Abstract

Sludge palm oil (SPO) with high free fatty acid (FFA) content was processed using a continuous and double-step esterification production process in a rotor-stator-type hydrodynamic cavitation reactor. Three-dimensional printed rotor was made of plastic filament and acted as a major element in minimizing the FFA content in SPO. To evaluate the reduced level of FFAs using both methods, five independent factors were varied: methanol content, sulphuric acid content (H2SO4), hole diameter, hole depth, and rotor speed. The first-step conditions for the esterification process included 60.8 vol% methanol content, 7.2 vol% H2SO4 content, 5.0 mm diameter of the hole, 6.1 mm depth of the hole, and 3000 rpm speed of the rotor. The initial free fatty acid content decreased from 89.16 wt% to 35.00 wt% by the predictive model, while 36.69 wt% FFA level and 94.4 vol% washed first-esterified oil yield were obtained from an actual experiment. In the second-step, 1.0 wt% FFA was achieved under the following conditions: 44.5 vol% methanol content, 3.0 vol% H2SO4 content, 4.6 mm hole diameter, 5.8 mm hole depth, and 3000 rpm rotor speed. The actual experiment produced 0.94 wt% FFA content and 93.9 vol% washed second-esterified oil yield. The entire process required an average electricity of 0.137 kWh/L to reduce the FFA level in the SPO below 1 wt%.

Keywords: Sludge palm oil, High free fatty acid oils, Esterification, Hydrodynamic cavitation, Rotor-stator type

1. Introduction

Biodiesel is an effective renewable, sustainable, biodegradable, non-toxic, and ecologically beneficial alternative fuel and energy source [1]. The advantage of biodiesel is its high lubricity, which lowers wear on the engine, fuel pump, and injector unit, and releases fewer greenhouse gases than petroleum-based diesel, such as CO2 (carbon dioxide), CO (carbon monoxide), HC (hydrocarbon), and SO2 (sulfur dioxide) [2]. Biodiesel also emits less smoke and soot and has better combustion efficiency than mineral diesel because of the high oxygen content in biodiesel [3]. In the first and second generations of biodiesel production, biodiesel can be generated from a variety of feedstocks, including edible oils (canola, sunflower, soybean, and palm oil) and non-edible oils [4]. For the next generation of biodiesel feedstock, alternative feedstock resources for producing biodiesel continue to reduce competition for edible sources [5]. Consequently, the major current focus of biodiesel research has been on low-cost raw materials and waste from crude palm oil mills, including palm oil refinery plants. According to several studies, palm oil fatty distillate (PFAD) [6] and sludge palm oil (SPO) [7] could be applied as second-generation biodiesel feedstock. Nevertheless, an enormous amount of waste is generated from the palm oil industry, including palm oil mill effluent (POME), fatty solid residues of SPO, and methane emissions from an open anaerobic pond of POME. Furthermore, when palm oil plant residuals and wastewater are dumped directly into the soil around the industrial area without being treated, its quality deteriorates. Consequently, their acidic, viscous, and greasy properties may pollute groundwater and cause odors in nearby industrial areas [8]. POME was produced by sterilizing crude palm oil, double screw pressing, and separating separator sludge, with 1000 kg of fresh fruit bunch (FFB) producing almost 0.5–0.75 tonnes of POME [9]. To process one ton of FFB, a palm oil mill must approximately produce 1.5 m3 of wastewater [10]. POME composition influences the bacteria during anaerobic digestion and biogas production. This energy source can be used to generate steam and electricity for plants, thereby minimizing the running and effluent treatment costs [11]. In the cooling pond, the residual oil in POME was further digested, leading to the production of long-fatty acids and glycerol derivatives. Because of its lower density, the settling grease on the upper layer of POME is called SPO, which has over 20 wt% free fatty acid (FFA) level. SPO can be used as a low-cost feedstock for animal feed, low-grade soap, biogas, and biodiesel production [12]. However, POME containing more than 1.6 g/L residual oil may cause anaerobic digestion to become unstable, generating volatile fatty acids and increasing foaming. Furthermore, excessive oil concentrations in biogas production might hinder hydrogenotrophic and acetoclastic methanogens from operating, resulting in decreased methane production and loss of biogas ecosystems [13]. Thus, de-oiling is necessary to eliminate excessive floating fat in POME via a ponding system to enhance biogas yield [14].

In terms of waste-to-energy technology, converting low-quality oil into biodiesel is a simple method for enhancing the FFA content of raw materials from palm oil mills. However, when reacted with a base catalyst in the transesterification process, the rich FFA content of SPO may result in soap formation via the saponification reaction, resulting in a low biodiesel yield [15]. Consequently, the high FFA levels in SPO should be decreased to less than 2% by esterification [16]. Skrbic et al. (2015) [7] investigated the acid esterification of SPO in a batch reactor with a capacity of 200 g using a 6:1 methanol-to-oil molar ratio of 4.6 wt% sulphuric acid content, and a stirring speed of 400 rpm for 120 min at 65 °C, minimize the FFA to 1.5 wt% from 50 wt% initial FFA [7]. Juera–Ong et al. (2022) [17] used Amberlyst-15 as a solid catalyst to reduce FFA from SPO via esterification. They found that FFA sharply decreased to 1.75 wt% under the following condition of 5:1 methanol to oil molar ratio, 40 wt% Amberlyst-15 catalyst, 5 h reaction time, and 300 rpm stirring speed at 60 °C [17]. In terms of very high FFA level raw materials, Alvarez-Mateos et al. (2019) [18] found the most suitable conditions to reduce the FFA content of a residual oil of 60.5 wt% initial FFA content to 1.0 wt% included 15:1 methanol to oil molar ratio, 5 wt% sulphuric acid content as homogenous catalyst, 2 h reaction time, 60 °C, and 700 rpm stirring in a batch reactor. Therefore, a high FFA level in residual oil can be employed as feedstock for biodiesel production [18].

Various mixing technologies for continuous stirred tank reactors (CSTR) [19], static mixers (SM) [20], plug flow reactors (PFR) [21], and microreactors [22] have been used for continuous biodiesel production. The limitations of using a conventional reactor include a lower reaction rate, longer reaction time, greater molar ratio, and higher catalyst requirements [23]. Some mixing methods have been developed to rapidly combine two immiscible liquids with a short retention time, which increases the mixing intensity. Recently, hydrodynamic cavitation reactor (HCR) has been proposed as an effective method for continuous biodiesel synthesis [24]. Hydrodynamic cavitation (HC) is characterized by the rapid nucleation, development, and implosion of vapor-phase cavities. HC can be induced by either an increase in flow velocity or a decrease in liquid static pressure when it flows through specialized obstruction designs [25]. When the static pressure of the liquid drops below the liquid vapor pressure, cavitation vapor in the liquid begins to develop because the pressure inside the bubble exceeds the surface tension. Consequently, when the flow pressure is restored, the generated bubbles become unstable, collapse, and explode. When bubbles collapse, mechanical shock waves and thermal stress release an enormous amount of energy into the surrounding liquids [26]. Two types of cavitation systems exist: static and dynamic systems. To create HC in static elements, throttling valves of the orifice and venturi types are often employed as reactors. A simple valve can also be employed to produce cavitation, which depends on the shape and opening space [27]. For hydrodynamic systems, the shear rate and local energy dissipation are both increased in dynamic systems with rotor-stator rotational devices. Shear cavitation occurs in the HCR as a result of the rotor rotation, stator, and liquid flow between the rotor and stator [28]. Hydrodynamic cavitators can be used for a variety of applications, including biological equipment [29], biofuel production [24], biogas production [30], emulsification [31], food and beverage processing [32], organic solvent degradation [33], and water treatment [34]. In addition, HC is more cost-effective, consumes less energy, has a faster reaction time, and can be used on a larger scale compared to other continuous reactors [23].

In the field of biodiesel production using HC, most research has focused on cavitation in orifice and venturi pipeline systems. For example, Chuah et al. (2017) [35] reported that orifice plate-type HC shows good potential for methyl ester synthesis from used cooking oil. The highest biodiesel purity of 98 % was achieved at the conditions of 6:1 M ratio of methanol to oil, 1 wt% KOH and 15 min reaction time at 60 °C. They found that 98 % methyl ester conversion was achieved in 15 min with orifice plate HC, superior to mechanical stirring with 19 % conversion under a comparable reaction time. Additionally, the HCR required a 3.0 kJ/mol activation energy lower than that for the mechanical stirrer. Consequently, in terms of energy and time savings, orifice plate-type HC outperformed mechanical agitation [35]. Chisaz et al. (2018) [36] studied the venturi type using response surface methodology (RSM) to determine the highest purity of methyl ester from waste sunflower oil biodiesel production. The methyl ester purity was estimated to be 97.56% by the predictive model, while 95.6% was proved by the actual experiment under the optimum conditions of 6:1 methanol to oil molar ratio, 1.1 wt% KOH, 0.327 MPa inlet pressure, and 8 min of circulation time at 63 °C [36].

