Abstract

OBJECTIVE:

High quality child care positively affects long-term development in children and is a necessary support for parents who work or are in school. We assessed the association between child care setting and parents’ report of difficulties with ability to work and/or further their education (“child care constraints”) or material hardships among families with low incomes.

METHODS:

Cross-sectional data were analyzed from families in Minneapolis, MN with children aged six weeks to 48 months in child care from 2004 to 2017. Associations between child care setting (formal, informal relative, informal non-relative) and child care constraints or material hardships (household/child food insecurity, housing instability, energy instability) were examined.

RESULTS:

Among 1580 families, 73.8% used informal care. Child care subsidy and public assistance program participation were higher among families utilizing formal care. Compared to formal care, families using informal relative or non-relative care had 2.44 and 4.18 greater adjusted odds of child care constraints, respectively. Families with children in informal non-relative care had 1.51 greater adjusted odds of household food insecurity. There were no statistically significant associations between informal relative care and household or child food insecurity, and no associations between child care setting and housing instability or energy insecurity.

CONCLUSIONS:

Informal care settings−relative and non-relative−were associated with child care constraints, and informal non-relative care with household food insecurity. Investment to expand equitable access to affordable, high-quality child care is necessary to enable parents to pursue desired employment and education and reduce food insecurity.

Keywords: child care, child care constraints, food insecurity, low-income, material hardship

HIGH-QUALITY, STABLE NURTURING, inclusive, and affordable early education and care have been shown to positively affect children’s long-term development and educational attainment1−3 while simultaneously supporting parents who work or are in school.4 However, choosing and accessing appropriate child care can be difficult for families, particularly those who face interrelated barriers in meeting their wants and needs. While some parents may prefer child care by a relative, others may seek alternative arrangements with a friend, neighbor, or sitter.5 Parents may want a child care center close to home, work, or school, but issues of inadequate hours of operation, concerns about quality or safety, lack of diversity, cultural inclusion or services for children with disabilities, and high cost may factor into the decision.6,7

Child care expenses for infants and toddlers can consume, on average, more than a third of a family’s income in the United States, depending on care setting and geography.8 For families with low and moderate incomes, the national child care average cost can exceed their annual income.6,8 As a result, families may be forced to make trade-offs between child care and basic needs−such as buying enough food for an entire household.6 Yet to offset these costs, caregivers need to be able to work and/or further their education, which in turn requires them to have child care. These challenges are referred to as “child care constraints”−when caregivers have difficulty obtaining child care needed to work and/or attend school. Child care constraints have been associated with household material hardships and poor health among parents and their children.9,10

These myriad factors influence families’ access to and decision-making around care arrangements for their children. Given the significant financial impact of child care on families, we investigate whether the type of child care setting−formal settings such as child care centers, or informal settings with relatives, friends, or sitters−utilized by families living with low incomes is associated with their experiences of material hardships and with child care constraints. We hypothesize that families who use informal care settings will be more likely to experience child care constraints and material hardships compared to families who use formal care.

