Abstract

Lymphatic, nervous, and tumoral tissues, among others, exhibit physiology that emerges from three-dimensional interactions between genetically unique cells. A technology capable of volumetrically imaging transcriptomes, genotypes, and morphologies in a single de novo measurement would therefore provide a critical view into the biological complexity of living systems. Here we achieve this by extending DNA microscopy, an imaging modality that encodes a spatio-genetic map of a specimen via a massive distributed network of DNA molecules inside it, to three dimensions and multiple length scales in developing zebrafish embryos.

Genomic mosaicism, the property whereby nucleotide-level differences present across the genomes of cells within tissues, are critical to organism biology and human health1. Data sets that have highlighted this intra-organismal and intra-tissue genomic diversity from the immune system2 to the nervous system3 have showcased the magnitude of missing detail in coarse gene-counts when they are not read out with DNA and RNA sequences from the same specimens.

These observations have therefore drawn a line between tissue genomic biology that is amenable to probe hybridization measurements4, where a gene’s status may be reduced to presence-versus-absence, and “de novo” sequencing-based assays which access a different level of information entirely. Concerted efforts to mend this blind spot include 2D biological pixelation5 to assign positional markers to DNA and RNA sequences, and sequencers built around individual samples6. In each of these cases, trade-offs between depth of focus, depth of capture, signal density, and resolution have placed hard bounds on the detail accessible. The genetic landscape of cell microenvironments – fundamentally phenomena that involve genetically unique three-dimensional neighborhoods – remains something we can only extrapolate, not image.

DNA microscopy is a distinct imaging modality that encodes an image of a single, “idiosyncratic” specimen into DNA using a stand-alone chemical reaction. It has previously been demonstrated in dense 2D multicellular specimens7 and has more recently been applied to the study of cell-surface protein polarity8. Theoretical variants have also been proposed9;10.

DNA microscopy begins by randomly tagging biomolecules inside a specimen with unique DNA-molecular identifiers, or UMIs. It then converts these DNA tags into an intercommunicating molecular network, where molecular copies of the original products are allowed to migrate, either by constrained or unconstrained diffusion, and link up.

The resulting linking frequencies encode spatial proximities of the original UMI tags, in the form of a UEI (unique linking-event identifier) matrix – whose rows and columns are individual UMI-tagged molecules. A statistical inverse problem is then solved on this matrix to infer the relative coordinates of the original UMIs. Any DNA or RNA sequence that these UMIs tagged may then be mapped to their corresponding locations, thereby assembling a complete spatio-genetic image of the original specimen.

Because DNA microscopy captures images from within a specimen and provides nucleotide-level readouts, it potentiates fully volumetric de novo (or zero-prior knowledge) spatio-genetic imaging. Two key barriers to broad application of DNA microscopy in three-dimensional tissues have been (1) high temperature thermal cycling for in situ PCR, that complicates uniform diffusion within the specimen, and (2) the separation of length scales that would need to be bridged computationally in order for a network of intercommunicating molecules/UMIs to inform the reconstruction of gross morphology.

Here, we overcome these barriers first experimentally, by introducing layered in situ chemistries that encode – at low and constant temperature – multiple length scales simultaneously into the output of DNA microscopy reactions. Second, we introduce an inference methodology that reconstructs encoded molecular positions over multiple length scales. We demonstrate its effectiveness on both earlier and newer data sets.

Results

Encoding multiple length scales into a DNA microscopy data set requires engineering how UEIs either localize or de-localize from their UMIs of origin. We reasoned that a separation of UEI length scales could be achieved by initially dispersing UMI copies over short (<1μm) lengths via constrained diffusion and later dispersing UMI copies over long (>10μm) lengths via unconstrained diffusion. DNA microscopy7 had previously achieved the larger of the two length scales, using biocompatible PEG hydrogels formed around the sample to eliminate convection and limit the range of DNA molecule migration during the reaction to ~50μm diameters11. We sought to execute this in parallel with ~1μm diameter DNA dispersion12;6 achieved by rolling circle amplification, or RCA, in which the leading end of a DNA molecule, polymerizing along a circular template, diffuses while anchored to its point of origin.

