Abstract

Objective:

To detail the implementation of a dedicated liver surgery program at a university-affiliated hospital and to analyze its impact on the community, workforce, workload, complexity of cases, the short-term outcomes, and residents and young faculties progression toward technical autonomy and academic production.

Background:

Due to the increased burden of liver tumors worldwide, there is an increased need for liver centers to better serve the community and facilitate the education of trainees in this field.

Methods:

The implementation of the program is described. The 3 domains of workload, research, and teaching were compared between 2-year periods before and after the implementation of the new program. The severity of disease, complexity of procedures, and subsequent morbidity and mortality were compared.

Results:

Compared with the 2-year period before the implementation of the new program, the number of liver resections increased by 36% within 2 years. The number of highly complex resections, the number of liver resections performed by residents and young faculties, and the number of publications increased 5.5-, 40-, and 6-fold, respectively. This was achieved by operating on more severe patients and performing more complex procedures, at the cost of a significant increase in morbidity but not mortality. Nevertheless, operations during the second period did not emerge as an independent predictor of severe morbidity.

Conclusions:

A new liver surgery program can fill the gap between the demand for and supply of liver surgeries, benefiting the community and the development of the next generation of liver surgeons.

Mini abstract: A new liver surgery program at a university-affiliated hospital filled the gap between the demand for and supply of liver surgeries, benefited the community and the surgical autonomy of trainees.

INTRODUCTION

The rising burden of liver tumors1, 2 and the progress in perioperative management have allowed the safe expansion of the resection of liver tumors.3–6 The increased need for competent liver centers/surgeons7, 8 is exacerbated by their heterogeneous geographical distribution, which in turn causes variable decisions regarding the performance of liver resection,9 as well as the imposition of travel burdens, on some patients. The decision not to perform liver resection can lead to the loss of chance for optimal survival while traveling for surgery increases the expense to the healthcare system and patients,10,11 impedes the same center-rehospitalization for rescue procedures after discharge,12 and negatively impacts short- and long-term outcomes.13

Moreover, recent reports have highlighted the gaps between the expectations and experiences of residents in general surgery with regard to exposure to hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) surgery14,15; and the definitions of fellowship in HPB surgery remain heterogeneous across continents.15–18 The few reports describing the implementation of a new liver resection program at a university-affiliated hospital19–22 focused on the increased workload.

The current study analyzes the impact of such a program on the workforce, workload, complexity of cases, short-term outcomes, and residents/young faculties’ progression toward technical autonomy and academic production.

METHODS

Rationale for a Dedicated Program and Implementation

A new program of liver surgery was established at the Chaim Sheba Medical Center (CSMC, affiliated with the Sackler Tel Aviv University of Medicine, Israel) on January 1, 2018. The impetus to develop such a program resulted from a primary evaluation demonstrating that: (1) approximately 700 liver resections are performed yearly in 20 public hospitals and 2 private hospitals (https://www.ihpba.org/200_Israel-Chapter.html) in Israel (with a population of 9 million inhabitants); (2) a significant proportion of patients had to travel abroad to undergo liver surgery; (3) senior residents had to travel abroad for HPB fellowship, with many administrative and personal obstacles.23,24 Given the situation, a senior HPB surgeon (D.A.) was recruited (1) to offer easy public access to liver surgery to an increased number of patients; (2) to teach liver surgery to younger colleagues; and (3) to develop their academic production. Before the new program, liver surgery was performed by a single surgeon who had participated in a 2-year fellowship in the early 1990s. Only the liver surgery portion of the HPB program is analyzed here. As per agreement between his original University (Centre Hépato-Biliaire, Université Paris-Saclay, Villejuif, France) and the SMC, the salary of the senior surgeon was paid 50–50 by these institutions.

Surgical Workforce, Participation in Existing CSMC Meetings and Implementation of New Meetings

The new HPB services available were promoted at all medical institutions in the community.

In addition to the senior surgeon, the liver surgery team included 2 junior faculty members including 1 working part-time in the intensive care unit, 2 senior residents from the general surgery department, and 2 young residents from the general surgery department according to a 4-week rotation. During the second year of the new program, the 2 senior residents went abroad for a 2-year HPB fellowship, and a medical assistant was recruited. The performance of all or part of a procedure (ie, liver mobilization, vascular control, liver parenchymal transection, Roux-en-Y for biliary reconstruction if needed) by a young faculty or a resident (senior or not) was prospectively recorded throughout the entire study period. No additional medical staff were hired; the 2 trainees involved in HPB surgery were those from the general surgery department according to a 4-week rotation. The staff from the general surgery department were in charge of the HPB patients and no additional staff was hired for the step-down unit, the ICU, or the ward. Finally, the medical assistant was the only staff member hired during Period 2.

A WhatsApp group was created to share (1) the perioperative management of the patients; (2) important bibliographical references; and (3) pictures of the operating field. Residents were also encouraged to use surgical and medical smartphone applications.

Conferences regarding the management of surgical liver diseases were held among the medical staff of the relevant CSMC departments. Mentoring by the senior surgeon was implemented with the junior faculties and senior residents, which was maintained for the latter by video-discussions during their fellowship abroad.

The senior surgeon attended all (1) the weekly outpatient clinics dedicated to potential candidates for liver surgery and (2) the existing CSMC multidisciplinary gastrointestinal and liver oncology meetings. A decision tree describing the decisions to proceed or not for surgery and the discrepancies between doctors pertaining to these decisions could not be produced because the needed data to build such a tree [number of patients (1) discussed; (2) collegially deemed nonoperable (temporarily of definitively); (3) collegially deemed operable, upfront or not] were not prospectively noted and could not be retrospectively retrieved. During period 2 only (see below), based on a reported model,25 any case in which a tumor was deemed unresectable by the nonsurgical oncologists/hepatologists, but was deemed resectable by the senior surgeon, was recorded.

