Abstract

Members of the Vibrionaceae family are predominantly fast-growing and halophilic microorganisms that have captured the attention of researchers owing to their potential applications in rapid biotechnology. Among them, Vibrio alginolyticus FA2 is a particularly noteworthy halophilic bacterium that exhibits superior growth capability. It has the potential to serve as a biotechnological platform for sustainable and eco-friendly open fermentation with seawater. To evaluate this hypothesis, we integrated the N-acetylglucosamine (GlcNAc) pathway into V. alginolyticus FA2. Seven nag genes were knocked out to obstruct the utilization of GlcNAc, and then 16 exogenous gna1s co-expressing with EcglmS were introduced to strengthen the flux of GlcNAc pathway, respectively. To further enhance GlcNAc production, we fine-tuned promoter strength of the two genes and inactivated two genes alsS and alsD to prevent the production of acetoin. Furthermore, unsterile open fermentation was carried out using simulated seawater and a chemically defined medium, resulting in the production of 9.2 g/L GlcNAc in 14 h. This is the first report for de-novo synthesizing GlcNAc with a Vibrio strain, facilitated by an unsterile open fermentation process employing seawater as a substitute for fresh water. This development establishes a basis for production of diverse valuable chemicals using Vibrio strains and provides insights into biomanufacture.

Keywords: Vibrio, Open fermentation, Metabolic engineering, N-acetylglucosamine

1. Introduction

Members of the Vibrionaceae family, such as Vibrio Parahaemolyticus, Vibrio alginolyticus, and Vibrio natriegens, are characterized by their rapid growth [[1], [2], [3]]. V. natriegens is a fast-growing marine bacterium, with a generation time of less than 10 min and significantly shorter than that of Escherichia coli [2]. As genetic manipulation tools and protein expression systems have evolved, V. natriegens has become an increasingly attractive option and is now recognized as a next-generation chassis for synthetic biology and biotechnology [[4], [5], [6]]. V. natriegens ATCC 14048 shows superiority in fast growth, fast substrate uptake rates, and fast protein expression, and is regarded as the host for rapid biotechnology [4,5]. At present, this strain has been employed as the host for alanine or other significant compounds [5]. Although rapid growth is undeniably advantageous, the cost of media remains a significant concern for large-scale production [7]. The provision of nutrients, such as yeast extract and tryptone, is imperative for the prevalent industrial microbial hosts including Corynebacterium glutamicum, Bacillus subtilis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae during fermentation processes [[8], [9], [10]]. Although these additional supplements improve strains’ growth and production performance, they simultaneously increase production costs. Consequently, cheaper alternatives such as a chemically defined medium are often preferred for large-scale production due to their superior cost-effectiveness [11]. V. alginolyticus FA2 is a marine bacterium, that boasts an even higher growth rate than that of V. natriegens ATCC 14048 in the chemically defined, cost-effective media. In addition, it exhibits the ability to utilize a wide range of substrates, and its genetic operating tools have been established [12]. Therefore, V. alginolyticus FA2 exhibits substantial potential as a viable biotechnological candidate for mitigating the limitations presented by high economic expenses associated with contemporary production processes.

In addition, typical microbial fermentations often encounter issues with contamination, necessitating intricate sterilization procedures and high energy inputs, increasing costs and complicating the processes [7,13]. Extremeophilic microorganisms, such as thermophilic and halophilic bacteria, are expected to adopt non-sterile open fermentation methods to streamline fermentation processes and reduce production costs, due to their unique ability to thrive under extremely specific conditions [7]. As V. alginolyticus FA2 is a halophilic bacterium, the extremely saline conditions significantly mitigate the risk of bacterial infection, making unsterile fermentation a possibly viable option to reduce the cost and simplify the process of industrial bio-process. Furthermore, seawater represents an immense global reservoir of resources, yet the high cost associated with desalination processes required for human consumption and industrial applications remains a significant challenge [14]. The direct employment of seawater as an alternative to sodium chloride aqueous solution for unsterile open fermentation with halophilic bacteria will not only optimize the utilization of seawater resources but also reduce costs and address the challenge of freshwater scarcity [15]. Therefore, V. alginolyticus FA2 exhibits promising potential as a microbial platform to develop unsterile open biomanufacturing processes that rely on seawater and chemically defined medium, which is expected to minimize costs and promote sustainable and eco-friendly biomanufacturing practices in the future.

GlcNAc is a valuable compound with diverse applications in cosmetics, dietary supplements, biomedicine, and pharmaceutical industries, as well as its derivatives [16]. It is also contributed to the treatment for COVID-19 [17]. GlcNAc can be obtained by directly hydrolyzing from chitin with strong acid, which causes environmental pollution and allergic reactions in some individuals [18]. In addition, it can be produced from chitin using chitinolytic enzymes [19,20]. Enzyme hydrolysis is effective and environmentally friendly, but an unstable raw material supply could limit the production. Compared with other methods, microbial fermentation for GlcNAc synthesis has unique advantages such as cheap carbon sources, higher yield and purity, and greener processes. Currently, the GlcNAc synthesis strains include Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [[21], [22], [23]]. In 2005, Deng et al. constructed recombinant Escherichia coli with 110.0 g/L GlcNAc after fermentation for 72 h [24]. Nevertheless, there are some problems for GlcNAc production with Escherichia coli, such as phage contamination [25]. Systematic metabolic engineering has been successfully applied in GlcNAc production with Bacillus subtilis. The recombinant strain produced 33.7 g/L GlcNAc in the flasks after 60 h [26], but spores exist in the late stage of Bacillus species and harm the fermentation [27]. Although Saccharomyces cerevisiae is widely applied in biotechnology, the GlcNAc titer with this strain is still very low [23]. Moreover, additional nutrients are always necessary for these hosts, thereby augmenting the overall production costs [[8], [9], [10]]. Given the increasing market demand, it is imperative to develop an economical and efficient production technology for GlcNAc. To evaluate the feasibility of exploiting V. alginolyticus FA2 for application in non-sterile open biomanufacturing processes, we endeavored to integrate the GlcNAc pathway into its metabolic repertoire.

