Actinic keratoses (AKs) are precancerous lesions, defined by the presence of atypical keratinocytes limited to the epidermis without invasion on histopathology (1). They rarely develop over the eyelids, and hardly ever over the ocular surface. In both situations, treatment can be very challenging, given the proximity to the eye and the anatomical high risk of progression. However, disease control and remission are usually easily achieved (2, 3).

We report here a very unusual presentation of aggressive actinic keratoses of the eyelid secondarily involving the conjunctiva, which was refractory to numerous topical therapies and surgeries, leading to complete loss of the eye despite the absence of invasive growth.

CASE REPORT

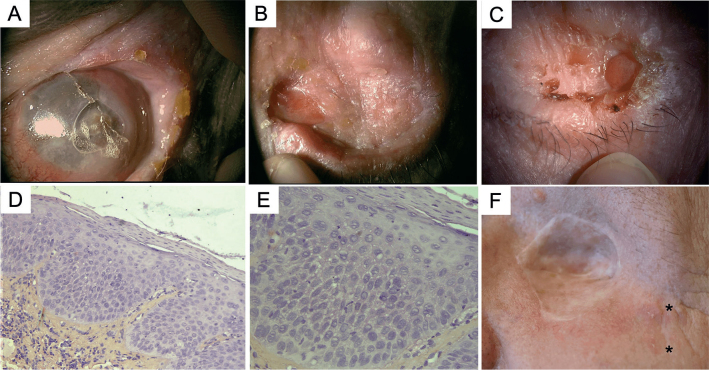

A 59-year-old man presented in 2010, with a 10-year history of progressive asymptomatic scaly erythematous plaques over the left upper eyelid (Fig. 1A, B). An early biopsy was non-specific, but a recent one was consistent with actinic keratosis. There was no previous history of altered immune status, direct radiation therapy, or carcinogenic exposure, except for chronic sun exposure on the left side possibly through the car window. Complete surgical excision and reconstructive surgery were performed, and histopathological analysis showed an actinic keratosis with a small focus of micro-invasive squamous cell carcinoma (SCC). The patient was in complete remission for 5 years, then similar lesions started to appear over the remnant of the eyelid, followed by conjunctival involvement (Fig. 1C, D). Several biopsies revealed actinic keratosis and low-grade conjunctival intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) (Fig. 1E, F).

Fig. 1.

(a, b) Initial clinical presentation in 2010, with a scaly erythematous plaque, affecting the free border of the left eyelid and extending upward to the eyebrow, initially without conjunctival involvement. (c–d) Relapse in 2015, with conjunctival involvement: papillomatous hyperaemic plaques of the temporal bulbar conjunctiva, extending from the limbus to the lateral canthus and to the superior palpebral conjunctiva. (e, f) Histological analysis showed evidence of actinic keratosis without evidence of invasion (e: haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) ×4; f: H&E ×10, inset ×40).

