Abstract

Secondary AML (sAML), defined by either history of antecedent hematologic disease (AHD) or prior genotoxic therapy (tAML), is classically regarded as having worse prognosis than de novo disease (dnAML). Clinicians may infer a new AML diagnosis is secondary based on a history of antecedent blood count (ABC) abnormalities in the absence of known prior AHD, but whether abnormal ABCs are associated with worse outcomes is unclear. Secondary-type mutations have recently been incorporated into the European LeukemiaNet (ELN) 2022 guidelines as adverse-risk features, raising the question of whether clinical descriptors of ontogeny (i.e., de novo or secondary) are prognostically significant when accounting for genetic risk by ELN 2022. In a large multicenter cohort of patients (n = 734), we found that abnormal ABCs are not independently prognostic after adjusting for genetic characteristics in dnAML patients. Furthermore, history of AHD and tAML do not confer increased risk of death compared to dnAML on multivariate analysis, suggesting the prognostic impact of ontogeny is accounted for by disease genetics as stratified by ELN 2022 risk and TP53 mutation status. These findings emphasize the importance that disease genetics should play in risk stratification and clinical trial eligibility in AML.

Subject terms: Acute myeloid leukaemia, Acute myeloid leukaemia, Risk factors, Cancer genomics

To the Editor:

Classification of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) by ontogeny distinguishes patients with known antecedent hematologic disease (AHD) or prior chemoradiation exposure (therapy-related, tAML) from those patients without these etiologic features (de novo, dnAML). Large population-based studies support an association between both AML post-AHD and tAML (collectively known as secondary AML, sAML) and worse prognosis compared to dnAML, especially in younger patients [1, 2]. Next generation sequencing (NGS) technologies have allowed for improved characterization of AML genetics; specific genetic alterations are now associated with ontogeny-related groups [3]. Additionally, tAML with favorable-risk genetics appears to have transcriptomic features and clinical outcomes similar to genetically favorable-risk dnAML [4, 5]. Similarly, although TP53-mutated AML often results from cytotoxic therapy exposure, TP53-mutated disease has dismal outcomes regardless of prior therapy history [6]. Altogether, these studies suggest disease genetics may drive the outcomes classically attributed to ontogeny.

While ontogeny provides a convenient means to readily risk stratify AML patients at diagnosis, it also has been frequently used to determine eligibility for clinical trials. However, patients with a new AML diagnosis may have not been formally diagnosed with AHD due to patient refusal to undergo bone marrow examination, lack of access to care, or prior non-diagnostic bone marrow samples. Alternatively, patients may be inferred to have sAML from AHD (“post-AHD sAML”) due to a history of antecedent blood count (ABC) abnormalities, though such abnormalities may be multifactorial and unrelated to a primary marrow disorder. Whether such patients with abnormal ABCs but without pathologically proven AHD should be considered equivalent to sAML is unclear. Furthermore, the poor prognosis of sAML may reflect the adverse-risk genetics that often accompanies a secondary etiology as opposed to the historical background itself. Importantly, dnAML cases carrying secondary-type mutations [3] (e.g., ASXL1, BCOR, EZH2, etc.) or cytogenetic aberrations have poor clinical outcomes [7]. Accordingly, the 2022 European LeukemiaNet (ELN) risk classification [8] incorporated secondary-type mutations in its adverse-risk group. Herein, we evaluated whether ABC abnormalities, documented AHD, or exposure to prior cytotoxic therapy were independently prognostic after accounting for ELN 2022 risk category and TP53 mutation at time of AML presentation.

Clinical, histopathologic, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic data were collected on 734 adults with newly diagnosed AML (as defined by the 5th edition of the WHO Classification of myeloid neoplasms [9]) from Johns Hopkins Hospital, Baltimore, MD (n = 388) and Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA (n = 346). Post-AHD sAML cases were defined by prior confirmed pathologic diagnosis of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) or myelodysplastic/myeloproliferative neoplasm (MDS/MPN; corresponding to AML-myelodysplasia-related [AML-MR] in the 5th edition WHO Classification [9]) or a myeloproliferative neoplasm (MPN; corresponding to MPN in blast phase [9]). Patients with dnAML were evaluated for abnormal ABCs at least 28 days and up to 2 years prior to the AML diagnosis. Univariate and multivariable Cox models were used to evaluate associations between OS and RFS and relevant covariates. Additional information on our methods can be found in our Supplementary Materials.

