Abstract

Objectives:

This study examined the relations between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development in 438 Mexican-origin (n = 242 boys and n = 196 girls) preadolescents. In addition, machismo and marianismo gender role attitudes were examined as potential mediators in this link.

Method:

Confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) of the Familial Ethnic Socialization Scale (FES), Machismo Measure (MM), Marianismo Beliefs Scale (MBS), and the Ethnic Identity Brief Scale (EISB) were conducted to test the factor structure with a preadolescent Mexican-origin sample. Separate path analyses of analytic models were then performed on boys and girls.

Results:

Results of the CFAs for survey measures revealed that for the FES, a 1-factor version indicated acceptable fit; for the MM, the original 2-factor structure indicated acceptable model fit; for the MBS, a revised 3-factor version indicated acceptable model fit; and, for the EISB, the affirmation and resolution dimensions showed acceptable fit. Among boys, FES was significantly and positively linked to caballerismo, and EISB affirmation and resolution; furthermore, the links between FES and EISB affirmation and resolution were indirectly connected by caballerismo. In addition, traditional machismo was negatively linked to EISB affirmation, and caballerismo was positively linked to EISB affirmation and resolution. Among girls, FES was significantly and positively related to the MBS-virtuous/chaste pillar, and EISB affirmation and resolution. The MBS-subordinate to others pillar was negatively linked to EISB affirmation.

Conclusions:

This study underscores the importance of FES and positive gender role attitudes in the link to ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin preadolescents.

Keywords: familial ethnic socialization, marianismo, machismo, ethnic identity, Latina/o

The development of a positive ethnic identity—an individual’s self-identification and sense of belonging, attachment, and involvement in the cultural and social practices of their ethnic group—has been identified as an essential component of positive adjustment and mental health in Latina/o adolescents (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor, Zeiders, & Updegraff, 2013). In particular, positive ethnic identity development has been linked to psychological well-being (Borrero & Yeh, 2011; Umaña-Taylor & Updegraff, 2007), increased self-esteem (Romero & Roberts, 2003), prosocial tendencies (e.g., coping; Armenta, Knight, Carlo, & Jacobson, 2011; Roberts et al., 1999), and better academic performance among Latina/o adolescents (Altschul, Oyserman, & Bybee, 2008; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007). Evidence suggests that Latina/o boys and girls may experience ethnic identity processes differently (Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010). These gender differences are theorized to be a function of familial socialization processes and gender role expectations for Latina/o boys and girls (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). However, despite the theoretical supposition of differential gender socialization processes underlying gender differences in ethnic identity development among Latina/o adolescents, to date, these relations have never been directly tested.

A central goal in this study was to investigate the function of gender role attitudes (i.e., marianismo and machismo, respectively; Arciniega, Anderson, Tovar-Blank, & Tracey, 2008; Castillo, Perez, Castillo, & Ghosheh, 2010) in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development in Latina/o preadolescent youth. Gender role attitudes are an important aspect of gender socialization and gender identity development and may be important mechanisms by which familial ethnic socialization shape ethnic identity development (Umaña-Taylor, O’Donnell, et al., 2014). We draw on the integrative framework of García Coll and colleagues (1996), which considers youths’ cultural and ecological context at the core of theoretical formulation of children’s normative development. We include in our conceptual model the role of familial ethnic socialization, which acknowledges the contextual role of the family in shaping adolescents’ developmental processes. Furthermore, we also extend the integrative model to include two culturally adaptive indicators of culture, gender role attitudes (machismo and marianismo, respectively; Arciniega et al., 2008; Castillo et al., 2010), and ethnic identity development (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2001). This will allow for the examination of the multidimensional nature of gender role attitudes in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development. Our findings may help researchers, educators, and practitioners in tailoring existing interventions for Latina/o adolescents, and challenge the aspects of gender roles that may negatively impact adolescents’ ethnic identity development.

Familial Ethnic Socialization

The family has been identified as a primary agent of ethnic socialization whereby cultural values, attitudes, and behaviors associated with ethnicity are transmitted from parents to children (Hughes, 2003; see Hughes, Witherspoon, Rivas-Drake, & West-Bey, 2009, for a review of ethnic socialization terminology and research). In the current study, we incorporate Umaña-Taylor and Fine’s (2001) familial ethnic socialization framework, which describes familial ethnic socialization along two dimensions. Overt familial ethnic socialization refers to parents’ direct actions to teach their children about their ethnicity, such as providing children with books about their culture or having discussions about the importance of knowing their culture (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2001). Covert familial ethnic socialization consists of parents’ unconscious transmission of cultural values and expectations related to ethnicity to their children via language preference, eating traditional foods from one’s native country, decorating the home with cultural objects, or listening to music that represents one’s cultural background (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2001).

Thus far, extant research shows that familial ethnic socialization has a positive and long-term impact on Latina/o youth’s ethnic identity development (Supple, Ghazarian, Frabutt, Plunkett, & Sands, 2006; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2001; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010; Umaña-Taylor, Zeiders, & Updegraff, 2013). For example, Umaña-Taylor, Alfaro, Bámaca, and Guimond (2009) found that among a predominantly Mexican-origin high school sample, high familial ethnic socialization during midadolescence was associated with increased exploration and resolution 2 years later. Similarly, Hernández, Conger, Robins, Bacher, and Widaman (2014) found that among Mexican-origin preadolescents, parental cultural socialization in fifth grade was predictive of the development of ethnic pride (i.e., ethnic identity affirmation) in seventh grade.

Some scholars suggest that Latino adolescent boys and girls may experience familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development processes differently (Raffaelli & Ontai, 2004). For example, in a study conducted by Umaña-Taylor and Guimond (2010), the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity exploration and resolution was found to be stronger for Latino adolescent girls than boys. However, they also found that higher levels of familial ethnic socialization were significantly associated with a faster rate of growth for ethnic identity resolution among Latino adolescent boys. Umaña-Taylor and Guimond (2010) posited that the differential pattern in outcomes reflect significant gender differences in gender socialization expectations for females and males. Specifically, they purported that the expectation for female adolescents to remain close to the family and be carriers of the culture resulted in their increased cognizance of culture and stronger associations for ethnic identity exploration and resolution. Moreover, ethnic identity growth for male adolescents in the study were explained to be linked to the efforts their families took to socialize them about their ethnicity. Overall, these findings suggest that gender ideologies are an integral component of familial ethnic socialization among many Latina/o families, and may be significant pathways that shape ethnic identity development among Latina/o youth.

Gender Role Attitudes

The transition to adolescence is characterized by an intensification of gender role socialization whereby youth become more aware of familial expectations to adhere to culturally sanctioned gender roles from their families (Arnett, 2001; Hill & Lynch, 1983). Compared with other ethnic groups, many Latina/o families tend to have traditional views regarding gender, including distinct gender role expectations for men and women compared with other ethnic groups (Arciniega et al., 2008; Azmitia & Brown, 2002; Castillo et al., 2010). In the current study, we extend our conceptual framework to include two important culturally grounded gender role constructs: machismo (Arciniega et al., 2008), and marianismo (Castillo et al., 2010). Arciniega et al. (2008) operationalized machismo, which describes the beliefs and expectations regarding the role of Latino men in society, along two dimensions: (a) traditional machismo, which is a focus on Latino men’s independence, dominance over women, and hypermasculinity; and (b) caballerismo, which is a focus on more positive aspects of masculinity such as social responsibility, protection of the family, and emotional connectedness.

Marianismo, the counterpart of machismo, emphasizes the role of women as family- and home-centered. Castillo and Cano (2007) operationalized marianismo along five pillars: (1) the family pillar emphasizes a woman’s role in maintaining family cohesion; (2) the virtuous/chaste pillar describes how a Latina is expected to maintain her virginity until marriage; (3) the subordinate to others pillar reflects the belief that Latinas should show obedience and respect for the Latina/o hierarchical family structure; (4) the self-silencing to maintain harmony pillar describes the belief that Latinas should keep confrontation and discomfort to a minimum within interpersonal relationships; and (5) the spiritual pillar describes the belief that Latinas should be the spiritual leader of the family.

