Abstract

Voltage-gated sodium channel 1.7 (Nav1.7) remains one of the most promising drug targets for pain relief. In the current study, we conducted a high-throughput screening of natural products in our in-house compound library to discover novel Nav1.7 inhibitors, then characterized their pharmacological properties. We identified 25 naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids (NIQs) from Ancistrocladus tectorius to be a novel type of Nav1.7 channel inhibitors. Their stereostructures including the linkage modes of the naphthalene group at the isoquinoline core were revealed by a comprehensive analysis of HRESIMS, 1D, and 2D NMR spectra as well as ECD spectra and single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis with Cu Kα radiation. All the NIQs showed inhibitory activities against the Nav1.7 channel stably expressed in HEK293 cells, and the naphthalene ring in the C-7 position displayed a more important role in the inhibitory activity than that in the C-5 site. Among the NIQs tested, compound 2 was the most potent with an IC50 of 0.73 ± 0.03 µM. We demonstrated that compound 2 (3 µM) caused dramatical shift of steady-state slow inactivation toward the hyperpolarizing direction (V1/2 values were changed from −39.54 ± 2.77 mV to −65.53 ± 4.39 mV, which might contribute to the inhibition of compound 2 against the Nav1.7 channel. In acutely isolated dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, compound 2 (10 μM) dramatically suppressed native sodium currents and action potential firing. In the formalin-induced mouse inflammatory pain model, local intraplantar administration of compound 2 (2, 20, 200 nmol) dose-dependently attenuated the nociceptive behaviors. In summary, NIQs represent a new type of Nav1.7 channel inhibitors and may act as structural templates for the following analgesic drug development.

Keywords: Nav1.7 channel, naphthylisoquinolines, Ancistrocladus tectorius, dorsal root ganglion neurons, formalin-induced mouse inflammatory pain model, analgesics

Introduction

Voltage-gated sodium (Nav) channels are responsible for the initiation and propagation of action potentials, which transmit nociceptive signals from the peripheral nervous system (PNS) to the central nervous system (CNS) under pain conditions [1, 2]. Inhibition of Nav channels, especially for those distributed in the PNS, can dampen action potential firings and thereby relieve the pain with reduced side effects on the CNS [3]. Depending on the difference of α-subunit, Nav channels can be divided into nine subtypes (Nav1.1–Nav1.9) [4]. Nav1.7, which is predominantly distributed in the peripheral sensory neurons within the nociceptive dorsal root ganglia (DRG), stands out as one of the most promising drug targets for pain relief [5]. The property of Nav1.7 channel to amplify small subthreshold stimuli increases the probability that neurons reach their threshold for action potential firing, making it a determinant for pain perception [6]. Notably, loss-of-function mutations in Nav1.7 cause congenital insensitivity to pain, whereas gain-of-function mutations are associated with inherited pain conditions such as primary erythromelalgia and paroxysmal extreme pain disorder [5]. Currently, inhibitors of Nav1.7 have been intensively identified and some were evaluated in clinical trials [7].

Nonselective sodium channel inhibitors, like local anesthetics, class I antiarrhythmic drugs, and antidepressants, have been used clinically for pain relief [8]. Nevertheless, their off-target side effects, including cardiotoxicity, ataxia, confusion, and sedation, limited their therapeutic margin [8]. The selective small molecule inhibitors of Nav1.7 mainly include aryl sulfonamides, aminopyrazines, pyrrolidines, piperidines, indazoles, aminocyclohexanes, tetrahydropyridines, diarylamides and guanidinium derivatives, among which aryl sulfonamides and nitrogen-containing aromatic groups have more potent inhibitory activity [9, 10]. These molecules showed potent analgesic benefits in acute and chronic pain in early trials, however, they yielded disappointing results in clinical trials [9]. Hence, there is an urgent need to develop new structures of Nav1.7 inhibitors.

Natural products have always been a significant source of drug discovery. Naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids (NIQs) are a class of structurally, biosynthetically, and pharmacologically remarkable natural products only derived from two phylogenetically related paleotropical families [11, 12]. Ancistrocladus tectorius, the only native species of the Ancistrocladus genus in China, has been widely used as a traditional folk medicine of the Li nationality for treating malaria, dysentery, and other infectious diseases [13–15]. A variety of pharmaceutical activities, just as antimalarial, antiparasitic, fungicidal, insect larvicidal, molluscicidal, antioxidant, antifeedant, cytotoxic, and anti-HIV activities have been reported for NIQs [11, 16, 17]. However, no Nav channel-related activity has been reported so far.

In a high-throughput screening of natural products in our in-house compound library, we found that NIQs from A. tectorius possessed potent inhibitory activity against Nav1.7 channel. To search for NIQs with Nav1.7 inhibition, a systematical investigation of the twigs of A. tectorius was conducted with the focus on discovering more NIQs and evaluating their inhibitory activity on Nav1.7 channel. Six new and nineteen known NIQs (7–25) were identified from the twigs of A. tectorius. Herein, we reported the isolation and structure elucidation of NIQs from A. tectorius, and the results of their biological assay against Nav 1.7 channel in vitro and in vivo. Among them, compound 2 showed a potent inhibitory effect against Nav1.7 channel and enhanced the channel slow inactivation. Furthermore, compound 2 could inhibit endogenous sodium currents and neuronal excitability in DRG neurons, and dose-dependently relieve the nociceptive behaviors in the formalin-induced mouse inflammatory pain model. In short, NIQs may provide new prototypes for the further development of analgesic drugs by inhibition of Nav1.7 channel.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

All NIQs were isolated from the twigs of A. tectorius with around 95% purity. Optical rotations were measured with a Rudolph Research Analytical Autopol VI automatic polarimeter (Rudolph Research Analytical, Hackettstown, NJ, USA). Analytical High Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) and Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (ESIMS) spectra were performed on a Waters 2695 instrument with a 2998 Photo-Diode Array (PDA) detector coupled with a Waters Acquity Evaporative Light-scattering Detector (ELSD) and a Waters 3100 SQDMS (Single Quadrupole Mass spectrometer) detector using a Waters Sunfire RP C18 column (4.6 mm × 150 mm, 5 μm) with a 1.0 ml/min flow rate (Waters, Milford, MA, USA). 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AVANCE III (Bruker Corporation, Karlsruhe, Germany).