Methods

Study Sample

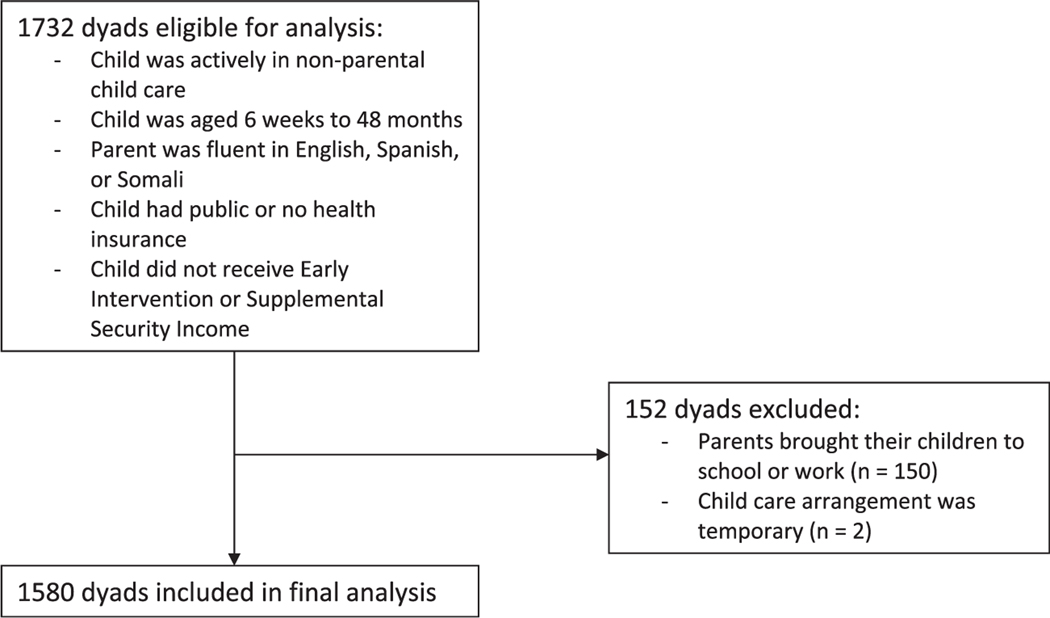

Data were collected as part of Children’s HealthWatch, an ongoing cross-sectional study monitoring the health and well-being of young children and caregivers11 in a pediatric primary care clinic in Minneapolis, Minnesota. Caregivers were overwhelmingly parents but also included a small number of grandparents and other caregivers; for simplicity, we refer to parents throughout. Initial eligibility criteria comprised children aged 6 weeks to 48 months with public or no health insurance (as a proxy for low-income status), residency in Minnesota, use of child care, and parent fluency in English, Spanish, or Somali. Because the study’s focus was on nonparental child care, households were excluded if the primary source of child care was a parent. Households were also excluded if the child received early intervention (EI) or Supplemental Security Income (SSI), which were considered eligibility markers for school-based early childhood special education programs. This resulted in a total sample size of 1732 parent-child dyads interviewed between January 1, 2004 and December 31, 2017. Dyads were further excluded if children were brought to parents’ school or work sites (n = 150) or if the child care arrangement was temporary (n = 2). In total, 1580 dyads were eligible for final analysis (Figure). The medical center’s institutional review board approved this study and renewed approval annually.

Figure.

Selection diagram of eligible parent-child dyads.

Measures

Parents reported birth mothers’ self-identified race and ethnicity (Hispanic; Black, non-Hispanic; White, non-Hispanic; Other) and nativity (US-born; foreign-born). Parents also reported age, marital status (single; partnered; separated/divorced/widowed), employment status (employed; not employed), and educational attainment (less than high school degree; high school degree or equivalent; technical school/college or higher), as well as the child’s breastfeeding history (ever breastfed; never breastfed), and current child health insurance (public insurance; no insurance). Children’s age and sex were obtained from medical records prior to the survey.

In Minnesota, family, friend, and neighbor care is referred to as “informal” care. “Formal” care indicates licensed child care settings, such as child care centers and family child care homes.12 Thus, the independent variable “child care setting” was defined with three categories: 1) formal care−−child was in a child care center or pre-school, family child care homes, or Head Start/Early Head Start; 2) informal relative care−−child was cared for by a relative in the parents’ own home, or in a relative’s home; and 3) informal non-relative care−−child was cared for by a neighbor, friend, or sitter. Parents reported the child care setting used most often, defined as at least once a week, each week, for the prior month.

The dependent variables were measures of child care constraints and household material hardship−−including food insecurity, housing instability, and energy insecurity. Child care constraints were defined by parents’ report of experiencing difficulties attending school and/or working due to problems obtaining child care.9 Household and child food insecurity status were defined by the 18-item US Food Security Survey Module, which includes house-hold-level and child-level questions assessing food security in the household over the past 12 months. Households were considered food insecure if parents responded affirmatively to three or more of the 18 household-level questions. Food insecurity among children was defined by parents’ affirmative responses to 2 or more of 8 child-level questions.13 Families were categorized as experiencing housing instability if they reported experience of at least one adverse housing condition: 1) being behind on rent or mortgage in the past year, 2) moving 2 or more times in the past year (multiple moves), and/or 3) homelessness within the child’s lifetime (living in a shelter, motel, temporary or transitional living situation, or scattered-site housing or no steady place to sleep at night).11 Households were considered energy insecure if families experienced having one or more of the following in the past year: 1) an actual or threatened shut-off of household utilities, 2) using a cooking stove for heat, and/or 3) one or more days without heat/cooling.14

Additional measures included parent report of average number of hours their child spent in child care, source of meals for their child while in child care, receipt of child care subsidy, and participation in other public assistance programs, including housing subsidies, energy assistance, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC), Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and/or Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF).

Analyses

Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the overall study sample by child care setting (formal care, informal relative care, informal non-relative care). Chi-square and analysis of variance, as appropriate, were used to assess differences between the three groups. Separate multivariable logistic regression models were performed to determine associations between child care setting and child care constraints or household material hardships. Covariates were chosen based on significant associations and a priori relationships (e.g., relationship of breastfeeding to employment, especially among families with low incomes).15,16 The model for all families was adjusted for child age and breastfeeding history; parent age, race and ethnicity, nativity, marital status, employment, and education. Additionally, multivariable logistic regression models were conducted stratified by race and ethnicity (among families with Black, non-Hispanic mothers, or Hispanic mothers), and by nativity (among families with US-born mothers or foreign-born mothers). Results were reported as adjusted odds ratios (aORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for all models, using a significance level of 0.05 for all hypothesis testing. All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the 1580 parents with young children in a child care setting, almost three-quarters reported using informal relative care (59.8%) or informal non-relative care (14.0%; Table 1). Parents with children in informal relative care or informal non-relative care were more frequently employed, had a partner, and did not have post-high school education when compared with those with children attending formal care. Additionally, a majority of children in informal relative care or informal non-relative care had mothers who were born outside of the United States, or identified as Hispanic. On average, children attending informal relative care (mean age 12.3 months) were younger than children informal care or informal non-relative child care (mean age 14.4 and 14.3 months, respectively). On average, children in the sample spent 29.5 hours per week in any child care setting.

Table 1.