In this study, we realized the de-novo synthesis of GlcNAc with V. alginolyticus FA2 through an unsterile open fermentation with simulated seawater and a chemically defined medium. We removed seven nag genes to block GlcNAc re-utilization. Then, exogenous glucosamine-6-phosphate N-acetyltransferases (GNA1) were introduced, and promoter strength of genes was optimized to strengthen the flux of the GlcNAc synthesis pathway. Further, we inactivated the main complete pathway of acetoin through the removal of alsS and alsD and conducted the unsterile open fermentation. This study represents the first successful attempt at de novo synthesizing GlcNAc using a fast-growing Vibrio strain as the workhorse, employing an unsterile process with the simulated seawater and a chemically defined medium. This accomplishment lays the foundation for future endeavors in utilizing V. alginolyticus FA2 as a platform to generate other valuable chemicals, employing techniques that are both environmentally friendly and sustainable.

2. Materials & methods

2.1. Bacterial strains, plasmids, and chemicals

The strains and plasmids used in this study are shown in Table S1. Escherichia coli DH5α was used as the host for plasmid construction. The V. alginolyticus FA2 was used as the metabolic engineering host to produce GlcNAc, which was previously screened by our lab [12]. The plasmid pACYCDuet-1 was used for gene over-expression. All the chemicals except those especially mentioned were purchased from Sangon Biotech (shanghai, China). DNA gel purification kit and plasmid extraction kit were purchased from Tiangen (Beijing, China). Restriction enzymes and T4 DNA ligase were purchased from New England Biolabs.

2.2. Cultivation conditions

All the recombinant Escherichia coli strains were cultivated with LB broth (10 g/L tryptone, 5 g/L yeast extract, and 10 g/L NaCl) at 37 °C, 200 rpm. All the recombinant V. alginolyticus FA2 strains were cultivated with LB3 broth (lysogeny broth (LB) with an additional 2% NaCl) at 37 °C, 200 rpm. The concentration of chloramphenicol was 25 μg/mL if necessary.

The recombinant V. alginolyticus FA2 strains were stored at −80 °C with 15% (vol/vol) glycerol stock. These strains were prepared with LB3 broth overnight at 37 °C, 200 rpm. Then, the fermentation (250 mL flask containing 50 mL media) was performed using the chemically defined MKO medium at 37 °C, 200 rpm [12]. The active culture seed was inoculated into the above medium at a dilution of 1:100, and was shaken at 37 °C, 200 rpm. When the OD600 was at 0.6−0.8, the Isopropyl β-d-Thiogalactoside (IPTG) was added at a final concentration of 0.5 mM.

2.3. Promoter replacement of pACYCDuet-1

The original expression vector pACYCDuet-1 was previously stored in our group. To remove the two T7 promoters and introduce other promoters (Pals, Ptrc, Ptac, Plac, PJ23110, PJ23100, and P16) (http://parts.igem.org/) [[28], [29], [30]], the region of two replaced promoters (Pals, Ptrc, Ptac, Plac, PJ23110, PJ23100, and P16) and polyclonal sites were synthesized with ClaI and XhoI at the fragments' two ends, respectively. Then, the fragments were inserted in pACYCDuet-1 (digested with ClaI and XhoI), respectively. The resulting recombinant plasmids with newly introduced promoters were used for the following experiments. The sequences were listed in the Supporting Information.

2.4. Construction co-expression plasmids for glmS and gna1s

Escherichia coli glmS was amplified using E. coli K12 genome DNA with the primer glmS-F (NcoI)/glmS-R (BamHI), and was inserted in modified pACYCDuet-1 [31]. Exogenous gna1s were synthesized by GENEWIZ (suzhou, China) after codon optimization, and were inserted in modified pACYCDuet-1 with KpnI and XhoI, respectively. All the primers used are listed in Table S2.

2.5. Gene editing

The gene editing was performed using pKR6K with homologous recombination [32]. The upstream and downstream homologous arms of nagB were amplified from the genomic DNA of V. alginolyticus FA2 with the primers nagB-UF (EcoRI)/nagB-UR and nagB-DF/nagB-DR (BamHI), respectively. Then, the two fragments were fused by overlap extend PCR with the primer nagB-UF (EcoRI)/nagB-DR (BamHI), and were inserted in pKR6K. The resulting plasmids were transformed in E. coli S17-1 (donor strain). The V. alginolyticus FA2 was as the receptor strain.

The donor and receptor strains were pre-cultured in LB and LB3 broth, respectively. Then, they were inoculated in the fresh LB or LB3 broth. When the OD600 was at 0.6–0.8, the donor strain and the receptor strain were centrifugated at 5000 rpm, 10 min. The supernatant was thrown, and the cells were resuspended with 0.85% NaCl. The steps were repeated twice. Then, the donor strain and the receptor strain were mixed by 5:1, and the mixture was plated on LB broth with 1.5–2% agar. After overnight cultivation at 30 °C, the cells were washed with 0.85% NaCl twice. Then, cells were plated on MKO broth with 1.5–2% agar and 25 μg/mL chloramphenicol, and were cultivated at 30 °C. Then, a single colony was picked and was cultured with LB3 broth and 25 μg/mL chloramphenicol. Then, single-crossover colonies were verified by PCR. Correct colonies were cultured in LB3 broth without resistance to make the second crossover. Then, the double-crossover colonies were verified by PCR with the primer nagB-UF (EcoRI)/nagB-DR (BamHI), and the correct colonies of gene knockout was used for the following experiments.

Disruption of genes nagC2, nagACE, nagK, nagK2, and alsS and integration of gene Ltgna1 at the loci of alsD were all performed using the procedure described above.

