Abstract

Organ donation provides a life-saving opportunity for patients with organ failure. China, like most countries, is faced with organ shortages. Understanding public opinion regarding organ donation in China is critical to ensure an increased donation rate. Our study explored public concerns and attitudes toward organ donation, factors involved, and how the public pays attention to organ donation. Sixteen million users’ public information (i.e. gender, age, and geographic information) and posts from January 2017 to December 2017 were collected from Weibo, a social media platform. Of these, 1755 posts related to organ donation were included in the analysis. We categorized the posts and coded the users’ attitudes toward organ donation and the associations between the demographics. The most popular posts mentioning organ donation were “publicly expressing the willingness to donate organs.” Furthermore, 87.62% of posts exhibited a positive attitude toward organ donation, whereas only 7.44% exhibited a negative attitude. Most positive posts were “saluting the organ donors,” and most negative posts involved “fear of the family’s passive medical decision.” There was no significant gender difference in the users’ attitudes, but older people generally had a more negative attitude. Users with negative attitudes mainly distrust the medical system and are worried that the donated organs may be used in improper trading. Social media may be an important channel for promoting organ donation activities, and it is important to popularize scientific knowledge related to organ donation in order to eliminate the public’s misunderstanding of organ donation and transplantation.

Keywords: Public health, organ donation, public opinion, social media, Weibo

Introduction

Organ donation/transplantation represent the only definitive treatment for end-stage organ failure.1,2 In 2015, 126,670 solid organ transplantations were completed worldwide; 3 however, even this number is unable to meet 10% of the demand. 4 There is a large gap between organ supply and demand in most countries in the world.

In China, more than 13,000 organ transplantations were completed in 2016, which was the second largest number in the world. 5 However, more than 300,000 people are waiting for organ transplantations each year in China, resulting in an organ supply–demand ratio of 1:30. 6 This ratio is caused by the low rate of actual deceased donors of 2.95 (per million inhabitants), which is much lower than the global rate of 8.11. 6 Some researchers have suggested that the Confucian cultural norm, especially on which states that “it is a responsibility to maintain the physical integrity of the body after death, because every physical part of our body comes from our parents,” hinders organ donation (OD) in China, 7 but some researchers hold the opposing opinion that the fundamental Confucian norm “Ren” (humaneness or benevolence) allows for body donation as people have a moral duty to help others.8,9 With massive amounts of people moving to the cities, a new generation of young people has dramatically changed the cultural traditions, with most living a modern lifestyle and being open to more different perspectives. It has, therefore, become crucial to understand the attitudes of different individuals toward OD, especially those of the youth in China.

Social media has become increasingly important for daily communication. Individuals tend to be less restrained when online, and hence disclose more of their true feelings. 10 In China, Weibo is a popular social media platform that is similar to Twitter, on which users can view their followings’ posts by default, and users can also browse non-followings’ public posts by searching for or visiting their personal pages. Weibo has more than 600 million registered users, which accounts for 75% of the total Internet users in China. 11 Moreover, Weibo produces more than 100 million posts every day. 12 As one of the most important social media platforms in China, Weibo is a key space for the dissemination of information and interaction of points of view.

Recent studies have begun to mine public opinion on health issues through social media.13–15 In the organ transplantation field, previous research has analyzed the public discourse on heart transplantation in Japan using Twitter, and has identified that the most positive tweets are related to reports of the favorable outcomes of recipients, which suggests that emphasizing the outcomes of recipients can facilitate increased contemplation of OD for most people. 16 This provides an opportunity to understand the public’s concerns about organ transplantation using social media, and especially to identify the different characteristics of people talking about OD on social media. To the best of our knowledge, currently, there are only two studies that have examined OD through Chinese social media. Shi and Salmon 17 focused on a network study identifying opinion leaders to promote OD on social media, while Jiang et al. 18 examined media content and effects of OD on social media. These studies provide valuable insights and references for social media research about OD. However, there is no direct evidence on public attitudes toward OD based on social media data in China. Using a large sample of Chinese social media users, our study aimed to examine the concerns of users, belonging to different ages and gender, regarding OD and to further explore the reasons behind the positive or negative public attitude toward OD. Specifically, we explored the following three aspects: (1) what the public concerns and attitudes toward OD are, (2) which factors are involved in people’s positive or negative attitudes toward OD, and (3) how the public pays attention to OD.

