resin. Chromatography was carried out at pH 5.0, and p24 was eluted with a linear salt gradient. Purity of the final product was estimated by both sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and reverse-phase high-performance liquid chromatography to be >99%, with no immunoreactivity to class I or class II antibodies on Western blot. Phytohemagglutinin (PHA) antigen was obtained from Sigma Pharmaceuticals (St. Louis, Mo.). Tetanus toxoid antigen was from Connaught Laboratories.

For the lymphocyte proliferation assays, fresh PBMCs from HIV-1-seropositive subjects were seeded in a round-bottom 96-well plate (Falcon) at 2 × 105 cells/well in 200 μl of RPMI (GIBCO) containing 10% human AB serum and 1% antibiotics (complete medium). Cells were cultured with medium alone, tetanus toxoid antigen (2.2 μg/ml), PHA (10 μg/ml), or native p24 (5 μg/ml). All assays were done in triplicate. After 6 days of incubation, supernatants were harvested from each well (100 μl) and the cells were labeled with 1 μCi of [3H]thymidine in complete medium. On day 7 before the harvest, beta-propiolactone (final concentration, 1:400) was added to each well to neutralize any virus produced during the incubation period. Cells were harvested after a 2-h incubation in beta-propiolactone at 37°C, and incorporated label was measured by scintillation counting. Geometric mean counts per minute were calculated from the triplicate wells with and without antigen. Results were calculated as lymphocyte stimulation indices (LSI), which are the geometric mean counts per minute of the cells incubated with antigen divided by the geometric mean counts per minute of the cells without antigen (cells incubated in medium alone). Supernatants were collected on day 6 and frozen at −70°C for β-chemokine measurement from control (no antigen) and from p24 antigen-stimulated wells. RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β were quantified in duplicate by commercial enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay from R & D Systems (Minneapolis, Minn.). For comparison, values greater than the upper limit of the assay for MIP-1α and MIP-1β (1,000 pg/ml) were assigned a value of 1,000. Plasma RNA was assayed in blinded samples by Advanced Bioscience Laboratories, Inc., using the NASBA method (15). The Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test was utilized to compare assay results at weeks 4 and 8 with those at time zero. For MIP-1β at 4 weeks post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen, with all subjects achieving the upper limit of the assay, means were calculated for the comparison group, and a one-sample t test was performed. All P values presented are two-tailed.

RESULTS

Table 1 lists the baseline values for CD4 count, antiviral drug therapy, and lymphocyte proliferation in response to PHA and tetanus. Three subjects had changes in their antiviral drug regimens during the course of this study. Subject 1 had his ritonavir discontinued 7 days after day 1 and began indinavir 26 days after day 1. Subject 3 discontinued indinavir 8 days after day 1 and was started on ritonavir. Subject 4 had indinavir added to his antiviral drug regimen 8 days after day 1. The other subjects remained on stable antiviral drug regimens during the course of the study. Overall, subjects had intact lymphocyte proliferative responses to mitogens (PHA) at baseline but not to tetanus or p24 antigens (Fig. 1).

TABLE 1.

Baseline CD4 cell counts, antiviral drug use prior to influenza vaccine immunization, and lymphocyte proliferation in response to PHA and tetanusa

| Subject | Therapy (mo)b | No. of CD4 cells/mm3 [413.5] | LSI

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHA [147.9] | Tetanus [1.902] | |||

| 1 | d4T (8), 3TC (8), retonivir (3) | 581 | 30.34 | 2.30 |

| 2 | d4T (9), 3TC (3), indinavir (3) | 441 | NDc | 4.27 |

| 3 | 3TC (4), d4T (4), indinavir (4) | 408 | 29.91 | 1.18 |

| 4 | 3TC (11), ddC (11) | 183 | 57.01 | 1.41 |

| 5 | AZT (12), 3TC (12) | 715 | 474.39 | 0.72 |

| 6 | ddI (4), d4T (4), indinavir (4) | 153 | ND | 1.53 |

Means are indicated in brackets.

d4T, stavudine; 3TC, lamivudine; ddC, dideoxycytosine; AZT, zidovudine; ddI, dideoxyinosine.

