Summary

Cancer is currently a major public health issue faced by countries around the world. With the progress of medical science and technology, the survival rate of cancer patients has increased significantly and the survival time has been effectively prolonged. How to provide quality and efficient care for the increasingly large group of cancer survivors with limited medical resources will be a key concern in the field of global public health in the future. Compared to developed countries, China's theoretical research and practical experience in care for cancer survivors are relatively limited and cannot meet the multi-faceted and diverse care needs of cancer patients. Based on the existing models of care worldwide, the current work reviews care for cancer survivors in China, it proposes considerations and suggestions for the creation of models of cancer care with Chinese characteristics in terms of optimizing top-level system design, enhancing institutional mechanisms, accelerating human resource development, and enhancing self-management and social support for patients.

Keywords: cancer survivors, model of care, quality of life, survivorship, China

Introduction

Cancer is a major public health problem worldwide, with an estimated 19.3 million new cases and nearly 10 million deaths occurring in 2020. The current state of cancer prevention and control in China is dire, with a higher disease burden than in other countries. China is estimated to account for 23.7% of new cancer cases and 30.2% of deaths worldwide (1). With the development of cancer screening, treatment modalities, and rehabilitation care, cancer survival rates have gradually improved and the number of survivors has increased. The latest data from the American Centers Society (ACS) in 2023 show that overall cancer mortality in the US fell by 33% between 1991 and 2020, meaning that 3.82 million cancer survivors were saved from dying (2). The National Cancer Centre of China reports that overall cancer survival rates in China are all on the rise, with a 5-year survival rate of approximately 40.5% (3,4).

In China, the most common types of cancer were those of the lung (20.4%), colorectum (10.0%), stomach (9.8%), liver (9.6%), and breast (7.5%), accounting for 57.3% of all new cancer cases. Lung cancer (27.2%), liver cancer (13.9%), and gastric cancer (12.0%) were the three malignant tumors with the highest mortality rates in the general population (5). China is undergoing a transition in cancer where the cancer spectrum is changing from that of a developing country to that of a developed country (6). Highly prevalent cancers are generally characterized by long disease duration and complex treatments, which impose a heavy financial burden of illness on patients' families and society. In 2015, total payments for cancer inpatients reached 177.1 billion RMB, accounting for 4.3% of China's total health costs (6). Huang et al. reported the results of the economic burden of disease for cancer patients in China, where the cost of treatment for cancer patients exceeded annual household income (average annual household income: $8,607 vs. per capita expenditure on medical visits: $,9739); 9.3% of the non-direct medical costs were associated with the disease (7).

In addition to the financial burden, cancer survivors will face many potential long-term or late effects of oncological treatment, such as cardiac dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, and peripheral neuropathy that will severely impact their quality of life. At the same time, the negative effects of the illness such as fear of relapse, fatigue, impacts on sexual and intimate relationships, and impacts on work and social interaction require effective psychosocial care. Several studies have indicated that cancer survivors in China have significant unmet healthcare needs (8,9). Medical resources from medical facilities, oncologists, family doctors, and nurses are not efficiently integrated, and cancer survivors need guidance in self-management. There is a huge gap in the system of care covering the whole population and the whole life cycle (10). Future models of improved care for cancer survivors are expected to focus on both "screening" and "rehabilitation", improving the quality of life, functional outcomes, well-being, and long-term survival of cancer survivors, reducing the risk of recurrence and incidence of new cancer, improving the management of comorbidities, and reducing costs to patients and payers.

Models of care for cancer survivors worldwide

The 2005 Institute of Medicine (IOM) and National Research Council (NRC) consensus study reported four essential components of survivorship care for cancer survivors: i) prevention of recurrent and new cancers, and other late effects; ii) surveillance for cancer spread and recurrence, and for medical and psychosocial effects; iii) intervention for consequences of cancer and its treatment (e.g., medical problems such as lymphedema and sexual dysfunction; symptoms, including pain and fatigue; psychological distress experienced by cancer survivors and their caregivers; and concerns related to employment and insurance); and iv) coordination between specialists and primary care providers to ensure that all of the survivor's health needs are met (e.g., health promotion, immunizations, screening for both cancer and noncancerous conditions, and the care of concurrent conditions) (11,12).

