Abstract

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors show promising effects in the treatment of multiple tumor types. Biomarkers are biological indicators used to select patients for a systemic anticancer treatment, but there are only a few clinically useful biomarkers such as PD-L1 expression and tumor mutational burden, which can be used to predict immunotherapy response. In this study, we established a database consisting of both gene expression and clinical data to identify biomarkers of response to anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4 immunotherapies. A GEO screening was executed to identify datasets with simultaneously available clinical response and transcriptomic data regardless of cancer type. The screening was restricted to the studies involving administration of anti-PD-1 (nivolumab, pembrolizumab), anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab, durvalumab) or anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) agents. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis and Mann-Whitney test were executed across all genes to identify features related to therapy response. The database consisted of 1434 tumor tissue samples from 19 datasets with esophageal, gastric, head and neck, lung, and urothelial cancers, plus melanoma. The strongest druggable gene candidates linked to anti-PD-1 resistance were SPIN1 (AUC = 0.682, P = 9.1E-12), SRC (AUC = 0.667, P = 5.9E-10), SETD7 (AUC = 0.663, P = 1.0E-09), FGFR3 (AUC = 0.657, P = 3.7E-09), YAP1 (AUC = 0.655, P = 6.0E-09), TEAD3 (AUC = 0.649, P = 4.1E-08) and BCL2 (AUC = 0.634, P = 9.7E-08). In the anti-CTLA-4 treatment cohort, BLCAP (AUC = 0.735, P = 2.1E-06) was the most promising gene candidate. No therapeutically relevant target was found to be predictive in the anti-PD-L1 cohort. In the anti-PD-1 group, we were able to confirm the significant correlation with survival for the mismatch-repair genes MLH1 and MSH6. A web platform for further analysis and validation of new biomarker candidates was set up and available at https://www.rocplot.com/immune. In summary, a database and a web platform were established to investigate biomarkers of immunotherapy response in a large cohort of solid tumor samples. Our results could help to identify new patient cohorts eligible for immunotherapy.

Keywords: immunotherapy, immune checkpoint inhibitors, gene expression, ROC curve, druggable genes, drug resistance

Introduction

Immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) were introduced for the treatment of solid and hematological malignancies with outstanding results in the last decade [1]. There are three groups of ICIs. The first group consists of ICIs inhibiting cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) on T cells [2, 3], the second one is related to programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) receptor on lymphocytes [4], and the third group is linked to programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-L1) on tumor cells. Physiologically, PD-1 is expressed on several immune cells (e.g., lymphocytes, natural killer cells), and PD-L1 is present on almost all somatic cells (e.g., hematopoietic cells or tumor cells). In tumors, blockade of the PD-1/PD-L1 axis results in the survival of the malignant cells [5].

The first ICI approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating metastatic melanoma was ipilimumab, a fully human monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4 [6]. Ipilimumab was shown to be effective in an extremely wide range of advanced cancers including melanoma [7, 8], renal cell carcinoma (RCC) [9, 10], mismatch repair deficient (dMMR) or microsatellite instability-high (MSI-H) colorectal carcinoma [11], hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [12], pleural mesothelioma [13], and non-small-cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [14]. Tremelimumab, another fully human monoclonal antibody against CTLA-4, has been investigated in multiple solid tumors with mixed results [15]. Tremelimumab has not yet received an FDA-approval so far.

Nivolumab was the first approved monoclonal antibody targeting PD-1 and can be administered in advanced melanoma, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, HCC, NSCLC and SCLC, RCC, head and neck cancer, urothelial carcinoma, CRC [5], gastric, or esophageal adenocarcinoma [16], and malignant pleural mesothelioma [13]. Pembrolizumab, a humanized monoclonal antibody against PD-1 has been approved either as a monotherapy or as a combination therapy for the treatment of recurrent or metastatic melanoma [17], NSCLC, head and neck squamous cell cancer (HNSCC), gastric/gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma, lymphoma, urothelial cancer, cervical cancer, Merkel cell carcinoma, RCC [5], triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) [18], cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma [19, 20], endometrial cancer [21], and HCC [22]. Pembrolizumab can be administered to patients regardless of their age and tumor type in case their tumor is MSI-H or dMMR [23]. Recently, dostarlimab, a humanized anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibody, has also received an FDA-approval for recurrent or advanced MSI-H/dMMR endometrial cancer and other solid tumors [24, 25].

PD-L1-blocking antibodies started with avelumab in 2015 for metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma, and then it continued with locally advanced or metastatic urothelial carcinoma (mUC), and advanced RCC. Durvalumab, another human monoclonal antibody was accepted for metastatic urothelial bladder cancer, urothelial carcinoma, NSCLC, and SCLC [5, 26]. Atezolizumab, a third PD-L1 monoclonal antibody, is also accepted for locally advanced or mUC, metastatic NSCLC, SCLC, TNBC, HCC, and melanoma [5, 27, 28].

Biomarkers are biological indicators that can be used to select patients for a systemic anticancer treatment like immunotherapy. A major limitation of the widespread use of immunotherapies is the fact that there are only a few clinically useful biomarkers capable to predict therapy response. A study [29] found that tumor mutational burden (TMB), and PD-L1 expression can predict response to pembrolizumab in a huge variety of cancers (melanoma, bladder cancer, breast cancer, CRC, HNSCC, and SCLC). The correlation between PD-L1 expression and MSI and response to pembrolizumab was also investigated in gastric cancer [30]. Cluster of Differentiation 8 positive (CD8+) T cell phenotype and TMB were associated with enhanced response to atezolizumab in mUC [31]. Findings from other studies highlighted the central role of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in nivolumab [32], pembrolizumab [33], and anti-CTLA-4 response [34]. The importance of both innate, and adaptive immune systems was emphasized in connection with anti-PD-1 response in NSCLC [35, 36], melanoma [36, 37], and HNSCC [36]. Meanwhile, in recent years, the tumors of several ICI-treated patient cohorts were investigated with transcriptomic technologies. The simultaneous analysis of the entire transcriptome makes it possible to identify new genes capable to serve as biomarkers of response and to validate previously suggested biomarker candidates.

Here, our goal was to expose and integrate available transcriptomic datasets of ICI-treated tumors to establish a framework enabling an integrated analysis of genes related to treatment sensitivity or resistance. Uncovering robust genes with increased expression in treatment-resistant tumors could offer the opportunity to develop a targeted therapy to augment the effects of immune-checkpoint inhibitors.

Materials and methods

ICI dataset screening

We screened the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) repository using the keywords “human [organism] AND (anti-PD-1 OR anti-PD-1 OR anti-PD-L1 OR anti-PD-L1 OR anti-CTLA-4 OR anti-CTLA-4)”, and “human [organism] AND (pembrolizumab OR nivolumab OR atezolizumab OR durvalumab OR avelumab OR cemiplimab OR ipilimumab OR camrelizumab OR cintilimab OR tislelizumab OR toripalimab)” on 10th Jan 2022. We omitted datasets with no available gene expression or clinical data, or with single-cell RNA-sequencing (scRNA-Seq), T or B cell receptor sequencing (TCR/BCR-Seq), non-mRNA-sequencing (e.g., whole-exome sequencing, non-coding RNA profiling, methylation profiling, protein array), studies of cell lines, stem cells, sorted peripheral blood mononuclear cells, studies in mice, studies without cancer, and GEO SuperSeries files. We also conducted a literature research to find additional studies. Our scope of investigation only included studies with simultaneously available clinical (response) and bulk-tissue gene expression data.

