Abstract

Due to its rising prevalence, which parallels that of ultraprocessed food (UPF) consumption, inadequate micronutrient intake in childhood is a public health concern. This study aimed to evaluate the association between UPF consumption and inadequate intake of 20 micronutrients in a sample of children from the Mediterranean area. Cross-sectional information from participants in the “Seguimiento del Niño para un Desarrollo Óptimo” (SENDO) project 2015–2021 was used. Dietary information was gathered with a previously validated 147-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire and the NOVA system was used to classify food items. Children were classified by tertiles of energy intake from UPF. Twenty micronutrients were evaluated, and inadequate intake was defined using the estimated average requirement as a cutoff. Crude and multivariable adjusted OR (95% CI) for the inadequacy of ≥ 3 micronutrients associated with UPF consumption were calculated fitting hierarchical models to take into account intra-cluster correlation between siblings. Analyses were adjusted for individual and family confounders. This study included 806 participants (51% boys) with a mean age of 5 years old (SD: 0.90) and an average energy intake from UPF of 37.64% (SD: 9.59). An inverse association between UPF consumption and the intake of 15 out of the 20 micronutrients evaluated was found (p < 0.01). After the adjustment for individual and family confounders, compared with children in the first tertile of UPF consumption, those in the third tertile showed higher odds of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients (OR 2.57; 95%CI [1.51–4.40]).

Conclusion: High UPF consumption is associated with increased odds of inadequate intake of micronutrients in childhood.

|

What is Known: • Micronutrient deficiency is among the 20 most important risk factors for disease and affect around two billion people worldwide. • UPF are rich in total fat, carbohydrates and added sugar, but poor in vitamins and minerals. | |

|

What is New: • Compared with children in the 1st tertile of UPF consumption, those in the 3rd tertile had 2.57 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.51-4.40) of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients after adjusting for potential confounders. • The adjusted proportions of children with inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients were 23%, 27% and 35% in the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd tertiles of UPF consumption respectively. |

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s00431-023-05026-9.

Keywords: Micronutrient, EAR, Ultraprocessed food, Healthy eating, Public health

Introduction

Micronutrients are vitamins and minerals involved in several functions, including the production of enzymes, hormones, and other substances such as coenzymes, regulatory factors and antioxidants necessary for immunocompetence, normal growth and development. Although micronutrients are needed in very small amounts, they have a major impact on health [1]. An inadequate intake can not only cause visible and severe health conditions, but also less clinically notable reductions in energy level, mental clarity and overall capacity, leading to reduced educational outcomes (low level of concentration or attention, difficulties related to logical memory) and work productivity as well as increased risk of other diseases [1]. Indeed, micronutrient deficiency is among the 20 most important risk factors for diseases and affect around two billion people worldwide [2].

One way to reduce micronutrient deficiency is through an adequate intake of healthy food. However, ultra-processed foods (UPF) are penetrating dietary patterns across the globe [3]. Over the last 20 years, probably as a consequence of industrialization and globalization, the consumption of UPF has increased drastically worldwide, reaching the alarming proportion of 50%–60% of daily energy intake in several high-income countries [4–6]. Spain is not an exception since, in the last decade, in the whole population, the consumption of UPF increased from 11 to 32% [7, 8].

Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in adult populations showed that UPF consumption is associated with higher body mass index [9–11] and waist circumference [11, 12], as well as higher risk of excess weight [10–13], hypertension [14], metabolic syndrome [15], dyslipidemias [16], asthma and wheezing [13], functional gastrointestinal disorders [17], overall cancer risk, and breast cancer risk [18]. These findings are at least partially explained by the nutritional quality of UPF-rich diets, that tend to be higher in total fat [19], carbohydrate [19, 20], Na [21], and added or free sugars [21, 22]. On the other hand, they tend to be lower in protein [19], fiber [19], vitamin C [19, 23, 24], vitamin A [19, 23], β-carotene [9], vitamin D [19, 23, 24], vitamin E [24], vitamin B1 [19, 23], vitamin B2 [23], vitamin B6 [19, 23], vitamin B12 [23], vitamin B3 [19, 23], folic acid [9], Zn [23, 24], K [19, 20, 23], P [23, 24], Mg [19, 23, 24], Ca [9, 23, 24], Fe [19, 23, 24], and fruits and vegetables [4, 9, 10, 24].

Although there are studies on the consumption of UPF and nutritional dietary profiles in the general population [25], to our knowledge, the association between UPF consumption and the risk of inadequate micronutrient intake in childhood has not yet been assessed. We hypothesized that children who have a high consumption of UPF may be at increased risk of having an insufficient intake of certain micronutrients. Therefore, we conducted this study to evaluate whether higher UPF consumption was associated with a higher number of micronutrients with suboptimal intake, as well as to calculate the marginal effect of UPF consumption on the risk of having an inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients in a sample of children from the Mediterranean area.

Material and methods

Study population

The “Seguimiento del Niño para un Desarrollo Óptimo” (SENDO) project (Follow-up of Children for Optimal Development) is a dynamic prospective pediatric cohort focused on studying the link between diet and lifestyle and the risk of childhood obesity. Pediatricians and our team’s researchers invite potential participants to join the study, through health care centers or schools. Through online self-administered questionnaires that parents complete, information is gathered at baseline and updated annually. Inclusion criteria are: 1) age between 4 and 5 years old, and 2) residence in Spain. The only exclusion criterion is the lack of an internet connected device to complete the questionnaires.

Out of the 989 children enrolled between 2015 and June 2021, 183 were excluded because they had not completed the baseline questionnaire at the start of the study. Therefore, the analyzed sample included 806 children with complete information in all the variables analyzed.

