Abstract

Rare, biallelic loss-of-function mutations in DOCK8 result in a combined immune deficiency characterized by severe and recurrent cutaneous infections, eczema, allergies, and susceptibility to malignancy, as well as impaired humoral and cellular immunity and hyper-IgE. The advent of next-generation sequencing technologies has enabled the rapid molecular diagnosis of rare monogenic diseases, including inborn errors of immunity. These advances have resulted in implementation of gene-guided treatments, such as hematopoietic stem cell transplant for DOCK8 deficiency. However, putative disease-causing variants revealed by next-generation sequencing need rigorous validation to demonstrate pathogenicity. Here, we report the eventual diagnosis of DOCK8 deficiency in a consanguineous family due to a novel homozygous intronic deletion variant that caused aberrant exon splicing and subsequent loss-of expression of DOCK8 protein. Remarkably, the causative variant was not initially detected by clinical whole genome sequencing, but was subsequently identified and validated by combining advanced genomic analysis, RNA-Seq and flow cytometry. This case highlights the need to adopt multi-pronged confirmatory approaches to definitively solve complex genetic cases that result from variants outside protein-coding exons and conventional splice sites.

Keywords: DOCK8 deficiency, whole genome sequencing, intronic variant, RNA sequencing, flow cytometry

Introduction

Dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) is a guanine nucleotide exchange factor that regulates actin polymerization, cytoskeletal rearrangements and immunological synapse formation to induce activation, proliferation, differentiation, migration and survival of immune cells [1, 2]. Its fundamental role in immunity and host defense was established following the identification of individuals with a combined immunodeficiency resulting from bi-allelic inactivating mutations in DOCK8 [3, 4]. Pathogenic mutations include large deletions across DOCK8, or nonsense or missense variants in exons or splice sites that introduce premature stop codons, aberrant splicing and/or protein instability, and subsequent loss-of expression of DOCK8 protein [3–8]. Clinical manifestations of DOCK8 deficiency include severe, recurrent and life-threatening sinopulmonary and mucocutaneous viral (molluscum contagiosum virus, HSV, HPV), bacterial (Staphylococcus aureus) and fungal (Candida albicans) infections. Patients also develop hyper-eosinophilia, severe atopic dermatitis/eczema, extremely elevated levels of serum IgE (103-105 IU/mL; normal range 0–100 IU/mL), food allergies, and increased susceptibility to malignancy [3–8]. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) remains the standard of care for DOCK8-deficient individuals [7, 9–12]. Currently, >200 DOCK8-deficient patients have been reported globally.

Because of the dire prognosis for untreated DOCK8-deficient patients, it is crucial to identify affected individuals early so treatment options can be implemented prior to onset of severe infections and irreversible tissue damage [5]. Identification of pathogenic variants is also important for genetic testing of potentially affected siblings, carrier screening and reproductive planning [13]. Here, we present a consanguineous family where the index case exhibited clinical manifestations consistent with DOCK8 deficiency. However, initial extensive genetic analyses failed to identify a causative variant in any exons with the DOCK8 gene. Using multiple approaches, we finally identified a novel intronic homozygous deletion upstream of exon 38 of DOCK8. This enabled definitive genetic diagnosis of DOCK8 deficiency in the index case, as well as diagnosing a clinically-mild homozygous sibling who subsequently presented with severe disease, and rapid genetic screening of two siblings born after diagnosis of the index case. This case is a salient example of the need to adopt a multi-omics approach to identify, functionally validate and classify candidate intronic and exonic variants as pathogenic to enable the definitive molecular diagnosis of inborn errors of immunity.

Materials and Methods

Human subjects

PBMCs were isolated from healthy donors (Australian Red Cross), patients as well as their siblings and parents. This study was approved by the Sydney Local Health District RPAH Zone Human Research Ethics Committee and Research Governance Office, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, NSW, Australia (Protocol X16–0210/LNR/16/RPAH/257); the South Eastern Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee, Prince of Wales/Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, NSW, Australia (Protocol HREC/11/POWH/152) and the NIAID (Protocol 06-I-0015). Written informed consent was obtained from participants or their guardians.

Flow cytometry

• Immune cell phenotyping and function

To investigate CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations, PBMCs were incubated with mAbs against CD4, CD8, CCR7, CD45RA, CD28, CD57, CD95 and CD127. Naïve (CCR7+CD45RA+), central memory (TCM; CCR7+CD45RA−), effector memory (TEM; CCR7−CD45RA−) and CD45RA+ effector memory (TEMRA; CCR7−CD45RA+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cell subsets were then identified and enumerated. To investigate T cell exhaustion, expression of CD28, CD57, CD95 and CD127 was determined on naïve, TCM, and TEMRA CD8+ T cell subsets [11, 14, 15]. B cell subsets were also assessed, as previously described [16].

• DOCK8 expression

Expression of DOCK8 in PBMCs from healthy donors and patients was determined by flow cytometry, as previously described [17]. Briefly, PBMCs were fixed with formaldehyde and stained with an unconjugated a mouse anti-DOCK8 Ab or an isotype control mouse IgG1 mAb, followed by a secondary PE conjugated rat anti-mouse IgG1. Saponin was used as the permeablizing agent. Lymphocyte and monocyte populations were established based on FSC and SSC FACs profiles and DOCK8 expression then investigated in these leukocyte populations [11, 14].

• Intracellular cytokine production

To investigate cytokine production, CD45RA− memory CD4+ T cells were isolated from healthy donors and patients by cell sorting and then cultured with T cell activation and expansion (TAE) beads (Miltenyi Biotech) at a cell: bead ratio of 2:1. After 5 days of culture, cells were restimulated with PMA (100ng/ml) and ionomycin (750 ng/ml) for 6 hours with brefeldin A (10 μg/ml) added after 2 hours. Cells were fixed and stained intracellularly for IFNγ (B27) and IL-4 (8D4–8) expression using 0.5% saponin as the permeabilizing agent. Expression of these cytokines was then determined by flow cytometric analysis [11, 18].

Genome sequencing

Whole genome sequencing was performed by the Kinghorn Centre for Clinical Genomics Sequencing Laboratory, which was clinically accredited to ISO 15189 by the National Association of Testing Authorities, Australia (NATA, www.nata.com.au). Genomes were sequenced on a HiSeq X platform (Illumina) using TruSeq Nano DNA Library Preparation kit and Illumina 150bp paired-end sequencing to a mean coverage of ≥30X, with 97.7% of canonical protein coding transcripts and splice sites (± 8 intronic nucleotides) covered at ≥15X (historical median). Paired-end reads were initially aligned to the human genome reference sequence (GRCh37) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA-MEM), and variant calls made using the Genomic Analysis Tool Kit (GATK). Over the reportable range (protein coding exons, exon-intron boundaries ±8 nucleotides, and untranslated regions), sensitivity was >99% for single nucleotide variants and >95% for small indels <20bp, with this analytical validity established using the variant location relative to GiaB v2.19 NA12878 Certified Reference Material. The reportable range of coverage for clinical genetic testing was based on the “Australian Pathology Accreditation Advisory Council Requirements for Human Medical Genome Testing Utilising Massively Parallel Sequencing Technologies” (https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/npaac-pub-mps), and guidelines published by the European Society of Human Genetics [19].

