ABSTRACT

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) can be released from gram-positive bacteria and would participate in the delivery of bacterial toxins. Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus, GAS) is one of the most common pathogens of monomicrobial necrotizing fasciitis. Spontaneous inactivating mutation in the CovR/CovS two-component regulatory system is related to the increase of EVs production via an unknown mechanism. This study aimed to investigate whether the CovR/CovS-regulated RopB, the transcriptional regulator of GAS exoproteins, would participate in regulating EVs production. Results showed that the size, morphology, and number of EVs released from the wild-type strain and the ropB mutant were similar, suggesting RopB is not involved in controlling EVs production. Nonetheless, RopB-regulated SpeB protease degrades streptolysin O and bacterial proteins in EVs. Although SpeB has crucial roles in modulating protein composition in EVs, the SpeB-positive EVs failed to trigger HaCaT keratinocytes pyroptosis, suggesting that EVs did not deliver SpeB into keratinocytes or the amount of SpeB in EVs was not sufficient to trigger cell pyroptosis. Finally, we identified that EV-associated enolase was resistant to SpeB degradation, and therefore could be utilized as the internal control protein for verifying SLO degradation. This study revealed that RopB would participate in modulating protein composition in EVs via SpeB-dependent protein degradation and suggested that enolase is a potential internal marker for studying GAS EVs.

KEYWORDS: Group A Streptococcus, extracellular vesicles, RopB, SpeB, SLO, enolase

Introduction

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) are lipid-bilayer spheres in size ranging from 20 nm to 500 nm in diameter and can be produced by eukaryotic and prokaryotic cells [1]. Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli, have been shown to produce EVs (known as outer membrane vesicles, OMVs) by a pinching-off process from the periplasmic space [2,3]. Gram-positive bacteria have a thick cell wall that is disadvantageously for EVs formation; however, several important gram-positive pathogens, including Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Staphylococcus aureus, and Streptococcus pyogenes, are capable of releasing EVs [4–6].

Streptococcus pyogenes (group A Streptococcus, GAS) is the human pathogen that causes diseases including pharyngitis, tonsillitis, pyoderma, scarlet fever, necrotizing fasciitis, and toxic shock syndrome [7]. Resch et al [8] showed that GAS produces EVs in diameter ranging between 10–272 nm. The virulence-associated proteins, including M protein, C5a peptidase (ScpA), and streptolysin O (SLO) are identified in EVs [8]. Noticeably, the production of EVs is negatively regulated by the two-component regulatory CovR/CovS system [8]. The inactivating mutations in covR and covS are frequently identified in isolates from patients with severe manifestations [9,10]; therefore, the increased production of EVs in the covR or covS mutants might have roles in GAS infection. Nonetheless, the mechanism of how CovR/CovS controls EV production and the role of EVs in GAS pathogenesis are largely unknown.

CovR/CovS not only regulates the expression of virulence factors but also has crucial roles in controlling the expression of transcriptional regulators [11]. The studies showed that CovR/CovS regulates RopB and RopB-controlled SpeB cysteine protease expression by modulating both the transcriptional expression and regulatory activity of RopB [12,13]. RopB is the quorum-sensing regulator that binds to the SpeB-inducing peptide (SIP) to activate speB expression under acidic conditions [14,15]. SpeB is the most abundant secreted protein in GAS culture supernatant and could be released from bacteria with EVs [16]. Recent studies showed that SpeB can cleave gasdermin A in the keratinocytes to trigger caspase-independent cell pyroptosis [17,18]. SpeB itself cannot penetrate the host cell membrane and fails to trigger pyroptosis [17]. EVs have been shown to have roles in delivering bacterial toxins into host cells [19]. Whether EV-associated SpeB could trigger cell pyroptosis remained to be elucidated.

RopB has important roles in regulating the expression of SpeB and exoproteins in GAS [20]. In this study, whether RopB is involved in controlling EVs production was investigated. Although the results did not support that RopB could regulate EV production, we found that SpeB protease had a critical role in degrading proteins in EVs. Further, enolase (also known as streptococcal surface enolase), which was resistant to SpeB degradation, could be utilized as the internal control protein for GAS EV analyses. SpeB and enolase are virulence-associated proteins [21–25]. This study reveals that SpeB and enolase are EV-associated proteins and might contribute to GAS pathogenesis during infection.

Results

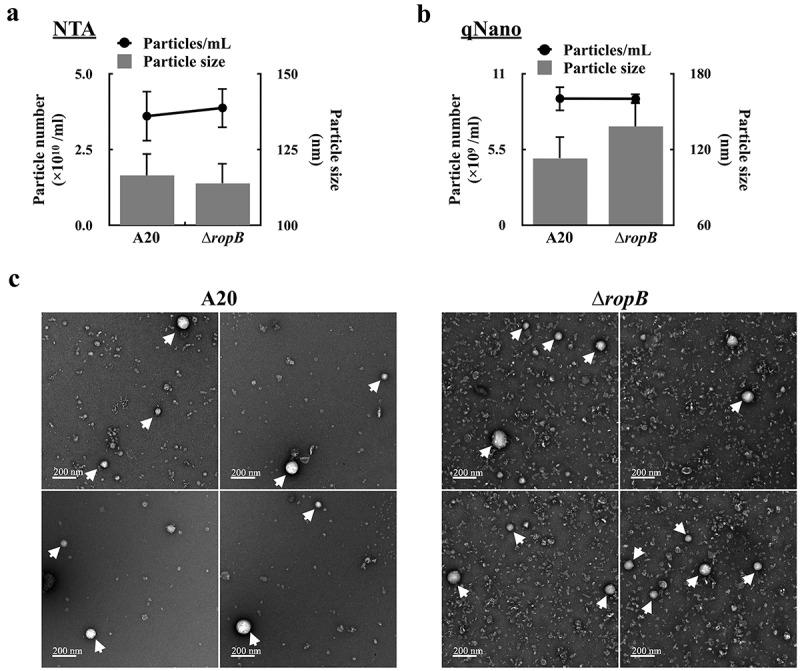

RopB is not involved in controlling EV production

The production of extracellular vesicles (EVs) in GAS is repressed by CovR/CovS through an undefined mechanism [8]. RopB is an important regulator of exoproteins expression and is regulated by CovR/CovS [13,20,26,27]; therefore, whether RopB is involved in controlling EVs production was evaluated. The EVs released from the wild-type A20 strain and its ropB isogenic mutant after 16 h of incubation were collected by ultracentrifugation and the number of released EVs was analysed by Nanoparticle tracking (NTA) and tunable resistive pulse sensing (qNano) systems. The diameter of EV determined by NTA and qNano ranged from 113–138 nm; no significant difference in size was found between EVs from A20 and the ropB mutant (Figure 1a,b, and supplementary Fig. S1). Also, the number of released EVs from A20 and the ropB mutant was similar (3.61–3.99 × 1010 /ml by NTA and 9.19–9.17 × 109/mL by qNano). Under the electron microscope observation, the size and morphology of EVs released from A20 and the ropB mutant were similar. These results suggested that RopB is not involved in controlling EV production.

