Abstract

As the sports medicine field has grown, the need for a more diverse workforce has become more evident. Given the growing athlete diversity that exists at all recreational and competitive levels of organized sports, it is important to better understand the current state of athletic health care diversity. This review assesses the current state of diversity in sports medicine from the perspective of the medical and athletic training professions. Men and women currently display nearly equivalent participation levels; however, the distribution of female team physicians and athletic trainers could better match the teams that they serve. Although progress has been made, much more needs to be done to bring more female athletic trainers and team physicians into athletic health care leadership roles. Early mentoring programs have shown efficacy for increasing the number of female candidates who might become the foundation of future athletic health care and academic program leaders.

Level of Evidence

V, expert opinion.

The passing of Title IX by U.S. Congress in 1972 fundamentally changed sports at the high school and college levels. In 1971, there were approximately 310,000 girls in high school and college sports; now, that number is greater than 3,373,000.1 Female athletes account for 42.8% of high school student-athletes, 44% of NCAA student-athletes, and 45% of the athletes who completed in the 2022 Beijing Olympics.2,3 As we begin to approach parity between male and female athletes competing in sports at all levels, the question arises whether team physicians and athletic trainers are representative of the diversity found in the populations that they serve. Diversity encompasses a wide range of characteristics, including race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, socioeconomic status, and physical ability. Increasing diversity can influence patient care in a variety of ways, from how patients perceive and interact with providers, to how providers understand and treat patients. Ultimately, this diversity can enhance patient care, improve clinical outcomes, and escalate innovations in the field. As the field of sports medicine continues to evolve, it is important to understand its current state of diversity and the impact it has on patient care, research, and education. Although this review aims to provide an overview of the current state of gender diversity in sports medicine, the focus lies specifically in a cohort that has thus far not been studied extensively: team physicians and athletic trainers.

Gender Diversity in Medicine

Overall, the field of medicine has become more gender diverse. Female medical students account for the majority at 51%, and fields such as pediatrics and obstetrics/gynecology have more female physicians than male physicians.4 Traditionally, female representation remains low in certain specialties, most consistently those of the surgical variety. In recent years there has been a noticeable increase of female representation in fields such as general surgery, otolaryngology, and plastic surgery.5 Although percentages of female inclusion have increased over time, they remain nominal. For example, from 2018 to 2023, the percentage of practicing female orthopaedic surgeons increased from 5.3% to 8%, whereas the percentage of those in various stages of training rose from 12.1% to 17%. A similar trend is seen in the sports medicine division of primary care, with 31% of family medicine, 30% of pediatrics, and 48.4% of physical medicine/rehabilitation fellowship spots now occupied by women.5 Again, despite this increase, the overall percentage remains small with the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine (AMSSM) reporting that only 29% of its members are women.6

Team Physicians

Team physicians serve a key role in sports team health at all levels. They work closely with other medical providers and athletic trainers to provide optimal medical care for the athletes under their purview and hold ultimate responsibility for any medical decision-making in the organization. When occupying such a key role, it is important for these positions to represent the populations that they serve.

Becoming a team physician generally requires graduation from medical school, completion of an orthopaedic surgery or primary care residency, and fellowship training in sports medicine. Most team physicians at all levels are men. At the collegiate level, 7.1% of the Southeastern Conference, 8.3% of the Atlantic Coast Conference, 30.8% of the Big Ten Conference, 0% of the Big 12 Conference, and 50% of Pacific-12 Conference teams had female team physician representation via the orthopaedic route.7 When primary care trained physicians are included in the analysis, these numbers increase to a total of 17.6% averaged across the Southeastern Conference, Atlantic Coast Conference, Big Ten Conference, Big 12 Conference, and Pacific-12 Conference.7 In the entirety of the NCAA, only 14.9.% of team physicians are women as of the 2022-2023 season, compared with 11.9% in the 2019-2020 season (Table 1).2,8 The greatest percentage of female team physicians in the NCAA are family medicine trained, at 63%.9

Table 1.

