SUMMARY

Establishing germ cell sexual identity is critical for development of male and female germline stem cells (GSCs) and production of sperm or eggs. Germ cells depend on signals from the somatic gonad to determine sex, but in organisms such as flies, mice, and humans, the sex chromosome genotype of the germ cells is also important for germline sexual development. How somatic signals and germ-cell-intrinsic cues combine to regulate germline sex determination is thus a key question. We find that JAK/STAT signaling in the GSC niche promotes male identity in germ cells, in part by activating the chromatin reader Phf7. Further, we find that JAK/STAT signaling is blocked in XX (female) germ cells through the action of the sex determination gene Sex lethal to preserve female identity. Thus, an important function of germline sexual identity is to control how GSCs respond to signals in their niche environment.

In brief

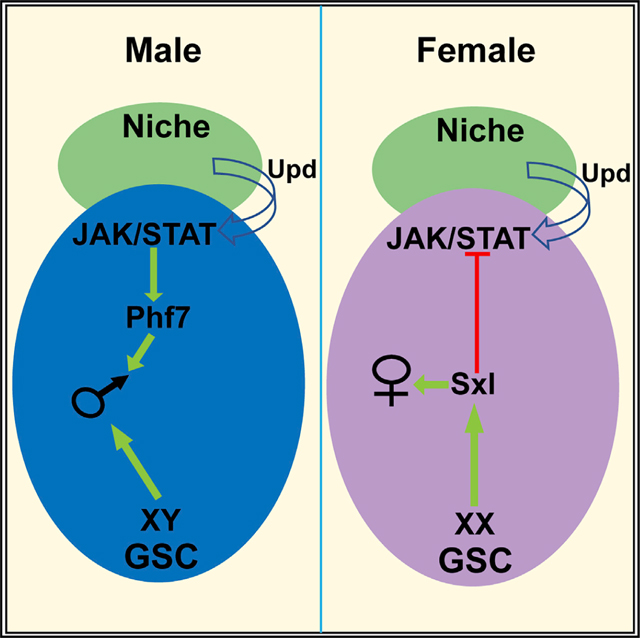

Bhaskar et al. show that germline sexual identity controls how germline stem cells respond to signals in their niche environment. JAK/STAT signaling promotes male germline sexual identity by activating the chromatin factor Phf7, and Sxl acts in female germ cells to block JAK/STAT signaling and preserve female identity.

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Sexual dimorphism, the differences between the sexes, manifests as distinct developmental programs in males and females, resulting in sex-specific anatomy, physiology, and behavior. Nowhere is this more important than in the germline, which is responsible for producing the sex-specific gametes necessary for perpetuation of the species. However, the process of sex determination in the germline is still poorly understood in most animals. One key aspect of sex determination is whether it is established autonomously by the germ cell’s own sex chromosome constitution, non-autonomously via signals from somatic cells, or both. In some animals, the sex of the soma is sufficient to control the sex of the germline, as germ cells are able to follow the correct developmental path (spermatogenesis or oogenesis) regardless of the sex of the soma (e.g., Hilfiker-Kleiner et al., 1994; Blackler, 1965; Yoshizaki et al., 2011). However, in organisms such as Drosophila and humans, germ cell development fails if the “sex” of the germline does not match the “sex” of the soma. For example, in Drosophila, XX (normally female) germ cells transplanted into an XY (male) somatic environment are lost during development (Van Deusen, 1977), while germ cells in sex-transformed “XX males” are atrophic and fail to develop into sperm (Sturtevant, 1945; Nöthiger et al., 1989) (Figure 2B). Similarly, XY germ cells present in a female somatic environment do not enter oogenesis but instead form germline tumors (Schüpbach, 1982, 1985; Steinmann-Zwicky et al., 1989). In humans, Turner’s syndrome patients have an X0 genotype, and the soma follows a female developmental program due to the lack of a Y chromosome. However, these patients are infertile due to germline loss and incomplete oogenesis (Ye et al., 2020). Thus, the presence of a single X chromosome in the germline is thought to be incompatible with female germline development. Similarly, Klinefelter’s patients (XXY) develop somatically as males but are also infertile, and rare patches of spermatogenesis observed in testes of these individuals are due to germ cells having lost one X chromosome (now XY) (Deebel et al., 2020). Thus, in both flies and humans, the sex chromosome genotype of the germ cells has a strong effect on proper germline sexual development, indicating that germline autonomous cues combine with non-autonomous cues from the soma to regulate this process.

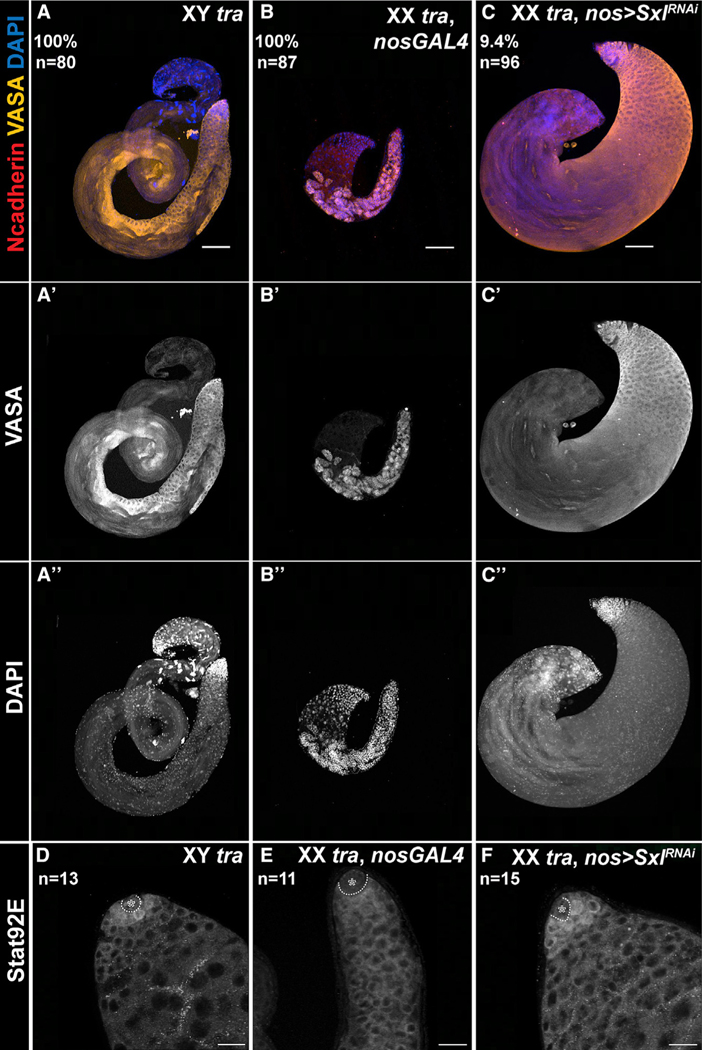

Figure 2. Restoring JAK-STAT signaling in XX tra testes partially rescues germline depletion.

Antibody staining as indicated.

(A–D) Anti-Vasa labels germ cells, anti-NCad labels the hub, and DAPI marks DNA.

(A) XY tra (control) testis, (B) XX tra testes, (C) XX tra testes expressing activated JAK, hopTUM, and (D) XX tra testes expressing activated STAT92E in germ cells, nos > Stat92EΔNΔC. Percent rescue and sample size are indicated in the panels.

(E–H) Anti-Stat92E labeling of the same genotypes as indicated in (A)–(D). Note that the decreased anti-Stat92E immunostaining observed in (F) is rescued by activation of the JAK/STAT pathway in (G) and (H). Hubs are indicated by dashed lines and asterisks, and representative GSCs are indicated by arrows. n indicates number of gonads analyzed for each group. Scale bar, (A–D) 100 μm, (E–H) 20 μm.

In Drosophila, Sex lethal (Sxl) is the key gene acting autonomously in the germline to promote female sexual identity. Sxl encodes an RNA binding protein that acts in regulating both alternative mRNA splicing and translational control (Bashaw and Baker, 1997; Bell et al., 1988; Keyes et al., 1992; Kelley et al., 1997; Gebauer et al., 1998). Loss of Sxl specifically from germ cells disrupts oogenesis and causes germ cells to produce ovarian tumors, similar to XY germ cells developing in a female soma (Schüpbach, 1985). Further, expression of Sxl in XY germ cells is sufficient to allow them to complete oogenesis when present in a female soma (Hashiyama et al., 2011). Interestingly, Sxl is also the key “switch” gene that regulates female identity in the soma (Cline, 1979). In both the soma and the germline, Sxl expression depends on the presence of two X chromosomes, but the genetics of Sxl activation in the female soma are different from that in the germline (Granadino et al., 1993;Steinmann-Zwicky, 1993). Further, the targets for regulation by Sxl in the soma, transformer (tra), which regulates female somatic identity, and male specific lethal 2, which regulates X chromosome dosage compensation in the soma, are not required in the germline (Bachiller and Sanchez, 1986; Marsh and Wieschaus, 1978). Thus, the way in which Sxl acts to control female sexual identity in the germline is largely unknown.

How signals from somatic cells also act to control germline sexual identity is similarly unknown. Previously, we have found that the JAK/STAT (Janus kinase/signal transducer and activator of transcription) pathway acts as an important signal from the soma to promote male identity in the germline (Wawersik et al., 2005). Initially, in the embryonic gonad, male somatic cells express JAK/STAT ligand(s) that promote male gene expression and behavior in the germline (Wawersik et al., 2005; Sheng et al., 2009). However, the JAK/STAT pathway is eventually activated in the gonads of females as well, where it is important for essential somatic cell types (e.g., the escort cells; Decotto and Spradling, 2005). Why the presence of the JAK/STAT pathway in the ovary does not masculinize the germ cells has remained unknown.

One place where germline sexual dimorphism is particularly apparent is in the germline stem cells (GSCs). GSCs are responsible for the continuous production of germ cells that enter gametogenesis and produce the large numbers of gametes necessary for full fertility. In many animals, GSCs are present in both males and females, yet their behavior and the processes of spermatogenesis versus oogenesis exhibit clear sexual dimorphism (Casper and Van Doren, 2006; Spradling et al., 2011). Further, mammals like mice and humans only have GSCs in the testis, while the ovary contains a pre-determined set of developing oocytes. Thus, the differences between the sexes are even more extreme in these animals. How germline sex determination leads to such dramatic differences in GSC behavior and potential is largely unexplored. Interestingly, the JAK/STAT pathway is also a key regulator of GSC behavior in Drosophila males but is not required in female GSCs (Kiger et al., 2001; Tulina and Matunis, 2001; Leatherman and Dinardo, 2010; Decotto and Spradling, 2005; Chen et al., 2018). Thus, the JAK/STAT pathway may provide a link between germline sex determination and GSC identity and behavior.

Here we show that one way in which Sxl acts to promote female identity in the germline is by blocking reception of the JAK/STAT signal in female GSCs. Further, we show that the chromatin reader Plant homeodomain-containing factor 7 (Phf7), an important regulator of male identity in the germline (Yang et al., 2012), is a direct downstream target of JAK/STAT signaling in male germ cells. Thus, a key aspect of how germline autonomous information interacts with non-autonomous signals from the soma is by influencing how GSCs interact with their niche environment.