However, the synthesis of methyl esters by transesterification, particularly the high FFA reduction in oils via acid-catalyzed esterification, has not been thoroughly investigated in terms of a dynamic HC system. Samani et al. (2021) [24] studied a continuous rotor-stator-type HC to enhance methyl ester conversion from safflower oils. The rotor was operated at 3200 rpm and had a diameter of 90 mm, 40 holes on its surface, a gap of 15.3 mm between the rotor and stator, and a hole diameter of 4 mm. They found that 89.11% highest yield of biodiesel was achieved under the recommended condition of 63.88 s residence time, 0.94 wt% KOH, and 8.36:1 methanol to oil molar ratio. Moreover, they found that HCR provides a drastic increase in mixing, has a shorter reaction retention time, operates on basic principles, and is easily applicable on an industrial scale [24].

A few studies have investigated continuous HC with esterification reactions to reduce FFA in oil. Gole et al. (2013) [37] observed FFA reduction in raw Nagchampa oil via a double-step esterification process using an orifice plate-type HCR. The acid value (AV) was reduced from 18.7 to 3.7 mg KOH/g via the first-stage esterification process under the optimal condition of 4:1 methanol to oil molar ratio, 1 wt% H2SO4, and 60 min reaction time. In the second-stage, the initial AV in oil was further decreased to 1.6 mg KOH/g at a 1:1 methanol-to-oil molar ratio of 1 wt% H2SO4, and 50 min reaction time. Moreover, HC provides a higher cavitation yield than ultrasonic cavitation and the conventional method [37]. Bokhari et al. (2016) [38] utilized an orifice plate-type HC to perform esterification of rubber seed oil. They reported that the optimal conditions included 6:1 methanol/oil molar ratio, 8 wt% H2SO4, and 30 min reaction time at 55 °C, which lowered the AV in oils arranged from 72.36 to 2.64 mg KOH/g. To bring induced cavitation, a 1 mm in diameter and 21-hole optimized orifice plate with an inlet pressure of 0.3 MPa was used. In addition, compared to the traditional technique, HC requires less time to complete the reaction and produces more efficient esterification [38].

To the best of our knowledge, no research has been conducted on a continuous rotor-stator type HCR for the double-step esterification production process of SPO, which is almost completely composed of 89.16 wt% FFA content. Because the produced wastewater dilutes the concentrations of alcohol and catalyst throughout the operation, a double-step esterification procedure was used to remove more than 89 wt% initial FFA content, which is effective for minimizing chemical consumption [39], [40]. Therefore, the objective of this work was to find the lowest FFA content in esterified oil from a continuous double-step esterification process using a 3D-printed rotating HCR, for which RSM was used to analyze the five parameters of methanol content, sulphuric acid content, hole diameter, hole depth, and rotor speed. The esterified oil composition, physical properties, esterified oil yields, residual methanol, and average electricity consumption for the continuous double-step acid-catalyzed esterification production process were examined.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

The SPO was obtained from an open settlement pond at a large palm oil mill plant in the southern area of Thailand. SPO has a dark brown color and is commonly found in the wax phase at room temperature (30±2 °C), as shown in Fig. 1a. Fig. 1b and c show the esterified oil after the complete phase separation process, where gravity separation took at least 4 h to separate the black phase of the generated wastewater, which settled to the bottom of the bottle. Before the washing process by water, the products obtained from the first- and second-step esterification reactions are the esterified oil and the generated wastewater, which the waste consists of water, methanol, and sulphuric acid. Fig. 1d shows the second-esterified oil after the washing method. The major composition of the SPO was 89.16 wt% FFA content, with other compositions of 9.79 wt% triglyceride (TG), 0.80 wt% diglyceride (DG), and 0.24 wt% monoglyceride (MG) contents. SPO had a fatty acid profile that contained 40.28 wt% palmitic acid, 37.12 wt% oleic acid, 8.46 wt% linoleic acid, and 4.63 wt% stearic acid. The commercial grades of methanol (99.7%) and sulphuric acid (98%) were employed as chemical reagents in the esterification process. All components in esterified oil, that is, methyl ester (ME), TG, DG, MG, and FFA, were evaluated using thin-layer chromatography with flame ionization detection (TLC/FID; model: Iatroscan MK-65, Mitsubishi Kagaku Latron Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Analytical grade formic acid, hexane, benzene, diethyl ether, and isopropanol were used to assess the composition of SPO and oils.

Fig. 1.

SPO and products from the two-stage FFA reduction process using HCR, (a) SPO at room temperature (30±2 °C) (b) the first-esterified oil (top phase) and generated wastewater (bottom phase), (c) the second-esterified oil (top phase) and generated wastewater (bottom phase), and (d) second-esterified oil after washing process.

2.2. Hydrodynamic cavitation reactor

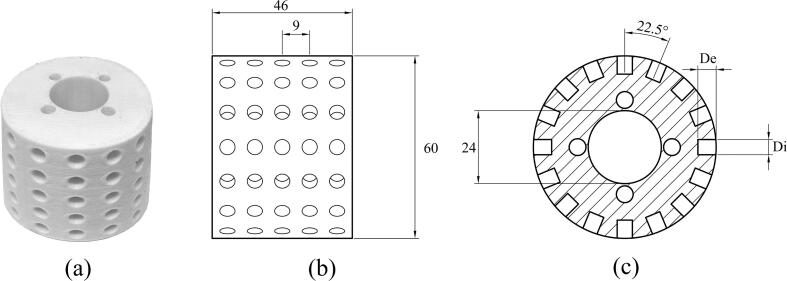

The key component of this study is the HCR, which consists of a stationary stator with a rotating rotor to generate cavitation bubble collapse. A 3D printer was used to build the 3D-printed rotor (model: Creator 3, FlashForge, China). Acryliconitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) filaments were used to print solid objects. As shown in Fig. 2, the diameter and length of the rotor were set to 60 and 46 mm, respectively. The stator part was made of stainless steel and had an 80 mm diameter, with a 10 mm gap thickness between the stator and rotor. There were 80 cylinder holes on the rotor's surface, their diameters varied from 3 to 7 mm, and their depths were in the range of 2–10 mm. A three-phase electric motor drove a 3D-printed rotor (model: MG112MC, Grundfos, Taiwan). An adjustable frequency inverter (model: M201, Emerson, China) regulated the rotor speeds, which were checked using a digital tachometer (model: DT2236B, Lutron, Taiwan).

Fig. 2.

3D-printed rotor. (a) actual prototype, (b) side-view dimensional, and (c) cross-sectional drawing of the rotor.

2.3. Procedure

A flowchart of the continuous double-step esterification production using SPO is shown in Fig. 3. To melt the semi-solid phase of SPO into the liquid phase, the SPO from the open pond in tank T1 was heated to 60 °C using a 1 kW band heater with a 0.030 kW single-phase electrical mixer (model: RW 20 digital, IKA, Germany). A sieve with a 0.4 mm wire mesh was used to remove any residual palm fibers and palm cake that might block the pump before being poured into the SPO tank (T3). To obtain a homogeneous phase and maintain a constant reaction temperature of 60 °C, a 1 kW immersion heater was activated with a 0.030 kW circulation pump (P1, model: PMD-371, Sanso, Japan). The temperature of the mixture was measured using a digital thermometer (model: 51 II, Fluke, China). Subsequently, a circulation pump (P1, model: PMD-371, Sanso, Japan) was used to mix the SPO in tank T3 with methanol at room temperature (30±2 °C) from tank T2. Therefore, the temperature of the mixtures in tank T3 decreased to approximately 48 °C when the premixing process began. When the SPO mixed with methanol reached a temperature of 60 °C, a digital dosing pump (P2, model: DME48-3A, Grundfos, France) was turned on to feed the 25 L/h mixture in tank T3 into the first-step HCR (HCR1) through the inlet port. A chemical dosing pump (P3, model: DDC6-10, Grundfos, France) was used to immediately pump sulphuric acid from tank T4. The mixtures of these three solutions of (SPO, two chemical reagents of sulphuric acid and methanol) were passed through HCR1 for the first-step. When the mixture in the reactor flowed out of the outlet port, the motor started driving the rotor in the reactor. To collect a sample, oils at the sampling port (S1) were taken and placed in an ice box to stop the reaction. After samples were taken at the outlet port of HCR1, the products flowed into the first-step separator tank (T5), where they were separated into two phases: generated wastewater and first-esterified oil. Following the removal of the wastewater, the oil that had been esterified in the first-step was used in the preparation of the raw material for the pretreatment process that would continue in the second-step, using the HCR in the second-step (HCR2). In the raw material of second-step, the first-esterified oil in tank T6 was heated to 60 °C, following the same technique as in the first-step. All these solutions in the tanks (T6 and T8) were pumped to HCR2 of the second-step using chemical dosing pumps (P4, model: DME48-3A, Grundfos, France), and (P5, model: DDC6-10, Grundfos, France), respectively. The sample port (S2) was collected after the mixture from the second-step flowed out of the reactor's output port to evaluate the compositions of the oils. When the reaction was complete, the second-esterified oil and generated wastewater were delivered to the second-step separation tank, T9. To analyze the compositions of oils from both stages, the second-esterified oil phase was separated from the generated wastewater phase by simple gravitational sedimentation, while the upper layer was washed with water to eliminate the impurities of the residual catalyst and methanol. After the washing process, the samples must be heated to approximately 105 °C to separate the unwanted water. At this condition, dissolved or suspended water in the sample falls to the bottom of the container, while the upper layer of esterified oil is taken [41]. Finally, the TLC/FID technique was used to determine the levels of ME, TG, FFA, DG, and MG in the oils of all washed samples.