Dietary information

Information on participants’ diets was gathered with a previously validated 147-item semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire (FFQ) [26]. Parents reported how often their child had consumed each food item over the previous year by choosing one out of nine categories of response ranging from ‘never or almost never’ to ‘6 or more times per day’. A team of dietitians calculated the nutrient content of each food item multiplying the frequency of consumption by the edible portion and the nutrient composition of the pre-specified portion size. Information on nutrient composition was extracted from updated Spanish food composition tables [27].

All food items were classified by their degree of processing according to the NOVA classification system (Supplementary Table 1) [28, 29]. Four groups were defined: Group 1, unprocessed or minimally processed foods; Group 2, processed culinary ingredients; Group 3, processed foods; and Group 4, ultra-processed foods. The percentage of the total energy intake (TEI) that came from each NOVA group was calculated as:

We determined micronutrient intake adequacy for the following 20 micronutrients with known public health relevance: Zn; I; Se; Fe; Ca; K; P; Mg; Cr; Na; vitamin B1; vitamin B2; vitamin B3; vitamin B6; folic acid, vitamin B12; vitamin C; vitamin A; vitamin D, and vitamin E. The probability of intake adequacy was calculated by comparing the intakes of these nutrients with the estimated average requirements (EAR) if these were available or adequate intake (AI) levels, if not [30]. We used the traditional and probabilistic [31] approach, in which the probability of adequacy for the usual intake of a nutrient is calculated from a z-score, as:

Assessment of covariates

The questionnaire collected information on sociodemographic and lifestyle variables, family and personal medical history, and dietary habits.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using reported data as weight (kg)/height-squared (m2). Nutritional status was defined based on age and sex-specific cutoff points from the International Obesity Task Force [32]. Participants’ parents reported the time their child spent watching television, using the computer, or playing video games on average during the previous year. Information for weekdays and weekends was collected separately. Using that information, screen time was calculated as the mean hours/day a child spent watching television, using a computer, or playing video games. Information on physical activity was collected using a questionnaire validated for the Spanish population that included 14 activities and 10 response options ranging from never to 11 or more hours/week [33]. Four of these activities were rated as moderate (≤ 5 METs/hour), while 10 were rated as vigorous (> 5 METs/hour) [34] and the annual mean hours/day that each participant spent in moderate-to-vigorous activities was calculated. Questions about the recommended intake frequency of 18 distinct food groups and 9 response categories ranging from "Never" to "6 or more times per day" were used to assess parental knowledge of nutritional recommendations for children. Each question scored + 1 point if the answer met dietary recommendations and 0 points if it did not. Parents of participants were classified as having high (> 70%), medium (40–70%), or poor (40%) dietary awareness based on their final score. Through 8 yes/no questions, parental attitudes toward their child's eating habits were assessed. Positive responses (i.e., positive attitudes) scored + 1 point, whereas negative responses (i.e., negative attitudes) scored 0 points. Parents of participants were classified as having unhealthy (0–3 points), medium (4–6 points) or healthy attitudes (7–8 points) towards their child’s dietary habits.

Statistical analysis

Participants were stratified in tertiles according to the dietary energy contribution of UPFs in their diet. We used numbers (percentages) for categorical variables and means (SD) for quantitative variables for descriptive purposes. By allocating the median of UPF consumption to each tertile and assuming this variable as continuous, linear trend tests across tertiles were calculated.

We calculated the association between UPF consumption (main independent variable) and 1) the mean number of micronutrients with inadequate intake (dependent variable in this model), and 2) the odds of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients (dependent variable in this model). In subsequent analyses we evaluated the marginal effect, that is, the adjusted proportion of children with inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients in each tertile of UPF consumption. Crude and multivariable adjusted estimates were calculated. Multivariate analyses were progressively adjusted for the main known confounders according to the existing literature: model 1) sex, age, nutritional status, total energy intake; model 2) variables in model 1 plus maternal age, maternal higher education, parental knowledge about child nutritional recommendations, parental healthy dietary attitudes (healthy or unhealthy); and 3) variable in model 2 plus moderate-vigorous physical activity and screen time. We fitted hierarchical models (generalized estimating equations), which allowed the intra-cluster correlation between siblings to be taken into account. All p values are two-tailed. Statistical significance was settled at the conventional cut-off point of p < 0.05. Analyses were carried out using Stata version 15.0 (Stata Corporation).

Ethical standard

The SENDO project was approved by the Ethics Committee for Clinical Research of Navarra (Pyto. 2016/122). Informed consent was obtained from the parents of all participants at enrollment.

Results

This cross-sectional study included 806 participants (51% boys) with a mean age of 5 years old (sd 0.9) and an average UPF consumption of 38% (SD 9.5) of TEI. Medians (interquartile ranges) of UPF consumption by tertiles were 29% (24%-31%), 38% (36%-40%) and 46% (44%-52%) of TEI in T1, T2 and T3 respectively. Table 1 shows participants’ and families’ main characteristics according to tertiles of UPF consumption. Children who reported higher UPF consumption had slightly older mothers (p = 0.02) and came from larger families (p < 0.001). On the other hand, both parental attitudes towards their child’s dietary habits and parental knowledge on nutritional recommendations for children were inversely associated with UPF consumption (p < 0.001). Regarding children’s characteristics, those who reported higher UPF consumption were slightly older (p < 0.001), more physically active (p < 0.001), and spent more time on screens (p < 0.001). In contrast, they were less likely to have been breastfed (p < 0.001). A direct and marginally significant association was observed between UPF consumption and z-score of the BMI (p = 0.07). Nevertheless, mean z-scores of BMI were close to zero in all the tertiles of UPF consumption and absolute differences were small.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participants and their families in the SENDO project by tertiles of UPF consumption. Numbers are mean (SD) or N (%)

| All the sample | T1 | T2 | T3 | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 806 | 269 | 269 | 268 | |

| Median (interquartile range) of the percentage of total energy intake from UPF, % |