Figure 1.

RopB is not involved in regulating the production of extracellular vesicles. The EVs from the overnight culture wild-type A20 strain and the ropB mutant (∆ropB) were collected by ultracentrifugation, and the particle size and number were analysed by (a) the nanoparticle tracking system (NTA) and (b) the tunable resistive pulse sensing system (qNano). (c) The morphology of EVs from A20 and ropB mutant under the scanning electron microscope observation (indicated by arrows).

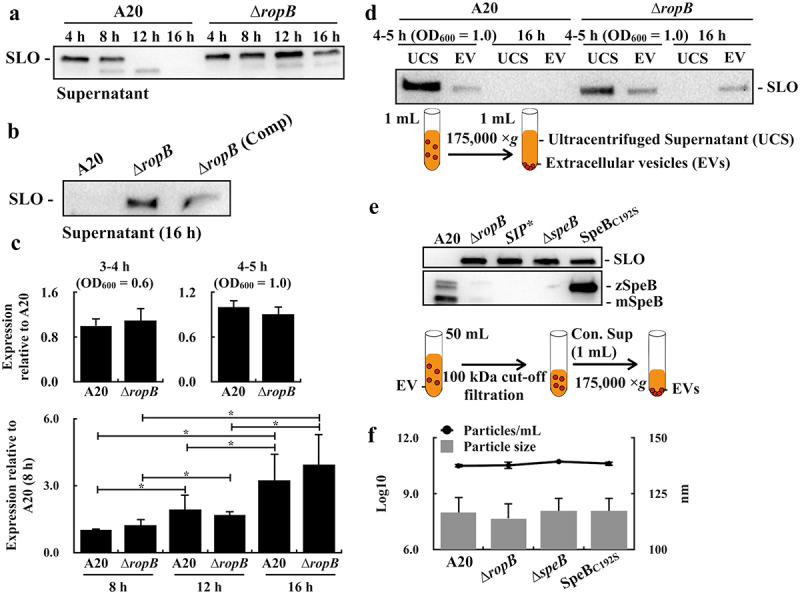

SLO in EVs is degraded by SpeB cysteine protease

Streptolysin O (SLO) is the pore-forming toxin and has been identified in EVs [8,28]. We found that SLO can only be detected in the culture supernatants from the ropB mutant but not that from the wild-type A20 strain after 12–16 h of incubation (Figure 2a). To compare to the ropB mutant, the amount of SLO in the culture supernatants from the ropB trans-complementary strain [∆ropB (Comp), Figure 2b] was decreased, supporting that the presence of RopB would be related to the decrease of SLO in bacterial culture supernatants. The transcriptional level of slo was similar in A20 and the ropB mutant after 8–16 h incubation (Figure 2c), indicating that the decrease of SLO in A20 culture supernatants was not caused by the transcriptional inhibition of slo. To elucidate the role of RopB in regulating protein secretion with EVs, the EVs released from the wild-type A20 strain and its ropB mutant were collected by ultracentrifugation, and the EVs and the EV-depleted ultracentrifuged supernatants (UCSs) were subjected for western blot hybridization. SLO was detected in both EVs and UCSs from the late-exponential-phase A20 and ropB mutant (O.D. 600 = 1.0) (Figure 2d). Nonetheless, after 16 h of incubation, SLO can only be detected in EVs from the ropB mutant but not in EVs from A20 (Figure 2d). SLO has been shown to be degraded by the RopB-regulated SpeB cysteine protease [29]. To verify whether the loss of SpeB in the ropB mutant was related to the presence of SLO in its EVs, the EVs from the speB mutant and the SpeB cysteine protease-inactivated mutant (SpeBC192S) were collected and analysed by western blot. To ensure SLO in EVs can be detected by western blot hybridization, the bacterial-free culture supernatant was concentrated by using a 100 kDa filter before the ultracentrifugation (Figure 2e) [19]. Similar to the ropB mutant, SLO can be detected in the EVs released from the speB mutant and SpeBC192S mutant (Figure 2e). SpeB is secreted as the 42 kDa zymogen form and autocatalyzed into the 28 kDa mature protease [30,31]; therefore, in the SpeBC192S mutant, only the 42 kDa zymogen form SpeB can be detected (Figure 2e). It has been known that RopB binds to the quorum-sensing peptide SIP to activate the speB expression [14]. Our results showed that the expression of SpeB was inhibited in the SIP-inactivated mutant (SIP*) and SLO can be detected in EVs from this mutant (Figure 2e). To be noted, the growth activity of the wild-type strain, the ropB mutant, speB mutants, and SIP* mutant was similar (data not shown). Further, the size and the number of released EVs from the speB mutant and SpeBC192S mutant were similar (Figure 2f), suggesting that the inactivation of SpeB secretion would not affect EV production. These results suggested that SLO could be degraded by SpeB in EVs.

Figure 2.

The SpeB cysteine protease degrades streptolysin O (SLO) in extracellular vesicles. (a) and (b) SLO in bacterial culture supernatants from the wild-type A20 strain, its ropB mutant (∆ropB), and the ropB complementary strain [∆ropB (Comp)]. (c) The expression of slo in the wild-type A20 strain and its ropB mutant. RNAs were extracted from A20 and ropB mutant after 5–16 h of incubation. The expression of slo was normalized to that of gyrA. *, P < 0.05. (d) SLO in ultracentrifuged culture supernatants (UCSs) and extracellular vesicles (EVs) from A20 and the ropB mutant. The lower panel shows the protocol for separating UCSs and EVs. (e) SLO and SpeB in EVs from A20, the ropB mutant, the speB isogenic mutant (∆speB), the SpeB protease-inactivated (SpeBC192S) mutant, and the SpeB-inducing peptide-inactivated (SIP*) mutant after 16 h of incubation. The lower panel shows the protocol for isolating EVs. Thirty-µL of supernatants and EVs were utilized for western blot hybridization. zSpeB, the zymogen form SpeB (42 kDa); mSpeB, the mature form SpeB (28 kDa). (f) The size and the number of released EVs from A20, the ropB mutant, the speB mutant, and the SpeBC192S mutant. The EVs were analysed by the nanoparticle tracking system.