The Number and Percentage of Male and Female Assistant Athletic Trainers, Head Athletic Trainers, and Team Physicians at Each College Athletics Division

| Division I |

Division II |

Division III |

All |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Assistant athletic trainer | ||||||||

| Total | 2,820 | 885 | 1,020 | 4,725 | ||||

| Male | 1,325 | 47.0% | 343 | 38.8% | 406 | 39.8% | 2,074 | 43.9% |

| Female | 1,495 | 53.0% | 542 | 61.2% | 614 | 60.2% | 2,651 | 56.1% |

| Head athletic trainer | ||||||||

| Total | 382 | 310 | 442 | 1,134 | ||||

| Male | 294 | 77.0% | 197 | 63.5% | 246 | 55.7% | 737 | 65.0% |

| Female | 88 | 23.0% | 113 | 36.5% | 196 | 44.3% | 397 | 35.0% |

| Team physician | ||||||||

| Total | 356 | 273 | 377 | 1,006 | ||||

| Male | 296 | 83.1% | 245 | 89.7% | 315 | 83.6% | 856 | 85.1% |

| Female | 60 | 16.9% | 28 | 10.3% | 62 | 16.4% | 150 | 14.9% |

At the professional level, the number of female team physicians decreases even further. Combining orthopaedic and primary-trained physicians, there are only 3.3% women in the National Basketball Association, 10% in Major League Baseball, and 3.1% in the National Football League. The highest proportion of female team physicians was found in the Women’s National Basketball Association with 45.5% of teams having female representation.10,11

Perceptions of Orthopaedic Surgery

A review of the literature definitively shows that many female medical students still consider orthopaedic surgery to be a male-dominated field requiring physical strength, long hours, and a poor work–life balance.12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17 Studies have shown the importance of early exposure to orthopaedics in creating a positive association with increasing the number of women who apply.12,18, 19, 20 Bernstein at al.20 found that only 55% of medical schools included musculoskeletal instruction in their curriculum; changing this to a mandatory subject increased the number of female residents applying to orthopaedic surgery programs by 75%.21

One method for fostering interest in orthopaedics is developing pipeline programs to expose female medical students to the field before or during medical school. These programs promote early female mentorship and educate applicants about the realities of orthopedic surgery as a profession. One such program is The Perry Initiative, which focuses on female students studying Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (i.e., STEM) before medical school entry. This Perry Initiative program has been shown to double the match rate of female alumnae in current orthopaedic residency program classes. The program prioritizes hands-on experiences, mentorship opportunities and educational endeavors.22, 23, 24 Another program, Nth Dimensions, pairs first-year female medical students with orthopaedic surgeons in clinical settings. Those who participated in this program were also significantly more likely to apply to an orthopaedic surgery residency program.25

Leadership in Sports Medicine

Historically, men have dominated most (if not all) leadership positions in major sports organization organizations, including the American College of Sports Medicine, the AMSSM, the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, the American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Medicine, and the Arthroscopy Association of North America (AANA).6,26, 27, 28 Since their respective origins, the number of women who have served as president compared with the number of total presidents has been 5 of 28 for the AMSSM, 4 of 42 for the American Osteopathic Academy of Sports Medicine, 9 of 69 for the American College of Sports Medicine, 1 of 60 for the American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine, and 0 of 42 for AANA. With the organizational tagline of “Advancing the Scope,” it appears that AANA too could potentially do more to advance women into leadership roles. Much of the gender disparity in these leadership roles can be attributed to the lack of female representation in the field. Over the last decade, the number of female orthopaedic surgeons has increased from 4% to 5.9%.29 Similarly, the number of fellowship-trained sports physicians has also increased, representing an overall positive trend for gender diversity in sports medicine. Ideally, as these numbers continue to rise, the proportion of women who might ascend to leadership roles should likewise increase.