Plasmid and cell culture

The plasmid containing human Nav1.7 cDNA was a gift from Dr. Norbert Klugbauer (Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany) and the vector was pcCNA5-FRT. The plasmids carrying the human Nav1.1 and Nav1.2 cDNA were generously shared by Prof. Hai-bo Yu (Peking Union Medical College, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences, Beijing, China) and subcloned into pcDNA5-FRT-TO vector. The cDNA genes encoding human Nav1.4, Nav1.5, Nav1.6, and Nav1.8 were synthesized by Shanghai Sangon Biotechnology Co., Ltd. and subcloned into pcDNA5-FRT vector. Human Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 were stably expressed in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK293) cells. The cell lines were cultured in high-glucose DMEM (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and screened with 100 µg/ml antibiotic hygromycin B (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. The HEK293 cell lines stably expressing human Nav1.1 and Nav1.2 channels were grown in high-glucose DMEM containing 10% tetracycline-free FBS (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and screened with 50 µg/ml antibiotic hygromycin B. To induce the channel expression, 1 µg/ml doxycycline (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) was added into the medium 24 h prior to the electrophysiology recordings. Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells stably expressing human Nav1.4 and Nav1.6 grew in F-12 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) medium containing 10% FBS. Chinese hamster lung (CHL) cells stably expressing human Nav1.5 channels were grown in high-glucose DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and were selected with 500 μg/ml Geneticin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA). All the cells were cultured at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2. The cells were passaged more than three times and finally plated onto poly-D-lysine-coated (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) glass coverslips 2 h before electrophysiological recordings.

Preparation of dorsal root ganglion neurons

Mouse DRG ganglias were removed aseptically from C57BL/6 mice (4–6 weeks) and incubated with 1 mg/ml collagenase (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and 0.25 mg/ml trypsin solution (Meilunbio, Dalian, China) at 37 °C for 20 min. The digested fragments were subsequently suspended with 50/50 DMEM/F12 (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA, USA) growth medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Then, the ganglia were mechanically dissociated into single cells with fire-polished pipettes and were washed with the growth medium to terminate the digestion. The cells were resuspended with the growth medium and plated onto glass coverslips coated with poly-D-lysine, and cultured for 1 to 2 h in 24-well plate (Shanghai PULLEN Technology Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) in a humidified incubator at 37 °C, 5% CO2, until use. Patch-clamp recordings were conducted in small-diameter (less than 25 µm) DRG neurons.

Whole-cell patch-clamp recordings

The electrophysiological recordings were performed at room temperature using an Axopatch 700B patch-clamp amplifier (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA, USA). Pipettes with access resistance of 2.0–4.0 MΩ were made from borosilicate glass capillaries (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL, USA). For the heterologously expressed Nav channels, the recording intracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 CsF, 10 NaCl, 20 glucose, 10 HEPES and 1.1 EGTA (pH 7.2 adjusted by CsOH); the extracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 3 KCl, 1 MgCl2, 1 CaCl2, 10 HEPES, and 20 glucose (pH 7.4 adjusted by NaOH). To record native sodium currents from DRG neurons, the intracellular solution contained (in mM): 120 CsCl, 10 NaCl, 10 TEA-Cl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 adjusted with CsOH); extracellular solution contained (in mM): 120 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 MgCl2, 20 TEA-Cl, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.4 adjusted by NaOH). For recordings of the action potential firing properties in DRG neurons, the intracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 EGTA, and 10 HEPES (pH 7.2 adjusted by KOH); the extracellular solution contained (in mM): 140 NaCl, 5 KCl, 1 CaCl2, 1.25 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, and 10 glucose (pH 7.4 adjusted by NaOH). All the above reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). During the recordings, the bath solution was continuously perfused using a BPS perfusion system (ALA Scientific Instruments, Westbury, NY, USA). Recordings were acquired 5 min after establishing whole-cell configuration at −80 mV. The sodium currents were sampled at 50 kHz and filtered at 2 kHz. 80% series resistance compensation was applied to minimize voltage errors. P/N subtraction was never utilized throughout the experiments. To evaluate the inhibitory effects of NIQs on Nav1.7 channel, the currents were elicited by a 10 ms test pulse to 0 mV at 0.5 Hz from a holding potential of −40 mV, at which about 95% of Nav1.7 channels would move into the inactivation state. A short 20 ms pulse to –150 mV was applied before the test pulse to relieve channel inactivation during the repetitive stimulation. The activation currents of Nav1.7 were elicited by a range of depolarization pulses (−70 mV to +15 mV) from a holding potential of −120 mV at a stimulus frequency of 0.5 Hz. The steady-state fast inactivation stepped to 0 mV was used to assess the available channels after 500 ms prepulses to varying voltage potentials from a holding potential of −120 mV at a stimulus frequency of 0.5 Hz. The steady-state slow inactivation was measured using a series of 10 s prepulses, ranging from −140 mV to +20 mV in 10 mV increments, followed by a 20 ms step to −120 mV to remove fast inactivation, and a 20 ms test pulse to 0 mV to assess the non-inactivated channels. The native Nav currents in small-diameter DRG neurons were elicited by a range of depolarization pulses (−80 mV to +15 mV) from a holding potential of −100 mV and the stimulus frequency was 0.5 Hz. All experiments were performed at room temperature.