Methods

This is an observational study using data collected from social media (Figure 1). The data collection and analysis process were approved by the Independent Ethics Committee.

Figure 1.

The method workflow consists of three main steps: (1) collection of posts that are related to discussions about OD, (2) content analysis for public opinions toward OD, and (3) statistical analysis for demographic differences of the public’s attention to OD.

Data collection

Following the data collection process used in previous research,17,18 we used the Web crawler program to capture social media data about OD on Weibo (One of the largest Chinese social media platforms). First, we obtained a dataset on more than 16 million Weibo users, 18 which included all of their publicly disclosed information (i.e. gender, age, and geographic information) and posts from January 1 to December 31, 2017, through Weibo’s application programming interface. The dataset covered 4% of the total users 19 from 365 cities in China, and included 2.1 billion posts.

We used the search function to retrieve all posts about OD from the dataset. Based on previous research suggestions, 17 the search keywords included 85 combinations of “organ+donation/donating/donated/donate/shortage” or “specific organ name (i.e. kidney, liver)+donation/donating/donated/donate/shortage.” In the data cleaning, we first eliminated the posts that were not consistent with OD types listed on the Chinese organ donor registration application, such as “hematopoietic stem cell donation” and “sperm donation.” We also excluded news reports and celebrity campaign posts, which only contained facts and information that did not reflect the users’ attitudes toward OD. Finally, 1755 textual posts were included in our analysis (see Figure 1).

Data analysis

Content analysis

In line with previous research, we examined these posts using content analysis.18,20 All the posts were classified according to their themes and attitudes. Two researchers first screened the posts independently. Then, one of the researchers proposed a coding manual and submitted it to the second researcher for evaluation. The second researcher provided suggestions and made changes after reaching a consensus with the first researcher. They coded the first 20% (350/1755) of the posts. The disparities in coding were discussed, for which the coders arrived at an agreement and further revised the coding manual. Based on the revised coded manual, one of the researchers coded the remaining posts.

We also analyzed the public’s attention to OD, as compared to other topics, and the temporal characteristics and demographic differences related to it. To compare the public’s attention to OD with other topics, we chose the topics of general donations and diseases relevant to OD in the same dataset. We searched for these topics (e.g. renal failure, liver cirrhosis), and calculated the number of posts to compare with those regarding OD. In addition, we presented the daily number of posts about OD across 2017, which revealed the temporal characteristics of the public’s attention to OD.

Statistical analysis

For demographic differences of the public’s attention to OD, we employed chi-square tests to compare the attention to OD of users of different genders (male, female), age groups (10–30 years as the younger group, 31–70 years as the older group), and regions.

Results

Public concerns and attitudes toward OD

Public concerns about OD

Through a content analysis of the 1755 social media posts, we categorized the discussion of OD topics and obtained seven categories, as shown in Table 1; these included the following. (1) Publicly expressing the willingness to donate organs (17.05%): many users registered for OD on special dates, such as birthdays and graduation ceremonies, and posted the posts on social media, which suggested that, for these users, OD registration is a ritual involving special self-fulfillment values. (2) Discussion of videos and literature related to OD (15.28%): users express positive emotions, such as being touched and having respect for OD, after watching videos or reading the related literature. (3) Discussion of cultural opinions related to OD (15.28%): this category was mainly related to whether OD is a form of continuation of life, and most of the users supported this opinion. (4) Discussion regarding the autonomy of decision-making about OD (6.69%): this kind of discussion mainly concentrated on the tension between the family’s decision-making and individual’s decision-making regarding whether families have the right to make OD decisions for the dying. (5) Discussion of the approaches to OD (6.61%): this category mainly discussed how to register for OD online. (6) Doubts about the medical system (4.79%): some users had doubts about a range of medical issues related to the organ transplantation process, such as what conditions may be judged as death, and whether doctors use donated organs for profit. (7) Others (34.04%).

