Abstract

CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has promising therapeutic potential for genetic diseases and cancers, but safety could be a concern. Here we use whole genomic analysis by 10x linked-read sequencing and optical genome mapping to interrogate the genome integrity after editing and in comparison to four parental cell lines. In addition to the previously reported large structural variants at on-target sites, we identify heretofore unexpected large chromosomal deletions (91.2 and 136 Kb) at atypical non-homologous off-target sites without sequence similarity to the sgRNA in two edited lines. The observed large structural variants induced by CRISPR-Cas9 editing in dividing cells may result in pathogenic consequences and thus limit the usefulness of the CRISPR-Cas9 editing system for disease modeling and gene therapy. In this work, our whole genomic analysis may provide a valuable strategy to ensure genome integrity after genomic editing to minimize the risk of unintended effects in research and clinical applications.

Subject terms: Genomics, Gene therapy, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing

The safety of CRISPR-Cas9 editing is a concern. Here the authors use whole genomic analysis by 10x linked-read sequencing and optical genome mapping to interrogate the genome integrity after editing: they see large structural variants at on-target sites and unexpected large chromosomal deletions.

Introduction

The induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) technology is a powerful platform for pathogenesis studies, drug screening, tissue engineering, and cell replacement therapy. Human iPSCs will enable the development of autologous, patient-specific stem cell therapies, resulting in long-term engraftment without needing immunosuppressive treatments for patients. Several transplantations of autologous iPSC-derived cells have been reported1–4; none of the patients in these studies has suffered severe adverse events, suggesting promising feasibility for personalized regenerative medicine. However, using iPSCs for allogeneic transplantation will require establishing large numbers of iPSC lines to cover the MHC diversities for their off-the-shelf applications in replacement cell therapy.

An alternative strategy is to develop a hypoimmunogenic single iPSC from a common donor and bank it as an off-the-shelf product for allogeneic applications5,6. Recently, several studies showed that human iPSCs lost immunogenicity when MHC class I and II genes were inactivated, and CD47 was overexpressed by CRISPR-Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/CRISPR-associated protein 9) genome editing7–10.

The CRISPR-Cas9 system is a powerful technology for precise gene editing of the genome11–14. It consists of Cas9 endonuclease and single-stranded guide RNA (sgRNA). The sgRNA recruits the Cas9 endonuclease to cleave both DNA strands at the target site in a sequence-specific manner to generate a double-stranded break (DSB). DSB stimulates cellular DNA repair mechanisms via error-prone non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) or homology-directed repair (HDR), which results in site-specific genetic alterations15. Therefore, DSB activates the NHEJ repair pathway leading to insertions or deletions at the target site, causing frameshift mutation in the coding sequence and gene knockout. Another use of CRISPR-Cas9 is to perform HDR to create point mutations and gene knock-in. Thus, this technology holds promise for correcting hereditary diseases caused by point mutations.

An important application of CRISPR-Cas9 is establishing genetically modified animal and cellular models of human diseases via gene knockout/ knock-in and site-specific mutagenesis16,17. This technology platform has progressed from being a research tool to one that promises clinical applications. While the utility of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing for gene therapy in humans has been recognized and investigated18,19, several studies demonstrated that Cas9-mediated genomic editing in human and mouse embryos led to on-target chromosome structure alterations and chromosome loss20–23. Other studies reported large DNA deletions and genomic rearrangements at the on-target sites in mouse ESCs, mouse hematopoietic progenitors, human differentiated retinal pigment epithelial cells, primary cells, and cancer cell lines24,25. Moreover, CRISPR-Cas9 edited fertilized zebrafish eggs showed structural variants (ranged from 4.8 Kb-deletions to 1.4 Kb-insertions) at on-target and predicted off-target sites with sequence similarity to the sgRNA and 26% of their offspring carry off-target mutations26. In addition, a recent study employing ultra-deep clinical next-generation sequencing in the coding region of 523 cancer-relevant genes demonstrated the safety of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells27. However, chromosomal aberrations outside the coding region of these genes were not surveyed. Since genome aberrations caused by CRISPR-Cas9 editing could lead to unforeseen pathogenic consequences, pre-testing for sequence variations is essential. In the literature, there are numerous methods used to analyze genomic alteration. Karyotyping is the oldest genetic method for chromosome alterations larger than 5 Mb; it can detect aneuploidy as well as transpositions, deletions, duplications, and inversions. Chromosomal microarray (CMA) has been used to determine chromosomal imbalances such as amplifications and deletions such as copy number variants (CNV). CMA provides submicroscopic resolution allowing us to visualize small regions that karyotyping cannot detect. Depending upon the particular array and how many DNA probes are used, it is possible to detect as small as 10 Kb. In contrast to microarray methods, next-generation sequencing (NGS), also known as high throughput sequencing, directly determines the nucleic acid sequence of a given DNA.

In this study, we investigate the whole genome integrity of thirteen CRISPR-Cas9 edited human pluripotent stem cell lines to uncover possible structural alterations, particularly those that may not be detected by short-read sequencing. We perform linked-read sequencing by 10x Genomics and optical genome mapping28–30 by Bionano Genomics Saphyr System to examine the entire genome structure and sequence of the edited genomes. Here, we identify one on-target large structural variant (SV) (>50 Kb) and two large SVs at atypical non-homologous off-target sites, which were previously unrecognized as consequences of CRISPR-Cas9 mediated genome editing. Importantly, we illustrate a strategy for whole genomic analysis using linked-read sequencing and optical mapping to detect and validate CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing outcomes. This study may provide an approach for reducing the risk of unexpected adverse effects in research and clinical applications.

