Abstract

In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada outlined 94 Calls to Action, which formalized a responsibility for all people and institutions in Canada to confront and craft paths to remedy the legacy of the country’s colonial past. Among other things, these Calls to Action challenge medical schools to examine and improve existing strategies and capacities for improving Indigenous health outcomes within the areas of education, research, and clinical service. This article outlines efforts by stakeholders at one medical school to mobilize their institution to address the TRC’s Calls to Action via the Indigenous Health Dialogue (IHD). The IHD used a critical collaborative consensus-building process, which employed decolonizing, antiracist, and Indigenous methodologies, offering insights for academic and nonacademic entities alike on how they might begin to address the TRC’s Calls to Action. Through this process, a critical reflective framework of domains, reconciliatory themes, truths, and action themes was developed, which highlights key areas in which to develop Indigenous health within the medical school to address health inequities faced by Indigenous peoples in Canada. Education, research, and health service innovation were identified as domains of responsibility, while recognizing Indigenous health as a distinct discipline and promoting and supporting Indigenous inclusion were identified as domains within leadership in transformation. Insights are provided for the medical school, including that dispossession from land lays at the heart of Indigenous health inequities, requiring decolonizing approaches to population health, and that Indigenous health is a discipline of its own, requiring a specific knowledge base, skills, and resources for overcoming inequities.

Stemming from the historical and ongoing impacts of colonization, Indigenous peoples in Canada continue to experience widespread health inequities.1,2 As they exist today, systems of health care function as drivers of ill health in that they exacerbate poor health outcomes, enable health inequities, and erode Indigenous cultural identities through culturally unsafe environments.3,4 In 2015, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) of Canada outlined 94 Calls to Action, which formalized a responsibility for all people and institutions in Canada to confront and craft paths to remedy the legacy of the country’s colonial past.5,6 Seven of these Calls to Action (#18–24) challenge medical schools to examine and improve existing strategies and capacities for improving Indigenous health outcomes within the areas of education, research, and clinical service.

Considering their close proximity to the outcomes of population health inequities, medical schools are well positioned to work toward equity by acknowledging the “history and legacy of residential schools” as per the TRC’s Calls to Action6 and to recognize the impact of colonization on Indigenous peoples as outlined by the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.7 Social accountability in Canadian medical schools is guided by a number of national organizations, including the Association of Faculties of Medicine of Canada, Canadian Medical Association, Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada, College of Family Physicians of Canada, Indigenous Physicians Association of Canada, Association of American Medical Colleges, and Medical Council of Canada, all of which guide practices related to Indigenous health and promote competency development among trainees. Additionally, within the province of Alberta, where the work described in this article was undertaken, the Alberta Medical Association; Alberta Health Services; Alberta Health Services Indigenous Health Program; First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of the Alberta Region of Indigenous Services Canada; and governing members of Alberta Treaties 6, 7, and 8, as well as the Métis Nation of Alberta, all inform Indigenous health education and practices. Key directives crosscutting these entities advocate for promoting the authentic inclusion of Indigenous peoples and knowledge systems in health services and for building institutional capacity to address the underlying causes of health inequities arising from colonization.8

Recognizing the long-standing impacts of colonization and the need for institutional transformation, the majority of the 17 medical schools across Canada have begun to address their Indigenous health capacity through specific policies, curricular programming, and other Indigenous health initiatives. At the University of Calgary’s Cumming School of Medicine (CSM), Indigenous health-focused research, health service innovations, and educational initiatives have existed over the years but were often not formally interconnected with each other or linked with CSM leadership. In an effort to bridge these gaps, the Indigenous Health Dialogue (IHD) program began in 2015 to actively explore what the TRC’s Calls to Action may mean for the institution and its community partnerships in terms of building faculty and community capacity for aligning goals and outcomes. This article details the decolonizing, antiracist, and Indigenous methodologies employed early on by the IHD, and then discusses key areas of development within the CSM that have begun addressing Indigenous health inequities across Canada. A synthesis of reconciliatory themes, truths, and action themes are described to offer insights for how academic and nonacademic entities alike might begin to address the TRC’s Calls to Action.