Fig. 3.

Schematic for the two-stage FFA reduction process from SPO using continuous HCR. (T1: SPO tank, T2 and T7: methanol tank, T3: SPO + methanol tank, T4 and T8: H2SO4 tank, T5 and T9: separator, T6: first-esterified oil + methanol tank, P1: circulating pump, P2: SPO + methanol pump, P3: H2SO4 pump, P4: first-esterified oil + methanol pump, P5: H2SO4 pump, RO: rotor, HT: heater, HCR: reactor, C: flexible coupling, SH: shaft, F: flange, and ST: stator).

2.4. Design of experiment

RSM was used to assess the reduction in FFA levels in continuous double-step esterification production from SPO utilizing an HCR and to determine the optimal values of five independent variables: methanol content, sulphuric acid content, hole diameter, hole depth, and rotor speed. In this central composite design (CCD) model, five levels (−2, −1, 0, +1, and +2) and five factors were used to find the lowest FFA level in both the first- and second-processing steps. Therefore, the range of each parameter, that is, methanol concentration (15–75 vol%), sulphuric acid (1.5–7.5 vol%), hole diameter (3–7 mm), hole depth (2–10 mm), and rotor speed (1000–5000 rpm) on the response parameter of FFA level for both steps, where the parameter ranges for both processes were run at the same value, as listed in Table 1. The experimental design and FFA results for both the processes are listed in Table 2. The 2nd degree polynomial of the RSM was used to evaluate the FFA obtained after esterification, as expressed in Eq. (1). The predicted models were solved using Microsoft Excel to determine predictive conditions. To validate the data with the prediction models, model fit was evaluated using variance analysis (ANOVA) at a 95% confidence level. In addition, the relationship between the independent variables of the first- and second-esterification processes is shown using contour plots of FFA levels.

| (1) |

where Y is the response parameter, xi and xj are the independent variables, ε is the error, k is the number of variables, and the coefficients of the intercept, linear, quadratic, and interaction terms are denoted by β0, βi, βii, and βij, respectively.

Table 1.

Independent variable codes.

| Independent variable | Unit | Levels |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | |||

| M | Methanol | vol% | 15 | 30 | 45 | 60 | 75 |

| C | Sulphuric acid | vol% | 1.5 | 3.0 | 4.5 | 6.0 | 7.5 |

| Di | Diameter of the hole | mm | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| De | Depth of the hole | mm | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 10 |

| S | Speed of rotor | rpm | 1000 | 2000 | 3000 | 4000 | 5000 |

Note: The parameter ranges for both processes were run at the same value.

Table 2.

Design of experiment matrix and FFA contents obtained from continuous HCR for the first- and second-step esterification processes.

| Run | M (vol%) | C (vol%) | Di (mm) | De (mm) | S (rpm) | FFA1 (wt%) | FFA2 (wt%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | 4.5 | 3 | 6 | 3000 | 55.56 | 0.85 |

| 2 | 30 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4000 | 66.18 | 1.69 |

| 3 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 2000 | 63.05 | 1.67 |

| 4 | 60 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2000 | 53.29 | 0.83 |

| 5 | 60 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4000 | 39.77 | 0.68 |

| 6 | 30 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 2000 | 69.49 | 1.76 |

| 7 | 30 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 4000 | 64.48 | 1.46 |

| 8 | 60 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 4000 | 46.08 | 0.75 |

| 9 | 60 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 2000 | 43.97 | 0.57 |

| 10 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 2 | 3000 | 48.78 | 1.12 |

| 11 | 15 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 76.85 | 2.19 |

| 12 | 45 | 1.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 56.66 | 1.49 |

| 13 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 1000 | 52.43 | 0.93 |

| 14 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 44.72 | 0.74 |

| 15 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 44.70 | 0.74 |

| 16 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 44.81 | 0.73 |

| 17 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 44.93 | 0.74 |

| 18 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 5000 | 44.46 | 0.79 |

| 19 | 45 | 7.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 41.10 | 0.96 |

| 20 | 75 | 4.5 | 5 | 6 | 3000 | 40.17 | 0.38 |

| 21 | 45 | 4.5 | 5 | 10 | 3000 | 51.68 | 1.05 |

| 22 | 30 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 2000 | 64.32 | 1.78 |

| 23 | 30 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 4000 | 61.80 | 1.46 |

| 24 | 60 | 3 | 6 | 4 | 4000 | 45.47 | 0.69 |

| 25 | 60 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 2000 | 43.17 | 0.60 |

| 26 | 30 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 4000 | 62.05 | 1.63 |

| 27 | 30 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 2000 | 58.22 | 1.41 |

| 28 | 60 | 3 | 6 | 8 | 2000 | 54.01 | 0.84 |

| 29 | 60 | 6 | 6 | 8 | 4000 | 40.20 | 0.51 |

| 30 | 45 | 4.5 | 7 | 6 | 3000 | 53.88 | 0.82 |

Note: M, methanol; C, sulphuric acid; Di, hole diameter; De, hole depth; S, rotor speed; FFA, free fatty acid.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Experimental results

The experimental design matrices for the first- and second-esterification steps, using HC as the reactor, are listed in Table 2. According to the RSM experimental design, 30 conditions per step existed, in which five independent variables, including methanol content, sulphuric acid content, hole diameter, hole depth, and rotor speed, were varied to investigate the reduction in FFA levels in the oils. According to the results described in Table 2, the first-step range of methyl esters produced from the initial FFA levels in SPO was between 39.77 and 76.85 wt% of FFA. Additionally, the FFA content in the esterified oil obtained from the second-step process ranged between 0.38 and 2.19 wt%. Two predictive models, namely, the first-step in Eq. (2), and the second-step in Eq. (3), were obtained by evaluating all experimental conditions from both steps using Microsoft Excel Solver. The coefficients, p-value, coefficients of determination (R2), and adjusted coefficients of determination (R2adjested) of the fitted model for both processing steps are shown in Table 3. Table 4 shows the ANOVA results for each model of the double-step esterification production.

| (2) |

| (3) |

Table 3.

Statistical values of prediction models.

| Term | First-step |

Second-step |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Value | p-value | Value | p-value | |

| β0 | 225.11 | 1.9446×10−13 | 6.4628 | 3.2837×10−13 |

| β1 | −1.8824 | 9.9163×10−10 | −0.085933 | 9.6092×10−16 |

| β2 | −7.0571 | 1.2521×10−5 | −0.48558 | 1.8867×10−8 |

| β3 | −30.226 | 6.0477×10−10 | −0.22354 | 7.6139×10−3 |

| β4 | −4.3628 | 3.8457×10−6 | −0.23565 | 4.8092×10−8 |

| β5 | −7.3969×10−3 | 4.6471×10−4 | −2.8712x10−4 | 2.4599×10−5 |

| β6 | 0.015887 | 1.9457×10−11 | 6.1500x10−4 | 7.2977×10−13 |

| β7 | 0.51872 | 3.7938×10−5 | 0.054833 | 4.2574×10−12 |

| β8 | 2.6271 | 1.5045×10−9 | 0.025875 | 1.5526×10−3 |

| β9 | 0.37616 | 2.1455×10−6 | 0.022094 | 6.4014×10−10 |

| β10 | 1.0584×10−6 | 1.0374×10−4 | 3.2125x10−8 | 2.2862×10−4 |

| β11 | −0.047917 | 9.1097×10−4 | −0.012917 | 0.042220 |

| β12 | 0.068958 | 1.2793×10−3 | −9.3750×10−3 | 5.5245×10−3 |

| β13 | −9.3125×10−5 | 8.3094×10−5 | 1.2917×10−5 | 0.042220 |

| β14 | 7.9875×10−4 | 3.6305×10−4 | – | – |

| R2 | 0.994 | 0.997 | ||

| R2adjusted | 0.989 | 0.994 | ||

Table 4.

