Abstract

For the standardization of serological tests for Lyme borreliosis (LB) in Europe, the influence of the heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato must be assessed in detail. For this study four immunoglobulin M (IgM) and IgG enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) with octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside extracts of strains PKo (Borrelia afzelii), PBi (Borrelia garinii), and PKa2 and B31 (both B. burgdorferi sensu stricto) were compared. Strains PKo, PBi, and PKa2 at the passages used for antigen preparations abundantly expressed outer surface protein C (OspC), whereas strain B31 at the passage used for antigen preparation did not express OspC. Sera (all from Germany) from 222 patients with clinically defined LB of all stages, 133 blood donors, and 458 forest workers were tested. None of the forest workers had symptoms consistent with LB at the time that the samples were collected. For IgM tests, receiver operating characteristic curves demonstrated that discrimination between sera from patients and blood donors was best with strain PKo and worst with strain B31. The discriminatory abilities of the four IgG ELISAs were similar in a diagnostically reasonable specificity range (90 to 100%). More than 20% of the sera from forest workers reacted strongly in the PKo IgG ELISA (optical density value, >1.5; other assays, less than 8%). Western blots of the sera with the most discrepant ELISA results revealed almost exclusive reactivity with p17. This highly immunogenic antigen is only expressed by strain PKo. This observation might be important for the development of assays enabling discrimination between asymptomatic or previous infection and active disease.

Lyme borreliosis (LB) is a global tick-associated disease caused by infection with Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. The disorder develops in stages and has different manifestations. In Europe, three species pathogenic for humans (2) and at least eight serotypes of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (40, 44) demonstrating both inter- and intraspecies heterogeneity are known. Different species seem to show a preferential association with different clinical manifestations (1, 35, 44). The most frequent disorders in Eurasia are erythema migrans (EM) localized around the tick bite lesion, neuroborreliosis (NB), acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (ACA), and arthritis (19, 32). In Europe, all three pathogenic species have been isolated from human biopsy specimens and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) as well as from ticks (Ixodes ricinus), but the predominant species seem to be Borrelia afzelii and Borrelia garinii. B. afzelii has been found to be associated more frequently with skin lesions, whereas B. garinii is the predominant species found in patients with neurological disorders (8, 35, 40, 44). In North America only B. burgdorferi sensu stricto occurs (30, 44); arthritis occurs frequently, whereas ACA is almost unknown, and multiple EM lesions are more common in North America than in Europe (33).

The diagnosis of Lyme disease is based on the recognition of typical clinical signs and is supported by laboratory tests, especially if the clinical picture is not clear. Since culture is laborious and insensitive and PCR assays are still considered controversial, routine testing comprises mostly serological methods. However, serology also harbors several problems: The occurrence of cross-reacting antibodies may result in false-positive findings (5). Furthermore, patients may still be seronegative in the early stages of the infection and the humoral immune response can be diminished after the early onset of antibiotic treatment (37). Several strategies for increasing both sensitivity and specificity (i.e., the discriminatory ability of the test) have been developed, for instance, preabsorption of cross-reactive antibodies with Treponema phagedenis (49), the use of detergent extracts of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (3), and the use of purified flagella (16) or various recombinant antigens (7, 31, 41, 42).

Serological tests for Lyme disease have not been standardized so far, leading to considerable variations in test results among different laboratories. The heterogeneity of Lyme disease borreliae as well as different methods of antigen preparation and test performance may contribute to the problem.

In Europe, the extent of variation resulting from the use of different strains for antigenic preparations is still widely discussed (1, 23, 46, 48). Differences in the regional distributions of borrelial species may further influence the preferential reactivities of sera from patients with LB (6, 26).

In this study, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (ELISAs) with detergent extracts of different strains representing the three species pathogenic for humans were compared. Strains PKo (B. afzelii), PBi (B. garinii), and PKa2 (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto) at the passage used to obtain coating antigens abundantly expressed outer surface protein C (OspC), whereas strain B31 (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto) at the passage used to obtain coating antigen did not express OspC. In Western blot studies OspC has been shown to be one of the most immunodominant antigens for the early immune response (12, 13, 17, 48). The influence of the expression of this lipoprotein on the results of ELISAs was especially monitored by comparison of the test results for the otherwise closely related B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strains PKa2 and B31 (20, 29, 38, 43). To analyze the sensitivities and specificities of the four ELISAs, we probed sera from German patients with different clinical manifestations as well as sera from healthy blood donors and forest workers (as an example of a group highly exposed to ticks and at high risk of contracting infections with B. burgdorferi sensu lato).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Sera.

Sixty-six serum specimens from unselected, untreated patients with EM were obtained by a dermatologist during a previous multicenter therapy study (37). The median time period between the appearance of EM and collection of the serum samples was 3 weeks (range, 1 day to 31 weeks). The sera were collected from patients throughout Germany during the years 1989 through 1991 during the months April through January. The NB group (n = 125) included 38 patients (designated NB I) from whom B. burgdorferi sensu lato was isolated from CSF and 87 other patients (designated NB II) with typical signs of acute NB, CSF pleocytosis, and specific immunoglobulin G (IgG) CSF/serum indices of >2.0 determined by an in-house ELISA with strain PKo (39). All serum specimens were obtained on the same days that the CSF specimens were obtained. The median durations of neurological symptoms prior to obtaining the serum samples was 3 weeks in both NB groups (range, 1 day to 1 year). These sera were collected during the years 1984 through 1995 during the months May through January (72 serum specimens were obtained in August or September). The patients came from throughout Germany, but most were from the south. Thirty-one serum specimens were obtained from patients with ACA diagnosed by a dermatologist. Samples were collected during the years 1988 through 1995 with no seasonal dependence. The patients came from throughout Germany, but most were from the south. Sera (n = 458) from healthy forest workers from Bavaria (southern Germany) were collected during a former study (25) during the years 1984 and 1985. Sera from 133 blood donors were investigated for determination of cutoffs. Samples were obtained in December 1990 from a Munich blood bank. The whole of Germany is a region where LB is endemic. All sera were stored in aliquots at −20°C.

Preparation of antigens.

Borrelial strains PKo (B. afzelii; OspA serotype 2), PBi (B. garinii; OspA serotype 4), PKa2 (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto; OspA serotype 1), and B31 (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto; OspA serotype 1) (44) were used for antigen preparations. Strains PKo, PBi, and PKa2 have been isolated from German patients at the Max von Pettenkofer-Institut für Hygiene und Medizinische Mikrobiologie, Munich; PKo was isolated from skin (EM), and PBi and PKa2 were cultured from CSF. Strain B31 was obtained from W. Burgdorfer (Hamilton, Mont.). Strains were grown in modified Kelly medium (28) at 33°C for 4 to 5 days and were harvested at a cell density of 107/ml. The protein concentration of the final suspension was estimated by the Bradford (4) protein assay (Bio-Rad, Munich, Germany). The preparation was stored at 20°C.

