Abstract

Background

Intestinal stomas are surgical interventions that have an impact on both physical and psychological health, necessitating patient self-care. Insufficient knowledge regarding peristomal skin care, prevention, and treatment of potential problems can lead to an increase in stoma-related complications.

Objective

This study aimed to assess patients’ knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas and examine the relationship between background information and self-care knowledge.

Methods

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted from December 2021 to December 2022 at the Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hospital in Vietnam, involving 74 participants with intestinal stomas. A questionnaire consisting of 24 closed-ended questions was used to evaluate participants' knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas. Descriptive statistics, Chi-square, and Fisher’s exact tests were employed for data analysis.

Results

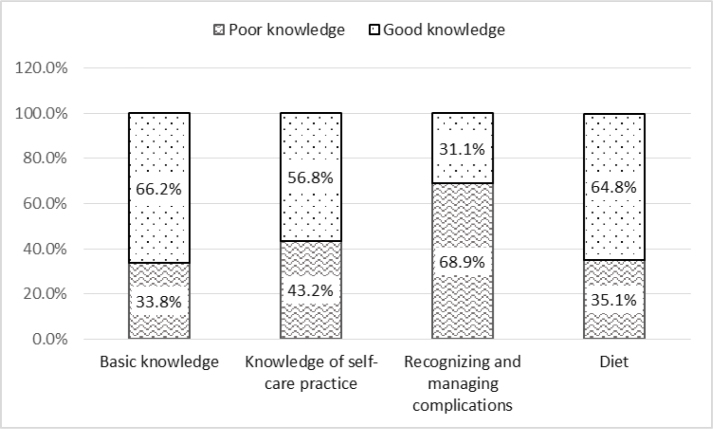

The findings revealed that 54.1% of participants had good knowledge of general self-care for intestinal stomas. The distribution of good knowledge among participants was as follows: basic knowledge (66.2%), self-care practice (56.8%), recognizing and managing complications (31.1%), and dietary knowledge (64.8%). Significant relationships were observed between participants’ self-care knowledge and their education level (p = 0.002), marital status (p = 0.017), nurses’ education (p = 0.021), and hospitalization (p = 0.001).

Conclusion

The proportion of participants with good knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas was relatively low, and it was associated with individuals' education level, marital status, nurses’ education, and hospitalization. This study highlights the need for ongoing development of educational programs on self-care for intestinal stomas. These programs should be tailored to address the specific needs of each patient and aim to improve their self-care knowledge in a meaningful and sustainable manner. By investing in patient education, healthcare professionals, particularly nurses, can assist individuals with intestinal stomas in achieving better outcomes and preventing potential complications.

Keywords: intestine, self-care, ostomy, knowledge, Viet Nam, nurses

Background

Intestinal stomas are medical procedures used to treat conditions of the gastrointestinal tract, including colorectal cancer and intestinal trauma. Seventy-five percent of intestinal stomas are conducted as part of the treatment for colorectal cancer (Ambe et al., 2018; Capilla-Díaz et al., 2019). Intestinal stomas can cause physical, psychological, and social functioning changes that impact the patient’s quality of life (Xu et al., 2018). An increase in new cases of colorectal cancer has resulted in an increase in people suffering from intestinal stomas (Capilla-Díaz et al., 2019). A study conducted in Vietnam indicated that the overall age-standardized incidence rate of colorectal cancer increased from 10.5 to 17.9 per 100,000 over 20 years (Pham et al., 2022). Primary physical problems caused by intestinal stomas include excrement leakage, peristomal skin lesions, and pain (Diniz et al., 2021). Intestinal stomas have been reported to cause negative emotions in patients (Silva et al., 2017). Quality of life scores for patients with intestinal stomas were slightly lower than the average scores of patients with chronic illnesses (Ran et al., 2016).

Lack of knowledge is one of the causes of complications related to stomas for patients after discharge (Kirkland-Kyhn et al., 2018). Research conducted in Egypt indicates that 43% of adult participants and 57% of adolescent participants with stomas had difficulty with self-care (Mohamed et al., 2017). Vo (2019) indicated that 26.3% of patients had good knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care. Forty percent of patients were evaluated as having good knowledge of stoma self-care after receiving a program focused on stoma self-care (Sabea & Shaqueer, 2021). Factors related to patients’ knowledge of intestinal self-care were reported in different studies. Collado-Boira et al. (2021) indicated that marital status and gender were factors related to patients’ knowledge of intestinal self-care. Education level was reported as a factor related to self-care knowledge of intestinal stomas (Collado-Boira et al., 2021; Elshatarat et al., 2020; Giordano et al., 2020; Mohamed et al., 2017; Shanmugam & Anandhi, 2016). Knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care was improved in patients who received adequate education for their self-care (Faury et al., 2017; Pandey et al., 2015; Ran et al., 2016).