Three new weekly events were implemented: (1) an outpatient clinic dedicated to primary liver tumors in the hepatology department; (2) a meeting with a senior anesthetist with expertise in liver surgery to establish a common strategy for the scheduled surgeries26 and to plan postoperative transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU); and (3) a morbidity and mortality conference to rank each complication for the calculation of the Comprehensive Complication Index (CCI, see below). As advised,27 in the case of ill-located tumor,6 the liver surgeons met with a radiologist with hepatobiliary imaging expertise to analyze the tumor vasculobiliary connections. A predefined and scheduled team of anesthetists and operating room nurses were available for all surgeries.

Study Population and Outcome Definitions

The study population included all consecutive patients undergoing hepatectomy from January 1, 2016, to December 31, 2019. A prospectively maintained database of hepatectomies was reviewed. During the entire study period, the preoperative assessment and preparation methods and the surgical techniques were the same as recently reported.6 Tables 1 and 2 detail the analyzed preoperative and intraoperative variables, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Characteristics (326 Hepatectomies)

| Characteristic | Overall 2016–2019, n = 326 | Period 2016–2017, n = 138 (42%) | Period 2018–2019, n = 188 (58%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | ||||

| Sex, male | 156 (47.9) | 66 (47.8) | 90 (47.9) | 0.99 |

| Age, y | 60 ± 13 | 60 ± 12 | 60 ± 14 | 0.99 |

| Age ≥ 75 y | 37 (11.3) | 11 (7.9) | 26 13.8) | 0.09 |

| ASA score ≥ III | 100 (30.7) | 23 (16.7) | 77 (41.0) | <0.0001 |

| Cirrhosis | 28 (8.6) | 7 (5.1) | 21 (11.2) | 0.052 |

| Tumors | ||||

| Malignant | 298 (91.4) | 129 (93.5) | 169 (89.9) | 0.25 |

| Primary | ||||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 35 (10.7) | 8 (5.8) | 27 (14.4) | 0.01 |

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 11 (3.4) | 5 (3.6) | 6 (3.2) | 0.83 |

| Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma | 11 (3.4) | 3 (2.2) | 8 (4.3) | 0.30 |

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 6 (1.8) | 2 (1.4) | 4 (2.1) | 0.65 |

| Other* | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.7) | 2 (1.1) | 0.75 |

| Secondary | ||||

| CRM | 214 (65.6) | 106 (76.8) | 108 (57.4) | 0.0003 |

| NEM | 4 (1.2) | 0 (—) | 4 (2.1) | 0.08 |

| NCNNE | 14 (4.3) | 4 (2.9) | 10 (5.3) | 0.29 |

| Liver and renal function tests | ||||

| Bilirubin µmol/L | 12 ± 20 | 9 ± 6 | 14 ± 25 | 0.03 |

| Bilirubin > 34 µmol/L | 10 (3.1) | 2 (1.4) | 8 (4.3) | 0.10 |

| AST, IU/L | 38 ± 46 | 32 ± 23 | 43 ± 56 | 0.05 |

| Albumin, g/L | 42 ± 22 | 41 ± 3 | 42 ± 28 | 0.63 |

| ALBI score > −2.6 (high risk) | 100 (31) | 36 (26) | 64 (34) | 0.12 |

| Prothrombin level, % of normal | 94 ± 21 | 93 ± 24 | 94 ± 19 | 0.96 |

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 88 ± 282 | 70 ± 26 | 97 ± 369 | 0.35 |

| Creatinine > 117 µmol/L | 13 (3.9) | 3 (2.2) | 10 (5.3) | 0.15 |

Qualitative variables are given as number (%); continuous variables are given as mean ± SD.

Cystadenocarcinoma (1 case) and primary sarcoma of the liver (2 cases).

ALBI, Albumin-Bilirubin; ASA, American Society of Anaesthesiology; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CRM, colorectal metastases; NCNNE, noncolorectal non neuroendocrine metastases; NEM, neuroendocrine metastases.

TABLE 2.

Intraoperative Events (326 Hepatectomies)

| Overall 2016–2019, n = 326 | Period 1 2016–2017, n = 138 (42%) | Period 2 2018–2019, n = 188 (58%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of hepatectomy | ||||

| Anatomical resection | 164 (50.3) | 68 (49.3) | 96 (51.1) | 0.75 |

| Major hepatectomy | 79 (24.2) | 39 (28.3) | 40 (21.3) | 0.15 |

| Extended right or left hepatectomy | 11 (3.3) | 1 (0.7) | 10 (5.3) | 0.02 |

| Central hepatectomy | 8 (2.5) | 0 (-) | 8 (4.3) | 0.01 |

| Resection of caudate lobe* | 19 (5.8) | 5 (3.6) | 14 (7.4) | 0.15 |

| Combined procedures | ||||

| Ablation in the remnant liver | 46 (14.1) | 41 (29.7) | 5 (2.7) | <0.0001 |

| Multiple hepatectomies | 51 (15.6) | 22 (15.9) | 29 (15.4) | 0.90 |

| Vascular reconstruction | 12 (3.7) | 1 (0.7) | 11 (5.9) | 0.02 |

| Roux-en-Y bilioenteric anastomosis | 23 (7.1) | 4 (2.9) | 19 (10.1) | 0.01 |

| Diaphragm resection | 20 (6.1) | 4 (2.9) | 16 (8.5) | 0.04 |

| Combined organ resection† | 18 (5.5) | 7 (5.1) | 11 (5.9) | 0.76 |

| Lymphadenectomy | 17 (5.2) | 3 (2.2) | 14 (7.4) | 0.03 |

| Particular techniques | ||||

| Preoperative portal vein embolization | 33 (10.1) | 16 (11.6) | 17 (9.1) | 0.45 |

