Abstract

All cancers can increase the risk of developing venous thromboembolism (VTE), and anticoagulants should be considered as an optimal treatment for patients suffering from cancer-associated VTE. However, there is still a debate about whether the new oral anticoagulant, rivaroxaban, can bring better efficacy and safety outcomes globally. Thus, this systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban. We searched PubMed, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Web of Science, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure for relevant published papers before 1 September 2019, with no language restrictions. The primary outcomes are defined as the recurrence of VTE. The secondary outcomes are defined as clinically relevant non-major bleeding, adverse major bleeding events, and all-cause of death. The data were analyzed by Stata with risk ratio (RR) and 95% confidence interval (CI). Four trials encompassing 1996 patients were included. Rivaroxaban reduced recurrent VTE with no significant difference (RR = 0.68, 95% CI = 0.43–1.07). Similarly, there were no significant differences in adverse major bleeding events (RR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.37–2.00), clinically relevant non-major bleeding (RR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.73–2.12) and all-cause mortality (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.40–1.44). In a selected study population of cancer patients with VTE, rivaroxaban is as good as other anticoagulants. Further, carefully designed randomized controlled trials should be performed to confirm these results.

Keywords: Cancer, venous thromboembolism, anticoagulant, rivaroxaban, meta

Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is caused by blood clotting irregularly in veins, which leads to higher morbidity, mortality, and increased financial burden in patients. 1 All cancers can increase developing VTE risk, especially if cancer has metastasized, and thromboembolism is currently the second leading cause of death among cancer patients. Cancer-associated VTE is a life-threatening and prevalently exist complication in cancer patients, 2 with its higher morbidity and mortality in clinical works, 3 and the complexity of prevention and treatment donated by a much higher risk of adverse events, such as recurrent VTE and major bleeding, in cancer patients than others.4,5 Various drugs are used to prevent deep vein thrombosis from forming or dissolve clots, and they are the main treatments for VTE in addition to catheter-assisted thrombus removal and vena cava filter, including blood thinners, or anticoagulants, and thrombolytics.

The management of anticoagulant therapy for the treatment of VTE in patients either who is highly suspected of having cancer or has been confirmed a diagnosis of cancer has become a prevalent concern among physicians and relevant patients since physicians should consider the risk of major bleeding, the type of cancer, and the potential interactions between drug and drug in addition to the patient who knows his condition clearly preference in deciding the most beneficial treatment formula.4,6 The National Comprehensive Cancer Network Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology for Cancer-Associated VTE point out treatment formulas to prevent and treat cancer-associated VTE, but it does not directly outline which drug can bring greater benefits. 7 Recently published Hokusai trial (NCT02073682) 8 confirmed that we have no evidence to prove the dalteparin is better than oral edoxaban concerning the composite ending events of recurrent VTE or major bleeding. Rivaroxaban is another new oral anticoagulant. 9 Although the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) confirmed rivaroxaban has the same curative effect as other anticoagulants in the VTE treatment proved clinical trials through its patients are not fully with cancer,10–13 subgroup analysis for cancer patients has been performed based on existing vital important clinical trials, 14 and some RCTs exclusively for cancer patients are being implemented. 15 In terms of the above results, the safety and efficacy of rivaroxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated VTE remain contentious, thus, we conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to evaluate the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in the treatment of cancer-associated thromboembolism and to provide evidence-based solutions for clinicians and patients.