Table 1.

Categories of public concerns about OD.

| Categories | % (n = 1755) | Definition | Example post |

|---|---|---|---|

| Publicly expressing the willingness to donate organs | 17.05 | Express users’ willingnessto donate their organs, andthe reasons are not discussed in detail. | “I want to be an organ donor.” |

| Discussion of videos andliterature related to OD | 15.28 | Express users’ feelings after watchingvideos or books. | “Last night, I watched The World. It’s very shocking.The family of organ donor is really great.” |

| Discussion of cultural opinionsrelated to OD | 15.28 | Discuss the impact of culturalopinions on OD decision-making. | “What we need to change is China’s old idea thatfor thousands of years, which we have to leave thewhole body to make peace. Instead of preservingthe whole body, it’s better to let some of them stayin others’ bodies and let others live better.” |

| Discussion regardingthe autonomyof decision-making about OD | 6.69 | Discuss the situation when thedecision of organ donors’ conflictwith their families. Who can have theright to make final decision? | “I was unanimously opposed by my parents to signa consent for OD.” |

| Discussion of theapproaches to OD | 6.61 | Ask about approaches to donateorgans, or publicize ways to donate organs | “I don’t know what procedures of OD are needed?Is there such an institution in Ningbo?” |

| Doubts about themedical system | 4.79 | Express concern about opacity andeconomic corruption in OD | “Never sign a consent form for OD after anaccident, or your chances of accident and deathbecome uncontrollable.” |

| Others | 34.04 | The rest of posts that are hard to becategorized explicitly | “Salute to every organ donor.” |

Public attitudes toward OD

Of the 1755 posts, 1357 clearly revealed attitudes about OD. Among them, 87.62% (n = 1189) showed a positive attitude toward OD, 7.44% (n = 101) showed a negative attitude, and 4.94% (n = 67) showed a neutral attitude. There was no significant gender difference in the users’ attitudes toward OD (χ2 = 3.10, p = 0.21) but people from the older group had a more negative attitude toward OD than those from the younger group (χ2 = 11.74, p = 0.003 and < 0.05) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Attitudes toward OD among the different age groups.

| Positive (%) | Negative (%) | Neutral (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1189 (87.62) | 101 (7.44) | 67 (4.94) |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 798 (88.77) | 58 (6.45) | 43 (4.78) |

| Male | 380 (85.78) | 40 (9.03) | 23 (5.19) |

| Age (years) | |||

| The younger group (age 10–30) | 381 (90.07) | 26 (6.15) | 16 (3.78) |

| The older group (age 31–70) | 122 (85.31) | 20 (13.99) | 1 (0.70) |

Factors involved in positive or negative attitudes toward OD

The 1189 posts with positive attitudes toward OD, which emerged from the dataset, were divided into four categories, as follows. (1) Saluting the organ donors (29.35%): most users expressed their respect for the organ donors after they watched or read a media presentation about the OD process. (2) OD can help others (20.94%): many users expressed the opinion that OD can help others, and thus make a great contribution to society. (3) OD is a continuation of life (14.38%): some users suggested that transplantation is a form of extending life after death, because someone will continue to live with the donated organs. Some users even argued that rather than letting the body be cremated, donating organs can at least keep part of the body in this world and living longer. (4) Lack of clear opinions (35.32%): some users publicly claimed “Today, I successfully applied for organ donation. I’m very happy,” or “I always support organ donation.” However, these users did not disclose more specific information about attitudes toward OD. For the categories without clear reasons, there were no significant differences in gender or age (Table 3).

Table 3.