38% (31%-44%) |

27% (24%-31%) |

38% (36%-40%) |

48% (44%-52%) |

| Family’s characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (y) | 40.0 (4.0) | 39.6 (3.9) | 40.0 (4.0) | 40.4 (3.9) | 0.02 |

| Maternal age, N (%) | 0.02 | ||||

| < 35 years | 83 (10) | 36 (13) | 25 (9.2) | 22 (8.2) | |

| 35–40 years | 323 (40) | 107 (40) | 116 (43) | 100 (37) | |

| 40–45 years | 317 (39) | 103 (38) | 100 (37) | 114 (43) | |

| > 45 years | 83 (10) | 23 (8.5) | 28 (10) | 32 (12) | |

| Maternal higher education, N (%) | 649 (81) | 217 (81) | 228 (85) | 204 (76) | 0.2 |

| Number of children, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| 1 child | 87 (11) | 39 (14) | 21 (7.8) | 27 (10) | |

| 2 children | 412 (51) | 160 (60) | 133 (49) | 119 (44) | |

| 3 children | 179 (22) | 54 (20) | 60 (22) | 65 (24) | |

| 4 or more | 128 (16) | 16 (5.9) | 55 (20) | 57 (21) | |

| Family history of obesity, N (%) | 157 (19) | 56 (21) | 50 (19) | 51 (19) | 0.59 |

| Parental attitudes towards child’s dietary habits, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Unhealthy (0–3 p) | 46 (5.7) | 7 (2.6) | 17 (6.3) | 22 (8.2) | |

| Medium (4–5 p) | 265 (33) | 64 (24) | 91 (34) | 110 (41) | |

| Healthy (6–8 p) | 495 (61) | 198 (74) | 161 (60) | 136 (51) | |

| Parental knowledge about child’s nutritional recommendations, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| Low (< 40%) | 183 (23) | 31 (12) | 65 (24) | 87 (32) | |

| Medium (40–70%) | 518 (64) | 183 (68) | 168 (62) | 167 (62) | |

| High (> 70%) | 105 (13) | 55 (20) | 36 (13) | 14 (5.2) | |

| Children’s characteristics | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (female), N (%) | 397 (49) | 147 (55) | 123 (46) | 127 (47) | 0.08 |

| Age (y) | 5.03 (0.9) | 4.83 (0.7) | 5.08 (0.9) | 5.16 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| Race (white), N (%) | 779 (97) | 259 (96) | 263 (98) | 257 (96) | 0.83 |

| Gestational age, N (%) | 0.77 | ||||

| < 38 weeks | 117 (15) | 37 (14) | 41 (15) | 39 (15) | |

| 38–40 weeks | 322 (40) | 110 (41) | 111 (42) | 101 (38) | |

| ≥ 40 weeks | 361 (45) | 120 (45) | 114 (43) | 127 (48) | |

| Birthweight (g) | 3233 (552.2) | 3215 (508.2) | 3243 (519.2) | 3242 (623.3) | 0.56 |

| Birthweight, N (%) | 0.23 | ||||

| < 2,500 g | 77 (9.6) | 24 (8.9) | 23 (8.6) | 30 (11) | |

| 2,500 to < 3,000 g | 171 (21) | 67 (25) | 52 (20) | 52 (19) | |

| 3,000 to < 3,500 g | 316 (39) | 106 (40) | 116 (44) | 94 (35) | |

| 3,500 to < 4,000 g | 194 (24) | 56 (21) | 65 (24) | 73 (27) | |

| ≥ 4,000 g | 42 (5.3) | 14 (5.2) | 10 (3.7) | 18 (6.7) | |

| Breastfeeding duration, N (%) | < 0.001 | ||||

| No breastfeeding | 125 (16) | 18 (6.7) | 49 (18) | 58 (22) | |

| < 6 months | 252 (31) | 77 (29) | 85 (32) | 90 (34) | |

| 6–12 months | 209 (26) | 68 (25) | 71 (26) | 70 (26) | |

| ≥ 12 months | 220 (27) | 106 (39) | 64 (24) | 50 (19) | |

| Child’s position among siblings, N (%) | 0.97 | ||||

| The oldest/ singletons | 299 (37) | 106 (39) | 99 (37) | 94 (35) | |

| 2nd/3 or 2nd-3rd/4 | 138 (17) | 27 (10) | 61 (23) | 50 (19) | |

| The youngest or > the 4th | 369 (46) | 136 (51) | 109 (41) | 124 (46) | |

| Z-score of the BMI | 0.07 (1.2) | -0.04 (1.2) | 0.12 (1.1) | 0.13 (1.1) | 0.07 |

| Nutritional Status, N (%) | 0.17 | ||||

| Low weight | 113 (14) | 46 (17) | 36 (13) | 31 (12) | |

| Normal weight | 592 (73) | 191 (71) | 197 (73) | 204 (76) | |

| Overweight/obesity | 101 (13) | 32 (12) | 36 (13) | 33 (12) | |

| Total energy intake (kcal) | 2113 (538) | 2043 (549) | 2092 (486) | 2205 (564) | < 0.001 |

| Moderate-vigorous physical activity (h/day) | 2.1 (2.7) | 1.4 (1.3) | 2.2 (2.7) | 2.5 (3.4) | < 0.001 |

| Screen time (h/day) | 1.1 (0.9) | 0.9 (1.0) | 0.9 (0.6) | 1.2 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

Table 2 shows energy-adjusted average intake of the 20 micronutrients evaluated by tertiles of UPF consumption. We found a significant inverse association between UPF consumption and the intake of 15 out of the 20 micronutrients evaluated (p < 0.01): vitamin A, vitamin C, vitamin D, vitamin E, vitamin B1, vitamin B3, vitamin B6, folic acid, vitamin B12, iron, phosphorus, magnesium, selenium, chrome, and potassium.