Sanger sequencing

PCR amplification and Sanger sequencing of DOCK8 exons, with their immediately adjacent intronic or untranslated regions, was performed using genomic DNA from patient’s PBMC, as described [3]. To determine segregation of the candidate deletion variant in DOCK8, Sanger sequencing was performed by Garvan Molecular Genetics, which is also accredited by NATA to ISO/IEC 15189, using genomic DNA isolated from PBMCs from various family members using the following primers: DOCK8_F tgtaaaacgacggccagtGTTTTCTTCTGTCTCGTTTTCTG; DOCK8_R caggaaacagctatgaccCCTCCAGCATGCTCAGATAC

RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq)

PBMCs from I.2 (heterozygous carrier) and three healthy donors were stimulated in vitro with PMA/Ionomycin for 16 hrs; mRNA was then purified using a RNeasy kit (Qiagen). cDNA libraries were prepared using a TruSeq stranded mRNA library preparation kit (Illumina), and sequencing was carried out on a NextSeq platform (Illumina) to obtain 150 bp paired-end reads. RNA-seq data are publicly available from the Sequence Read Archive (SRA; GEO). Read ends were trimmed with Trimmomatic (v0.39) using a sliding window quality filter [20]. Trimmed reads were mapped to the human reference genome (GRCh38) using HISAT2 (v2.2.1) [21], and the GENCODE release v38 of the human genome was used to annotate genes [22]. Splicing of DOCK8 was explored manually using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV; v2.9.2) [23]. The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database isoform 3 (NM_001193536.1) was used as the reference transcript for DOCK8 exon coordinates in this study, as it was the major isoform in our PBMC samples, consistent with previous studies in T cells [6]. Protein domain diagrams were generated using the drawProteins R package [24]. The DOCK8 protein structure prediction from AlphaFold [25] was visualized using PyMOL software (v. 2.3.2, Schrodinger).

Results

A novel case of hyper-IgE syndrome

The index case, a male, was the first-born child to consanguineous parents of Afghan origin (II.1, Figure 1A). When he presented in 2013 (age 3.5 years) for immunological assessment, he had a clinical history of multiple food allergies, severe eczema, recurrent skin abscesses, and chest and ear infections. On examination he had severe failure to thrive (weight 9.8kg, <<3rd centile; height 95cm, 5–10th centile), significant respiratory distress with widespread coarse crepitations, hepatosplenomegaly, chronic lichenified skin with multiple areas of inflammation, vesicles on his face, alopecia and ulceration of his scalp, dystrophic nails and clubbing. A CT scan confirmed bronchiectasis. Baseline investigations showed microcytic hypochromic anemia, thrombocytosis, hypereosinophilia, elevated ESR and CRP, low serum IgM but increased IgA and IgG, and extremely high IgE (17300 kU/mL). He had CD4+ T cell lymphopenia (0.35×109/L); however, CD8+ T cells, B cells and NK cells were within reference ranges of aged-matched healthy controls. Other relevant clinical features included a history of recurrent bacterial (Streptococcus pyogenes, Hemophilus influenzae), fungal (Candida, Aspergillus), and cutaneous (HSV, VZV) and non-cutaneous (chronic active EBV with viraemia, CMV, HHV6, norovirus, adenovirus) viral infections.

