Supplemental Digital Content is available in the text.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, liver metastases, RECIST, resection, systemic therapy, tumor response assessment, tumor volume

Abstract

Objectives:

Compare total tumor volume (TTV) response after systemic treatment to Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST1.1) and assess the prognostic value of TTV change and RECIST1.1 for recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with colorectal liver-only metastases (CRLM).

Background:

RECIST1.1 provides unidimensional criteria to evaluate tumor response to systemic therapy. Those criteria are accepted worldwide but are limited by interobserver variability and ignore potentially valuable information about TTV.

Methods:

Patients with initially unresectable CRLM receiving systemic treatment from the randomized, controlled CAIRO5 trial (NCT02162563) were included. TTV response was assessed using software specifically developed together with SAS analytics. Baseline and follow-up computed tomography (CT) scans were used to calculate RECIST1.1 and TTV response to systemic therapy. Different thresholds (10%, 20%, 40%) were used to define response of TTV as no standard currently exists. RFS was assessed in a subgroup of patients with secondarily resectable CRLM after induction treatment.

Results:

A total of 420 CT scans comprising 7820 CRLM in 210 patients were evaluated. In 30% to 50% (depending on chosen TTV threshold) of patients, discordance was observed between RECIST1.1 and TTV change. A TTV decrease of >40% was observed in 47 (22%) patients who had stable disease according to RECIST1.1. In 118 patients with secondarily resectable CRLM, RFS was shorter for patients with less than 10% TTV decrease compared with patients with more than 10% TTV decrease (P = 0.015), while RECIST1.1 was not prognostic (P = 0.821).

Conclusions:

TTV response assessment shows prognostic potential in the evaluation of systemic therapy response in patients with CRLM.

INTRODUCTION

Patients with colorectal cancer develop metastases in the majority of cases, which are confined to the liver in about 30%.1,2 For patients with colorectal liver-only metastases (CRLM), surgical resection and/or local ablative therapy is considered to be the only potentially curative treatment, with 5-year survival rates of 40% (range 16%–71%).3–5 Unfortunately, only 20% of patients diagnosed with CRLM present with resectable disease.5,6 Patients with initially unresectable CRLM, however, can become eligible for local treatment after downsizing by systemic therapy, allowing secondary resections with comparable survival rates as primary resections.7–9 Accurate response evaluation and classification is crucial to these patients, but also to patients receiving palliative treatment, as the effect of initial treatment often determines the following treatment strategy.10,11

Efficacy of systemic therapy is most commonly measured on computed tomography (CT) scans according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST1.1).12,13 If RECIST1.1 is used, response is measured manually by radiologists and expressed as diameter change in a maximum of 2 selected target lesions per affected organ.12 Despite that RECIST1.1 is most commonly applied for response evaluation, the validity of RECIST1.1 has been questioned.14,15 Manual measurements are vulnerable to subjectivity, thus RECIST1.1 is hampered by inter- and intraobserver variability.16,17

More importantly, RECIST1.1 ignores potential valuable information about tumor volume and grayscale values provided by modern imaging techniques, as it only includes unidimensional size changes (diameter) of just 2 target lesions per organ.18,19 In addition, the RECIST1.1 response category of stable disease is limited by its very broad range (30% decrease to 20% increase in sum of diameters), potentially grouping together patients with different prognoses.12 RECIST1.1 was created acknowledging time and technology constraints of cross-sectional imaging at that time.13 However, due to advances in diagnostic imaging and computer techniques over the past years, possibilities have evolved to measure 3-dimensional (3D) volumes of tumors or total tumor volume (TTV).20–22 Especially for patients with multiple CRLM, TTV assessment could represent a more complete evaluation of tumor burden, as the 3D effect on all tumors is considered. TTV already showed potential as predictor of survival and hepatic recurrence in patients with resectable CRLM.22

Nevertheless, consensus regarding response criteria for volume assessment are lacking, as different thresholds to define response of tumor volume are being used based on tumor shape.13,21,23 Guidelines for volumetric assessment within RECIST1.1 state that thresholds are based on a spherical shape of a tumor, assuming that tumors are perfectly round objects.13 Other studies based their criteria on the ellipsoid shape of tumors.19,21,23 Both types of criteria were based on the assessment of 2 target lesions only and not on the assessment of the total tumor burden. Currently, no criteria for TTV response assessment exist and it is therefore difficult to compare TTV response to RECIST1.1. As a result, it remains unclear if TTV response assessment could potentially lead to different treatment strategies.

This study aims to compare TTV response after systemic treatment to RECIST1.1 and to assess the prognostic value of TTV and RECIST1.1 for recurrence-free survival (RFS) in patients with initially unresectable CRLM undergoing induction systemic treatment.

METHODS

Study Population

All patients registered between November 2014 and August 2018 from the ongoing multicenter randomized clinical trial of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group, CAIRO5 (NCT02162563) were selected for this study.24 The ongoing CAIRO5 trial aims to select the optimal systemic treatment strategy for patients with initially unresectable CRLM. In this trial, patients are randomized between different systemic therapy combinations based on primary tumor site and RAS and BRAF gene mutations. Patients are evaluated for resectability at baseline and during systemic treatment by an expert panel consisting of hepatobiliary surgeons and radiologists, using a digital online platform particularly created for this trial (ALEA FormsVision BV, Abcoude, The Netherlands).24 Uniform criteria for (un)resectability were applied for this study.24,25 All patients signed a written consent form and the study was conducted according to the ethical standards of the Helsinki Declaration of 1975. The following patient data were collected: patients’ baseline characteristics, including demographics, genetic mutation status (RAS/BRAF) and serum markers (carcinoembryonic antigen [CEA] and lactate dehydrogenase [LDH] level), medical images, radiology reports, and study outcome measures, including resection rate and RFS. Liver segments were classified according to Couinaud and Foie.26 Patients with Fong risk scores ranging between 0 and 2 points were categorized as low-risk score and patients with 3 to 5 points as high-risk score.27

Imaging

The CAIRO5 dataset used for the present research consisted of contrast-enhanced thorax-abdomen CT scans at baseline and subsequently every 2 months during systemic therapy. All scans were performed in 1 of the 54 centers responsible for inclusion, resulting in difference in quality of scans. Every baseline and follow-up CT scan was evaluated by one of the radiologists from the expert radiology panel, consisting of 5 radiologists, for tumor response analysis according to RECIST1.1 on a digital platform (ALEA FormsVision BV, Abcoude, The Netherlands). Use of additional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography scans was at the discretion of the local treatment team. Based on the available imaging scans and accompanying radiology reports, the hepatobiliary surgeon expert panel assessed resectability every 8 weeks during systemic therapy, according to predefined criteria.24,25 In the current study, only contrast-enhanced abdominal CT scans in the portal-venous phase were included.