Mentorship

A key element for increasing interest for female students in orthopaedic surgery and sports medicine is same-gender mentorship. Mentorship has been found to be the single most significant influencer for a medical student’s decision to apply to an orthopaedic surgery residency program.30 However, surveys of medical students have shown that female students value same-gender mentorship more so than their male counterparts.17 In a similar vein, timing of mentorship plays an important role in the decision-making process. Male and female medical students display differences for when they choose to enter the orthopaedic surgery profession, with more female students deciding to pursue an orthopaedic surgery career after their orthopaedic surgery rotations and more male students making this decision based on experiences before medical school.18 This highlights the importance of having diverse faculty role models who can stimulate medical student interest in the field.

Currently, only 21% of faculty members in all orthopaedic surgery departments are women, some of the lowest ratios seen throughout all medical specialties.31 An even-smaller proportion of women are in orthopaedic surgery leadership positions, with only 1.7% serving as academic chairs and <10% as program directors.32 This further supports the importance of hiring and retaining female orthopaedic surgeons in academic leadership positions to provide sufficient mentorship to future generations of female orthopedic surgeons. Effective early mentoring experiences are directly related to the development of future female academic leaders and role models.

Fellowship Programs

Fellowship attendance rates have risen dramatically over the past decades for a variety of reasons, with more than 90% of orthopaedic surgery residents now choosing to pursue fellowship after residency program graduation.33 Overall, female applicants match at a greater rate (96%) compared with their male counterparts (81%).34 The top 3 fellowships that female orthopaedic surgery residency program graduates pursue are hand surgery, pediatric orthopaedic surgery, and sports medicine. In terms of absolute quantity, orthopaedic surgery sports fellowships had the greatest number of female applicants and graduates: and this number has remained relatively constant with approximately 11% to 12% of orthopaedic surgery sports fellowship spots going to female applicants. 5

Studies have shown that the 3 greatest influencers of subspecialty choice are enjoyment of procedures, proficiency in related surgical skills, and overall experiences with that field during residency program training.35, 36, 37 Comparatively, mentorship plays less of a role in specialty selection, with only 21% of respondents to a survey of female fellowship-trained orthopaedic surgeons citing this as a significant impactor. However, it is true that mentorship is the primary modifiable factor in the decision-making process.38 Kavolus et al.38 found that intellectual stimulation and a strong mentor were the most influential factors in a resident’s decision to pursue a certain fellowship, regardless of gender. The overall fellowship rate for primary care family practice residents is significantly lower than orthopaedic surgery residents (approximately 2%); however, female primary care residents who pursue fellowship training choose sports medicine at a greater rate than orthopaedic surgery residents (72%).5 Regardless, the overall number of women entering any Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education sports medicine fellowship is small compared with men, contributing to the small percentage who might be prepared to assume the team physician role at any given time.

Athletic Trainers

Athletic trainers serve an important and essential function in sports team health care management. They represent important front-line health care providers and are often with the team during both practices and games, developing and implementing treatment plans on a regular basis. In addition, they are usually the first responder to most athletic injuries. Female membership of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association is 54%.39 However, there is a notable decline in the number of female athletic trainers after 30 years of age at all levels of athletic training. This has become a highly researched topic in the athletic training literature with a notable focus on the collegiate setting. There are nearly twice as many female athletic trainers compared with male athletic trainers in the 22- to 27-year-old age range, but this number declines significantly between 28 and 35 years of age. Conversely, the population of male athletic trainers remains relatively stable between 27 and 42 years of age.40

The Distribution of Female Athletic Trainers in NCAA and Professional Sports

At the NCAA level, 56% of assistant athletic trainers are women with a breakdown of 53% in Division I, 61.2% in Division II, and 60.2% in Division III. Despite high gender diversity at the assistant athletic trainer level, there remains a large disparity at the highest NCAA levels, particularly in leadership positions, consistent with previously discussed fields. In 2023, only 35% of head athletic trainers are women across all NCAA divisions; and as the sports team level increases, the number of female head athletic trainers decreases, with 23.0% in Division I, 36.5% in Division II, and 44.3% in Division III (Table 1 and Fig 1).2,8

Fig 1.

