Abstract

Background

Children with severe atopic dermatitis (AD) have a multidimensional disease burden.

Objective

Here we assess the clinically meaningful improvements in AD signs, symptoms, and quality of life (QoL) in children aged 6–11 years with severe AD treated with dupilumab compared with placebo.

Methods

R668-AD-1652 LIBERTY AD PEDS was a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, phase III clinical trial of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids (TCS) in children aged 6–11 years with severe AD. This post hoc analysis focuses on 304 patients receiving either dupilumab or placebo with TCS and assessed the percentage of patients considered responsive to dupilumab treatment at week 16.

Results

At week 16, almost all patients receiving dupilumab + TCS (95%) demonstrated clinically meaningful improvements in AD signs, symptoms, or QoL compared with placebo + TCS (61%, p < 0.0001). Significant improvements were seen as early as week 2 and sustained through the end of the study in the full analysis set (FAS) and the subgroup of patients with an Investigator’s Global Assessment score greater than 1 at week 16.

Limitations

Limitations include the post hoc nature of the analysis and that some outcomes were not prespecified; the small number of patients in some subgroups potentially limits generalizability of findings.

Conclusion

Treatment with dupilumab provides significant and sustained improvements within 2 weeks in AD signs, symptoms, and QoL in almost all children with severe AD, including those who did not achieve clear or almost clear skin by week 16.

Trial Registration

Video Abstract: Does dupilumab provide clinically meaningful responses in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis? (MP4 99484 kb)

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40257-023-00791-7.

| Digital Features for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.22777115 |

Key Points

| It is most clinically relevant to interpret efficacy endpoints defined for clinical trials within the context of patient-reported outcome measures that comprehensively characterize atopic dermatitis (AD) signs, symptoms, and quality of life. |

| In a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial of dupilumab plus concomitant topical corticosteroids in children aged 6–11 years with severe AD, almost all children receiving dupilumab showed significant and clinically relevant improvements in AD skin signs, symptoms, and quality of life after 16 weeks of treatment when compared with placebo plus topical corticosteroids. Dupilumab also provided significant and clinically meaningful improvements within a subgroup of patients who did not achieve the defined primary endpoint of clear or almost clear skin (Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 or 1) by week 16. |

| These findings are consistent with prior findings in adults and adolescents. |

Introduction

Children with severe atopic dermatitis (AD) have a multidimensional disease burden, with skin lesions that often affect a large body surface area (BSA), intense pruritus, sleep disturbances, and impaired quality of life (QoL) [1–4]. While short-term topical corticosteroids (TCS) are commonly used for pediatric patients with AD, disease control with TCS is often inadequate in patients with severe AD [5]. Although AD is the most common chronic inflammatory skin disease in children, few long-term systemic treatment options are available to control severe AD. Systemic corticosteroids are often used to treat acute AD exacerbations, but this approach can result in rebound flares after treatment cessation, so is considered relatively contraindicated by current dermatology guidelines [6]. Nonsteroidal systemic immunosuppressants are used off label [6–9].

Dupilumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody [10, 11], blocks the shared receptor subunit for interleukin (IL)-4 and IL-13, thus inhibiting signaling of both IL-4 and IL-13. In the USA, dupilumab is approved for the treatment of AD in adults, adolescents, and children aged 6 months to 11 years [12]. Multiple clinical trials of dupilumab in infants, children, adolescents, and adults demonstrate rapid, significant, and sustained improvements in AD signs and symptoms as well as QoL with an acceptable safety profile [4, 13–17].

In a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial in children aged 6–11 with severe AD (R668-AD-1652 LIBERTY AD PEDS, NCT03345914), children receiving dupilumab with concomitant TCS showed significant improvements in AD skin signs, as demonstrated by an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) score of clear (0) or almost clear (1) and a 75% improvement in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75), the co-primary endpoints requested by health authorities [4, 18, 19]. While both are widely used and appropriate for assessing skin signs, more comprehensive assessments were used to better assess other AD signs, symptoms, and health-related QoL. Moreover, patients with severe AD participating in this trial responded to treatment but did not achieve clear or almost clear skin within 4 months. This highlights the need to consider a spectrum of clinically comprehensive assessments of response, to understand the impact of dupilumab treatment, including AD signs, symptoms, and QoL in children with severe AD [4].

In this report, we present a post hoc analysis of clinical outcomes assessing responsiveness to treatment in children aged 6–11 years using data from the full analysis set (FAS) of randomized patients in the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial. In parallel we also assessed treatment response in a subgroup of children who did not achieve clear or almost clear skin at week 16.

Methods

Study Design, Patients, and Treatment

The study design and primary results from the LIBERTY AD PEDS trial have been described elsewhere and are briefly summarized here [4]. LIBERTY AD PEDS was a randomized, placebo-controlled phase III clinical trial conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committees and the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their proxies prior to any study procedure. Eligible patients were children aged 6–11 years with severe AD and a documented history of inadequate response to topical AD treatment within 6 months of study baseline. At screening and study baseline, eligible patients had an IGA score of 4, EASI score ≥ 21, affected BSA ≥ 15%, numerical rating scale (NRS) score ≥ 4, and weight ≥ 15 kg. Patients were randomized 1:1:1 to receive dupilumab 300 mg every 4 weeks (q4w) + TCS, a weight-based regimen of dupilumab 100 mg (baseline weight < 30 kg) or 200 mg (baseline weight ≥ 30 kg) every 2 weeks (q2w) + TCS, or placebo + TCS. In this post hoc analysis, we included patients receiving dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS (regardless of weight), dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS (baseline weight ≥ 30 kg), or placebo + TCS.