Data Processing

Pre- and post-treatment CT scans from the CAIRO5 trial were used for semiautomatic segmentation in the Tumor Tracking Modality of IntelliSpace Portal 9.0 (Philips Medical Systems, Best, The Netherlands), which is Conformité Européene (CE) certified software. First, the liver and the CRLM of all included patients were segmented by 2 trained members of the research team (N.J.W. and S.P.) with the use of radiology reports from the CAIRO5 trial. All present CRLM on CT scans were segmented, including potential new lesions in the follow-up scan. Lesions were roughly outlined, which resulted in a semiautomatic contour or region of interest based on differences in density and were subsequently manually adjusted in every CT slice. Afterward, all segmentations were adjusted and verified by a radiologist expert in abdominal imaging (J.-H.T.M.v.W.). Segmentation is the delineation of structures (eg, tumors) on diagnostic imaging, resulting in 3D contours of these structures. The 3D segmentations and related CT scans were combined to create grayscale segmentations on the SAS analytical platform (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Quantification of Volume

TTV was calculated before and after systemic therapy in the SAS analytical platform using the “quantifyBioMedImages” action.28 This action was specially developed by SAS and is not yet CE approved for use in clinical practice. This action calculates TTV directly out of the tumor segmentation from all CRLM present in the liver. A CT scan is built up by voxels, the 3D equivalent of a pixel, each containing a gray value. First the “quantifyBioMedImages” action determined the volume of the box that one voxel represents. This was done by multiplying the length in the X, Y, and Z direction of this box. These lengths are extracted from the pixel spacing and slice thickness attributes of the DICOM file, which are dependent of the type and settings of the CT scanner.29 After the volume of this box was calculated, the number of voxels included in the tumor segmentation were counted. Multiplying this number of voxels with the volume that one voxel represents, resulted in the TTV. The volume of the liver was measured in the same manner. For each patient, the change in TTV or delta TTV before and after systemic therapy was measured. In addition, the percentage TTV of the total liver volume, including TTV was calculated before and after therapy.

Tumor Response According to RECIST1.1

Tumor response to systemic treatment was assessed routinely according to RECIST1.1 by the radiologists of the CAIRO5 expert panel.25 Two target lesions were selected, and the longest diameter of both lesions were measured. The sum of diameters at baseline was used as reference for further response assessment. RECIST1.1 classification criteria for objective response were defined as complete response (disappearance of all target lesions), partial response (at least 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of target lesions), progressive disease (at least 20% increase in the sum of diameters of target lesions, including an absolute increase of 5 mm in diameter, or appearance of one or more new lesions), and stable disease (neither progressive disease or partial/complete response).12

TTV Response Groups

TTV response groups were determined based on the following thresholds: 10%, 20%, 40% increase or decrease in TTV. This resulted in the following TTV response groups:

- 10% thresholds: response (at least 10% decrease in TTV), progression (at least 10% increase in TTV), stable disease (less than 10% change in TTV from baseline).

- 20% thresholds: response (at least 20% decrease in TTV), progression (at least 20% increase in TTV), stable disease (less than 20% change in TTV from baseline).

- 40% thresholds: response (at least 40% decrease in TTV), progression (at least 40% increase in TTV), stable disease (less than 40% change in TTV from baseline).

Survival Analysis

Patients undergoing local therapy (complete resection of CRLM or successful ablative therapy, or a combination of both) after successful downsizing of CRLM by systemic therapy were included for RFS analysis. Patients who did not undergo local therapy or underwent an incomplete resection were excluded. Complete resection was defined as R0 or R1 resection. R0 resection indicates a microscopically tumor margin-negative resection, in which no microscopic tumor cells have remained in the resection margins, and R1 resection was defined as the removal of all macroscopic disease, but with margins microscopically positive for tumor cells (<1 mm of the margin). RFS was calculated from the date of surgery until progression of disease, defined as new metastases detected on the CT scan, or death. In case of R0 or R1 resection, the follow-up was performed until disease progression according to the protocol and current national guideline: CT scan of the liver every 6 months for 2 years, then every 12 months up to 5 years after surgery.30 RFS was compared between response groups based on change in TTV and RECIST1.1. For the RFS analysis, the response groups were dichotomized into 2 groups per threshold (10%, 20%, 40%) and per RECIST1.1 classification. As a result, the following response groups were compared: response (equal to and more than 10% TTV decrease) versus stable/progressive (less than 10% TTV decrease), response (equal to and more than 20% TTV decrease) versus stable/progressive (less than 20% TTV decrease), response (equal to and more than 40% TTV decrease) versus stable/progressive (less than 40% TTV decrease), RECIST1.1 response versus RECIST1.1 stable/progression.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS Studio (version 5.2, SAS Viya release V.03.05, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). Continuous variables were displayed as median with interquartile range (IQR) or range and categorical variables by number with percentages. TTV response was reported as continuous and categorical variables. TTV response and RECIST1.1 were compared by calculating the discordant patients. In addition, survival curves were generated separately for RECIST1.1 and TTV response using the Kaplan-Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Survival analysis was considered statistically significant with a P value <0.05. The relation between baseline parameters and baseline TTV was assessed using univariable and multivariable linear regression models, with backward elimination. Categorical variables were compared between different TTV response groups with χ2 test, and continuous variables with Kruskal-Wallis test. The Bonferroni correction was applied for multiple testing for the linear regression analyses and for the comparison of the baseline parameters between the TTV response groups (critical P value = 0.05/13 = 0.004).

