Abstract

The 16S rRNA gene of Haemobartonella felis was amplified by using universal eubacterial primers and was subsequently cloned and sequenced. Based on this sequence data, we designed a set of H. felis-specific primers. These primers selectively amplified a 1,316-bp DNA fragment of the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis from each of four experimentally infected cats at peak parasitemia. No PCR product was amplified from purified DNA of Eperythrozoon suis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Bartonella bacilliformis. Blood from the experimental cats prior to infection was negative for PCR products and was greatly diminished or absent 1 month after doxycycline treatment. The overall sequence identity of this fragment varied by less than 1.0% among experimentally infected cats. By taking into consideration the secondary structure of the 16S rRNA molecule, we were able to further verify the alignment of nucleotides and quality of our sequence data. In this PCR assay, the minimum detectable number of H. felis organisms was determined to be between 50 and 704. The potential usefulness of restriction enzymes DdeI and MnlI for distinguishing H. felis from closely related bacteria was examined. This is the first report of the utility of PCR-facilitated diagnosis and discrimination of H. felis infection in cats.

Haemobartonella felis is the causative agent of feline infectious anemia, a contagious disease of cats first recognized in the United States in 1953 (9). Nonetheless, our knowledge about this organism remains largely incomplete. H. felis is a short, rod- or coccus-shaped, gram-negative organism which attaches to and grows on the surfaces of feline erythrocytes. Acute disease in the cat is associated with parasitemia and a severe, sometimes fatal, hemolytic anemia; however, in chronically infected cats, parasitemia is low or absent and the cat may be asymptomatic. This disease is considered a frequent cause of anemia in cats by some authors and an uncommon disease by others. Studies have estimated the prevalence of this parasite in the feline population to vary from 0.9 to 28% (5).

H. felis has not been successfully grown in agar or cell cultures. The only readily available method for diagnosing H. felis infection in cats is microscopic identification of organisms attached to the surfaces of erythrocytes in Wright-Giemsa-stained peripheral blood smears. This is a highly insensitive method for detecting H. felis infection (34). The diagnosis of hemobartonellosis is complicated by the lack of a readily identifiable parasitemia in latent and chronic infections, as well as the rapid loss of parasitemia at the time of onset of clinical signs in acutely infected cats (16). The lack of an efficient test for diagnosing acute and chronic H. felis infections has resulted in tremendous controversy concerning the true impact of this disease in cat populations.

Relman et al. (29), Maurin et al. (20), Regnery et al. (27), and Wilson et al. (38) showed that disease-causing, uncultured microorganisms can be detected in clinical samples, such as peripheral blood, by PCR amplification of their 16S rRNA genes. Since the nucleotide sequences found in 16S rRNA genes vary in an orderly fashion throughout the phylogenetic tree, these sequences have also proven very useful for the study of molecular evolution. Sequences in this gene that are conserved throughout the eubacterial kingdom can be used as targets for primer-directed DNA amplification of the 16S rRNA gene; however, this amplification lacks specificity. Nonetheless, these universal primer sites are highly conserved among eubacteria and are not found in eucaryotes, archaebacteria, or mitochondria and, thus, should amplify only bacterial 16S rRNA (6, 37–39). By identifying hypervariable regions within the 16S rRNA gene, primers which are species specific can be designed and evaluated for their potential as a diagnostic tool (7, 12, 32).

In this study, we used universal primers to amplify nearly the entire 16S rRNA sequence of H. felis and organisms most closely related to H. felis. The PCR products for H. felis were cloned, sequenced, and analyzed (1, 8, 18). The sequencing data were used to identify hypervariable regions within the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis and to design a species-specific primer set. We evaluated the specificities and sensitivities of these primers in a PCR for detection and identification of H. felis. Additionally, to confirm the identity of our PCR product, we performed Southern hybridization against genomic DNA (33). By exploitation of the presence of restriction fragment length polymorphisms (RFLP) in the 16S rRNA gene, several groups have successfully differentiated members of bacterial genera from one another (2, 13, 26). An alternative scheme for differentiation of H. felis from other bacterial genera based on restriction fragment analysis of this gene was also investigated.

Our results suggest that the use of an H. felis-specific primer set in PCR-based amplification of the 16S rRNA gene allows for detection and identification of infected cats. The application of this procedure in future work should significantly improve our understanding of the impact of this disease in cat populations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals.