Animals

All animal studies were in accordance with relevant guidelines and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Shanghai Institute of Materia Medica (Shanghai, China). All mice were obtained from the Beijing Vitalriver Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (Beijing, China). Mice were housed and assayed under controlled temperature conditions (22 ± 2 °C) and a 12 h light/dark cycle with free access to food and water. On the day of the experiment, adult male ICR (Institute of Cancer Research) mice (26 ± 2 g) were randomly divided into four groups (n ≥ 8 for each group) and acclimatized to a Plexiglas chamber for at least 30 min before testing. To evaluate the analgesic activity of compound 2 in the formalin test, both compound 2 and formalin solutions were subcutaneously injected into the left hind paw of the mouse in close proximity. Mice received intraplantar injection with 20 µl of vehicle (5% DMSO and 95% Tween 80 (1%)) (Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) or compound 2 (0.1, 1, and 10 mM dissolved in vehicle solution) 30 min prior to formalin (20 μl of 1% formalin, diluted in saline, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) injection while the animal was manually restrained by another experimenter. To ensure stable nociceptive responses from low dosages of formalin and compound 2, the needles of microliter syringes (50 μl, 22s-gauge, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd., Shanghai, China) were separately inserted under the distal basal toris of the mouse second and third toes and advanced about 1 cm proximally under the skin. And then the solutions were carefully delivered and the needles were sustained for 10 s before taking out. Formalin-evoked nociception was assessed by licking time and scoring painful behaviors over the next 60 min and we recalculated licking time and pain score every 5 min. In this study, the pain score represented a weighted sum of pain-related behaviors caused by formalin: 1 = flinching, 2 = shaking, and 3 = licking or biting of the injected paw. Phases were defined as follows: Phase I (0–10 min) and Phase II (10–60 min).

Data and statistical analysis

Patch-clamp data were processed using Clampfit 10.4 (Molecular Device, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) and analyzed with GraphPad Prism 8.0 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Dose-response curves were fitted using the following 3-parameter Hill equation: Y = Bottom + (Top − Bottom)/(), where Top and Bottom respectively represent the channel’s maximum and minimum responses to compounds, X is the value of the logarithm of the concentration, Y is the IDrug/IControl value, and IC50 is the drug concentration producing a half-maximum response. The peak inward currents achieved from activation protocols were converted to conductance values using the equation: G = I/(V–VNa). VNa represents the reversal potential of sodium currents. Activation curves were fitted by the Boltzmann equation: G = Gmin + (Gmax − Gmin)/(1 + exp(V − V1/2/k)), in which Gmax is the maximum conductance, Gmin is the minimum conductance, V is the test potential, V1/2 is the midpoint voltage of kinetics, and k is the slope factor. The maximum current amplitude normalized peak inward currents from steady-state inactivation, fitting with the Boltzmann equation: I = Imin + 1/(1 + exp[Vm − V1/2/k]). In the equation, I is the current amplitude measured during the test depolarization, V1/2 is the midpoint of inaction, and k is the slope factor. Statistical analyses were performed using unpaired two-tailed t-test or one-way ANOVA test, and a P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All results are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Results

Isolation and identification of new NIQs from A. tectorius

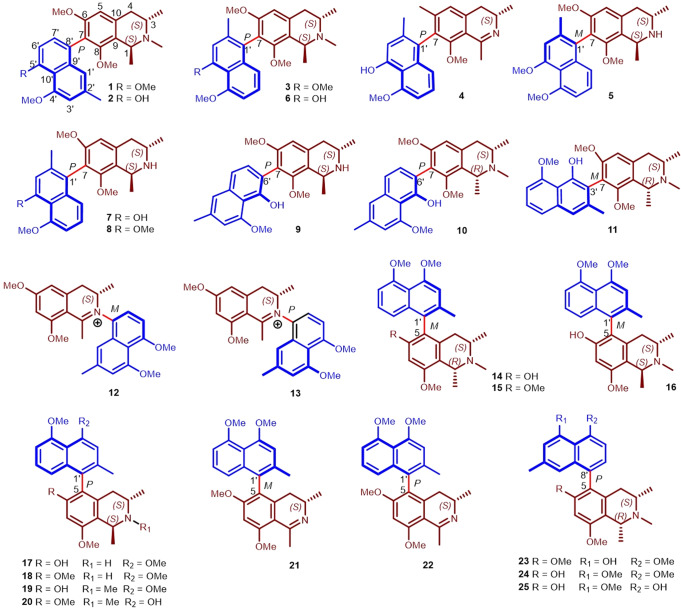

The twigs of A. tectorius were collected from Ganza Ridge, Hainan Province, China. Guided by HPLC-MS, a total of 25 NIQs, six new Ancistrotecines A‒F (1–6) and 19 known compounds (7–25), were isolated from the title plant by various chromatographic separation techniques (silica gel, ODS, Sephadex LH-20, MCI resin, preparative HPLC, etc.). Their stereostructures (Fig. 1), including the linkage modes of the naphthalene group at the isoquinoline core, were revealed by a comprehensive analysis of HRESIMS, 1D, and 2D NMR spectra, as well as ECD spectra and single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis with Cu Kα radiation. The new compounds ancistrotecines A-B (1–2) possessed a 7-8′ linkage, which was found for the second time in the naturally occurring NIQs from A. tectorius. Detailed information about the extraction and isolation procedures and structural elucidation was shown in the Supplementary Information.

Fig. 1. Structures of compounds 1–25 isolated from Ancistrocladus tectorius.

In the structure below, the naphthalene ring is shown in blue, the isoquinoline ring is shown in dark red. The letters R and S indicate the absolute configuration of the chiral carbon. The chiral axis is shown in bright red. The letters P and M represent the absolute configuration of the chiral axis. The number close to the structure is the number of the carbon atom, and the number below the structure is the number of the compounds.