| Hepatic vein embolization | 2 (0.6) | 0 (-) | 2 (1.0) | 0.22 |

| 2-stage hepatectomy | 35 (10.7) | 19 (13.8) | 16 (8.5) | 0.13 |

| Rehepatectomy | 69 (21.2) | 34 (24.6) | 35 (18.6) | 0.19 |

| Laparoscopic approach | 22 (6.7) | 2 (1.4) | 20 (10.6) | 0.001 |

| Vascular control and transfusion | ||||

| No clamping | 155 (47.5) | 70 (50.7) | 85 (45.2) | 0.40 |

| Clamping, any type | 171 (52.5) | 68 (49.3) | 103 (54.8) | 0.40 |

| Duration of ischemia, min | 31 ± 20 | 29 ± 16 | 32 ± 22 | 0.29 |

| Transfusion, yes | 60 (18.4) | 15 (10.9) | 45 (23.9) | 0.003 |

| Units of red blood cells transfused | 1.7 ± 1.7 | 1.4 ± 1.3 | 1.8 ± 1.9 | 0.42 |

| Complexity of hepatectomy | ||||

| Level of complexity | 0.0008 | |||

| High | 26 (8.0) | 4 (2.9) | 22 (11.7) | |

| Medium | 70 (21.5) | 40 (29.0) | 30 (16.0) | |

| Low | 230 (70.5) | 94 (68.1) | 136 (72.3) | |

Qualitative variables are given as the number (%); continuous variables are given as the means ± standard deviations.

Partial or complete.

Colorectal, small bowel, and adrenal gland.

Five composite criteria were measured: the American Society of Anesthesiologists score (ASA), the albumin-bilirubin (ALBI) score,27 the complexity of surgery, the CCI,28 and the textbook outcome. The ALBI score and CCI were obtained using online calculators.

Liver resections were classified according to Couinaud segmentation. Every innovation introduced during period 2 for complex procedures followed the appropriate process principles.29 The complexity of each procedure was retrospectively graded (low, intermediate, or high) as per Lee et al.30 In brief, the latter rates the difficulty of various open, anatomic liver resections on a scale of 1 to 10. Low complexity (mean difficulty: 1.37 to 2.01): peripheral wedge resection, left lateral sectionectomy; medium complexity (mean difficulty: 4.24 to 6.24): left hepatectomy with or without caudate resection, right hepatectomy, right posterior sectionectomy, isolated caudate resection, right trisectionectomy; high complexity (mean difficulty: 6.68 to 8.28): right anterior sectionectomy, middle hepatectomy, left trisectionectomy with or without caudate resection.

Morbidity and Mortality Were Assessed Within 90 Days of the Index Operation for Hepatectomy

Complications were classified according to acknowledged or consensus definitions.6 Severe morbidity was defined by a CCI score ≥26.2, which is defined by one complication of Clavien-Dindo grade IIIa.31 A textbook outcome (TBO)32, 33 was achieved when all 5 of the following parameters were fulfilled: the absence of perioperative transfusion, no major postoperative complications (CCI < 26.2), no mortality within 90 days or during the hospital stay, and hospital stay < the 50th percentile of the total cohort (≤9 days). R0 resection was not included in the definition of TBO because the present series included benign tumors and various malignant tumors with inconsistent prognostic value of this variable. Readmission was not recorded in the data file and could not be included in the definition of TBO. Whether the patients were operated on fully or partially by the young faculty members or the residents under the supervision of the senior surgeon was prospectively recorded. The number of patients who were sent abroad for surgery was available during period 2 only.

Statistical Analysis

The study protocol was designed according to the ethics guidelines of the 1975 Declaration of Helsinki. The present report complies with the standardized guidelines endorsed by the STROBE consortium.34

Continuous variables are given as the means ± SDs and were compared with a Mann-Whitney test. Qualitative variables are reported as n (%) and were compared with Pearson’s X2 or Fisher exact test, as appropriate. All statistical tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered significant. Independent predictors of severe morbidity were identified by multivariable analysis using the Cox proportional hazards model. To analyze the trends in clinic visits, liver resections, surgeries performed by residents/young faculty members, academic production, the study period was divided into 2 halves: period 1 corresponded to 2016–2017, before, and period 2 corresponded to 2018–2019, after the implementation of the new HPB surgery program. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics 23.

RESULTS

Study Population and Intraoperative Data

The study population comprised 326 consecutive hepatectomies performed during the 4-year study period. Patient demographics and tumor characteristics; and details of the intraoperative events and the complexity of hepatectomy are detailed in Tables 1 and 2, respectively.

Postoperative Outcomes

Morbidity

Details of the postoperative complications and mortality in the entire study population and stratified by the study period are shown in Table 3. Overall, complications occurred following 153 hepatectomies (morbidity rate = 46.9%). The mean postoperative CCI score was 16.2 ± 23.2, and severe morbidity (CCI ≥ 26.2) occurred after 90 (27.6%) hepatectomies.

TABLE 3.