Volumetric DNA microscopy

The multiscale-encoding reaction is depicted in Figs 1 and S1. Briefly, RNA molecules in fixed cells were reverse-transcribed using random primers into cDNA, and 3’ DNA overhangs were added (Fig 1A). Pre-circularized DNA molecules, containing ~25nt randomized UMI sequences, were then annealed to the ends of these protruding adapters (Fig 1B). Like in the first demonstration of DNA microscopy7, two distinct UMI types (“type I” and “type II”) for purposes of preventing homo-dimerization (the pairing of a UMI with itself) later in the experiment. A strand-displacing DNA polymerase elongated the annealed DNA polymer by RCA to create DNA nanoballs with tandem copies of the same UMI.

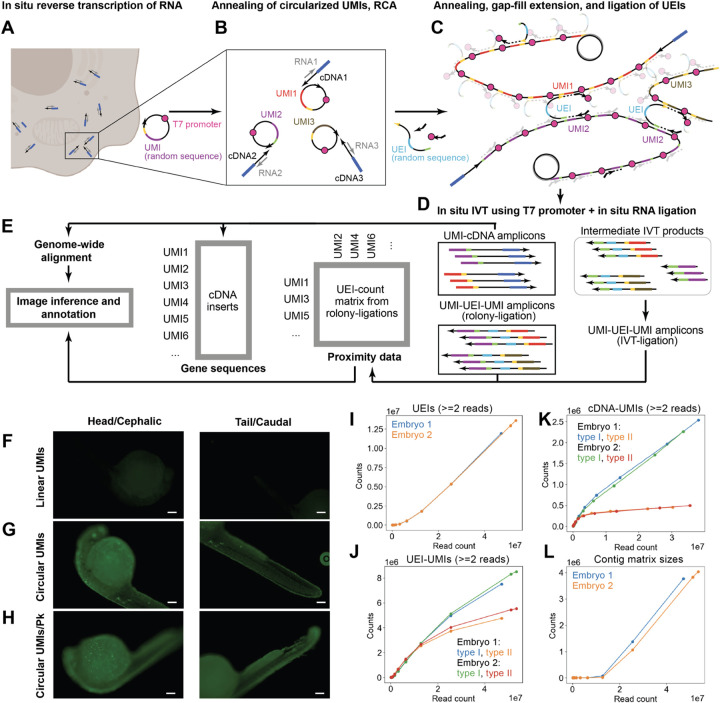

Figure 1: Volumetric DNA microscopy chemistry.

begins by in situ synthesis of cDNA amplicons in fixed and permeabilized tissue (A). Pre-circularized UMIs are then added (B) to undergo RCA (C), which generates tandem copies of UMIs that undergo constrained diffusion about their points of origin. Oligos bridge adjacent UMIs to a new “UEI” amplicon. cDNA and UEI amplicons together undergo in situ amplification via in vitro transcription (D), with a complementary ligation reaction simultaneously fusing UMI-containing by-products into a different set of UEI-links. These data collectively encode proximity and cDNA sequence data (E). Using fluorescent nucleotides during RCA shows a lack of signal when linear UMIs are used (F) compared to circularized UMIs in zebrafish embryos permeabilized by methanol alone (G) or with proteinase K (H, scale bars 100μm). Sequencing rarefaction of UEIs (I), UMIs from UEI amplicons (J), UMIs from cDNA amplicons (K), and contiguous UEI-matrix sizes (L) are shown.

The resulting DNA nanoballs physically pressed up against one another (Fig 1C), and a flanking oligonucleotide containing a randomized UEI sequence was then used to copy and label each UMI-UMI pairing uniquely. A combined in vitro transcription and ligation (“IVT-ligation”) reaction then amplified and further dimerized the resulting products (Fig 1D). All of these – abbreviated RCA-UEIs (UEIs generated from nanoball-adjacency), IVT-UEIs (UEIs generated from IVT-ligation), and cDNA (cDNA-UMI pairs) – were then further amplified by RT-PCR and sequenced (Fig 1E) for image inference and genome alignment (Table S1).

