ABSTRACT

Aim:

We aimed to assess the service user’s acceptability, feasibility, and attitude toward telemedicine practice and compare it with in-person consultation in substance use disorder (SUD).

Materials and Methods:

We recruited 15 adult patients with SUD who accessed both telemedicine and in-person care. We conducted in-depth interviews on awareness and access, facilitators and barriers, treatment satisfaction, and therapeutic relationship in the telemedicine context. We performed a conventional content analysis of the interview excerpts and used inductive and deductive coding. We assumed that social, personal, and logistic contexts influence patients’ perceptions and experiences with telemedicine-based addiction care (TAC).

Results:

Most participants were middle-aged men (40.5 years, 86.7%), dependent on two or more substances (86.7%), and had a history of chronic, heavy substance use (use ~16 years, dependence ~11.5 years). Patients’ perspectives on TAC could broadly be divided into three phases: pre-consultation, consultation, and post-consultation. Patients felt that TAC improved treatment access with adequate autonomy and control; however, there were technical challenges. Patients expressed privacy concerns and feared experiencing stigma during teleconsultation. They reported missing the elaborate inquiry, physical examination, and ritual of visiting their doctors in person. Additionally, personal comfort and technical difficulties determine the satisfaction level with TAC. Overall perception and suitability of TAC and the decision to continue it developed in the post-consultation phase.

Conclusion:

Our study provides an in-depth insight into the barriers and facilitators of telemedicine-based SUD treatment access, use, and retention; it also helps to understand better the choices and preferences for telehealth care vis-à-vis standard in-person care for SUDs.

Keywords: Barriers, facilitators, qualitative analysis, telemedicine-based addiction care (TAC)

INTRODUCTION

India has a sizeable population with substance misuse. The latest report estimated that there were 57 million people with problematic alcohol use, nearly eight million with opioids, and seven million with cannabis misuse.[1] To put this into a global perspective, the World Drug Report, 2021, estimated around 36 million people with drug use disorders.[2] Hence, nearly one in five people with drug use disorders live in India. However, only a fourth of those requiring treatment receive any help. The proportion is much less for those who receive evidence-based treatment for substance use disorders (SUDs).[1] The pandemic and associated restrictions have made it more difficult for patients to access treatment. A multicenter survey showed that three of four patients had difficult treatment and medication access.[3] However, the pandemic has forced society to use technology to deliver mental health services globally and in India.[4-6]

Telemedicine entails the ability of healthcare providers to communicate with patients, diagnose conditions, provide treatment, discuss healthcare issues with other providers, and ensure quality healthcare services are provided with the aid of telecommunication technology.[7] Telepsychiatry is the provision of providing mental health care using telecommunication.[6] Tele-mental health care might increase access to services and provide extended support when patients are outside the therapeutic setting.[8] Although researchers are less sure about the relative effectiveness of telehealth-delivered medication management, individual counseling via telehealth and other Web-based behavioral interventions might be as effective as similar in-person interventions.[9,10] The treatment delivered through telemedicine has to overcome other potential challenges, such as privacy violations, patient denial, and limited autonomy in proactive teleconsultations.[11] The service providers’ and the receivers’ satisfaction must also be considered while shifting to a different mode of service delivery.

Studies suggest that treatment delivered through digital mode is as effective as traditional care in treating SUDs.[9,12] A retrospective cohort study from the USA compared the treatment discontinuation between telemedicine and in-person care. The authors found that telemedicine-based care reduces the risk of treatment discontinuation for SUD and mental illness.[13] Telemedicine can also potentially increase access to SUD treatment across geographic areas.[14] Therefore, telemedicine promises to address the enormous SUD treatment gap in India. However, it is essential to understand the service users’ perspectives for conceiving and implementing acceptable, accessible, and effective telemedicine services for SUD. A multisite survey from the USA showed that most tele-mental health service users found the overall experience as “excellent,” and nearly two-thirds rated tele services at par with in-person treatment. Nevertheless, a sizeable minority felt “less connected” with the treatment providers.[15] Another USA-based qualitative research revealed a positive outlook of opioid-dependent patients toward telehealth. Most participants informed that teleconsultation helped reduce social barriers and speed up treatment access.[16] A recent Indian study from an addiction treatment center showed that patients’ perception of providers’ empathy and quality of therapeutic alliance were lesser in telemedicine-based treatment than in in-person treatment. Nearly half of the patients were unsatisfied with telemedicine access and expressed privacy concerns.[17] The variable study results might have been caused by different study populations (mental illness vs. SUD) and cultural and contextual factors. A few of these contextual challenges for India, such as legal and ethical concerns, inadequate human resources, and technological infrastructure, were highlighted by others.[18] Qualitative studies will help to further the understanding of the service users’ perceptions of scopes and challenges and attitudes toward telemedicine-based addiction treatment. A study from the USA comprising predominantly white participants with opioid use disorder (OUD) identified two overarching themes availability—accommodation and acceptability—appropriateness. While the first domain was about the structural aspects, the other domain alluded to the relational aspects of telemedicine. The authors emphasized the flexibility in service delivery and users’ choice.[19] It is essential to see the SUD service users’ perspectives from different cultural and contextual vantage points to adapt to the differing needs and preferences.

This study aimed to explore the service user’s preferences, perceptions, and attitudes toward telemedicine-based SUD treatment, vis-a-vis traditional in-person SUD care.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Conceptual framework and study design

The study is based on a conventional content analysis framework. This framework allows us to derive a condensed and broad understanding of a phenomenon. Our content analysis was not theory-driven, but it was data-driven. We did not use any preconceived categories, instead allowed the codes and names for codes to flow from the data. Researchers immersed themselves in the data to allow new insights to emerge. The codes and categories/themes thus generated allowed us to understand the phenomenon (“telemedicine-assisted addiction treatment”). We also built a thematic map.

We believed that the patients accessing telemedicine-based addiction care (TAC) share a common set of challenges and opportunities. Considering these factors, we formulated the methodological approach, interview guide, and subsequent analysis. We used both inductive coding and deductive coding of the content.[20,21] We used the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ), a checklist developed to promote comprehensive reporting of a qualitative study.[22]

Research team

The research team included three male (AG, SKM, and TM) and two female (APV and MK) researchers. AG and SKM were consultant psychiatrists with more than ten years of research experience. TM, a senior resident, and APV, a Ph.D. scholar in the department of addiction psychiatry, had around five years of research experience. MK was a psychiatric social worker (fifteen years of research experience). AG and SKM guided the formation of an interview guide, whereas TM, APV, and MK performed the interviews and coded and analyzed the data under the guidance of AG.