ANOVA analysis for each response surface model.

| Source | SS | SS% | MS | F0 | Fcrit | DOF |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-step esterification | ||||||

| Regression | 2851.4 | 99 | 203.67 | 185.78 | 2.43 | 14 |

| Residual | 16.44 | 1 | 1.096 | 15 | ||

| LOF Error | 16.41 | 1 (100) | 1.368 | 124.33 | 8.74 | 12 |

| Pure Error | 0.03300 | 0 (0) | 0.01100 | 3 | ||

| Total | 2867.8 | 100 | 29 | |||

| Second-step esterification | ||||||

| Regression | 6.303 | 100 | 0.485 | 393.42 | 2.40 | 13 |

| Residual | 0.01972 | 0 | 0.00123 | 16 | ||

| LOF Error | 0.01964 | 0 (100) | 0.00151 | 60.44 | 8.73 | 13 |

| Pure Error | 7.5×10−5 | 0 (0) | 0.000025 | 3 | ||

| Total | 6.323 | 100 | 29 | |||

3.2. Statistical analysis of the fitted models

A regression analysis was performed to fit the second-degree polynomial model from the continuous double-step esterification production, as expressed in Eqs. (2), (3), for the first- and second-steps, respectively. The p-value, which is an important variable for evaluating the statistical significance of each regression coefficient in the model, was analyzed to determine the significance of each term in the regressed model [42]. Consequently, when the p-values were less than 0.05, at a corresponding confidence level of 95%, these coefficient values had an influence on FFA reduction in oils. If the p-value exceeded 0.05, the coefficient values were removed from the prediction model [43]. Table 3 shows the coefficient and p-value of each term for the first- and second-steps after considering the significance of each term. For the first-step, the lowest p-value of 1.95×10−11 was found in the quadratic term of methanol . Simultaneously, the second-, third-, and fourth-place rankings were obtained in the linear term of hole diameter , the linear term of methanol , and the quadratic term of hole diameter , respectively. Furthermore, changing the amount of methanol and the hole diameters in the first-step had a significant influence on FFA reduction in SPO. Therefore, the amount of methanol provided is the most important variable in the first-step. The hole diameter was the second most important variable. For the second-esterification step, the lowest p-value of 9.61×10−16 was found in the linear term of methanol β1M2 in Eq. (3). Therefore, methanol is the most important variable, and the second-, third-, and fourth-place rankings for the second-step were obtained in the quadratic term of methanol of the hole , the quadratic term of sulphuric acid , and the quadratic term of hole depth , respectively. These significant parameters of methanol content, sulphuric acid concentrations, and hole depth clearly demonstrated that when partial FFA content in SPO was converted to methyl ester, it had a considerable influence on the methyl ester synthesis process for the second-step using an HCR. When the methanol concentration of both processes was considered, the methanol concentration was an important factor in both processes, allowing for the reduction of FFA levels in SPO and the synthesis of methyl ester from first-esterified oil in the HCR. Similar results were obtained by Kostic et al. (2016) [44], who studied the optimization of the FFA pretreatment process from waste plum stones using sulphuric acid as an acid catalyst. They found that using an 8.5:1 methanol-to-oil molar ratio of 2 wt% H2SO4 at 45 °C for 60 min, the AV in plum stone kernels oil could be reduced from 31.60 to 0.53 mg KOH/g. They determined that when the methanol-to-oil molar ratio increased, AV decreased precipitously. Accordingly, the process of neutralizing AV was significantly affected by the presence of methanol. [44]. The prediction model’s coefficient of multiple determination (R2) and adjusted coefficient of multiple determination (R2adjusted) were 0.994 and 0.989 for the first-step and 0.997 and 0.994 for the second-step, respectively. The statistical analysis results of R2 and R2adjusted values for all steps were close to 1.00, indicating that the models and expected outcomes were closely related or that the actual and predicted outcomes were in good agreement. In addition, ANOVA with a 95% confidence level, as listed in Table 4. The relevance of the two prediction models was also assessed. The lack of fit (LOF) tests were employed in the ANOVA to determine whether the descriptive models adequately explained the experimental data. The F-test was used to assess the significance [45]. Based on the results, the computed F-values were 185.78 and 393.42, which were higher than the tabulated Fcrit values of 2.43 and 2.40 for the first- and second-steps, respectively. Furthermore, the LOF value was determined to be insignificant for the fitted model [46]. The computed lack of fit values of 124.33 and 60.44 were greater than the Fcrit values of 8.74 and 8.73 for first- and second-step, respectively, as shown in Table 4.

3.3. Response surface plots

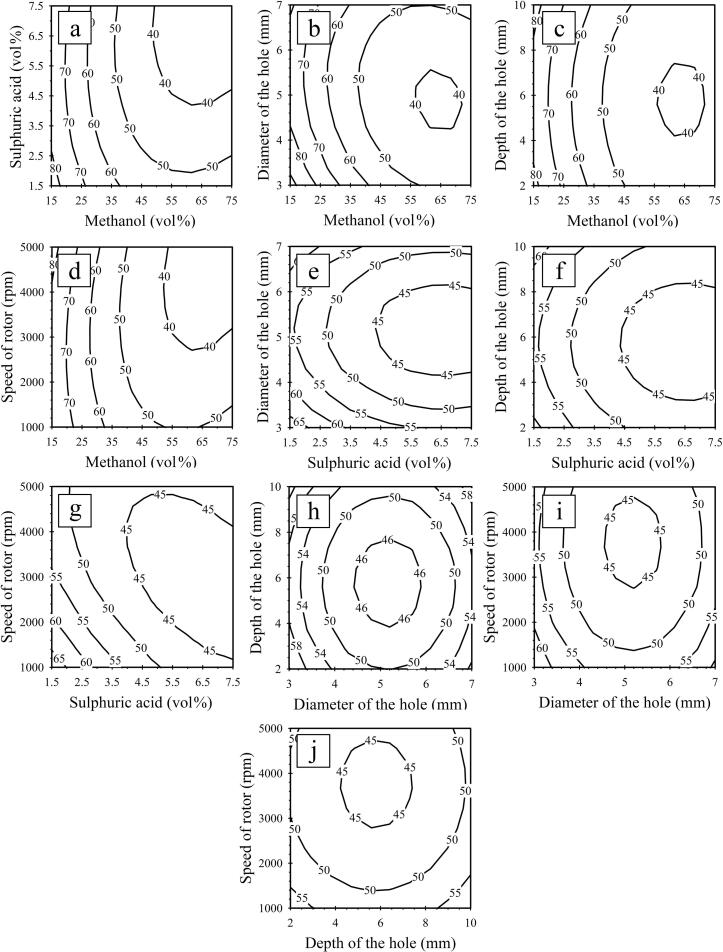

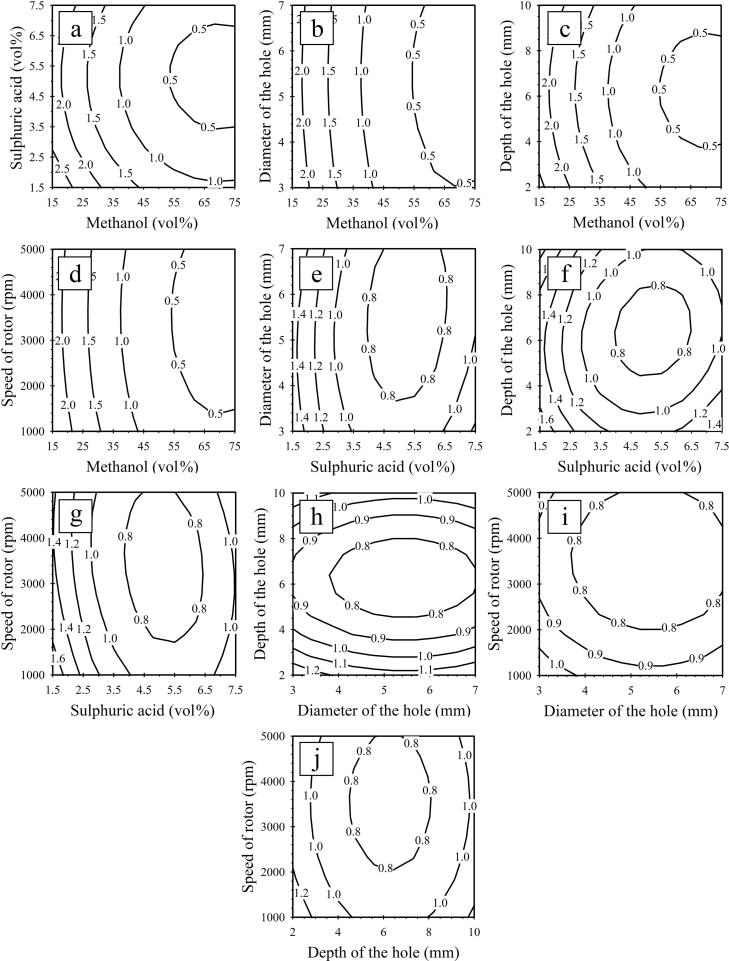

The effects of five independent variables (methanol content, sulphuric acid content, hole diameter, hole depth, and rotor speed) on the first- and second-step FFA reduction processes from the SPO through the HCR are shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Contour plots for the first-step FFA reduction process from SPO using HCR, (a, b, c, and d) effects of methanol with sulphuric acid, diameter of the hole, depth of the hole, and rotor speed, (e, f, and g) effects of sulphuric acid with diameter of the hole, depth of the hole, and rotor speed, (h and i) effects of diameter of the hole with depth of the hole, and rotor speed, (j) effects of depth of the hole with rotor speed on the amount of FFAs.