Inhibitory effects of NIQs on Nav1.7 channel

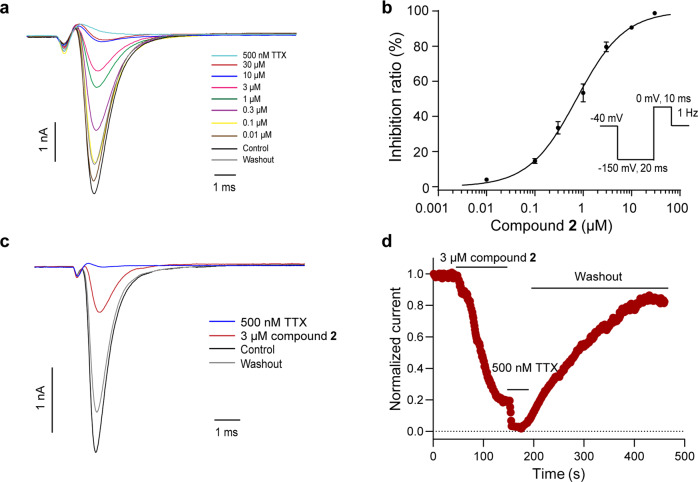

The whole-cell patch-clamp technique was applied to test the effects of compounds 1–25 on Nav1.7 channel, and all isolates with seven linkage types showed inhibitory activity against Nav1.7 channel. Interestingly, NIQs with the naphthalene ring at C-7 position displayed more potent inhibitory activity than those at C-5 position. Meanwhile, compounds 2, 7, 9, and 10 showed more than 80% inhibition on Nav1.7 channel at 10 μM (Table 1). Specifically, the current amplitudes of Nav1.7 channel were reduced by 97.25% ± 0.99% in the presence of 10 μM compound 2 (Fig. 2a, n = 6). The dose-response analysis revealed that the IC50 value of compound 2 on Nav1.7 channel was 0.73 ± 0.03 μM (Fig. 2b, n = 3–4). The time course after the application of 3 μM compound 2 indicated that the steady-state inhibitory effect reached about 90 s after compound treatment, while washout took a longer time, about 300 s (Fig. 2c, d). Notably, the inhibitory activity of 10 μM compound 2 on Nav1.7 channel was stronger than that on other Nav channels, and IDrug/IControl ranked in order of efficacy: hNav1.7 (0.03 ± 0.01) < hNav1.1 (0.10 ± 0.03) < hNav1.4 (0.10 ± 0.02) < hNav1.5 (0.11 ± 0.00) < hNav1.8 (0.15 ± 0.03) < hNav1.2 (0.16 ± 0.03) < hNav1.6 (0.20 ± 0.04) (Fig. 3a, b, n = 3–4). These data showed that compound 2 is a potent inhibitor of Nav1.7 channel among the isolated NIQs.

Table 1.

Effects of 10 μM compounds 1–25 on the peak currents of Nav1.7.

| Linkage type | Compound | Inhibition ratio (%) |

|---|---|---|

| 7-8′ | 1 | 58.08 ± 3.69 |

| 2 | 97.25 ± 0.99 | |

| 7-1′ | 3 | 74.42 ± 2.80 |

| 4 | 75.33 ± 2.42 | |

| 5 | 58.23 ± 5.20 | |

| 6 | 78.86 ± 8.70 | |

| 7 | 81.15 ± 6.24 | |

| 8 | 54.74 ± 0.59 | |

| 9 | 86.39 ± 1.14 | |

| 10 | 85.52 ± 1.85 | |

| 7-3′ | 11 | 76.27 ± 2.18 |

| C-N | 12 | 71.67 ± 3.31 |

| 13 | 48.04 ± 1.04 | |

| 5-1′ | 14 | 33.21 ± 5.10 |

| 15 | 26.14 ± 2.14 | |

| 16 | 22.90 ± 5.51 | |

| 17 | 19.27 ± 7.29 | |

| 18 | 31.97 ± 4.24 | |

| 19 | 37.41 ± 7.92 | |

| 20 | 35.94 ± 5.44 | |

| 21 | 20.57 ± 1.93 | |

| 22 | 19.92 ± 1.45 | |

| 5-8′ | 23 | 65.31 ± 2.77 |

| 24 | 43.88 ± 2.30 | |

| 25 | 31.63 ± 5.77 |

The values of the inhibition ratios are presented as mean ± SEM (n ≥ 3).

Fig. 2. Effects of compound 2 on heterologously expressed Nav1.7 channel.

a Representative Nav1.7 current traces of increasing concentrations of compound 2. b Dose-response curve of compound 2 on Nav1.7 channel. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–4). c Representative Nav1.7 current traces of 3 μM compound 2. d Time course of the effect of 3 μM compound 2 on Nav1.7 channel.

Fig. 3. The subtype selectivity of compound 2 on Nav channels.

a Representative current traces of 10 μM compound 2 on Nav isoforms. b Bar graph showing the inhibitory efficacy of 10 μM compound 2 on Nav channels. The order of their effectiveness according to the values of IDrug/IControl is as follows: hNav1.7 (0.03 ± 0.01) < hNav1.1 (0.10 ± 0.03) < hNav1.4 (0.10 ± 0.02) < hNav1.5 (0.11 ± 0.00) < hNav1.8 (0.15 ± 0.03) < hNav1.2 (0.16 ± 0.03) < hNav1.6 (0.20 ± 0.04). Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 3–4). **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, one-way ANOVA test.