Outcomes Assessed in This Analysis

The primary endpoint of LIBERTY AD PEDS was the proportion of patients with an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear) at week 16. In the European Union and EU reference countries, the co-primary outcome was the proportion of patients achieving EASI-75. The outcomes examined in this analysis include the proportion of patients achieving a composite endpoint comprising a 50% improvement in EASI (EASI-50), and/or a ≥ 3-point reduction in Peak Pruritus NRS, and/or a ≥ 6-point reduction in Children’s Dermatology Quality of Life Index (CDLQI) from baseline, as well as the proportion of patients achieving individual endpoints: EASI-50; 50% improvement in SCORing Atopic Dermatitis (SCORAD) total score (SCORAD-50); ≥ 3-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS; ≥ 4-point improvement in Peak Pruritus NRS; ≥ 6-point improvement in CDLQI; ≥ 6-point improvement in the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM); score of “no” or “mild” symptoms on the Patient Global Impression of Disease (PGID); and “much better” on the Patient Global Impression of Change (PGIC). In the PGID questionnaire, scored on a 5-point scale (no, mild, medium, severe, very severe), patients were asked about their disease over the past 7 days; while the PGIC measures the perceived change in symptoms since treatment start also on a 5-point scale (much better, a little better, the same, a little worse, much worse). Least squares (LS) mean percent change from baseline in EASI, Peak Pruritus NRS, SCORAD sleep visual analog scale (VAS), and Global Individual Signs Score (GISS) are also reported. GISS measures severity of AD signs of erythema, infiltration/papulation, excoriation and lichenification globally, and not by separate anatomical areas, on a 4-point scale from 0 (none) to 3 (severe). We also assessed the proportion of patients achieving EASI-50 and/or Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3 at week 16. Improvement thresholds for Peak Pruritus NRS (≥ 3 points) were based on the published minimal clinically important differences in adults and adolescents with AD, whereas POEM and CDLQI were based on the published minimal clinically important differences in children with AD [20–22].

These analyses were performed using the FAS as well as a subset of patients who did not achieve an IGA score of 0 or 1 (clear or almost clear skin) at week 16 (IGA > 1 subgroup).

Statistical Analysis

Statistical methods for the LIBERTY AD PEDS study have been reported previously [4]. Categorical efficacy endpoints were analyzed using the Cochran–Mantel–Haenszel test adjusted by randomization strata (baseline disease severity and weight). Patients with missing values at week 16 or who used rescue medication before week 16 were considered “non responders.” Continuous endpoints were analyzed using multiple imputation with analysis of covariance with treatment, randomization strata and relevant baseline values included in the analysis. Efficacy data after rescue medication use were treated as missing and imputed using multiple imputation. Descriptive statistics were used to assess demographic and clinical characteristics.

LS mean percent change from baseline was reported for EASI and Peak Pruritus NRS, and LS mean change from baseline was reported for SCORAD sleep VAS scores. The proportions of patients achieving prespecified thresholds for other outcomes were reported as the number and percentage of total. Patients with missing values at week 16 were considered “non responders” and were combined with patients who did not achieve an IGA score of 0 or 1 at week 16 in the IGA > 1 subgroup.

Results

Patients

The FAS consisted of 304 patients, of whom 122 received dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS, 59 received dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS, and 123 received placebo + TCS. As reported previously, significantly more patients receiving dupilumab achieved an IGA score of 0 or 1 compared with placebo at week 16 [4]. The IGA > 1 subgroup consisted of 227 patients, of whom 82 received dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS, 36 received dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS, and 109 received placebo + TCS. Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics were generally similar across treatment groups in the FAS and the IGA > 1 subgroup (Table 1). Disease severity at baseline was balanced across the FAS and IGA > 1 subgroup, as reflected by similar IGA, EASI, SCORAD, GISS, CDLQI, and POEM scores, as well as percent BSA affected by AD. Most patients had at least one comorbid allergic condition (> 89% across all treatment groups).

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographics and clinical characteristics

| Characteristic | FAS (n = 304) | IGA > 1 subgroup (n = 227) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS (n = 59) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 122) | Placebo + TCS (n = 123) | Dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS (n = 36) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 82) | Placebo + TCS (n = 109) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 9.5 (1.36) | 8.5 (1.74) | 8.3 (1.76) | 9.7 (1.33) | 8.5 (1.81) | 8.4 (1.76) |

| Male, n (%) | 33 (55.9) | 57 (46.7) | 61 (49.6) | 22 (61.1) | 38 (46.3) | 52 (47.7) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 40.2 (9.99) | 31.0 (9.40) | 31.5 (10.82) | 41.5 (10.97) | 31.4 (10.43) | 31.7 (10.89) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 20.2 (4.03) | 17.6 (2.93) | 17.9 (3.90) | 20.7 (4.54) | 17.7 (3.21) | 18.0 (3.90) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||||||

| Hispanic or Latino | 9 (15.3) | 16 (13.1) | 13 (10.6) | 7 (19.4) | 8 (9.8) | 12 (11.0) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 45 (76.3) | 89 (73.0) | 77 (62.6) | 27 (75.0) | 59 (72.0) | 65 (59.6) |

| Black or African American | 8 (13.6) | 19 (15.6) | 23 (18.7) | 6 (16.7) | 13 (15.9) | 21 (19.3) |

| Asian | 4 (6.8) | 5 (4.1) | 13 (10.6) | 1 (2.8) | 3 (3.7) | 13 (11.9) |

| Other | 1 (1.7) | 8 (6.6) | 9 (7.3) | 1 (2.8) | 7 (8.5) | 9 (8.3) |

| Not reported/missing | 1 (1.7) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | 1 (2.8) | 0 | 1 (0.9) |

| Duration of AD (years), mean (SD) | 8.1 (2.25) | 7.4 (2.44) | 7.2 (2.15) | 8.4 (2.25) | 7.4 (2.57) | 7.3 (2.04) |

| Disease severity and QoL, mean (SD) unless otherwise noted | ||||||

| IGA score 4, n (%) | 59 (100.0) | 121 (99.2) | 123 (100.0) | 36 (100.0) | 81 (98.8) | 109 (100) |

| EASI total score (0–72) | 37.1 (11.77) | 37.4 (12.45) | 39.0 (12.01) | 38.6 (13.30) | 39.4 (12.95) | 39.8 (12.01) |

| Peak pruritus NRS score, mean (SD) (0–10) | 7.6 (1.49) | 7.8 (1.58) | 7.7 (1.54) | 7.5 (1.56) | 8.0 (1.56) | 7.8 (1.55) |

| BSA affected by AD (%) | 53.9 (20.17) | 54.8 (21.58) | 60.2 (21.46) | 56.9 (21.46) | 58.1 (22.02) | 61.1 (21.99) |