Fig. 5.

Contour plots for the second-step FFA reduction process from SPO using HCR, (a, b, c, and d) effects of methanol with sulphuric acid, diameter of the hole, depth of the hole, and rotor speed, (e, f, and g) effects of sulphuric acid with diameter of the hole, depth of the hole, and rotor speed, (h and i) effects of diameter of the hole with depth of the hole, and rotor speed, (j) effects of depth of the hole with rotor speed on the amount of FFAs.

3.4. Optimal conditions

The optimal conditions for minimizing FFA levels in SPO using double-step esterification production were determined by applying the models in Eqs. (2), (3) for the first- and second-step processes, respectively. In the first-step, the predictive FFA model in Eq. (2) predicted 33.31 wt%, and the actual experiment revealed that the initial FFA content in SPO of 89.16 wt% was decreased to less than 34.83 wt% under the optimal conditions of 71.0 vol% methanol content (6.2:1 methanol to oil molar ratio), 7.0 vol% sulphuric acid content, 4.8 mm hole diameter, 5.8 mm hole depth, and 3966 rpm rotor speed, as shown in Table 5. However, under these conditions, methanol consumption is high, resulting in high chemical costs. Thus, a 33.31 wt% predicted FFA level was entered into FFA1, and a low and sufficient methanol content is suggested for the first-step. To lower the amount of methanol used, the desired FFA value of 35.00 wt% was added to Eq. (2) in the first-step model to obtain the dependent variable FFA. Subsequently, five independent variables, that is, M1, C1, Di1, De1, and S1, were solved using a solver in Microsoft Excel. The results indicated that the new recommended conditions for the first-step included 60.8 vol% methanol content (5.3:1 methanol to oil molar ratio), 7.2 vol% sulphuric acid content, 5.0 mm hole diameter, 6.1 mm hole depth, and 3000 rpm rotor speed, provided 35.00 wt% FFA content in the prediction model (Eq. (2). Consequently, this recommended condition for the first-step can save the methanol consumption up to 14.4% in the HCR.

Table 5.

Conditions for first- and second-steps of continuous esterification using HCR.

| Variable | Condition |

|

|---|---|---|

| Optimized | Recommended | |

| First-step esterification M1: Methanol (vol%) C1: Sulphuric acid (vol%) Di1: Diameter of the hole (mm) De1: Depth of the hole (mm) S1: Speed of rotor (rpm) FFA1: Predictive FFA for the first-step (wt%) FFA1,actual: Actual FFA from the experiment (wt%)Yield of first-step esterified oil (vol%) no washing |

71.0 7.0 4.8 5.8 3966 33.31 34.83 117.4 |

60.8 7.2 5.0 6.1 3000 35.00 36.69 109.8 |

| Second-step esterification M2: Methanol (vol%) C2: Sulphuric acid (vol%) Di2: Diameter of the hole (mm) De2: Depth of the hole (mm) S2: Speed of rotor (rpm) FFA2: Predictive FFA for the second-step (wt%) FFA2,actual: Actual FFA from the experiment (wt%) Yield of second-step esterified oil (vol%) no washing Yield of second-step esterified oil (vol%) washing |

69.9 5.2 5.6 6.4 3416 0.31 0.35 114.4 93.6 |

44.5 3.0 4.6 5.8 3000 1.00 0.94 105.3 93.9 |

The FFA content in the second-step was lowered from 0.38 to 2.19 wt%, as shown in Table 2. Based on the prediction model in Eq. (3), the lowest concentration of 0.31 wt% FFA was obtained in the second-phase under the optimal conditions of 69.9 vol% methanol (6.3:1 methanol to oil molar ratio), 5.2 vol% sulphuric acid content, 5.6 mm hole diameter, 6.4 mm hole depth, and 3416 rpm rotor speed. Similar to the first-step in terms of the cost and consumption of chemical reactants, the biggest problem is that the FFA level in oil should not exceed 1 wt% for the first-step when this oil will be used as raw material for transesterification to produce methyl ester. Therefore, 1.00 wt% of FFA2 was substituted into Eq. (3). Parameters including 44.5 vol% methanol content (4.0:1 methanol to oil molar ratio), 3.0 vol% sulphuric acid content, 4.6 mm hole diameter, 5.8 mm hole depth, and 3000 rpm rotor speed were determined to be suggestions for the second-step. Finally, both the new recommended conditions for the first- and second-steps were validated by actual experiments, which indicated that the FFA contents were reduced to less than 36.69 wt% FFA for the first-step and 0.94 wt% FFA for the second-step. The methanol content under the new condition was decreased by 36.1% when compared to the optimal condition for the second-step. In the entire process, the total content of methanol under the recommended conditions was significantly reduced when compared to the optimum conditions. Thus, a 35.6 vol% difference existed in the methanol consumption between the optimum and recommended conditions, which equates to a savings of 3.71 $/h in methanol costs based on 1.06 $/L methanol price [47]. When considering the sulphuric acid requirement, the first-esterification requires 7.0 vol% sulphuric acid content for optimal conditions. By contrast, more than 0.2 vol% of sulphuric acids content must be added to the reaction to achieve satisfactory results owing to the lowered methanol consumption. Moreover, the sulphuric acid required was lowered from the optimal condition of 5.2 vol% to the recommended condition of 3.0 vol% in the second-step of the process to obtain 1.00 wt% FFA content.

3.5. Effect of independent variables on FFA reductions

The effects of five independent variables, methanol content (15–75 vol%), sulphuric acid content (1.5–7.5 vol%), hole diameter (3–7 mm), hole depth (2–10 mm), and rotor speed (1000–5000 rpm), on the first- and second-step continuous FFA reduction processes from SPO via HCR are illustrated in Fig. 4, Fig. 5, respectively.

3.5.1. Effect of influence variables on FFA reductions for first-step

Fig. 4b shows the correlation between the methanol content and hole diameter on the FFA content in the first-step. A less than 40 wt% FFA level was found in methanol consumption ranging from 55 to 73 vol% (4.8–6.4:1 methanol to oil molar ratio) and hole diameter ranging of 4.4 to 5.6 mm. Consequently, significant concentrations of methanol were required to accelerate the equilibrium forward to reach a low FFA level in the first-step of esterification. However, when methanol was used in excess (over 6.4:1 methanol to oil molar ratio), the FFA level increased sharply. Diluting the mixture with an excess amount of methanol reversed the reaction. Binnal et al. (2021) [48] reported that under optimum conditions, a 30:1 methanol-to-FFA molar ratio of 8 wt% sulphuric acid content and 600 W microwave power at 60 °C, the FFA level of dairy scum oil could be reduced from 8.82% to 1.82%. They also reported that a 60:1 M ratio led to a reduction in FFA conversion. This phenomenon may occur when the methanol concentration increases, leading to a decrease in the FFA conversion. Because of this influence of the methanol concentration, the esterification reaction tended to proceed in the reverse direction, causing a low methyl ester content. Consequently, the rate of esterification conversion is reduced by the excess methanol [48].

3.5.2. Effect of influence variables on FFA reductions for second-step

The effect of FFA level on methanol and sulphuric acid concentrations is shown in Fig. 5a. Methanol concentrations of greater than 50 vol% (over 4.5:1 methanol to oil molar ratio) and sulphuric acid concentrations between 3.5 and 7.0 vol% achieved FFA levels below 0.5 wt%. Similar trends were observed with sulphuric acid content when a catalytic dose of sulphuric acid drove the reaction forward. In addition, the esterification reaction rate dropped because methanol boiled out from the exothermic reaction carried out by the excessive use of sulphuric acid. Similar results were reported by Chai et al. (2014) [49], who investigated the FFA reduction process of used vegetable oils. The authors reported an initial FFA content of 5.0 wt% was reduced to less than 0.5 wt% under the following conditions: 40:1 methanol to FFA molar ratio, 10% sulphuric acid, and 55–65 °C reaction temperature. They also stated that the FFA conversion rate increased when the acid catalyst concentration was varied between 5 and 10% and subsequently decreased when the acid catalyst concentration was increased to 15%. Consequently, further addition of sulphuric acid reduced the conversion rate once the maximum conversion rate was reached at a certain sulphuric acid level [49]. Moreover, to minimize the methanol used and eliminate unreacted FFA, heterogeneous catalysts and ion exchange resins are alternative options for the second-step of esterification and purification processes. This type of polymer provides a reusability attribute, excellent thermal stability, and makes the process more environmentally friendly for catalyst recovery and product purification [50]. However, some significant limitations, such as instant interrupted mass transfer, slow reaction rate, and higher catalyst synthesis cost, may limit the use of these microporous ion exchange resins in larger production scales [51].