Study settings

In the wake of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)-related nationwide lockdown, we started telemedicine-based addiction treatment to provide care to patients with SUD in May 2020. The TAC is a synchronous, stepwise, hierarchical direct care model consisting of telephonic, video, and in-person consultation. A psychiatrist with a postgraduate degree provides all levels of consultations. The telephonic consultation aims to obtain a brief history, perform a basic clinical assessment, choose treatment intensity, provide a brief psychological intervention, and explain further treatment approaches. Video consultation (VC) is considered for patients requiring detailed clinical assessment (e.g., dual diagnosis and complicated withdrawals), prescribing medications, and confirming patient identity. The VC happened on a Zoom platform or through a WhatsApp video call. The patients requiring detailed physical examination (because of medical comorbidities and presence of severe withdrawals), those with a risk of suicide or overdose, and those requiring medication that cannot be prescribed through telephonic consultation are advised in-person visits. We presented a detailed description of our model elsewhere.[6]

Study participants

We used the data saturation principle to decide on the sample size. We defined saturation as the point at which two consecutive unique interviews reveal no additional themes/subthemes.[23] The final sample comprised 15 adult patients with SUDs who attended both in-person and VC at the TAC service. The participants were recruited between June and October 2021. We included patients from both genders and all types of SUDs, except with exclusive tobacco use disorders. The interviewers had a therapeutic relationship with all the participants. The patients with both physical and psychiatric comorbidities were also included in our study. We excluded seven patients: three refused consents, two were intoxicated, and two could not talk due to poor networks.

Data collection

The institutional ethics committee approved the study. Subsequently, the study team met to generate the interview guide. The initial agreed-upon principles for the interview were to ask open-ended questions, allow reflection on the patient’s experience, and avoid asking “why” questions (as asking why may increase resistance or provoke avoidance) or offer examples as much as possible. We identified the patients and obtained their informed consent. Subsequently, TM and MK interviewed them with the guidance of AG. The interview began with a brief introduction and inquiry regarding the patients’ pathway to care leading to TAC. Afterward, the patients were asked about their experience with TAC. We also enquired about their expectation from the TAC and their perception of the quality of care. With these parameters, we tried to understand the patients’ acceptability attitude and the feasibility of availing of TAC.

Data analysis

The interviews were conducted through video conferencing or in person, whichever the patients preferred. We recorded all the interviews. Later on, the interviews were converted into transcripts by APV. AG, APV, and TM read through the transcripts of five interviews and generated codes inductively. A code dictionary was created for further coding. APV and TM deductively coded the transcripts in Delve software separately. The inter-rater agreement was 78 percent. Similar and recurrent codes were combined to create themes. The total number of common themes identified by both TM and APV was 18. Two unique themes were identified by APV and five by TM. The total number of themes identified was 25. The conflicts between the raters were resolved after a discussion with AG. Subsequently, we performed the final coding and generated the themes, subthemes, and codes. Thereafter, we prepared the thematic map.

RESULTS

Socio-demographic and clinical details

There were 15 participants in the study. The majority were middle-aged adults (mean age: 40.5 ± 11.3 years, range: 24-58 years), males (86.7%), married (66.7%), employed (86.7%), Hindu by religion (66.7%), urban residents (60%), and residing within 40 km distance (60%). Most patients had alcohol (66.7%) and tobacco (73.3%) use disorders. Most of the participants were dependent on two or more substances (86.7%). The average substance use duration was around 16 years (mean: 192 ± 133.3 months; range: 36–372 months), and dependence was around 11.5 years (mean: 113.6 ± 78.2; range: 30–240 months). The mean duration of the interviews was around half an hour (mean: 29.2 ± 6.8; range: 17–49 minutes). For further details, see Table 1.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical details of the study population

| Variables | Mean±SD (range)/number (percentage) |

|---|---|

| Socio-demographic variables | |

| Age | 40.5±11.3 (24-58) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 13 (86.7) |