Self-care is the practice of actions that people initiate and develop within certain time frames, with the goals of maintaining life and personal well-being (Queirós et al., 2014). Orem’s framework suggests that everyone has the ability to engage in self-care activities and become a self-care agent. Nurses are vital to assisting patients in achieving their self-care objectives (Martínez et al., 2021). In clinical settings, nurses play a crucial role in providing information and resources related to intestinal stoma self-care for patients and caregivers before discharge from the hospital. Educational programs for intestinal stoma self-care can enhance the self-care abilities of patients after discharge, improving their quality of life and stabilizing their disease in the future (Huang et al., 2018). Patients’ knowledge limitation about intestinal stoma care is associated with deficits in knowledge about stoma irrigation, measurement, and stoma-related complications (e.g., identifying problems, caring for peristomal skin, and preventing and treating potential complications) (Cheng et al., 2013). Kirkland-Kyhn et al. (2018) revealed that patients should be trained about products used for caring for stomas at home (e.g., spout clamp), stoma management, and signs indicating when support from a healthcare worker is necessary.

Assessing the patient’s competence level for intestinal stoma self-care is crucial to identify patient needs and direct nursing interventions to improve self-care (Silva et al., 2018). Due to a lack of studies discussing this phenomenon in Viet Nam; thus, this study aimed to assess patients’ knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care and examine its relationships with their background information.

Methods

Study Design

A descriptive cross-sectional study was conducted at the Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hospital, a unit of the Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam. The study was conducted from December 2021 to December 2022 on patients who underwent intestinal stomas as part of the treatment for gastrointestinal conditions.

Samples/Participants

The study included patients with intestinal stomas as part of their treatment for gastrointestinal conditions, with their stomas intact during the survey administration. The sample size was calculated using a 95% confidence interval, 5% margin error, and 5% of the population proportion. The sample size was 74 based on the formula calculating the adequate sample size in a prevalence study, with prevalence obtained from the study of Vo (2019) (p = 0.263 derived from the rate of participants with poor knowledge). The inclusion criteria for this study were patients who had intestinal stomas as part of their treatment for gastrointestinal conditions and were also responsible for the post-discharge care of their stomas at the time of survey administration. Participants with limitations in listening, speaking, reading, and writing Vietnamese were excluded from this study. Convenient sampling was used to collect data, and all patients who met the inclusion criteria were invited to join the study. Data were collected until the sample size was obtained. Eighty participants were invited to join the study, and the response rate was 92.5%, resulting in 74 participants who met the inclusion criteria.

Instruments

The questionnaire for this study consisted of two sections: background information and knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas. The section on background information included six questions to identify participant demographic characteristics and four questions to identify healthcare information. Demographic characteristics included age, gender, residential location, education level, marital status, and occupation. Healthcare information included diagnosis, hospitalization, healthcare information resources, and whether the participant received nurse education at discharge from the hospital.

The second section of the questionnaire was designed to measure participants’ knowledge about intestinal stoma self-care. It included 24 questions related to basic knowledge of intestinal stomas, self-care for intestinal stomas, recognizing and managing complications, and nutrition for intestinal stomas. The questionnaire used in this study was adapted from a validated questionnaire created by Le et al. (2013), which exhibited a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.8. To assess the reliability of the questionnaire, a pilot test was conducted with 30 participants that yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.84.

To evaluate the participant’s basic knowledge, the questionnaire used five questions to examine the definition, types, formation, and normal status of the mucosa and skin around the intestinal stoma. Nine questions were used to examine the participant’s knowledge of self-care practices related to intestinal stomas. Five questions examined the participant’s knowledge of recognizing and managing complications associated with intestinal stoma care.

Finally, five questions were used to assess knowledge of nutrition related to intestinal stomas, including diet, eating habits, and dietary recommendations. All questions were closed-ended and included multiple-choice or true or false questions. Participants’ responses were scored as (1) for correct answers and (0) for incorrect answers across all 24 questions. According to Le et al. (2013), the total score was classified as either good knowledge (70% or more) or poor knowledge (less than 70%). Since 70% of the correct answers were scored at 16.8, the total score was rounded to 17 since it is an integral number. Participants were assessed as having poor knowledge if they obtained a score less than 17 and good knowledge if they obtained a score greater than or equal to 17.

Data Collection

Data collection for this study began once ethical approval was granted. The study included 74 participants who were diagnosed with intestinal stomas and admitted or readmitted to the Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hospital. Participants who agreed to participate in the study and signed the informed consent form were given the questionnaire. The questionnaire was administered to participants one day before discharge when their health status had stabilized from their initial admission to the hospital. Participants were invited to a separate room where the researcher explained the purpose of the study and the voluntary nature of participation. A clear explanation about the security of participants’ information and the use of a separate room was used to reduce the bias of the answers caused by the support from others (family and/or other patients in the same room).

