Abstract

Objectives:

This study aimed to evaluate the truthfulness of patients about their pre-appointment COVID-19 screening tests at a dental clinic.

Methods:

A total of 613 patients were recruited for the study from the dental clinic at the Faculty of Dentistry, Najran University, Saudi Arabia. The data collection was done in three parts from the patients who visited the hospital to receive dental treatment. The first part included the socio-demographic characteristics of the patients and the COVID-19 swab tests performed within the past 14 days. The second part was the clinical examination, and the third part was a confirmation of the swab test taken by the patient by checking the Hesen website using the patient ID. After data collection, statistical analysis was carried out using SPSS 26.0. Descriptive analysis was done and expressed as mean, standard deviation, frequency, and percentage (%). A cross-tabulation, also described as a contingency table, was used to identify trends and patterns across data and explain the correlation between different variables.

Results:

It was seen from the status of the swab test within 14 days of the patient's arrival at the hospital for the dental treatment that 18 (2.9%) patients lied about the pre-treatment swab test within 14 days, and 595 (97.1%) were truthful. The observed and expected counts showed across genders and diagnosis a statistically significant difference (p < 0.001), and there was no significant difference seen across different age groups (p = 0.064) of the patients.

Conclusions:

Dental healthcare workers are worried and assume a high risk of COVID-19 infection as the patients are not truthful about the pre-treatment COVID-19 swab test. Routine rapid tests on patients and the healthcare staff are a feasible option for lowering overall risks.

Keywords: COVID-19, dental clinic, diagnosis, risk, exposure, swab test

Introduction

The primary transmission route of coronavirus (COVID-19) virus disease in humans occurs mainly through the respiratory droplets of a person infected with the virus. 1 The spread of this contagious virus also occurs via the aerosols and the droplets exhaled by the infected patients. 2 The source of the droplets, typically associated with saliva, may be oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal. The bigger droplets can lead to viral transmission to nearby persons, and, on the other hand, transmission in long-distance is possible with smaller droplets contaminated with viral particles suspended in the air. 3 In dental clinics, the primary cause of COVID-19 spread is an aerosol generation, crown preparations, endodontic procedures, and even a tiny carious lesion also requires the use of Air-rotor handpieces, coolants, and saliva from patients can transmit infections between dentists and patients. 4 A dental hygienist, dental practitioner, endodontist, or oral surgeon is more likely to be infected by asymptomatic patients. 4 Contract monitoring and tracing of symptomatic patients have reported cases of asymptomatic transmission confirmed by the WHO and the reports from ICMR 5

It is essential to diagnose and screen COVID-19 before the dentist proceeds with an aerosol-generating procedure such as RCT and crown preparations, as failure can end up infecting the dentists or assistants who could become a source of infection for their patient community. 6 The SARS-CoV-2 disease may be symptom-free (without symptoms), mild or moderate, severe (causing pneumonia, increased respiratory rate, and the oxygen demand for breathlessness), or critical (needing intensive care due to acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) or severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) shock or other organ dysfunction). Individuals with severe and critical COVID-19 pneumonia need different treatment methods that make it essential to differentiate between mild or moderate COVID-19 disease and severe COVID-19 pneumonia. 7 Clinical symptoms associated with COVID-19 may differ from case to case. However, the most common symptoms are continuous dry cough, fever and fatigue or myalgia, and irregular chest computed tomography scan results, such as two-sided and marginal ground-glass and associated pulmonary opacities, have been reported in more severe cases. 8

It is recommended that all patients and workers conduct a routine screening procedure to ensure that all symptomatic and newly exposed individuals remain at home to protect both patients and dental team members. 9 The patients should be truthful regarding COVID testing and vaccination to overcome ethical and economic concerns. 10 Screening of asymptomatic carriers of COVID-19 is very troublesome but possible due to limitations of data, medicines, and PPE shortages worldwide. The possible way to prevent silent positive patients is to ensure compulsory testing of each patient before treating them. 6