| Female | 2 (13.3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 3 (20) |

| Married | 10 (66.7) |

| Divorced/separated | 2 (13.3) |

| Employment status | |

| Unemployed | 2 (13.3) |

| Employed | 13 (86.7) |

| Religion | |

| Hindu | 10 (66.7) |

| Sikh | 3 (20) |

| Others | 2 (13.3) |

| Domicile | |

| Rural | 6 (40) |

| Urban | 9 (60) |

| Distance from hospital | |

| Local | 7 (46.7) |

| Up to 40 km | 2 (13.3) |

| 40–80 km | 4 (26.7) |

| Above 80 kms | 2 (13.3) |

| Clinical variables | |

| Duration of use (months) | 192±133.3 (36-372) |

| Duration of dependence (months) | 113.6±78.2 (30-240) |

| Duration of interview (minutes) | 29.2±6.8 (17-49) |

| Substance use profile | |

| Alcohol | 10 (66.7) |

| Opioids | 6 (40) |

| Sedatives | 3 (20) |

| Cannabis | 3 (20) |

| Tobacco | 11 (73.3) |

| Past treatment | |

| Present | 7 (46.7) |

| Absent | 8 (53.3) |

| Psychiatric illness | |

| Absent | 7 (46.7) |

| Anxiety spectrum | 4 (26.6) |

| Mood disorder | 3 (20) |

| Psychotic spectrum | 1 (6.7) |

| Present | 6 (40) |

| Absent | 9 (60) |

SD=Standard deviation, KM=Kilometer

Themes, subthemes, and codes

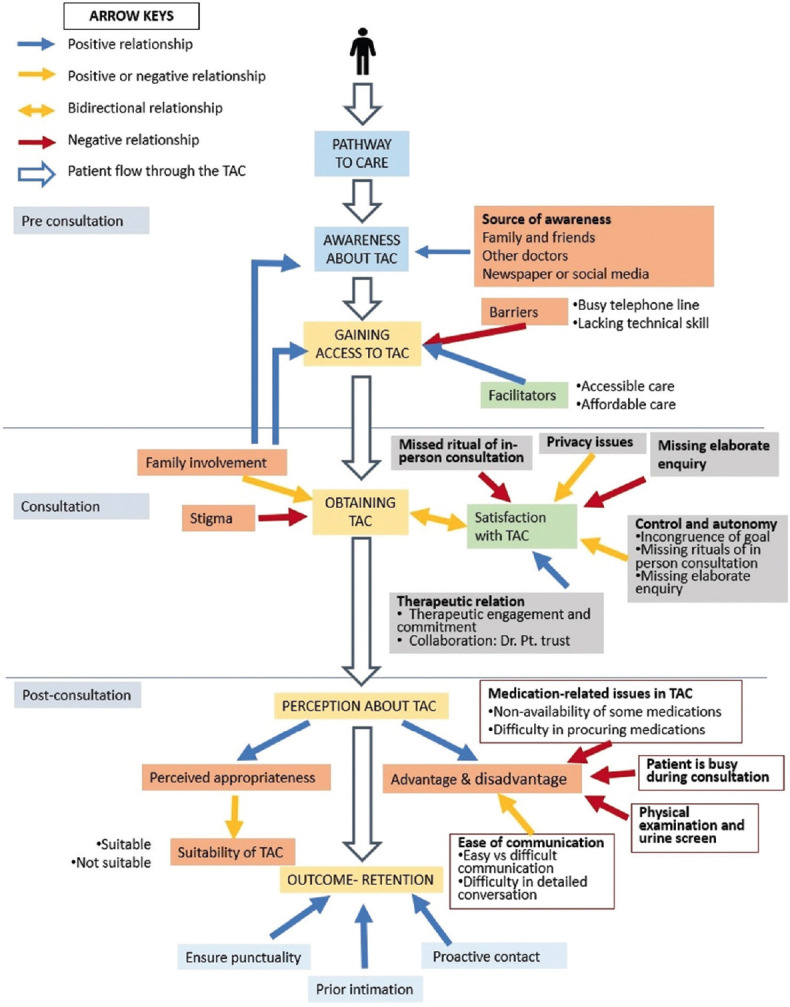

From the patients’ perspective, TAC could broadly be divided into pre-consultation, consultation, and post-consultation phases. Pre-consultation is the preparatory phase, where the patient acquires knowledge about TAC and decides to access the TAC service. Subsequently, the doctor from the tele-outpatient department (OPD) contacts the patient, and after the consultation, the prescription is provided. During the post-consultation phase, the patient evaluates the TAC, forms an opinion about its suitability for TAC, and decides to continue (or discontinue) the TAC. The interrelations between various themes are shown in the concept map [Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Concept map of various themes and subthemes. TAC = telemedicine-based addiction care, OPD = outpatient department

Pre-consultation phase

The pre-consultation phase precedes teleconsultation. “Gaining access to TAC” was the main theme, whereas awareness about TAC and barriers and facilitators to TAC access were the identifiable subthemes. The TAC started during COVID-19 lockdown. As a result, the main mode of awareness was verbal, media reports, and social media posts. The patients acquired knowledge of the TAC service from various sources such as family members and friends, newspapers, or other doctors. Some had visited the in-person OPD to learn about the provision of TAC.

Accessibility to health care can be assessed on the availability, utilization, and outcome of healthcare service, but here we focused on the easy and timely use of TAC to achieve a favorable outcome to denote accessibility.[24] The patients faced several barriers to accessing TAC: modifiable financial, structural, and/or cognitive factors limiting TAC access.[25] A busy telephone line was by far the most common barrier faced by around 60% of patients while accessing the TAC services. Lack of technical skills to handle digital technology often hinders telehealthcare access, especially in aged and less educated patients. The facilitators to TAC access are those factors easing telehealth accessibility. The accessible care in time of movement restriction and affordability in terms of time, travel, and money facilitated the use of TAC. For further details, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Themes, subthemes, and codes with relevant excerpts from pre-consultation phase

| Theme | Subtheme | Code | Verbatim |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gaining access to TAC | Awareness about TAC | Source of awareness[14] | Mr S (Patient 13): “We came across a news sir, regarding the tele OPD of various departments of PGI, published in the Tribune after the lockdown. It also contained phone numbers, to which we contacted.” Mrs N (Patient 8): “My friend had sent me all the PGI tele OPD numbers through Whatsapp. She informed that I can consult through these numbers to get registered.” Mrs P (Patient 10): “Ma’am, I called Dr. M about my problem. He told me about the tele OPD. He had given me the number and told me that after registration, I would get a call after 3-4 hours from DDTC.” |

| Barriers to TAC access | Busy telephone line[11] | Mr. A (Patient 11): “getting an appointment is difficult. Sometimes the phone is not available. Sometimes the call goes on waiting, sometimes the call doesn’t connect because of signal issues.” Mrs N (Patient 8): “I call often but it takes time, mostly it is busy. However, I used to try continuously. Some days, they attend my call without any delay, and sometimes it takes much time to pick the call up.” Mr S (Patient 14): “Sir, sometimes we get registered after 2–3 times of trying, and it gets connected, but sometimes, it is busier, and we have to try even 100 times to get a connection for getting registered.” | |

| Lacking technical skill[4] | Mr. N (Patient 7): “only problem is operating phone. You sometimes ask for video call. I am not much acquainted with smartphone and video call app.” Mr. C (Patient 3): “I didn’t know how to do that, as I am unable to handle smartphone.” | ||

| Facilitators to TAC access | Accessible care[7] | Mrs N (Patient 8): “Yes sir, it is so comfortable and convenient for me. Due to corona, it was so difficult, as you can’t go anywhere due to the Lockdown, or fear of catching an infection, but TAC reduced the difficulty. Now I can register to your OPD from my home.” Mr S (Patient 14): “my relatives told me that if we go to PGI, its very rush and have to get into the line for a long time. In that respect, now it becomes very easy that we can contact them over phone and later the doctor will call us back.” | |

| Affordable care[10] | Mr. A (Patient 11): “appointment is taken early in the day. I can attend your call from my college. I can directly go and buy medicines. Hence, I get time for my college work and daily chores.” Mr G (Patient 5) [resident of a faraway place (around 750 km away)]: “the cost is high to come here from Ladakh. It costs a few thousand to come here with an attendant, and not everyone can afford that.” Mrs P (Patient 10) [health worker from a remote place]: “A big advantage is that, we don’t have to travel. We need to change a couple buses to reach Chandigarh from Morni. Beside this, the buses from Morni don’t have a fixed timing.” |

TAC=Telemedicine-based addiction care

Consultation phase

The consultation phase involves the themes such as obtaining TAC and satisfaction with teleconsultation.