Material and methods

Study protocol

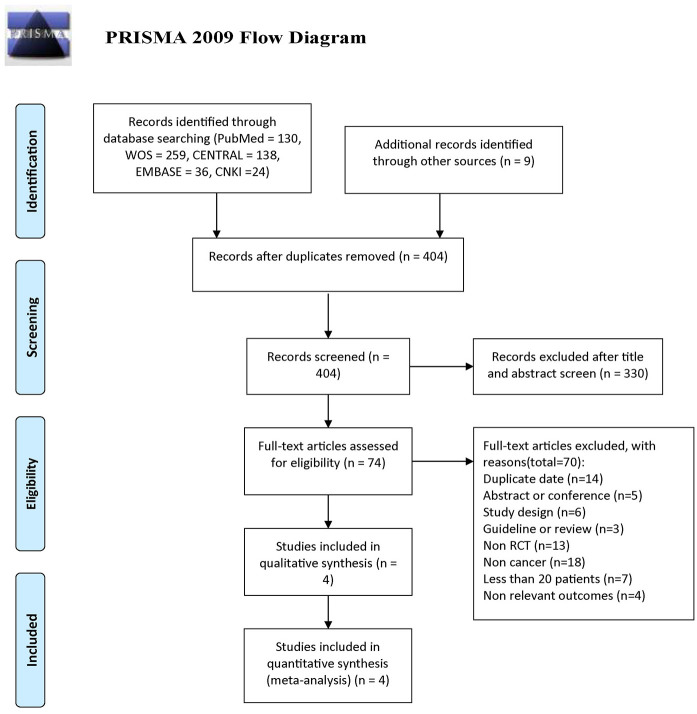

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. We developed a protocol and registered on PROSPERO (CRD42019143265). Ethical approval and patient consent are not required as this study is based on published studies.

Search strategy and selection criteria

Two reviewers searched PubMed, Web of Science, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, Embase, and China National Knowledge Infrastructure for relevant published studies before 1 September 2019, without any language restrictions, and the search strategies in different databases were shown in Supplemental Table S1. The subject terms and keywords corresponding to Medical Subject Heading terms were used to search for eligible studies in the databases as mentioned above. Besides, relevant references of prior systematic reviews or meta-analyses were also screened for eligible studies, records collected in this way were defined as additional records identified through other sources. Only RCTs were included, observational studies, registry data, ongoing trials without results, editorials, case series, and duplicate studies were excluded.

Eligibility criteria for studies to be included in this study were described previously. 16 Briefly, the participants diagnosed with cancer-associated VTE were included, regardless of the type of cancer, stage, or gender. All anticoagulants for participants were studied. After all duplicates were removed, two reviewers independently screened each title and abstract, and then the full text was rescreened for those potentially eligible. In addition, a third author made final decisions in controversial judgments. The fourth reviewer oversaw the entire study’s screening and selection process to ensure completeness and accuracy.

Study outcomes

The primary outcomes were defined as recurrent VTE, comprising all deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. The secondary outcomes were defined as adverse major bleeding events, clinically relevant non-major bleeding, and all-cause of death.

Data extraction and quality assessment

One reviewer extracted the following data from the eligible studies: the information of study characteristics, demographic characteristics, interventions as well as outcomes. Then another two reviewers checked the received data. After that, quality assessment 17 of included studies was applied by two reviewers independently. The final author made final decisions in contradictory cases. Finally, all the extracted data will be stored in the predesigned excel spreadsheet.

Data synthesis and analysis

The Stata 12.0 was adopted to synthesize and analyze data. Effect sizes were calculated with the fixed-effects estimator and expressed as risk ratios (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Heterogeneity was assessed by Q and I2 tests. A value of I2 of 0%–25% represents insignificant heterogeneity, 26%–50% low heterogeneity, 51%–75% moderate heterogeneity, and >75% high heterogeneity. 18 Sensitivity analyses were performed to investigate the robustness of our results to assess whether any of the included studies had a large influence on the results.