ND, not done.

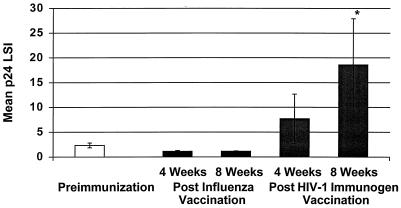

FIG. 1.

Mean p24 antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation before and after immunization with influenza vaccine and HIV-1 immunogen. A significant increase in p24 antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation was observed at 8 weeks post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen. ∗, P = 0.04.

HIV-1 antigen-specific immune responses were measured by lymphocyte proliferation before and after influenza virus vaccine immunization. As shown in Fig. 1, lymphocyte proliferation in response in native p24 decreased after influenza vaccination at week 4 (P = 0.04; baseline mean LSI ±) standard error [SE], 2.3 ± 0.49; week 4 postimmunization mean ± SE, 1.13 ± 0.17) and at week 8 (P = 0.06; mean LSI ± SE, 1.15 ± 0.06) compared to preimmunization levels. Of note, influenza antibody levels increased 1 month after immunization to H1N1 protein (P = 0.03; preimmunization mean titer, 28; postimmunization mean titer, 176).

In contrast, after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen there was a significant increase in lymphocyte proliferation to p24 antigen at week 8 (P = 0.03; preimmunization mean LSI ± SE, 2.3 ± 0.49; postimmunization, 18.44 ± 9.4) but not at week 4 (P = 0.82; preimmunization mean LSI ± SE, 2.3 ± 0.49; postimmunization, 7.71 ± 4.95) compared to preimmunization levels (Fig. 1). Lymphocyte proliferation in response to a control antigen (tetanus) did not significantly change 8 weeks post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen (P < 0.05).

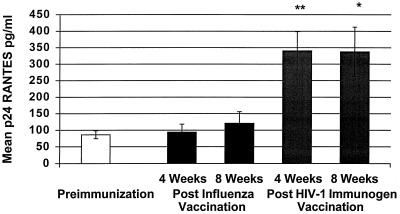

Similarly, p24 antigen-stimulated RANTES production increased post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen at 4 weeks (P = 0.002; preimmunization mean ± SE, 86.38 ± 11.77 pg/ml; postimmunization mean ± SE, 340.2 ± 58.62 pg/ml) and 8 weeks (P = 0.02; preimmunization mean ± SE, 86.38 ± 11.77 pg/ml; postimmunization mean ± SE, 337.6 ± 74.90 pg/ml) but not after influenza vaccine immunization (Fig. 2). Significantly higher RANTES production with p24 antigen stimulation was observed compared to unstimulated PBMCs at 4 weeks (P = 0.02) and 8 weeks (P = 0.004) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen.

FIG. 2.

Mean p24 antigen-stimulated RANTES production from PBMCs before and after immunization with influenza vaccine and HIV-1 immunogen. An increase in p24 antigen-stimulated RANTES from PBMCs was demonstrated at 4 weeks (∗∗, P = 0.002) and 8 weeks (∗, P = 0.02) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen.

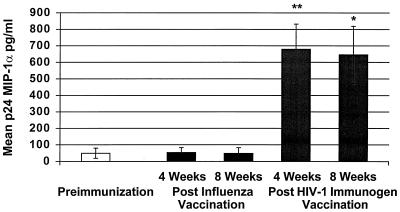

We also examined p24-stimulated MIP-1α and MIP-1β production. As shown in Fig. 3, p24 antigen MIP-1α production was augmented after immunization with Remune at 4 weeks (P = 0.004; preimmunization mean ± SE, 49.54 ± 30.62 pg/ml; postimmunization mean ± SE, 679.7 ± 152.3 pg/ml and at 8 weeks (P = 0.009; postimmunization mean ± SE, 645.7 ± 173 pg/ml) but not after influenza vaccination. Significantly higher MIP-1α production with p24 antigen stimulation was observed compared to unstimulated PBMCs at 4 weeks (P = 0.002) and 8 weeks (P = 0.02) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen.