We first sought to determine whether RCA polonies in whole mount zebrafish embryos. Zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf were subjected to volumetric DNA microscopy chemistry (SI: Experimental method). We compared RCA reactions that incorporated fluorescent dUTPs by annealing either linear (Fig 1F) or pre-circularized (Fig 1G) UMIs. We found, as expected, DNA products generated in the latter but not the former. This signal was increased further by additional proteinase permeabilization of embryos (SI: Experimental method, Fig 1H). This demonstrated the permeability of the embryo under fixation conditions to circularized UMIs, enzymes, and other reagents.

Next, we performed “end-to-end” in situ reactions on 24 hpf embryos. The resulting number of distinct UEIs (Fig 1I), accompanying UMIs (Fig 1J), and separately amplified UMIs on cDNA-amplicons (Fig 1K) could be found increasing with read-counts (the latter preferentially amplifying with type-I UMIs). The sizes of contiguous UEI-matrices (Fig 1L), describing the number of UMIs that – through some set of UEI-links – were mutually connected, also increased with read-depth. Consensus cDNA amplicons were then mapped to the zebrafish genome (SI: Sequence analysis).

Image inference

Inferring a DNA microscopy image of molecules (simulated positions separated by a UEI-association “fall-off” length scale: Figs 2A–B) from sequencing data is, at its greatest level of generality, a problem of calculating which putative molecular positions minimize a statistical distance (referred to as the “distance objective”) between UEI counts we expect given these positions and the UEI counts we observe (Fig 2C). This operation is mathematically equivalent to maximizing the probability of observations given these distances (SI: GSE, Figs S3, S4). Absent constraints, the solution to this problem is prone to both measurement noise and non-uniqueness.

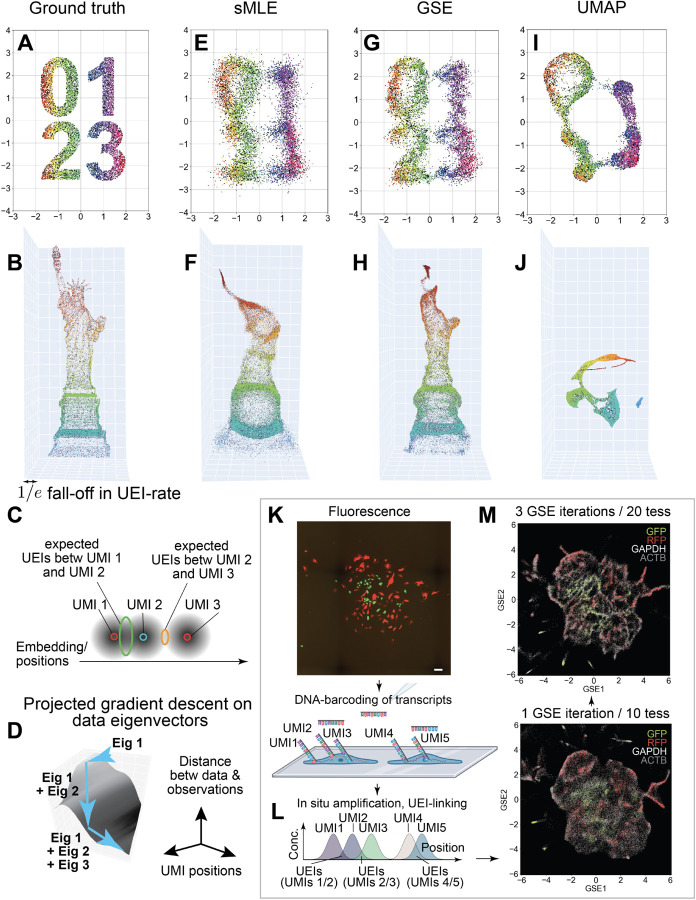

Figure 2: Geodesic Spectral Embeddings (GSE) applied to DNA microscopy simulation and experiment.

Ground truth positions (A-B) are used to simulate UEI-count matrices that sample the distribution of pairwise proximities of points across the data set (1×104 UMIs/1×105 UEIs in 2D; 5×104 UMIs/2.5×106 UEIs in 3D). Image inference identifies UMI positions producing expected UEI counts that match those observed (C). Constraining these positions using data matrix eigenvectors (D) generates sMLE solutions (E-F). Modifying these eigenvectors with the GSE algorithm improves solutions (G-H). By comparison, UMAP alone produces distortions while obscuring geometry (I-J). Applying GSE to previous (6.5×104 UMIs/7.9×105 UEIs) DNA microscopy samples (K, scale bar 100μm) whereby UMI-barcoded transcripts undergo unconstrained diffusion (L) allows sharpening of resulting inferred images (M).