Results

Search results and study details

A total of 596 studies were screened for eligibility. After we screened by topics and abstracts, very few clinical randomized controlled studies met our inclusion criteria in the remaining studies. Finally, four RCTs (EINSTEIN (NCT00440193 and NCT00439777), 14 SELECT-D, 15 XALIA (NCT01619007), 19 and Yang 20 ) were identified, 1996 patients (rivaroxaban group = 876 and control group = 1120) in cancer patients with VTE were included in the final analysis (Figure 1). The MAGELLAN trial (NCT00571649) 21 was excluded, although it has a large number of VTE patients who have a history of cancer, but we failed to obtain the original data of the patients with cancers. CASSINI (NCT02555878) 22 was also excluded due to thromboprophylaxis. We simplified the group of EINSTEIN and XALIA for subsequent analysis. In EINSTEIN, cancer in medical history only group and active cancer at baseline group were grouped together; while early switchers group (rivaroxaban after heparin or fondaparinux for > 48 h to 14 days and/or a vitamin K antagonist for 1–14 days), standard anticoagulation group (heparin or fondaparinux and a vitamin K antagonist), LMWH group and miscellaneous group (other heparins, fondaparinux alone, vitamin K antagonist alone) were collectively referred as others in XALIA.

Figure 1.

The flow diagram for study selection.

The dosage and approach of rivaroxaban and controls were shown in Table 1. According to the four studies, Rivaroxaban therapy started at the time of randomization, which occurred from the discovery of VTE in the cancer patient up until at least 6 months. In the control group, vitamin K antagonists and low molecular weight heparin was the most frequently used regimen. Enoxaparin was adopted in EINSTEIN, dalteparin was adopted in SELECT-D, vitamin K antagonists, low molecular weight heparin, and fondaparinux were adopted in XALIA, and low molecular weight heparin was adopted in Yang (Table 1). The duration of follow-up ranged from 3 to 24 months. The characteristics of the four included trials were reported in Table 2.

Table 1.

The dosage and approach of drugs.

| Study | EINSTEIN 14 | SELECT-D 15 | XALIA 19 | Yang 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 2014 | 2018 | 2017 | 2019 |

| Center | multicenter | multicenter | multicenter | singlecenter |

| Follow-up | >180 d | 24 m | >3 m | 6 m |

| Patients | 491/440 | 203/203 | 146/441 | 36/36 |

| Male | 272/232 | 116/98 | 76/218 | 19/20 |

| Cancers | ||||

| Genitourinary tract | 157/137 | 25/17 | 38/137 | 0/1 |

| Gastrointestinal | 65/52 | 91/86 | 20/96 | 3/7 |

| Breast | 67/71 | 20/20 | 32/82 | 5/4 |

| Haematological | 52/37 | 14/17 | 12/38 | 2/1 |

| Lung | 24/16 | 22/25 | 5/39 | 9/6 |

| Skin | 67/70 | 2/0 | 6/12 | NA |

| CNS brain | 4/4 | 1/2 | 5/11 | NA |

| Gynecologic | NA | 18/25 | NA | 17/15 |

| Combinations | 25/30 | NA | NA | NA |

| Others | 30/23 | 10/11 | 36/56 | 0/2 |

| Recurrent VTE | 11/13 | 8/18 | 5/19 | 4/3 |

| Adverse bleeding events | 6/12 | 11/6 | 2/17 | 0/0 |

| Clinically relevant bleeding | 55/49 | 25/7 | 67/244 | 5/3 |

| All-cause mortality | 43/40 | 33/28 | 7/68 | NA |

| Net clinical benefit | 21/28 | NA | NA | NA |

| Safety population | 488/438 | NA | NA | NA |

NA: not applicable.

Genitourinary tract (including bladder or Prostate); Skin (including squamous-cell or basal-cell carcinoma); Gynecologic (including ovarian)

Table 2.