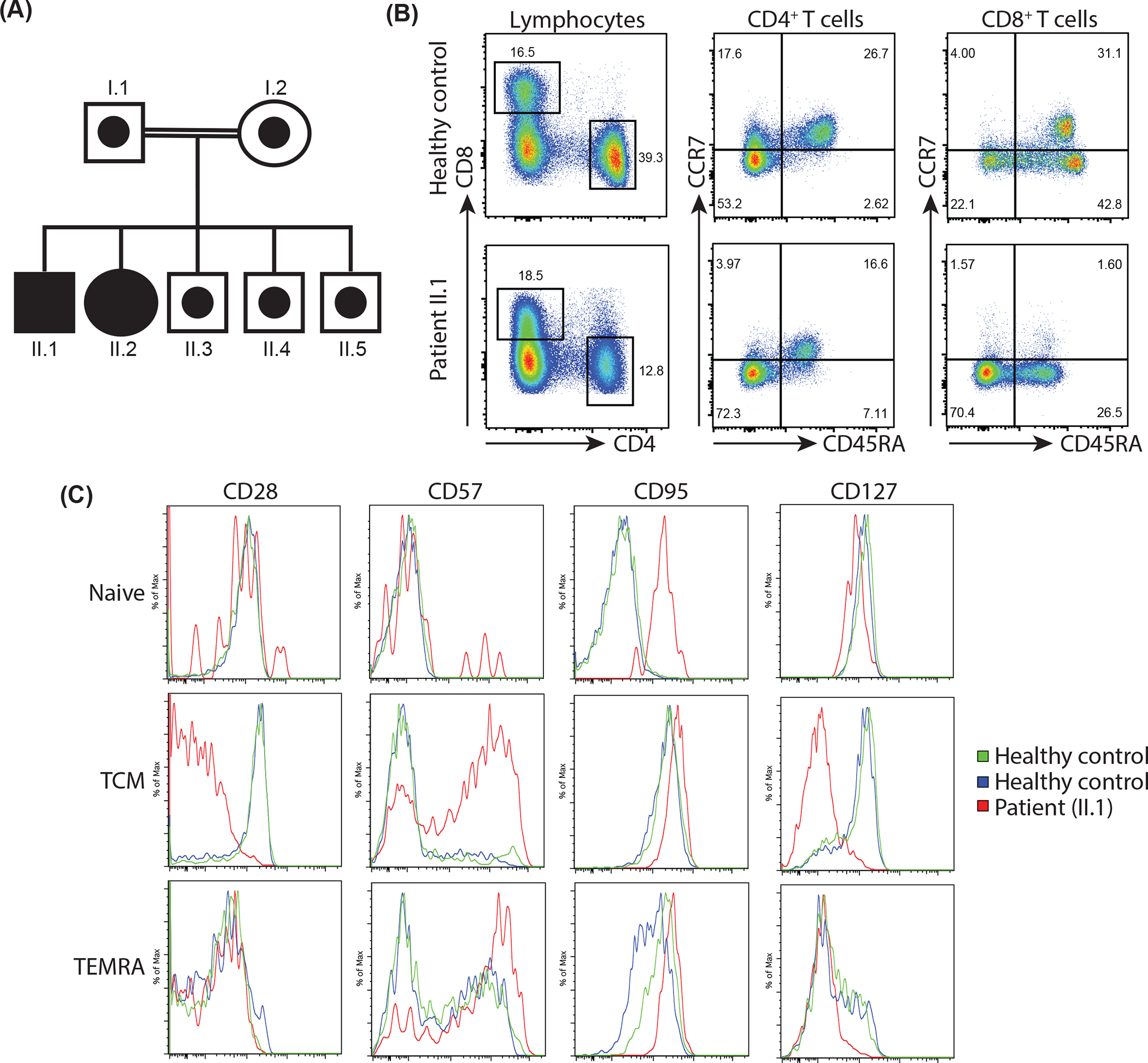

Figure 1: T cell exhaustion and DOCK8 deficiency in a novel kindred with hyper-IgE syndrome.

(A) Pedigree showing segregation of mutant DOCK8 in a consanguineous family. Solid symbols represent homozygous individuals and open symbols with circle in the centre represent heterozygous carriers.

(B, C) PBMCs from healthy controls and patient II.1 were labelled with mAbs against CD4, CD8, CCR7, CD45RA, CD28, CD57, CD95 and CD127. (B) Proportions of naïve (CCR7+CD45RA+), TCM, (CCR7+CD45RA−), TEM (CCR7−CD45RA−) and TEMRA (CCR7−CD45RA+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations in a representative healthy control (top panel) and patient II.1 (bottom panel). (C) Expression of CD27, CD57, CD95 and CD127 on gated naïve, TCM, and TEMRA CD8+ T cell subsets from healthy controls and patient II.1.

Patient II.1 underwent haploidentical HSCT in 2014 using mobilized peripheral blood stem cells from his father (I.1). He developed central venous line infections with Staphylococcus aureus and Corynebacterium urealyticum, had CMV reactivation and low level adenoviremia post-HSCT, necessitating infusion of allogeneic trivirus (CMV, EBV, adenovirus)-specific CTLs. Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease was managed by Rituximab. Although he ultimately had immune reconstitution with 100% donor cells and normal B cell number, he remained hypogammaglobulinemic, requiring ongoing immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Flow cytometric analysis confirms DOCK8 deficiency in II.1.

DOCK8 deficiency was suspected from the clinical presentation and consistent immunological investigations of II.1. Our previous flow cytometric-based analyses of inborn errors of immunity identified a unique “lymphocyte signature” for DOCK8-deficient patients typified by a reduced CD4/CD8 ratio, and enhanced/premature CD8+ T cell exhaustion/senescence [11, 15, 18, 26]. This phenotype has also been reported for individuals with bi-allelic pathogenic variants in RHOH [27] or STK4 [28], heterozygous deleterious mutations in CDC42 [29], or gain of function (GOF) heterozygous mutations in PIK3CD [30]. However, the intact frequency of transitional B cells and paucity of memory B cells differentiates DOCK8-deficiency from PIK3CD GOF and RHOH-deficiency [11, 16, 26, 27], elevated expression of CD95 on naïve CD8+ T cells distinguishes DOCK8-deficiency from STK4-deficiency [11, 15, 28], and absence of phenotypic features of CD8+ T cell exhaustion delineates DOCK8-deficiency from CDC42-deficiency [29]. Thus, to provide correlative support for a potential diagnosis of DOCK8 deficiency, we performed extensive flow cytometric analysis of PBMCs from II.1. Using this approach, his lymphocytes were found to exhibit features of this canonical DOCK8-associated immune cell phenotype, including reductions in the frequency of memory B cells (not shown) and CD4+ T cells, and a subsequent reduced CD4:CD8 ratio (Figure 1B) [11, 15, 18, 26]. While the distribution of CD45RA+CCR7+ naïve, CD45RA−CCR7+ TCM and CD45RA−CCR7− TEM CD4+ T cells in II.1 was similar to healthy controls (Figure 1B), his CD8+ T cells showed signs of accelerated differentiation in vivo, evidenced by a severe reduction in proportions of naïve and a dramatic accumulation of TEM and TEMRA cells compared to healthy controls (Figure 1B) [15, 18, 26]. Further analysis of CD8+ T cell from II.1 revealed signature features of exhaustion. Thus, all naïve CD8+ T cells expressed CD95, which is typically absent from naïve CD8+ T cells in healthy donors, and greater proportions of TCM and TEM cells from II.1 concomitantly expressed higher levels of the senescence/activation markers CD57 and CD95 and had downregulated CD28 and CD127 compared to these CD8+ T cell subsets in healthy controls (Figure 1C) [11, 15, 26].

Subsequently, a flow cytometric assay to detect DOCK8 protein became available [17, 31]. Analysis of PBMCs from healthy controls revealed abundant DOCK8 expression in lymphocytes and monocytes (Figure 2A). In contrast, DOCK8 was undetectable in monocytes and expressed at very low/negligible levels in lymphocytes from II.1 (Figure 2A). There was also no evidence of somatic reversion, which can result in expression of DOCK8 in some lymphocyte subsets [14, 31], in the patients’ leukocytes (Figure 2A). Surprisingly, while these cellular phenotypes were consistent with a diagnosis of DOCK8 deficiency, targeted sequencing of DOCK8, as well as other SCID/CID genes [32], failed to detect any candidate variants in protein-coding regions of these genes (not shown). Taken together, II.1 clinically, phenotypically and biochemically resembled DOCK8 deficiency, despite being unable to identify a genetic variant to provide a definitive diagnosis.