Depending on the epidemic situation, dental practitioners need to take some essential measures. Every dental practitioner is responsible for fully understanding the features of COVID-19 and strictly implementing prevention strategies and taking the most suitable safety precautions or instruments to avoid the infection risk while dental treatment. 11 Dental staff must strictly adhere to the concept of one person in one room and clean the room after each procedure to prevent any potential contamination caused by the patient. 12 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the American Dental Association (ADA), the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, and others have established different treatment protocols for patients with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 who need to obtain critical or emergency dental care to avoid the transmission of infection. The authenticity of each patient regarding the COVID-19 screening test should be verified thoroughly. The aim of our study was to evaluate the truthfulness of patients about their pre-appointment COVID-19 screening tests as a significant difference between records and screening data would mean that there is a high risk for dental personnel to get infected from asymptomatic patients.

Methodology

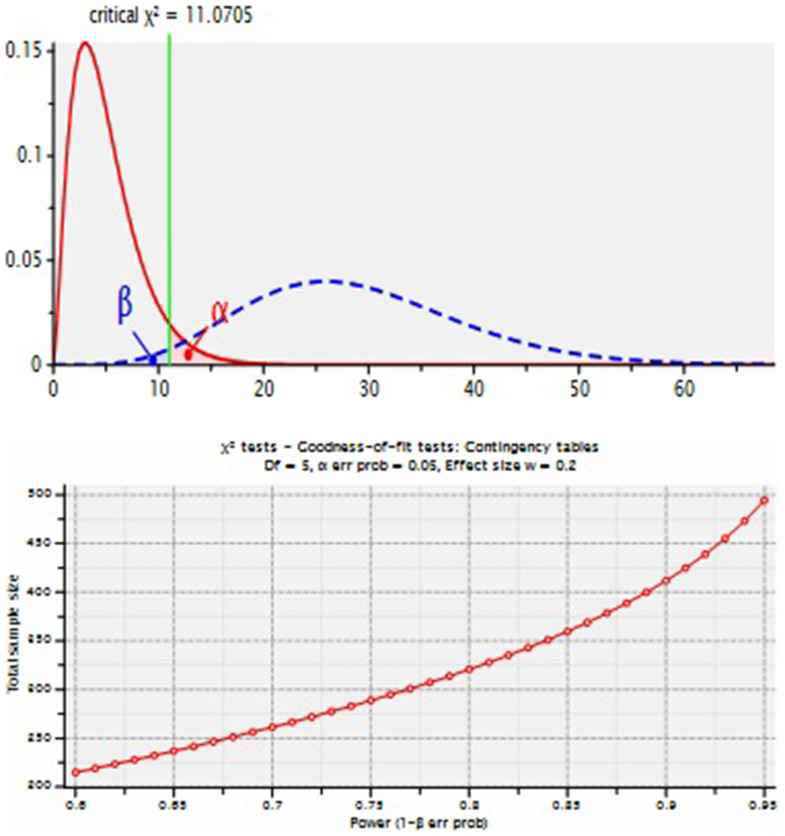

This study was conducted amongst the patients who attended the dental clinic at the Faculty of Dentistry, Najran University, for dental treatment. With prior approval from the hospital and the ethics committee from the Faculty of Dentistry, Najran University, with number 2021/03/0089, a total sample n = 613 was recruited in the study. The sample size calculation was done using G Power 3.1.9.5 software for sample size calculations, using χ2 test—Goodness-of-fit test: Contingency tables, the total sample size obtained was 596 (Figure 1). A convenience sampling method was utilized for the inclusion of participants. This was a descriptive study to evaluate the truthfulness of patients about their pre-appointment COVID-19 screening test, and it was also aimed at providing valuable insight into the risk of COVID-19 transmission from the patient to the practicing dentist. The patients were informed about the study, and consent was obtained. The data collection was done in three parts. All patients who visited the hospital to receive dental treatment and were willing to provide information related to the study were included. Any patients who were not willing to provide socio-demographic information were excluded from the study.