Rank of categories for positive attitude toward OD.

| Rank | Total (n = 1189) | Male (n = 380) | Female (n = 798) | The youngergroup (n = 381) | The older group(n = 122) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lack of clear opinions(35.23%) | Lack of clear opinions(34.47%) | Lack of clearopinions (35.13%) | Lack of clearopinions (35.96%) | Saluting organ donors (39.67%) |

| 2 | Saluting organ donors(29.35%) | Saluting organ donors(31.05%) | Saluting organdonors (28.98%) | Saluting organdonors (26.51%) | Lack of clear opinions (27.27%) |

| 3 | OD can help others(20.94%) | OD can help others(20.26%) | OD can helpothers (21.46%) | OD can helpothers (22.31%) | OD can help others (16.53%) |

| 4 | OD is a continuationof life (14.38%) | OD is a continuationof life (14.21%) | OD is a continuationof life (14.43%) | OD is a continuationof life (15.22%) | OD is a continuation of life (16.53%) |

A total of 101 posts with negative attitudes toward OD, which emerged from the dataset, were also divided into four categories. (1) Fear of the family’s passive medical decision (38.61%): some users feared that when they were not fully conscious, the family may conspire with the hospital to use passive medical treatment in order to seek economic compensation for the OD. (2) Distrust of the medical system (31.68%): some users worried that the donated organs would be used for improper trading, such as selling organs to the rich at a high price rather than queuing up for the needy as per normal procedure. (3) Values about death and the body (6.93%): some users had the desire to preserve a complete body and some found it difficult to accept living organ transplantation surgery. (4) Lack of clear opinions (22.78%): Some users just publicly claimed as “Anyway, organ donation is still hard for me to accept,” and did not disclose more detail. While the most common factor hindering OD among females was worrying about passive treatment decisions taken by the family, for males, this factor was not significant. Moreover, while users under 30 years of age showed the same pattern as females, users from the older group showed the same pattern as males. Because males and older people tend to have a dominant status within the family, they worry more about external social problems than about decisions taken within the family (Table 4).

Table 4.

Rank of categories for factors hindering OD.

| Rank | Total (n = 101) | Male (n = 40) | Female (n = 58) | The younger group (n = 26) | The older group (n = 20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Fear of the family’sdecision (38.61%) | Distrust of the medicalsystem (50.00%) | Fear of the family’sdecision (55.17%) | Fear of the family’sdecision (57.69%) | Distrust of the medicalsystem (55.56%) |

| 2 | Distrust of the medicalsystem (31.68%) | Lack of clear opinions(22.50%) | Distrust of the medicalsystem (17.24%) | Distrust of the medicalsystem (19.23%) | Fear of the family’sdecision (22.22%) |

| 3 | Lack of clearopinions (22.78%) | Values about death andthe body (12.5%) | Lack of clearopinions (9.70%) | Lack of clear opinions(23.08%) | Values about death and the}body (11.11%) |

| 4 | Values about death andthe body (6.93%) | Fear of the family’sdecision (15.00%) | Values about death andthe body (3.45%) | Values about death and thebody (0.00%) | Lack of clearopinions (11.11%) |

Attention to OD

Public’s attention to OD compared to other topics

The number of posts discussing general donations and diseases relevant to OD (i.e. renal failure, liver cirrhosis), was significantly larger than those discussing OD (473,636 for general donation and 64,509 for diseases relevant to OD, while only 14,203 for OD). The average number of posts per user in 1 year that discussed OD was only 1.10, which was significantly lower than an average of 1.37 posts discussing the diseases relevant to OD (F = 123.60, p < 0.001) and 1.79 posts discussing general donations (F = 247.82, p < 0.001). The results suggest that the absolute number of posts discussing OD is large, but that it is not a hot topic among the public when compared with other topics.