Database setup

Gene expression data from all eligible datasets were combined into a single table, quantile normalized and scaled to 1000. For the clinical annotation, we categorized patients as responders or non-responders based on reported pathological response or survival time. Those patients were selected as responders who experienced progression-free survival (PFS) longer than 12 months or had a partial response (PR) or complete response (CR). Those who experienced less than 12 months of PFS or had progressive disease (PD) or stable disease (SD) were categorized as non-responders. Survival time was not used if the patient had no event and the follow-up time was censored before 12 months. Tumor samples obtained before induction of the therapy were termed “pre-treatment” samples, and tumors collected during or after the therapy were termed “on-treatment” samples.

Linking gene expression and therapy response

Three separate analyses were performed across all genes to identify pre-treatment gene expression changes related to response against anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4 treatment. On-treatment samples were left out of the analysis because of low sample sizes.

We used Gene Ontology (GO) Enrichment analysis [38] to uncover biological processes connected to the gene lists related to response against anti-PD-1, anti-PD-L1, and anti-CTLA-4 treatment.

Druggability of candidate genes was determined by a literature search in PubMed and GeneCards (https://www.genecards.org/) to include those where (1) in silico prediction, (2) in vitro assay, (3) clinical study or (4) FDA-approval of the given drug were available.

Validation of the results

We extended our previously established ROC plotter platform to enable the investigation of new biomarkers and the validation of current results in all patients treated with immunotherapy. The platform is running on Ubuntu 20.04.4 LTS server driven by Apache 2.4.41. The front-end site was developed in PHP using the YII2 framework. The application data are stored in the PostgreSQL database and the computations are performed via an R script. The portal can be reached at https://www.rocplot.com/immune.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted in the R environment (https://www.r-project.org/) using Bioconductor libraries (https://www.bioconductor.org/). To find differentially expressed genes associated with improved or worse outcomes, Mann-Whitney unpaired U-test and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis were used. To avoid false discovery due to multiple testing, Bonferroni-adjustment (P = 0.05) was applied with the service https://www.multipletesting.com/ [39].

Results

Screening results

We have identified 225 series files in NCBI GEO fulfilling the initial search criteria. Through literature research, we also found the Cancer Research Institute iAtlas (CRI iAtlas) (https://www.cri-iatlas.org/), another portal with ICI-treated samples [40], in which another six datasets were found. Finally, five additional cohorts were found by looking up the referenced literature [30, 37, 41–43].

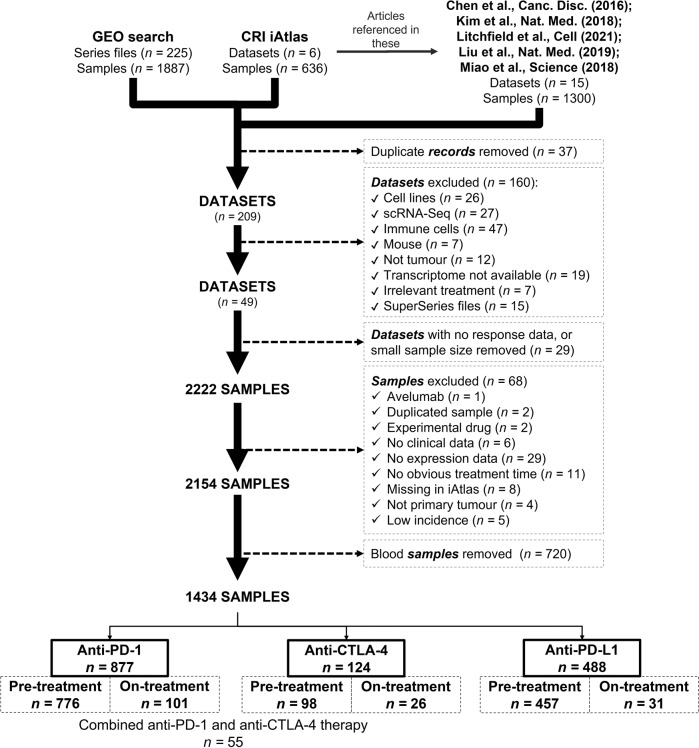

In summary, from NCBI GEO [44, 45], CRI iAtlas, Chen et al. [43], Litchfield et al. [41], Liu et al. [37], Kim et al. [30], and Miao et al. [42], altogether 246 datasets with 3823 samples were found. Then, we removed duplicate records. For example, Litchfield et al. described eleven studies out of which four were also included in CRI iAtlas, and two in GEO (GSE78220, GSE91061). A detailed description of the complete screening process is provided in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Screening datasets.

Setup of the integrated database

Database assembly

Datasets were individually investigated to include only those in which at least one of the following clinical variables was reported: progression-free survival or interval (PFS/PFI), relapse-free survival (RFS), overall survival (OS), recurrence, and response determined by the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) (including complete response (CR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD)).

Twenty datasets with 2222 samples met these eligibility criteria and were selected for further analysis (Fig. 1). Sixty-eight samples were excluded due to different restrictions, such as (1) a very low number of samples treated with a specific agent (e.g., avelumab or experimental drugs), (2) duplicated samples, (3) missing clinical variable (e.g., event for survival), (4) no expression data, (5) ambiguous treatment time, (6) samples taken from metastatic sites or (7) low incidence of the given tumor type. By using these filtering criteria, the cohort was reduced to 2,154 samples out of which 720 samples were blood samples – these were removed from further analysis.

Finally, 1434 samples from 19 datasets were investigated manually. Different tumor types were integrated into the database, including (a) melanoma (n = 570), (b) esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (n = 103), (c) gastric cancer (n = 45), (d) urothelial cancer (bladder/ureter/pelvis cancer) (n = 449), (e) head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (n = 110), (f) hepatocellular carcinoma (n = 22), g) lung cancer (small cell and non-small-cell lung cancer, or squamous and non-squamous non-small cell lung cancer) (n = 60), (h) breast cancer (triple-negative (n = 12), and ER + HER2- breast cancer (n = 2)), (i) renal cell carcinoma (n = 33), and (j) glioblastoma (n = 28). Patients either received anti-PD-1 (nivolumab, or pembrolizumab) (all n = 877; pre-treatment n = 776; on-treatment n = 101), anti-PD-L1 (atezolizumab, or durvalumab) (all n = 488; pre-treatment n = 457; on-treatment n = 31), or anti-CTLA-4 (ipilimumab) (all n = 124; pre-treatment n = 98; on-treatment n = 26) treatments, out of which 55 patients received combination therapy with anti-PD-1 (Fig. 1).