2.6. Unsterile open fermentation of GlcNAc in a 5-L bioreactor

The fermentation broth contains the following components: 40 g/L glucose, 28 g/L sea salt, and 7 g/L (NH4)2SO4. Trace element (1000 × ): 3.2 g/L CaCl2, 3.8 g/L ZnCl2, 30 g/L FeCl3·6H2O, 11.14 g/L MnCl2·4H2O, 0.96 g/L CuCl2·2H2O, 2.6 g/L CoCl2·6H2O, 0.35 g/L H3BO3, 0.024 g/L Na2MoO4·2H2O. Except for deeding with glucose, metal salts are also needed. The feeding metal salts consisted of 28 g sea salt, 7 g (NH4)2SO4, 10 g K2HPO4, and 10 g KH2PO4 at every 4 h. The seed cultures were inoculated with a dilution of 10:100, and 25 μg/mL chloramphenicol was added. The pH was automatically kept at 7.0 via the addition of NH3·H2O, and the stirrer speed was at 600 rpm. The temperature was at 37 °C, and aeration was kept at 1.5 vvm.

2.7. Analytical methods

The fermentation samples were centrifugated at 12,000 rpm, 5 min. Then, the concentrations of GlcNAc and acetoin were analyzed with the high-performance liquid chromatography 1260, equipped with the HPX-87H column (Bio-Rad) and RID detector. The mobile phase was 5 mM H2SO4 with a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min. The detector temperature was at 30 °C, and the column oven was at 65 °C.

3. Results

3.1. Establishing GlcNAc synthetic pathway by EcglmS-Scgna1 co-expression

The GlcNAc pathway of V. alginolyticus FA2 was analyzed and shown in Fig. 1. It has been observed that the gna1 is absent, which is critical for GlcNAc synthesis [33]. So, exogenous gna1 needs to be introduced. Except for gna1, another gene glmS (encoding glutamine-d-fructose-6-phosphate aminotransferase) is also necessary for GlcNAc production. In previous investigations, concurrent expression of glmS and gna1 is deemed essential for the biosynthesis of GlcNAc production.

Fig. 1.

Metabolic engineering scheme for the production of GlcNAc in recombinant V. alginolyticus FA2. Arrows indicate metabolic pathways, with yellow representing the pathways that have been reinforced and black representing the natural pathways present. The symbol ⊗ represents gene knock-out. G-6-P: glucose-6-phosphate; F-6-P: fructose-6-phosphate; GlcN-6P: glucosamine-6-phosphate; GlcNAc-6P: N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate; EcglmS: the gene encoding glucosamine-6-phosphate synthase from E. coli; Ltgna1: the gene encoding glucosamine-6-phosphate N-acetyltransferase from Lachancea thermotolerans gna1.

Herein, the pACYCDuet-1 was chosen as the expression vector to co-express glmS and gna1. However, due to the absence of T7 RNA polymerase in V. alginolyticus FA2, the T7 promoter could not be utilized. Thus, a constitutive expression promoter Pals was chosen to replace the two T7 promoters resulting in pACYCDuet-Pals-Pals [28] (Fig. 2A). Then, EcglmS was amplified from Escherichia coli K12, and was inserted in pACYCDuet-Pals-Pals with NcoI and BamHI, resulting pACYCDuet-Pals-EcglmS-Pals. The reported Saccharomyces cerevisiae gna1 was synthesized after codon optimization and was inserted in pACYCDuet-Pals-EcglmS-Pals with KpnI and XhoI, resulting in pA-EG-SG (pACYCDuet-Pals-EcglmS-Pals-Scgna1) [33]. The efficacy of pA-EG-SG was evaluated in wild-type V. alginolyticus FA2 in the flasks, but no GlcNAc was produced.

Fig. 2.

The establishment of GlcNAc synthetic pathway through EcglmS-Scgna1 co-expression and nag genes knock out. (A) Replacing pACYCDuet-1 T7 promoters with Pals promoters to co-express glmS and gna1. (B) The locus of nag operon genes in V. alginolyticus FA2 genomes. (C) The genotype of resulting strains by removing nag operon genes. (D) The Cell growth (OD600) of FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG) (filled circle), FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG) (filled square), and FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) (filled triangle). (E) The GlcNAc titer with FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG) (filled circle), FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG) (filled square), and FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) (filled triangle).

3.2. Increasing GlcNAc production by removing nag genes

Nag genes are responsible for GlcNAc utilization in many genera [34]. The extracellular GlcNAc is transported into the cytoplasm by nagE (the GlcNAc-specific enzyme of the phosphotransferase system) [[34], [35]]. Once inside the cell, intracellular GlcNAc can be phosphorylated by nagK (N-acetylglucosamine kinase), resulting in GlcNAc-6P [36]. Subsequently, GlcNAc-6P is deacetylated by nagA (N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase), forming GlcN-6P [37]. Then, the Fru-6P forms from GlcN-6P by nagB (glucosamine-6-phosphate deaminase) and participates in cell central metabolism [34]. Additionally, the nagC was a transcriptional regulatory protein of the nag operon [38].

The genome sequence of V. alginolyticus FA2 was analyzed, and 7 nag genes were found (nagA, nagB, nagC, nagC2, nagE, nagK, and nagK2). These genes are observed to be distributed among the two chromosomes, with nagA, nagB, nagC, nagC2, and nagE at chromosome I, while nagB and nagK2 at chromosome II (Fig. 2B). Compared with other strains, the copy of nagK was more. This could potentially be attributed to natural advantages possessed by marine Vibrio strains in chitin utilization marine Vibrio strains have natural advantages in chitin utilization, whose major component is GlcNAc [39]. Notably, NagK2 has a significantly shorter amino acid sequence consisting of only 205 amino acids, which is 98 amino acids and 97 amino acids shorter than those of ecNagK and FA2 nagK, respectively [36]. Moreover, the amino acid sequence of NagK2 bears no resemblance to those of ecNagK and FA2 NagK. The presence of these seven nag operon genes may indicate an active GlcNAc catabolism in FA2, wherein GlcNAc is utilized immediately without accumulation. So, they block the formation of GlcNAc in FA2 (pA-EG-SG) and their removal is necessary.