Of the 734 patients in the cohort, 488 (66%) had dnAML, 123 (17%) had post-AHD AML, and 123 (17%) had tAML (Supplementary Table 1). Of the dnAML patients, 88 had normal and 162 had abnormal ABCs documented; ABCs were not available in the remaining 238 patients. Patients with post-AHD sAML and tAML patients were, on average, older than patients with dnAML (median age 71 and 67 versus 63 years respectively, P < 0.001) and had a greater proportion with poor performance status (28% and 29% versus 18% respectively, P = 0.006). AHD was diagnosed a median of 461 days prior to post-AHD sAML (range 8–5 959 days). The majority of AHD cases were MDS (Supplementary Table 2). A greater proportion of patients with post-AHD sAML and tAML had adverse ELN risk compared to patients with dnAML (69% and 82% versus 53% respectively, P < 0.001) and a greater proportion were TP53-mutated (36% and 25% versus 12% respectively, P < 0.001). A smaller proportion of patients with post-AHD sAML and tAML received high/intermediate-intensity treatment versus dnAML (34% and 43% versus 66% respectively, P < 0.001).

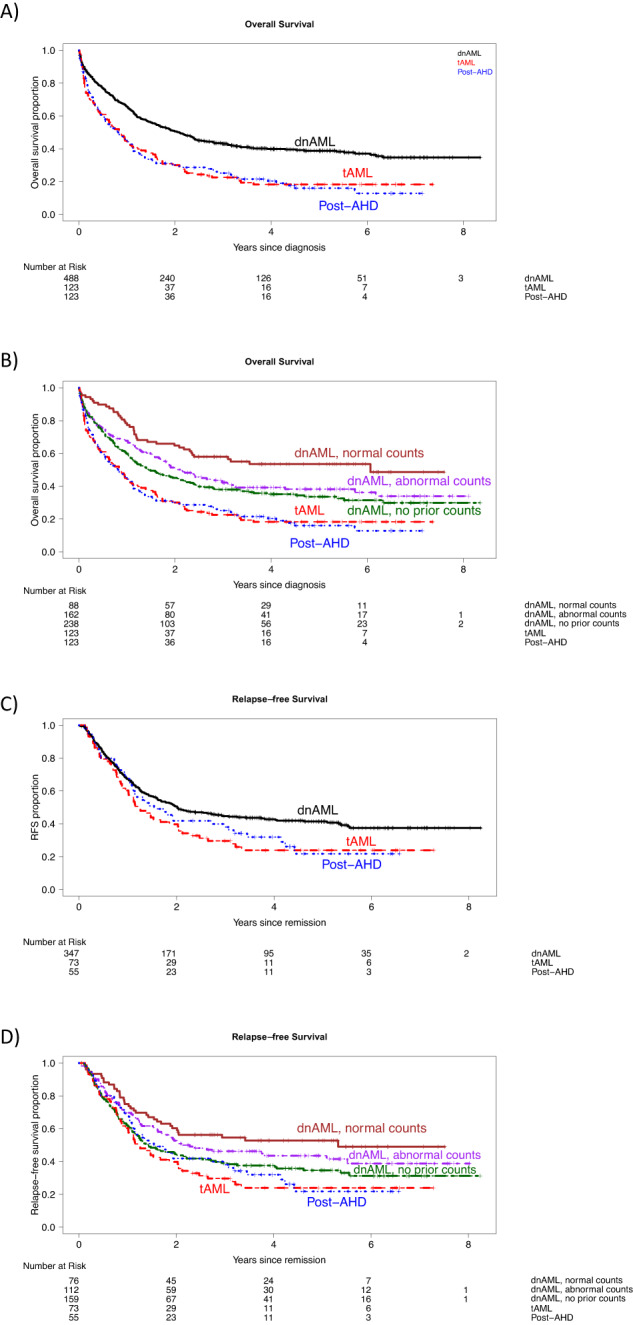

Patients with dnAML had significantly longer survival than those with either post-AHD sAML or tAML (Fig. 1A), and survival differed among patients with dnAML based on their history of ABC abnormalities (Fig. 1B). Relapse-free survival in these subgroups followed similar patterns (Fig. 1C, D). On multivariable analysis (Supplementary Table 3), however, there was no significant difference in hazard of death between those with abnormal versus normal ABCs (hazard ratio [HR] 1.22, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.84-1.77).

Fig. 1. Kaplan-Meier estimates of overall and relapse free survival stratified by ontogeny and antecedent blood count abnormalities.

A Overall survival stratified by ontogeny: de novo acute myeloid leukemia (dnAML), secondary AML post-antecedent hematologic disease (AHD), and therapy-related AML (tAML). B Overall survival stratified by ontogeny and antecedent blood count abnormalities in dnAML. C Relapse free survival stratified by ontogeny. D Relapse free survival stratified by ontogeny and antecedent blood count abnormalities in dnAML.