RESULTS

Study Population

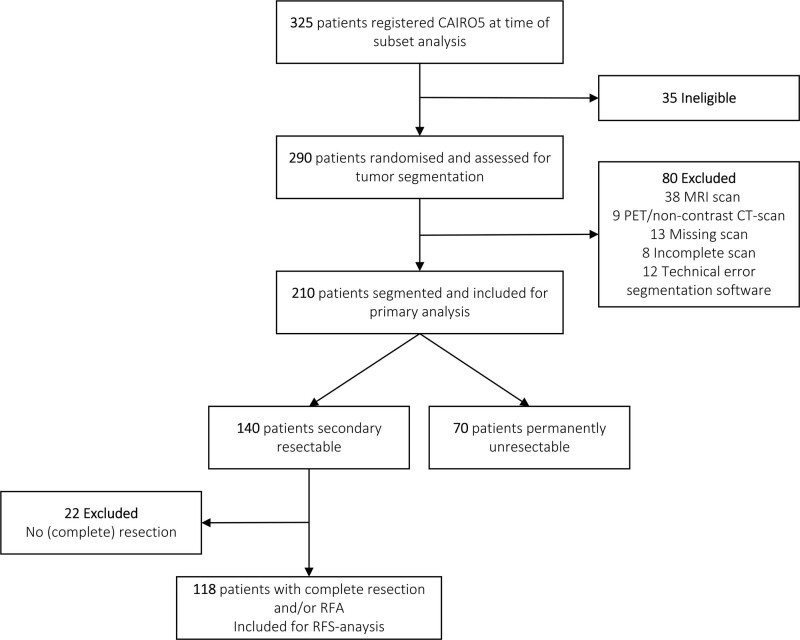

Between June 2014 and August 2018, 325 patients were registered and screened for eligibility for the CAIRO5 trial. Of these patients, 291 were randomized for the CAIRO5 study and after assessment for eligibility for tumor segmentation, a total of 210 patients were included in the current study. Most common reason for exclusion was use of MRI scan (Fig. 1). In primary analysis, TTV assessment was compared with RECIST1.1 using baseline and first follow-up CT scan. On 420 evaluated baseline and first follow-up CT scans, a total of 7280 CRLM were segmented. Baseline characteristics of the included patients are shown in Table 1. Median age was 62 years (IQR, 55–70) and one-third of the patients was female. Most patients had a left-sided primary colon tumor and synchronous metastases. RAS/BRAF mutation was present in 59% of the patients. The median number of metastases at baseline was 11 (IQR, 7–22) and 93% of patients had bilobar metastatic disease, with a median of 6 (IQR, 4–7) liver segments involved.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of patient inclusion. PET indicates positron emission tomography; RFA, radio-frequency ablation.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

| Baseline Parameters | Total Cohort N = 210 |

|---|---|

| Age, y | |

| Median [IQR] | 62 [55.0–70.0] |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 138 (65.7) |

| Female | 72 (34.3) |

| Site of primary tumor, n (%) | |

| Right colon | 56 (34.3) |

| Left colon or rectum | 154 (65.7) |

| pN status primary tumor, n (%) | |

| Negative | 51 (24.3) |

| Positive | 69 (32.9) |

| Missing | 90 (42.9) |

| Time to metastases, n (%) | |

| Synchronous | 185 (88.1) |

| Metachronous | 25 (11.9) |

| Mutational status, n (%) | |

| RAS mutation | 111 (52.9) |

| BRAFV600E mutation | 12 (5.7) |

| RAS and BRAF wild type | 87 (41.4) |

| Baseline serum LDH level | |

| Median [IQR] | 292 [209–530] |

| Baseline serum CEA level | |

| Median [IQR] | 44 [11–258] |

| Number of liver metastases | |

| Median [IQR] | 11 [7–22] |

| Diameter of largest metastasis, mm | |

| Median [IQR] | 41.5 [28–71] |

| Number of liver segments involved | |

| Median [IQR] | 6 [4–7] |

| Distribution of liver metastases, n (%) | |

| Unilobar | 15 (7.1) |

| Bilobar | 195 (92.5) |

| Fong risk score, n (%) | |

| Low | 10 (4.8) |

| High | 200 (95.2) |

| Induction systemic therapy, n (%) | |

| FOLFOX/FOLFIRI and bevacizumab | 107 (51.0) |

| FOLFOX/FOLFIRI and panitumumab | 42 (20.0) |

| FOLFOXIRI and bevacizumab | 61 (29.0) |

BRAF indicates v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B; FOLFIRI, 5-fluoracil with leucovorin and irinotecan; FOLFOX, 5-fluoracil with leucovorin and oxaliplatin; FOLFOXIRI, 5-fluoracil with leucovorin, oxaliplatin, and irinotecan; pN, nodal status; RAS, rat sarcoma oncogene.

TTV Assessment

Radiological parameters are summarized in Table 2. The median TTV at baseline was 100 cm3, ranging between 1.44 and 2530 cm3. Median TTV at first follow-up scan was 49 cm3 (range, 0.54–3827 cm3). The median change in TTV was a 47% decrease (range 92% decrease to 658% increase), with a median delta TTV of 27 cm3 decrease (range 1340 cm3 decrease to 2662 cm3 increase). The percentage TTV of the total liver volume at baseline ranged between 0.09% and 59%, with a median of 6%. The association between baseline parameters and baseline TTV was examined (Table 3). In multivariable analysis, the following parameters were independently correlated with larger TTV at baseline: serum LDH level (β = 0.310, P < 0.001), serum CEA level (β = 0.038, P = 0.001), number of liver metastases (β = 4.741, P < 0.001), and diameter of largest tumor (β = 5.770, P < 0.001).

TABLE 2.

Radiological Parameters (Baseline and First Follow-Up Scan)

| Radiological Parameters | Total CohortN = 210 |

|---|---|

| TTV | |

| TTV (cm3), median [range] | |

| Baseline | 100 [1.44–2530] |

| Follow-up 1 | 49 [0.54–3827] |

| TTV delta (cm3) | |

| Median [range] | −27 [−1340 to 2662] |

| TTV change (%) | |

| Median [range] | −47 [−92 to 658] |

| TTV percentage of liver volume, median [range] | |

| Baseline | 6 [0.09–59] |

| Follow-up 1 | 3 [0.04–65] |

| TTV response groups (TH 10%), n (%) | |

| Response | 171 (81.4) |

| Stable | 11 (5.2) |

| Progression | 28 (13.3) |

| TTV response groups (TH 20%), n (%) | |

| Response | 165 (78.6) |

| Stable | 25 (11.9) |

| Progression | 20 (9.5) |

| TTV response groups (TH 40%), n (%) | |

| Response | 125 (59.5) |

| Stable | 70 (33.3) |

| Progression | 15 (7.1) |

| RECIST1.1 | |

| Sum of TL (mm), median [range] | |

| Baseline | 72 [17–282] |

| Follow-up 1 | 54 [8–244] |

| Diameters change (%) | |

| Median [range] | −24 [−76 to 40] |

| RECIST1.1 classification, n (%) | |

| Response | 84 (40.0) |

| Stable | 110 (52.4) |

| Progression | 16 (7.6) |

TH indicates threshold; TL, target lesions.