FIG. 3.

Mean p24 antigen-stimulated MIP-1α production from PBMCs before and after immunization with influenza vaccine and HIV-1 immunogen. An increase in p24-stimulated MIP-1α production was demonstrated at 4 weeks (∗∗, P = 0.004) and 8 weeks (∗, P = 0.009) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen.

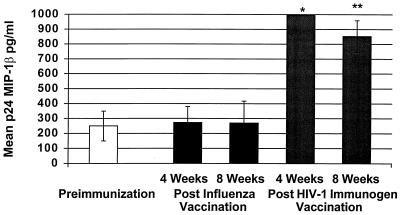

Similarly, p24-stimulated MIP-1β production was significantly increased at 4 weeks (P = 0.0006) and 8 weeks (P = 0.0043) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen (preimmunization mean ± SE, 250 ± 99.41 pg/ml; mean at 4 weeks, 1,000 pg/ml; mean at 8 weeks ± SE, 852.9 ± 106 pg/ml) but not after influenza vaccination (Fig. 4). Significantly higher MIP-1β production with p24 antigen stimulation was observed compared to unstimulated PBMCs at 4 weeks (P = 0.02) and 8 weeks (P = 0.03) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen.

FIG. 4.

Mean p24 antigen-stimulated MIP-1β production from PBMCs before and after immunization with influenza vaccine and HIV-1 immunogen. An increase in MIP-1β production was demonstrated at 4 weeks (∗, P = 0.0006) and 8 weeks (∗∗, P = 0.004) post-immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen.

Control well (no antigen) MIP-1α (postimmunization mean ± SE, 158.1 ± 146.7 pg/ml) and MIP-1β (postimmunization mean ± SE, 225.1 ± 155.8 pg/ml) did not significantly change (P > 0.05) 8 weeks post-immunization with Remune compared to baseline values (mean MIP-1α ± SE, 34.01 ± 5.2 pg/ml; mean MIP-1β ± SE, 128.4 ± 42.11 pg/ml). There was a slight decrease (P = 0.04) in control well RANTES at 8 weeks post-treatment with Remune (mean ± SE, 45.98 ± 16.47 pg/ml) compared to pretreatment levels (mean ± SE, 85.73 ± 10.96 pg/ml). Viral load remained undetectable in three of six subjects at 8 weeks postimmunization with HIV-1 immunogen (Table 2). Three subjects declined in viral load at 8 weeks postimmunization.

TABLE 2.

Plasma RNA levels before and 8 weeks after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen

| Subject | Copies/ml

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 8 weeks | |

| 1 | <400 | <400 |

| 2 | <400 | <400 |

| 3 | 12,000 | 2,300 |

| 4 | 15,000 | <400 |

| 5 | 8,100 | 3,500 |

| 6 | <400 | <400 |

DISCUSSION

In this study we examined HIV-1-specific immune responses post-immunization with an HIV-1 immunogen. Compared to responses post-immunization with an influenza vaccine, recognition of HIV antigens as measured by lymphocyte proliferation in response to p24 antigen was augmented after immunization with an HIV-1 immunogen in this cohort. In contrast, responses to a recall antigen (tetanus) did not significantly change after immunization. Furthermore, HIV-1-specific immune responses did not increase following immunization with an influenza vaccine, demonstrating the specificity of the response of the immune system to the HIV-1 immunogen. In a previous study we demonstrated a strong association between proliferative responses to the gp120-depleted whole antigen and native p24 antigen in HIV-1 immunogen-vaccinated subjects (1). Thus, this study and previous studies of HIV-1 immunogen-vaccinated subjects support the notion that immune responses after immunization are, in part, directed against the more conserved core epitopes of the virus such as p24. Furthermore, p24 antigen-stimulated PBMC production of MIP-1α, MIP-1β, and RANTES was also augmented after immunization. Taken together, these results demonstrate that HIV-1-specific immune responses were enhanced after immunization with Remune. Alternatively, due to the crossover design of the study, late effects of influenza vaccine on HIV immune function, although unlikely, cannot be ruled out.