Eventually, datasets were stratified into six groups: (1) pre-treatment anti-PD-1 (GSE78220, GSE91061, GSE93157, GSE115821, GSE121810, GSE136961, GSE140901, GSE165745, GSE176307, Cristescu2018, Gide2019, Kim2018, Miao2018, and Liu2019), (2) on-treatment anti-PD-1 (GSE78220, GSE91061, GSE115821, GSE121810, Gide2019, and Liu2019), (3) pre-treatment anti-PD-L1 (GSE165252, GSE176307, GSE183924, Mariathasan2018, and Miao2018), (4) on-treatment anti-PD-L1 (GSE165252), (5) pre-treatment anti-CTLA-4 (GSE115821, GSE140901, GSE165278, Gide2019, Miao2018, and VanAllen2015), and (6) on-treatment anti-CTLA-4 (GSE115821, GSE165278, and Gide2019) cohort. Due to the relatively small sample sizes, on-treatment datasets were excluded and three separate analyses were performed using the pre-treatment samples only. A summary of each dataset is listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of cancer datasets with immune-checkpoint inhibitor therapy included in the study

| Dataset ID | Reference | Sample n | Patient n | Tumor type | Drug | Sample acquisition | Outcome | Method for measuring gene expression |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSE78220 | NCBI GEO and CRI iAtlas | 28 | 27 | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | OS and response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2000) |

| GSE91061 | CRI iAtlas | 98 | 56 | Melanoma | Nivolumab | Pre-treatment or On-treatment | OS and response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina Genome Analyzer) |

| GSE93157 | NCBI GEO | 5 | 65 | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Nivolumab | Pre-treatment | PFS and response by RECIST | NanoString nCounter PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel |

| 22 | Non-Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | PFS and response by RECIST | ||||

| 25 | Skin Cutaneous Melanoma | Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | PFS and response by RECIST | ||||

| 13 | Squamous Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer | Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | PFS and response by RECIST | ||||

| GSE115821 | NCBI GEO | 37 | 11 | Melanoma | Anti-PD-1 and/ or Anti-CTLA-4 | Pre-treatment or On-treatment | Response | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2000 and Illumina NextSeq 500) |

| GSE121810 | NCBI GEO and CRI iAtlas | 28 | 28 | Glioblastoma | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment or On-treatment | PFI, OS, response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 3000) |

| GSE136961 | NCBI GEO | 21 | 21 | Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer | Anti-PD-1 | Pre-treatment | PFS, OS | RNA-Seq (Ion Torrent S5 XL) |

| GSE140901 | NCBI GEO | 22 | 22 | Hepatocellular Carcinoma | Nivolumab and/ or Ipilimumab | Pre-treatment | PFS, OS, response by RECIST | NanoString nCounter PanCancer Immune Profiling Panel |

| GSE165252 | NCBI GEO and Provided by the author upon request | 66 | 40 | Esophageal Adenocarcinoma | Atezolizumab | Pre-treatment or On-treatment | PFS, OS, and response | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 4000) |

| GSE165278 | NCBI GEO and GITHUB | 21 | 21 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab | Pre-treatment or On-treatment | OS | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2500) |

| GSE165745 | NCBI GEO | 24 | 24 | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab or Nivolumab | Pre-treatment | Response | NanoString nCounter Vantage 3D Human Wnt Pathways Panel |

| GSE176307 | NCBI GEO | 84 | 84 | Bladder/ Ureter/ Pelvis Cancer | Pembrolizumab/ Nivolumab, or Atezolizumab/ Durvalumab | Pre-treatment | PFS and response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Ion Torrent S5 XL) |

| GSE183924 | NCBI GEO | 37 | 37 | Esophageal and Gastroesophageal Junction Adenocarcinoma | Durvalumab | Pre-treatment | RFS | RNA-Seq (Illumina NovaSeq 6000) |

| CRISTESCU 2018 | Cristescu et al., Science (2018) and Litchfield et al., Cell (2021) | 17 | 226 | Bladder Cancer | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response | NanoString nCounter |

| 12 | Tripla Negative Breast Cancer | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response | ||||

| 2 | ER + HER2- Breast Cancer | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response | ||||

| 105 | Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response | ||||

| 86 | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response | ||||

| 4 | Small Cell Lung Cancer | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response | ||||

| GIDE 2019 | CRI iAtlas | 88 | 72 | Melanoma | Pembrolizumab and/ or Nivolumab and/ or Ipilimumab | Pre-treatment | PFI, OS, response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2500) |

| KIM 2018 | ENA and Kim et al., Nat Med (2018) | 45 | 45 | Gastric Cancer | Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | Response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina NextSeq 550) |

| LIU 2019 | Liu et al., Nat Med (2019) | 121 | 121 | Melanoma | Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab | Pre-treatment | PFS, OS, response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2000 v3, HiSeq 2500) |

| MARIATHASAN 2018 | CRI iAtlas | 348 | 348 | Urothelial Cancer | Atezolizumab | Pre-treatment | OS and response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina TruSeq RNA Access) |

| MIAO 2018 | Miao et al., Science (2018) | 33 | 33 | Renal Cell Carcinoma | Nivolumab and/ or Ipilimumab, or Atezolizumab | Pre-treatment | PFS, OS, and response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2000 v3, HiSeq 2500) |

| VANALLEN 2015 | CRI iAtlas and Van Allen et al., Science (2015) | 42 | 42 | Melanoma | Ipilimumab | Pre-treatment | PFS, OS, and response by RECIST | RNA-Seq (Illumina HiSeq 2500) |

Different technological, and clinical approaches were utilized in the involved studies such as RNA-sequencing (RNA-Seq) with Illumina [46] or Ion Torrent platforms [47], and NanoString nCounter [48, 49]. Regarding therapies, many studies used combination therapy e.g., anti-PD-1, or anti-PD-L1, with or without anti-CTLA-4 therapy [42], or anti-PD-1 monotherapy, with or without anti-CTLA-4 treatment [50, 51], while others investigated monotherapies only – such as ipilimumab [52], atezolizumab [53], or durvalumab [54].

Druggable genes with higher expression related to resistance to anti-PD1 administration