Exploration

Between 2016 and 2019, the IHD employed a multiphased approach to engage internal and external stakeholder voices on Indigenous health priorities for the CSM and to harness strategies focused on knowledge building, knowledge exchange, and community engagement. As a first step, the IHD convened a TRC response working group in the spring of 2016 to explore and engage with the TRC’s Calls to Action and devised a critical collaborative consensus-building (CCCB) process (see Figure 1) grounded in an Indigenous, antiracist, and decolonizing pedagogy. This TRC response working group was composed of 6 self-selected members of the IHD concerned that the school had yet to formally respond to the TRC’s Calls to Action and who strategically represented perspectives from leadership, Indigenous faculty, trainees in Indigenous health research, and trainees in medical education.

Figure 1.

The critical collaborative consensus-building process used to develop the critical reflective framework, Indigenous Health Dialogue’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission working group, Cumming School of Medicine, University of Calgary, September 2015–July 2019. Abbreviation: TRCC, Truth and Reconciliation Commission Call to Action.

The CCCB process began with a series of 8 weekly 2-hour meetings in which all participants from the TRC response working group systematically reflected on their role and situation within structural, social, political, cultural, and economic contexts and what this meant in relation to their ability to contribute to building insights around actions the medical school could take to address the Calls to Action. From these discussions, a preliminary critical reflective framework of reconciliatory themes and truths was developed (see Chart 1). Following this, directions the medical school could take to address the Calls to Action were identified through both open discussions and Talking Circles, during which the TRC response working group examined Calls to Action #18–24 and focused on the following questions:

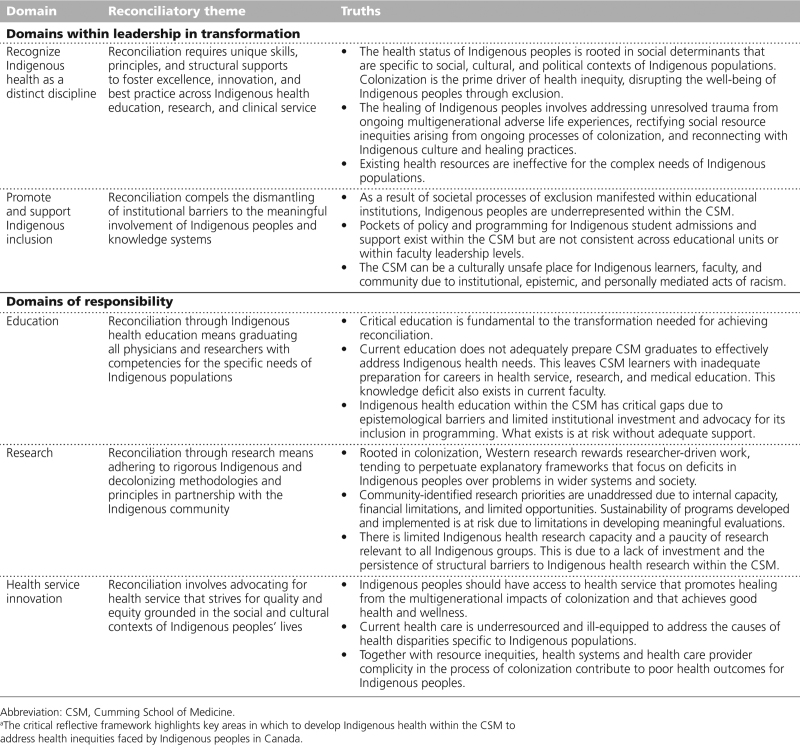

Chart 1.