Thus far, studies have shown traditional machismo gender role attitudes to be linked with negative mental health outcomes, such as depression, anxiety, stress (Fragoso & Kashubeck, 2000), and emotional disconnectedness among Latino adolescent boys (Arciniega et al., 2008; Liang, Salcedo, & Miller, 2011; Syzdek & Addis, 2010). Conversely, caballerismo has been positively associated with affiliation and positive academic attitudes and educational goals (Piña-Watson, Lorenzo-Blanco, Dornhecker, Martinez, & Nagoshi, 2016). With regard to marianismo, the family and spiritual pillars have been theorized to reflect “positive aspects” of marianismo and have been correlated with academic motivation and achievement among Mexican-origin adolescent females (Rodriguez, Castillo, & Gandara, 2013). Conversely, the virtuous and chaste, subordinate to others, and self-silencing pillars have been theorized to reflect “negative aspects” of marianismo and have been associated with depression and poor academic outcomes among Latinas in late adolescence (Perez, 2011; Rodriguez et al., 2013).

The function of machismo and marianismo gender role attitudes in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development has not been empirically tested. However, an examination of these links may illuminate ways in which machismo and marianismo gender role attitudes serve as mechanisms by which messages about cultural knowledge, values, and expectations are linked to boys’ and girls’ engagement in ethnic-related practices and behaviors. In particular, familial ethnic socialization practices that foster “positive” gender role attitudes may be linked to positive ethnic identity development among Latina/o boys and girls. For example, Latino boys who are prepared by their family to be nurturing and responsible men (caballerismo), may remain close to their family, and may have a strong sense of purpose and connection with their ethnic culture and identity, fostering positive ethnic identity development. Similarly, Latina adolescent girls who are socialized to value the interdependence and spiritual support of family, may have a positive reference system for ethnic group knowledge, which may foster stronger ethnic identity development.

In contrast, familial ethnic socialization practices that foster “negative” gender role attitudes may cultivate weaker ethnic identity development. For example, in a study conducted by Sanchez (in press), the subordinate to others marianismo pillar, which reflects the expectation that Latina women prioritize the concern of others, was found to have a negative effect on how Mexican American preadolescent girls felt about their ethnic group membership. Overall, both familial ethnic socialization and gender role attitudes are family driven socialization processes that may shape the ethnic identity development among Latina/o adolescents.

Ethnic Identity Development

Ethnic identity development is an important aspect of normative development for ethnic minority adolescents (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). During early adolescence, youth begin to demonstrate increased sociocognitive maturity, such as the ability to understand how one’s ethnicity impacts one’s life and social experiences (Phinney & Ong, 2007; Umaña-Taylor, Yazedjian, & Bámaca-Gomez, 2004; Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). This process includes expanding one’s ethnic self-identification to include internalization of the collective values held by one’s ethnic group (Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, et al., 2014). Umaña-Taylor, Quintana, and colleagues (2014) conceptualized ethnic identity as a developmental process that has three distinct components: ethnic identity exploration (the degree to which individuals have examined and explored their ethnicity), ethnic identity resolution (the degree to which the individual has confirmed what their ethnic identity means to them), and ethnic identity affirmation (an individual’s feelings about their ethnic group membership). Both ethnic identity exploration and resolution are conceptualized as developmental markers of ethnic identity, while ethnic identity affirmation is theorized to be an affective component (Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010).

Compared with older adolescents, younger adolescents may still rely heavily on parental guidance in constructing their ethnic identity (Umaña-Taylor, O’Donnell, et al., 2014). Thus, understanding the familial cultural and gender context within which Latina/o youth’s lives are rooted is important in understanding ethnic identity development among Latina/o youth (Umaña-Taylor, O’Donnell, et al., 2014).

The Current Study

Utilizing the integrative model as a theoretical framework (Garcia Coll et al., 1996), a central goal of this study was to better understand the function of gender role attitudes in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin preadolescents. Central to our conceptual model is an examination of familial ethnic socialization, which lays the foundation for understanding how familial cultural processes shape ethnic identity development among Latina/o youth. In addition, we extend the integrative model to include two indicators of adaptive culture, gender role attitudes (machismo and marianismo) and ethnic identity development. We specifically focus on Mexican-origin youth, because they are the largest and fastest growing Latina/o subgroup in the United States (Ennis, Ríos-Vargas, & Albert, 2011).

We first examine whether familial ethnic socialization directly predicts machismo gender role attitudes among Mexican-origin boys. We hypothesize that familial ethnic socialization will be predictive of both traditional machismo and caballerismo gender role attitudes. We also examine whether familial ethnic socialization directly predicts marianismo gender role attitudes among Mexican-origin girls. We hypothesize that familial ethnic socialization messages will be predictive of the five pillars of marianismo beliefs (family, virtuous/chaste, subordinate to others, self-silencing, and spiritual pillars, respectively).

Second, we examine machismo and marianismo gender role attitudes as potential mediators in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development for Mexican-origin boys and girls. We hypothesize that “positive” machismo gender role attitudes (caballerismo) will be a pathway that links familial ethnic socialization to stronger ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin adolescent boys. We also hypothesize that “positive” marianismo gender role attitudes (e.g., family and spiritual pillars) will be linked with stronger ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin girls. Conversely, we hypothesize that “negative” machismo and marianismo attitudes will be pathways that link familial ethnic socialization processes to lower levels of ethnic identity development. Among Mexican-origin boys, we hypothesize that those who are socialized by their family to be dominant over women and to value hypermasculinity (machismo) will report weaker ethnic identity development. Similarly, we hypothesize that Mexican-origin girls who endorse subordinate to others and self-silencing marianismo beliefs will report less developed ethnic identity development.

Method

Design and Selection

During the 2014–2015 academic year, a middle school serving sixth through eighth grades in the Southwest was identified for youth participant recruitment. This school was selected because it enrolls from primarily low-income Latino families, most of whom live within walking distance from the school, with a student body over 90% Latino, primarily of Mexican descent.

Participants

Of the 532 students approached to participate in the study, 90% volunteered to complete the survey provided written parental/guardian consent to participate in the study. The initial sample consisted of 479 students. Of this original sample, 9% (n = 43) identified as a racial/ethnic group other than Latina/o and were not included in the analysis. In addition, another 1% (n = 6) of Latina/o participants were not included in the analysis because of more than 90% missing data on the battery of surveys (Allison, 2001). Thus, the analysis presented includes a sample of 438 ethnically self-identified Mexican-origin middle school students, of which 55.3% (n = 242) were male. The participants ranged from 11 to 14 years of age (M = 12.58 years, SD = 1.02). Thirty-two percent of the participants (n = 140) were in the sixth grade, 33% (n = 145) were in the seventh grade, and 35% (n = 152) were in the eighth grade.

Of the total participant pool, 11.2% (n = 49) were first generation (were not born in the United States); of these, 8% (n = 4) reported having lived in the United States for 1–3 years, 12% (n = 6) for 4–7 years, 61% (n = 30) for 8–12 years, and 10% (n 5) for 12 or more years; 64.2% (n = 281) were second generation (i.e., born in the United States to immigrant parents); 13.5% (n = 59) were third generation; and 11.2% (n = 49) were fourth generation or beyond.1 Socioeconomic status (SES) was determined based on participant enrollment addresses provided by school records to obtain census track information related to neighborhood indices of SES (e.g., percentage of homeowners) and eligibility for the free lunch program. Approximately 98%–99% were considered socioeconomically disadvantaged based on their enrollment addresses, and over 95% were eligible for the free lunch program.

Procedure

The study received full institutional review board approval from the authors’ home institution and the participating school district prior to the recruitment of participants. The school counselors worked closely with the first author on participant recruitment and obtaining parental consent. Specifically, the head counselor identified specific advisory classroom periods when participants could be recruited, and these classrooms were visited by the primary researcher to explain the study and distribute parental consent forms (written in English and in Spanish). The consent forms were collected by the school counselors in their advisory periods and given to the primary researcher approximately 2 weeks prior to survey administration. All survey administration was done in the fall of 2014 during periods designated by the school counselors. Surveys were available in English and Spanish, and students were asked for their language preference before filling out the survey. Only seven students requested to fill the form out in Spanish. Participants were reminded that the questionnaire was voluntary and confidential and were then asked to sign informed assent forms. In addition, participants were also encouraged to ask for assistance at any point during the survey and research assistants were available to read the questionnaires aloud in English or Spanish to ensure clarity and accuracy. The survey time ranged from 30 to 35 min. Upon completion, participants were given a $5 gift card.