3.6. Compositions, physical properties, and yields of oils from double-step esterification production

The compositions of FFA, ME, TG, DG, and MG in the oils were verified using a TLC/FID analyzer (Table 6). Under these conditions, 89.16 wt% initial FFA content in SPO was reduced to 36.69 wt% by the first-step, and 0.94 wt% FFA level was obtained in second-esterified oil. The methyl ester purities for the first- and second-processing steps increased to 54.58 and 89.25 wt%, respectively. In terms of the physical properties, the specific gravities at 60 °C were 0.853 and 0.850, the dynamic viscosities at 40 °C were 6.57 and 5.36 cSt, and the AVs were 18.8 and 1.8 mg KOH/g for the first- and second-steps, respectively. A cloud point and pour point tester (model: MPC-102A, Tanaka, Japan) was used to ascertain the solidification temperature. The cloud points for the first- and second-steps were lowered to 15 and 13 °C, respectively, whereas the pour point was reduced from 42 °C to 11 °C and 11 °C for the initial SPO and first- and second-steps, respectively. The first-step esterification yielded 109.8 vol%, second-step esterification yielded 115.6 vol% (no washing), and second-esterified oil yielded 93.9 vol% after the washing method. The yield percentages of the esterified oil from the first- and second-steps, respectively, were obtained within 61 s of residence time, which was calculated based on a 25 L/h flow rate of SPO flowing through the HCRs for both processes. An average product yield of 93.9 vol% esterified oil from the whole process was attained after the washing process. To produce biodiesel with high purity and high product yield, an excess methanol concentration must be considered to increase the forward esterification reaction [54]. Therefore, the residual methanol content was detected in the final products from the first-step (first-esterified oil and generated wastewater phases) and the final products from the second-step (second-esterified oil and wastewater phases) using a headspace-gas chromatograph equipped with a flame ionization detector (model: HS–GC/FID; HP6850 GC, Hewlett Packard, USA). The total unreacted methanol contents in the generated wastewater phases were 50.89 and 62.33 wt% for the first- and second-step processes are necessary to get the recovered methanol that can then be recycled back into the esterification reactions [55]. A similar report was described by Mu et al. (2016) [55], who evaluated the environmental impacts and economic performance of scum-to-biodiesel conversion in wastewater treatment facilities. They concluded that the extra methanol content after the reaction could be recycled for the next production lot. Particularly, an excess methanol content of up to 80% in the lower layer can be recovered after separation using a laboratory-scale rotary evaporator. Therefore, this technique offers an environmentally friendly and economically feasible source of renewable fuels [55]. To increase the distillation capacity of methanol recovery on a large production scale, a flash evaporator [56], a stripping unit [56], a distillation column [57], and a micro-filtered ceramic membrane [58] can be employed for continuous distillation. However, the unreacted methanol contents of 2.44 and 6.64 wt% for the first- and second-esterified oil did not require to recover the methanol in these oils. Because the boiling point of methanol is higher than that of the liquid phase, it is important to avoid the reverse reaction when employing heat in a recovery process that involves changing methanol from a liquid to a vapor. Hence, the residual methanol in esterified oil should not be recovered to prevent the reverse reaction [59]. In the esterified oil after the washing process, the residual methanol and sulphuric acid in the first- and second-esterified oil were eliminated by the washing method, whereas the remaining washed water was removed by applying heat before analyzing by a TLC/FID method. To confirm the residual water and methanol contents in the washed esterified oil, the water content was analyzed using a Karl Fischer Coulometer analyzer (model: 831 KFC, Metrohm, Switzerland) and the methanol content with an HS–GC/FID analyzer based on EN 14110. The results indicate that extremely low water and methanol contents were detected in the washed esterified oil, as shown in Table 6. Hence, the water and methanol contents in this fuel complied with the biodiesel standards and could be utilized in diesel engines. Moreover, the residual sulphuric acid was diluted by washing. Water can eliminate the remaining sulphuric acid and other impurities owing to its high solubility [60]. The residual sulphuric acid content in the second-esterified oil after the washing process was determined using a CHNS/O analyzer [61] (model: Flash 2000 EA, Thermo Scientific, Italy) according to ASTM D4239. The ultimate analysis results indicated that the sulfur content was undetectable. Consequently, no residual sulphuric acid was detected in the esterified oil after washing. Therefore, washing with water can eliminate residual methanol and sulphuric acid in the final product. Hence, this study successfully converted waste from palm oil mill plants of SPO into alternative energy using a unique HC technique. However, we suggest that this outcome product with low FFA content should be continued in the transesterification process to convert the remaining tri- di- and mono-glycerides into high-purity methyl esters using a 3D-printed rotational hydrodynamic cavitation reactor. Nevertheless, when evaluating the cost of whole biodiesel process, the purification procedure is critical to purifying the purified biodiesel before usage in the diesel engines. Therefore, a future research may investigate the different types of wet washing, dry washing, membrane separation, and ion exchange for removing residual catalyst, residual methanol, and residual glycerol in biodiesel after the transesterification process [62].

Table 6.

Compositions, physical properties, yields, and residual methanol of esterified oil from the SPO of each process.

| Parameters | Method | SPO | Esterified oil |

Biodiesel standard |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-step | Second-step | US [52] | Europe [52] | THA [53] | |||

| Compositionsa | |||||||

| Free fatty acid (wt%) | TLC/FID | 89.16 | 36.69 | 0.94 | – | – | – |

| Methyl ester (wt%) | TLC/FID | 0.00 | 54.58 | 89.25 | – | min 96.5 | min 96.5 |

| Triglyceride (wt%) | TLC/FID | 9.80 | 5.60 | 6.93 | max 0.2 | max 0.2 | max 0.2 |

| Diglyceride (wt%) | TLC/FID | 0.80 | 2.56 | 2.57 | – | max 0.2 | max 0.2 |

| Monoglyceride (wt%) | TLC/FID | 0.24 | 0.57 | 0.30 | – | max 0.2 | max 0.7 |

| Physical propertiesb | |||||||

| Specific gravity | ASTM D1298 | 0.865 (at 60 °C) | 0.853 (at 60 °C) | 0.881 (at 15 °C) | 0.86–0.90 (at 15 °C) | 0.86–0.90 (at 15 °C) | 0.86–0.90 (at 15 °C) |

| Dynamic viscosity (cSt) | ASTM D445 | 3.89 (at 60 °C) | 6.57 (at 40 °C) | 5.36 (at 40 °C) | 1.9–6.0 (at 40 °C) | 3.5–5.0 (at 40 °C) | 3.5–5.0 (at 40 °C) |

| Acid value (mg KOH/g) | ASTM D664 | 197.7 | 18.8 | 1.8 | max 0.5 | max 0.5 | max 0.5 |

| Cloud point (°C) | ASTM D2500 | 15 | 13 | – | – | – | |

| Pour point (°C) | ASTM D97 | 42 | 11 | 11 | – | – | – |

| Yieldc | |||||||

| Crude esterified oil (no washing) (vol%) | 109.8 | 115.6 | |||||

| Esterified oil after washing process (vol%) | 94.4 | 93.9 | |||||

| Generated wastewater (vol%) | 62.6 | 43.6 | |||||

| Crude esterified oil | |||||||

| Residual methanol in esterified oil (wt%) | EN 14110 | 2.44 | 6.64 | ||||

| Residual methanol in generated wastewater (wt%) | EN 14110 | 50.89 | 62.33 | ||||

| Washed esterified oil | |||||||

| Residual methanol in washed esterified oil (wt%) | EN 14110 | <0.01 | max 0.2 | max 0.2 | max 0.2 | ||

| Residual water in washed esterified oil (wt%) | EN ISO 12937 | 0.05 | - | - | max 0.05 | ||

Note:

Results of actual experiment analyzed by a TLC/FID method.

Physical properties of esterified oil after washing process.

Yield (vol.%) was calculated by the volume of oil (mL) with respect to the volume of initial SPO (mL), which relates to 100 vol% of initial SPO.

3.7. Electricity consumption

The average electricity consumed by the entire process was examined using a three-phase digital power meter (model: C.A 8220, Chauvin Arnoux, France), as shown in Table 7. Initially, 25 L of SPO was preheated from room temperature (30±2 °C) to melt the semi-solid into the liquid phase using a 1 kW band heater coupled with a 0.030 kW single-phase electric mixer for 30 min. This preparation process consumes 0.453 kWh of electric power. At the start-up step of both esterifications, the mixture of oil was heated to 60 °C. Subsequently, methanol was mixed with the oil using a 0.030 kW circulating pump for 30 min to provide a homogenous phase of oil and methanol at a constant temperature of 60 °C. Consequently, each starting procedure required 0.453 kWh of electric power. Two digital dosing pumps used 0.040 kWh in each reaction step to continuously feed blended oil with methanol and sulphuric acid into the HCR. The three-phase electrical motor's 0.459 kW utilized 0.738 kWh to operate a 3D-printed rotor at a rotational speed of 3000 rpm. A submersible heater and circulating pump were also used to maintain a steady temperature in the mixture tank throughout the procedure. According to the calculations, each esterification procedure required 1.295 kWh of electricity to lower the FFA in SPO over the course of 1 h 37 min. Consequently, the overall energy consumption was 3.95 kWh to generate 28.9 L of second-esterified oil at an initial volume of 25 L of SPO. Therefore, the average energy consumption required for the production of second-esterified oil is 0.137 kWh/L. Moreover, the electricity consumption of the methanol recovery process from the overall generated wastewater was tested using a simple distillation method using a laboratory hotplate (HTS-1003, Labmart, Korea). To distillate recovered methanol at a yield of approximately 70%, average electricity consumption of 0.88 kWh/kg of generated wastewater was required.