Child and Caregiver Characteristics by Formal, Informal Relative, Informal Non-Relative Child Care; Minneapolis, MN: 2004−2017

| Total | Formal | Informal Relative | Informal Non-Relative | P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Characteristics | 1580 | 415(26.3) | 944 (59.7) | 221 (14.0) | |

| Child | |||||

| Sex | .19 | ||||

| Male | 804 (50.9) | 196 (47.2) | 489 (51.8) | 119(53.9) | |

| Female | 776 (49.1) | 219(52.8) | 455 (48.2) | 102 (46.1) | |

| Nativity | .13 | ||||

| Born in United States | 1554 (98.4) | 405 (97.6) | 933 (98.9) | 216(97.7) | |

| Born outside of United States | 25(1.6) | 10(2.4) | 10(1.1) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Age, mean ± SD, months | 13.1 ± 10.0 | 14.4 ± 10.2 | 12.3 ± 9.6 | 14.3 ± 10.7 | .0004 |

| Health insurance | .54 | ||||

| Public insurance | 1516(96.9) | 402 (96.9) | 903 (95.7) | 211 (95.5) | |

| No insurance | 64 (3.1) | 13(3.1) | 41 (4.3) | 10(4.5) | |

| Breastfeeding history | <.0001 | ||||

| Ever breastfed | 1152 (73.2) | 259 (62.6) | 698 (74.2) | 195 (89.5) | |

| Never breastfed | 421 (26.8) | 155 (37.4) | 243 (25.8) | 23 (10.5) | |

| Maternal | |||||

| Mother’s age, mean ± SD, years | 27.1 ± 6.1 | 26.7 ± 6.5 | 26.6 ± 5.9 | 29.8 ± 5.3 | <.0001 |

| Mother’s nativity | <.0001 | ||||

| Born in United States | 742 (47.1) | 296 (71.5) | 418(44.4) | 28 (12.7) | |

| Born outside of United States | 835 (52.9) | 118(28.5) | 524 (55.6) | 193 (87.3) | |

| Mother’s race and ethnicity | <.0001 | ||||

| Hispanic | 680 (43.9) | 44(10.8) | 479 (51.8) | 157 (72.4) | |

| Black, non-Hispanic | 703 (45.4) | 289 (71.0) | 359 (38.8) | 55 (25.3) | |

| White, non-Hispanic; and Other | 166(10.7) | 74 (18.2) | 87 (9.4) | 5 (2.3) | |

| Caregiver (Parent) | |||||

| Relationship to child | .22 | ||||

| Mother | 1492 (94.4) | 385 (92.8) | 898 (95.1) | 209 (94.6) | |

| Other | 88 (5.6) | 30 (7.2) | 46 (4.9) | 12(5.4) | |

| Marital status | <.0001 | ||||

| Single | 742 (47.2) | 242 (58.6) | 435 (46.3) | 65 (29.7) | |

| With a partner | 702 (44.7) | 149 (36.1) | 433 (46.1) | 120 (54.8) | |

| Separated/divorced/widowed | 128 (8.1) | 232 (5.3) | 72 (7.6) | 34 (15.5) | |

| Education level | <.0001 | ||||

| Less than high school degree | 528 (33.8) | 117(28.5) | 314(33.7) | 97 (44.5) | |

| High school degree or equivalent | 648 (41.5) | 163 (39.6) | 398 (42.7) | 87 (39.1) | |

| Technical school/college or higher | 385 (24.7) | 131 (31.9) | 220 (23.6) | 34 (15.6) | |

| Caregiver employment status | <.0001 | ||||

| Employed | 1097 (69.7) | 243 (58.7) | 661 (70.4) | 193 (87.3) | |

| Not employed | 477 (30.3) | 171 (41.3) | 278 (29.6) | 28 (12.7) | |

| Time per week in child care, mean ± SD, hours | 29.5 ± 12.3 | 30.6 ± 11.8 | 29.0 ± 12.8 | 29.1 ± 11.4 | .10 |

| Meals provided during child care | <.0001 | ||||

| Parent provides meals | 862 (59.2) | 111 (28.3) | 581 (68.0) | 170 (81.0) | |

| Child care provides meals | 333 (22.9) | 232 (59.2) | 90(10.6) | 11 (5.2) | |

| Both parent and child care provide meals | 245(16.8) | 45(11.5) | 172 (20.1) | 28 (13.3) | |

| No meals provided | 16(1.1) | 4(1.0) | 11 (1.3) | 1 (0.5) |

Note: Comparisons performed with Chi-square test of independence for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables.

On average, 80% of all households participated in WIC across all child care settings, with the highest enrollment percentage among families using informal non-relative care (88.2%; Table 2). Participation in SNAP, TANF, energy assistance, and housing subsidies was higher among households with children in formal care than informal relative care or non-relative care. One in four parents in the sample reported having a child care subsidy at the time of the survey; however, more households in formal care received subsidies (65.9%) compared to informal relative care (7.6%) or informal non-relative care (14.2%) settings (P < .0001).

Table 2.

Participation in Assistance Programs by Child Care Type

| Total | Formal | Informal Relative | Informal Non-Relative | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Assistance Program | 1580 | 415 (26.3) | 944 (59.8) | 221 (14.0) | |

| WIC | .004 | ||||

| Yes | 1303 (82.9) | 323 (78.2) | 786 (83.8) | 194 (88.2) | |

| No | 268 (17.1) | 90 (21.8) | 152 (16.2) | 26 (11.8) | |

| SNAP | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 640 (40.8) | 264 (64.1) | 306 (32.7) | 70 (32.1) | |

| No | 927 (59.2) | 148 (35.9) | 631 (67.3) | 148 (67.9) | |

| TANF | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 372 (23.7) | 176 (43.1) | 173 (18.4) | 23 (10.4) | |

| No | 1199 (76.3) | 232 (56.9) | 769 (81.6) | 198 (89.6) | |

| Energy assistance | .001 | ||||

| Yes | 78 (5.7) | 34 (9.3) | 40 (5.0) | 4 (2.1) | |

| No | 1284 (94.3) | 333 (90.7) | 765 (95.0) | 186 (97.9) | |

| Housing subsidy | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 227 (17.6) | 107 (30.9) | 92 (12.3) | 28 (15.4) | |

| No | 1066 (82.4) | 239 (69.1) | 673 (87.7) | 154 (84.6) | |

| Child care subsidy | <.0001 | ||||

| Yes | 349 (25.4) | 261 (65.9) | 58 (7.6) | 30 (14.2) | |

| No | 1023 (74.6) | 135 (34.2) | 707 (92.4) | 181 (85.8) |

Note: Comparisons performed with chi-square test of independence.