Concerns have been raised about the sustainability of the traditional oncologist-led model of care for cancer survivors, which includes medical oncologists, surgical oncologists, radiation oncologists, and hematologists (13). The increasing number of cancer survivors, the shortage of specialists, the cost constraints of healthcare, and the lack of professional nursing experience in primary care are all affecting the unmet needs of cancer survivors and challenging traditional models of medical care (14). To ensure efficient and continuous care for cancer survivors, a variety of models of care are also being actively explored in developed countries including general practitioner-led follow-up care models, shared care models, and oncology nurse-led care models (Table 1). Other complementary models include long-term follow-up clinics, self-support management, and integrated multidisciplinary rehabilitation (10,15). These new models encouraged non-oncology physician groups, multiple stakeholders in cancer care, and survivors themselves to join the system of care for cancer survivors (16). Improved models of care contribute to the development of "value-based care (VBC)" and promote efficient and collaborative models of cancer care (17).

Table 1. Models of care for cancer survivors and their characteristics.

| Model of care | Model type | Characteristics | Provider | Advantages | Suitable patients |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Major models | Specialist-led care | ● Based on oncologists and large cancer centers; | Cancer specialists | ● Highly specialized care; | ● Patients at higher risk of recurrence/new cancer; |

| ● Provides targeted treatment for patients in the acute phase of cancer and follow-up care for post-cancer survival. | ● Provides continuous treatment and care. | ● Patients with complex cancer. | |||

| General practitioner-led care | Patients receive survivorship care mainly or only in primary care facilities. | Primary care providers | ● Easy access for patients; ● Primary care providers are more familiar with the patient's health status; ● Highly cost-effective. |

● Patients with early-stage breast cancers/colorectal cancer/ prostate cancer/melanoma; ● Other cancer survivors with a low risk of recurrence and late effects of treatment. |

|

| Shared care | Oncologists and general practitioners work in collaboration to provide specialized and continuous care for cancer patients. | Cancer specialists and general practitioners | ● Highly specialized care; ● Provide continuous treatment and care; ● Higher patient satisfactory; ● Highly cost-effective. |

Most cancer survivors. | |

| Oncology nurse-led care | Trained and qualified oncology nurses provide integrated care for cancer patients, including prevention, assessment, diagnosis, care, follow-up, and education. | Qualified oncology nurses | ● Highly specialized care; ● Higher patient satisfaction; ● Highly cost-effective. |

Cancer survivors with low/medium risk of recurrence and late effects of treatment. | |

| Complementary models | Long-term follow-up clinics | Comprehensive long-term care for cancer survivors. | Multiple medical specialties | ● Highly specialized care; ● Provides continuous treatment and care; ● Long-term follow-up. |

● Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer; ● Patients with rare cancer; ● Groups of cancer patients with complex treatment or severe late effects of treatment. |

| Supported self-management | Development of cancer patients' competencies in symptom management, self-healing, and health behavior development. | Cancer survivors | ● Timely recognition of and response to changes in disease; ● Encouraging healthy behaviors |

Most cancer survivors. | |

| Comprehensive multidisciplinary rehabilitation | A rehabilitation team consisting of staff from different disciplines such as medicine, education, sociology, psychological counseling, and career planning comprehensively assesses and treats the physical and psychological damage to cancer patients due to the disease and the corresponding treatment. | Multidisciplinary rehabilitation team | ● Full cycle of rehabilitation; ● Comprehensive rehabilitation. |

Most cancer survivors. |

Current state of care for cancer survivors in China

Cancer prevention and treatment is an important part of achieving "Healthy China". In 2019, the National Health Commission of China and other government agencies jointly published the Notice on the Issuance of the Healthy China Initiative - A Plan to Implement Cancer Prevention and Treatment (2019-2022), which calls for comprehensive improvement of national cancer prevention and treatment in terms of controlling risk factors, enhancing prevention and treatment capabilities, improving the registration system, promoting early diagnosis and treatment, and increasing scientific and technological research (18).