Four adult cats obtained from a commercial vendor were confirmed to be free of hemoparasites by examination of Wright-Giemsa-stained blood smears. EDTA-anticoagulated blood was aseptically collected for PCR assaying from each cat prior to experimental infection with H. felis and following intravenous infection with either fresh or frozen whole blood from an infected cat. A 1-ml volume of EDTA blood obtained from a cat naturally infected with H. felis was used to infect the first experimental cat. Subsequent cats were infected serially with blood collected from the previous cat during the first parasitemic episode. Rectal temperatures and peripheral blood smears were monitored daily. Treatment with doxycycline (2.5 mg/kg of body weight orally twice daily for 21 days) was begun during the first parasitemic episode, and thereafter EDTA-anticoagulated blood samples were collected at weekly intervals.

Bacterial strains.

Bacteria used to evaluate the PCR assay included Eperythrozoon suis, Mycoplasma genitalium, and Bartonella bacilliformis. Based on our sequence comparisons and phylogenetic analysis of the 16S rRNA gene, as well as a review of the literature (21, 30), E. suis and M. genitalium were identified as organisms closely related to H. felis (GenBank accession nos. AF02394 and U88656 for E. suis and X77334 for M. genitalium). We also included another erythrocyte parasite, B. bacilliformis, which is a species previously reported to be closely related to H. felis based on 5S rRNA sequence data (23). E. suis from an experimentally infected pig was kindly provided by James Zachary at the University of Illinois. The other organisms used included H. felis-Bourbon, H. felis-CC, H. felis-Dan, and H. felis-Jack from four experimentally infected cats and B. bacilliformis and M. genitalium from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC; Rockville, Md.; http//www.atcc.org) culture stocks 35685 and 49895, respectively.

DNA extraction.

DNA was extracted by a method adapted from that described by van Soolingen et al. (35). Total DNA was extracted from leukocyte-poor blood of cats experimentally infected with H. felis, from whole blood from an experimentally infected pig, and from ATCC bacterial culture stocks (one-half the amount of the lyophilized culture was solubilized in 400 μl of Tris-EDTA [10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8; 1 mM EDTA, pH 8]). To 400 μl of blood or solubilized bacterial culture, 10 μl of lysozyme (50 mg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) was added. The mixtures were vortexed and incubated for 1 h at 37°C. Then, 6 μl of proteinase K (10 mg/ml; Sigma) and 70 μl of 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate were added, and the solution was incubated at 65°C for an additional 10 min. Then, 100 μl of 5 M NaCl and 160 μl of 5% hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) were added, and the solution was incubated for 10 min at 65°C. Finally, DNA was then purified by phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation. The pellet was resuspended in 50 μl of sterile H2O.

A negative control (all of the reagents without a DNA sample) was included in each experiment to ensure that none of the extraction buffers or reagents were contaminated with target DNA.

PCR.

Reaction mixtures were prepared under a hood which was subsequently irradiated by UV light. To avoid contamination, a separate set of pipettes and aerosol-guarded tips were used exclusively for preparation of reaction mixtures. Standard amplification reactions were carried out with a Perkin-Elmer GeneAmp PCR 2400 system. Fisher Taq polymerase (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, Pa.) was used in amplification reactions consisting of 10 min at 94°C; 33 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min; and a final elongation step at 72°C for 7 min. The conditions used for amplification with species-specific primers were identical to those described above, except that the primer hybridization temperature was 54°C for 1 min. The universal primers (29, 36, 39) and species-specific primers for 16S rRNA amplification are listed in Table 1. The universal primer set fHf1 and rHf2 includes SalI and BamHI sites, respectively, which were used for cloning.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used for 16S rRNA amplification

| Primer namea | Primer sequence (5′-3′) | Positions (based on H. felis sequence) | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| fHf1 | acg cgt cga cag agt ttg atc ctg gct | 1→17 | Gibco-BRLb |

| rHf2 | cgc gga tcc gct acc ttg tta cga ctt | 1435→1450 | Gibco-BRL |

| fHf5 | agc agc agt agg gaa tct tcc ac | 335→357 | IDTc |

| rHf6 | tgc acc acc tgt cac ctc gat aac | 986→1009 | IDT |

| H. felis-f1 | gac ttt ggt ttc ggc caa gg | 61→79 | IDT |

| H. felis-r2 | atg tat ttt taa atg ccc act c | 1356→1377 | IDT |

The PCR-amplified products were detected by electrophoresis on a 0.8% (wt/vol) gel in Tris-borate-EDTA buffer. A 1-kb DNA ladder (Lambda DNA/EcoRI and HindIII Markers; Promega Corp., Madison, Wis.; http://www.promega.com) was included as a DNA size standard. Gels containing 1 ng of ethidium bromide per ml were photographed by standard procedures.