WIC indicates Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children; SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; and TANF, Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

Adjusted Analyses

Parents with children in informal relative care or non-relative care had higher risk of experiencing child care constraints ([aOR 2.44, 95% CI 1.69−3.55]; [aOR 4.18, 95% CI 2.57−6.78], respectively) compared to parents with children in formal care (Table 3a). Compared to children in formal care, children in informal non-relative care had increased adjusted odds of living in a food-insecure household (aOR 1.51, 95% CI 1.02−2.26). There were no statistically significant associations between informal relative care and household or child food insecurity. There were also no associations between child care settings and housing instability or energy insecurity.

Table 3a.

Child Care Constraints and Household Material Hardships Among Families Using Informal Relative and Informal Non-Relative Child Care, Compared With Formal Child Care

| Outcome | Informal Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value | Informal Non-Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced child care constraints (n = 1267) | 2.44 (1.69, 3.55) <.0001 | 4.18 (2.57, 6.78) <.0001 |

| Material Hardships | ||

| Child food insecurity (n = 1479) | 1.24 (0.86, 1.77) .25 | 1.58 (0.99, 2.51) .05 |

| Household food insecurity (n = 1479) | 0.99 (0.75, 1.32) .95 | 1.51 (1.02, 2.26) .04 |

| Housing instability (n = 1408) | 0.86 (0.65, 1.15) .32 | 1.00 (0.65, 1.55) .99 |

| Energy insecurity (n = 1155) | 1.11 (0.78, 1.56) .57 | 1.35 (0.75, 2.44) .32 |

Note: Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for child’s age, mother’s age, child breastfed, mother’s nativity, race and ethnicity, employment, marital status, education. N values indicate number of observations used in each model. Reference group: formal care.

Additionally, these models were stratified by race and ethnicity (Black, non-Hispanic, Hispanic), and nativity (US-born, foreign-born). Cell sizes for White, non-Hispanic and Other/Multiple Races, non-Hispanic mothers were too small to allow for stratified analysis. Black, non-Hispanic mothers with children in informal relative care or non-relative care had higher odds of experiencing child care constraints ([aOR 2.91, 95% CI 1.84−4.61]; [aOR 5.07, 95% CI 2.45, 10.48], respectively) compared to parents with children in formal care (Table 3b). Black, non-Hispanic mothers with children in informal non-relative care were also more likely to experience both household (aOR 2.23, 95% CI 1.15−4.33) and child (aOR 3.74, 95% CI 1.80−7.76) food insecurity. In this same group, there was also a borderline significant association (aOR 2.26, 95% CI 1.00−5.08) of increased odds of energy insecurity.

Table 3b.

Child Care Constraints and Household Material Hardships Among Families With Black, non-Hispanic Mothers Using Informal Relative and Informal Non-Relative Child Care, Compared With Formal Child Care

| Outcome | Informal Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-value | Informal Non-Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-value |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced child care constraints (n = 600) | 2.91 (1.84, 4.61) <.0001 | 5.07 (2.45, 10.48) <.0001 |

| Material Hardships | ||

| Child food insecurity (n = 664) | 1.48 (0.92, 2.39) .11 | 3.74 (1.80, 7.76) .0004 |

| Household food insecurity (n = 664) | 0.96 (0.66, 1.38) .81 | 2.23 (1.15, 4.33) .02 |

| Housing instability (n = 616) | 0.78 (0.54, 1.14) .20 | 1.49 (0.72, 3.11) .29 |

| Energy insecurity (n = 540) | 1.14 (0.76, 1.73) .53 | 2.26 (1.00, 5.08) .05 |

Note: Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for child’s age, mother’s age, child breastfed, mother’s nativity, employment, marital status, education. N values indicate number of observations used in each model. Reference group: formal care.

However, results were very different among families with Hispanic mothers (Table 3c). There was a borderline significant association (aOR 2.94, 95% CI 1.00−8.72) of child care constraints among Hispanic mothers using informal non-relative care compared to formal care. No other outcomes had significant associations. Among families with US-born and foreign-born mothers (Tables 3d and 3e) children in informal relative care or non-relative care had higher odds of experiencing child care constraints compared to those with children in formal care. US-born mothers with children in informal non-relative care had greater odds of child food insecurity (aOR 3.50, 95% CI 1.28−9.58) and foreign-born mothers with children in informal non-relative care had greater odds of household food insecurity, though the significance for the latter was borderline (aOR 1.72, 95% CI 0.99, 3.01), compared to those in formal care.

Table 3c.