Spectral maximum likelihood estimation, or sMLE, confines the position-solution to a linear combination of the top principal components, or eigenvectors, of the UEI matrix, analogous to a low-pass noise filter in optical imaging7. The optimal linear combination is determined by incrementally adding d eigenvectors (for a d-dimensional inference) to this set of eigenvectors in a “projected” gradient descent on the distance-objective until the solution converges (Fig 2D).

In two- (Fig 2E) and three-dimensions (Fig 2F), these solutions produce good but blurred approximations to underlying molecular coordinates. The reason for the shortfall of sMLE is that it uses the top eigenvectors of the “raw” UEI data matrix, which are solutions to a least-squares problem that weights all UEI counts equally.

In order to generate eigenvectors that account for differences in UEI-length scales and UMI-density across the data set, we developed a dimensionality reduction approach, called Geodesic Spectral Embeddings, or GSE. GSE directly approximates long-range curvature in the underlying manifold swept out by the data matrix in high-dimensional space. This is achieved by forming a kernel proximity matrix that describes not direct distances, but the “shortest traversable” distances along local linear tangents and their meeting points (SI: GSE). GSE eigenvectors are then used in precisely the same that raw-data eigenvectors are used in sMLE: as a basis for projected gradient descent of the full DNA microscopy solution.

Deriving GSE eigenvectors requires two parameter choices (SI: GSE). One is the degree to which the data is tessellated in order to analyze local “neighborhoods” of the UEI matrix. The second is the number of eigenvectors generated from the raw count matrix to analyze the curvature of the data manifold. Unless otherwise indicated, in the data shown we use 10 tessellations and 50 eigenvectors in each data set.

Applying GSE to simulated data (Figs 2G–H) significantly outperformed sMLE and UMAP13 (Figs 2I–J) in 2D and 3D. This demonstrated the algorithm’s generality in addressing non-uniform point distributions in higher dimensions.

We next investigated whether GSE could improve upon single length-scale DNA microscopy reconstructions7. In this earlier experiment, an ensemble of cells in culture is plated (Fig 2K, photograph from Weinstein et al 2019), and specified gene amplicons are tagged with UMIs (Fig 2L) that then undergo in situ amplification-reaction, unconstrained diffusion, and UEI-linking (analogous to the experimental design in Fig 1. The resulting UEIs are sequenced and the image is inferred. The fluorescent protein gene sequences read out from DNA microscopy are then compared back to the actual fluorescence measured in light microscopy of the same specimens.

Applying GSE to this data over a single iteration yielded resolution comparable to that found using sMLE previously7. Iterating GSE three times, each time treating newly generated GSE eigenvectors as updated “raw” count matrix eigenvectors (SI: GSE), as well as increasing the number of data-tessellations from 10 to 20, improved cell boundaries substantially (Fig 2M).

Whole organism DNA microscopy inference

Having demonstrated GSE’s effectiveness on accurately reconstructing 2D DNA microscopy data sets and 3D simulations, we sought to evaluate its ability to reconstruct whole organism data sets, such as those described in Fig 1. An initial sub-sampling of 12.8 million reads from embryo 1 generated a 7×104-UMI matrix (Fig 3A) with discernible structure. However, as the depth of sequencing increased and UMI count did so as well, the reconstruction blurred (Fig 3B), an artifact of the GSE algorithm over-fitting the “jaggedness” of the densely-populated manifold swept out by the more deeply sampled data (Fig 3C).