The above 7 genes were all knocked out, and the resulting strains were shown in Fig. 2C. Firstly, the nagB (chr II 321242–322042) was knocked out, resulting in FA2-1. Then, nagC2 (chr I 1785969–1787186) was then removed resulting in FA2-2. The nagC (chr I 521284–522498), nagA (chr I 522501–523637), and nagE (chr I 524126–525619) were located closely in chromosome I, and were simultaneously knocked out, resulting in FA2-5. GlcNAc was first determined in FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG), and it was observed to be only 0.3 g/L in the flasks (Fig. 2E). The nagK (chr I 1244939–1245847) was further knocked out, resulting in FA2-6. GlcNAc produced by FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG) was 1.2 g/L in the flasks after 24 h, which represents a 300.0% increase compared to that of FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG). This suggests that the elimination of nagK effectively impedes GlcNAc phosphorylation. To further investigate the impact of nagK, another copy of the gene named nagK2 (chr II 890950–891567) was also knocked out, resulting in the creation of strain FA2-7. The GlcNAc production of FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) was assessed in flasks and found to reach 1.4 g/L after 24 h, which represents a 367.0% increase compared to FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG). We also conducted a comparison of the cell growth rates of FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG), FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG), and FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) (Fig. 2D). During the first 8 h, FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG) grew slightly faster than FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG) and FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG). During 8–12 h, FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG) and FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) exhibited faster growth than that of FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG). After 12 h, FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) displayed the most rapid growth, with a final OD600 of 6.3, while FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG) had an OD600 of only 4.6 and FA2-6 (pA-EG-SG) had an OD600 of 5.7. Therefore, the knockout of nag operon genes was proven to be effective for GlcNAc synthesis and also promote cell growth. To determine the GlcNAc utilization ability of GlcNAc, FA2-7 and FA2-6 were subjected to feeding with GlcNAc as the sole carbon source. Results demonstrated that FA2-6 could utilize GlcNAc to support its growth with a lag phase of 24 h, whereas FA2-7 was unable to catabolize GlcNAc after all the nag genes were removed (Table S3).

3.3. Improving GlcNAc production by expressing exogenous gna1s

The titer of GlcNAc FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) remained low even after 7 nag genes were removed. Since GNA1 is responsible for catalyzing the critical step in GlcNAc production, it is necessary to explore more active GNA1s to enhance the metabolic flux of the GlcNAc synthesis pathway. 16 exogenous gna1s from the NCBI database were selected based on the similarity of amino acid sequences with ScGNA1 (Fig. 3). In order to study the evolutionary relationships of these GNA1s, the clustering analysis of the amino acid sequences was performed with MEGA 7.0, and was visualized with the EvolView website [40,41]. It was shown that, ScGNA1 belonged to the same clade as Lachancea thermotolerans GNA1 (NCBI accession numbers: XP_002551586.1) and Kluyveromyces lactis GNA1 (NCBI accession numbers: XP_453406.1) (Fig. 3A). The 16 gna1s were synthesized after codon optimization. and were inserted into pACYCDuet-Pals-EcglmS-Pals with KpnI and XhoI, respectively.

Fig. 3.

Verification of the performance of different gna1s within FA2-7 on GlcNAc production in the flasks. (A) Phylogenetic tree of the amino acid sequences among selected 16 gna1s and Scgna1. The color of light blue represents yeast; thistle represents Hymenolepis nana; paleturquoise represents Lactobacillus fermentum; palegoldenrod represents Magnaporthiopsis poae; papayawhip represents other fungi. (B) The Cell growth (OD600) of FA2-7 harboring EcglmS and gna1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (filled circle), Nadsonia fulvescens (filled square), Myceliophthora fergusii (filled triangle), Lachancea thermotolerans (inverted triangle), and Rasamsonia byssochlamydoides (filled diamond). (C) The GlcNAc titer of FA2-7 harboring EcglmS and gna1 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae (filled circle), Nadsonia fulvescens (filled square), Myceliophthora fergusii (filled triangle), Lachancea thermotolerans (inverted triangle), and Rasamsonia byssochlamydoides (filled diamond).

These 16 expression plasmids were introduced into FA2-7 through electroporation. Recombinant strains were tested in flasks containing the chemically defined MKO medium. As shown in Fig. 3C, four strains namely FA2-7 (pA-EG-NG), FA2-7 (pA-EG-MG), FA2-7 (pA-EG-LG), and FA2-7 (pA-EG-RG) exhibited the ability to produce GlcNAc. Notably, FA2-7 (pA-EG-LG) demonstrated the highest production of GlcNAc, reaching 2.1 g/L after 24 h and 2.3 g/L after 36 h, which represent increases of 42.5% and 17.7% compared with those of FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG), respectively. The yield from glucose reached 11.5% (g/g). Compared with the aforementioned strain, the other strains performed poorer. FA2-7 (pA-EG-MG) and (pA-EG-RG) produced GlcNAc below 1.2 g/L after 36 h. Although the strain FA2-7 (pA-EG-LG) produced a higher titer of GlcNAc, it exhibited poorer cell growth compared to other strains. It is possible that GlcNAc production competes using F-6-P with cell growth. Therefore, the cell growth is impaired when the GlcNAc pathway is strengthened [42]. Specifically, the maximum OD600 of FA2-7 (pA-EG-LG) was only 5.5, while the maximum OD600 of FA2-7 (pA-EG-SG) and FA2-7 (pA-EG-RG) were 8.0 and 9.1 after 36 h, respectively (Fig. 3B).