Data Analytic Strategy

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was first used to investigate the factor structure of the Familial Ethnic Socialization, Machismo, Marianismo, and Ethnic Identity measures to be used in the analyses of the conceptual models for girls and boys. Observed variable path analysis was then used to examine the familial ethnic socialization and gender role relationships among girls and boys separately. The indirect effects in the path models for boys and girls were also evaluated using bootstrap analyses with 10,000 sample draws and bias-corrected SEs (Preacher & Hayes, 2008). Maximum likelihood robust (MLR) estimation was used when analyzing the CFA models because the response options are ordinal. Maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was used when analyzing the observed variable path models. Mplus software (version 7.4; Muthén & Muthén, 1998–2015) was used for all of the analyses.

Model fit information for all of the tested CFA models is presented in Table 1. As suggested by Kline (2015), model fit of the CFA and observed variable path models was assessed with the chi-square test of model fit (χ2), the comparative fit index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI), the standardized root mean-square residual (SRMR), and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its corresponding 90% confidence interval (CI). Ideally, a nonsignificant chi-square test denotes adequate fit of the model to the data. CFI and TLI values equal to or greater than .90 traditionally denote adequate model fit. SRMR values of .05 suggest good fit, while values ranging between .05 and .10 suggest acceptable fit (Hu & Bentler, 1998). RMSEA values less than or equal to .05 suggest close fit while values ranging between .05 and .08 suggest adequate fit. Furthermore, model fit is deemed acceptable if the 90% CI associated with the RMSEA falls below or contains a value of .05 (Browne & Cudeck, 1993).

Table 1.

Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) Results for Girls and Boys

| CFA model | χ2 | df | TLI | CFI | RMSEA (90% CI) | SRMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Girls | ||||||

| Familial Ethnic Socialization Measure | ||||||

| Original two-factor correlated | 177.37* | 53 | .79 | .83 | .11 (.09, .13) | .07 |

| Modified two-factor correlated | 32.98* | 19 | .95 | .96 | .06 (.02, .10) | .04 |

| One-factor | 31.91* | 20 | .96 | .97 | .06 (.01, .09) | .04 |

| SB-Δχ2(1) between one-factor and modified two-factor model = 2.55, p > .05 | ||||||

| Marianismo Beliefs Scale | ||||||

| Five-factor correlated | 269.53* | 160 | .84 | .87 | .06 (.05, .07) | .08 |

| Three-factor correlated | 109.34* | 62 | .88 | .91 | .06 (.04, .08) | .07 |

| Modified three-factor correlated | 78.99* | 51 | .92 | .94 | .05 (.03, .07) | .06 |

| Ethnic Identity Scale—Brief Form | ||||||

| Two-factor correlated | 11.83 | 8 | .96 | .98 | .05 (.00, .11) | .03 |

| Boys | ||||||

| Familial Ethnic Socialization Measure | ||||||

| Original two-factor correlated | 137.74* | 53 | .90 | .92 | .08 (.07, .10) | .05 |

| Modified two-factor correlated | 57.46* | 19 | .90 | .93 | .09 (.07, .12) | .04 |

| One-factor | 56.67* | 20 | .91 | .94 | .09 (.06, .11) | .04 |

| SB-Δχ2(1) between one-factor and modified two-factor model = 2.18, p > .05 | ||||||

| Machismo measure | ||||||

| Two-factor uncorrelated | 282.18* | 170 | .88 | .90 | .05 (.04, .06) | .08 |

| Machismo: One-factor | 61.72* | 35 | .92 | .94 | .06 (.03, .08) | .05 |

| Caballerismo: One-factor | 55.53* | 35 | .94 | .95 | .05 (.02, .07) | .05 |

| Ethnic Identity Scale—Brief Form | ||||||

| Two-factor correlated | 5.12 | 8 | 1.02 | 1.00 | .00 (.00, .05) | .03 |

Note. TLI = Tucker-Lewis Index; CFI = comparative fit index; RMSEA = root mean squared error of approximation; CI = confidence interval; SRMR = standardized root mean-square residual.

p < .05.

In cases of poor model fit, modification indices (MIs) were examined to identify potential sources of model misspecification. MIs provide information about what may be added (e.g., a direct effect or correlation between variables) to a model to significantly improve the fit of the model using an estimated change in the chi-square statistic (Satorra, 1989; Sörbom, 1989). Theoretically reasonable parameters associated with a large MI value could then be evaluated as to whether they should be added to the model. MIs can also suggest model misspecification in terms of identifying poorly functioning items/variables. For example, in a CFA, large MIs associated with an item may suggest that it should also be allowed to load on a secondary factor, indicating potential misspecification of the model or misunderstanding of the item if the intention is to model distinct but related constructs (Saris, Satorra, & Sörbom, 1987).

Given the overwhelming representation of low-income status of participants, we did not assess for students’ self-reported SES and did not include SES in our analyses. However, we controlled for language acculturation and immigrant generation, given that both are important contextual acculturative processes associated with familial ethnic socialization, gender role attitudes, and ethnic identity development (Perreira, Harris, & Lee, 2006; Schwartz, Zamboanga, & Jarvis, 2007; Zayas, Bright, Alvarez-Sánchez, & Cabassa, 2009). In particular, language fluency (Spanish and English) is an indicator of one’s link to their culture or their family’s culture of origin (Perreira et al., 2006; Zayas et al., 2009). Among Latina/o youth, higher language acculturation may lead less family communication and cohesion, and a disconnect from Latina/o cultural values, including traditional gender role expectations (Piña-Watson et al., 2016). Similarly, immigrant generation may also influence familial ethnic socialization processes for Latina/o youth, whereby the frequency of racial-ethnic socialization practices may be higher among families that recently migrated versus those who have been in the United States for a long time (Schwartz, Unger, Zamboanga, & Szapocznik, 2010; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004). Thus, in the current study, we controlled for both language acculturation and immigrant generation to allow for the examination of the unique contribution of familial ethnic socialization processes and gender role attitudes and their effect on ethnic identity development in preadolescent Mexican-origin youth.

Measures

Familial ethnic socialization.

A 12-item version of the Familial Ethnic Socialization Measure (FESM; Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) was used to measure the extent to which participants perceived that their families promoted and educated them respective to their ethnic/cultural background. The overt ethnic socialization subscale consisted of 5-items that assessed instances where adolescents’ families were intentionally socializing their children via direct communication (e.g., “My family discusses the importance of knowing about my ethnic/cultural background). The covert ethnic socialization subscale consisted of 7-items that examined occasions when families were not intentionally socializing adolescents on their ethnicity, but were indirectly doing so via activities or décor (e.g., “Our home is decorated with things that reflect my ethnic/cultural background”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale, ranging from 1 = not at all to 5 = very much. The score is calculated either as (a) the mean of items on each subscale, or (b) the mean of the scale as a whole. Higher scores indicated higher levels of familial ethnic socialization.

A two-factor (overt and covert) correlated structure has been previously supported for the FESM. Thus, a two-factor correlated CFA was conducted on the responses to the FESM to evaluate the factor structure in the sample of boys and girls separately. The originally proposed two-factor model did not fit well in either sample. MIs were examined to identify possible model misspecifications which identified the same four items for the girls and boys as cross-loading on the other factor. After deleting the four items (i.e., 3, 6, 8, and 12), the two-factor correlated model fit the data acceptably in both samples (Table 1). However, the correlation between overt and covert factors was greater than .95 for both girls and boys. A one-factor model was analyzed and compared with the two-factor correlated model using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test (Satorra & Bentler, 1994), which suggested that overt and covert factors were not distinct factors. The one-factor model did not fit the data significantly worse than the two-factor model. Thus, the eight items retained on the FESM were averaged and used in the observed variable path analysis, representing a total familial ethnic socialization variable. Cronbach’s alpha for the revised 8-item FESM used in the current study is .89 for male participants and .86 for female participants. It must be noted that because a two-factor solution of the FESM was originally proposed by Umaña-Taylor and Fine, we also examined the observed variable path analysis using overt and covert variables (with the four cross-loading items removed). We discuss the overt and covert FESM comparison models in the Results section in order to evaluate the potential theoretical implications.

