Abstract

The posterior circumflex humeral artery, a branch of the axillary artery, is compressed by the humeral head during repeated abduction and external rotation of the shoulder joint owing to its anatomical structure. This damages the vascular endothelium, resulting in thrombi, arterial dissection, and aneurysms, a condition known as posterior, circumflex humeral artery pathological lesions. A thrombus may form at the site and becomes a peripheral embolus, resulting in peripheral arterial occlusion.A 21-year-old right-handed elite man college volleyball player noticed coldness and pain in his right hand during a game. Cyanosis was present except in the middle finger, and the beating radial artery was palpable; however, the ulnar artery was not. Doppler ultrasound examination revealed thrombus occlusion of the ulnar artery and common palmar artery of the index finger. Peripheral arterial occlusion was diagnosed due to embolization of a thrombus from this site. The patient stopped practicing volleyball immediately after the onset of symptoms and was started on cilostazol 200 mg and rivaroxaban 15 mg. Subjective coldness of the fingers improved one week after the start of treatment. The patient resumed practice four weeks after the start of treatment and participated in a game by the seventh week.Posterior circumflex humeral artery pathological lesions are caused by overhead motions such as pitching. They are most commonly reported in athletes playing volleyball, although rare, and many cases of aneurysm formation have been reported.Observing a cold sensation in the periphery after practice is necessary for screening.

Keywords: Posterior circumflex humeral artery pathological lesions, Quadrilateral space syndrome, Vascular compression syndrome, Volleyball

1. Background

The axillary artery is compressed by the humeral head owing to abduction and external rotation of the shoulder joint caused by overhead motion, as typified by pitching. Repeated overhead motion can cause microdamage to the endothelium, resulting in thrombus and aneurysm formation in severe cases.1,2 Spiking and serving in volleyball are also overhead motions,3 and similar to baseball pitchers, the risk of thrombus is high.4 In this study, we report a case of peripheral arterial thrombosis secondary to a thrombus in a branch of the axillary artery.

2. Case report

A 21-year-old right-handed man elite collegiate volleyball player had been playing volleyball for 12 years as a spiker (187 cm, 80 kg). No previous medical or family history was noted, and he had never smoked. His chief complaints were coldness, numbness, and pain in the right fingers, except for the middle finger, fatigue in the right shoulder and ulnar side of the forearm, and right scapular pain. He was aware of pain in the right scapula and right shoulder whenever he became fatigued. The patient was aware of heaviness in his right shoulder after practice on that day. The chief complaint recurred three days later during a game, coldness and pallor of the fingers, except for the middle finger, were observed and after the game. The patient improved with rest and local warming and was examined for the first time the next day.

Coldness and pallor were observed on the right fingers at the time of the initial consultation. All fingers, except for the middle finger, were cold on palpation, and the nails, except for the middle finger, showed cyanosis-like purple color changes in particular (Fig. 1). The nails changed to dark purple with a cold environment and hand drooping exacerbated by the position of the arm, depending on gravity. The radial artery was palpable; however, the ulnar artery was not palpable. Wright, Roos, and Eden tests revealed negative results, whereas the Allen test revealed a positive result in the right ulnar artery. Atrophy of the right infraspinatus muscle was observed. Tenderness was observed in the lateral acromion, distal scapular spine, and quadrilateral space. Signs of subacromial impingement were positive on the right side. Muscle strength of the deltoid was normal. No abnormal shoulder and scapular sensations were observed. Blood pressure was 130/65 mmHg in the right upper extremity and 133/62 mmHg in the left upper extremity with an ankle brachial index of 1.18 in the right and 1.17 in the left. Blood counts showed hemoglobin of 15.4 g/dl and platelet of 232 × 1000/μl, which were within the reference range. Prothrombin time, antithrombin activity, fibrinogen degradation Protein C activity C, and protein S antigenic content were 10.9 s, 111.7%, ≥151%, and 85%, respectively, and normal values were observed (3-ANCA <1.0 U/ml, MPO-ANCA <1.0 U/ml, anticardiolipin IgG antibody 5.2 U/ml, and lupus anticoagulant 0.9).

Fig. 1.

Dorsal surfaces of both hands at initial examination. The fingers of the right hand are pale, and the nails of the index, ring, and little fingers (circled) show cyanosis-like color changes. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the Web version of this article.)