The survey took an average of ten minutes for participants to complete, and they were allowed to complete it in a private space. Nine participants who had difficulty reading or writing were assisted by the investigator in answering the questions. Sixty-five participants completed the questionnaire independently. The survey was administered at the end of the morning or afternoon after medication administration and nursing care had concluded. Prior to administering the survey, participants were asked if they were comfortable and ready to participate in the study.

Data Analysis

IBM® SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 was utilized for data input and encoding. Descriptive statistics, including frequency, percent, mean, standard deviation, and range, were used to analyze the demographic characteristics and participants’ knowledge of intestinal stomas. The relationship between categorical variables was examined using Chi-square (χ2) tests. Fisher’s exact test was used instead of the Chi-square test when more than 20% of cells had expected frequencies less than 5. The statistical significance of the differences between categorical variables was considered significant if the p-value was less than 0.05.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Ethical Approval No. 2510/DHYDCT on December 22, 2021). The identity of the participant was protected at every moment of the research to guarantee the maintenance of anonymity. A complete instruction sheet was supplied to the participants, including an explanation of the goals of the research. Voluntary participation and a statement of anonymity were declared in the informed consent. The participants were administered the questionnaire after they agreed and signed the informed consent form. The questionnaire was given one day before discharge to avoid uncomfortable effects on the participants because they were planned to be discharged when their health status had stabilized from their initial admission to the hospital.

Results

Characteristics of the Participants

The mean age of the participants in this study was 57.9 ± 12.4 years, with 77% of the participants being over the age of 50. Nearly half (47.3%) of the participants identified as female. The percentage of the participants living in rural areas was 71.6%, while the remaining 28.4% included the participants living in neighboring towns (e.g., Thanh An towns belonging to Vinh Thanh district) and cities (e.g., Long Xuyen city belonging to An Giang province). Approximately 8% of participants in this study reported not being able to read, while 4% had a college or university degree. Most participants (93.2%) were married, while the remainder were single or widowed (2.7% and 4.1%).

Approximately one-third (31.1%) of the participants were retired; the remaining included housework (6.8%), manual labor (31.1%), mental labor (29.7%), and joblessness (1.4%). Nearly all participants (97.3%) had an intestinal stoma as part of the treatment for colorectal cancer, and the vast majority (89.2%) received nurses’ education about caring for intestinal stomas. The internet was the primary source of information for self-care for 81.1% of participants. Of the 74 participants, 49 (66.2%) were readmitted with an intestinal stoma, and 21.5% experienced multiple hospital readmissions. Additionally, approximately 82.4% of participants in the study had a temporary stoma.

Knowledge of Self-Care for Intestinal Stomas

The results of participants’ knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas are presented in Table 1, with 54.1% of the participants demonstrating good knowledge.

Table 1.

General knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas among participants

| Range | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Poor Knowledge |

Good Knowledge |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| General knowledge of self-care for intestinal stoma | 18 | 6 | 24 | 16.58 | 4.57 | 34 (45.9%) | 40 (54.1%) |

Figure 1 illustrates the distribution of participants’ knowledge levels across different domains of intestinal stoma care. The highest percentage of good knowledge was demonstrated for basic knowledge (66.2%), and the lowest percentage was shown in recognizing and managing complications (31.1%).

Figure 1.

Specific knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas among participants

Relationship Between Self-Care Knowledge for Intestinal Stomas and Participant Background Information

Table 2 presents the relationships between participants’ knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas and demographic characteristics. Education level (p = 0.002) and marital status (p = 0.017) were found to have a statistically significant relationship with self-care knowledge. However, there was no statistically significant relationship between self-care knowledge and gender, area of residence, age, and occupation.

Table 2.

Relationship between self-care knowledge and demographic characteristics

| Characteristics | Knowledge |

χ2/F | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor n (%) | Good n (%) | ||||

| Gender | Female | 15 (20.3%) | 20 (27.0%) | 0.225† | 0.613 |

| Male | 19 (25.7%) | 20 (27.0%) | |||

| Resident area | Rural | 22 (29.7%) | 31 (41.9%) | 1.480† | 0.224 |

| Urban | 12 (16.2%) | 9 (12.2%) | |||

| Age | <30 years old | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | 3.104‡ | 0.355 |