An addictive disorder consultation can be defined as an interaction between an addiction specialist and a person with addictive disorders regarding some addiction-related issue to help the person regarding the addictive disorders.[26] The consultations shape the therapeutic relationship, satisfaction, and patient’s attitude toward the TAC service.

There is a significant extent of family involvement in the decision-making and treatment proper (like registration and arrangements for TAC). The main reasons for their involvement are to help patients circumvent their deficient technical skills and language barrier or to remain updated about their treatment. Apparently, in skill-deficient patients, it is an indispensable part of teleconsultation. Some other patients have a positive feeling about family involvement. For some patients, family involvement was a form of unwanted intrusion, leading to chaos.

Stigma is the negative attitudes (prejudice) and behavior (discrimination) toward people with mental illness and SUD. Stigma against SUD comes from society, sometimes from healthcare providers, and often it is internalized in the patient as she or he starts believing in the negative narratives.[27] The stigma often hinders treatment seeking, and more so, when the patient has to take consultation in front of family or friends.

Satisfaction with teleconsultation is a nonspecific but important determinant in treatment engagement. The patients’ satisfaction depends on various factors related to a patient, care provider, and technical aspects.[28]

Privacy, control, autonomy, elaborate inquiry, therapeutic relationship, and ritual of in-person consultation are the main determinants of patients’ satisfaction. Privacy is the patient’s freedom to choose the time, the circumstances, and the extent to which they would like to share or withhold their beliefs, behavior, and opinions.[29] It is the patients’ right during consultation and an essential prerequisite for proper diagnosis and effective treatment.[30] The perceived deficit of privacy plays a major role in patient satisfaction in TAC. Patient’s autonomy in TAC is often threatened by the incongruence of goals between patient and doctor and a perceived loss of control, as some patients consider that the doctor usually jumps to a conclusion while providing teleconsultation. On the contrary, some patients, especially females, perceived enhanced control during teleconsultation. The therapeutic relationship is a collaborative relationship between the therapist and the client.[31] The patients identified therapeutic engagement, commitment, collaboration, and doctor–patient trust as important factors for the therapeutic relationship. Some patients perceived a lack of elaborate inquiry in teleconsultation compared with an in-person consultation. Besides this, the visit to the doctor for healing has ritualistic implications for some patients, which marks the event as sacred or socioculturally transformative.[32] As a result, those patients miss the apparently cumbersome in-person consultation. For further details, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Themes, subthemes, and codes with relevant excerpts from consultation phase

| Theme | Subtheme | Code | Verbatim |

|---|---|---|---|

| Obtaining TAC | Family involvement | Reason[11] | Mr N (Patient 7): “my daughter would do registration. When the call comes, she gives me the phone, or connects to the video, and I would talk to doctor. I do not know the smartphone or video call.” Mr. G (Patient 6) (middle aged farmer explained about the daughter’s involvement during consultation): “I am not efficient in using mobiles. Besides, my daughter understands Hindi better than me.” Mr. G (Patient 5): “As the family wants to know how treatment is done, they wish to sit with the patient.” When he was asked about his feeling, he told “At first there was a hesitation, but as she got to know more about me, the hesitation decreased.” |

| Effect[10] | Positive feeling: Mrs N (Patient 8) felt “my husband used to sit with me during the sessions, and I don’t have any problem with that. Actually, I feel good about his support.” | ||

| Unwanted intrusion: Mr. S told about his mother, “If we sat together on call, it would be chaotic. My mother would have said he is doing so and so, I would have said, ‘she’s lying, give me the phone’. The doctor would have not understood anything, nobody would have understood anything, phone would have got cut.” | |||

| Stigma[11] | Mr S (Patient 12): “I fear that I should not get humiliated in front of family members. I hide from family members while the call. I tell them some lie like ‘it’s a call from my office’.” Mr A (Patient 11): “at home there is no problem as everybody knows about my drug issue, but outside no one knows. I feel ashamed.” Mr B (Patient 2): “patients, according to me will continue his addiction (if they continue treatment through tele mode). If they come here their tests will be done and everything can be seen.” Mr. S (Patient 13): “Sir, if I always take treatment through phone, if I am doing anything wrong, you won’t be able to catch it.” | ||

| Satisfaction with teleconsultation | Privacy issues[12] | Perceived deficit of privacy[9] | Mr Y (Patient 15): (shared his feeling while discussing about his alcohol-related problems with his colleagues around) “One day I was with Dr. P. and colleagues so I felt hesitant to talk about this then I came outside in the park and then I talked about my problem. It was quite tough…. they once asked me to talk on a video call but I was busy with Dr. P. in the department, so I could not attend video call, fearing that others would be able to hear the doctor’s question and would know about my problems.” Mr S (Patient 12): “I benefited from it, but only when I was alone. When the Dr does a video call when I am home, my mother comes and stands beside me, wife comes and stands beside me, father comes and stands behind me. So, I can’t share my feelings with the Dr.” |

| Privacy is not of concern[5] | Mrs N (Patient 9): “my problem is not so confidential, I can tell, husband used to be with me during my teleconsultation, he also accompanies me to the OPD.” Mr S (Patient 14): “I am rarely with family members during tele-consultation, as they usually are away for their job. Even if I am sitting with other family members, its not a problem, because they know about my problems.” | ||

| Control and autonomy | Incongruence of goal between patient and doctor[1] | Mr S (Patient 5): told “via teleconsultation the doctors sometimes give me very high dose medicines to make me feel sleepy. Even after having that medicine through teleconsultation, I could not sleep and I kept feeling that I should have at least one ‘peg’. And one ‘peg’ would become two.” | |

| Loss of control[3] | Patient Mr C (Patient 4): “in teleconsultation, the doctor jumps in to the questions or just ask about the problem, and I as the patient must answer those questions. I feel, even if I tell my problem, it won’t help to know why I drink. So, the session should start with a friendly talk.” | ||