TABLE 3.

Univariable and Multivariable Linear Regression Analyses for Relation Between Baseline Parameters and Total Tumor Volume at Baseline

| Univariable Analyses | Multivariable Analysis | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline Parameters | Patients | B | 95% CI | P Value | B | 95% CI | P Value |

| Age, y | 210 | −4.438 | −9.723 to 0.846 | 0.099 | - | ||

| Sex; female vs male | 210 | 102.577 | −6.004 to 211.158 | 0.064 | - | ||

| Sidedness primary tumor, right vs left | 210 | −23.470 | −140.942 to 94.002 | 0.694 | - | ||

| Primary tumor nodal status, positive vs negative | 120 | 109.965 | −17.362 to 237.293 | 0.090 | - | ||

| Time to metastases, synchronous vs metachronous | 210 | 224.986 | 67.490 to 382.482 | 0.005 | - | ||

| RAS/BRAF mutational status, wild-type vs mutation | 210 | 30.301 | −75,114 to 135.716 | 0.567 | - | ||

| LDH level at baseline | 210 | 0.630 | 0.530–0.731 | <0.001 | 0.310 | 0.211–0.409 | <0.001 |

| CEA level at baseline | 210 | 0.103 | 0.072–0.135 | <0.001 | 0.038 | 0.016–0.061 | 0.001 |

| Number of metastases | 210 | 5.508 | 2.433–8.582 | 0.001 | 4.741 | 2.668–6.814 | <0.001 |

| Diameter of largest metastasis (mm) | 210 | 7.925 | 6.702–9.149 | <0.001 | 5.770 | 4.545–6.994 | <0.001 |

| Number of liver segments involved | 210 | 25.642 | −2.789 to 54.073 | 0.077 | - | ||

| Location metastases, bilobar vs unilobar | 210 | −170,711 | −371.142 to 29.719 | 0.095 | - | ||

| Fong risk score, high vs low | 210 | −43.191 | −287.145 to 200.763 | 0.727 | - | ||

Critical P value = 0.004 (Bonferroni corrected). Bold values indicate statistical significance (P < 0.004).

B indicates unstandardized coefficients beta; BRAF, v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B; CI, confidence interval; RAS, rat sarcoma oncogene.

Patient Characteristics of TTV Response Groups

Patients were classified in TTV response groups based on the volumetric thresholds (Table 2). Baseline parameters were compared between the different TTV response groups using the same thresholds (Tables S1–S3, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A76). No statistically significant differences in baseline parameters were found between the different TTV response groups (Tables S1–S3, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A76). In the TTV response groups using thresholds of 40%, trends toward differences were found in age, number of liver metastases, and number of liver segments involved (Table S1, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A76). A similar trend toward difference in the number of liver segments involved was observed between the TTV response groups using thresholds of 20% (Table S2, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A76).