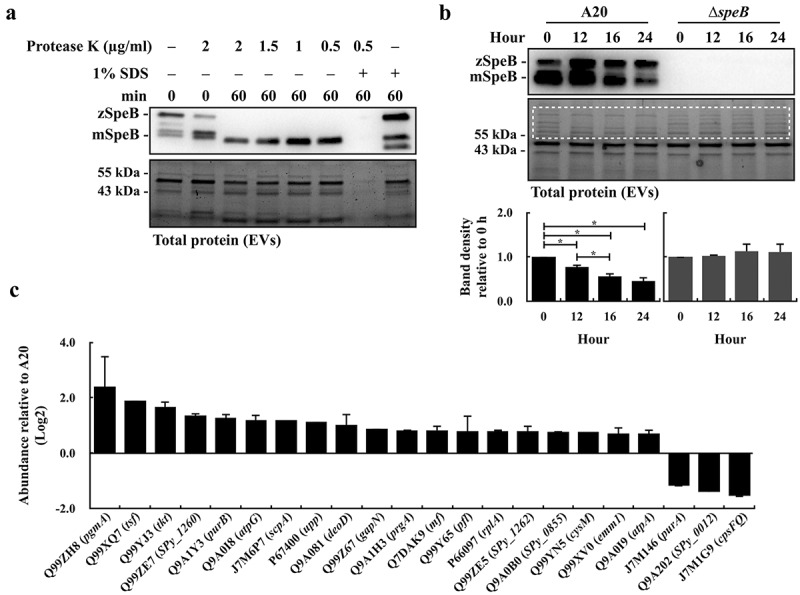

SpeB degrades GAS proteins in EVs

SpeB has been identified in EVs by proteomic analysis [16]. This study suggested that SLO in EVs can be degraded by SpeB; therefore, whether SpeB is located in EVs was further verified by the protease K protection assay [32]. The EVs were isolated from the wild-type A20 strain in the stationary phase (8 h of incubation) and incubated at 37ºC with or without protease K and 1% SDS treatments. In the absence of 1% SDS, the mature form SpeB (28 kDa) was resistant to the protease K (2 µg/mL) degradation (Figure 3a). When the EVs’ membrane was disrupted by 1% SDS, SpeB and proteins in EVs were completely degraded by 0.5 µg/mL protease K after 60 min of treatments (Figure 3a). These results supported that SpeB is in EVs. Further, to demonstrate SpeB could degrade proteins in EVs, the EVs were isolated from A20 and its speB mutant in the stationary phase, and the EV-associated proteins were detected by 10% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis after incubating EVs at 37ºC for 12–24 h. The amount of zymogen and mature forms of SpeB was decreased after 12–24 h of incubation (Figure 3b). We found that the band density of proteins larger than 55 kDa was decreased significantly in EVs from A20 but showed no difference in EVs from the speB mutant after incubation (Figure 3b), suggesting that SpeB has roles on degrading proteins in EVs.

Figure 3.

The SpeB protease degrades bacterial proteins in extracellular vesicles. (a) Protease K protection assay for SpeB in EVs. EVs from the stationary phase A20 (after 8 h of incubation) were collected by ultracentrifugation and incubated with protease K in the presence with or without 1% SDS. SpeB was detected by western blot (the upper panel) and the lower panel shows the total protein of EVs. (b) SpeB and total protein profiles in A20’s and the speB mutant’s (∆speB) EVs after 0–24 h incubation at 37ºC. SpeB in EVs was detected by western blot (the upper panel) and the total protein profile in EVs (the middle panel) was visualized. The band density in the dash-line indicated region (the middle panel) was calculated, and the band density relative to 0 h was shown in the lower panels. zSpeB, the zymogen form SpeB (42 kDa); mSpeB, the mature form SpeB (28 kDa). *, P < 0.05. (c) The protein abundance in EVs from the speB mutant relative to that in EVs from A20. The relative protein abundance was calculated as [PSMs(∆speB) of target protein/total PSMs(∆speB)]/[PSMs of target protein(A20)/total PSMs(A20)]. The proteins with a relative abundance greater than 1.5-fold were shown. The accession number (UniProt) and the coding gene of target proteins were indicated on the x-axis. Results from the two-independent experiments were included for analysis.

To further verify the role of SpeB in degrading proteins in EVs, the EVs from the overnight culture wild-type A20 strain and its speB mutant were collected and the proteins in EVs were identified by the protein ID approach. The abundance of identified proteins over 0.1% [Peptide Spectrum Matches (PSMs) of the identified protein/total PSMs] in each sample was included for analysis. SpeB degrades C5a peptidase (J7M6P7) and M protein (Q99XV0) [29,33]. In line with the previous findings, the protein ID analysis showed that the abundance of C5a peptidase and M protein in EVs from the speB mutant was increased 1.65–2.29-fold compared to that from the A20 strain. Furthermore, a hundred and one proteins were identified in EVs from A20 and the speB mutant (Supplementary Table S1). Among these proteins, nineteen proteins showed an increase of abundance (>1.5-fold), and only three proteins showed a decrease of abundance (<0.5-fold), in EVs from the speB mutant compared to that from the wild-type A20 strain (Figure 3c). These results suggested that SpeB had roles on modulating protein composition in EVs.