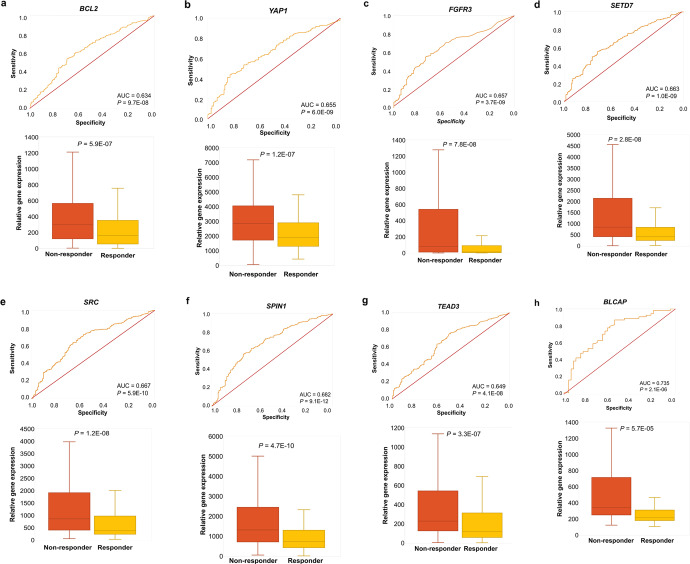

First, the pre-treatment samples in group #1 were investigated by computing ROC AUC and P-values for 29,755 genes. Following Bonferroni correction, values reaching more than P = 1.6E-06 were excluded from further analysis, which led us to 912 significant genes. The most significant hits included MARCKS (FC = 2.2, AUC = 0.724, P = 4.2E-12), SPIN1 (FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.682, P = 9.1E-12), PAK5 (FC = 1.8, AUC = 0.677, P = 6.1E-08), DDAH1 (FC = 1.7, AUC = 0.671, P = 3.4E-10), ELOVL6 (FC = 2.1, AUC = 0.667, P = 3.5E-10), SRC (FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.667, P = 5.9E-10), SETD7 (FC = 1.7, AUC = 0.663, P = 1.0E-09), FGFR3 (FC = 2.1, AUC = 0.657, P = 3.7E-09), YAP1 (FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.655, P = 6.0E-09), BACE1 (FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.654, P = 7.8E-09), STK35 (FC = 1.7, AUC = 0.651, P = 1.4E-08), TEAD3 (FC = 1.7, AUC = 0.649, P = 4.1E-08), TMPRSS4 (FC = 1.5, AUC = 0.640, P = 2.5E-07), PP1CB (FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.639, P = 2.0E-07), and BCL2 (FC = 2.2, AUC = 0.634, P = 9.7E-08) which were all upregulated in the non-responder group (Fig. 2). The complete list of all significant genes is provided in Supplementary Table S1. Notably, non-protein coding genes (such as pseudogenes, long intergenic non-protein coding RNAs, antisense RNAs, regulatory RNAs, small nucleolar RNAs, open reading frame, etc.) were excluded from our screening.

Fig. 2. Top genes of anti-PD-1, or anti-CTLA-4 resistance.

ROC-plots and boxplots of best druggable candidate genes predicting resistance in anti-PD-1 pre-treatment (BCL2 (a), YAP1 (b), FGFR3 (c) SETD7 (d) SRC (e), SPIN1 (f), and TEAD3 (g)), and anti-CTLA-4 pre-treatment groups (BLCAP (h)).

By using all significant genes (n = 912) for GO analysis, mechanisms such as retrograde transport, vesicle recycling within Golgi (GO:0000301), ncRNA catabolic process (GO:0034661), and T cell receptor signaling pathway (GO:0050852) were significantly overrepresented among these genes (Supplementary Table S2).

Druggable genes with higher expression related to resistance to anti-PD-L1 treatment

ROC AUC and P-values from 26,819 genes were computed and following Bonferroni-correction, values over P = 1.8E−06 were excluded. This way, we identified 38 significant genes. The complete list of all significant genes can be found in Supplementary Table S3. The Gene Ontology analysis shows that mechanisms connected to the C-type lectin receptor signaling pathway (GO:0002223), cellular response to lectin (GO:1990858), and positive regulation of natural killer cell-mediated cytotoxicity (GO:0045954) were overrepresented in the list of significant genes (n = 38) (Supplementary Table S2). There were no upregulated, druggable genes capable to predict resistance against anti-PD-L1 therapy.

Druggable genes with higher expression related to anti-CTLA-4 treatment resistance

In this third analysis, ROC AUC and P-values were calculated for 22,561 genes in the pre-treatment group. Of these, 80 genes reached significance after Bonferroni correction. Among them, BLCAP (FC = 1.7, AUC = 0.735, P = 2.1E−06) was found as a druggable gene overexpressed amongst non-responding patients (Fig. 2). The complete gene list can be found in Supplementary Table S4. Non-protein coding genes were also excluded from this group. The GO analysis with multiple testing correction delivered no significant classification for these genes.

Established cancer biomarkers and response to immunotherapy

We also investigated the power of established cancer biomarkers for predicting therapeutic response to immune checkpoint inhibitors. For this, a previously described panel of cancer biomarkers was utilized [55] (see the complete list with results in Supplementary Table S5). The analysis was performed with two cohorts including pre-treatment anti-PD-1, and pre-treatment anti-CTLA-4 samples. Following Bonferroni-correction, only one gene, ALK (Anaplastic Lymphoma Receptor Tyrosine Kinase, FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.612, P = 3.3E−05) showed a correlation with anti-PD-1 response. In case of anti-CTLA-4, CD19 (FC = 1.6, AUC = 0.666, P = 6.5E−04) and PGR (Progesterone Receptor, FC = 1.2, AUC = 0.639, P = 6.8E−03) were found to be predictive. Notably, CD274 (PD-L1), as expected, was overexpressed in responding patients, however, failed to pass the significance threshold after Bonferroni-correction (P = 1.6E−06).

Mismatch-repair genes and response against anti-PD-1 treatment

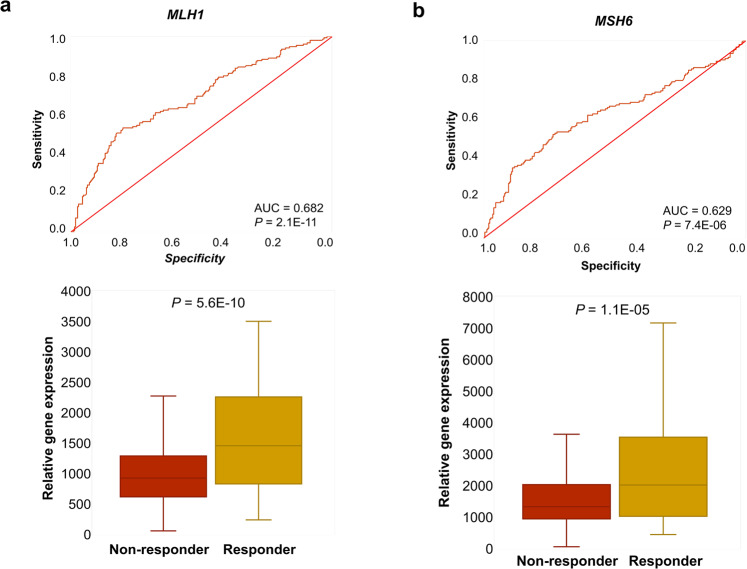

Finally, we aimed to determine to what extent one can predict sensitivity to the anti-PD-1 dostarlimab using the integrated database of published datasets. For this, we performed ROC analysis to evaluate the anti-PD-1 biomarkers previously published in a cohort of rectal cancer [56]. We used transcriptomic data of 419 samples from melanoma, bladder, renal cell, and gastric cancer in the anti-PD-1 pre-treatment cohort (n = 776). In this analysis, MLH1 and MSH6 achieved high predictive values (FC = 1.5, AUC = 0.682, P = 2.1E−11 and FC = 1.4, AUC = 0.629, P = 7.4E−06, respectively). Notably, 218 genes reached even higher ROC AUC than MLH1 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. MLH1, and MSH6 in the anti-PD-1 pre-treatment group.

ROC-plots for predicting sensitivity to anti-PD-1 treatment, and boxplots of gene expression comparing responder and non-responder samples for MLH1 (a) and MSH6 (b) in a combined dataset of anti-PD-1 pre-treatment samples.