Ninety-day Postoperative Outcomes (326 Hepatectomies)

| Overall 2016–2019, n = 326 | Period 1 2016–2017, n = 138 (42%) | Period 2 2018–2019, n = 188 (58%) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 90-d mortality | 10 (3.1) | 3 (2.2) | 7 (3.7) | 0.42 |

| Overall morbidity | 153 (46.9) | 48 (34.8) | 105 (55.9) | 0.0002 |

| Severity of complications | 0.003 | |||

| None or minor (grade I–II) | 58 (79.1) | 120 (87.0) | 138 (73.4) | |

| Major (grade III–IV) | 68 (20.9) | 18 (13.0) | 50 (26.6) | |

| CCI | 16.2 ± 23.2 | 10.9 ± 19 | 20.1 ± 24.9 | 0.0003 |

| CCI ≥ 26.2 | 90 (27.6) | 25 (18.1) | 65 (34.6) | 0.001 |

| Postoperative transfer to ICU | 40 (12.3) | 8 (5.8) | 32 (17.0) | 0.002 |

| ICU stay, d | 7 ± 6 | 7 ± 8 | 6 ± 6 | 0.82 |

| Hospital stay, d | 13 ± 13 | 10 ± 10 | 14 ± 14 | 0.002 |

| Textbook outcome, yes | 169 (51.8) | 95 (68.8) | 74 (39.4) | <0.0001 |

Qualitative variables are given as the number (%); continuous variables are given as the means ± standard deviations.

CCI, comprehensive complication index; ICU, intensive care unit.

Mortality

Postoperative 90-day mortality occurred in 10 patients (mortality rate = 3.1%), within a median time to death of 15 days (range, 4–29 days).

Durations of Stay

Direct transfer from the operating room to the ICU was needed for 40 (12.3%) patients, who then stayed for a duration of 7 ± 6 days. The mean duration of hospitalization was 13 ± 13 days.

Comparisons of Period 1 With Period 2

Trends in Clinic Visits

A total of 3327 clinic visits took place during the study period, with 1239 (37.2%) during period 1 and 2088 (62.8%) during period 2, resulting in an increase of 68.5% in clinic volume. The new clinic dedicated to primary liver tumors generated 778 visits during period 2 [ie, 91.6% (778/849) of the increased in the total number of visits]. This new clinic took place in the hepatology department that do not take in charge secondary tumors. This might explain why the number of LMCRC did not increase during period 2. The data file could not provide the proportion of new patient visits by time period. However, taking into account the increased workload, this number mathematically increased during period 2.

Trends in Resectability

During period 2, 15 patients with a malignant tumor were deemed nonresectable by the medical oncologists/hepatologists, but resectable by the senior surgeon. All these cases were operated and resected. These 15 cases represented 8% (8/188) of the total workload during this period. As already stated, this information was not available for period 1. During period 2, 2 patients had to travel abroad for liver surgery.

Patients and Tumor Characteristics

A total of 138 liver resections were performed during period 1, and 188 during period 2, which was an increase of 36% (Table 1). The proportion of patients with ASA score ≥ 3 was higher during period 2 than during period 1 (P < 10−4). The proportion of resections for metastatic liver cancer was higher during period 1 (P = 0.0003), whereas the proportion of resections for primary liver cancer was higher during period 2 (P = 0.004). All other relevant variables pertaining to patient and tumor characteristics were not different between the 2 periods.

Liver Resections

As noted in Table 2, the proportion of major liver resections was not different during the 2 periods (P = 0.15). The complexity score of liver resections was, however, higher during period 2 (P = 0.0008).

Radiofrequency ablation of lesions in the remaining liver was more common during period 1 (P < 10−4). A laparoscopic approach was used in 20 (10.6%) patients during period 2 and in 1 (1.4%) patient during period 1 (P = 0.001). The need for the transfusion of red blood cells was greater during period 2 (P = 0.003). All other relevant variables pertaining to intraoperative events were not different between the 2 periods.

Morbidity

The rates of overall morbidity and severe morbidity (CCI ≥ 26.2) during period 2 were higher than those during period 1 (P < 10−3 and P = 0.001, respectively, Table 3). As shown in Table 4, the independent predictors of severe morbidity were age ≥75 years (OR 3.8, P = 0.007), multiple hepatic resections (OR 3.9, P = 0.02), bilioenteric anastomosis (OR 28.6, P = 0.005), combined organ resection (OR 47.6, P < 10−4), and the need for transfusion (OR 5.4, P = 0.0001). Operation during period 2 was not an independent predictor of severe morbidity in multivariable analysis.

TABLE 4.

Predictors of a Comprehensive Complication Index ≥ 26.2

| Variable | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | P | OR | 95% CI | |