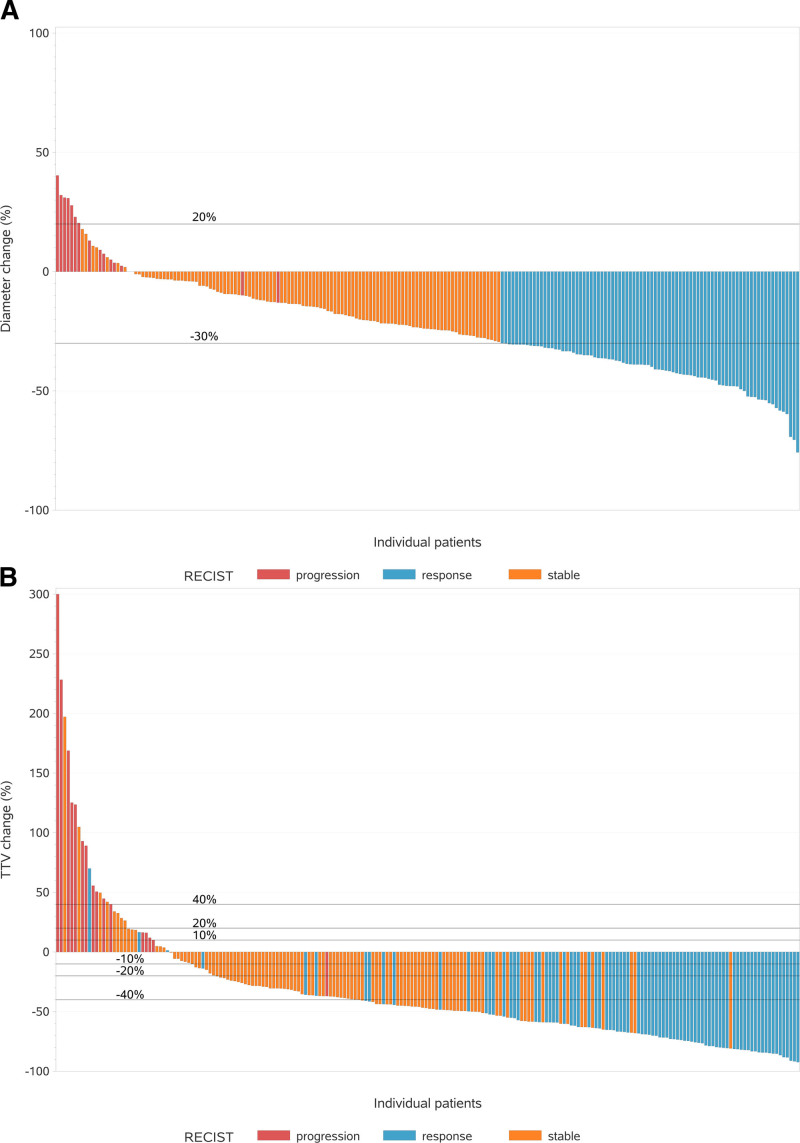

RECIST1.1 Versus TTV Change

According to RECIST1.1, CRLM were classified as having an objective response to treatment, stable disease, or progression of disease in 84 (40%), 110 (52%), and 16 (8%) patients, respectively (Table 2). Based on the 10% TTV thresholds, CRLM were classified as having response, stable disease, or progression of disease in 171 (81%), 11 (5%), and 28 (13%), respectively. According to 20% TTV thresholds, CRLM were classified as response, stable disease, or progression in 165 (79%), 25 (12%), and 20 (10%) patients, respectively. Based on the 40% TTV thresholds, CRLM were classified as having response, stable disease, or progression of disease in 125 (60%), 70 (33%), and 15 (7%) patients, respectively (Table 2). The percentual changes in sum of diameters and the change in TTV for the included patients are shown in Figure 2. The change in TTV using the different TTV thresholds was compared to RECIST1.1 (Table 4). According to the 10%, 20%, and 40% TTV thresholds, discordance between RECIST1.1 and TTV change was observed in 104 (50%), 101 (48%), and 63 (30%) patients, respectively. The majority of discordant cases were observed in the RECIST1.1 stable group for all TTV thresholds. In particular, response to treatment was more often classified when applying the TTV thresholds than following RECIST1.1. A total of 47 (22%) patients classified as stable according to RECIST1.1 experienced a TTV decrease of more than 40% (range 40%–81%). In 11 (5%) patients, TTV increased with more than 10%, while classified as stable according to RECIST1.1. In 4 (2%) of these RECIST1.1 stable patients, TTV even increased by more than 40% (range 42%–197%). The majority of cases in concordance were found in the RECIST1.1 response and RECIST1.1 progression patients. Nevertheless, 3 patients classified as responsive according to RECIST1.1 showed TTV increase of 1%, 17%, and 70%. An illustration of TTV before and after therapy for one of the discordant patients is shown in Figure S1, http://links.lww.com/AOSO/A77.

FIGURE 2.

Change in TTV and in sum of diameters (RECIST1.1). The percentual change in sum of diameters is depicted on the y axis for the individual patients on the x axis (A). In the same manner, the percentual change in TTV is depicted on the y axis for the individual patients on the x axis (B). Patients are classified according to RECIST1.1 as response, stable, and progression. One patient classified as progression by RECIST1.1 experienced a TTV increase of 658%, which is depicted as 300% TTV increase in (B).

TABLE 4.

RECIST1.1 Versus TTV Change at First Follow-Up Scan

| TTV Response Groups | RECIST1.1 Response N = 84 | RECIST1.1 Stable N = 110 | RECIST1.1 Progression N = 16 | Total Cohort N = 210 Discordant, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TTV change (TH 10%), n | ||||

| Response | 81 | 89 | 1 | |

| Stable | 1 | 10 | 0 | |

| Progression | 2 | 11 | 15 | |

| Discordant, n | 3 | 100 | 1 | 104 (50) |

| TTV change (TH 20%), n | ||||

| Response | 80 | 84 | 1 | |

| Stable | 3 | 18 | 4 | |

| Progression | 1 | 8 | 11 | |

| Discordant, n | 4 | 92 | 5 | 101 (48) |

| TTV change (TH 40%), n | ||||

| Response | 78 | 47 | 0 | |

| Stable | 5 | 59 | 6 | |

| Progression | 1 | 4 | 10 | |

| Discordant, n | 6 | 51 | 6 | 63 (30) |

TH indicates threshold.

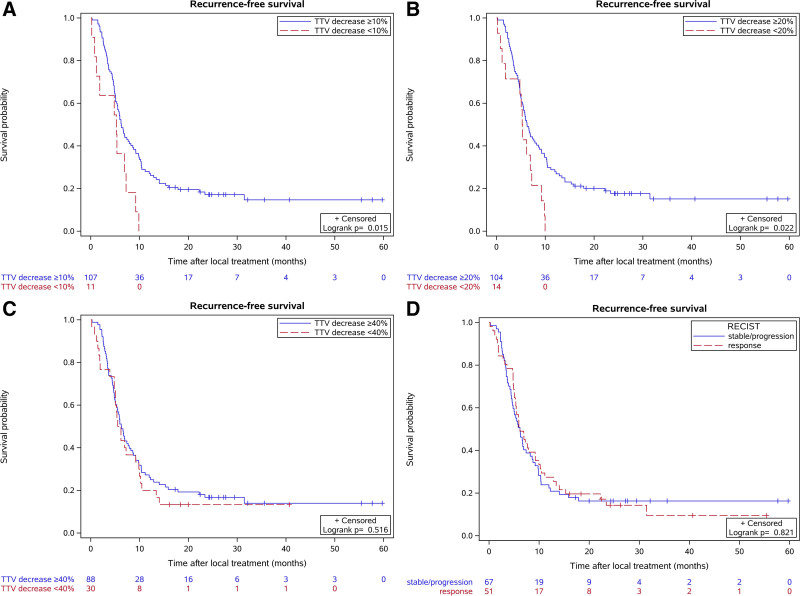

RFS Analysis

Of the 210 included patients, CRLM of 140 patients were evaluated as secondarily resectable after successful downsizing of the CRLM by the expert panel from the CAIRO5 trial. Of these patients, 118 patients underwent local therapy (complete resection of CRLM or a successful ablative therapy, or a combination of both) and were included for the RFS analysis (Fig. 2). Median follow-up of these patients was 27 months. Patients were allocated in different response groups based on change in TTV and RECIST1.1 on induction systemic treatment and RFS was compared between these groups. Patients with less than 10% TTV decrease had significantly shorter RFS compared with patients with more than 10% TTV decrease, with median RFS time of 5.3 and 6.2 months, respectively (P = 0.015). Similar results were found for patients with less than 20% TTV decrease compared with patients with more than 20% TTV decrease (median RFS 5.3 vs 6.3 months, respectively [P = 0.022]). No significant differences in RFS were found between the patients with more than 40% TTV decrease compared with patients with less than 40% decrease in TTV (P = 0.516). In addition, no significant differences in RFS were observed between responsive patients according to RECIST1.1 compared with patients with stable or progressive disease by RECIST1.1 (P = 0.821). Survival curves of the different response groups are depicted in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan Meier analysis of recurrence-free survival of patients with secondarily resectable CRLM according to TTV change and RECIST1.1. Survival curves and life tables of patients with: (A) response (equal to and more than 10% TTV decrease) versus stable/progressive (less than 10% TTV decrease), (B) response (equal to and more than 20% TTV decrease) versus stable/progressive (less than 20% TTV decrease), (C) response (equal to and more than 40% TTV decrease) versus stable/progressive (than 40% TTV decrease), (D) RECIST1.1 response versus RECIST1.1 stable/progression.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrates that change in TTV after systemic treatment differed from RECIST1.1 in 30% to 50% of CRLM patients followed by CT who were deemed unresectable according to predefined criteria. Furthermore, change in TTV was found prognostic for RFS in a subgroup of patients who became eligible for resection after induction with systemic therapy, while RECIST1.1 was not.