Results

Whole-genome sequencing of CRISPR-Cas9-edited human iPSC by linked-read sequencing

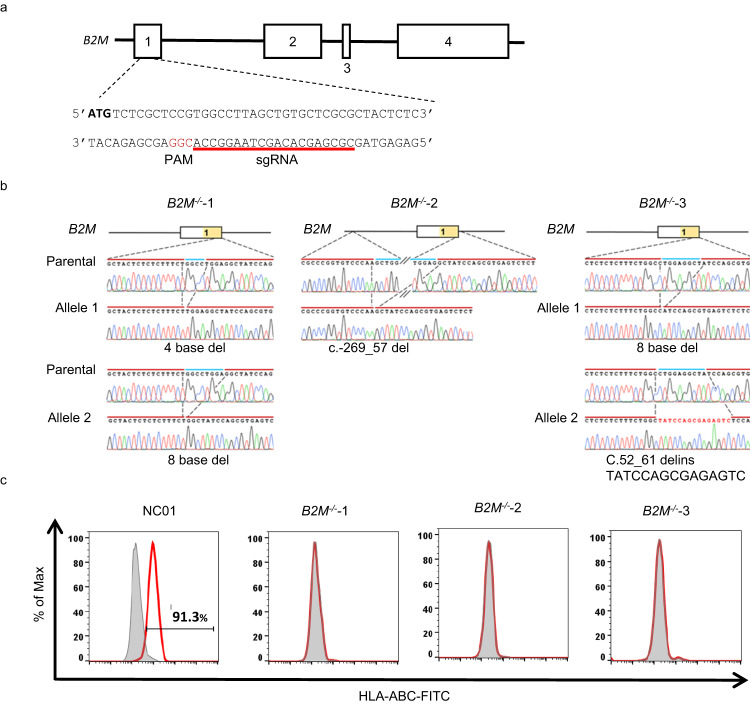

To evaluate the genome integrity after CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene editing, we first generated B2M knockout iPSCs. The B2M gene on chromosome 15 of iPSC NC01 was edited by transient expression of Cas9 nuclease and a sgRNA targeting the first exon of the B2M gene (Fig. 1a). Three single-cell clones (B2M-/-−1, −2, and −3) were randomly selected and isolated. The frameshift mutations were detected in exon 1 of the B2M gene and verified by Sanger sequencing (Fig. 1b). None of these three B2M-/- clones express HLA-class I molecules (HLA-ABC) on the cell surface, demonstrating the successful knockout of the B2M gene (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. The gene editing for B2M and workflow analysis.

a Schematic presentation of human B2M gene and sequence of B2M exon 1 showing PAM site and the genomic target for sgRNA. Boxes represent exons of the B2M gene. b The sequences and chromatogram of the frameshift mutations in B2M-/- clones. The B2M-/-−1, −2, and −3 single-cell clones were isolated after CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing. The DNA mutations of each allele were demonstrated by sequencing analysis. c Knockout of B2M in iPSCs abrogates surface expression of HLA class I (HLA-ABC) detected via flow cytometry. The red color represents the expression of HLA-ABC, and the gray color represents the isotype control. n = 4 replicates. The gating strategies are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we performed whole genome sequencing to examine the entire genome integrity of these single-cell clones of the CRISPR-Cas9-edited iPSCs. The short-read sequencing, which currently dominates genomic analysis, may identify some structural variants, but it cannot delineate repetitive regions nor resolve the human genome into haplotypes. In addition, the diploid nature of the human genome makes it even more difficult to detect large SVs in the heterozygous state. To overcome these issues, we performed linked-read sequencing to inspect the integrity of CRISPR-Cas9-edited genomes.

High molecular weight DNAs consisting of long DNA fragments, with 90–95% >20 Kb in length, were prepared and subjected to 10x Genomics Linked-Reads sequencing. Reads generated have an average mean depth of 52.8X, out of which an average of 95.4% of the reads could be mapped to the reference genome GRCh38 (Genome Reference Consortium Human Build 38), resulting in more than 99.1% of SNPs being phased (Supplementary Table 1).

Knockout of the B2M gene by CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing induces unexpected chromosomal large structural variants

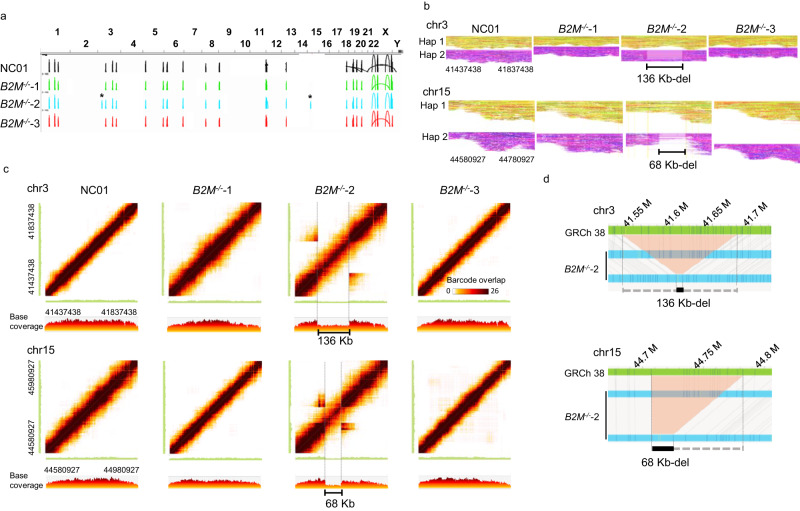

The linked-read sequencing data was analyzed using the Long Ranger software (v2.2.2) pipeline with default options. The linked-reads were mapped to the human reference genome, GRCh38, using the Lariat. We used Long Ranger for structural variant detection and Loupe (v2.1.1) for visualization. As compared to the reference genome, there are many large SV calls found in the parental (NC01) and three B2M knockouts derived from NC01 (Fig. 2a). However, when compared to the NC01, there are two tentative large SV calls (marked as *) which were detected in B2M-/-−2, but not in the NC01 nor the other two knockouts (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2. Large SVs arise during the CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout of B2M.