Trends in male and female athletic trainer percentage changes over the last 11 years. Over time, the percentage of male athletic trainers and head athletic trainers has decreased as the number of women participating in those positions has increased. Currently, there are more female athletic trainers. However, there are significantly more male head athletic trainers than female head athletic trainers. (AAT, assistant athletic trainer; AT, athletic trainer; NCAA, National Collegiate Athletic Association.)

Analogous to the number of female team physicians, the number of female head athletic trainers is miniscule in professional sports. Among men’s professional sports, including the NBA, Major League Baseball, Major League Soccer, NFL, and the National Hockey League, only 1.3% of head athletic trainers are women.41 The drop-off of head athletic trainers who are women at increasing competition levels has received much attention and is the source of ongoing research.

Female Athletic Trainer Retention

Research has suggested that there are multiple reasons why many female athletic trainers choose to leave the profession before their male counterparts.40,42,43 Balancing family obligations with work responsibilities, irregular work hours, inflexible work schedules, motherhood, travel, and burnout have been cited as some primary reasons why women leave the field.43, 44, 45, 46, 47 The rigors of the job mean that athletic trainers face numerous stressors. Long road trips with lack of time at home, high pressure to win, limited days off, high athlete-to-athletic trainer ratios, treating athletes on scholarships, and long competitive seasons are stresses found at all levels of competition, but which tend to be higher with increasing levels of competition. Goodman et al.43 identified 4 main factors that influenced female athletic trainers to continue at work at the NCAA Division I level. These were increased autonomy, increased social support, enjoyment of job/fitting the NCAA Division I mold, and kinship responsibility. Conversely, they found that those who left NCAA Division I athletics did so for life balance issues, role conflict and role overload, and kinship responsibility. Kinship responsibility, or obligations toward the family, can be a highly motivating factor that influences a female athletic trainer to remain at her position or to leave the NCAA Division I level.43

Head Athletic Trainers

Despite the multifactorial reasons for the decline in female athletic trainers after 30 years of age, some continue their careers and go on to assume leadership roles within their organization. The head athletic trainer position comes with additional leadership responsibilities, often school administrator or athletic director. The added time requirements for administrative positions typically come in addition to clinical obligations. Traditionally, the head athletic trainer also assumes the position of the lead athletic trainer in charge of the football program at their institution.

One of the first researchers to investigate barriers that prevented female athletic trainers from seeking the role of the head athletic trainer was Gorant.48 She found that a combination of low aspirations, aversion to becoming the football team athletic trainer, additional administrative responsibilities, a reluctance to lead, a poorly proportioned work-life balance, and a need to overcome the “good old boys club” mentality were the primary barriers.48 Mazerolle and Eason49 continued the work of Gorant, refining these obstacles into 2 general barrier types that prevented women from either seeking or assuming the head athletic trainer role: organizational constraints and personal limitations. Broadly speaking, organizational constraints represent the limitations that are externally placed on female athletic trainers, including the subculture of a particular sport, gender discrimination, and gender role bias.48,50, 51, 52

Personal limitation factors were associated with individual values, characteristics, and internal limitations. These were found to originate from self-reflection and individual professional and personal goals. Examples of these include lack of desire to pursue leadership roles, prioritizing family relationships and motherhood, and lack of mentorship in the field.49 Both organizational constraints and personal factors can influence the number of female athletic trainers who choose to either remain in the field of athletic training and or choose to pursue roles with increasing responsibility and time requirements. In order to address the disparity between male and female athletic trainers at the highest levels of leadership, in addition to perceived personal limitations, potential organizational constraints should be addressed at the level of individual institutions.