Public’s attention to OD compared to other topics

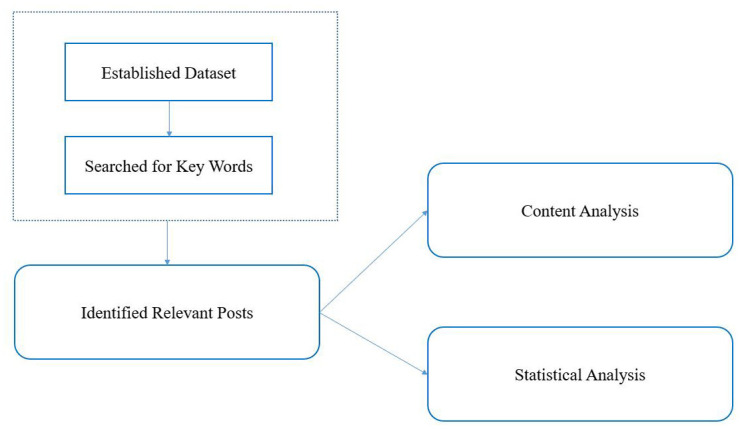

In terms of temporal characteristics, the discussion of OD showed a strong event-driven pattern. That is, the peaks of the discussions in a year were usually caused by specific events (Figure 2). Specifically, three types of events would lead to a greater number of discussions; these included the following. (1) Comments about an OD campaign: publicity videos on social media tended to cause a lot of discussion, mostly about positive emotional expressions and public statements of volunteering for OD. For example, “I just saw this advertisement and cried. I would like to register as an organ donor.” (2) Discussions caused by opinion leaders: the opinion leaders’ attitudes about OD were reposted for discussion, most of which were in favor of the opinion leaders, but a few users did not agree with the opinion leader. For example, an opinion leader with more than 10 million followers posted that “OD is a personal freedom and it is wrong to sneer at those who are willing to donate organs,” which was reposted with a lot of support. However, a few users argued that “Free donation will reduce people’s enthusiasm for OD and there should be economic compensation for the relatives of organ donors.” (3) Re-post lottery campaigns: the purpose of a re-post lottery campaign initiated by an individual is to draw public attention to OD. Those who conducted a re-post lottery campaign expressed their support for OD. For example, a user posted, “May more people see this video and learn about OD. For users re-posting this post, we will randomly draw one and give him/her 1000 yuan (about 140 dollars)!”

Figure 2.

The number of posts mentioning OD per day.

Demographic characteristics of the public’s attention to OD

In terms of demographic characteristics, 1621 users who discussed OD provided their gender information, of which 66.25% were women. Even considering the proportion of women in total, women were more likely to participate in OD discussions than men (χ2 = 39.08, p < 0.001). The older users were more willing to discuss OD online than younger users, χ2 = 11.36, p < 0.001. There were no significant differences in public’s attention to OD across the different regions in China (χ2 = 6.62, p = 0.011 and <0.05).

Discussion

By monitoring public’s discussion about OD on a Chinese social media platform, this study revealed that (1) the public’s attention to OD on social media was mostly aroused by specific events; (2) female and older users were more willing to discuss OD online; (3) although the degree of public attention on social media needs to be improved, most of the users have a positive attitude toward OD because they believe that OD can help others and can even be a form of continuation of life; and (4) users with negative attitudes mainly distrust the medical system because they are worried about the medical system using donated organs for improper trading.

Previous studies have mainly focused on people’s attitudes and behaviors toward OD,7–9,21 but few have revealed the degree of attention paid to OD in a large-scale population using objective and behavioral data. Our study found that people paid attention to OD to some extent on social media, but there is still a big gap when compared with other topics (e.g. diseases relevant to OD, general donation). Some studies have confirmed that there is a positive correlation between the degree of attention paid to OD and the rate of OD.22–24 According to our results, the public’s attention to OD on social media is often aroused by specific events, such as discussions on OD campaigns. How to effectively arouse more public attention about OD through social media is one of the urging problems that needs to be answered in the future. On May 1, 2012, Facebook altered its platform to allow users to specify “Organ Donor” as part of their profiles, which has made great progress in the growth of OD rates. 25 This successful case can benefit future promotion campaigns of OD on social media.

By analyzing the content of public’s discussion about OD on social media, we found that most of the discussion is to express their willingness to donate organs and express their feelings after watching videos relevant to OD. Thus, we propose that people may have a high desire to disclose their OD willingness on social media, and may be more easily inspired online by public campaigns than offline. As indicated in our results, many users would like to post “I want to be an organ donor,” to express their willingness in public. In addition, the successful case of Facebook allowing users to specify “Organ Donor” as part of their profiles further demonstrates the importance people identifying as organ donors. To this end, we suggest that OD registration agencies may consider providing the service that helps people voluntarily disclose their OD identity on social media after completing OD registration. For example, OD registration agencies may provide new registrants with the choice of whether to share the message as “You have become the xxx-th (e.g. 10,000th) registered organ donors in China “ through the agency’s official account on social media. Moreover, as previous research has shown that online media can effectively promote organ donor registration, 24 OD registration agencies may also consider posting more public service advertisements on social media.