Machismo.

The Machismo Measure (MM; Arciniega et al., 2008) is a 20-item measure used to assess the extent to which Latino males identify with two separate components associated with the machismo construct: traditional machismo (e.g., dominance over women and restricted emotionality; “It is important not to be the weakest man in the group”) and caballerismo (e.g., to respect and responsibility to the family; “Men hold their mothers in high regard”). Items were rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The score is calculated as the mean of items in each subscale. Higher scores indicate higher adherence to traditional machismo/caballerismo beliefs.

A two-factor, uncorrelated structure has been suggested for the MM in Latino populations (Arciniega et al., 2008). The two-factor, uncorrelated model fit the data marginally well. One-factor models analyzed separately for Machismo and Caballerismo fit the data well (Table 1). Thus, the 10 items on the Machismo scale were aggregated and the 10 items on the Caballerismo scale were averaged to use as two observed variables in the corresponding path analysis. Cronbach’s alpha for the current study is .82 for traditional machismo and .86 for caballerismo for the sample of boys.

Marianismo.

The Marianismo Beliefs Scale (MBS; Castillo et al., 2010) was used to measure the extent to which a Latina female believes in and practices the gendered cultural values reflective of the construct of marianismo. Five subscales comprise the MBS: family pillar (e.g., “It is a mother’s job to keep the family together”); virtuous and chaste (e.g., “Women should remain virgins until marriage”); subordinate to others (e.g., “Women should follow what men say, even when they don’t agree”); silencing self to maintain harmony (e.g., “A woman should not talk to her man about what she needs from him”); and, spiritual pillar (e.g., “A woman should be the spiritual leader of the family”). The 24 items are rated on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The score is calculated either as (a) the mean of items in each subscale, or (b) the mean of the scale as a whole. Higher scores indicate a higher affinity to marianismo beliefs.

A five-factor, correlated structure has been suggested for the MBS in previous research with Latina populations (Castillo et al., 2010). The five-factor, correlated structure of the MBS did not fit the data for the girls adequately (Table 1). The MIs suggested that several items intended to load only on the spiritual (i.e., 19 and 20) and silencing factors (i.e., 14, 15, 16, and 18) cross-loaded onto other factors not originally hypothesized. Deleting these items resulted in eliminating the spiritual and silencing factors because of fewer than two items left loading on their respective factor. Thus, a three-factor, correlated factor structure was analyzed which fit the data adequately. Examination of the MIs suggested that Item 8 cross-loaded. After removing this item, the three-factor correlated model fit the data adequately (Table 1). The items underlying the measurement of each factor were averaged into three variables and used as proxies for their respective factor. For the current study, Cronbach’s alpha for the family, virtuous/chaste, and subordinate factors was .70, .73, and .82, respectively, for the sample of girls.

Ethnic identity.

The Ethnic Identity Scale—Brief Form (EISB; Douglass & Umaña-Taylor, 2015) is a nine-item measure that was used to assess participants’ ethnic identity. The EISB consists of three subscales, including ethnic identity exploration (three items; e.g., “I only hang out with other kids from my own race/culture”), resolution (two items; e.g., “I know what my ethnicity means to me”) and affirmation (four items; e.g., “I feel good about my racial/cultural background”). Items were scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 4 = strongly agree. The scores are calculated using the mean of items of each subscale. Higher scores indicated higher levels of ethnic identity exploration, resolution, and affirmation. Cronbach’s alphas in the current study for ethnic identity resolution are .71 and .74 for male and female participants, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha associated with ethnic identity affirmation is .78 for both male and female participants. Cronbach’s alphas for ethnic identity exploration are .51 and .26 for male and female participants, respectively. Because of the low reliability for the exploration subscale, we did not include this variable in our analysis. This decision was based on the recommendation by Kline (2015) that measures be internally consistent when used as observed variables in an analysis. The resulting two-factor correlated CFA model fit the data well for the sample of girls and boys (Table 1).

Language acculturation.

Three items from the Language Acculturation Scale for Mexican Americans (Deyo, Diehl, Hazuda, & Stern, 1985) were used to measure language acculturation (e.g., How often does your family speak a language (other than English)?). Item responses ranged from 1 (not at all) to 3 (all the time), with higher scores indicating greater acculturation. Cronbach’s alpha for the acculturation inventory for the current study is .78 for male participants and .72 for female participants.

Demographic questionnaire.

The demographic questionnaire requested the participants to indicate their age, gender, race, ethnicity, grade level, and generation in the United States.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

Descriptive statistics (i.e., frequencies, skewness, kurtosis) were examined to check the data for normality, input errors, and outliers. No unusual occurrences were found in the data. Less than six percent of the data were missing among participants on any one variable. The amount of missing data for the study variables of interest was not related to any of the demographic variables, including gender or acculturation. Because such a small amount of missingness was recorded among the data, the estimates should not be biased (Allison, 2001). Pearson product–moment correlations and means and standard deviations of the main study variables for boys and girls are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

Table 2.

Zero-Order Correlations and Means and SDs for Study Variables for Mexican-Origin Girls (N = 196)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1. Familial ethnic socialization | 1 | 3.37 | .91 | |||||

| 2. Ethnic identity resolution | .30** | 1 | 3.22 | .72 | ||||

| 3. Ethnic identity affirmation | .14* | .31** | 1 | 3.32 | .79 | |||

| 5. Family pillar | .12 | .16* | −.04 | 1 | 3.32 | .50 | ||

| 6. Virtuous/chaste pillar | .15* | .04 | .00 | .34** | 1 | 2.98 | .72 | |

| 7. Subordinate to others pillar | .09 | −.06 | −.11 | −.14* | .07 | 1 | 1.87 | .68 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Table 3.

Zero-Order Correlations and Means and SDs for Study Variables for Mexican-Origin Boys (N = 242)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| 1. Acculturation | 1 | 2.56 | .49 | |||||

| 2. Familial ethnic socialization | .16* | 1 | 3.23 | .99 | ||||

| 3. Ethnic identity resolution | .13 | .30** | 1 | 3.20 | .69 | |||

| 4. Ethnic identity affirmation | .14* | .18** | .25** | 1 | 3.25 | .78 | ||

| 5. Machismo | −.04 | .05 | −.08 | −.29** | 1 | 2.36 | .55 | |

| 6. Caballerismo | .02 | .25** | .41** | .22** | .07 | 1 | 3.30 | .54 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

Path Analysis of Familial Ethnic Socialization Models for Girls and Boys

The theoretical model for both the girls and boys were analyzed separately. The error variances associated with the subscales from the same scale were allowed to covary in each of the models. Specifically, the residuals associated with the ethnic identity affirmation and resolution variables were allowed to covary in the model for both the girls and boys. Residuals associated with the Machismo and Caballerismo scales were not included in the model for the boys since the two factors are modeled not to covary in the CFA model. In addition, the residuals associated with the family pillar, virtuous/chaste pillar, and the subordinate to others variables were all allowed to covary in the model for the girls. To highlight the unique contribution of gender role attitudes in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development, acculturation and generational status (as three dummy coded variables using first generation as the reference group) were used as covariates (control variables) in the path models and are not illustrated in the models for simplicity.