Prior to cloning, appropriate size fragments were purified with the Wizard PCR Preps Purification system (Promega). Purified fragments were then cloned into pGEM T Vector (Promega). Plasmids containing proper size inserts were prepped and purified for sequencing using the PERFECT prep Plasmid DNA Preparation kit (5′-3′ Inc., Boulder, Colo.). All clones were sequenced in both sense and antisense directions by a dideoxy terminator method with a Perkin-Elmer–Applied Biosystems automated sequencer at the Genetic Engineering Facility of the University of Illinois Biotechnologies Center.

Sequence analysis.

The 16S rRNA sequence data were analyzed at the Ribosomal Database Project to find closely related bacterial species and were checked to determine if the sequence had a chimeric nature (18). The sequence was then aligned and compared with selected GenBank sequences (1) of closely related bacteria by using PILEUP, PRETTY, and Evolutionary Analysis from the Genetics Computer Group’s Sequence Analysis Package, version 8.1 (8). Primers that were H. felis specific were selected from known hypervariable regions, V1 and V9, of the 16S rRNA gene. The primers were designed to give the largest possible fragment of the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis and in a region in which the sequence showed divergence from the closest related bacteria (4).

Sensitivity (detection limit) of PCR.

To determine the approximate minimum parasitemia that could be detected by PCR-specific amplification of the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis, serial fivefold dilutions beginning with a 1:30 dilution of genomic DNA extracted from blood with known parasitemia were prepared. Since H. felis cannot be cultured, a competitive, quantitative PCR method developed by Zachar et al. was also used to estimate the amount of input H. felis (14, 40). Briefly, competitive, quantitative PCR was performed by adding constant amounts of a constructed, internal control DNA to the PCR amplification reaction mixtures containing serial dilutions of H. felis target DNA. The internal control for quantitative detection of H. felis was constructed by introducing a deletion in an amplified fragment from the 16S rRNA gene. Following PCR, the amounts of products generated by the target and competitor sequences were analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. A standard curve was constructed by plotting the logarithm of the ratio of the intensity of the PCR product of the target sequence to that of the competitor band against the logarithm of the amount of input target DNA. With this curve, the amount of an unknown DNA target was determined. A range for the amount of target DNA was estimated based on the assumption that the number of genes coding for the 16S rRNA can vary from 1 to 14 copies.

Specificity of PCR.

DNAs extracted from H. felis, B. bacilliformis, M. genitalium, and E. suis were used as templates in individual PCRs with primers H. felis-f1 and H. felis-r2. The specificity test was performed with E. suis and M. genitalium DNA because of the close phylogenetic relationship to H. felis (21). We also included B. bacilliformis, a species previously reported to be closely related to H. felis based on 5S rRNA sequence data (23).

Southern hybridization of PCR products and genomic DNA of H. felis.

PCR-amplified products and genomic DNA (three separate genomic DNA extracts were pooled and digested with HindIII for each preparation) extracted from the blood of experimental cats before H. felis infection, at peak parasitemia, and posttreatment were subjected to electrophoresis as previously described, denatured, transferred to Hybond-N+ membranes (Amersham, Arlington Heights, Ill.), and probed by standard techniques (33). Membranes were incubated for 1 h at 60°C in prehybridization solution. The PCR probe generated with the primers fHf5 and rHf6 listed in Table 1 was purified with the Magic Preps Purification System (Promega) and labeled with the enhanced chemiluminescence-nucleic acid labeling and detection system (Amersham). After 12 h or overnight hybridization at 60°C, the membrane was blocked, antibody bound, and then autoradiographed.

RFLP.

The PCR products obtained by amplification of the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis, B. bacilliformis, M. genitalium, and E. suis with fHf1 and rHf2 were differentiated by RFLP. Two restriction enzymes, DdeI and MnlI (New England Biolabs, Beverly, Mass.), were used according to the manufacturer’s recommendations to digest the PCR products. DdeI recognizes the sequence 5′-C▾TNAG-3′ and cleaves at the position indicated by the arrowhead (19). The cleavage site recognized by MnlI has the structure 5′-(CCTCN)7-3′ (3). Post-PCR mixes containing amplified 16S rRNA genes were used directly as templates for restriction endonuclease digestion. Following incubation, the products of digestion were resolved by electrophoresis and visualized as previously described.