| 30 – <50 years old | 7 (9.5%) | 9 (12.2%) | |||

| 50 – <70 years old | 19 (25.7%) | 26 (35.1%) | |||

| >70 years old | 8 (10.8%) | 4 (5.4%) | |||

| Education level | Illiterate | 4 (5.4%) | 2 (2.7%) | 14.559‡ | 0.002(*) |

| Primary school | 17 (23.0%) | 7 (9.4%) | |||

| Secondary school | 13 (17.6%) | 23 (31.0%) | |||

| Highschool | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (6.8%) | |||

| College/university education | 0 (0.0%) | 3 (4.1%) | |||

| Occupation | Housework | 3 (4.1%) | 2 (2.7%) | 2.471‡ | 0.707 |

| Manual labor | 12 (16.2%) | 11 (14.9%) | |||

| Mental labor | 8 (10.8%) | 14 (18.9%) | |||

| Retired | 11 (14.9%) | 12 (16.2%) | |||

| Jobless | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Marital status | Single | 2 (2.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5.505‡ | 0.017(*) |

| Engage or married | 29 (39.2%) | 40 (54.1%) | |||

| Divorced/separated/widow | 3 (4.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

: Chi-square;

: Fisher’s exact test;

: Significant at p < 0.05

Table 3 presents that there were statistically significant correlations between knowledge of self-care for intestinal stomas and nurses’ education (p = 0.021) as well as hospitalization (p = 0.001). However, there was no statistically significant relationship between self-care knowledge and sources of information or diagnoses.

Table 3.

Relationship between self-care knowledge and healthcare information

| Healthcare information | Knowledge |

χ2/F | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Poor n (%) | Good n (%) | ||||

| Diagnosis | Colorectal cancer | 33 (44.6%) | 39 (52.7%) | 0.000‡ | 1.000 |

| Others | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Nurses’ education received | Yes | 27 (36.5%) | 39 (52.7%) | 0.000‡ | 0.021(*) |

| No | 7 (9.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Source of information referenced | Televisions | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (1.4%) | 5.316‡ | 0.077 |

| Journals, magazines, posters | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.4%) | |||

| Internet | 23 (31.1%) | 34 (45.9%) | |||

| Never access | 10 (13.5%) | 4 (5.4%) | |||

| Hospitalization | First time | 18 (24.3%) | 7 (9.5%) | 10.319† | 0.001(*) |

| Second or more | 16 (21.6%) | 33 (44.6%) | |||

: Chi-square;

: Fisher’s exact test;

: Significant at p < 0.05

Discussion

Characteristics of the Participants

The mean age of the participants included in this study (57.9±12.4) was similar to a study conducted in southern Vietnam in 2019, which included participants with intestinal stomas with a mean age of 55.6 years (Vo, 2019). Colorectal cancer is becoming more common in people over the age of 50, with 90% of all CRCs diagnosed after 50 years of age (Wong et al., 2019). Seventy-seven percent of participants in our study were over 50 years old when their intestinal stomas were surgically placed as part of the treatment for colorectal cancer. The high proportion of participants aged 50 and above reflects the common age of people diagnosed with colorectal cancer. Mai et al. (2019) found that the majority (81.6%) of colorectal cancer participants were over 50 during an eight-year research study at Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hospital.

Gender distribution was slightly disproportionate in studies about the incidence and prevalence of intestinal stomas and colorectal cancer conducted in South Vietnam. Le et al. (2013) indicated that the percentages of male and female participants with intestinal stomas and colorectal cancer were 60.4% and 39.6%, respectively. Mai et al. (2019) indicated that the percentages of male and female participants with intestinal stomas and colorectal cancer were 56.8% and 43.1%, respectively. Vo (2019) reported that the percentages of male and female participants with intestinal stomas and colorectal cancer were 52.8% and 47.2%, respectively. Similarly, our study found a higher percentage of males with intestinal stomas than females (52.7% and 47.3%, respectively). According to research by Wong et al. (2019) about the prevalence of and risk factors for colorectal cancer in Asia, men have a higher prevalence of colorectal cancer than women.

Our study recorded a significant proportion (8.1%) of participants who could not read Vietnamese or any other language. The reading literacy rate in our study was lower than that in Vo (2019), which surveyed more developed areas in southern Vietnam (i.e., Ho Chi Minh City), with an illiteracy rate of 0%. The proportion of people who could not read any language reflected a significant illiteracy rate in the Mekong Delta, where this study was conducted. According to the Viet Nam General Statistics Office (2020), approximately 18.4% of the population in the Mekong Delta is illiterate. Illiteracy should be considered when examining factors that affect the effectiveness of health education for participants.

Knowledge of Self-Care for Intestinal Stomas

In our study, a significant proportion of participants (45.9%) had poor knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care. This finding is consistent with the studies conducted by Le et al. (2013) and Pham (2020), which reported similar rates of poor knowledge (48.1% and 39.8%, respectively). However, Vo (2019) reported a higher percentage of poor knowledge (73.7%). In Nepal, Pandey et al. (2015) found that 38.3% of participants had inadequate knowledge, while a study conducted in India by Shanmugam and Anandhi (2016) reported that 76.7% of participants had inadequate knowledge about intestinal stoma self-care. Another study by Ran et al. (2016) found that 70.4% of participants lacked knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care in the hospital setting.