Conclusions

Male and female participation in sports is nearly equal at all levels of play. It is well described that having medical team members that match the diversity of players in all aspects, including gender, would be beneficial to overall patient care and outcomes. However, the distribution of female team physicians and athletic trainers rarely matches that of the teams who they serve. Although there has been progress in bringing more women into leadership positions, particularly as team physicians and athletic trainers, more work needs to be done to balance the gender disparity found in these roles. The disparity is greatest with increasing levels of competition, particularly in leadership roles.

Several steps can be pursued to increase the gender diversity in sports medicine, for all members of the team. Allowing women to gain early exposure to sports medicine and facilitating opportunities for mentorship, whether same or mixed gender, is paramount. Promoting pipeline programs to students early in training is likely to aid in this endeavor. Increased opportunities for mentorship will continue to increase by placing women in positions of leadership and improving their visibility to potentially serve as role models (Fig 2). With these changes, we can increase the gender diversity in sports medicine and improve patient care and clinical outcomes.

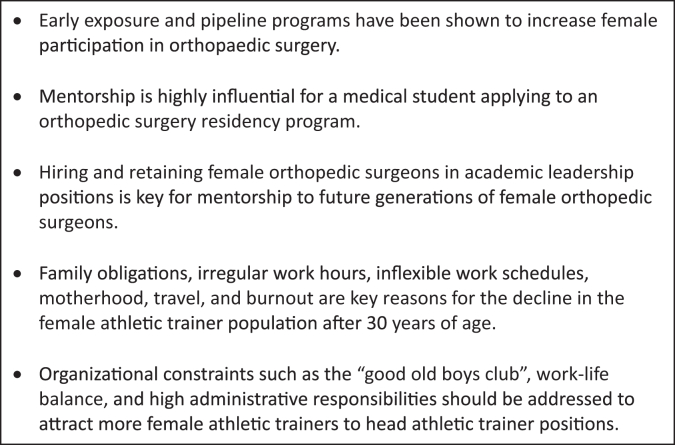

Fig 2.

Key factors that can increase gender diversity in sports medicine.

Footnotes

The authors report that they have no conflicts of interest in the authorship and publication of this article. Full ICMJE author disclosure forms are available for this article online, as supplementary material.

Supplementary Data

References

- 1.Barra A. Before and after Title IX: Women in sports. https://archive.nytimes.com/www.nytimes.com/interactive/2012/06/17/opinion/sunday/sundayreview-titleix-timeline.html

- 2.NCAA Demographics Database NCAA.org. https://www.ncaa.org/sports/2018/12/13/ncaa-demographics-database.aspx

- 3.Women at the Olympic Winter Games Beijing 2022 – All you need to know – Olympic News. https://olympics.com/ioc/news/women-at-the-olympic-winter-games-beijing-2022-all-you-need-to-know

- 4.Acuña A.J., Sato E.H., Jella T.K., et al. How long will it take to reach gender parity in orthopaedic surgery in the United States? An analysis of the National Provider Identifier Registry. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2021;479:1179–1189. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brotherton S.E., Etzel S.I. Graduate Medical Education, 2020-2021. JAMA. 2021;326:1088–1110. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.13501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. About AMSSM. https://www.amssm.org/about-amssm.php