Similar to the oncologist-led follow-up care model in developed countries, care for cancer survivors in China mainly relies on cancer treatment centers, oncologists, and their medical teams. The main providers of care for cancer survivors in China include tertiary hospitals (or specialist hospitals), secondary hospitals (or rehabilitation centers), community hospitals (or primary hospitals), and nursing facilities (19). Tertiary and secondary hospitals provide specialist care including cancer treatment, symptomatic treatment, and specialized care (20). Some community hospitals provide home follow-up for cancer survivors and use Chinese medicine to help patients relieve their discomfort (21). Nursing facilities provide palliative care and hospice care for terminal cancer survivors. At the same time, other forms of follow-up care are gradually being developed, such as promoting the use of online hospitals, mobile phones, and apps to better monitor and manage cancer survivors' side effects, physical activity levels, daily diet, mental health, etc. (22).

Medical consortia are a forward-looking approach to creating a hierarchical system of medical care in China, promoting the establishment of partnerships between hospitals at different levels to facilitate the optimal allocation of medical resources. Senior oncologists with experience in cancer treatment periodically assist primary care providers in teaching and training at secondary and community hospitals (23). An electronic patient health records system is being set up in China. For newly diagnosed cancer patients, the hospital will report the patient's information to the regional Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) through the Tumor Registry Card for statistical and dynamic health monitoring (24). The "discharge summary" provided by the hospital to the patient will help oncologists at different facilities to better understand the patient's medical history and provide continuity of care for the patient. Some hospitals that have joined the clinical information exchange platform can share and access some of the patient's information (25).

Outlook for care for cancer survivors in China

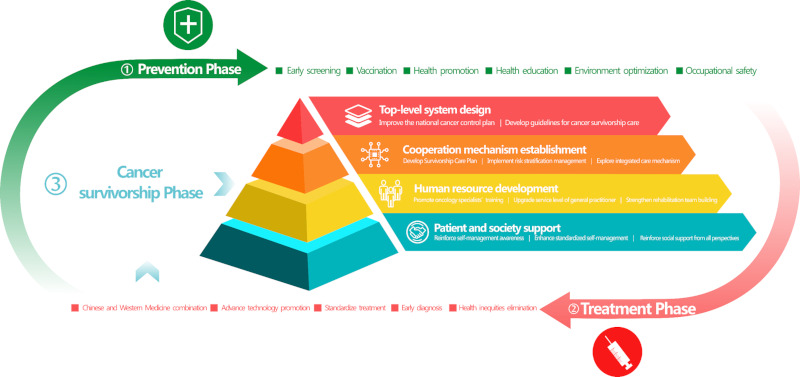

China's system of care for cancer survivors is being gradually improved. In general, cancer survivorship care in China still rely mainly on oncology physicians and their teams, while primary care physicians, nurses, rehabilitation teams, and other non-oncology physician groups play a very limited role in the care of cancer survivors. Care for cancer survivors in China still faces many challenges, including the lack of clear goals and plans for care for cancer survivors at the national level, the overall uneven distribution of healthcare resources, the lack of guidelines and standards of care for cancer survivors, the shortage and varying abilities of care professionals, the serious fragmentation of cancer management, and the lack of continuity of care (26). An imperative task is to create a model of quality care for cancer survivors with Chinese characteristics (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

A model of quality care for cancer survivors with Chinese characteristics.

Optimize the top-level system design

Improve the national cancer control plan

The current national cancer control plan mainly focuses on cancer prevention and treatment but lacks clear goals and plans to care for cancer survivors (18). The system of care for cancer survivors should be an important part of the national cancer control plan. The division of responsibilities among relevant facilities should be clarified to promote collaboration among relevant departments, facilities, and society as a whole.

Develop guidelines on care for cancer survivors

Given China's healthcare system and medical insurance, relevant societies and associations should, in concert with multidisciplinary teams of experts, comprehensively integrate and analyze literature and research with evidence-based ratings and fully consider the actual needs of patients and caregivers to jointly draft and formulate various guidelines on cancer care (27). For young cancer patients, relevant facilities should provide special guidelines on care to better protect the health-related rights of a vulnerable population (28). In addition, due to the uneven distribution of care resources in different provinces and cities, the national government can formulate guidelines on care with resource stratification depending to the supply of care resources and encourage regions to explore appropriate models of care in accordance with local conditions.