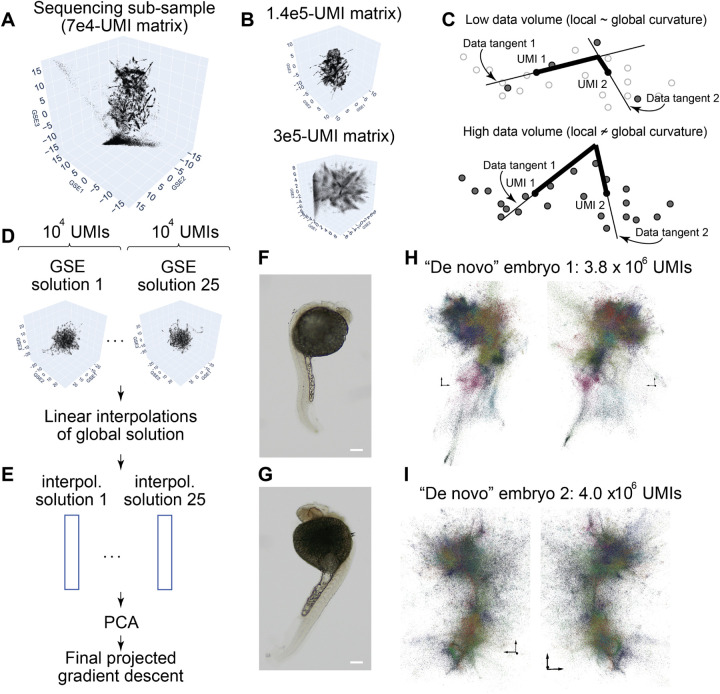

Figure 3: Large-scale 3D inference for whole-organism DNA microscopy.

Low-depth sequencing and GSE-inference produces granular detail (A) that blurs at higher sequencing depth (B), which can be qualitatively explained by GSE’s sensitivity to data “jaggedness” on deeper sampling (C). To solve this, sub-sampled data-sets (~104 UMIs) generate granular “sub-solutions” (D) from which a putative reconstruction of all 106 UMIs for each can be found by linear interpolation (E) and collated by PCA. UEI data from the original embryos 1 and 2 (F and G, respectively; scale bars 200μm) are subjected to this image inference to give final GSE embeddings for the full 106-UMI data sets (H and I, respectively, both showing two perspective angles of the same embryo). Distinct colors are arbitrarily assigned to distinct spectral clusters/segments. Axes in GSE plots indicate scales at different locations, with arrows having length of 3 GSE-units (1/e-association fall-offs).

To solve this, for each data set, we sub-sampled data to several small 104 UMI data sets (Fig 3D). For each of these “sub-solutions” (here numbering 25), a linear interpolation was then performed to estimate the locations of all UMIs not included in that specific sub-solution (Fig 3E). Performing PCA on the UMI covariances then gave a new set of eigenvectors/components to construct the global solution by an incremental projected gradient descent, on the original probability function that modeled the DNA microscopy reaction, as before.

Taking the original embryos (Figs 3F–G), whole organism inferences were generated (Figs 3H–I). Spectral clustering (SI: Clustering) similar to that previously used for segmenting cells in DNA microscopy7 was applied to identify segments within the data, where a segment was defined as including UMIs that communicated discernibly more frequently with one another with others that were otherwise nearby. The resulting images, with colors introduced to visualize distinct clusters, recapitulated gross embryo morphology, highlighting a “lobed” structure to the head and a well-defined tail/caudal region. We next sought to examine the differential representations of gene transcripts across the inferred 3D images.

Genomic sequence distribution analysis

We began by establishing a means to identify embryonic regions, by first aggregating UEIs between distinct segments colorized in Figs 3H–I, then taking the first eigenvector of the resulting UEI graph and bisecting points at its median. The resulting division of genome-mapped UMIs is depicted by distinct colors for embryos 1 and 2 in Fig 4A and B, respectively.