The characteristics of the four included trials.

| Study | EINSTEIN 14 | SELECT-D 15 | XALIA 19 | Yang 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rivaroxaban | 15 mg twice daily for 21 days, followed by 20 mg once daily | 15 mg twice daily for 3 weeks, then 20 mg once daily for a total of 6 months | rivaroxaban alone or after heparin or fondaparinux for ≤48 h | 10 mg twice daily for 30 days, then adjusted for 60 days |

| Control | enoxaparin 1·0 mg/kg twice daily and warfarin or acenocoumarol; international normalized ratio 2·0–3·0 | dalteparin 200 IU/kg daily during month 1, then 150 IU/kg daily for months 2–6 | early switchers (rivaroxaban after heparin or fondaparinux for >48 h to 14 days and/or a VKA for 1–14 days); standard anticoagulation (heparin or fondaparinux and a VKA); LMWH alone; and miscellaneous (other heparins, fondaparinux alone, VKA alone). | LMWH 0.4 ml twice daily for 30 days, then adjusted dose for 60 days |

Efficacy endpoints

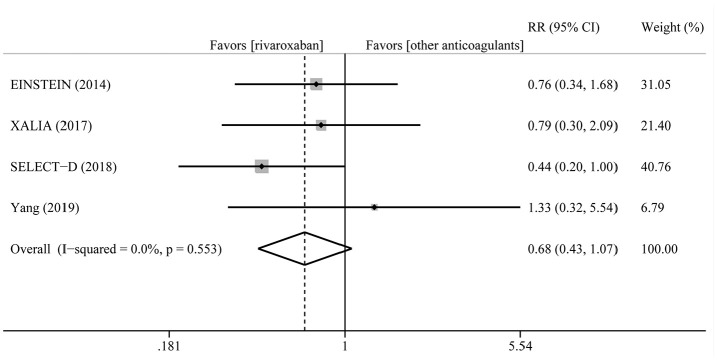

After follow-up (range 3–24 months), the incidence rate of recurrent VTE in patients treated with rivaroxaban varied from 2.2% to 11.1%, while 3.0% to 8.3% in other anticoagulants. The pooled incidence rate was 3.2% for rivaroxaban and 4.7% for other anticoagulants with pooled RR of 0.68 (95% CI = 0.43–1.07, p = 0.094). Moreover, there was no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%, PQ = 0.553) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Summary plot for recurrent VTE.