RESULTS

PCR with universal primers.

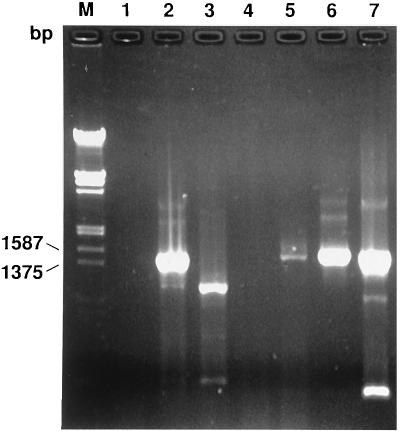

Using the universal primers fHf1 and rHf2 (listed in Table 1), we were able to amplify an approximately 1,500-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA from a variety of genera belonging to the eubacterial group, indicating that the DNA preparations contained DNA suitable for amplification. Several other groups have demonstrated priming of most eubacteria with these universal primer sites (29, 36, 38). As demonstrated in Fig. 1, DNAs extracted from blood of cats experimentally infected with H. felis during a parasitemic episode (lane 2), as well as B. bacilliformis (lane 5), M. genitalium (lane 6), and E. suis (lane 7), gave bands of the expected sizes when they were amplified with this set of primers. Several bands of inappropriate size but lesser in intensity were also produced when H. felis, M. genitalium, and E. suis (lanes 2, 6, and 7, respectively) were used as templates for amplification. When negative controls, DNA that had been extracted from the blood of cats prior to experimental infection (lane 1) or water (lane 4), were used as target substrates for PCR, no amplification products were generated. When DNA was extracted following doxycycline treatment, a band of the appropriate size was not observed with primers fHf1 and rHf2. However, several bands of inappropriate sizes were observed (lane 3).

FIG. 1.

Amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA with a conserved primer set, fHf1 and rHf2. Lanes: 1, 2, and 3, amplified DNA products extracted from cat blood before experimental infection with H. felis, during a heavily parasitemic episode, and following treatment, respectively; 4, water-DNA preparation; 5, B. bacilliformis; 6, M. genitalium; 7, E. suis; M, 1-kb DNA size markers cut with EcoRI and HindIII.

PCR products of the predicted sizes for the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis were gel purified, cloned into a plasmid vector, and used to transform Escherichia coli. Based on sequence analysis from several clones, an H. felis-specific primer set was identified, synthesized (H. felis-f1 and H. felis-r2 [Table 1]), and used to more confidently amplify the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis only.

Specificity of PCR.

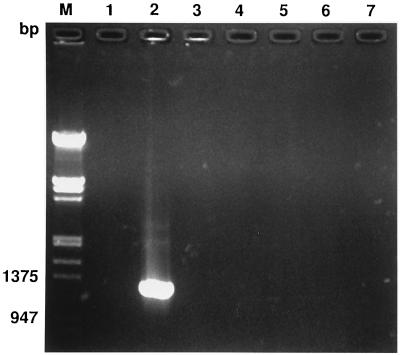

The specificity of the H. felis-f1 and -r2 primer set was examined with DNAs extracted from noninfected cat blood and cat blood experimentally infected with H. felis, from whole blood from a pig experimentally infected with E. suis, and from ATCC bacterial culture stocks of M. genitalium and B. bacilliformis. The expected 1,316-bp fragment of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified with H. felis DNA but was not amplified from the DNAs of these other organisms. Amplified products of the predicted sizes were not generated from DNA extracts of blood samples from noninfected cats and were greatly diminished or absent following doxycycline treatment (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Amplification of bacterial 16S rRNA with the H. felis-specific primer set H. felis-f1 and H. felis-r2. Lanes: 1, 2, and 3, amplified DNA products extracted from cat blood before experimental infection with H. felis, during a heavily parasitemic episode, and following treatment, respectively; 4, water-DNA preparation; 5, B. bacilliformis; 6, M. genitalium; 7, E. suis; M, 1-kb DNA size markers cut with EcoRI and HindIII.

We computer aligned this 1,316-bp fragment with our 1,442-bp sequence amplified using universal primers and with previously defined sequences. The overall sequence identity of this fragment varied by less than 1.0% among the four experimentally infected cats and by 1.9% compared to the 1,442-bp fragment amplified with the universal primers. By taking into consideration the secondary structure of the 16S rRNA molecule (data not shown), we were able to further verify the alignment of nucleotides and quality of our sequence data (15).