- 7.O’Reilly O.C., Day M.A., Cates W.T., Baron J., Westermann R.W. The gender divide: Are female team physicians adequately represented in professional and collegiate athletics? Orthop J Sports Med. 2019;7 doi: 10.1177/0363546519897039. 2325967119S00402 (7_suppl 5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lewis C., Jin Y., Day C. Distribution of men and women among NCAA head team physicians, head athletic trainers, and assistant athletic trainers. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180:324–326. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Glover J., Walker M., Kaur J., Roche M., McIntyre A., Kraus E. Female representation in orthopaedic surgery and primary care sports medicine subspecialties: Where we were, where we are, and where we are going. J Womens Sports Med. 2022;2:127–135. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hinkle A.J., Brown S.M., Mulcahey M.K. Gender disparity among NBA and WNBA team physicians. Phys Sportsmed. 2021;49:219–222. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2020.1811065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baldwin K., Namdari S., Bowers A., Keenan M.A., Levin L.S., Ahn J. Factors affecting interest in orthopedics among female medical students: A prospective analysis. Orthopedics. 2011;34:e919–e932. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20111021-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huntington W.P., Haines N., Patt J.C. What factors influence applicants’ rankings of orthopaedic surgery residency programs in the National Resident Matching Program? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472:2859–2866. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-3692-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Neumayer L., Kaiser S., Anderson K., et al. Perceptions of women medical students and their influence on career choice. Am J Surg. 2002;183:146–150. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(01)00863-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohde R.S., Wolf J.M., Adams J.E. Where are the women in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1950–1956. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4827-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schroeder J.E., Zisk-Rony R.Y., Liebergall M., et al. Medical students’ and interns’ interest in orthopedic surgery: The gender factor. J Surg Educ. 2014;71:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.jsurg.2013.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Whitaker J., Hartley B., Zamora R., Duvall D., Wolf V. Residency selection preferences and orthopaedic career perceptions: A notable mismatch. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2020;478:1515–1525. doi: 10.1097/CORR.0000000000001161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hill J.F., Yule A., Zurakowski D., Day C.S. Residents’ perceptions of sex diversity in orthopaedic surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95:e1441–e1446. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Johnson A.L., Sharma J., Chinchilli V.M., et al. Why do medical students choose orthopaedics as a career? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2012;94:e78. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.00826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connor M.I. Medical school experiences shape women students’ interest in orthopaedic surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1967–1972. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4830-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bernstein J., Dicaprio M.R., Mehta S. The relationship between required medical school instruction in musculoskeletal medicine and application rates to orthopaedic surgery residency programs. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86:2335–2338. doi: 10.2106/00004623-200410000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.The Perry Initiative Inspiring women to be leaders in orthopaedic surgery and engineering. https://perryinitiative.org/

- 22.Day M.A., Owens J.M., Caldwell L.S. Breaking barriers: A brief overview of diversity in orthopedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 2019;39:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lattanza L.L., Meszaros-Dearolf L., O’Connor M.I., et al. The Perry Initiative’s medical student outreach program recruits women Into orthopaedic residency. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1962–1966. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4908-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mason B.S., Ross W., Ortega G., Chambers M.C., Parks M.L. Can a strategic pipeline initiative increase the number of women and underrepresented minorities in orthopaedic surgery? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1979–1985. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4846-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Sports Medicine Leadership. ACSM_CMS. https://www.acsm.org/about/leadership

- 26.American Orthopaedic Society for Sports Medicine Leadership. AOSSM. https://www.sportsmed.org/about-us/leadership

- 27.American Medical Society for Sports Medicine AMSSM Board of Directors. https://www.amssm.org/Board-of-Directors.php

- 28.Active Physicians by Sex and Specialty, 2021. AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/workforce/interactive-data/active-physicians-sex-specialty-2021

- 29.Sachdeva S., Hartley B., Roberts C. Ladies in the bone room? Addressing the gender gap in orthopaedics. Injury. 2022;53:3065–3066. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2022.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.2022 U.S. Medical School Faculty AAMC. https://www.aamc.org/data-reports/faculty-institutions/interactive-data/2022-us-medical-school-faculty