Table 2.

Energy-adjusted micronutrient intake by tertiles of total UPF consumption

| T1 | T2 | T3 | p for trend | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 269 | 269 | 268 | |

| Micronutrients | ||||

| Vitamin A (g/d) | 1280 (31) | 1132 (31) | 1005 (31) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin C (mg/d) | 180 (4.2) | 145 (4.2) | 119 (4.2) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin D (g/d) | 3.87 (0.12) | 3.43 (0.12) | 2.87 (0.12) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin E (mg/d) | 10.1 (0.2) | 8.73 (0.20) | 7.82 (0.20) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin B1 (mg/d) | 1.54 (0.01) | 1.51 (0.01) | 1.45 (0.01) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin B2 (mg/d) | 2.14 (0.03) | 2.13 (0.03) | 2.18 (0.03) | 0.37 |

| Vitamin B3 (mg/d) | 39.9 (0.5) | 37.9 (0.5) | 34.8 (0.5) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg/d) | 2.59 (0.03) | 2.39 (0.03) | 2.21 (0.03) | < 0.001 |

| Folic Acid (g/d) | 352 (5.2) | 315 (5.2) | 285 (5.2) | < 0.001 |

| Vitamin B12 (g/d) | 5.09 (0.09) | 4.96 (0.09) | 4.71 (0.09) | 0.004 |

| Ca (mg/d) | 1231 (17) | 1226 (17) | 1212 (17) | 0.44 |

| I (g/d) | 115 (1.4) | 114 (1.4) | 113 (1.4) | 0.35 |

| Fe (mg/d) | 15.3 (0.1) | 14.5 (0.1) | 13.6 (0.1) | < 0.001 |

| P (mg/d) | 1972 (54) | 1845 (54) | 1779 (54) | 0.01 |

| Mg (mg/d) | 333 (2.9) | 306 (2.9) | 293 (3.0) | < 0.001 |

| Se (g/d) | 78.1 (0.8) | 75.1 (0.8) | 70.4 (0.8) | < 0.001 |

| Zn (mg/d) | 10.3 (0.1) | 10.1 (0.1) | 9.9 (0.1) | 0.06 |

| Cr (g/d) | 74.6 (1.5) | 73.4 (1.5) | 68.3 (1.5) | 0.006 |

| K (mg/d) | 3837 (42) | 3518 (42) | 3313 (42) | < 0.001 |

| Na (mg/d) | 3069 (57) | 3143 (57) | 3073 (57) | 0.93 |

Numbers are mean (SD)

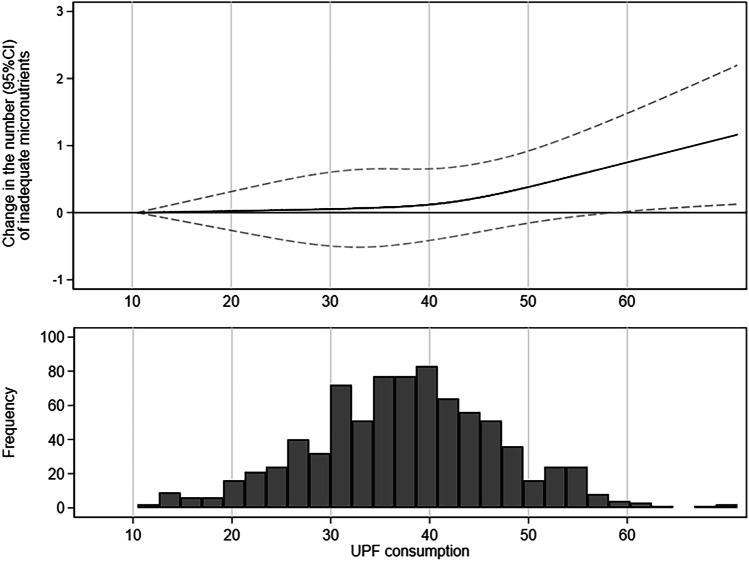

After adjusting for potential confounders, the number of micronutrients with inadequate intake rose by 0.14 (95% CI 0.06–0.23) for each 10% increase in UPF consumption (data not shown). Figure 1 shows a direct association between UPF consumption and the average number of micronutrients with inadequate intake. The spline at the top of Fig. 1 shows the change in inadequate micronutrient intake (solid line) and 95% CI (dashed line) associated with one unit increase (% of TEI) in UPF consumption. The slope of the line becomes steeper for UPF consumption above 45% of TEI, but the association reaches statistical significance only for greater values of UPF consumption (approximately 60% of TEI). According to the histogram at the bottom of Fig. 1, the distribution of UPF consumption in this sample was almost normal, with a slight positive skewness. 70% of participants reported UPF consumption between 30 and 50% of TEI, a range in which one unit increase in the percentage of UPF consumption was not significantly associated with an increase in the number of inadequate intakes of micronutrients.

Fig. 1.

The spline above shows the difference (95% CI) with respect to the lowest consumption (10% of energy intake) in the average number of inadequate micronutrients associated with ultra-processed food consumption. The histogram below shows the frequency of participants by ultra-processed food consumption

A significant linear trend was found in the odds of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients across tertiles of UPF consumption (Table 3). Compared with children in the first tertile (T1), those in the third tertile (T3) of UPF consumption had 1.59 times higher odds (95% CI 1.09 – 2.33) of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients in the crude model. Stronger estimates were observed through progressive adjustments. The most adjusted model showed that, after accounting for personal (sex, age, nutritional status, energy intake, physical activity and screen time) and family confounders (maternal age, maternal higher education, parental knowledge on nutritional recommendations in childhood and parental attitudes towards their child’s dietary habits), children in T3 of UPF consumption had 2.57 times higher odds (95% CI: 1.51–4.40) of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients compared with their peers in T1.