Low-passage strains (approximately 25 passages) PKo, PBi, and PKa2 abundantly expressed OspC, whereas the high-passage strain B31 did not. This was shown by Coomassie brilliant blue staining after sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) as well as by probing with the OspC-specific monoclonal antibody L22 1F8 (45). If OspC had been expressed by the passage of B31 used, it would have been recognized by L22 1F8 (43).

ELISAs.

Microtiter plates were coated with whole-cell octyl-β-d-glucopyranoside (OGP) extracts of the respective antigen preparations (27). The concentrations of the coating antigens were optimized for the best matching of the different strains by using a representative panel of human sera (11 individual serum samples from German patients and blood donors; 5 were IgG negative, and 6 were IgG positive). The protein concentration (0.5 to 3 μg/ml) was not identical for each strain, since coating was optimized for each strain by antigen titration to obtain the best correlation of signals. Plates were coated identically for both IgG and IgM tests, and all assays were performed with the same batch of plates. Assays were performed separately for IgG and IgM, according to the manufacturer’s instructions for the commercial PKo ELISA, by using a Behring ELISA processor III (Enzygnost Borreliosis; Behring Diagnostics, Marburg, Germany). The sample diluent contained ultrasonicated cell lysates of T. phagedenis for absorption of cross-reacting antibodies. All sera were evaluated twice (in the same microtiter well), and testing was repeated if these readings differed by more than 10% for optical density (OD) values greater than 0.150. A weakly positive serum sample used as a calibrator and one negative serum sample were processed in duplicate on each plate. The mean of all readings for the calibrator serum sample throughout the study was determined. Interassay variability was compensated for by using a correcting factor obtained by dividing this mean by the actual OD value. Mean OD values for the calibrator serum sample were between 0.613 and 0.863 for the different assays, and correcting factors ranged from 0.719 to 1.297. For the commercial PKo assay, the intra- and interassay coefficients of variation are usually less than 15% for positive samples, and the assays with the other strains were produced and run in exactly the same way. Quantification of specific IgG has been established for the PKo assay (27).

SDS-PAGE and WB.

Western blotting (WB) was performed and the results were interpreted as previously described in detail (17). Briefly, a cell lysate was electrophoresed (22) by using 12.5% polyacrylamide gels 17 cm in length. Proteins were transferred to nitrocellulose (Schleicher & Schuell, Dassel, Germany) by semidry blotting (21). After blocking of unspecific binding sites, the membranes were incubated in sera diluted 1:200 for the IgG WB and 1:100 for the IgM WB, washed, and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-human IgG and IgM antibodies, respectively (Dakopatts, Copenhagen, Denmark) (dilutions, 1:1,000 for IgG and 1:500 for IgM). Color was developed by adding diaminobenzidine and H2O2.

The following interpretation criteria for a positive WB result were used: for IgG WB, at least two bands of p83/100, p58, p43, p39, p30, OspC, p21, p17, and p14 for PKo, at least one band of p83/100, p39, OspC, p21, and p17b for PBi, and at least one band of p83/100, p58, p56, OspC, p21, and p17a for PKa2; for IgM WB, at least one band of p39, OspC, and p17 or a strong p41 band for PKo, at least one band of p39 and OspC or a strong p41 band for PBi, and at least one band of p39, OspC, and p17a or a strong p41 band for PKa2 (17).

Statistics.

When appropriate, the results were analyzed by McNemar’s χ2 test (paired proportions) or Fisher’s exact test (independent proportions). All statistical tests were performed in a two-sided manner.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, which are plots of 1 − specificity versus sensitivity (false-positive rate versus true-positive rate), were constructed for all ELISAs. Specificity levels were based on various cutoff values obtained from percentile calculations for 133 blood donors; the respective sensitivities were determined by testing 222 serum samples from patients with LB. The discriminatory ability of each assay is represented by the area between the diagonal line from 0/0 to 1/1 and the respective ROC curve (11).

Spearman rank correlation coefficients were determined (OD values were not normally distributed) to analyze the correlation of the OD values from the different ELISAs (11).

RESULTS

Preparation of antigens.

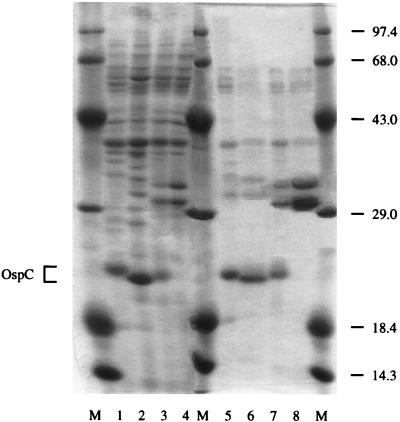

As demonstrated in Fig. 1, strains PKo, PBi, and PKa2 abundantly expressed OspC at the passages used, whereas strain B31 completely lacked this antigen at the passage used. OGP extracts of these whole-cell lysates were used as antigenic coatings.

FIG. 1.

Coomassie brilliant blue-stained SDS-polyacrylamide gel demonstrating the antigenic preparations used for ELISAs. Lanes M, molecular mass marker; lane 1, whole-cell lysate of strain PKo (B. afzelii); lane 2, whole-cell lysate of strain PBi (B. garinii); lane 3, whole-cell lysate of strain PKa2 (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto); lane 4, whole-cell lysate of strain B31 (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto); lane 5, OGP extract of strain PKo; lane 6, OGP extract of strain PBi; lane 7, OGP extract of strain PKa2; lane 8, OGP extract of strain B31. The OGP extracts in lanes 5 to 8 were used as antigenic coatings. The OspC bands of strains PKo, PBi, and PKa2 are indicated on the left. Strain B31 did not express OspC. Numbers on the right indicate the molecular masses of the marker proteins (in kilodaltons).

Definition of cutoff values.