a The large SV calls are constructed from linked-reads of the parental (NC01) and three single-cell clones of B2M knockouts. Peaks represent the predicted large SV calls compared to GRCh38. The asterisks * indicated large SVs on chromosomes 3 and 15 in B2M-/-−2, which were not detected in the NC01 and B2M-/-−2 and 3. b Matrix view of the overlapping barcodes analyzed with Loupe software (10x Genomics) showed heterozygous deletions in B2M-/-−2 on chr3:41437438–41837438 and chr15:44580927–44980927, respectively. The matrix view was plotted with the dark brown color representing the shared barcodes between two genomic segments marked on the X- and Y-axis. The X and Y axes correspond to the same genome region, so the barcode overlap matrix is symmetric. The diagonal shows the number of barcodes in each position along the displayed region. The colored band around the diagonal reflects long molecules that span several kilobases, thus generating barcode overlaps across their span. The color intensity drops suggest a relative drop in the number of molecules in that region. Therefore, the drop in coverage and the off-diagonal barcode overlap suggest a heterozygous deletion. The linear view represents the base coverage along the X-axis segment. The 136 and 68 Kb indicate heterozygous deletions. c The phased reads graphs showed a 136 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chr3:41437438–41837438 and a 68 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chr15:44580927–44780927 in B2M-/-−2. Reads are partitioned into distinct haplotypes 1 (Hap1) and 2 (Hap2). d The optical genome mapping revealed a 136 Kb-heterozygous deletion on the chr3:41.5 Mb locus and a 68 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chr15:44.7 Mb locus in the B2M-/-−2. The gray lines indicate the alignment between the reference (GRCh38; green) and the assembled maps (B2M-/-−2; blue). The light red area indicates the deletions.

To confirm these two large SVs found in B2M-/-−2, we examined the barcode overlapping of these two large SVs, plotted by Loupe software (10x Genomics). As shown in Fig. 2b, the large SV1 is a 136 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chromosome 3 (chr3:41537429-41673419). The large SV2 is a 68 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chromosome 15 (chr15:44710621-44778608). In Fig. 2c, the linked-reads assigned to each haplotype (Hap 1 or 2) of chromosome 3 and 15, respectively, are grouped and color-coded: a heterozygous deletion of approximately 136 Kb on Hap 2 of the chromosome 3 (large SV1) and a 68 Kb-heterozygous deletion on Hap 2 of chromosome 15 (large SV2) was found.

Optical genome mapping is another technology that provides structural information about a single long DNA molecule. It is powerful for examining structural variants due to the much longer length of optical genome mapping analysis (up to 2.5 Mb) compared to the sequencing reads28,31. Optical genome mapping was performed on the NC01 and three B2M knockouts to confirm the finding of large SVs identified by the linked-reads. As shown in Fig. 2d, optical genome mapping revealed a 136 Kb-heterozygous deletion on the chr3:41.5 Mb locus and a 68 Kb-heterozygous deletion on the chr15:44.7 Mb locus in the B2M-/-−2, consistent with the two large SVs detected by linked-reads. Likewise, optical genome mapping did not reveal any large SVs in the NC01, B2M-/-−1, and B2M-/-−3, consistent with the linked-read sequencing. These results thus strongly confirmed that the CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knockout induces large chromosomal SVs.

Validation of large SVs using polymerase chain reaction and identification of an on-target and an unexpected off-target large SV

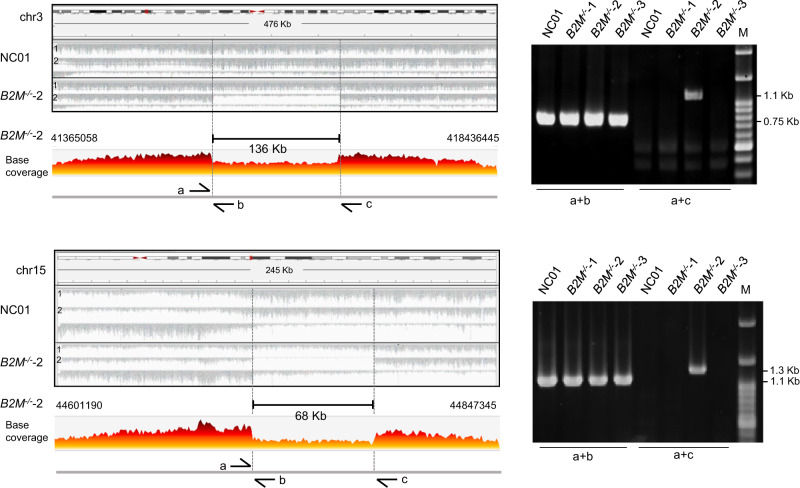

To further confirm the existence of two large SVs in B2M-/-−2 identified by linked-reads and optical genome mapping, we performed further validation using polymerase chain reaction (PCR). The pair of primers, shown as a and c in chr3 and chr15, separately, in Fig. 3, were designed to cover enormously big genomic DNA fragments (136- and 68-Kb in size) that exceed the current PCR technology to generate any PCR amplicons. On the other hand, if large DNA deletion did occur in these regions, PCR amplicons of much shorter DNA segments would be generated. Genomic DNA prepared from the B2M-/-−2 clone was amplified using these two pairs of primers, and two specific PCR amplicons of 1.1-Kb and 1.3-Kb in size were found (Fig. 3, a+c). In addition, the PCR products were verified by Sanger sequencing, and the break junctions were confirmed. These results were consistent with the notion that this clone had two large structural variants, SV1 and SV2, on chromosomes 3 and 15.

Fig. 3. PCR validation for the heterozygous large SVs in B2M-/-−2.

The phased BAM format was performed with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV_2.7.2)48–50 sorted with 10x Genomics linked-read haplotype tag (HP; haplotype of the molecule that generated the read). The region of large SVs in the parental (NC01) and B2M-/-−2 can be phased into two strands with an HP tag (left panel). Agarose gel electrophoresis images of the PCR products amplified from NC01 genomic DNA and B2M knockouts (right panel). Primers a and b are designed to target the breakpoint junctions and primers a and b for the intact genomic region. The base coverage of large SVs in B2M-/-−2 was visualized by Loupe. M is the size marker. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 12. n = 3 replicates for PCR analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In contrast, PCR amplification of DNA from NC01, B2M-/-−1, or B2M-/-−3 using the same pair of primers did not generate any specific PCR products (Fig. 3, a+c). To rule out the possibility that this lack of PCR amplicons in NC01, B2M-/-−1, and 3 were attributed to inadequate quality of genomic DNA preparation, we designed a second pair of primers, a and b, shown in Fig. 3, which targeted short genomic regions. With these pairs of primers, PCR amplicons with approximately 0.75 Kb for the large SV1 region on chr3 and 1.1 Kb for the large SV2 region on chr15 were detected in all DNA samples obtained from NC01 and three knockouts (Fig. 3, a+b). Therefore, the generation of PCR amplicons from the intact genomic region of one allele and the deletion region of the other allele from B2M-/-−2 indicates that the deletions are heterozygous, also consistent with the findings by linked-reads and optical genome mapping.