| Enhanced autonomy[2] | Mr. S (Patient 13): “first day during teleconsultation, when you were saying about medication, I opposed you by saying that I didn’t want medicines, and you didn’t prescribe any, and I felt that my choice counts.” | ||

| Missing elaborate enquiry[3] | Mr S (Patient 13): “During in person consultation, I can openly tell what I want and they can ask me multiple questions, difficult/blunt questions (Like why did you drink? What was the reason?), that nobody else would have asked during teleconsultation.” | ||

| Missed ritual of in-person consultation[3] | Mr Y (Patient 15): “the patient always goes to the doctor after being mentally prepared from home because he knows about this whole process, and he also expects doctor to follow a set of actions like asking, examining, prescribing and explaining the prescriptions etc., but this is lacking in TAC.” Mr G (Patient 5): “Every patient has been to atleast 10 doctors before coming here. Hence they know how to share problems and how can they get solution to their problems. The more detailed the sharing, more effectively can the doctor give medicines and treat them. Its more easy and there is more confidence.” | ||

| Therapeutic relationship during TAC | Therapeutic engagement and commitment[4] | Mrs N (Patient 8): “I can communicate well in most of the times. I mean, I never feel I am not in OPD. Last time, when drsaab called back again, he just forgot to prescribe medicine, then I messaged, so he himself called back, and told me to take the medicine he had changed. So I feel teleconsultation is fine, and I am satisfied.” Mr S (Patient 12): “Dr called and asked me, ‘how are you Sandeep?’ I said ‘I am fine’, but I was sitting and drinking. He asked ‘are you doing any work right now? What are you taking?’ I said ‘I am not taking anything, I am just taking the medicine you prescribed’. The Dr said, ‘Okay, send your patient card.’ I sent the card, he wrote meds and took them. So it doesn’t seem to be working for me.” | |

| Collaboration: Dr. Pt. trust[2] | Mr. G (Patient 5): “in consultation over phone, we are talking to the person for the first time, we don’t know the person on the other side. Also, we have to speak about the substances which are illegal. So there is ‘trust issue’.” |

TAC=telemedicine-based addiction care

Post-consultation phase

After obtaining TAC, the third and final phases can be conceptualized as “post-consultation.” In this phase, the patient evaluates the program. The main themes identified in this phase are advantages and disadvantages, perceived appropriateness of TAC, and outcome retention. The advantage is easy communication, whereas disadvantages include difficulty in the physical examination and urine screening, misplaced calls, and medication-related difficulties. The patients stressed punctuality, prior intimation, and proactive contact to improve outcomes and retention in TAC. For further details, see Table 4.

Table 4.

Themes, subthemes, and codes with relevant excerpts from post-consultation phase

| Theme | Subtheme | Code | Verbatim |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage and disadvantage | Ease of communication[10] | Easy vs difficult communication[3] | Mr. S (Patient 13): “many things cannot be said openly in front of the wife. Also, there is no hesitation while talking through phone, but it is there in other way. Sometimes I hesitate to speak in front, and think, no, what am I doing?, but there is a difference in communicating through phone.” Mr. A (Patient 11): “On call, one cannot tell you that he’s facing so and so problems because of the medicines. I get very irritated on smallest of things and then I start getting angry if someone teases me but I often face difficulty in telling these on telephone.” |

| Difficulty in detailed conversation[9] | Mr S (Patient 12): “In video care, the doctors ask us for the OPD card (photo) and then they ask what new problems we are facing and prescribe medicines. Hence, we can’t talk to the doctor much and may be they don’t have so much time that they can talk to us, But in OPD, the first question the Dr asks is, ‘Yes Sandeep, how are you?’. They ask everything, ‘What was the problem, why did it occur, what was the reason behind it?’ I mean, they ask every small detail.” Mrs N (Patient 8): “I communicate very well. All the doctors listen and respond me nicely. Once when I forget to take medicine, I requested him and he responded that ‘take these these medicines.’ So I didn’t see any difference even I am in house or in hospital” | ||

| Physical examination and urine screen[4] | Mr C (Patient 3): “if I come then it would be easy to get check-up, to show test reports, urine screen if necessary etc. This can not be done on phone, you can tell about medicine only.” Mr P (Patient 9): “by looking at you doctor can understand 50% of your problems like tremors in hands. He asks questions then. On phone, he can miss also.” | ||

| Patient is busy during consultation[8] | Mr. G (Patient 6): “Now we came, we know doctor has time and we too, but for phone we do not know at what time we will get the call. We may be busy, we may have less time,.…. phone comes suddenly, person may be at his relatives, or somewhere else, or one can be busy somewhere, that makes it difficult to talk.” Mr Y (Patient 15): “They call us but they do it according to that when they feel comfortable, then at that time we have some other work… half of our attention is in work and half on call, so we are not able to share our whole problem. Like now you are sitting physically, you can share everything.” | ||

| Medication-related issues in TAC[2] | Non-availability of some medications[2] | Mr. G (Patient 5): “They said that some medicines can be provided only through in-person consultation; it is not possible to provide them on phone.….Kindly prescribe better medicines on phone, like buprenorphine, which I am getting here.” Mr. A (Patient 13): “like Arkamine, Ketorolac etc., provided by you all to manage withdrawal. You can’t prescribe any better medicine for heroin withdrawal through teleconsultation. Initially, it is difficult to take it as sometimes one consumes drugs with that medicine.” | |

| Difficulty in procuring medications[2] | Mr. B (Patient 2): “With telephonic prescription I often had difficulty to buy medicine from the shop, and continue it. The medicine shop asked for the proper prescription (hard copy), and denied to give medicine from the photo. This increased my difficulty” | ||

| Perceived appropriateness | Suitability of TAC | Suitable[8] | Mr. A (Patient 1): “Sir, if my condition is better, then I would prefer telephonic consultation. But, if the condition is worse, then would come to OPD.” Another patient Mr. S (Patient 14) felt “if I have to go to work, or when I don’t have much time to come to OPD, then I would prefer teleconsultation” |

| Not suitable[9] | Mr. S (Patient 13): “If the medicines suits, then it is ok to get advice over the telephone sir. But, if it doesn’t suit, then I will consult you in-person and tell my problems.” Mr S (Patient 14) further expanded this idea: “If it seems a very emergency condition, then I would go there., by ‘emergency’, he meant ‘severe relapse, severe withdrawal symptoms, seizure, etc., or if there is significant family issues.” Mrs P (Patient 10): “if we want to talk very personally, even without family, then it would be better to come to PGI.” | ||