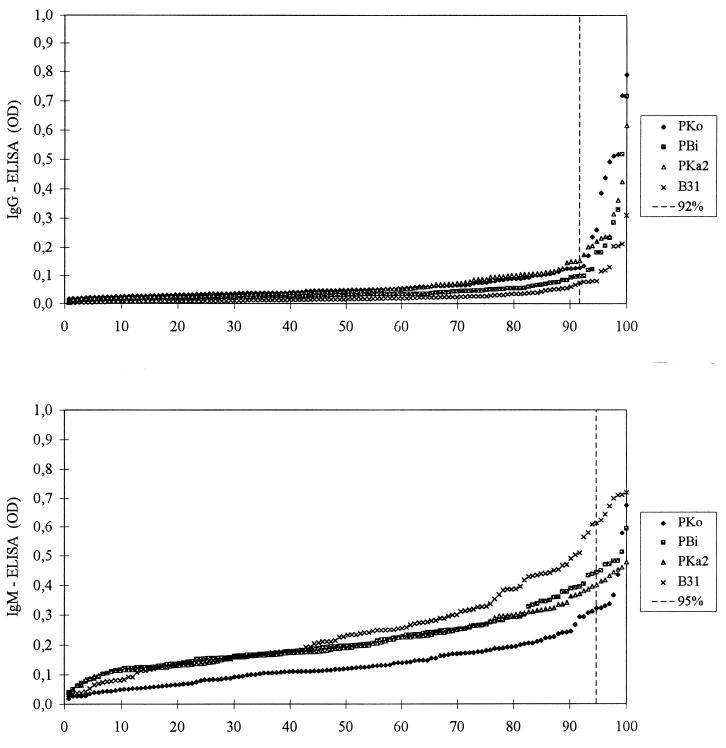

Sera (n = 133) from blood donors were tested, and the OD values of all sera were sorted separately for each test for the determination of percentiles (Fig. 2). The 10 most strongly reacting serum samples in the IgG ELISAs and the 18 most strongly reacting serum samples in the IgM ELISAs were subsequently tested by WB with whole-cell lysates of the respective strains. Most sera were either positive or showed reactions with unspecific bands (for IgG WB with PKo, 6 positive and 3 unspecific serum samples; for IgG WB with PBi, 5 positive and 4 unspecific serum samples; for IgG WB with PKa2, 6 positive and 2 unspecific serum samples; for IgM-WB with PKo, 6 positive and 10 unspecific serum samples; for IgM WB with PBi, 7 positive and 8 unspecific serum samples; for IgM WB with PKa2, 5 positive and 9 unspecific serum samples). Between the 92nd and 100th percentiles the OD values of the IgG ELISAs increased considerably, whereas in the IgM ELISAs a gradual increase was observed. The OD values of the 92nd and the 95th percentiles were defined as cutoffs for the IgG and the IgM assays, respectively (Table 1). For simplification, no borderline or retest ranges were defined in this study.

FIG. 2.

Results of ELISAs with OGP extracts of the four strains for sera from 133 blood donors. The resulting OD values were sorted in increasing order for the determination of percentiles. Percentiles taken as cutoff values are indicated by broken lines (92nd percentile for IgG tests, 95th percentile for IgM tests).

TABLE 1.

Cutoff values for different ELISAs

| Ig class | Cutoff value (OD) for ELISA with the following strain:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKo | PBi | PKa2 | B31 | |

| IgG | 0.127 | 0.097 | 0.152 | 0.073 |

| IgM | 0.322 | 0.442 | 0.402 | 0.612 |

ROC curves.

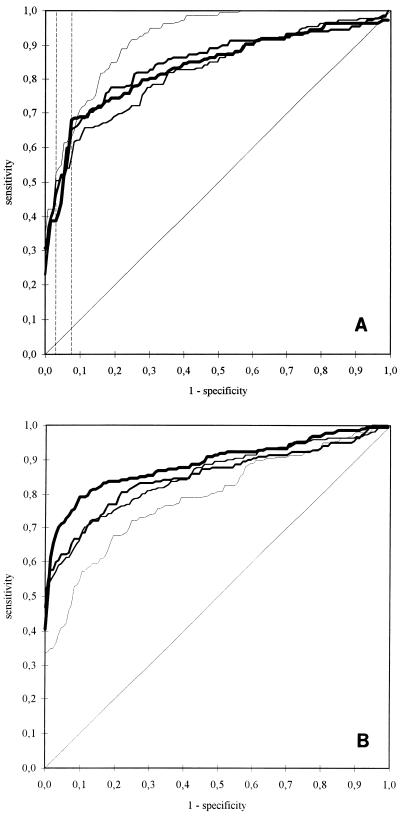

The discriminatory abilities (between patients and controls) of the four ELISAs were analyzed by ROC curves (Fig. 3). By this method, the properties of a diagnostic assay can be analyzed without reference to an individual (arbitrary) cutoff. For IgG tests the largest ROC areas resulted for the B31 ELISA, but in the specificity range of between 90 and 100%, which is conclusive for diagnostic purposes, the differences in the sensitivities of the four assays strongly depended on the specificity level. For example, at 92% specificity, the highest sensitivity was achieved with the PKo ELISA (PKo ELISA, 68%; PBi ELISA, 65%; PKa2 ELISA, 57%; B31 ELISA, 63%), whereas at 97% specificity, the PKo ELISA was the least sensitive (PKo ELISA, 39%; PBi ELISA, 46%; PKa2 ELISA, 50%; B31 ELISA, 53%). For IgM tests the ROC area of the PKo ELISA was the largest and the ROC area of the B31 ELISA was the smallest, meaning that the PKo test gave the best discrimination and the B31 test gave the worst.

FIG. 3.

ROC curves for different ELISAs. Specificity levels were based on various cutoff values obtained from percentiles for sera from 133 blood donors; the respective sensitivities were determined by probing 222 serum samples from patients with LB. The diagonal line (0/0 to 1/1) represents a completely uninformative test. The discriminatory ability of each assay is represented by the area between this line and the respective ROC curve. (A) ROC curves for IgG ELISAs. Broken lines, sensitivities at 92.5 and 97% specificity. (B) ROC curves for IgM ELISAs. ▪▪▪▪, PKo; ——————, PBi; ■■■■■■■■■, PKa2; ______, B31.

Sensitivities for different study groups.

Subsequently, the sensitivities of the four ELISAs were determined separately for all study groups (Table 2). Whenever possible, differences between ELISAs were analyzed by McNemar’s χ2 test.

TABLE 2.