Table 7.

Electricity consumption for the whole process.

| Equipment | Electricity consumption (kWh) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-step |

Second-step |

|||

| Start up | Running | Start up | Running | |

| 25 L of SPO was preheated up to 60 °C by a 1 kW band heater for 30 min | 0.438 | – | – | – |

| A 0.030 kW single-phase electrical mixer motor | 0.015 | – | – | – |

| The mixture was heated up to 60 °C by a 1 kW submerge heater for 30 min | 0.438 | 0.470 | 0.438 | 0.470 |

| A 0.030 kW circulating pump | 0.015 | 0.047 | 0.015 | 0.047 |

| Two dosing pumps: oil and H2SO4 | – | 0.040 | – | 0.040 |

| Three-phase electrical motor | – | 0.738 | – | 0.738 |

| Total electricity consumption | 0.906 | 1.295 | 0.453 | 1.295 |

4. Conclusions

A continuous double-step esterification procedure was used in this study to minimize the high initial FFA content in SPO using a 3D-printed rotor and stator-type HCR. To evaluate the reduced quantity of FFAs from both methods, five independent factors were varied: the methanol content, sulphuric acid content, hole diameter, hole depth, and rotor speed. Consequently, the first-step decreased the FFA levels in SPO to 35.00 wt%, while the second-step reduced the residual FFA in the first-esterified oil to less than 1.0 wt%. According to the results of the experiment, the FFA concentration in SPO was reduced from 89.16 wt% to 0.94 wt%, which was effectively close to the predictive models. The products yielded 94.4 and 93.9 vol% washed esterified oil after the first- and second-steps, respectively. For the entire procedure, the average electricity consumption required to eliminate FFA from SPO was 0.137 kWh/L. As a result, using a unique HC technique, this research successfully converted waste from palm oil mill plants of SPO into alternative energy. For further research and development, the second-esterified oil has been focused on producing high purity of methyl ester with a base catalyst transesterification process using a 3D-printed rotational hydrodynamic cavitation reactor. Moreover, the future studies can also test the brake thermal efficiency and brake specific fuel consumption of biodiesel from this process to evaluate the performance and emission of diesel engines at various engine speeds and loads with a dynamometer.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

This research project was supported by the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT): (contract no. N41A650121), the National Science, Research, and Innovation Fund (NSRF) and Prince of Songkla University (Grant No. ENG6405015S), and the National Research Council of Thailand (NRCT), grant no. NRCT5-RSA63022-04.

References

- 1.Noor C.W.M., Noor M.M., Mamat R. Biodiesel as alternative fuel for marine diesel engine applications: a review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2018;94:127–142. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.05.031. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathew G.M., Raina D., Narisetty V., Kumar V., Saran S., Pugazhendi A., Sindhu R., Pandey A., Binod P. Recent advances in biodiesel production: challenges and solutions. Sci. Total Environ. 2021;794:148751. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2021.148751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tamilselvan P., Nallusamy N., Rajkumar S. A comprehensive review on performance, combustion and emission characteristics of biodiesel fuelled diesel engines. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2017;79:1134–1159. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rezania S., Oryani B., Park J., Hashemi B., Yadav K.K., Kwon E.E., Hur J., Cho J. Review on transesterification of non-edible sources for biodiesel production with a focus on economic aspects, fuel properties and by-product applications. Energy Conv. Manag. 2019;201 doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2019.112155. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Syafiuddin A., Chong J.H., Yuniarto A., Hadibarata T. The current scenario and challenges of biodiesel production in Asian countries: a review. Bioresource Technology Reports. 2020;12 doi: 10.1016/j.biteb.2020.100608. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Embong N.H., Hindryawati N., Bhuyar P., Govindan N., Rahim M.H. Ab., Maniam G.P. Enhanced biodiesel production via esterification of palm fatty acid distillate (PFAD) using rice husk ash (NiSO4)/SiO2 catalyst. Appl. Nanosci. 2023;13:2241–2249. doi: 10.1007/s13204-021-01922-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Skrbic B., Predojevic Z., Durisic-Mladenovic N. Esterification of sludge palm oil as a pretreatment step for biodiesel production. Waste Management and Research. 2015;33:723–729. doi: 10.1177/0734242X15587546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Juera-Ong P., Pongraktham K., Oo Y.M., Somnuk K. Reduction in free fatty acid concentration in sludge palm oil using heterogeneous and homogeneous catalysis: process optimization, and reusable heterogeneous catalysts. Catalysts. 2022;12:1007. doi: 10.3390/catal12091007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yacob S., Shirai Y., Hassan M.A., Wakisaka M., Subash S. Start-up operation of semi-commercial closed anaerobic digester for palm oil mill effluent treatment. Process Biochem. 2006;41:962–964. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2005.10.021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yejian Z., Li Y., Xiangli Q., Lina C., Xiangjun N., Zhijian M., Zhenjia Z. Integration of biological method and membrane technology in treating palm oil mill effluent. J. Environ. Sci. 2008;20:558–564. doi: 10.1016/S1001-0742(08)62094-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahmed Y., Yaakob Z., Akhtar P., Sopian K. Production of biogas and performance evaluation of existing treatment processes in palm oil mill effluent (POME) Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2015;42:1260–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.073. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muanruksa P., Winterburn J., Kaewkannetra P. A novel process for biodiesel production from sludge palm oil. MethodsX. 2019;6:2838–2844. doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2019.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wongfaed N., Kongjan P., Prasertsan P., O-Thong S. Effect of oil and derivative in palm oil mill effluent on the process imbalance of biogas production. J. Clean Prod. 2020;247:119110. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2019.119110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Aziz M.M.A., Kassim K.A., ElSergany M., Anuar S., Jorat M.E., Yaacob H., Ahsan A., Imteaz M.A., PhD A. Recent advances on palm oil mill effluent (POME) pretreatment and anaerobic reactor for sustainable biogas production. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2020;119 doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2019.109603. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Urrutia C., Sangaletti-Gerhard N., Cea M., Suazo A., Aliberti A., Navia R. Two step esterification–transesterification process of wet greasy sewage sludge for biodiesel production. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;200:1044–1049. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.10.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayyan A., Alam M.Z., Mirghani M.E.S., Kabbashi N.A., Hakimi N.I.N.M., Siran Y.M., Tahiruddin S. Reduction of high content of free fatty acid in sludge palm oil via acid catalyst for biodiesel production. Fuel Process. Technol. 2011;92:920–924. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.12.011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juera-ong P., Oo Y.M., Somnuk K. Free fatty acid reduction of palm oil mill effluent (POME) using heterogeneous acid catalyst for esterification. Materials Science Forum. 2022;1053:170–175. doi: 10.4028/p-35y201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alvarez-Mateos P., Garcia-Martin J.F., Guerrero-Vacas F.J., Naranjo-Calderon C., Barrios-Sanchez C.C., Perez-Camino M.C. Valorization of a high-acidity residual oil generated in the waste cooking oils recycling industries. Grasas y Aceites. 2019;70:e335. doi: 10.3989/gya.1179182. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chongkhong S., Tongurai C., Chetpattananondh P. Continuous esterification for biodiesel production from palm fatty acid distillate using economical process. Renew. Energy. 2009;34:1059–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2008.07.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Somnuk K., Soysuwan N., Prateepchaikul G. Continuous process for biodiesel production from palm fatty acid distillate (PFAD) using helical static mixers as reactors. Renew. Energy. 2019;131:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2018.07.039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Somnuk K., Prasit T., Prateepchaikul G. Effects of mixing technologies on continuous methyl ester production: Comparison of using plug flow, static mixer, and ultrasound clamp. Energy Conv. Manag. 2017;140:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2017.02.066. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mohadesi M., Gouran A., Dehnavi A.D. Biodiesel production using low cost material as high effective catalyst in a microreactor. Energy. 2021;219 doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.119671. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tabatabaei M., Aghbashlo M., Dehhaghi M., Panahi H.K.S., Mollahosseini A., Hosseini M., Soufiyan M.M. Reactor technologies for biodiesel production and processing: A review. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2019;74:239–303. doi: 10.1016/j.pecs.2019.06.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Samani B.H., Behruzian M., Najafi G., Fayyazi E., Ghobadian B., Behruzian A., Mofijur M., Mazlan M., Yue J. The rotor-stator type hydrodynamic cavitation reactor approach for enhanced biodiesel fuel production. Fuel. 2021;283 doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.118821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saharan V.K., Rizwani M.A., Malani A.A., Pandit A.B. Effect of geometry of hydrodynamically cavitating device on degradation of orange-G. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2013;20:345–353. doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2012.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun X., Chen S., Liu J., Zhao S., Yoon J.Y. Hydrodynamic cavitation: a promising technology for industrial-scale synthesis of nanomaterials. Front. Chem. 2020;8:259. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2020.00259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson A., Ranade V.V. Modeling hydrodynamic cavitation in venturi: influence of venturi configuration on inception and extent of cavitation. AICHE J. 2019;65:421–433. doi: 10.1002/aic.16411. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang B., Su H., Zhang B. Hydrodynamic cavitation as a promising route for wastewater treatment – a review. Chem. Eng. J. 2021;412 doi: 10.1016/j.cej.2021.128685. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mane M.B., Bhandari V.M., Balapure K., Ranade V.V. A novel hybrid cavitation process for enhancing and altering rate of disinfection by use of natural oils derived from plants. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2020;61 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2019.104820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Garuti M., Langone M., Fabbri C., Piccinini S. Monitoring of full-scale hydrodynamic cavitation pretreatment in agricultural biogas plant. Bioresour. Technol. 2018;247:599–609. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.09.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Carpenter J., George S., Saharan V.K. Low pressure hydrodynamic cavitating device for producing highly stable oil in water emulsion: effect of geometry and cavitation number. Chem. Eng. Process. 2017;116:97–104. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2017.02.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katariya P., Arya S.S., Pandit A.B. Novel, non-thermal hydrodynamic cavitation of orange juice: effects on physical properties and stability of bioactive compounds. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020;62 doi: 10.1016/j.ifset.2020.102364. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Suryawanshi P.G., Bhandari V.M., Sorokhaibam L.G., Ruparelia J.P., Ranade V.V. Solvent degradation studies using hydrodynamic cavitation. Environ. Prog. Sustain, Energy. 2018;37:295–304. doi: 10.1002/ep.12674. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun X., Xuan X., Song Y., Jia X., Ji L., Zhao S., Yoon J.Y., Chen S., Liu J., Wang G. Experimental and numerical studies on the cavitation in an advanced rotational hydrodynamic cavitation reactor for water treatment. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021;70 doi: 10.1016/j.ultsonch.2020.105311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chuah L.F., Klemes J.J., Yusup S., Bokhari A., Akbar M.M., Chong Z.K. Kinetic studies on waste cooking oil into biodiesel via hydrodynamic cavitation. J. Clean Prod. 2017;146:47–56. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.06.187. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chitsaz H., Omidkhah M., Ghobadian B., Ardjmand M. Optimization of hydrodynamic cavitation process of biodiesel production by response surface methodology. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2018;6:2262–2268. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2018.02.047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gole V.L., Naveen K.R., Gogate P.R. Hydrodynamic cavitation as an efficient approach for intensification of synthesis of methyl esters from sustainable feedstock. Chem. Eng. Process. 2013;71:70–76. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2012.10.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bokhari A., Chuah L.F., Yusup S., Klemes J.J., Kamil R.N.M. Optimisation on pretreatment of rubber seed (Hevea brasiliensis) oil via esterification reaction in a hydrodynamic cavitation reactor. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;199:414–422. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mongkolbovornkij P., Champreda V., Sutthisripok W., Laosiripojana N. Esterification of industrial-grade palm fatty acid distillate over modified ZrO2 (with WO3–, SO4 –and TiO2–): Effects of co-solvent adding and water removal. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010;91:1510–1516. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2010.05.030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kanjaikaew U., Tongurai C., Chongkhong S., Prasertsit K. Two-step esterification of palm fatty acid distillate in ethyl ester production: optimization and sensitivity analysis. Renew. Energy. 2018;119:336–344. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.12.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Elgharbawy A.S., Sadik W.A., Sadek O.M., Kasaby M.A. Maximizing biodiesel production from high free fatty acids feedstocks through glycerolysis treatment. Biomass Bioenerg. 2021;146 doi: 10.1016/j.biombioe.2021.105997. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gumahin A.C., Galamiton J.M., Allerite M.J., Valmorida R.S., Laranang J.L., Mabayo V.I.F., Arazo R.O., Ido A.L. Response surface optimization of biodiesel yield from pre-treated waste oil of rendered pork from a food processing industry. Bioresour. Bioprocess. 2019;6:48. doi: 10.1186/s40643-019-0284-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Simsek S., Uslu S. Determination of a diesel engine operating parameters powered with canola, safflower and waste vegetable oil based biodiesel combination using response surface methodology (RSM) Fuel. 2020;270 doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2020.117496. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kostic M.D., Velickovic A.V., Jokovic N.M., Stamenkovic O.S., Veljkovic V.B. Optimization and kinetic modeling of esterification of the oil obtained from waste plum stones as a pretreatment step in biodiesel production. Waste Manage. 2016;48:619–629. doi: 10.1016/j.wasman.2015.11.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mohamad M., Ngadi N., Wong S.L., Jusoh M., Yahya N.Y. Prediction of biodiesel yield during transesterification process using response surface methodology. Fuel. 2017;190:104–112. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2016.10.123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yadav A.K., Vinay, Singh B. Optimization of biodiesel production from Annona squamosa seed oil using response surface methodology and its characterization. Energy Sources Part A-Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2018;40:1051–1059. doi: 10.1080/15567036.2018.1468516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chemipan Corporation, Methanol. https://www.chemipan.com/a/en-gb/279-product/389-general-chemicals/5596-methanol-160kg-200.html, 2023 (accessed 5 January 2023).