RESULTS

XX germ cells exhibit decreased JAK/STAT signaling

To explore how the somatic environment and germline autonomous cues combine to control germline sexual development, we first explored the development of XX germ cells in a male somatic environment. tra is essential for female identity in the soma, and tra mutant animals exhibit a robust female to male transformation, but tra has no known role in males, and XY tra animals are indistinguishable from wild-type (WT) males (Sturtevant, 1945). However, since tra is not required in the female germline (Marsh and Wieschaus, 1978), XX tra mutants allow us to study otherwise normal XX germ cells in a male somatic environment (hereafter referred to as XX males). Previously, it has been shown that the germline in XX males is severely atrophic, with depleted germline and a lack of differentiating germ cells (Steinmann-Zwicky et al., 1989) (Hinson and Nagoshi, 1999) (Figures S1A and S1B). We examined gonad development in XX males and found that soma-germline interaction and formation of the male germline stem cell niche appeared completely normal until the third instar larval (L3) stage (Murray., 2011). However, L3 gonads of XX males exhibited an atrophic germline (compare Figures S1D and S1D′ to S1C and S1C′) with a reduced number of GSCs (average number of GSCs: control male = 10.9 ± 1.75, n = 16; XX male = 6.85 ± 1.5, n = 13). One of the main differences between XY and XX animals is that control XX females and XX males express the sex determination factor Sxl in the germline, while XY males do not (Figures S1E–S1G). In addition, XY individuals expressing ectopic TraF protein (XY females) (Figure S1H) fail to express Sxl, indicating that expression of Sxl in the germline is dependent only on the germ cell genotype and is independent of somatic cues.

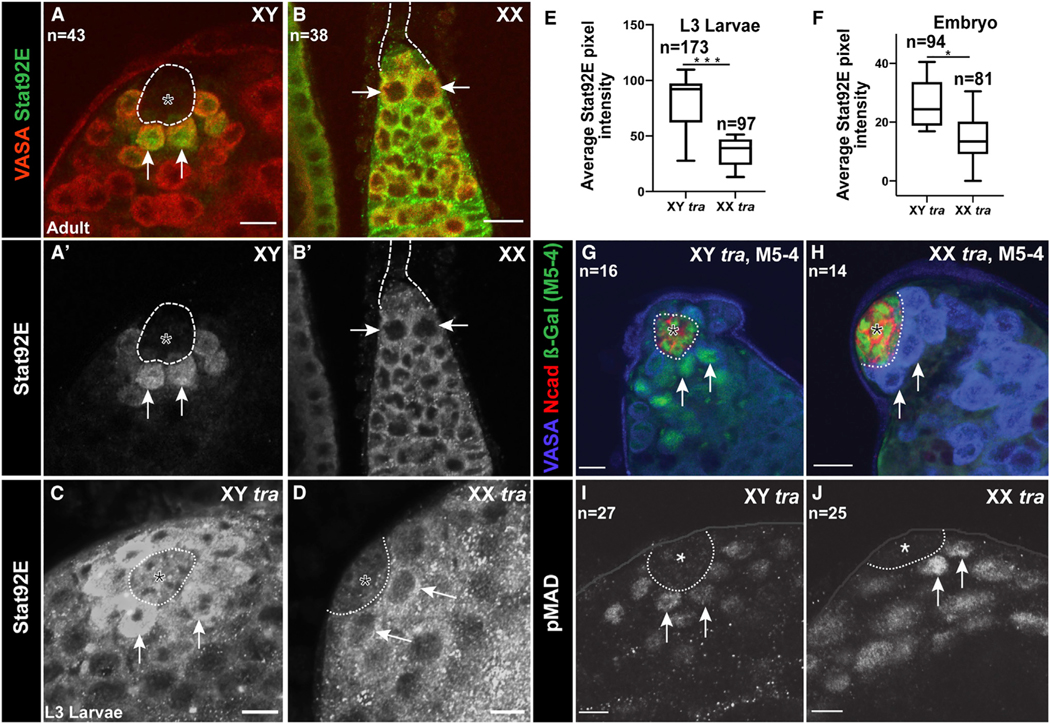

Another important sex-specific quality of the GSCs is their requirement for different signals from the surrounding niche. Male GSCs require signaling through the JAK/STAT pathway for their proper behavior (Chen et al., 2018; Kiger et al., 2001; Leatherman and Dinardo, 2010; Tulina and Matunis, 2001). In contrast, female GSCs do not require this pathway, though it is active in the region of the adult female niche where it signals to cap cells and escort cells (Decotto and Spradling, 2005; López-Onieva et al., 2008). Interestingly, even though this signal is present in both adult male and female GSC niches, we find that this pathway is only activated in male GSCs and not female GSCs (Figures 1A and 1B). Activation of the JAK/STAT pathway often leads to an increase in the Stat92E protein, and this is commonly used as an assay for pathway activation (Chen et al., 2003; Yan et al., 1996). We observed a clear increase of Stat92E protein in male GSCs (arrows in Figure 1A), as has been previously observed, but we failed to see an increase in female GSCs (arrows in Figure 1B). In contrast, the somatic cells surrounding female GSCs do exhibit Stat92E expression, consistent with a role for this pathway in the cap cells and escort cells (Figure 1B).

Figure 1. XX GSCs show a decreased response to JAK-STAT signaling from the niche.

Antibody staining as indicated in figure. Anti-Vasa labels germ cells. GSC niches outlined with dashed line.

(A, A′, B, and B′) Anti-Stat92E (green) labeling in adult gonads. Note that GSCs (e.g., arrows) exhibit strong immunoreactivity in males (A, A′) but not in females (B, B′).

(C and D) Anti-Stat92E immunostaining of XY tra or XX tra L3 testes. Note the reduced immunostaining in XX tra testes (D).

(E and F) Boxplot and whiskers plot of the mean Stat92E pixel intensity per testis for XY tra or XX tra L3 testes (E) or stage 15–16 embryos (F). *(p < .05) **(p < 0.005) ***(p < 0.0005). Error bars represent SEM from three biological replicates. Asterisks show p values and were calculated by an unpaired t test. (E) L3 XY tra1/D versus XX tra1/D. p = .00000028. (F) Stage 15/16 XY tra1/D versus XX tra1/D. p = .0065.

(G and H) M5–4 enhancer trap in XY tra and XX tra testes. Note the loss of M5–4 staining in germ cells of XX testes (H).

(I and J) pMad expression in XY tra L3 testes (I), XX tra, L3 testes (J). n indicates number of gonads analyzed for each group. Asterisk indicates hub. Scale bar, 10um.

To determine whether the differential response to the JAK/STAT pathway is due to the sex chromosome constitution of the germ cells, we examined Stat92E immunoreactivity in XX males. Interestingly, we found greatly reduced Stat92E staining in GSCs of XX males compared to controls (Figures 1C–1E; note that L3 larvae were analyzed since their morphology is more normal than XX tra adults). Previously, we had shown that JAK/STAT signaling is normally male specific in the embryonic gonad, and the pathway can be activated in XX males (Wawersik et al., 2005). To investigate whether embryonic XY and XX germ cells also showed a differential response to the JAK/STAT pathway, we quantified the Stat92E immunofluorescence signal in XX males. Indeed, embryonic germ cells in XX males exhibited a lower level of Stat92E immunoreactivity than did XY controls, although the difference was not as great as in larval gonads (Figure 1F). Lastly, as an independent assay of JAK/STAT response, we used the M5–4 enhancer trap, which is responsive to the JAK/STAT pathway (Gönczy and DiNardo, 1996). In WT testes, M5–4 is expressed in the hub and the hub-proximal germ cells (GSCs and early spermatogonia), and this is what we observed in XY control testes (Figure 1G). In contrast, we detected no M5–4 expression in the germline of XX male testes, although the expression in the hub remained similar to WT males, as expected (compare Figures 1H and 1G).

For comparison, we also examined signaling through the bone morphogenetic protein (BMP) pathway, which has been shown to be important for regulation of both the male and female GSCs (Schulz et al., 2004; Xie and Spradling, 1998). In contrast to what we found for the JAK/STAT pathway, we observed phosphorylated Mothers against Dpp (pMAD), a downstream target of activated BMP signaling, in both control and XX male germ cells (Figures 1I and 1J). Taken together, we conclude that the male germline niche is capable of signaling to both XY and XX germ cells, but that XX germ cells have a reduced ability to respond to the JAK/STAT pathway compared to XY germ cells.

JAK/STAT activation rescues XX germ cells in a male somatic environment

We next wanted to determine whether decreased JAK/STAT signaling contributed to the germline defects observed in XX males. Inclusion of a dominant activated allele of the Drosophila JAK (hopscotch, hopTum) (Hanratty and Dearolf, 1993; Harrison et al., 1995), in XX males significantly rescued germline depletion in 8.4% (n = 83) of testes (Figures 2C and 2G). The presence of hopTum also increased the JAK/STAT response (as judged by Stat92E immunoreactivity) in XX male germ cells (compare Figures 2G–2F, quantified in S4A). Rescued testes exhibited a large increase in the number of germ cells. In addition, normal testes exhibit brighter DAPI staining in undifferentiated GSCs and early gonial cells, and DAPI intensity diminishes as germ cells differentiate (Figure 2A′′). These changes in DAPI staining were also observed in rescued XX males (Figure 2C′′), indicating that these were not tumors of early germline, but rather the XX germ cells of rescued testes were differentiating. Consistent with this, differentiating sperm were observed in most of the rescued testes (Figures S2C and S2E). A similar result was obtained when we expressed an activated Stat92E (UAS-Stat92EΔNΔC) (Ekas et al., 2010) specifically in the germline, which restored STAT expression (Figure 2H, quantified in S4A) and rescued the germline (Figure 2D; 13.15% of testes, n = 38; Figure S2). The rescue of XX males by the JAK/STAT pathway occurred in an “all or none” manner; either the germline in XX males appeared substantially rescued as shown (Figures 2C and 2D) or unrescued similar to controls (Figures S3A and S3B), without exhibiting intermediate phenotypes. Since restoring JAK/STAT signaling to the germline is sufficient to rescue at least a fraction of XX males, we conclude that decreased JAK/STAT signaling is an important contributing factor to the inability of XX germ cells to develop normally in a male somatic environment.

Sxl activity represses the JAK-STAT pathway

Since a major difference between XX and XY germ cells is the expression of Sxl in XX germ cells, we next asked whether Sxl was responsible for the decreased JAK/STAT response in XX germ cells. Knocking down Sxl in the germline (nos > SxlRNAi) was able to restore Stat92E immunoreactivity to GSCs in XX males (compare Figures 3F–3E, quantified in S4A) and rescue the germline defects to a similar extent (Figure 3C; 9.4% [n = 96]) as was observed when the JAK/STAT pathway was activated directly. When we combined activation of the JAK/STAT pathway with Sxl knockdown in XX males (XX tra, hopTum, nos > SxlRNAi), no further increase in the percentage of germline rescue was observed (8.7% [n = 45]; Figure S2E). The absence of an additive effect leads us to conclude that activation of JAK/STAT and reduction of Sxl are acting in similar ways to rescue XX male germ cells, and that likely one major effect of reducing Sxl is to restore JAK/STAT activity to these germ cells.

Figure 3. Loss of Sxl rescues the germline and STAT response in XX tra testes.

(A–C) Anti-N-cadherin (red), anti-Vasa (yellow), and DAPI (blue) in XY tra testes (A), XX tra > nos-Gal4 testes (B), XX tra testes expressing Sxl RNAi in germ cells, (C) nos > SxlRNAi. Percent rescue and sample size are indicated in the panel.

