Abstract

Objective:

This study aims to retrospectively compare the stress map of the lung with pulmonary function test (PFT) results in lung cancer patients and to evaluate the potential of the stress map as an imaging biomarker for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).

Methods:

25 lung cancer patients with pre-treatment four-dimensional CT (4DCT) and PFT data were retrospectively analysed. PFT metrics were used to diagnose obstructive lung disease. For each patient, forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1 % predicted) and the ratio of FEV1 and forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) were recorded. 4DCT and biomechanical model-deformable image registration (BM-DIR) were used to obtain the lung stress map. The relationship between the mean of the total lung stress and PFT data was evaluated, and the COPD classification grade was also evaluated.

Results:

The mean values of the total lung stress and FEV1 % predicted showed a significant strong correlation [R = 0.833, (p < 0.001)]. The mean values and FEV1/FVC showed a significant strong correlation [R = 0.805, (p < 0.001)]. For the total lung stress, the area under the curve and the optimal cut-off value were 0.94 and 510.8 Pa for the classification of normal or abnormal lung function, respectively.

Conclusion:

This study has demonstrated the potential of lung stress maps based on BM-DIR to accurately assess lung function by comparing them with PFT data.

Advances in knowledge:

The derivation of stress map directly from 4DCT is novel method. The BM-DIR-based lung stress map can provide an accurate assessment of lung function.

Introduction

According to the latest global cancer statistics, lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide. 1 Non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) accounts for 80–85% of primary lung malignancies. Radiotherapy is used to treat many lung cancer patients. However, radiation pneumonitis occurs in up to 30% of lung cancer patients receiving radiotherapy and is sometimes a potentially fatal toxicity. 2–4 Lung functional-avoidance treatment planning using intensity-modulated radiation therapy techniques has been reported to spare higher functioning lung regions to reduce the risk of toxicity. 5

The primary function of the lung is the process of gas exchange, which is related to ventilation and perfusion in the lung. 6 Various modalities for pulmonary ventilation and perfusion imaging include dual-energy CT, MRI, single-photon emission CT (SPECT), and positron emission tomography (PET). Furthermore, CT ventilation images (CTVI) can also be acquired through a novel technique based on four-dimensional CT (4DCT) via deformable image registration (DIR) and quantitative analysis. This is a non-invasive technique for diagnosing pulmonary function via image processing. To verify CTVI, many studies have reported correlation between CTVI and standard lung function images, such as MRI, 7 SPECT ventilation/perfusion, 8–10 and PET using 68Ga-labeled pseudo-gas. 11 However, these studies reported that a voxel-by-voxel correlation between CTVI and SPECT was weak and highly variable for SPECT 8,12 and was found to be moderate for PET. 11

Pulmonologists employ spirometry as a standard pulmonary functional test (PFT) to diagnose lung function; it is an established method for evaluating lung function. Radiation oncologists can also use PFT data to evaluate the lung function of patients before radiation therapy 13 because chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is a risk factor for radiation pneumonitis in lung cancer patients. 14,15 Several researchers have reported that the pulmonary function of CTVI is moderately correlated with that of spirometry, and CTVI provides a reliable assessment of lung function. 9,16

Also, the percentage of low attenuation areas (% LAA-950insp; the percentage of lung voxels below −950 Hounsfield unit (HU) in end-inspiration, % LAA-856exp; the percentage of lung voxels below −856 HU in end-expiration) were commonly used to diagnose emphysema and gas trapping, which are components of COPD. 17,18 The stress distribution in tissue was quantified using ultrasounds and MRI. 19 However, owing to the air and motion of the lung, it is difficult to implement lung stress maps using conventional method. 20 Recently, Cazoulat et al reported that stress maps obtained using biomechanical model-based DIR (BM-DIR) of the lung were more representative of pulmonary function than CTVI in comparison with SPECT and could be an effective lung ventilation metric. 21 However, there are only a few reports comparing the PFT of spirometry to the stress map of the lung based on BM-DIR. In addition, this stress map has not yet been fully investigated for lung cancer patients with COPD.

The purpose of this study is to retrospectively compare the stress map of the lung with spirometry as a PFT in lung cancer patients and to evaluate the potential of the stress map as an imaging biomarker for COPD.

Methods and materials

Patient data

25 lung cancer patients who underwent 4DCT scans for radiotherapy treatment planning were retrospectively analysed. Table 1 summarises the patient characteristics.

Table 1.