Given that abnormal ABCs were not independently prognostic in dnAML on multivariable analysis, we grouped all dnAML cases together on subsequent analyses regardless of ABCs. Among patients with ELN adverse-risk disease, a higher proportion of post-AHD sAML patients had secondary-type mutations compared to patients with dnAML or tAML (58% versus 40% and 24%, respectively, P < 0.001). Two hundred fifty-six of the 488 patients with dnAML (52%) received HCT; 42/123 (34%) and 44/123 (36%) received HCT for post-AHD sAML and tAML, respectively. In a multivariable model, patients with post-AHD sAML and tAML did not have a significantly increased hazard of death relative to those with dnAML (HR 1.12, 95% CI 0.88–1.42 and 1.21, 95% CI 0.95–1.53, respectively; see Table 1). ELN risk and TP53 mutation status remained independently significant in the multivariable model.

Table 1.

Cox regression models for overall survival. Baseline hazard was stratified by institution (Hopkins versus MGH).

| Univariate HR (95% CI) | Multivariable HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| AML Group (ref = dnAML) | ||

| Post-AHD sAML | 1.81 (1.44–2.27) | 1.12 (0.88–1.42) |

| tAML | 1.77 (1.41–2.23) | 1.21 (0.95–1.53) |

| Age at diagnosis (per 10 years) | 1.30 (1.21–1.39) | 1.11 (1.03–1.20) |

| Poor PS (ref = Good PS) | 3.10 (2.51–3.82) | 2.39 (1.91–2.98) |

| ELN22 Group (ref = ELN22 favorable) | ||

| ELN22 intermediate | 1.52 (1.07–2.17) | 1.90 (1.32–2.73) |

| ELN22 adverse | 3.05 (2.30–4.05) | 2.71 (2.00–3.68) |

| TP53 mutant (ref = TP53 wild-type) | 3.15 (2.55–3.89) | 1.74 (1.38–2.20) |

| Low-intensity chemotherapy (ref = high/intermediate-intensity chemotherapy) | 2.37 (1.98–2.83) | 1.23 (0.98–1.56) |

| Transplant (ref=no transplant) | 0.38 (0.31–0.47) | 0.45 (0.36–0.56) |

Transplant was analyzed as a time-dependent covariate.

Missing PS, missing TP53, and ELN unknown were analyzed as separate categories (to not exclude patients missing those data from the multivariable model; results not printed for brevity).

ref reference, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, sAML secondary acute myeloid leukemia, AHD antecedent hematologic disease, dnAML de novo AML, tAML therapy-related AML, PS performance status, ELN22 European LeukemiaNet 2022.