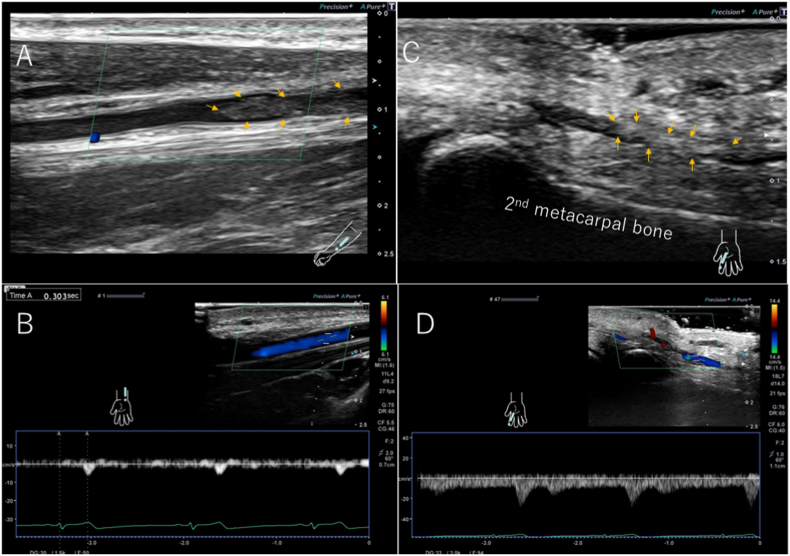

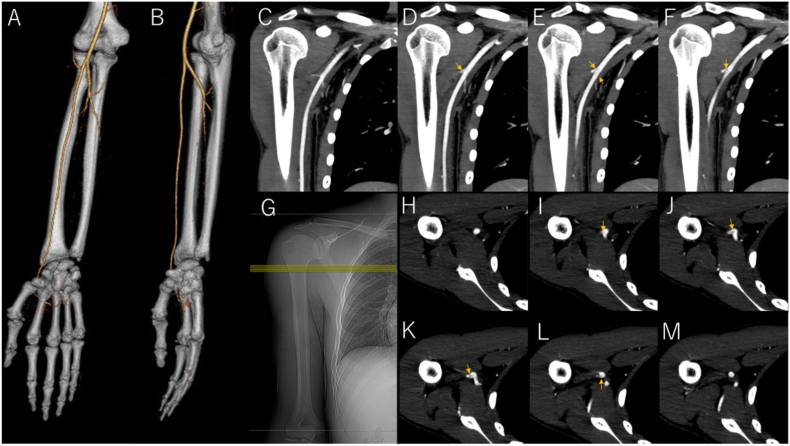

Ultrasonographic evaluation of the forearm arteries revealed thrombus occlusion in the distal ulnar artery (peripheral to the mid-forearm), extending to 38 mm (Fig. 2A). Blood flow distal to the occluded ulnar artery was retrograde (Fig. 2B). The common palmar finger artery branching from the palmar artery arch showed no blood flow, a finding suggestive of thrombus occlusion (Fig. 2C and D). Contrast-enhanced CT showed that the ulnar artery was interrupted in the middle of the forearm (Fig. 3A and B). In the upper arm, a thrombus was observed in the posterior circumflex humeral artery (PCHA), a branch of the axillary artery (Fig. 3C–M). No aneurysm or enlargement of vasculature was observed. A diagnosis of thrombo-occlusive disease of the ulnar artery and common palmar finger artery secondary to thrombosis of the PCHA was made. As peripheral blood flow was maintained by blood flow from the palmar artery arch, and the symptoms improved with rest and warmth, we decided to stop volleyball completely and started him on oral medication. Cilostazol 200 mg and rivaroxaban 15 mg were administered. The subjective coldness of the fingers improved one week after the start of the treatment. The cold sensation in the right hand improved, and the pain almost disappeared four weeks after the start of the treatment. Ulnar artery pulsation became palpable, although weak. Follow-up echocardiography showed that the thrombus in the common palmar digital artery of the index finger had disappeared. The thrombus in the ulnar artery remained; however, ultrasonography revealed blood flow around the thrombus, and the size of the thrombus shrank and tended to regress. Thereafter, the patient started light exercises, such as throwing a ball. No further worsening of symptoms was noted, and high-intensity exercises, such as spiking and serving, were resumed in stages from the fifth week after the start of treatment. The patient was able to participate in the official games by the seventh week after the start of treatment. Thereafter, he returned to his original level of activity without symptom flare-ups. A follow-up ultrasonography nine weeks after the start of treatment showed further regression, although the thrombus in the ulnar artery remained (Fig. 4). Magnetic resonance angiography, performed to evaluate the thrombus in the axillary artery, showed that the proximal thrombus had disappeared. Symptoms and imaging were improving, but the thrombus had not completely resolved on the final ultrasound examination. Therefore, the patient was scheduled to undergo another examination 6 months after the onset of the disease, and the medication was to be discontinued gradually.