| Period 2 | 0.001 | 0.24 | ||

| Male sex | 0.31 | |||

| Age ≥ 75 y | 0.06 | 0.007 | 3.8 | 1.4–10.1 |

| ASA score ≥ III | 0.002 | 0.07 | ||

| Cirrhosis | 0.32 | |||

| Malignancy | 0.91 | |||

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 0.59 | |||

| Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma | 0.51 | |||

| Perihilar cholangiocarcinoma | <0.0001 | 0.99 | ||

| Gallbladder carcinoma | 0.55 | |||

| Other primary | 0.28 | |||

| CRM | 0.009 | 0.92 | ||

| NEM | 0.31 | |||

| NCNNE | 0.93 | |||

| Bilirubin > 34 µmol/L | <0.0001 | 0.62 | ||

| AST, IU/L | 0.08 | 0.83 | ||

| Albumin, g/L | 0.27 | |||

| ALBI score > −2.6 (high risk) | 0.15 | |||

| Prothrombin level, % of norm | 0.42 | |||

| Platelet count | 0.56 | |||

| Creatinine, µmol/L | 0.07 | 0.09 | ||

| Creatinine > 117 µmol/L | 0.13 | |||

| Anatomical resection | 0.004 | 0.75 | ||

| Major hepatectomy | 0.008 | 0.33 | ||

| Extended right or left hepatectomy | 0.0007 | 0.41 | ||

| Central hepatectomy | 0.15 | |||

| Resection of caudate lobe | 0.05 | 0.14 | ||

| Ablation in the remnant liver | 0.02 | 0.45 | ||

| Multiple hepatectomies | 0.08 | 0.02 | 3.9 | 1.2–12.3 |

| Vascular reconstruction | 0.0002 | 0.34 | ||

| Roux-en-Y bilioenteric anastomosis | <0.0001 | 0.005 | 28.6 | 2.8−333.3 |

| Diaphragm resection | 0.20 | |||

| Combined organ resection | 0.0001 | <0.0001 | 47.6 | 10.1−250.0 |

| Lymphadenectomy | <0.0001 | 0.34 | ||

| Preoperative portal vein embolization | 0.44 | |||

| Hepatic vein embolization | 0.38 | |||

| 2-stage hepatectomy | 0.59 | |||

| Rehepatectomy | 0.55 | |||

| Laparoscopic approach | 0.003 | 0.98 | ||

| Clamping | 0.0006 | 0.30 | ||

| High complexity of hepatectomy* | <0.0001 | 0.86 | ||

| Transfusion | <0.0001 | 0.0001 | 5.4 | 2.3−12.8 |

As per Lee et al.31

ALBI; Albumin-Bilirubin; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiology; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; CI, confidence interval; CRM, colorectal metastases; NEM, neuroendocrine metastases; NCNNE, noncolorectal nonneuroendocrine metastases; OR, odds ratio.

A direct transfer from the operating room to the ICU was more common during period 2 than during period 1 (P = 0.002). The mean duration of hospitalization was longer during period 2. A TBO occurred following 95 (68.8%) hepatectomies during period 1 compared with 74 (39.4%) during period 2 (P < 10−4).

Mortality

The 90-day mortality rates were not different (P = 0.42) between period 1 (2.2%) and period 2 (3.7%, Table 3). The small number of events precluded the identification of independent predictors of 90-day mortality.

Education and Trends in the Surgical Activity of Trainees

Young faculty members/residents performed 2/138 (0.1%) hepatectomies during period 1 and part or all (as defined) of 81/188 (43.1%) hepatectomies during period 2 (40-fold increase, P < 10−4).

The WhatsApp HPB Group, implemented during period 2, allowed the discussion of all potential candidates for surgery (indication for surgery, need for additional exploration(s), decision to postpone surgery (temporarily or definitively) and facilitated the sharing of 304 intraoperative pictures for 62 relevant cases and hundreds of bibliographic references.

No formal conference on liver surgery among the staff of various departments of the CSMC took place during period 1, whereas 11 occurred during period 2 (list available on demand).

Trends in Academic Production

No presentations were given at HPB national/international meetings with a peer selection process and two publications indexed in PubMed were produced during period 1. During period 2, 7 articles were presented and 12 articles indexed in PubMed involving the participation of at least one fellow or resident were published (6-fold increase, list available on demand).

DISCUSSION

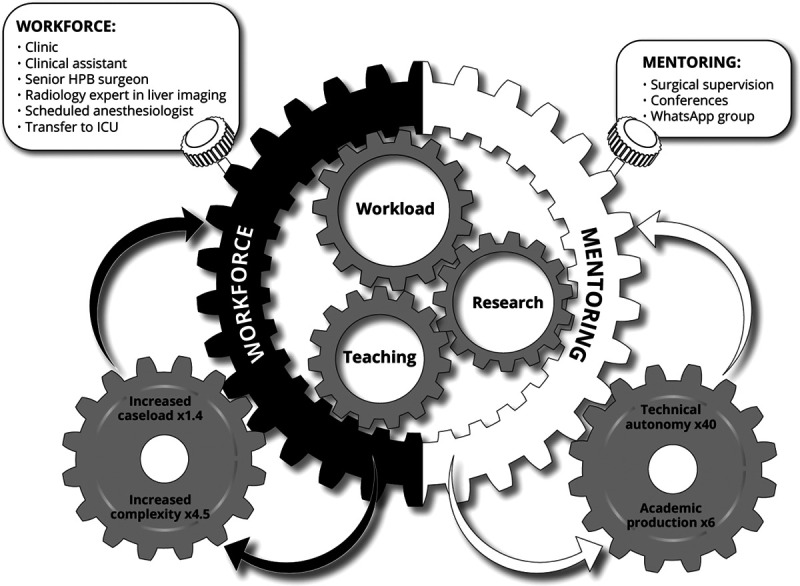

The implementation of a dedicated liver surgery program increased the number of hepatectomies by 36% within 2 years, and the number of highly complex resections performed increased 4.5-fold. The number of hepatectomies performed by the residents/young faculties and the number of published articles increased 40- and 6-fold, respectively. Below, the 3 areas of workload, teaching and research are discussed separately albeit these interact each other as the gearwheels in a clockwork mechanism (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Hallmarks of implementation of a new program of liver surgery at a university-affiliated hospital. The 3 symbiotic components of a new program: Workload, Research, and Teaching interact as the gearwheels in a clockwork mechanism. The numerous measures to wind up the mechanism are regrouped into the 2 main boxes of workforce and mentoring. The outputs of the mechanism, in a virtuous circle, fuel the above boxes.