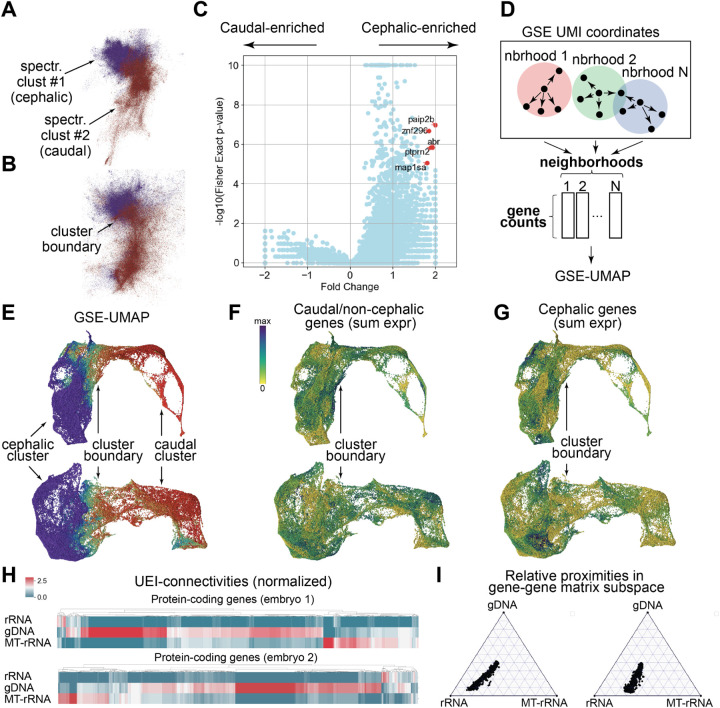

Figure 4: Spatio-genetic maps of embryos at multiple length scales.

Spectral clustering allows embryos to be divided between cephalic/head and caudal/tail domains (A-B). Performing two-sided Fisher’s Exact Test on each mapped gene using this separation (fold-differences displayed relative to the averaged value) allows for the identification of gene enrichment (C). Performing UMAP-embedding on gene-counts in 105 GSE-neighborhoods (D) provides a joint spatial-genetic embedding (E; color scale the same as in A-B) of embryos 1 (top) and 2 (bottom). Plotting a heat map on top of this embedding shows differences between summed expression of genes commonly expressed outside of the head region (F) and those predominantly expressed in the head region (G). The relative proximity of protein-coding genes to rRNA, MT-rRNA, and gDNA can be visualized either by direct UEI-connectivity, with genes shown as columns (H, only genes with ≥ 10 UEIs summed across all three categories are shown; colors scaled as number of UEIs normalized to column mean), or by relative proximities in the subspace formed by the top eigenvectors of the gene-gene interaction matrix, with genes shown as points (I).

Next, we aggregated all genome-mapped UMIs together, and constructed contingency tables for each gene, that described the number of UMIs detected for that gene on each side of the median-location versus all other mapped UMIs. These contingency tables allowed us to calculate two-sided Fisher’s Exact Tests, each provided an effective upper-bound on the p-values for the null hypothesis whereby all genes had the same distribution along the cephalic-caudal axis.

Although a large number of statistical differences were detected across the genome, we narrowed our focus to the five most head-enriched genes with p<10−5 (Fig 4C). Of these five at 24hpf, two (znf29614 and ptprn215) had been found exclusively in the brain by previous in situ hybridization (ISH) studies, one (map1sa16) had been found predominantly expressed in the head region and had a predicted role in neuronal physiology, and two (paip2b16 and abr16) were predicted more generally to be active in protein translation and cellular connections. Taken collectively, these were consistent with matching gene expression characteristics to the anatomical structures in the head and brain.

We next sought to highlight the spatio-genetic image’s recapitulation of known expression patterns still further by examining a distinct set of 20 genes commonly expressed in the head-region at 24hpf and 14 genes commonly expressed in the tail-region at 24hpf16 (Table S2). To do this, we implemented a joint spatial-genetic embedding scheme similar to a joint-embedding scheme previously used for immunoglobulins2.

Specifically, for each embryo, 1×105 UMI “neighborhoods” were assigned by randomly choosing genome-mapped UMIs throughout the data set, and finding the 5000 nearest-neighbors of each (within the GSE embedding) that also mapped to the genome. These neighborhoods, sometimes overlapping (Fig 4D) formed a new high-dimensional data set (this time in gene expression space). The resulting vectors then underwent dimensionality reduction with UMAP (generated here using 100 PCs and 100 nearest-neighbors).