Sensitivity (minimal detection limit) of PCR.

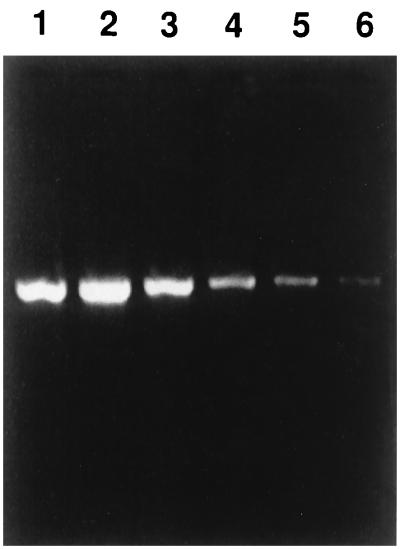

H. felis DNA was purified from cat blood with a total erythrocyte count of 3.6 × 106 cells per μl and 68% parasitemia. Therefore, there were 2.5 × 106 H. felis-infected erythrocytes per μl of blood used for DNA extraction. To determine the threshold for detection of infected erythrocytes, DNA was extracted from 400 μl of blood, and fivefold serial dilutions were amplified (Fig. 3) by PCR with H. felis-specific primers. The expected 1,316-bp fragment was detected to a 1:93,750 dilution. Based on competitive PCR analysis for quantification of target DNA, the estimated input of H. felis organisms in the undiluted PCR mixture was between 1.6 × 105 and 2.2 × 106 organisms. Therefore, the minimum detectable number of organisms in the 1:93,750 dilution was between 50 and 704.

FIG. 3.

Threshold of detection for H. felis in blood samples by PCR. Results of agarose gel electrophoresis of amplified DNA from fivefold serial dilutions of PCR preparation. The 16S rRNA gene was amplified by PCR with the primer set H. felis-f1 and H. felis-r2. Lanes 1 to 6, PCR preparations diluted 1:30, 1:150, 1:750, 1:3,750, 1:18,750, and 1:93,750, respectively.

Southern hybridization of PCR products and genomic DNA of H. felis.

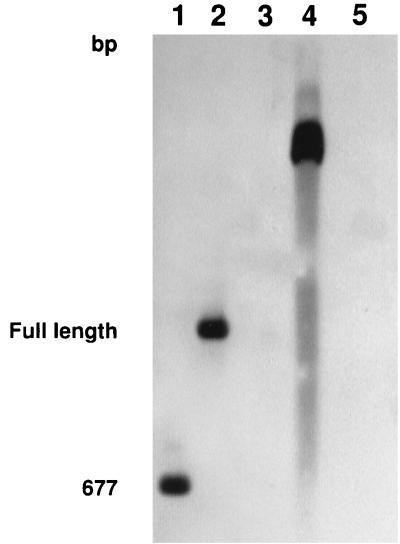

To confirm the identity of our PCR product, we performed Southern hybridization against genomic DNA that had been digested with HindIII and PCR products using a 674-bp DNA probe of the 16S rRNA gene of H. felis (Fig. 4). The PCR probe was generated with the fHf5 and rHf6 primers. The PCR products generated with primer sets fHf1 and rHf2 (lane 2) and fHf5 and rHf6 (lane 1) hybridized with this probe. The 674-bp DNA probe also strongly hybridized with genomic DNA (lane 4). There was no hybridization seen with genomic DNA samples from the cats before experimental infection or following treatment (lanes 3 and 5, respectively). In addition, the H. felis probe failed to hybridize with blotted PCR products from bacteria other than H. felis, which had been amplified with our H. felis-specific primers (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Southern blot of PCR products of the 16S rRNA gene and genomic DNA. Blots were probed with a 674-bp fragment of H. felis. Lanes: 1, PCR product amplified with fHf5 and rHf6; 2, PCR product amplified with fHf1 and rHf2; 3, genomic DNA from blood of a cat before infection with H. felis; 4, genomic DNA from blood of a cat infected with H. felis; 5, genomic DNA from blood of a cat following doxycycline treatment for H. felis infection.

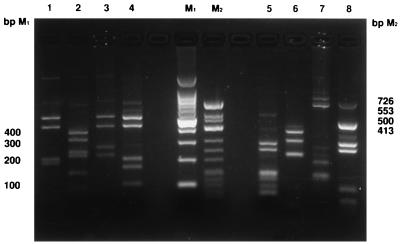

RFLP.