Sensitivities of the different ELISAs

| Study group | Total no. of serum samples | Ig class(es) evaluated | % Sera positivea in ELISA with the following strain:

|

P valueb

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PKo | PBi | PKa2 | B31 | PKo versus PBi | PKo versus PKa2 | PBi versus PKa2 | PKo versus B31 | PBi versus B31 | PKa2 versus B31 | |||

| NB I | 38 | IgG | 55.3 | 55.3 | 57.9 | 42.1 | NDc | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| IgM | 68.4 | 68.4 | 71.1 | 52.6 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | ND | >0.05 | ND | ||

| IgG and IgMd | 78.9 | 81.6 | 84.2 | 73.7 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| NB II | 87 | IgG | 80.5 | 79.3 | 70.1 | 75.9 | >0.05 | <0.05 | ND | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 |

| IgM | 87.4 | 83.9 | 78.1 | 48.3 | >0.05 | <0.05 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| IgG and IgM | 97.7 | 95.4 | 93.1 | 83.9 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | <0.05 | ||

| Patients with EM | 66 | IgG | 45.5 | 37.9 | 34.8 | 47.0 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | <0.05 |

| IgM | 63.6 | 42.4 | 45.4 | 39.4 | ND | <0.01 | >0.05 | <0.001 | >0.05 | >0.05 | ||

| IgG and IgM | 75.8 | 62.1 | 62.1 | 65.2 | <0.05 | <0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | >0.05 | ||

| Patients with ACA | 31 | IgG | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND |

| IgM | 48.4 | 35.5 | 29.0 | 9.7 | >0.05 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| IgG and IgM | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | 100.0 | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ||

| Forest workers | 458 | IgG | 44.8 | 40.0 | 44.8 | 41.0 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.01 | <0.05 | >0.05 | <0.05 |

| IgM | 12.0 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 1.1 | <0.001 | <0.001 | >0.05 | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | ||

| IgG and IgM | 46.9 | 42.4 | 47.4 | 41.5 | <0.01 | >0.05 | <0.01 | <0.01 | >0.05 | <0.01 | ||

Samples with OD values exceeding the cutoff values listed in Table 1.

P values were determined by McNemar’s χ2 test.

ND, not done. Performance of McNemar’s χ2 test is not possible if one or both of the parameters test A positive and test B negative or test B positive and test A negative are equal to zero.

At least one test (IgG or IgM) was positive.

For NB I, similar sensitivities were obtained by the PKo, PBi, and PKa2 ELISAs, but the sensitivities of the B31 ELISAs were lower. However, since no more than 38 samples were available for this group (a positive culture of CSF was required), these differences were insignificant. By testing for both IgG and IgM, 73.7% (B31 ELISA) to 84.2% (PKa2 ELISA) of the sera were found to be positive. For NB II, the PKo tests were the most sensitive, followed by the PBi, PKa2, and B31 tests, in decreasing order.

The best strain for the detection of antibodies in patients with EM lesions was PKo. The PBi and PKa2 ELISAs showed similar results, while the results of the B31 IgG ELISA were comparable to those of the PKo IgG assay, but the B31 IgM ELISA was the least sensitive of the four IgM tests. By testing for both IgG and IgM, 62.1% (PBi and PKa2 ELISAs) to 75.8% (PKo ELISA) of the sera were positive.

All sera from patients with ACA were reactive in all four IgG ELISAs. IgM antibodies could be detected in 9.7% (B31 ELISA) to 48.4% (PKo ELISA) of the patients with ACA.

The sera from the forest workers were more frequently reactive in IgG ELISAs with PKo or PKa2 than in IgG ELISAs with PBi or B31. IgM tests were positive for 1.1% (B31 ELISA) to 12.0% (PKo ELISA) of the forest workers. A total of 41.5% (B31 ELISA) to 46.9% (PKo ELISA) of the sera were positive by evaluation by both IgG and IgM tests.

Correlation of OD values of different ELISAs.