Patient and clinical characteristics

| Parameter | Median (range) or n |

|---|---|

| Age (y) | 77 (61–90) |

| Sex | |

| Female | 6 |

| Male | 19 |

| Smoking status | |

| Yes | 24 |

| No | 1 |

| Lung function | |

| GOLD 0 (normal) | 3 |

| GOLD 1 | 5 |

| GOLD 2 | 12 |

| GOLD 3 | 5 |

| FEV1 (%pred) | 66.9 (40.3–92.6) |

| FVC (%pred) | 93.3 (76.3–133.3) |

| FEV1/FVC (%) | 60.5 (25.8–71.6) |

| Lung tumour stage | |

| I | 15 |

| II | 0 |

| III | 10 |

| IV | 0 |

| Treatment technique | |

| SBRT | 15 |

| VMAT | 10 |

GOLD, global initiative for chronic obstructive lung disease; FEV1, forced expiratory volume in 1 s; FVC, forced vital capacity; SBRT, stereotactic body radiotherapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy.

The usage of patients’ data was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Yamaguchi University Hospital (#2022–014), and written informed consent was waived because of the retrospective design. This retrospective study was performed according to the relevant institutional guidelines and regulations outline. All data used in this study were anonymised. PFTs use spirometry to measure airflow and are a standard method for measuring lung function. PFT data were acquired within 2 months, before radiation treatment.

Immobilisation and 4DCT acquisition

Each patient was immobilised in the supine position, with the arms positioned above the head. A Vac-Lok system (CIVCO Medical Solutions, Coralville, MD) was used to immobilise the patients.

4DCT images were acquired around the whole lung with a 20-slice CT scanner (SOMATOM Definition AS; Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany), under free breathing for radiation treatment planning, while the respiratory signal was monitored with the real-time position management system (RPM, Varian Medical Systems, Palo Alto, CA). The acquisition parameters of 4D-CT were as follows: tube voltage = 120 kV; tube current = 80 mA; slice thickness = 2.0 mm; axial field of view = 500 mm and axial pixel size = 0.98×0.98×0.98 mm.

After the 4DCT scan, the CT image set was synchronised with the respiratory signal, and the CT images were retrospectively sorted into the 10 phase bins of the respiratory signals acquired using the RPM system.

Pulmonary function test data

PFTs use spirometry to measure airflow and are an established method of measuring lung function. PFTs were performed with high accuracy and reproducibility by spirometry (CHESTAC-8800 DN type, Chest Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) following to the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society. 22 Pulmonologists routinely use PFT metrics to diagnose lung diseases such as asthma and COPD. For each patient, the forced expiratory volume in 1 s (FEV1) and the ratio of FEV1 to forced vital capacity (FEV1/FVC) were recorded. PFT metrics were shown in a percentage of the predicted values on normal or healthy subjects with the same anthropomorphic characteristics as those of the patient being tested. 23

In general, 70% of the FEV1/FVC ratio is used as a threshold for separating normal and abnormal results. 24 Furthermore, COPD stage was classified using the percentage of predicted FEV1 (FEV1 % predicted) according to the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) report. 25 The diagnosis was performed by pulmonologists with at least 30 years of experience, who classified the COPD stage.

Computation of stress map of lung based on the biomechanical model-based deformable image registration

Figure 1 shows the study design schematic. The lung regions were segmented on CT images during inhalation and exhalation phases. Voxels with a HU greater than −200 were excluded during segmentation. The trachea and large airways were subsequently removed from the segmented lung structures. Segmented lung structures in the inhalation and exhalation phases were constructed as mesh structures. The segmented lung structures during inhalation were meshed with four-node tetrahedron elements, and the rigid surfaces of the segmented lung structures during exhalation were meshed with three-node triangular shell elements. Both mesh resolutions were set to 5 mm. CT images at inhalation were smoothed using a Gaussian filter with a 2 mm radius to ensure a smooth distribution of stress in the mesh.

Figure 1.

Schematic of the study design. Lung regions were segmented on the CT images at the inhalation and exhalation phases. Segmented lung structures at the end-inhalation and end-exhalation phases were constructed as mesh structures. The heterogeneous Young’s modulus was assigned to the tetrahedral mesh structure of the lung at the inhalation phase. Poisson’s ratio was set to 0.4 for biomechanical model-based deformable image registration. The lung parenchyma was assumed to be a compressible, non-linearly elastic, heterogeneous continuum, modelled with a Neo-Hookean model. The stress map distributions were calculated using finite-element analysis based on the deformable vector fields and were resampled on the CT resolutions. Simultaneously, CTVIs were calculated using computed deformable vector fields. The percentage of lung voxels below −950 HU in end-inspiration of 4DCT was calculated (% LAA-950insp). Additionally, the percentage of lung voxels below −856 HU in end-expiration of 4DCT was calculated (% LAA-856exp). The stress maps, CTVI, % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp were compared to the pulmonary lung function test data. 4DCT, four-dimensional CT; CTVI, CT ventilation image; HU, Hounsfiled unit; LAA, low attenuation area.