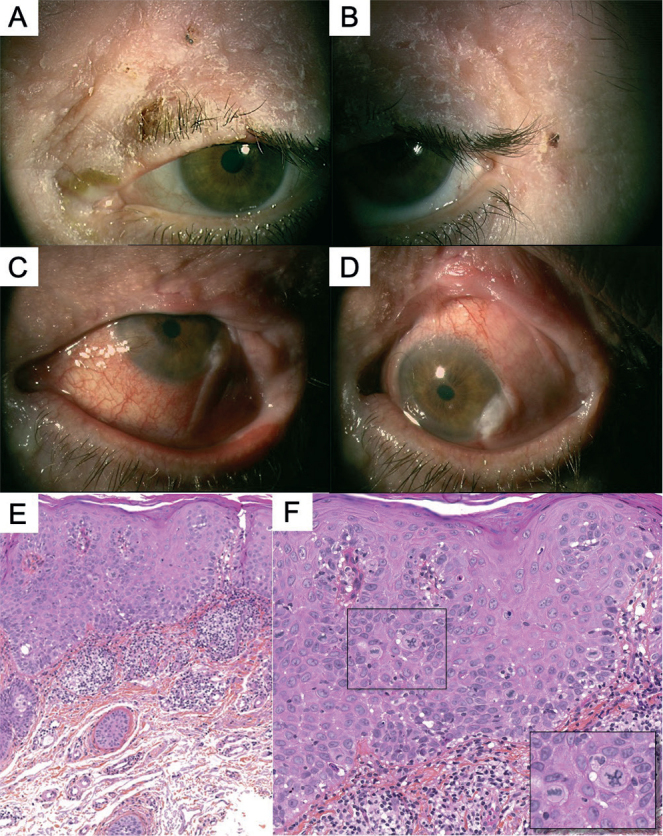

Over the following 4 years, numerous treatments failed to prevent skin keratotic recurrences, including surgery, cryotherapy, 5-fluorouracil cream, imiquimod, and photodynamic therapy. On the conjunctiva, neither interferon alpha 2b or topical mitomycin-C were effective. Because of severe corneal alterations and loss of function of the eye (Fig. 2A), evisceration was performed and healing of the wound by secondary intention was achieved. However, persistent AKs continued to develop over the neoepithelium (Fig. 2B, C). Iterative sampling and histopathological analysis always showed AKs and focal lesions of low-grade CIN, but with no evidence of invasion (Fig. 2D, E). Immunohistochemical analysis with p16 was negative. Given the recalcitrant disease course, complete orbital exenteration with lateral margins of 5 mm and grafting were performed. Histopathological report described only SCC in situ and foci of intra-epithelial neoplasia without invasion, and the margins were free of lesions. Nevertheless, a few months later, cutaneous AKs started to develop again in proximity to the skin graft (Fig. 2F).

Fig. 2.

(a) Progressive disease despite topical treatment leading to a non-functional eye with excruciating pain. (d, e) Evisceration with reconstructive surgeries (using Cutler Beard flap) were performed in 2016, and histopathological analysis showed conjunctival leukokeratosis with few focal lesions of low-grade intra-epithelial neoplasia but without any evidence of invasion. (b, c) However, new actinic keratoses (AK) continued to appear over the remnant of the eyelid despite many topical treatments over 4 years. (f) Orbital exenteration and grafting were then done, but the patient was still developing cutaneous AK lesions in proximity to the skin graft even 6 months later. (d: H&E, ×4; e: H&E, ×10).

Curiously, the patient never had AKs over other areas of the face and body. Thus, the hypothesis of a local factor predisposing to cancer was raised, as well as the possibility of an unusual variant of AK with malignant potential. Hence, 3 representative samples were selected from the biopsies/excisions done; 1 from the cutaneous eyelid and 2 from the conjunctival lesions, and DNA extraction from the formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues was performed.

Sequencing was performed using a targeted next generation sequencing (NGS) panel, composed of 571 genes of interest in oncology.

Interestingly, all 3 samples shared mutations in SLX4 (c.1420C>T), CDKN2A (c.151-1G>A) and PIK3CA (c.1633G>A), while other mutations TERT (c.146C>T) and TP53 (c.764_766del and c.272 >A) were specific to some lesions. Those mutations were not detected in the normal skin or in constitutional plasma DNA. Human papillomavirus (HPV) analysis using NGS was also performed and confirmed the non-implication of HPV in the development of the lesions.

DISCUSSION

Cutaneous AKs are usually regarded as benign lesions that can spontaneously involute, and controversies remain regarding whether to treat them aggressively. The progression rate to invasive SCC is estimated to range from 0% to 0.53% per lesion-year (1). UV radiation plays a major role, as these precursor lesions already harbour frequent complex carcinogenic mutations in driver genes, such as TP53, CDKN2A, and PIK3CA (4), which are dominated by transitions from cytosine to thymine (C>T) highly reflective of ultraviolet B (UVB) exposure (5, 6).

AKs of the eyelids are rare, and usually have a higher rate of recurrence after surgery (7). An expert consensus has recently proposed a practical treatment algorithm of AKs and low-grade squamous malignancies of the periocular area and eyelid, favouring non-invasive topical treatments, and keeping surgery as a second-line treatment (2).

The ocular surface can also be subject to conjunctival AKs or low-grade CIN in exceedingly rare cases (8–10). Treatment is based on few case reports and consists mainly of excisional biopsies, topical chemotherapy (mitomycin C, 5-fluorouracil) or interferon alpha-2b with relatively good response (3, 9, 11, 12).

The mechanisms for the development of conjunctival AKs remain controversial, with multiple possible implicating factors, such as UV light, chronic inflammation, surface microtrauma, and HPV infection (13, 14). In particular, the role of UV radiation has long been disputed until very recently when the genomic landscape of ocular neoplastic lesions was defined (4). In fact, new evidence showed that ocular and cutaneous neoplasms harbour similar alterations involving genes in DNA repair/cell cycle and development/growth pathways, supporting a common model for neoplasia in UV-exposed epithelia (4, 15).

In this case report, cutaneous and conjunctival specimens shared the same genetic mutations, supporting the clonal nature of these lesions. Those mutations implicated the well-described oncogenic genes: TP53, CDKN2A and PIK3CA (4). We also found the presence of a c.-146C > T mutation in the TERT promoter, which represents a key mechanism for cancer-specific telomerase activation, only recently described in AKs and cutaneous SCC (16, 17). In addition, we report a new UV-signature mutation in the SLX4 gene, which encodes a protein directly implicated in DNA complex repair. Interestingly, SLX4 is altered in 2.55% of all cancers and mutated in 5.73% of melanoma patients, but has not been reported in SCC or its precursor lesions.