Our analysis had several key findings. First, we found that abnormal ABCs do not independently impact outcomes in dnAML patients, highlighting that secondary ontogeny cannot reliably be deduced from clinical history of abnormal ABCs in the absence of a formal AHD diagnosis. Antecedent thrombocytopenia was previously found to be independently prognostic in a smaller cohort (n = 140) of dnAML patients [10]; however, this study did not adjust for gene mutations as ours did. Notably, patients without recorded ABCs maintained independently worse prognosis on multivariable analysis (HR 1.94, 95% CI 1.36–2.76). We recognize that our approach to evaluating for ABC abnormalities is limited by the lack of clinical context that clinicians often use when evaluating such a history, but our objective methodology is reproducible and avoids bias inherent to determining which count abnormalities may suggest an undiagnosed AHD.

Next, we found that the prognostic impact of disease-related genetic risk, as measured by ELN 2022 and TP53 mutation status, supersedes the risk conferred by AML ontogeny. This finding emphasizes the role that disease genetics should play in determining patient prognosis and driving therapeutic decision making. While the turnaround time of cytogenetics and NGS assays has posed challenges in using genetics to influence up-front treatment choice, the BEAT AML Master trial demonstrated that a precision medicine approach is theoretically possible in the subset of newly diagnosed AML patients who are able to wait a 7-day period prior to starting therapy [11]. Moreover, the approval of molecularly-targeted therapies in the front-line for AML (such as midostaurin and ivosidenib for FLT3-ITD and IDH1-mutated disease, respectively) illustrates the utility of genetics in the pre-treatment setting and may help drive more rapid turnaround of genetic testing to inform treatment choice [12]. Ontogeny will always remain valuable to leukemia specialists by providing important context to AML presentation, hence its inclusion as a disease qualifier in classification guidelines [8, 9]. However, our findings suggest that AML clinical trials should enroll patients from genetically-defined groups as opposed to more genetically heterogenous groups defined by ontogeny, in order to most definitively determine who is most likely to benefit from an intervention.

One recently published single-center study found ontogeny was independently prognostic even after adjusting for AML genetic risk; the hazard of death for tAML or post-AHD sAML was over two-fold higher than that for dnAML on multivariate analysis [13]. Possible reasons for our differing results include the smaller single institution patient cohort and lack of a surrogate for baseline comorbidities in the McCarter study; ours attempted to capture this via use of baseline performance status. Additionally, interactions between different genomic abnormalities, such as co-mutation patterns or multi-hit TP53 mutations, may account for some of the disease risk attributed to ontogeny in the McCarter paper; for example, one recent study found that two or more (rather than at least one) secondary-type mutation better defined a high-risk AML cohort [14]. Together our reports suggest that disease genetics ultimately have a greater impact on survival outcomes than ontogeny.

Finally, we found that TP53 mutation status appears to confer additional independent disease risk even when accounting for ELN adverse status and ontogeny. Given our findings and the poor outcomes known to be associated with this disease group [6] especially in the presence of complex karyotype [15], we suggest that AML patients with TP53-mutated disease be considered to represent a “very adverse” group separate from the ELN 2022 adverse-risk group.

In summary, ABCs did not provide independent prognostic information for dnAML patients after accounting for ELN 2022 genetic risk and TP53 mutation status. Additionally, neither post-AHD sAML nor tAML maintained prognostic associations with shorter OS in the multivariable model. These findings suggest that comprehensive genetic categorization, as opposed to clinical descriptors of ontogeny, should play a primary role in clinical risk stratification and trial eligibility in newly diagnosed AML.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Our work is dedicated to Dr. Elihu H. Estey who, prior to his death, played a pivotal role in the genesis and design of this study. Dr. Hochman’s work was funded by Hematology T32 Training Grant NHLBI# T32HL007525.

Author contributions

MJH, MO, RPH, EHE, and JEK contributed to the design of the study. MJH, RPH, AA, and AB extracted data for the analyses. MO performed the statistical analyses. MJH, MO, RPH, and JEK interpreted the study results. MJH wrote the manuscript. All other authors reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript and approved the final submission.

Data availability

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests; data will be shared per each institution’s policies and procedures.

Code availability

The computer code used in R to generate the results in this paper is available for access by emailing Dr. Megan Othus at mothus@fredhutch.org.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Elihu H. Estey, Judith E. Karp.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41375-023-01985-y.