Previous studies have found that OD rates mainly influenced by two factors: issues with the medical system and cultural factors. 26 The medical system oversees organ allocation after OD, how hospitals determine brain death, and whether the family members have the right to decide OD for sudden accidental death.27,28 Cultural factors include religious and cultural beliefs about brain death and transplants,8,29 such as the Confucian cultural norm which states that “It is a responsibility to maintain the physical integrity of the body after death.” In this study, we found that the main factors hindering OD were misunderstanding and distrust of the medical system, which resulted in conspiracy theories, such as “Never sign an accidental consent for OD, or your situation following an accident and death will become uncontrollable!” and misunderstandings about the organ transplantation process, such as “Transplantation surgery will be performed before the person really dies.” In addition, many female users expressed concerns that “The family will opt for passive treatment of potential organ donors in order to obtain economic compensation for OD,” and that the vulnerable groups included “women and defective infants” who may be used by spouses and parents for profit.

These results suggest that it is essential to further publicize OD in two ways. First, it is important to popularize the relevant scientific knowledge about organ transplantation to eliminate the misunderstandings surrounding the organ transplantation process, for example, to emphasize the death donor rule. Second, it is necessary to clarify and strengthen the transparency of the OD system, and to eliminate the public’s distrust of the medical system. As some developed countries have well-established criteria for deceased donor brain and cardiac death, such as the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School’s landmark report equating irreversible coma to death in 1968, 30 and the United Kingdom’s following criteria from 1979. 31 We believe that with the efforts of the world’s medical peers, the continuous improvement of the system will promote public trust in the system.

On the other hand, the influence of the traditional Confucian norm regarding the body on people’s willingness to donate organs was much less than in a previous survey. 32 According to the Chinese classic of Filial Piety, which is an important source of traditional Confucian thought, “. . . the body, hair, and skin are given by the parents, and one should not damage them. This is the first thing of being filial,” 29 which is regarded as being contrary to OD. However, in our research, only a few users wanted to preserve the complete body after their death because of the Confucian concept of the body; most of the users were more supportive of the opinion that OD can save others while also extending their own life values. In addition, the discussion of how to approach OD mostly focused on how to enter the online OD registration, which also suggests that we should make full use of the advantages of the Internet in order to further promote the online OD registration.

Our research is not without some limitations. First, although it is important to understand online users’ attitudes toward OD, whether we can generalize the results to people who seldom use social media remains to be further verified through further empirical studies such as surveys or in-depth interviews. People’s attitudes toward OD may also vary in online and offline situations, and for those who did not disclose their personal information, it is worth further exploration as to whether there are different opinions based on age and gender. Second, our research mainly focused on the residents of China. Considering the cultural influences, it would be worthwhile to explore the concerns of Chinese people about OD living in America or other Western countries. People living in the West have a more analytic thinking style, 33 which gives them a higher sense of control, 34 and likely means that decision-making regarding OD will be more independent. As recent studies found that European transplant health care professionals recognize the role of social media platforms in promoting organ donation,35,36 in the future we can consider analyzing people’s opinions in different regions through social media data, and pay close attention to the progress and role of social media for organ donation in different countries. Third, future research should attempt to combine this data with donor family refusal data for further analysis and develop detailed strategies for national/regional promoters and organ procurement organizations. However, despite these limitations, our results still provide important insights; specifically, that it is important to listen to concerns that the public expresses on social media and to provide correct information to eliminate the public’s doubts about the OD process.

Overall, our findings suggest that people seem to be more inclined to support OD, at least on social media platforms. This may be because social media platforms are a relatively more public platform, and people’s desired social effect is stronger than in the private context. Nevertheless, we believe that social media may be an important channel for OD promotion activities. Nowadays, the Internet has increasingly become an important field of health care promotion activities. It is of great value to study people’s interest and attitudes toward OD that they express on social media. They are more effective than traditional offline activities in terms of coverage and actual influence. Of course, this requires future research to provide more direct empirical evidence.