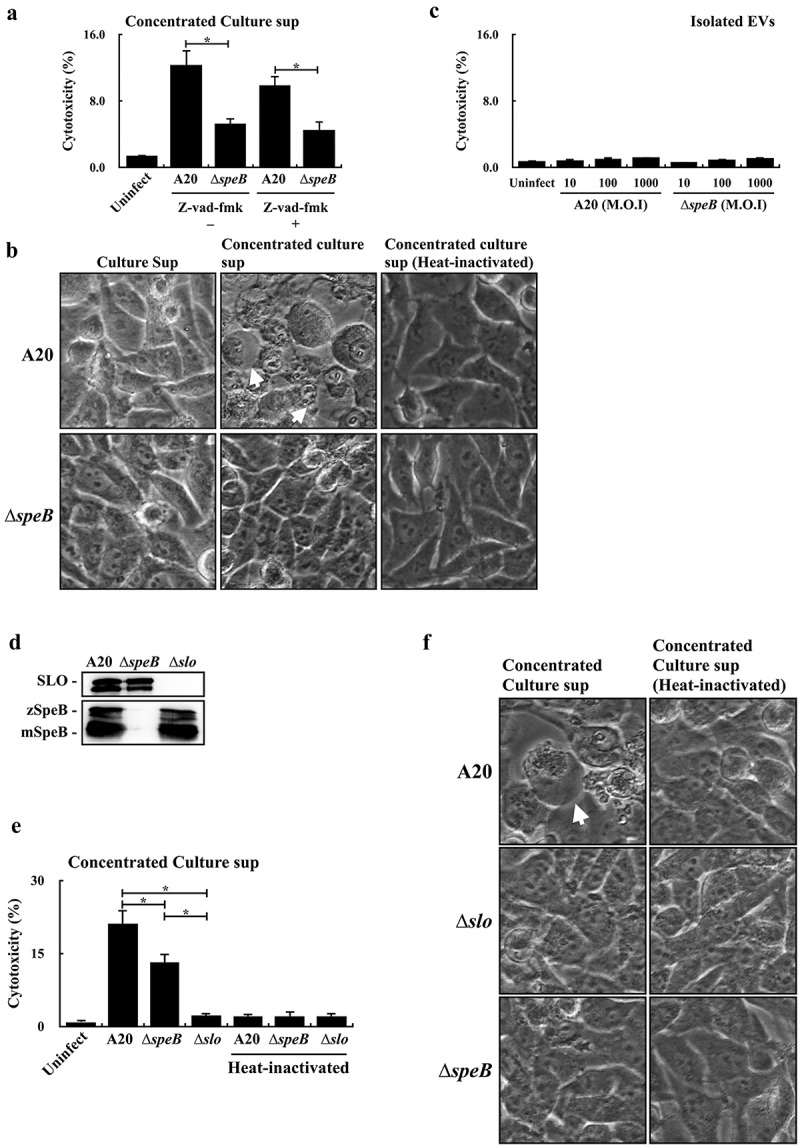

SpeB in EVs fails to trigger pyroptosis in keratinocytes

SpeB could degrade gasdermin A (GSDMA) to trigger the GSDMA-dependent and caspase-independent pyroptosis in keratinocytes [17,18]. LaRock et al [17] suggested that the extracellular SpeB cannot translocate across the plasma membrane to degrade GSDMA; however, the SpeB protein packaged in liposomes can trigger cell pyroptosis effectively. EVs are lipid-bilayer spheres and could enter the cell through absorption (in the cytoplasm) or endocytosis (in the endosome). Both absorption and endocytosis could facilitate SpeB to penetrate the cell membrane. Therefore, whether EV-associated SpeB could trigger cell death was evaluated. First, we found that the concentrated bacterial culture supernatant from the wild-type A20 strain was more toxic to HaCaT keratinocytes than that from the speB mutant in the presence with or without the pan-caspase inhibitor Z-vad-fmk (Figure 4a). The bubbling morphology, the typical characteristics of the pyroptotic cell, was identified in HaCaT cells treated by the concentrated A20 supernatant but not by the concentrated speB mutant supernatant (Figure 4b), suggesting that EV-associated SpeB in the concentrated supernatant could participate in triggering HaCaT keratinocytes pyroptosis. Nonetheless, the EVs from the wild-type A20 strain and its speB mutant cannot trigger cell death even if the multiplicity of infection (M.O.I.) was up to 1000 (Figure 4c).

Figure 4.

Extracellular vesicle-associated SpeB fails to trigger HaCaT keratinocyte pyroptosis. (a) The cytotoxicity of the concentrated supernatant (by 10 kDa centrifugal filter) from A20 and the speB mutant (∆speB) to HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were incubated with the 2-fold concentrated supernatants at 37ºC for 4 h. Z-vad-fmk (20 µM), the pan-caspase inhibitor. The morphology of concentrated supernatant-treated cells was shown in (b). The bubbling morphology, the typical characteristic of pyroptotic cells, is indicated by arrows. (c) Cytotoxicity of EVs from A20 and the speB mutant to HaCaT cells. HaCaT cells were treated by EVs with the multiplicity of infection (M.O.I.) 10–1000 at 37ºC for 4 h. (d) The expression of SpeB and SLO in A20, the speB mutant, and the slo mutant (∆slo). Bacterial strains were cultured to the stationary phase and the bacterial culture supernatant was analysed by western blot hybridization. zSpeB, the zymogen form SpeB (42 kDa); mSpeB, the mature form SpeB (28 kDa). (e) The cytotoxicity of the concentrated supernatant (by 10 kDa centrifugal filter) from A20, the speB mutant, and the slo mutant to HaCaT cells. The morphology of concentrated supernatant-treated cells was shown in (f) and the bubbling cell morphology was indicated by the arrow. Cytotoxicity was determined by the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) assay. *, P < 0.05.

Streptolysin O (SLO) is the pore-forming toxin produced by both A20 and its speB mutant. The expression level of SpeB in the slo mutant was similar in A20 and the speB mutant (Figure 4d). Nonetheless, the cytotoxicity of the concentrated culture supernatant from the slo mutant was decreased significantly compared to cells treated by the concentrated supernatants from A20 and its speB mutant (Figure 4e,f). These results suggested that SLO was required to trigger HaCaT cell death in the concentrated bacterial supernatants. Also, these results suggested that EVs, from the wild-type strain and speB mutant, were not sufficient to trigger pyroptosis in HaCaT cells.

Enolase in EVs is resistant to SpeB degradation

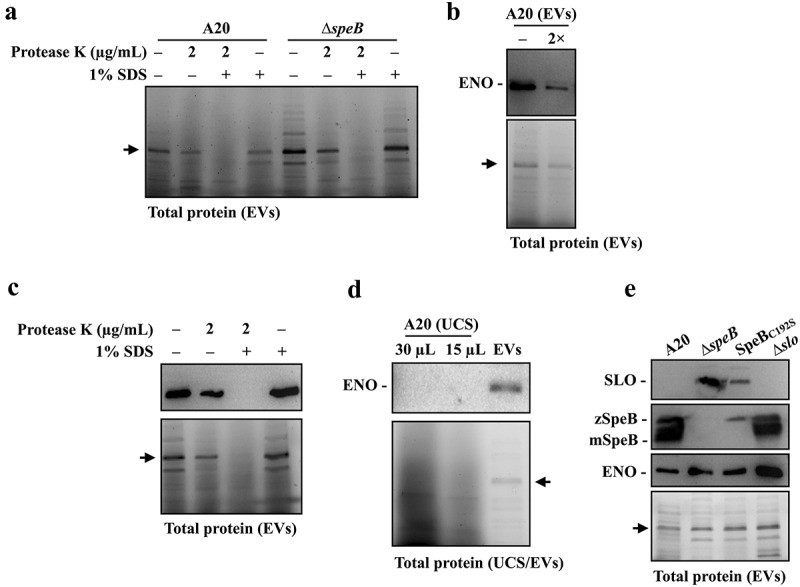

We found an unknown protein (43–55 kDa) was consistently being detected in EVs from the wild-type strain and speB mutant (Figure 3b). To verify this unknown protein was in EVs, the EVs from the wild-type A20 strain and its speB mutant were collected and treated with protease K in the presence with or without 1% SDS. This unknown protein was only completely degraded by protease K when 1% SDS was presented (Figure 5a), indicating that this protein was the EV-associated protein. The protein ID analysis suggested that this unknown protein is enolase (45 kDa). Enolase, also known as the streptococcal surface enolase [34], was detected in EVs from both A20 and the speB mutant by the protein ID analysis (Table S1), further suggesting that enolase could be the EV-associated protein that resistant to SpeB degradation. Fontan et al [35] showed that GAS enolase could cross-react with the human anti-enolase antibody. We found that the commercially available anti-human enolase antibody can detect GAS enolase specifically (Figure 5b). The signals detected by the human anti-enolase antibody were corresponding to the enolase signals revealed by the SDS-PAGE electrophoresis (Figure 5b,c), supporting that this protein could be GAS enolase. Further, in the EV-depleted ultracentrifuged culture supernatants, GAS enolase cannot be detected (Figure 5d), indicating that GAS enolase was the EV-associated protein.