The impairment in lymphocyte proliferation in response to HIV-1 antigens is a relatively early functional defect of cell-mediated immunity found in HIV-1-infected individuals. This defect, as measured by DNA synthesis in response to HIV antigens, appears to distinguish HIV-1 infection from other latent or nonlatent viral infections. Furthermore, while HIV-1-infected individuals manifest this defect prior to disease progression, most HIV-1-infected disease-free chimpanzees maintain strong proliferative responses to HIV antigens (20). Initial observations by Wahren et al. revealed poor lymphocyte proliferative responses to whole HTLV-IIIB antigens (19). In contrast, subjects were able to mount responses against cytomegalovirus, herpes simplex virus, and PHA. Defects in HIV-1-specific lymphocyte proliferative responses prior to the loss of recall, allogeneic, and mitogen antigen responses in HIV-1-infected individuals have now been described in numerous clinical studies (2, 5, 14, 16). Recently, it has been shown that HIV-1-specific lymphocytes responses to p24 antigen could be augmented in subjects on antiviral therapy prior to seroconversion (16). The magnitude of both p24 antigen-stimulated lymphocyte proliferation and chemokine production after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen in this study are comparable to levels found in individuals with nonprogressive HIV-1 disease (16). No previous studies of other therapeutic immunizations have demonstrated an increase in lymphocyte proliferation and chemokine production in response to the highly conserved core proteins of the virus, as demonstrated in this study.

We previously had shown an increase in lymphocyte proliferation and RANTES production in response to the whole gp120-depleted inactivated HIV-1 antigen (10) after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen. Individuals immunized with the HIV-1 immunogen have been demonstrated to mount lymphocyte proliferative responses across clades of different whole HIV-1 antigens (11). It should be noted that in the present study we examined HIV-specific responses after only one immunization. In previous studies we have observed lymphocyte stimulation indices of greater than 100 with continued immunizations in some subjects in response to both gp120-depleted inactivated HIV-1 and p24 antigens (11).

β-Chemokines appear to have anti-HIV-1 activity (3) against macrophage-tropic strains of HIV-1 in vitro, and the measurement of PBMC production of these substances may indicate an attempt on the part of the host to control virus production. Interestingly, a recent study has suggested that β-chemokine may be elevated in exposed but uninfected hemophiliacs and their regulation may be independent of chemokine receptor genotype (4b). Furthermore, in a study of 245 HIV-infected subjects, the level of MIP-1β was associated with a decreased risk of progressing to AIDS or death (18).

β-chemokine production in response to core proteins has been observed to inversely correlate with virus load in the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (4a) in subjects not on antiviral drug therapy. In the current study p24 antigen-stimulated production of all three β-chemokines was augmented after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen. The ability to induce a memory response and upregulate production of β-chemokines specifically against HIV-1 may provide an alternate strategy to delay progression in HIV-infected subjects. The mechanism of the protective effect of the β-chemokines is unknown but could be hypothesized to be related to the binding of these substances to CCR5, the coreceptor for HIV-1, and thereby preventing new infection of CD4 lymphocytes. It has yet to be determined whether immunization increases the newly described macrophage-derived chemokine which has activity against T-cell-tropic virus strains (12).