Figure 1.

Plot for sample size calculation.

In the first part, questions were asked related to socio-demographic characteristics (age and gender) of the patients and whether the COVID-19 swab test was done or not within the past 14 days. The second part as clinical examination of the dental patients for the diagnosis and the third part as a confirmation of the swab test taken by the patient by checking the Hesen website (electronic health records in the government system) using the patient ID with permission obtained from the medical record department to access the patients’ record. The dentist did the interview and performed the clinical examination. A non-clinical staff member took the COVID-19 swab test information from the electronic health records at the hospital. The information regarding the post-treatment swab test status from the health ministry was kept blind to the patient.

Statistical analysis

All the data was recorded and analyzed using Statistical Packages for the social sciences (IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA software version 26.0). Descriptive analysis was done and expressed as mean, standard deviation (SD), frequency, and percentage (%). A cross-tabulation, also described as a contingency table, was used to identify trends and patterns across data and explain the correlation between different variables. A dichotomous variable in SPSS was created for the swab test within 14 days, wherein yes was given a value of 1 and a value of 2. For the other variables, the participants in the study were divided into three age-based categories, 17–30 years, 31–50 years, and 51 years above, with male and female gender groups. Further, they are categorized according to the diagnosis of the patients. All the variables were cross-tabulated to evaluate the patients’ truthfulness about their pre-appointment COVID-19 screening test and the relative risk of COVID-19 transmission.

Results

A total of 613 patients participated in this study who attended the dental clinic at the Faculty of Dentistry, Najran University, for dental treatment. Table 1 demonstrates the distribution of patients with age group 17–30 (32.3%), 31–50 (47.8%), and 51+ (19.9%), of which 313 were males and 300 were females. The majority of the patients were diagnosed with reversible pulpitis (49.1%), followed by the patients who came for the tooth extraction (21.4%), broken tooth/filling (9.1%), denture and ortho case (7.2%), irreversible pulpitis (4.4%), and gingivitis (1.6%), respectively. The status of the swab test within 14 days of the patient arrived at the hospital for the dental treatment was 18 (2.9%) lied about the pre-treatment swab test, and 595 (97.1%) were truthful.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic profile of the patients (n = 613).

| Variables | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Age group | |

| 17–30 years | 198 (32.3) |

| 31–50 years | 293 (47.8) |

| 51 years and above | 122 (19.9) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 313 (51.1) |

| Female | 300 (48.9) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Reversible pulpitis | 301 (49.1) |

| Irreversible pulpitis | 27 (4.4) |

| Broken tooth/filling | 56 (9.1) |

| Denture case | 44 (7.2) |

| Otho case | 44 (7.2) |

| Gingivitis | 10 (1.6) |

| Tooth extraction | 131 (21.4) |

| Swab test within 14 days | |

| Yes | 18 (2.9) |

| No | 595 (97.1) |

Table 2 demonstrates the descriptive statistics of the patients that came to the hospital for dental treatment. The mean age of the participants was 38.69 ± 13.57, gender 1.48 ± 0.50, diagnosis 3.46 ± 2.88, and swab test 1.97 ± 0.16, respectively.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics.

| Variables | Minimum | Maximum | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 17 | 82 | 38.69 ± 13.57 |

| Gender | 1 | 2 | 1.48 ± 0.50 |

| Diagnosis | 1 | 8 | 3.46 ± 2.88 |

| Swab test within 14 days | 1 | 2 | 1.97 ± 0.16 |

Table 3 demonstrates the distribution of patients who came to the hospital for the dental treatment with swabs done within 14 days across age, gender, and diagnosis. The observed and expected counts were described in the table. The gender and diagnosis of the patients showed a statistically significant difference with values (χ2 = 10.620, df = 1, p < 0.05) and (χ2 = 357.27, df = 6, p < 0.05), respectively. There was no significant difference seen with the age group (χ2 = 5.508, df = 2, p = 0.064) of the patients.