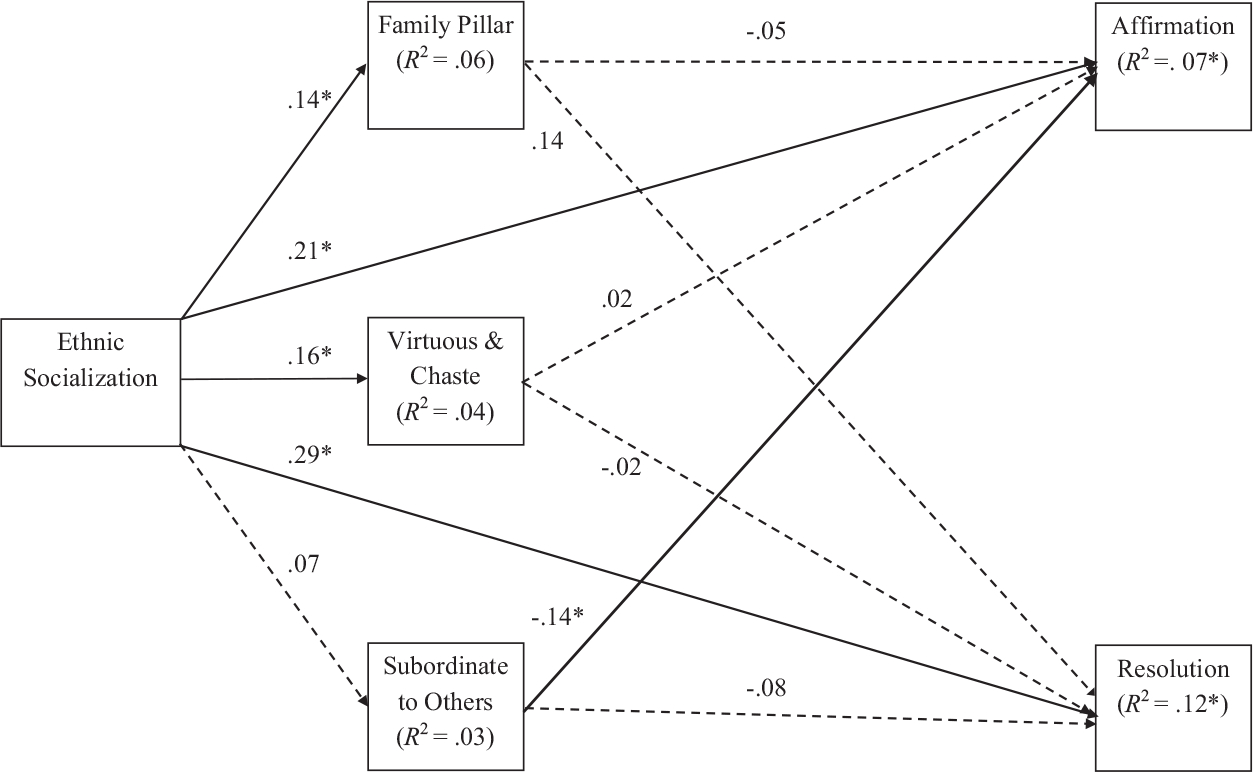

The model for the girls was just-identified and fit the data perfectly, χ2(0) = 0.0; TLI = 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: .00, .00; SRMR = .00. The model for the girls with standardized values are presented in Figure 1. Solid lines in the figures represent statistically significant relationships (p < .05), whereas dashed lines represent nonsignificant relationships. As illustrated in Figure 1, familial ethnic socialization had a significant and positive direct effect on family pillar beliefs, virtuous/chaste beliefs, ethnic identity affirmation and ethnic identity resolution. Endorsement of subordinate to others beliefs significantly and negatively predicted ethnic identity affirmation. The residual correlations are not illustrated in Figure 1 for simplicity. The residuals associated with the ethnic identity affirmation and resolution variables were significantly correlated (r = .45). The correlation between the residuals associated with the family pillar and the virtuous & chaste pillar (r = .41) was statistically significant as was the correlation between the residuals associated with the family pillar and the subordinate to others pillar (r = −.14). The correlation between the residuals associated with the virtuous/chaste pillar and the subordinate to others pillar was not statistically significant (r = .01).

Figure 1.

Ethnic socialization model for girls. * p < .05.

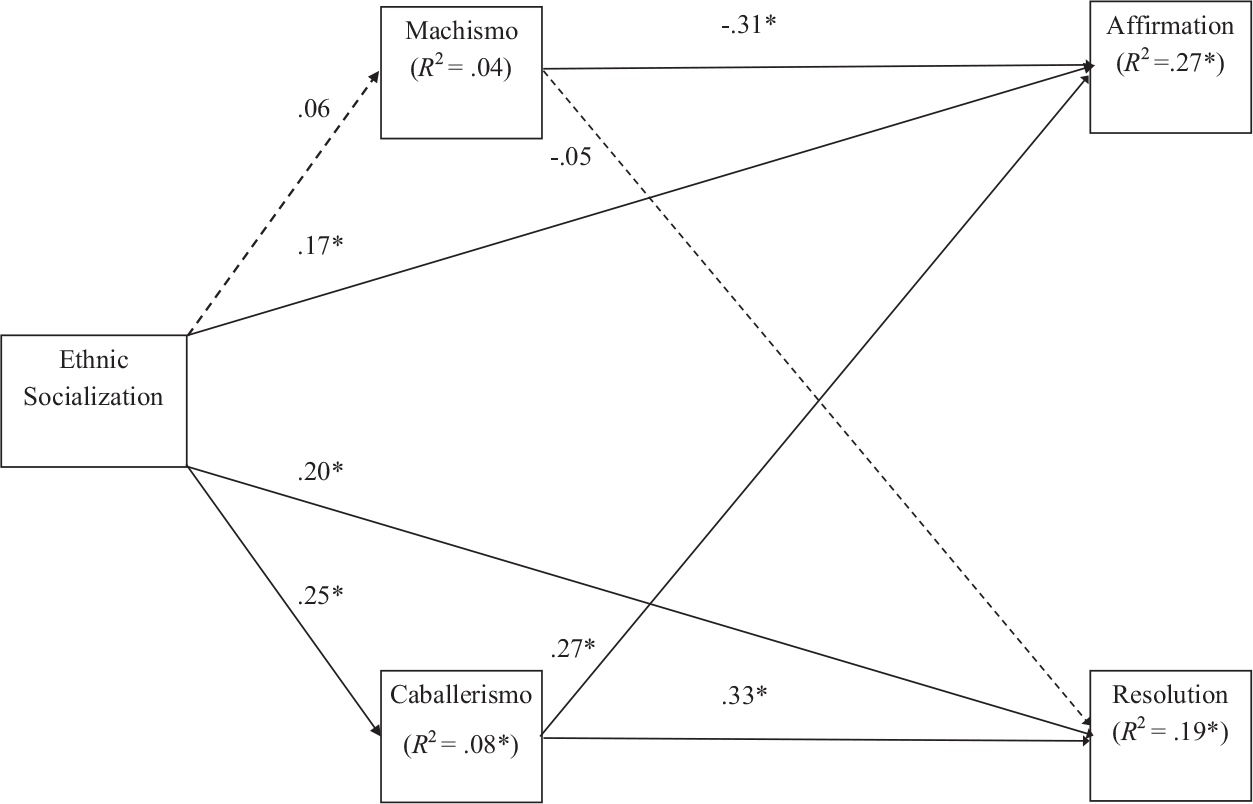

The model for the boys fit the data very well, χ2(1) = .73, p > .05; TLI = 1.05; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: .00, .16); SRMR = .01. The model for the boys with standardized values are presented in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 2, familial ethnic socialization significantly and positively predicted caballerismo, ethnic identity affirmation, and ethnic identity resolution. Traditional machismo significantly and negatively predicted ethnic identity affirmation. Caballerismo was a significant and positive predictor of ethnic identity affirmation and resolution. Again, the residual correlations are not illustrated in Figure 2 for simplicity. The residuals associated with the ethnic identity affirmation and resolution variables were not significantly correlated (r = .30) for the boys.

Figure 2.

Ethnic socialization model for boys. * p > .05.

As previously indicated, these same models were also analyzed with separate overt and covert variables from the modified FESM. The overt and covert FES model for the girls was just identified and fit the data perfectly, χ2(0) = 0.0; TLI 1.00; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: .00, .00); SRMR = .00. Similar to the single FES variable model, overt ethnic socialization had a significant and positive direct effect on ethnic identity affirmation and ethnic identity resolution, but did not significantly predict virtuous/chaste beliefs. Covert ethnic socialization did not significantly predict any of the variables in the model. Endorsement of subordinate to others beliefs still significantly and negatively predicted ethnic identity affirmation. The residuals associated with overt and covert FES significantly correlated (r = .75).

The overt and covert FES model for the boys fit the data well, χ2(1) = 0.92, p > .05; TLI = 1.00; CFI = 1.02; RMSEA = .00 (90% CI: .00, .17); SRMR = .01. Similar to the single FES variable model, overt ethnic socialization significantly and positively predicted caballerismo, ethnic identity affirmation, and ethnic identity resolution. Covert ethnic socialization did not significantly predict any of the variables in the model. Traditional machismo still significantly and negatively predicted ethnic identity affirmation. Caballerismo was still a significant and positive predictor of ethnic identity affirmation and resolution. The residuals associated with overt and covert FES were significantly correlated (r = .86) for the boys.