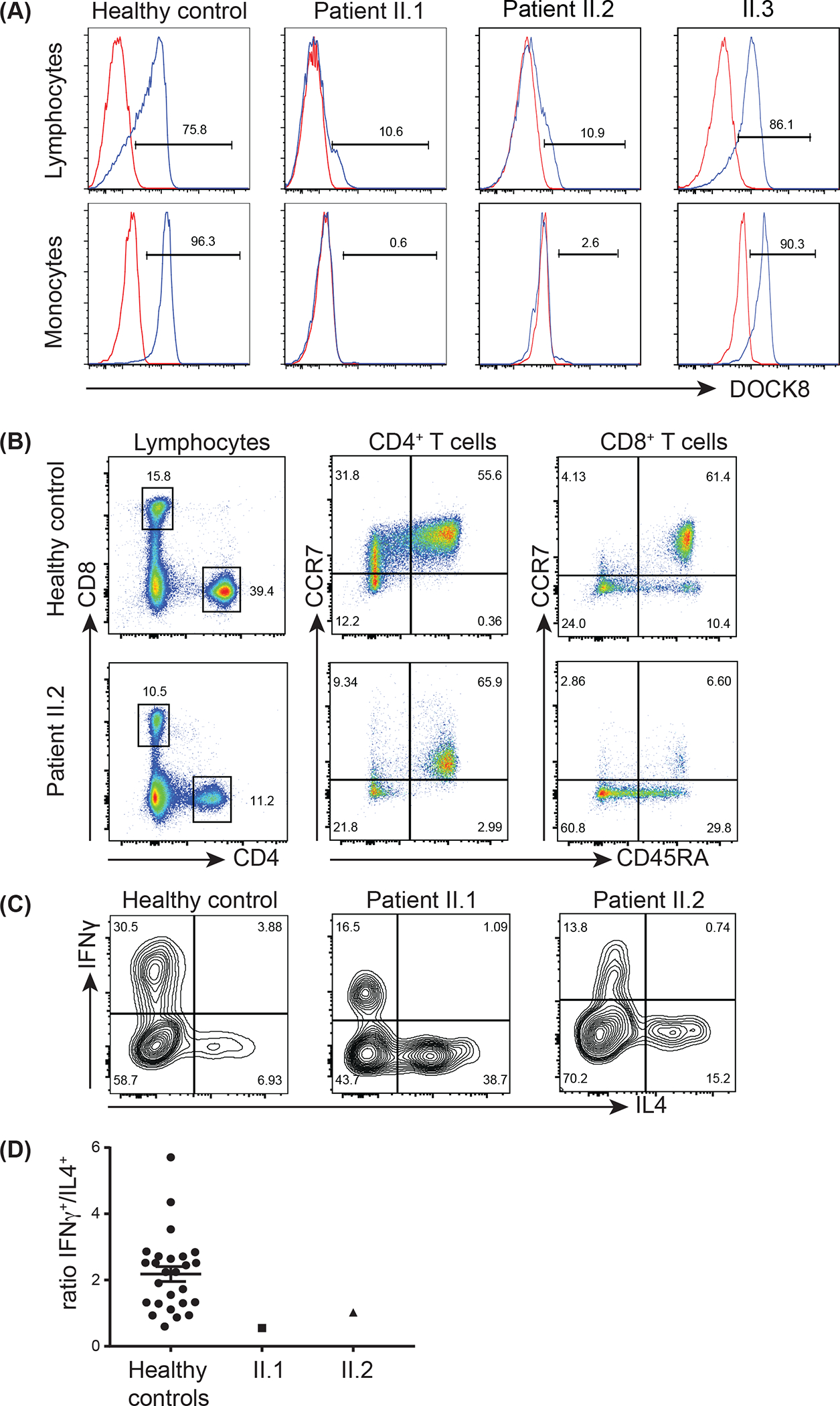

Figure 2: Lack of DOCK8 protein expression in patient leukocytes.

(A) PBMCs from healthy controls or family members II.1, II.2 and II.3 were fixed, permeabilised with saponin and then stained intracellularly with an Ab against DOCK8 (blue histogram) or an isotype control Ab (red histogram). DOCK8 expression was determined in lymphocyte and monocyte populations, as defined according to forward (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) profiles, in healthy controls II.1, II.2 and II.3.

(B) PBMCs from a healthy control and patient II.2 were labelled with mAbs against CD4, CD8, CCR7, and CD45RA. Proportions of naïve (CCR7+CD45RA+), TCM, (CCR7+CD45RA−), TEM (CCR7−CD45RA−) and TEMRA (CCR7−CD45RA+) CD4+ and CD8+ T cell populations.

(C-D) CD45RA− memory CD4+ T cells were isolated from healthy controls and patients II.1 and II.2 and activated in vitro. Intracellular expression of IFNγ and IL-4 was determined after 5 days, following restimulated with PMA/ionomycin. (C) representative FACs plots of IFNγ and IL-4 expression. (D) ratio of IFNγ+/IL-4+ cells.

Discovery of a second case of DOCK8 deficiency in this kindred

To extend investigations of this family, we assessed the parents (I.1, I.2) and younger siblings of II.1. Expression of DOCK8 in PBMCs from his younger brother II.3 was similar to that observed for healthy controls (Figure 2A). However, despite being informed that his younger sister II.2 was relatively healthy, her lymphocytes and monocytes also lacked DOCK8 expression (Figure 2A). Detailed clinical history at age 2.5 years revealed II.2 actually had experienced mild clinical features of DOCK8 deficiency, including eczema, food allergy, and corneal scarring suggesting HSV keratitis in early infancy. Consistent with these observations, T and B cells from II.2 exhibited the signature “DOCK8 phenotype” (Figure 2B, not shown) [11, 15, 26], suggesting she carried the same genetic defect as II.1 and was thus also clinically DOCK8-deficient. Notably, the CD4/CD8 ratio in II.2 was similar to healthy controls (Figure 2B), suggesting skewing of the T cell compartment to CD8+ T cells reflects disease progression rather than intrinsic DOCK8-deficiency.

In addition to a unique cellular phenotype [26], DOCK8-deficient lymphocytes exhibit characteristic functional defects, including skewing of their CD4+ T cells to the Th2 lineage and a reduction in Th1-type cells [11, 18]. To provide further evidence that these siblings had DOCK8-deficiency, we assessed cytokine expression by their memory CD4+ T cells following in vitro activation. Consistent with our previous findings, the frequencies of memory CD4+ T cells from II.1 and II.2 that expressed IFNγ were reduced while those expressing IL-4 were increased compared to memory CD4+ T cells from healthy donors (Figure 2C). The net effect of this was a reduction in the ratio of IFNγ+/IL-4+ memory CD4+ T cells in both siblings relative to healthy donors (Figure 2D), consistent with DOCK8-deficiency [11, 18].

Based on this, II.2 and her parents were counselled for HSCT, but this was declined because she was reasonably well at this stage. In 2014, II.2 (aged 4 years) developed further symptoms of DOCK8 deficiency, including recurrent lower bacterial respiratory tract infections, cutaneous HSV infection, chronic ear infections, severe food and environmental allergies, asthma, eczema and elevated serum IgE (8100 IU/ml). She commenced intravenous immunoglobulin replacement and underwent haploidentical HSCT using stem cells mobilised from her father (I.1) in 2020 (aged 10 years).