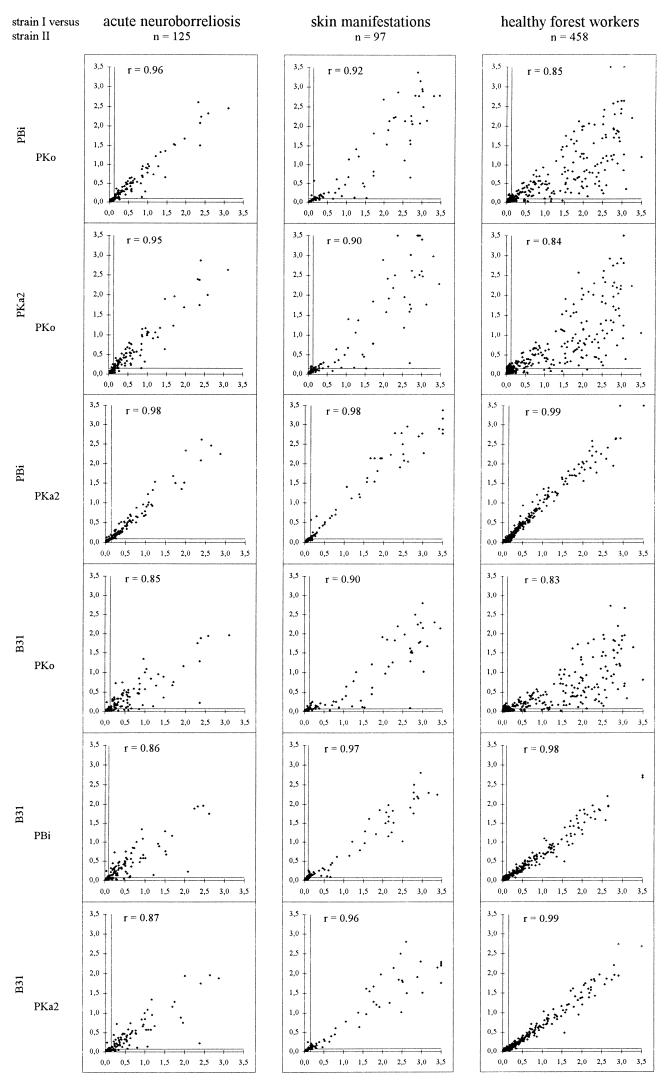

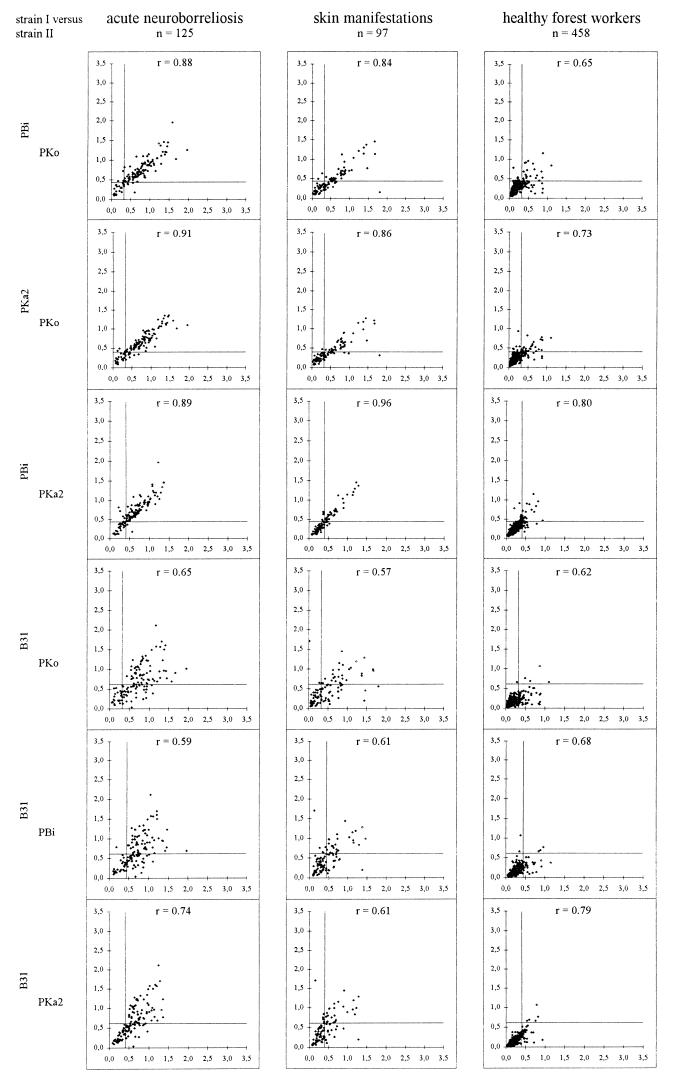

To demonstrate correlations of ELISA results, OD values from different assays were plotted against each other (Fig. 4 and 5). In IgG tests (Fig. 4) with sera from patients with NB the highest correlations occurred between the PKo, PBi, and PKa2 ELISAs (all Spearman rank correlation coefficients, r values, greater than 0.96). The correlation coefficients of the plots between ELISAs with each of the last three strains and the ELISA with strain B31 were between 0.84 and 0.87. For the groups of forest workers as well as patients with skin manifestations (EM and ACA), results of tests with strains PBi, PKa2, and B31 correlated better (r values, greater than 0.95 for all correlations) than the PKo ELISAs with any of these other assays (r values, between 0.84 and 0.93). This scattering resulted from the fact that several sera from these groups were considerably more reactive with PKo than with the other strains.

FIG. 4.

Plots of OD values of the different IgG ELISAs against each other. Continuous lines, cutoff OD values for the respective assays. r values, Spearman rank correlation coefficients.

FIG. 5.

Plots of OD values of the different IgM ELISAs against each other. Continuous lines, cutoff OD values for the respective assays. r values, Spearman rank correlation coefficients.

In IgM tests (Fig. 5) with sera from all patients with LB (both neurological and skin manifestations), the best correlations were found between PKo, PBi, and PKa2 ELISAs (r values, between 0.84 and 0.96). The scattering was wider in the plots of the data for the B31 ELISA against the data for the ELISAs with each of the other strains (r values, between 0.57 and 0.74). In tests with the sera from the forest workers, r was between 0.61 (PKo ELISA versus B31 ELISA) and 0.80 (PBi ELISA versus PKa2 ELISA).

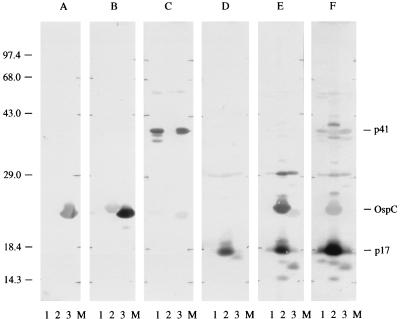

WB of selected sera.

Several sera which had shown discrepant reactivities in ELISAs with different antigens were further examined by WB to identify the individual antigens which were recognized. Since most serum samples did not show such discrepant reactivities, this selection does not represent the respective study groups, with the exception of some of the sera from forest workers and patients with ACA. Examples of some results are presented in Fig. 6. Serum samples A (from a patient with NB) and B (from a patient with EM) showed preferential IgM reactivity with OspC from PBi. Serum sample C (from a patient with NB) reacted with p41 of PKa2 and PBi but not with p41 of PKo, whereas serum sample D (also from a patient with NB) reacted almost only with p17 of PKo (both serum sample C and serum sample D were tested by WB for IgG). Serum samples E and F were obtained from a patient who had had an ACA 5 years previously (serum sample E) and a forest worker (serum sample F). They both showed remarkable preferential IgG reactivity with PKo, and the most immunodominant protein was p17. An additional 22 serum samples from forest workers, which were selected due to their predominant IgG reactivities with PKo, were also strongly reactive with p17 by WB.

FIG. 6.

Western blots with six selected serum samples with reproducible discrepant reactivities by ELISA. OD values for the different ELISAs are given in parentheses. (A) Serum from a patient with NB; IgM (PKa2, 0.252; B31, 0.334; PKo, 0.294; PBi, 0.728). (B) Serum from a patient with EM; IgM (PKa2, 0.325; B31, 0.437; PKo, 0.709; PBi, 0.898). (C) Serum from a patient with NB; IgG (PKa2, 0.412; B31, 0.325; PKo, 0.182; PBi, 0.353). (D) Serum from a patient with NB; IgG (PKa2, 0.153; B31, 0.062; PKo, 0.849; PBi, 0.135). (E) Serum from a patient who had had ACA 5 years previously; IgG (PKa2, 0.296; B31, 0.092; PKo, 2.687; PBi, 0.659). (F) Serum from a forest worker; IgG (PKa2, 0.323; B31, 0.213; PKo, 2.479; PBi, 0.327). Lanes 1, PKa2; lanes 2, PKo; lanes 3, PBi; lanes M, molecular mass marker. The numbers on the left indicate the molecular masses of the marker proteins (in kilodaltons). The most important immunodominant proteins are indicated on the right.

Elevated specific IgG concentrations in patients with clinical manifestations and asymptomatic infections.

The significance of OD values in different ranges of the four IgG ELISAs is demonstrated in Table 3. The percentages of sera with OD values greater than three arbitrarily defined levels (ODs of >0.5, >1.5, and >2.5) were determined for the patients with clinically defined LB as well as for the forest workers. The PKo ELISA showed no significant differences between these two groups (P > 0.05). However, in assays with all other strains, significantly higher percentages of sera from patients with LB were strongly reactive in comparison to the sera from forest workers (P < 0.01 for most comparisons).

TABLE 3.

Significance of elevated titers in sera from patients with LB versus sera from healthy forest workers by different IgG ELISAs

| Antigen | OD value | % of sera with OD values greater than the indicated level

|

P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with LB (n = 222) | Forest workers (n = 458) | |||

| PKo | >2.5 | 9.5 | 8.1 | >0.05 |

| >1.5 | 17.6 | 20.3 | >0.05 | |

| >0.5 | 38.7 | 31.7 | >0.05 | |

| PBi | >2.5 | 5.0 | 1.3 | <0.01 |

| >1.5 | 15.3 | 7.9 | <0.01 | |

| >0.5 | 32.0 | 21.6 | <0.01 | |

| PKa2 | >2.5 | 5.9 | 1.7 | <0.01 |

| >1.5 | 15.3 | 7.9 | <0.01 | |

| >0.5 | 33.3 | 22.3 | <0.01 | |

| B31 | >2.5 | 0.5 | 0.4 | >0.05 |

| >1.5 | 10.5 | 4.6 | <0.01 | |

| >0.5 | 24.5 | 16.4 | <0.05 | |

Differences between patients with LB and forest workers were analyzed by Fisher’s exact test.