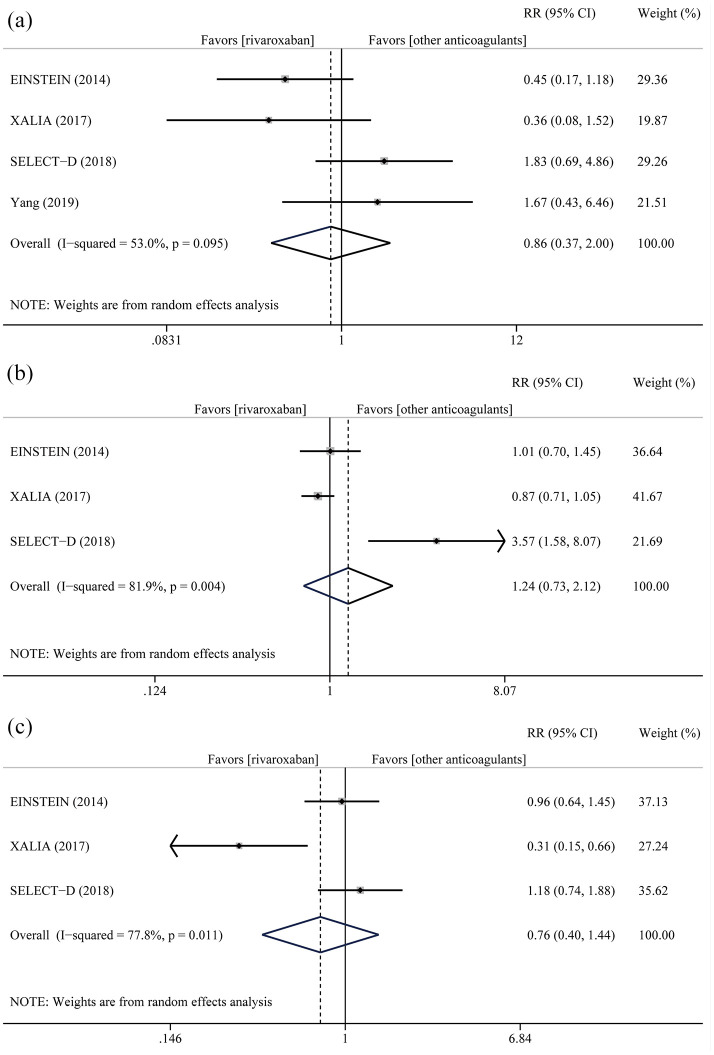

Safety endpoint

Adverse major bleeding events occurred in 62 patients (24 patients in rivaroxaban, 38 patients in others, respectively) and were not affected by anticoagulation strategy (RR = 0.86, 95% CI = 0.37–2.00) with mild heterogeneity (I2 = 53.0%, PQ = 0.095) (Figure 3(a)). With the exception of Yang, 20 clinically relevant non-major bleeding and all-cause of death were reported. Clinically relevant non-major bleeding was the most common adverse event, occurring in 568 patients. Rivaroxaban did not reduce the pooled events (RR = 1.24, 95% CI = 0.73–2.12, I2 = 81.9%, PQ = 0.004) (Figure 3(b)). During the follow-up, a total of 219 patients suffered from all-cause mortality, 83 in rivaroxaban group and 136 in control group. As expected, it was lower in the rivaroxaban group (RR = 0.76, 95% CI = 0.40–1.44, I2 = 77.8%, PQ = 0.011) with no statistical significance (Figure 3(c)).

Figure 3.

Summary plot for adverse major bleeding events (a), clinically relevant non-major bleeding (b), and all-cause mortality (c).

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed to evaluate individual study’s influence on the pooled results to verify the consistency of the meta-analysis consequences. The results disclosed that there had no significant heterogeneity in adverse major bleeding events (Supplemental Figure S1A). For clinically relevant non-major bleeding, when SELECT-D was omitted, the pooled results changed a lot (Supplemental Figure S1B). The main findings were also unchanged for all-cause mortality (Supplemental Figure S1C).

Publication bias

Moreover, due to the limited number of studies (less than 10), we are unable to detect potential publication bias and potential confounding factors that might affect outcomes. 23

Discussion

In the present systematic review and meta-analysis, we combined National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 7 Canadian, 4 and French 24 guidelines to broadly define VTE as deep venous thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, central venous catheter-related thrombosis, superficial vein thrombosis, and splanchnic vein thrombosis. 16 This study, which includes all studies to date, examined the role of rivaroxaban in 1996 patients with cancer-associated VTE. We found that rivaroxaban is as good as other anticoagulants in patients with cancer-associated VTE regarding recurrent VTE, adverse major bleeding events, clinically relevant non-major bleeding, and all-cause of death, besides, although with no statistical significance, it may reduce the all-cause of death and the recurrence of VTE.

There were some published studies evaluating new oral anticoagulants, including dabigatran, rivaroxaban, edoxaban, and apixaban, for patients with cancer-associated VTE.25–30 Most of them included both RCTs and prospective cohort studies and came to the conclusion that new oral anticoagulants seem to be as effective and safe as conventional treatment for the prevention of VTE in patients with cancer. Later, studies about specific oral anticoagulants, rivaroxaban, have also emerged. 31 It is concluded that incidences of recurrent VTE and major bleeding among rivaroxaban-managed patients are not dissimilar to those seen in recent randomized trials of anticoagulation in cancer-associated VTE, even though not only RCTs were included. Besides, a meta-analysis found rivaroxaban is as effective and safe as enoxaparin for the prevention of recurrent VTE in patients with malignancy. 32 When we selected studies, we found that many of them were retrospective,33–35 indicating selection bias. We all know that the quality of the included studies affects the results of the meta-analysis.36–38 Here, we only included RCTs, which are generally considered to be of high quality. Our study discovered rivaroxaban reduced recurrent VTE with no significant difference compared to other anticoagulants based on four RCTs.