Figure 5.

Enolase is resistant to SpeB degradation and could be utilized as the internal control protein in analysing GAS EVs. (a) Protease K protection assay for the unknown 45 kDa protein (indicated by the arrow) in EVs from A20 and speB mutant (∆speB). EVs from A20 and speB mutant were collected by ultracentrifugation and incubated with protease K in the presence with or without 1% SDS for 60 min at 37ºC. (b) Detection of the unknown 45 kDa protein by anti-human enolase antibody. EVs from A20 were analysed by western blot with an anti-human enolase antibody. The lower panel shows the total protein in EVs. The arrow indicates the unknown 45 kDa protein. 2×, two-fold dilution. (c) Protease K protection assay for enolase in EVs. EVs were incubated with protease K in the presence with or without 1% SDS. GAS enolase was detected by an anti-human enolase antibody and the lower panel shows the total protein of EVs. (d) Detection of enolase in EV-depleted ultracentrifuged culture supernatants (UCS). The thirty- and 15-µL UCSs and EVs from A20 were analysed by western blot with the anti-human enolase antibody. (e) Utilization of enolase as the internal control protein for analysing SLO and SpeB in EVs from A20, the speB mutant, the SpeB protease-inactivated mutant (SpeBC192S), and the slo mutant (∆slo). Thirty-µL of EVs was analysed by western blot with anti-SLO, anti-SpeB, and anti-human enolase antibodies. The lower panel shows the total protein in EVs. zSpeB, the zymogen form SpeB (42 kDa); mSpeB, the mature form SpeB (28 kDa).

GAS enolase was resistant to SpeB degradation and was one of the dominant proteins in EVs; therefore, we further utilized enolase as the internal control protein to demonstrate that SLO could be degraded in EVs from the wild-type strain but not that from SpeB mutants. EVs from the overnight cultured wild-type A20 strain, the speB isogenic mutant, the SpeB protease-inactivated (SpeBC192S) mutant, and the slo mutant were collected, and SLO, SpeB, and enolase in EVs were detected by western blot hybridization. As the internal control protein, enolase was detected in EVs from all analysed strains (Figure 5e). In line with the results from Figure 2, SLO was detected in EVs from the speB mutant and SpeBC192S mutant but not in EVs from the wild-type strain and the slo mutant (Figure 5e), indicating that SLO in EVs was degraded by SpeB. Further, these results suggested that enolase could be utilized as the internal control protein for analysing GAS EVs.

Discussion

Resch et al [8] showed that the EV production is increased in the covS mutant compared to that of the wild-type strain. The covS mutant has the encapsulated cell morphology and repression of the SpeB production; however, these two phenotypes do not affect GAS EV production [8]. In this study, we hypothesized that RopB, the CovR/CovS-regulated transcriptional regulator, would participate in controlling EV production. Although RopB regulates multiple exoproteins expression in GAS [20], the results from this study did not support that RopB has roles in regulating EV production. Alternatively, we found that RopB-controlled SpeB was the EV-associated protein and has a crucial role in degrading GAS proteins in EVs. Furthermore, the downregulation of SpeB in the ropB mutant might prevent the degradation of bacterial secreted and surface proteins and result in the precipitation of protein aggregates after ultracentrifugation and high background under electron microscope observation. Therefore, SpeB has crucial roles in degrading GAS-secreted proteins, and the SpeB-positive and SpeB-negative GAS would have different protein compositions in their EVs.

EVs have been shown to have important roles in delivering bacterial toxins into host cells. The content of EVs could enter host cells through absorption and endocytosis. Therefore, EVs might deliver virulence factors in a concentrated manner to the host cells. In support of this concept, the intact EVs from Gram-positive bacteria are more cytotoxic to cells than disrupted EVs or purified toxin alone [19,36,37]. LaRock et al [17] showed that the liposome-package SpeB but not purified SpeB protein could induce pyroptosis in keratinocytes. Based on these results, we proposed that EVs, especially EV-associated SpeB, could be cytotoxic to keratinocytes. Nonetheless, EVs from both the wild-type strain and its speB mutant did not show cytotoxicity to HaCaT keratinocytes even the M.O.I. 1000 was used. EVs might need to bind to host cells for the entrance. SpeB in EVs could degrade the major GAS adhesin M protein, which might result in reducing the binding activity of EVs and therefore could not facilitate SpeB to enter the cytoplasm of HaCaT cell. In addition, we cannot rule out that EVs were eventually degraded during the endocytosis process or the concentration of SpeB delivered by EVs was not sufficient to induce cell pyroptosis.

Enolase is the glycolytic enzyme that could be the cytosolic and surface-associated protein; therefore, GAS enolase is also known as streptococcal surface enolase (SEN) [23]. Pancholi et al [34] suggested that GAS enolase contributes significantly to the streptococcal ability to bind to plasminogen. Human plasminogen is activated to plasmin, a serine protease that degrades fibrin clots. A previous study showed that streptokinase, which activates human plasminogen to plasmin, is a key pathogenicity factor for group A streptococcal infection [38]. Our results showed that enolase is the predominant EV-associated protein and is resistant to SpeB degradation. Further, M protein, the primary plasminogen-binding protein (PAM, plasminogen-binding group A streptococcal M protein) is also the EV-associated protein [38]. M protein and enolase cannot activate plasminogen; however, the EV-associated M protein and enolase might bind to plasminogen and deliver the streptokinase-activated plasminogen (plasmin) to the fibrin clot to enhance GAS dissemination. Nonetheless, the role of EV-associated enolase in GAS infection remains to be elucidated.