Similar to Le et al. (2013), our study found that the highest percentage of good knowledge belonged to basic knowledge regarding intestinal stomas, while the lowest percentage of good knowledge was related to recognizing and managing complications (66.2% and 31.1%, respectively). Cheng et al. (2013) and Mohamed et al. (2019) also reported limitations in participants’ knowledge regarding complications and risks of intestinal stomas. Mohamed et al. (2019) found that 41.4% of participants had poor knowledge of the definition, causes, types, complications, and risks of stomas.

Despite the critical importance of self-care knowledge in maintaining stoma health and preventing complications, our study found that 43.2% of participants had poor knowledge of self-care practices for intestinal stomas. This highlights the need for an improved education program for individuals with intestinal stomas. Mohamed et al. (2019) also reported a limited rate (52.9%) of adult participants with good knowledge of self-care practices. Providing knowledge and teaching self-care to participants with intestinal stomas before hospital discharge can help optimize their quality of life (Cheng et al., 2013). Nurses’ instructions on stoma self-care had a significant positive effect on participants’ knowledge and self-care practices (El-Rahman et al., 2020).

Relationship Between Self-care Knowledge for Intestinal Stomas and Participant Background Information

Statistically significant relationships were found between self-care knowledge, education level, and marital status (p = 0.002 and p = 0.017, respectively). Collado-Boira et al. (2021) found that participants who lived with a partner had significantly higher self-care scores than other participants in the study. While some studies have found a link between gender and knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care, others have found no relationship between gender and knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care. Elshatarat et al. (2020) indicated no relationship between gender and knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care. However, Collado-Boira et al. (2021) recorded gender as one of the associations with participants’ knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care.

Studies have produced different conclusions regarding the relationship between education level and self-care knowledge of intestinal stomas. Pandey et al. (2015) indicated no association between education level and knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care. However, Shanmugam and Anandhi (2016), Mohamed et al. (2019), Elshatarat et al. (2020), Giordano et al. (2020), and Collado-Boira et al. (2021) reported education level as being connected to self-care knowledge of intestinal stomas.

It is crucial to educate and encourage patients with intestinal stomas about stoma self-care in practice. Educating patients with intestinal stomas includes providing knowledge to assist patients in taking care of themselves on a daily basis, as well as health promotion and psychological adjustment. Effective communication, teamwork, and practical teaching are essential to enable participants to self-care (Di Gesaro, 2012). Our study indicated a high rate of participants having poor knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care, despite 89.2% of the participants indicating that they had been educated by nurses about intestinal stoma self-care. Our study also noted a significant difference in knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care between participants who received nurses’ education and those who did not (p = 0.021). The high rate of poor knowledge and the difference in knowledge of intestinal stoma care among participants with and without nurses’ instruction indicated a need for improving nurses’ education about intestinal stoma self-care. A high level of knowledge contributes to increasing attitude and practice, as there is a correlation between the level of knowledge and attitude and practice (Shanmugam & Anandhi, 2016). Ostomates who receive training have been found to have significantly higher mean knowledge scores than those who do not (Pandey et al., 2015). Faury et al. (2017) found that health education improved psychosocial and self-management skills.

Patients can experience successful adjustment to permanent intestinal stomas if they receive adequate instruction in self-care (Collado-Boira et al., 2021). Ran et al. (2016) indicated that education about intestinal stoma self-care should be implemented preoperatively and postoperatively on a periodic basis in the hospital setting. Patients need feedback and retraining to extend their knowledge and self-care skills regarding their intestinal stomas (Ran et al., 2016). Nurses should be attentive to patients’ knowledge, concerns, and responses and ensure personalization during the education process (Kirkland-Kyhn et al., 2018). Healthcare professionals need to develop an appropriate self-care program to provide general knowledge, life adaptation, and psychological adaptation (Ran et al., 2016).

This study and relevant literature emphasize the significant role nurses play in improving patients’ understanding of intestinal stoma self-care. As a result, there is a clear need to establish an education program with the objective of enhancing patients’ knowledge in this area. To develop an effective program, it is essential to conduct an analysis of the specific requirements of actual patients (Sabea & Shaqueer, 2021).

Consideration of participants’ background characteristics, such as education level and marital status, is crucial during the implementation of the education program to improve self-care abilities for patients with intestinal stomas. This importance arises from the association of educational level and marital status with self-care knowledge, which has been supported by studies conducted by Ran et al. (2016) and Sabea and Shaqueer (2021). To maximize the effectiveness of the education program to improve self-care abilities for patients with intestinal stomas, it is recommended to include periodic repetitions of the education sessions as suggested by Ran et al. (2016) and supported by the research conducted by Sabea and Shaqueer (2021).