Different elastic properties were assigned to different parts of the lung and the stress map was computed through finite-element analysis, as shown in Figure 2. To estimate the spatial distribution of Young’s modulus, a linear relationship was assumed with the density of lung tissue given by the HU in the CT images in the inhalation phase. Voxels with HU below −950 were considered as only air. Those with HU above −200 were considered as the stiffness tissue. The stiffness in all the other voxels of the lung was assumed to be linearly proportional to the corresponding HU. The heterogeneous Young’s modulus was assigned to the tetrahedral mesh structure of the lung in the inhalation phase. Those ranged from 1 kPa for air to a maximum of 20 kPa for the lung tissue stiffness, such as fibrosis, to accurately calculate the stress distribution of the lung tissue owing to the deformation imposed by the boundary condition. 21 Poisson’s ratio was set to 0.4 for BM-DIR. 26 The lung parenchyma was assumed to be a compressible, non-linearly elastic, heterogeneous continuum; therefore, a Neo-Hookean model was used to model the lung. 27 BM-DIR was performed to simulate the displacement vector field (DVF) of all nodes of the mesh using a finite-element analysis software (Radioss, Altair Engineering, Troy, MI).

Figure 2.

Assignment of different elastic properties in lung for finite-element analysis and the computation of the stress map.

The stress map distributions were calculated via finite-element analysis based on the simulated DVF. Furthermore, the stress map distributions were resampled on the CT resolution to evaluate the lung function on CT images. The computed stress map was compared to pulmonary lung function test data. Furthermore, details on the calculation of stress map are presented in Supplementary Material 1.

Computation of 4DCT ventilation images

CTVI based on the change in HU during respiration was calculated using the inverse of the DVF from BM-DIR using Equation (1) 11

| (1) |

where and are the CT images during exhalation and inhalation, respectively; is the displacement vector at the corresponding voxel coordinates Although there are several reports on the width of Gaussian filters, 28,29 the was smoothed using a Gaussian filter with a width of 5×5×5 voxels, to match the stress map.

Computation of emphysema and gas trapping regions on 4DCT in end-inspiration and end-exhalation

The % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp of 4DCT images were calculated because they are well accepted as metrics for quantifying the emphysema and gas components of COPD, respectively. 17,18

Statistical analysis

The accuracy of BM-DIR was evaluated using the dice similarity coefficient (DSC), target registration error (TRE), Hausdorff distance (HD), and mean distance to agreement (MDA). Details are presented in Supplementary Material 2.

The relationships between the mean of the total lung stress and the FEV1 % precited, FEV1/FVC were evaluated and compare the relationship between the mean of the total lung CTVI, % LAA-950insp, % LAA-856exp, and the FEV1 % predicted, FEV1/FVC. Furthermore, relationships between the mean stress, CTVI metrics of the total lung, % LAA-950insp, % LAA-856exp, and COPD classification grade were evaluated. For all statistical relationship analysis, the Pearson correlation coefficients were calculated.

A binary COPD classification was first determined based on the GOLD report: 0 or 1 corresponded to normal lung function and 2 or 3 corresponded to abnormal lung function. 30 To evaluate the diagnostic ability of COPD for the stress map, the area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) was calculated. The optimal cut-off values were determined using the Youden index. 31

Results

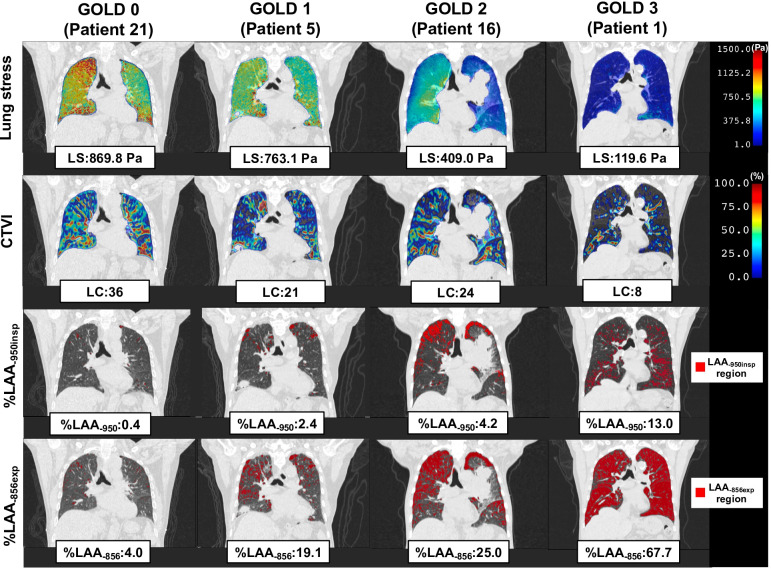

Figure 3 shows typical cases of the total lung stress, total lung CTVI metrics, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp for GOLD report-based classification. As the COPD grade increased, the total lung stress decreased. Total lung CTVI metrics, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp also showed a trend similar to that of the total lung stress.