The overt and covert FES model for the girls and boys revealed subtle differences as compared with the single FES variable model, with overt ethnic socialization tending to demonstrate more explanatory influence than covert ethnic socialization. Nonetheless, the extremely high correlation (>.95) that was found between the overt and covert factors in the CFA implies that they are not necessarily distinct factors. Thus, we decided to retain the more parsimonious single FES variable model. Implications for the use of the FESM with preadolescent populations is discussed in the Discussion section.

Analyses of Indirect Effects

Although the data were collected at a single time point and not longitudinally, indirect effects in the observed variable path models were evaluated to help elucidate potential mediating relationships that may be further examined in subsequent longitudinal studies with this population. The temporal order of the variables in the path models, as previously described, is grounded in theory. Although the models attempt to represent the chronological relationships that would be observed with longitudinal data, causality should not be inferred from the analyses of indirect effects.

None of the specific indirect effects were identified as statistically significant in the model for the girls. Two specific indirect effects were identified as statistically significant for the boys. The indirect relationship between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity affirmation via caballerismo was statistically significant. Similarly, the indirect relationship between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity resolution via caballerismo was statistically significant. Table 4 presents the statistically significant unstandardized indirect effects with corresponding 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals. Corresponding unstandardized direct and total effects are also presented. In addition, the standardized effect size associated with the indirect effect is presented in Table 4 and may be interpreted similarly to Cohen’s d effect size measure (Cohen, 1988). It is calculated by taking the product of the unstandardized direct effect coefficients involved in the indirect effect and dividing it by the standard deviation associated with the outcome variable (MacKinnon, 2008). Values of .2, .5, and .8 represent small, moderate, and large effect sizes, respectively. Thus, small effect sizes were associated with the statistically significant indirect effects (Table 4).

Table 4.

Summary of Statistically Significant Unstandardized Indirect Effects (With Corresponding 95% Bias-Corrected Bootstrapped Confidence Intervals), Direct Effects, and Total Effects for the Boys

| Association | Direct effect | Indirect effect (95% B-CB CI) | Total effect | Indirect effect size |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| FES, EI-Aff | ||||

| FES → Cab → EI-Aff | .11* | .05* (.02, .09) | .16 | .07 |

| FES, EI-Res | ||||

| FES → Cab → EI-Res | .12* | .06* (.03, .11) | .18 | .08 |

Note. B-CB CI = bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence interval; FES = familial ethnic socialization; EI-Aff = ethnic identity affirmation; Cab = caballerismo; EI-Res = ethnic identity resolution.

p < .05.

Discussion

Utilizing García Coll and colleagues’ (1996) integrative model as a theoretical framework, a central goal of this study was to better understand the function of gender role attitudes in the link between familial ethnic socialization, and ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin preadolescents. In particular, a focus on familial ethnic socialization provided a theoretical foundation for understanding how cultural processes shape gender role attitudes and ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin youth (Parke & Buriel, 1997). In addition, we incorporated two multidimensional gender role constructs, marianismo and machismo, which allowed for movement beyond one-dimensional gender role stereotypes of Latinas/os to provide a more nuanced account of the gendered mechanisms by which familial ethnic socialization may shape ethnic identity development.

Findings for Mexican-Origin Boys

First, our findings showed that, among Mexican-origin adolescent boys, familial ethnic socialization was linked with healthier gender role expectations, such as responsibility, nurturance and emotional connectedness (caballerismo). Traditional machismo, on the other hand, was not linked to familial ethnic socialization. This may be because caballerismo themes of chivalry, respect, and responsibility are focused on more frequently within the home, while hypermasculine socialization of machismo may occur with greater intensity in youth social networks and media scripts (Mosher & Tomkins, 1988). Familial ethnic socialization was also shown to be linked to stronger ethnic identity affirmation and ethnic identity resolution. In addition, findings showed that caballerismo gender roles mediated the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity affirmation and resolution. These findings suggest that Mexican-origin boys may derive a greater sense of pride in their ethnic group because of their family’s transmission of gender role values related to social responsibility, protection of the family, and emotional connectedness. This may lead Mexican-origin adolescent boys to be more aware of their own emotions and the emotions of others around their ethnicity, and this may be associated with a greater sense of clarity about what their ethnicity means to them, as well as positive affect toward their ethnicity (Arciniega et al., 2008; Glass & Owen, 2010).

Overall, these preliminary findings make a significant contribution to the literature by illustrating that positive aspects of masculinity, such as honor, respect, dignity, and familismo are significantly associated with positive ethnic identity development among Latino males. Moreover, our examination of the indirect effect of positive gender role attitudes and ethnic identity offers a unique and powerful context for the translation between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin preadolescent boys. Although the marriage of distinct gender role expectations and familial ethnic socialization is often implied in the literature, few studies have empirically examined this relationship explicitly (Cupito, Stein, & Gonzalez, 2015; Umaña-Taylor & Guimond, 2010), and to our knowledge, none have done so among Mexican-origin early adolescent males.

Findings for Mexican-Origin Girls

Among Mexican-origin adolescent girls, findings provide support for the direct link between familial ethnic socialization and positive ethnic identity development. However, our findings provide only partial support for the link between familial ethnic socialization and marianismo gender role attitudes. In particular, findings showed that familial ethnic socialization was significantly and positively linked with family and virtuous/chaste marianismo beliefs. The family pillar is based on the tenet of familismo and emphasizes the importance of a woman’s role in maintaining family cohesion (Castillo et al., 2010). It is theorized to reflect a positive aspect of marianismo, as the interdependence of family provides Latina youth with extended family networks, social support, and a reference system for attitudes and beliefs that may safeguard against early initiation of risk behaviors (Burris, Smith, & Carlson, 2009; Guilamo-Ramos, Bouris, Jaccard, Lesesne, & Ballan, 2009; Sanchez, Whittaker, Hamilton, & Zayas, 2016).

The virtuous/chaste pillar is based on the tenet of respeto and describes how a Latina is expected to maintain the family honor and avoid bringing shame to the family by “respecting her body” and maintaining her virginity until marriage (Garcia, 2012). The expectation that Latina females remain virtuous and chaste is strongly reinforced through strict supervision of their families (e.g., girls stay at home and close to their family; Arredondo, Gallardo-Cooper, Delgado-Romero, & Zapata, 2014). For example, the implicit deep-rootedness of the value of virtuousness and chastity is infused into many Latina/o cultural practices, including home décor (i.e., statues of the Virgin Mary) and the informal supervision and monitoring of female adolescents as they go through puberty (e.g., chaperonas; Arredondo et al., 2014; Knight et al., 2011). This may reinforce sexual silence among Latina adolescents and limit open communication with parents and family about identity and health related topics, which may lead to negative health outcomes.

The subordination to others marianismo pillar was not linked to familial ethnic socialization, however, it was significantly and negatively linked to ethnic identity affirmation. This suggests that the deference to the Latina/o hierarchical family structure, particularly to men and one’s elders, was associated with less positive feelings about one’s ethnic group membership among Mexican-origin girls. The subordinate to others pillar has been theorized to reflect a “negative aspect” of marianismo and has been significantly associated with depression and poor academic outcomes among Latina adolescent females (e.g., dropping out of high school; Perez, 2011; Rodriguez et al., 2013). One rationale for the negative link between subordinate to others and ethnic identity affirmation for girls may stem from a pressure to assume home-centered activities, such as helping out with childcare, cleaning, and other domestic responsibilities (Cupito et al., 2015). These domestic obligations may create competing demands between academic and social interests, which in turn may have a negative effect on how Latina girls feel about their ethnic group membership.

It is interesting to note, and contrary to our hypotheses, that none of the marianismo pillars mediated the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development. This may be due in part to the measurement of marianismo. For example, the original five-factor structure as demonstrated by Castillo et al. (2010) did not fit the data from the sample of Mexican-origin preadolescent girls well; only three of the original five marianismo pillars were examined in the current study. Similar measurement problems with the MBS were also found in a study conducted by Sanchez et al. (2016) that examined the link between marianismo beliefs and sexual risk behaviors among a sample of Mexican-origin preadolescent girls. Although the MBS was originally developed for Latina adult women, and has shown good psychometric properties with high school Latina/o adolescents, future research should modify the MBS and use specific terms that would be appropriate for younger adolescent samples.