Enhancing institutional mechanisms

Develop a survivorship care plan (SCP)

There is still in a gap in the practice of SCPs in China. The formulation and implementation of an efficient SCP for cancer survivors is urgently needed to provide quality care in China. National standardization of SCPs should be promoted based on improvements in relevant guidelines. Steps that need to be taken are to identify for whom an SCP is being formulated, standardizing the formulation process, improving plan details, and incorporating the opinions of healthcare workers, patients, and care-related organizations to promote the formulation and implementation of SCPs in phases in light of conditions in China (29). To evaluate the effectiveness of SCPs, a short-term goal that can be focused on is increasing patients and healthcare workers' awareness of the disease and survival care, and a long-term goal can be to further examine how SCPs affect patients' health outcomes (30,31).

Implement risk stratification

At present, the external conditions have been created for the implementation of risk stratification for cancer patients in China: a multi-level system of medical insurance has been created, insurers have developed strategic purchasing power, the creation of medical consortia has been extensively advanced, hierarchical models of diagnosis and treatment are being created, and the capacity of community hospitals has been continuously improved. Clinical experts and academic scholars should work with relevant societies and associations to formulate and implement guidelines and norms for cancer survival risk stratification. Pilot risk stratification should be promoted in limited areas, its effects should be timely ascertained and evaluated, and the pilot project's scope should be expanded when appropriate (32,33). For developed regions, some care can be included in social/medical insurance, and the reimbursement rate for different levels of facilities can be increased to encourage low-risk patients to follow-up at primary medical and rehabilitation facilities to optimize the allocation of medical and healthcare resources (26). The complementary role of commercial insurance in rehabilitation and health management should be gradually improved.

Exploring mechanisms of integrated care

At present, the capacity of primary healthcare facilities in China is steadily improving. The hierarchical model of diagnosis and treatment is evolving. The time is ripe to explore mechanisms of integrated care for cancer patients (34). To accelerate the creation of an integrated care system for cancer patients, the following aspects could be considered: i) Create consortia for integrated cancer care: Based on existing medical consortia, rehabilitation facilities, nursing homes, hospices, and other related facilities should be included into the consortium, coordination and communication within and among the consortium facilities should be enhanced, triage and referral should be improved, and an integrated cancer treatment and care consortium should be gradually created (35). ii) Explore navigation program for cancer patients: Both healthcare professionals and non-professionals can be recruited as patient navigators. They should provide coordinated, integrated, and continuous navigation to patients by enhancing communication, identifying patient needs, coordinating among institutions, and providing health education (36). iii) Make substantial efforts to encourage the development of information technology: Online healthcare platforms should be continuously improved and cancer patients should be provided convenient care such as remote treatment, disease monitoring, and health education through the use advanced information technology so that different facilities can efficiently communicate and collaborate (37). iv) Establish a mechanism of tracking and evaluation: To improve the patient experience and clinical results, the outcomes of integrated care need to be tracked and evaluated, and mechanisms for tracking and evaluation should be modified and optimized in a timely manner (38).

Accelerate human resource development

Promote training for oncology specialists

In terms of training for oncology specialists, the threshold for admission to oncology-related disciplines can be raised to an appropriate extent to focus more resources on quality students. Strengthen oncology specialty training for students at school and during standardized training. Homogenization of oncology discipline education should be enhanced (39). To foster quality oncology specialists, problem-based learning (PBL), case-based learning (CBL), and multi-disciplinary teams (MDTs) should be combined to create a comprehensive training and evaluation system that includes theoretical foundations, clinical skills, medical ethics, medical regulations, evidence-based medicine, etc. (40). Relevant authorities and corresponding social organizations should gradually clarify the standards of practice for oncology nurses, create and improve the certification system, and comprehensively standardize the training process. Efforts should also be made to enhance the training of oncology nurses in disease prevention and treatment, patient communication and education, and clinical management and research; the professional development of nurses should be promoted to foster specialists in clinical nursing (41,42).