(D–F) Stat92E expression in XY tra testes (D), XX tra testes expressing nosGAL4 (E), and XX tra testes expressing Sxl RNAi in germ cells, nos > SxlRNAi (F). Hubs are indicated by dashed line and asterisks in (D)–(F). n indicates number of gonads analyzed for each group. Scale bars, (A–C′′) 100 μm, (D–F) 20 μm.

We next asked if expression of Sxl was sufficient to reduce JAK/STAT signaling in otherwise normal XY testes. Quantification of fluorescence intensity indicated that Stat92E immunoreactivity was decreased in GSCs from testes expressing Sxl relative to WT testes (Figure S4B). We also observed germline defects similar to what is observed when JAK/STAT pathway activity is inhibited in the germline (Figures S4C–S4E′). We conclude that Sxl expression is sufficient to reduce JAK/STAT signaling in otherwise WT male GSCs.

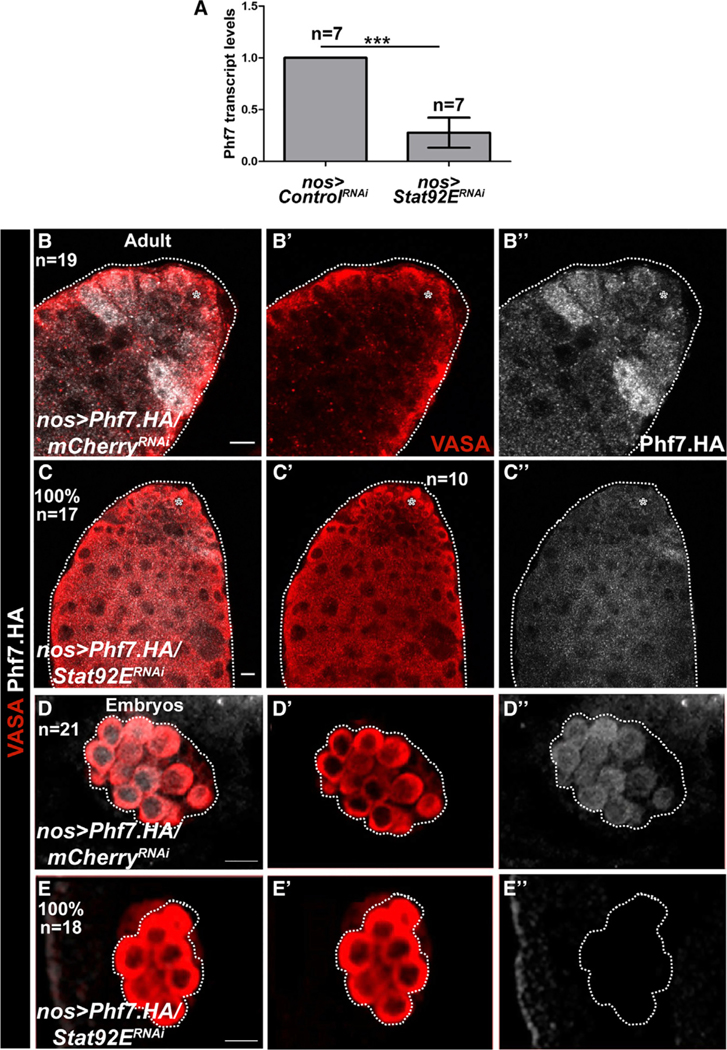

Phf7 is a direct target of the JAK/STAT pathway in the germline

We next wanted to determine why sex-specific JAK/STAT signaling is important for male germ cells. Previously, we identified Phf7 as being expressed male specifically in the adult germline and being important for male fertility (Yang et al., 2012). Phf7 expression begins during embryogenesis where it is also male specific (Figure S6). Phf7 is also toxic to female germ cells, and so it is also essential to repress it in the female germline (Yang et al., 2012). Interestingly, upregulation of Phf7 was sufficient to rescue the germline defects in a fraction of XX males (Yang et al., 2012), similar to what we observed for activation of the JAK/STAT pathway or knockdown of Sxl. Therefore, we investigated whether Phf7 was a direct target of the JAK/STAT pathway in the germline.

Previous RNA-seq analysis by our lab and others indicated that Phf7 utilizes alternative promoters in males and females and that the upstream, male-specific promoter is repressed in a Sxl-dependent manner in females (Figure S5) (Primus et al., 2019; Shapiro-Kulnane et al., 2015). An interesting possibility is that the upstream promoter of Phf7 might be regulated by the JAK/STAT pathway, which would explain both its preferential usage in males and the role of Sxl in regulating this promoter (Figure S5C). To test this idea, we first conducted qRT-PCR on control testes, compared to testes where Stat92E was knocked down by RNAi. We observed that levels of the Phf7 transcript from the upstream promoter were dramatically reduced in Stat92E germline knockdown testes compared to controls (Figure 4A). We also examined Phf7 protein expression using a hemagglutinin (HA)-epitope tagged Phf7 genomic transgene that recapitulates male-specific Phf7 expression in both embryos and adults and rescues the Phf7 mutant phenotype (Yang et al., 2012) (Figures 4B, 5B, and S6). We observed a strong decrease in HA-Phf7 expression when Stat92E was depleted in the germline using two independent RNAi lines (Figure 4 and data not shown). Loss of HA-Phf7 expression was observed both in adult testes (Figures 4B and 4C) and male embryonic gonads (Figures 4D and 4E) upon Stat92E depletion. Together, the immunofluorescence and RT-PCR data indicate that the upstream promoter of Phf7 is regulated by the JAK/STAT pathway, and this has significant consequences on the production of the Phf7 protein.

Figure 4. STAT regulates Phf7 expression in the germline.

(A) qRT-PCR analysis of Phf7 transcript levels in control versus germline Stat92ERNAi adult testes normalized to control testes. ***p < 0.0001. Error bars represent SEM from three biological replicates. Asterisks show p values and were calculated by an unpaired t test.

(B–D) Anti-HA immunolabeling to reveal expression from an HA-epitope tagged genomic Phf7 transgene that rescues the Phf7 mutant phenotype (Yang et al., 2012). (B, C) Control and germline Stat92ERNAi adults.

(D and E) Control and germline Stat92ERNAi embryos. Note in all cases that knockdown of Stat92E leads to reduction in Phf7 expression.

(B–E′′) n indicates number of gonads analyzed for each group. Scale bar, 10 μm.

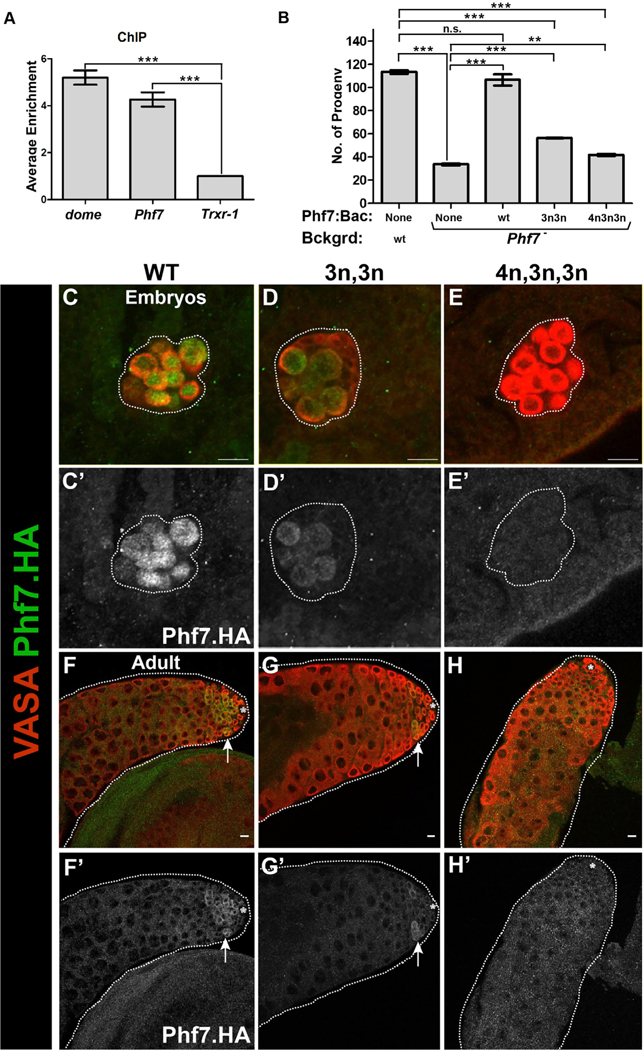

Figure 5. Stat92E is a direct transcriptional activator of Phf7.

(A) Chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by PCR (ChIP-PCR) shows that STAT92E binds to the Phf7 locus. domeless (dome) was used as positive control, while thioredoxin (Trxr-1) was used as negative control and for normalization. ***p < 0.001. Error bars represent SEM from three biological replicates. Asterisks show p values and were calculated by an unpaired t test. domeless versus Trxr-1 and Phf7 versus Trxr-1 p < 0.0001.

(B) Rescue of the Phf7 mutant male fecundity defect by HA-Phf7 genomic transgenes. Genotypes are as indicated. 3n3n refers to the transgene with two Stat92E binding sites mutated, and 4n3n3n refers to the transgene with all three Stat92E binding sites mutated. p* <0.05, **<0.01, *** <0.001, n.s., not significant. Error bars represent SEM from three biological replicates. Asterisks show p values and were calculated by an unpaired t test. WT versus Phf7– p < 0.0001, WT versus Phf7–/Phf7Bac p = 0.2489, WT versus 3n 3n/Phf7– p < 0.0001, WT versus 4n 3n 3n/Phf7– p < 0.0001, Phf7– versus Phf7–/PHf7HA p = 0.0001, Phf7– versus 3n 3n/Phf7– p < 0.0001, Phf7– versus 4n 3n 3n/Phf7– p = 0.0014.

(C–H) Gonads immunostained to reveal expression of HA-Phf7 genomic transgenes.

(C–E) Embryonic male gonads.

(F–H) Adult testes. HA-Phf7 transgenes are as follows: (C, F) WT transgene, (D, G) transgene with two consensus Stat92E binding sites mutated, (E, H) transgene with all three consensus Stat92E binding sites mutated. Note that loss of two binding sites greatly reduces HA-Phf7 expression, while loss of all three appears to eliminate HA-Phf7 expression. Scale bar, 10 μm. Samples sizes indicated in Figure S7.

To determine whether Phf7 is a direct target of the JAK/STAT pathway, we first used a GFP-tagged Stat92E transgene (Venken et al., 2009) to conduct chromatin immunoprecipitation followed by PCR (ChIP-PCR). Anti-GFP ChIP-PCR revealed that DNA from the Phf7 locus was enriched relative to a negative control (thioredoxin) and to a similar degree as a known Stat92E target (domeless) (Rivas et al., 2008) (Figure 5A). STAT proteins are known to bind to the consensus sequence TTCN2–4GAA (Rivas et al., 2008; Yan et al., 1996) with Drosophila Stat92E exhibiting a preference for a three-nucleotide spacer (3N) (Yan et al., 1996). Interestingly, there are three consensus STAT sites downstream of the male-specific transcription start (exon 1 of the male transcript; Figure S5C), two with 3N spacing and one with 4N spacing. We mutated these sites within the context of the HA-Phf7 transgene to determine their importance for Phf7 expression (Figure S5C). Mutation of the two 3N sites caused a dramatic decrease in HA-Phf7 immunostaining in both the embryonic and adult germ cells (Figures 5D and 5G and quantified in S7), while mutation of all three consensus STAT binding sites led to an absence of HA-Phf7 immunoreactivity (Figures 5E and 5H and quantified in S7). Finally, we determined the functional consequences of mutating the consensus STAT binding sites for Phf7 function in vivo. The HA-Phf7 genomic transgene is able to rescue the fertility defects observed in Phf7 mutants (Yang et al., 2012) (Figure 5B). Mutation of either two or all three of the STAT sites in Phf7 exon 1 resulted in a greatly reduced ability of the modified HA-Phf7 transgene to rescue the decreased fertility of Phf7 mutants. We conclude that Phf7 is a direct JAK/STAT target in the male germline and that this regulation is essential for Phf7 expression and function.