Additionally, the large SV2 on chr15 (chr15:44710621-44778608) is an on-target DNA deletion, which may have derived from the DNA repair of double-strand break caused by sgRNA/Cas9 targeting where the sgRNA is located at chr15:44711556-44711575. The on-target large DNA deletion has been reported for gene knockout mediated by CRISPR-Cas9 genomic editing24.

To assess the possibility of predicted off-target effect on large SV1, we used the Cas-OFFinder32 algorithm to predict the potential off-target sites close to the chromosome region of large SV1 with mismatch numbers equal to or less than six and DNA bulge size equal to or less than two. Surprisingly, no predicted off-target site close to large SV1 was found, as shown in Supplementary Table 2. In addition, we used CRISTA33, an off-target search tool that implements many features, such as GC contents, RNA secondary structure, DNA methylation, epigenetic factors, and Elevation34, that takes both sequence and chromatin accessibility features to predict the potential target sites. However, as shown in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4, these predicted potential target sites are too far from the large SV to account for Cas9-mediated DNA cleavage. Besides, our whole genome analysis did not reveal any sequence/structural abnormalities in these predicted off-target sites. Accordingly, the large SV1 may be induced by an atypical non-homologous off-target event without sequence similarity to the sgRNA. Such an unexpected, atypical non-homologous off-target large SV is, to the best of our knowledge, the first discovery in the CRISPR-Cas9 edited genomes, which implies the emergence of unforeseen pathological consequences during CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene knockout.

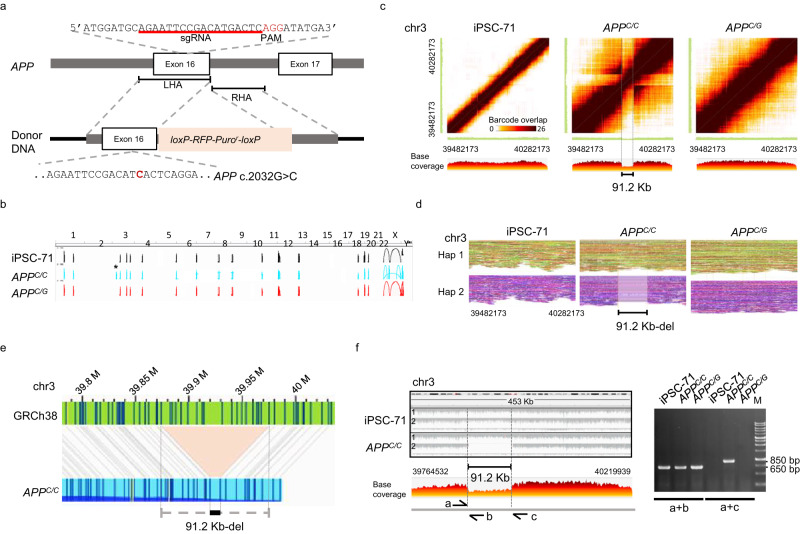

The gene knock-in for APP c.2033G>C point mutation by CRISPR-Cas9 editing also induces an atypical non-homologous off-target large SV

To investigate whether the observed atypical non-homologous off-target large SV may be incurred by CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene knock-in, we performed CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to generate point mutation for APP c.2033G>C in human iPSC-71 as illustrated in Fig. 4a. A homozygous gene-mutated-(APPC/C) and a heterozygous mutated (APPC/G) single-cell clones were isolated. The base substitution was verified using Sanger sequencing. In addition, whole-genome linked-read sequencing (Supplementary Table 5) and optical genome mapping were used to examine the genome integrity after CRISPR-Cas9 editing. Compared to the reference genome, there are several large SV calls predicted in parental (iPSC-71) and APP knock-in genomes (Fig. 4b). Moreover, there is a tentative large SV call (marked as *), which was presented only in APPC/C, but not in the iPSC-71 nor APPC/G (Fig. 4b). Based on the linked-reads (Fig. 4c, d) and optical genome mapping (Fig. 4e), this large SV was found to consist of a 91.2 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chromosome 3. The breakpoint junction of this 91.2 Kb-heterozygous deletion was confirmed by PCR which showed the generation of 1.3 kb PCR product in the APPC/C (Fig. 4f) but not in the iPSC-71 nor APPC/G. Besides, the sgRNA/Cas9 targeting locus is on chr21:25897598-25897615, whereas the large SV locus is on chr3:39882164−39973392 without any off-target site as predicted by Cas-OFFinder, CRISTA, and Elevation (Supplementary Tables 6–8). Thus, these results suggest that the 91.2 Kb-heterozygous deletion observed in the APPC/C is another unexpected, atypical non-homologous off-target large SV induced by CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene knock-in. Furthermore, we performed CIRCLE-seq35,36 to evaluate the specificity of sgRNA used in B2M knockout and APP knock-in (Supplementary Fig. 1). It was observed that there were efficiently targeted DNA cleavage sites (i.e. high CIRCLE-seq read counts) of the on-target B2M in chr15 (denoted by an asterisk, Supplementary Fig. 1a) and APP in chr21 (denoted by an asterisk, Supplementary Fig. 1b); but no reads detected on the chr3, where the two large SVs were detected in our studies. Therefore, these results further support our conclusion that the large SVs are independent of the homologous targeting by sgRNA.