Improve the level of care by general practitioners in the community

General medical education should be considered an important part of medical education, and it should be included in the early training of medical students. The core competency of general practitioners should be comprehensively improved. A system should also be created to train general practitioners in oncology-related expertise, and certification should be strictly controlled and dynamically monitored (43,44). Communication between general practitioners and patients should be continuously enhanced so that patients will gain more trust in their healthcare providers. Efforts should also be made to facilitate efficient collaboration within the general practitioner-led care team so that multidisciplinary team members with a clear division of responsibilities provide quality and continuous care to survivors. In addition, cooperation between regions at different levels of development should be enhanced to eliminate health inequalities and to help improve general medical care in rural and remote areas (45,46).

Strengthen rehabilitation teams

First, the concept of "full-cycle, whole family, whole person rehabilitation" should be integrated into all aspects of rehabilitation training. Pre-habilitation should also be emphasized so that rehabilitation for cancer survivors covers all stages of the disease, from diagnosis to survivorship. Patient-centered rehabilitation should also be encouraged by involving patients in the design and optimization of cancer rehabilitation programs (47). Second, advances should be promoted in rehabilitation medicine and the training of highly specialized rehabilitation personnel (including rehabilitation physicians, physical therapists, occupational therapists, speech therapists, swallowing therapists, psychotherapists, nutritionists, etc.) should be accelerated (48,49). Third, a cooperative teamwork model should be created around rehabilitation physicians working closely with multidisciplinary personnel. The standardized and orderly progression of cancer rehabilitation should be promoted.

Enhance patient self-management and social support

Cancer survivors should be taught that they are the gatekeepers of their own health. They should pay more attention to their physical and mental health and promptly identify circumstances that may indicate recurrent and new cancers (50). They should also actively improve their health literacy regarding cancer and strive to motivate themselves to appropriately modify their emotions, behavior, and circumstances (51). Second, standardized self-management for cancer survivors should be enhanced, which should be incorporated into guidelines on routine survivorship care and survival care plans. Patient self-management capabilities should be assessed in detail and should be incorporated in stages step by step; these capabilities can be capitalized on in different models of care and care scenarios (52). The standardization of self-management should be improved through patient education, standardized training, and the development of mobile applications (53). Research on the effectiveness of self-management by cancer patients should be increased, the effectiveness of self-management should be comprehensively evaluated from multiple perspectives such as clinical outcomes, alleviation of symptoms, and patient experience, and self-management models should be continuously adjusted and optimized for different types of cancer, risk factors, and population characteristics (54). In addition, comprehensive support for cancer patients should be enhanced at the societal level, including provision of information, emotional support, and financial support. On the one hand, friends and relatives of survivors should be encouraged to be more patient and inclusive, discrimination in the workplace should be eliminated, and social care and concern for cancer patients should be increased (55,56). On the other hand, patients should be encouraged to share positive experiences fighting cancer with other patients, scientific knowledge of cancer prevention should be promoted, and patients should be encouraged to value their own self-worth (57,58).

Conclusion

The "Healthy China 2030" plan intends for chronic disease management for the whole population and the whole life cycle to be achieved by 2030 and for the overall 5-year survival rate from cancer to increase by 15%. At present, China has made great achievements in spreading early diagnosis and treatment, establishing a long-term mechanism for screening, standardizing and improving diagnosis and treatment capacity, and steadily improving medical insurance. With cancer treatment entering the era of chronic disease management, accelerating the creation of a model of care for cancer survivors with Chinese characteristics can further improve the patient survival rate, enhance their quality of life, rationally allocate medical resources, and efficiently utilize medical insurance, helping to create a healthy China.

Funding

This study was supported by grants from the China Medical Board for "The study of a home-based supportive care system for cancer patients receiving oral chemotherapy" (No. 20-387) and the Shanghai Municipal Health Commission for "Exploration of chronic disease management model for cancer patients in the post-epidemic era" (No. 202240061).