DISCUSSION

Definition of cutoff values.

A basic precondition for the comparison of sensitivities of different tests is the definition of cutoff values. The 133 blood donors whom we tested for this purpose came from southern Bavaria, where Lyme disease occurs relatively frequently (19, 25) (incidence and prevalence are not known exactly, but on average, 12.6% [15] of the ticks in this area have been shown to be infected with B. burgdorferi sensu lato). The sera were obtained from a blood bank, and therefore, exclusion of samples from persons with a history of LB was not possible. Considering the remarkably higher IgG reactivities of a few of these serum specimens (Fig. 2), which were mostly confirmed by WB, it was assumed that these sera might represent samples from persons with prior infections. Thus, the cutoff OD values for the IgG ELISAs were defined by the 92nd percentile and not by the 95th percentile, as usual. Furthermore, cutoff values must provide a realistic basis for the comparison of the four assays, and the OD values between the 92nd and the 100th percentiles seemed to be much more strongly influenced by chance (Fig. 2). Since IgM reactivity reflects early disease, which presumably occurs comparably less frequently in a general population, the cutoffs for the IgM tests were defined by the 95th percentile. The resulting cutoff levels suitably reflect the differences in the four ELISAs. These differences might result from minor variations in the plate coatings as well as from the general preferential reactivity of the sera from the blood donors representing the local population.

In principle, this percentile method may lead to rather arbitrary results. Just a few samples from the blood donor panel are critical for the outcome of the whole study (unless thousands of sera are probed only for the definition of cutoffs). This problem can be demonstrated very clearly by the analysis of ROC curves. However, because all other methods are arbitrary as well, we retained it.

ROC curves.

The ROC curves for IgG tests (Fig. 3A) indicate that the best overall discrimination between sera from patients with LB and controls was achieved with B31 from the passage at which it lacked OspC. OspC is an early antigen which can also be recognized by unspecific antibodies at a very low level (13). Perhaps this could explain the lower background reactivity of the B31 IgG ELISA. However, the greatest distances between the four ROC curves were observed at specificity levels lower than 90%, which are not useful for diagnostic purposes. Regarding the section between 90 and 100% specificity, the curves are considerably more similar. Comparison of individual specificity levels, however (for example, 92 and 97%), leads to large variations in the differences in sensitivities between different tests. This clearly demonstrates the consequences of using arbitrarily defined cutoff levels.

For IgM ELISAs, the best discrimination was achieved with PKo and the worst was achieved with B31 (Fig. 3B). From Fig. 2 it is evident that 97% of the sera from blood donors had remarkably low OD values in the IgM PKo ELISA. On the other hand, by regarding the high degrees of correlation of the OD values from different IgM assays (Fig. 5), it seems as if the high sensitivity obtained with PKo might be caused by the relatively low cutoff. However, since all assays with the four antigen preparations were run in parallel and batches of plates were not changed throughout the study, a bias seems to be unlikely. The low discriminatory ability of the B31 IgM test can be explained by the lack of OspC, which is one of the most immunodominant proteins for the early immune response in patients with LB (12, 13, 17, 48).

Sensitivities for individual study groups.

For the sera from patients with EM and the NB II group, the best results were obtained with PKo. For the sera from patients with EM, this can be explained by the predominance of B. afzelii strains in skin lesions (8, 9, 44, 47). The sera from the NB II study group were selected on the basis of the criterion of a specific IgG CSF/serum index of >2.0, and this index was determined by a PKo-based ELISA. Therefore, the high sensitivity of the PKo ELISA in the current study could result from this selection. On the other hand, for sera from the NB I group (selection criterion, isolate from CSF), the sensitivities of the PKo, PBi, and PKa2 ELISAs were very similar, with the PKa2 ELISA showing a slightly higher sensitivity. However, in other studies sera from patients with neurological disorders were preferentially reactive with B. garinii (1, 26, 42), and strains of this species have been isolated most frequently from CSF (8, 40, 44). All sera from patients with ACA were positive in all IgG ELISAs, suggesting that the source of antigen is not critical for the detection of LB in sera from patients with late-stage LB. For the group of forest workers, a relatively high frequency of asymptomatic and previous infections can be assumed. At least 40% of their sera were positive by all IgG ELISAs (compared to 8% for the group of blood donors).

Correlation of OD values of different ELISAs.

For several sera from patients with ACA as well as from forest workers, a markedly stronger IgG reactivity with PKo was found (in comparison to those obtained with the other strains). Therefore, the correlations between PKo and all other strains were lower than the correlations among these other strains (Fig. 4). However, the good correlation of PBi or PKa2 versus PKo for the NB groups may indicate that the strain discrepancy observed in forest workers and patients with ACA is not biased by the coating conditions of the ELISA solid phase. WB of several selected serum specimens with discrepant reactivities revealed that this preference of PKo was mostly caused by strong reactivity with p17 (Fig. 6E to F). This is a highly immunogenic protein of strain PKo (17, 46) which is apparently not expressed by the other three strains. For sera from patients with EM lesions, frequent IgG reactivity with several proteins unique for PKo was demonstrated previously (17) (other B. afzelii strains have not been tested so far). For the NB groups, the somewhat lower correlations between B31 and each of the other three strains could be explained by the lack of OspC in B31. Thus, sera primarily recognizing OspC showed less intense reactivities with B31. However, a few individual serum specimens also showed discrepant ELISA reactivities caused by the discrepant recognition of other antigens (for example, Fig. 6C and D).

Since OspC is one of the most immunodominant antigens in the early immune response, lower correlations of B31 with the other strains were especially marked in IgM ELISAs (Fig. 5). B. burgdorferi sensu stricto B31 tends to lose OspC after many passages, contributing to its poor IgM sensitivity in all stages of LB, while strain PKa2 expressing OspC shows a considerably higher IgM sensitivity. This view is consistent with a statement of U.S. health authorities that high-passage isolates of B31 lacking OspC are not recommended for use in serological tests for LB (10).

For two serum samples selected due to discrepant reactivities in IgM ELISAs, preferential reactivity with OspC of PBi could be demonstrated by WB (Fig. 6A and B). In a study by Mathiesen et al. (24), the OspC of a B. garinii strain was also more sensitive in WB than the OspCs of a B. burgdorferi sensu stricto strain and a B. afzelii strain.