| Outcome retention | Improved outcome retention[5] | Mr. P (Patient 9): “Medication was not missed, did not drink again. There is no break in treatment, illness did not come back. In lockdown, everything was closed, would not get medicine otherwise, so telephonic treatment was helpful” | |

| Ensure punctuality[4] | Mr. Y (Patient 15): “there should be a separate time slot for teleconsultation for each patient, that at such a time one will get the call and the call should come at the pre-fixed time and patient should get suitable time for consultation.” | ||

| Prior intimation[3] | Mr. C (Patient 4): “intimate the session by text or phone call, so that the person would be free by that time, and can prepare and memorize what needs to be discussed in the session.” | ||

| Proactive contact[2] | Mrs P (Patient 10): “please contact and treat your patients who are not coming regularly for treatment, or those who haven’t come for the last six months through teleconsultation mode.” |

TAC=Telemedicine-based addiction care

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this could be the first study to understand service users’ perceptions and attitudes toward telemedicine-based SUD treatment from the global south. We used the content analysis to generate a thematic map from the emerging data rather than relying on the existing reports and to accommodate novel and unique perspectives from a different culture and context.[21] We took an inclusive approach in sample selection, comprising various SUDs with or without psychiatric and physical comorbidities and reasonable urban–rural representation. We also included those who utilized both in-person and telemedicine services. Hence, they must be in a better position to compare the two treatment modalities. Previous studies focused on predominantly white persons with OUD and included those who took either in-person or telemedicine consultations.[19,33-36] The diversity of our study sample improved the transferability of our results. We clearly described the conduct, procedural decisions, and details of data generation and management and adhered to the COREQ standard. We believe it increased the trustworthiness of our research.[37] To improve credibility and consistency, all IDIs were coded by two independent coders with experience in qualitative research and clinical experience in dealing with patients with SUD and telehealth care. The inter-rater agreement was strong; nevertheless, the discrepancies in interpretation were resolved by discussion with a senior researcher.[38]

Our study participants generally expressed a positive attitude toward telemedicine-based SUD treatment because of its flexibility, affordability, and convenience. The limited availability of SUD treatment services means patients must travel long distances and wait for formal in-person consultations. Telemedicine could improve the availability and access to SUD treatment. These findings are similar to the experiential accounts of service users and providers from high-income countries.[19,39] However, privacy concerns arising from the limited availability of mobile phones, Internet access, technical expertise, and private space to engage in teleconsultation could be unique to a low-resource setting. Moreover, the involvement of the family members in accessing telehealth services and during the teleconsultation process is indicative of collectivist eastern societies that encourage interdependence and emphasize family integrity, family loyalty, and family unity.[40] Nevertheless, some of our participants found the family “over-involvement” interfering with their autonomy to make choices and privacy during telehealth care. Some participants found in-person care more holistic and thorough, with a greater opportunity to discuss their goals and choices, and perceived greater control and autonomy. These findings, too, are somewhat similar to studies from the global north.[19] Finally, there was a gender dichotomy in the perception of control and autonomy during telemedicine vis-à-vis in-person treatment. While both women participants perceived greater control during telemedicine, the perception was generally different from men. We believe the lack of gender-sensitive SUD treatment facilities, the high stigma associated with female substance use, and the dependence of women on male family members for in-person consultations could have been responsible for a more positive perception of teleconsultation.[41]

Our study has several practice and policy implications. Awareness and access to telemedicine services must be extended. Using low-tech services, such as telephonic consultations, and having multiple telephone lines to minimize the waiting period might reduce the barrier to accessing telehealth services. While teleconsulting, the service provider must take a shared decision-making (SDM) approach to increase the involvement of the service users in the decision-making process and give them control and autonomy. SDM might have an additive effect on SUD treatment outcomes;[42,43] more importantly, it might improve the quality of therapeutic contact and patients’ satisfaction with telemedicine. The concerns regarding privacy and confidentiality must be respected. Family engagement seems useful in the telemedicine-based support and care of patients with SUD; however, family involvement must not interfere with patients’ privacy and autonomy. Stigma is an essential barrier to using telemedicine for SUD treatment. Reducing the structural and public stigma would require a policy-level intervention, whereas self-stigma is to be addressed at the individual and family levels.[27] Our study participants perceived telemedicine was more useful for continuing care but less suitable for those who required acute treatment. The perception has been reflected in the national telemedicine practice guidelines as well.[44] However, the restriction imposed on prescribing psychotropic medications by the practice guidelines was perceived as a major barrier to telehealth care for SUDs. Several countries in the global north have eased restrictions on the availability of psychotropic medications over telemedicine. Initial reports suggest increased access to telemedicine-based SUD treatment and no difference in treatment retention or drug use vis-a-vis standard in-person care.[45-47] Whether or not this ease of restrictions continues beyond the pandemic remains to be seen; however, low–middle-income countries such as India, which already suffer from an enormous treatment gap, may benefit from easing the telemedicine restrictions on psychotropics, even temporarily.[48] Proactive reminders and adherence to the prescheduled tele-appointments might help improve treatment retention.

Teleconsultation can improve treatment access for patients from faraway places, but apparently, from the patients’ perspective, it will not replace in-person care. The attraction of in-person treatment lies not only in the prospect of detailed physical examination or ease of investigation but also in the ritual of a visit to the doctor, which is as old as the healthcare system. Participation in the ritual of a visit to the doctor has some innate transformative effects, just like the other healing rituals.[49]

Despite the limitations, TAC could complement traditional in-person care. Our study highlighted the need for a right-based and client-centered TAC, supported by a facilitatory legal and policy framework to reduce the barriers to access and continue TAC.