Fig. 4. Large SV was found after CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene knock-in.

a The strategy for the base substitution of exon 16 of APP gene in human iPSC-71 by CRISPR-Cas9 mediated gene knock-in. The schematic presentation and the sequence of APP exon 16 loci with PAM, the targeting site for the sgRNA, and the donor DNA used for homology-directed repair (HDR) are shown. The loxP-RFP-Puror-loxP cassette was flanked by two homology arms. LHA, left homology arm (633 bp); RHA, right homology arm (582 bp). Boxes represent exons. b Large SV calls were constructed from linked-reads of the genome from iPSC-71, APPC/C, and APPC/G. The asterisk * indicates a large SV found in the APPC/C but not in the parental (iPSC-71) nor APPC/G. c Heat map of the overlapping barcodes in chr3:39482173–40282173 showing a heterozygous deletion in APPC/C. The matrix view was plotted by the Loupe, where the dark brown color represents the shared barcodes between the two genomic segments on the X- and Y-axis. The linear view represents the base coverage along the X-axis segment. d The phased reads graph indicates a 91.2 Kb-heterozygous deletion on chr3 in the APPC/C genome. Reads were partitioned into distinct haplotypes: haplotype1 (Hap1) and haplotype 2 (Hap2). e The optical genome mapping reveals a 91.2 Kb-heterozygous deletion (black bar) in chr3 of the APPC/C. The gray lines indicate the alignment between the reference (GRCh38; green) and assembled map (APPC/C; blue). The light red area shows the deletion. (f) PCR confirmation of the heterozygous deletion. PCR verification with primers a and b and using iPSC-71, APPC/C, and APPC/G genomic DNA as the template. The primer pair, a and b, were designed to amplify breakpoints of the deletion, which produce a unique amplicon in the mutant strand harboring the large SV; and the primer pair, a and b, were for the wild-type strand. The region of the large SV in the iPSC-71 and APPC/C was phased into two strands with an HP tag (left panel) and base coverage of APPC/C visualized by Loupe. M is the size marker. Primers are listed in Supplementary Table 12. n = 3 replicates for PCR analysis. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In addition, we performed optical genome mapping to study the occurrence of SVs in single-cell clones isolated from the PiggyBac transposon-mediated knock-in in the two parental iPSC lines, which were found to have large SVs in the Cas9-mediated gene editing: ETV2i2 knock-in in NC01 (the parental cell line of B2Mko) and NGN2 knock-in in iPSC-71 (the parental cell of APPC/C knock-in). The average N50 of those molecules was 246 Kb (range: 225-275 Kb), the average mapping ratio mapped to reference genome from molecules was 81.5% (range: 78.7-83.5%), and the average effective coverage was 84.8X (range: 57.1−111.48X). Several LSVs were detected in parental (NC01) and ETV2i2 knock-in genomes compared to the reference genome (GRCh38). However, none of these large SVs was found only in the ETV2i2 gene knock-in but not in the parental genomes (NC01; Supplementary Fig. 2a). Similarly, we could not find any large SVs which are present only in the NGN2 knock-in genomes but not in the parental iPSC-71 (Supplementary Fig. 2b) either. These results indicate that no unexpected large SVs occurred in the genomes of PiggyBac transposon-mediated gene knock-in clones derived from these two iPSCs (NC01 and iPSC-71). Therefore, these findings suggest that the atypical non-homologous off-target large SVs detected in the B2M-/-−2 and APPC/C clones may not have been caused by the cloning, prolonged expansion, and proliferation of these two iPSC lines and that the unexpected large SVs detected were not simply artifacts of the cell lines used in this study.

Moreover, we also investigated genome changes in B3GALT5 knockout37 in human embryonic stem cell H9, LRRK2 (G2019S) knock-in38 in iPSC ND40019*C, and DSG2 (F531C) gene knock-in in iPSC-71 (Supplementary Table 9). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, no large SV was revealed in these three edited genomes. In this study, two of the five edited cases of thirteen human pluripotent stem cell lines contained atypical non-homologous off-target large SVs incurred during CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing.

Discussion

Since genomic editing has clinical therapeutic implications for genetic diseases, it is crucial to understand the potential genome changes associated with CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. This study combined the 10x linked-read sequencing and optical genome mapping to identify the large chromosomal SVs in CRISPR-Cas9 edited genomes. Through these two approaches, we uncovered a large SV at the on-target site, an atypical non-homologous off-target large SV in a B2M-/- knockout clone, and another atypical non-homologous off-target large SV in APPc/c knock-in clone. However, no large SV was found in B3GALT5 knockout, LRRK2 (G2019S) knock-in, and DSG2 (F531C) gene knock-in genomes. Two of the 13 edited genomes we examined carried a large SV at an unpredicted atypical non-homologous off-target site; one of these two genomes had an additional large SV at the on-target site, which is expected. Altogether, in our CRISPR-Cas9 edited genomes, ~15% acquired unexpected, atypical non-homologous off-target large SVs.

Intriguingly, the two large SVs identified in these independently derived CRISPR-edited iPSC clones are located in chromosome 3p, which is distinctly apart from the chromosome 15 (B2M) and 21 (APP), where the target genes reside. While Chromosome 3 spans about 198 Mb, the two large SV identified are ~1.65 Mb apart. Whether the relative proximity of these large SV on two unrelated CRISPR-edited iPSC clones is purely co-incidental or related to some unknown mechanisms that predispose this region of chromosome 3 to genetic alterations awaits further studies. Furthermore, we browsed the chromosomal fragile sites on HumCFS, a human chromosomal fragile sites database39. There are four known chromosomal fragile sites on the chr3: FRA3A (chr3:23900001-26400000), FRA3B (chr3:58600001-63700000), FRA3C (chr3:182700001-187900000), and FRA3D (chr3:148900001-160700000). However, the large SV in B2M-/-−2 is at chr3:41535938-41680677, and the large SV in APPC/C is at chr3:39882164−39973392, neither of which are fragile sites. Therefore, the large SVs reported in this study are not in the known chromosomal fragile sites. The large SV detected in the B2M-/-−2 clone contains the ULK4 gene; ULK4 belongs to the family of unc-51-like serine/threonine kinases, which participates in a conserved pathway involving both endocytosis and axon growth40–42. Sequence variations in this gene have been associated with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder43. The large SV detected in the APPC/C contains the MYRIP (Myosin VIIA and Rab interacting protein) gene, which is predicted to exhibit binding activity for actin and myosin, to be involved in positive regulation of insulin secretion and functions as a component of the exocytosis machinery44,45. Thus, neither ULK4 nor MYRIP is known to be directly involved in cell proliferation, cell death, and cell signaling, which might be predicted to give the proliferative advantage to the clones.