Conclusions

This research found that most of the users on the social media platform, Weibo, have a positive attitude toward OD, and many people publicly express their willingness to donate organs. For users who have a positive attitude toward OD, they tend to express their respect for the organ donors and believe that OD can help others. Users who have a negative attitude mainly distrust the medical system and are worried that the donated organs may be used in improper trading. The public’s attitude toward OD is significantly influenced by OD campaigns and opinion leaders. Our findings indicate that social media may be an important channel for promoting OD activities, and that it is important to popularize the scientific knowledge related to OD in order to eliminate the public’s misunderstanding of the process involved in OD and transplantation.

Author biographies

Dr. Xiling Xiong is a Post Doctoral fellow of School of Tourism Management at Sun Yat-sen University, Guangzhou, China. His research focuses on social media and consumer psychology.

Dr. Kaisheng Lai is a Professor of School of Journalism and Communication at Jinan University, Guangzhou, China. His research focuses on health communication, Internet and new media.

Mrs. Wenshi Jiang is a Supervisor of Department of Medical Affair, Intelligence Sharing for Life Science Research Institute, Shenzhen, China. Her research focuses on organ donation.

Dr. Xuyong Sun is a Director of transplantation medical center, Second Affiliated Hospital of Medical University of Guangxi, Nanning, China. His research focuses on transplantation medicine.

Jianhui Dong is an Associate Chief Physician of Institute of Transplantation Medicine at No. 923 Hospital of Chinese PLA, Nanning, China. His research focuses on organ transplantation medicine and organ donation management.

Ziqin Yao is an Office Manager of Organ Procurement Organization at The First Affiliated Hospital of University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, China. His research focuses on organ donation management.

Lingnan He is an Associate Professor of School of Communication and Design at Sun Yat-Sen University, China. His research focuses on big data and social media communication.

Footnotes

Author’s Note: Xuyong Sun is currently affiliated with Transplantation Medical Center, Second Affiliated Hospital of Medical University of Guangxi, China.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This research was funded by the Major Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China, grant number 18ZDA165.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval for this study was obtained from *Ethics Committee of The 923 Hospital of PLA Joint Logistics Support Force* (approval number 2018-1011-0126).

Informed consent: Informed consent was not sought for the present study because * This is an observational study using data collected from social media without any personal correspondence. The data collection and analysis process were approved by the Independent Ethics Committee*.

Trial registration: Not applicable. This is an observational study using data collected from social media without any trial.

ORCID iDs: Xiling Xiong  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1541-1569

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1541-1569

Lingnan He  https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6679-7487

https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6679-7487

References

- 1.Whisenant DP, Woodring B. Improving attitudes and knowledge toward organ donation among nursing students. Int J Nurs Educ Scholarsh 2012; 9(1): 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rana A, Gruessner A, Agopian VG, et al. Survival benefit of solid-organ transplant in the United States. JAMA Surg 2015; 150(3): 252–259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Organization WH. Organ donation and transplantation activities, http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-reports-2014/ (accessed on 28 September 2019)

- 4.Matesanz R, Domínguez-Gil B, Coll E, et al. How Spain reached 40 deceased organ donors per million population. Am J Transplant 2017; 17(6): 1447–1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Organization WH. Global observatory on donation and transplantation, http://www.transplant-observatory.org/data-charts-and-tables/chart/ (accessed on 28 September 2019)

- 6.Daily B. 1:30! The gap between the supply and demand of Chinese organ transplantation is huge, http://bj.people.com.cn/n2/2017/0612/c233086-30312330.html (accessed on 28 September 2019)

- 7.Wei W, Hui T, Hang Y, et al. Attitudes toward organ donation in China. Chinese Med J 2012; 125(1): 56–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Y. On the impacts of traditional Chinese culture on organ donation. J Med Philos 2013; 38(2): 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones DG, Nie JB. Does confucianism allow for body donation? Anat Sci Educ 2018; 11(5): 525–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suler J. The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychol Behav 2004; 7(3): 321–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DMR. 70 Amazing Weibo statistics and facts, http://expandedramblings.com/index.php/weibo-user-statistics/ (accessed on 28 September 2019)