Preliminary Critical Reflective Framework of Domains, Reconciliatory Themes, and Truths Developed From the Indigenous Health Dialogue’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission Response Working Group’s Discussions, CSM, University of Calgary, September 2015–July 2019a

What could medical schools do to address these Calls to Action?

How does each Call to Action apply to medical schools generally and any medical school specifically?

What can be done to shift medical education and research to be better positioned to address these Calls to Action?

Who at our institutions could contribute to the task of responding to the Calls to Action?

The following format was employed for discussions: (1) interpretation of the Call to Action within the context of a medical school through open discussion; (2) identification of main and secondary directions to address the Calls to Action for the CSM within the domains of global response, research, education, clinical services, and leadership through a Talking Circle; (3) exploration and clarification of emerging concepts through an open discussion; and (4) summative statements of directions for the CSM to take through a Talking Circle. Talking Circles were purposefully chosen as to not privilege one worldview over another and to promote a nonhierarchical structure by discouraging interruptions and allowing each person involved to share their perspectives.9

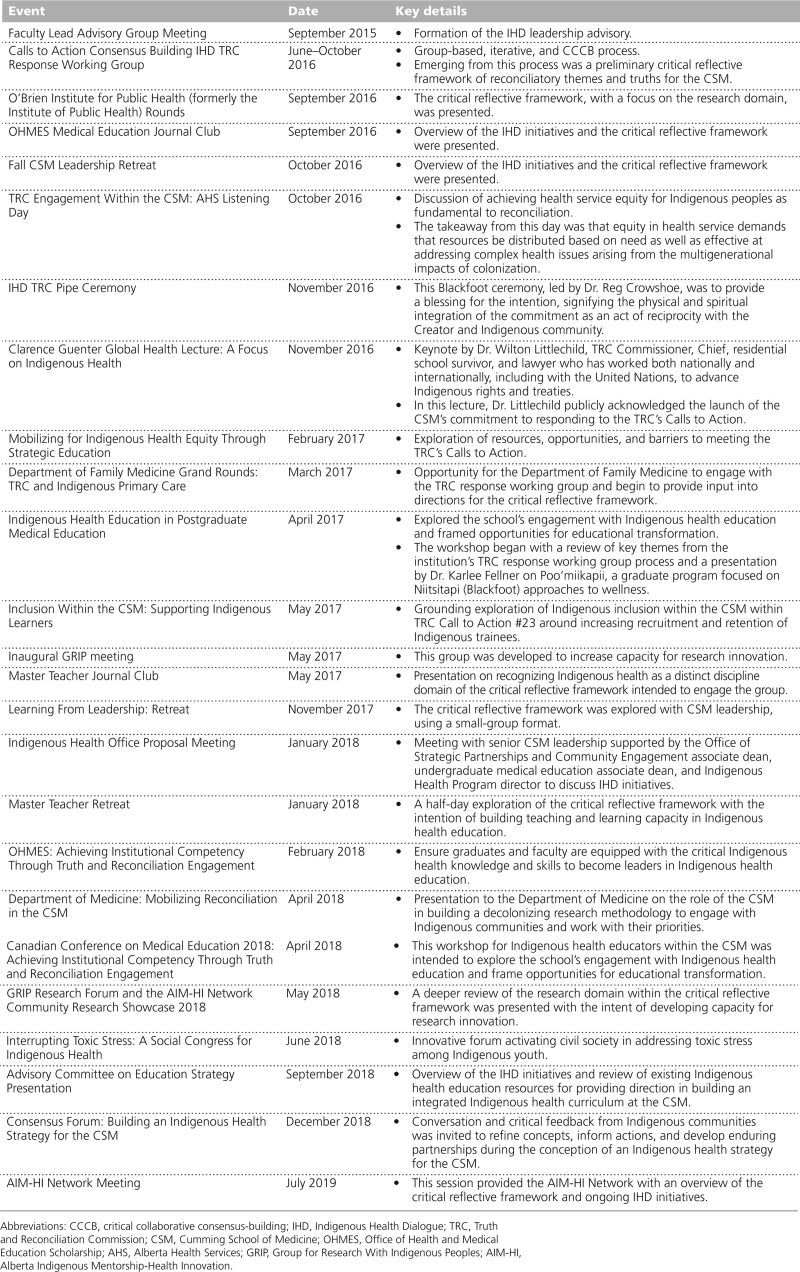

Using the preliminary critical reflective framework developed through the TRC response working group, the IHD convened over 25 internal and external engagement events with key stakeholders over the course of 3 years, each 1–3 hours long. This engaged approximately 500 people in sharing reflections on the evolving framework, including CSM leadership, faculty and staff, health system leadership, Chiefs, Elders, Indigenous community members, researchers, physicians, other health professionals, and CSM graduate and undergraduate students. Many meetings focused on specific subcomponents of the framework (e.g., action themes), sometimes even via embedding the engagement event within the standing meetings of distinct units within the school. Focusing on subcomponents of the framework enhanced engagement without taxing the time and attention of those supporting the work, allowing for discussions to be targeted to the areas of most relevance to those offering their insights. In 2018, the IHD’s focus was directed outside to the medical school, with members of the IHD engaging over 1,000 people through various provincial- and national-level presentations. See Table 1 for a summary of both the internal and external engagement events.

Table 1.

Description of Key Stakeholder Engagement Events Held as Part of the CCCB Process to Develop the Critical Reflective Framework for Addressing Health Inequities Faced by Indigenous Peoples in Canada, IHD’s TRC Response Working Group, CSM, University of Calgary, September 2015–July 2019

Critical feedback from these events was tracked and summarized to integrate within the critical reflective framework, connecting truths with action themes specific to the CSM, which identified what reconciliatory actions might feasibly look like (see Chart 2).