However, this study still remains some limitations. Firstly, in our included EINSTEIN, SELECT-D, and XALIA trials, not all participants were cancer patients with VTE. In the EINSTEIN trials, only 5.5% of patients had active cancer at baseline. 14 We only extracted data from people who met our inclusion criteria in the current study. Researches about rivaroxaban in cancer with VTE are urgently needed. Secondly, the dosing of the four included trials are different, XALIA declared the dosing of rivaroxaban is maintained consistent with the EINSTEIN DVT phase 3 trial, it is to say, the dosing of rivaroxaban in EINSTEIN, SELECT-D, and XALIA are the same, but the dosing of rivaroxaban in the trial of Yang is different, it is maybe because this trial was conducted in China, and rivaroxaban adopted in this trial were produced by nexconn medicine, a local Pharmaceutical Factory, causing different dosing. Similar limitation can be found in the dosing of the control group, in the sensitivity analysis of clinically relevant bleeding, although the dosing of rivaroxaban is the same in the trial of SELECT-D and EINSTEIN, the removal of SELECT-D resulted in a strong deviation, after comparing with EINSTEIN, and we found the heterogeneity may origin from the control group of SELECT-D, owing to the mild dosage of dalteparin, while the ratio of clinically relevant bleeding is lower, 11.14% in EINSTEIN and 3.45% in SELECT-D, unfortunately, the ratio of VTE recurrence is higher. Besides, this is a study-level meta-analysis. Although the methodology is well-established and we applied strict criteria for study selection, it would be of paramount importance to confirm our findings with a patient-level meta-analysis. In particular, the availability of additional data and analyses with extended follow-up, duration more than 12 or even 24 months, would be helpful. In terms of the duration of follow-up, direct oral anticoagulants have been recommended for the treatment of VTE in cancer patients in recent years,5,7,39 but the duration of treatment is different. The duration of treatment recommended by National Comprehensive Cancer Network, 7 International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis, 39 and American college of chest physicians 5 is at least 6 months, 3–6 months, at least 3 months, respectively. However, limited to the small number of studies included, we were unable to conduct subgroup analysis to determine the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban.

Finally, we recognize that patients participating in RCTs are different from sicker patients seen in the clinical setting and further studies are needed to confirm similar outcomes in patients with a greater risk. Further, carefully designed RCTs in patients with cancer-associated VTE should be performed to confirm these results.

Conclusions

In a selected study population of cancer patients with VTE, rivaroxaban is as good as other anticoagulants, even though there was heterogeneity in the secondary outcomes. Further, carefully designed randomized controlled trials should be performed to confirm these results.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-sci-10.1177_00368504211012160 for Rivaroxaban for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism by Bo Liang, Yi Liang, Li-Zhi Zhao, Yu-Xiu Zhao and Ning Gu in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-sci-10.1177_00368504211012160 for Rivaroxaban for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism by Bo Liang, Yi Liang, Li-Zhi Zhao, Yu-Xiu Zhao and Ning Gu in Science Progress

Author biographies

Bo Liang, MD, is a Doctor of internal medicine of traditional Chinese medicine, Nanjing University of traditional Chinese Medicine.

Yi Liang, Postgraduate of internal medicine of traditional Chinese medicine, Southwest Medical University.

Li-Zhi Zhao, MD, Chief Physician of Hospital (T.C.M.) Affiliated to Southwest Medical University.

Yu-Xiu Zhao, MS, Nurse of Hospital (T.C.M.), Affiliated to Southwest Medical University.

Ning Gu, MD, Ph.D, Chief Physician of Nanjing Hospital of Chinese Medicine Affiliated to Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine.