Modulation of compound 2 on Nav1.7 channel kinetics

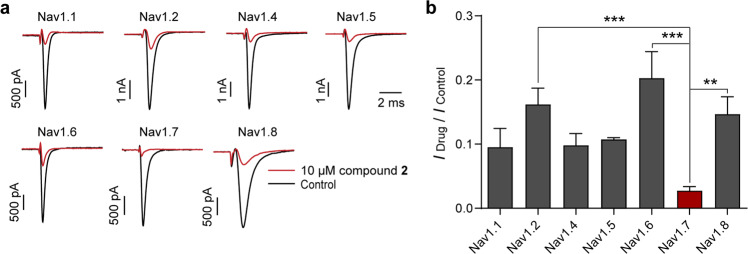

To reveal how compound 2 inhibited Nav1.7 channel activity, the effects of 3 μM (around IC80) compound 2 on channel steady-state activation and steady-state inactivation were investigated. Activation curves were fitted with the Boltzmann equation and showed that the half-activation voltages of Nav1.7 before and after treatment with 3 μM compound 2 were −25.05 ± 0.94 mV and −31.59 ± 1.60 mV, respectively (Fig. 4a, b and Table 2). The hyperpolarizing shift of the steady-state activation could be partially reversed after compound 2 was washed out (Fig. 4b). Furthermore, the steady-state fast inactivation was slightly affected and no significant difference was observed before and after the application of compound 2 (Fig. 4c, d and Table 2). Notably, the steady-state slow inactivation was dramatically shifted toward the hyperpolarizing direction (Fig. 4e). The V1/2 values of slow inactivation were changed to −65.53 ± 4.39 mV from −39.54 ± 2.77 mV (Fig. 4f and Table 2). As hyperpolarizing channel activation commonly benefits channel opening, our data suggested that compound 2 could significantly enhance slow inactivation, which may contribute to the inhibition of Nav1.7 channel.

Fig. 4. Effects of compound 2 on the steady-state activation and inactivation of Nav1.7 channel.

a Representative activation current traces of Nav1.7 channel before and after perfusion of 3 μM compound 2. b The activation curves of Nav1.7 currents with (red) or without (black) 3 μM compound 2 (n = 5). c Representative steady-state fast inactivation current traces of Nav1.7 before and after application of 3 μM compound 2. d The steady-state fast inactivation curves of Nav1.7 channel with or without 3 μM compound 2 (n = 5). e Representative steady-state slow inactivation current traces of Nav1.7 before and after application of 3 μM compound 2. f The steady-state slow inactivation curves of Nav1.7 channel with or without 3 μM compound 2 (n = 5).

Table 2.

Effects of 3 μM Compound 2 on Nav1.7 channel kinetics.

| Group | Nav1.7 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Compound 2 (3 μM) | ||

| Activation | V1/2 (mV) | −25.05 ± 0.94 | −31.59 ± 1.60** |

| k | 4.12 ± 0.59 | 3.34 ± 0.31 | |

| Fast inactivation | V1/2 (mV) | −73.97 ± 1.81 | −78.87 ± 1.90 |

| k | −5.40 ± 0.24 | −5.58 ± 0.12 | |

| Slow inactivation | V1/2 (mV) | −39.54 ± 2.77 | −65.53 ± 4.39*** |

| k | −13.70 ± 0.96 | −12.27 ± 0.67 | |

The values are presented as mean ± SEM.

**P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

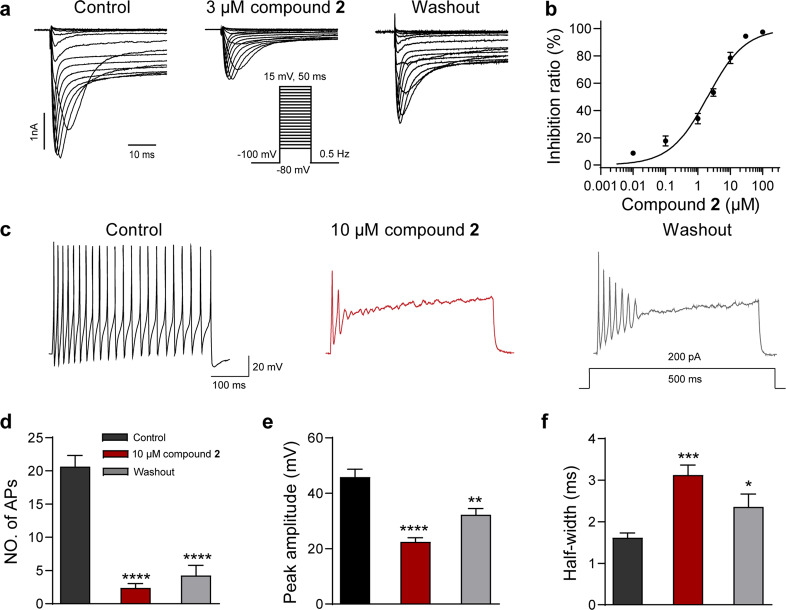

Suppression activity of compound 2 in nociceptive DRG neurons

The inhibition of compound 2 on heterologously expressed Nav1.7 channel suggested that it may also reduce native sodium currents in nociceptive neurons. As shown in Fig. 5a, the native sodium currents were powerfully suppressed, and the current amplitudes were reduced by 70% approximately after the perfusion of 3 µM compound 2. Notably, the IC50 value of compound 2 on the native Nav currents was 1.99 ± 0.31 µM, which was similar to that on Nav1.7 channel expressed in heterologous cells (Fig. 5b). As Nav currents play a pivotal role in the generation and propagation of action potential firing, we furtherly assessed the suppression of compound 2 on the excitability of the nociceptive small-diameter DRG neurons. In conformity with its inhibition of native sodium currents, the amplitude and firing frequency of action potentials were significantly reduced after the application of 10 µM compound 2 (Fig. 5c, d, n = 6). The peak amplitudes were reduced from 45.81 ± 2.84 mV to 22.46 ± 1.47 mV by 10 µM compound 2 (Fig. 5e, n = 6). In addition, the half-width of action potentials was significantly prolonged by compound 2, and the values were changed from 1.62 ± 0.11 ms to 3.13 ± 0.24 ms (Fig. 5f, n = 6). These data showed that compound 2 can potently inhibit native sodium currents and thereby suppressing action potential firing in pain-sensing DRG neurons.