DdeI and MnlI were previously shown to be useful for differentiation of 16S rRNA gene amplicons derived from Bartonella species (2). Examination of the aligned sequences for H. felis, E. suis, and M. genitalium suggested that the use of these endonucleases might be extended to differentiate these organisms from one another and from Bartonella species. Examination of the RFLP patterns generated by DdeI and MnlI digestion of PCR products of the 16S rRNA genes of these organisms confirmed this prediction, and the profiles obtained are presented in Fig. 5. DdeI generated similar, approximately 400- and 500-bp fragments for H. felis, M. genitalium, and E. suis; however, these fragments were absent in B. bacilliformis. The presence of a 100-bp fragment distinguished E. suis from both M. genitalium and H. felis. Digestion of the 16S rRNA fragments with MnlI generated two distinct bands corresponding to approximately 250- and 300-bp fragments for H. felis and E. suis, respectively; however, these bands were not present in B. bacilliformis and M. genitalium. An approximately 400-bp restriction fragment was distinct in the 16S rRNA gene of E. suis.

FIG. 5.

Restriction profiles obtained after DdeI and MnlI digestion of the 16S rRNA gene amplified with the universal primer set fHf1 and rHf1. Lanes: 1 to 4, DdeI digests of H. felis, B. bacilliformis, M. genitalium, and E. suis, respectively; 5 to 8, MnlI digests of H. felis, B. bacilliformis, M. genitalium, and E. suis, respectively; M1 and M2, molecular size markers (base pair values are indicated in the left and right margins).

DISCUSSION

Our understanding of H. felis and the disease it causes has been severely hampered by our inability to cultivate this organism. In the absence of cultivated organism, Koch’s postulates are difficult to fulfill and it is nearly impossible to develop a diagnostic assay based on specific humoral or cellular immune responses (10). In this study, we applied a technique that circumvented the need to isolate or grow H. felis but that nonetheless gave us valuable information about its phylogenetic relationship and enabled us to develop a diagnostic test for the disease. The data we present herein describe the development and evaluation of a PCR assay for detecting H. felis infection in cats.

A species-specific PCR assay that used primers based on our original 16S rRNA sequence of H. felis was developed. Our preliminary work of specificity has shown that this primer set does not anneal to DNA from either of two hemotropic parasites, E. suis and B. bacilliformis, or a genetically related organism, M. genitalium. Furthermore, the H. felis probe failed to hybridize with blotted PCR products from bacteria, other than H. felis, that had been amplified with our H. felis-specific primers.

Bacterial organisms that use erythrocytes as their primary site of development are fairly frequently encountered in veterinary species. Although the differentiation of Haemobartonella from Eperythrozoon is reported to be arbitrary and based on subtle morphologic criteria (24, 31, 37), there was sufficient dissimilarity in the 16S rRNA nucleotide sequences to distinguish H. felis from E. suis. In humans, only B. bacilliformis, the causative agent of Oroya fever, which is recognized only in the Andes Mountain valleys, has been described. There have also been rare reports of hemotropic procaryotic microorganisms infecting humans in the United States (31).

H. felis was originally classified in the order Rickettsiales as a member of the family Anaplasmataceae based on its biologic and phenotypic characteristics. However, unlike other rickettsial organisms, H. felis does not exhibit an obligate intracellular growth pattern (24). More recently, a close phylogenetic relationship of H. felis to Bartonella henselae, the organism that causes cat scratch fever, was considered possible based on the nucleotide sequence of the 5S rRNA gene (GenBank accession no. L24488) (23). Cats have been identified as a major reservoir for B. henselae. Regnery et al. and Koehler et al. reported that B. henselae could be isolated from the blood of a naturally infected cat and also demonstrated that cats remain bacteremic for months; however, apparently the infection in cats is asymptomatic (17, 28). Nonetheless, by employing PCR assays we were able to distinguish these two genera. In fact, based on 16S rRNA sequence data, these two organisms were found to be unrelated. Using a set of genus-specific primers for Bartonella species, Minnick was subsequently unable to amplify a PCR product from H. felis DNA of one of the experimentally infected cats in this study. This primer set reacts with all Bartonella species tested to date, suggesting that H. felis is not a Bartonella species. The H. felis-infected cats from which the previously reported 5S rRNA sequence was amplified may have been coincidentally infected with B. henselae (22).

