Abstract

Lymphomas are the most common nonepithelial malignancy in the head and neck region. Among these, non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) is the most prevalent, and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common histologic subtype. NHL is known for its propensity for extranodal involvement, which can affect any anatomical location. The presence of perineural spread is frequently encountered in head and neck malignancies, including lymphomas. We report a case of a 40-year-old male with an enlarging infraorbital facial mass with associated erythema, pain, and paresthesia, which was subsequently found to be extranodal DLBCL with retrograde perineural spread along the infraorbital nerve.

Keywords: Lymphoma, Diffuse large B cell lymphoma, Extranodal, Premaxillary, Perineural

Introduction

Lymphomas are the third most common malignancy in the head and neck, constituting 5%-12% of all such malignancies [1,4]. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) accounts for the majority of head and neck lymphomas, with diffuse B-cell lymphoma as the most prevalent histologic subtype [8]. Extranodal involvement occurs in 25%-30% of head and neck NHL cases [7,8]. While Waldeyer's ring is the most frequent site of extranodal involvement in the head and neck, virtually any anatomical location can be affected [3,4]. Herein, we present a case of a premaxillary mass later identified as extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) with retrograde perineural spread along the infraorbital nerve.

Case report

A 40-year-old male with a history of testicular cancer status postorchidectomy presented to the emergency department with a 1-month history of enlarging right facial mass with associated pain and erythema. On physical examination, the patient had right facial numbness and erythema with a palpable right infraorbital mass. Initial computerized tomography (CT) maxillofacial with intravenous (IV) contrast demonstrated a 2.7 × 2.1 × 1.5 cm right infraorbital/premaxillary soft tissue density mass with asymmetric dilatation of the right infraorbital foramen (Figs. 1 and 2). There were no significant adjacent inflammatory changes or sinus disease. Despite a course of antibiotics, the patient returned to the emergency department 1 week later without improvement in symptoms. Repeat CT Maxillofacial with IV contrast demonstrated an interval increase in size (3.8 × 3.5 × 1.9 cm).

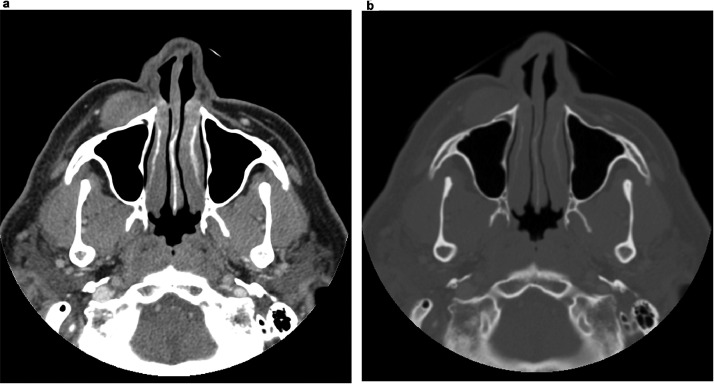

Fig. 1.

Axial CT maxillofacial with IV contrast in soft tissue window (A) and bone window (B) showing 2.7 × 2.1 × 1.5 cm right infraorbital/premaxillary soft tissue density mass without significant adjacent inflammatory changes or sinus disease.

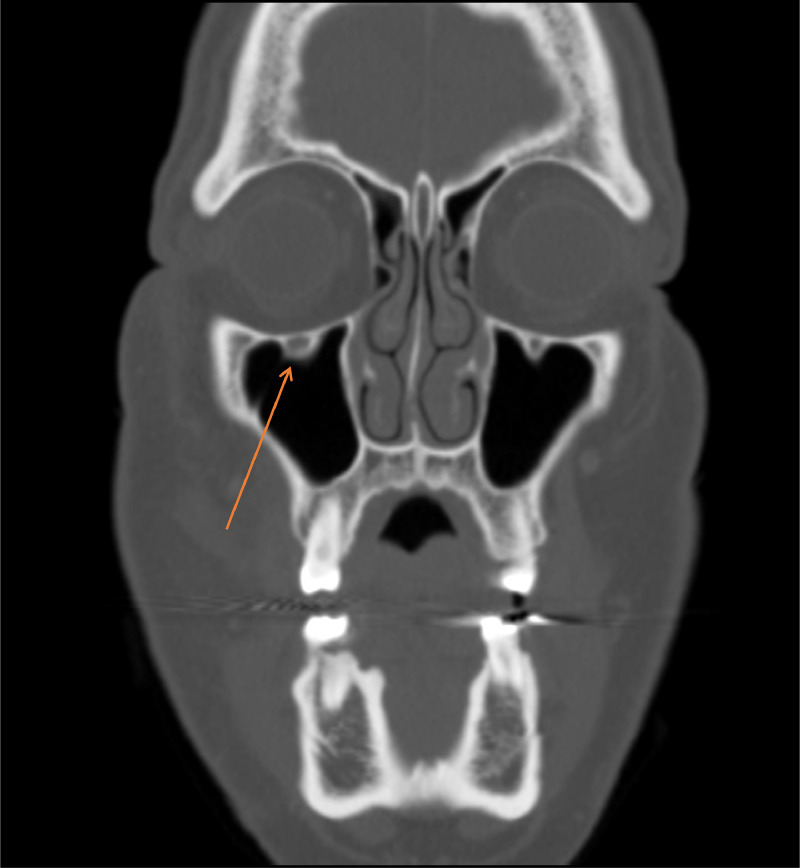

Fig. 2.

Coronal CT maxillofacial with IV contrast with asymmetric dilatation of the right infraorbital foramen.

The patient was subsequently admitted for further evaluation. Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy was performed and demonstrated atypical lymphoid cells with hyperchromatic nucleoli, scant cytoplasm, and immunohistochemical profile consistent with a nongerminal center b-cell-like subtype of DLBCL.