Phf7 is repressed in female germ cells via its 5′UTR

The JAK/STAT pathway is an important regulator of the upstream, male-specific promoter of Phf7. However, our previous RNA-seq analysis indicated that there is a significant level of Phf7 expression from the downstream promoter present in females (Figure S5A), and this is also evident from consortium data (Contrino et al., 2012; STAT92E-GFP_12–24 h_embryonic_ChIP-seq). Given that we observe little expression of Phf7 protein in the ovary (Yang et al., 2012) (Figure 6) and that Phf7 expression is toxic to the female germline, we wondered if the Phf7 transcript from the downstream promoter was subject to translational repression.

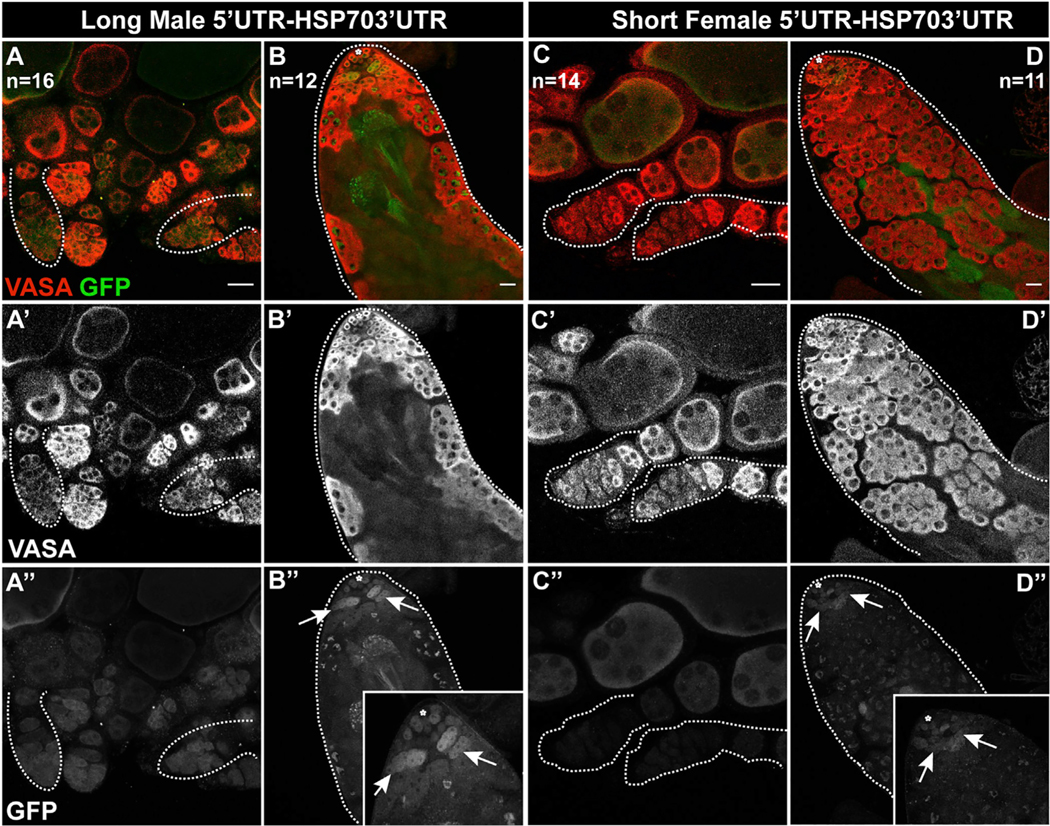

Figure 6. Phf7 is repressed in female germ cells via its 5′UTR.

Expression of UAS-GFP transgenes with either the longer, male-biased 5′UTR (A, B) or the shorter, female-biased 5′UTR (C, D) as indicated by anti-GFP immunostaining. Expression is shown in both ovaries (A, C) and testes (B, D). Note that expression of the short 5′UTR construct (C) is much lower than expression of the long 5′UTR (A) in the germaria of ovaries (e.g., outlines). There is also a difference in testes, although some expression from the short 5′UTR (D) persists in testes. Insets in B” and D′′ focus on the anti-GFP immunostaining in the undifferentiated germline. n indicates number of gonads analyzed for each group. Scale bar, 20 ′m.

The Phf7 mRNA from the male-biased, upstream promoter includes the entire female mRNA along with 170 nt of additional 5′UTR. We constructed Gal4-responsive (UAS) GFP transgenes containing the 5′UTRs from either the long “male” transcript from the upstream promoter or the shorter “female” transcript from the downstream promoter (Figure S5) and compared their expression when driven by nos-Gal4 in the male and female germline. We found that, in the germarium of females, germline GFP expression was greatly reduced from the construct containing the female 5′UTR compared with the male 5′UTR (outlines, Figures 6A and 6C). Increased levels of GFP expression were observed in later egg chambers expressing the female 5′UTR, suggesting that repression of this message might be specific to the early germline. Interestingly, GFP expression was more similar between the male and female 5′UTR constructs in the male germline, with expression from the female 5′UTR construct still clearly visible (Figures 6B and 6D). The female 5′UTR is a shorter version of the male 5′UTR but contains the same sequences and utilizes the same translation start sequence. Why the shorter, female 5′UTR should lead to repression in the ovary is unknown, but it is likely important to prevent expression of Phf7 protein in the undifferentiated female germline, where it is toxic (Yang et al., 2012).

The relationship between Phf7, the JAK/STAT pathway, and Sxl

Since the JAK/STAT pathway is upregulated upon loss of Sxl, which should lead to Phf7 upregulation, we next wanted to determine whether increased Phf7 expression contributes to the defects observed in Sxl-depleted XX germ cells. To determine if Phf7 is upregulated in XX germ cells lacking Sxl function, we examined expression of the HA-Phf7 genomic transgene in animals where Sxl was knocked down in the germ cells (nos > SxlRNAi). Indeed, we observed upregulation of HA-Phf7 immunoreactivity in the tumorous germline of nos > SxlRNAi females, while HA-Phf7 was not observed in control females (Figures 7A and 7B). nos >SxlRNAi females also exhibit an increase in Stat92E immunoreactivity in the germline tumors (Figure S8). Similar results were observed examining HA-Phf7 and Stat92E expression in sans fille (snf) mutant ovaries, which also lack Sxl (Shapiro-Kulnane et al., 2015). We next wanted to determine if the increased Phf7 expression observed in nos > SxlRNAi females was the main factor causing the nos > SxlRNAi germline tumor phenotype. If this is the case, then blocking Phf7 function should rescue the nos > SxlRNAi mutant phenotype. However, we observed no such rescue, and loss of both Sxl and Phf7 appeared very similar or identical to loss of Sxl alone (Figures 7C versus 7B). This is in contrast to what has been reported by the Salz lab using snf mutants, which, again, lead to a loss of Sxl in the germline. They report that knocking down Phf7 in the germline (nos > Phf7RNAi) was able to rescue the snf ovarian tumor phenotype and restore oogenesis (Shapiro-Kulnane et al., 2015). Due to the conflicting nature of these results, we repeated the experiment reported by Salz and colleagues using the same genetic reagents. However, in contrast to their observations, we saw no rescue of the snf ovarian tumor phenotype when Phf7 was depleted in the germline. We then conducted similar experiments using a null allele of Phf7 in combination with either the same snf mutants (snf148) or nos > SxlRNAi. Again, we saw no effect of loss of Phf7 on the ovarian tumor phenotype caused by loss of Sxl or snf function (data not shown).

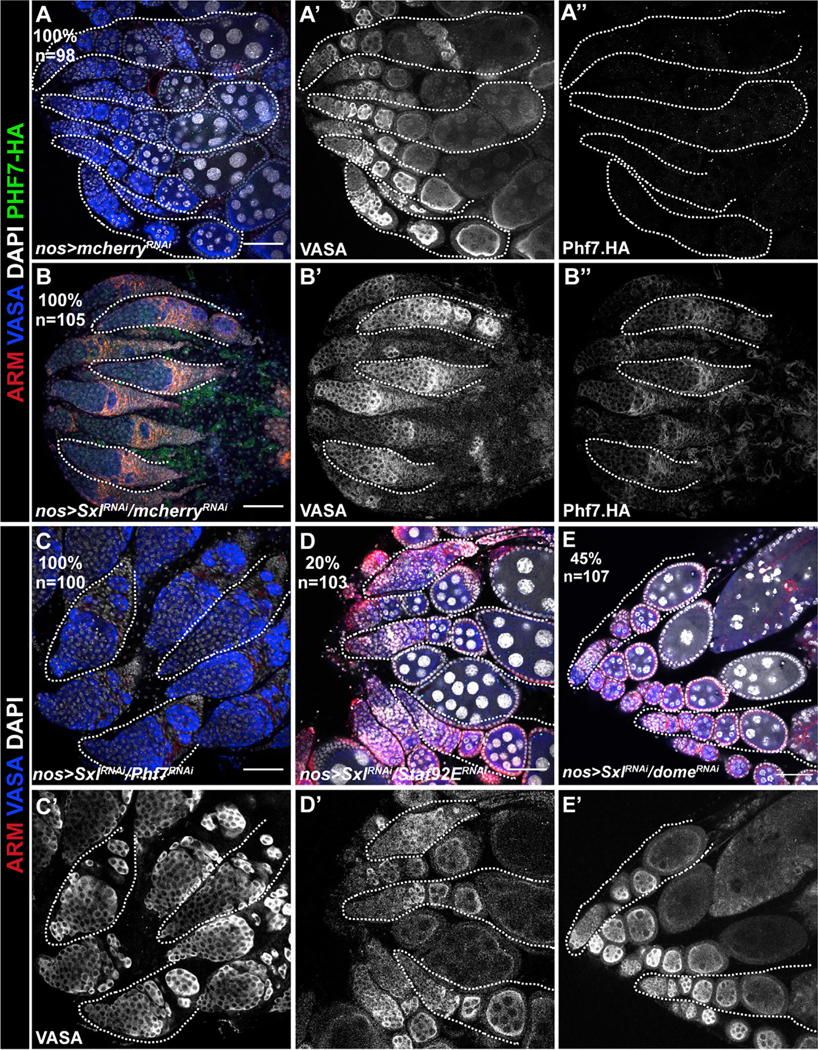

Figure 7. Sxl promotes female sexual identity by repressing the JAK/STAT pathway.

(A) Control ovarioles exhibiting egg chambers with polyploid (large, DAPI-intense) nuclei characteristicof normal ogenesis.No HA-Phf7 expression is observed(A′′).