| SCORAD total score (0–103) | 71.2 (11.29) | 75.6 (11.71) | 72.9 (12.01) | 72.6 (11.89) | 77.5 (11.36) | 73.7 (12.22) |

| GISS (0–12) | 10.3 (1.34) | 10.3 (1.38) | 10.2 (1.54) | 10.3 (1.31) | 10.4 (1.41) | 10.3 (1.52) |

| CDLQI (0–30) | 13.0 (6.25) | 16.2 (7.85) | 14.6 (7.41) | 14.1 (6.40) | 16.9 (7.78) | 14.8 (7.45) |

| POEM score (0–28) | 19.9 (5.33) | 21.3 (5.51) | 20.7 (5.48) | 19.9 (5.48) | 21.7 (5.50) | 21.2 (5.32) |

| History of atopic comorbidities, n/N1 (%) | ||||||

| Patients with ≥ 1 concurrent allergic condition, excluding AD | 54/58 (93.1) | 107/120 (89.2) | 112/121 (92.6) | 32/35 (91.4) | 72/80 (90.0) | 100/107 (93.5) |

| Allergic conjunctivitis (keratoconjunctivitis) | 6/58 (10.3) | 14/120 (11.7) | 16/121 (13.2) | 3/35 (8.6) | 8/80 (10.0) | 16/107 (15.0) |

| Allergic rhinitis | 42/58 (72.4) | 73/120 (60.8) | 73/121 (60.3) | 26/35 (74.3) | 49/80 (61.3) | 67/107 (62.6) |

| Asthma | 29/58 (50.0) | 55/120 (45.8) | 55/121 (45.5) | 16/35 (45.7) | 34/80 (42.5) | 50/107 (46.7) |

| Chronic rhinosinusitis | 1/58 (1.7) | 5/120 (4.2) | 4/121 (3.3) | 1/35 (2.9) | 3/80 (3.8) | 4/107 (3.7) |

| Eosinophilic esophagitis | 0 | 1/120 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Food allergy | 35/58 (60.3) | 75/120 (62.5) | 84/121 (69.4) | 23/35 (65.7) | 53/80 (66.3) | 76/107 (71.0) |

| Hives | 7/58 (12.1) | 14/120 (11.7) | 8/121 (6.6) | 5/35 (14.3) | 11/80 (13.8) | 7/107 (6.5) |

| Nasal polyps | 2/58 (3.4) | 0 | 0 | 1/35 (2.9) | 0 | 0 |

| Other allergies | 33/58 (56.9) | 67/120 (55.8) | 82/121 (67.8) | 22/35 (62.9) | 44/80 (55.0) | 75/107 (70.1) |

| Patients receiving prior systemic medications for AD, n/N1 (%) | 16/58 (27.6) | 42/120 (35.0) | 36/121 (29.8) | 13/35 (37.1) | 31/80 (38.8) | 35/107 (32.7) |

| Patients receiving prior | ||||||

| Systemic corticosteroids | 11/58 (19.0) | 25/120 (20.8) | 17/121 (14.0) | 10/35 (28.6) | 16/80 (20.0) | 16/107 (15.0) |

| Systemic nonsteroidal immunosuppressants | 6/58 (10.3) | 23/120 (19.2) | 22/121 (18.2) | 4/35 (11.4) | 19/80 (23.8) | 22/107 (20.6) |

| Azathioprine | 0 | 2/120 (1.7) | 0 | 0 | 2/80 (2.5) | 0 |

| Cyclosporine | 4/58 (6.9) | 17/120 (14.2) | 12/121 (9.9) | 4/35 (11.4) | 14/80 (17.5) | 12/107 (11.2) |

| Methotrexate | 1/58 (1.7) | 7/120 (5.8) | 11/121 (9.1) | 0 | 6/80 (7.5) | 11/107 (10.3) |

| Mycophenolate | 1/58 (1.7) | 2/120 (1.7) | 2/121 (1.7) | 0 | 2/80 (2.5) | 2/107 (1.9) |

AD atopic dermatitis, BMI body mass index, BSA body surface area, CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, FAS full analysis set, GISS Global Individual Signs Score, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, QoL quality of life, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SD standard deviation, TCS topical corticosteroids