SpeB can cleave or degrade host matrix proteins, immunoglobulins, and complements, and therefore is the important virulence factor for GAS infection [33]. Nonetheless, SpeB could also degrade GAS-secreted toxins; therefore, preventing toxins from SpeB degradation would be a benefit for GAS infection. For example, the repression of speB expression and upregulation of GAS virulence factors such as SLO and DNases are suggested to contribute to the hypervirulent phenotype of covS mutants [9,10]. EVs have been shown to participate in bacterial pathogenesis [39]. For example, the pore-forming toxins in EVs from Listeria monocytogenes and Staphylococcus aureus contribute to the escape of bacteria from host vacuoles and the inflammasome activation in macrophages [32,40]. The present study showed that SpeB has crucial roles in changing protein composition in EVs, revealing the potential role of EV-associated SpeB in GAS infection. Although this study showed that EVs from the wild-type strain and speB mutant did not have cytotoxicity to HaCaT keratinocytes, further studies, including different infection models, would be necessary to evaluate the role of EV-associated SpeB in GAS pathogenesis.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strains and culture conditions

GAS strain A20 (emm1-type), its ropB mutant, and the SpeB-inducing peptide (SIP)-inactivated mutant was described previously [12,13,41]. GAS strains (Table 1) were cultured on trypticase soy agar containing 5% sheep blood or in tryptic soy broth (Becton Dickinson and Company; Sparks, MD, USA) supplemented with 0.5% yeast extract (TSBY). When appropriate, the antibiotics chloramphenicol (3 µg/mL) and spectinomycin (100 µg/mL) were used for selection.

Table 1.

Bacterial strains and plasmids used in this study.

| Plasmid or strain | Descriptiona | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| Plasmids | ||

| pCN143 | Temperature-sensitive, E. coli-streptococci shuttle vector | [42] |

| pCN144 | pCN143:speBT574A | [43] |

| pCN171 | pCN143:slo ∆cat | [44] |

| pCN226 | pCN143:speB ∆cat | This study |

| Strains | ||

| A20 | The emm1 wild-type strain | [41] |

| SCN142 (∆ropB) | A20 ropB isogenic mutant | [13] |

| SCN138 (SpeBC192S) | A20 SpeB C192S substituted mutant | [43] |

| SCN305 (SIP*) | A20 SIP-inactivated mutant | [12] |

| SCN344 (∆speB) | A20 speB isogenic mutant | This study |

| SCN356 (∆slo) | A20 slo isogenic mutant | [44] |

Note: a, cat, chloramphenicol cassette.

DNA and RNA manipulations

Bacterial RNA extraction and reverse transcription were performed as previously described [45]. Real-time PCR was performed in a 20 µL reaction mixture containing 1 µL of cDNA, 0.8 µL of primers (10 µM), and 10 µL of SensiFASTTM SYBR Lo-ROX pre-mixture (Bioline Ltd; London, UK) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Biological replicate experiments were performed using three independent RNA preparations in duplicates. The expression level of slo was detected with primers slo-F-1 and slo-R-1 [46], normalized to gyrA, and analysed using the ∆∆Ct method (QuantStudio™ 3 System, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; Rockford, IL, USA). In addition, all values of the control and experimental groups were divided by the mean of control samples before statistical analysis [47]. Primers used for real-time PCR analysis were designed using Primer3 (v.0.4.0, http://frodo.wi.mit.edu) according to the MGAS5005 sequence (NCBI accession number CP000017.2).

Construction of speB, slo, SpeB protease inactivated (SpeBC192S) mutants

To construct the speB mutant, the speB gene including its upstream (549 bp) and downstream (532 bp) regions were amplified by primers del-speB-Ba-2-F (5’-tttggatcccttgtcaactgaaatgagca-3’) and del-speB-Ba-2-R (5’-tctggatcccaaaaatcgtaaaaggactga-3’) and ligated into the temperature shuttle vector pCN143 [43]. The speB gene in this plasmid was removed by PCR with the reverse primers a-speB-SacII-F (5’-tagccgcggtatggaaatgcatttcg-3’) and a-speB-SacII-R (5’-catccgcggtttttttatacctcttt-3’) and replaced by the chloramphenicol cassette from Vector-78 [48]. The constructed plasmid, pCN226, and pCN171 (for construction of the slo mutant) [44] and pCN144 (for construction of SpeB C192S substitution) [45] were transformed into the wild-type A20 strain by electroporation and the transformants were selected as described previously [42]. The deletions and mutations in the target genes were confirmed by Sanger sequencing.

Isolation of extracellular vesicles (EVs)

The extracellular vesicles (EVs) were isolated based on the ultracentrifugation method. GAS strains were grown to the early-stationary phase (O.D.600 = 1.0) or cultured for 8–16 h at 37ºC with 5% CO2 supplementation. The bacterial culture supernatants were collected, and bacterial cells were removed by utilizing an 0.22 µm filter (Millipore; MA, USA). The cell-free culture supernatant, with or without 100 kDa centrifugal filter (Millipore) concentrated, was centrifugated at 3300 ×g at 4ºC for 10 min to remove the debris. Finally, the supernatant was centrifugated at 175,000 ×g at 4ºC for 4 h. The resulting pellet (EVs) was resuspended by sterilized 1× PBS and stored at −80ºC before analysis.

Nanoparticle tracking and qNano analyses

The number and size of EVs were analysed by nanoparticle tracking analysis (NTA) and the tunable resistive pulse sensing system (TRPS). Nanosight NS300 (Malvern Panalytical; Malvern, UK) was utilized for nanoparticle tracking analysis. A camera level of 14 and a gain of 1 were applied for the data collection. Frame sequences were analysed with a screen gain of 10 and a detection threshold of 5. Each sample was analysed three times for 60 s at 25ºC with Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis software (Version 3.1). qNano Gold (Izon Science Ltd.; Christchurch, New Zealand) was utilized for TRPS analysis. The nanopore NP150 was prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Izon Science Ltd.) and was stretched to 47.5 mm by using digital calipers to measure the distance between two opposite arms. The optimized setting for the measurements was determined by using 40 µl of PBS in the upper fluid cell, with a variable pressure module applied to 7 mbar positive pressure and the current ranged between 100–120 nA. The diluted calibration particles were measured by qNano Gold with the optimal settings as the positive control.

Negative stain-transmission electron microscope imaging

The isolated EVs (4 µL) were dropped on the Formvar/carbon-supported copper grids and incubated at room temperature for 1 min. The grids were washed with water, and the excess water was removed by filter papers. For negative staining, the grids were treated with 2% uranyl acetate for 1 min, air-dried, and the images were acquired by the transmission electron microscope (JEM-1400 m JEOL Ltd.; Akishima, Tokyo, Japan).

Protease K protection assay

The isolated EVs were incubated with 0.5–2 µg/mL protease K in the presence with or without 1% SDS at 37ºC for 1 h. After incubation, the protease K activity was blocked by 1 M Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF; Merck, Darmstadt, Germany). The samples were mixed with 6× protein loading dye, boiled for 5 min, and analysed by 10% SDS-PAGE and western blot hybridization.