Discussion

Here, we integrated available data from multiple datasets and used this combined database to uncover biomarkers related to response against ICIs in three independent clinical settings. An advantage of the presented analysis pipeline is the utilization of real-world patient data. While most of the individual studies have only a limited number of samples, our combined patient cohort with well over a thousand patients provides a higher statistical power.

Among the most significant genes related to resistance against anti-PD-1 treatment, we identified several potentially druggable targets. Fibroblast Growth Factor Receptor 3 (FGFR3) plays a pivotal role in tumorigenesis and the regulation of innate and adaptive immune systems [57]. Overexpression of FGFR3 is associated with an immunologically cold, T cell-depleted phenotype, which contributes to a low ICI response rate in bladder cancer [58]—just like a low PD-L1 expression in an FGFR3-mutant scenario [59]. From multikinase inhibitors (such as anlotinib, dovitinib, lenvatinib, and ponatinib) to selective FGFR inhibitors (e.g., erdafitinib, infigratinib, pemigatinib), various small molecule inhibitors are available for solid tumors and lymphohematopoietic cancers [60, 61]. The combination of FGFR and PD-1 inhibition might also be beneficial [62]. The Src Proto-Oncogene Non-Receptor Tyrosine Kinase (SRC) is a well-known oncogene contributing to cell growth, cell proliferation, and survival. Tumor-induced cytokines, e.g., Macrophage Inflammatory Protein 1, and 2 (MIP-1 and MIP-2) activate Src kinases in immune cells which lead to the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., interleukin-1ß and 6, Tumor Necrosis Factor α) that activate cancer cells in a positive feedback loop [63]. Multikinase inhibitors, such as the FDA-approved bosutinib, dasatinib, ponatinib, and vandetanib are currently being used for the treatment of chronic myeloid leukemia, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, and patients with thyroid cancer [64]. B-Cell Lymphoma 2 (BCL2) is a major regulator of the “apoptotic-orchestra” by inhibiting apoptosis and promoting cell survival [65]. Immune checkpoint molecules themselves promote an anti-apoptotic phenotype—leading to immune tolerance and low response rates [66]. Venetoclax is the only FDA-approved small-molecule inhibitor against BCL2 in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), and chronic lymphatic leukemia—yet other drugs might follow both in hematologic [67] and solid tumor malignancies [68]. Yes-Associated Protein 1 (YAP1) is a transcriptional coactivator, which upon binding to many transcription factors, such as TEAD3 (Transcriptional Enhanced Associate Domain 3), regulates the Hippo-signalling pathway, contributing to tumor growth, and resistance [69]. The Hippo-YAP system interferes with the innate immune system in multiple ways such as inhibiting the production of type I interferons (IFN-α, IFN-ß) and reactive oxygen species (ROS), attenuating NF-κB activation, or enhancing TNF-α and IL-1ß production [70]. These events contribute to the suppression of the innate immune system thus escaping immune recognition – which eventually leads to tumor survival. Verteporfin (VP) is widely used for the treatment of macular degeneration, however, current studies highlighted the antitumor effects of VP either with photoactivation or without it [71]. The capability of CA3, Super-TDU, statins, sitagliptin, SRC, FAK (Focal Adhesion Kinase), and tankyrase inhibitors to disrupt the YAP-TEAD complex were also discussed previously [72]. SET Domain Containing Lysine Methyltransferase 7 (SETD7) has a broad target-specificity as it is involved in many biological processes by interacting with p53, Estrogen Receptor-Alpha (ERα), or YAP1. For this reason, SETD7 can both activate and inhibit tumor-survival signals [73, 74]. Upon methylation on K494 by SETD7, YAP1 accumulates in the cytoplasm and blocks the Hippo-pathway [75]. This leads to the nuclear accumulation of ß-catenin and the activation of the Wnt/ß-catenin pathway which is one of the most well-known oncogenic pathways [76]. Besides having a direct effect on cell proliferation and stemness, ß-catenin promotes a non-inflammatory milieu in tumors by inhibiting the activation and recruitment of CD8+ T cells and enhancing the infiltration and survival of regulatory T cells (Tregs). This leads to resistance to ICIs, emphasizing the potential of Wnt/ß-catenin as a predictive biomarker, or as a therapeutic target [77]. Moreover, SETD7 can methylate p65 and thereby inhibit the expression of NF-κB, and is a positive regulator of Transforming Growth Factor Beta (TGF-ß) production – all these contribute to tumorigenesis [78]. There are some promising results of inhibiting SETD7 with DC-S100 [79], DC-S285 [80], cyproheptadine [81], and ®-PFI-2 [73]. Spindlin 1 (SPIN1) is a histone methylation reader contributing to the epigenetic regulation of many oncogenic pathways so it is not surprising that SPIN1 was found to be overexpressed in many cancers [82]. Notably, SPIN1 acts as a transcriptional coactivator of ß-catenin and T cell Factor 4 (TCF-4) enhancing their contribution to Wnt/TCF-4 pathways, which leads to tumor progression [83]. Inhibitors of SPIN1 are being studied—e.g., A366, EML405, MS31, 4-aminoquinazoline and quinazolinethione derivatives, or VinSpinIn [82].

We have found only one gene related to anti-CTLA-4 resistance: BLCAP or Bladder Cancer Associated Protein. As an apoptosis-inducing factor, BLCAP can initiate apoptosis in many tumors and is considered a tumor suppressor gene. Lost expression or degradation of BLCAP is observed in urothelial, renal, and cervical cancer, osteosarcoma, colorectal carcinoma, and human tongue carcinoma [84, 85]. Nonetheless, poor survival of bladder cancer patients correlates with strong nuclear expression of BLCAP [86], which is impacted by the interaction of BLCAP and Signal Transducer and Activator of Transcription 3 (STAT3) in the JAK/STAT-pathway [85]. Selective pharmacological inhibition of BLCAP can be observed with aristolochic acid in vitro [87].

In locally advanced rectal cancer, the loss of mismatch-repair genes was a highly significant biomarker of response to the anti-PD-1 inhibitor dostarlimab [56]. When re-evaluating the previously published genes, we were able to confirm a significant correlation with survival in our cohort for MLH1 and MSH6. Nevertheless, 218 genes reached even higher significance than MLH1 in these patients, pointing out that other biomarkers might be even more suitable to select patient cohorts for immunotherapy. The samples in our patient cohort stemmed from melanoma, bladder, renal cell, and gastric cancer suggesting that the loss of mismatch-repair genes could also enhance sensitivity to anti-PD-1 therapy in these tumor types.

There are some limitations of our study. Despite the importance of this topic, only a relatively small number of datasets have been found and included in the analysis. Since the currently used drugs are targeting proteins, an addition of protein-level data would have been useful. Unfortunately, we have not found even one dataset with additional protein abundance data. Finally, as ICIs are approved for advanced cancers, most patients have already received multiple treatment regimes, which might have resulted in significant background noise at the transcriptomic level preventing the identification of the most reliable biomarker candidates.

In summary, we have established a database consisting of gene expression and clinical response data by combining 1434 solid tumor tissue samples obtained before or after immune-checkpoint inhibitor treatment. The most significantly upregulated, pharmacologically important (druggable) genes were identified in connection with the resistance against anti-PD-1, and anti-CTLA-4 treatments. Our extended analysis platform can help to identify, validate, and rank future biomarker candidates.