Table 3.

OR and 95% Confidence Interval (CI) of failing to meet 3 or more micronutrients recommendations associated with the consumption of ultra-processed foods (% of TEI)

| OR (95% CI) | P for trend | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | T2 | T3 | ||

| N | 269 | 269 | 268 | |

| N of participants (%) failing to meet ≥ 3 micronutrients recommendations | 64 (24) | 74 (28) | 89 (33) | |

| Crude |

1.00 (Ref.) |

1.26 (0.87–1.85) |

1.59 (1.09–2.33) |

0.017 |

| Multivariable adjusted model 1 |

1.00 (Ref.) |

1.47 (0.92–2.35) |

2.99 (1.81–4.95) |

< 0.001 |

| Multivariable adjusted model 2 |

1.00 (Ref.) |

1.30 (0.80–2.12) |

2.52 (1.50–4.26) |

0.001 |

| Multivariable adjusted model 3 |

1.00 (Ref.) |

1.41 (0.86–2.32) |

2.57 (1.51–4.40) |

0.001 |

Model 1 is adjusted for sex (male or female), age (continuous), nutritional status (underweight, normal weight, overweight/obese), total energy intake (tertiles)

Model 2 is additionally adjusted for maternal age (< 35y, 35–40y, > 40–45y, > 45y), maternal higher education (yes or no), parental knowledge about child’s nutritional recommendations (low, medium score or high), parental attitudes towards child’s dietary habits (unhealthy, average, healthy)

Model 3 is additionally adjusted for physical activity (tertiles) and screen time (tertiles)

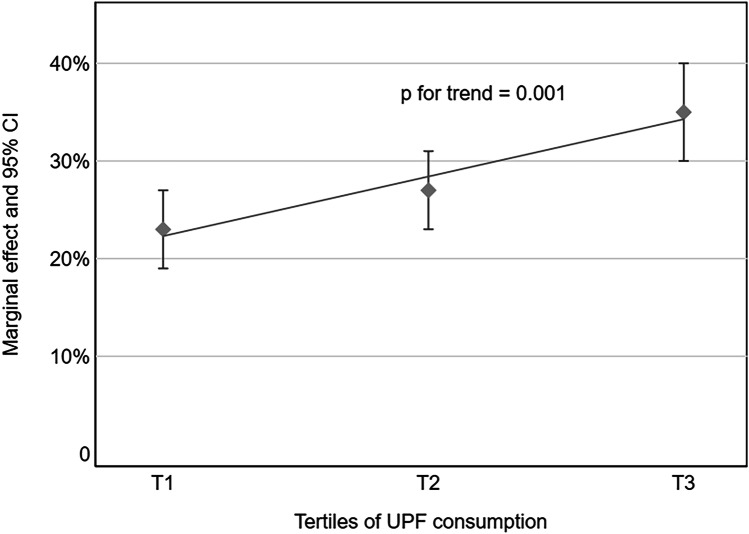

After accounting for all the potential confounders, the adjusted proportions of children with inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients were 23% (95% CI: 19%-27%), 27% (95% CI: 23%-31%) and 35% (95% CI: 30%-40%) in T1, T2 and T3 respectively. Figure 2 shows the point estimates (95% CI) and the fitting line with a slope of 0.58, which indicates that 1% increase in UPF consumption was associated with a 0.58 increase in the percentage of children with inadequate intake of 3 or more micronutrients (p for trend < 0.001).

Fig. 2.

Adjusted proportions (95% CI) of children with 3 or more micronutrient inadequacy by tertiles of UPF consumption using the traditional method to define inadequacy

To assess the strength of our findings, we re-ran the analyses after excluding children with extreme values of energy intake (above 99th percentile and below 1st percentile) and obtained similar estimates (data not shown). On the other hand, we observed a reduced proportion of children with inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients using the probabilistic approach. Moreover, sensitivity analysis using the probabilistic approach also showed a significant trend for inadequate intake of 2 or more micronutrients across tertiles of UPF consumption (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Discussion

In this cross-sectional analysis of children in the SENDO project a direct linear association between UPF consumption and the mean number of micronutrients with inadequate intake was found, with significant increases for UPF consumption above 60% of TEI. Indeed, after accounting for personal and family potential confounders, children in the third tertile of UPF consumption showed higher odds (OR 2.57; 95% CI: 1.51- 4.40) of failing to comply with ≥ 3 micronutrient recommendations. Along with this, we found that the proportion of children with inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients significantly increased across tertiles of UPF consumption from 23% (95% CI: 19%-27%) in T1 to 35% (95% CI: 30%-40%) in T3. Previous evidence focused on single micronutrients or on small number of them [35]. To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to investigate the association between the consumption of UPF and the intake of 20 micronutrients with public health relevance in children from the Mediterranean area.

We consider these findings to be of great interest because they reinforce the need for public health strategies to eliminate UPF from children's diets [36, 37]. Although we found significant increases in the number of inadequate micronutrients for UPF consumption over 60%, that threshold must be interpreted with caution. We reported with good reason the marginal effect of UPF consumption, which is easier to interpret and to convey to the population [38]. Although that threshold is far from the mean UPF consumption observed in our sample, several high-income countries have reported mean UPF consumption above 50–60% of TEI [5]. The high proportion of children with inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients in all the tertiles of UPF consumption shows that there is no place for UPF in a healthy diet and that we should not concern ourselves with defining a healthy threshold. The Big Food companies invest heavily in studying the texture, taste, smell, shape, sound in the mouth and packaging of UPF in order to generate highly attractive, addictive and ultra-palatable products, to which it is very difficult not to succumb [39]. The marketing of UPF is also an issue of concern. Almost 80% of food advertisements are for UPF [40]. Besides, the advertising departments of these companies very often include psychologists and neurologists that know how to influence our conscious and unconscious decision making [41]. In addition, there is the issue of accessibility and affordability. According to the Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food [42], in Spain most food products (74%) are purchased in supermarkets or hypermarkets, where the supply of unprocessed or minimally processed products is lower than that of UPFs (20% compared to approximately 80%), which also tend to have more and better economic offers. There is an urgent need to regulate the production, manufacturing, advertising and distribution of this type of product while implementing initiatives that favor the consumption of fresh foods to facilitate the adoption of healthier diets by families [43].