3.4. Tuning GlcNAc synthesis via optimizing the promoter strength of glmS and gna1

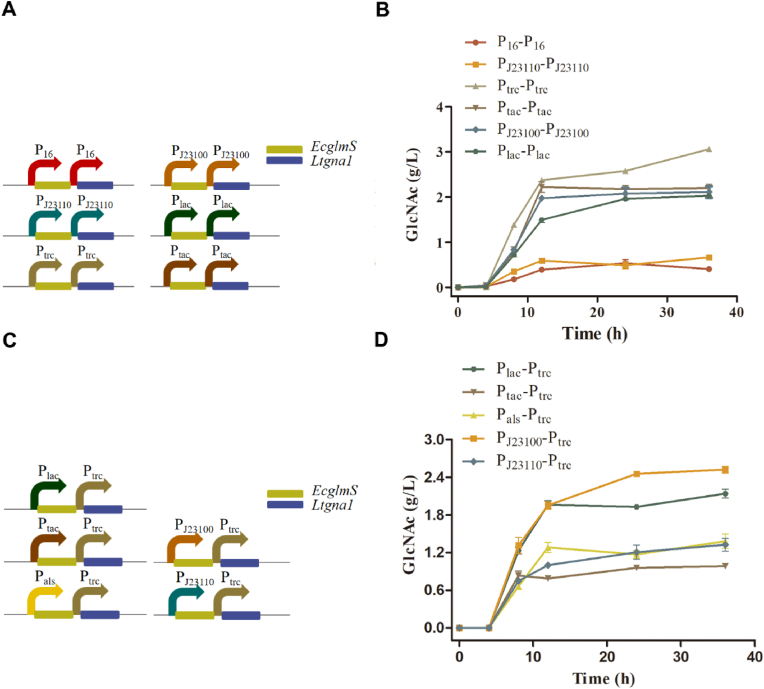

To further optimize the expression levels of glmS and gna1, as well as increase the titer of GlcNAc, we fine-tuned the promoter strength of these two genes. In addition to the Pals promoter, three inducible promoters (Ptrc, Plac, and Ptac) and three constitutive promoters (PJ23110, PJ23100, and P16) with varying strengths were selected [[28], [29], [30]]. Promoter replacement was conducted, followed by the insertion of EcglmS and Ltgna1 in these plasmids, respectively (Fig. 4A). Then, the resulting plasmids were transformed into FA2-7, and the fermentation results of six recombinant strains were shown in Fig. 4B. It indicated that strain FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) outperformed the other strains. It produced 3.1 g/L GlcNAc after 36 h with a yield from glucose of 15.5% (g/g), which was 34.8% higher than the GlcNAc titer of FA2-7 (pA-EG-LG). On the other hand, the strain FA2-7 (p16-EG-LG) exhibited the lowest titer, only 0.4 g/L after 36 h.

Fig. 4.

Optimizing the promoter strength of glmS and gna1 for improving the performance in FA2-7. (A) Diagram of EcglmS and Ltgna1 co-expression regulated with different promoters. (B) Comparison of different promoters on the performance in FA2-7. (C) Diagram of EcglmS and Ltgna1 co-expression regulated with different promoters' combinations. (D) Comparison of diverse promoter combinations on the performance in FA2-7.

It has been reported that a higher expression level of gna1 than glmS is beneficial for achieving higher levels of GlcNAc synthesis [43]. To this end, the expression levels of EcglmS and Ltgna1 were further fine-tuned by combining promoters with varying strengths (Fig. 4C). Specifically, we utilized the stronger Ptrc promoter for Ltgna1 expression, while using other weaker promoters (Plac, PJ23110, PJ23100, Pals, and Ptac) for EcglmS expression. The resulting five plasmids were transferred and tested in FA2-7. As shown in Fig. 4D, the performance of these five strains was all inferior to that of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG). Except for that, the strain FA2-7 (p110T-EG-LG) also displayed favorable performance. The GlcNAc titer of that after 24 h was equal to FA2-7 (pA-EG-LG), and it reached 2.5 g/L after 36 h with a yield from glucose of 14.5% (g/g). While the performance of strain FA2-7 (pTT-EG-LG) was the worst among all test strains. The GlcNAc titer of that was only 1.0 g/L for 36 h, which was only one-third of the highest titer produced by FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) (Fig. 4D). Considering that the GlcNAc production not obviously improved, it may be attributed to the poor expression of the ecGlms and ltGNA1. So, the strain FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) performed the best and was as the strain for the following experiments.

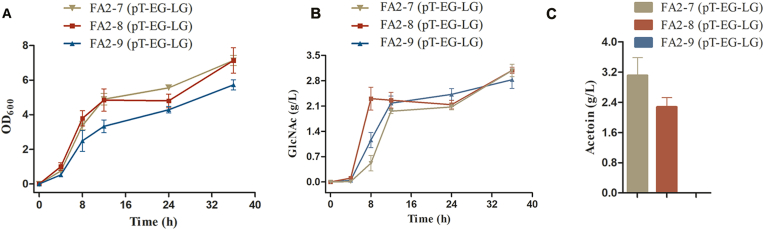

3.5. Effects of alsS and alsD deletion on GlcNAc production

During the fermentation process of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG), acetoin was identified as the primary by-product (Fig. 5), with a concentration of approximately 3.1 g/L after 36 h (Fig. 5C). The alsS and alsD are two important genes related to acetoin production. The former catalyzed the formation of α-acetolactate from pyruvate, and the latter directly catalyzed the formation of acetoin [44]. To prevent the buildup of acetoin, both genes must be removed. Consequently, knocking out alsS led to the creation of FA2-8. We compared the cell growth, GlcNAc production, and acetoin production of FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) and FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) in flasks (Fig. 5). The maximum OD600 and GlcNAc titer of FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) were similar to those of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) (Fig. 5A and B). However, it was noteworthy that the GlcNAc productivity during 4 h–8 h of FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) was 0.6 g/L/h, which was approximately twice as high as that of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) (Fig. 5B). Moreover, we quantified the acetoin produced by FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG), which was approximately 2.3 g/L after 36 h. Compared with FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG), it was a 26.0% decrease of acetoin, while a considerable amount of acetoin still remained. So, the knock of alsS can't absolutely block acetoin formation, another gene alsD also need to be removed.

Fig. 5.

Comparison of cell growth, GlcNAc production, and acetoin accumulation of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG), FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG), and FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG). (A) The cell growth (OD600) of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) (filledinverted triangle), FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) (filled square), and FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG) (filled triangle). (B) The GlcNAc titer of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) (filled inverted triangle), FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) (filled square), and FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG) (filled triangle). (C) The acetoin titer of FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG), FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG), and FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG).