Fig. 2.

Ultrasonography of the forearm at initial examination. Ulnar artery (A, B) and common palmar finger artery (C, D). Thrombus (arrow) in ulnar artery (A) and common palmar finger artery (C).

Fig. 3.

Computed tomography angiography of the right upper extremity. 3D images of the forearm (A, B) show disruption of the ulnar artery. Coronal section images (C–F) of the proximal upper arm (arrows indicate thrombus with low-intensity). Scout image (G). Axial images (H–M) of the proximal upper arm (arrows indicate thrombus with low luminosity).

Fig. 4.

Ultrasonography of the forearm at follow-up examination. Ulnar artery (A, B) and common palmar finger artery (C). The ulnar artery was fully opened although a mural thrombus (arrow) remained. The finger artery showed resumed blood flow by Doppler technique.

3. Discussion

Wright proposed the “hyper-abduction syndrome,” in which the second branch of the axillary artery is occluded by external pressure on the pectoralis minor muscle during overhead motion, and established the Wright test as a technique.5 Lord et al. were the first to recognize that the humeral head compresses the axillary artery.6 Dijkstra et al. demonstrated angiographically that compression of the humeral head by 100° of abduction caused angiographic occlusion of the apparently normal axillary artery.7 McCarthy et al. showed that the axillary artery, especially the PCHA, was occluded by the humeral head.8 Rohrer et al. demonstrated the role of the humeral head in axillary artery compression and injury in throwing athletes.9 Cahill et al. critically reviewed the results of thoracic outlet syndrome10 surgery and found that many failed cases involved posterior humeral rotation in abduction and external rotation.11 This led to a series of investigative studies and the term “quadrilateral space syndrome”. The quadrilateral space is the space between the surgical neck of the humerus, long head of the triceps, greater trochanter, and lesser trochanter through which the axillary nerve and posterior circumflex humeral artery and vein pass.

Repetitive abduction and external rotation cause damage to the endothelium of the blood vessels, resulting in the formation of thrombi. Dissection of the arterial wall can also lead to the formation of an aneurysm, which can become a breeding ground for thrombi and cause embolisation of the peripheral arteries. The pathological conditions that cause dissection, aneurysm, and thrombus in PCHA by these mechanisms are collectively described here as PCHA pathological lesions. The resulting compression syndrome of the PCHA is a rare vascular compression syndrome and is a differential diagnosis between thoracic outlet syndrome and hypothenar hammer syndrome.12 In the early stages, patients may complain of shoulder and scapular laxity and pain, which should also be differentiated from shoulder joint and cervical spine diseases.

In a 2019 systematic review by Kuntz et al. PCHA pathological lesions resulting from overhead sports activities were most frequently seen in individuals who play volleyball with 35 (72%) of 49 cases, followed by those who play baseball with nine (18%).4 In a systematic review by Kraan et al., 41 (61%) of 67 cases were seen in individuals who play volleyball, followed by those who play baseball with 13 (19%).13 van de Pol et al. reported symptoms of finger artery thrombosis with PCHA pathological lesions (during practice or competition) in 99 elite Dutch volleyball players. The prevalence of thrombosis was estimated to range from 11% to 27% based on a combination of questionnaires and other factors.14 They also investigated risk factors in 278 elite Dutch volleyball and beach volleyball players with a questionnaire on finger ischemia. Risk factors for PCHA pathological lesions were more than 17 years of experience (9-fold) and more than 27 years of age (14-fold).15 Overhead spike and serve in volleyball may be owing to the changing of the point of impact depending on the position of the pass in the overhead motion of spiking and serving in volleyball compared with the throwing motion in baseball. Backward impact forces external rotation, which is thought to increase the likelihood of disease onset in particular.

We found 19 cases of volleyball-related PCHA pathological lesions in English literature (Table 1).1,4,16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 All had symptoms in the dominant hand, although not listed in the table. The mean age was 24.1 years old (17–35), and six patients were females. The sports level was generally high, with 15 professional athletes as patients. The symptoms included ischemia of the peripheral fingers in 18 patients. The initial diagnostic methods used were angiography, computed tomography angiography, magnetic resonance angiography, and Doppler ultrasound. PCHA pathological lesions included aneurysms in 14 cases and thromboses in four cases. Ligation or embolisation was performed in 12 of the 14 cases of aneurysm formation. The two conservatively treated cases were veterans aged 34 and 35 years, and may have been conservatively treated considering their age. One patient, treated conservatively for thrombosis, did not continue playing volleyball. In our case, the only lesion in the PCHA was a thrombus, which was treated conservatively with oral medications with good results. When an aneurysm is present, the abduction external rotation motion causes the humeral head to squeeze the aneurysm and thrombus in the vessel, similar to a tube of toothpaste, pushing the thrombus out of the aneurysmal arterial branch into the axillary artery and causing emboli in the forearm, hand, and finger circulation.14 This often requires invasive surgery, as described above. Therefore, it is necessary to treat aneurysms before they form.