Our study revealed a significant difference in self-care knowledge between participants during their first hospitalization and those who were readmitted (p = 0.001). Readmitted participants had more opportunities to receive instructions from nurses and more time to learn from other sources of information, such as fellow patients. Giordano et al. (2020) reported a 25% increase in self-care monitoring among patients with intestinal stomas for six months. Elshatarat et al. (2020) found that a majority of participants expressed a desire to participate in continuous health education and receive more than one teaching strategy for intestinal stoma care training. Additionally, Mohamed et al. (2017) found that an educational program improved participants’ knowledge of intestinal self-care management both before and after the program, as well as during follow-up. Almanzalawy (2020) suggests continuous education regarding intestinal stoma self-care, lifestyle changes, and self-efficacy to enhance knowledge and practice of stoma care. In general, a continuous education program tailored to the needs of patients is crucial for improving their self-care ability and preventing stoma-related complications.

Limitations

The significant difference in knowledge of intestinal stoma self-care was demonstrated between participants who received nurses’ education and those who did not, and between participants during their first hospitalization and those who were readmitted. However, evaluating how and what patients are educated about self-care is necessary. This study limitation should be considered in future studies about patients’ self-care for intestinal stomas.

Implications for Nursing Practice

Several implications of this study for nursing practice: 1) The study highlights the importance of education and training for nurses regarding self-care for intestinal stomas. Since participants’ education level was found to be significantly related to self-care knowledge, the nursing practice should prioritize providing comprehensive education programs and training sessions to improve nurses' understanding of stoma care; 2) The findings indicate that nurses should pay special attention to specific demographic characteristics when delivering self-care instructions. For example, participants’ marital status was found to be significantly related to self-care knowledge. Nurses should consider tailoring their teaching methods and strategies based on individual patients’ demographic characteristics to ensure effective communication and understanding of self-care instructions; 3) The results emphasize the importance of ongoing professional development for nurses in the field of stoma care. Continuing education programs, workshops, and conferences can help nurses stay updated with the latest advancements in stoma care; 4) The study highlights the need for collaboration between nurses and other healthcare professionals involved in the care of patients with intestinal stomas. Since knowledge of self-care was found to be significantly correlated with the education of nurses and hospitalization, interdisciplinary collaboration can be beneficial in enhancing nurses' knowledge through sharing expertise and experiences.

Conclusion

This study has revealed a deficiency in participant knowledge about intestinal stoma self-care. Specifically, the lowest percentage of good knowledge was observed in recognizing and managing complications, which highlights the need for targeted improvements in self-care education. The study also found significant correlations between knowledge of intestinal stoma care among participants and their education level, marital status, self-care education of nurses, and hospitalization status. To address these knowledge gaps effectively, it is crucial to establish and sustain educational programs focused on intestinal stoma self-care. These programs should be individualized to meet each patient's specific needs and promote meaningful and lasting improvements in their self-care knowledge. By investing in patient education, individuals with intestinal stomas can experience improved patient and nursing outcomes while reducing the risk of potential complications.

Acknowledgment

The authors are sincerely grateful to all participants for volunteering in this study as well as to Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam, for their support.

Declaration of Conflicting Interest

The authors declared no conflict of interest in this study.

Funding

The research received no external funding.

Authors’ Contributions

The authors participated in all aspects of the research, with the main contribution assigned as follows: DTN was responsible for the design, manuscript preparation, and final approval of the version to be published. MH specifically contributed to revising important intellectual content. TTTN specifically contributed to data collection. HTNN was responsible for the concept. THN contributed to the data analysis. TNTM contributed to the interpretation of the results and the draft. All authors approved the final version of the article to be published.

Authors’ Biographies

Thi Dung Ngo, MSN, BSN, RN is a Surgical Nursing Lecturer at the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Technology, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam. She has a master’s degree from the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. She is currently studying the Doctor in Nursing Management program at Trinity University of Asia, Philippines. Her research interests include surgical nursing, nursing research, and evidence-based practice in nursing.

Asst. Prof. Miranda Hawks, PhD, RN, CNL is an Assistant Professor at WellStar College of Health and Human Services, Kennesaw State University, USA. She has a PhD in nursing and a Masters in nursing from the Medical College of Georgia. Her research interests include the intersection of global population health, anthropology, and cultural humility.

Thi Thanh Truc Nguyen, MSN, BSN, RN is a Basic Nursing Lecturer at the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Technology, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam. She has a master’s degree from the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. She is currently studying the Doctor in Nursing Management program at Trinity University of Asia, Philippines. Her research interests include basic nursing, internal medical nursing, surgical nursing, and nursing management.