The alsD was attempted to be knocked out by the same method, but it was failed despite multiple attempts. In order to inactivate alsD, we aimed to integrate a fragment of Ptrc-Ltgna1 at the locus of it, resulting in the FA2-9. The growth of FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG) showed apparent inhibition compared with FA2-7 (pT-EG-LG) and FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) (Fig. 5A). The maximum OD600 was only 5.7 at 36 h, which decreased by approximately 20.0% compared with FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG). GlcNAc produced by FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG) also showed a little decrease compared to FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG). The neutral nature of acetoin may contribute to the maintenance of pH stability. Once the synthesis of acetoin is hindered, acid compounds like pyruvate may accumulate, which inhibits glucose uptake, changes the pH, and influences cell growth and GlcNAc production [45]. As shown in Fig. 5C, acetoin did not exist in flasks of FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG), indicating that the acetoin synthesis pathway was completely blocked by the inactivation of alsS and alsD.

3.6. Unsterile open fermentation by FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) in a 5-L fermenter

To establish an unsterile open fermentation process for GlcNAc production, the strain FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) was employed in a 5-L fermenter. Firstly, glucose was tested at initial concentrations of 20 g/L, 30 g/L, and 40 g/L using the MKO medium. The results indicated that a concentration of 40 g/L was optimal for the performance of strain FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) (Fig. S1). Next, an unsterile open fermentation was carried out with an initial glucose concentration of 40 g/L. To promote the cell growth, 0.5 g/L of yeast extract was supplemented before the initiation of fermentation. Additionally, feedings consisting of 28 g sea salt, 7 g (NH4)2SO4, 10 g K2HPO4, and 10 g KH2PO4 were added every 6 h. As depicted in Fig. 6A, GlcNAc titer was the highest after 18 h, with a concentration of 10.9 g/L and a yield from glucose of 8.5% (g/g). The OD600 reached its peak at 16 h with a value of 24.1, which was about 4-fold higher than that of the fermentation without feeding. Surprisingly, acetoin was not detected. Further, we completely removed yeast extract and increased the feeding frequency to every four 4 h with a mixture containing 28 g of sea salt, 7 g of (NH4)2SO4, 10 g of K2HPO4, and 10 g of KH2PO4. As illustrated in Fig. 6B, this modification resulted in a shortened fermentation period of 14 h, with a final GlcNAc concentration of 9.2 g/L, a yield from glucose of 6.7% (g/g), and a final OD600 of 27.0. It can be reasonably inferred that the addition of sea salt and other metal salts significantly promoted cell growth, despite not contributing to GlcNAc synthesis. However, it was observed that when the feeding frequency was increased to every 2 h, cell growth was noticeably impacted, leading to a maximum GlcNAc titer of only approximately 3.5 g/L after 12 h (Fig. S2). Although Vibrio strains are halophilic, they exhibit varying growth patterns in response to different salt concentration conditions. When the salt concentrations are quite high, intracellular enzyme activity is reduced, material transportation is hindered, and growth inhibition also emerges [46].

Fig. 6.

Time course of unsterile open fed-batch fermentation with FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG). Signal denotes: GlcNAc titer (filled circle), Glucose consumption (filled squares), Acetate titer (filled diamond), OD600 (filled triangle). (A) An unsterile open fed-batch fermentation with FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) with a metal-salts feeding frequency at every 6 h. (B) An unsterile open fed-batch fermentation with FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) with a metal-salts feeding frequency at every 4 h.

The strain FA2-9 (pT-EG-LG) was also performed the unsterile open fermentation with a feeding frequency of every 4 h with a mixture containing 28 g of sea salt, 7 g of (NH4)2SO4, 10 g of K2HPO4, and 10 g of KH2PO4. The maximum OD600 was at 16.9 after 14 h, with a GlcNAc concentration of 6.3 g/L (Fig. S3). Similarly, acetoin was not detected during this process.

4. Discussion

V. natriegens ATCC 14048 is acknowledged as the fastest-growing gram-negative bacterium and a promising candidate for being the next-generation workhorse for biotechnology [4,47]. While considering its application in metabolic engineering to bioprocess, the cost of fermentation media also proves to be a significant parameter, especially for large-scale production [7]. Another member of Vibrionaceae family V. alginolyticus FA2, demonstrates even faster growth than that of V. natriegens ATCC 14048 in tested cheap chemically-defined media. Furthermore, its broad substrate spectra and genetic operability render it a highly promising candidate for metabolic engineering [12]. Additionally, the halophilic feature of this organism enhances its potential for employment in open fermentation systems utilizing seawater. In this study, we realized the de-novo synthesis of the valuable compound GlcNAc with V. alginolyticus FA2, facilitated by an unsterile open fermentation process with simulated seawater and a chemically defined medium. After strengthening GlcNAc synthesis pathway, blocking the GlcNAc re-utilization, and removing competing pathways, the recombinant strain FA2-8 (pT-EG-LG) was able to generate 9.2 g/L GlcNAc after 14 h, utilizing an unsterile open fermentation process with a chemically defined medium. This is the first report producing GlcNAc in Vibrio strains, which serves as an excellent foundation for further sustainable and environmentally-friendly biomanufacturer processes.

Rigorous sterilization is imperative for current biomanufacture to avoid contamination. However, it requires abundant capital and labor input, making the production process time-consuming and laborious [13]. Extremophilic microorganisms, such as thermophilic and halophilic bacteria, are expected to adopt non-sterile open fermentation methods to streamline fermentation processes and reduce production costs, due to their unique ability to thrive under extremely specific conditions [7]. Additionally, seawater resources worldwide account for approximately 97% of the total water resources, and expensive desalination processes are required for human consumption and industrial applications [14]. On the other hand, seawater represents an immense reservoir of potential resources, for example, is expected to be directly utilized by halophilic bacteria for biotechnology. Gao has developed an open fermentation process with unsterile seawater to produce 2,3-butanediol with recombinant V. natriegans, thereby confirming the feasibility of non-sterilized fermentation using seawater in further biotechnology [15]. Here, we performed the open fermentation with sea salt and chemically defined medium to synthesize GlcNAc with a recombinant strain, 9.2 g/L GlcNAc after 14 h in a 5-L bioreactor, which decrease the cost, simplified the process, and expected to save freshwater resources. Undoubtedly, seawater that has undergone simple filtration treatment will be directly applied in our future research and scale-up experiments.