Table 1.

Posterior circumflex humeral artery pathological lesions in volleyball players.

| Age | Gender | Sports level | Symptoms | Imaging technique | Proximal lesion | Treatment | Adjunctive procedures | Outcome | Author | Published year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 23 | Male | Professional | Arm ischemia | Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | None | Returned to competition | Reekers JA | 1993 |

| 25 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Aneurysm | Embolisation(coil) | None | Returned to competition | ||

| 35 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Aneurysm | Conservative | None | Returned to competition | ||

| 19 | Male | Collegiate | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection with revascularisation | None | Returned to competition | Gelabert HA | 1997 |

| 17 | Male | Competitive | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Thrombosis | Conservative | None | Discontinued to play | Ikezawa T | 2000 |

| 19 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | Doppler, Angiography | Aneurysm | Embolisation(coil), Surgical embolectomy | None | Returned to competition | Vlychou M | 2001 |

| 24 | Female | Professional | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | Fibrinolytics | Returned to competition | Macintosh A | 2006 |

| 25 | Female | Professional | Digital ischemia | Angiography, per-operative DUS | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | None | Returned to competition | ||

| 32 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | DUS, Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | Aspirin 100 mg for 6 months | Returned to competition | Atema JJ | 2012 |

| 22 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | DUS, Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | Aspirin 100 mg for 6 months | Returned to competition | ||

| 29 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | DUS, Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | Aspirin 100 mg for 18 months | Returned to competition | ||

| 20 | Female | Collegiate | Digital ischemia | CTA | Thrombosis | Resection without revascularisation | None | Returned to competition | Brown SA | 2015 |

| 24 | Female | Professional | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection without revascularisation | Aspirin 325 mg for 12 months | Returned to competition | ||

| 26 | Female | Professional | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Thrombosis | Resection with revascularisation | None | Returned to competition | ||

| 20 | Female | Professional | Digital ischemia | MRA | Aneurysm | Embolisation(coil) | Anticoaguration | Returned to competition | Tao M | 2016 |

| 34 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | DUS, MRA | Aneurysm | Conservative | None | Returned to competition | Van De Pol | 2017 |

| 19 | Male | Competitive | Digital ischemia | DUS, CTA, Angiography | Thrombosis | Surgical thrombectomy | Rivaroxaban for 3 months | Returned to competition | Rollo J | 2017 |

| 17 | Male | Competitive | Digital ischemia | Angiography | Dissection | Surgical division | None | Returned to competition | ||

| 28 | Male | Professional | Digital ischemia | DUS, Angiography | Aneurysm | Resection with revascularisation | None | Returned to competition | Kuntz S | 2019 |

DUS: Doppler ultrasound examination, CTA: computed tomography angiography, MRA: magnetic resonance angiography.

Doppler ultrasound examination was useful in this case. It was also able to diagnose a thrombus in the finger artery, which could be used as a follow-up for drug therapy.

The PCHA pathological lesions in this case are rare; however, they are common in volleyball players, and screening with a simple questionnaire, such as the one used by van de Pol et al. is recommended.15 The lesions may be treated conservatively if they do not lead to aneurysms suggesting the importance of early detection, which has also been highlighted.

There is no consensus at all regarding the drugs used for conservative treatment. Table 1 shows that some previous reports have used aspirin, but there is no uniformity regarding its use. In this case, we consulted a cardiologist specializing in peripheral vascular disease, who recommended the use of cilostazol and rivaroxaban, as described above. We hope that new insights will emerge in the future.