Thi Ngoc Han Nguyen, MSN, BSN, RN is a Pediatric Nursing Lecturer at the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Technology, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam. She has a master’s degree from Burapha University, Viet Nam. She is currently studying the Doctor in Nursing Management program at Trinity University of Asia, Philippines. Her research interests include pediatric nursing, nursing education, and nursing management.

Hong Thiep Nguyen, MSN, BSN, RN is a Surgical Nursing Lecturer at the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Technology, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam. She has a master’s degree from the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. She is currently studying the Doctor in Nursing Management program at Trinity University of Asia, Philippines. Her research interests include surgical nursing, nursing education, and nursing management.

Nguyen Thanh Truc Mai, MSN, BSN, RN is a Maternal Nursing Lecturer at the Faculty of Nursing and Medical Technology, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, Viet Nam. She has a master’s degree from the University of Medicine and Pharmacy in Ho Chi Minh City, Viet Nam. Her research interests include maternal nursing, nursing education, and evidence-based practice in nursing.

Data Availability

Datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declaration of Use of AI in Scientific Writing

Generative AI and AI-assisted technologies were not used in the writing process.

References

- Almanzalawy, H. (2020). Effect of self-management program on the patient’ knowledge and practice regarding stoma care. Assiut Scientific Nursing Journal, 8(23), 55-66. 10.21608/asnj.2021.51543.1082 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ambe, P. C., Kurz, N. R., Nitschke, C., Odeh, S. F., Möslein, G., & Zirngibl, H. (2018). Intestinal ostomy: Classification, indications, ostomy care and complication management. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International, 115(11), 182-187. https://doi.org/10.3238%2Farztebl.2018.0182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capilla-Díaz, C., Bonill-de Las Nieves, C., Hernández-Zambrano, S. M., Montoya-Juárez, R., Morales-Asencio, J. M., Pérez-Marfil, M. N., & Hueso-Montoro, C. (2019). Living with an intestinal stoma: A qualitative systematic review. Qualitative Health Research, 29(9), 1255-1265. 10.1177/1049732318820933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, F., Meng, A. F., Yang, L.-F., & Zhang, Y. N. (2013). The correlation between ostomy knowledge and self-care ability with psychosocial adjustment in Chinese patients with a permanent colostomy: A descriptive study. Ostomy Wound Management, 59(7), 35-38. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado-Boira, E. J., Machancoses, F. H., Folch-Ayora, A., Salas-Medina, P., Bernat-Adell, M. D., Bernalte-Martí, V., & Temprado-Albalat, M. D. (2021). Self-care and health-related quality of life in patients with drainage enterostomy: A multicenter, cross sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(5), 2443. 10.3390/ijerph18052443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Gesaro, A. (2012). Self-care and patient empowerment in stoma management. Gastrointestinal Nursing, 10(2), 19-23. 10.12968/gasn.2012.10.2.19 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diniz, I. V., Costa, I. K. F., Nascimento, J. A., Silva, I. P. d., Mendonça, A. E. O. d., & Soares, M. J. G. O. (2021). Factors associated to quality of life in people with intestinal stomas. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP, 55. 10.1590/1980-220X-REEUSP-2020-0377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Rahman, A., Ali, W., Mekkawy, M. M., & Ayoub, M. T. (2020). Effect of nursing instructions on self care for colostomy patients. Assiut Scientific Nursing Journal, 8(23), 96-105. 10.21608/asnj.2020.48530.1066 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elshatarat, R. A., Ebeid, I. A., Elhenawy, K. A., Saleh, Z. T., Raddaha, A. H. A., & Aljohani, M. S. (2020). Jordanian ostomates' health problems and self-care ability to manage their intestinal ostomy: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Research in Nursing, 25(8), 679-696. 10.1177/1744987120941568 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faury, S., Koleck, M., Foucaud, J., M’Bailara, K., & Quintard, B. (2017). Patient education interventions for colorectal cancer patients with stoma: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(10), 1807-1819. 10.1016/j.pec.2017.05.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, V., Nicolotti, M., Corvese, F., Vellone, E., Alvaro, R., & Villa, G. (2020). Describing self‐care and its associated variables in ostomy patients. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(11), 2982-2992. 10.1111/jan.14499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang, L., Yu, H., Sun, A., Xu, F., Xia, C., Gao, D., & Wang, D. (2018). Effects of continuing nursing on stomal complications, self-care ability and life quality after Miles’ operation for colorectal carcinoma. International Journal of Clinical and Experimental Medicine, 11(2), 1021-1026. [Google Scholar]