Nag genes are commonly responsible for GlcNAc uptake and utilization in many strains, and their removal is an effective means of increasing GlcNAc production [42]. In this work, knocking out nagK and nagK2 based on FA2-5 (pA-EG-SG) resulted in a remarkable increase in GlcNAc titer from the 0.3 g/L to 1.4 g/L after 24 h, representing a 367.0% increase. It indicated that blocking GlcNAc re-utilization is also effective for increasing GlcNAc titer in V. alginolyticus FA2. An interesting observation in V. alginolyticus FA2 is the presence of an additional copy of nagK, which is named nagK2. Although the amino acid sequence of NagK2 has little resemblance to NagK found in V. alginolyticus FA2 or other strains, its removal renders the strain FA2-7 unable to utilize GlcNAc as the sole carbon source in flasks, as compared to FA2-6. It served as a newly discovered enzyme in GlcNAc utilization. Further investigation is required to shed light on this aspect.

In conclusion, this study represents the first report for de-novo synthesizing GlcNAc with a Vibrio strain. With recombinant V. alginolyticus FA2 as the workhorse, we performed unsterile open fermentation using simulated seawater and a chemically defined medium, resulting in the production of 9.2 g/L GlcNAc after 14 h. With the developed fermentation technology, the process is simplified, and the cost is decreased, while also providing valuable insights into the direct utilization of seawater resources to conserve freshwater. This study is the pivotal starting point for V. alginolyticus FA2 serving as the platform for unsterile open fermentation, with the goal of synthesizing valuable compounds such as GlcNAc in a more sustainable and environmentally-friendly manner.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Yuan Peng: Methodology, Validation, Data curation, Writing – original draft. Ping Xu: Conceptualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Fei Tao: Conceptualization, Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing, Supervision.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgement

Funding: This study is supported by the grant from National Natural Science Foundation of China (22138007 and 32170105).

Footnotes

Peer review under responsibility of KeAi Communications Co., Ltd.