Limitation

Our results might suffer from limited transferability because most of our participants were married and employed, suggesting better social stability. There is also an underrepresentation of older patients and women. There was no out-of-pocket expenditure or need for medical insurance to access treatment. These patient-level characteristics and financing might influence access to telehealth services.[50] The digital divide, or the paradox of telemedicine, being unable to penetrate and provide quality services to the poor and underserved, is a challenge that the global north is also grappling with.[51] Our study was from a publicly funded, specialized addiction treatment center that primarily serves patients with severe SUD. The study population had a mean duration of dependence of nearly ten years. Therefore, our findings might not apply to patients with milder SUDs. The data saturation principle followed in our study was vulnerable to outliers. Finally, we did not use respondent validation or any measures of data triangulation, which could have minimized researchers’ bias in interfering with or altering their perception of the data and its interpretation.[52]

CONCLUSION

Overall, the study participants found telemedicine to be an acceptable mode of service delivery for SUD; however, telemedicine services need to adapt to contextual factors, such as low technical expertise, poor Internet access, privacy concerns, cultural factors such as involvement of family members, and policy-level factors such as the restrictions on psychotropic prescription. Our study provides an in-depth insight into the barriers and facilitators of telemedicine-based SUD treatment access, use, and retention; it also helps to understand better the choices and preferences for telehealth care vis-à-vis standard in-person care for SUDs.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ambekar A, Agrawal A, Rao R, Mishra AK, Khandelwal SK, Chadda RK. Magnitude of substance use in India. New Delhi: Ministry of social justice and empowerment, Government of India; 2019. On behalf of the group of investigators for the national survey on extent and pattern of substance use in India; pp. 1–67. https://socialjustice.gov.in/writereaddata/UploadFile/Survey% 20Report636935330086452652.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vienna: United Nations publication, Sales No. E.21. XI.8; 2021. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World drug report 2021. Booklet 2: Global overview: drug demand drug supply. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arya S, Ghosh A, Mishra S, Swami MK, Prasad S, Somani A, et al. A multicentric survey among patients with substance use disorders during the COVID-19 lockdown in India. Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64:48–55. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_557_21. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_557_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Samson LW, Tarazi W, Turrini G, Sheingold S. Washington, DC: Office of the assistant secretary for planning and evaluation; 2021. Medicare beneficiaries’ use of telehealth in 2020: Trends by beneficiary characteristics and location; pp. 1–34. https://www.cms.gov/newsroom/fact-sheets/medicare-telemedicine-health-care-provider-fact-sheet. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ibrahim FA, Pahuja E, Dinakaran D, Manjunatha N, Kumar CN, Math SB. The future of telepsychiatry in India. Indian J Psychol Med. 2020;42(5 Suppl):112S–7S. doi: 10.1177/0253717620959255. doi: 10.1177/0253717620959255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ghosh A, Mahintamani T, BN S, Pillai RR, Mattoo SK, Basu D. Telemedicine-assisted stepwise approach of service delivery for substance use disorders in India. Asian J Psychiatr. 2021;58:102582. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2021.102582. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp. 2021.102582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romero ICF- M. Take part in the national substance use and mental health services survey. National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N SUMHSS) [[Last acessed on 2023 Mar 12]]. Available from: https://info.nsumhss.samhsa.gov/definitions.htm .