Clinician‑ and Patient‑Reported Outcomes

Full Analysis Set

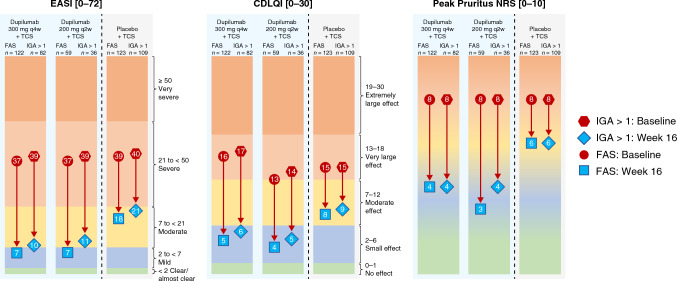

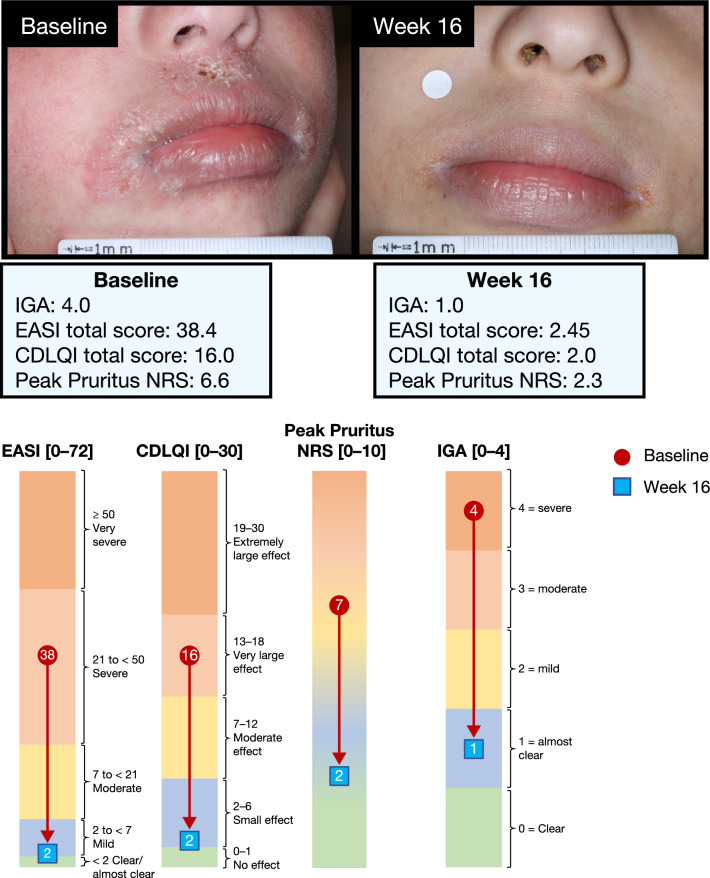

More patients receiving dupilumab achieved clinically meaningful improvements from baseline in AD signs (EASI-50), symptoms (Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement), and/or QoL (CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement) at week 16 (300 mg q4w + TCS: 95.1%, 200 mg q2w + TCS: 94.9%) compared with placebo (61.0%; p < 0.0001 for both; Fig. 1). This effect was rapid, with significant improvements versus placebo observed as early as week 2, and they were sustained through to the end of the study. Similar results were observed for the proportion of patients achieving clinically meaningful improvements from baseline in AD signs (EASI-50) and/or symptoms (Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement) only, again with similar efficacy across doses (300 mg q4w + TCS: 93.4%, 200 mg q2w + TCS: 89.8%) compared with placebo + TCS (49.6%; p < 0.0001 for both; Fig. S1). Figure 2 shows absolute values for EASI, Peak Pruritus NRS, and CDLQI at baseline and week 16. Greater improvements from baseline to week 16 were seen across all three outcome measures with dupilumab compared with placebo, with similar efficacy across the two doses. Clinically meaningful improvement across all three measures was achieved in 49.5% of patients in the 300-mg q4w + TCS group and 56.0% of patients in the 200-mg q2w + TCS group compared with 9.9% in the placebo + TCS group (p < 0.0001 for both). Clinically meaningful improvement in two of the three measures was achieved in 84.4% of patients in the 300-mg q4w + TCS group and 82.0% of patients in the 200-mg q2w + TCS group compared with 34.2% in the placebo + TCS group (p < 0.0001 for both). The proportion of patients achieving an IGA score reduction from baseline ≥ 2 at week 16 was also significantly greater in both dupilumab groups (300 mg q4w + TCS: 69.7%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 71.2%) compared with placebo + TCS (30.9%; p < 0.0001 for both). The proportion of patients responding “no” or “mild” symptoms on the PGID questionnaire was significantly higher in both dupilumab groups (300 mg q4w + TCS: 65.6%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 69.5%) compared with placebo + TCS (17.1%; p < 0.0001 for both). Similarly, the proportion of patients responding “much better” on the PGIC questionnaire was also significantly higher in both dupilumab groups (300 mg q4w + TCS: 70.5%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 79.7%) compared with placebo + TCS (26.8%; p < 0.0001 for both).

Fig. 1.

Proportion of patients achieving EASI-50, change in Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3, or change in CDLQI ≥ 6 over time (FAS and IGA > 1 subgroup). *p < 0.05 versus placebo, ***p < 0.0001 versus placebo (for FAS). ap < 0.05 versus placebo, bp < 0.01 versus placebo, cp < 0.0001 versus placebo (for IGA >1 subgroup). CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-50 improvement from baseline of at least 50% in EASI, FAS full analysis set, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, NRS numerical rating scale, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, TCS topical corticosteroids

Fig. 2.

Change in mean EASI score, mean Peak Pruritus NRS score, and mean CDLQI score from baseline to week 16 (FAS and IGA > 1 subgroup). The color scale graphic displays the changes in absolute values from baseline (red) to week 16 (blue) for each outcome. EASI ranges from < 2 (clear/almost clear) to 2 to < 7 (mild), 7 to < 21 (moderate), 21 to < 50 (severe), and ≥ 50 (very severe). CDLQI ranges from 0 to 1 (no effect) to 2–6 (small effect), 7–12 (moderate effect), 13–18 (very large effect), and 19–30 (extremely large effect). Peak Pruritus NRS ranges from 0 (no itch, green zone) to 10 (worst itch imaginable, orange zone). Severity bands are based on validated published scales [21, 26–29]. CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, FAS full analysis set, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, NRS numerical rating scale, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, TCS topical corticosteroids

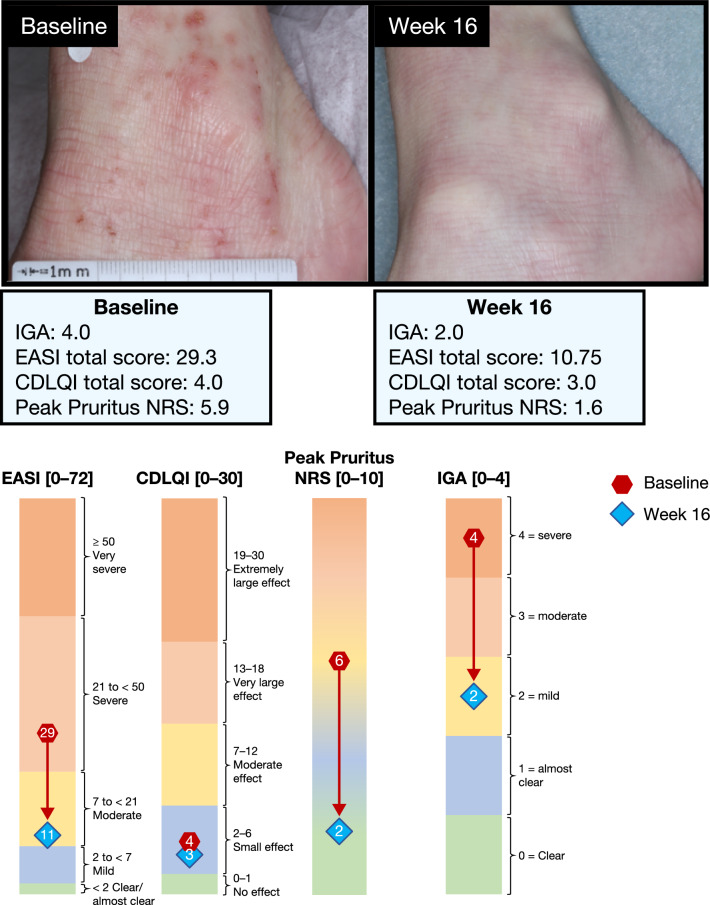

Figure 3 is an example photograph of a patient treated with dupilumab achieving an IGA score of 1, indicating almost clear skin, at week 16. This patient achieved the clinically meaningful response of EASI-50 (AD signs), a ≥ 6-point reduction in CDLQI (QoL) and ≥ 3-point reduction in Peak Pruritus NRS (symptoms).