Western blot hybridization

Bacterial culture supernatants (with or without 100 kDa filter concentration) and EVs were mixed with 6× protein loading dye and loaded into a 10% SDS-PAGE. The separated proteins were transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBST buffer (phosphate-buffered saline containing 0.2% vol/vol Tween 20) at 37ºC for 1 h. SpeB and SLO were detected by anti-SpeB (Toxin Technology, Inc.; Sarasota, IL, USA) and anti-SLO antibodies (GeneTex; Irvine, CA, USA), respectively. Enolase (streptococcal surface enolase, SEN) was detected by the ENO1 polyclonal antibody (PA5–116513, Invitrogen; Waltham, MA, USA) with 1:1000 dilution. After hybridization at 4ºC for 16–24 h, the membrane was washed with PBST buffer and hybridized with a secondary antibody, peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Cell Signaling Technology, Inc.; Danvers, MA, USA) at room temperature for 1 h. The blot was developed using Pierce ECL Western blotting substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.; Rockford, IL, USA) and the signals were detected with Gel Doc XR+ system (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.; Hercules, CA, USE).

Cytotoxicity assay

GAS strains were grown for 12–16 h. The bacterial culture supernatant (with 0.22 µm filtration), the concentrated bacterial culture supernatant (by using a 10 kDa centrifugal filter), and EVs (by ultracentrifugation) were collected. For evaluating the cytotoxicity of the bacterial supernatants, the attached HaCaT cells were incubated with the conditional medium (the 900 µl of phenol red-free and FCS-free DMEM medium and 100 µL of culture supernatants or the 20-fold concentrated culture supernatants) at 37ºC for 4 h. The cytotoxicity was determined by detecting the release of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) from the infected cells by CytoTox96® Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega; Fitchburg, WI, USA) according to the manual. The cytotoxicity (%) was calculated as follows: [(sample LDH – medium blank)/(maximum LDH – medium blank)] × 100. The maximum LDH was defined as the LDH released from uninfected cells treated with lysis buffer for 45 min at 37ºC.

Protein ID by mass spectrometry

To identify the unknown protein, the target protein was obtained from the 10% SDS-PAGE and digested with sequencing-grade modified porcine trypsin (Promega) at 37ºC for 16 h. The peptides were extracted from the gel, dried by vacuum centrifugation, and analysed by LC-MS/MS with Xcalibur software (version 2.2, Therma Fisher Scientific Inc.). The full-scan MS was performed in the Orbitrap LC-MS over a range of 400–2000 Da and a resolution of 120,000 at m/z 400. Raw data were analysed by Proteome Discoverer software (version 2.3, Therma Fisher Scientific Inc.). The MS/MS spectra were searched against the UniPro database (https://www.uniprot.org) with the Mascot search engine (Matrix Science, version 2.5).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using Prism software, version 5 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Significant differences between multiple groups were determined using ANOVA. Post-tests for ANOVA were performed using Tukey’s honestly significant difference test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors appreciate the assistance from Prof. Lichieh-Julie Chu (Molecular Medicine Research Center, Chang Gung University, Taiwan) for the nanoparticle tracking system (NTA) analysis.

Funding Statement

This work is supported by grants from the Chang Gung Memorial Hospital at Linkou, Taiwan (BMRPD19) and the National Science and Technology Council, Taiwan (111-2320-B-182-033 and 112-2320-B-182-002).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/21505594.2023.2249784