Child Care Constraints and Household Material Hardships Among Families With Hispanic Mothers Using Informal Relative and Informal Non-Relative Child Care, Compared With Formal Child Care

| Outcome | Informal Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value | Informal Non-Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced child care constraints (n = 528) | 1.68 (0.60, 4.65) .32 | 2.94 (1.00, 8.72) .05 |

| Material Hardships | ||

| Child food insecurity (n = 655) | 0.71 (0.35, 1.45) .35 | 0.85 (0.38, 1.90) .69 |

| Household food insecurity (n = 655) | 0.75 (0.38, 1.46) .39 | 1.13 (0.53, 2.40) .75 |

| Housing instability (n = 643) | 1.20 (0.56, 2.58) .63 | 1.53 (0.65, 3.63) .33 |

| Energy insecurity (n = 474) | 0.85 (0.25, 2.94) .80 | 1.03 (0.24, 4.36) .97 |

Note: Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for child’s age, mother’s age, child breastfed, mother’s nativity, employment, marital status, education. N values indicate number of observations used in each model. Reference group: formal care.

Table 3d.

Child Care Constraints and Household Material Hardships Among Families With US-born Mothers Using Informal Relative and Informal Non-Relative Child Care, Compared With Formal Child Care

| Outcome | Informal Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value | Informal Non-Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced child care constraints (n = 636) | 2.34 (1.48, 3.70) .0003 | 4.88 (1.85, 12.87) .0014 |

| Material Hardships | ||

| Child food insecurity (n = 704) | 1.38 (0.85, 2.25) .19 | 3.50 (1.28, 9.58) .01 |

| Household food insecurity (n = 704) | 0.91 (0.64, 1.29) .60 | 1.46 (0.60, 3.53) .40 |

| Housing instability (n = 652) | 0.87 (0.62, 1.23) .44 | 0.93 (0.37, 2.33) .88 |

| Energy insecurity (n = 584) | 1.01 (0.68, 1.48) .98 | 1.06 (0.35, 3.17) .92 |

Note: Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for child’s age, mother’s age, child breastfed, race and ethnicity, employment, marital status, education. N values indicate number of observations used in each model. Reference group: formal care.

Table 3e.

Child Care Constraints and Household Material Hardships Among Families With Foreign-Born Mothers Using Informal Relative and Informal Non-Relative Child Care, Compared with Formal Child Care

| Outcome | Informal Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value | Informal Non-Relative: aOR (95% CI) P-Value |

|---|---|---|

| Experienced child care constraints (n = 631) | 2.93 (1.48, 5.81) .002 | 4.99 (2.42, 10.30) <.0001 |

| Material Hardships | ||

| Child food insecurity (n = 775) | 0.99 (0.57, 1.70) .97 | 1.25 (0.69, 2.27) .46 |

| Household food insecurity (n = 775) | 1.06 (0.64, 1.75) .83 | 1.72 (0.99, 3.01) .05 |

| Housing instability (n = 756) | 0.93 (0.52, 1.66) .80 | 1.21 (0.64, 2.29) .56 |

| Energy insecurity (n = 571) | 1.72 (0.78, 3.79) .18 | 2.11 (0.87, 5.10) .10 |

Note: Adjusted logistic regression models controlled for child’s age, mother’s age, child breastfed, race and ethnicity, employment, marital status, education. N values indicate number of observations used in each model. Reference group: formal care.

Discussion

Among a sample of low-income families with young children living in Minnesota, a majority utilized informal relative or non-relative child care settings rather than formal child care settings. Program participation in public assistance programs, with the exception of WIC, and use of child care subsidies was overall higher among households with children in formal child care settings. Parents with children utilizing informal relative care or non-relative child care were more likely to experience child care constraints while working or pursuing more education. Analyses exploring differences by race and ethnicity and nativity consistently found that those using informal relative and informal non-relative care were more likely to report child care constraints, with the exception of families with Hispanic mothers, among whom only informal non-relative care was associated with child care constraints. Additionally, families with children utilizing informal non-relative care were more likely to experience household food insecurity than those enrolled in formal child care, also noted among families with immigrant mothers. Child food insecurity was significantly associated with informal non-relative care among families with Black, non-Hispanic mothers and US-born mothers.

While some parents prefer to utilize informal−−relative or non-relative−−child care for many reasons, including the desire for their child to be with family or in a more intimate setting, others utilize informal care solutions as an alternative to formal care settings due to difficulty accessing appropriate, affordable, and high-quality care in formal, licensed child care settings. This study’s findings suggest that the use of informal child care settings may be a marker for further challenges with both consistent child care access and food insecurity.

Beyond affordability, barriers to accessing child care can include hours of operation that do not meet parent needs. Parents who utilized informal care were more frequently employed than those in formal care. Given this predominantly low-income population, we hypothesize that these parents using informal care have nonstandard work schedules, low-wage jobs, and/or other extenuating reasons contributing to their choices. Nonstandard work schedules, such as late evenings or overnight shifts, often preclude parents from using child care settings with standard operating hours. Few child care centers offer this flexibility. In a national survey, only eight percent of center-based child care providers offered any type of care during nonstandard hours.17 Additionally, low-wage jobs, such as in the service industry, often require work during nonstandard hours, and parents in these occupations may face challenges in affording and scheduling sufficient hours of child care to work the schedules they desire.10,18,19 As a result, they may need to rely upon informal relative care or informal non-relative child care settings to accommodate their work schedule and budget. These constraints are worrisome, given their known associations with material hardships, ceasing breastfeeding, and poor health in families.9,10,20,21

One way to overcome affordability barriers to formal child care is by subsidizing a portion of the cost through a child care subsidy (also known as a voucher). In this study, parent receipt of a child care subsidy was dramatically different between formal care and informal relative or non-relative child care settings. In Minnesota, qualifying parents can choose to use a subsidy to offset costs for either formal care such as a child care center, or informal care such as family and friends who meet the state’s quality assurance requirements.11 Given that parents with children in formal care more often had a subsidy, parents may be more likely to choose formal child care if they have the necessary financial support to do so. These parents’ choices may be due to the known benefits of child care centers compared to informal care settings, including healthier eating habits.22 Additionally, others have reported that children of mothers with depression enrolled in child care had fewer symptoms of depression, anxiety, and behavior problems compared to those who remained at home.23,24 Although guidelines for quality in informal child care are not yet established, there is potential to also invest in support for informal settings to reach the same quality standards required of formal settings so that families can have a variety of high-quality options to apply their subsidies.