Chart 2.

Final Critical Reflective Framework Outlining Reconciliatory Themes, Truths, and Action Themes for the Medical School, Indigenous Health Dialogue’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission Response Working Group, CSM, University of Calgary, September 2015–July 2019a

Findings

The critical reflective framework highlights key areas in which to develop Indigenous health within the CSM to address health inequities faced by Indigenous peoples in Canada. Education, research, and health service innovation were identified as domains of responsibility, while recognizing Indigenous health as a distinct discipline and promoting and supporting Indigenous inclusion in the CSM were identified as domains within leadership in transformation. Each of these domains, which are a synthesis of a 3-year iterative dialogue that began with the TRC response working group and were extended by the IHD to internal stakeholders and, eventually, external stakeholders and communities served by the medical school, are discussed below.

Domains of responsibility

Education.

Medical schools are often underresourced, which results in Indigenous health education initiatives not being strategically positioned to advance and support educational impacts across learning domains.10 Combined with a lack of Indigenous peoples and perspectives within all domains of the medical school, Indigenous health curricula are often difficult to build and sustain. While the TRC Calls to Action #23 and #24 focus on increasing the number of Indigenous health care professionals and emphasize the need for Indigenous health training, medical schools remain limited in their ability to do so without supportive infrastructure and connections. Medical schools must address institutional barriers that limit the prioritization of Indigenous health education and further invest in sustaining innovative and comprehensive Indigenous health education to decolonize their institutions and promote equity.

Research.

Medical schools provide limited Indigenous health research capacity and an overall paucity of research relevant to Indigenous groups due to a lack of investment coupled with the persistence of structural barriers. Furthermore, Western research rooted in colonial knowledge practices tends to perpetuate explanatory frameworks focused on deficits within Indigenous peoples (i.e., blaming health inequities on personal choices over structural inequities). There is a pressing need to recenter research within the communities being served—medical research should focus on community priorities, yet academic goals are often at odds with the interests of those most affected by health inequities. Through increased strategic planning, including the recruitment and retention of Indigenous students, staff, and faculty, the conflict between medical schools and Indigenous communities can be alleviated. If medical schools are to advance toward decolonization, they must build capacity for Indigenous health research through respectful partnerships with Indigenous communities and provide a platform for Indigenous health research based on decolonizing methodologies.