References

- [1].Deatherage BL, Cookson BT, Andrews-Polymenis HL.. Membrane vesicle release in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: a conserved yet underappreciated aspect of microbial life. Infect Immun. 2012;80(6):1948–13. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06014-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Beveridge TJ. Structures of gram-negative cell walls and their derived membrane vesicles. J Bacteriol. 1999;181(16):4725–4733. doi: 10.1128/JB.181.16.4725-4733.1999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Kulkarni HM, Jagannadham MV. Biogenesis and multifaceted roles of outer membrane vesicles from Gram-negative bacteria. Microbiology (Reading). 2014;160(10):2109–2121. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.079400-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Biagini M, Garibaldi M, Aprea S, et al. The human pathogen Streptococcus pyogenes releases lipoproteins as lipoprotein-rich membrane vesicles. Mol & Cell Proteomics. 2015;14(8):2138–2149. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M114.045880 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Prados-Rosales R, Baena A, Martinez LR, et al. Mycobacteria release active membrane vesicles that modulate immune responses in a TLR2-dependent manner in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(4):1471–1483. doi: 10.1172/JCI44261 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Lee EY, Choi DY, Kim DK, et al. Gram-positive bacteria produce membrane vesicles: proteomics-based characterization of Staphylococcus aureus-derived membrane vesicles. Proteomics. 2009;9(24):5425–5436. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Cunningham MW. Pathogenesis of group A streptococcal infections and their sequelae. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;609:29–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Resch U, Tsatsaronis JA, Le Rhun A, et al. A two-component regulatory system impacts extracellular membrane-derived vesicle production in group A Streptococcus. mBio. 2016;7:e00207–16. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00207-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ikebe T, Ato M, Matsumura T, et al. Highly frequent mutations in negative regulators of multiple virulence genes in group A streptococcal toxic shock syndrome isolates. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(4):e1000832. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sumby P, Whitney AR, Graviss EA, et al. Genome-wide analysis of group A streptococci reveals a mutation that modulates global phenotype and disease specificity. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2(1):e5. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Churchward G. The two faces of Janus: virulence gene regulation by CovR/S in group A streptococci. Mol Microbiol. 2007;64(1):34–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05649.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Shi YA, Chen TC, Chen YW, et al. The bacterial markers of identification of invasive CovR/CovS-inactivated group A Streptococcus. Microbiol Spectr. 2022;10:e0203322. doi: 10.1128/spectrum.02033-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chiang-Ni C, Chen YW, Chen KL, et al. RopB represses the transcription of speB in the absence of SIP in group A Streptococcus. Life Sci Alliance. 2023;6(6):e202201809. doi: 10.26508/lsa.202201809 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Do H, Makthal N, VanderWal AR, et al. Environmental pH and peptide signaling control virulence of Streptococcus pyogenes via a quorum-sensing pathway. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):2586. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-10556-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Do H, Makthal N, VanderWal AR, et al. Leaderless secreted peptide signaling molecule alters global gene expression and increases virulence of a human bacterial pathogen. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(40):E8498–E507. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1705972114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Wu ZY, Campeau A, Liu CH, et al. Unique virulence role of post-translocational chaperone PrsA in shaping Streptococcus pyogenes secretome. Virulence. 2021;12(1):2633–2647. doi: 10.1080/21505594.2021.1982501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].LaRock DL, Johnson AF, Wilde S, et al. Group A Streptococcus induces GSDMA-dependent pyroptosis in keratinocytes. Nature. 2022;605(7910):527–531. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04717-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Deng W, Bai Y, Deng F, et al. Streptococcal pyrogenic exotoxin B cleaves GSDMA and triggers pyroptosis. Nature. 2022;602(7897):496–502. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-04384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Brown L, Wolf JM, Prados-Rosales R, et al. Through the wall: extracellular vesicles in Gram-positive bacteria, mycobacteria and fungi. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2015;13(10):620–630. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3480 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Chaussee MS, Watson RO, Smoot JC, et al. Identification of Rgg-regulated exoproteins of Streptococcus pyogenes. Infect Immun. 2001;69(2):822–831. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.2.822-831.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Tjia-Fleck S, Readnour BM, Ayinuola YA, et al. High-resolution single-particle cryo-EM hydrated structure of Streptococcus pyogenes enolase offers insights into its function as a plasminogen receptor. Biochemistry. 2023;62(3):735–746. doi: 10.1021/acs.biochem.2c00637 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Derbise A, Song YP, Parikh S, et al. Role of the C-terminal lysine residues of streptococcal surface enolase in Glu- and Lys-plasminogen-binding activities of group A streptococci. Infect Immun. 2004;72(1):94–105. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.1.94-105.2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Antikainen J, Kuparinen V, Lahteenmaki K, et al. Enolases from Gram-positive bacterial pathogens and commensal lactobacilli share functional similarity in virulence-associated traits. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2007;51(3):526–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.2007.00330.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].von Pawel-Rammingen U, Bjorck L. IdeS and SpeB: immunoglobulin-degrading cysteine proteinases of Streptococcus pyogenes. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2003;6(1):50–55. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(03)00003-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Bisno AL, Brito MO, Collins CM. Molecular basis of group A streptococcal virulence. Lancet Infect Dis. 2003;3(4):191–200. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(03)00576-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Graham MR, Smoot LM, Migliaccio CA, et al. Virulence control in group A Streptococcus by a two-component gene regulatory system: global expression profiling and in vivo infection modeling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:13855–13860. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202353699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chiang-Ni C, Kao CY, Hsu CY, et al. Phosphorylation at the D53 but not the T65 residue of CovR determines the repression of rgg and speB transcription in emm1- and emm49-type group A streptococci. J Bacteriol. 2019;201(4):e00681–18. doi: 10.1128/JB.00681-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Murase K, Aikawa C, Nozawa T, et al. Biological effect of Streptococcus pyogenes-released extracellular vesicles on human monocytic cells, induction of cytotoxicity, and inflammatory response. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:711144. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2021.711144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Aziz RK, Pabst MJ, Jeng A, et al. Invasive M1T1 group A Streptococcus undergoes a phase-shift in vivo to prevent proteolytic degradation of multiple virulence factors by SpeB. Mol Microbiol. 2004;51:123–134. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03797.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Doran JD, Nomizu M, Takebe S, et al. Autocatalytic processing of the streptococcal cysteine protease zymogen: processing mechanism and characterization of the autoproteolytic cleavage sites. Eur J Biochem. 1999;263:145–151. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00473.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Chen CY, Luo SC, Kuo CF, et al. Maturation processing and characterization of streptopain. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(19):17336–17343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209038200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Wang X, Eagen WJ, Lee JC. Orchestration of human macrophage NLRP3 inflammasome activation by Staphylococcus aureus extracellular vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(6):3174–3184. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1915829117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Rasmussen M, Bjorck L. Proteolysis and its regulation at the surface of Streptococcus pyogenes. Mol Microbiol. 2002;43(3):537–544. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Pancholi V, Fischetti VA. α-enolase, a novel strong plasmin(ogen) binding protein on the surface of pathogenic streptococci. J Biol Chem. 1998;273(23):14503–14515. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.23.14503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Fontan PA, Pancholi V, Nociari MM, et al. Antibodies to streptococcal surface enolase react with human alpha-enolase: implications in poststreptococcal sequelae. J Infect Dis. 2000;182:1712–1721. doi: 10.1086/317604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Marsollier L, Brodin P, Jackson M, et al. Impact of Mycobacterium ulcerans biofilm on transmissibility to ecological niches and buruli ulcer pathogenesis. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3(5):e62. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030062 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Thay B, Wai SN, Oscarsson J, et al. Staphylococcus aureus α-toxin-dependent Induction of host cell death by membrane-derived vesicles. PLoS One. 2013;8:e54661. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0054661 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Sun H, Ringdahl U, Homeister JW, et al. Plasminogen is a critical host pathogenicity factor for group A streptococcal infection. Science. 2004;305(5688):1283–1286. doi: 10.1126/science.1101245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Briaud P, Carroll RK, Richardson AR. Extracellular vesicle biogenesis and functions in gram-positive bacteria. Infect Immun. 2020;88(12):88. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00433-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Coelho C, Brown L, Maryam M, et al. Listeria monocytogenes virulence factors, including listeriolysin O, are secreted in biologically active extracellular vesicles. J Biol Chem. 2019;294(4):1202–1217. doi: 10.1074/jbc.RA118.006472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Chiang-Ni C, Zheng PX, Ho YR, et al. emm1/sequence type 28 strains of group A streptococci that express covR at early stationary phase are associated with increased growth and earlier SpeB secretion. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47(10):3161–3169. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00202-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Chiang-Ni C, Chu TP, Wu JJ, et al. Repression of Rgg but not upregulation of LacD.1 in emm1-type covS mutant mediates the SpeB repression in group A Streptococcus. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:1935. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Chiang-Ni C, Shi YA, Lai CH, et al. Cytotoxicity and survival fitness of Invasive covS mutant of group A Streptococcus in phagocytic cells. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2592. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Tsai WJ, Lai YH, Shi YA, et al. Structural basis underlying the synergism of NADase and SLO during group A Streptococcus infection. Commun Biol. 2023;6(1):124. doi: 10.1038/s42003-023-04502-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Wang CH, Chiang-Ni C, Kuo HT, et al. Peroxide responsive regulator PerR of group A Streptococcus is required for the expression of phage-associated DNase Sda1 under oxidative stress. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81882. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081882 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Chiang-Ni C, Tseng HC, Hung CH, et al. Acidic stress enhances CovR/S-dependent gene repression through activation of the covR/S promoter in emm1-type group A Streptococcus. Int J Med Microbiol. 2017;307(6):329–339. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2017.06.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Valcu M, Valcu CM. Data transformation practices in biomedical sciences. Nat Methods. 2011;8(2):104–105. doi: 10.1038/nmeth0211-104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Tsou CC, Chiang-Ni C, Lin YS, et al. Oxidative stress and metal ions regulate a ferritin-like gene, dpr, in Streptococcus pyogenes. Int J Med Microbiol. 2010;300(4):259–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.