While subsidies support access to high-quality care, a child care subsidy program is currently not an entitlement, with which a qualified recipient has a legal right to the benefit. Instead, the amount of appropriated funding by federal and state governments determines the number of families who can receive a subsidy. In 2017, our sample’s final year of data, an estimated 13.5 million children nationally were eligible under federal rules, yet only 1.9 million−−approximately 14%−−received subsidies.25 Regardless of parents’ choice of formal versus informal child care settings, subsidies can promote family stability and employment. For example, research shows that subsidies promote employment and reduce work disruptions due to child care constraints among single mothers.26,27 In addition, child care subsidy receipt may enable families with low incomes to afford other basic needs more easily, as they are required to pay less of their limited budget for care. Given these benefits, subsidies should be converted to an entitlement and expanded with equitable implementation to ensure all families in need of child care assistance are able to access benefits.

Our study found that food insecurity was associated with informal non-relative child care settings, suggesting a degree of economic distress among these families. This is concerning, given known consequences of food insecurity over the lifespan, such as poor child and adult physical and mental health outcomes.28,29 Families using informal non-relative care may not have shared resources (such as meals and snacks) from surrounding relatives upon which to draw. Additionally, they may not benefit from meals and snacks in formal child care for families with low incomes (through the federal Child and Adult Care Food Program), thus offsetting the cost of providing at least 1−2 meals per day. Since we found that these same families had greater odds of child care constraints, barriers to working or attending classes as desired may also exacerbate material hardships such as food insecurity. This study found that household food insecurity was the primary material hardship significantly associated with child care setting choice, which may indicate that the food budget is the easiest to stretch.

Concerning overall participation in public assistance programs such as SNAP, energy assistance and housing subsidies, families with low incomes using formal child care settings may be more connected to opportunities to participate in assistance programs, though housing subsidies, like child care subsidies, are also not an entitlement and participation is thus lower. Notably, WIC participation was highest among families using informal non-relative care. This may be specific to Minnesota’s wider range of income eligibility guidelines for WIC, which includes slightly higher-earning working-class families (185%−275% of the federal poverty level [FPL]).30 We hypothesize that families using informal relative and non-relative child care may have income levels above eligibility thresholds for other public assistance programs, including child care subsidies, and nevertheless cannot afford to pay full price for formal child care.31

Notably, there was only one borderline significant association between informal non-relative child care and child care constraints among families with Hispanic mothers and no other associations. Hispanic families are more likely to live in multigenerational households,32 which may confer protective factors for some material hardships. Lastly, there was a greater prevalence of mothers born outside of the United States among children in informal compared to formal child care settings. Many immigrant families face preexisting structural barriers to enrollment in formal care, such as limited English proficiency and bureaucratic complexity, and may also have a cultural preference for relative care.33 Furthermore, some immigrant families may not have enrolled in public assistance programs, including child care subsidies, due to ineligibility based on immigration status and/or fears related to immigration policy, which were especially exacerbated during the end of our study period.34 In line with our prior work,35 results showed increased odds of household food insecurity among immigrant households using informal non-relative care. These findings were based in one geographic location and the data did not have further disaggregation into Black and Hispanic subgroups. Future research using a larger and more granular dataset may reveal nuances about the intersections of nativity and race and ethnicity and how these differences may shape child care choices.

While this study was conducted before the COVID-19 pandemic, the resulting health and economic crises have underscored the critical role that child care plays in families’ ability to participate in the economy and for children to have a safe, nurturing environment in which to develop optimally.36 Moreover, the economic crisis precipitated by the pandemic has demonstrated how inadequate our national investment in this vital infrastructure is, with many child care providers forced to close temporarily or permanently in the wake of the economic downturn, further increasing barriers to access.37 Difficulty rehiring child care workers due to low wages has contributed to ongoing shortages of formal child care slots.38 Perception of greater provider stability may influence some families’ choice of informal child care. Meanwhile, our study has identified the additional circumstances of child care constraints and food insecurity among families who utilize informal child care settings. In line with the American Academy of Pediatrics’ (AAP) recommendations,39,40 our study highlights the need for increased state and federal investment in child care, both in expanding families’ access to formal child care settings while also devoting efforts to leverage community partnerships to provide early educational and food resources to informal child care providers. These efforts will support the healthy development of young children, enable parents to work or attend school, and improve the financial stability of families and child care providers.9

Limitations and Strengths

This study’s strengths include the uniquely large, sentinel, racially and ethnically diverse sample of families with young children, containing detailed data on child care utilization and material hardships, often lacking in other early childhood datasets.