The cephalic and caudal clusters of both embryos (Figs 4E, S2A-D) partitioned in a manner consistent with GSE alone (Figs 4A–B: same colorscale, with neighborhoods including UMIs from both cephalic and caudal clusters assigned an average color). Summing the expression of all 14 caudal (Fig 4F, Table S2) and all 20 cephalic (Fig 4G) genes drawn from previously measured ISH patterns yielded distinctive patterns consistent with the inferred locations along the caudal-cephalic axis.

Having established the recapitulation of gross morphology with DNA microscopy, we next sought to examine the application of such whole organism images to sub-cellular localization of molecular species. To do this, we summed UEI-counts between distinct genes/biotypes, rather than distinct UMIs.

The resulting graphs for embryos 1 and 2, depicted in relation to rRNA, MT-rRNA, and gDNA in Fig 4H, preferentially formed UEIs on a per-gene basis with gDNA, which was reduced when normalized to the UEI-sums of each of these three molecular species (Fig S2E-F). In the context of the full gene-gene connectivity matrix (using its top 100 eigenvectors, SI: Clustering), protein-coding genes showed closest proximity to rRNA (Fig 4I), consistent with their expected sub-cellular distribution.

Discussion

We have demonstrated here the capability for a massive (>106) distributed molecular network to volumetrically image a biological specimen from the “inside-out”. The implications of this work are threefold.

First, we have shown that DNA is capable of encoding massive images and that these images are capable of being decoded without the use of any specialized instrumentation beyond a DNA sequencer. This lays a critical foundation for the economy of scale this technology provides, and a broader democratization of 3D spatio-genetic imaging. This provides a clear path toward use in clinical settings, in which the impact of somatic mutation and genomic “idiosyncracy” in tumors1, lymphocytes2, the brain3 and the gut microbiome, play a critical role. Still further, the fact that all readouts are “zero-knowledge” opens up unexplored spatio-genetic complexity in non-model organisms.

Second, the inferred images here exhibit an inherent tension between being both connectivity maps and representations of Cartesian coordinates. We have shown that in simulation and practice, the implementation of a distinct methodology for dimensionality reduction – Geodesic Spectral Embeddings, or GSE – provides a scalable and reliable solution to reconciling these two disparate properties that is complementary to other common dimensionality-reduction methods. GSE may have broader application to other large data sets requiring similar reconciliation between the connectivities of nodes and their low-dimensional representations.

Third and finally, continued improvements to volumetric DNA microscopy chemistry and inference will provide a platform – distinct from and potentially complementary to conventional light and electron microscopy – for the analysis of biological circuits. The effective resolution of DNA microscopy follows a dependence on UEI-counts similar to stochastic super-resolution light microscopy’s dependence on photon-counts7, with the diffusion length scale (whether unconstrained, or constrained in the case of RCA) divided by the square root of the number of UEIs belonging to the resolved UMI. A 1μm size of RCA polonies with the 3 to 4 UEIs per UMI highlighted in Figure 1 therefore avails us of roughly the same length in resolution. Sequencing deeper, and increasing reaction yield would, however, push us well below the sub-micron regime.

In this work, we have demonstrated the ability for volumetric DNA microscopy to capture both RNA and DNA, and looking forward we anticipate acquiring proteomic details via oligo-antibody conjugates. As efforts accelerate to perform system-wide maps of neuronal circuitry in particular, the need to supplement these insights with those from molecular genetics, from gene expression, to genomic mosaicism, to spatio-proteomic measurement will take on increasing importance. We view volumetric DNA microscopy as poised to form a critical foundation for this broader undertaking.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank John Kilkus and Lillian Roderick-Buescher for help with logistics, Dr. Andrew Piacitelli for early work not included in this study that has informed our ongoing research, and Dr. Victoria Prince for help procuring zebrafish specimens. We thank Dr. Raghu Mirmira and Dr. Ryan Anderson for helpful discussions, and Dr. Feng Zhang and Dr. Aviv Regev for guidance. This work was funded in part by the Damon Runyon Foundation, the Moore Foundation, NIH-1R35GM143017–01, NIH-5R01HG009276–04 (sub-K), and NSF-2121044. The authors have filed a patent application related to this work.