References

- 1.Granfeldt Østgård LS, Medeiros BC, Sengeløv H, Nørgaard M, Andersen MK, Dufva IH, et al. Epidemiology and clinical significance of secondary and therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia: a national population-based cohort study. JCO. 2015;33:3641–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.60.0890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hulegårdh E, Nilsson C, Lazarevic V, Garelius H, Antunovic P, Rangert Derolf Å, et al. Characterization and prognostic features of secondary acute myeloid leukemia in a population-based setting: a report from the Swedish Acute Leukemia Registry. Am J Hematol. 2015;90:208–14. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindsley RC, Mar BG, Mazzola E, Grauman PV, Shareef S, Allen SL, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia ontogeny is defined by distinct somatic mutations. Blood. 2015;125:1367–76. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-11-610543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Othman J, Meggendorfer M, Tiacci E, Thiede C, Schlenk RF, Dillon R, et al. Overlapping features of therapy-related and de novoNPM1-mutated AML. Blood. 2022;141:1846–57. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Kayser S, Krzykalla J, Elliott MA, Norsworthy K, Gonzales P, Hills RK, et al. Characteristics and outcome of patients with therapy-related acute promyelocytic leukemia front-line treated with or without arsenic trioxide. Leukemia. 2017;31:2347–54. doi: 10.1038/leu.2017.92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg OK, Siddon A, Madanat YF, Gagan J, Arber DA, Dal Cin P, et al. TP53 mutation defines a unique subgroup within complex karyotype de novo and therapy-related MDS/AML. Blood Adv. 2022;6:2847–53. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021006239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai XC-H, Sun K-J, Lo M-Y, Tien F-M, Kuo Y-Y, Tseng M-H, et al. Poor prognostic implications of myelodysplasia-related mutations in both older and younger patients with de novo AML. Blood Cancer J. 2023;13:1–11. doi: 10.1038/s41408-022-00774-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, Craddock C, DiNardo CD, Dombret H, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults: 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood. 2022;140:1345–77. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022016867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Khoury JD, Solary E, Abla O, Akkari Y, Alaggio R, Apperley JF, et al. The 5th edition of the world health organization classification of haematolymphoid tumours: myeloid and histiocytic/dendritic neoplasms. Leukemia. 2022;36:1703–19. doi: 10.1038/s41375-022-01613-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huck A, Pozdnyakova O, Brunner A, Higgins JM, Fathi AT, Hasserjian RP. Prior cytopenia predicts worse clinical outcome in acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Res. 2015;39:1034–40. doi: 10.1016/j.leukres.2015.06.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burd A, Levine RL, Ruppert AS, Mims AS, Borate U, Stein EM, et al. Precision medicine treatment in older AML: results of beat AML master trial. Blood. 2019;134:175. doi: 10.1182/blood-2019-130201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Duncavage EJ, Schroeder MC, O’Laughlin M, Wilson R, MacMillan S, Bohannon A, et al. Genome sequencing as an alternative to cytogenetic analysis in myeloid cancers. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:924–35. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McCarter JGW PhD, Nemirovsky D, Famulare CA, Farnoud N, Mohanty AS, Stone-Molloy ZS, et al. Interaction between myelodysplasia-related gene mutations and ontogeny in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood Adv. 2023: bloodadvances.2023009675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Tazi Y, Arango-Ossa JE, Zhou Y, Bernard E, Thomas I, Gilkes A, et al. Unified classification and risk-stratification in acute myeloid leukemia. Nat Commun. 2022;13:4622. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32103-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rausch C, Rothenberg-Thurley M, Dufour A, Schneider S, Gittinger H, Sauerland C, et al. Validation and refinement of the 2022 European LeukemiaNet genetic risk stratification of acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2023;37:1234–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Please contact the corresponding author for data requests; data will be shared per each institution’s policies and procedures.

The computer code used in R to generate the results in this paper is available for access by emailing Dr. Megan Othus at mothus@fredhutch.org.