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.synbio.2023.08.003.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Austin B., Zachary A., Colwell R.R. Recognition of Beneckea natriegens (Payne et al.) Baumann et al. as a member of the genus Vibrio, as previously proposed by Webb and Payne. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1978;28:315–317. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Eagon R.G. Pseudomonas natriegens, a marine bacterium with a generation time of less than 10 minutes. J Bacteriol. 1961:736–737. doi: 10.1128/jb.83.4.736-737.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ulitzur S. Vibrio parahaemolyticus and Vibrio alginolyticus. Short generation-time marine bacteria. Microb Ecol. 1974;1:127–135. doi: 10.1007/BF02512384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Xu J., Yang S., Yang L. Vibrio natriegens as a host for rapid biotechnology. Trends Biotechnol. 2022;40:381–384. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2021.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hoffart E., Grenz S., Lange J., Nitschel R., Muller F., Schwentner A., et al. High substrate uptake rates empower Vibrio natriegens as production host for industrial biotechnology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2017;83 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01614-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Y., Li Z., Liu Y., Cen X., Liu D., Chen Z. Systems metabolic engineering of Vibrio natriegens for the production of 1,3-propanediol. Metab Eng. 2021;65:52–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2021.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li T., Chen X.B., Chen J.C., Wu Q., Chen G.Q. Open and continuous fermentation: products, conditions and bioprocess economy. Biotechnol J. 2014;9:1503–1511. doi: 10.1002/biot.201400084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ma H., Fan X., Cai N., Zhang D., Zhao G., Wang T., et al. Efficient fermentative production of l-theanine by Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2020;104:119–130. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-10255-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang JQ, Zhao J, Xia JY. γ‑PGA fermentation by Bacillus subtilis PG‑001 with glucosefeedback control pH‑stat strategy. Appl Biochem Biotechnol. 2022;194:1871–1880. doi: 10.1007/s12010-021-03755-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lee S.W., Lee B.Y., Oh M.K. Combination of three methods to reduce glucose metabolic rate for improving N-acetylglucosamine production in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:13191–13198. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.8b04291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matthews C.B., Kuo A., Love K.R., Love J.C. Development of a general defined medium for Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2018;115:103–113. doi: 10.1002/bit.26440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peng Y., Han X., Xu P., Tao F. Next-generation microbial workhorses: comparative genomic analysis of fast-growing Vibrio Strains reveals their biotechnological potential. Biotechnol J. 2020;15 doi: 10.1002/biot.201900499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo Z.W., Ou X.Y., Liang S., Gao H.F., Zhang L.Y., Zong M.H., et al. Recruiting a phosphite dehydrogenase/formamidase-driven antimicrobial contamination system in Bacillus subtilis for nonsterilized fermentation of acetoin. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9:2537–2545. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pistocchi A., Bleninger T., Breyer C., Caldera U., Dorati C., Ganora D., et al. Can seawater desalination be a win-win fix to our water cycle? Water Res. 2020;182 doi: 10.1016/j.watres.2020.115906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meng W., Zhang Y., Ma L., Lu C., Xu P., Ma C., et al. Non-sterilized fermentation of 2,3-butanediol with seawater by metabolic engineered fast-growing Vibrio natriegens. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2022;10 doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.955097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu L., Liu Y., Shin H.D., Chen R., Li J., Du G., et al. Microbial production of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine: advances and perspectives. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:6149–6158. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-4995-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan A.E. An observational cohort study to assess N-acetylglucosamine for COVID-19 treatment in the inpatient setting. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2021;68 doi: 10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mojarrad J.S., Nemati M., Valizadeh H., Ansarin M., Bourbour S. Preparation of glucosamine from exoskeleton of shrimp and predicting production yield by response surface methodology. J Agric Food Chem. 2007;55:2246–2250. doi: 10.1021/jf062983a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang A., Gao C., Wang J., Chen K., Ouyang P. An efficient enzymatic production of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine from crude chitin powders. Green Chem. 2016;18:2147. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang A., He Y., Wei G., Zhou J., Dong W., Chen K., et al. Molecular characterization of a novel chitinase Cm Chi1 from Chitinolyticbacter meiyuanensis SYBC-H1 and its use in N-acetyl-d-glucosamine production. Biotechnol Biofuels. 2018;11:179. doi: 10.1186/s13068-018-1169-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang K., Wang X., Luo H., Wang Y., Wang Y., Tu T., et al. Synergetic fermentation of glucose and glycerol for high-yield N-acetylglucosamine production in Escherichia coli. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:773. doi: 10.3390/ijms23020773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv X., Zhang C., Cui X., Xu X., Wang X., Li J., et al. Assembly of pathway enzymes by engineering functional membrane microdomain components for improved N-acetylglucosamine synthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Metab Eng. 2020;61:96–105. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2020.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S.W., Oh M.K. Improved production of N-acetylglucosamine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by reducing glycolytic flux. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2016;113:2454–2458. doi: 10.1002/bit.26014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng M.D., Severson D.K., Grund A.D., Wassink S.L., Burlingame R.P., Berry A., et al. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for industrial production of glucosamine and N-acetylglucosamine. Metab Eng. 2005;7:201–214. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li P., Lin H., Mi Z., Xing S., Tong Y., Wang J. Screening of polyvalent phage-resistant Escherichia coli strains based on phage receptor analysis. Front Microbiol. 2019;18:850. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Y., Li Y., Jin K., Zhang L., Li J., Liu Y., et al. CRISPR–dCas12a-mediated genetic circuit cascades for multiplexed pathway optimization. Nat Chem Biol. 2023;19:367–377. doi: 10.1038/s41589-022-01230-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhou C., Zhou H., Zhang H., Lu F. Optimization of alkaline protease production by rational deletion of sporulation related genes in Bacillus licheniformis. Microb Cell Factories. 2019;18:127. doi: 10.1186/s12934-019-1174-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang Y., Tao F., Xin B., Liu H., Gao Y., Zhou N.Y., et al. Switch of metabolic status: redirecting metabolic flux for acetoin production from glycerol by activating a silent glycerol catabolism pathway. Metab Eng. 2017;39:90–101. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu F., Chen W., Peng Y., Tu R., Lin Y., Xing J., et al. Design and reconstruction of regulatory parts for fast-frowing Vibrio natriegens synthetic biology. ACS Synth Biol. 2020;9:2399–2409. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.0c00158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brosius J., Erfle M., Storella J. Spacing of the -10 and -35 regions in the tac promoter. Effect on its in vivo activity. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3539–3541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wu H.C., Wu T.C. Isolation and characterization of a glucosaminerequiring mutant of Escherichia coli K-12 defective in glucosamine-6-phosphate synthetase. J Bacteriol. 1971;105:455–466. doi: 10.1128/jb.105.2.455-466.1971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y., Tao F., Xu P. Glycerol dehydrogenase plays a dual role in glycerol metabolism and 2,3-butanediol formation in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:6080–6090. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.525535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peneff C., Mengin-Lecreulx D., Bourne Y. The crystal structures of Apo and complexed Saccharomyces cerevisiae GNA1 shed light on the catalytic mechanism of an amino-sugar N-acetyltransferase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:16328–16334. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009988200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rogers M.J., Ohgi T., Plumhridge J., Söll D. Nucleotide sequences of the Escherichia coli nagE and nagB genes: the structural genes for the N-acetylglucosamine transport protein of the bacterial phosphoenolpyruvate: sugar phosphoferase system and for glucosamine-6-phosphate. Gene. 1988;62:197–207. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(88)90558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jones-Mortimer M.C., Kornberg H.L. Amino-sugar transport systems of Escherichia coli K12. J Bacteriol. 1980;117:369–376. doi: 10.1099/00221287-117-2-369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uehara T., Park J.T. The N-acetyl-d-glucosamine kinase of Escherichia coli and its role in murein recycling. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:7273–7279. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.21.7273-7279.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahangar M.S., Furze C.M., Guy C.S., Cooper C., Maskew K.S., Graham B., et al. Structural and functional determination of homologs of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis N-acetylglucosamine-6-phosphate deacetylase (NagA) J Biol Chem. 2018;293:9770–9783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.002597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Plumbridge J.A. Sequence of the nagBACD operon in Escherichia coli K12 and pattern of transcription within the nag regulon. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:505–515. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00197.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Markov E.Y., Kulikalova E.S., Urbanovich L.Y., Vishnyakov V.S., Balakhonov S.V. Chitin and products of its hydrolysis in Vibrio cholerae ecology. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2015;80:1109–1116. doi: 10.1134/S0006297915090023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol Biol Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang H., Gao S., Lercher M.J., Hu S., Chen W.H. EvolView, an online tool for visualizing, annotating and managing phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40:W569−72. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liu Y., Liu L., Shin H.D., Chen R.R., Li J., Du G., et al. Pathway engineering of Bacillus subtilis for microbial production of N-acetylglucosamine. Metab Eng. 2013;19:107–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2013.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Liu Y., Zhu Y., Li J., Shin H.D., Chen R.R., Du G., et al. Modular pathway engineering of Bacillus subtilis for improved N-acetylglucosamine production. Metab Eng. 2014;23:42–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Renna M.C., Najimudin N., Winik L.R., Zahler S.A. Regulation of the Bacillus subtilis alsS, alsD, and alsR genes involved in post-exponential-phase production of acetoin. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:3863–3875. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.12.3863-3875.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ma W., Liu Y., Shin H.D., Li J., Chen J., Du G. Metabolic engineering of carbon overflow metabolism of Bacillus subtilis for improved N-acetyl-glucosamine production. Bioresour Technol. 2018;250:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu S., Li Y., Wang B., Yin L., Jia X. Effects of NaCl concentration on the behavior of Vibrio brasiliensis and transcriptome analysis. Foods. 2022;11:840. doi: 10.3390/foods11060840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weinstock M.T., Hesek E.D., Wilson C.M., Gibson D.G. Vibrio natriegens as a fast-growing host for molecular biology. Nat Methods. 2016;13:849–851. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.