Table 3.

Distribution of patients with swab done within 14 days across age, gender, and diagnosis.

| Variable | Swab within 14 days | χ 2 | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes (OC, EC) | No (OC, EC) | |||

| Age | ||||

| 17–30 | 9, 5.2 | 189, 192.2 | ||

| 31–50 | 9, 8.6 | 284, 284.4 | 5.508 | 0.064 |

| 51+ | 0, 3.6 | 122, 118.4 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 02, 8.8 | 298, 291.2 | 10.62 | 0.001 a |

| Male | 16, 9.2 | 297, 303.8 | ||

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Reversible pulpitis | 0, 8.8 | 301, 292.2 | ||

| Irreversible pulpitis | 17, 0.8 | 10, 26.2 | ||

| Broken tooth/filling | 0, 1.6 | 56, 54.4 | 357.27 | 0.001 a |

| Denture case | 0, 1.3 | 44, 42.7 | ||

| Ortho case | 0, 1.3 | 44, 42.7 | ||

| Gingivitis | 0, 0.3 | 10, 9.7 | ||

| Tooth extraction | 1, 3.8 | 130, 127.2 | ||

Significant value <0.05; Cross-tabulation χ2 test; OC: observed count; EC: expected count.

Discussion

In dental practices, the risk is perceived to be greater than in other health care contexts, mainly because there is close and sustained interaction between the dental practitioner and the patient. Most dental operations create aerosols containing a patient's saliva, blood, other secretions, or tissue particles. 13 The COVID-19 incubation period is between 7 and 24 days, which means it would take a minimum of a week for the symptoms to appear, but the carrier may infect the clusters. 14 The COVID-19 can occur in pre-symptomatic or asymptomatic patients. According to WHO guidelines, a COVID-19 infected individual can be identified using a combination of epidemiologic evidence, for example, a history of travel in 14 days before the onset of symptoms in an infected area, laboratory testing, for example, RT-PCR tests, clinical symptoms, and CT imaging results. 15 It is worth remembering that a single negative RT-PCR test from a suspected patient does not rule out infection. Patients with an epidemiologic past, COVID-19-related conditions, and positive CT imaging findings should be monitored closely in the clinic. 16 Medical history or body temperature provides no guarantee of recognizing contaminated people in these experiences. At this point, accurate and legitimate testing prior to dental treatment is not a choice because it is not possible to rule out false-negative outcomes.

Vaccinations are just started, and the immunity status after an infection is under trial and analysis. The principle of standard precautions is the only practical and secure solution. This means that, for the time being, all patients must be considered potentially infectious for the transmission of airborne diseases and should be handled with the same degree of caution. 17 All patients who participated in our study declared that they did not undergo the swab test within 14 days of their arrival at the dental clinic. After the confirmation by checking the Hesen website (electronic health records in the government system), 18 (2.9%) dental patients lied about their pre-treatment COVID-19 swab test done within 14 days. The results of swab tests of these 18 dental patients were fortunately found to be negative. It is entirely feasible to observe a general discontent among dental practitioners in such unprecedented conditions. Indeed, since very little is understood about the treatment of COVID-19 diseases, contamination, and potential recontamination, they are worried about the health of patients and their safety.