Fig. 3.

Baseline and week 16 responses of a single patient achieving an IGA score of 1 at week 16. The color scale graphic displays the changes in absolute values from baseline (red) to week 16 (blue) for each outcome. EASI ranges from < 2 (clear/almost clear) to 2 to < 7 (mild), 7 to < 21 (moderate), 21 to < 50 (severe), and ≥ 50 (very severe). CDLQI ranges from 0 to 1 (no effect) to 2–6 (small effect), 7–12 (moderate effect), 13–18 (very large effect), and 19–30 (extremely large effect). Peak Pruritus NRS ranges from 0 (no itch, green zone) to 10 (worst itch imaginable, orange zone). Severity bands are based on validated published scales [21, 27–29]. CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, NRS numerical rating scale

IGA > 1 Subgroup

Similar to the FAS, a significantly greater proportion of patients in the IGA > 1 subgroup who received dupilumab achieved a clinically meaningful response of EASI-50, and/or ≥ 3-point reduction in Peak Pruritus NRS, and/or ≥ 6-point reduction in CDLQI throughout the study compared with placebo (Fig. 1), with significant improvements versus placebo and was observed as early as week 2, sustained to the end of the study, and similar efficacy was observed across both dupilumab doses at week 16 (300 mg q4w + TCS: 92.7%, 200 mg q2w + TCS: 91.7%, placebo + TCS: 56.0%; p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0003, respectively). These results were maintained when analyzing the proportions of patients achieving clinically meaningful improvement in AD signs or symptoms only (300 mg q4w + TCS: 90.2%, 200 mg q2w + TCS: 83.3%, placebo + TCS: 56.0%; p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0003, respectively; Fig. S1). Figure 2 shows absolute values for EASI, Peak Pruritus NRS, and CDLQI at baseline and week 16 in the IGA > 1 subgroup. As with the FAS, greater improvements from baseline to week 16 were seen across all three outcome measures, with either of the dupilumab doses compared with placebo, and with similar efficacy across the two doses. Clinically meaningful improvement across all three measures in the same patient was achieved in 43.8% of patients in the 300 mg q4w + TCS group and 45.2% of patients in the 200 mg q2w + TCS group, compared with 7.1% in the placebo group (p < 0.0001 for both). Clinically meaningful improvement in two of the three measures was achieved in 79.5% of patients in the 300 mg q4w + TCS group and 77.4% of patients in the 200 mg q2w + TCS group compared with 29.6% in the placebo + TCS group (p < 0.0001 for both). Similar to the FAS, the proportion of patients in the IGA > 1 subgroup achieving an IGA score reduction from baseline ≥ 2 at week 16 was greater in both dupilumab groups (300 mg q4w + TCS: 54.9%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 52.8%) compared with placebo + TCS (22.0%, p < 0.0001 and p = 0.0031, respectively). As expected from previous data, in the IGA > 1 subgroup, a numerically higher number of patients receiving dupilumab also achieved an IGA score of 2 (indicating mild disease; 300 mg q4w + TCS: 56.1%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 52.8%) compared with placebo + TCS (22.0%). Furthermore, the proportion of patients in the IGA > 1 subgroup responding “no” or “mild” symptoms on the PGID questionnaire was significantly higher in both dupilumab groups (300 mg q4w + TCS: 58.5%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 55.6%) compared with placebo + TCS (12.8%; p < 0.0001 for both). The proportion of patients responding “much better” on the PGIC questionnaire in this subgroup was also significantly higher in both dupilumab groups (300 mg q4w + TCS: 62.2%; 200 mg q2w + TCS: 69.4%) compared with placebo + TCS (21.1%; p < 0.0001 for both).

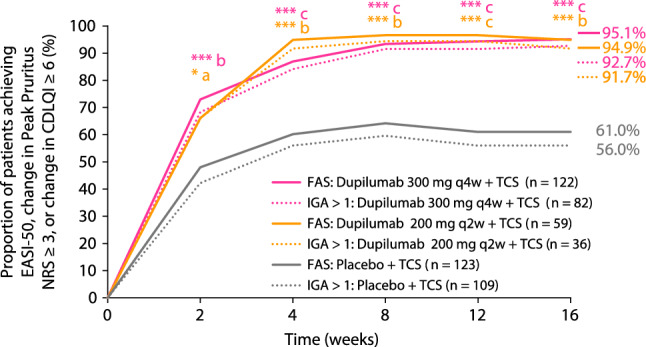

Figure 4 includes example photographs of a patient treated with dupilumab with an IGA score of 2, indicating mild AD, at baseline and week 16. This patient achieved the clinically meaningful response of EASI-50 (AD signs) and a ≥ 3-point reduction in Peak Pruritus NRS (symptoms).

Fig. 4.

Baseline and week 16 responses of a single patient in the IGA > 1 subgroup. The color scale graphic displays the changes in absolute values from baseline (red) to week 16 (blue) for each outcome. EASI ranges from < 2 (clear/almost clear) to 2 to < 7 (mild), 7 to < 21 (moderate), 21 to < 50 (severe), and ≥ 50 (very severe). CDLQI ranges from 0–1 (no effect) to 2–6 (small effect), 7–12 (moderate effect), 13–18 (very large effect), and 19–30 (extremely large effect). Peak Pruritus NRS ranges from 0 (no itch, green zone) to 10 (worst itch imaginable, orange zone). Severity bands are based on validated published scales [21, 27–29]. CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, FAS full analysis set, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, NRS numerical rating scale

Rescue Medication Use and Adverse Events

Fewer patients receiving dupilumab + TCS required rescue medication compared with those receiving placebo + TCS in both the IGA > 1 subgroup and the FAS (Table 2). Across all treatment groups, potent TCS were the most commonly used rescue medications.

