Abstract

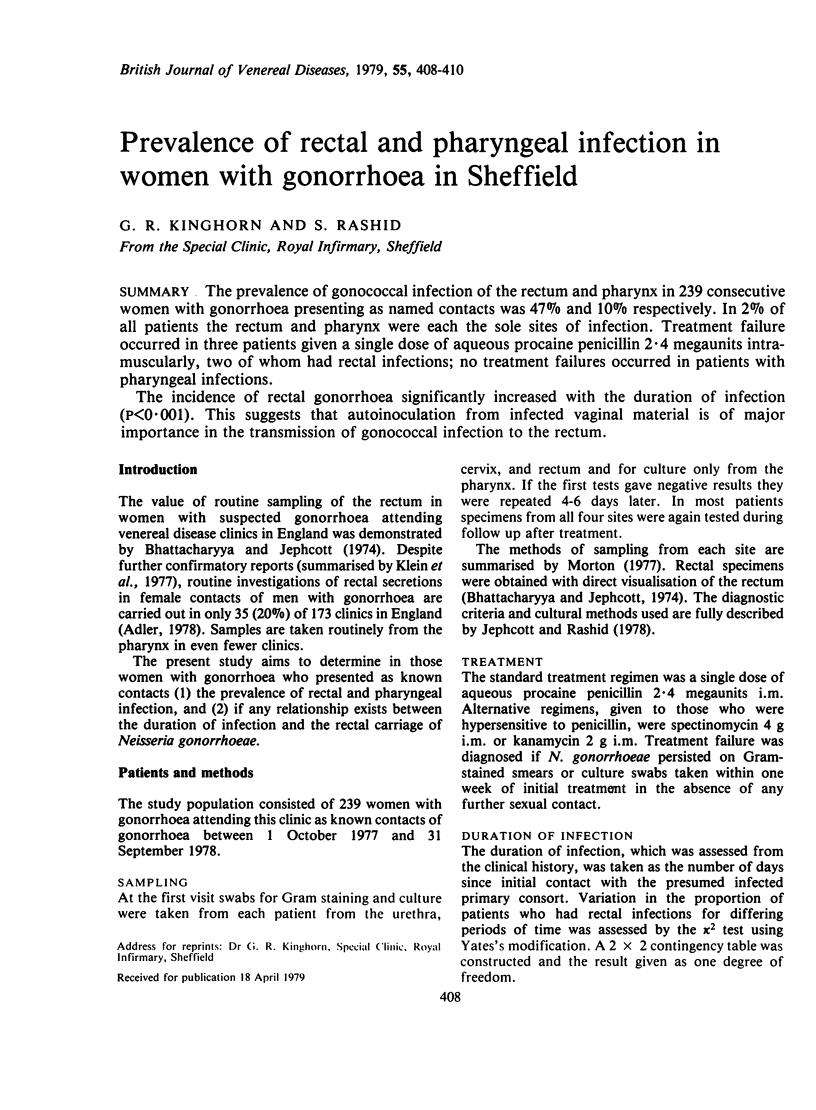

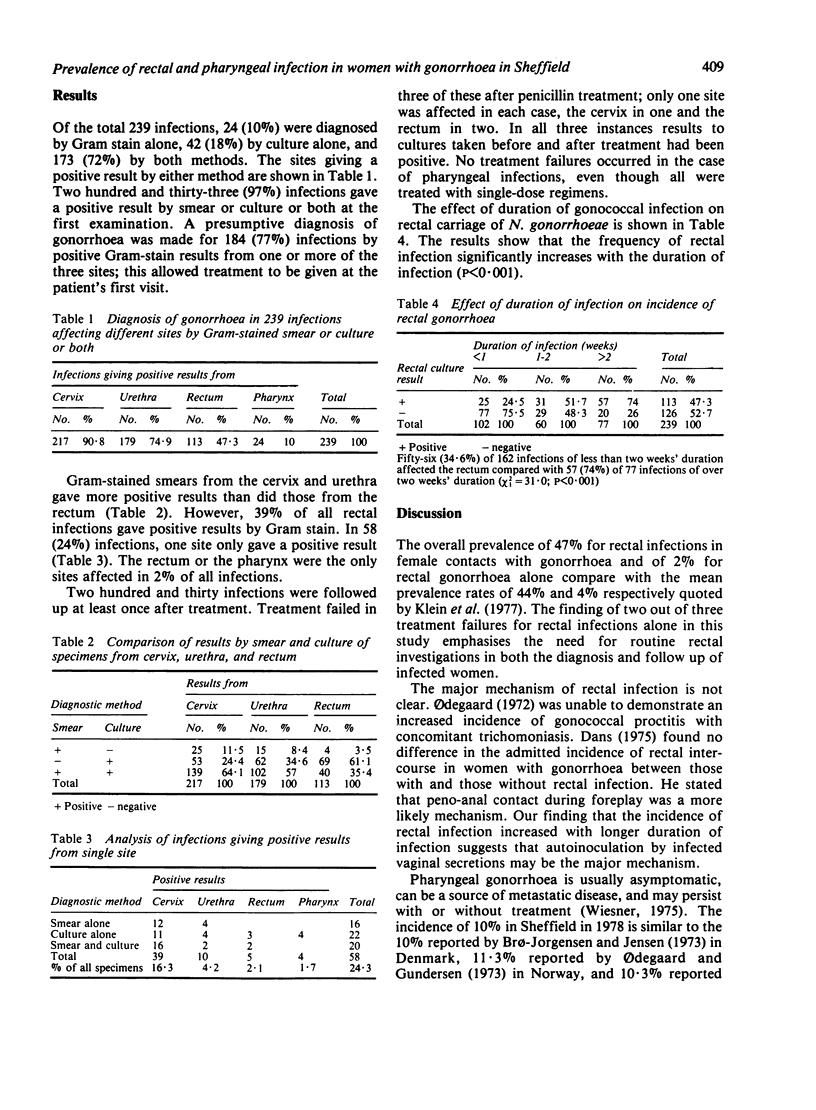

The prevalence of gonococcal infection of the rectum and pharynx in 239 consecutive women with gonorrhoea presenting as named contacts was 47% and 10% respectively. In 2% of all patients the rectum and pharynx were each the sole sites of infection. Treatment failure occurred in three patients given a single dose of aqueous procaine penicillin 2.4 megaunits intramuscularly, two of whom had rectal infections; no treatment failures occurred in patients with pharyngeal infections. The incidence of rectal gonorrhoea significantly increased with the duration of infection (P less than 0.001). This suggests that autoinoculation from infected vaginal material is of major importance in the transmission of gonococcal infection to the rectum.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Adler M. W. Diagnostic treatment and reporting criteria for gonorrhoea in sexually transmitted disease clinics in England and Wales. 1: Diagnosis. Br J Vener Dis. 1978 Feb;54(1):10–14. doi: 10.1136/sti.54.1.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharyya M. N., Jephcott A. E. Diagnosis of gonorrhoea in women. Role of the rectal sample. Br J Vener Dis. 1974 Apr;50(2):109–112. doi: 10.1136/sti.50.2.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bro-Jorgensen A., Jensen T. Gonococcal pharyngeal infections. Report of 110 cases. Br J Vener Dis. 1973 Dec;49(6):491–499. doi: 10.1136/sti.49.6.491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dans P. E. Gonococcal anogenital infection. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1975 Mar;18(1):103–119. doi: 10.1097/00003081-197503000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson D. H., Jephcott A. E. Penicillin sensitivity of gonococci. An evaluation of monitoring as an index of epidemiological control. Br J Vener Dis. 1976 Aug;52(4):253–255. doi: 10.1136/sti.52.4.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jephcott A. E., Rashid S. Improved management in the diagnosis of gonorrhoea in women. Br J Vener Dis. 1978 Jun;54(3):155–159. doi: 10.1136/sti.54.3.155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein E. J., Fisher L. S., Chow A. W., Guze L. B. Anorectal gonococcal infection. Ann Intern Med. 1977 Mar;86(3):340–346. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-86-3-340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegaard K., Gundersen T. Gonococcal pharyngeal infection. Br J Vener Dis. 1973 Aug;49(4):350–352. doi: 10.1136/sti.49.4.350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odegaard K. Trichomonas vaginalis infection and rectal gonorrhoea in women. Acta Derm Venereol. 1972;52(4):326–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner P. J., Tronca E., Bonin P., Pedersen A. H., Holmes K. K. Clinical spectrum of pharyngeal gonococcal infection. N Engl J Med. 1973 Jan 25;288(4):181–185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197301252880404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]