Identification and confirmation of a novel intronic pathogenic variant by combining whole genome sequencing and RNA sequencing

In 2016, through the Clinical Immunogenomic Research Consortium of Australasia (CIRCA) [33], II.1 and II.2 underwent clinical WGS with bioinformatic reduction and analysis to a virtual exome and analysis including the first and last 8 non-coding nucleotides of all introns. Surprisingly, but consistent with earlier targeted gene sequencing and despite all coding nucleotides being sequenced at >15 depth during WGS, no variants were detected in any of the 47 protein-coding exons of DOCK8 [6], nor in any other genes associated with inborn errors of immunity [32, 34].

We also considered the possibility of structural variants [35] (with deletions > 20 bp) affecting DOCK8, however none were detected. We then expanded our search to include all known Mendelian genes using broad search criteria based only on population allele frequency, in silico variant annotation criteria, and published gene-disorder relationships (www.omim.org). We identified and then evaluated in detail five homozygous variants (COL18A1, KRT4, GAA, MYO7A and TNXB), eight compound heterozygous variants (ASPM, COG5, COL6A3, RP1L1 and TTN), and 44 heterozygous variants without an accompanying trans allelic variant (ABCB11, ADAMTS18, ADCY10, ANKRD11, ARID1B, ASAH1, C1R, CAP2, CDH15, CHRNA3, CISH, COL6A3, CUBN, FAM20C, FRAS1, GJA5, GYS1, KLHL3, LDB3, LFNG, MCM9, MFAP5, MMP9, MYT1L, NDUFA9, NFKB2, NNT, NPR3, PIGT, PKD1L1, PKHD1, PSTPIP1, RP1L1, SERAC1, SOD2, SON, SPG20, TGM5, TMIE, TRPM4, TTN, UNG, VPS13C, WDPCP). All of these were considered for pathogenicity, but were rejected as either not meeting reportable candidate variant criteria, or not fitting the patient’s clinical presentation.

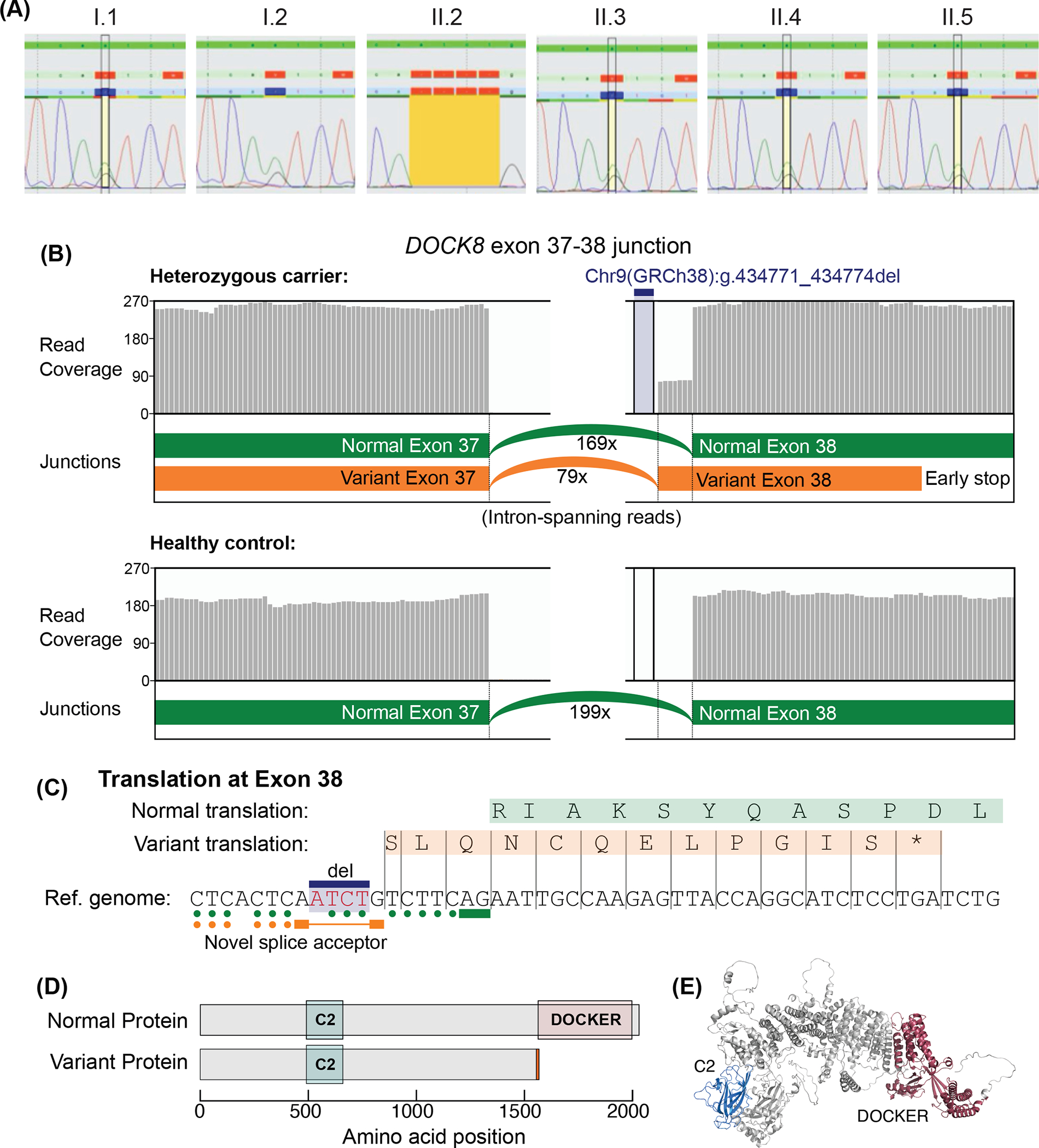

Expanding our search further to include all rare variants, coding and non-coding, across the DOCK8 locus subsequently revealed a novel homozygous 4 bp intronic deletion [Chr9(GRCh38): g.434771_434774del] located 9 bp upstream of exon 38 of DOCK8 in II.1 and II.2. This intronic variant was initially undetected as our clinical genomics interpretation pipeline only included 8 bp upstream and downstream of exons. Sanger sequencing demonstrated that both parents, the DOCK8-sufficient brother II.3 and another sibling born in 2018 (II.4) were all heterozygous for this variant, establishing complete segregation of the homozygous variant with the clinical phenotype (Figure 3A).

Figure 3: Sanger sequencing and RNA-sequencing confirmation of the deleterious intronic variant in DOCK8.