Health service innovation.

Crosscutting education, research, and leadership, health service innovation occupies a unique position in any transformative agenda. Promoting greater research exchange between institutions is critical to catalogue the resources and individuals that are available to mobilize health services. Quality and equity within Indigenous health services depends on advocacy around the social and cultural contexts of Indigenous peoples’ lives. Health service innovation is a means to recognize Indigenous worldviews and Indigenous community directives (e.g., cultural safety), which cannot be achieved solely by increasing the number of positions held by Indigenous peoples within an institution. Facilitating health service innovations through both collaboration and research and further advocating for collaborations with key health systems stakeholders is a means to promote equity within medical schools.

Domains within leadership in transformation

Promote and support Indigenous inclusion.

Greater inclusion of Indigenous peoples is needed in all domains of medical schools to increase recruitment and retention as outlined by the TRC’s Calls to Action. Indigenous peoples face unique struggles in their interactions with both non-Indigenous peers and wider health systems. Indigenous students feel burdened to teach their non-Indigenous peers about their histories and realities and to justify their research grounded in Indigenous epistemologies to their professors. Similar issues are seen across different groups within the CSM, including staff, faculty, and leadership, whereby Indigenous peoples feel disconnected and limited in the inclusion of their ideas, experiences, and perspectives. To promote Indigenous inclusion, medical schools need a strategy to buffer these interactions. There are 2 ways to do this: firstly, a formal institutional decolonization process should be undertaken to dismantle the barriers faced by Indigenous peoples, and secondly, foundational strategies for the authentic inclusion of Indigenous peoples across all levels of institutions should be invested in. Furthermore, Indigenous inclusion goes beyond just Indigenous peoples and should also include Indigenous ways of knowing, being, doing, and connecting.11,12 Valuing Indigenous knowledge systems within medical schools is a means to channel this change.

Recognizing Indigenous health as a distinct discipline.

Fundamental to achieving health equity and self-determination is fostering Indigenous health as its own discipline. Critical investment is needed to grow capacity in medical schools for equity and to further promote Indigenous-based approaches that require a shared knowledge base that crosscuts teaching, research, and health service innovation in much the same way as this would be needed in any other medical subspecialty. Like other medical schools, the CSM has both a role and responsibility for social accountability through advocacy, engagement, and knowledge exchange with Indigenous communities and non-Indigenous stakeholders. A focus on building Indigenous health as its own discipline requires the nurturing of institutional expertise and innovations through collaborations and leveraging resources. When something exists as its own discipline, practitioners are better resourced to set priorities and advance shared goals together. When it is not, practitioners are often left disconnected and not rewarded for collaborating, instead, they often end up at the margins of various units or entities within an institution without sufficient support to be transformative. Developing critical linkages and sustaining engagement with Indigenous communities are key to achieving Indigenous health equity.

Implications and Future Directions

Indigenous health is a vast and distinct discipline requiring training, research, and health service innovation, as well as a common set of resources to define and build competencies. Reliable and consistent funding is a means to grow and further develop Indigenous health as a distinct discipline rather than relegating it to the peripheries of other disciplines, leaving it haphazard or opportunistic and undercutting the transformative ask of the TRC’s Calls to Action. Insights are provided for the CSM, including that dispossession from land lays at the heart of Indigenous health inequities, requiring decolonizing approaches to population health, and that Indigenous health is a discipline of its own, requiring a specific knowledge base, skills, and resources for overcoming inequities. Decolonizing approaches can be seen as a solution to address the legacy of colonialism and can serve to dismantle colonialism as the “dominant model on which society operates.”13–16

It should be noted that when Indigenous health is treated as a special interest topic, there is a risk of advancing a hidden agenda that it is not truly a part of the core medical education curriculum for trainees but rather an area of expertise for those who will be working more closely with Indigenous communities. This is problematic because Indigenous peoples access health care across all of the available points of contact with the health care system. To address the TRC’s Calls to Action, the advancement of Indigenous health needs to be supported in its entirety by the CSM’s structures and directives issued by CSM leadership.