- 8.Molfenter T, Brown R, O’ Neill A, Kopetsky E, Toy A. Use of telemedicine in addiction treatment: Current practices and organizational implementation characteristics. Int J Telemed Appl 2018. 2018 doi: 10.1155/2018/3932643. 3932643. doi: 10.1155/2018/3932643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mark TL, Treiman K, Padwa H, Henretty K, Tzeng J, Gilbert M. Addiction treatment and telehealth: Review of efficacy and provider insights during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatr Serv. 2022;73:484–91. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.202100088. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps. 202100088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marsch LA, Guarino H, Acosta M, Aponte-Melendez Y, Cleland C, Grabinski M, et al. Web-based behavioral treatment for substance use disorders as a partial replacement of standard methadone maintenance treatment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2014;46:43–51. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2013.08.012. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat. 2013.08.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zekan M, Goldstein N. Substance use disorder treatment via telemedicine during coronavirus disease 2019. J Nurse Pract. 2021;17:549–51. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra.2021.01.018. doi: 10.1016/j.nurpra. 2021.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hustad JT, Barnett NP, Borsari B, Jackson KM. Web-based alcohol prevention for incoming college students: A randomized controlled trial. Addict Behav. 2010;35:183–9. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2009.10.012. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh. 2009.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vakkalanka JP, Lund BC, Ward MM, Arndt S, Field RW, Charlton M, et al. Telehealth utilization is associated with lower risk of discontinuation of buprenorphine: A retrospective cohort study of US veterans. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:1610–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06969-1. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-06969-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin LA, Fortney JC, Bohnert ASB, Coughlin LN, Zhang L, Piette JD. Comparing telemedicine to in-person buprenorphine treatment in U. S. veterans with opioid use disorder. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;133:108492. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108492. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat. 2021.108492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guinart D, Marcy P, Hauser M, Dwyer M, Kane JM. Patient attitudes toward telepsychiatry during the COVID-19 pandemic: A nationwide, multisite survey. JMIR Ment Health. 2020;7:e24761. doi: 10.2196/24761. doi: 10.2196/24761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sousa JL, Raja P, Huskamp HA, Mehrotra A, Busch AB, Barnett ML, et al. Perspectives of patients receiving telemedicine services for opioid use disorder treatment: A qualitative analysis of user experiences. J Addict Med. 2022;16:702–8. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001006. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000001006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh A, Mahintamani T, Sharma K, Singh GK, Pillai RR, Subodh BN, et al. The therapeutic relationships, empathy, and satisfaction in teleconsultation for substance use disorders: Better or worse than in-person consultation? Indian J Psychiatry. 2022;64:457–65. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_704_21. doi: 10.4103/indianjpsychiatry.indianjpsychiatry_704_21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Malhotra S, Chakrabarti S, Shah R. Telepsychiatry: Promise, potential, and challenges. Indian J Psychiatry. 2013;55:3–11. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105499. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.105499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lockard R, Priest KC, Gregg J, Buchheit BM. A qualitative study of patient experiences with telemedicine opioid use disorder treatment during COVID-19. Subst Abus. 2022;43:1150–7. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2022.2060447. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2022.2060447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mayring P. Qualitative content analysis. In: Flick U, von Kardoff E, Steinke I, editors. A companion to qualitative research. 1st Ed. London: SAGE; 2004. pp. 159–76. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:107–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x. doi: 10.1111/j. 1365-2648.2007.04569.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–57. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Coenen M, Stamm TA, Stucki G, Cieza A. Individual interviews and focus groups in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A comparison of two qualitative methods. Qual Life Res. 2012;21:359–70. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9943-2. doi: 10.1007/s11136-011-9943-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gulliford M, Figueroa-Munoz J, Morgan M, Hughes D, Gibson B, Beech R, et al. What does ’ access to health care’ mean? J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002;7:186–8. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082517. doi: 10.1258/135581902760082517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Carrillo JE, Carrillo VA, Perez HR, Salas-Lopez D, Natale-Pereira A, Byron AT. Defining and targeting health care access barriers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011;22:562–75. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2011.0037. doi: 10.1353/hpu. 2011.0037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Caplan G. 1st Ed. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1970. The theory and practice of mental health consultation. [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Ending discrimination against people with mental and substance use disorders: The evidence for stigma change. National Academies Press; 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan DG, Kosteniuk J, Stewart N, O’ Connell ME, Karunanayake C, Beever R. The telehealth satisfaction scale: Reliability, validity, and satisfaction with telehealth in a rural memory clinic population. Telemed J E Health. 2014;20:997–1003. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2014.0002. doi: 10.1089/tmj. 2014.0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Siegel M. Privacy, ethics, and confidentiality. Prof Psychol. 1979;10:249–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Appelbaum PS. Privacy in psychiatric treatment: Threats and responses. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1809–18. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.11.1809. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp. 159.11.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ardito RB, Rabellino D. Therapeutic alliance and outcome of psychotherapy: Historical excursus, measurements, and prospects for research. Front Psychol. 2011;2:270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00270. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg. 2011.00270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Costanzo C, Verghese A. The physical examination as ritual: Social sciences and embodiment in the context of the physical examination. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102:425–31. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna.2017.12.004. doi: 10.1016/j.mcna. 2017.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mattocks KM, Moore DT, Wischik DL, Lazar CM, Rosen MI. Understanding opportunities and challenges with telemedicine-delivered buprenorphine during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2022;139:108777. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2022.108777. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat. 2022.108777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uscher-Pines L, Sousa J, Raja P, Mehrotra A, Barnett M, Huskamp HA. Treatment of opioid use disorder during COVID-19: Experiences of clinicians transitioning to telemedicine. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2020;118:108124. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108124. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat. 2020.108124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bosse JD, Hoffman K, Wiest K, Todd Korthuis P, Petluri R, Pertl K, et al. Patient evaluation of a smartphone application for telehealth care of opioid use disorder. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2022;17:50. doi: 10.1186/s13722-022-00331-4. doi: 10.1186/s13722-022-00331-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cole TO, Robinson D, Kelley-Freeman A, Gandhi D, Greenblatt AD, Weintraub E, et al. Patient satisfaction with medications for opioid use disorder treatment via telemedicine: Brief literature review and development of a new assessment. Front Public Health. 2020;8:557275. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.557275. doi: 10.3389/fpubh. 2020.557275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kitto SC, Chesters J, Grbich C. Quality in qualitative research. Med J Aust. 2008;188:243–6. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2008.tb01595.x. doi: 10.5694/j. 1326-5377.2008.tb01595.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hammarberg K, Kirkman M, de Lacey S. Qualitative research methods: When to use them and how to judge them. Hum Reprod. 2016;31:498–501. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev334. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Aronowitz SV, Engel-Rebitzer E, Dolan A, Oyekanmi K, Mandell D, Meisel Z, et al. Telehealth for opioid use disorder treatment in low-barrier clinic settings: An exploration of clinician and staff perspectives. Harm Reduct J. 2021;18:119. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00572-7. doi: 10.1186/s12954-021-00572-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Avasthi A. Preserve and strengthen family to promote mental health. Indian J Psychiatry. 2010;52:113–26. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64582. doi: 10.4103/0019-5545.64582. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tripathi R. Women substance use in India: An important but often overlooked aspect. Eur Psychiatry. 2021;64(S1):S818–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Joosten EA, de Jong CA, de Weert-van Oene GH, Sensky T, van der Staak CP. Shared decision-making reduces drug use and psychiatric severity in substance-dependent patients. Psychother Psychosom. 2009;78:245–53. doi: 10.1159/000219524. doi: 10.1159/000219524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Friedrichs A, Spies M, Härter M, Buchholz A. Patient preferences and shared decision making in the treatment of substance use disorders: A systematic review of the literature. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0145817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0145817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone. 0145817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Telemedicine practice guidelines. Ministry of health and family welfare: New Delhi. 2020. [[Last accessed on 2023 Jan 14]]. Available from: https://www.mohfw.gov.in/pdf/Telemedicine.pdf .

- 45.Chan B, Bougatsos C, Priest KC, McCarty D, Grusing S, Chou R. Opioid treatment programs, telemedicine and COVID-19: A scoping review. Subst Abus. 2022;43:539–46. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1967836. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2021.1967836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Samuels EA, Khatri UG, Snyder H, Wightman RS, Tofighi B, Krawczyk N. Buprenorphine telehealth treatment initiation and follow-up during COVID-19. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37:1331–3. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07249-8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07249-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang L, Weiss J, Ryan EB, Waldman J, Rubin S, Griffin JL. Telemedicine increases access to buprenorphine initiation during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2021;124:108272. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.108272. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat. 2020.108272. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ghosh A, Singh S, Dutta A. Opioid agonist treatment during SARS-CoV2 and extended lockdown: Adaptations and challenges in the Indian context. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;53:102377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102377. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp. 2020.102377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Verghese A, Brady E, Kapur CC, Horwitz RI. The bedside evaluation: Ritual and reason. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:550–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00013. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Eberly LA, Kallan MJ, Julien HM, Haynes N, Khatana SAM, Nathan AS, et al. Patient Characteristics Associated With Telemedicine Access for Primary and Specialty Ambulatory Care During the COVID-19 Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2031640. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.31640. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen. 2020.31640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yee V, Bajaj SS, Stanford FC. Paradox of telemedicine: Building or neglecting trust and equity. Lancet Digit Health. 2022;4:e480–1. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00100-5. doi: 10.1016/S2589-7500(22)00100-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Anderson C. Presenting and evaluating qualitative research. Am J Pharm Educ. 2010;74:141. doi: 10.5688/aj7408141. doi: 10.5688/aj7408141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]