There are only a handful of studies available to date in the literature on the effect of COVID-19 on dental treatment. 18 It is easier for healthcare workers and patients to develop the infection if such asymptomatic cases are hard to detect. 6 Serological testing can aid in the diagnosis of clinically suspected patients who have negative swab test results and the detection of infection in asymptomatic patients. 19 Rapid tests for detecting SARS-CoV-2 IgG IgM antibodies have been developed using the lateral flow immune assay techniques. These tests can detect IgM and IgG antibodies to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in human blood within 15 min, enabling them to identify patients at various stages of infection. 20 Testing patients for SARS-CoV-2 before granting them access to dental offices was not considered. Even if they pass the pre-assessment triage, patients who are expected to attend the dental clinics must be possible virus carriers. They can be tested 24 h before treatment with the gold standard swab RT-PCR test and SARS-CoV-2 specific IgM/IgG detection. This test could help recognize asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 positive patients. If the swab test is negative, the antibody test will help identify the patient into one of three categories: good, healed, or ill. A patient with a negative swab and IgM and IgG levels can undergo regular dental treatments. 21

Our study results revealed the mean age of patients 38.69 ± 13.57, whereas 47.8% of the participants were in the 31–50 years age group. There was no significant difference seen between the patients with swab tests done within 14 days and the age of the patients. Previous studies revealed that patients with high age are more prone to testing positive for the COVID-19 swab test, and the age influence did not diminish as the time lapsed.22,23 This research also identified a significant difference between the gender of patients and swab test done within 14 days with the p-value < 0.05. Similar findings were reported among the studies conducted in China.22,24 However, previous studies have shown that both men and women are susceptible to the SARS-CoV-2 virus.25,26 There was a significant difference between the diagnosis of patients and the swab test done within 14 days. Of all the patients who lied about the pre-treatment swab test, 17 were suffering from irreversible pulpitis, and 1 patient came for the tooth extraction.

The risk of COVID-19 transmissions among the healthcare workers increases if the patients do not provide accurate information regarding the screening of COVID-19 before attending the dental clinic for treatment. Testing the patient chairside using saliva or nasal swabs will disclose vital diagnostic information. COVID-19 is found in saliva, and salivary load has a good association with COVID-19 in nasal swabs.27,28 Saliva appears to be a practical noninvasive tool for assessing infectivity that dental healthcare staff could easily include in circumstances where large numbers of people need screening. The ADA supports COVID-19 research by dentists with reliable and valid screening tests. 29

In dental practices and dental schools, we must be continuously aware of infectious hazards that may pose a danger to the existing infection control protocol. Successful methods to prevent, monitor, and avoid the spread of COVID-19 should be developed to improve awareness of viral features, clinical scope, care, and epidemiologic characteristics. We are in the middle of COVID-19 has affected the infection prevention and control methods that we have introduced. According to the regional epidemic condition, other areas should obey the advice of disease control centers for infection prevention and control. 16 Before any dental procedure, for every dental patient, a COVID-19 examination to screen for an asymptomatic carrier should be made mandatory as the dental healthcare workers are in close contact with patients. It will assist the government and dentists prevent the spread of the disease, even among symptomatic patients. Though it may increase the cost of care, it may reduce the risk of infection.

The patients who need dental care should carry the negative swab test results a day before and the vaccination record before entering the dental clinic. The dental healthcare settings should strictly follow the infection control protocols and guidelines given by the WHO and the local government bodies. 30 In this way, the risk of COVID-19 transmission can be prevented among healthcare workers and the patients in a community. Further research should be done to improve the infection control strategies and prevent the spread of COVID-19 among dental patients and dental practitioners.

Limitations

This study was conducted at a single center and it could be used as a platform to run future studies across different centers or a multi-center study to evaluate significant differences across different regions.

Conclusion

Dental healthcare workers are worried and assume a high risk of COVID-19 infection as the patients are not truthful about the pre-treatment COVID-19 swab tests. Routine rapid tests on patients and the healthcare staff are a feasible option for lowering overall risks.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Anand Marya https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2009-4393

References

- 1.Jin YH, Cai L, Cheng ZS, et al. A rapid advice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infected pneumonia (standard version). Mil Med Res 2020; 7: 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leung NH, et al. Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nat Med 2020; 26: 676–680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xie X, et al. Exhaled droplets due to talking and coughing. J R Soc Interface 2009; 6: S703–S714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Huang C, et al. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China . Lancet 2020; 395: 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report—73. Data as reported by national authorities, 2020.