(B) Germline depletion of Sxl results in a tumorous ovary with small germ cells not organized into egg chambers that do not contain large, polyploid nuclei. The germline also now exhibits Phf7 expression as judged by anti-HA immunostaining (B′′).

(C–E) Ability of different gene knockdowns to rescue the Sxl loss-of-function phenotype in the ovary.

(C) Sxl RNAi combined with Phf7 RNAi. No rescue of the Sxl germline loss-of-function phenotype is observed, and the germline remains tumorous.

(D and E) Sxl RNAi combined with Stat92E RNAi (D) or dome RNAi (E). Note that these ovaries are rescued and appear similar to control ovaries (A) with differentiating egg chambers. Percent rescue and sample size are indicated in the panels. White dotted line shows example ovarioles. n indicates number of gonads analyzed for each group. Scale bar, 50 μm.

We did, however, observe rescue of the Sxl loss-of-function phenotype when we knocked down Stat92E in the germline (Figure 7D). While nos > SxlRNAi induces ovarian tumors in 100% of ovaries, simultaneous depletion of Stat92E was able to rescue egg chamber production in 20% of ovaries (n = 103). Similarly, RNAi of the JAK/STAT receptor domeless also rescued egg chamber production in 45% (n = 107) of Sxl loss-of-function ovaries (Figure 7E). This again indicates that regulation of the JAK/STAT pathway is a key function for Sxl in the female germline. However, while Phf7 is an important target for the JAK/STAT pathway that is essential for proper function of the male germline, prevention of Phf7 expression is not the only function for Sxl in the female germline, as downregulation of Phf7 does not rescue loss of Sxl function. Thus, there must be an additional factor or factors regulated by JAK/STAT that become active in the female germline upon loss of Sxl activity.

DISCUSSION

Here we present data that provide new insights into germline sex determination and the regulation of male versus female GSC identity. First, we find that one key function of the JAK/STAT pathway in GSCs is to promote male identity and directly activate expression of the male germline chromatin regulator Phf7. Further, we find that an important role for Sxl in female germ cells is to block the JAK/STAT pathway and prevent this signal from masculinizing the germline. Therefore, one key aspect of germline sexual identity is to regulate how GSCs respond to signals in their niche environment.

The role of the JAK/STAT pathway in male GSCs

Different findings have led to different conclusions about the role of the JAK/STAT pathway in male GSCs. When STAT activity is removed from individual GSCs, they are lost rapidly from the niche, indicating a role in GSC identity or maintenance (Kiger et al., 2001; Tulina and Matunis, 2001). However, when STAT is removed from all GSCs, they exhibit defects in niche adhesion but can otherwise function as GSCs (Leatherman and Dinardo, 2010), although GSC loss is also observed (Tarayrah et al., 2015; Chen et al., 2018). The JAK/STAT pathway has also been implicated in aging of GSCs and their niche (Lenhart et al., 2019). One interpretation of these diverse data would be that the JAK/STAT pathway is important for specific aspects of male GSC function, such as regulation of cell adhesion and the cell cycle, but it is not required for stem cell identity per se.

We propose a different role for the JAK/STAT pathway, which is to regulate GSC sexual identity. Previously we reported that the JAK/STAT pathway is important for establishing male identity in the embryonic germline (Wawersik et al., 2005). Here we show that one defect observed in XX germ cells present in a male soma is that they exhibit reduced JAK/STAT signaling (Figures 2B and 2F). Further, activation of the JAK/STAT pathway can partially rescue these XX germ cells, promoting a male identity and progression into spermatogenesis (Figures 2C, 2G, 2D, and 2H). Thus, we propose that the JAK/STAT pathway remains a key masculinizing signal for the germline throughout development and into adulthood. One possibility is that the JAK/STAT pathway regulates only GSC sex and that other roles, such as regulating a specific set of cell adhesion proteins, represent downstream consequences of altering sexual identity. Alternatively, the JAK/STAT pathway could regulate GSC sexual identity and other aspects of GSC behavior independently.

One important way in which the JAK/STAT pathway promotes a male identity in the germline is by activating the male sex determination factor Phf7. Previously, we have shown that Phf7 is important for male identity in the germline and proper spermatogenesis (Yang et al., 2012). Phf7 likely promotes male germline identity by acting as a chromatin “reader” and binding to histone H3 methylated at position K4 (Yang et al., 2012, 2017; Wang et al., 2019). Phf7 is also toxic to female germ cells, making the sex-specific regulation of Phf7 extremely important. Here we show that the JAK/STAT pathway is a direct regulator of Phf7 expression in both embryos and adults. STAT protein can bind to the Phf7 locus (Figure 5A), and consensus STAT binding sites near the male-biased promoter are essential for proper male expression of Phf7 and its ability to function in spermatogenesis (Figures 5B–5H, S7A, and S7B). Expression from the male-biased promoter is important in part because the transcript from the downstream, “female” promoter is subject to translational repression (Figure 6). Thus, Phf7 represents an important link between the JAK/STAT pathway and male identity in the germline.

The role of Sxl in the germline

Sxl acts as a key regulator of sex determination in both the soma and the germline, and it is necessary and sufficient to confer female identity. However, the role of Sxl in the germline has remained mysterious. In the soma, Sxl regulates sexual identity through tra and dosage compensation through msl-2 (Bell et al., 1988; Keyes et al., 1992; Bashaw and Baker, 1997; Kelley et al., 1997; Gebauer et al., 1998; Penalva and Sánchez, 2003), but these genes do not play a role in the germline. Instead, we have found that a key role of Sxl in the germline is to repress the JAK/STAT pathway in female germ cells.

Initially, only the male somatic gonad expresses ligands for the JAK/STAT pathway and is capable of promoting JAK/STAT activation in the germ cells (Wawersik et al., 2005). However, ligands for the JAK/STAT pathway eventually become active in the germarium of the ovary (López-Onieva et al., 2008), where they are important for the function or maintenance of the somatic escort cells (Decotto and Spradling, 2005). Sxl acts to repress JAK/STAT response in the female germ cells and thereby prevents activation of male-promoting factors such as Phf7. Somatic cells of the ovary such as the escort cells are still able to respond to these ligands and activate the JAK/STAT pathway, even though they also express Sxl. How Sxl is able to repress the JAK/STAT response in a germline-specific manner remains unknown, although the levels of Sxl appear higher in the GSCs than in the surrounding soma (Figure S1). However, the fact that an activated Hop (hopTum) can partially rescue the germline in XX males indicates that Sxl is repressing the pathway at the level of Hop or above. Interestingly, RNA for the JAK/STAT receptor domeless was identified in a pull-down experiment with Sxl, suggesting this could be a relevant target for regulation (Ota et al., 2017).

Our data support a model where the JAK/STAT pathway is important for activating male identity in the germline and expression of male genes such as Phf7, while this pathway is repressed in female germ cells by Sxl. Loss of Sxl from the female germline leads to both upregulation of JAK/STAT signaling and inappropriate expression of Phf7 (Figure 7) (Shapiro-Kulnane et al., 2015). In addition, suppression of the JAK/STAT pathway can partially rescue loss of Sxl in the female germline (Figures 7D and 7D′). Thus, regulation of the JAK/STAT pathway is one key aspect of how Sxl promotes female germline identity. However, we observed no ability for loss of Phf7 to rescue loss of Sxl from the female germline. This is in contrast to previously published results where loss of Phf7 was shown to rescue the female germline in sans fille mutants, which also primarily affects the germline by disrupting Sxl expression (Shapiro-Kulnane et al., 2015). As discussed earlier, we have now reduced Phf7 function by both RNAi and using null Phf7 mutants, in both Sxl and sans fille loss-of-function backgrounds and observed no rescue or modification of the germline defects present. We conclude that, while regulation of Phf7 by the JAK/STAT pathway and Sxl is clearly important for proper germline sexual development, ectopic expression of Phf7 is not the only defect present in Sxl mutant female germ cells; there must be additional targets for regulation by Sxl and JAK/STAT that are disrupted in Sxl mutants. In support of this view, loss of STAT from the male germline has a more severe phenotype than loss of Phf7 (Figures S4C–S4E′) (Yang et al., 2012). Previously, we have shown that expression of another male-promoting factor in the germline, Tdrd5l, is regulated by Sxl (Primus et al., 2019). While this regulation appears to be, at least in part, via Sxl acting on the Tdrd5l mRNA to influence levels of Tdrd5l protein, it is possible that Tdrd5l is also regulated at the transcriptional level as an additional target of the JAK/STAT pathway.

It is intriguing that Sxl acts as a negative regulator of the JAK/STAT pathway in both the soma and the germline but does so in different ways. In the soma, Sxl activates an alternative splicing cascade that leads to splicing of dsx in the female mode, creating the DSXF protein, while the DSXM protein is produced in males by default. An important sex-specific trait in the embryonic gonad is that male somatic cells produce ligands for the JAK/STAT pathway that activate JAK/STAT signaling specifically in male germ cells, and this is regulated in a manner dependent on dsx (Wawersik et al., 2005). Thus, in addition to being a negative regulator of JAK/STAT signal reception in the germline, Sxl acts as a negative regulator of JAK/STAT ligand production in the soma. Together, these independent aspects of regulation by Sxl combine to ensure that the masculinizing effects of the JAK/STAT pathway are restricted to male germ cells.

Germline sex determination

An important conclusion from this work is that germline sex determination regulates how GSCs communicate with their surrounding stem cell niche. Germline sex determination is regulated by both germline autonomous cues, based on the germline sex chromosome constitution, and non-autonomous signals from the soma. We have shown that the autonomous cues, acting through Sxl, regulate how signals from the niche are received and interpreted by the GSCs. In both the testis and ovary GSC cell niches, the JAK/STAT pathway is important for regulating somatic cells like the cyst stem cells in the testis (Leatherman and Dinardo, 2008; Sheng et al., 2009; Sinden et al., 2012) and the escort cells in the ovary (Decotto and Spradling, 2005). However, this pathway is only required in the male GSCs and not female GSCs (Kiger et al., 2001; Tulina and Matunis, 2001; Decotto and Spradling, 2005). We propose that it is essential to block JAK/STAT signaling in female GSCs to prevent their exposure to this masculinizing signal. Indeed, activation of the JAK/STAT signal is sufficient to promote male identity in XX germ cells (Figures 2A–2H), and removal of STAT is sufficient to partially rescue the defects observed in XX germ cells that have lost Sxl (Figures 7D and 7E). Thus, a key aspect of how Sxl promotes female identity in the germline is to prevent female GSCs from being masculinized by activators of the JAK/STAT pathway present in the niche environment.

It is important to note that, when we refer to the sex chromosome genotype affecting germline “sex determination,” this could result from any contribution of sex chromosome genotype to successful spermatogenesis or oogenesis. For example, if dosage compensation is incomplete or non-existent in the germline, then the presence of two X chromosomes will lead to increased X chromosome gene expression, which may be incompatible with male germline differentiation. Similarly, a single X chromosome dose may be incompatible with oogenesis. It is also possible that the number of X chromosomes present in the germline has additional affects besides the presence or absence of Sxl expression. While XX germ cells present in a male soma exhibit severe atrophy and loss (Figure 2B), the expression of Sxl in the male germline has a much weaker phenotype (Figures S4D). Thus, there may be additional consequences of sex chromosome genotype on germline function beyond that which is controlled by Sxl. A better understanding of what germline sexual identity means in Drosophila, in particular at the level of whole-genome gene expression levels, is required before we can assess the true contribution of germline sex chromosome constitution to germline sex determination. Further, how the effects of X chromosome number on germline sexual development in Drosophila relate to infertility observed in patients with disorders of sexual development such as Klinefelter’s and Turner’s syndromes remains to be investigated.