Post-FNA MRI brain with IV contrast (Fig. 3) demonstrated a predominantly T1/T2 isointense, enhancing premaxillary mass with diffusion restriction. Mild enhancement in the region of the infraorbital foramen/infraorbital nerve was also noted (Fig. 4).

Fig. 3.

MRI brain with DWI (left) and ADC (right) demonstrating diffusion restriction of a right premaxillary soft tissue mass.

Fig. 4.

Coronal T1 postcontrast MRI demonstrating asymmetric enhancement along the right infraorbital foramen.

CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis with IV contrast was obtained for staging purposes and demonstrated multiple enlarged right inguinal and left iliac lymph nodes. Our patient was subsequently referred to oncology and at the time of writing this report, had begun his first cycle of R-CHOP and was being evaluated for potential adjunctive radiotherapy.

Discussion

Lymphomas are the most common non-epithelial head and neck malignancy, accounting for 5-12% of all such malignancies. Extranodal involvement is seen in approximately one-fourth of cases of NHL. The most common extranodal sites of involvement include Waldeyer's ring, paranasal sinuses, salivary glands, mandible, and maxilla [1,3,4].

NHL classically presents clinically with lymphadenopathy and constitutional symptoms; however, the clinical presentation is nonspecific and varies based on molecular subtype, site of involvement, and individual patient [2,8]. The importance of imaging is underscored by the relatively high incidence of extranodal involvement, which may be occult on physical exam [7].

Magnetic resonance imaging plays a crucial role in evaluating and diagnosing NHL in the head and neck. Imaging features that help differentiate lymphomas from other head and neck malignancies have been described, although a definitive diagnosis is made by direct tissue sampling of the lesion. Higher signal on diffusion-weighted imaging is seen more frequently in lymphomas compared to other nonlymphoid malignancies, reflecting the high cellularity of the tumor. Lack of necrosis is an additional feature that can be helpful in differentiating NHL from other tumors [3,4].

Perineural spread, as seen in our case, is an important feature to establish as it has implications for prognosis and management. The presence of perineural spread confers a higher likelihood of tumor recurrence, regional lymph node involvement, and distant metastasis. MRI is particularly useful for evaluating perineural involvement and is typically characterized by asymmetric thickening or enhancement of the affected nerves. Fat-suppressed, postcontrast T1 sequences with thin slices (2 mm) are key in identifying and evaluating the extent of perineural spread [9]. Additional features that are useful in identifying perineural spread are the obliteration of fat pads and evidence of denervation atrophy [5,9].

The prognosis and management for patients with extranodal NHL in the head and neck vary depending on the patient's age, health status, and stage of the disease. Age greater than 60, elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), involved nodes both above and below the diaphragm, and higher stage are associated with a worse prognosis. The modified Ann Arbor staging system and Lugano classification system are commonly employed for staging and response to treatment, which rely on imaging as a key component. The mainstay of treatment is chemoimmunotherapy (R-CHOP [rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone]; however, concurrent radiation therapy may also be used depending on location [2,6,8].

Conclusion

NHL can be seen at nearly any site in the head and neck, including extranodal and extra-lymphoid locations. Increased signal on DWI and lack of necrosis can help differentiate lymphoma from other malignancies in the head and neck. Perineural spread is common in head and neck malignancies, including lymphoma. Our case highlights a unique premaxillary location of extranodal NHL with perineural spread along the infraorbital nerve.

Patient consent

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and all imaging studies. Consent form on record.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowlegments: This research was supported (in whole or in part) by HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare affiliated entity. The views expressed in this publication represent those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of HCA Healthcare or any of its affiliated entities.

References

- 1.Cooper JS, Porter K, Mallin K, Hoffman HT, Weber RS, Ang KK, et al. National Cancer Database report on cancer of the head and neck: 10-year update. Head Neck. 2009;31(6):748–758. doi: 10.1002/hed.21022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Storck K, Brandstetter M, Keller U, Knopf A. Clinical presentation and characteristics of lymphoma in the head and neck region. Head Face Med. 2019;15(1):1. doi: 10.1186/s13005-018-0186-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kato H, Kanematsu M, Kawaguchi S, Watanabe H, Mizuta K, Aoki M. Evaluation of imaging findings differentiating extranodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma from squamous cell carcinoma in naso- and oropharynx. Clin Imaging. 2013;37(4):657–663. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2012.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwok HM, Ng FH, Chau CM, Lam SY, Ma JKF. Multimodality imaging of extra-nodal lymphoma in the head and neck. Clin Radiol. 2022;77(8):e549–e559. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2022.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dankbaar JW, Pameijer FA, Hendrikse J, Schmalfuss I.M. Easily detected signs of perineural tumour spread in head and neck cancer. Insights Imaging. 2018;9(6):1089–1095. doi: 10.1007/s13244-018-0672-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, Cavalli F, Schwartz LH, Zucca E, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(27):3059–3068. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.54.8800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hanna E, Wanamaker J, Adelstein D, Tubbs R, Lavertu P. Extranodal lymphomas of the head and neck. A 20-year experience. Arch Otolaryngol–Head Neck Surg. 1997;123(12):1318–1323. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1997.01900120068011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Picard A, Cardinne C, Denoux Y, Wagner I, Chabolle F, Bach CA. Extranodal lymphoma of the head and neck: a 67-case series. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol, Head Neck Dis. 2015;132(2):71–75. doi: 10.1016/j.anorl.2014.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gandhi M., Sommerville J. The imaging of large nerve perineural spread. J Neurol Surg Part B, Skull Base. 2016;77(2):113–123. doi: 10.1055/s-0036-1571836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]