- 31.Odei B.C., Gawu P., Bae S., et al. Evaluation of progress toward gender equity among departmental chairs in academic medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181:548–550. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.6267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Horst P.K., Choo K., Bharucha N., Vail T.P. Graduates of orthopaedic residency training are increasingly subspecialized: A review of the American Board of Orthopaedic Surgery Part II Database. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97:869–875. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.N.00995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cannada L.K. Women in orthopaedic fellowships: What is their match rate, and what specialties do they choose? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:1957–1961. doi: 10.1007/s11999-016-4829-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alomar A.Z. Fellowship and future career plans for orthopedic trainees: Gender-based differences in influencing factors. Heliyon. 2022;8 doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e10597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bratescu R.A., Gardner S.S., Jones J.M., et al. Which subspecialties do female orthopaedic surgeons choose and why? Identifying the role of mentorship and additional factors in subspecialty choice. JAAOS Glob Res Rev. 2020;4 doi: 10.5435/JAAOSGlobal-D-19-00140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jurenovich K.M., Cannada L.K. Women in orthopedics and their fellowship choice: What influenced their specialty choice? Iowa Orthop J. 2020;40:13–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kocjan K., Safavi K.S., Flaherty B., et al. Current gender diversity and geographic trends among orthopaedic sports medicine surgeons in the United States. Orthop J Sports Med. 2022;10 doi: 10.1177/23259671221134091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kavolus J.J., Matson A.P., Byrd W.A., Brigman B.E. Factors influencing orthopedic surgery residents’ choice of subspecialty fellowship. Orthop. 2017;40:e820–e824. doi: 10.3928/01477447-20170619-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.National Athletic Trainers' Association NATA Quick Facts. https://www.nata.org/nata-quick-facts Published June 14, 2017.

- 40.Kahanov L., Eberman L.E. Age, sex, and setting factors and labor force in athletic training. J Athl Train. 2011;46:424–430. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-46.4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiggins A.J., Agha O., Diaz A., Jones K.J., Feeley B.T., Pandya N.K. Current perceptions of diversity among head team physicians and head athletic trainers: Results across US professional sports leagues. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9 doi: 10.1177/23259671211047271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kathanov L., Eberman L.E., Juzeszyn L. Factors that contribute to failed retention in former athletic trainers. Internet J Allied Health Sci Pract. 2013:111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Goodman A., Mensch J.M., Jay M., French K.E., Mitchell M.F., Fritz S.L. Retention and attrition factors for female certified athletic trainers in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I Football Bowl Subdivision setting. J Athl Train. 2010;45:287–298. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.3.287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eason C.M., Mazerolle S.M., Goodman A. Motherhood and work–life balance in the National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I setting: Mentors and the female athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2014;49:532–539. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.03. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mazerolle S.M., Bruening J.E. Sources of work–family conflict among certified athletic trainers, Part 1. Int J Athl Ther Train. 2006;11:33–35. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mazerolle S.M., Bruening J.E., Casa D.J., Burton L.J. Work-family conflict, Part II: Job and life satisfaction in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division I-A certified athletic trainers. J Athl Train. 2008;43:513–522. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43.5.513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Oglesby L.W., Gallucci A.R., Wynveen C.J. Athletic trainer burnout: A systematic review of the literature. J Athl Train. 2020;55:416–430. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-43-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gorant J. Female Head Athletic Trainers in NCAA Division I (IA Football) Athletics: How They Made It to the Top [dissertation]. Kalamazoo West Mich Univ. 2012. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/108

- 49.Mazerolle S.M., Eason C.M. Barriers to the role of the head athletic trainer for women in National Collegiate Athletic Association Division II and III settings. J Athl Train. 2016;51:557–565. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-51.9.08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burton L.J., Borland J., Mazerolle S.M. “They cannot seem to get past the gender issue”: Experiences of young female athletic trainers in NCAA Division I intercollegiate athletics. Sport Manag Rev. 2012;15:304–317. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazerolle S.M., Burton L., Cotrufo R.J. The experiences of female athletic trainers in the role of the head athletic trainer. J Athl Train. 2015;50:71–81. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-49.3.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohkubo M. Female intercollegiate athletic trainers' experiences with gender stereotypes. Master's Theses. 3551. DOI: 10.31979/etd.h287-ghrwhttps://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/etd_theses/355146, 2008. [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.