Limitations of the study

One limitation of this study is the relatively low frequency with which we are able to rescue the XX germline in tra mutants by downregulating Sxl or upregulating the JAK/STAT pathway. This could be due to technical limitations of the timing or level of expression of the reagents used. Alternatively, this could mean that there is another interesting defect in XX germ cells present in a male somatic environment besides that is caused by expression of Sxl and downregulation of the JAK/STAT pathway. Another limitation of the study is that the molecular target for Sxl in regulating the JAK/STAT pathway remains unknown. RNA-seq analysis of Bam mutant testes and ovaries suggested that hop RNA splicing is differentially regulated between males and females (data not shown). However, extensive experimental analysis failed to reveal a role for Sxl in regulating hop in the germline. Thus, this remains an important area for future research.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Mark Van Doren (vandoren@jhu.edu).

Materials availability

Flies and reagents generated in this study is available upon request and will be shared without restriction.

Data and code availability

All data generated and reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this work paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

Fly husbandry

Flies used in experiments were kept at 25°C. nanos-GAL4-VP16 driving UAS-Sxl and Stat92E-RNAi were crossed and raised at 29°C and aged for 2 weeks. Newly eclosed nos > Sxl flies were assayed for Stat92E levels while GSC loss phenotypes were assayed in flies aged 7–10 days post eclosion. RNAi was driven at 25C and flies were aged for 5 days.

Fecundity test

For males, newly eclosed single test males were mated to 15 virgin Oregon-R females for 1 week and number of progenies produced was recorded 14 days after cross started.

Phf7 UTR construct

5′, 3′UTR of Phf7 and 3 UTR of HSP70 were cloned into pUASP vector using the listed primers. 5′UTR were cloned in front of EGFP. pUASpB is a modified version of pUASP (Rørth, 1998) including an attB site for phiC31-mediated integration. Phf7 UTR constructs were generated by cloning a flexible linker sequence followed by the ORF of Phf7 (lacking a start codon) using the listed primers into UAS-sfGFP that had been linearized with Xba1 for 5′UTR cloning and with SpeI and Pst1 for 3′UTR cloning. Constructs were assembled using HiFi DNA Assembly (New England Biolabs).

EGFPEX0_fwd CCGCGGCCGCTCTAGCAGAAGCTCACAGGT.

EX05UTR_rev CAAAAAGCGTTGAATTCCCGA.

Male5UTRegfp_fwd-CGGGAATTCAACGCTTTTTGAACAGCAGTTTTAGGCAATTCGTGCCAACG.

Male5UTRegfp_rev-GCCCTTGCTCACCATG GATGCGTTTCCG.

EGFPFemale5UTR_fwd CCGCGGCCGCTCTAGGATTTGTT.

EGFPFemale5UTR_rev GCCCTTGCTCACCATG GATGCGTTTC.

HSP70B3UTRSPE1Fw-GGGCCCACTAGTCCAAATAGAAAATTATTCAGTTCCTG.

HSP70B3UTR PST1Rv- AATCGCTGCAGTATATTCTATTTATTAACCAAGTAGC.

Constructs flies were injected into embryos and integrated via PhiC31 integrase-mediated transgenesis (done at BestGene Inc., California) into the same genomic location at P[CaryP]attP40 on Chromosome II. For germline-specific overexpression, male flies carrying UAS transgenes were mated with nanos-GAL4:VP16 virgin females (Van Doren et al., 1998) and the crosses were maintained at 29°C. The progeny was reared at 29°C until 3–5 days post-eclosion (unless otherwise specified).

Construct, mutagenesis and BAC recombineering

All Phf7 reporter construct was made in Phf7-BAC (CH322–177L19, BACPAC Resources Center (Venken et al., 2009). It was recombineered to add 3xHA at C-terminus. The C-terminus tagged Phf7-BAC was inserted into PBac[yellow[+]-attP-3B]VK00033 and it successfully reports Phf7 expression (Yang et al., 2012).

The region of Phf7 carrying STAT92e binding sites was PCR amplified and cloned into PCR2.1-TOPO vector (Thermo Fisher). Site directed mutagenesis was carried out to mutate the 3 STAT92e binding sites. Galk recobineering method was used to clone back the fragment into Phf7-BAC-HA as described in (Warming et al., 2005).

For transgenesis these constructs were inserted into PBac[yellow[+]-attP-3B]VK00033 same as the control BAC for ideal comparisons of Phf7 expression.

STAT92e binding site recombineering

Region of Phf7 containing 3 STAT92e binding sites was PCR amplified and cloned into TA vector using primers below. Primers bind just outside where GALk primers end in Phf7 locus.

Phf7 TA 1 Fw-GGAATATTATTAAGCAAATGATCAAG.

Phf7 TA 1 Rv-TGTGCAATGAATTGTAACACAAA.

Sites were mutated with primers below.

| Primer Name | Primer sequence (5′ to 3′) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| t197a_t198a_t207a_t208a_antisense | 5′-TTACGGCAATTTTCGAGGTTATTCGTAGTTACAGA AATAAAACCGAGAGTTTGACGCTTG-3′ |

| t43a_t44a_antisense | 5′-CCACAAAACAAAATCTTCAACTGTTACCCGCCATG TTTTTGTTATGCT-3′ |

| t43a_t44a | 5′-AGCATAACAAAAACATGGCGGGTAACAGTTGAAGA TTTTGTTTTGTGG-3′ |

| t197a_t198a_t207a_t208a_ | 5′-CAAGCGTCAAACTCTCGGTTTTATTTCTGTAACTAC GAATAACCTCGAAAATTGCCGTAA-3′ |

Galk sequence was amplified by primers below.

Phf7 STAT 3n4n GALk 1 Fw.

TATAACATATATATATATATAGTTTGTAAGGTTTATGGGGTCGGAAACGCCCTGTTGACAATTAATCATCGGCA. Phf7 STAT 3n4n GALk Rv

tatatctacttgaaaaggcattaattagaacccctatacacatactttga TCAGCACTGTCCTGCTCCTT.

Mutated TA clone was used to substitute GALK in the vector. Protocol as outlined was used for galK recomineering (Warming et al., 2005).

Genotype of flies used in this paper

| Figure | Full genotype | Abbreviation used in Figure |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

|

S1A, S1C, S1G; 1C, 1I, 1E, 1F; 2A, 2E; S2A; 3A, 3D; S4A |

XY tra1/traD | XY tra |

|

S1B, S1D, S1F; 1D–1F, 1J; 2B, 2F; S2B; S4A |

XX tra1/traD | XX tra |

| S1E, 1B | w1118 | XX |

| S1H | XX tra1/traD; U2AF-TRAF | XY tra, U2AF-traF |

| 1A | w 1118 | XY |

| 1G, 1H | XY tra1/traD; esgM5−4, XX tra1/traD; esgM5−4 | XY tra,M5–4, XX tra,M5–4 |

| 2C, 2G; S2C, S2E; S3A; S4A | XX tra1/traD; hopTUM | XX tra, hopTUM |

| 2D, 2H; S2D, S2E; S3B; S4A | XX tra1/traD; nanos-GAL4-VP16; UAS-Stat92EΔNΔC | XX tra, nos > Stat92EΔNΔC |

| 3B, 3E | XX tra1/traD; nanos-GAL4-VP16 | XX tra, nosGAL4 |

| 3C, 3F; S3C; S4A | XX tra1/traD; nanos-GAL4-VP16; UAS-SxlRNAi | XX tra, nosGAL4> SxlRNAi |

| S4C | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; mcherryRNAi/+ | XY nos > mcherryRNAi |

| S4D | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; UAS-Sxl/+ | XY nos > UAS-Sxl |

| S4E | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; Stat92ERNAi/+ | XY nos > Stat92ERNAi |

| 4A | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; mcherryRNAi/+ | nos > controlRNAi |

| 4A | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; Stat92ERNAi/+ | nos > Stat92ERNAi |

| 4B, 4D | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; Phf7.HA/mcherryRNAi | nos > Phf7.HA/mcherryRNAi |

| 4C, 4E | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; Phf7.HA/Stat92ERNAi | nos > Phf7.HA/Stat92ERNAi |

| S6 | W; +/+; Phf7.HA.BAC | Phf7.HA |

| 5B, 5C, 5F, S7A, S7B | W; +/+; Phf7.HA.BAC | WT |

| 5B, 5D, 5G, S7A, S7B | W; +/+; Phf7.HA.BAC (with 3n3n sites mutated) | 3n3n |

| 5B, 5E, 5H, S7A, S7B | W; +/+; Phf7.HA.BAC (with 3n3n4n sites mutated) | 3n3n4n |

| 6A, 6B | W; +/+; Male 5′UTR-HSP-70 3′UTR | Long Male 5′UTR-HSP-70 3′UTR |

| 6C, 6D | W; +/+; Female 5′UTR-HSP-70 3′UTR | Short Female 5′UTR-HSP-70 3′UTR |

| 7A | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; Phf7.HA/mcherryRNAi | nos > mcherryRNAi |

| 7B | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/SxlRNAi; Phf7.HA/mcherryRNAi | nos > SxlRNAi/mcherryRNAi |

| 7D | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/SxlRNAi/+; Stat92ERNAi/+ | nos > SxlRNAi/Stat92ERNAi |

| 7C | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/SxlRNAi; Phf7RNAi/+ | nos > SxlRNAi/Phf7RNAi |

| 7E | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/SxlRNAi; domeRNAi/+ | nos > SxlRNAi/domeRNAi |

| S8A | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/+; mcherryRNAi/+ | nos > mcherryRNAi |

| S8B | w/; nos-GAL4-VP16/SxlRNAi; +/+ | nos > SxlRNAi |

METHOD DETAILS

Immunostaining

Embryo and larvae collection

Embryos and larvae were collected from agar plates, rinsed with PBT (PBS and 0.1% Triton) in a cell strainer. Embryos were dechorionated with 50% bleach for 5 min, rinsed with PBT and transferred to a vial, then fixed (8 mL heptane, 0.25 mL 37% paraformaldehyde, and 1.75 mL PEMS [100 mM PIPES, 2 mM MgSO4, 1 mm EGTA]) for 20 min with gentle agitation. The aqueous bottom layer was removed and 10 mL of methanol was added to the vial that was then shaken for 30–60 s. Most of the liquid and material at the interface was removed and embryos were washed with methanol three times. Embryos were rehydrated with PBT with two, 5-min washes and a final 30-min wash before being immunostained.

Newly eclosed larvae were collected and fixed much like embryos with some changes. They were quickly rinsed with 50% bleach for 1 min. After the initial 20-min fixation they were transferred to 4.5% PFA (containing 0.1% Tween) for an additional 5 min. They were processed through a dehydration series in methanol/PBS and stored. For immunostaining they were rehydrated through a series of methanol/PBS solutions.