Fig. 5. Compound 2 suppressed Nav currents and the action potential firing in DRG neurons.

a Representative current traces of native Nav currents inhibited by compound 2 at 3 µM (n = 5). b Dose-response curve of compound 2 at DRG neurons. Data are represented as mean ± SEM (n = 5). c Representative traces of action potential (AP) firing recorded from a DRG neuron before (left) and after (middle) application of 10 µM compound 2. d Bar graph showing the effects of 10 µM compound 2 on the firing frequency, peak amplitude (e), half-width (f) of AP (n = 6). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. Control, unpaired two-tailed t-test.

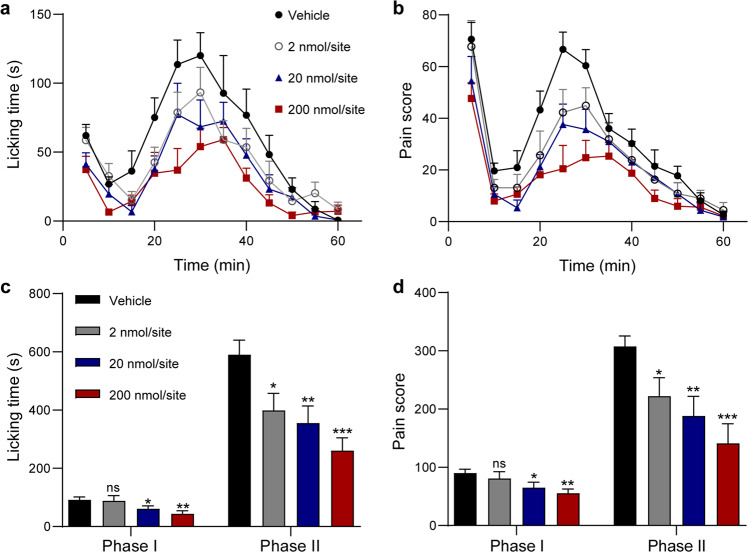

Analgesic effects of compound 2 in the formalin test in mouse

The potent suppression of the small-diameter DRG neurons prompted us to validate its analgesic activity in vivo. The formalin test is a classical inflammatory pain model and has been widely used to evaluate the analgesic activity of compounds in laboratory animals [18]. In this test, intraplantar injection of formalin elicits a biphasic pain response, including behaviors such as paw lifting and licking [19, 20]. Phase I (0–10 min) reflects primarily nociceptive pain, whereas Phase II (11–60 min) represents inflammatory pain [21]. To investigate the analgesic effects of compound 2 on formalin-induced pain behaviors in mice, the compound was locally injected into the ipsilateral plantar with 1% formalin. As shown in Fig. 6, 0.1 mM (2 nmol/site) compound 2 had no significant effect on Phase I but significantly decreased licking time and pain score in Phase II (Fig. 6c, d). At the high concentration of 1 mM (20 nmol/site) and 10 mM (200 nmol/site), compound 2 significantly decreased both licking time and pain score in Phase I and Phase II (Fig. 6c, d). Taken together, these data indicated that compound 2 can dose-dependently relieve inflammatory pain in vivo.

Fig. 6. Analgesic effects of local injection of compound 2 in formalin-induced mouse inflammatory pain model.

Time course of licking time (a) and pain score (b) of mice after a single intrapantar injection of compound 2 at indicated dose (n = 9 for each group). Bar graph showing the quantifications of the licking time (c) and pain score (d) summarized from a and b (n = 9 for each group). ns no significance, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Control, one-way ANOVA test.

Discussion

Pain has become one of the most serious social problems by greatly reducing the quality of life of patients and causing a serious socioeconomic burden [22, 23]. In the body, the feeling of pain is divided into two parts: first, nociceptors, a kind of specialized peripheral neurons, detect noxious stimuli and transmit information to the spinal cord; then, nociceptive signals are transmitted to the brain for integration and processing [24]. In order to avoid the common central side effects similar to opioid analgesics, efforts have been made to develop analgesic drugs targeting peripheral nociceptors. Nav1.7, which is widespread in sensory neurons, is considered to be one of the most potential peripheral analgesic targets because of its vital role in AP generation and multiple genetically-related evidences suggest that it is strongly associated with pain-sensing [25–27]. Over the past decade, dozens of potent Nav1.7 inhibitors have emerged, but their in vivo analgesic effects are very limited. Here, we reported a series of NIQs with novel structural backbones from A. tectorius (Fig. 1 and Table 1), and compound 2 possessed the strongest inhibitory effect on Nav1.7 channel with an IC50 value of 0.73 ± 0.03 µM (Fig. 2). In addition, compound 2 showed the strongest inhibitory activity on Nav1.7 channel compared to other Nav channel subtypes (Fig. 3). By comparing NIQs with other reported Nav1.7 inhibitors, we found that NIQs have a different structure and do not share pharmacophore features with these inhibitors [9, 10]. A further comparison revealed that NIQs, which consist of only a naphthalene ring and isoquinoline ring, are more rigid structurally than aryl sulfonamides or other nitrogenous aryl derivatives with longer chain structures. To our knowledge, it is the first time to uncover that NIQs are new Nav1.7 channel inhibitors and the linkage type may affect the bioactivity.

Modulation on the channel kinetics has been reported to be responsible for the inhibitory activity of multiple Nav1.7 channel antagonists. The classical local anesthetic lidocaine reduced the transition of Nav1.7 channel to a slow inactivated state, and meanwhile, dramatically shifted both the fast and slow inactivation toward the hyperpolarized direction [28]. In addition, lidocaine did not affect the voltage-dependent activation of Nav1.7 but could shift the steady-state activation curve of Nav1.8 toward a more hyperpolarizing potential [29]. In our study, 3 μM compound 2 shifted the half-activation voltages of Nav1.7 from −25.05 ± 0.94 mV to −31.59 ± 1.60 mV (Fig. 4a, b and Table 2). This may suggest in part that compound 2 has a strong affinity for Nav1.7, just like lidocaine for Nav1.8 channel [29]. On the other hand, compound 2 shifted both the channel activation and slow inactivation toward the hyperpolarized direction, especially the steady-state slow inactivation (Fig. 4c–f and Table 2). This may be more beneficial in relieving pain because sodium channels are mostly undergoing inactivated state during long-lasting pain attacks [30]. Overall, our findings would increase the mechanistic diversity of the Nav1.7 channel antagonists besides the new scaffolds.