(A) Sanger sequencing performed on DNA extracted from PBMCs of the family members revealed that I.1, I.2, II.3 and II.4 were heterozygous carriers and II.2 was homozygous for the Chr9(GRCh38):g.434771_434774del mutant DOCK8 variant, confirming WGS data for II.1 and II.2. (B-D) RNA-sequencing was performed on PBMC from I.2 (heterozygous carrier) and three healthy controls (one representative healthy control is shown). (B) Differential splicing occurred in 32% of reads between exons 37–38 of DOCK8 in I.2 (heterozygous for a 4 bp intronic deletion upstream of exon 38). Grey bars show the mRNA read coverage mapped at each bp position. (C) Predicted aberrant splicing of the variant transcript at exon 38 results in a frameshift and introduces a premature termination codon after 12 amino acids of exon 38. Elements of the canonical splice site motif are indicated: solid bars underline the 3’ AG sequences immediately upstream of exons; dots indicate the polypyrimidine tract (C or T upstream of the splice-acceptor), which are reduced for the variant splice site. (D) Protein domains for DOCK8 (based on Uniprot: Q8NF50–3, corresponding to the NM_001193536.1 transcript). Predicted truncation of the variant protein retains the “C2 DOCK-type” domain but lacks the C-terminal “DOCKER” domain. A short sequence of 12 different amino acids is predicted on the C-terminal end of the variant protein (orange bar). (E) DOCK8 predicted structure from AlphaFold.

The gnomAD database lists only 4 single nucleotide substitutions between nucleotides −16 and −1 of exon 38 of DOCK8, suggesting this region is highly conserved and that the variant detected is likely deleterious in a homozygous state. Indeed, four in silico splicing prediction tools (SSF, MaxEnt, NNSPLICE, GeneSplicer) predicted degradation or loss of the nearby splicing acceptor site of intron 38 (or equivalently numbered) in all known transcripts. To explore whether the predicted loss of splicing occurred, RNA-seq was performed on PBMCs from the heterozygous mother I.2 (II.1 and II.2 had undergone HSCT). This led to the identification of a novel splice site forming 1 bp downstream of the deleted base pairs (Chr9(GRCh38):g.434771_434774del), between exons 37 and 38. This variant splice site affected 32% (79/248) of junction-spanning reads in PBMCs from I.2 (Figure 3B, C), but was undetected in PBMCs from healthy donors (n=3). The splice donor site downstream of exon 37 is preserved, but the deletion forms a novel splice-acceptor site 7 bp upstream of the normal exon 38, introducing a frameshift. The new splice-acceptor site would have one fewer pyrimidine nucleotides (at position −6 relative to the new acceptor site), which could affect splicing efficiency (Figure 3B) relative to the other (wild-type) allele [36, 37]. The variant exon 38 encodes 12 alternate amino acids followed by a premature termination codon (SLQNCQELPGIS*), whereas the normal exons 38–47 encode 471 amino acids including the DOCKER domain, which is required for interaction with the GTPase CDC42 and LRCH1, which regulates CDC42 function (Figure 3D, E) [38].

Another sibling (II.5) was born in Dec 2019. Our workup of this family over the preceding ~7 years allowed us to rapidly determine whether this child was affected by DOCK8 deficiency. Flow cytometry revealed that cord blood immune cells expressed normal levels of DOCK8 protein and targeted Sanger sequencing established that II.5 was a heterozygous carrier of the intronic variant (Figure 1A, 3A).

Discussion

The accessibility and affordability of NGS has seen an exponential discovery of genetic causes of human diseases. Indeed, when the first inherited monogenic defect causing immune dysregulation was reported in 2010, ~200 known inborn errors of immunity had been identified in the preceding ~40 years [34, 39]. In the following decade, >250 novel inborn errors of immunity have been reported, with almost all of them being discovered by NGS approaches [34, 39, 40]. Despite these major advances, a frequent outcome of NGS is uncertainty, with many cases yielding candidate genes or variants of unknown significance, but remaining undiagnosed [13, 41–43]. The outcomes of NGS can also be greatly influenced by advantages, disadvantages and limitations of the genetic sequencing platform (targeted gene panels, whole exome sequencing, WGS), as well as the analytical pipeline (clinical vs research) utilized [13, 39, 44].

In this study, we report the challenges in identifying a causative genetic variant by exon sequencing and clinical WGS in a kindred presenting with cardinal clinical, phenotypic and functional features of DOCK8 deficiency, including a complete absence of DOCK8 protein in the patients’ immune cells. The genetic lesion was eventually discovered by broadening the genomic analysis to include deeper intronic regions, combined with RNA-seq to confirm the in silico-predicted deleterious impact of an intronic deletion on splicing of DOCK8 exons and subsequent protein expression. With hindsight, discovery of the pathogenic variant could have been expedited if additional base pairs adjacent to exon boundaries had been considered in the genomic analysis pipeline. The anti-DOCK8 mAb used in our study was raised against amino acids 119–277 of human DOCK8 protein. This epitope would be translated from the RNA transcript encoded by the mutant DOCK8 allele. Thus, our finding of complete lack of DOCK8 protein in monocytes and near-complete lack of DOCK8 protein in lymphocytes from II.1 and II.2 suggests the pathogenic intronic variant is not only likely to alter exon splicing to introduce a premature stop codon potentially resulting in a truncated protein, but also probably disrupts stability of the entire DOCK8 protein. The premature stop codon likely triggers nonsense-mediated decay (NMD) of the aberrant transcript, particularly since this premature stop codon is located far from the next exon-exon junction (>55 bp distances support NMD targeting in mammals) [45]. NMD could also explain our observation that 32%, rather than 50%, of the variant splicing occurred in a heterozygous carrier, although experiments using puromycin to inhibit NMD would be one way to further test this explanation. Sequence analysis suggested the novel splice-acceptor site would override the canonical splice-acceptor site, which remains in cis on the variant allele, although our data does not necessarily preclude the possibility of canonical splice-acceptor usage on the variant allele.

Detection of this pathogenic homozygous DOCK8 variant in II.1 and II.2 provided a definitive molecular diagnosis of DOCK8 deficiency, thereby ending a long diagnostic journey for this family. This finding (1) supported the clinical decision to treat II.1 and II.2 with HSCT, the standard of care for DOCK8-deficiency [7, 9–12], (2) enabled rapid screening of a newborn child and established that both parents and the siblings II.3 and II.4 are heterozygous carriers, and (3) will facilitate additional genetic testing for future pregnancies.