Sequence comparison of the 16S rRNA genes from bacteria is a powerful tool for determining phylogenetic relationships. The phylogenetic clustering of H. felis to the genus Mycoplasma is consistent with a variety of characteristics associated with this genus (21, 30). Like Mycoplasma species, H. felis cells are wall-less procaryotes that lack flagellae, and despite resistance to penicillin and its analogs, these organisms are susceptible to doxycyclines (24). Despite a sequence homology of nearly 80% to M. genitalium, the PCR assay was able to specifically amplify only H. felis.

Use of an RFLP identification scheme such as the one described in this study permits the identification of 16S rRNA amplicons. However, the method described in this study incorporated universal eubacterial primers; thus, the presence of contaminants in clinical materials could be problematic. To develop a diagnostically useful RFLP, it would be necessary to develop a primer set that is specific for the genus Haemobartonella.

We believe that the PCR method that we have developed for H. felis will make it possible for us to investigate the role that this organism plays in disease in cats. The limits of detection of this PCR assay, between 50 and 704 organisms, as determined herein are comparable to what has been reported by others for a PCR-based assay (11, 25). The method is easy to perform and lends itself to routine analysis. The diagnostic potential of our PCR assay is currently undergoing further evaluation with clinical blood specimens. In addition, we are presently attempting to use this assay to answer questions related to the prevalence of the organism in cat populations and risk factors associated with positive PCR assay results.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bilofsky H F, Burks C. The GenBank® genetic sequence data bank. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:1861–1863. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.5.1861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birtles R J. Differentiation of Bartonella species using restriction endonuclease analysis of PCR-amplified 16S rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1995;129:261–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1995.tb07590.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brinkley P, Bautista D S, Graham F L. The cleavage site of restriction endonuclease MnlI. Gene. 1991;100:267–268. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(91)90379-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown, D. R., G. S. McLaughlin, and M. B. Brown. Taxonomy of feline mycoplasmas Mycoplasma felifaucium, Mycoplasma feliminutum, Mycoplasma felis, Mycoplasma gateae, Mycoplasma leocaptivus, Mycoplasma leopharyngis, and Mycoplasma simbae by 16S rRNA gene sequence comparisons. Int. J. Syst. Bacteriol. 45:560–564. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Carney H C, England J J. Feline hemobartonellosis. In: Hoskins J D, Loar A S, editors. The veterinary clinics of North America: small animal practice (feline infectious diseases). W. B. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Company; 1993. pp. 79–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole S T, Girons I S. Bacterial genomics. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:139–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00084.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dauga C, Miras I, Grimont P A D. Identification of Bartonella henselae and B. quintana 16S rDNA sequences by branch-, genus-, and species-specific amplification. J Med Microbiol. 1996;45:192–199. doi: 10.1099/00222615-45-3-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devereux J, Haeberli P, Smithies O. A comprehensive set of sequence analysis programs for the VAX. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:387–395. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.1part1.387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flint J C, Moss L C. Infectious anemia in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 1953;122:45–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fredricks D N, Relman D A. Sequence-based identification of microbial pathogens: a reconsideration of Koch’s postulates. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1996;9:18–33. doi: 10.1128/cmr.9.1.18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gale K R, Dimmock C M, Gartside M, Leatch G. Anaplasma marginale: detection of carrier cattle by PCR-ELISA. Int J Parasitol. 1996;26:1103–1109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcia M, Jackwood M W, Head M, Levisohn S, Kleven S H. Use of species-specific oligonucleotide probes to detect Mycoplasma gallisepticum, M. synoviae, and M. iowae PCR amplification products. J Vet Diagn Invest. 1996;8:56–63. doi: 10.1177/104063879600800109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Garcia M, Jackwood M W, Levisohn S, Kleven S H. Detection of M. gallisepticum, M. synoviae, and M. iowae by multispecies PCR and restriction fragment length polymorphism. Avian Dis. 1995;39:606–616. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilliland G, Perrin S, Blanchard K, Bunn H F. Analysis of cytokine mRNA and DNA: detection and quantitation by competitive polymerase chain reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2725–2729. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.7.2725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gutell R R. Collection of small subunit (16S- and 16S-like) ribosomal RNA structures: 1994. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3502–3507. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.17.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harvey J W, Gaskin J M. Experimental feline haemobartonellosis. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 1977;13:28–38. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Koehler J E, Glaser C A, Tappero J W. Rochalimaea henselae infection: a new zoonosis with the domestic cat as reservoir. JAMA. 1994;271:531–535. doi: 10.1001/jama.271.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Maidak B L, Olsen G J, Larsen N, Overbeek R, McCaughey M J, Woese C R. The ribosomal database project (RDP) Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:82–85. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Makula R A, Meagher R B. A new restriction endonuclease from the anaerobic bacterium, Desulfovibrio desulfuricans, Norway. Nucleic Acids Res. 1980;8:3125–3131. doi: 10.1093/nar/8.14.3125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Maurin M, Roux V, Stein A, Ferrier F, Viraben R, Raoult D. Isolation and characterization by immunofluorescence, sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, Western blot, restriction fragment length polymorphism-PCR, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of Rochalimaea quintana from a patient with bacillary angiomatosis. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:1166–1171. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.5.1166-1171.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Messick, J. B., L. M. Berent, and S. K. Cooper. 1996. Unpublished data.