Since response to therapy is considered to be an important prognostic factor predicting long-term outcomes after liver surgery, difference in response assessment could potentially lead to a different treatment strategy.31 Patients with CRLM classified as responsive or stable by RECIST1.1, but experiencing TTV progression may benefit from an earlier switch of treatment regimen in daily care. In addition, patients classified stable by RECIST1.1 but showing large decrease in TTV (eg, >40%) may potentially be selected earlier for tumor resection if anatomically feasible. These findings suggest that TTV response assessment could be of added value in the evaluation of systemic therapy in a subgroup of patients with initially unresectable CRLM.

In this study, baseline TTV was positively associated with number and diameter of metastases, and serum marker levels (CEA and LDH). Since high TTV equals large tumor burden, it is not surprising that these baseline characteristics were associated. High levels of baseline CEA and LDH are prognostic risk factors for disease extensiveness and poor survival in patients with CRLM.32–34 High TTV could also reflect a more aggressive underlying tumor biology, with potentially decreased sensitivity to systemic therapy. Patients with TTV progression of more than 40% showed a trend of younger age compared with the other TTV response groups. Interestingly, a recent study of Jácome et al35 demonstrated that in patients with CRLM undergoing resection, earlier onset of disease (ie, younger age) in combination with RAS mutation was prognostic for poorer overall survival in comparison to patients with late age onset.35 These results indicate that TTV might be a reliable prognostic factor also in these patient groups. This is in agreement with the study of Tai et al,22 where TTV at baseline was prognostic for both overall survival and RFS in patients with multiple CRLM, while RECIST1.1 was not.22

Currently, consensus regarding volumetric thresholds defining response to treatment, stable disease or progression is lacking, since different thresholds for volumetric response based on tumor shape are being used.21,23,36 Guidelines within RECIST1.1 for volumetric assessment defined the geometrical relationship between change in diameter and volume based on the spherical shape of tumors, and stated that 30% decrease in diameter correlated geometrically to 65% decrease in volume, while 20% increase in diameter correlated with 73% increase in volume.13 Other studies based their volumetric criteria on the ellipsoid shape of tumors, using the thresholds of 30% decrease in volume and 20% increase in volume other studies.19,21,23 Moreover, no criteria for the assessment of TTV are defined yet, as only assessments of target lesions have been described.19,36,37

In this study, different thresholds for TTV response assessment were examined as no standard currently exists and response was more often classified when applying those thresholds than following RECIST1.1 response classification. As expected, the majority of patients with initially unresectable CRLM that became secondarily resectable after systemic treatment showed TTV decrease (>10%) and only a small number of patients had progressive or stable TTV. The results showed that change in TTV was prognostic for RFS, while no significant differences were observed between the RECIST1.1 response groups. These findings strengthen the hypothesis that change in TTV could be a reliable prognostic factor. However, the clinical relevance of 1 month difference in RFS using the 10% TTV thresholds in a small number of patients could be debated. Therefore, the applied TTV thresholds in this study should be validated in a larger study population of an external dataset. Additionally, thresholds should be investigated with receiver operating characteristics curve analysis based on survival outcomes, such as overall survival and progression-free survival.

Median RFS of 5 months and maximum RFS of 10 months in patients with small decrease in TTV (less than 10%) were observed in this study. The benefit of local treatment for these patients could be argued, as median progression-free survival of unresectable metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with systemic therapy is up to 12 months.38 In trials restricted to patients with initially unresectable liver-only metastases, similar progression-free survival around 12 months (range 10–18) is described.38–43

Accurate response evaluation is pivotal to the treatment of patients with initially unresectable CRLM. However, the current RECIST1.1 guidelines only include unidimensional size changes of maximum 2 target lesions per organ, thereby ignoring potentially valuable other information of the tumors, such as TTV, morphological changes, early tumor shrinkage, and depth of response. These alternative radiological metrics have been found prognostic for overall survival, progression-free survival, or pathologic response in patients with CRLM treated with systemic therapy.18,22,44,45 TTV assessment could represent a more complete evaluation of the tumor burden, as the effect on the overall tumor load is evaluated and 3D measurements may capture size changes better than unidimensional measurements. A recent study demonstrated that the limited number of target lesions following RECIST1.1 may not be an accurate representation of the overall tumor load in patients with metastatic cancer, including liver-only metastases.14

In this study, TTV was measured based on the semiautomatic segmentations of all CRLM with specially developed software, enabling assessment of the whole tumor burden. The positive results presented in this study suggest that TTV assessment appears a promising method to improve tumor response evaluation in patients with CRLM. Nevertheless, the semiautomatic segmentations used for volumetric assessment in this study are still time-consuming and advanced volumetric software is not yet widely available in every radiology department. To actually implement TTV assessment in clinical practice, fully automatic volumetric algorithms should be developed. Another important factor to implement TTV assessment in clinical practice is the CE marking or Food and Drug Administration approval for such tool. The specially developed action used to calculate TTV in this study is not CE or Food and Drug Administration approved for clinical practice. In fact, this action is part of the development of an automatic tumor response pipeline conducted by this research group. This pipeline is still under development and will be externally validated in future studies. With the use of automatic algorithms, volume measurements of individual tumors could also play a role in the assessment of mixed tumor response in future studies. This mixed response is common and observed in approximately 35% of patients with multiple CRLM treated with systemic therapy, showing poorer prognosis than patients with homogeneous response, and might point toward different tumor biology of different CRLM.46,47