Nav1.7 channel plays a prominent role in nociceptor excitability and pain sensing. We found that compound 2 decreased the native sodium currents in a dose-dependent manner with an IC50 value similar to that obtained from the Nav1.7 cell line (Fig. 5a, b). Previous studies revealed that Nav1.7 channel inhibitors can suppress the firing frequency, reduce the peak amplitude and prolong the half-width of the action potential, such as selective Nav1.7 inhibitor PF-05198007 [31–35]. Consistently, compound 2 decreased the peak amplitude and prolonged the half-width of action potential firing in DRG neurons (Fig. 5c–f). Notably, local administration of compound 2 significantly reduced both licking time and pain score in the formalin test (Fig. 6). The dose-dependent relief of compound 2 in vivo suggested that it might act as a prototype for the analgesic drug development targeting Nav1.7 channel. Besides the inhibition of native sodium currents, we found that compound 2 could also dose-dependently inhibit endogenous potassium currents and selectively inhibited IK, which modulates neuronal excitability and thereby being involved in pain-sensing [36, 37] (Supplementary Fig. S53). It is worth noting that the inhibitory efficacy of 10 μM compound 2 was around 50%, which is much lower than that on native sodium currents (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. S53). Nevertheless, more studies are needed to fully reveal the analgesic mechanism of compound 2 in the future.

In short, our findings provided NIQs as a new structural scaffold associated with potent inhibitory activity on the Nav1.7 channel and have a significant analgesic effect in vivo. The preliminary structure-activity relationship showed that the naphthalene ring at the C-7 position exhibited more potent inhibition activity than at the C-5 site. Nevertheless, more NIQ analogs are needed to adequately figure out the relationship between the NIQs structures and their inhibitory potency. More studies are also required to investigate the inhibitory effect on other pain-related ion channels and the molecular determinants responsible for its inhibition. In a word, NIQs from A. tectorius represent novel scaffolds that are distinct from known anti-analgesic approved drugs and clinical candidates and provide promising starting points for further development of analgesic drugs by inhibition of Nav 1.7 channel.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Science Fund for Distinguished Young Scholars (grant No. 81825021), the Youth Innovation Promotion Association of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (grant No. 2020284), the Fund of Science and Technology Commission of Shanghai Municipality (grant No. 19431906000), the Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (grant No. 2020B0303070002), High-level New R&D Institute (grant No. 2019B090904008) and High-level Innovative Research Institute (grant No. 2021B0909050003) from Department of Science and Technology of Guangdong Province, Zhongshan Municipal Bureau of Science and Technology, the Lingang Laboratory (LG202103-01-06, LG202103-01-05), and the National Science and Technology Innovation 2030 Major Program (grant No. 2021ZD0200900).

Author contributions

SY, YMZ, ZBG and YY conceived and designed the research; QQW, LW and WBZ performed experiments; QQW and LW analyzed the data; CPT and XQC were in charge of resources and softwares; QQW, LW, YMZ, SY, ZBG and YY wrote and reviewed the manuscript. All authors discussed the study.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

These authors contributed equally: Qiao-qiao Wang, Long Wang

Contributor Information

Yue-ming Zheng, Email: zhengyueming@simm.ac.cn.

Sheng Yao, Email: yaosheng@simm.ac.cn.

Zhao-bing Gao, Email: zbgao@simm.ac.cn.

Yang Ye, Email: yye@simm.ac.cn.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-023-01084-9.