The linked-read sequencing (up to 150 Kb) provides a clear advantage over short reads (typically 150–300 bp) alone, allowing for the construction of long-range haplotypes and promising better long-range contiguity and resolution of repetitive regions. Alternatively, one of our authors, Dr. Pui-Yan Kwok, works on another alternative by combining high-accuracy short reads and PacBio-CLR (the continuous long read) to resolve structural variations and provide haplotype phasing. Other options include other long read sequencings such as PacBio and Nanopore sequencings, but these two long read technologies have their own problems, such as sequence accuracy and high cost. In contrast to DNA sequencing read, optical genome mapping produces single long molecule (~225 Kb) maps which could cover heterozygous genome regions with different haplotypes that cannot be easily spanned by sequencing read. On the other hand, optical genome mapping detects SVs across the whole genome but does not provide sequence-level information or precise SV breakpoints. Therefore, combining linked-read sequencing and optical genome mapping would be a better option for genome integrity analysis.

A significant issue of CRISPR-Cas9 technology is the unintended mutations for cell replacement therapy at the genome locus other than the targeted site. Such off-target mutations can have profound consequences as they might disrupt the function or regulation of the non-targeted genes. In addition, large SVs recognized in this study, occurring at either on-target or atypical non-homologous off-target sites, could pose further concerns. Such DNA lesions may lead to pathological or carcinogenic changes in stem cells, which have a long replicative lifespan and may become non-functional or neoplastic with time. Therefore, the atypical non-homologous off-target large SVs reported here illustrate a need to thoroughly examine the genome integrity when CRISPR-Cas9 editing is conducted. Besides, the plasmid DNA delivery was used in this study to account for CRISPR-Cas9 editing, and we wondered if ribonucleoprotein (RNP) delivery could see whether the atypical non-homologous off-target large SVs would happen. A recent paper performed the genome-editing simultaneously of HLA-A and -B genes located on chr6 with the RNP delivery system46. In the original report, chromosome karyotyping revealed that one of the 15 selected iPSC clones had translocation of chr2 distal to 2p16−22, to the terminal end of the long arm of chr15. Therefore, we employed the Cas-OFFinder and CRISTA algorithms to examine the potential off-target sites close to the chromosome region. As it turned out, we did not detect potential off-target sites close to this translocation region (Supplementary Tables 10 and 11). These results thus suggest that this large chromosome translocation detected by karyotyping is also an unexpected, atypical non-homologous off-target large SV induced by CRISPR-Cas9 using RNP delivery. However, the original paper did not mention that this off-target large SV site, without sequence similarity to the sgRNA, occurred during RNP genome editing. In addition, the finding of the translocation of this big chromosomal fragment was detected by chromosome karyotyping, which has the limitation for detecting rearrangements with less than 5 Mb of DNA, although the use of multicolor fluorescence in situ hybridization can improve the resolution to ~100 Kb–1 Mb in size. Improving the ability to detect such un-intended large SVs to ensure genome integrity will maximize the safety and chance for clinical implementation of site-specific genome editing therapies.

In conclusion, gene editing of the same iPSC line with CRISPR-Cas9 does not always induce large SV at atypical non-homologous off-target sites in all gene-edited clones. For instance, the large SV was only observed in one of three B2Mko clones. Thus, we do not advocate stopping the use of this powerful genome editing tool based on our findings. Instead, we propose a strategy for detecting and validating CRISPR-Cas9 genome-editing outcomes using linked-reads and optical genome mapping. Our strategy of whole genomic analysis using linked-read sequencing and optical genome mapping may provide a valuable strategy for confirming the genome integrity of the CRISPR-Cas9 edited clones before clonal expansion and long-term ex vivo culture for research and clinical applications.

Methods

Cell culture and CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing

Human iPSCs were maintained with Matrigel (human embryonic stem cell–qualified matrix, Corning, No.354277) in Essential 8™ Medium (E8, GibcoTM, No. A1517001). The medium was changed every 24 hours, and cells were passaged after 5 min incubation with 0.5 mM EDTA (InvitrogenTM, No.15575020) at room temperature. For replating iPSCs, the E8 medium was supplemented with a 2 μM ROCK inhibitor, thiazovivin (Selleckchem, No. S1459).

For gene knockout, 2 × 106 single-cell suspensions of human iPSCs were electroporated with 1 μg of the Cas9 and gRNA containing plasmid DNA using the Neon Transfection System (Invitrogen) following the settings of 1500 V, 20 ms pulse width, and a single pulse. For gene knock-in, 2 × 106 human iPSCs were electroporated with 1 μg of the Cas9 and gRNA-containing plasmid DNA and 1 μg of the donor DNA using the settings of 1500 V, 20 ms pulse width, and a single pulse. One day later, the medium was changed into E8 medium, supplemented with 1 μg/ml puromycin for 48 hours. The puromycin-resistant iPSCs were plated at a low density in 6-well plates and cultured for days until the surviving colonies derived from a single cell were manually picked. After clonal expansion, the genomic DNA of these candidate clones was isolated and used for PCR and sequencing. The cell lines used in this study are H9 (NSC-H9, WiCell), NC01 (generated in our lab), iPSC-71 (material transfer from Joseph C. Wu, Stanford Cardiovascular Institute), and ND40019*C38. The sgRNA sequences are listed in Supplementary Table 12.

Flow cytometry analysis

For surface staining, 5 × 105 cells were incubated with antibodies in total 100 μl at 4 °C for 30 min and analyzed with SA3800 Spectral Analyzer (SONY). The antibodies were HLA-ABC monoclonal antibody (W6/32, FITC, eBioscience, 11-9983-42, 1:200) and mouse IgG2a kappa Isotype Control (eBM2a, FITC, eBioscience™, 11-4724-42, 1:200).

High molecular weight DNA extraction and 10x Genomics sequencing and assembly pipeline

High-molecular-weight genomic DNA (HMW gDNA) extraction, sample indexing, and partition barcoded libraries were done according to 10x Genomics (Pleasanton, CA, USA), Chromium Genome User Guide. The HMW gDNA was extracted from each sample with the Bionano PrepTM kit (Bionano Genomics). Then HMW gDNAs were subjected to 10x Genomics Linked-Reads sequencing on the NovaSeq 6000 Sequencing System (Illumina) to 60x read depth.