This study had several limitations. First, survival outcomes were only investigated in a subgroup of patients who became eligible for hepatic resection after induction treatment, because the CAIRO5 trial is ongoing, and no analysis could be performed on the whole study group. As a result, the prognostic value of TTV change could only be investigated in a selection of patients, excluding potentially interesting patients with large TTV increase or other specific patient groups. Therefore, the relation of TTV response assessment with survival needs to be further established in a future study when the CAIRO5 trial is completed. Second, the evaluation of nontarget lesions was not included in the assessment of RECIST1.1 in current study. This may have resulted in a selective comparison between RECIST1.1 and TTV. The evaluation of nontarget lesions was often not described in the CAIRO5 radiology reports but should be included in future studies. Third, the results of this study were based on the tumor response assessment of the first follow-up scan only. The assessment of tumor response using TTV and RECIST1.1 on the second follow-up scan may also be valuable.48,49

In future studies, implementation of more additional imaging features, such as morphological changes, in tumor response assessment is recommended, because patients with CRLM may also show a morphological response to systemic treatment without affecting tumor size.18,50

In conclusion, TTV response assessment shows prognostic potential in the evaluation of systemic therapy response in patients with initially unresectable CRLM and could contribute to the improvement of treatment selection. Change in TTV differed from RECIST1.1 in 30% to 50% of initially unresectable CRLM patients, using different TTV thresholds. Furthermore, change in TTV (using 10% and 20% TTV thresholds) was found prognostic for RFS in patients with secondarily resectable CRLM after induction therapy, while RECIST1.1 was not. The actual benefit of TTV response assessment needs to be validated in future studies.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Special thanks to Sam C. Postma who contributed to the process of data acquisition.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

C.J.A.P. has an advisory role for Nordic Pharma. This funding is not related to the current research. The remaining authors declare no potential conflicts of interest. The CAIRO5 study is supported by unrestricted scientific grants from Roche and Amgen. The funders had no role in the design, conduct, and submission of the study, or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

N.J.W., K.B., J.H., G.K. participated in research design. N.J.W., K.B., R.-J.S., C.J.A.P., J.H., G.K. participated in research manuscript writing. N.J.W., K.B., J.R., J-.H.T.M.v.W., S.v.D., M.J.v.A., T.C., C.H.C.D., M.R.W.E., M.F.G., D.G., T.M.v.G., J.J.H., K.P.d.J., J.M.K., M.S.L.L., K.P.v.L., I.Q.M., G.A.P., A.M.R., T.M.R., C.V., J.H.W.d.W., R.-J.S., C.J.A.P., G.K. participated in the performance of the research. N.J.W., K.B., J.R., J-.H.T.M.v.W. participated in data collection. N.J.W., K.B., J.R., S.D., R.-J.S., C.J.A.P., J.H., G.K. participated in data analysis. All authors involved in the critical revision of manuscript.

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s Web site (www.annalsofsurgery.com).

Members of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group Liver Expert Panel: Martin J. van Amerongen, Thiery Chapelle, Cornelis H. C. Dejong, Marc R. W. Engelbrecht, Michael F. Gerhards, Dirk Grunhagen, Thomas M. van Gulik, John J. Hermans, Koert P. de Jong, Joost M. Klaase, Mike S. L. Liem, Krijn P. van Lienden, I. Quintus Molenaar, Gijs A. Patijn, Arjen M. Rijken, Theo M. Ruers, Cornelis Verhoef, Johannes H. W. de Wilt, Rutger-Jan Swijnenburg, Geert Kazemier.