- 22.Minnick, M. 1997. Personal communication.

- 23.Minnick M F, Strange J C, Grahn J C, Pedersen N C. Nucleotide sequence of the 5S ribosomal RNA gene of Haemobartonella felis suggest a close phylogenetic relationship to the Rochalimaea genus. GenBank accession no. L24488. 1993. Unpublished data. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moulder J W. Order I. Rickettsiales Gieszczkiewicz 1939, 25. In: Buchanan R E, Gibbons N E, editors. Bergey’s manual of determinative bacteriology. 8th ed. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1974. pp. 882–890. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Peter T F, Deem S L, Barbet A F, Norval A I, Simbi G H, Kelly P J, Mahan S M. Development and evaluation of PCR assay for detection of low levels of Cowdria ruminantium infection in Amblyomma ticks not detected by DNA probe. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:166–172. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.166-172.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ralph D, Postic D, Baranton G, Pretzman C, McClelland M. Species of Borellia distinguished by restriction site polymorphism in 16S 16S rRNA genes. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;111:239–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Regnery R L, Anderson B E, Clarridge III J E, Rodriguez-Barradas M C, Jones D C, Carr J H. Characterization of a novel Rochalimaea species, R. henselae sp. nov., isolated from blood of a febrile, human immunodeficiency virus-positive patient. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:265–274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.265-274.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Regnery R L, Martin M, Olson J G. Naturally occurring Rochalimaea henselae infection in domestic cat. Lancet. 1992;340:557–558. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91760-6. . (Letter.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Relman D A, Loutit J S, Schmidt T M, Falkow S, Tompkins L S. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis. An approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1573–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rikihisa Y, Kawahara M, Wen B, Kociba G, Fuerst P, Kawamori F, Suto C, Shibata S, Futohashi M. Western immunoblot analysis of Haemobartonella muris and comparison of 16S rRNA gene sequences of H. muris, H. felis, and Eperythrozoon suis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:823–829. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.823-829.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ristic N, Kreier J P. Hemotropic bacteria. N Engl J Med. 1979;301:937–939. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197910253011708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schriefer M E, Sacci J B, Jr, Dumler J S, Bullen M G, Azad A F. Identification of a novel rickettsial infection in a patient diagnosed with murine typhus. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:949–954. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.4.949-954.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Southern E M. Detection of specific sequences among DNA fragments separated by gel electrophoresis. J Biol Chem. 1975;98:503–517. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(75)80083-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Turner C M R, Bloxham P A, Cox F E G, Turner C B. Unreliable diagnosis of Haemobartonella felis. Vet Rec. 1986;119:534–535. doi: 10.1136/vr.119.21.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.van Soolingen D, DeHaas P E W, Hermans P W M, van Embden J D A. DNA fingerprinting of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Enzymol. 1994;235:196–205. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(94)35141-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weisburg W G, Barns S M, Pelletier D A, Lane D J. 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Weiss E, Moulder J W. Order I. Rickettsiales Gieszczkiewicz 1939, 25AL. In: Krieg N R, Holt J G, editors. Bergey’s manual of systematic bacteriology. Vol. 1. Baltimore, Md: The Williams & Wilkins Co.; 1984. pp. 687–729. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilson K H, Blitchington R B, Greene R C. Amplification of bacterial 16S ribosomal DNA with polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1990;28:1942–1946. doi: 10.1128/jcm.28.9.1942-1946.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woese C R. Bacterial evolution. Microbiol Rev. 1987;51:221–271. doi: 10.1128/mr.51.2.221-271.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zachar V, Thomas R A, Goustin A S. Absolute quantification of target DNA: a simple competitive PCR for efficient analysis of multiple samples. Nucleic Acids Res. 1993;21:2017–2018. doi: 10.1093/nar/21.8.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]