Finally, there is much progress to be made in building capacity among individuals within medical schools to advance Indigenous health equity. The presence of deep relationships among its members has allowed the IHD to be more adaptive, an approach required to advance decolonization. It is essential to build a cohort of leaders who will guide the CSM in how to orient itself to address the institutional barriers to advancing Indigenous health equity through rigorous decolonizing methodologies, while providing a platform for Indigenous health research.

In terms of recognizing Indigenous health as a distinct discipline, since the IHD began, the CSM has refashioned its Office of Strategic Partnerships and Community Engagement into the Indigenous, Local and Global Health Office, with a clearer mandate for Indigenous health, as well as a dedicated space for ceremonial activities and gatherings. The Indigenous, Local and Global Health Office has become the focal point for Indigenous leadership roles, providing a cohesive unit for Indigenous health, and has provided a common point of connection for Indigenous initiatives within the CSM. At the CSM, further supportive infrastructure has been developing as well, including the hiring of an Indigenous dean, the development of a mural and ceremonial space at the campus, and a growing number of Indigenous health champions. A multiyear renewable network grant from the Canadian Institutes for Health Research to form the Indigenous Primary Health Care and Policy and Research Network dedicated to innovation in health service, research, and education17 has expanded the CSM’s capacity for sustaining community and health system relationships with Indigenous decision-makers and health care professionals. While the novel infrastructure outlined here provides hope and reassurance that the TRC’s Calls to Action are being pursued, the IHD critical reflective framework has also allowed for the observation and remediation of ongoing issues, such as decisions related to Indigenous health being made without meaningful connection with Indigenous leaders and/or Indigenous faculty. Another area the CSM is working on is ensuring that staff and leaders within the admission office are equipped to assess Indigenous student applications, including ensuring that they have the capacity to discern what constitutes appropriate documentation, including documentation pertaining to First Nations, Métis, or Inuit status.

Strengths and limitations

A strength of this work is that there was no mandate to create the IHD—this work began with a group of people who were both concerned and invested in decolonizing the medical school and advancing Indigenous health equity. As the first year anniversary of the release of the TRC’s Calls to Action approached, this small group of colleagues working in Indigenous health education, health service, and research began to recognize that institutional awakening to the task of contextualizing the TRC’s Calls to Action to medical schools was unlikely to occur without the advocacy and encouragement of those working most closely in this area. In the absence of wider institutional investment in addressing the TRC’s Calls to Action, this group came together with the intention of making sense of what could be done to stir action and, in this fashion, came to define the CCCB process outlined here. Another strength is in the process—a thorough grounding was developed that aligned with Indigenous principles of doing and knowing in research and innovation. One limitation of the IHD critical reflective framework is that the funding obtained to advance it and the IHD in general was opportunistic and therefore not stable; thus, the advancement of the framework and other IHD initiatives occurred intermittently. Lastly, another limitation is that the majority of key players who advanced the IHD critical reflective framework were already marginalized people either as Indigenous academics or as non-Indigenous people in early-career roles and so were both vulnerable and limited in their advocacy roles.

Conclusions

The action themes outlined in the IHD critical reflective framework contextualize and ground Indigenous peoples’ health within the context of the CSM to fulfill mandates that medical schools be socially accountable. This framework also aligns with Indigenous protocols for sovereignty, mutual respect, and ethical spaces toward decolonization and equity. Such work nevertheless comes with the risk of dissipating without a cohesive and well-resourced strategy within the institution. A long-term working group is envisioned to define and advocate for the implementation of the described action themes. The strides the CSM has achieved in recent years are measurable with new faculty hires, dean appointments, and the addition of a ceremonial space within the school for gathering and growing.