Figure 3.

Typical cases of the total LS, total lung CTVI metrics (LC), the percentage of low attenuation areas (% LAA-950insp; the percentage of lung voxels below −950 HU in end-inspiration, % LAA-856exp; the percentage of lung voxels below −856 HU in end-expiration) for GOLD report-based classification. As the COPD grade increased, the LS decreased. A similar trend was exhibited by LC, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTVI, CT ventilation image; HU, Hounsfield unit; LAA, low attenuation area; LS, lung stress.

For all patients, the mean ± standard deviation (SD) of DSCs was 0.94 ± 0.01, and those of TRE, HDs, and MDA were 2.44 ± 0.38 mm, 2.01 ± 0.47 mm, and 1.92 ± 0.54 mm, respectively (Supplementary Figure 1).

Figure 4 (a-d) shows the relationship between FEV1 and the mean of the total lung stress, CTVI, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp, respectively. The mean of the total lung stress and FEV1 % predicted showed a significantly strong correlation [R = 0.833, (p < 0.001)]. The mean of the CTVI and FEV1 % predicted showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.430, (p = 0.032)]. The % LAA-950insp and FEV1 % predicted showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.530, (p = 0.007)]. The % LAA-856exp and FEV1 % predicted showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.594, (p = 0.002)].

Figure 4.

(a–d) Relationship between FEV1 and the mean of the total lung stress, CTVI, the % LAA-950insp and the % LAA-856exp, respectively. The mean of the total lung stress and FEV1 % predicted showed significantly strong correlation [R = 0.833, (p < 0001)]. The mean of the CTVI and predicted FEV1 show moderate correlation [R = 0.430, (p = 0.032)]. The % LAA-950insp and FEV1 % predicted showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.530, (p = 0.007)]. The % LAA-856exp and FEV1 % predicted showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.594, (p = 0.002)]. CTVI, CT ventilation image; FEV, forced expiratory volume; LAA, low attenuation area.

Figure 5 (a-d) shows the relationship between FEV1/FVC and the mean of the total lung stress, CTVI, % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp, respectively. The mean of the total lung stress and FEV1/FVC showed a significantly strong correlation [R = 0.805, (p < 0.001)]. The mean of the CTVI and FEV1/FVC showed a low correlation [R = 0.350, (p = 0.086)]. The % LAA-950insp and FEV1/FVC showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.602, (p = 0.002)]. Additionally, the % LAA-856exp and FEV1/FVC showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.673, (p < 0.001)].

Figure 5.

(a–d) Relationship between FEV1/FVC and the mean of the total lung stress, CTVI, the % LAA-950insp and the % LAA-856exp, respectively. The mean of the total lung stress and FEV1/FVC showed significantly strong correlation [R = 0.805, (p < 0.001)]. The mean of the CTVI and FEV1/FVC showed low correlation [R = 0.350, (p = 0.086)]. The % LAA-950insp and FEV1/FVC showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.602, (p = 0.002)]. The % LAA-856exp and FEV1/FVC showed a moderate correlation [R = 0.673, (p < 0.001)]. CTVI, CT ventilation image; FEV, forced expiratory volume; FVC, forced vital capacity; LAA, low attenuation area.

Figure 6 (a-d) shows the relationship between the mean of the total lung stress, CTVI, % LAA-950insp, % LAA-856exp, and the classification of COPD grade. The COPD grade was strongly associated with the mean of the total lung stress [R = 0.873, (p < 0.001)]. The COPD grade was moderately associated with the mean of CTVI [R = 0.454, (p = 0.023)]. The COPD grade was moderately associated with the % LAA-950insp [R = 0.549, (p = 0.004)], while it was strongly associated with the % LAA-856exp [R = 0.708, (p < 0.001)].

Figure 6.

Relationship between the mean of the total lung stress (a), CTVI (b), the % LAA-950insp (c), the % LAA-856exp (d), and classification of COPD grade. The COPD grade is strongly associated with the mean of the total lung stress [R = 0.873, (p < 0.001)]. The COPD grade is moderately associated with the mean of CTVI [R = 0.454, (p = 0.023)]. The COPD grade is moderately associated with the %LAA-950insp [R = 0.549, (p = 0.004)], while it is strongly associated with the % LAA-856exp [R = 0.708, (p < 0.001)]. COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CTVI, CT ventilation image; HU, Hounsfield unit; LAA, low attenuation area.

Table 2 shows the AUC and optimal cut-off values, classifying the lung function as the mean of the total lung stress, total CTVI, the % LAA-950insp, and the % LAA-856exp. For the total lung stress, the AUC and optimal cut-off value were 0.94 and 510.8 Pa, respectively, for the classification of normal or abnormal lung function; for the total CTVI, they were 0.79 and 28.3%, for the % LAA-950insp, they were 0.80 and 3.6%, for the % LAA-856exp, they were 0.87 and 33.2%, respectively.