In the current study, as three of the six subjects in this cohort had undetectable viral load at baseline, it was not possible to demonstrate an impact of immunization on this important surrogate marker. Furthermore, there was no significant association between baseline RNA copy number and β-chemokine production after treatment with Remune. In spite of optimal viral suppression, though, the same subjects failed to have strong functional HIV-1-specific immune responses as measured by lymphocyte proliferation and chemokine production prior to immunization. Although preliminary and based on a small number of subjects, these observations are consistent with other studies suggesting that there may be only partial immune reconstitution even with an optimal antiviral drug regimen (1, 3a, 4, 17). It is unclear whether this lack of immune reconstitution may be due to a partial depletion of antigen-specific lymphocytes after HIV-1 seroconversion. The ability to induce HIV-specific responses with an HIV-1 immunogen would argue against complete antigen-specific clonal deletion. Nevertheless, optimal improvement in functional immune responses after immunization may be realized in the context of viral suppression with highly active antiretroviral therapy.

Taken together, these preliminary results suggest that in this cohort, HIV-specific immune response against p24 was augmented after immunization with the HIV-1 immunogen but not after immunization with influenza vaccine. The ability to specifically upregulate immune responses to the more conserved core HIV-1 proteins may have important implications in the development of an immunotherapeutic intervention for HIV-1 infection. Studies are under way to determine the clinical utility of augmenting HIV-1-specific immunity with Remune in subjects on concomitant antiviral drug therapy.

REFERENCES

- 1.Autran B, Carcelain G, Li T S, Blanc C, Mathez D, Tubiana R, Katlama C, Debre P, Leibowitch J. Positive effects of combined antiretroviral therapy on CD4+ T cell homeostasis and function in advanced HIV disease. Science. 1997;277:112–116. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caruso A, Licenziati S, Canaris A D, Corulli M, De Francesco M A, Cantalamessa A, Fallacara F, Fiorentini S, Balsari A, Turano A. T cells from individuals in advanced stages of HIV-1 infection do not proliferate but express activation antigens in response to HIV-1-specific antigens. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;15:61–69. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199705010-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Arya S K, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3a.Connick E, et al. Proceedings of the 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Chicago, Ill., 1 to 5 February 1998. 1998. Abstract LB14. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connors M, Kovacs J A, Krevat S, Gea-Banacloche J C, Sneller M C, Flanigan M, Metcalf J A, Walker R E, Falloon J, Baseler M, Feuerstein I, Masur H, Lane H C. HIV infection induces changes in CD4+ T-cell repertoire that are not immediately restored by antiviral or immune-based therapies. Nat Med. 1997;3:533–540. doi: 10.1038/nm0597-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4a.Ferbas J, et al. Proceedings of the Ninth Annual Meeting of the National Cooperative Vaccine Development Groups, Bethesda, Md., 4 to 7 May 1997. 1997. Poster 91. [Google Scholar]