References

- 1.Brown S.A., Doolittle D.A., Bohanon C.J., et al. Quadrilateral space syndrome: the Mayo Clinic experience with a new classification system and case series. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90:382–394. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2014.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Duwayri Y.M., Emery V.B., Driskill M.R., et al. Positional compression of the axillary artery causing upper extremity thrombosis and embolism in the elite overhead throwing athlete. J Vasc Surg. 2011;53:1329–1340. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2010.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reeser J.C., Fleisig G.S., Bolt B., Ruan M. Upper limb biomechanics during the volleyball serve and spike. Sports Health. 2010;2:368–374. doi: 10.1177/1941738110374624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kuntz S., Lejay A., Meteyer V., et al. Posterior circumflex humeral artery aneurysm: case report and systematic literature review. EJVES Short Rep. 2019;44:23–28. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvssr.2019.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wright I.S. The neurovascular syndrome produced by hyperabduction of the arms. Am Heart J. 1945;29:1–19. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lord J.W., Rosati L.M. Neurovascular compression syndromes of the upper extremity. Clin Symposia (Summit, N.J. : 1957) 1958;10:35–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dijkstra P.F., Westra D. Angiographic features of compression of the axillary artery by the musculus pectoralis minor and the head of the humerus in the thoracic outlet compression syndrome. Case report. Radiol Clin. 1978;47:423–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McCarthy W.J., Yao J.S., Schafer M.F., et al. Upper extremity arterial injury in athletes. J Vasc Surg. 1989;9:317–327. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rohrer M.J., Cardullo P.A., Pappas A.M., Phillips D.A., Wheeler H.B. Axillary artery compression and thrombosis in throwing athletes. J Vasc Surg. 1990;11:761–768. ; discussion 768-769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peet R.M., Henriksen J.D., Anderson T.P., Martin G.M. Thoracic-outlet syndrome: evaluation of a therapeutic exercise program. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1956;31:281–287. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cahill B.R., Palmer R.E. Quadrilateral space syndrome. J Hand Surg. 1983;8:65–69. doi: 10.1016/s0363-5023(83)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Conn J., Jr., Bergan J.J., Bell J.L. Hand ischemia: hypothenar hammer syndrome. Proc Inst Med Chicago. 1970;28:83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kraan R.B., Beers L., van de Pol D., Daams J.G., Maas M., Kuijer P.P. A systematic review on posterior circumflex humeral artery pathology: sports and professions at risk and associated risk factors. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 2019;59:1058–1067. doi: 10.23736/S0022-4707.18.08579-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van de Pol D., Kuijer P.P., Langenhorst T., Maas M. High prevalence of self-reported symptoms of digital ischemia in elite male volleyball players in The Netherlands: a cross-sectional national survey. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:2296–2302. doi: 10.1177/0363546512456973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.van de Pol D., Kuijer P., Terpstra A., et al. Posterior circumflex humeral artery pathology and digital ischemia in elite volleyball: symptoms, risk factors & suggestions for clinical management. J Sci Med Sport. 2018;21:1032–1037. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atema J.J., Unlü C., Reekers J.A., Idu M.M. Posterior circumflex humeral artery injury with distal embolisation in professional volleyball players: a discussion of three cases. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg : Off J Europ Soc Vasc Surg. 2012;44:195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ejvs.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gelabert H.A., Machleder H.I. Diagnosis and management of arterial compression at the thoracic outlet. Ann Vasc Surg. 1997;11:359–366. doi: 10.1007/s100169900061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ikezawa T., Iwatsuka Y., Asano M., Kimura A., Sasamoto A., Ono Y. Upper extremity ischemia in athletes: embolism from the injured posterior circumflex humeral artery. Int J Angiol. 2000;9:138–140. [Google Scholar]

- 19.McIntosh A., Hassan I., Cherry K., Dahm D. Posterior circumflex humeral artery aneurysm in 2 professional volleyball players. Am J Orthoped. 2006;35:33–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reekers J.A., den Hartog B.M., Kuyper C.F., Kromhout J.G., Peeters F.L. Traumatic aneurysm of the posterior circumflex humeral artery: a volleyball player's disease? J Vasc Intervent Radiol : JVIR. 1993;4:405–408. doi: 10.1016/s1051-0443(93)71888-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rollo J., Rigberg D., Gelabert H. Vascular quadrilateral space syndrome in 3 overhead throwing athletes: an underdiagnosed cause of digital ischemia. Ann Vasc Surg. 2017;42:63.e61–63.e66. doi: 10.1016/j.avsg.2016.10.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tao M., Eisenberg N., Jaskolka J., Roche-Nagle G. Coil embolization of a posterior circumflex humeral aneurysm in a volleyball player. VASA. Zeitschrift fur Gefasskrankheiten. 2016;45:67–70. doi: 10.1024/0301-1526/a000498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.van de Pol D., Maas M., Terpstra A., et al. Ultrasound assessment of the posterior circumflex humeral artery in elite volleyball players: aneurysm prevalence, anatomy, branching pattern and vessel characteristics. Eur Radiol. 2017;27:889–898. doi: 10.1007/s00330-016-4401-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vlychou M., Spanomichos G., Chatziioannou A., Georganas M., Zavras G.M. Embolisation of a traumatic aneurysm of the posterior circumflex humeral artery in a volleyball player. Br J Sports Med. 2001;35:136–137. doi: 10.1136/bjsm.35.2.136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]