The increased workload reported here is consistent with other scarce reports on the benefits of establishing a new HPB program, which showed 2- to 5-fold increases in the number of liver resections.22 The multifactorial causes of this increased workload were identified throughout the clinical pathway and included promotion in the community, improved availability of clinic visits (1.7-fold increase), the increased resectability rate subsequent to the presence of a senior HPB surgeon at all MDMs (8% of the workload reported here),25,35,36 conferences held within the CSMC,37 the ability to offer surgery to patients with more severe disease and those needing more complex procedures,31 and the development of the laparoscopic approach.38 It is likely that the expansion of resectability and the increased scope of the procedures performed explain the significant decrease in the performance of intraoperative radiofrequency ablation during period 2. The number of hepatectomies for primary tumors more than doubled during period 2 subsequently to the implementation of clinic visits in the department of hepatology during period 2, which generated the vast majority of the new clinic visits during the latter.

The possibility to increase the complexity of cases that could be addressed was facilitated by the improvements in the relationship with anesthesiologists,39 the use of a predefined and scheduled team of anesthesiologists,40 engagement in regular discussions with a radiologist with expertise in liver imaging41 and the fact that 1 surgeon was working part time in the ICU.42

Despite the more severe general status of the patients and the greater complexity of the procedures, operative mortality remained stable during period 2 compared to period 1, and in the lower end of the range reported in population-based surveys4,43–47 and large single-center cohort studies including the center with which the senior author of the present study was originally affiliated.6

Overall morbidity and severe morbidity were higher during period 2 than period 1. However, multivariable analysis identified the usual independent predictors of severe morbidity, and importantly did not include the period during which the surgery was performed. The above results explain why, inherent to its definition, a textbook outcome occurred less frequently during period 2.

The technical autonomy of residents/young faculty members increased during period 2. In fact, residents/young faculties performed all or part of 43% of liver resections under the supervision of the senior surgeon. Furthermore, the entire workload in the new program and the proportion handled by residents and young faculties met the reported requirements for exposure to HPB surgery for residents in general surgery48 and senior residents planning to specialize in HPB surgery,48 as well as young faculties. The safety of the involvement of younger surgeons in surgical procedures has been previously demonstrated.49 The aphorism “see one, do one, teach one” cannot be applied to liver surgery because this demanding field requires expertise in advanced open and laparoscopic procedures, familiarity with vascular surgical techniques, and the management of the preoperative evaluation of patients and their tumors and unique complications not typically seen in general surgery.50 Empiric data are needed to evaluate trainee autonomy with regard to various levels of complexity of liver resections based on a scale, such as the Zwisch scale, which has recently been used for residents in general surgery.51

The reported added value for the team and the patients due to the availability of a clinician assistant,52 the establishment of the WhatsApp Group,53 the sharing of intraoperative pictures,54 and the use of surgical and medical smartphone applications55 were observed during period 2 only. No comparisons with period 1, if ever needed, could be made. We acknowledge that the use of Whatsapp as a communication application raises compliance issues.53 However, since 2016, the end-to-end encryption of all messages for one to one communication, or one to many including text, images, and video, has resolved the data security issue.53

The formal and informal mentoring encouraged 2 senior fellows to travel abroad for fellowships in HPB surgery, and significantly increased the program’s academic production. These results build on those previously reported in this field.49,52,56–58

The dilution of a limited number of hepatectomies per year in a small area by spreading them among a large number of centers prevents the vast majority of these centers from accruing the critical workload needed to achieve optimal postoperative outcomes, ensuring readiness for independent practice among trainees and conducting sustainable research. This situation supports the regionalization of HPB surgery to synergize the acknowledged center/surgeon volume–outcome relationships.2 The regionalization of liver surgery in a region/country of reasonable size and population still should avoid overcentralization and the attendant risk of disenfranchising patients by imposing travel burden59 or excluding certain groups such as the elderly population, racial minorities, and patients with severe comorbidities43 by discouraging patient travel.44

The monocentric nature was inherent to the recruitment of a single senior surgeon by a single institution. The present report aimed at underlining the positive impacts of all leadership aspects implemented rather than the surgical personal credit of the senior author.45

HPB surgery has unequivocally reached the status of a specialty.15 As such, there needs to be development of an autonomous program whenever possible to meet all the quality indicators of care for the involved patients46 and to offer a fellowship in HPB surgery, which has been shown to have a positive impact on perioperative results.47 In this context, the present analysis is important because evidence suggests that publicly releasing performance data stimulates quality improvement measures at the hospital level.60 The development of a Center of Excellence61 together with a culture of bidirectional mentorship58 to prepare the next generation of surgeons for the future62 is the ultimate goal.

CONCLUSION

Within 2 years, the implementation of a new liver surgery program in a university-affiliated hospital filled the gap between the demand for and supply of liver surgeries, benefited the community and the development of the next generation of liver surgeons in terms of technical autonomy and academic output.