- 12.Center CINI. Statistical report on China’s internet development, http://www.cnnic.net.cn/hlwfzyj/hlwxzbg/hlwtjbg/201808/t2018082070488.htm (accessed on 28 September 2019)

- 13.Taylor J, Pagliari C. Comprehensive scoping review of health research using social media data. BMJ Open 2018; 8(12): e022931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright LA, Golder S, Balkham A, et al. Understanding public opinion to the introduction of minimum unit pricing in Scotland: a qualitative study using Twitter. BMJ Open 2019; 9(6): e029690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang F, Wendorf Muhamad J, Yang Q. Exploring environmental health on Weibo: a textual analysis of framing haze-related stories on Chinese social media. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019; 16(13): 2374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nawa N, Ishida H, Suginobe H, et al. Analysis of public discourse on heart transplantation in Japan using social network service data. Am J Transplant 2018; 18(1): 232–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi J, Salmon CT. Identifying opinion leaders to promote organ donation on social media: network study. J Med Internet Res 2018; 20(1): e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang X, Jiang W, Cai J, et al. Characterizing media content and effects of organ donation on a social media platform: content analysis. J Med Internet Res 2019; 21(3): e13058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Center SM-BD. 2017 Micro-blog user development report, https://data.weibo.com/report/reportDetail?id=404&display=0&retcode=6102 (accessed on 28 September 2019)

- 20.Hand RK, Kenne D, Wolfram TM, et al. Assessing the viability of social media for disseminating evidence-based nutrition practice guideline through content analysis of Twitter messages and health professional interviews: an observational study. J Med Internet Res 2016; 18(11): e295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hu D, Huang H. Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness toward organ donation among health professionals in China. Transplantation 2015; 99(7): 1379–1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Quick BL, Kim DK, Meyer K. A 15-year review of ABC, CBS, and NBC news coverage of organ donation: implications for organ donation campaigns. Health Commun 2009; 24(2): 137–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Quick BL, Meyer KR, Kim DK, et al. Examining the association between media coverage of organ donation and organ transplantation rates. Clin Transplant 2007; 21(2): 219–223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron AM, Massie AB, Alexander CE, et al. Social media and organ donor registration: the Facebook effect. Am J Transplant 2013; 13(8): 2059–2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stefanone M, Anker AE, Evans M, et al. Click to “like” organ donation: the use of online media to promote organ donor registration. Prog Transplant 2012; 22(2): 168–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lock MM. Twice dead: organ transplants and the reinvention of death. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fukushima N, Konaka S, Yasuhira M, et al. (eds.). Study of education program of in-hospital procurement transplant coordinators in Japan. Transplant Proc 2014; 46(6): 2075–2078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fukushima N, Ono M, Saiki Y, et al. (eds.). Donor evaluation and management system (medical consultant system) in Japan: experience from 200 consecutive brain-dead organ donation. Transplant Proc 2013; 45(4): 1327–1330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lau DC. The analects. London: Penguin, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Coma ADoI. Report of the Ad Hoc committee of the Harvard medical school to examine the definition of brain death. JAMA 1968; 205(6): 337–340. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.UK CoMRCaTFit. Diagnosis of death. Lancet 1979; 1(8110): 2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green C, Bowden D, Molony D, et al. Attitudes of the medical profession to whole body and organ donation. Surgeon 2014; 12(2): 73–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nisbett RE, Peng K, Choi I, et al. Culture and systems of thought: holistic versus analytic cognition. Psychol Rev 2001; 108(2): 291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou X, He L, Yang Q, et al. Control deprivation and styles of thinking. J Pers Soc Psychol 2012; 102(3): 460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bellini MI, Parisotto C, Dor FJ, et al. Social media use among transplant professionals in Europe: a cross-sectional study from the European Society of Organ Transplantation. Exp Clin Transplant 2019; 18(2): 169–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Henderson ML, Adler JT, Rasmussen SEVP, et al. How should social media be used in transplantation? A survey of The American Society of Transplant Surgeons. Transplantation 2019; 103(3): 573–580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]