Our team previously published that parents’ healthy attitudes towards their child’s dietary habits were associated with greater nutritional adequacy of the child’s diet [44] and that they are a strong predictor of UPF consumption [45]. The present study adds to existing evidence by suggesting that higher UPF consumption may be the link between unhealthy parental attitudes toward the child’s dietary habits and nutritional inadequacy. Although prospective studies are needed before causality can be inferred, this evidence suggests that the observed association is probably not just due to residual confounding.

Our data agree with previous studies regarding the mean UPF consumption and the prevalence of micronutrient inadequacy [46]. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that the use of self-reported data might have hampered our results and that our estimates may represent the upper limit of the true association. Further research is needed to elucidate the real magnitude of the risk of micronutrient deficiency associated with UPF consumption.

Our findings contrast with a previous study in Brazilian children that reported that 2 to 3-year-old children from low-income families could be at risk of excessive micronutrient intakes provided by UPF [47]. However, it must be noted that that study focused on fortified products for young children, which do not represent the whole group of products in NOVA 4 group.

We must acknowledge some limitations. First, due to the cross-sectional design, causality cannot be inferred. Second, FFQ used in the SENDO project did not collect information on food processing. To reduce possible misclassification, two researchers categorized food items into the NOVA groups and discrepancies were resolved by consensus. Third, although FFQ are the most practical and feasible tool to measure dietary intake in epidemiological studies [48], they tend to overestimate dietary intake and therefore they cannot be considered the gold standard to calculate micronutrient intake. An overestimation of dietary intake in this study would mean that the micronutrient inadequacy may still be higher than observed. Fourth, our results only show the probability of nutritional adequacy, since the best way to assess actual nutrient deficiency would be through the determination of biomarkers of nutrient intake. Fifth, most of the participants in the SENDO project have highly educated parents and live in a developed country. Although this factor may limit the generalizability of our findings, it reduces the confounding by socio-economic status [49]. Sixth, given the observational design of this study, the possibility of residual confounding by unmeasured variables cannot be completely ruled out. Lastly, the questionnaire on parental knowledge on nutritional recommendations for children and the one on their attitudes towards their child’s dietary habits have not been validated. However, previous studies showed that they are associated with diet quality in adult populations [50, 51].

Our study has several strengths, including the relevance of the issue and the fact that dietary intake of 20 micronutrients was assessed. Additionally, the sample size was large, and the questionnaire was extensive, which enabled adjustment for several personal and family confounders. Besides, analyses were fitted with hierarchical models that took into account intra-cluster correlation between siblings, a prevalent flaw in research on pediatric populations.

In conclusion, we found that high consumption of UPF is associated with increased odds of inadequate intake of ≥ 3 micronutrients in childhood. Although our sample reported an average UPF consumption of 38%, which is lower than the alarming 50–60% observed in several high-income countries, we still found a direct linear association between UPF consumption and micronutrient inadequate intake. Public policies and health education initiatives are needed to eliminate UPF from children’s diets and foster the consumption of unprocessed and minimally processed products.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The SENDO project is conducted thanks to the joint work of the University of Navarra and the Primary Health Care Service of the Servicio Navarro de Salud-Osasunbidea. Thus, we would like to thank all the pediatricians and all the researchers involved in this project. Finally, we thank all the participants and their families for their willingness to collaborate in the SENDO Project.

List of abbreviations in alphabetical order

- BMI

Body mass index

- Ca

Calcium

- CI

Confidence interval

- Cr

Chrome

- EAR

Estimated Average Requirement

- Fe

Iron

- FFQ

Food-frequency questionnaire

- I

Iodine

- K

Potassium

- Mg

Magnesium

- Na

Sodium

- OR

Odds Ratio

- P

Potassium

- RDA

Recommended Dietary Allowance

- SD

Standard deviation

- Se

Selenium

- SENDO

Seguimiento del Niño para un Desarrollo Óptimo

- T1-T2-T3

First, second and third tertiles

- TEI

Total energy intake

- UPF

Ultra processed foods

- Zn

Zinc

Authors' contributions

LGB, NMC designed the study. LGB, NMC, VDP and SS performed the statistical analyses. MAMG helped with intellectual content and interpretation of the results. LGB and NMC wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors critically reviewed the manuscript and approved its final version.

Funding

Open Access funding provided thanks to the CRUE-CSIC agreement with Springer Nature. Instituto de Salud Carlos III through the CIBERobn CB12/03/30038, which is co-funded by the European Regional Development Fund.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval

The SENDO project follows the rules of the Declaration of Helsinki on the ethical principles for medical research in human beings. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Navarra (Pyto. 2016/122).

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the participants’ parents.