The study was limited to one urban site in Minnesota before the COVID-19 pandemic, and the results may not be generalizable to other regions in the United States. There is a lack of nationally standardized definitions for family, friend and neighbor care settings, and the regulation of family daycare settings varies by state.41 We used Minnesota’s definition to place family daycares in the spectrum of formal care rather than informal non-relative care, though this may not apply to family daycares in other states. We had incomplete income data for some families, so we were unable to determine if there were specific income levels that may have been a marker for child care selection. However, we know that families in this sample likely had a maximum household income of 275% FPL, the maximum income eligibility for public insurance in Minnesota in both 2004 and 2017. These years encompass the start and end of the study period.42,43 Immigration status and other unmeasured confounders could also affect families’ enrollment in child care. Individual outcomes had varying sample sizes due to missing or incomplete data. Because this study had a cross-sectional design, the findings demonstrate association, not causation, between child care settings and child care constraints and food insecurity.

Conclusions

The findings of this study show that child care plays an essential role in both the stability and economic security of low-income families. The AAP has recommended that public policy efforts, such as funding and improving high-quality early childhood programs and providing child care subsidies for working families with low incomes, are a necessary investment to protect the health of children in poverty.39 The COVID-19 pandemic has further laid bare the critical need for a robust child care infrastructure for parents to participate in the economy and for children to thrive in an optimal, nurturing learning environment. Recognition of the role of child care to support parents’ ability to advance economic stability and meet basic needs and while also meeting a child’s need for appropriate early education experiences should drive significant investment in making all formal and informal child care settings equitable in access, affordability, and high quality standards for families with low incomes.

WHAT’S NEW.

Parents of children in formal child care experience fewer child care related limitations in their ability to work and/or further their education and greater food security. Access to affordable, high-quality child care provides two-generation support to both parent and child.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Deborah A. Frank, MD, Megan Sandel, MD, MPH, Richard Sheward, MPP, and Allison Bovell-Ammon, M. Div for reviewing earlier versions of this article. The authors would also like to acknowledge Sharon M. Coleman, MS, MPH for providing statistical expertise and Caroline J. Kistin, MD, MSc for providing assistance in analysis during in study. Finally, the authors would like to thank the families of Minneapolis, MN who participated in this study.

Funding:

Dr. Nguyen was funded by an institutional grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration (T32HP10028) and the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (1UL1TR0011430). The work of Children’s HealthWatch is supported by private foundations and generous donors. A complete list of supporters is available at www.childrenshealthwatch.org. The funders had no involvement in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, in the writing of the article, and in the decision to submit for publication.

References

- 1.Camilli G, Vargas S, Ryan S, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of early education interventions on cognitive and social development. Teach Coll Rec. 2010;112:579–620. 10.1177/016146811011200303. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Laurin JC, Geoffroy M-C, Boivin M, et al. Child care services, socioeconomic inequalities, and academic performance. Pediatrics. 2015;136:1112–1124. 10.1542/peds.2015-0419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Black MM, Walker SP, Fernald LC, et al. Advancing early childhood development: from Science to Scale 1: early childhood development coming of age: science through the life course. Lancet. 2017;389:77–90. 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31389-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Olivetti C, Petronlogo B. The economic consequences of family policies: lessons from a century of legislation in high-income countries. Published January 2017. Accessed February 9, 2019. https://www.nber.org/papers/w23051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Susman-Stillman A, Banghart P. Demographics of family, friend, and neighbor child care in the United States. Published August 2008. Accessed February 4, 2019. https://www.nccp.org/publication/demographics-of-family-friend-and-neighbor-child-care-in-the-united-states/. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Child Care Aware of America. The US and the high cost of childcare: an examination of a broken system. Published 2019. Accessed June 17, 2021. https://usa.childcareaware.org/priceofcare.

- 7.Congressional Budget Office. Factors affecting the labor force participation of people ages 25 to 54. Published February 2018. Accessed June 17, 2021. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/53452.

- 8.Gould E, Cooke T. High quality child care is out of reach for working families. Published October 6, 2015. Accessed March 6, 2019. https://www.epi.org/publication/child-care-affordability/. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bruce C, Bovell-Ammon A, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Access to high-quality, affordable child care: strategies to improve health. Published April 2020. Accessed May 28, 2020. https://childrenshealthwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/CHW-Childcare-Report-final-web-3.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Coleman-Jensen AJ. Working for peanuts: nonstandard work and food insecurity across household structure. J Fam Econ Issues. 2011;32:84–97. 10.1007/s10834-010-9190-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sandel M, Sheward R, Ettinger de Cuba S, et al. Unstable housing and caregiver and child health in renter families. Pediatrics. 2018;141: e20172199. 10.1542/peds.2017-2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Minnesota Department of Human Services. Do you need help paying for child care? Accessed February 4, 2019. https://edocs.dhs.state.mn.us/lfserver/Public/DHS-3551-ENG.

- 13.Coleman-Jensen A, Rabbitt MP, Gregory C, et al. Household food security in the United States in 2018. Published September 2019. Accessed January 2, 2020. https://www.ers.usda.gov/publications/pub-details/?pubid=94848. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cook JT, Frank DA, Casey PH, et al. A brief indicator of household energy security: associations with food security, child health, and child development in US infants and toddlers. Pediatrics. 2008;122: e867–e875. 10.1542/peds.2008-0286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Batan M, Li R, Scanlon K. Association of child care providers breastfeeding support with breastfeeding duration at 6 months. Matern Child Health J. 2013;17:708–713. 10.1007/s10995-012-1050-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mirkovic KR, Perrine CG, Scanlon KS, et al. Maternity leave duration and full-time/part-time work status are associated with US mothers’ ability to meet breastfeeding intentions. J Hum Lact. 2014;30:416–419. 10.1177/0890334414543522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.National Survey of Early Care and Education Project Team. Fact sheet: provision of early care and education during non-standard hours. .. Published April Accessed November 2, 2021; http://www.acf.hhs.gov/programs/opre/research/project/national-survey-of-early-care-andeducation-nsece-2010-2014.