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

This project was supported by the Hungary National Research, Development and Innovation Office (PharmaLab, RRF-2.3.1-21-2022-00015, TKP-2021-NVA-15, and 2020-1.1.6-JÖVŐ-2021-00013). Project no. KDP-14-3/PALY-2021 has been implemented with the support provided by the Ministry of Culture and Innovation of Hungary from the National Research, Development and Innovation Fund, financed under the KDP-2020 funding scheme. The authors acknowledge the support of ELIXIR-Hungary (https://www.bioinformatics.hu/) and thank Viktoria Lakatos for the careful English editing of the manuscript.

Author contributions

BG was responsible for the concept and design of this article, SAK oversaw the data collection and performed the statistical analysis, JTF established the analysis portal. SAK and BG prepared the initial draft of the manuscript and all authors edited and approved its final form.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Semmelweis University.

Data availability

The original data used in the publications are available from GEO or CRI iAtlas using their respective identifiers, or accessible via the indicated publications.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41401-023-01079-6.

References

- 1.Robert C. A decade of immune-checkpoint inhibitors in cancer therapy. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3801. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-17670-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 1996;271:1734–6. doi: 10.1126/science.271.5256.1734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Walunas TL, Lenschow DJ, Bakker CY, Linsley PS, Freeman GJ, Green JM, et al. CTLA-4 can function as a negative regulator of T-cell activation. Immunity. 1994;1:405–13. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(94)90071-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Twomey JD, Zhang B. Cancer immunotherapy update: FDA-approved checkpoint inhibitors and companion diagnostics. AAPS J. 2021;23:39. doi: 10.1208/s12248-021-00574-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vaddepally RK, Kharel P, Pandey R, Garje R, Chandra AB. Review of indications of FDA-approved immune checkpoint inhibitors per NCCN Guidelines with the level of evidence. Cancers. 2020;12:E738. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hodi FS, O’Day SJ, McDermott DF, Weber RW, Sosman JA, Haanen JB, et al. Improved survival with ipilimumab in patients with metastatic melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:711–23. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1003466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McDermott D, Haanen J, Chen TT, Lorigan P, O’Day S. MDX010-20 investigators. Efficacy and safety of ipilimumab in metastatic melanoma patients surviving more than 2 years following treatment in a phase III trial (MDX010-20) Ann Oncol. 2013;24:2694–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdt291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolchok JD, Neyns B, Linette G, Negrier S, Lutzky J, Thomas L, et al. Ipilimumab monotherapy in patients with pretreated advanced melanoma: a randomised, double-blind, multicentre, phase 2, dose-ranging study. Lancet Oncol. 2010;11:155–64. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70334-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hammers HJ, Plimack ER, Infante JR, Rini BI, McDermott DF, Lewis LD, et al. Safety and efficacy of nivolumab in combination with Ipilimumab in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: The CheckMate 016 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3851–8. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2016.72.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Motzer RJ, Tannir NM, McDermott DF, Arén Frontera O, Melichar B, Choueiri TK, et al. Nivolumab plus ipilimumab versus sunitinib in advanced renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:1277–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1712126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Overman MJ, Lonardi S, Wong KYM, Lenz HJ, Gelsomino F, Aglietta M, et al. Durable clinical benefit with nivolumab Plus lpilimumab in DNA mismatch repair-deficient/microsatellite instability-high metastatic colorectal cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:773–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.9901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yau T, Kang YK, Kim TY, El-Khoueiry AB, Santoro A, Sangro B, et al. Efficacy and safety of nivolumab plus ipilimumab in patients with advanced hepatocellular carcinoma previously treated with sorafenib: The CheckMate 040 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:e204564. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baas P, Scherpereel A, Nowak AK, Fujimoto N, Peters S, Tsao AS, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab in unresectable malignant pleural mesothelioma (CheckMate 743): a multicentre, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;397:375–86. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)32714-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Paz-Ares L, Ciuleanu TE, Cobo M, Schenker M, Zurawski B, Menezes J, et al. First-line nivolumab plus ipilimumab combined with two cycles of chemotherapy in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer (CheckMate 9LA): an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:198–211. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30641-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Agarwala SS, Ribas A. Current experience with CTLA4-blocking monoclonal antibodies for the treatment of solid tumors. J Immunother. 2010;33:557–69. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e3181dcd260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Janjigian YY, Shitara K, Moehler M, Garrido M, Salman P, Shen L, et al. First-line nivolumab plus chemotherapy versus chemotherapy alone for advanced gastric, gastro-oesophageal junction, and oesophageal adenocarcinoma (CheckMate 649): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2021;398:27–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)00797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Robert C, Ribas A, Wolchok JD, Hodi FS, Hamid O, Kefford R, et al. Anti-programmed-death-receptor-1 treatment with pembrolizumab in ipilimumab-refractory advanced melanoma: a randomised dose-comparison cohort of a phase 1 trial. Lancet. 2014;384:1109–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60958-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmid P, Cortes J, Dent R, Pusztai L, McArthur H, Kümmel S, et al. Event-free survival with Pembrolizumab in early triple-negative breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:556–67. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2112651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Grob JJ, Gonzalez R, Basset-Seguin N, Vornicova O, Schachter J, Joshi A, et al. Pembrolizumab monotherapy for recurrent or metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm phase II Trial (KEYNOTE-629) J Clin Oncol. 2020;38:2916–25. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.03054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hughes BGM, Munoz-Couselo E, Mortier L, Bratland Å, Gutzmer R, Roshdy O, et al. Pembrolizumab for locally advanced and recurrent/metastatic cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (KEYNOTE-629 study): an open-label, nonrandomized, multicenter, phase II trial. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1276–85. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Malley DM, Bariani GM, Cassier PA, Marabelle A, Hansen AR, De Jesus Acosta A, et al. Pembrolizumab in patients with microsatellite instability-high advanced endometrial cancer: results from the KEYNOTE-158 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40:752–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.21.01874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo M, Lim HY, Cheng AL, Chao Y, Yau T, Ogasawara S, et al. Pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: a subgroup analysis of Asian patients in Phase 3 KEYNOTE-240 Trial. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:275–84. doi: 10.1159/000515553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marabelle A, Fakih M, Lopez J, Shah M, Shapira-Frommer R, Nakagawa K, et al. Association of tumour mutational burden with outcomes in patients with advanced solid tumours treated with pembrolizumab: prospective biomarker analysis of the multicohort, open-label, phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1353–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30445-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oaknin A, Tinker AV, Gilbert L, Samouëlian V, Mathews C, Brown J, et al. Clinical activity and safety of the anti-programmed death 1 monoclonal antibody Dostarlimab for patients with recurrent or advanced mismatch repair-deficient endometrial cancer: A nonrandomized Phase 1 clinical trial. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6:1766–72. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2020.4515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Oaknin A, Gilbert L, Tinker AV, Brown J, Mathews C, Press J, et al. Safety and antitumor activity of dostarlimab in patients with advanced or recurrent DNA mismatch repair deficient/microsatellite instability-high (dMMR/MSI-H) or proficient/stable (MMRp/MSS) endometrial cancer: interim results from GARNET-a phase I, single-arm study. J Immunother Cancer. 2022;10:e003777. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2021-003777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldman JW, Dvorkin M, Chen Y, Reinmuth N, Hotta K, Trukhin D, et al. Durvalumab, with or without tremelimumab, plus platinum-etoposide versus platinum-etoposide alone in first-line treatment of extensive-stage small-cell lung cancer (CASPIAN): updated results from a randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2021;22:51–65. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(20)30539-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, Galle PR, Ducreux M, Kim TY, et al. Atezolizumab plus Bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:1894–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gutzmer R, Stroyakovskiy D, Gogas H, Robert C, Lewis K, Protsenko S, et al. Atezolizumab, vemurafenib, and cobimetinib as first-line treatment for unresectable advanced BRAFV600 mutation-positive melanoma (IMspire150): primary analysis of the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2020;395:1835–44. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30934-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cristescu R, Mogg R, Ayers M, Albright A, Murphy E, Yearley J, et al. Pan-tumor genomic biomarkers for PD-1 checkpoint blockade-based immunotherapy. Science. 2018;362:eaar3593. doi: 10.1126/science.aar3593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim ST, Cristescu R, Bass AJ, Kim KM, Odegaard JI, Kim K, et al. Comprehensive molecular characterization of clinical responses to PD-1 inhibition in metastatic gastric cancer. Nat Med. 2018;24:1449–58. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0101-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mariathasan S, Turley SJ, Nickles D, Castiglioni A, Yuen K, Wang Y, et al. TGF-β attenuates tumour response to PD-L1 blockade by contributing to exclusion of T cells. Nature. 2018;554:544–8. doi: 10.1038/nature25501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Riaz N, Havel JJ, Makarov V, Desrichard A, Urba WJ, Sims JS, et al. Tumor and microenvironment evolution during immunotherapy with nivolumab. Cell. 2017;171:934–949.e16. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.09.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cloughesy TF, Mochizuki AY, Orpilla JR, Hugo W, Lee AH, Davidson TB, et al. Neoadjuvant anti-PD-1 immunotherapy promotes a survival benefit with intratumoral and systemic immune responses in recurrent glioblastoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:477–86. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0337-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van Allen EM, Miao D, Schilling B, Shukla SA, Blank C, Zimmer L, et al. Genomic correlates of response to CTLA-4 blockade in metastatic melanoma. Science. 2015;350:207–11. doi: 10.1126/science.aad0095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hwang S, Kwon AY, Jeong JY, Kim S, Kang H, Park J, et al. Immune gene signatures for predicting durable clinical benefit of anti-PD-1 immunotherapy in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2020;10:643. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-57218-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Prat A, Navarro A, Paré L, Reguart N, Galván P, Pascual T, et al. Immune-related gene expression profiling after PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung carcinoma, head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and melanoma. Cancer Res. 2017;77:3540–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Liu D, Schilling B, Liu D, Sucker A, Livingstone E, Jerby-Arnon L, et al. Integrative molecular and clinical modeling of clinical outcomes to PD1 blockade in patients with metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 2019;25:1916–27. doi: 10.1038/s41591-019-0654-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mi H, Muruganujan A, Ebert D, Huang X, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 14: more genomes, a new PANTHER GO-slim and improvements in enrichment analysis tools. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:D419–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/gky1038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Menyhart O, Weltz B, Győrffy B. MultipleTesting.com: A tool for life science researchers for multiple hypothesis testing correction. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0245824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0245824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eddy JA, Thorsson V, Lamb AE, Gibbs DL, Heimann C, Yu JX, et al. CRI iAtlas: an interactive portal for immuno-oncology research. F1000Res. 2020;9:1028. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.25141.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Litchfield K, Reading JL, Puttick C, Thakkar K, Abbosh C, Bentham R, et al. Meta-analysis of tumor- and T cell-intrinsic mechanisms of sensitization to checkpoint inhibition. Cell. 2021;184:596–614.e14. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2021.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Miao D, Margolis CA, Gao W, Voss MH, Li W, Martini DJ, et al. Genomic correlates of response to immune checkpoint therapies in clear cell renal cell carcinoma. Science. 2018;359:801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen PL, Roh W, Reuben A, Cooper ZA, Spencer CN, Prieto PA, et al. Analysis of immune signatures in longitudinal tumor samples yields insight into biomarkers of response and mechanisms of resistance to immune checkpoint blockade. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:827–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barrett T, Wilhite SE, Ledoux P, Evangelista C, Kim IF, Tomashevsky M, et al. NCBI GEO: archive for functional genomics data sets–update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:D991–995. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Edgar R, Domrachev M, Lash AE. Gene Expression Omnibus: NCBI gene expression and hybridization array data repository. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:207–10. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hugo W, Zaretsky JM, Sun L, Song C, Moreno BH, Hu-Lieskovan S, et al. Genomic and transcriptomic features of response to anti-PD-1 therapy in metastatic melanoma. Cell. 2016;165:35–44. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.02.065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rose TL, Weir WH, Mayhew GM, Shibata Y, Eulitt P, Uronis JM, et al. Fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 alterations and response to immune checkpoint inhibition in metastatic urothelial cancer: a real world experience. Br J Cancer. 2021;125:1251–60. doi: 10.1038/s41416-021-01488-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeVito NC, Sturdivant M, Thievanthiran B, Xiao C, Plebanek MP, Salama AKS, et al. Pharmacological Wnt ligand inhibition overcomes key tumor-mediated resistance pathways to anti-PD-1 immunotherapy. Cell Rep. 2021;35:109071. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hsu CL, Ou DL, Bai LY, Chen CW, Lin L, Huang SF, et al. Exploring markers of exhausted CD8 T cells to predict response to immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Liver Cancer. 2021;10:346–59. doi: 10.1159/000515305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Auslander N, Zhang G, Lee JS, Frederick DT, Miao B, Moll T, et al. Robust prediction of response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy in metastatic melanoma. Nat Med. 2018;24:1545–9. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0157-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gide TN, Quek C, Menzies AM, Tasker AT, Shang P, Holst J, et al. Distinct immune cell populations define response to anti-PD-1 monotherapy and anti-PD-1/Anti-CTLA-4 combined therapy. Cancer Cell. 2019;35:238–55. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zappasodi R, Serganova I, Cohen IJ, Maeda M, Shindo M, Senbabaoglu Y, et al. CTLA-4 blockade drives loss of Treg stability in glycolysis-low tumours. Nature. 2021;591:652–8. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03326-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.van den Ende T, de Clercq NC, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Gisbertz SS, Geijsen ED, Verhoeven RHA, et al. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy combined with atezolizumab for resectable esophageal adenocarcinoma: A Single-arm Phase II Feasibility Trial (PERFECT) Clin Cancer Res. 2021;27:3351–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-4443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mamdani H, Schneider B, Perkins SM, Burney HN, Kasi PM, Abushahin LI, et al. A Phase II trial of adjuvant durvalumab following trimodality therapy for locally advanced esophageal and gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: A Big Ten Cancer Research Consortium Study. Front Oncol. 