References

- 1.Catterall WA. From ionic currents to molecular mechanisms: the structure and function of voltage-gated sodium channels. Neuron. 2000;26:13–25. doi: 10.1016/S0896-6273(00)81133-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Melnikova DI, Khotimchenko YS, Magarlamov TY. Addressing the issue of tetrodotoxin targeting. Mar Drugs. 2018;16:1053–61. doi: 10.3390/md16100352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Djouhri L, Newton R, Levinson SR, Berry CM, Carruthers B, Lawson SN. Sensory and electrophysiological properties of guinea-pig sensory neurones expressing Nav1.7 (PN1) Na+ channel alpha subunit protein. J Physiol. 2003;546:565–76. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.026559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bosmans F, Swartz KJ. Targeting voltage sensors in sodium channels with spider toxins. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31:175–82. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2009.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vetter I, Deuis JR, Mueller A, Israel MR, Starobova H, Zhang A, et al. NaV1.7 as a pain target—from gene to pharmacology. Pharmacol Ther. 2017;172:73–100. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2016.11.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goodwin G, McMahon SB. The physiological function of different voltage-gated sodium channels in pain. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2021;22:263–74. doi: 10.1038/s41583-021-00444-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alsaloum M, Higerd GP, Effraim PR, Waxman SG. Status of peripheral sodium channel blockers for non-addictive pain treatment. Nat Rev Neurol. 2020;16:689–705. doi: 10.1038/s41582-020-00415-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li ZM, Chen LX, Li H. Voltage-gated sodium channels and blockers: an overview and where will they go? Curr Med Sci. 2019;39:863–73. doi: 10.1007/s11596-019-2117-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulcahy JV, Pajouhesh H, Beckley JT, Delwig A, Du Bois J, Hunter JC. Challenges and opportunities for therapeutics targeting the voltage-gated sodium channel isoform Nav1.7. J Med Chem. 2019;62:8695–710. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.8b01906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kingwell K. Nav1.7 withholds its pain potential. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2019;18:321–3. doi: 10.1038/d41573-019-00065-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bringmann G, Zhang G, Olschlager T, Stich A, Wu J, Chatterjee M, et al. Highly selective antiplasmodial naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from Ancistrocladus tectorius. Phytochemistry. 2013;91:220–8. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2012.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tshitenge DT, Feineis D, Mudogo V, Kaiser M, Brun R, Bringmann G. Antiplasmodial ealapasamines A-C, 'mixed' naphthylisoquinoline dimers from the central african liana Ancistrocladus ealaensis. Sci Rep. 2017;7:5767. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05719-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bringmann G, Seupel R, Feineis D, Xu M, Zhang G, Kaiser M, et al. Antileukemic ancistrobenomine B and related 5,1'-coupled naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from the Chinese liana Ancistrocladus tectorius. Fitoterapia. 2017;121:76–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fitote.2017.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seupel R, Hemberger Y, Feineis D, Xu M, Seo EJ, Efferth T, et al. Ancistrocyclinones A and B, unprecedented pentacyclic N,C-coupled naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids, from the Chinese liana Ancistrocladus tectorius. Org Biomol Chem. 2018;16:1581–90. doi: 10.1039/C7OB03092D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tang CP, Yang YP, Zhong Y, Zhong QX, Wu HM, Ye Y. Four new naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from Ancistrocladus tectorius. J Nat Prod. 2000;63:1384–7. doi: 10.1021/np000091d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li J, Seupel R, Feineis D, Mudogo V, Kaiser M, Brun R, et al. Dioncophyllines C2, D2, and F and related naphthylisoquinoline alkaloids from the Congolese liana Ancistrocladus ileboensis with potent activities against plasmodium falciparum and against multiple myeloma and leukemia cell lines. J Nat Prod. 2017;80:443–58. doi: 10.1021/acs.jnatprod.6b00967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aswathanarayan JB, Vittal RR. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Rotula aquatica and Ancistrocladus heyneanus. J Pharm Res. 2013;6:313–7. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dubuisson D, Dennis SG. The formalin test: a quantitative study of the analgesic effects of morphine, meperidine, and brain stem stimulation in rats and cats. Pain. 1977;4:161–74. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(77)90130-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tjolsen A, Berge OG, Hunskaar S, Rosland JH, Hole K. The formalin test: an evaluation of the method. Pain. 1992;51:5–17. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(92)90003-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abbott FV, Franklin KBJ, Westbrook FR. The formalin test: scoring properties of the first and second phases of the pain response in rats. Pain. 1995;60:91–102. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(94)00095-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McNamara CR, Mandel BJ, Bautista DM, Siemens J, Deranian KL, Zhao M, et al. TRPA1 mediates formalin-induced pain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13525–30. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0705924104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.GBD 2017 DALYs and HALE Collaborator. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1260–344. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32130-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gaskin DJ, Richard P. The economic costs of pain in the United States. J Pain. 2012;13:715–24. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, Khadijah Adam S, Abdul Manan N, Basir R. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19:2164–87. doi: 10.3390/ijms19082164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang Y, Wang Y, Li S, Xu Z, Li H, Ma L, et al. Mutations in SCN9A, encoding a sodium channel alpha subunit, in patients with primary erythermalgia. J Med Genet. 2004;41:171–4. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2003.012153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fertleman CR, Baker MD, Parker KA, Moffatt S, Elmslie FV, Abrahamsen B, et al. SCN9A mutations in paroxysmal extreme pain disorder: allelic variants underlie distinct channel defects and phenotypes. Neuron. 2006;52:767–74. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2006.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ma RSY, Kayani K, Whyte-Oshodi D, Whyte-Oshodi A, Nachiappan N, Gnanarajah S, et al. Voltage gated sodium channels as therapeutic targets for chronic pain. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2709–22. doi: 10.2147/JPR.S207610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sheets PL, Jarecki BW, Cummins TR. Lidocaine reduces the transition to slow inactivation in Nav1.7 voltage-gated sodium channels. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:719–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01209.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chevrier P, Vijayaragavan K, Chahine M. Differential modulation of Nav1.7 and Nav1.8 peripheral nerve sodium channels by the local anesthetic lidocaine. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142:576–84. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zheng YM, Wang WF, Li YF, Yu Y, Gao ZB. Enhancing inactivation rather than reducing activation of Nav1.7 channels by a clinically effective analgesic CNV1014802. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2018;39:587–96. doi: 10.1038/aps.2017.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xing JL, Hu SJ, Xu H, Han S, Wan YH. Subthreshold membrane oscillations underlying integer multiples firing from injured sensory neurons. NeuroReport. 2001;12:1311–3. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105080-00051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu Q, Henry JL. Delayed onset of changes in soma action potential genesis in nociceptive A-beta DRG neurons in vivo in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Mol Pain. 2009;5:57. doi: 10.1186/1744-8069-5-57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Niu HL, Liu YN, Xue DQ, Dong LY, Liu HJ, Wang J, et al. Inhibition of Nav1.7 channel by a novel blocker QLS-81 for alleviation of neuropathic pain. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2021;42:1235–47. doi: 10.1038/s41401-021-00682-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang J, Mis MA, Tanaka B, Adi T, Estacion M, Liu S, et al. A typical changes in DRG neuron excitability and complex pain phenotype associated with a Nav1.7 mutation that massively hyperpolarizes activation. Sci Rep. 2018;8:1811. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-20221-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexandrou AJ, Brown AR, Chapman ML, Estacion M, Turner J, Mis MA, et al. Subtype-selective small molecule inhibitors reveal a fundamental role for Nav1.7 in nociceptor electrogenesis, axonal conduction and presynaptic release. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0152405. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0152405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim DM, Nimigean CM. Voltage-gated potassium channels: a structural examination of selectivity and gating. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2016;8:a029231. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a029231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cao XH, Byun HS, Chen SR, Cai YQ, Pan HL. Reduction in voltage-gated K+ channel activity in primary sensory neurons in painful diabetic neuropathy: role of brain-derived neurotrophic factor. J Neurochem. 2010;114:1460–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06863.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.