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1. Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021; 71:209-249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023; 73:17-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Zeng H, Chen W, Zheng R, et al. Changing cancer survival in China during 2003-15: A pooled analysis of 17 population-based cancer registries. Lancet Glob Health. 2018; 6:e555-e567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zheng R, Zhang S, Zeng H, Wang S, Sun K, Chen R, Li L, Wei W, He J. Cancer incidence and mortality in China, 2016. J Natl Cancer Center. 2022; 2:1-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cao M, Li H, Sun D, He S, Yang X, Yang F, Zhang S, Xia C, Lei L, Peng J, Chen W. Current cancer burden in China: Epidemiology, etiology, and prevention. Cancer Biol Med. 2022; 19:1121-1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feng RM, Zong YN, Cao SM, Xu RH. Current cancer situation in China: Good or bad news from the 2018 Global Cancer Statistics? Cancer Commun (Lond). 2019; 39:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huang HY, Shi JF, Guo LW, et al. Expenditure and financial burden for the diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer in China: A hospital-based, multicenter, cross-sectional survey. Chin J Cancer. 2017; 36:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Bu X, Jin C, Fan R, Cheng ASK, Ng PHF, Xia Y, Liu X. Unmet needs of 1210 Chinese breast cancer survivors and associated factors: A multicentre cross-sectional study. BMC Cancer. 2022; 22:135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chen M, Li R, Chen Y, Ding G, Song J, Hu X, Jin C. Unmet supportive care needs and associated factors: Evidence from 4195 cancer survivors in Shanghai, China. Front Oncol. 2022; 12:1054885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jefford M, Howell D, Li Q, Lisy K, Maher J, Alfano CM, Rynderman M, Emery J. Improved models of care for cancer survivors. Lancet. 2022; 399:1551-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. National Research Council, Institute of Medicine, National Cancer Policy Board, et al. From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor: Lost in Transition. Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press;. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 12. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, Health and Medicine Division, Board on Health Care Services; National Cancer Policy Forum. Long-term survivorship care after cancer treatment: Proceedings of a workshop. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dossett LA, Hudson JN, Morris AM, Lee MC, Roetzheim RG, Fetters MD, Quinn GP. The primary care provider (PCP)-cancer specialist relationship: A systematic review and mixed-methods meta-synthesis. CA Cancer J Clin. 2017; 67:156-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Neuman HB, Jacobs EA, Steffens NM, Jacobson N, Tevaarwerk A, Wilke LG, Tucholka J, Greenberg CC. Oncologists' perceived barriers to an expanded role for primary care in breast cancer survivorship care. Cancer Med. 2016; 5:2198-2204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vaz-Luis I, Masiero M, Cavaletti G, et al. ESMO Expert Consensus Statements on Cancer Survivorship: Promoting high-quality survivorship care and research in Europe. Ann Oncol. 2022; 33:1119-1133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Halpern MT, Cohen J, Lines LM, Mollica MA, Kent EE. Associations between shared care and patient experiences among older cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2021; 15:333-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Teisberg E, Wallace S, O'Hara S. Defining and implementing value-based health care: A strategic framework. Acad Med. 2020; 95:682-685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. National Health Commission of China. Notice on the issuance of the Healthy China Initiative - A Plan to Implement Cancer Prevention and Treatment (2019- 2022). http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2019-11/13/content_5451694.htm (Accessed February 8, 2023) (in Chinese) .

- 19. Liu Y, Kong Q, Yuan S, van de Klundert J. Factors influencing choice of health system access level in China: A systematic review. PLoS One. 2018; 13:e0201887. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Liu Y, Zhong L, Yuan S, van de Klundert J. Why patients prefer high-level healthcare facilities: A qualitative study using focus groups in rural and urban China. BMJ Glob Health. 2018; 3:e000854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zhang X, Qiu H, Li C, Cai P, Qi F. The positive role of traditional Chinese medicine as an adjunctive therapy for cancer. Biosci Trends. 2021; 15:283-298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang Y, Liu Y, Shi Y, Yu Y, Yang J. User perceptions of virtual hospital apps in China: Systematic search. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2020; 8:e19487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gao H, Du XL, Liao JZ, Xiang L. The pathway of China's integrated delivery system: Based on the analysis of the medical consortium policies. Curr Med Sci. 2022; 42:1164-1171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wei W, Zeng H, Zheng R, Zhang S, An L, Chen R, Wang S, Sun K, Matsuda T, Bray F, He J. Cancer registration in China and its role in cancer prevention and control. Lancet Oncol. 2020; 21:e342-e349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Tang W. The creation of a continuum of care model for cancer patients in Shanghai. Second Military Medical University; Shanghai, China, 2011. (in Chinese). [Google Scholar]