- 4b.Gringeri A, et al. Abstract 111. Proceedings of the Institute of Human Virology 1997 Annual Meeting, Baltimore, Md., 15 to 21 September 1997. J Hum Virol. 1998;1(2):129. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krohn K, Robey W G, Putney S, Arthur L, Nara P, Fischinger P, Gallo R C, Wong-Staal F, Ranki A. Specific cellular immune response and neutralizing antibodies in goats immunized with native or recombinant envelope proteins derived from human T-lymphotropic virus type IIIB and in human immunodeficiency virus-infected men. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1987;84:4994–4998. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.14.4994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krowka J F, Stites D P, Jain S, Steimer K S, George-Nascimento C, Gyenes A, Barr P J, Hollander H, Moss A R, Homsy J M, et al. Lymphocyte proliferative responses to human immunodeficiency virus antigens in vitro. J Clin Invest. 1989;83:1198–1203. doi: 10.1172/JCI114001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kundu S K, Katzenstein D, Valentine F T, Spino C, Efron B, Merigan T. Effect of therapeutic immunization with recombinant gp160 HIV-1 vaccine on HIV-1 proviral DNA and RNA: relationship to cellular immune responses. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;15:269–274. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199708010-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lange J M A. Current problems and the future of antiretroviral drug trials. Science. 1997;276:548–550. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5312.548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moss R B, Richieri S P, Ferre F, Daigle A E, Trauger R, Theofan G, Giermakowska W, Lanza P, Brostoff S, Carlo D J, Jensen F C. HIV-1-specific functional immune measurements as markers of disease progression. J Biomed Sci. 1997;4:127–131. doi: 10.1007/BF02255640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moss R B, Trauger R J, Giermakowska W K, Turner J L, Wallace M R, Jensen F C, Richieri S P, Ferre F, Daigle A E, Duffy C, Theofan G, Carlo D J. Effect of immunization with an inactivated gp120-depleted HIV-1 immunogen on β-chemokine and cytokine production in subjects with HIV-1 infection. J Acquired Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1997;14:343–350. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199704010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moss R B, Giermakowska W, Lanza P, Turner J L, Wallace M R, Jensen F C, Theofan G, Richieri S P, Carlo D J. Cross clade immune responses after immunization with a whole-killed gp120-depleted HIV-1 immunogen in incomplete Freund’s adjuvant (HIV-1 immunogen, RemuneTM) in seropositive subjects. Viral Immunol. 1997;10(4):221–228. doi: 10.1089/vim.1997.10.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pal R, Garzino-Demo A, Markham P D, Burns J, Brown M, Gallo R C, DeVico A L. Inhibition of HIV-1 infection by the β-chemokine MDC. Science. 1997;278:695–698. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5338.695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pontesilli O, Carlesimo M, Varani A R, Ferrara R, D’Offizi G, Aiuti F. In vitro lymphocyte proliferative response to HIV-1 p24 is associated with a lack of CD4+ decline. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1994;10:113–114. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Reddy M M, Englard A, Brown D, Buimovici-Klien E, Grieco M H. Lymphoproliferative responses to human immunodeficiency virus antigen in asymptomatic intravenous drug abusers and in patients with lymphadenopathy or AIDS. J Infect Dis. 1987;156:374–376. doi: 10.1093/infdis/156.2.374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Revets H, Marissens D, de Wit S, Lacor P, Clumeck N, Lauwers S, Zissis G. Comparative evaluation of NASBA HIV-1 RNA QT, AMPLICOR-HIV Monitor, and QUANTIPLEX HIV RNA assay, three methods for quantification of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 RNA in plasma. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1058–1064. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1058-1064.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rosenberg E-S, Billingsley J M, Caliendo A M, Boswell S L, Sax P E, Kalams S A, Walker B D. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses associated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–1450. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5342.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnittman S M, Fox L. Preliminary evidence for partial restoration of immune function in HIV type 1 infection with potent antiretroviral therapies: clues from the Fourth Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Diseases. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 1997;13:815–818. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ullum H, Lepri A C, Victor J, Aladdin H, Phillips A N, Gerstoft J, Skinhøj P, Pedersen B K. Production of β-chemokines in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: evidence that high levels of macrophage inflammatory protein-1β are associated with a decreased risk of HIV disease progression. J Infect Dis. 1998;177:331–336. doi: 10.1086/514192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wahren B, Morfeldt-Mansson L, Biberfeld G, Moberg L, Sonnerborg A, Ljungman P, Werner A, Kurth R, Gallo R, Bolognesi D. Characteristics of the specific cell-mediated immune response in human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1987;61:2017–2023. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.6.2017-2023.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zarling J M, Eichberg J W, Moran P A, McClure J, Sridhar P, Hu S-L. Proliferative and cytotoxic T cells to AIDS virus glycoproteins in chimpanzees immunized with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing AIDS virus envelope glycoproteins. J Immunol. 1987;139:988–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]