- 48.Binnal P., Amruth A., Basawaraj M.P., Chethan T.S., Murthy K.R.S., Rajashekhara S. Microwave-assisted esterification and transesterification of dairy scum oil for biodiesel production: kinetics and optimisation studies, Indian. Chem. Eng. 2021;63:374–386. doi: 10.1080/00194506.2020.1748124. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chai M., Tu Q., Lu M., Yang Y.J. Esterification pretreatment of free fatty acid in biodiesel production, from laboratory to industry. Fuel Process. Technol. 2014;125:106–113. doi: 10.1016/j.fuproc.2014.03.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jenie S.N.A., Kristiani A., Sudiyarmanto, Khaerudini D.S., Takeishi K. Sulfonated magnetic nanobiochar as heterogeneous acid catalyst for esterification reaction. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020;8:103912. doi: 10.1016/j.jece.2020.103912. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soltani S., Rashid U., Al-Resayes S.I., Nehdi I.A. Recent progress in synthesis and surface functionalization of mesoporous acidic heterogeneous catalysts for esterification of free fatty acid feedstocks: a review. Energy Conv. Manag. 2017;141:183–205. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2016.07.042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sajjadi B., Raman A.A.A., Arandiyan H. A comprehensive review on properties of edible and non-edible vegetable oil-based biodiesel: composition, specifications and prediction models. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2016;63:62–92. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.05.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Department of Energy Business, Ministry of Energy, Characteristics and quality of fatty acid methyl ester biodiesel. http://elaw.doeb.go.th/document_doeb/TH/690TH_0001.pdf, 2019 (accessed 6 January 2023).

- 54.Khoobbakht G., Kheiralipour K., Rasouli H., Rafiee M., Hadipour M., Karimi M. Experimental exergy analysis of transesterification in biodiesel production. Energy. 2020;196:117092. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2020.117092. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mu D., Addy M., Anderson E., Chen P., Ruan R. A life cycle assessment and economic analysis of the scum-to-biodiesel technology in wastewater treatment plants. Bioresour. Technol. 2016;204:89–97. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2015.12.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Philip F.A., Veawab A., Aroonwilas A. Simulation analysis of energy performance of distillation-, stripping-, and flash-based methanol recovery units for biodiesel production. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014;53:12770–12782. doi: 10.1021/ie5003476. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Chabukswar D.D., Heer P.K.K.S., Gaikar V.G. Esterification of palm fatty acid distillate using heterogeneous sulfonated microcrystalline cellulose catalyst and its comparison with H2SO4 catalyzed reaction. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2013;52:7316–7326. doi: 10.1021/ie303089u. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang W., Na S., Li W., Xing W. Kinetic modeling of pervaporation aided esterification of propionic acid and ethanol using T-type zeolite membrane. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2015;54:4940–4946. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.5b00505. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Photaworn S., Tongurai C., Kungsanunt S. Process development of two-step esterification plus catalyst solution recycling on waste vegetable oil possessing high free fatty acid. Chem. Eng. Process. 2017;118:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cep.2017.04.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pena E.H., Medina A.R., Callejon M.J.J., Sanchez M.D.M., Cerdan L.E., Moreno P.A.G., Grima E.M. Extraction of free fatty acids from wet Nannochloropsis gaditana biomass for biodiesel production. Renew. Energy. 2015;75:366–373. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2014.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rahman Q.M., Zhang Bo., Wang L., Shahbazi A. A combined pretreatment, fermentation and ethanol-assisted liquefaction process for production of biofuel from Chlorella sp. Fuel. 2019;257:116026. doi: 10.1016/j.fuel.2019.116026. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 62.García Martín J.F., Torres García M., Álvarez Mateos P. Special issue on “Biodiesel production processes and technology”. Processes. 2023;11:25. doi: 10.3390/pr11010025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]