- 18.Butcher KF, Schanzenbach DW. Most workers in low-wage labor market work substantial hours, in volatile jobs. Published July 24, 2018. Accessed January 28, 2021. https://www.cbpp.org/research/poverty-and-inequality/most-workers-in-low-wage-labor-market-work-substantial-hours-in. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golden L. Irregular work and its consequences. Published April 9, 2015. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.epi.org/publication/irregular-work-scheduling-and-its-consequences. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Strategy 6. Fact sheet: support for breastfeeding in early care and education. Published January 2019. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/pdf/strategy6-support-breastfeeding-early-care.pdf.

- 21.Schafer EJ, Livingston TA, Roig-Romero RM, et al. Breast Is Best, But.. .” according to childcare administrators, not best for the childcare environment. Breastfeed Med. 2021;16:21–28. 10.1089/bfm.2020.0078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee R, Zhai F, Han W-J, et al. Head Start and children’s nutrition, weight, and health care receipt. Early Child Res Q. 2013;28:723–733. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Giles LC, Davies MJ, Whitrow MJ, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and child care during toddlerhood relate to child behavior at age 5 years. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e78–e84. 10.1542/peds.2010-3119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Herba CM, Tremblay RE, Boivin M, et al. Maternal depressive symptoms and children’s emotional problems: can early child care help children of depressed mothers? JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70:830–838. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.1361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.The US Government Accountability Office. Child care: subsidy eligibility and receipt, and wait lists. Published February 18, 2021. Accessed November 2, 2021. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-21-245r.

- 26.Blau D, Tekin E. The determinants and consequences of child care subsidies for single mothers in the USA. J Popul Econ. 2007;20: 719–741. 10.1007/s00148-005-0022-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Forry ND, Hofferth SL. Maintaining work: the influence of child care subsidies on child care-related work disruptions. J Fam Issues. 2011;32:346–368. 10.1177/0192513X10384467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rose-Jacobs R, Black MM, Casey PH, et al. Household food insecurity: associations with at-risk infant and toddler development. Pediatrics. 2008;121:65–72. 10.1542/peds.2006-3717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gundersen C, Ziliak JP. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. 2015;34:1830–1839. 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Minnesota Department of Health. Am I eligible for WIC? WIC income guidelines. Accessed November 2, 2021. https://www.health.state.mn.us/people/wic/eligibility.html.

- 31.Roll S, East J. Financially vulnerable families and the child care cliff effect. J Poverty. 2014;18:169–187. 10.1080/10875549.2014.896307. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cohn D and Passel JS. Pew Research Center. A record 64 million Americans live in multigenerational households. Published April 5, 2018. Accessed June 22, 2020. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/05/a-record-64-million-americans-live-in-multigenerational-households/. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karoly LA, Gonzalez GC. Early care and education for children in immigrant families. Futur Child. 2011;21:71–101. 10.1353/foc.2011.0005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barofsky J, Vargas A, Rodriguez D, et al. Spreading fear: The announcement of the public charge rule reduced enrollment in child safety-net programs. Health Aff. 2020;39:1752–1761. 10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chilton M, Black MM, Berkowitz C, et al. Food insecurity and risk of poor health among US-born children of immigrants. Am J Public Health. 2009;99:556–562. 10.2105/AJPH.2008.144394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. Childcare: an essential industry for economic recovery. Published September 2020. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/sites/default/files/media-uploads/EarlyEd_Minis_Report3_090320.pdf.

- 37.Malik R, Hamm K, Lee WF, et al. The coronavirus will make child care deserts worse and exacerbate inequality. Published June 22, 2020. Accessed April 1, 2021. https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/early-childhood/reports/2020/06/22/486433/coronavirus-will-make-child-care-deserts-worse-exacerbate-inequality/. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rockeman O and Pickert R. Child-care workers are quitting the industry for good in the U.S. Published April 27, 2022. Accessed June 22, 2022. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-04-27/child-care-workers-are-quitting-the-industry-for-good-in-the-u-s. [Google Scholar]

- 39.AAP Council on Community Pediatrics. Poverty and child health in the United States. Pediatrics. 2016;137. 10.1542/peds.2016-0339. e20160339-e20160339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hartline-Grafton H, Hassink SG. Food insecurity and health: practices and policies to address food inseurity among children. Acad Pediatr. 2021;21:205–210. 10.1016/j.acap.2020.07.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hatfield BE, Hoke K. Family, friend, and neighbor care: status of states’ support for FFN care. Published August 18, 2016. Accessed February 4, 2019. https://oregonearlylearning.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/FFN-State-Report-FINAL.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chun R, Punelli D. Minnesota family assistance - a guide to public programs providing assistance to Minnesota families. Published January 2004. Accessed October 21, 2021. https://www.leg.mn.gov/docs/2004/other/040093.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minnesota Department of Human Services. The Children’s Health Insurance Program in Minnesota. Updated December 1, 2017. Accessed September 29, 2019. https://mn.gov/dhs/assets/chip-fact-sheet_tcm1053-311322.pdf.