Table 2.

Area under the curve and optimal cut-off value for classification of lung function as the mean of the entire lung stress, CT ventilation images and low attenuation areas of CT images in inspiration and expiration

| Stress | CTVI | % LAA-950insp | % LAA-856exp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | 0.94 | 0.79 | 0.80 | 0.87 |

| Cut-off (Pa or %) | 510.8 | 28.3 | 3.6 | 33.2 |

AUC, area under curve; CTVI, CT ventilation image; LAA, low attenuation area.

Discussion

In this study, we have demonstrated the lung stress map computed via BM-DIR for 4DCT to compare the PFT spirometry data. Furthermore, the diagnostic ability of lung function for lung stress was compared with that of CTVI, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp. Lung stress correlated better with PFT data than with CTVI, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp. Furthermore, the lung stress was highly diagnostic of COPD.

We calculated the lung stress map based on BM-DIR. The accuracy of the computed lung stress map depended on the BM-DIR accuracy that was evaluated using DSC, TRE, HD, and MDA. These metrics included the tolerance of the American Association of Physicists in Medicine Task Group 132 (Supplementary Material 2 and Supplementary Figure 2). 32 Therefore, the calculation accuracy of the lung stress map was considered adequate.

Additionally, we used 4DCT data for radiation treatment planning. Although these data included small motion artifacts 33 and the image quality may have been inadequate compared to diagnostic CT, our proposed method enabled the derivation of lung stress through computer simulations minimizing the effects of such artifacts.

The correct absolute stress values for normal and abnormal lungs have not been reported in any previous studies. However, in this study, we used the CT stiffness conversion method reported by Cazoulat et al 21 to calculate the absolute stress value of the lung. This method is based on the assumption of a linear relationship between the density of lung tissue given by the HU of the tissue in CT scans and Young’s modulus. Although variations in Young’s modulus exhibited a negligible effect on the stress estimation, 21 the simulated stress value included uncertainty. In addition, they used a linear elastic model to calculate a lung stress map. To calculate the lung stiffness more accurately, a hyperelastic process becomes necessary. 27 Therefore, for computing the lung stress map, we employed the neo-Hookean model, which involves a hyperelastic process. Although there is uncertainty associated with the calculated stress map, our results are closer to the correct value.

Several researchers have reported a relationship between CTVI and PFT data. 9,16 They used the specific metrics (the coefficient of variation (standard deviation/mean) and ventilation V20 (volume of lung ventilation <20% ventilation)) of CTVI to compare the PFT data and showed that CTVI was moderately correlated with PFT data. However, PFT data obtained using spirometry represent the airflow of the total lung rather than that of a part of the lung; thus, in this study, the stress map and CTVI for the total lung were compared with PFT data in this study. Our results indicated that the mean of the total lung stress was significantly strongly correlated with PFT data (FEV1 % predicted; R = 0.833, p < 0.001, FEV1/FVC; R = 0.805, p < 0.001) and showed higher correlation than CTVI (FEV1 % predicted; R = 0.430, p = 0.032, FEV1/FVC; R = 0.350, p = 0.086).

Murphy et al 34 compared % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp with PFT data in 216 COPD patients and reported a correlation coefficient of 0.71–0.91. In this study, % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp were routinely used to quantify the emphysema and gas trapping components of COPD in clinic. 17,18 Our results showed that correlations between % LAA-950insp (FEV1 % predicted; R = 0.530, p = 0.007, FEV1/FVC; R = 0.602, p = 0.002) and % LAA-856exp (FEV1 % predicted; R = 0.594, p = 0.002, FEV1/FVC; R = 0.673, p < 0.001) and PFT data were slightly worse than those of their results because we used the 4DCT image at end-inspiration and end-exhalation. As the stress map was calculated using 4DCT at end-inspiration and end-expiration, the correlation between the stress map and PFT was higher than those of % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp. Furthermore, although there was a two-month duration between treatment planning CT and PFT, lung stress was found to be significantly correlated with PFT data.

In this study, the mean of the total lung stress was strongly correlated with the COPD stage (R = 0.873; p < 0.001). Furthermore, we evaluated the diagnostic capability of COPD using a lung stress map. To classify the normal (GOLD 0–1) and abnormal (GOLD 2–3) lung function, the AUC and optimal cut-off value of the total lung stress were 0.94 and 510.8 Pa, respectively. Hasse et al reported a relationship between lung stiffness and lung function of COPD using 4DCT images. 35 Their results indicated that the low-stiffness regions increased with the GOLD report value. Our results indicated that the mean of the total lung stress decreased with the GOLD report value and were comparable with their results (Figure 6(a)). The emphysematous lung remains hyperinflated during expiration, which limits stretch and recoil. 36,37 Therefore, as the GOLD report value increased, the total lung stress decreased. They also calculated the AUC to evaluate the diagnostic ability of COPD using lung stiffness metrics. Our results were similar to those of previous studies and showed high diagnostic ability. The total lung stress is a potential biomarker of pulmonary function in COPD.