Table 2.

Efficacy outcomes at week 16

| Characteristic | FAS (n = 304) | IGA > 1 subgroup (n = 227) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS (n = 59) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 122) | Placebo + TCS (n = 123) | Dupilumab 200 mg q2w + TCS (n = 36) | Dupilumab 300 mg q4w + TCS (n = 82) | Placebo + TCS (n = 109) | |

| IGA 0/1, n (%) |

23 (39.0) p = 0.0002 |

40 (32.8) p < 0.0001 |

14 (11.4) | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| EASI-50, n (%) |

51 (86.4) p < 0.0001 |

111 (91.0) p < 0.0001 |

53 (43.1) |

28 (77.8) p = 0.0002 |

71 (86.6) p < 0.0001 |

39 (35.8) |

| EASI-75, n (%) |

44 (74.6) p < 0.0001 |

85 (69.7) p < 0.0001 |

33 (26.8) |

21 (58.3) p = 0.0001 |

45 (54.9) p < 0.0001 |

20 (18.3) |

| EASI LS mean percent change from baseline (SE) |

− 80.4 (3.61) p < 0.0001 |

− 82.1 (2.37) p < 0.0001 |

− 48.6 (2.46) |

− 71.4 (4.78) p < 0.0001 |

− 75.7 (3.03) p < 0.0001 |

− 42.5 (2.76) |

| Peak Pruritus NRS score LS mean percent change from baseline (SE) |

− 58.2 (4.01) p < 0.0001 |

− 54.6 (2.89) p < 0.0001 |

− 25.9 (2.90) |

− 48.4 (4.96) p < 0.0001 |

− 50.0 (3.45) p < 0.0001 |

− 23.2 (3.11) |

| Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 3-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) |

38/57 (66.7) p < 0.0001 |

73/121 (60.3) p < 0.0001 |

26/123 (21.1) |

19/34 (55.9) p = 0.0008 |

45/81 (55.6) p < 0.0001 |

19/109 (17.4) |

| Peak Pruritus NRS ≥ 4-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) |

35/57 (61.4) p < 0.0001 |

61/120 (50.8) p < 0.0001 |

15/122 (12.3) |

17/34 (50.0) p < 0.0001 |

36/80 (45.0) p < 0.0001 |

9/108 (8.3) |

| SCORAD-50, n (%) |

44 (74.6) p < 0.0001 |

86 (70.5) p < 0.0001 |

28 (22.8) |

21 (58.3) p < 0.0001 |

46 (56.1) p < 0.0001 |

15 (13.8) |

| SCORAD Sleep VAS LS mean change from baseline (SE) |

− 4.56 (0.384) p < 0.0001 |

− 4.19 (0.245) p < 0.0001 |

− 1.96 (0.260) |

− 4.47 (0.502) p < 0.0001 |

− 4.10 (0.317) p < 0.0001 |

− 1.66 (0.302) |

| GISS LS mean percent change from baseline (SE) |

− 57.7 (3.17) p < 0.0001 |

− 57.0 (2.26) p < 0.0001 |

− 29.1 (2.36) |

− 46.2 (3.60) p < 0.0001 |

− 48.2 (2.50) p < 0.0001 |

− 24.1 (2.33) |

| POEM ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) |

46/58 (79.3) p < 0.0001 |

98/120 (81.7) p < 0.0001 |

39/122 (32.0) |

23/35 (65.7) p = 0.0002 |

60/81 (74.1) p < 0.0001 |

29/108 (26.9) |

| CDLQI ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline, n/N (%) |

42/52 (80.8) p < 0.0001 |

85/110 (77.3) p < 0.0001 |

47/111 (42.3) |

27/33 (81.8) p < 0.0001 |

54/74 (73.0) p < 0.0001 |

40/98 (40.8) |

| PGID “no” or “mild” symptoms, n (%) |

41 (69.5) p < 0.0001 |

80 (65.6) p < 0.0001 |

21 (17.1) |

20 (55.6) p < 0.0001 |

48 (58.5) p < 0.0001 |

14 (12.8) |

| PGIC “much better,” n (%) |

47 (79.7) p < 0.0001 |

86 (70.5) p < 0.0001 |

33 (26.8) |

25 (69.4) p < 0.0001 |

51 (62.2) p < 0.0001 |

23 (21.1) |

| Use of ≥ 1 rescue medication, n/N (%) | 2/59 (3.4) | 3/120 (2.5) | 23/120 (19.2) | 2/36 (5.6) | 3/80 (3.8) | 23/106 (21.7) |

| Use of ≥ 1 systemic rescue medication, n/N (%) | 1/59 (1.7) | 0 | 7/120 (5.8) | 1/36 (2.8) | 0 | 7/106 (6.6) |

CDLQI Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index, EASI Eczema Area and Severity Index, EASI-50 improvement from baseline of at least 50% in EASI, EASI-75 improvement from baseline of at least 75% in EASI, FAS full analysis set, GISS Global Individual Signs Score, IGA Investigator’s Global Assessment, LS least squares, N/A not applicable, NRS numerical rating scale, PGIC Patient Global Impression of Change, PGID Patient Global Impression of Disease, POEM Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure, q2w every 2 weeks, q4w every 4 weeks, SCORAD SCORing Atopic Dermatitis, SCORAD-50 SCORing Atopic Dermatitis total score, SE standard error, TCS topical corticosteroids, VAS visual analog scale

As reported previously, dupilumab demonstrated an acceptable safety profile in this patient population that was consistent with the known safety profile of dupilumab [4]. The incidences of serious adverse events and adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation were low and no deaths occurred (Table S1). Safety outcomes were comparable in the IGA > 1 subgroup and FAS.