In the current study, the highest correlations in both IgG and IgM ELISAs were observed between PBi and PKa2 in all study groups. Although these two strains belong to different species and some well-characterized proteins are rather heterogeneous (20, 29, 38, 43), immune reactivity with other presumably highly conserved antigens may be compensatory.

Clinical manifestations versus asymptomatic infection; what do elevated specific IgG concentrations mean?

In general, specific IgG concentrations increase with the duration of LB (18, 34) (at least during the first months, if no antibiotic treatment is performed). Usually, in late stages, high antibody concentrations are observed. Unfortunately, however, especially in late LB, antibody activity can persist over years even if successful treatment is performed (14, 36). Thus, only limited information about the activity can be achieved by monitoring the specific IgG concentrations over the course of the disease. As already mentioned, many sera from the healthy forest workers had stronger IgG reactivities with PKo than with the other strains tested. This observation led to the assumption that assays with strains other than PKo might be more informative with regard to the activity of the disease. Therefore, the percentage of sera with OD values greater than a few exemplarily chosen levels were determined for all patients with LB as well as for the forest workers (Table 3). Significantly more sera from patients with LB than from forest workers reached OD values greater than these levels in tests with PBi, PKa2, and B31. With PKo, no significant differences were detected. Thus, it could be shown that highly elevated antibody concentrations are more likely to be associated with clinical manifestations of disease than with asymptomatic or passed infection if strains other than PKo are used. However, with respect to this evaluation it should be mentioned that the prevalences of clinical manifestations of LB in all patients with LB (n = 222) selected for this study does not represent the actual prevalences of manifestations of LB in the general population (e.g., EM is more common than NB).

A combination of a PKo assay and a test based on PBi or PKa2 might be most informative. For example, one assay could be used for screening and the other could be used for confirmation. The combination of strong PKo reactivity and weak non-PKo reactivity might be consistent with ACA or asymptomatic infection. If these results were obtained, for example, for a patient who is suffering from an atypical neurological disorder, B. burgdorferi sensu lato presumably might not be causative. However, these are unproven suggestions, and interpretation needs to be specified in detail. This might be possible only in specialized laboratories and would require intensive communication between physicians in the laboratories and in hospitals or offices.

Conclusion.

In routine testing results can vary considerably among different laboratories. Besides differences in antigen preparation and test performance, this variation may result from the use of different species of B. burgdorferi sensu lato. By generalizing the results of the current study, it might be assumed that these variations occur mainly between B. afzelii-based tests on the one hand and assays with B. burgdorferi sensu stricto or B. garinii on the other hand. However, regional differences may further influence test results. Furthermore, variations in the level of expression or a complete lack of expression of immunodominant antigens such as OspC may be critical. Since the OGP extract of PKo was the most sensitive in this study but extracts of the other strains were better able to differentiate between active disease and asymptomatic infection, we suggest that a combination of a test with a B. afzelii strain and another test with a B. garinii strain (high sensitivity with sera from patients with NB) might be most informative. If WB with PKo were used, mere detection of a p17 band without other significant bands might be grounds for suspicion of previous LB. Further investigations are necessary to elucidate this assumption.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Heidi Loy-Weigand, Gisela Lehnert, Manfred Klotz, and Klaus Ruth for excellent technical assistance, Andreas Hofmann-Lerner and Sigrun Burkert for collecting sera, and Sofia Reinecke for help with the manuscript.

We thank Gotthard Ruckdeschel and Jürgen Heesemann for generous support of this work.