Acknowledgments:

The authors would like to acknowledge the entire Cumming School of Medicine and all the individuals too numerous to list who have deeply engaged with this process and its various iterative states. The authors extend their gratitude to the people who participated in internal and external engagement sessions, the Cumming School of Medicine’s Indigenous, Local and Global Health Office (formerly Office of Strategic Partnerships and Community Engagement), and the O’Brien Institute for Public Health for their ongoing support of the work described in this article.

Footnotes

Funding/Support: The authors would like to acknowledge the University of Calgary’s Indigenous Strategy, ii’taa’poh’to’p, for financially supporting engagement gatherings; the Canadian Institutes for Health Research for funding a postdoctoral fellowship on the social accountability of medical schools to Indigenous health; and the United Way, the University of Calgary’s Office of Indigenous Engagement, and the Cumming School of Medicine’s Indigenous, Local and Global Health Office for their financial support of the work described in this article.

Other disclosures: None reported.

Ethical approval: This study was approved by the Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board at the University of Calgary (REB17-1160).

Contributor Information

Rita Henderson, Email: rihender@ucalgary.ca.

Cheryl Barnabe, Email: ccbarnab@ucalgary.ca.

Pamela Roach, Email: pamela.roach@ucalgary.ca.

Lindsay (Lynden) Crowshoe, Email: crowshoe@ucalgary.ca.

References

- 1.Kim PJ. Social determinants of health inequities in Indigenous Canadians through a life course approach to colonialism and the residential school system. Health Equity. 2019;3:378–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Czyzewski K. Colonialism as a broader social determinant of health. Int Indigenous Policy J. 2011;2:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Matthews R. The cultural erosion of Indigenous people in health care. CMAJ. 2017;189:E78–E79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Richmond CA, Cook C. Creating conditions for Canadian Aboriginal health equity: The promise of healthy public policy. Public Health Rev. 2016;37:1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future: Summary of the Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. https://publications.gc.ca/collections/collection_2015/trc/IR4-7-2015-eng.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- 6.Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Calls to Action. https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Calls_to_Action_English2.pdf. Published 2015. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- 7.United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2018/11/UNDRIP_E_web.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed March 6, 2023.

- 8.Williams K, Potestio ML, Austen-Wiebe V; Population, Public & Indigenous Health Strategic Clinical Network. Population, Public & Indigenous Health Strategic Clinical Network. Indigenous health: Applying truth and reconciliation in Alberta health services. CMAJ. 2019;191(suppl 1):S44–S46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brown MA, Di Lallo S. Talking Circles: A culturally responsive evaluation practice. Am J Eval. 2020;41:367–383. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bleakley A. The perils and rewards of critical consciousness raising in medical education. Acad Med. 2017;92:289–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martin K, Mirraboopa B. Ways of knowing, being and doing: A theoretical framework and methods for Indigenous and Indigenist re‐search. J Aust Stud. 2003;27:203–214. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown HJ, McPherson G, Peterson R, Newman V, Cranmer B. Our land, our language: Connecting dispossession and health equity in an Indigenous context. Can J Nurs Res. 2012;44:44–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Smith LT. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wheeler W, ed. For Indigenous Eyes Only: A Decolonization Handbook. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 15.McCaslin WD, Breton DC. Justice as healing: Going outside the colonizer’s cage. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS, Smith LT, eds. Handbook of Critical and Indigenous Methodologies. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publishing; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mundel E, Chapman GE. A decolonizing approach to health promotion in Canada: The case of the Urban Aboriginal Community Kitchen Garden Project. Health Promotion Int. 2010;25:166–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Crowshoe LL, Sehgal A, Montesanti S, et al. The Indigenous Primary Health Care and Policy Research Network: Guiding innovation within primary health care with Indigenous peoples in Alberta. Health Policy. 2021;125:725–731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]