Long Ranger (v2.2.2) was used for analyzing the 10x sequencing data with the “WGS” pipeline and the default settings. The sequence files were processed and aligned with GRCh38 via Long Ranger BASIC and ALIGN Pipelines (10x Genomics) for linked-read alignment, variant calling, phasing, and structural variant calling. The Lariat aligner mapped the linked-reads to the reference genome (GRCh38/hg38). After variant calling, a phasing method optimized for a 10x barcode was used to phase the identified SNPs. The output of the Long Ranger pipeline was analyzed with the Loupe (v2.1.1) to visualize large SVs, inter-chromosomal translocations, gene fusions, and inversions or deletions. Loupe viewer also displayed the analyzed genome with two haplotypes.

Bionano whole-genome mapping

The HMW gDNAs were prepared for Bionano Genomics optical genome mapping library following the Bionano Prep Direct Label and Stain (DLS) protocol. Briefly, cells were embedded into low-melting-point agarose gel plugs (BioRad #170-3592, Hercules, CA, USA). Then, plugs were incubated with lysis buffer and proteinase K overnight at 50 °C, solubilized with agarose (Thermo Fisher Scientific) at 50 °C for 40 min, and the purified DNA was subjected to drop-dialysis for one h. Next, the HMW gDNA was subjected to an enzymatic labeling approach for direct fluorescent labeling by the Direct Label Enzyme (DLE-1). After sequence-specific labeling with DLE-1, the DLE libraries were applied to optical genome mapping on the Bionano Genomics Saphyr System to 60x coverage. Next, single-molecule maps were assembled de novo into genome maps using the assembly pipeline developed by the Bionoano Solve pipeline (v3.3, v3.6.1 and v3.7.01) with default setting47. All structural variations (SVs), including deletions, insertions, inversions, and translocations, were annotated to GRCh38 by the Variant Annotation Pipeline of Bionoano Solve (v3.3, v3.6.1, and v3.7.01). The SVs of interested regions were shown after being compared to the GRCh38.

sgRNA off-target analysis

The Cas-OFFinder program (http://www.rgenome.net/cas-offinder/, with mismatch numbers equal to or less than six and DNA bulge size equal to or less than two), CRISTA (https://crista.tau.ac.il/), and Elevation (https://crispr.ml/) were used to predict the off-target sites for sgRNAs used in this study.

CIRCLE-seq library preparation

CIRCLE-seq experiments were performed on genomic DNA from the same cells in which they were used for genome editing (either NC01 or iPSC-71 cells). CIRCLE-seq library construction followed the protocol published in Nat Protoc. 201835. Briefly, purified genomic DNA was sheared to an average length of 300 bp and circularized at low DNA concentration. In vitro cleavage reactions were performed with Cas9 nuclease buffer (NEB, B6003S), 90 nM SpCas9 protein (NEB, M0386M), 90 nM synthesized gRNA, and 250 ng of circularized DNA. Digested DNA products were A-tailed, ligated with a hairpin adaptor, treated with USER enzyme (NEB, M5505L), and amplified by PCR using KAPA HiFi polymerase (Roche). The libraries were sequenced with 150 bp paired-end reads on the MiSeq Sequencing System (Illumina).

Statistics and reproducibility

No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. No data were excluded from the analyses. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants to J. Yu from Chang Gung Medical Foundation in Taiwan OMRPG3C0048 and the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan NMRPD1M0092. In addition, we thank Professor Akitsu Hotta from CiRA, Kyoto University, for the discussion and advice on RNP delivery. Finally, we thank the National Center for Genome Medicine in Taiwan and Feng-Jen Hsieh for technical support.

Author contributions

H.H.T., A.L.Y., and J.Y. developed the study concept design and writing of the manuscript. H.H.T., H.J.K., M.W.K., C.H.L., C.M.C., Y.Y.C., and H.H. Chen performed the experimental studies. H.H.T. and H.J.K. carried out the analysis. P.Y.K., A.L.Y., and J.Y. supervised the work.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alex Hastie, Francois Moreau-Gaudry, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

The 10x Genomics sequencing data of genomes generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under accession code PRJNA943092. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-023-40901-x.