Competing interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References:

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). Micronutrients. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/micronutrients#tab. Accessed Dec 2022

- 2.Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M et al (2006) Global Burden of Disease and Risk Factors. Washington (DC) Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK11812/?term=Lopez%20AD%2C%20Mathers%20CD%2C%20Ezzati%20M. Accesed Dec 2022

- 3.Wang L, Martínez Steele E, Du M, et al. Trends in Consumption of Ultraprocessed Foods Among US Youths Aged 2–19 Years, 1999–2018. JAMA. 2021;326:519–530. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.10238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adams J, White M. Characterisation of UK diets according to degree of food processing and associations with socio-demographics and obesity: Cross-sectional analysis of UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey (2008–12) Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12:160. doi: 10.1186/s12966-015-0317-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steele EM, Baraldi LG, Da Costa Louzada ML, Moubarac JC, Mozaffarian D, Monteiro CA. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the US diet: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2016;6:1–8. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baker P, Machado P, Santos T, Sievert K, Backholer K, Hadjikakou M, et al. Ultra-processed foods and the nutrition transition: Global, regional and national trends, food systems transformations and political economy drivers. Obes Rev. 2020;21:e13126. doi: 10.1111/obr.13126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Latasa P, Louzada MLDC, Martinez Steele E, Monteiro CA. Added sugars and ultra-processed foods in Spanish households (1990–2010) Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72:1404–1412. doi: 10.1038/s41430-017-0039-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mertens E, Colizzi C, Peñalvo JL. Ultra-processed food consumption in adults across Europe. Eur J Nutr. 2022;61:1521–1539. doi: 10.1007/s00394-021-02733-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Julia C, Martinez L, Allès B, Touvier M, Hercberg S, Méjean C, et al. Contribution of ultra-processed foods in the diet of adults from the French NutriNet-Santé study. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:27–37. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Canella DS, da Louzada ML, C, Claro RM, Costa JC, Bandoni DH, Levy RB, , et al. Consumption of vegetables and their relation with ultra-processed foods in Brazil. Rev saúde pública. 2018;52:50. doi: 10.11606/S1518-8787.2018052000111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Silva FM, Giatti L, De Figueiredo RC, Molina MDCB, De Oliveira CL, Duncan BB, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed food and obesity: Cross sectional results from the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) cohort (2008–2010) Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:2271–2279. doi: 10.1017/S1368980018000861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Juul F, Martinez-Steele E, Parekh N, Monteiro CA, Chang VW. Ultra-processed food consumption and excess weight among US adults. Br J Nutr. 2018;120:90–100. doi: 10.1017/S0007114518001046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monteiro CA, Moubarac JC, Levy RB, Canella DS, Da Costa Louzada ML, Cannon G. Household availability of ultra-processed foods and obesity in nineteen European countries. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:18–26. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendonça RD, Lopes AC, Pimenta AM, Gea A, Martinez-Gonzalez MA, Bes-Rastrollo M. Ultra-processed food consumption and the incidence of hypertension in a mediterranean cohort: The seguimiento universidad de navarra project. Am J Hypertens. 2017;30:358–366. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tavares LF, Fonseca SC, Garcia Rosa ML, Yokoo EM. Relationship between ultra-processed foods and metabolic syndrome in adolescents from a Brazilian Family Doctor Program. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:82–87. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011001571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rauber F, Campagnolo PDB, Hoffman DJ, Vitolo MR. Consumption of ultra-processed food products and its effects on children’s lipid profiles: A longitudinal study. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;25:116–122. doi: 10.1016/j.numecd.2014.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schnabel L, Buscail C, Sabate JM, Bouchoucha M, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, et al. Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Consumption and Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders: Results From the French NutriNet-Santé Cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113:1217–1228. doi: 10.1038/s41395-018-0137-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fiolet T, Srour B, Sellem L, Kesse-Guyot E, Allès B, Méjean C, et al. Consumption of ultra-processed foods and cancer risk: Results from NutriNet-Santé prospective cohort. BMJ. 2018;360:k322. doi: 10.1136/bmj.k322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen Y, Huang Y, Lo YC, Wu H, Mark L, Lee M. Secular trend towards ultra-processed food consumption and expenditure compromises dietary quality among Taiwanese adolescents. Food Nutr Res. 2018;1:1–9. doi: 10.29219/fnr.v62.1565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rauber F, da Louzada ML, C, Steele EM, Millett C, Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Ultra-processed food consumption and chronic non-communicable diseases-related dietary nutrient profile in the UK (2008–2014) Nutrients. 2018;10:587. doi: 10.3390/nu10050587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Batal M, Johnson-Down L, Moubarac JC, Ing A, Fediuk K, Sadik T, et al. Quantifying associations of the dietary share of ultra-processed foods with overall diet quality in First Nations peoples in the Canadian provinces of British Columbia, Alberta, Manitoba and Ontario. Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:103–113. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cediel G, Reyes M, Da Costa Louzada ML, Martinez Steele E, Monteiro CA, Corvalán C, et al. Ultra-processed foods and added sugars in the Chilean diet (2010) Public Health Nutr. 2018;21:125–133. doi: 10.1017/S1368980017001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moubarac JC, Batal M, Louzada ML, Martinez Steele E, Monteiro CA. Consumption of ultra-processed foods predicts diet quality in Canada. Appetite. 2017;108:512–520. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Martínez Steele E, Popkin BM, Swinburn B, Monteiro CA. The share of ultra-processed foods and the overall nutritional quality of diets in the US: Evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional study. Popul Health Metr. 2017;15:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12963-017-0119-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Martini D, Godos J, Bonaccio M, Vitaglione P, Grosso G. Ultra-processed foods and nutritional dietary profile: A meta-analysis of nationally representative samples. Nutrients. 2021;13:1–16. doi: 10.3390/nu13103390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zazpe I, Santiago S, de la O V, Romanos-Nanclares A, Rico-Campà A, Álvarez-Zallo N, , et al. Validity and reproducibility of a semi-quantitative food frequency questionnaire in spanish preschoolers: the SENDO project. Nutr Hosp. 2020;37:672–684. doi: 10.20960/nh.03003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tuni OM, Carbajal Á, Forneiro LC, et al. Food Composition Tables: Practice Guide. Madrid: Pirámide; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Monteiro CA, Levy RB, Claro RM, de Castro IRR, Cannon G. A new classification of foods based on the extent and purpose of their processing. Cad Saude Publica. 2010;26:2039–2049. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2010001100005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Da Rocha BRS, Rico-Campà A, Romanos-Nanclares A, Ciriza E, Barbosa KBF, Martínez-González MÁ, et al. Adherence to Mediterranean diet is inversely associated with the consumption of ultra-processed foods among Spanish children: The SENDO project. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24:3294–3303. doi: 10.1017/S1368980020001524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Institute of Medicine Food Nutrition Board . Dietary reference intakes: applications in dietary assessment. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Anderson GH, Peterson RD, Beaton GH. Estimating nutrient deficiencies in a population from dietary records: The use of probability analyses. Nutr Res. 1982;2:409–415. doi: 10.1016/S0271-5317(82)80049-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cole TJ, Lostein T. Extended international (IOTF) Body Mass indez cut-offs for thiness, overweight and obesity. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7:284–294. doi: 10.1111/j.2047-6310.2012.00064.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martínez-González MA, López-Fontana C, Varo JJ, Sánchez-Villegas A, Martinez JA. Validation of the Spanish version of the physical activity questionnaire used in the Nurses' Health Study and the Health Professionals' Follow-up Study. Public Health Nutr. 2005;8:920–927. doi: 10.1079/PHN2005745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ainsworth BE, Haskell WL, Whitt MC, Irwin ML, Swartz AM, Strath SJ, et al. Compendium of physical activities: an update of activity codes and MET intensities. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2000;32:S498–504. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200009001-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Falcão RCTMA, Lyra CO, Morais CMM, Pinheiro LGB, Pedrosa LFC, Lima SCVC, et al. Processed and ultra-processed foods are associated with high prevalence of inadequate selenium intake and low prevalence of vitamin B1 and zinc inadequacy in adolescents from public schools in an urban area of northeastern Brazil. PLoS ONE. 2019;14:e0224984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0224984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Casas R. Moving towards a Healthier Dietary Pattern Free of Ultra-Processed Foods. Nutrients. 2022;14:14–17. doi: 10.3390/nu14010118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.da Louzada ML, C, Martins APB, Canella DS, Baraldi LG, Levy RB, Claro RM, , et al. Impact of ultra-processed foods on micronutrient content in the Brazilian diet. Rev Saude Publica. 2015;49:45. doi: 10.1590/S0034-8910.2015049006211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tolles J, Meurer WJ. Logistic regression: Relating patient characteristics to outcomes. J Am Med Assoc. 2016;316:533–534. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.7653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yates J, Gillespie S, Savona N, Deeney M, Kadiyala S. Trust and responsibility in food systems transformation. Engaging with Big Food: marriage or mirage? BMJ Glob Heal. 2021;6:1–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Royo-Bordonada M, León-Flández K, Damián J, Bosqued-Estefanía MJ, Moya-Geromini M, López-Jurado L. The extent and nature of food advertising to children on Spanish television in 2012 using an international food-based coding system and the UK nutrient profiling model. Public Health. 2016;137:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.OuazzaniTouhami Z, Benlafkih L, Jiddane M, Cherrah Y, El Malki HO, Benomar A. Neuromarketing: When marketing meet neurosciences. Rev Neurol (Paris) 2011;167:135–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neurol.2010.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Spanish Ministry of Agriculture, Fishery and Fooods (2020) Informe del consumo de alimentación en España. Available at: https://www.mapa.gob.es/es/alimentacion/temas/consumo-tendencias/informe-anual-consumo-2020. Accessed Dec 2022