Discussion

The IGA score is a simple and commonly used outcome measure in randomized clinical trials for AD and is required by the US Food and Drug Administration as a primary endpoint in all dermatology drug trials [18, 19]. The IGA score measures the overall (“global”) severity of skin signs such as redness and induration on a 5-point scale (0–4) and was validated for AD [23]. In registration trials, treatment success is typically defined as an IGA score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear). However, the IGA score does not capture the extent of AD skin involvement, patient-reported outcomes such as pruritus and sleep quality, or health-related QoL. As a result, the IGA score does not encompass the full extent of AD disease burden or the impact of AD treatments in children with severe AD.

In the present analysis, a clinically meaningful response was defined as achieving EASI-50, a reduction of ≥ 3 points in the Peak Pruritus NRS, and/or a reduction of ≥ 6 points in the CDLQI from baseline (hereby considering a multidimensional benefit across AD signs, symptoms, and QoL). On the basis of this definition, almost all children receiving dupilumab plus TCS achieved a clinically meaningful response at week 16 in the FAS (300 mg q4w + TCS: 95.1%, 200 mg q2w + TCS: 94.9%) as well as the IGA > 1 subgroup (300 mg q4w + TCS: 92.7%, 200 mg q2w + TCS: 91.7%). Our analysis of outcomes that reflect patient perception based on a single question, such as PGIC and PGID, confirms that the majority of children treated with dupilumab considered their disease to be “much better” and had “no or mild symptoms” at week 16. Safety outcomes were consistent with the known safety profile of dupilumab and were comparable between the FAS and IGA > 1 subgroup. These findings are consistent with prior studies in adults and adolescents and highlight the importance of comprehensively assessing treatment response in all disease domains [24, 25]. However, the response observed across treatment arms in the current study was slightly higher compared with that reported previously in adolescents and adults [24, 25]. It is possible that the higher response in this study is related to early treatment in children (versus later treatment in adolescents and adults), which could potentially result in a better treatment response. Although we cannot exclude the possibility of natural disease remission as an alternative explanation, the short course of study (16 weeks) and severe disease in these children, with high proportions of atopic comorbidities (increasing the risk of protracted disease), make this unlikely.

The analyses reported herein have some limitations. Some outcomes were not prespecified (meaning that they were not planned prior to study initiation), including the proportion of patients achieving a ≥ 6-point improvement from baseline in POEM or CDLQI scores and changes in SCORAD sleep VAS. The small number of patients included in some subgroups also potentially limits the generalizability of the findings.

Conclusions

Dupilumab provides significant, and sustained improvements within 2 weeks in AD signs, symptoms (including pruritus and sleep loss), and QoL in almost all children aged 6–11 years with severe AD, including those who did not achieve clear or almost clear skin by week 16.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Declarations

Data availability

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., FDA, EMA, PMDA), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.

Funding

This research was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc. ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT03345914. The study sponsors participated in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data; writing of the report; and the decision to submit the article for publication. Medical writing and editorial assistance were provided by Liselotte van Delden of Excerpta Medica, and was funded by Sanofi and Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., according to the Good Publication Practice guideline.

Conflict of interest

Elaine C. Siegfried: Dermavant, Eli Lilly, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Verrica Pharmaceuticals—consultant; GlaxoSmithKline, LEO Pharma, Novan—data and safety monitoring board; Eli Lilly, Janssen, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Stiefel, Verrica Pharmaceuticals—Principal Investigator in clinical trials. Michael J. Cork: AbbVie, Astellas Pharma, Boots, Dermavant, Galapagos, Galderma, Hyphens Pharma, Johnson & Johnson, LEO Pharma, L’Oréal, Menlo Therapeutics, Novartis, Oxagen, Pfizer, Procter & Gamble, Reckitt Benckiser, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc., Sanofi—investigator and/or consultant. Norito Katoh: AbbVie, Celgene Japan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Lilly Japan, Maruho, Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma, Sanofi, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Torii Pharmaceutical—speaker/consultant honoraria; A2 Healthcare, AbbVie, Boehringer Ingelheim Japan, Eisai, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kyowa Kirin, LEO Pharma, Lilly Japan, Maruho, Sun Pharma, Taiho Pharmaceutical, Torii Pharmaceutical—investigator grants. Haixin Zhang, Ryan B. Thomas, Sonya L. Cyr: Regeneron Pharmaceuticals Inc.—employees and shareholders. Chien-Chia Chuang, Ana B. Rossi, Annie Zhang: Sanofi—employees, may hold stock and/or stock options in the company.

Ethics approval

This study was conducted in accordance with ethical standards of the responsible committees and the Declaration of Helsinki and with the International Council for Harmonisation guidelines for Good Clinical Practice. The trial was overseen by an independent data and safety monitoring board. The protocol was reviewed and approved by institutional review boards/ethics committees at all centers.

Consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from all patients or their proxies.

Consent to publish

The authors affirm that human research participants provided informed consent for publication of the images in Figures 3 and 4. The participant has consented to the submission of the case report to the journal.