Yamamoto et al 38 reported a strong correlation between CTVI and emphysema; therefore, CTVI may be a potential imaging biomarker for COPD. Our results showed that the mean of the total lung CTVI was moderately correlated with the COPD stage (R = 0.454; p = 0.023), and the AUC was 0.85 for the classification of normal and abnormal lung function. However, the total lung stress showed a higher diagnostic capability for COPD than CTVI and was highly correlated with the COPD stage.

Murphy et al 34 also demonstrated the high correlation between % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp and COPD stage. Our results showed that these were moderately or strongly correlated with the COPD stage (% LAA-950insp; R = 0549; p = 0.004, % LAA-856exp; R = 0.708; p < 0.001), and the AUCs were 0.80 and 0.87 for the classification of normal and abnormal lung function, respectively. However, the total lung stress showed a higher diagnostic capability for COPD than % LAA-950insp and % LAA-856exp and was highly correlated with the COPD stage.

COPD is both a common and an important independent risk factor for lung cancer 39 , and these diseases are closely linked at the molecular level. 40 In this study, 86% of patients were diagnosed with COPD. Therefore, it is difficult to validate lung stress maps separately for COPD and lung cancer. Although we evaluated patients with COPD and lung cancer complications, our results indicated that the stress map for the total lung was strongly correlated with PFT.

Despite all the valuable conclusions discussed above, this study faces certain limitations. The sample size was small and was collected under stereotactic body radiotherapy or volumetric-modulated radiotherapy settings, resulting in an uneven number of patients within each GOLD group. Therefore, future research should be conducted collecting and analysing mainstream COPD data to further evaluate the diagnostic potential of lung stress map.

In this study, PFTs was golden standard for the diagnosis of COPD. The total lung stress was strongly correlated with PFT data than with CTVI. However, several studies reported that PFTs were not sufficient for the diagnosis of COPD due to uncertainties in measurement accuracy and reproducibility. 41,42 Therefore, we must compare the stress map distribution with the clinical standard SPECT images to validate its usefulness. Cazoulat et al reported that the stress map was significantly stronger and exhibited correlation with the SPECT ventilation than CTVI. 21 The stress maps have the potential to indicate lung function and functional regions more accurately than CTVI and might be useful for functional avoidance radiation therapy.

In addition, Mullikin et al reported that elevated pre-radiation therapy liver stiffness was associated with an increased risk of radiation-induced liver disease. 43 In the future, we will evaluate whether lung stress can be an indicator of radiation-induced lung disease risk.

Conclusions

This study has demonstrated the potential of lung stress maps based on BM-DIR to accurately assess lung function by comparing them with PFT data. The total lung stress presented a significantly stronger correlation with PFT data than with the previously proposed CTVI, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp. Furthermore, a preliminary imaging biomarker for COPD was assessed and found to perform better than CTVI, % LAA-950insp, and % LAA-856exp. Our validation data suggest that the BM-DIR-based lung stress maps can provide an accurate assessment of lung function.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: We thank Medical Physics Research Unit in Yamaguchi University (https://ds0n.cc.yamaguchi-u.ac.jp/~medphys/) for providing support to accomplish this study.

Funding: This research was supported by the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) KAKENHI Grant number 22K07667 (TS).

Contributor Information

Takehiro Shiinoki, Email: shiinoki@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Koya Fujimoto, Email: kouya@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Yusuke Kawazoe, Email: yusuke.kawazoe.san@gmail.com.

Yuki Yuasa, Email: yuuki-y@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Miki Kajima, Email: mkajima@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Yuki Manabe, Email: ymanabe@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Tsunahiko Hirano, Email: tsuna@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Kazuto Matsunaga, Email: kazmatsu@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