- 26. Chen R, Yang J, Yin S, Chen W, Liu Y. International models of care for cancer survivors: Recent advances and implications in China. Chinese General Medicine. 2022; 25:401-407. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Kalsbeek RJ, van der Pal HJH, Kremer LCM, et al. European PanCareFollowUp Recommendations for surveillance of late effects of childhood, adolescent, and young adult cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2021; 154:316-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sender L, Zabokrtsky KB. Adolescent and young adult patients with cancer: A milieu of unique features. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2015; 12:465-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hill RE, Wakefield CE, Cohn RJ, Fardell JE, Brierley ME, Kothe E, Jacobsen PB, Hetherington K, Mercieca-Bebber R. Survivorship care plans in cancer: A meta-analysis and systematic review of care plan outcomes. Oncologist. 2020; 25:e351-e372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Jacobsen PB, DeRosa AP, Henderson TO, Mayer DK, Moskowitz CS, Paskett ED, Rowland JH. Systematic review of the impact of cancer survivorship care plans on health outcomes and health care delivery. J Clin Oncol. 2018; 36:2088-2100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ma CT, Chou HW, Lam TT, Tung YT, Lai YW, Lee LK, Lee VW, Yeung NC, Leung AW, Bhatia S, Li CK, Cheung YT. Provision of a personalized survivorship care plan and its impact on cancer-related health literacy among childhood cancer survivors in Hong Kong. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2023; 70:e30084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mayer DK, Alfano CM. Personalized risk-stratified cancer follow-up care: Its potential for healthier survivors, happier clinicians, and lower costs. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2019; 111:442-448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Tremblay D, Touati N, Bilodeau K, Prady C, Usher S, Leblanc Y. Risk-stratified pathways for cancer survivorship care: Insights from a deliberative multi-stakeholder consultation. Curr Oncol. 2021; 28:3408-3419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mukumbang FC, De Souza D, Liu H, Uribe G, Moore C, Fotheringham P, Eastwood JG. Unpacking the design, implementation and uptake of community-integrated health care services: A critical realist synthesis. BMJ Glob Health. 2022; 7:e009129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Qian Y, Hou Z, Wang W, Zhang D, Yan F. Integrated care reform in urban China: A qualitative study on design, supporting environment and implementation. Int J Equity Health. 2017; 16:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ramirez AG, Choi BY, Munoz E, Perez A, Gallion KJ, Moreno PI, Penedo FJ. Assessing the effect of patient navigator assistance for psychosocial support services on health-related quality of life in a randomized clinical trial in Latino breast, prostate, and colorectal cancer survivors. Cancer. 2020; 126:1112-1123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Bevilacqua R, Strano S, Di Rosa M, Giammarchi C, Cerna KK, Mueller C, Maranesi E. eHealth literacy: From theory to clinical application for digital health improvement. Results from the ACCESS training experience. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021; 18:11800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Ramanuj P, Ferenchik E, Docherty M, Spaeth-Rublee B, Pincus HA. Evolving models of integrated behavioral health and primary care. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019; 21:4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ye C, Mi M, Zheng S, Yuan Y. Implications of medical education in the United States for the training of oncology specialists in China. General Medicine Clinical and Education. 2022; 20:385-387. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 40. Yu H, Li L, Xu J. Use of MDT and PBL-CBL in the clinical teaching of lymphoma. Basic and Clinical Oncology. 2019; 32:269-271. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 41. Bryant-Lukosius D, Spichiger E, Martin J, Stoll H, Kellerhals SD, Fliedner M, Grossmann F, Henry M, Herrmann L, Koller A, Schwendimann R, Ulrich A, Weibel L, Callens B, De Geest S. Framework for evaluating the impact of advanced practice nursing roles. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2016; 48:201-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Kerr H, Donovan M, McSorley O. Evaluation of the role of the clinical Nurse Specialist in cancer care: an integrative literature review. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl). 2021; 30:e13415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Rao X, Lai J, Wu H, Li Y, Xu X, Browning CJ, Thomas SA. The development of a competency assessment standard for general practitioners in China. Front Public Health. 2020; 8:23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Shi J, Du Q, Gong X, Chi C, Huang J, Yu W, Liu R, Chen C, Luo L, Yu D, Jin H, Yang Y, Chen N, Liu Q, Wang Z. Is training policy for general practitioners in China charting the right path forward? A mixed methods analysis. BMJ Open. 2020; 10:e038173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tam YH, Leung JYY, Ni MY, Ip DKM, Leung GM. Training sufficient and adequate general practitioners for universal health coverage in China. BMJ. 2018; 362:k3128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Li X, Krumholz HM, Yip W, et al. Quality of primary health care in China: Challenges and recommendations. Lancet. 2020; 395:1802-1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Santa Mina D, van Rooijen SJ, Minnella EM, et al. Multiphasic prehabilitation across the cancer continuum: A narrative review and conceptual framework. Front Oncol. 2020; 10:598425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kudre D, Chen Z, Richard A, Cabaset S, Dehler A, Schmid M, Rohrmann S. Multidisciplinary outpatient cancer rehabilitation can improve cancer patients' physical and psychosocial status-A systematic review. Curr Oncol Rep. 2020; 22:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Gong J, Li G, Jiang Y, Ye L. Thinking and practice on the training of rehabilitation therapy talents under the concept of "precision medicine". China Continuing Medical Education. 2022; 14:13-16. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 50. Agbejule OA, Hart NH, Ekberg S, Crichton M, Chan RJ. Self-management support for cancer-related fatigue: A systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022; 129:104206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Boland L, Bennett K, Connolly D. Self-management interventions for cancer survivors: A systematic review. Support Care Cancer. 2018; 26:1585-1595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Dunne S, Coffey L, Sharp L, Desmond D, Gooberman- Hill R, O'Sullivan E, Timmons A, Keogh I, Timon C, Gallagher P. Integrating self-management into daily life following primary treatment: Head and neck cancer survivors' perspectives. J Cancer Surviv. 2019; 13:43-55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Schmidt F, Ribi K, Haslbeck J, Urech C, Holm K, Eicher M. Adapting a peer-led self-management program for breast cancer survivors in Switzerland using a co-creative approach. Patient Educ Couns. 2020; 103:1780-1789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Clarke N, Dunne S, Coffey L, Sharp L, Desmond D, O'Conner J, O'Sullivan E, Timon C, Cullen C, Gallagher P. Health literacy impacts self-management, quality of life and fear of recurrence in head and neck cancer survivors. J Cancer Surviv. 2021; 15:855-865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Coffey L, Mooney O, Dunne S, Sharp L, Timmons A, Desmond D, O'Sullivan E, Timon C, Gooberman-Hill R, Gallagher P. Cancer survivors' perspectives on adjustment-focused self-management interventions: A qualitative meta-synthesis. J Cancer Surviv. 2016; 10:1012-1034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Campanini I, Ligabue MB, Bò MC, Bassi MC, Lusuardi M, Merlo A. Self-managed physical activity in cancer survivors for the management of cancer-related fatigue: A scoping review. PLoS One. 2022; 17:e0279375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhang S, Li J, Hu X. Peer support interventions on quality of life, depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy among patients with cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Patient Educ Couns. 2022; 105:3213-3224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Yoshikawa E, Fujisawa D, Hisamura K, Murakami Y, Okuyama T, Yoshiuchi K. The potential role of peer support interventions in treating depressive symptoms in cancer patients. J Nippon Med Sch. 2022; 89:16-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]