In conclusion, to our knowledge, we report here for the first time an unexpected case of AKs occurring over the cutaneous eyelid and the bulbar conjunctiva, with an unusually high relapse rate even after complete surgical excision. It is possible that the identified genetic mutational pattern may be implicated in the aggressive course of the disease. We consider that such situations should be referred to as “keratoses maligna”, in comparison with “lentigo maligna”, which is known for its aggressive behaviour due to its lentiginous spread in the absence of extension beyond the basement membrane.

Footnotes

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

REFERENCES

- 1.Werner RN, Sammain A, Erdmann R, Hartmann V, Stockfleth E, Nast A. The natural history of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169: 502–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Richard MA, Amici JM, Basset-Seguin N, Claudel JP, Cribier B, Dreno B. Management of actinic keratosis at specific body sites in patients at high risk of carcinoma lesions: expert consensus from the AKTeam of expert clinicians. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2018; 32: 339–346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Khan S, Chak M. A rare presentation of actinic keratosis affecting the tarsal conjunctiva and review of the literature. Case Rep Ophthalmol Med 2018; 2018: 4375354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lazo de la Vega L, Bick N, Hu K, Rahrig SE, Silva CD, Matayoshi S, et al. Invasive squamous cell carcinomas and precursor lesions on UV-exposed epithelia demonstrate concordant genomic complexity in driver genes. Mod Pathol 2020; 33: 2280–2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martincorena I, Roshan A, Gerstung M, Ellis P, Van Loo P, McLaren S, et al. Tumor evolution. High burden and pervasive positive selection of somatic mutations in normal human skin. Science 2015; 348: 880–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chitsazzadeh V, Coarfa C, Drummond JA, Nguyen T, Joseph A, Chilukuri S, et al. Cross-species identification of genomic drivers of squamous cell carcinoma development across preneoplastic intermediates. Nat Commun 2016; 7: 12601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lopez-Tizon E, Mencia-Gutierrez E, Garrido-Ruiz M, Gutierrez-Diaz E, Lopez-Rios F. Clinicopathological study of 21 cases of eyelid actinic keratosis. Int Ophthalmol 2009; 29: 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alves LF, Fernandes BF, Burnier JV, Zoroquiain P, Eskenazi DT, Burnier MN, Jr. Incidence of epithelial lesions of the conjunctiva in a review of 12,102 specimens in Canada (Quebec). Arq Bras Oftalmol 2011; 74: 21–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mauriello JA, Jr., Napolitano J, McLean I. Actinic keratosis and dysplasia of the conjunctiva: a clinicopathological study of 45 cases. Can J Ophthalmol 1995; 30: 312–316. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gichuhi S, Macharia E, Kabiru J, Zindamoyen AM, Rono H, Ollando E, et al. Clinical presentation of ocular surface squamous neoplasia in kenya. JAMA Ophthalmol 2015; 133: 1305–1313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowlands MA, Giacometti JN, Servat J, Materin MA, Levin F. Topical imiquimod in the treatment of conjunctival actinic keratosis. Ophthalmic Plast Reconstr Surg 2017; 33: e21–e23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nemet AY, Sharma V, Benger R. Interferon alpha 2b treatment for residual ocular surface squamous neoplasia unresponsive to excision, cryotherapy and mitomycin-C. Clin Exp Ophthalmol 2006; 34: 375–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Woods M, Chow S, Heng B, Glenn W, Whitaker N, Waring D, et al. Detecting human papillomavirus in ocular surface diseases. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 2013; 54: 8069–8078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McDonnell JM, Mayr AJ, Martin WJ. DNA of human papillomavirus type 16 in dysplastic and malignant lesions of the conjunctiva and cornea. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 1442–1446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ramos-Betancourt N, Field MG, Davila-Alquisiras JH, Karp CL, Hernández-Zimbrón LF, García-Vázquez R, et al. Whole exome profiling and mutational analysis of ocular surface squamous neoplasia. Ocul Surf 2020;18: 627–632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Srinivas N, Neittaanmäki N, Heidenreich B, Rachakonda S, Karppinen TT, Grönroos M, et al. TERT promoter mutations in actinic keratosis before and after treatment. Int J Cancer 2020; 146: 2932–2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ventura A, Pellegrini C, Cardelli L, Rocco T, Ciciarelli V, Peris K, et al. Telomeres and telomerase in cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Mol Sci 2019; 20: 1333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]