REFERENCES

- 1.Elferink MA, de Jong KP, Klaase JM, et al. Metachronous metastases from colorectal cancer: a population-based study in North-East Netherlands. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2015;30:205–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van der Geest LG, Lam-Boer J, Koopman M, et al. Nationwide trends in incidence, treatment and survival of colorectal cancer patients with synchronous metastases. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2015;32:457–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adam R, De Gramont A, Figueras J, et al. ; Jean-Nicolas Vauthey of the EGOSLIM (Expert Group on OncoSurgery management of LIver Metastases) group. The oncosurgery approach to managing liver metastases from colorectal cancer: a multidisciplinary international consensus. Oncologist. 2012;17:1225–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simmonds PC, Primrose JN, Colquitt JL, et al. Surgical resection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: a systematic review of published studies. Br J Cancer. 2006;94:982–999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Ridder JAM, van der Stok EP, Mekenkamp LJ, et al. Management of liver metastases in colorectal cancer patients: a retrospective case-control study of systemic therapy versus liver resection. Eur J Cancer. 2016;59:13–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Norén A, Eriksson HG, Olsson LI. Selection for surgery and survival of synchronous colorectal liver metastases; a nationwide study. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:105–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adam R, Delvart V, Pascal G, et al. Rescue surgery for unresectable colorectal liver metastases downstaged by chemotherapy: a model to predict long-term survival. Ann Surg. 2004;240:644–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Adam R, Kitano Y. Multidisciplinary approach of liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Ann Gastroenterol Surg. 2019;3:50–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lam VW, Spiro C, Laurence JM, et al. A systematic review of clinical response and survival outcomes of downsizing systemic chemotherapy and rescue liver surgery in patients with initially unresectable colorectal liver metastases. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:1292–1301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Adam R. Developing strategies for liver metastases from colorectal cancer. Semin Oncol. 2007;34(2 suppl 1):S7–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poston GJ, Figueras J, Giuliante F, et al. Urgent need for a new staging system in advanced colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:4828–4833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1). Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer, National Cancer Institute of the United States, National Cancer Institute of Canada. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kuhl CK, Alparslan Y, Schmoee J, et al. Validity of RECIST Version 1.1 for response assessment in metastatic cancer: a prospective, multireader study. Radiology. 2019;290:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sosna J. Is RECIST Version 1.1 reliable for tumor response assessment in metastatic cancer? Radiology. 2019;290:357–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yoon SH, Kim KW, Goo JM, et al. Observer variability in RECIST-based tumour burden measurements: a meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2016;53:5–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaumont H, Evans TL, Klifa C, et al. Discrepancies of assessments in a RECIST 1.1 phase II clinical trial - association between adjudication rate and variability in images and tumors selection. Cancer Imaging. 2018;18:50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chun YS, Vauthey JN, Boonsirikamchai P, et al. Association of computed tomography morphologic criteria with pathologic response and survival in patients treated with bevacizumab for colorectal liver metastases. JAMA. 2009;302:2338–2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schiavon G, Ruggiero A, Schöffski P, et al. Tumor volume as an alternative response measurement for imatinib treated GIST patients. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rothe JH, Grieser C, Lehmkuhl L, et al. Size determination and response assessment of liver metastases with computed tomography–comparison of RECIST and volumetric algorithms. Eur J Radiol. 2013;82:1831–1839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hayes SA, Pietanza MC, O’Driscoll D, et al. Comparison of CT volumetric measurement with RECIST response in patients with lung cancer. Eur J Radiol. 2016;85:524–533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tai K, Komatsu S, Sofue K, et al. Total tumour volume as a prognostic factor in patients with resectable colorectal cancer liver metastases. BJS open. 2020;4:456–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schiavon G, Ruggiero A, Bekers DJ, et al. The effect of baseline morphology and its change during treatment on the accuracy of Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumours in assessment of liver metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2014;50:972–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huiskens J, van Gulik TM, van Lienden KP, et al. Treatment strategies in colorectal cancer patients with initially unresectable liver-only metastases, a study protocol of the randomised phase 3 CAIRO5 study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG). BMC Cancer. 2015;15:365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huiskens J, Bolhuis K, Engelbrecht MR, et al. ; Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Outcomes of resectability assessment of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group Liver Metastases Expert Panel. J Am Coll Surg. 2019;229:523–532.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Couinaud C, Foie L. Etudes anatomiques et chirurgicales. Mason;1957:400–409. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fong Y, Fortner J, Sun RL, et al. Clinical score for predicting recurrence after hepatic resection for metastatic colorectal cancer: analysis of 1001 consecutive cases. Ann Surg. 1999;230:309–318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.SAS Visual Data Mining and Machine Learning Programming Guide: The quantifyBioMedImages Action 2020. Available at: https://go.documentation.sas.com/?cdcId=pgmsascdc&cdcVersion=9.4_3.5&docsetId=casactml&docsetTarget=casactml_biomedimage_details05.htm&locale=en. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 29.Innolitics. DICOM Standard Browser: Image Plane Module 2020. Available at: https://dicom.innolitics.com/ciods/ct-image/image-plane. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- 30.Bolhuis K, Huiskens J, Bond MJG, et al. Treatment strategies in colorectal cancer patients with initially unresectable liver-only metastases CAIRO5 a randomised phase 3 study of the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group (DCCG) 2020. Available at: https://dccg.nl/files/C1.CAIRO5%20protocol%20amendement%20V.10.0%20%20final%2007-10-2020%20clean.pdf. Accessed January 3, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang K, Liu W, Yan XL, et al. Long-term postoperative survival prediction in patients with colorectal liver metastasis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:79927–79934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Margonis GA, Sasaki K, Gholami S, et al. Genetic And Morphological Evaluation (GAME) score for patients with colorectal liver metastases. Br J Surg. 2018;105:1210–1220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sasaki K, Margonis GA, Andreatos N, et al. Pre-hepatectomy carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) levels among patients undergoing resection of colorectal liver metastases: do CEA levels still have prognostic implications? HPB (Oxford). 2016;18:1000–1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Connell LC, Boucher TM, Chou JF, et al. Relevance of CEA and LDH in relation to KRAS status in patients with unresectable colorectal liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2017;115:480–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jácome AA, Vreeland TJ, Johnson B, et al. The prognostic impact of RAS on overall survival following liver resection in early versus late-onset colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2021;124:797–804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van Kessel CS, van Leeuwen MS, Witteveen PO, et al. Semi-automatic software increases CT measurement accuracy but not response classification of colorectal liver metastases after chemotherapy. Eur J Radiol. 2012;81:2543–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee IS, Choi SJ, Seo CR, et al. Comparison of the response evaluation criteria in solid tumors with volumetric measurement for evaluation of response and overall survival with liver metastases from colorectal cancer. J Korean Soc Radiol. 2019;80:906–918. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bolhuis K, Kos M, van Oijen MGH, et al. Conversion strategies with chemotherapy plus targeted agents for colorectal cancer liver-only metastases: a systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2020;141:225–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye LC, Liu TS, Ren L, et al. Randomized controlled trial of cetuximab plus chemotherapy for patients with KRAS wild-type unresectable colorectal liver-limited metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31:1931–1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tang W, Ren L, Liu T, et al. Bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX6 versus mFOLFOX6 alone as first-line treatment for RAS mutant unresectable colorectal liver-limited metastases: the BECOME randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:3175–3184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Carrato A, Abad A, Massuti B, et al. ; Spanish Cooperative Group for the Treatment of Digestive Tumours (TTD). First-line panitumumab plus FOLFOX4 or FOLFIRI in colorectal cancer with multiple or unresectable liver metastases: a randomised, phase II trial (PLANET-TTD). Eur J Cancer. 2017;81:191–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Folprecht G, Gruenberger T, Bechstein WO, et al. Tumour response and secondary resectability of colorectal liver metastases following neoadjuvant chemotherapy with cetuximab: the CELIM randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:38–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gruenberger T, Bridgewater J, Chau I, et al. Bevacizumab plus mFOLFOX-6 or FOLFOXIRI in patients with initially unresectable liver metastases from colorectal cancer: the OLIVIA multinational randomised phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:702–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cremolini C, Loupakis F, Antoniotti C, et al. Early tumor shrinkage and depth of response predict long-term outcome in metastatic colorectal cancer patients treated with first-line chemotherapy plus bevacizumab: results from phase III TRIBE trial by the Gruppo Oncologico del Nord Ovest. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1188–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Primavesi F, Fadinger N, Biggel S, et al. Early response evaluation during preoperative chemotherapy for colorectal liver metastases: combined size and morphology-based criteria predict pathological response and survival after resection. J Surg Oncol. 2019;121:382–391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van Kessel CS, Samim M, Koopman M, et al. Radiological heterogeneity in response to chemotherapy is associated with poor survival in patients with colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:2486–2493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Brunsell TH, Cengija V, Sveen A, et al. Heterogeneous radiological response to neoadjuvant therapy is associated with poor prognosis after resection of colorectal liver metastases. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2019;45:2340–2346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.White RR, Schwartz LH, Munoz JA, et al. Assessing the optimal duration of chemotherapy in patients with colorectal liver metastases. J Surg Oncol. 2008;97:601–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Heinemann V, Stintzing S, Modest DP, et al. Early tumour shrinkage (ETS) and depth of response (DpR) in the treatment of patients with metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC). Eur J Cancer. 2015;51:1927–1936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shindoh J, Loyer EM, Kopetz S, et al. Optimal morphologic response to preoperative chemotherapy: an alternate outcome end point before resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:4566–4572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]