Embryo immunostaining

Embryos were immunostained as follows: Samples were washed twice with PBT (for embryos Tween was used). Samples were briefly sonicated at lowest settings, resuspended in PBT and washed 3 times. Embryos were blocked with PBT containing 0.5% BSA and 2% normal goat serum for 30 min. Primary antibodies were added to the blocking solution for primary incubations lasting between 4 h at room temperature to overnight at 4°C. Stat92E antibody solutions were incubated for 1.5 days, alternating room temperature and 4C. Secondary antibody stains were performed following two PBT washes with antibodies diluted in the blocking solution above and incubations from 3 h at room temperature to overnight at 4°C. Samples were washed twice with PBT and then positioned on a slide in PBS. The PBS was wicked away and samples were mounted in DAPBO.

Embryos and larvae were genotyped using transgenic balancer chromosomes and sex chromosome constitution was determined using paternal (P[Dfd-lacZ-HZ2.7]) or (P[Dfd-YFP]). Adult sex chromosome constitution was determined by the Y chromosome insertion Bs or by staining with msl1 antibodies that label the X chromosome of XY (but not XX) flies.

Immunolocalization on adult gonads

Day 1

-

1

Dissect tissue in 1X PBS. Transfer to a 1.5 mL tube containing 1X PBS. If it’s a quick dissection <20mins. You don’t need ice.

-

2

If you will need more time, keep samples on ice.

-

3

Remove PBS and add fixative.

-

4

For Testes: Fix in 4.5% formaldehyde in PBTx, 20–30 min at room temp on nutator. 1 mL fixative: 125 ul formaldehyde36% + 875 ul PBTx.

For Ovaries: Fix in 5.14% formaldehyde in PBTx, 10–15 min at room temp on nutator. 1 mL fixative: 100 μl formaldehyde 36% + 600 ul PBTx PBTx: PBS with 0.1% Triton.

-

5

Rinse twice in PBTx - Wash twice 10 min in PBTx. Not getting rid of fix will affect your immunostain.

-

6

Block at least 30 min in PBTx + 0.5% BSA + 2% NGS (1 mL BBTx + 20 ul NGS). You can leave tissue in block overnight. Leaving the sample over the weekend (*adult gonads) hasn’t been shown to affect future steps.

-

7

Primary antibody overnight at 4C (or 2 h at room temp) in PBTx + 0.5% BSA + 2% NGS (0.5 mL BBTx + 10 ul NGS). For best images, do an overnight primary incubation. 300 ul volumes of primary antibody are commonly used.

Day 2

-

8

Rinse twice in PBTx - Wash twice 10 min in PBTx.

-

9

Secondary antibody 3 h at room temp (or overnight at 4°C) in PBTx + 0.5% BSA + 2% NGS. (0.5 mL BBTx + 10 ul NGS).

-

10

Rinse twice in PBTx - Wash twice 10 min in PBTx.

Store in PBS at 4°C.

-

11

Mount on slide in PBS. Dry PBS and replace by DABCO or Vectashield.

Immunolocalization on larval gonads

Day 1

-

1

Dissect tissue in 1X PBS. Transfer to a 1.5 mL tube containing 1X PBS. If it’s a quick dissection <20mins. You don’t need ice.If you will need more time, keep samples on ice.

-

2

Remove PBS and add fixative.

-

3

Fix in 5.14% formaldehyde in PBTx, 10–15 min at room temp on nutator. 1 mL fixative: 100 mL formaldehyde 36% + 600 ul PBTx PBTx: PBS with 0.1% Triton.

-

4

Rinse twice in PBTx - Wash twice 10 min in PBTx. Not getting rid of fix will affect your immunostain. The larval gonads willfloat. Be patient.

-

5

Block at least 30 min in PBTx + 0.5% BSA + 2% NGS (1 mL BBTx + 20 ul NGS). You can leave tissue in block overnight. Leaving the sample over the weekend (*adult gonads) hasn’t been shown to affect future steps.

-

6

Primary antibody overnight at 4C (or 2 h at room temp) in PBTx + 0.5% BSA + 2% NGS (0.5 mL BBTx + 10 ul NGS). For best images, do an overnight primary incubation. 300ul volumes of primary antibody are commonly used.

Day 2

-

7

Rinse twice in PBTx - Wash twice 10 min in PBTx.

-

8

Secondary antibody 3 h at room temp (or overnight at 4°C) in PBTx + 0.5% BSA + 2% NGS. (0.5 mL BBTx + 10 ul NGS).

-

9

Rinse twice in PBTx - Wash twice 10 min in PBTx.

Store in PBS at 4°C.

-

10

Mount on slide in PBS. Dry PBS and replace by DABCO or Vectashield.

Stat92E antibody solutions were incubated for 1.5 days, alternating room temperature and 4°C.

Antibodies

Antibodies used (unspecified stocks are from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank): chicken anti-Vasa (1:10000, Howard Lab), rabbit anti-Vasa(1:1000, Leatherman Lab) chicken anti-GFP(1:5000, Abcam), rabbit anti-LacZ (1:10000), rat anti-Ncadherin (1:12), mouse anti-Hts1B1 (1:4), rabbit anti-Stat92E (Montell Lab) (1:800, used in larvae and adults), rabbit anti-Stat92E (Hou Lab) (1:50, used on embryos), rabbit anti-SxlM18 (1:20), mouse anti-armadillo (1:100, DSHB), rat anti-HA (1:100, Roche Inc, used in embryos and adults), guinea pig anti-TJ 1:1,000 (J. Jemc).

Rescue of XX tra mutant testes were assessed by DAPI staining with more intense DAPI restricted to the germline in the apical tip of the testes. Visualization of sperm bundles was used to categorize testes as ‘differentiation to sperm’. Antibodies such as rat anti-Ncad or mouse anti-Hts1B1 allowed for this visualization.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation reaction was carried out in adult (3–5 day old) testis. About 200 pairs of testes (w1118; PBac [Stat92E-GFP.FLAG]VK00037) was subjected to ChIP according to (Tran et al., 2012). Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR green mix on AB7300 system.

Primers were designed from this region gatttatatacattcggctagcataacaaaaacatggcgggtttcagttgaagattttgttttgtggctgtctcaaaaaacacgtgtgccaattcaatgtaaagtcctgcacaaataat taaacagttggaaaaacgcttaggggcaaccctactgccagagttggcaagcgtcaaactctcggttttatttctgtttctacgaatttcctcgaaaattgccgtaacctggggcaaat gcgaattgaatgaaagttgcagtcctttattt

This covers all 3 STAT92e binding sites.

STAT-Phf7 chip Fw- TTCGGCTAGCATAACAAAAACA.

STAT-Phf7 chip Rv- GGACTGCAACTTTCATTCAATTC.

Thiredoxin Chip Fw-caaattcgcatgctgtcagt

Thiredoxin Chip Rv-ggctgctggctgttctttac

domechipFw2-atttccattcaaggggttcc

domechipRv2-actggcgtgcatgtgtgta

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Stat92E and Phf7.HA quantification

Confocal slices were analyzed with ImageJ software to attain average pixel intensity per GSC (multiple confocal slices). Background staining in each testis was measured and subtracted from the GSC average pixel intensity. The GSCs of a testis were then averaged together, creating a data point. Data points were also averaged to create a testis average for each genotype.

For Phf7.HA, confocal slices were analyzed with ImageJ software to attain average pixel intensity. Several cells in the germ cell (embryos) and GSC (for adults) from each gonad (testis/ovary) were measured and used to determine the average intensity for each condition.

Statistics

All quantitative experiments were evaluated for statistical significance using the software Graphpad Prism v5.0. For counts, means with standard deviations are displayed, and the statistical differences between mutant or RNAi-treated samples and controls were addressed using a Student’s two-tailed t test. Statistical significance was assayed using a two-sided Fisher’s exact test. Statistical significance was denoted as p < in respective figure legends. In all cases, the specific statistical test used, along with numbers and further statistical information, can be found in figure legends.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Antibodies | ||

| chicken anti-Vasa | Howard Lab | N/A |

| rabbit anti-Vasa | Leatherman Lab | N/A |

| rabbit anti-GFP | Abcam | Cat# Ab290; RRID: AB_303395 |

| rabbit anti-LacZ | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# JIE7; RRID: AB _528101 |

| rat anti-Ncadherin | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# DN-Ex #8; RRID: AB_528121 |

| mouse anti-Hts1B1 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# 1B1; RRID: AB_528070 |

| rabbit anti-Stat92E | Montell Lab | N/A |

| rabbit anti-Stat92E | Hou Lab | N/A |

| rabbit anti-SxlM18 | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# M18; RRID: AB_528464 |

| mouse anti-armadillo | Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank | Cat# N2 7A1; RRID:AB_528089 |

| rat anti-HA | Roche Inc | Cat# 3F10; RRID:AB_2314622 |

| guinea pig anti-TJ | J. Jemc Lab | N/A |

| Rabbit anti-STAT92E | Steven X. Hou Lab | N/A |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 405 conjugate | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A31553; RRID: AB_221604 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A11029; RRID: AB_2534088 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A11004; RRID: AB_2534072 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 633 conjugate | ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A21050; RRID: AB_2535718 |

| Goat anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H + L) secondaryantibody, Alexa Fluor 488 conjugate |

ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A11073; RRID: AB_2534117 |

| Goat anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate |

ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A11075; RRID: AB_2534119 |

| Goat anti-Guinea Pig IgG (H + L) secondary antibody, Alexa Fluor 633 conjugate |

ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A21105; RRID: AB_2535757 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) secondaryantibody, Alexa Fluor 568 conjugate |

ThermoFisher Scientific | Cat# A11011; RRID: AB_143157 |

|

| ||

| Chemicals, peptides and recombinant proteins | ||

|

| ||

| VECTASHIELD Mounting Medium | Vector Laboratories | Cat# H-1000; RRID: AB_2336789 |

|

| ||

| Deposited data | ||

|

| ||

| RNAseq (Raw and analyzed data) | Primus et al. (2019) | GEO: GSE198369 |

|

| ||

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

|

| ||

| D. melanogaster: hop Tum | E. Bach Lab | N/A |

| D. melanogaster: UAS-Stat92EΔNΔC | E. Bach Lab | N/A |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of Sxl: y[1] sc[*] v[1]; P TRiP.HMS00609attP2 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC:34393; FlyBase: FBtp0064874 |

| UAS-Sxl | J. Horabin Lab | N/A |

| P[UASpGFPS65CαTub84B]3, 68–77, esgM5–4 |

S. Dinardo Lab | N/A |

| U2AF-TRAF, traV2 | Tom Cline | N/A |

| UAS(T)-TKVACT (7A2) | M. O’Connor | N/A |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of STAT92E: w1118; PGD4492v43866 |

Vienna Drosophila Resource Center | VDRC: v43867, FlyBase: FBtp0031768 |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of STAT92E: PKK100519VIE-260B |

Vienna Drosophila Resource Center | VDRC: v106980, FlyBase: FBtp0041710 |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of STAT92E: y1 v1; PTRiP.HMS00035attP2 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 33637; FlyBase: FBtp0064659 |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of Phf7: y1 sc* v1 sev21; PTRiP.GL00455attP2 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 35807, FlyBase: FBtp0068608 |

| Phf7ΔN2, Phf7-BAC-HA | Yang et al. (2012) | N/A |

| Phf7-BAC-HA-3n3n, Phf7-BAC-HA 4n3n3n and Female Phf7–5′UTR-EGFP-HSP70–3′UTR |

This Study | N/A |

|

D. melanogaster: GFP tagged Stat92E from the native promoter: w1118; PBac[Stat92E-GFP. FLAG]VK00037 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 38670, FlyBase: FBtp0072276 |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of dome: y1 v1; PTRiP. HMJ21208attP40 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 53890, FlyBase: FBtp0091376 |

|

D. melanogaster: RNAi of mcherry: y[1] sc[*] v[1] sev[21]; Py[+t7.7] v[+t1.8] = VALIUM20-mCherryattP2 |

Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center | BDSC: 35785, FlyBase: FBtp0067879 |

|

| ||

| Oligonucleotides | ||

|

| ||

| See Table S1 | This paper | N/A |

|

| ||

| Software and algorithms | ||

|

| ||

| Zeiss LSM | Carl Zeiss Microscopy | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/downloads/lsm-5-series.html |

| Zen | Carl Zeiss Microscopy | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/int/products/microscope-software/zen.html |

| Prism 5 | Graph Pad | http://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| Illustrator CC 2021 | Adobe Inc | N/A |

Highlights.