Limitations

The results of the current study must be interpreted in the context of a few limitations. First, this study was correlational, and statistical analysis used to explore the relations between familial ethnic socialization, gender roles, and ethnic identity dimensions does not establish causation. Second, given the cross-sectional nature of the study, we cannot draw definitive conclusions about the directionality of the relationships. Third, the current study utilized self-report measures of familial ethnic socialization, gender role attitudes, and ethnic identity, which may not fully or accurately capture their experiences. Fourth, our sample consisted of mostly second generation Mexican-origin preadolescents living in predominantly Mexican-origin communities in the Southwest, and their experiences may differ from Mexican-origin adolescents living in predominantly White settings. Fifth, the original five-factor structure of the MBS scale demonstrated by Castillo et al. (2010) did not fit the data from the sample of Mexican-origin preadolescent girls well. Similarly, the original two-factor structure of the FES scale (Umaña-Taylor & Fine, 2004) and the three factor structure of the EISB scale (Douglass & Umaña-Taylor, 2015) had similar model misfit. The deletion of items and the omission of the EISB exploration subscale was done in order to stay as true as possible with the original intention of the FES, MBS, and EISB factor structures; however, these analyses became exploratory in nature because of model misfit.

Implications for Future Research

The current study has important implications for future research. Given that the original five-factor structure as demonstrated by Castillo et al. (2010) did not fit the data from the sample of Mexican-origin preadolescent girls well, future research should examine potential differences in the MBS factor structure previously established in older Latina populations. Similar misfit was detected within the FES and EISB. This misfit could be because of differences in the populations in which these scales were developed (e.g., preadolescents vs. adolescents, more recent immigrant generation vs. later immigrant generation). It may be that early adolescents have limited vocabulary surrounding familial socialization practices, gender role ideologies, and ethnic identity development, which may have restricted their understanding of items on the FES, MBS, and EISB. However, among older adolescent populations, the various factors of the FES, MBS, and EISB may become more distinct because of advances in overall cognitive, social and ego identity development. Further research should take caution to ensure the appropriate measurement of these constructs with early adolescent samples.

The results of this study have important implications for educators and counselors working with early adolescent Mexican-origin youth. Educators and counselors should be familiar with the multidimensional nature of machismo and marianismo gender role ideologies, and how certain attitudes are shaped by familial ethnic socialization and may impact ethnic identity development. Findings identified specific “positive” components of machismo (e.g., caballerismo) that may indirectly link familial ethnic socialization to positive ethnic identity development. Findings also identified that “negative” components of marianismo (e.g., subordination to others) were directly linked to poor ethnic identity development. Thus, counselors should provide gender-specific and culturally responsive services that include positive and empowering aspects of gender roles, and that challenge maladaptive gender role attitudes (Nuñez et al., 2016). Thus far, interventions for adolescent boys aimed at lowering the endorsement of traditional masculinity ideologies have shown promising results (Claussen, 2016).

Conclusion

In sum, these findings provide preliminary evidence for the significant role of caballerismo gender role attitudes in the link between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development for Mexican-origin early adolescent boys. Our findings did not show support for the mediating link of marianismo in the relation between familial ethnic socialization and ethnic identity development in Mexican-origin early adolescent girls. This may be attributable, in part, to the poor fit of the overall MBS scale among the current early adolescent Mexican-origin sample. Overall, findings show the significant role that family socialization plays in the ethnic identity developmental processes for Mexican-origin early adolescent boys and girls. This study also underscores the importance of fostering positive aspects of machismo and marianismo, which have important links to ethnic identity development among Mexican-origin adolescents.

Footnotes

We used the U.S. Census criterion for categorizing generation status. First, we asked students which of their family members were the first to be born in the United States. Those students that indicated that they were not born in the United States were coded as “first generation.” Students who indicated that they were the first to be born in the United States were coded as “second generation.” Students who indicated that their parents were the first to be born in the United States were coded as “third generation.” Those who indicated that their grandparents were born in the United States were coded as “fourth generation,” and those who indicated that their great-grandparents were born in the United States were coded as “beyond fourth generation.”

References

- Allison PD (2001). Missing data (Vol. 136). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul I, Oyserman D, & Bybee D (2008). Racial-ethnic self-schemas and segmented assimilation: Identity and the academic achievement of Hispanic youth. Social Psychology Quarterly, 71, 302–320. 10.1177/019027250807100309 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arciniega GM, Anderson TC, Tovar-Blank ZG, & Tracey TJ (2008). Toward a fuller conception of Machismo: Development of a traditional Machismo and Caballerismo Scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 55, 19–33. 10.1037/0022-0167.55.1.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armenta BE, Knight GP, Carlo G, & Jacobson RP (2011). The relation between ethnic group attachment and prosocial tendencies: The mediating role of cultural values. European Journal of Social Psychology, 41, 107–115. 10.1002/ejsp.742 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ (2001). Adolescence and emerging adulthood. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. [Google Scholar]

- Arredondo P, Gallardo-Cooper M, Delgado-Romero E, & Zapata A (2014). Culturally responsive counseling with Latinas/os. Alexandria, VA: American Counseling Association. [Google Scholar]

- Azmitia M, & Brown JR (2002). Latino immigrant parents’ beliefs about the “path of life” of their adolescent children. Latino Children and Families in the United States, 77–106. [Google Scholar]

- Borrero NE, & Yeh CJ (2011). The multidimensionality of ethnic identity among urban high school youth. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 11, 114–135. 10.1080/15283488.2011.555978 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MW, & Cudeck R (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. In Bollen KA & Long JS (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 136–162). Newbury Park, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Burris JL, Smith GT, & Carlson CR (2009). Relations among religiousness, spirituality, and sexual practices. Journal of Sex Research, 46, 282–289. 10.1080/00224490802684582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, & Cano MA (2007). Mexican American psychology: Theory and clinical application. In Negy C (Ed.), Cross-cultural psychotherapy: Toward a critical understanding of diverse client populations (pp. 85–102). Reno, NV: Bent Tree Press Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo LG, Perez FV, Castillo R, & Ghosheh MR (2010). Construction and initial validation of the Marianismo Beliefs Scale. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 23, 163–175. 10.1080/09515071003776036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Claussen C (2016). The WiseGuyz Program: Sexual health education as a pathway to supporting changes in endorsement of traditional masculinity ideologies. Journal of Men’s Studies. Advance online publication. 10.1177/1060826516661319 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Cupito AM, Stein GL, & Gonzalez LM (2015). Familial cultural values, depressive symptoms, school belonging and grades in Latino adolescents: Does gender matter? Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 1638–1649. 10.1007/s10826-014-9967-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deyo RA, Diehl AK, Hazuda H, & Stern MP (1985). A simple language-based acculturation scale for Mexican Americans: Validation and application to health care research. American Journal of Public Health, 75, 51–55. 10.2105/AJPH.75.1.51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass S, & Umaña-Taylor AJ (2015). A brief form of the Ethnic Identity Scale: Development and empirical validation. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 15, 48–65. 10.1080/15283488.2014.989442 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis SR, Ríos-Vargas M, & Albert NA (2011). The Hispanic population: 2010. US Census Bureau: US Department of Commerce. Washington, DC: Economics and Statistics Administration. Retrieved from http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-04.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Fragoso JM, & Kashubeck S (2000). Machismo, gender role conflict, and mental health in Mexican American men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 1, 87–97. 10.1037/1524-9220.1.2.87 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia L (2012). Respect yourself, protect yourself: Latina girls and sexual identity. New York, NY: NYU Press. [Google Scholar]