Hidekazu Tanaka, Email: h-tanaka@yamaguchi-u.ac.jp.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer Statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2018; 68: 394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Palma DA, Senan S, Tsujino K, Barriger RB, Rengan R, Moreno M, et al. Predicting radiation Pneumonitis after Chemoradiation therapy for lung cancer: an international individual patient data meta-analysis. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2013; 85: 444–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2012.04.043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Marks LB, Bentzen SM, Deasy JO, Kong F-MS, Bradley JD, Vogelius IS, et al. Radiation dose-volume effects in the lung. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2010; 76: S70–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2009.06.091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mehta V. Radiation Pneumonitis and pulmonary fibrosis in non-small-cell lung cancer: pulmonary function, prediction, and prevention. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2005; 63: 5–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2005.03.047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Siva S, Thomas R, Callahan J, Hardcastle N, Pham D, Kron T, et al. High-resolution pulmonary ventilation and perfusion PET/CT allows for functionally adapted intensity modulated radiotherapy in lung cancer. Radiother Oncol 2015; 115: 157–62. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Petersson J, Glenny RW. Gas exchange and ventilation-perfusion relationships in the lung. Eur Respir J 2014; 44: 1023–41. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00037014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mathew L, Wheatley A, Castillo R, Castillo E, Rodrigues G, Guerrero T, et al. Hyperpolarized (3)He magnetic resonance imaging: comparison with four-dimensional X-ray computed tomography imaging in lung cancer. Acad Radiol 2012; 19: 1546–53. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2012.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Castillo R, Castillo E, McCurdy M, Gomez DR, Block AM, Bergsma D, et al. Spatial correspondence of 4D CT ventilation and SPECT pulmonary perfusion defects in patients with malignant airway stenosis. Phys Med Biol 2012; 57: 1855–71. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/57/7/1855 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yamamoto T, Kabus S, Lorenz C, Mittra E, Hong JC, Chung M, et al. Pulmonary ventilation imaging based on 4-dimensional computed tomography: comparison with pulmonary function tests and SPECT ventilation images. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; 90: 414–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Vinogradskiy Y, Koo PJ, Castillo R, Castillo E, Guerrero T, Gaspar LE, et al. Comparison of 4-dimensional computed tomography ventilation with nuclear medicine ventilation-perfusion imaging: a clinical validation study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2014; 89: 199–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2014.01.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kipritidis J, Siva S, Hofman MS, Callahan J, Hicks RJ, Keall PJ. Validating and improving CT ventilation imaging by correlating with ventilation 4D-PET/CT using 68Ga-labeled nanoparticles . Med Phys 2014; 41: 011910. doi: 10.1118/1.4856055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Castillo R, Castillo E, Martinez J, Guerrero T. Ventilation from four-dimensional computed tomography: density versus Jacobian methods. Phys Med Biol 2010; 55: 4661–85. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/55/16/004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Timmerman R, McGarry R, Yiannoutsos C, Papiez L, Tudor K, DeLuca J, et al. Excessive toxicity when treating central tumors in a phase II study of stereotactic body radiation therapy for medically inoperable early-stage lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 4833–39. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.5937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kimura T, Togami T, Takashima H, Nishiyama Y, Ohkawa M, Nagata Y. Radiation Pneumonitis in patients with lung and Mediastinal tumours: a retrospective study of risk factors focused on pulmonary emphysema. Br J Radiol 2012; 85: 135–41. doi: 10.1259/bjr/32629867 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Uchiyama F, Nakayama H, Takeda Y, Wang W, Minamimoto R, Tajima T. Risk of radiation Pneumonitis in patients with emphysema after stereotactic body radiotherapy for non-small cell lung cancer assessed by quantitative CT. Mol Clin Oncol 2020; 13(): 3. doi: 10.3892/mco.2020.2073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brennan D, Schubert L, Diot Q, Castillo R, Castillo E, Guerrero T, et al. Clinical validation of 4-dimensional computed tomography ventilation with pulmonary function test data. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2015; 92: 423–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2015.01.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gevenois PA, De Vuyst P, de Maertelaer V, Zanen J, Jacobovitz D, Cosio MG, et al. Comparison of computed density and microscopic Morphometry in pulmonary emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1996; 154: 187–92. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.154.1.8680679 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Galbán CJ, Han MK, Boes JL, Chughtai KA, Meyer CR, Johnson TD, et al. Computed tomography-based biomarker provides unique signature for diagnosis of COPD phenotypes and disease progression. Nat Med 2012; 18: 1711–15. doi: 10.1038/nm.2971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pepin KM, Ehman RL, McGee KP. Magnetic resonance Elastography (MRE) in cancer: technique, analysis, and applications. Prog Nucl Magn Reson Spectrosc 2015; 90–91: 32–48. doi: 10.1016/j.pnmrs.2015.06.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Negahdar M, Fasola CE, Yu AS, von Eyben R, Yamamoto T, Diehn M, et al. Noninvasive pulmonary Nodule Elastometry by CT and Deformable image registration. Radiother Oncol 2015; 115: 35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2015.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cazoulat G, Balter JM, Matuszak MM, Jolly S, Owen D, Brock KK. Mapping lung ventilation through stress maps derived from Biomechanical models of the lung. Med Phys 2021; 48: 715–23. doi: 10.1002/mp.14643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Miller MR, Hankinson J, Brusasco V, Burgos F, Casaburi R, Coates A, et al. Standardisation of Spirometry. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: 319–38. doi: 10.1183/09031936.05.00034805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Beckles MA, Spiro SG, Colice GL, Rudd RM, American College of Chest Physicians . The physiologic evaluation of patients with lung cancer being considered for Resectional surgery. Chest 2003; 123: 105S–114S. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1_suppl.105s [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Celli BR, MacNee W, Force AT. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J 2004; 23: 932–46. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00014304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. GOLD . Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease. Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease. . 2022.