Acknowledgments

To Prof. Didier Samuel, Dean of the Faculté de Médecine Paris-Sud (Université Paris-Saclay), for his wise advice and strong support throughout this project. The senior author sincerely thanks Prof. Jan Lerut, Prof. Timothy M. Pawlik, and Prof. Thomas S. Helling for their guidance, useful critiques and enthusiastic encouragement to publish this report.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fitzmaurice C, Abate D, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national cancer incidence, mortality, years of life lost, years lived with disability, and disability-adjusted life-years for 29 cancer groups, 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study. JAMA Oncol. 2019; 5:1749–1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Peery AF, Crockett SD, Murphy CC, et al. Burden and cost of gastrointestinal, liver, and pancreatic diseases in the United States: update 2018. Gastroenterology. 2019; 156:254–272.e11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.de Haas RJ, Wicherts DA, Andreani P, et al. Impact of expanding criteria for resectability of colorectal metastases on short- and long-term outcomes after hepatic resection. Ann Surg. 2011; 253:1069–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cescon M, Vetrone G, Grazi GL, et al. Trends in perioperative outcome after hepatic resection: analysis of 1500 consecutive unselected cases over 20 years. Ann Surg. 2009; 249:995–1002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zimmitti G, Roses RE, Andreou A, et al. Greater complexity of liver surgery is not associated with an increased incidence of liver-related complications except for bile leak: an experience with 2,628 consecutive resections. J Gastrointest Surg. 2013; 17:57–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Azoulay D, Bhangui P, Pascal G, et al. The impact of expanded indications on short-term outcomes for resection of malignant tumours of the liver over a 30 year period. HPB (Oxford). 2017; 19:638–648 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Scarborough JE, Pietrobon R, Bennett KM, et al. Workforce projections for hepato-pancreato-biliary surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 2008; 206:678–684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ali N, O’Rourke C, El-Hayek K, et al. Estimating the need for hepato-pancreatico-biliary surgeons in the USA. HPB (Oxford). 2015; 17:352–356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Raoof M, Haye S, Ituarte PHG, et al. Liver resection improves survival in colorectal cancer patients: causal-effects from population-level instrumental variable analysis. Ann Surg. 2019; 270:692–700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chino F, Peppercorn JM, Rushing C, et al. Out-of-pocket costs, financial distress, and underinsurance in cancer care. JAMA Oncol. 2017; 3:1582–1584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Resio BJ, Chiu AS, Hoag JR, et al. Motivators, barriers, and facilitators to traveling to the safest hospitals in the United States for complex cancer surgery. JAMA Netw Open. 2018; 1:e184595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brooke BS, Goodney PP, Kraiss LW, et al. Readmission destination and risk of mortality after major surgery: an observational cohort study. Lancet. 2015; 386:884–895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldberg DS, French B, Forde KA, et al. Association of distance from a transplant center with access to waitlist placement, receipt of liver transplantation, and survival among US veterans. JAMA. 2014; 311:1234–1243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sheikh MR, Osman H, Butt MU, et al. Perception of training in hepatopancreatobiliary surgery among general surgery residents in the Americas. HPB (Oxford). 2016; 18:1039–1045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.D’Angelica MI, Chapman WC. HPB surgery: the specialty is here to stay, but the training is in evolution. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016; 23:2123–2125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Subhas G, Mittal VK. Training minimal invasive approaches in hepatopancreatobilliary fellowship: the current status. HPB (Oxford). 2011; 13:149–152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seshadri RM, Ali N, Warner S, et al. Training and practice of the next generation HPB surgeon: analysis of the 2014 AHPBA residents’ and fellows’ symposium survey. HPB (Oxford). 2015; 17:1096–1104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robson AJ, Parks RW. HPB fellowship training: consensus and convergence. HPB (Oxford). 2016; 18:397–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang TT, Sawhney R, Monto A, et al. Implementation of a multidisciplinary treatment team for hepatocellular cancer at a Veterans Affairs Medical Center improves survival. HPB (Oxford). 2008; 10:405–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lau K, Salami A, Barden G, et al. The effect of a regional hepatopancreaticobiliary surgical program on clinical volume, quality of cancer care, and outcomes in the Veterans Affairs system. JAMA Surg. 2014; 149:1153–1161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yopp AC, Mansour JC, Beg MS, et al. Establishment of a multidisciplinary hepatocellular carcinoma clinic is associated with improved clinical outcome. Ann Surg Oncol. 2014; 21:1287–1295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granger SR, Glasgow RE, Battaglia J, et al. Development of a dedicated hepatopancreaticobiliary program in a university hospital system. J Gastrointest Surg. 2005; 9:891–895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Riva N, Lauw MN. Benefits and challenges of going abroad for research or clinical training. J Thromb Haemost. 2016; 14:1683–1684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McClintock NC, Gray KE, Neville AL, et al. Factors associated with general surgery residents’ decisions regarding fellowship and subspecialty stratified by burnout and quality of life. Am J Surg. 2019; 218:1090–1095 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Homayounfar K, Bleckmann A, Helms HJ, et al. Discrepancies between medical oncologists and surgeons in assessment of resectability and indication for chemotherapy in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2014; 101:550–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smilowitz NR, Berger JS. Perioperative cardiovascular risk assessment and management for noncardiac surgery: a review. JAMA. 2020; 324:279–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Andreatos N, Amini N, Gani F, et al. Albumin-bilirubin score: predicting short-term outcomes including bile leak and post-hepatectomy liver failure following hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 2017; 21:238–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Slankamenac K, Graf R, Barkun J, et al. The comprehensive complication index: a novel continuous scale to measure surgical morbidity. Ann Surg. 2013; 258:1–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Minamikawa K, Okumura A, Kokudo N, et al. Regulation on introducing process of the highly difficult new medical technologies: a survey on the current status of practice guidelines in Japan and overseas. Biosci Trends. 