Footnotes

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, or publication of this article: This work was funded by Jiangsu Leading Talent Project of Traditional Chinese Medicine (Jiangsu TCM 2018 No.4), and Jiangsu Universities Nursing Advantage Discipline Project (2019YSHL095).

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was not sought for the present study because this was a review article and did not involve any patients.

Informed consent: Informed consent was not sought for the present study because this was a review article and did not involve any subjects.

ORCID iDs: Bo Liang  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1749-6976

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1749-6976

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1.Weycker D, Li X, Wygant GD, et al. Effectiveness and safety of apixaban versus warfarin as outpatient treatment of venous thromboembolism in U.S. clinical practice. Thromb Haemost 2018; 118(11): 1951–1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khorana AA, Francis CW, Culakova E, et al. Thromboembolism in hospitalized neutropenic cancer patients. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24(3): 484–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Streiff MB, Holmstrom B, Ashrani A, et al. Cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease, version 1.2015. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2015; 13(9): 1079–1095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carrier M, Blais N, Crowther M, et al. Treatment algorithm in cancer-associated thrombosis: Canadian expert consensus. Curr Oncol 2018; 25(5): 329–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kearon C, Akl EA, Ornelas J, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for VTE disease: CHEST guideline and expert panel report. Chest 2016; 149(2): 315–352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabral KP. Pharmacology of the new target-specific oral anticoagulants. J Thromb Thrombolysis 2013; 36(2): 133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Streiff MB, Holmstrom B, Angelini D, et al. NCCN guidelines insights: cancer-associated venous thromboembolic disease, version 2.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2018; 16(11): 1289–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raskob GE, van Es N, Verhamme P, et al. Edoxaban for the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(7): 615–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Piccini JP, Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, et al. Rivaroxaban, an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor. Expert Opin on Investig Drugs 2008; 17(6): 925–937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.EINSTEIN Investigators, Bauersachs R, Berkowitz SD, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for symptomatic venous thromboembolism. N Engl J Med 2010; 363(26): 2499–2510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.EINSTEIN–PE Investigators, Büller HR, Prins MH, et al. Oral rivaroxaban for the treatment of symptomatic pulmonary embolism. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1287–1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Prins MH, Lensing AW. Derivation of the non-inferiority margin for the evaluation of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of venous thromboembolism. Thromb J 2013; 11(1): 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prins MH, Lensing AW, Bauersachs R, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus standard therapy for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism: a pooled analysis of the EINSTEIN-DVT and PE randomized studies. Thromb J 2013; 11(1): 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prins MH, Lensing AWA, Brighton TA, et al. Oral rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin with vitamin K antagonist for the treatment of symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer (EINSTEIN-DVT and EINSTEIN-PE): a pooled subgroup analysis of two randomised controlled trials. Lancet Haematol 2014; 1(1): e37–e46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young AM, Marshall A, Thirlwall J, et al. Comparison of an oral factor Xa inhibitor with low molecular weight heparin in patients with cancer with venous thromboembolism: results of a randomized trial (SELECT-D). J Clin Oncol 2018; 36(20): 2017–2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liang B, Zhao L-Z, Liao H-L, et al. Rivaroxaban for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Medicine 2019; 98(48): e18087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Higgins JPT, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, et al. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ 2003; 327(7414): 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ageno W, Mantovani LG, Haas S, et al. Subgroup analysis of patients with cancer in XALIA: a noninterventional study of rivaroxaban versus standard anticoagulation for VTE. TH Open 2017; 1(1): e33–e42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yang J. Application of two anticoagulant drugs in patients with cancer complicated with venous thromboembolism. Clin Educ Gen Pract 2019; 17(4): 338–340. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen AT, Spiro TE, Büller HR, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in acutely ill medical patients. N Engl J Med 2013; 368(6): 513–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Khorana AA, Soff GA, Kakkar AK, et al. Rivaroxaban for thromboprophylaxis in high-risk ambulatory patients with cancer. N Engl J Med 2019; 380(8): 720–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sterne JAC, Sutton AJ, Ioannidis JPA, et al. Recommendations for examining and interpreting funnel plot asymmetry in meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials. BMJ 2011; 343: d4002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Farge D, Durant C, Villiers S, et al. Lessons from French national guidelines on the treatment of venous thrombosis and central venous catheter thrombosis in cancer patients. Thromb Res 2010; 125: S108-S116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.van der Hulle T, den Exter PL, Kooiman J, et al. Meta-analysis of the efficacy and safety of new oral anticoagulants in patients with cancer-associated acute venous thromboembolism. J Thromb Haemost 2014; 12(7): 1116–1120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vedovati MC, Germini F, Agnelli G, et al. Direct oral anticoagulants in patients with VTE and cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Chest 2015; 147(2): 475–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barbarawi M, Zayed Y, Kheiri B, et al. The role of anticoagulation in venous thromboembolism primary prophylaxis in patients with malignancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Thromb Res 2019; 181: 36–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fuentes HE, McBane RD, 2nd, Wysokinski WE, et al. Direct oral factor Xa inhibitors for the treatment of acute cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Mayo Clin Proc 2019; 94(12): 2444–2454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li A, Garcia DA, Lyman GH, et al. Direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) versus low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) for treatment of cancer associated thrombosis (CAT): a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb Res 2019; 173: 158–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang Y-S, Lv H-C, Li D-B, et al. Efficacy and safety of direct oral anticoagulants for secondary prevention of cancer-associated thrombosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials and prospective cohort studies. Front Pharmacol 2019; 10: 773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Martinez BK, Sheth J, Patel N, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of real-world studies evaluating rivaroxaban for cancer-associated venous thrombosis. Pharmacotherapy 2018; 38(6): 610–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xing J-L, Yin X-B, Chen D-S. Rivaroxaban versus enoxaparin for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in patients with cancer: a meta-analysis. Medicine 2018; 97(31): e11384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaudhury A, Balakrishnan A, Thai C, et al. The efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban and dalteparin in the treatment of cancer associated venous thrombosis. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 2018; 34(3): 530–534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alzghari SK, Seago SE, Garza JE, et al. Retrospective comparison of low molecular weight heparin vs. warfarin vs. oral Xa inhibitors for the prevention of recurrent venous thromboembolism in oncology patients: the Re-CLOT study. J Oncol Pharm Pract 2017; 24(7): 494–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oh S-B, Seol Y-M, Kim H-J, et al. Retrospective evaluation of the efficacy and safety of rivaroxaban in patients with cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: a single-center study. Medicine 2019; 98(30): e16514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wang X-F, Liang B, Chen C, et al. Long intergenic non-protein coding RNA 511 in cancers. Front Genet 2020; 11: 667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang X-F, Liang B, Zeng D-X, et al. The roles of MASPIN expression and subcellular localization in non-small cell lung cancer. Biosci Rep 2020; 40(5): BSR20200743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Liang B, Li S-Y, Gong H-Z, et al. Clinicopathological and prognostic roles of STAT3 and its phosphorylation in glioma. Dis Markers. 2020; 2020: 8833885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Khorana AA, Noble S, Lee AYY, et al. Role of direct oral anticoagulants in the treatment of cancer-associated venous thromboembolism: guidance from the SSC of the ISTH. J Thromb Haemost 2018; 16(9): 1891–1894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-2-sci-10.1177_00368504211012160 for Rivaroxaban for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism by Bo Liang, Yi Liang, Li-Zhi Zhao, Yu-Xiu Zhao and Ning Gu in Science Progress

Supplemental material, sj-tif-1-sci-10.1177_00368504211012160 for Rivaroxaban for cancer-associated venous thromboembolism by Bo Liang, Yi Liang, Li-Zhi Zhao, Yu-Xiu Zhao and Ning Gu in Science Progress