Germline sex influences how germline stem cells respond to niche signals

JAK/STAT promotes male germline sexual identity by directly activating Phf7

Sxl acts in female germ cells to repress JAK/STAT and preserve female identity

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank VDRC, Vienna, and the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, Indiana, for flies; S. Hou (NCI), X. Chen (Johns Hopkins University), E. Bach (NYU), and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for antibodies; and Flybase (www.flybase.org) for essential information. We thank C. Pozmanter, A. Dove, and L. Grmai for comments on the manuscript. We thank Integrated Imaging Center at The Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, for imaging. This work was supported by NIH grants R01GM113001 and R01GM084356 (to M.V.D).

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2022.110620.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- Bachiller D, and Sanchez L. (1986). Mutations affecting dosage compensation in Drosophila melanogaster: effects in the germline. Dev. Biol. 118, 379–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bashaw GJ, and Baker BS (1997). The regulation of the Drosophila msl-2 gene reveals a function for Sex-lethal in translational control. Cell 89, 789–798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bell LR, Maine EM, Schedl P, and Cline TW (1988). Sex-lethal, a Drosophila sex determination switch gene, exhibits sex-specific RNA splicing and sequence similarity to RNA binding proteins. Cell 55, 1037–1046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackler AW (1965). The continuity of the germ line in amphibians and mammals. Annee Biol. 4, 627–635. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casper A, and Van Doren M. (2006). The control of sexual identity in the Drosophila germline. Development 133, 2783–2791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C, Cummings R, Mordovanakis A, Hunt AJ, Mayer M, Sept D, and Yamashita YM (2018). Cytokine receptor-Eb1 interaction couples cell polarity and fate during asymmetric cell division. Elife 7, e33685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Oh SW, Zheng Z, Chen HW, Shin HH, and Hou SX (2003). Cyclin D-Cdk4 and cyclin E-Cdk2 regulate the Jak/STAT signal transduction pathway in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 4, 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cline TW (1979). A male-specific lethal mutation in Drosophila melanogaster that transforms sex. Dev. Biol 72, 266–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Contrino S, Smith RN, Butano D, Carr A, Hu F, Lyne R, Rutherford K, Kalderimis A, Sullivan J, Carbon S, et al. (2012). modMine: flexible access to modENCODE data. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, D1082–D1088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Decotto E, and Spradling AC (2005). The Drosophila ovarian and testis stem cell niches: similar somatic stem cells and signals. Dev. Cell 9, 501–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deebel NA, Bradshaw AW, and Sadri-Ardekani H. (2020). Infertility considerations in klinefelter syndrome: from origin to management. Best Pract. Res.Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 34, 101480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekas LA, Cardozo TJ, Flaherty MS, McMillan EA, Gonsalves FC, and Bach EA (2010). Characterization of a dominant-active STAT that promotes tumorigenesis in Drosophila. Dev. Biol 344, 621–636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebauer F, Merendino L, Hentze MW, and Valcárcel J. (1998). The Drosophila splicing regulator sex-lethal directly inhibits translation of malespecific-lethal 2 mRNA. RNA 4, 142–150. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczy P, and DiNardo S. (1996). The germ line regulates somatic cyst cell proliferation and fate during Drosophila spermatogenesis. Development 122, 2437–2447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granadino B, Santamaria P, and Sanchez L. (1993). Sex determination in the germ line of Drosophila melanogaster: activation of the gene Sex-lethal. Development 118, 813–816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanratty WP, and Dearolf CR (1993). The Drosophila Tumorous-lethal hematopoietic oncogene is a dominant mutation in the hopscotch locus. Mol. Gen. Genet 238, 33–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DA, Binari R, Nahreini TS, Gilman M, and Perrimon N. (1995). Activation of a Drosophila Janus kinase (JAK) causes hematopoietic neoplasia and developmental defects. EMBO J. 14, 2857–2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hashiyama K, Hayashi Y, and Kobayashi S. (2011). Drosophila Sex lethal gene initiates female development in germline progenitors. Science 333, 885–888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilfiker-Kleiner D, bendorfer A, Hilfiker A, and Nöthiger R. (1994). Genetic control of sex determination in the germ line and soma of the housefly, Musca domestica. Development 120, 2531–2538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinson S, and Nagoshi RN (1999). Regulatory and functional interactions between the somatic sex regulatory gene transformer and the germline genes ovo and ovarian tumor. Development 126, 861–871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley RL, Wang J, Bell L, and Kuroda MI (1997). Sex lethal controls dosage compensation in Drosophila by a non-splicing mechanism. Nature 387, 195–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes LN, Cline TW, and Schedl P. (1992). The primary sex determination signal of Drosophila acts at the level of transcription. Cell 68, 933–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiger AA, Jones DL, Schulz C, Rogers MB, and Fuller MT (2001). Stem cell self-renewal specified by JAK-STAT activation in response to a support cell cue. Science 294, 2542–2545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman JL, and Dinardo S. (2008). Zfh-1 controls somatic stem cell self-renewal in the Drosophila testis and nonautonomously influences germline stem cell self-renewal. Cell Stem Cell 3, 44–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leatherman JL, and Dinardo S. (2010). Germline self-renewal requires cyst stem cells and stat regulates niche adhesion in Drosophila testes. Nat. Cell Biol 12, 806–811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart KF, Capozzoli B, Warrick GSD, and DiNardo S. (2019). Diminished Jak/STAT signaling causes early-onset aging defects in stem cell cytokinesis. Curr. Biol 29, 256–267.e53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López-Onieva L, Ferná ndez-Miñ á n A, and Gonzá lez-Reyes A. (2008). Jak/Stat signalling in niche support cells regulates dpp transcription to control germline stem cell maintenance in the Drosophila ovary. Development 135, 533–540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsh JL, and Wieschaus E. (1978). Is sex determination in germ line and soma controlled by separate genetic mechanisms? Nature 272, 249–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray (nee Southard) S. (2011). Investigations into the Drosophila Germline Stem Cell Niche (The Johns Hopkins University), PhD. [Google Scholar]

- Nöthiger R, Jonglez M, Leuthold M, Meier-Gerschwiler P, and Weber T. (1989). Sex determination in the germ line of Drosophila depends on genetic signals and inductive somatic factors. Development 107, 505–518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ota R, Morita S, Sato M, Shigenobu S, Hayashi M, and Kobayashi S. (2017). Transcripts immunoprecipitated with Sxl protein in primordial germ cells of Drosophila embryos. Dev. Growth Differ. 59, 713–723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penalva LO, and Sá nchez L. (2003). RNA binding protein sex-lethal (Sxl) and control of Drosophila sex determination and dosage compensation. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev 67, 343–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Primus S, Pozmanter C, Baxter K, and Van Doren M. (2019). Tudordomain containing protein 5-like promotes male sexual identity in the Drosophila germline and is repressed in females by Sex lethal. PLoS Genet. 15, e1007617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivas ML, Cobreros L, Zeidler MP, and Hombría JC (2008). Plasticity of Drosophila Stat DNA binding shows an evolutionary basis for Stat transcription factor preferences. EMBO Rep. 9, 1114–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rørth P. (1998). Gal4 in the Drosophila female germline. Mech. Dev 78, 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz C, Kiger AA, Tazuke SI, Yamashita YM, Pantalena-Filho LC, Jones DL, Wood CG, and Fuller MT (2004). A misexpression screen reveals effects of bag-of-marbles and TGF beta class signaling on the Drosophila male germ-line stem cell lineage. Genetics 167, 707–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüpbach T. (1982). Autosomal mutations that interfere with sex determination in somatic cells of Drosophila have no direct effect on the germline. Dev. Biol 89, 117–127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schüpbach T. (1985). Normal female germ cell differentiation requires the female X chromosome to autosome ratio and expression of sex-lethal in Drosophila melanogaster. Genetics 109, 529–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro-Kulnane L, Smolko AE, and Salz HK (2015). Maintenance of Drosophila germline stem cell sexual identity in oogenesis and tumorigenesis. Development 142, 1073–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng XR, Posenau T, Gumulak-Smith JJ, Matunis E, Van Doren M, and Wawersik M. (2009). Jak-STAT regulation of male germline stem cell establishment during Drosophila embryogenesis. Dev. Biol 334, 335–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sinden D, Badgett M, Fry J, Jones T, Palmen R, Sheng X, Simmons A, Matunis E, and Wawersik M. (2012). Jak-STAT regulation of cyst stem cell development in the Drosophila testis. Dev. Biol 372, 5–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A, Fuller MT, Braun RE, and Yoshida S. (2011). Germline stem cells. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol 3, a002642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky M. (1993). Sex determination in Drosophila: sis-b, a major numerator element of the X:A ratio in the soma, does not contribute to the X:A ratio in the germ line. Development 117, 763–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinmann-Zwicky M, Schmid H, and Nö thiger R. (1989). Cell-autonomous and inductive signals can determine the sex of the germ line of Drosophila by regulating the gene Sxl. Cell 57, 157–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturtevant AH (1945). A gene in Drosophila melanogaster that transforms females into males. Genetics 30, 297–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarayrah L, Li Y, Gan Q, and Chen X. (2015). Epigenetic regulator Lid maintains germline stem cells through regulating JAK-STAT signaling pathway activity. Biol. Open 4, 1518–1527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran V, Gan Q, and Chen X. (2012). Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) using Drosophila tissue. J. Vis. Exp 61, 3745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tulina N, and Matunis E. (2001). Control of stem cell self-renewal in Drosophila spermatogenesis by JAK-STAT signaling. Science 294, 2546–2549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Deusen EB (1977). Sex determination in germ line chimeras of Drosophila melanogaster. J. Embryol. Exp. Morphol 37, 173–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Doren M, Williamson AL, and Lehmann R. (1998). Regulation of zygotic gene expression in Drosophila primordial germ cells. Curr. Biol 8, 243–246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venken KJ, Carlson JW, Schulze KL, Pan H, He Y, Spokony R, Wan KH, Koriabine M, de Jong PJ, White KP, et al. (2009). Versatile P[acman] BAC libraries for transgenesis studies in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat. Methods 6, 431–434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Kang JY, Wei L, Yang X, Sun H, Yang S, Lu L, Yan M, Bai M, Chen Y, et al. (2019). PHF7 is a novel histone H2A E3 ligase prior to histone-to-protamine exchange during spermiogenesis. Development 146, dev175547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warming S, Costantino N, Court DL, Jenkins NA, and Copeland NG (2005). Simple and highly efficient BAC recombineering using galK selection. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, e36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]