2019; 12:560–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee MKt, Gao F, Strasberg SM. Completion of a liver surgery complexity score and classification based on an international survey of experts. J Am Coll Surg. 2016; 223:332–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cloyd JM, Mizuno T, Kawaguchi Y, et al. Comprehensive complication index validates improved outcomes over time despite increased complexity in 3707 consecutive hepatectomies. Ann Surg. 2020; 271:724–731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marshall MN, Shekelle PG, Leatherman S, et al. The public release of performance data: what do we expect to gain? A review of the evidence. JAMA. 2000; 283:1866–1874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Metcalfe D, Rios Diaz AJ, Olufajo OA, et al. Impact of public release of performance data on the behaviour of healthcare consumers and providers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018; 9:CD004538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, et al. ; STROBE initiative. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2007; 147:W163–W194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Choti MA, Thomas M, Wong SL, et al. Surgical resection preferences and perceptions among medical oncologists treating liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016; 23:375–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Aubin JM, Bressan AK, Grondin SC, et al. Assessing resectability of colorectal liver metastases: how do different subspecialties interpret the same data? Can J Surg. 2018; 61:14616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oxenberg J, Papenfuss W, Esemuede I, et al. Multidisciplinary cancer conferences for gastrointestinal malignancies result in measureable treatment changes: a prospective study of 149 consecutive patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015; 22:1533–1539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ciria R, Gomez-Luque I, Ocaña S, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing the short- and long-term outcomes for laparoscopic and open liver resections for hepatocellular carcinoma: updated results from the European Guidelines Meeting on Laparoscopic Liver Surgery, Southampton, UK, 2017. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019; 26:252–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cooper JB. Critical role of the surgeon-anesthesiologist relationship for patient safety. J Am Coll Surg. 2018; 227:382–386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doll D, Kauf P, Wieferich K, et al. Implications of perioperative team setups for operating room management decisions. Anesth Analg. 2017; 124:262–269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chung R, Rosenkrantz AB, Shanbhogue KP. Expert radiologist review at a hepatobiliary multidisciplinary tumor board: impact on patient management. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2020; 45:3800–3808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Misseri G, Cortegiani A, Gregoretti C. How to communicate between surgeon and intensivist? Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2020; 33:170–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gani F, Azoulay D, Pawlik TM. Evaluating trends in the volume-outcomes relationship following liver surgery: does regionalization benefit all patients the same? J Gastrointest Surg. 2017; 21:463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu JB, Berian JR, Liu Y, et al. Procedure-specific trends in surgical outcomes. J Am Coll Surg. 2018; 226:30–36.e4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel VM, Warren O, Humphris P, et al. What does leadership in surgery entail? ANZ J Surg. 2010; 80:876–883 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dixon E, Armstrong C, Maddern G, et al. Development of quality indicators of care for patients undergoing hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer using a Delphi process. J Surg Res. 2009; 156:32–38.e1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Altieri MS, Yang J, Yin D, et al. Presence of a fellowship improves perioperative outcomes following hepatopancreatobiliary procedures. Surg Endosc. 2017; 31:2918–2924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Osman H, Parikh J, Patel S, et al. Are general surgery residents adequately prepared for hepatopancreatobiliary fellowships? A questionnaire-based study. HPB (Oxford). 2015; 17:265–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kiran RP, Ahmed Ali U, Coffey JC, et al. Impact of resident participation in surgical operations on postoperative outcomes: National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. Ann Surg. 2012; 256:469–475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Helling TS, Khandelwal A. The challenges of resident training in complex hepatic, pancreatic, and biliary procedures. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008; 12:153–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.George BC, Bohnen JD, Williams RG, et al. ; Procedural Learning and Safety Collaborative (PLSC). Readiness of US general surgery residents for independent practice. Ann Surg. 2017; 266:582–594 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coverdill JE, Shelton JS, Alseidi A, et al. The promise and problems of non-physician practitioners in general surgery education: results of a multi-center, mixed-methods study of faculty. Am J Surg. 2018; 215:222–226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mars M, Scott RE. WhatsApp in clinical practice: a literature review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2016; 231:82–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gaujoux S, Ceribelli C, Goudard G, et al. Best practices to optimize intraoperative photography. J Surg Res. 2016; 201:402–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kulendran M, Lim M, Laws G, et al. Surgical smartphone applications across different platforms: their evolution, uses, and users. Surg Innov. 2014; 21:427–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Phitayakorn R, Petrusa E, Hodin RA. Development and initial results of a mandatory department of surgery faculty mentoring pilot program. J Surg Res. 2016; 205:234–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chaney AJ, Harnois DM, Musto KR, et al. Role development of nurse practitioners and physician assistants in liver transplantation. Prog Transplant. 2016; 26:75–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Choi AMK, Moon JE, Steinecke A, et al. Developing a culture of mentorship to strengthen academic medical centers. Acad Med. 2019; 94:630–633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sheetz KH, Chhabra KR, Smith ME, et al. Association of discretionary hospital volume standards for high-risk cancer surgery with patient outcomes and access, 2005-2016. JAMA Surg. 2019; 154:1005–1012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fung CH, Lim YW, Mattke S, et al. Systematic review: the evidence that publishing patient care performance data improves quality of care. Ann Intern Med. 2008; 148:111–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Elrod JK, Fortenberry JL, Jr. Centers of excellence in healthcare institutions: what they are and how to assemble them. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017; 17(suppl 1):425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zimlichman E, Afek A, Kahn CN, et al. The future evolution of hospitals. Isr Med Assoc J. 2019; 21:163–164 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]