References

- [1].Thorpe Jeremy, Ikeoluwa A Osei-Owusu Bracha Erlanger Avigdor, Tupler Rossella, and Pevsner Jonathan. Mosaicism in human health and disease. Annual review of genetics, 54:487–510, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Suo Chenqu, Polanski Krzysztof, Dann Emma, Rik GH Lindeboom Roser Vilarrasa-Blasi, Roser Vento-Tormo Muzlifah Haniffa, Meyer Kerstin B, Dratva Lisa M, Kelvin Tuong Zewen, et al. Dandelion uses the single-cell adaptive immune receptor repertoire to explore lymphocyte developmental origins. Nature Biotechnology, pages 1–12, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Bizzotto Sara and Walsh Christopher A. Genetic mosaicism in the human brain: from lineage tracing to neuropsychiatric disorders. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 23(5):275–286, 2022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Waylen Lisa N, Nim Hieu T, Martelotto Luciano G, and Ramialison Mirana. From whole-mount to single-cell spatial assessment of gene expression in 3d. Communications biology, 3(1):602, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Rao Anjali, Barkley Dalia, Gustavo S França, and Itai Yanai. Exploring tissue architecture using spatial transcriptomics. Nature, 596(7871):211–220, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Alon Shahar, Daniel R Goodwin Anubhav Sinha, Asmamaw T Wassie Fei Chen, Evan R Daugharthy Yosuke Bando, Kajita Atsushi, Andrew G Xue Karl Marrett, et al. Expansion sequencing: Spatially precise in situ transcriptomics in intact biological systems. Science, 371(6528):eaax2656, 2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Joshua A Weinstein Aviv Regev, and Zhang Feng. Dna microscopy: optics-free spatio-genetic imaging by a stand-alone chemical reaction. Cell, 178(1):229–241, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Karlsson Filip, Kallas Tomasz, Thiagarajan Divya, Karlsson Max, Schweitzer Maud, Jose Fernandez Navarro Louise Leijonancker, Geny Sylvain, Pettersson Erik, Rhomberg-Kauert Jan, et al. Molecular pixelation: Single cell spatial proteomics by sequencing. bioRxiv, June 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Ian T Hoffecker Yunshi Yang, Bernardinelli Giulio, Orponen Pekka, and Björn Hög-berg. A computational framework for dna sequencing microscopy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(39):19282–19287, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Alexander A Boulgakov Erhu Xiong, Bhadra Sanchita, Ellington Andrew D, and Marcotte Edward M. From space to sequence and back again: Iterative dna proximity ligation and its applications to dna-based imaging. bioRxiv, page 470211, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- [11].Xu Liyi, Brito Ilana L, Alm Eric J, and Blainey Paul C. Virtual microfluidics for digital quantification and single-cell sequencing. Nature methods, 13(9):759–762, 2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Wang Xiao, Allen William E, Wright Matthew A, Sylwestrak Emily L, Samusik Nikolay, Vesuna Sam, Evans Kathryn, Liu Cindy, Ramakrishnan Charu, Liu Jia, et al. Three-dimensional intact-tissue sequencing of single-cell transcriptional states. Science, 361(6400):eaat5691, 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Becht Etienne, Leland McInnes John Healy, Dutertre Charles-Antoine, Immanuel WH Kwok Lai Guan Ng, Ginhoux Florent, and Newell Evan W. Dimensionality reduction for visualizing single-cell data using umap. Nature biotechnology, 37(1):38–44, 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Armant Olivier, Martin März Rebecca Schmidt, Ferg Marco, Diotel Nicolas, Ertzer Raymond, Jan Christian Bryne Lixin Yang, Baader Isabelle, Reischl Markus, et al. Genome-wide, whole mount in situ analysis of transcriptional regulators in zebrafish embryos. Developmental biology, 380(2):351–362, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].van Eekelen Mark, Overvoorde John, van Rooijen Carina, and den Hertog Jeroen. Identification and expression of the family of classical protein-tyrosine phosphatases in zebrafish. PLoS One, 5(9):e12573, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Thisse Bernard, Pflumio S, Fürthauer M, Loppin B, Heyer V, Degrave A, Woehl R, Lux A, Steffan T, Charbonnier XQ, et al. Expression of the zebrafish genome during embryogenesis. ZFIN direct data submission, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.