2021;11:736620. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.736620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sarhadi VK, Armengol G. Molecular biomarkers in cancer. Biomolecules. 2022;12:1021. doi: 10.3390/biom12081021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cercek A, Lumish M, Sinopoli J, Weiss J, Shia J, Lamendola-Essel M, et al. PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair–deficient, locally advanced rectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:2363–76. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2201445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kacew A, Sweis RF. FGFR3 alterations in the era of immunotherapy for urothelial bladder cancer. Front Immunol. 2020;11:575258. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.575258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sweis RF, Spranger S, Bao R, Paner GP, Stadler WM, Steinberg G, et al. Molecular drivers of the non-T-cell-inflamed tumor microenvironment in urothelial bladder cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2016;4:563–8. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-15-0274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chen S, Zhang N, Shao J, Wang T, Wang X. Multi-omics perspective on the tumor microenvironment based on PD-L1 and CD8 T-cell infiltration in urothelial cancer. J Cancer. 2019;10:697–707. doi: 10.7150/jca.28494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kommalapati A, Tella SH, Borad M, Javle M, Mahipal A. FGFR inhibitors in oncology: insight on the management of toxicities in clinical practice. Cancers. 2021;13:2968. doi: 10.3390/cancers13122968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zengin ZB, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Salgia NJ, Muddasani R, Ali S, Meza L, et al. Targeted therapies: Expanding the role of FGFR3 inhibition in urothelial carcinoma. Urol Oncol: Semin Original Investig. 2022;40:25–36. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2021.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Palakurthi S, Kuraguchi M, Zacharek SJ, Zudaire E, Huang W, Bonal DM, et al. The combined effect of FGFR inhibition and PD-1 blockade promotes tumor-intrinsic induction of antitumor immunity. Cancer Immunol Res. 2019;7:1457–71. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-18-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Liu ST, Pham H, Pandol SJ, Ptasznik A. Src as the link between inflammation and cancer. Front Physiol. 2014;4:416. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roskoski R. Src protein-tyrosine kinase structure, mechanism, and small molecule inhibitors. Pharmacol Res. 2015;94:9–25. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Basu A. The interplay between apoptosis and cellular senescence: Bcl-2 family proteins as targets for cancer therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 2022;230:107943. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2021.107943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y, Zheng J. Functions of immune checkpoint molecules beyond immune evasion. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1248:201–26. doi: 10.1007/978-981-15-3266-5_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roberts AW, Wei AH, Huang DCS. BCL2 and MCL1 inhibitors for hematologic malignancies. Blood. 2021;138:1120–36. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020006785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vogler M. Targeting BCL2-proteins for the treatment of solid tumours. Adv Med. 2014;2014:943648. doi: 10.1155/2014/943648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Szulzewsky F, Holland EC, Vasioukhin V. YAP1 and its fusion proteins in cancer initiation, progression and therapeutic resistance. Dev Biol. 2021;475:205–21. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2020.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wang S, Zhou L, Ling L, Meng X, Chu F, Zhang S, et al. The crosstalk between Hippo-YAP pathway and innate immunity. Front Immunol. 2020;11:323. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wei C, Li X. The role of photoactivated and non-photoactivated verteporfin on tumor. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:557429. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.557429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yong J, Li Y, Lin S, Wang Z, Xu Y. Inhibitors targeting YAP in gastric cancer: current status and future perspectives. Drug Des Dev Ther. 2021;15:2445–56. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S308377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Barsyte-Lovejoy D, Li F, Oudhoff MJ, Tatlock JH, Dong A, Zeng H, et al. (R)-PFI-2 is a potent and selective inhibitor of SETD7 methyltransferase activity in cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111:12853–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1407358111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Monteiro FL, Williams C, Helguero LA. A systematic review to define the multi-faceted role of lysine methyltransferase SETD7 in cancer. Cancers. 2022;14:1414. doi: 10.3390/cancers14061414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Oudhoff MJ, Freeman SA, Couzens AL, Antignano F, Kuznetsova E, Min PH, et al. Control of the hippo pathway by Set7-dependent methylation of Yap. Dev Cell. 2013;26:188–94. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Oudhoff MJ, Braam MJS, Freeman SA, Wong D, Rattray DG, Wang J, et al. SETD7 controls intestinal regeneration and tumorigenesis by regulating Wnt/β-Catenin and Hippo/YAP signaling. Dev Cell. 2016;37:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2016.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pai SG, Carneiro BA, Mota JM, Costa R, Leite CA, Barroso-Sousa R, et al. Wnt/beta-catenin pathway: modulating anticancer immune response. J Hematol Oncol. 2017;10:101. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0471-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Chiang C, Yang H, Zhu L, Chen C, Chen C, Zuo Y, et al. The epigenetic regulation of nonhistone proteins by SETD7: New targets in cancer. Front Genet. 2022;13:918509. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.918509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Meng F, Cheng S, Ding H, Liu S, Liu Y, Zhu K, et al. Discovery and optimization of novel, selective histone methyltransferase SET7 inhibitors by pharmacophore- and docking-based virtual screening. J Med Chem. 2015;58:8166–81. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ding H, Lu WC, Hu JC, Liu YC, Zhang CH, Lian FL, et al. Identification and characterizations of novel, selective histone methyltransferase SET7 inhibitors by Scaffold Hopping- and 2D-molecular fingerprint-based similarity search. Molecules. 2018;23:E567. doi: 10.3390/molecules23030567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Takemoto Y, Ito A, Niwa H, Okamura M, Fujiwara T, Hirano T, et al. Identification of cyproheptadine as an inhibitor of SET domain containing lysine methyltransferase 7/9 (Set7/9) that regulates estrogen-dependent transcription. J Med Chem. 2016;59:3650–60. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Li D, Guo J, Jia R. Histone code reader SPIN1 is a promising target of cancer therapy. Biochimie. 2021;191:78–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2021.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Wang JX, Zeng Q, Chen L, Du JC, Yan XL, Yuan HF, et al. SPINDLIN1 promotes cancer cell proliferation through activation of WNT/TCF-4 signaling. Mol Cancer Res. 2012;10:326–35. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-11-0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Han F, Hu M, Zhang L, Fan X, Wang J, Lou Z, et al. A-to-I RNA editing of BLCAP promotes cell proliferation by losing the inhibitory of Rb1 in colorectal cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2022;417:113209. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2022.113209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Gromova I, Svensson S, Gromov P, Moreira JMA. Identification of BLCAP as a novel STAT3 interaction partner in bladder cancer. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0188827. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0188827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Moreira JMA, Ohlsson G, Gromov P, Simon R, Sauter G, Celis JE, et al. Bladder cancer-associated protein, a potential prognostic biomarker in human bladder cancer. Mol Cell Proteom. 2010;9:161–77. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900294-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Huang YT, Wu TS, Lu CC, Yu FY, Liu BH. Aristolochic acid I interferes with the expression of BLCAP tumor suppressor gene in human cells. Toxicol Lett. 2018;291:129–37. doi: 10.1016/j.toxlet.2018.03.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The original data used in the publications are available from GEO or CRI iAtlas using their respective identifiers, or accessible via the indicated publications.