REFERENCES

- 1.Assous M V, Postic D, Paul G, Nevot P, Baranton G. Western blot analysis of sera from Lyme borreliosis patients according to the genomic species of the Borrelia strains used as antigens. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1993;12:261–268. doi: 10.1007/BF01967256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J-C, Assous M, Grimont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergström S, Sjöstedt A, Dotevall L, Kaijser B, Ekstrand-Hammarström B, Wallberg C, Skogman G, Barbour A G. Diagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by an enzyme immunoassay detecting immunoglobulin G reactive to purified Borrelia burgdorferi cell components. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1991;10:422–427. doi: 10.1007/BF01968022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bradford M. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bruckbauer H, Preac-Mursic V, Fuchs R, Wilske B. Cross-reactive proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 1992;11:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02098084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bunikis J, Olsen B, Westman G, Bergström S. Variable serum immunoglobulin responses against different Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato species in a population at risk for and patients with Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1473–1478. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.6.1473-1478.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burkert S, Rössler D, Münchhoff P, Wilske B. Development of enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays using recombinant borrelial antigens for serodiagnosis of Borrelia burgdorferi infection. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;185:49–57. doi: 10.1007/s004300050014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Busch U, Hizo-Teufel C, Boehmer R, Fingerle V, Nitschko H, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V. Three species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato (B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii and B. garinii) identified from cerebrospinal fluid isolates by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis and PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1072–1078. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.5.1072-1078.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canica M M, Nato F, Du Merle L, Mazie J C, Baranton G, Postic D. Monoclonal antibodies for identification of Borrelia afzelii sp. nov. associated with late cutaneous manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 1993;25:441–448. doi: 10.3109/00365549309008525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and Association of State and Territorial Public Health Laboratory Directors. Proceedings of the Second National Conference on Serologic Diagnosis of Lyme Disease. Fort Collins, Colo: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dawson-Saunders B, Trapp R G. Basic and clinical biostatistics. San Mateo, Calif: Appleton & Lange; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dressler F, Whalen J A, Reinhardt B N, Steere A C. Western blotting in the serodiagnosis of Lyme disease. J Infect Dis. 1993;167:392–400. doi: 10.1093/infdis/167.2.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engström S M, Shoop E, Johnson R C. Immunoblot interpretation criteria for serodiagnosis of early Lyme disease. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:419–427. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.2.419-427.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feder H M, Jr, Gerber M A, Luger S W, Ryan R W. Persistence of serum antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi in patients treated for Lyme disease. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;15:788–793. doi: 10.1093/clind/15.5.788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fingerle V, Bergmeister H, Liegl G, Vanek E, Wilske B. Prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Ixodes ricinus in southern Germany. J Spiroch Tick Dis. 1994;1:41–45. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hansen K, Pii K, Lebech A-M. Improved immunoglobulin M serodiagnosis in Lyme borreliosis by using a μ-capture enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with biotinylated Borrelia burgdorferi flagella. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:166–173. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.166-173.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hauser U, Lehnert G, Lobentanzer R, Wilske B. Interpretation criteria for standardized Western blots of three European species of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1433–1444. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.6.1433-1444.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herzer P. Lyme-Borreliose. Epidemiologie, Ätiologie, Diagnostik, Klinik und Therapie. Darmstadt, Germany: Steinkopff; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hofmann A E A, Fingerle V, Hauser U, Rieth K, Wilske B. Epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis in southern Germany during the years 1987 through 1990. J Spiroch Tick Dis. 1994;1:90–97. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jauris-Heipke S, Liegl G, Preac-Mursic V, Rößler D, Schwab E, Soutschek E, Will G, Wilske B. Molecular analysis of genes encoding outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato: relationship to ospA genotype and evidence of lateral gene exchange of ospC. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1860–1866. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.7.1860-1866.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kyhse-Andersen J. Electroblotting of multiple gels: a simple apparatus without buffer tank for rapid transfer of proteins from polyacrylamide to nitrocellulose. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 1984;10:203–209. doi: 10.1016/0165-022x(84)90040-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Laemmli U K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Magnarelli L A, Anderson J F, Johnson R C, Nadelman R B, Wormser G P. Comparison of different strains of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato used as antigens in enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1154–1158. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1154-1158.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mathiesen M J, Hansen K, Axelsen N, Halkier-Sorensen L, Theisen M. Analysis of the human antibody response to outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;185:121–129. doi: 10.1007/s004300050021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Münchhoff P, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Schierz G. Antibodies against Borrelia burgdorferi in Bavarian forest workers. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1987;263:412–419. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(87)80101-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Norman G L, Antig J M, Bigaignon G, Hogrefe W R. Serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis by Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. garinii, and B. afzelii Western blots (immunoblots) J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:1732–1738. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.7.1732-1738.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peters H, Ruth K, Dopatka H-D. Einpunktquantifizierung zur Bestimmung von Borrelia-spezifischen IgG-Antikörpern in einem neuen ELISA. Lab Med. 1993;16:248–249. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Preac-Mursic V, Wilske B, Schierz G. European Borrelia burgdorferi isolated from humans and ticks: culture conditions and antibiotic susceptibility. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1986;263:112–118. doi: 10.1016/s0176-6724(86)80110-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rössler D, Eiffert H, Jauris-Heipke S, Lehnert G, Preac-Mursic V, Teepe J, Schlott T, Soutschek E, Wilske B. Molecular and immunological characterization of the p83/100 protein of various Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato strains. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1995;184:23–32. doi: 10.1007/BF00216786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schwan T G, Schrumpf M E, Karstens R H, Clover J R, Wong J, Daugherty M, Struthers M, Rosa P A. Distribution and molecular analysis of Lyme disease spirochetes, Borrelia burgdorferi, isolated from ticks throughout California. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3096–3108. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.12.3096-3108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simpson W J, Schrumpf M E, Schwan T G. Reactivity of human Lyme borreliosis sera with a 39-kilodalton antigen specific to Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1329–1337. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.6.1329-1337.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stanek G, Satz N, Strle F, Wilske B. Epidemiology of Lyme borreliosis. In: Weber K, Burgdorfer W, editors. Aspects of Lyme borreliosis. Berlin, Germany: Springer; 1993. pp. 358–370. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Steere A C. Medical progress—Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1989;321:586–596. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198908313210906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Steere A C, Grodzicki R L, Kornblatt A N, Craft J E, Barbour A G, Burgdorfer W, Schmid G P, Johnson E, Malawista S E. The spirochetal etiology of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1983;308:733–740. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198303313081301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Van Dam A P, Kuiper H, Vos K, Widjojokusumo A, De Jongh B M, Spanjaard L, Ramselaar A C P, Kramer M D, Dankert J. Different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with distinct clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:708–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weber K, Preac-Mursic V, Neubert U, Thurmayr R, Herzer P, Wilske B, Schierz G, Marget W. Antibiotic therapy of early European Lyme borreliosis and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;539:324–345. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb31867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weber K, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Thurmayr R. Azithromycin versus penicillin V for the treatment of early Lyme borreliosis. Infection. 1993;21:367–372. doi: 10.1007/BF01728915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Will G, Jauris-Heipke S, Schwab E, Busch U, Rössler D, Soutschek E, Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V. Sequence analysis of ospA genes shows homogeneity within Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto and Borrelia afzelii strains but reveals major subgroups within the Borrelia garinii species. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1995;184:73–80. doi: 10.1007/BF00221390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilske B, Bader L, Pfister H W, Preac-Mursic V. Diagnostik der Lyme-Neuroborreliose (Nachweis der intrathekalen Antikörperbildung) Fortschr Med. 1991;109:441–446. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wilske B, Busch U, Eiffert H, Fingerle V, Pfister H-W, Rössler D, Preac-Mursic V. Diversity of OspA and OspC among cerebrospinal fluid isolates of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato from patients with neuroborreliosis in Germany. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1996;184:195–201. doi: 10.1007/BF02456135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wilske B, Fingerle V, Herzer P, Hofmann A, Lehnert G, Peters H, Pfister H-W, Preac-Mursic V, Soutschek E, Weber K. Recombinant immunoblot in the serodiagnosis of Lyme borreliosis. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1993;182:255–270. doi: 10.1007/BF00579624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wilske B, Fingerle V, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris-Heipke S, Hofmann A, Loy H, Pfister H-W, Rössler D, Soutschek E. Immunoblot using recombinant antigens derived from different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1994;183:43–59. doi: 10.1007/BF00193630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilske B, Jauris-Heipke S, Lobentanzer R, Pradel I, Preac-Mursic V, Roessler D, Soutschek E, Johnson R C. Phenotypic analysis of the outer surface protein C (OspC) of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato by monoclonal antibodies: relationship to genospecies and OspA serotype. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:103–109. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.103-109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Göbel U B, Graf B, Jauris-Heipke S, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Zumstein G. An OspA serotyping system for Borrelia burgdorferi based on reactivity with monoclonal antibodies and OspA sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:340–350. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.340-350.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Jauris S, Hofmann A, Pradel I, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Will G, Wanner G. Immunological and molecular polymorphisms of OspC, an immunodominant major outer surface protein of Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2182–2191. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.5.2182-2191.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Schierz G, Gueye W, Herzer P, Weber K. Immunochemical analysis of the immune response in late manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Zentralbl Bakteriol Mikrobiol Hyg A. 1988;267:549–558. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Schierz G, Kühbeck R, Barbour A G, Kramer M. Antigenic variability of Borrelia burgdorferi. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1988;539:126–143. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1988.tb31846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wilske, B., V. Preac-Mursic, G. Schierz, G. Liegl, and W. Gueye. 1989. Detection of IgM and IgG antibodies to Borrelia burgdorferi using different strains as antigen. Zentralbl. Bakteriol. 18(Suppl.):299–309.

- 49.Wilske B, Schierz G, Preac-Mursic V, Weber K, Pfister H W, Einhäupl K. Serological diagnosis of erythema migrans disease and related disorders. Infection. 1984;12:331–337. doi: 10.1007/BF01651147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]