References

- 1.Madrid M, Sumen C, Aivio S, Saklayen N. Autologous induced pluripotent stem cell-based cell therapies: promise, progress, and challenges. Curr. Protoc. 2021;1:e88. doi: 10.1002/cpz1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Takagi S, et al. Evaluation of transplanted autologous induced pluripotent stem cell-derived retinal pigment epithelium in exudative age-related macular degeneration. Ophthalmol. Retina. 2019;3:850–859. doi: 10.1016/j.oret.2019.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Souied E, Pulido J, Staurenghi G. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;377:792. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1706274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mandai M, et al. Autologous induced stem-cell-derived retinal cells for macular degeneration. N. Engl. J. Med. 2017;376:1038–1046. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1608368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blau HM, Daley GQ. Stem cells in the treatment of disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019;380:1748–1760. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1716145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yamanaka S. Pluripotent stem cell-based celltherapy-promise and challenges. Cell Stem Cell. 2020;27:523–531. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2020.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Han X, et al. Generation of hypoimmunogenic human pluripotent stem cells. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2019;116:10441–10446. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1902566116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang B, et al. Generation of hypoimmunogenic T cells from genetically engineered allogeneic human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021;5:429–440. doi: 10.1038/s41551-021-00730-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ye Q, et al. Generation of universal and hypoimmunogenic human pluripotent stem cells. Cell Prolif. 2020;53:e12946. doi: 10.1111/cpr.12946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deuse T, et al. Hypoimmunogenic derivatives of induced pluripotent stem cells evade immune rejection in fully immunocompetent allogeneic recipients. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019;37:252–258. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0016-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cho SW, Kim S, Kim JM, Kim JS. Targeted genome engineering in human cells with the Cas9 RNA-guided endonuclease. Nat. Biotechnol. 2013;31:230–232. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jinek M, et al. RNA-programmed genome editing in human cells. Elife. 2013;2:e00471. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mali P, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826. doi: 10.1126/science.1232033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ran FA, et al. Genome engineering using the CRISPR-Cas9 system. Nat. Protoc. 2013;8:2281–2308. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ceccaldi R, Rondinelli B, D’Andrea AD. Repair pathway choices and consequences at the double-strand break. Trends Cell Biol. 2016;26:52–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zarei A, Razban V, Hosseini SE, Tabei SMB. Creating cell and animal models of human disease by genome editing using CRISPR/Cas9. J. Gene Med. 2019;21:e3082. doi: 10.1002/jgm.3082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodriguez-Rodriguez DR, Ramirez-Solis R, Garza-Elizondo MA, Garza-Rodriguez ML, Barrera-Saldana HA. Genome editing: a perspective on the application of CRISPR/Cas9 to study human diseases (review) Int. J. Mol. Med. 2019;43:1559–1574. doi: 10.3892/ijmm.2019.4112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang H, et al. Application of the CRISPR/Cas9-based gene editing technique in basic research, diagnosis, and therapy of cancer. Mol. Cancer. 2021;20:126. doi: 10.1186/s12943-021-01431-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cornu TI, Mussolino C, Cathomen T. Refining strategies to translate genome editing to the clinic. Nat. Med. 2017;23:415–423. doi: 10.1038/nm.4313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Leibowitz ML, et al. Chromothripsis as an on-target consequence of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat. Genet. 2021;53:895–905. doi: 10.1038/s41588-021-00838-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuccaro MV, et al. Allele-Specific Chromosome Removal after Cas9 Cleavage in Human Embryos. Cell. 2020;183:1650–1664 e1615. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alanis-Lobato G, et al. Frequent loss of heterozygosity in CRISPR-Cas9-edited early human embryos. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2021;118:e2004832117. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2004832117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Papathanasiou S, et al. Whole chromosome loss and genomic instability in mouse embryos after CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. Nat. Commun. 2021;12:5855. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-26097-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kosicki M, Tomberg K, Bradley A. Repair of double-strand breaks induced by CRISPR-Cas9 leads to large deletions and complex rearrangements. Nat. Biotechnol. 2018;36:765–771. doi: 10.1038/nbt.4192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cullot G, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing induces megabase-scale chromosomal truncations. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1136. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09006-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoijer I, et al. CRISPR-Cas9 induces large structural variants at on-target and off-target sites in vivo that segregate across generations. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:627. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-28244-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cromer MK, et al. Ultra-deep sequencing validates safety of CRISPR/Cas9 genome editing in human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells. Nat. Commun. 2022;13:4724. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-32233-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shieh JT, et al. Application of full-genome analysis to diagnose rare monogenic disorders. NPJ Genom. Med. 2021;6:77. doi: 10.1038/s41525-021-00241-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam ET, et al. Genome mapping on nanochannel arrays for structural variation analysis and sequence assembly. Nat. Biotechnol. 2012;30:771–776. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dimalanta ET, et al. A microfluidic system for large DNA molecule arrays. Anal. Chem. 2004;76:5293–5301. doi: 10.1021/ac0496401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chaisson MJP, et al. Multi-platform discovery of haplotype-resolved structural variation in human genomes. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1784. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-08148-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bae S, Park J, Kim JS. Cas-OFFinder: a fast and versatile algorithm that searches for potential off-target sites of Cas9 RNA-guided endonucleases. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:1473–1475. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abadi S, Yan WX, Amar D, Mayrose I. A machine learning approach for predicting CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage efficiencies and patterns underlying its mechanism of action. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2017;13:e1005807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Listgarten J, et al. Prediction of off-target activities for the end-to-end design of CRISPR guide RNAs. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2018;2:38–47. doi: 10.1038/s41551-017-0178-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lazzarotto CR, et al. Defining CRISPR-Cas9 genome-wide nuclease activities with CIRCLE-seq. Nat. Protoc. 2018;13:2615–2642. doi: 10.1038/s41596-018-0055-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsai SQ, et al. CIRCLE-seq: a highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat Methods. 2017;14:607–614. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.4278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lin RJ, et al. B3GALT5 knockout alters glycosphingolipid profile and facilitates transition to human naive pluripotency. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2020;117:27435–27444. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2003155117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chang KH, et al. In vitro genome editing rescues parkinsonism phenotypes in induced pluripotent stem cells-derived dopaminergic neurons carrying LRRK2 p.G2019S mutation. Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2021;12:508. doi: 10.1186/s13287-021-02585-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kumar R, et al. HumCFS: a database of fragile sites in human chromosomes. BMC Genomics. 2019;19:985. doi: 10.1186/s12864-018-5330-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pelkmans L, et al. Genome-wide analysis of human kinases in clathrin- and caveolae/raft-mediated endocytosis. Nature. 2005;436:78–86. doi: 10.1038/nature03571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tomoda T, Kim JH, Zhan C, Hatten ME. Role of Unc51.1 and its binding partners in CNS axon outgrowth. Genes Dev. 2004;18:541–558. doi: 10.1101/gad.1151204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ogura K, et al. Caenorhabditis elegans unc-51 gene required for axonal elongation encodes a novel serine/threonine kinase. Genes Dev. 1994;8:2389–2400. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.20.2389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lang B, et al. Recurrent deletions of ULK4 in schizophrenia: a gene crucial for neuritogenesis and neuronal motility. J. Cell Sci. 2014;127:630–640. doi: 10.1242/jcs.137604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Huet S, et al. Myrip couples the capture of secretory granules by the actin-rich cell cortex and their attachment to the plasma membrane. J. Neurosci. 2012;32:2564–2577. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2724-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Waselle L, et al. Involvement of the Rab27 binding protein Slac2c/MyRIP in insulin exocytosis. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2003;14:4103–4113. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E03-01-0022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu H, et al. Targeted disruption of HLA genes via CRISPR-Cas9 generates iPSCs wi. Cell Stem Cell. 2019;24:566–578.e567. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2019.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao H, et al. Rapid detection of structural variation in a human genome using nanochannel-based genome mapping technology. Gigascience. 2014;3:34. doi: 10.1186/2047-217X-3-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Wenger AM, Zehir A, Mesirov JP. Variant review with the integrative genomics viewer. Cancer Res. 2017;77:e31–e34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Robinson JT, et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat. Biotechnol. 2011;29:24–26. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thorvaldsdottir H, Robinson JT, Mesirov JP. Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV): high-performance genomics data visualization and exploration. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:178–192. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The 10x Genomics sequencing data of genomes generated in this study have been deposited in the NCBI SRA database under accession code PRJNA943092. Source data are provided with this paper.