- 6.Jethi N, et al. Asymptomatic COVID-19 patients and possible screening before an emergency aerosol related endodontic protocols in dental clinic-a review. J Family Med Prim Care 2020; 9: 4552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Struyf T, et al. Signs and symptoms to determine if a patient presenting in primary care or hospital outpatient settings has COVID-19 disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2020; 7: CD013665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barabari P, Moharamzadeh K. Novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and dentistry–a comprehensive review of literature. Dent J 2020; 8: 53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalenderian E, et al. COVID-19 and dentistry: challenges and opportunities for providing safe care. PSNET. 7 August2020.

- 10.Gozum IEA, Carreon AD, Manansala MM. Emphasizing truthfulness in COVID-19 test declarations. J Public Health (Bangkok) 2021; 43: e387–e388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, et al. Precautions in dentistry against the outbreak of corona virus disease 2019. J Infect Public Health 2020; 13: 1805–1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, et al. Health services provision of 48 public tertiary dental hospitals during the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Clin Oral Investig 2020; 24: 1861–1864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harrel SK, Molinari J. Aerosols and splatter in dentistry: a brief review of the literature and infection control implications. J Am Dent Assoc 2004; 135: 429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yi Y, et al. COVID-19: what has been learned and to be learned about the novel coronavirus disease. Int J Biol Sci 2020; 16: 1753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.WHO. Clinical management of severe acute respiratory infection when novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) infection is suspected: interim guidance. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/clinical-management-of-severe-acute-respiratory-infection-when-novel-coronavirus-(ncov)-infection-is-suspected (2020).

- 16.Meng L, Hua F, Bian Z. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): emerging and future challenges for dental and oral medicine. J Dent Res 2020; 99: 481–487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beltrán-Aguilar E, Benzian H, Niederman R. Rational perspectives on risk and certainty for dentistry during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Infect Control 2021; 49: 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gambarini E, et al. A survey on perceived COVID-19 risk in dentistry and the possible use of rapid tests. J Contemp Dent Pract 2020; 21: 718–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Long Q-X, et al. Antibody responses to SARS-CoV-2 in patients with COVID-19. Nat Med 2020; 26: 845–848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Z, et al. Development and clinical application of a rapid IgM-IgG combined antibody test for SARS-CoV-2 infection diagnosis. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 1518–1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giudice A, Antonelli A, Bennardo F. To test or not to test? An opportunity to restart dentistry sustainably in the ‘COVID-19 era’. Int Endod J 2020; 53: 1020–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu H, et al. Analysis and prediction of COVID-19 patients’ false negative results for SARS-CoV-2 detection with pharyngeal swab specimen: a retrospective study. medRxiv, 2020.

- 23.Wei Y, et al. Analysis of 2019 novel coronavirus infection and clinical characteristics of outpatients: an epidemiological study from a fever clinic in Wuhan, China. J Med Virol 2020; 92: 2758–2767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao AT, et al. Dynamic profile of RT-PCR findings from 301 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. J Clin Virol 2020; 127: 04346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Guan W-J, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1708–1720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wang D, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. Jama 2020; 323: 1061–1069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.To KK-W, et al. Temporal profiles of viral load in posterior oropharyngeal saliva samples and serum antibody responses during infection by SARS-CoV-2: an observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020; 20: 565–574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wyllie AL, et al. Saliva is more sensitive for SARS-CoV-2 detection in COVID-19 patients than nasopharyngeal swabs. MedRxiv, 2020.

- 29.Chaudhary FA, Ahmad B, Ahmad P, Khalid MD, Butt DQ, Khan SQ. Concerns, perceived impact, and preparedness of oral healthcare workers in their working environment during COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Health 2020; 62: e12168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Karobari MI, et al. The state of orthodontic practice after the outbreak of COVID-19 in Southeast Asia: the current scenario and future recommendations. Asia Pac J Public Health 2020; 32: 517–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]