- García Coll C, Lamberty G, Jenkins R, McAdoo HP, Crnic K, Wasik BH, & Vázquez García H (1996). An integrative model for the study of developmental competencies in minority children. Child Development, 67, 1891–1914. 10.2307/1131600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass J, & Owen J (2010). Latino fathers: The relationship among machismo, acculturation, ethnic identity, and paternal involvement. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 11, 251–261. 10.1037/a0021477 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guilamo-Ramos V, Bouris A, Jaccard J, Lesesne C, & Ballan M (2009). Familial and cultural influences on sexual risk behaviors among Mexican, Puerto Rican, and Dominican youth. AIDS Education and Prevention, 21(Suppl.), 61–79. 10.1521/aeap.2009.21.5_supp.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernández MM, Conger RD, Robins RW, Bacher KB, & Widaman KF (2014). Cultural socialization and ethnic pride among Mexican-origin adolescents during the transition to middle school. Child Development, 85, 695–708. 10.1111/cdev.12167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill JP, & Lynch ME (1983). The intensification of gender-related role expectations during early adolescence. In Brooks-Gunn J & Peterson AC (Eds.), Girls at puberty (pp. 201–228). New York, NY: Plenum Press. 10.1007/978-1-4899-0354-9_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, & Bentler PM (1998). Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparameterized model misspecification. Psychological Methods, 3, 424–453. 10.1037/1082-989X.3.4.424 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D (2003). Correlates of African American and Latino parents’ messages to children about ethnicity and race: A comparative study of racial socialization. American Journal of Community Psychology, 31, 15–33. 10.1023/A:1023066418688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes D, Witherspoon D, Rivas-Drake D, & West-Bey N (2009). Received ethnic-racial socialization messages and youths’ academic and behavioral outcomes: Examining the mediating role of ethnic identity and self-esteem. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 15, 112–124. 10.1037/a0015509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline R (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Knight GP, Berkel C, Umaña-Taylor AJ, Gonzales NA, Ettekal I, Jaconis M, & Boyd BM (2011). The familial socialization of culturally related values in Mexican American families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 913–925. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00856.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang CT, Salcedo J, & Miller HA (2011). Perceived racism, masculinity ideologies, and gender role conflict among Latino men. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 12, 201–215. 10.1037/a0020479 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP (2008). Introduction to statistical mediation analysis. New York, NY: Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Mosher DL, & Tomkins SS (1988). Scripting the macho man: Hypermasculine socialization and enculturation. Journal of Sex Research, 25, 60–84. 10.1080/00224498809551445 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO (1998–2015). Mplus user’s guide (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Nuñez A, González P, Talavera GA, Sanchez-Johnsen L, Roesch SC, Davis SM, . . . Gallo LC (2016). Machismo, marianismo, and negative cognitive-emotional factors: Findings from the hispanic community health study/Study of latinos sociocultural ancillary study. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 4, 202–217. 10.1037/lat0000050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parke RD, & Buriel R (1997). Socialization in the family: Ethnic and ecological perspectives. In Eisenberg N (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3. Social, emotional, and personality development (5th ed., pp. 463–552). New York, NY: Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Perez FV (2011). The impact of traditional gender role beliefs and relationship status on depression in Mexican American women: A study in self-discrepancies (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). College Station, TX: Texas A&M University. [Google Scholar]

- Perreira KM, Harris KM, & Lee D (2006). Making it in America: High school completion by immigrant and native youth. Demography, 43, 511–536. 10.1353/dem.2006.0026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phinney JS, & Ong AD (2007). Conceptualization and measurement of ethnic identity: Current status and future directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54, 271–281. 10.1037/0022-0167.54.3.271 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Piña-Watson B, Lorenzo-Blanco EI, Dornhecker M, Martinez AJ, & Nagoshi JL (2016). Moving away from a cultural deficit to a holistic perspective: Traditional gender role values, academic attitudes, and educational goals for Mexican descent adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 63, 307–318. 10.1037/cou0000133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Preacher KJ, & Hayes AF (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40, 879–891. 10.3758/BRM.40.3.879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raffaelli M, & Ontai LL (2004). Gender socialization in Latino/a families: Results from two retrospective studies. Sex Roles, 50, 287–299. 10.1023/B:SERS.0000018886.58945.06 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RE, Phinney JS, Masse LC, Chen YR, Roberts CR, & Romero A (1999). The structure of ethnic identity of young adolescents from diverse ethnocultural groups. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 19, 301–322. 10.1177/0272431699019003001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez KM, Castillo LG, & Gandara L (2013). The influence of marianismo, ganas, and academic motivation on Latina adolescents’ academic achievement intentions. Journal of Latina/o Psychology, 1, 218–226. 10.1037/lat0000008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Romero AJ, & Roberts RE (2003). Stress within a bicultural context for adolescents of Mexican descent. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 9, 171–184. 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D (in press). Examining marianismo gender role attitudes, ethnic identity, and substance use in Mexican American preadolescent girls. The Journal of Primary Prevention. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez D, Whittaker TA, Hamilton E, & Zayas LH (2016). Perceived discrimination and sexual precursor behaviors in Mexican American preadolescent girls: The role of psychological distress, sexual attitudes, and marianismo beliefs. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 22, 395–407. 10.1037/cdp0000066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saris WE, Satorra A, & Sörbom D (1987). The detection and correction of specification errors in structural equation models. In Clogg CC (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 105–129). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. 10.2307/271030 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A (1989). Alternative test criteria in covariance structure analysis: A unified approach. Psychometrika, 54, 131–151. 10.1007/BF02294453 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, & Bentler PM (1994). Corrections to test statistics and standard errors in covariance structure analysis. In Von Eye A & Clogg CC (Eds.), Latent variables analysis (pp. 399–419). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Unger JB, Zamboanga BL, & Szapocznik J (2010). Rethinking the concept of acculturation: Implications for theory and research. American Psychologist, 65, 237–251. 10.1037/a0019330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz SJ, Zamboanga BL, & Jarvis LH (2007). Ethnic identity and acculturation in Hispanic early adolescents: Mediated relationships to academic grades, prosocial behaviors, and externalizing symptoms. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 13, 364–373. 10.1037/1099-9809.13.4.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sörbom D (1989). Model modification. Psychometrika, 54, 371–384. 10.1007/BF02294623 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Supple AJ, Ghazarian SR, Frabutt JM, Plunkett SW, & Sands T (2006). Contextual influences on Latino adolescent ethnic identity and academic outcomes. Child Development, 77, 1427–1433. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00945.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Syzdek MR, & Addis ME (2010). Adherence to masculine norms and attributional processes predict depressive symptoms in recently unemployed men. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34, 533–543. 10.1007/s10608-009-9290-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Alfaro EC, Bámaca MY, & Guimond AB (2009). The central role of familial ethnic socialization in Latino adolescents’ cultural orientation. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 46–60. 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00579.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Fine MA (2001). Methodological implications of grouping Latino adolescents into one collective ethnic group. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 23, 347–362. 10.1177/0739986301234001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Fine MA (2004). Examining ethnic identity among Mexican-origin adolescents living in the United States. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 26, 36–59. 10.1177/0739986303262143 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Guimond AB (2010). A longitudinal examination of parenting behaviors and perceived discrimination predicting Latino adolescents’ ethnic identity. Developmental Psychology, 46, 636–650. 10.1037/a0019376 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, O’Donnell M, Knight GP, Roosa MW, Berkel C, & Nair R (2014). Mexican-origin early adolescents’ ethnic socialization, ethnic identity, and psychosocial functioning. The Counseling Psychologist, 42, 170–200. 10.1177/0011000013477903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Quintana SM, Lee RM, Cross WE, Rivas-Drake D, Schwartz SJ, . . . Study Group on Ethnic and Racial Identity. (2014). Ethnic and racial identity revisited: An integrated conceptualization. Child Development, 85, 21–39. 10.1111/cdev.12196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, & Updegraff KA (2007). Latino adolescents’ mental health: Exploring the interrelations among discrimination, ethnic identity, cultural orientation, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Adolescence, 30, 549–567. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2006.08.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Yazedjian A, & Bámaca-Gómez M (2004). Developing the ethnic identity scale using Eriksonian and social identity perspectives. Identity: An International Journal of Theory and Research, 4, 9–38. 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Umaña-Taylor AJ, Zeiders KH, & Updegraff KA (2013). Family ethnic socialization and ethnic identity: A family-driven, youth-driven, or reciprocal process? Journal of Family Psychology, 27, 137–146. 10.1037/a0031105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zayas LH, Bright CL, Alvarez-Sánchez T, & Cabassa LJ (2009). Acculturation, familism and mother-daughter relations among suicidal and non-suicidal adolescent Latinas. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 30, 351–369. 10.1007/s10935-009-0181-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]