- Kirkland-Kyhn, H., Martin, S., Zaratkiewicz, S., Whitmore, M., & Young, H. M. (2018). Ostomy care at home. AJN The American Journal of Nursing, 118(4), 63-68. 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000532079.49501.ce [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le, T. H., Messmer, P., & Tran T. T. (2013). Knowledge, attitude and practice of patients' self care colostomy [in Vietnamese]. Y Hoc TP. Ho Chi Minh, 17, 209 – 216. [Google Scholar]

- Mai, V. D., Vo, T. H., Nguyen V. H., Nguyen V. T., & Pham, V. N. (2019). Laparoscopic surgery for colorectal cancer: 8 years results [in Vietnamese]. Tap chi Y Duoc hoc Can Tho, 22, 1-8. [Google Scholar]

- Martínez, N., Connelly, C. D., Pérez, A., & Calero, P. (2021). Self-care: A concept analysis. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 8(4), 418-425. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2021.08.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, H., Abd El-Hay, S., & Sharshor, S. (2019). Self-care knowledge and practice for patients with permanent stoma and their effect on their quality of life and self care efficacy. Journal of Health, Medicine and Nursing, 60, 131-138. 10.7176/JHMN/60-13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed, S. S., Salem, G. M., & Mohamed, H. A. (2017). Effect of self-care management program on self-efficacy among patients with colostomy. American Journal of Nursing Research, 5(5), 191-199. 10.12691/ajnr-5-5-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pandey, R. A., Baral, S., & Dhungana, G. (2015). Knowledge and practice of stoma care among ostomates at bp koirala memorial cancer hospital. Journal of Nobel Medical College, 4(1), 36-45. [Google Scholar]

- Pham, D. X., Phung, A. H. T., Nguyen, H. D., Bui, T. D., Mai, L. D., Tran, B. N. H., Tran, T. S., Nguyen, T. V., & Ho-Pham, L. T. (2022). Trends in colorectal cancer incidence in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam (1996–2015): Joinpoint regression and age–period–cohort analyses. Cancer Epidemiology, 77, 102113. 10.1016/j.canep.2022.102113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham, T. H. (2020). Self-care evaluation among patients with ostomies [in Vietnamese]. Journal of 108-Clinical Medicine and Phamarcy, 15, DB11. [Google Scholar]

- Queirós, P. J. P., Vidinha, T. d. S., & Almeida Filho, A. J. (2014). Self-care: Orems theoretical contribution to the nursing discipline and profession. Revista de Enfermagem, 4(3), 157-163. 10.12707/RIV14081 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ran, L., Jiang, X., Qian, E., Kong, H., Wang, X., & Liu, Q. (2016). Quality of life, self-care knowledge access, and self-care needs in patients with colon stomas one month post-surgery in a Chinese Tumor Hospital. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 3(3), 252-258. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2016.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabea, M. T. M., & Shaqueer, T. T. (2021). Effect of self-care program for patients using colostomy at Mansoura City. The Malaysian Journal of Nursing (MJN), 12(3), 76-87. 10.31674/mjn.2021.v12i03.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shanmugam, S., & Anandhi, D. (2016). Assess the knowledge, attitude and practice on ostomy care among ostomates attending stoma clinic. Asia Pacific Journal of Research, 1(38), 201-203. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C., Santos, C., Brito, A., Cardoso, T., & Lopes, J. (2018). Self-care competence of patients with an intestinal stoma in the preoperative fase. Journal of Nursing Referência (Revista de Enfermagem Referência), 4(18), 39-50. 10.12707/RIV18026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silva, N. M., Santos, M. A. d., Rosado, S. R., Galvão, C. M., & Sonobe, H. M. (2017). Psychological aspects of patients with intestinal stoma: Integrative review1. Revista Latino-Americana de Enfermagem, 25. 10.1590/1518-8345.2231.2950 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viet Nam General Statistics Office . (2020). Completed results of the 2019 Viet Nam population and housing census. https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2020/11/completed-results-of-the-2019-viet-nam-population-and-housing-census/

- Vo, T. T. T. (2019). Assessment the knowledge, attitude and practice of patient self-care on stoma at hospitals in Southern Vietnam [in Vietnamese]. Ho Chi Minh City Journal of Medicine, 23(5), 218-223. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, M. C. S., Ding, H., Wang, J., Chan, P. S. F., & Huang, J. (2019). Prevalence and risk factors of colorectal cancer in Asia. Intestinal Research, 17(3), 317-329. 10.5217/ir.2019.00021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu, S., Zhang, Z., Wang, A., Zhu, J., Tang, H., & Zhu, X. (2018). Effect of self-efficacy intervention on quality of life of patients with intestinal stoma. Gastroenterology Nursing, 41(4), 341-346. https://doi.org/10.1097%2FSGA.0000000000000290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.