- 43.World Health Organization (WHO). Evaluating Implementation of the WHO set of Recommendations on the Marketing of Foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children: progress, challenges and guidance for next steps in the WHO European Region. Available at: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/345153. Accessed Dec 2022

- 44.Romanos-Nanclares A, Zazpe I, Santiago S, Marín L, Rico-Campà A, Martín-Calvo N. Influence of parental healthy-eating attitudes and nutritional knowledge on nutritional adequacy and diet quality among preschoolers: The SENDO project. Nutrients. 2018;10:1875. doi: 10.3390/nu10121875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.García-Blanco L, De La O Pascual V, Berasaluce A, Moreno-Galarraga L, Martínez-González MÁ, Martín-Calvo N (2022) Individual and family predictors of ultra-processed food consumption in Spanish children. the SENDO project. Public Health Nutr 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Marrón-Ponce JA, Sánchez-Pimienta TG, Rodríguez-Ramírez S, Batis C, Cediel G. Ultra-processed foods consumption reduces dietary diversity and micronutrient intake in the Mexican population. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2022;36:241–251. doi: 10.1111/jhn.13003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sangalli CN, Rauber F, Vitolo MR. Low prevalence of inadequate micronutrient intake in young children in the south of Brazil: A new perspective. Br J Nutr. 2016;116:890–896. doi: 10.1017/S0007114516002695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Willett W. Food Frequency Methods. In: Willett W, editor. Nutritional Epidemiology. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2012. pp. 870–887. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rothman KJ, Gallacher JEJ, Hatch EE. Why representativeness should be avoided. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42:1012–1014. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Andrade L, Zazpe I, Santiago S, Carlos S, Bes-Rastrollo M, Martínez-González MA. Ten-Year Changes in Healthy Eating Attitudes in the SUN Cohort. J Am Coll Nutr. 2017;36:319–329. doi: 10.1080/07315724.2016.1278566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Santiago S, Zazpe I, Gea A, de la Rosa PA, Ruiz-Canela M, Martínez-González MA (2017) Eating attitudes and the incidence of cardiovascular disease: the SUN cohort. Int J Food Sci Nutr 68595–604 [DOI] [PubMed]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.