- 26. Cazoulat G, Owen D, Matuszak MM, Balter JM, Brock KK. Biomechanical Deformable image registration of longitudinal lung CT images using vessel information. Phys Med Biol 2016; 61: 4826–39. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/61/13/4826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Han L, Dong H, McClelland JR, Han L, Hawkes DJ, Barratt DC. A hybrid patient-specific Biomechanical model based image registration method for the motion estimation of lungs. Medical Image Analysis 2017; 39: 87–100. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2017.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kida S, Bal M, Kabus S, Negahdar M, Shan X, Loo BW, et al. CT ventilation functional image-based IMRT treatment plans are comparable to SPECT ventilation functional image-based plans. Radiother Oncol 2016; 118: 521–27. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2016.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kipritidis J, Tahir BA, Cazoulat G, Hofman MS, Siva S, Callahan J, et al. The VAMPIRE challenge: A multi-institutional validation study of CT ventilation imaging. Med Phys 2019; 46: 1198–1217. doi: 10.1002/mp.13346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Papaioannou M, Pitsiou G, Manika K, Kontou P, Zarogoulidis P, Sichletidis L, et al. COPD assessment test: a simple tool to evaluate disease severity and response to treatment. COPD 2014; 11: 489–95. doi: 10.3109/15412555.2014.898034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. YOUDEN WJ. Index for rating diagnostic tests. Cancer 1950; 3: 32–35. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Brock KK, Mutic S, McNutt TR, Li H, Kessler ML. Use of image registration and fusion Algorithms and techniques in radiotherapy: report of the AAPM radiation therapy committee task group No.132. Med Phys 2017; 44: e43–76. doi: 10.1002/mp.12256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yamamoto T, Langner U, Loo BW, Shen J, Keall PJ. Retrospective analysis of artifacts in four-dimensional CT images of 50 abdominal and Thoracic radiotherapy patients. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008; 72: 1250–58. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2008.06.1937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Murphy K, Pluim JPW, van Rikxoort EM, de Jong PA, de Hoop B, Gietema HA, et al. Toward automatic regional analysis of pulmonary function using inspiration and expiration Thoracic CT. Med Phys 2012; 39: 1650–62. doi: 10.1118/1.3687891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Hasse K, Neylon J, Min Y, O’Connell D, Lee P, Low DA, et al. Feasibility of deriving a novel imaging biomarker based on patient-specific lung elasticity for characterizing the degree of COPD in lung SBRT patients. Br J Radiol 2019; 92: 20180296. doi: 10.1259/bjr.20180296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Papandrinopoulou D, Tzouda V, Tsoukalas G. Lung compliance and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pulm Med 2012; 2012: 542769. doi: 10.1155/2012/542769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Leslie MN, Chou J, Young PM, Traini D, Bradbury P, Ong HX. How do mechanics guide fibroblast activity? complex disruptions during emphysema shape cellular responses and limit research. Bioengineering (Basel) 2021; 8(): 110. doi: 10.3390/bioengineering8080110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Yamamoto T, Kabus S, Klinder T, Lorenz C, von Berg J, Blaffert T, et al. Investigation of four-dimensional computed tomography-based pulmonary ventilation imaging in patients with emphysematous lung regions. Phys Med Biol 2011; 56: 2279–98. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/56/7/023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Christmas T, Black PN, Metcalf P, Gamble GD. COPD prevalence is increased in lung cancer, independent of age, sex and smoking history. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 380–86. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00144208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Durham AL, Adcock IM. The relationship between COPD and lung cancer. Lung Cancer 2015; 90: 121–27. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.08.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Belzer RB, Lewis RJ. The practical significance of measurement error in pulmonary function testing conducted in research settings. Risk Anal 2019; 39: 2316–28. doi: 10.1111/risa.13315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Andreeva E, Pokhaznikova M, Lebedev A, Moiseeva I, Kuznetsova O, Degryse JM. Spirometry is not enough to diagnose COPD in Epidemiological studies: a follow-up study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2017; 27(): 62. doi: 10.1038/s41533-017-0062-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Mullikin TC, Pepin KM, Evans JE, Venkatesh SK, Ehman RL, Merrell KW, et al. Evaluation of pre-treatment MR Elastography for the prediction of radiation-induced liver disease. Adv Radiat Oncol 2021; 6(): 100793. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2021.100793 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.