Our investigations of this family highlight the importance of investigating intronic regions for deleterious variants, and that diagnostic outcomes from WGS can be enhanced by utilising bioinformatic analyses that consider potential variants affecting exon splicing lying further intronic to the usual end-points of analysis. Interestingly, recent studies reported the identification of deep intronic variants in STAT3 [46] or IKBKG (NEMO; [47]) as causative of autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome or X-linked recessive anhidrotic ectodermal dysplasia with immunodeficiency, respectively. To our knowledge, this is only the second example of an intronic variant in DOCK8 lying beyond the splicing boundaries that has been formally validated as being pathogenic [48]. Interestingly, this previous case bears similarities to our study, inasmuch that the variant was also located >8 bp upstream of a coding exon, and confirmation of the impact of the pathogenic insertion mutation was demonstrated by RNA-Seq and flow cytometry [48]. Thus, the incorporation of transcriptomics, proteomics and functional validation with WGS represents a powerful – and often necessary - approach to discover novel pathogenic variants and unequivocally diagnose complex and challenging cases of inborn errors of immunity.

Acknowledgements

We are extremely thankful to the patients and their family for participating in this study. We also thank Angela Wang (NIAID, NIH) for her regulatory assistance, the Clinical Trials & Biorepository Team, St Vincent’s Centre for Applied Medical Research (St Vincent’s Hospital, Darlinghurst, NSW Australia) for biobanking and Dr Karen Enthoven (CIRCA) for project co-ordination. Computational work was performed using the high-performance computing resources of the Garvan Institute of Medical Research. Sanger sequencing was performed by Garvan Molecular Genetics and flow cytometry by the Garvan Flow facility.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by the NHMRC of Australia (1060303), Office of Health and Medical Research of the NSW Government, the Jeffrey Modell Foundation, SPHERE Triple I Clinical Academic Group and UNSW Medicine Infection, Immunology and Inflammation Theme, the Ross Trust, and the John Brown Cook Foundation, and in part by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, NIH. S.G.T was a Principal Research Fellow (1042925) of the NHMRC, and is currently a recipient of an NHMRC Leadership 3 Investigator Grant (1176665) and NHMRC program grant (1113904). C.S.M is supported by an Early-Mid Career Research Fellowship from the Ministry of Health of the New South Wales Government of Australia.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

All authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Ethics Approval

This study was approved by the Sydney Local Health District RPAH Zone Human Research Ethics Committee and Research Governance Office, Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Camperdown, NSW, Australia (Protocol X16–0210/LNR/16/RPAH/257); the South East Sydney Local Health District Human Research Ethics Committee, Prince of Wales/Sydney Children’s Hospital, Randwick, NSW, Australia (Protocol HREC/11/POWH/152); and NIAID (Protocol 06-I-0015). Written informed consent was obtained from participants or their guardians.

Availability of data and materials

Available upon request to the corresponding authors.