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Author contributions

AZ and SC contributed to manuscript concept and design. ECS and MJC contributed to data acquisition. All authors interpreted the data, provided critical feedback on the manuscript, approved the final manuscript for submission, and are accountable for the accuracy and integrity of the manuscript.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Beattie PE, Lewis-Jones MS. A comparative study of impairment of quality of life in children with skin disease and children with other chronic childhood diseases. Br J Dermatol. 2006;155(1):145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2006.07185.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chamlin SL. The psychosocial burden of childhood atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther. 2006;19(2):104–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8019.2006.00060.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Camfferman D, Kennedy JD, Gold M, Martin AJ, Lushington K. Eczema and sleep and its relationship to daytime functioning in children. Sleep Med Rev. 2010;14(6):359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2010.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Thaçi D, Wollenberg A, Cork MJ, Arkwright PD, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab with concomitant topical corticosteroids in children 6 to 11 years old with severe atopic dermatitis: a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1282–1293. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.06.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wollenberg A, Christen-Zäch S, Taieb A, Paul C, Thyssen JP, de Bruin-Weller M, European Task Force on Atopic Dermatitis/EADV Eczema Task Force et al. ETFAD/EADV Eczema task force 2020 position paper on diagnosis and treatment of atopic dermatitis in adults and children. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34(12):2717–2744. doi: 10.1111/jdv.16892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sidbury R, Davis DM, Cohen DE, Cordoro KM, Berger TG, Bergman JN, American Academy of Dermatology et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 3. Management and treatment with phototherapy and systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(2):327–349. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.03.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boguniewicz M, Alexis AF, Beck LA, Block J, Eichenfield LF, Fonacier L, et al. Expert perspectives on management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: a multidisciplinary consensus addressing current and emerging therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5(6):1519–1531. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schmitt J, Schäkel K, Fölster-Holst R, Bauer A, Oertel R, Augustin M, et al. Prednisolone vs. ciclosporin for severe adult eczema. An investigator-initiated double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre trial. Br J Dermatol. 2010;162(3):661–668. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2009.09561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simpson EL, Bruin-Weller M, Flohr C, Ardern-Jones MR, Barbarot S, Deleuran M, et al. When does atopic dermatitis warrant systemic therapy? Recommendations from an expert panel of the International Eczema Council. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;77(4):623–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2017.06.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Macdonald LE, Karow M, Stevens S, Auerbach W, Poueymirou WT, Yasenchak J, et al. Precise and in situ genetic humanization of 6 Mb of mouse immunoglobulin genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5147–5152. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323896111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Murphy AJ, Macdonald LE, Stevens S, Karow M, Dore AT, Pobursky K, et al. Mice with megabase humanization of their immunoglobulin genes generate antibodies as efficiently as normal mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5153–5158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1324022111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.US Food and Drug Administration. Dupixent® (dupilumab). Highlights of prescribing information. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2019/761055s014lbl.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2022.

- 13.Beck LA, Thaçi D, Hamilton JD, Graham NM, Bieber T, Rocklin R, et al. Dupilumab treatment in adults with moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(2):130–139. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1314768. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Simpson EL, Bieber T, Guttman-Yassky E, Beck LA, Blauvelt A, Cork MJ, SOLO 1 and SOLO 2 Investigators et al. Two phase 3 trials of dupilumab versus placebo in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(24):2335–2348. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1610020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blauvelt A, de Bruin-Weller M, Gooderham M, Cather JC, Weisman J, Pariser D, et al. Long-term management of moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis with dupilumab and concomitant topical corticosteroids (LIBERTY AD CHRONOS): a 1-year, randomised, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389(10086):2287–2303. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31191-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simpson EL, Paller AS, Siegfried EC, Boguniewicz M, Sher L, Gooderham MJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate to severe atopic dermatitis: a phase 3 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2020;156(1):44–56. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2019.3336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Paller AS, Simpson EL, Siegfried EC, Cork MJ, Wollenberg A, Arkwright PD, participating investigators et al. Dupilumab in children aged 6 months to younger than 6 years with uncontrolled atopic dermatitis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2022;400(10356):908–919. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Futamura M, Leshem YA, Thomas KS, Nankervis H, Williams HC, Simpson EL. A systematic review of Investigator Global Assessment (IGA) in atopic dermatitis (AD) trials: many options, no standards. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(2):288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chalmers JR, Schmitt J, Apfelbacher C, Dohil M, Eichenfield LF, Simpson EL, et al. Report from the third international consensus meeting to harmonise core outcome measures for atopic eczema/dermatitis clinical trials (HOME) Br J Dermatol. 2014;171(6):1318–1325. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yosipovitch G, Guillemin I, Eckert L, Reaney M, Nelson L, Clark M, et al. Validation of the Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) in adolescent moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis patients for use in clinical trials. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(Suppl. 2):S98. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yosipovitch G, Reaney M, Mastey V, Eckert L, Abbé A, Nelson L, et al. Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale: psychometric validation and responder definition for assessing itch in moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(4):761–769. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Simpson EL, de Bruin-Weller M, Bansal A, Chen Z, Nelson L, Whalley D, et al. Definition of clinically meaningful within-patient changes in POEM and CDLQI in children 6 to 11 years of age with severe atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2021;11(4):1415–1422. doi: 10.1007/s13555-021-00543-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Simpson E, Bissonnette R, Eichenfield LF, Guttman-Yassky E, King B, Silverberg JI, et al. The Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD): the development and reliability testing of a novel clinical outcome measurement instrument for the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):839–846. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silverberg JI, Simpson EL, Ardeleanu M, Thaçi D, Barbarot S, Bagel J, et al. Dupilumab provides important clinical benefits to patients with atopic dermatitis who do not achieve clear or almost clear skin according to the Investigator’s Global Assessment: a pooled analysis of data from two phase III trials. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(1):80–87. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Paller AS, Bansal A, Simpson EL, Boguniewicz M, Blauvelt A, Siegfried EC, et al. Clinically meaningful responses to dupilumab in adolescents with uncontrolled moderate-to-severe atopic dermatitis: post-hoc analyses from a randomized clinical trial. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020;21(1):119–131. doi: 10.1007/s40257-019-00478-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lewis-Jones MS, Finlay AY. The Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI): initial validation and practical use. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(6):942–949. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1995.tb16953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Waters A, Sandhu D, Beattie P, Ezughah F, Lewis-Jones S. Severity stratification of Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) scores. Br J Dermatol. 2010;163(Suppl 1):121. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basra MK, Salek MS, Camilleri L, Sturkey R, Finlay AY. Determining the minimal clinically important difference and responsiveness of the Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI): further data. Dermatology. 2015;230(1):27–33. doi: 10.1159/000365390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leshem YA, Hajar T, Hanifin JM, Simpson EL. What the Eczema Area and Severity Index score tells us about the severity of atopic dermatitis: an interpretability study. Br J Dermatol. 2015;172(5):1353–1357. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Qualified researchers may request access to study documents (including the clinical study report, study protocol with any amendments, blank case report form, statistical analysis plan) that support the methods and findings reported in this manuscript. Individual anonymized participant data will be considered for sharing once the product and indication has been approved by major health authorities (e.g., FDA, EMA, PMDA), if there is legal authority to share the data and there is not a reasonable likelihood of participant re-identification. Submit requests to https://vivli.org/.