References

- 1.Tangye SG, Bucciol G, Casas-Martin J, Pillay B, Ma CS, Moens L et al. Human inborn errors of the actin cytoskeleton affecting immunity: way beyond WAS and WIP. Immunol Cell Biol. 2019;97(4):389–402. doi: 10.1111/imcb.12243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y, Chen Y, Yin W, Han H, Miller H, Li J et al. The regulation of DOCK family proteins on T and B cells. J Leukoc Biol. 2021;109(2):383–94. doi: 10.1002/JLB.1MR0520-221RR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, Freeman AF, Jing H, Favreau AJ et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(21):2046–55. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Engelhardt KR, McGhee S, Winkler S, Sassi A, Woellner C, Lopez-Herrera G et al. Large deletions and point mutations involving the dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) in the autosomal-recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124(6):1289–302 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Su HC, Jing H, Angelus P, Freeman AF. Insights into immunity from clinical and basic science studies of DOCK8 immunodeficiency syndrome. Immunol Rev. 2019;287(1):9–19. doi: 10.1111/imr.12723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zhang Q, Davis JC, Dove CG, Su HC. Genetic, clinical, and laboratory markers for DOCK8 immunodeficiency syndrome. Dis Markers. 2010;29(3–4):131–9. doi: 10.3233/DMA-2010-0737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aydin SE, Kilic SS, Aytekin C, Kumar A, Porras O, Kainulainen L et al. DOCK8 deficiency: clinical and immunological phenotype and treatment options - a review of 136 patients. J Clin Immunol. 2015;35(2):189–98. doi: 10.1007/s10875-014-0126-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engelhardt KR, Gertz ME, Keles S, Schaffer AA, Sigmund EC, Glocker C et al. The extended clinical phenotype of 64 patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;136(2):402–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.12.1945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Al-Herz W, Chu JI, van der Spek J, Raghupathy R, Massaad MJ, Keles S et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplantation outcomes for 11 patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(3):852–9 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.02.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aydin SE, Freeman AF, Al-Herz W, Al-Mousa HA, Arnaout RK, Aydin RC et al. Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation as Treatment for Patients with DOCK8 Deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2019;7(3):848–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2018.10.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillay BA, Avery DT, Smart JM, Cole T, Choo S, Chan D et al. Hematopoietic stem cell transplant effectively rescues lymphocyte differentiation and function in DOCK8-deficient patients. JCI Insight. 2019;5. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.127527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haskologlu S, Kostel Bal S, Islamoglu C, Aytekin C, Guner S, Sevinc S et al. Clinical, immunological features and follow up of 20 patients with dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) deficiency. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2020;31(5):515–27. doi: 10.1111/pai.13236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chinn IK, Chan AY, Chen K, Chou J, Dorsey MJ, Hajjar J et al. Diagnostic interpretation of genetic studies in patients with primary immunodeficiency diseases: A working group report of the Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145(1):46–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pillay BA, Fusaro M, Gray PE, Statham AL, Burnett L, Bezrodnik L et al. Somatic reversion of pathogenic DOCK8 variants alters lymphocyte differentiation and function to effectively cure DOCK8 deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2021;131(3). doi: 10.1172/JCI142434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Randall KL, Chan SS, Ma CS, Fung I, Mei Y, Yabas M et al. DOCK8 deficiency impairs CD8 T cell survival and function in humans and mice. J Exp Med. 2011;208(11):2305–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Avery DT, Kane A, Nguyen T, Lau A, Nguyen A, Lenthall H et al. Germline-activating mutations in PIK3CD compromise B cell development and function. J Exp Med. 2018;215(8):2073–95. doi: 10.1084/jem.20180010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai SY, de Boer H, Massaad MJ, Chatila TA, Keles S, Jabara HH et al. Flow cytometry diagnosis of dedicator of cytokinesis 8 (DOCK8) deficiency. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;134(1):221–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tangye SG, Pillay B, Randall KL, Avery DT, Phan TG, Gray P et al. Dedicator of cytokinesis 8-deficient CD4(+) T cells are biased to a TH2 effector fate at the expense of TH1 and TH17 cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(3):933–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.07.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matthijs G, Souche E, Alders M, Corveleyn A, Eck S, Feenstra I et al. Guidelines for diagnostic next-generation sequencing. Eur J Hum Genet. 2016;24(1):2–5. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(15):2114–20. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim D, Paggi JM, Park C, Bennett C, Salzberg SL. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2019;37(8):907–15. doi: 10.1038/s41587-019-0201-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Frankish A, Diekhans M, Ferreira AM, Johnson R, Jungreis I, Loveland J et al. GENCODE reference annotation for the human and mouse genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(D1):D766–D73. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robinson JT, Thorvaldsdottir H, Winckler W, Guttman M, Lander ES, Getz G et al. Integrative genomics viewer. Nat Biotechnol. 2011;29(1):24–6. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brennan P drawProteins: a Bioconductor/R package for reproducible and programmatic generation of protein schematics. F1000Res. 2018;7:1105. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.14541.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jumper J, Evans R, Pritzel A, Green T, Figurnov M, Ronneberger O et al. Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold. Nature. 2021. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03819-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma CS, Tangye SG. Flow Cytometric-Based Analysis of Defects in Lymphocyte Differentiation and Function Due to Inborn Errors of Immunity. Front Immunol. 2019;10:2108. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.02108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crequer A, Troeger A, Patin E, Ma CS, Picard C, Pedergnana V et al. Human RHOH deficiency causes T cell defects and susceptibility to EV-HPV infections. J Clin Invest. 2012;122(9):3239–47. doi: 10.1172/JCI62949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moran I, Nguyen A, Khoo WH, Butt D, Bourne K, Young C et al. Memory B cells are reactivated in subcapsular proliferative foci of lymph nodes. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):3372. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-05772-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bucciol G, Pillay B, Casas-Martin J, Delafontaine S, Proesmans M, Lorent N et al. Systemic Inflammation and Myelofibrosis in a Patient with Takenouchi-Kosaki Syndrome due to CDC42 Tyr64Cys Mutation. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40(4):567–70. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00742-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edwards ESJ, Bier J, Cole TS, Wong M, Hsu P, Berglund LJ et al. Activating PIK3CD mutations impair human cytotoxic lymphocyte differentiation and function and EBV immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2019;143(1):276–91 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2018.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jing H, Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Hill BJ, Dove CG, Gelfand EW et al. Somatic reversion in dedicator of cytokinesis 8 immunodeficiency modulates disease phenotype. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014;133(6):1667–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Picard C, Bobby Gaspar H, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Casanova JL, Chatila T et al. International Union of Immunological Societies: 2017 Primary Immunodeficiency Diseases Committee Report on Inborn Errors of Immunity. J Clin Immunol. 2018;38(1):96–128. doi: 10.1007/s10875-017-0464-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Phan TG, Gray PE, Wong M, Macintosh R, Burnett L, Tangye SG et al. The Clinical Immunogenomics Research Consortium Australasia (CIRCA): a Distributed Network Model for Genomic Healthcare Delivery. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40(5):763–6. doi: 10.1007/s10875-020-00787-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Chatila T, Cunningham-Rundles C, Etzioni A et al. Human Inborn Errors of Immunity: 2019 Update on the Classification from the International Union of Immunological Societies Expert Committee. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40(1):24–64. doi: 10.1007/s10875-019-00737-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minoche AE, Lundie B, Peters GB, Ohnesorg T, Pinese M, Thomas DM et al. ClinSV: clinical grade structural and copy number variant detection from whole genome sequencing data. Genome Med. 2021;13(1):32. doi: 10.1186/s13073-021-00841-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ito K, Patel PN, Gorham JM, McDonough B, DePalma SR, Adler EE et al. Identification of pathogenic gene mutations in LMNA and MYBPC3 that alter RNA splicing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114(29):7689–94. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707741114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ribeiro M, Furtado M, Martins S, Carvalho T, Carmo-Fonseca M. RNA Splicing Defects in Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy: Implications for Diagnosis and Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(4). doi: 10.3390/ijms21041329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xu X, Han L, Zhao G, Xue S, Gao Y, Xiao J et al. LRCH1 interferes with DOCK8-Cdc42-induced T cell migration and ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Exp Med. 2017;214(1):209–26. doi: 10.1084/jem.20160068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meyts I, Bosch B, Bolze A, Boisson B, Itan Y, Belkadi A et al. Exome and genome sequencing for inborn errors of immunity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(4):957–69. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tangye SG, Al-Herz W, Bousfiha A, Cunningham-Rundles C, Franco JL, Holland SM et al. The Ever-Increasing Array of Novel Inborn Errors of Immunity: an Interim Update by the IUIS Committee. J Clin Immunol. 2021;41(3):666–79. doi: 10.1007/s10875-021-00980-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stray-Pedersen A, Sorte HS, Samarakoon P, Gambin T, Chinn IK, Coban Akdemir ZH et al. Primary immunodeficiency diseases: Genomic approaches delineate heterogeneous Mendelian disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;139(1):232–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sullivan KE. The scary world of variants of uncertain significance (VUS): A hitchhiker’s guide to interpretation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(2):492–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2020.06.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Weck KE. Interpretation of genomic sequencing: variants should be considered uncertain until proven guilty. Genet Med. 2018;20(3):291–3. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Eldomery MK, Coban-Akdemir Z, Harel T, Rosenfeld JA, Gambin T, Stray-Pedersen A et al. Lessons learned from additional research analyses of unsolved clinical exome cases. Genome Med. 2017;9(1):26. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0412-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhang Z, Xin D, Wang P, Zhou L, Hu L, Kong X et al. Noisy splicing, more than expression regulation, explains why some exons are subject to nonsense-mediated mRNA decay. BMC Biol. 2009;7:23. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-7-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khourieh J, Rao G, Habib T, Avery DT, Lefevre-Utile A, Chandesris MO et al. A deep intronic splice mutation of STAT3 underlies hyper IgE syndrome by negative dominance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2019;116(33):16463–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1901409116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boisson B, Honda Y, Ajiro M, Bustamante J, Bendavid M, Gennery AR et al. Rescue of recurrent deep intronic mutation underlying cell type-dependent quantitative NEMO deficiency. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(2):583–97. doi: 10.1172/JCI124011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Khan S, Kuruvilla M, Hagin D, Wakeland B, Liang C, Vishwanathan K et al. RNA sequencing reveals the consequences of a novel insertion in dedicator of cytokinesis-8. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016;138(1):289–92 e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Available upon request to the corresponding authors.